Abstract

The evidence that tobacco cigarettes are harmful to the health of smokers led to the introduction of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) as a safer alternative. ENDS, which include electronic cigarettes (e-cigs) and heated tobacco products (battery-operated devices that heat a liquid and produce an aerosol), are portable, cheap, easy-to-use, self-powered devices, and resemble tobacco cigarettes. After an overview of the toxicological, clinical, and epidemiological implications associated with the increasingly widespread use of ENDS, this narrative paper evaluates their role as a smoking cessation aid. Randomized controlled trials show that e-cigs can help in achieving cigarette smoking cessation, but their role in real life is still debated. There is no clear association in current smokers between the prevalence of e-cig use and overall quit rates. Although ENDS are not Food and Drug Administration (FDA)- and European Medicines Agency (EMA)-approved for quitting, they are one of the most widely utilized pharmacological support devices for smoking cessation. Physicians should ask for ENDS use and amount at each visit, be able to advise on how to manage ENDS as an aid for quitting, encourage vapers not to continue their use indefinitely, and explain how to stop ENDS.

Keywords: Harm reduction, Nicotine, HTP, Tobacco, Cigarette, Electronic cigarette, Smoking, ENDS, Vaping

Key Summary Points

| The diffusion of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) worldwide raises new possibilities and doubts about their impact on people’s health. |

| This article offers an overview of the opportunity to favor smoking cessation through ENDS use compared to traditional nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). |

| The utility of ENDS must be weighed against the still unknown possible long-term adverse effects of these new devices on patients’ health. |

| The topic is still highly debated, as can be seen from the differences in opinions between the main scientific associations regarding this issue. |

Introduction

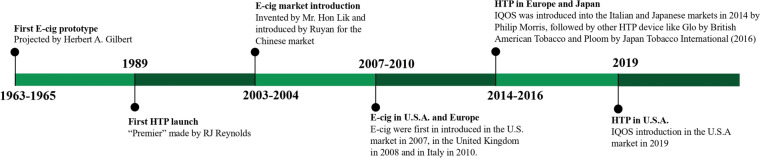

Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) include electronic cigarettes (hereinafter referred to as e-cigs) and heated tobacco products (hereinafter referred to as HTPs). A brief history of ENDS is shown in Fig. 1. Many extensive reviews for details of ENDS composition and mechanisms of action [1–5] can be found in the literature. These devices are portable, cheap, and self (battery)-powered, have a discreet and convenient design resembling tobacco cigarettes, and produce aerosols containing nicotine without any combustion. The “modern” e-cigs have better performance and easier use and maintenance than previous models, and novel generations of devices are continuously marketed. There are a range of different e-cigs that differ in shape, flavor, use, maintenance, and performance. Among the proposed classifications of e-cigs, we suggest distinguishing between disposable and rechargeable/refillable e-cigs, where either the tank is periodically replaced with ready-to-use e-liquid or the e-liquid is manually refilled with the possibility of customizing it (Table 1 and Figs. 1, 2). We will only deal with e-cigs containing nicotine; they contain an e-liquid with different nicotine concentrations. Only e-liquids with nicotine concentrations ≤ 20 mg/mL (2%) are available in the European Union (EU) [6], whereas in other countries, such as the United States, there are no restrictions on nicotine concentration. In addition to nicotine, the e-liquid usually contains water, glycerol, propylene glycol, and flavorings. HTPs are devices containing tobacco sticks. The stick is a paste containing tobacco, flavors, cellulose, guar gum, and propylene glycol. The best-selling HTP is IQOS (I Quit Ordinary Smoking) by Philip Morris International, but other products are very common. The widespread use of ENDS has several implications for clinicians. After a toxicological, clinical, and epidemiological overview, this narrative paper focuses on the role of the clinician dealing with daily ENDS users.

Fig. 1.

Timeline of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) history

Table 1.

The most commonly used e-cigs by type

| Most popular e-cigarettes brands | |

|---|---|

| Rechargeable | Disposable |

| KIWI | Vuse |

| Juul | Elfbar |

| Vaporesso | Dinner Lady |

| JustFog | GeekBar |

| Joyetech | Blubar |

| Eleaf | Lost Mary |

Fig. 2.

Main differences between e-cig devices

Why is it Important, but Difficult, to Stop Cigarette Smoking? How Can Smoking Cessation Rate Increase?

