Abstract

The SRY-Box Transcription Factor 9 (SOX9) is a crucial transcription factor that controls the growth, differentiation, and stemness of progenitor cells. According to research, SOX9 protein controls the initiation and progression of tumors by directly participating in tumor initiation, proliferation, migration, and chemotherapy resistance. Although SOX9 overexpression is frequently found in breast cancer, the precise molecular mechanism is yet unknown. This article reviews the structure, function, and new developments of SOX9 in the pathogenesis and treatment of breast cancer, and proposes that targeting SOX9 may improve the therapeutic effect of breast cancer and provide a reference for clinical work.

Keywords: Breast cancer, SOX9, Occurrence, Development, Treatment

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC), as one of the malignant tumors that endanger women's health in the world, has surpassed lung cancer in its incidence and ranked first in the global incidence of malignant tumors in 2020, and the mortality is increasing year by year. There are a variety of classification methods for BC, and at present, the following molecular typing is mostly used: according to estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), and Ki-67, etc., can be divided into: ① luminal type A: ER/PR-positive, and PR expression is high (≥20%), HER2-negative, Ki-67 expression is low (<14%); ② luminal type B: including HER2-negative (ER-positive, HER2-negative, and at least one of the following: Ki-67 high expression (≥ 14%), PR-negative or low expression (< 20%)), HER2-positive (ER-positive, HER2 overexpression, Ki-67 in any state, PR in any state); ③ HER2 overexpression type: HER2 overexpression or proliferation, ER and PR-negative; ④ basal-like type: triple-negative, ER, PR, HER2 are all negative.

The main methods of BC treatment include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and traditional Chinese medicine treatment [1]. Although great progress has been made in the early detection and treatment of BC in recent years, problems such as drug resistance and metastasis also greatly affect the quality of life of BC patients.

In the early 1990s of the twentieth century, a transcription factor with a unique DNA-binding domain was discovered, and because the gene encoding this transcription factor is located on the Y-chromosome, it is called a sex-determining region of Y-chromosome (SRY). Based on their sequence and function, 20 SOX genes containing HMG domains were identified in the mouse and human genomes. Eight subgroups of the genes—SOX A through H—each with 1–3 members—make up the genes. The E subgroup includes SOX9, SOX8, and SOX10 as members. Three helixes make up the SRY-associated HMG domain in SOX9 (Fig. 1) [2]. This gene produces a protein that recognizes the sequence CCTTGAG along with other members of the HMG-box class DNA-binding proteins.

Fig. 1.

Structural and functional domains of the SOX9

The protein encoded by the SOX9 gene performs a crucial part in the differentiation of chondrocytes and the formation of bone, and when defective, it can affect the development of bone and reproductive system, often with sex reversal. In addition to cartilage formation, SOX9 is a regulator of epithelial stem/progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation, and it is implicated in lung epithelial branching morphogenesis by balancing proliferation and differentiation and controlling the extracellular matrix. SOX9 regulates many developmental processes associated with stemness, differentiation, and progenitor cell development, and can also regulate tumor occurrence and development by participating in tumor initiation, proliferation, migration, and chemotherapy resistance [3, 4]. Studies have found that in cell lines of bladder cancer [5], colorectal cancer [6], lung cancer [7], pancreatic cancer [8], and other tumors, SOX9 expression is upregulated and is closely related to prognosis, speculating that this gene may be an important tumor-related gene. In this review, we explore the function of SOX9 in tumor initiation and proliferation, immune regulation, tumor microenvironment regulation, and angiogenesis regulation, predict the role of SOX9 in BC treatment and prognosis, and explore the potential of SOX9 as a target for the treatment of BC.

