Abstract

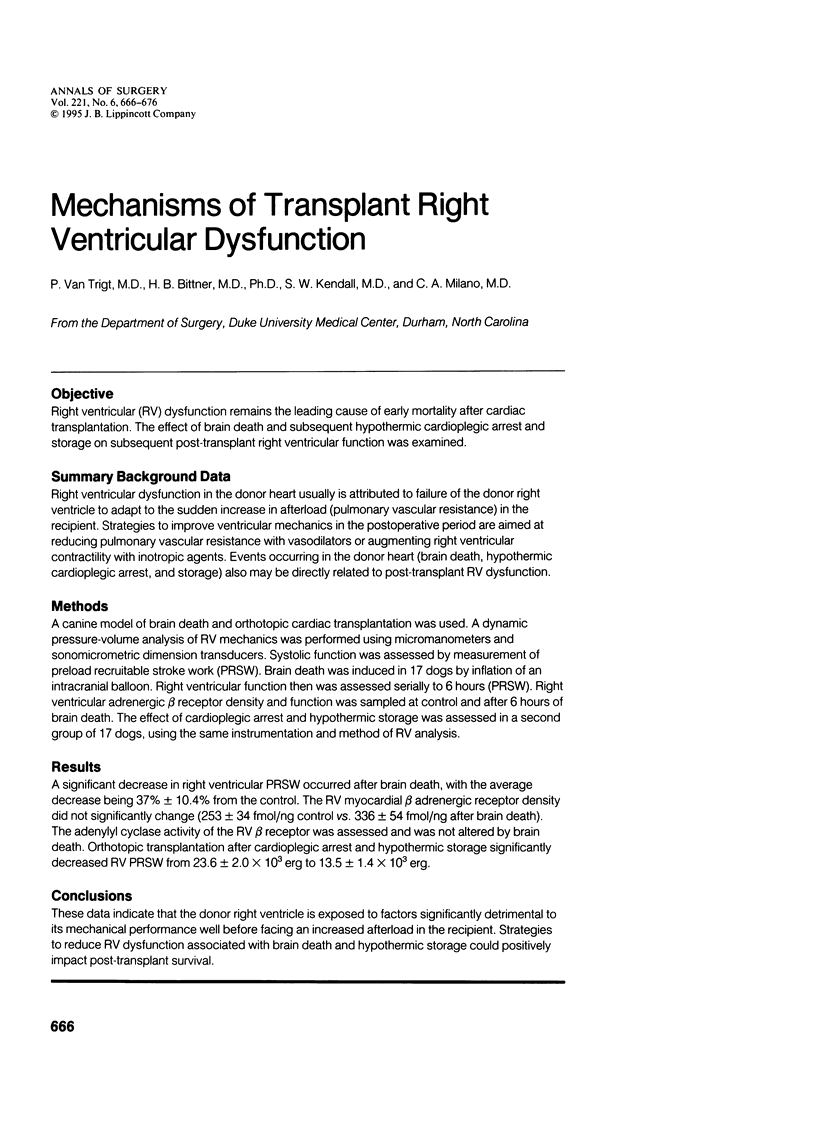

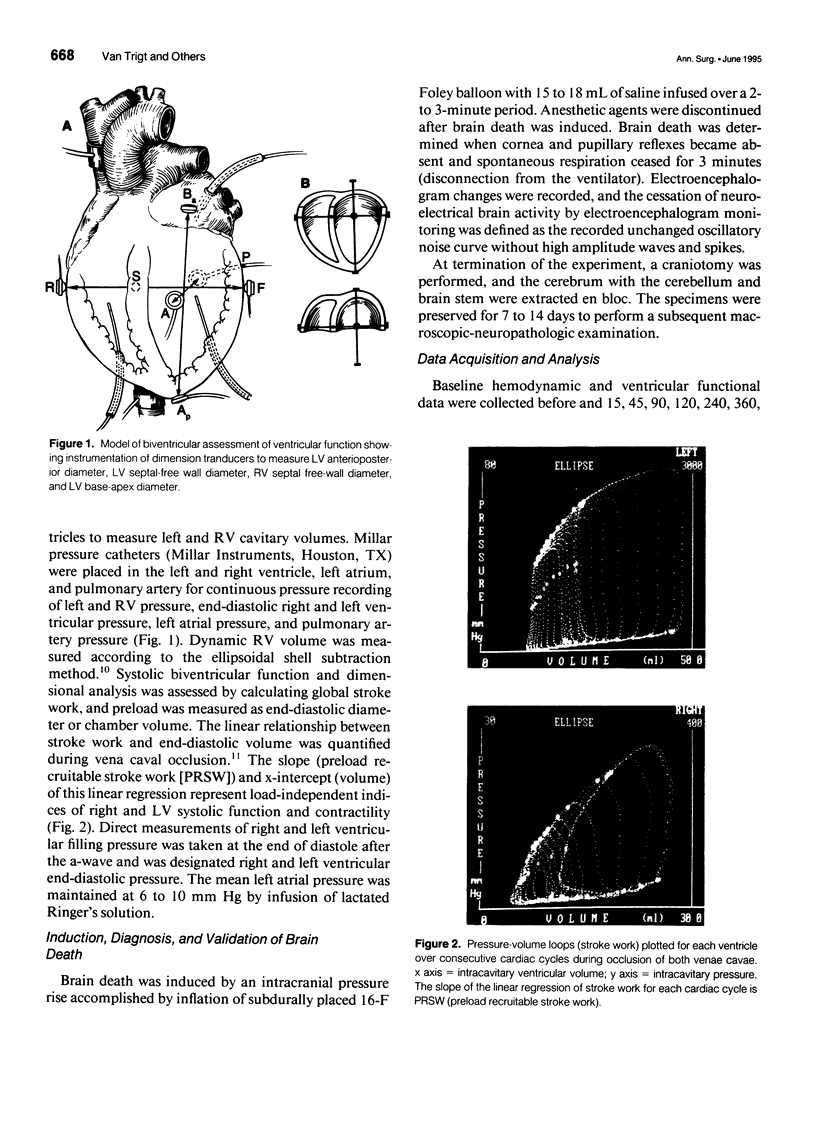

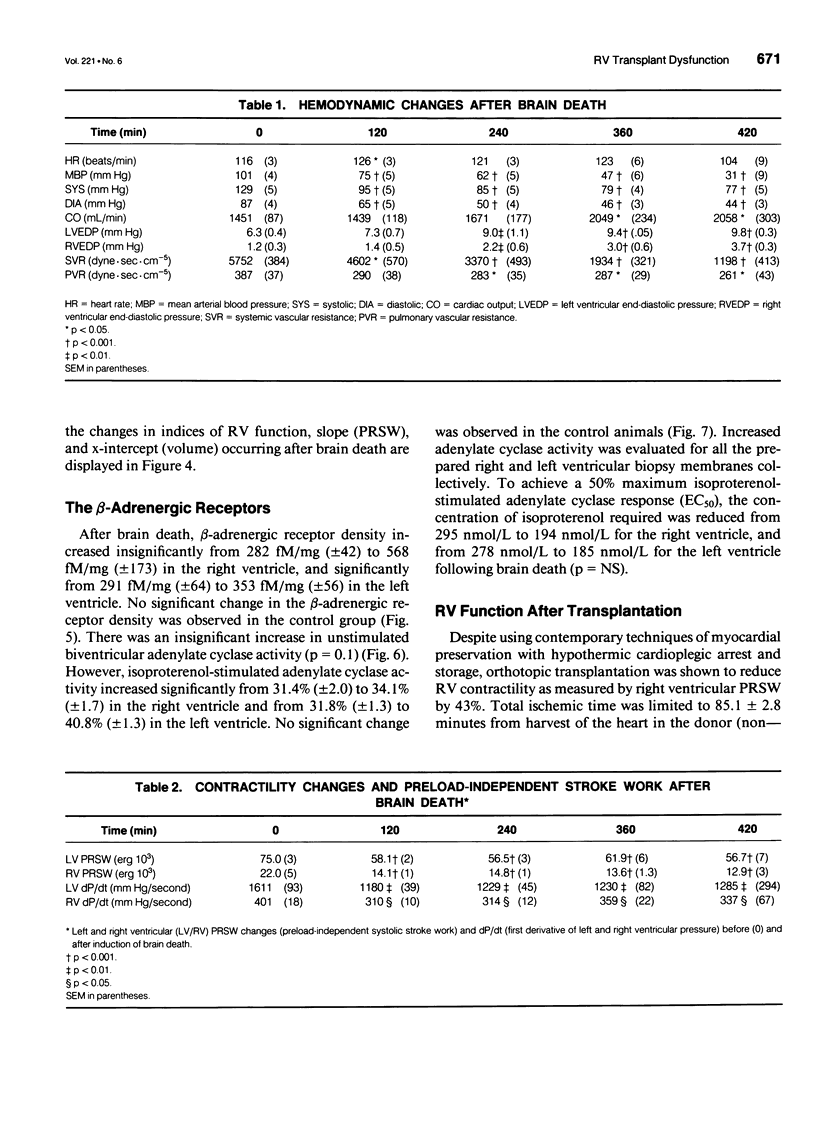

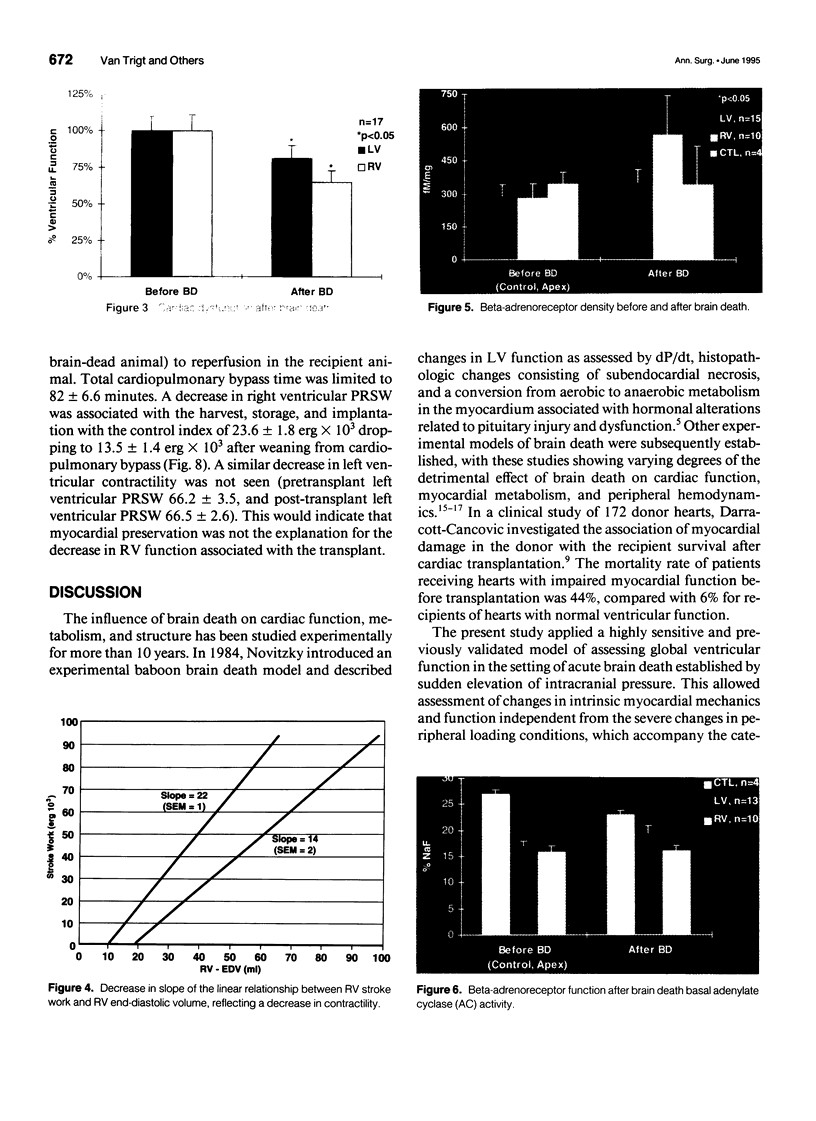

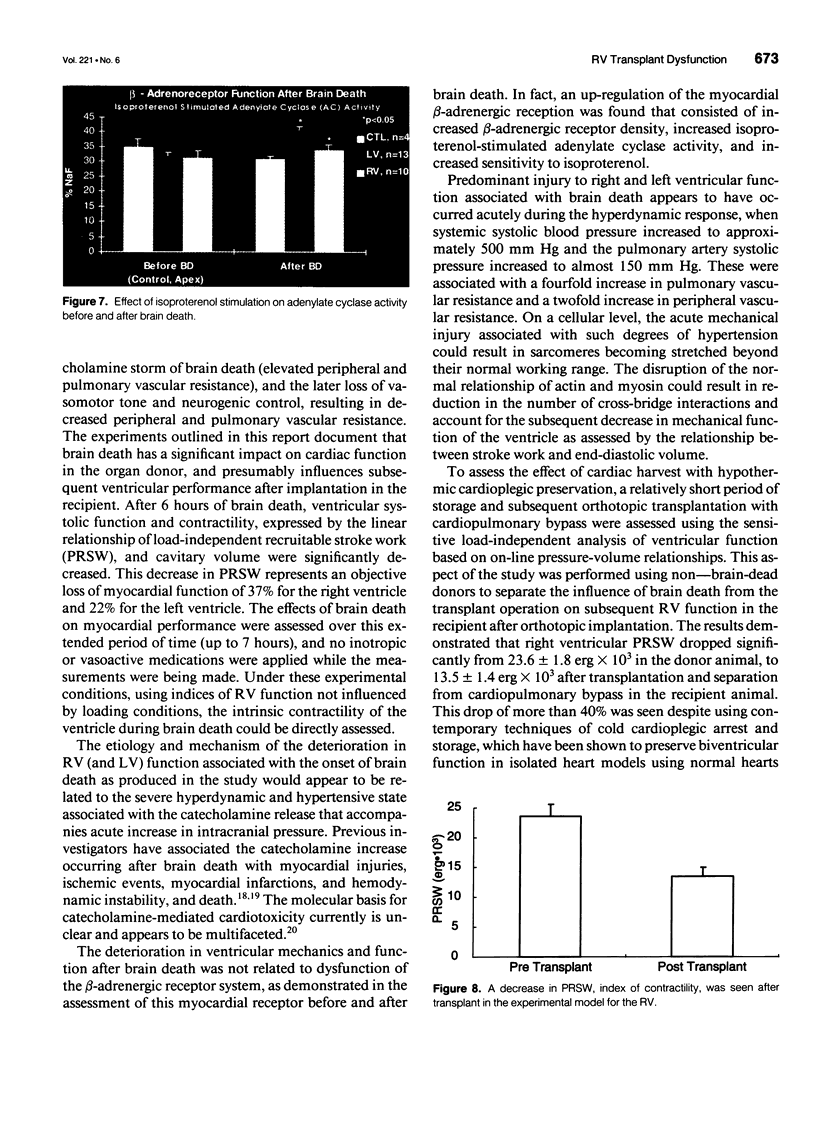

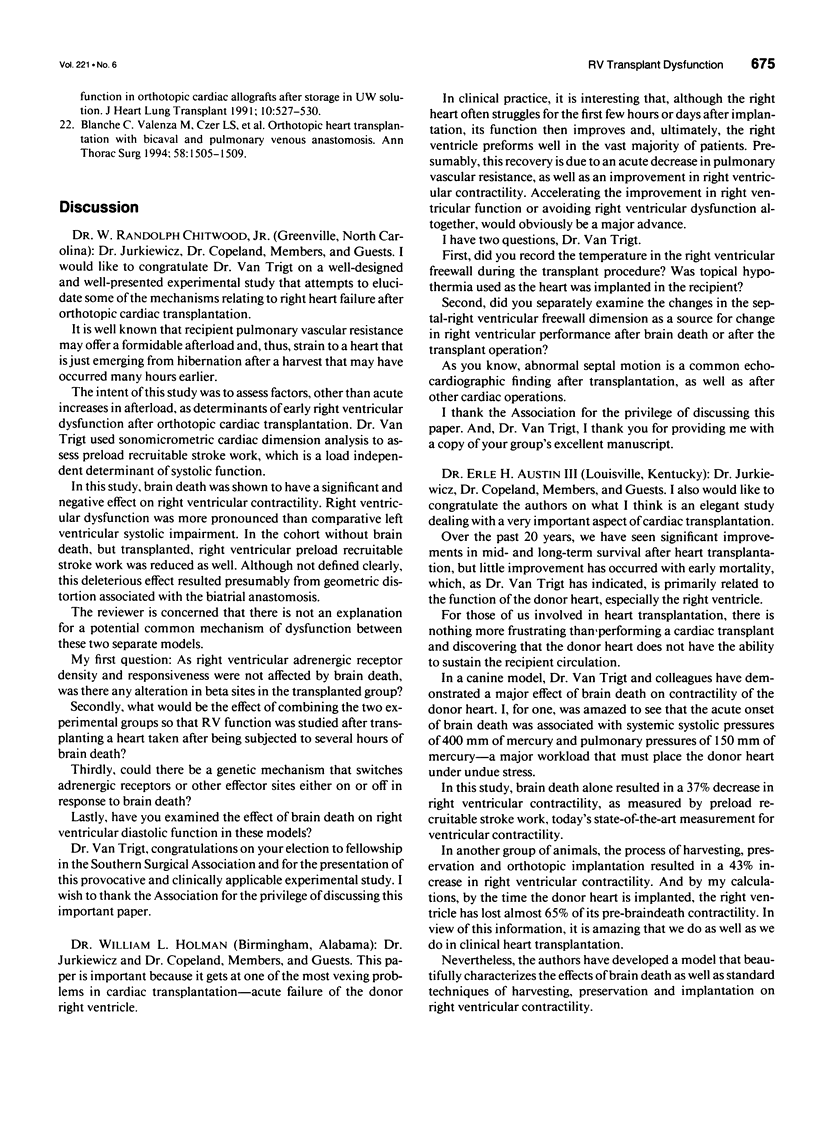

OBJECTIVE: Right ventricular (RV) dysfunction remains the leading cause of early mortality after cardiac transplantation. The effect of brain death and subsequent hypothermic cardioplegic arrest and storage on subsequent post-transplant right ventricular function was examined. SUMMARY BACKGROUND DATA: Right ventricular dysfunction in the donor heart usually is attributed to failure of the donor right ventricle to adapt to the sudden increase in afterload (pulmonary vascular resistance) in the recipient. Strategies to improve ventricular mechanics in the postoperative period are aimed at reducing pulmonary vascular resistance with vasodilators or augmenting right ventricular contractility with inotropic agents. Events occurring in the donor heart (brain death, hypothermic cardioplegic arrest, and storage) also may be directly related to post-transplant RV dysfunction. METHODS: A canine model of brain death and orthotopic cardiac transplantation was used. A dynamic pressure-volume analysis of RV mechanics was performed using micromanometers and sonomicrometric dimension transducers. Systolic function