Abstract

Background

Handgrip strength (HGS) is a critical determinant of muscle function and has been strongly associated with various health outcomes, including health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in older adults. Although previous studies have explored the relationship between HGS and HRQoL, there is limited research on multiple muscle strength indicators in older Korean adults. In this study, we aimed to investigate the associations between multiple muscle strength indicators—maximal and relative HGS, dynapenia, and HGS asymmetry—and HRQoL in older Korean adults.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, we utilized data of 4,260 community-dwelling individuals aged ≥ 65 years who participated in the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) 2016–2018. We assessed muscle strength using a digital dynamometer and defined dynapenia according to the criteria established by the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia. HGS asymmetry was characterized by an interlimb difference of > 10%. HRQoL was evaluated using the EuroQol 5-Dimension (EQ-5D) index. Multivariable logistic regression models were employed to assess the associations between muscle strength indices and the high-risk group for low HRQoL (EQ-5D index ≤ 0.677), adjusting for potential confounders.

Results

Of the 4,260 participants, 56.5% were female; 17.4% aged ≥ 80 years. A total of 8.3% of the participants were categorized as being at high risk for low HRQoL. Lower maximal HGS (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 1.065, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.023–1.108) and lower relative HGS (aOR = 1.136, 95% CI = 1.026–1.257) were significantly associated with poor HRQoL in women. Furthermore, dynapenia was independently correlated with a higher risk of impaired HRQoL in women (aOR = 1.497, 95% CI = 1.064–2.106), whereas no significant association was observed in men. HGS asymmetry was not significantly associated with HRQoL in either sex after adjusting for confounders.

Conclusions

Reduced HGS and the presence of dynapenia were significantly associated with lower HRQoL, particularly among women. These findings highlight the critical role of muscle strength in maintaining the well-being of aging populations. Further longitudinal studies are warranted to validate these associations and elucidate potential causal mechanisms.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12877-025-06218-8.

Keywords: Health-related quality of life, Muscle strength, Aging, KNHANES

Background

Korea is undergoing rapid population aging, with the proportion of adults aged ≥ 65 years rising from 17.9% in 2022 to 18.4% in 2023, approaching the 20% threshold that defines a super-aged society [1, 2]. This demographic shift, driven by declining birth rates and increasing life expectancy, poses significant challenges to the nation’s economy, healthcare system, and social welfare infrastructure [3, 4]. One of the key challenges is maintaining health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in older adults, which is essential for independence, physical functioning, and overall well-being [5, 6]. At a societal level, improved HRQoL can reduce healthcare burdens and promote healthy aging [7, 8].

Among the various determinants of HRQoL, muscle strength is a critical factor. Studies have demonstrated that declining muscle strength is associated with greater disability, reduced mobility, and higher mortality risk [9, 10]. Conversely, individuals with higher muscle strength levels exhibit better physical performance and greater independence in daily activities, leading to enhanced HRQoL [11]. Furthermore, research suggests that muscle strength plays a more significant role compared with muscle mass in determining physical function and quality of life (QoL) in older adults, highlighting the importance for strength-based interventions [12]. This underscores the clinical significance of assessing and preserving muscle strength as a preventive strategy to maintain HRQoL and mitigate age-related functional decline.

Handgrip strength (HGS) is a widely used indicator of muscle strength, with both absolute and relative HGS gaining increasing attention in HRQoL research [13]. In this study, HGS was used as a proxy for overall muscle strength, as it reflects functional capacity and has been validated in older populations [12]. Additionally, HGS asymmetry is emerging as a potential marker for physical dysfunction and impaired QoL [14].

Despite the clinical relevance of these measures, few studies have comprehensively assessed the associations between diverse muscle strength indices and HRQoL in older adults. This study was conducted to fill a gap in the literature on the combined role of multiple strength indicators in HRQoL among older Korean adults. To address this gap, we aimed to investigate the relationships between HRQoL and multiple muscle strength indicators—including maximal HGS, relative HGS, dynapenia, and HGS asymmetry—in a nationally representative sample of older Korean adults. In particular, we performed sex-stratified analyses to explore potential sex-specific associations. Additionally, we sought to provide a comprehensive understanding about how these strength measures could be related to HRQoL in later life, with the goal of informing tailored strategies for supporting healthy aging.

Methods

Data source and study population

The present study utilized data from the seventh Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VII), conducted between 2016 and 2018. Since 1998, the KNHANES has been systematically administered to evaluate the health and nutritional status of the civilian, non-institutionalized Korean population. The KNHANES VII employed a cross-sectional, nationally representative design under the supervision of the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC; now Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency [KDCA]). A stratified, multistage probability-cluster sampling approach was implemented to recruit 31,689 individuals across 13,248 households. Among them, 24,269 participants consented to participate in the survey, yielding a response rate of 76.5%.

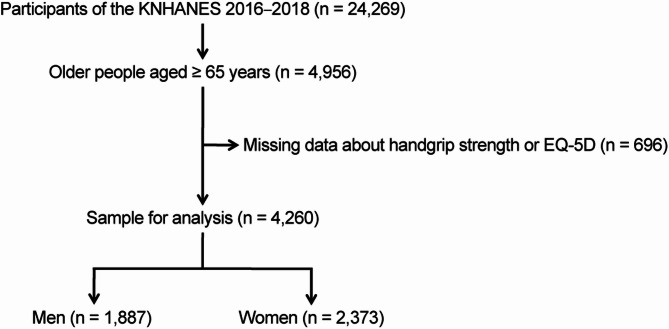

In this study, we included individuals aged ≥ 65 years from the KNHANES VII (n = 4,956). Participants with incomplete data on HGS and HRQoL (n = 696) were excluded following listwise deletion. According to the KNHANES protocol, individuals with conditions precluding valid grip strength measurement—such as upper limb amputation, paralysis, casts or splints, or recent hand/wrist surgery—were identified through pre-examination screening and excluded from testing. These participants were not included in the dataset and thereby excluded from the analytic sample. Given that missing values in these variables were frequently associated with missing data in other measures, their exclusion was deemed appropriate. Ultimately, data of 4,260 participants were retained for final analysis. The detailed selection process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of participant selection from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2016–2018. Adults aged ≥ 65 years with complete data on handgrip strength and EQ-5D-3L were included in the final analytic sample (n = 4,260), which was stratified by sex

The KNHANES was conducted in full compliance with the Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation, and all data were fully de-identified before public release. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hallym University Chuncheon Sacred Heart Hospital (CHUNCHEON 2024-11-003).