Cigarette smoking is a leading preventable cause of death, disease, and disability. Quitting at any age is associated with lower excess mortality. People who quit at ages 35–44, 45–54, and 55–64 gain approximately 9, 6, and 4 years relative to continuing to smoke, respectively [7]. Due to the evidence that cigarette smoking is harmful, many smokers want to stop smoking, but they do not always succeed in quitting. Less than 5–10% of smokers who try quitting alone achieve sustained smoking abstinence at 1 year of follow-up [8]. Smoking cessation assistance increases quitting rates, but it is seldom available, and therefore most smokers try quitting alone. An analysis of smoking cessation attempts in the EU found that almost three-quarters of smokers in 2017 (74.8%) had tried to quit alone [9]. Long-standing evidence shows that some pharmacological therapies properly provided to smokers motivated to quit are effective and safe for quitting and, in combination with behavioral support, achieve sustained abstinence rates of 30% at 1-year follow-up. Currently approved pharmacotherapies to support smokers in quitting include nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), such as nicotine patches, gum, and inhalers, the α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonists varenicline and cytisine, and the dopamine and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor bupropion, alone or in combination [10]. The uptake of nicotine, the main psychoactive component of tobacco, from cigarette smoking is the main cause of difficulties in quitting. Nicotine stimulates the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors of the body, primarily in the central and peripheral nervous system. Notably, not only is the substance a key determinant for most positive psychotropic effects of nicotine, but the speed of absorption is a key factor as well. Smoke from cigars or pipes has an alkaline pH (about > 6.5) and permits a moderate and relatively slow absorption of nicotine through the mucosal mouth. Smoke from tobacco cigarettes produces an acidic environment (i.e., pH 5.5–6.0), permitting a faster and larger absorption of nicotine through the lungs, with peaks in plasma and brain within a few tens of seconds after inhalation, as shown in Figs. 3 and 4. After inhalation, nicotine is rapidly metabolized, prompting the smoker to inhale again to obtain further positive psychotropic effects. In addition, the continuous use of nicotine by tobacco cigarette smokers desensitizes the receptors, leading to the development of tolerance and dependence. By regular smoking throughout the day, the dependent cigarette smoker guarantees stable concentrations of nicotine in the brain, and any voluntary or involuntary cessation of smoking provokes withdrawal symptoms, such as agitation, anxiety, insomnia, difficulty concentrating, tiredness, irritability, and increased appetite [11]. The need for cigarette smoking is not only physical, but also psychological. This is closely related to the gestures, cues, and routine act of smoking. Every action in the day becomes associated with the gratification of nicotine intake through a mechanism that, in addition to the peak of nicotine at the brain level, evokes an element linked to a reassuring, primordial regressive symbolism tied to the hand-to-mouth ritual.

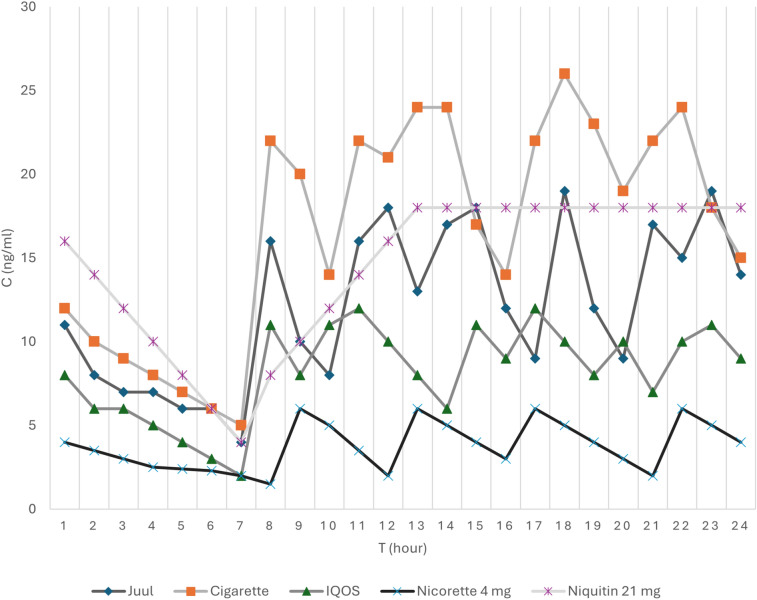

Fig. 3.