The role of SOX9 in the occurrence and progression of BC

Some studies have shown that SOX9 regulates several important steps in the process of BC tumorigenesis, including tumor initiation and proliferation, immune regulation, tumor microenvironment, and angiogenesis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The role of SOX9 in the occurrence and development of BC

Tumor initiation and proliferation

SOX protein has different functions and can play a carcinogenic or cancer-inhibiting role in tumorigenesis and progression. The function of SOX9 in regulating tumorigenesis is mainly related to cell cycle and cell proliferation. In the study of Olubunmi A et al. [9], SOX9 was shown to be involved in the G0/G1 blockage of T47D BC cell lines. The antiproliferative effect of tretinoin in human BC cell MCF-7 cell lines depends on the expression of transcription inhibitor HES-1, and Patrick M et al. [10] found that tretinoin can induce HES-1 expression by upregulating the transcription factor SOX9, which supports the tumor suppressor effect of SOX9. In contrast, another study showed [11] that overexpression of the SOX protein family can mediate oncogenic transformation in BC by regulating transforming growth factor β and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways and promoting tumor cell proliferation and survival. Thomsen MK et al. [12] found that SOX9 is one of the most significant elevated genes during the initial stages of tumor development. John R et al. [13] confirmed that SOX9 as an ER-negative luminal stem/progenitor cell determinant is a driver of basal-like BC, and they also observed that SOX9 plays an important role in the progression of benign breast lesions to aggressive basal-like BC. In addition, SOX9 and long non-coding RNA linc02095 create positive feedback that encourages cell growth and tumor progression by regulating each other's expression in BC cells [14]. Zheng et al. [15] demonstrated that breast cancer-associated gene 2 specifically promotes lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced BCSCs through LPS-induced SOX 9 expression, thereby regulating the occurrence, treatment resistance, and metastasis of triple-negative breast cancer. A significant genetic target downstream of protein kinase B (AKT), SOX10 is a biomarker for the triple-negative BC subtype and encourages AKT-dependent tumor growth [16]. Khalid N et al. [17] discovered that SOX9 is an AKT substrate at the serine 181 consensus site, and the −6904/−5995 region of the SOX10 promoter is an AKT response element that needs SOX9 to be active during transcription. This suggests that SOX9 can accelerate AKT-dependent tumor growth by regulating SOX10.