Assessment of HRQoL

The EuroQol 5-Dimension 3-Level (EQ-5D-3L) instrument and EQ-5D index scores were employed to evaluate HRQoL in older Korean adults. The EQ-5D-3L framework comprised five distinct health dimensions: mobility (MO), self-care (SC), usual activities (UA), pain/discomfort (PD), and anxiety/depression (AD) [15, 16]. Each dimension was rated on a three-level scale: no problems (= 1), some problems (= 2), and extreme problems (= 3). The participants were asked to report their current health status by selecting the statement that best described their condition in each of the five dimensions. This selection process generated a 1-digit score for each dimension, which could be combined into a 5-digit code representing the participant’s overall health state.

The EQ-5D index was derived by applying specific weighting factors to the five EQ-5D dimensions, generating a range of possible health states from 11111 to 33333. The index had a bounded scale from − 1 to + 1, with 1.0 representing the optimal health state, where all five dimensions indicated no problems (11111). In this study, EQ-5D index scores were computed utilizing predefined quality weights provided by the KCDC (now KDCA). The calculation formula was as follows: EQ-5D index = 1– (0.050 + 0.096×MO2 + 0.418×MO3 + 0.046×SC2 + 0.136×SC3 + 0.051×UA2 + 0.208×UA3 + 0.037×PD2 + 0.151×PD3 + 0.043×AD2 + 0.158×AD3 + 0.05×N3), where N3 represents the presence of extreme problems in any of the five health dimensions. The quality weights used in this formula were established through a population-based valuation study conducted by Lee et al. [17], which determined the preference weights for the Korean EQ-5D-3L based on a nationally representative sample. These validated weights were subsequently applied in this study to compute EQ-5D-3L index scores specific to the Korean population.

In our analysis, the EQ-5D index scores among the participants ranged between − 0.171 and 1.0, with a maximum value of 1.0 representing the highest possible health state. The distribution of EQ-5D index scores exhibited a left-skewed pattern, indicating a higher concentration of values near the upper end of the scale. The participants with EQ-5D index scores of 0.677 or lower were classified as being at a relatively high risk of deteriorated QoL. Although there was no universally established cutoff for the EQ-5D index, a threshold was necessary to effectively identify individuals in need of targeted health interventions. Rather than relying solely on statistical segmentation, we applied a functional classification approach. In the EQ-5D system, a person reporting no problems in any domain (11111) represented the best health state, while extreme problems in all domains (33333) represented the worst state. A response pattern of 22222, indicating “some problems” in all five dimensions, corresponded to an index score of 0.677. This value served as a meaningful threshold where functional impairment became evident, making it an appropriate criterion for identifying individuals requiring intervention. Although alternative methods such as percentile-based thresholds were considered, they might vary across populations and lack consistent clinical interpretation. In contrast, the “22222” response pattern corresponded to a moderate level of impairment across all five EQ-5D-3L domains and had been cited in prior literature as a functionally meaningful health state [15, 17]. Thus, we selected 0.677 as a clinically relevant threshold to functionally classify individuals at high risk, facilitating targeted health interventions.

Muscle strength index

Muscle strength was measured using a digital grip strength dynamometer (TTK 5401; Takei Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Before the assessment, trained examiners instructed the participants to remove any jewelry from their fingers or wrists to prevent interference. The examiners then provided a comprehensive explanation about the measurement procedure. The participants were positioned upright with their arms relaxed at their sides while holding the dynamometer. They were instructed to exert maximum grip force for 3 s, repeating the measurement three times per hand. To ensure accuracy, a minimum resting interval of 60 s was maintained between each trial.

Regarding analysis, the highest recorded grip strength value from the dominant hand was used. Relative HGS was computed by normalizing grip strength to the participant’s body mass index (BMI). In accordance with the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia criteria, dynapenia was defined as an HGS below 28 kg in men and less than 18 kg in women [18]. Muscle mass was not measured in this study. Accordingly, dynapenia was defined based solely on low muscle strength, irrespective of muscle mass. This reflected clinically relevant muscle weakness that increased risks of impaired mobility and daily activity limitations, even without reduced muscle mass [10]. In this study, HGS asymmetry was determined based on a previously established threshold, defining asymmetry as a > 10% strength difference between hands [19, 20]. Participants exhibiting a strength difference exceeding this cutoff in either hand were classified as having HGS asymmetry. HGS asymmetry served as a surrogate marker for neuromuscular imbalance and might indicate early functional decline [14].

Covariates

Sociodemographic variables analyzed in this study included age, sex, educational level, employment status, economic status, and marital status. Current health status was evaluated using the modified Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), along with additional health-related factors such as unmet medical needs, stress levels, hearing impairment, chewing difficulty, unintentional weight loss, BMI, waist circumference, and waist-to-height ratio. Lifestyle factors incorporated in the analysis comprised smoking status, alcohol consumption, participation in aerobic physical activity, and engagement in muscle-strengthening exercises. Detailed descriptions of variable measurements were obtained from the guidelines outlined on the KNHANES website (knhanes.kdca.go.kr/).