Pharmacokinetic comparison of nicotine plasma levels over a 24-h period between tobacco cigarettes, some electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) [104–107]. It can be seen how the nicotine plasma levels rise and fall during a normal day of a daily user of e-cigs, HTPs (heated tobacco products), cigarettes, or NRT. Every spike corresponds to smoking a cigarette, an IQOS (HTP), or a JUUL (e-cig), or using an NRT (patches like Nicorette/Niquitin). The graph shows how NRT has a constant and regular standard level which can be controlled depending on the dose of the NRT. On the other end, cigarettes have the highest spike of dose, followed by e-cigs, and lastly by HTPs

Fig. 4.

Current daily users of e-cigs and heated tobacco products (HTPs) worldwide [103, 108–113]

Recently marketed e-cigs contain nicotine salt formulations that have a smoother taste in the mouth and are less irritating than their free-base variety, improving the sensory experience of vaping and optimizing nicotine absorption, with pharmacokinetics resembling that of tobacco cigarettes. Similar findings are observed with recent HTPs [12–16]. Of course, the bioavailability of nicotine depends not only on the device, but also on the technique and the experience of the user. Comparative studies show similar degrees of nicotine dependence between users of some novel ENDS and traditional cigarettes [17–19]. We have displayed the kinetics of blood nicotine after smoking tobacco cigarettes, e-cigs, and HTPs, and the use of some NRT in Fig. 4. NRT products, when properly used, ensure relatively constant levels of nicotine in the blood and brain over 24 h, controlling withdrawal symptoms, but do not sustain rewarding effects associated with nicotine peaks obtainable by smoking tobacco cigarettes.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Clinical Consequences of Inhalation from ENDS

Combustion, absent with the use of ENDS [17], is responsible for most of the toxic substances inhaled with cigarette smoking. Many studies (mostly those sponsored by manufacturers of ENDS) show that the concentration of traditional toxicants inhaled with ENDS is lower—often much lower—than the concentration that results from inhaling cigarettes [20]. However, the health risks are not linearly related to exposure to inhaled toxicants. In addition, other toxicants, such as valeraldehyde, acrolein, and acenaphthene, are found in aerosols from ENDS at similar or even higher concentrations than those observed when smoking tobacco cigarettes [1–5, 21–23]. There are many case reports of acute lung damage associated with the use of e-cigs [24]. E-cig- or vaping-associated lung injury (EVALI), the epidemic occurring in the USA, mostly in young people, with serious and even fatal acute lung damage associated with vaping, has caused great concern [25]. Although most cases have been attributed to unorthodox vaping of tetrahydrocannabinol with vitamin E acetate [25], EVALI confirms the harmful risks inherent to possible manipulation of e-liquids, common among young people [26]. Moreover, the use of e-cigs may increase the frequency of exacerbations or wheezing and worsen respiratory function in individuals with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [24, 27–29]. On the other hand, other studies reported that the switch from cigarette smokers to e-cigs only may reduce the frequency of exacerbations and attenuate respiratory symptoms compared to those who continued to smoke [30].

Less information is available on the health risks related to the use of HTPs. The Japan Society and New Tobacco Internet Survey (JASTIS) cross-sectional study found adverse respiratory effects in HTP users; in addition, among patients with cancer scheduled for surgery, the occurrence of airway obstruction in current exclusive HTP users was greater than in never-tobacco users [31]. Another small study comparing 19 COPD patients switching to HTPs versus a matched control group who continued to smoke did not find any significant difference in COPD Assessment Test (CAT) score, exercise capacity, or exacerbation rate at 3-year follow-up [32]. The use of ENDS has been associated with oxidative stress and endothelial damage, and nicotine itself has a known stimulant effect on heart rate and blood pressure. However, the cardiovascular effects of ENDS might be of less clinical relevance than tobacco cigarettes [33]. In a nationwide Korean study, switching to e-cigs in patients following percutaneous coronary intervention was associated with a lower rate of major adverse cardiovascular events than continuing smoking [34]. Another nationwide Korean study found that, compared with cigarette-only smokers, individuals who quit tobacco cigarettes and switched to ENDS only use had a lower risk for subsequent cardiovascular disease (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.81, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78–0.84). However, recent cigarette quitters with ENDS use had a higher risk for cardiovascular events than recent cigarette quitters without ENDS use (aHR 1.31; 95% CI 1.01–1.70). In addition, compared with long-term cigarette quitters without ENDS use, long-term quitters with ENDS use had higher cardiovascular risk (aHR 1.70; 95% CI 1.07–2.72 [35]).