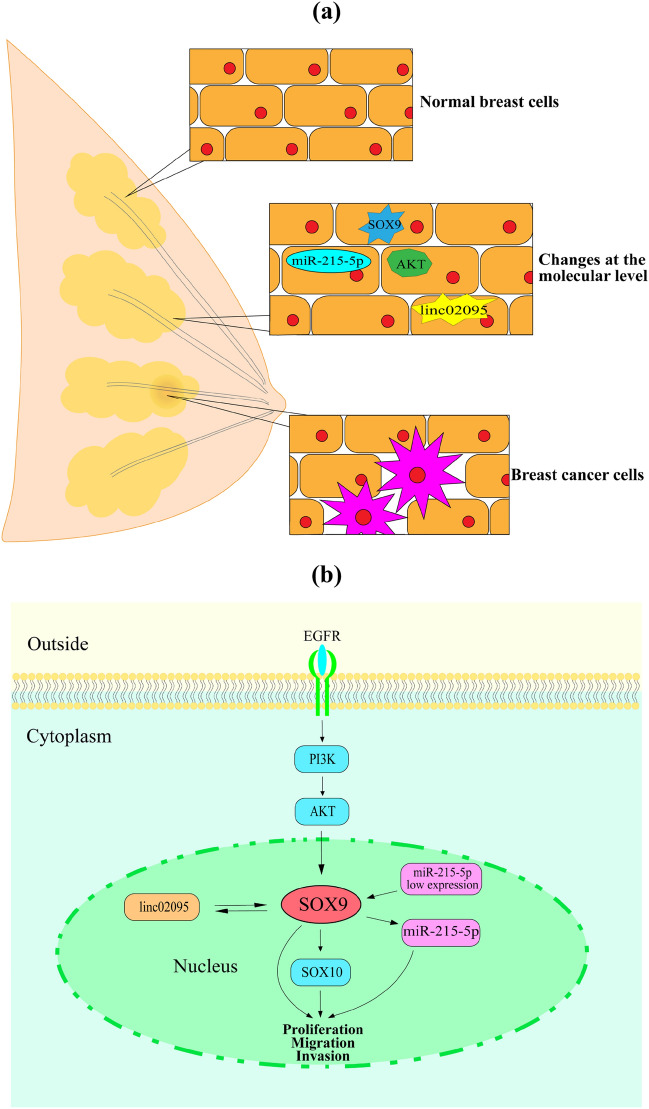

According to Ander M et al. [18], SOX9 directly interacts with and activates the polycomb group protein Bmi1 promoter, whose overexpression suppresses the activity of the tumor suppressor InK4a/Arf sites. Previous studies [19] have shown that breast epithelial stem cells are supported by SOX9, which works in concert with Slug (SNAI2) to encourage BC cell proliferation and metastasis. Marion Lapierre et al. [20] demonstrated that histone deacetylase 9 (HDAC9) no longer increases cell proliferation when SOX9 gene expression is knocked down, which indicates that by controlling mitosis in BC cells, SOX9 gene may be employed as a new HDAC9 target gene, explaining how HDAC9 affects cell proliferation. The upregulation of miR-215-5p inhibits the proliferation, migration, and invasion of BC cells. SOX9 is a potential target of miR-215-5p in BC, and overexpression of SOX9 can transform miR-215-5p into inhibitory properties related to BC cell growth and metastasis [21]. In conclusion, most studies have shown that the expression of SOX9 can increase tumor growth and progression through multiple pathways, and its inactivation can reduce tumor occurrence (Fig. 3). SOX9 has the potential to regulate cell proliferation and is expected to become a key molecular target to inhibit BC cell proliferation.

Fig. 3.

a Breast-related molecules in breast tissue and growth and proliferation of breast cancer cells. b SOX9 regulates the proliferation, migration, and invasion of breast cancer cells through a variety of pathways, including PI3K/AKT, linc02095, and miR-215-5p

Immunomodulation

According to recent research [22], immune cells can influence the formation and progression of cancer by preventing immunological rejection and promoting tumor proliferation and metastasis. In 2016, Malladi et al. [23] first described that SOX9 plays a crucial part in immune evasion. They observed that latent cancer cells had high levels of SOX2 and SOX9 expression. By sustaining stemness, these proteins can preserve latent cancer's long-term survival and tumor-initiating capabilities. Furthermore, they discovered that SOX2 and SOX9 are crucial for latent cancer cells to remain dormant in secondary metastatic sites and avoid immune monitoring under immunotolerant circumstances. In addition, PGE2 plays a role in immunomodulation and tissue regeneration by activating the SOX9 expression of endogenous renal progenitor cells [24]. These imply that SOX9 is essential for immunomodulation.

Tumor microenvironment regulation

The tumor microenvironment includes proliferating tumor cells and various matrices present in tumors, including fibroblasts, immune cells, endothelial cells, infiltrative inflammatory cells, lipocytes, as well as signaling molecules and extracellular matrix components. To explore the interactions between cell types in the tumor microenvironment, Wu et al. [25] performed cell–cell interaction analysis, revealing significant interactions between cancer cells and fibroblasts, macrophages, and endothelial cells. The tumor-induced tumor microenvironment's cellular and structural interactions influence cancer cell metastasis [26]. In addition, in the tumor microenvironment, the communication of cancer cells with stromal cells and extracellular stroma encourages heterogeneity of cancer cells, increasing multiple drug resistance, which promotes cancer cell proliferation and metastasis [27]. Breast cancer cells' interaction with the surrounding matrix causes BC to be tumorigenic, and phenotypic and genetic changes in the cells that make up the tumor microenvironment play a role in tumor initiation, development, metastasis, and therapy resistance [28]. Mao et al. [29] demonstrated that tumor-associated macrophages, cancer-associated fibroblasts, endothelial cells, tumor-associated lipids, and leukocytes are key components of tumor stroma that can dismantle the tumor microenvironment and take part in the induction of breast malignant tumors through many mechanisms such as secretion of cytokines and overexpression of collagen VI. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) can promote the growth of precancerous and cancerous CAF breast epithelial cells by increasing estradiol levels. Tumor-associated macrophage secretes growth factors that promote angiogenesis, growth, invasion, migration, metastatic diffusion, and immunosuppression. Adipose-derived stem cell promotes the growth and survival of breast cancer cells by secreting cytokines (IL-6, IL 8, CCL-5, and CXCL 12/SDF-1) (Fig. 4). Pre-adipocytes are shown to promote cell-to-cell contact in BC through produced exosomes, which in turn play a role in the development and metastasis of breast cancers, according to Ramkishore G’s research [30]. The study also elucidated the role of miR-140/SOX2/SOX9 axis in regulating differentiation, stemness, and migration in the tumor microenvironment, revealing the significance of preadipocyte-derived exosomes miR-140 in regulating early BC cell migration and tumor formation. In addition, studies [3] have proposed that SOX9 is the primary regulator of these procedures in the tumor microenvironment, mediating carcinogenesis in vivo. Elevated SOX9 may be regulated by cytokines secreted by CAF and may mediate the protumor effects of CAF.

