Abstract

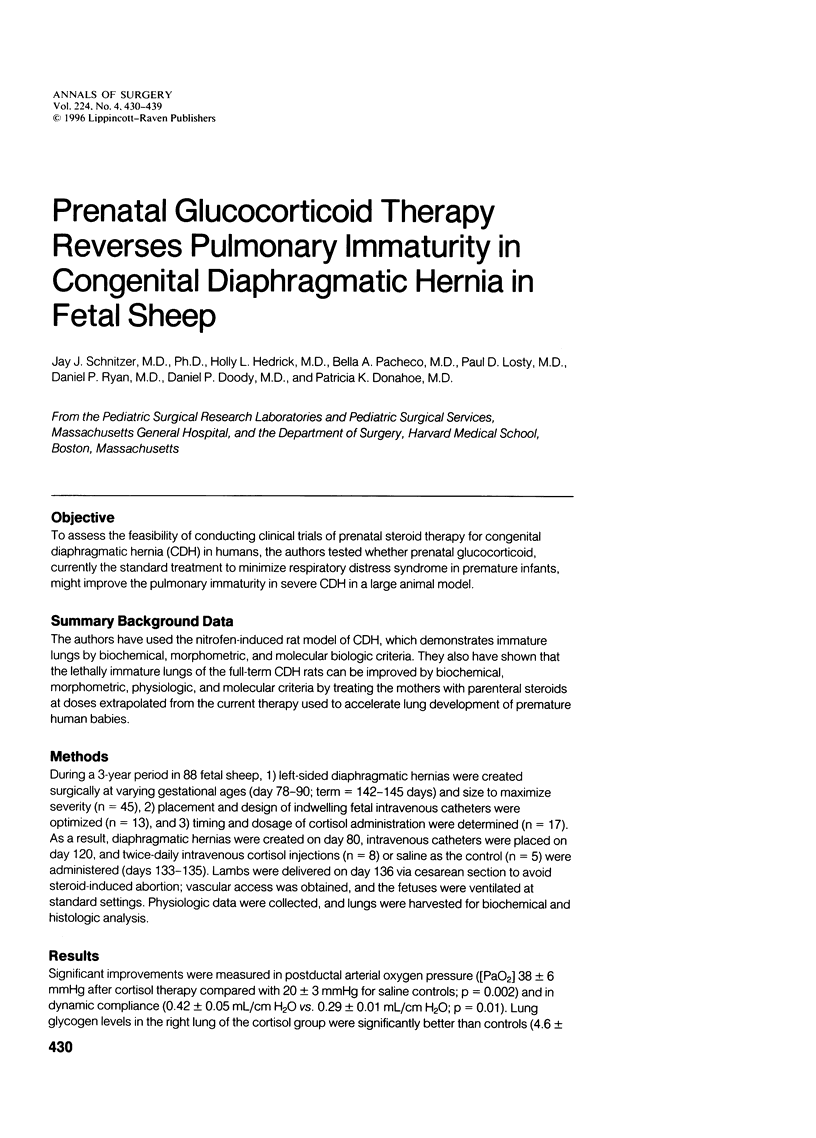

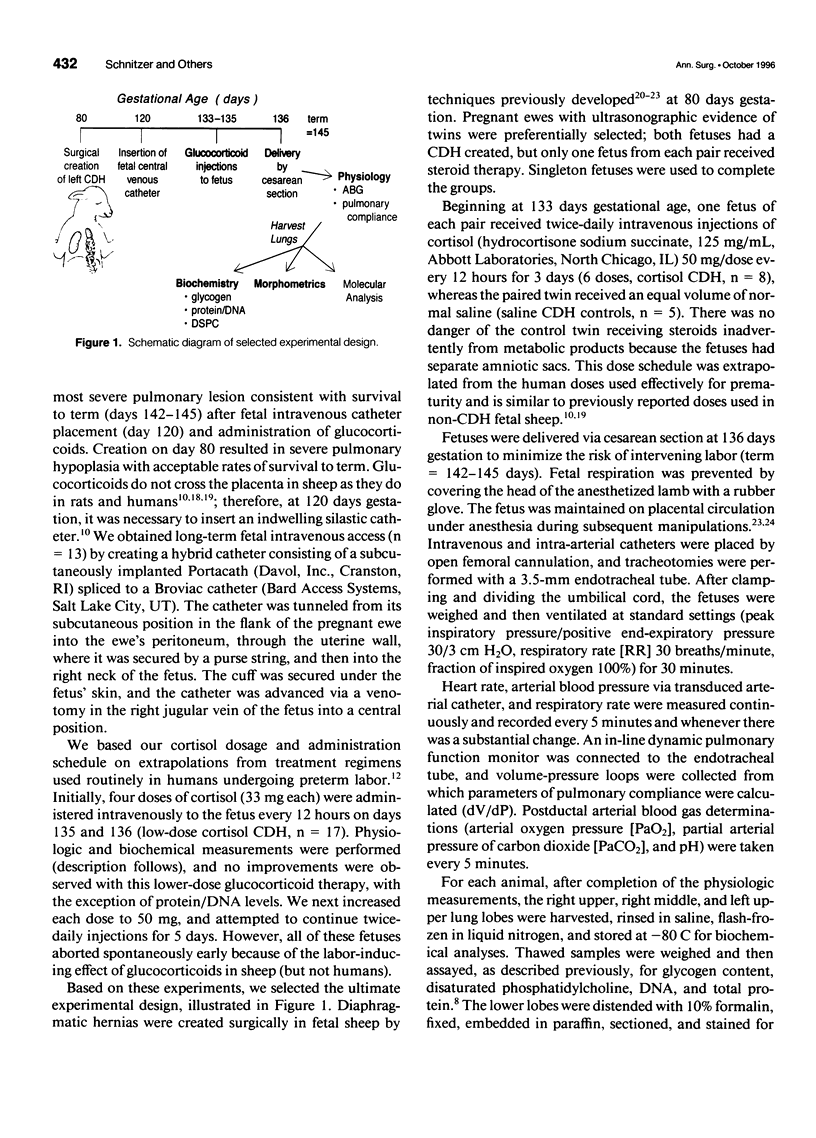

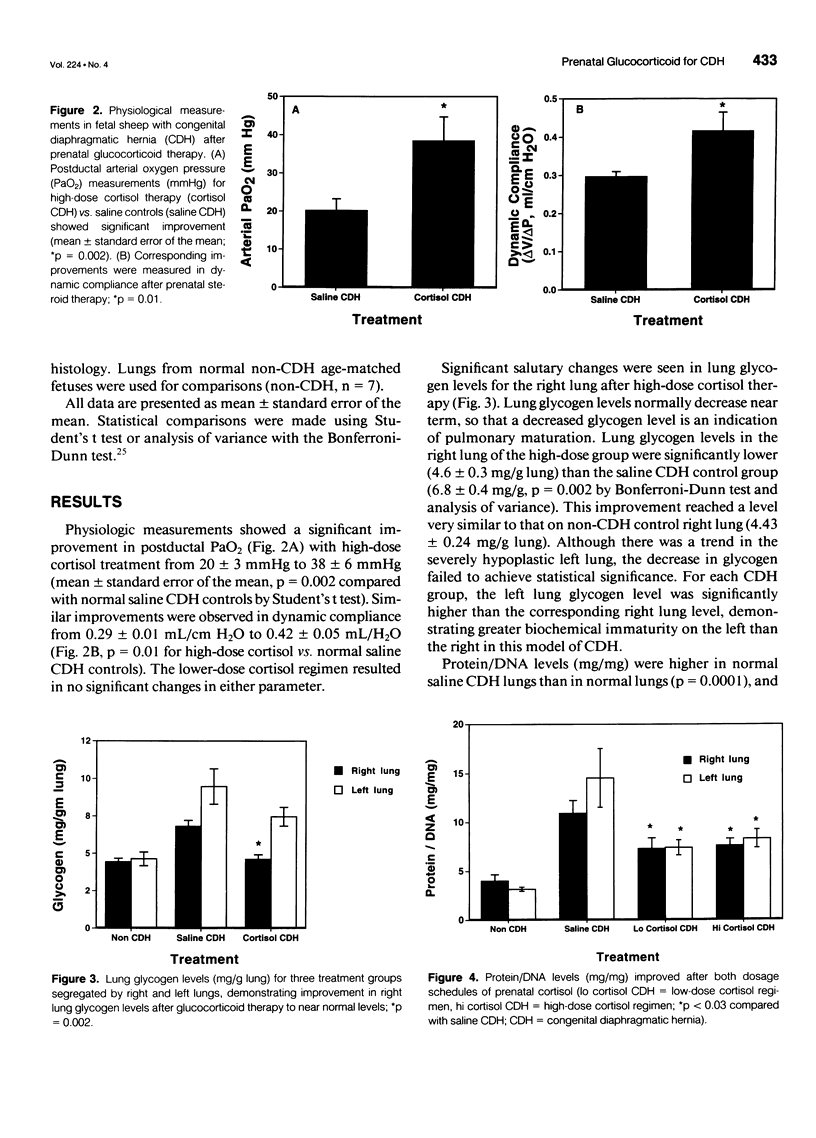

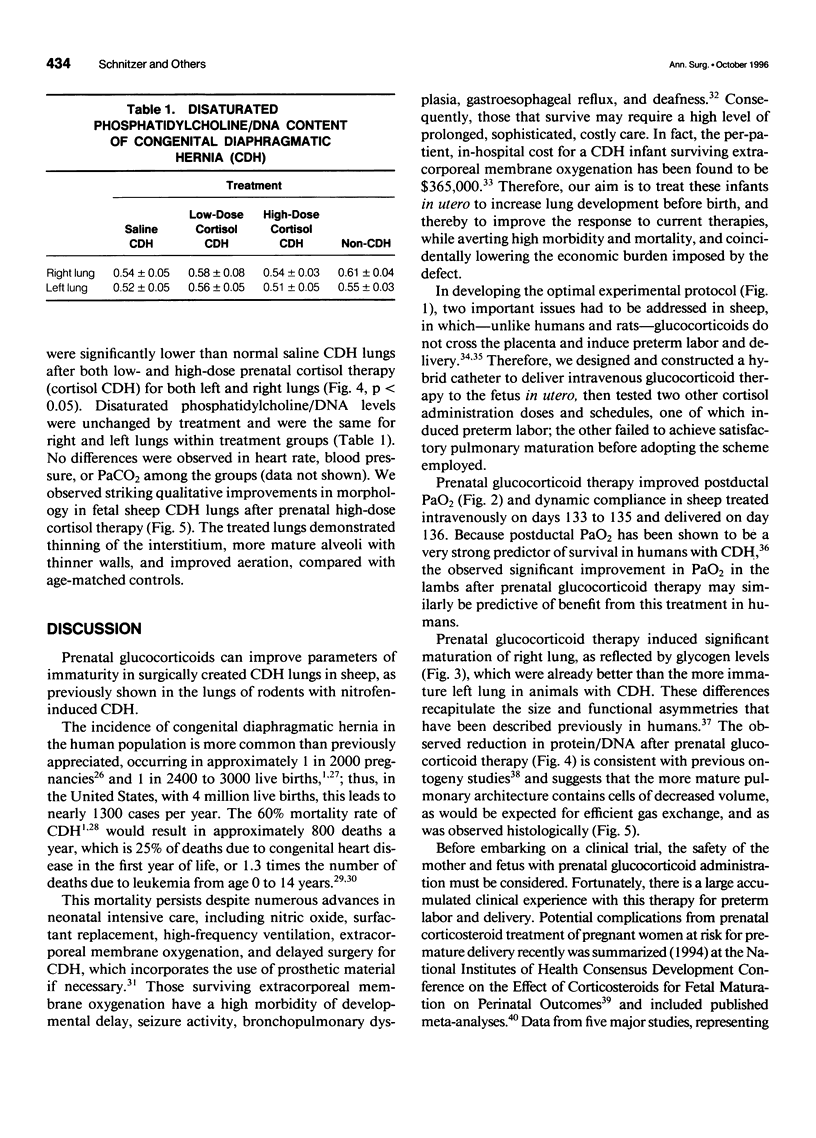

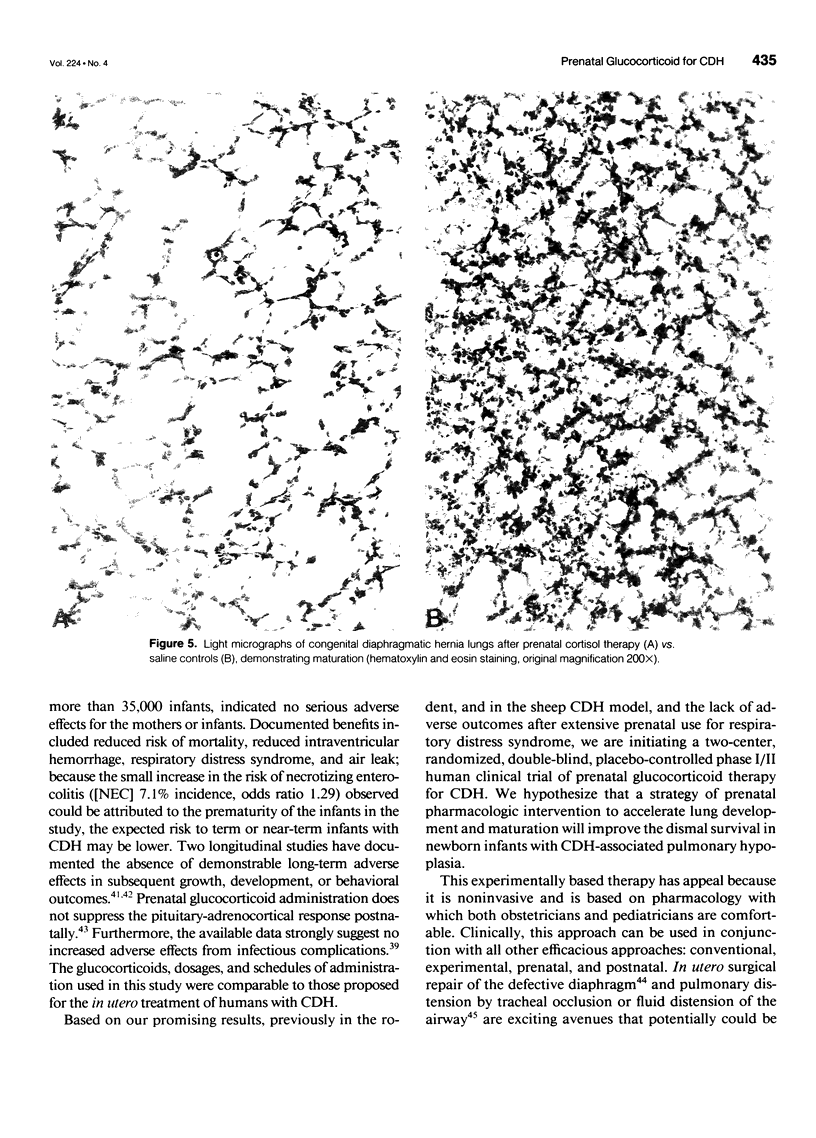

OBJECTIVE: To assess the feasibility of conducting clinical trials of prenatal steroid therapy for congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) in humans, the authors tested whether prenatal glucocorticoid, currently the standard treatment to minimize respiratory distress syndrome in premature infants, might improve the pulmonary immaturity in severe CDH in a large animal model. SUMMARY BACKGROUND DATA: The authors have used the nitrofen-induced rat model of CDH, which demonstrates immature lungs by biochemical, morphometric, and molecular biologic criteria. They also have shown that the lethally immature lungs of the full-term CDH rats can be improved by biochemical, morphometric, physiologic, and molecular criteria by treating the mothers with parenteral steroids at doses extrapolated from the current therapy used to accelerate lung development of premature human babies. METHODS: During a 3-year period in 88 fetal sheep, 1) left-sided diaphragmatic hernias were created surgically at varying gestational ages (day 78-90; term = 142-145 days) and size to maximize severity (n = 45), 2) placement and design of indwelling fetal intravenous catheters were optimized (n = 13), and 3) timing and dosage of cortisol administration were determined (n = 17). As a result, diaphragmatic hernias were created on day 80, intravenous catheters were placed on day 120, and twice-daily intravenous cortisol injections (n = 8) or saline as the control (n = 5) were administered (days 133-135). Lambs were delivered on day 136 via cesarean section to avoid steroid-induced abortion; vascular access was obtained, and the fetuses were ventilated at standard settings. Physiologic data were collected, and lungs were harvested for biochemical and histologic analysis. RESULTS: Significant improvements were measured in postductal arterial oxygen pressure ([PaO2] 38 +/- 6 mmHg after cortisol therapy compared with 20 +/- 3 mmHg for saline controls; p = 0.002) and