Statistical analysis

Given the complex sampling design of the KNHANES, all statistical analyses were performed using complex sample analysis methods, accounting for sampling weights, stratification, and cluster sampling. Estimates were weighted according to the sampling rate, response rate, and distribution of age, sex, and regional proportions within the reference population. Continuous variables are summarized as means ± standard error (SE), while categorical variables are presented as weighted proportions (%) with SE. Differences in general characteristics between men and women were evaluated using the Student’s t-test for continuous variables and the Rao-Scott chi-square test for categorical variables. Associations between muscle strength indices and the high-risk group for HRQoL were analyzed separately according to sex. HGS was modeled as a continuous variable in all logistic regression analyses; estimated odds ratios (ORs) reflected the change in risk associated with each 1-kg lower value. Age-adjusted logistic regression models were employed to assess these associations, while multivariable logistic regression models were used to adjust for potential confounding factors. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05 for all two-sided tests. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

General characteristics of the study population

Table 1 summarizes the general characteristics of the study population and sex-based comparisons. Of the 4,260 participants, 2,373 (56.5%) were female individuals; and 710 (17.4%) aged ≥ 80 years. A total of 8.3% of the participants were categorized as belonging to the high-risk HRQoL group, defined as having an EQ-5D index score of ≤ 0.677. A significant difference was observed in the prevalence of high-risk HRQoL between men (4.7%, 99 participants) and women (11.1%, 266 participants) (P < 0.001). The mean (SE) maximal HGS was 33.0 (0.1) kg in men and 19.4 (0.1) kg in women, while relative HGS was 1.41 (0.01) in men and 0.80 (0.01) in women. The prevalence of dynapenia was 23.3% in men and 38.2% in women, whereas HGS asymmetry was observed in 35.8% of men and 46.7% of women, both of which were significantly higher in women. There was no significant difference between sexes in household income (P = 0.775), modified CCI (P = 0.378), hearing impairment (P = 0.992), or unintentional weight loss (P = 0.752). However, most of the other variables were significantly different between men and women (all, P < 0.01).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, health-related, and lifestyle characteristics of the study population by sex

| Characteristics | Total | (n = 4260) | Men | (n = 1887) | Women | (n = 2373) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Sociodemographic factors] | ||||||||||

| Age (years) | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| ≥80 | 710 | 17.4 | (0.8) | 288 | 14.8 | (1.0) | 422 | 19.5 | (1.1) | |

| 75–79 | 987 | 23.7 | (0.8) | 432 | 20.7 | (1.0) | 555 | 26.0 | (1.1) | |

| 70–74 | 1166 | 25.5 | (0.8) | 532 | 27.2 | (1.1) | 634 | 24.2 | (1.0) | |

| 65–69 | 1397 | 33.4 | (0.9) | 635 | 37.3 | (1.4) | 762 | 30.3 | (1.1) | |

| Education: ≤middle school | 3080 | 72.4 | (1.1) | 1089 | 57.3 | (1.4) | 1991 | 83.9 | (1.1) | < 0.001 |

| Employment: no | 2811 | 67.8 | (1.0) | 1091 | 58.6 | (1.5) | 1720 | 74.8 | (1.1) | < 0.001 |

| Household income | 0.775 | |||||||||

| Lowest quintile | 834 | 20.6 | (0.8) | 371 | 20.6 | (1.1) | 463 | 20.6 | (0.9) | |

| Middle (Second–Fourth) | 2514 | 58.0 | (1.1) | 1117 | 58.5 | (1.4) | 1397 | 57.6 | (1.2) | |

| Highest quintile | 889 | 21.4 | (1.1) | 388 | 20.9 | (1.3) | 501 | 21.8 | (1.2) | |

| Spouse: no | 1397 | 34.8 | (1.1) | 239 | 12.5 | (0.9) | 1158 | 52.1 | (1.3) | < 0.001 |

| [Current health status] | ||||||||||

| Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0.378 | |||||||||

| ≥2 | 375 | 8.5 | (0.5) | 191 | 9.3 | (0.7) | 184 | 7.9 | (0.7) | |

| 1 | 1048 | 24.5 | (0.8) | 467 | 24.5 | (1.2) | 581 | 24.5 | (1.0) | |

| 0 | 2837 | 67.0 | (0.9) | 1229 | 66.2 | (1.3) | 1608 | 67.6 | (1.2) | |

| Unmet medical needs: yes | 433 | 10.0 | (0.6) | 121 | 6.4 | (0.7) | 312 | 12.8 | (0.8) | < 0.001 |

| Stress: yes | 794 | 18.7 | (0.7) | 235 | 12.5 | (0.8) | 559 | 23.5 | (1.1) | < 0.001 |

| Hearing impairment: yes | 1360 | 31.6 | (0.9) | 622 | 31.6 | (1.3) | 738 | 31.5 | (1.2) | 0.992 |

| Chewing difficulty: yes | 1759 | 40.5 | (1.0) | 748 | 38.0 | (1.3) | 1011 | 42.5 | (1.2) | 0.008 |

| Unintentional weight loss: ≥3 kg/year | 604 | 14.7 | (0.7) | 273 | 14.4 | (1.0) | 331 | 14.9 | (1.0) | 0.752 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.1 | ± 0.1 | 23.7 | ± 0.1 | 24.5 | ± 0.1 | < 0.001 | |||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 85.5 | ± 0.2 | 86.7 | ± 0.2 | 84.3 | ± 0.2 | < 0.001 | |||

| Waist-to-height ratio, ×100 | 54.0 | ± 0.1 | 52.4 | ± 0.1 | 55.6 | ± 0.2 | < 0.001 | |||

| [Lifestyle factors] | ||||||||||

| Smoking | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Current smoker | 386 | 9.0 | (0.5) | 338 | 18.1 | (1.1) | 48 | 2.0 | (0.4) | |

| Ex-smoker | 1237 | 28.5 | (0.8) | 1163 | 61.4 | (1.3) | 74 | 3.0 | (0.4) | |

| Non-smoker | 2612 | 62.5 | (0.8) | 377 | 20.5 | (1.1) | 2235 | 95.0 | (0.6) | |