A last key question is related to the risk of health harms for proxies of ENDS users. Cases of worsening of asthma and/or other lung diseases have been reported in individuals passively exposed to e-cigs [24, 36, 37]. Switching from smoking to vaping indoors may substantially reduce, but not eliminate, second-hand exposure to nicotine and other noxious substances [38]. There is less dispersion of toxicants from the mainstream and a shorter half-life of the particulate exhaled by ENDS users than that emitted by cigarette smokers [39].

Epidemiological use of ENDS

The diffusion of ENDS is now worldwide, albeit with differences between geographical areas (see Figs. 4, 5), related to both commercial factors (different promotion of manufacturers) and local laws. HTPs are mostly popular in Japan, where the sale of nicotine e-cigs is heavily restricted [40]. HTP use remains occasional in the UK and Northern Europe. The use of e-cigs prevails in the UK, where around 9% of the adult population use them, with just over half using them daily [41]. In the cross-sectional Smoking Toolkit Study [42], 85% of individuals who reported using e-cigs in their attempt to stop smoking cigarettes and quitting successfully became long-term vapers. However, in recent years in England, an increase in long-term vaping has been observed not only in former smokers, but even in individuals who continued to smoke tobacco cigarettes (dual smokers) [41]. Some studies have shown that simultaneous use of cigarettes and ENDS could have worse health consequences than the use of tobacco cigarettes only [24, 43]. The fate of former cigarette smokers who started ENDS afterwards is unclear. One study shows that at 1-year follow-up, many long-term vapers relapse to cigarette smoking (44%) [44]. From 2021 in England, the rate of vapers also increased considerably in never-smokers, mainly driven by young adults [45] using disposable e-cigs (50%). Many authors think that e-cig use may act as a gateway to subsequent traditional cigarette smoking. The Global Youth Tobacco Survey recently found rates of dual smokers up to 10% of Italian and Latvian 13–15-year-olds [46]. The use of novel e-cigs with the potential to induce dependence is particularly worrying in never-smoker adolescents, for whom disposable e-cigs are banned in the UK beginning in summer 2025. In 2018, 90.5% of HTP users in Canada, the USA, England, and Australia were dual smokers [47]. E-cig users are also increasing (> 50% in most countries of the study from the Global Youth Tobacco Survey) and seem to be more prone to starting after conventional cigarette smoking than never-users, becoming “dual smokers” [48]. Some studies found that HTP use in former smokers was associated with a higher risk of relapse than no-HTP use [49, 50].

Fig. 5.

Current daily users of e-cigs and HTPs worldwide [103, 108–113]

Role of ENDS as a Smoking Cessation Aid

Manufacturers have proposed ENDS as cigarette smoking cessation aids. Unlike in the UK, where e-cigs have been endorsed by the Royal College of Physicians as an acceptable smoking cessation aid [51], ENDS are not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or European Medicines Agency (EMA) to aid motivated smokers in quitting. Based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs), a Cochrane analysis showed that the use of e-cigs increased rates of smoking cessation versus no pharmacological treatment (odds ratio [OR] 2.37, 95% CI 1.73–3.24; 16 RCTs, 3828 participants [52]). A few large studies have compared different pharmacological treatments as help for smoking cessation. An RCT study in 458 individuals motivated to quit found biochemically confirmed abstinence at 26 weeks in 61 of 152 participants (40.4%) in the e-cig group versus 67 of 153 (43.8%) in the varenicline group and 30 of 153 (19.7%) in the placebo group (P < 0.001); no serious adverse events were reported [53]. Another study suggested that the combination of varenicline and e-cigs increased quitting rates versus the varenicline-only arm [54]. A large RCT including 886 participants found a 1-year abstinence rate of 18% in the e-cig group versus 10% in the NRT arm (relative risk [RR] 1.83; 95% CI 1.30–2.58; P < 0.001). At the end of the study, many e-cig users who quit continued to vape (80% vs. 9% for the NRT arm, [55]). A Cochrane review showed a clear advantage for quitting in individuals using e-cigs (OR 2.37, 95% CI 1.73–3.24), varenicline (OR 2.33, 95% CI 2.02–2.68), cytisine (OR 2.21, 95% CI 1.66–2.97), or a combination of NRT (OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.61–2.34) and, to a lesser degree, nicotine patch (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.20–1.56), other NRT alone (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.29–1.55), and bupropion (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.26–1.62). There is evidence that e-cigs increase quit rates compared to a single NRT (RR 1.59, 95% CI 1.30–1.93; seven studies, 2544 participants) and moderate-certainty evidence that they increase quit rates compared to e-cigs without nicotine (RR 1.46, 95% CI 1.09–1.96; six studies, 1613 participants) [10].