in dynamic compliance (0.42 +/- 0.05 mL/cm H2O vs. 0.29 +/- 0.01 mL/cm H2O; p = 0.01). Lung glycogen levels in the right lung of the cortisol group were significantly better than controls (4.6 +/- 0.3 mg/g lung vs. 6.8 +/- 0.4 mg/g; p = 0.002), as were protein/DNA levels (8.3 +/- 0.9 mg/mg vs. 14.5 +/- mg/mg; p < 0.05). Striking morphologic maturation of airway architecture was observed in the treated lungs. CONCLUSIONS: Prenatal glucocorticoids correct the pulmonary immaturity of fetal sheep with CDH by physiologic, biochemical, and histologic criteria. These data, combined with previous small animal studies, have prompted the authors to initiate a prospective phase I/II clinical trial to examine the efficacy of prenatal glucocorticoids to improve the maturation of hypoplastic lungs associated with CDH.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Avery M. E. Historical overview of antenatal steroid use. Pediatrics. 1995 Jan;95(1):133–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUTLER N., CLAIREAUX A. E. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia as a cause of perinatal mortality. Lancet. 1962 Mar 31;1(7231):659–663. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(62)92878-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard P. L., Gluckman P. D., Liggins G. C., Kaplan S. L., Grumbach M. M. Steroid and growth hormone levels in premature infants after prenatal betamethasone therapy to prevent respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatr Res. 1980 Feb;14(2):122–127. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198002000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard R. A., Ballard P. L., Creasy R. K., Padbury J., Polk D. H., Bracken M., Moya F. R., Gross I. Respiratory disease in very-low-birthweight infants after prenatal thyrotropin-releasing hormone and glucocorticoid. TRH Study Group. Lancet. 1992 Feb 29;339(8792):510–515. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90337-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk C., Grundy M. 'High risk' lecithin/sphingomyelin ratios associated with neonatal diaphragmatic hernia. Case reports. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1982 Mar;89(3):250–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1982.tb03626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozanski B. S., Jones J. G., Gilmour C. H., Balsan M. J., Vazquez R. L., Israel B. A., Newman B., Mimouni F. B., Guthrie R. D. Effect of pulse dexamethasone therapy on the incidence and severity of chronic lung disease in the very low birth weight infant. J Pediatr. 1995 May;126(5 Pt 1):769–776. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70410-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFiore J. W., Fauza D. O., Slavin R., Peters C. A., Fackler J. C., Wilson J. M. Experimental fetal tracheal ligation reverses the structural and physiological effects of pulmonary hypoplasia in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 1994 Feb;29(2):248–257. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(94)90328-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George D. K., Cooney T. P., Chiu B. K., Thurlbeck W. M. Hypoplasia and immaturity of the terminal lung unit (acinus) in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987 Oct;136(4):947–950. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.4.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldspink D. F. Pre- and post-natal growth and protein turnover in the lung of the rat. Biochem J. 1987 Feb 15;242(1):275–279. doi: 10.1042/bj2420275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison M. R., Adzick N. S., Estes J. M., Howell L. J. A prospective study of the outcome for fetuses with diaphragmatic hernia. JAMA. 1994 Feb 2;271(5):382–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison M. R., Adzick N. S., Longaker M. T., Goldberg J. D., Rosen M. A., Filly R. A., Evans M. I., Golbus M. S. Successful repair in utero of a fetal diaphragmatic hernia after removal of herniated viscera from the left thorax. N Engl J Med. 1990 May 31;322(22):1582–1584. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005313222207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison M. R., Bjordal R. I., Langmark F., Knutrud O. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: the hidden mortality. J Pediatr Surg. 1978 Jun;13(3):227–230. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(78)80391-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison M. R., Jester J. A., Ross N. A. Correction of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in utero. I. The model: intrathoracic balloon produces fatal pulmonary hypoplasia. Surgery. 1980 Jul;88(1):174–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisanaga S., Shimokawa H., Kashiwabara Y., Maesato S., Nakano H. Unexpectedly low lecithin/sphingomyelin ratio associated with fetal diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984 Aug 15;149(8):905–906. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(84)90614-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami M., Polk D., Tabor B., Lewis J., Yamada T., Jobe A. Corticosteroid and thyrotropin-releasing hormone effects on preterm sheep lung function. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1991 May;70(5):2268–2278. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.5.2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppe J. G., Smolders-de Haas H., Kloosterman G. J. Effects of glucocorticoids during pregnancy on the outcome of the children directly after birth and in the long run. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1977;7(5):293–299. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(77)90012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liggins G. C., Howie R. N. A controlled trial of antepartum glucocorticoid treatment for prevention of the respiratory distress syndrome in premature infants. Pediatrics. 1972 Oct;50(4):515–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liggins G. C. Premature delivery of foetal lambs infused with glucocorticoids. J Endocrinol. 1969 Dec;45(4):515–523. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0450515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liggins G. C., Schellenberg J. C., Manzai M., Kitterman J. A., Lee C. C. Synergism of cortisol and thyrotropin-releasing hormone in lung maturation in fetal sheep. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1988 Oct;65(4):1880–1884. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.65.4.1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losty P. D., Suen H. C., Manganaro T. F., Donahoe P. K., Schnitzer J. J. Prenatal hormonal therapy improves pulmonary compliance in the nitrofen-induced CDH rat model. J Pediatr Surg. 1995 Mar;30(3):420–426. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(95)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund D. P., Mitchell J., Kharasch V., Quigley S., Kuehn M., Wilson J. M. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: the hidden morbidity. J Pediatr Surg. 1994 Feb;29(2):258–264. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(94)90329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metkus A. P., Esserman L., Sola A., Harrison M. R., Adzick N. S. Cost per anomaly: what does a diaphragmatic hernia cost? J Pediatr Surg. 1995 Feb;30(2):226–230. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(95)90565-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama D. K., Motoyama E. K., Tagge E. M. Effect of preoperative stabilization on respiratory system compliance and outcome in newborn infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr. 1991 May;118(5):793–799. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schellenberg J. C., Liggins G. C., Manzai M., Kitterman J. A., Lee C. C. Synergistic hormonal effects on lung maturation in fetal sheep. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1988 Jul;65(1):94–100. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.65.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzer J. J., Kikiros C. S., Short B. L., O'Brien A., Anderson K. D., Newman K. D. Experience with abdominal wall closure for patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia repaired on ECMO. J Pediatr Surg. 1995 Jan;30(1):19–22. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(95)90600-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soper R. T., Pringle K. C., Scofield J. C. Creation and repair of diaphragmatic hernia in the fetal lamb: techniques and survival. J Pediatr Surg. 1984 Feb;19(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(84)80011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suen H. C., Bloch K. D., Donahoe P. K. Antenatal glucocorticoid corrects pulmonary immaturity in experimentally induced congenital diaphragmatic hernia in rats. Pediatr Res. 1994 May;35(5):523–529. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199405000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suen H. C., Catlin E. A., Ryan D. P., Wain J. C., Donahoe P. K. Biochemical immaturity of lungs in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 1993 Mar;28(3):471–477. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(93)90250-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suen H. C., Losty P. D., Donahoe P. K., Schnitzer J. J. Accurate method to study static volume-pressure relationships in small fetal and neonatal animals. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1994 Aug;77(2):1036–1043. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.2.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M. R., Chan G. M., Book L. S. Comparison of macronutrient concentration of preterm human milk between two milk expression techniques and two techniques for quantitation of energy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1986 Jul-Aug;5(4):597–601. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198607000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigglesworth J. S., Desai R., Guerrini P. Fetal lung hypoplasia: biochemical and structural variations and their possible significance. Arch Dis Child. 1981 Aug;56(8):606–615. doi: 10.1136/adc.56.8.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. M., Lund D. P., Lillehei C. W., Vacanti J. P. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: predictors of severity in the ECMO era. J Pediatr Surg. 1991 Sep;26(9):1028–1034. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(91)90667-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh T. F., Torre J. A., Rastogi A., Anyebuno M. A., Pildes R. S. Early postnatal dexamethasone therapy in premature infants with severe respiratory distress syndrome: a double-blind, controlled study. J Pediatr. 1990 Aug;117(2 Pt 1):273–282. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80547-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]