| Alcohol consumption: ≥2 days/week | 707 | 16.9 | (0.7) | 596 | 32.9 | (1.3) | 111 | 4.6 | (0.5) | < 0.001 |

| Regular aerobic physical activity: no | 2925 | 69.3 | (0.9) | 1200 | 63.4 | (1.4) | 1725 | 73.9 | (1.1) | < 0.001 |

| Muscle strengthening: ≤1 time/week | 3513 | 82.2 | (0.8) | 1362 | 71.4 | (1.2) | 2151 | 90.5 | (0.8) | < 0.001 |

| [Muscle strength index] | ||||||||||

| Maximum handgrip strength (kg) | 26.2 | ± 0.1 | 33.0 | ± 0.2 | 19.4 | ± 0.1 | < 0.001 | |||

| Relative handgrip strength, ×10 | 11.0 | ± 0.1 | 14.1 | ± 0.1 | 8.0 | ± 0.1 | < 0.001 | |||

| Dynapenia: yes | 1319 | 31.7 | (1.1) | 456 | 23.3 | (1.2) | 863 | 38.2 | (1.6) | < 0.001 |

| Handgrip strength asymmetry: yes | 1812 | 42.0 | (0.9) | 689 | 35.8 | (1.4) | 1123 | 46.7 | (1.2) | < 0.001 |

| [Health-related QoL] | ||||||||||

| 5D-EQ index: high risk group | 365 | 8.3 | (0.5) | 99 | 4.7 | (0.5) | 266 | 11.1 | (0.8) | < 0.001 |

Data are presented as the estimated mean ± standard error or the unweighted frequency, estimated percentage (standard error), as appropriate. P-values are derived from the Student’s t-test for means or the Pearson chi-square test with the Rao-Scott correction using F statistic for proportions. High-risk group defined as EQ-5D index ≤ 0.677. EQ-5D, EuroQol 5-Dimension; QoL, quality of life

Prevalence of high-risk HRQoL across different categories

Table 2 presents the estimated differences in the prevalence of various variables in the high-risk HRQoL group. Both men and women with dynapenia exhibited a significantly higher prevalence of high-risk HRQoL compared with those without dynapenia (all, P < 0.001). Regarding HGS asymmetry, a significantly high prevalence of high-risk HRQoL was observed only in women (P = 0.006). The prevalence of high-risk HRQoL was positively associated with advanced age, lower educational attainment, unemployment, higher modified CCI, unmet medical needs, stress, hearing impairment, chewing difficulty, and unintentional weight loss. Conversely, individuals who engaged in regular aerobic or muscle-strengthening exercises had a lower prevalence of high-risk HRQoL. Regardless of sex, both mean maximal HGS and relative HGS were significantly lower in the high-risk HRQoL group compared with the reference group (Table 3).

Table 2.

Factors associated with high-risk group for health-related quality of life among older adults by sex

| Characteristics | Categories | Men (n = 1887) | P-value | Women (n = 2373) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ≥ 80 | 10.9 | (2.1) | < 0.001 | 20.8 | (2.4) | < 0.001 |

| 75–79 | 7.8 | (1.3) | 10.8 | (1.5) | |||

| 70–74 | 2.6 | (0.7) | 9.3 | (1.4) | |||

| 65–69 | 2.0 | (0.6) | 6.7 | (1.1) | |||

| Education | ≤Middle school | 5.6 | (0.8) | 0.009 | 12.5 | (0.9) | < 0.001 |

| ≥High school | 2.9 | (0.6) | 3.1 | (1.1) | |||

| Employment | No | 6.2 | (0.8) | < 0.001 | 11.9 | (1.0) | 0.013 |

| Yes | 1.9 | (0.5) | 8.0 | (1.2) | |||

| Household income | Lowest quintile | 6.1 | (1.3) | 0.334 | 17.2 | (2.2) | < 0.001 |

| Middle (Second-Fourth) | 4.7 | (0.7) | 10.6 | (0.9) | |||

| Highest quintile | 3.4 | (1.2) | 6.2 | (1.2) | |||

| Spouse | No | 6.6 | (2.1) | 0.240 | 14.4 | (1.2) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 4.4 | (0.5) | 7.7 | (0.9) | |||

| Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index | ≥ 2 | 11.5 | (2.6) | < 0.001 | 18.6 | (3.0) | < 0.001 |

| 1 | 5.0 | (1.0) | 13.8 | (1.7) | |||

| 0 | 3.6 | (0.6) | 9.3 | (0.9) | |||

| Unmet medical needs | Yes | 11.8 | (2.9) | < 0.001 | 21.6 | (2.7) | < 0.001 |

| No | 4.2 | (0.5) | 9.6 | (0.8) | |||

| Stress | Yes | 11.6 | (2.1) | < 0.001 | 23.0 | (2.1) | < 0.001 |

| No | 3.6 | (0.5) | 7.2 | (0.8) | |||

| Hearing impairment | Yes | 7.2 | (1.1) | < 0.001 | 17.2 | (1.7) | < 0.001 |

| No | 3.5 | (0.6) | 8.4 | (0.8) | |||

| Chewing difficulty | Yes | 7.5 | (1.1) | < 0.001 | 17.5 | (1.4) | < 0.001 |

| No | 2.9 | (0.5) | 6.0 | (0.7) | |||

| Unintentional weight loss | ≥ 3 kg/year | 7.8 | (1.7) | 0.012 | 16.8 | (2.4) | < 0.001 |

| < 3 kg/year | 4.1 | (0.5) | 9.5 | (0.8) | |||

| Smoking | Current smoker | 4.2 | (1.1) | 0.834 | 20.3 | (6.9) | 0.140 |

| Ex-smoker | 4.9 | (0.7) | 13.0 | (4.0) | |||

| Non-smoker | 4.3 | (1.1) | 10.6 | (0.8) | |||

| Alcohol consumption | ≥ 2 days/week | 2.4 | (0.6) | 0.001 | 6.7 | (2.9) | 0.219 |