Fig. 4.

Key components of the breast tumor microenvironment

Angiogenesis regulation

The development and metastasis of the majority of malignancies, including BC, are greatly influenced by tumor angiogenesis. In the realm of cancer research, the connection between angiogenesis and tumor development has recently gained attention. SOX9 may play a wider role in the circulatory system to promote cancer start and progression in addition to its roles in sex and cartilage development [31]. The most significant of several endothelial factors, vascular endothelial cadherin is linked to angiogenesis and is a crucial adhesion factor in the angiogenic process [32]. The expression of several endothelial genes, including vascular endothelial cadherin, is induced by tretinoin, a key regulator of embryogenesis, cancer, and other disorders. Endo Y [33] discovered that SOX9 and ER81 in the E26 transformation-specific (Ets) family bind to the promoter of the vascular endothelial cadherin gene and participate in the transcriptional induction of tretinoin, and the SOX9-ER81 transcription complex induces the expression of vascular endothelial cadherin, which can lead to morphological changes, which may lead to angiogenesis during tretinoin treatment. Because triple-negative BC has a greater angiogenic potential, patients often develop metastases early [34]. Liang et al. [35] discovered that miRNA-206 is related to the invasion and angiogenesis of triple-negative BC and that its anticipated targets include vascular endothelial growth factor, SOX9, and MAPK3. In general, vascular endothelial cadherin is closely related to angiogenesis, but whether SOX9 can promote angiogenesis remains to be further explored.

SOX9 and BC treatment

Breast self-examination and clinical breast examination can help detect breast cancer early, contribute to more effective treatments, and reduce breast cancer-related mortality [36, 37]. About 60~70% of BCs are positive for hormone receptors (HR), which constitute the main subtype of BC. Endocrine therapy is often the major form of treatment for BC that is HR-positive. Antiestrogen therapy does not always work for individuals with HR-positive BC, and many acquire resistance [38]. Drug resistance in the treatment of BC may be significantly impacted by SOX9.

Xue et al. [39] found that HDAC5 plays a role in the deacetylation of SOX9, which in turn mediates SOX9’s nuclear localization in tamoxifen-resistant BC cells, which promotes the resistance of tamoxifen in BC, indicating that SOX9 plays a crucial role in regulating tamoxifen resistance. Jeselsohn R et al. [40] revealed that upregulation of Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) was observed in tamoxifen-resistant BC cells, and tamoxifen resistance was caused by a collection of genes transcribed by the RUNX2-ER complex, with SOX9 being the main transcribed gene among them. Another study showed [41] that SOX9 expression levels were higher in pathological samples from BC patients and were significantly higher in ER-negative tissue samples than in ER-positive tissues. Downregulating SOX9 also inhibited the growth of tamoxifen-resistant BC cells in vivo. In addition, SOX9 is a major regulator of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which heightens BC cell resistance to estrogen treatment [42]. These studies have focused on tamoxifen resistance. However, there is growing evidence that BC patients are plagued by multidrug resistance and exploration of the molecular processes is still ongoing. In conclusion, SOX9 plays a role in the BC endocrine therapy drug resistance process and is anticipated to be a target for the treatment of BC endocrine resistance.