was assessed by measurement of preload recruitable stroke work (PRSW). Brain death was induced in 17 dogs by inflation of an intracranial balloon. Right ventricular function then was assessed serially to 6 hours (PRSW). Right ventricular adrenergic beta receptor density and function was sampled at control and after 6 hours of brain death. The effect of cardioplegic arrest and hypothermic storage was assessed in a second group of 17 dogs, using the same instrumentation and method of RV analysis. RESULTS: A significant decrease in right ventricular PRSW occurred after brain death, with the average decrease being 37% +/- 10.4% from the control. The RV myocardial beta adrenergic receptor density did not significantly change (253 +/- 34 fmol/ng control vs. 336 +/- 54 fmol/ng after brain death). The adenylyl cyclase activity of the RV beta receptor was assessed and was not altered by brain death. Orthotopic transplantation after cardioplegic arrest and hypothermic storage significantly decreased RV PRSW from 23.6 +/- 2.0 x 10(3) erg to 13.5 +/- 1.4 x 10(3) erg. CONCLUSIONS: These data indicate that the donor right ventricle is exposed to factors significantly detrimental to its mechanical performance well before facing an increased afterload in the recipient. Strategies to reduce RV dysfunction associated with brain death and hypothermic storage could positively impact post-transplant survival.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Blaine E. M., Tallman R. D., Jr, Frolicher D., Jordan M. A., Bluth L. L., Howie M. B. Vasopressin supplementation in a porcine model of brain-dead potential organ donors. Transplantation. 1984 Nov;38(5):459–464. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198411000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanche C., Valenza M., Czer L. S., Barath P., Admon D., Harasty D., Utley C., Freimark D., Aleksic I., Matloff J. Orthotopic heart transplantation with bicaval and pulmonary venous anastomoses. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994 Nov;58(5):1505–1509. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)91944-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow M. R., Kantrowitz N. E., Ginsburg R., Fowler M. B. Beta-adrenergic function in heart muscle disease and heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1985 Jul;17 (Suppl 2):41–52. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(85)90007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darracott-Cankovic S., Stovin P. G., Wheeldon D., Wallwork J., Wells F., English T. A. Effect of donor heart damage on survival after transplantation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1989;3(6):525–532. doi: 10.1016/1010-7940(89)90113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbeery J. R., Lucke J. C., Speier R., Rankin J. S., VanTrigt P. Analysis of myocardial function in orthotopic cardiac allografts after prolonged storage in UW solution. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1991 Jul-Aug;10(4):527–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feneley M. P., Elbeery J. R., Gaynor J. W., Gall S. A., Jr, Davis J. W., Rankin J. S. Ellipsoidal shell subtraction model of right ventricular volume. Comparison with regional free wall dimensions as indexes of right ventricular function. Circ Res. 1990 Dec;67(6):1427–1436. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.6.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrans V. J., Hibbs R. G., Weily H. S., Weilbaecher D. G., Walsh J. J., Burch G. E. A histochemical and electron microscopic study of epinephrine-induced myocardial necrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1970 Mar;1(1):11–22. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(70)90025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galiñanes M., Hearse D. J. Brain death-induced impairment of cardiac contractile performance can be reversed by explantation and may not preclude the use of hearts for transplantation. Circ Res. 1992 Nov;71(5):1213–1219. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.5.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glower D. D., Spratt J. A., Snow N. D., Kabas J. S., Davis J. W., Olsen C. O., Tyson G. S., Sabiston D. C., Jr, Rankin J. S. Linearity of the Frank-Starling relationship in the intact heart: the concept of preload recruitable stroke work. Circulation. 1985 May;71(5):994–1009. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.71.5.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhoot J. H., Reichenbach D. D. Cardiac injury and subarachnoid hemorrhage. A clinical, pathological, and physiological correlation. J Neurosurg. 1969 May;30(5):521–531. doi: 10.3171/jns.1969.30.5.0521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye M. P. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: tenth official report--1993. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1993 Jul-Aug;12(4):541–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirklin J. K., Naftel D. C., McGiffin D. C., McVay R. F., Blackstone E. H., Karp R. B. Analysis of morbid events and risk factors for death after cardiac transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988 May;11(5):917–924. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)90045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers C. H., D'Amico T. A., Peterseim D. S., Jayawant A. M., Steenbergen C., Sabiston D. C., Jr, Van Trigt P. Effects of triiodothyronine and vasopressin on cardiac function and myocardial blood flow after brain death. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1993 Jan-Feb;12(1 Pt 1):68–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milano C. A., Allen L. F., Rockman H. A., Dolber P. C., McMinn T. R., Chien K. R., Johnson T. D., Bond R. A., Lefkowitz R. J. Enhanced myocardial function in transgenic mice overexpressing the beta 2-adrenergic receptor. Science. 1994 Apr 22;264(5158):582–586. doi: 10.1126/science.8160017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novitzky D., Cooper D. K., Reichart B. Hemodynamic and metabolic responses to hormonal therapy in brain-dead potential organ donors. Transplantation. 1987 Jun;43(6):852–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon Y., Londos C., Rodbell M. A highly sensitive adenylate cyclase assay. Anal Biochem. 1974 Apr;58(2):541–548. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(74)90222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd G. L., Baroldi G., Pieper G. M., Clayton F. C., Eliot R. S. Experimental catecholamine-induced myocardial necrosis. I. Morphology, quantification and regional distribution of acute contraction band lesions. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1985 Apr;17(4):317–338. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(85)80132-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]