| < 2 days/week | 5.7 | (0.7) | 11.1 | (0.8) | |||

| Aerobic physical activity | None | 5.8 | (0.8) | 0.001 | 13.3 | (1.1) | < 0.001 |

| Regular | 2.4 | (0.6) | 5.2 | (1.0) | |||

| Muscle strengthening | < 2 days/week | 5.7 | (0.7) | < 0.001 | 11.6 | (0.9) | 0.032 |

| ≥ 2 days/week | 1.7 | (0.6) | 6.4 | (1.8) | |||

| Dynapenia | Yes | 10.0 | (1.5) | < 0.001 | 16.5 | (1.4) | < 0.001 |

| No | 3.1 | (0.5) | 7.8 | (0.9) | |||

| Handgrip strength asymmetry | Yes | 5.0 | (0.8) | 0.634 | 13.5 | (1.3) | 0.006 |

| No | 4.5 | (0.6) | 9.0 | (1.0) | |||

Data are expressed as the estimated percentage (standard error). P-values are derived from the Pearson chi-square test with the Rao-Scott correction using F statistic for proportions. High-risk group defined as EQ-5D index ≤ 0.677

Table 3.

Comparison of muscle strength indices between high-risk and reference health-related quality of life groups by sex

| Characteristics | Men | Women | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High risk group | Reference group | P-value | High risk group | Reference group | P-value | |||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.7 | ± 0.4 | 23.7 | ± 0.1 | 0.975 | 24.9 | ± 0.3 | 24.5 | ± 0.1 | 0.143 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 87.9 | ± 1.2 | 86.7 | ± 0.2 | 0.334 | 85.5 | ± 0.7 | 84.1 | ± 0.2 | 0.066 |

| Waist-to-height ratio, ×100 | 53.3 | ± 0.7 | 52.3 | ± 0.1 | 0.187 | 57.1 | ± 0.5 | 55.4 | ± 0.2 | 0.002 |

| Maximum handgrip strength (kg) | 28.8 | ± 0.9 | 33.2 | ± 0.2 | < 0.001 | 17.1 | ± 0.3 | 19.7 | ± 0.1 | < 0.001 |

| Relative handgrip strength, ×10 | 12.2 | ± 0.4 | 14.2 | ± 0.1 | < 0.001 | 7.1 | ± 0.2 | 8.1 | ± 0.1 | < 0.001 |

Data are expressed as the estimated mean ± standard error. P-values are derived from the Student’s t-test for means

Association between muscle strength indices and high-risk HRQoL

Table 4 presents the results of the logistic regression analyses examining the associations between muscle strength indices and the high-risk HRQoL group. Age-adjusted analyses revealed significant associations between all muscle strength indices and HRQoL, except for HGS asymmetry in older men. In the multivariable-adjusted model, the interaction terms between muscle strength indices and sex were not statistically significant (all, P ≥ 0.05). However, in sex-stratified analyses, significant associations were observed only in women, whereas no significant associations were found in men. Among older women, dynapenia was associated with a higher likelihood of belonging to the high-risk HRQoL group, with an adjusted OR of 1.497 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.064–2.106). Although the adjusted OR for HGS asymmetry in older women was 1.392 (95% CI, 0.971–1.996), the association was not significant. Furthermore, in older women, each 1-kg lower HGS was associated with a 1.065-fold increase in the odds of high-risk HRQoL (95% CI, 1.023–1.108), while each 0.1-unit lower relative HGS was associated with a 1.136-fold increase (95% CI, 1.026–1.257). In contrast, no significant associations were observed between muscle strength indices and HRQoL in older men.

Table 4.

Association between muscle strength indices and high-risk Korea National health and nutrition examination survey in older Korean adults stratified by sex

| Characteristics | Men | Women | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

| Maximum handgrip strength (per 1-kg lower) | 1.054 | (1.005 − 1.104) | 1.010 | (0.954 − 1.069) | 1.094 | (1.055 − 1.135) | 1.065 | (1.023 − 1.108) |

| Relative handgrip strength, ×10 (per 1-unit lower) | 1.154 | (1.046 − 1.273) | 1.091 | (0.965 − 1.233) | 1.222 | (1.115 − 1.341) | 1.136 | (1.026 − 1.257) |

| Dynapenia (< 28/18 kg) | 2.146 | (1.221 − 3.772) | 1.243 | (0.649 − 2.380) | 1.793 | (1.305 − 2.465) | 1.497 | (1.064 − 2.106) |

| Handgrip strength asymmetry (> 10%) | 1.027 | (0.645 − 1.636) | 0.848 | (0.499 − 1.441) | 1.456 | (1.054 − 2.011) | 1.392 | (0.971 − 1.996) |

Data are presented as adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) derived from logistic regression. Odds ratios for continuous variables (e.g., maximum handgrip strength, relative handgrip strength ×10) reflect the change in risk per unit lower value (i.e., per 1-kg lower maximal HGS or per 1-unit lower scaled relative HGS). Model 1 was adjusted for age. Model 2 was adjusted for age, education attainment, employment status, household income (only women), marital status (only women), modified Charlson Comorbidity Index, unmet medical needs, stress, hearing impairment, chewing difficulty, unintentional weight loss, alcohol consumption (only men), aerobic physical activity, and muscle strengthening. High-risk group defined as EQ-5D index ≤ 0.677

Discussion

We evaluated the associations between multiple muscle strength indicators and HRQoL in older Korean adults, offering critical insights into the influence of muscle strength on QoL in this population. Our findings revealed significant associations between maximum HGS, relative HGS, and dynapenia with reduced HRQoL, underscoring the importance for muscle strength as a determinant of well-being in older adults. Importantly, these associations exhibited notable sex-specific differences. Logistic regression analysis revealed that abnormalities in muscle strength indicators were significantly associated with an increased risk of low HRQoL in older women but not in older men. Specifically, older women with dynapenia exhibited an adjusted OR of 1.497 for belonging to the high-risk HRQoL group. Furthermore, each 1-kg lower maximal HGS and each 0.1-unit lower relative HGS were associated with 1.065-fold and 1.136-fold increases in the odds of high-risk HRQoL, respectively. Conversely, HGS asymmetry was not significantly associated with HRQoL.