Due to its pleiotropic role in the process of cancer, many tumors now have SOX9 as a valuable therapeutic target. Previous studies [43] have shown that in vitro hepatocellular carcinoma, increasing miR-1-3p expression by targeting SOX9 inhibits cell proliferation and tumor volume. In non-small cell lung cancer, evodiamine can inhibit cell growth and invasion and induce apoptosis by targeting SOX9 and the multifunctional protein β-catenin [44]. Yu et al. [45] demonstrated that miR-190 can enhance the antiestrogen sensitivity of BC cells in vivo and in vitro, and miRNA-190 regulates SOX9 expression in BC, which can increase BC cells’ sensitivity to endocrine therapy by inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Additionally, their findings suggested a role for the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in antiestrogen therapy in BC and the ZEB1/ER–miR-190–SOX9 axis. Overall, SOX9 is involved in the treatment of breast cancer endocrine resistance through multiple pathways (Fig. 5). In addition, Kyle C et al. [46] showed that active intestinal stem cells (ISCs) were transformed into reserve ISC status by upregulating SOX9 and that reserve ISCs play a key role in epithelial regeneration and repair after events that deplete actively proliferating stem cells, including ionizing radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Most studies believe that [2, 47] SOX9 expression is concerned with the poor prognosis of metastatic advanced tumors and patients with chemotherapy resistance, which gives SOX9 a solid theoretical foundation for its potential as a molecular target for cancer treatment.

Fig. 5.

SOX9 is involved in breast cancer endocrine therapy resistance through multiple pathways, including Wnt/β-catenin, RUNX2/Erα, and c-Myc/HDAC5

SOX9 indicates the prognosis of BC

Abnormal SOX9 expression regulates the occurrence and progression of a variety of cancers, so studying SOX9 expression in tumors may have prognostic value for clinical results in patients with particular cancer kinds. Several studies have found that higher SOX9 levels have been linked to worse outcomes in patients with prostate cancer [48], melanoma [49], colorectal cancer, BC, and glioma [50], while low SOX9 expression has been linked to worse outcomes in people with gastric cancer [51]. In pancreatic cancer, SOX9 confers cell plasticity and encourages the change of pancreatic cancer cells from epithelial to mesenchymal, which increases the risk of pancreatic cancer metastasis and its resistance to chemotherapy, indicating that SOX9 is strongly associated with the prognosis of pancreatic cancer [52]. A study [53] has found that the expression of ecological viral integration site−1 and SOX9 is related to stemness and metastasis, and their deletion can weaken the metastasis latent of BC cells, and overexpression can enhance the metastatic potential of BC cells. Another immunohistochemistry investigation found that SOX9 was a characteristic gene of aggressive basal-like BC, and its expression linked with histologic grade may be an independent indicator of a poor prognosis in triple-negative BC patients [54]. At the same time, Cosima R et al. [19] discovered the increased expression of SOX9 in the stroma following chemotherapy was linked to shorter overall survival. They also hypothesized that the expression of SOX9 was closely associated with the expression of ER, PR, Ki-67, and p53. In addition, HDAC5 and SOX9 are associated with low survival of ER-positive BC treated with endocrine therapy [39]. According to Richtig G et al. [55], SOX9 expression may be a powerful predictor of subpar 5-year recurrence-free survival. They also noted that stemness induction and drug resistance could lead to treatment failure in BC with high SOX9 expression. High expression of SOX9 may be related to shortened overall survival and disease-free survival in BC patients, suggesting poor prognosis in BC patients.

Conclusion

With the introduction of the new concept that "the best treatment for BC patients is personalized treatment", it is important to explore more biomarkers, classify patients into specific subtypes for treatment, and use effective markers to predict treatment outcomes [56]. Future cancer treatments may be significantly impacted by the interaction between stromal cells and cancer cells in the tumor microenvironment, which may aid in the screening of prospective biomarkers. During the growth of BC, SOX9 controls cell proliferation, migration, immune evasion, and treatment resistance. Consequently, it may be a key target for the development of BC therapeutics. We need to conduct more research to further elucidate the specific mechanism of SOX9 in the formation of BC development, development, and treatment, provide ideas for the design of SOX9-targeted drugs, and make efforts to increase BC patients' overall survival and survival without illness.