The relationship between muscle strength and HRQoL in older adults has been extensively studied, with various HGS measures recognized as key indicators. Maximal HGS, a simple yet reliable measure of overall muscle strength, has consistently demonstrated positive associations with multiple health outcomes, including HRQoL. Previous studies have identified positive correlations between HGS and HRQoL and have established threshold values critical for maintaining optimal QoL [9, 21], findings that align with those in the present study. These results underscore the role of maximal HGS as a significant predictor of HRQoL in older adults. Collectively, the evidence highlights muscle strength as a critical determinant of HRQoL and emphasizes the potential benefits of interventions aimed to preserve or enhance muscle strength for promoting QoL in aging populations. Although previous studies have primarily examined absolute HGS in pooled or unstratified samples, our study incorporated multiple strength indicators—including relative HGS, dynapenia, and asymmetry—and applied a sex-stratified analytic framework. The associations with HRQoL were particularly pronounced in women, underscoring the need for sex-specific evaluation and targeted interventions.

The association between relative HGS and HRQoL in older adults has garnered increasing attention in recent years, with growing evidence supporting a strong and consistent positive relationship [22–24]. Relative HGS, which normalizes muscle strength to body size, offers a more precise representation of an individual’s physiological capacity and its implications for daily functioning and health outcomes [25, 26]. Furthermore, relative HGS has emerged as a superior predictor of all-cause mortality and metabolic risk in older adults, highlighting its clinical and public health relevance [26, 27]. Accounting for variations in body composition, relative HGS provides a more nuanced assessment of functional muscle strength than absolute measures such as maximal HGS, particularly in aging populations experiencing muscle mass reduction and fat mass accumulation. These findings emphasize the critical role of relative HGS in multiple dimensions of HRQoL. Interventions designed to preserve or enhance relative HGS might significantly contribute to improving the well-being of older populations. Additionally, relative HGS shows promise as a practical screening tool for identifying individuals at risk of HRQoL decline, thereby facilitating early intervention and targeted care.

Dynapenia has a significant impact on HRQoL in older adults, contributing to declines in physical and functional well-being, daily living activities, and overall QoL. Its effects are further exacerbated in conditions such as obesity and diabetes, where it accelerates physical QoL deterioration [28, 29]. Our findings revealed that dynapenia was significantly associated with lower HRQoL in women, likely reflecting its influence on physical function and independence. Among community-dwelling older adults, dynapenia is associated with lower physical performance, reinforcing the link between muscle weakness and functional impairment [30]. These findings underscore the pivotal role of dynapenia in physical functioning, a key determinant of HRQoL in aging populations. Interventions targeting the prevention or attenuation of dynapenia might help preserve physical function and improve QoL in older adults. Future research should prioritize the development of targeted strategies to mitigate dynapenia and evaluate its potential as a predictive marker for HRQoL decline.

We found no significant association between HGS asymmetry and HRQoL in older adults, contrary to prior research that reported associations between HGS asymmetry and adverse health outcomes [31, 32]. Several factors might account for this discrepancy. First, our definition of asymmetry as a difference of > 10% between hands, which aligns with previous studies [33], might have influenced the results. Alternative threshold values or continuous measures of asymmetry could yield different findings. Second, older adults might develop compensatory mechanisms to mitigate the adverse effects of HGS asymmetry on daily functioning and QoL. Lastly, the cross-sectional design of our study limits our ability to assess the long-term impact of HGS asymmetry on HRQoL. Although not statistically significant, asymmetry might still influence functional ability through impaired coordination or motor control, particularly in individuals with frailty. To assess the robustness of our asymmetry definition, we conducted additional sensitivity analyses using alternative thresholds (> 15%, > 20%) and a continuous variable. A significant association with high-risk HRQoL was found only in women at the > 20% cut-off. Moreover, asymmetry prevalence was higher among participants with dynapenia (particularly men) and those with EQ-5D ≤ 0.677 (particularly women) (tables not included). These findings suggest that while asymmetry might not consistently predict HRQoL across the population, it could reflect underlying physical vulnerability in specific subgroups. Correlation analysis with EQ-5D index was not performed due to methodological limitations in estimating valid coefficients from complex sample data. Longitudinal studies are warranted to determine whether the effects of asymmetry on QoL become more pronounced over time. Furthermore, it is plausible that older women might be more functionally affected by HGS asymmetry due to generally lower muscle reserves, a higher prevalence of dynapenia, and diminished hormonal protection after menopause. These biological differences might amplify the impact of asymmetry on physical performance and perceived QoL in women compared with men.

The observed sex-specific differences in the association between muscle strength indicators and HRQoL highlight the need for tailored approaches to muscle strength assessment and management in older adults. The stronger association between reduced muscle strength and lower HRQoL in older women suggests greater vulnerability to the physical and psychosocial consequences of muscle weakness [34]. Several factors likely contribute to this heightened susceptibility, including lower baseline muscle mass, hormonal differences, particularly the postmenopausal decline in estrogen, and greater age-related declines in muscle strength [10, 35, 36]. Additionally, the impact of reduced muscle strength on HRQoL in women may be exacerbated by socioeconomic and health-related factors [37].

In contrast, the weaker associations between muscle strength indicators and HRQoL observed in older men might reflect differences in the physiological and social determinants of well-being [38]. Biologically, older men tend to have higher baseline muscle strength and muscle mass, which might buffer the functional consequences of decline until more severe stages [10]. Behaviorally, men might underreport subjective impairments or perceive strength loss as less impactful on daily life. Methodologically, the lower prevalence of high-risk HRQoL in men might have limited the statistical power to detect associations. These factors might jointly explain the sex differences in strength–HRQoL relationships. In addition, higher baseline strength and a lower prevalence of dynapenia in men might act as protective factors. Greater employment participation and lower reported stress levels might also contribute to the maintenance of HRQoL despite the strength decline [37, 39]. These findings underscore the importance for sex-specific approaches to evaluating and supporting muscle function and perceived QoL. For instance, programs for older women may prioritize preserving or improving muscle strength through tailored resistance training, while interventions in men might focus on psychosocial and behavioral factors influencing QoL. Building on these observations, differentiated intervention strategies appear warranted. This sex-specific approach might enhance the effectiveness of public health interventions aimed to promote healthy aging and preserve functional independence in older adults.

This study has some limitations. First, its cross-sectional design precludes the ability to establish causal relationships between muscle strength indicators and HRQoL, making it susceptible to reverse causation. For instance, although low muscle strength might contribute to poor HRQoL, individuals with low HRQoL might also engage in reduced physical activity, leading to declines in muscle strength. Longitudinal studies are required to clarify these associations over time. Second, reliance on self-reported data in the KNHANES introduces potential biases, including recall bias and social desirability bias, which might have affected the accuracy of reported health and lifestyle factors. Additionally, participants with missing data on HGS and HRQoL were excluded from the analysis, potentially introducing selection bias. However, a comparison of baseline characteristics between excluded and included participants revealed no significant differences, suggesting minimal impact on the findings. Third, although HGS is a widely accepted indicator of muscle strength, it might not have fully captured the functional capacity of other muscle groups, particularly those in the lower body. Lastly, although we adjusted for key confounders, residual confounding might have persisted due to unmeasured factors, such as dietary intake, mental health status, and detailed socioeconomic indicators. Additionally, unreported comorbidities or genetic factors may have influenced the results. Addressing these limitations in future studies through comprehensive data collection, longitudinal designs, and advanced statistical methods would enhance the robustness and generalizability of the findings. Despite these limitations, this study has notable strengths. Utilizing KNHANES data ensured a nationally representative sample of older Korean adults, with analyses adjusted for the complex sampling design and sample weights, thereby improving generalizability. Furthermore, this study incorporated a comprehensive analysis of multiple muscle strength indicators, including maximal HGS, relative HGS, dynapenia, and HGS asymmetry. This multifaceted approach enabled a nuanced exploration of the relationship between muscle strength and HRQoL, providing a detailed understanding about how specific muscle strength deficits might impact QoL.

Additionally, classifying HRQoL levels with a focus on identifying high-risk groups in need of clinical intervention, the study enhances its practical applicability to developing targeted healthcare strategies. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that the absence of a universally accepted EQ-5D threshold might limit comparability across studies.

This study highlights muscle strength as a critical determinant of HRQoL in older adults, with notable sex-specific differences. Maximal HGS, relative HGS, and dynapenia were significantly associated with reduced HRQoL, particularly in women, underscoring the importance for muscle strength preservation. Routine muscle strength assessments could serve as practical tools for identifying at-risk individuals and guiding targeted interventions. Public health initiatives should prioritize resistance training, nutritional programs, and community-based strategies aimed at promoting physical activity and muscle strength to support healthy aging and mitigate healthcare burdens.

Conclusions

We outline the significant association between muscle strength indicators and HRQoL in older Korean adults, with greater vulnerability observed in women. These findings support the integration of muscle strength assessments into routine health evaluations and the implementation of sex-sensitive interventions to address muscle weakness and its impact on HRQoL. Future research should investigate causal relationships through longitudinal studies and examine additional strength measures, such as lower limb strength, to provide a more comprehensive understanding about the role of muscle function in aging populations.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants of the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and the staff of the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency for providing the data analyzed in the present study.