Author contributions

Yaru Wang prepared Figs. 1, 2 and 4. Luyao Huang and Mingping Qian prepared Figs. 3 and 5. Yaru Wang and Juhang Chu wrote the main manuscript text.

Funding

This work was supported by the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission Research Project [grant number 2020HP11] and Shanghai Hospital Development Center Foundation, China [SHDC2022CRS033].

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors agree to publish the manuscript.

Competing interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Korde LA, Somerfield MR, Carey LA, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and targeted therapy for breast cancer: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(13):1485–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panda M, Tripathi SK, Biswal BK. SOX9: an emerging driving factor from cancer progression to drug resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2021;1875(2):188517. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2021.188517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qin H, Yang Y, Jiang B, et al. SOX9 in prostate cancer is upregulated by cancer-associated fibroblasts to promote tumor progression through HGF/c-Met-FRA1 signaling. FEBS J. 2021;288(18):5406–29. 10.1111/febs.15816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L, Zhang Z, Yu X, et al. SOX9/miR-203a axis drives PI3K/AKT signaling to promote esophageal cancer progression. Cancer Lett. 2020;468:14–26. 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aleman A, Adrien L, Lopez-Serra L, et al. Identification of DNA hypermethylation of SOX9 in association with bladder cancer progression using CpG microarrays. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(2):466–73. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrasco-Garcia E, Lopez L, Aldaz P, et al. SOX9-regulated cell plasticity in colorectal metastasis is attenuated by rapamycin. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):32350. 10.1038/srep32350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou CH, Ye LP, Ye SX, et al. Clinical significance of SOX9 in human non-small cell lung cancer progression and overall patient survival. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2012;31(1):18. 10.1186/1756-9966-31-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edelman HE, McClymont SA, Tucker TR, et al. SOX9 modulates cancer biomarker and cilia genes in pancreatic cancer. Human Mol Gen. 2021;30(6):485–99. 10.1093/hmg/ddab064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Afonja O, Raaka BM, Huang A, et al. RAR agonists stimulate SOX9 gene expression in breast cancer cell lines: evidence for a role in retinoid-mediated growth inhibition. Oncogene. 2002;21(51):7850–60. 10.1038/sj.onc.1205985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Müller P, Crofts JD, Newman BS, et al. SOX9 mediates the retinoic acid-induced HES-1 gene expression in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;120(2):317–26. 10.1007/s10549-009-0381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta GA, Khanna P, Gatza ML. Emerging role of SOX proteins in breast cancer development and maintenance. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2019;24(3):213–30. 10.1007/s10911-019-09430-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomsen MK, Ambroisine L, Wynn S, et al. SOX9 elevation in the prostate promotes proliferation and cooperates with PTEN loss to drive tumor formation. Cancer Res. 2010;70(3):979–87. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christin JR, Wang C, Chung CY, et al. Stem cell determinant SOX9 promotes lineage plasticity and progression in basal-like breast cancer. Cell Rep. 2020;31(10): 107742. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tariq A, Hao Q, Sun Q, et al. LncRNA-mediated regulation of SOX9 expression in basal subtype breast cancer cells. RNA. 2020;26(2):175–85. 10.1261/rna.073254.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng M, Liu W, Zhang R, et al. E3 ubiquitin ligase BCA2 promotes breast cancer stemness by up-regulation of SOX9 by LPS. Int J Biol Sci. 2024;20(7):2686–97. 10.7150/ijbs.92338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Zahrani KN, Abou-Hamad J, Cook DP, et al. Loss of the Ste20-like kinase induces a basal/stem-like phenotype in HER2-positive breast cancers. Oncogene. 2020;39(23):4592–602. 10.1038/s41388-020-1315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Zahrani KN, Abou-Hamad J, Pascoal J, Labrèche C, Garland B, Sabourin LA. AKT-mediated phosphorylation of Sox9 induces Sox10 transcription in a murine model of HER2-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2021;23(1):55. 10.1186/s13058-021-01435-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matheu A, Collado M, Wise C, et al. Oncogenicity of the developmental transcription factor Sox9. Cancer Res. 2012;72(5):1301–15. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riemenschnitter C, Teleki I, Tischler V, Guo W, Varga Z. Stability and prognostic value of Slug, Sox9 and Sox10 expression in breast cancers treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Published online 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Lapierre M, Linares A, Dalvai M, et al. Histone deacetylase 9 regulates breast cancer cell proliferation and the response to histone deacetylase inhibitors. Oncotarget. 2016;7(15):19693–708. 10.18632/oncotarget.7564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao JB, Zhu MN, Zhu XL. miRNA-215-5p suppresses the aggressiveness of breast cancer cells by targeting Sox9. FEBS Open Bio. 2019;9(11):1957–67. 10.1002/2211-5463.12733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mittal D, Gubin MM, Schreiber RD, Smyth MJ. New insights into cancer immunoediting and its three component phases—elimination, equilibrium and escape. Curr Opin Immunol. 2014;27:16–25. 10.1016/j.coi.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malladi S, Macalinao DG, Jin X, et al. Metastatic latency and immune evasion through autocrine inhibition of WNT. Cell. 2016;165(1):45–60. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen S, Huang H, Liu Y, et al. Renal subcapsular delivery of PGE2 promotes kidney repair by activating endogenous Sox9+ stem cells. iScience. 2021;24(11):103243. 10.1016/j.isci.2021.103243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu F, Fan J, He Y, et al. Single-cell profiling of tumor heterogeneity and the microenvironment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):2540. 10.1038/s41467-021-22801-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neophytou CM, Panagi M, Stylianopoulos T, Papageorgis P. The role of tumor microenvironment in cancer metastasis: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Cancers. 2021;13(9):2053. 10.3390/cancers13092053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baghban R, Roshangar L, Jahanban-Esfahlan R, et al. Tumor microenvironment complexity and therapeutic implications at a glance. Cell Commun Signal. 2020;18(1):59. 10.1186/s12964-020-0530-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehraj U, Dar AH, Wani NA, Mir MA. Tumor microenvironment promotes breast cancer chemoresistance. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2021;87(2):147–58. 10.1007/s00280-020-04222-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mao Y, Keller ET, Garfield DH, Shen K, Wang J. Stromal cells in tumor microenvironment and breast cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2013;32(1–2):303–15. 10.1007/s10555-012-9415-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gernapudi R, Yao Y, Zhang Y, et al. Targeting exosomes from preadipocytes inhibits preadipocyte to cancer stem cell signaling in early-stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;150(3):685–95. 10.1007/s10549-015-3326-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akiyama H, Chaboissier MC, Behringer RR, et al. Essential role of Sox9 in the pathway that controls formation of cardiac valves and septa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(17):6502–7. 10.1073/pnas.0401711101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vestweber D. VE-cadherin: the major endothelial adhesion molecule controlling cellular junctions and blood vessel formation. ATVB. 2008;28(2):223–32. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.158014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Endo Y, Deonauth K, Prahalad P, Hoxter B, Zhu Y, Byers SW. Role of Sox-9, ER81 and VE-cadherin in retinoic acid-mediated trans-differentiation of breast cancer cells. Cordes N, ed. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(7):e2714. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(15):4429–34. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang Z, Bian X, Shim H. Downregulation of microRNA-206 promotes invasion and angiogenesis of triple negative breast cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;477(3):461–6. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.06.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tomic M, et al. Exploring female medical students knowledge, attitudes, practices, and perceptions related to breast cancer screening: a scoping review. JMedLife. 2023;16(12):1732–9. 10.25122/jml-2023-0412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomic M, Blaga O. Assessing personal and health system barriers to breast cancer early diagnosis practices for women over 20 years old in Cluj-Napoca, Romania. Med Pharm Rep. 2024;98(1):118–24. 