Abbreviations

- AD

anxiety/depression

- BMI

body mass index

- CCI

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- CI

confidence interval

- EQ-5D

EuroQol 5-Dimension

- EQ-5D-3L

EuroQol 5-Dimension 3-Level

- HGS

handgrip strength

- HRQoL

health-related quality of life

- KCDC

Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- KDCA

Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency

- MO

mobility

- OR

odds ratio

- PD

pain/discomfort

- QoL

quality of life

- SC

self-care

- KNHANES VII

seventh Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- SE

standard error

- UA

usual activities

Authors’ contributions

YSP was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, and writing the original draft. KY contributed to methodology and writing—review and editing. HJK was involved in writing—review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Hallym University Research Fund 2024 (grant number HURF-2024-63). The sponsor had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, and preparation of the paper.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the KNHANES website: https://knhanes.kdca.go.kr/knhanes/main.do.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The KNHANES data were collected with informed consent from all participants under the approval of the KCDC (now KDCA). This study was approved with an exemption from the Institutional Review Board of Hallym University Chuncheon Sacred Heart Hospital (CHUNCHEON 2024-11-003). All procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. This study used publicly available, de-identified data.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.National Health Insurance Service. 2024 National Health Insurance & Long-Term Care Insurance System Republic of Korea. National Health Insurance Service. Accessed 27 Dec 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Lancet Regional Health-Western Pacific. South korea’s population shift: challenges and opportunities. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2023;36:100865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baek JY, Lee E, Jung HW, Jang IY. Geriatrics fact sheet in Korea 2021. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2021;25:65–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim MJ, Lee S, Cheong HK, Jang SY, Kim HS, Oh IH. Healthcare utilization and costs according to frailty transitions after two years: a Korean frailty and aging cohort study. J Korean Med Sci. 2023;38: e191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noto S. Perspectives on aging and quality of life. Healthcare. 2023;11: 2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hart PD, Buck DJ. The effect of resistance training on health-related quality of life in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Promot Perspect. 2019;9:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dehi Aroogh M, Mohammadi Shahboulaghi F. Social participation of older adults: a concept analysis. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2020;8:55–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santhalingam S, Sivagurunathan S, Prathapan S, Kanagasabai S, Kamalarupan L. The effect of socioeconomic factors on quality of life of elderly in Jaffna district of Sri Lanka. PLoS Glob Public Health. 2022;2:e0000916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang S, Li T, Yang H, Wang J, Liu M, Wang S, et al. Association between muscle strength and health-related quality of life in a Chinese rural elderly population: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e026560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balogun S, Winzenberg T, Wills K, Scott D, Jones G, Callisaya ML, et al. Prospective associations of low muscle mass and strength with health-related quality of life over 10-year in community-dwelling older adults. Exp Gerontol. 2019;118:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petnehazy N, Barnes HN, Newman AB, Kritchevsky SB, Cummings SR, Hepplen RT, et al. Muscle mass, strength, power and physical performance and their association with quality of life in older adults, the study of muscle, mobility and aging (SOMMA). J Frailty Aging. 2024;13(4):384–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riviati N, Indra B. Relationship between muscle mass and muscle strength with physical performance in older adults: a systematic review. SAGE Open Med. 2023;11:20503121231214650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esteban-Simon A, Diez-Fernandez DM, Artes-Rodriguez E, Casimiro-Artés MÁ, Rodríguez-Pérez MA, Moreno-Martos H, et al. Absolute and relative handgrip strength as indicators of self-reported physical function and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: the EFICAN study. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:5292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baek J, Kim Y, Kim HY. Associations of handgrip asymmetry with impaired health-related quality of life among older adults in South Korea: a cross-sectional study using National survey data. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2022;34:649–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol group. Ann Med. 2001;33:337–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.EuroQol Research Foundation. EQ-5D-3L User Guide: basic information on how to use the EQ-5D-3L instrument (Version 6.0); Updated 2018. https://euroqol.org/information-and-support/documentation/user-guides/. Accessed Jan 4 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee YK, Nam HS, Chuang LH, Kim KY, Yang HK, Kwon IS, et al. South Korean time trade-off values for EQ-5D health states: modeling with observed values for 101 health states. Value Health. 2009;12:1187–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, Auyeung TW, Chou MY, Iijima K, et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus Update on Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:300-07. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGrath R, Cawthon PM, Cesari M, Al Snih S, Clark BC. Handgrip strength asymmetry and weakness are associated with lower cognitive function: a panel study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:2051–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen X, Liu G, Li S, Lin X, Han Z, Hu X, et al. Handgrip measurement method affects asymmetry but not weakness identification in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2023;24:284-91.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meng F, Zhang Y, Liu C, Zhou C. Quantitative relationship between grip strength and quality of life in the older adult based on a restricted cubic spline model. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1417660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim J, Lee I, Song M, Kang H. Relative handgrip strength mediates the relationship between hemoglobin and health-related quality of life in older Korean adults. Healthcare. 2022. 10.3390/healthcare10112215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim J, Kang S, Kim D, Kang H. Associations of physical activity and handgrip strength with health-related quality of life in older Korean cancer survivors. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:6067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie H, Lu S. The association between physical performance and subjective wellbeing in Chinese older adults: cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2022;10: 965460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li D, Guo G, Xia L, Yang X, Zhang B, Liu F, et al. Relative handgrip strength is inversely associated with metabolic profile and metabolic disease in the general population in China. Front Physiol. 2018;9:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee WJ, Peng LN, Chiou ST, Chen LK. Relative handgrip strength is a simple indicator of cardiometabolic risk among middle-aged and older people: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0160876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeong W, Moon JY, Kim JH. Association of absolute and relative hand grip strength with all-cause mortality among middle-aged and old-aged people. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23:321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Batsis JA, Zbehlik AJ, Pidgeon D, Bartels SJ. Dynapenic obesity and the effect on long-term physical function and quality of life: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mori H, Kuroda A, Yoshida S, Yasuda T, Umayahara Y, Shimizu S, et al. High prevalence and clinical impact of dynapenia and sarcopenia in Japanese patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: findings from the impact of diabetes mellitus on dynapenia study. J Diabetes Investig. 2021;12:1050–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwamura M, Kanauchi M. A cross-sectional study of the association between dynapenia and higher-level functional capacity in daily living in community-dwelling older adults in Japan. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song Q, Shu X, Li Y, Zhao Y, Yue J. Association of handgrip strength asymmetry and weakness with functional disability among middle-aged and older adults in China. J Glob Health. 2024;14:04047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi JY, Lee S, Min JY, Min KB. Asymmetrical handgrip strength is associated with lower cognitive performance in the elderly. J Clin Med. 2022;11:2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGrath R, Lang JJ, Clark BC, Cawthon PM, Black K, Kieser J, et al. Prevalence and trends of handgrip strength asymmetry in the united States. Adv Geriatr Med Res. 2023;5: e230006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sayer AA, Syddall HE, Martin HJ, Dennison EM, Roberts HC, Cooper C. Is grip strength associated with health-related quality of life? Findings from the Hertfordshire cohort study. Age Ageing. 2006;35:409–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Collins BC, Laakkonen EK, Lowe DA. Aging of the musculoskeletal system: how the loss of estrogen impacts muscle strength. Bone. 2019;123:137–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maltais ML, Desroches J, Dionne IJ. Changes in muscle mass and strength after menopause. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2009;9:186–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim J, Kim Y, Oh JW, Lee S. Sex differences of the association between handgrip strength and health-related quality of life among patients with cancer. Sci Rep. 2024;14:9876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen MJ, Ko PS, Lee MC, Su SL. Yu. Gender difference in appendicular muscle strength: determinant of the quality of life in the older Taiwanese. Aging. 2022;14:7517–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahn SK, Seo HJ, Choi MJ. Trends and regional distribution in health-related quality of life across sex and employment status: a repeated population-based cross-sectional study. J Occup Health. 2024;66: uiae017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the KNHANES website: https://knhanes.kdca.go.kr/knhanes/main.do.