10.15386/mpr-2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Acar A, Simões BM, Clarke RB, Brennan K. A role for notch signalling in breast cancer and endocrine resistance. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:1–6. 10.1155/2016/2498764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xue Y, Lian W, Zhi J, et al. HDAC5-mediated deacetylation and nuclear localisation of SOX9 is critical for tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2019;121(12):1039–49. 10.1038/s41416-019-0625-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jeselsohn R, Cornwell M, Pun M, et al. Embryonic transcription factor SOX9 drives breast cancer endocrine resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017. 10.1073/pnas.1620993114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Domenici G, Aurrekoetxea-Rodríguez I, Simões BM, et al. A Sox2–Sox9 signalling axis maintains human breast luminal progenitor and breast cancer stem cells. Oncogene. 2019;38(17):3151–69. 10.1038/s41388-018-0656-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu Y, Wang B, Feng JE. Input observability of Boolean control networks. Neurocomputing. 2019;333:22–8. 10.1016/j.neucom.2018.12.014. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tripathi SK, Sahoo RK, Biswal BK. SOX9 as an emerging target for anticancer drugs and a prognostic biomarker for cancer drug resistance. Drug Discov Today. 2022;27(9):2541–50. 10.1016/j.drudis.2022.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panda M, Biswal BK. Evodiamine inhibits stemness and metastasis by altering the SOX9–β-catenin axis in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2022;123(9):1454–66. 10.1002/jcb.30304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu Y, Yin W, Yu ZH, et al. miR-190 enhances endocrine therapy sensitivity by regulating SOX9 expression in breast cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):22. 10.1186/s13046-019-1039-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roche KC, Gracz AD, Liu XF, Newton V, Akiyama H, Magness ST. SOX9 maintains reserve stem cells and preserves radioresistance in mouse small intestine. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1553-1563.e10. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Q, Chen H, Yang C, Liu Y, Li F, Zhang C. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of SOX9 expression in gastric cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Medicine. 2022;101(37): e30533. 10.1097/MD.0000000000030533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhong W, Qin GQ, He HC, et al. Combined overexpression of HIVEP3 and SOX9 predicts unfavorable biochemical recurrence- free survival in patients with prostate cancer. OTT. 2014. 10.2147/OTT.S55432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng PF, Shakhova O, Widmer DS, et al. Methylation-dependent SOX9 expression mediates invasion in human melanoma cells and is a negative prognostic factor in advanced melanoma. Genome Biol. 2015;16(1):42. 10.1186/s13059-015-0594-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sang Q, Liu X, Sun D. Role of miR-613 as a tumor suppressor in glioma cells by targeting SOX9. OTT. 2018;11:2429–38. 10.2147/OTT.S156608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mesquita P, Freire AF, Lopes N, et al. Expression and clinical relevance of SOX9 in gastric cancer. Dis Mark. 2019;2019:1–11. 10.1155/2019/8267021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carrasco-Garcia E, Lopez L, Moncho-Amor V, et al. SOX9 triggers different epithelial to mesenchymal transition states to promote pancreatic cancer progression. Cancers. 2022;14(4):916. 10.3390/cancers14040916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mateo F, Arenas EJ, Aguilar H, et al. Stem cell-like transcriptional reprogramming mediates metastatic resistance to mTOR inhibition. Oncogene. 2017;36(19):2737–49. 10.1038/onc.2016.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang H, He L, Ma F, et al. SOX9 regulates low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (LRP6) and T-cell factor 4 (TCF4) expression and Wnt/β-catenin activation in breast cancer. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(9):6478–87. 10.1074/jbc.M112.419184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Richtig G, Aigelsreiter A, Schwarzenbacher D, et al. SOX9 is a proliferation and stem cell factor in hepatocellular carcinoma and possess widespread prognostic significance in different cancer types. Coleman WB, ed. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(11):e0187814. 10.1371/journal.pone.0187814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Li B, Liu J, Wu G, Zhu Q, Cang S. Evaluation of adjuvant therapy for T1–2N1miM0 breast cancer without further axillary lymph node dissection. Front Surg. 2023;9: 905437. 10.3389/fsurg.2022.905437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.