The ultimate role of e-cigs as a smoking cessation aid in real life remains debated. Some studies showed an advantage for e-cigs [52, 56], while others did not [57–59], either in adult smokers in general (OR 0.95; 95% CI 0.77–1.16) or in the subgroup motivated to quit (OR 0.85; 95% CI 0.68–1.06). It is possible that differences in the methods and populations between studies were too great to draw firm conclusions. Current cigarette smokers usually start using ENDS as a smoking cessation aid, but also to guarantee nicotine intake (and avoid withdrawal symptoms) in settings where cigarette smoking is forbidden, or simply enjoy being dual users. It is also unclear whether ENDS use can bolster motivation to quit cigarette smoking. A recent naturalistic RCT [60] evaluated the effect of offering free e-cigs to smokers not motivated to stop smoking cigarettes. At a 6-month follow-up, quitting was observed in 17% of participants in the active arm (9% switchers and 8% complete quitters) versus 9% of the control group (6% complete quitters and 3% switchers). In longitudinal cohort studies, daily but not non-daily e-cig use was associated with higher odds of prolonged cigarette smoking abstinence compared to no e-cig use [57, 61, 62]. Some studies showed that e-cigs with higher nicotine content led to more days of smoking abstinence than lower concentrations [12, 63]. An RCT study [64] reported a relatively unsuccessful result (quit rate 7.3% at 6 months) using an e-cig with very low nicotine content (3 mg/ml). By contrast, e-cig devices and flavors are not considered to be associated with cigarette discontinuation rates [65–67]. Less information is available on the role of HTPs as a smoking cessation aid. A Cochrane analysis including 13 relevant studies (11 trials supported by tobacco companies) up to January 2021 [68] compared unwanted effects and toxin levels in individuals randomly assigned to use HTPs, to continue smoking cigarettes, or to abstain from tobacco use. Unfavorable symptoms in the short-term studies (average 13 weeks) were uncommon. An RCT including 211 individuals not motivated to quit compared the effects of the IQOS 2.4 Plus versus a refillable e-cig for 12 weeks. The abstinence rate did not differ significantly between arms at the end of the study (39.1% vs. 30.8%); therefore, the authors concluded that further studies will be needed to confirm their findings [69].

Cessation Help in ENDS Used Seeking Support for Cessation

It is increasingly reported that e-cig users may not be able to quit alone and may need help to quit. In a sample of 1988 US e-cig users, of whom 1053 and 540 were dual users and former cigarette smokers, respectively, 302 participants (15%) claimed having made a past-year quit attempt, and 1208 participants (61%) reported plans to quit e-cigs [70]. Vapers who perceived themselves as being addicted were less likely to achieve abstinence [71]. Therefore, effective interventions are needed to help individuals quit e-cigs. At present, vaping cessation help is based on the translation of results from smoking cessation studies [72]. No medication is currently approved by the FDA or EMA for vaping cessation. The UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency has approved a nicotine-containing mouth spray, already licensed for smoking cessation, for vaping cessation [73]. Varenicline demonstrated efficacy in a study including 140 daily e-cig users motivated to quit vaping. Participants were randomized to receive either varenicline (1 mg, administered twice daily for 12 weeks) plus counseling or placebo plus counseling for 12 weeks, followed by another 12-week follow-up, non-treatment phase. The biochemically validated continuous abstinence rate was significantly higher for varenicline than placebo at 12-week follow-up (40.0% vs. 20.0%; OR 2.67, 95% CI 1.25–5.68, P < 0.02) and at 24 weeks (34.3% vs. 17.2%; OR 2.52, 95% CI 1.14–5.58, P < 0.05 [74]). An exploratory trial including 30 adult daily e-cig users (50% were dual smokers) also suggested acceptable efficacy (33%, all e-cig-only users) for NRT (21-mg patches, 4-mg lozenges) plus behavioral support with 7-day point abstinence [75]. Another randomized study conducted in a remote area found that in young people (18–24 years old) regularly using e-cigs and motivated to quit, the offer of NRT increased the quit rate at the 3-month follow-up by seven points—a good albeit nonsignificant increase [76]. A double-blind RCT in 131 US adults who only vaped daily and wanted to quit found greater continuous e-cig abstinence in the active arm using a 12-week treatment with cytisine 3 mg three times daily versus the placebo group at week 16 (23.4% vs. 13.2%; OR 2.00; 95% CI 0.82–5.32; P = 0.15 [77]).

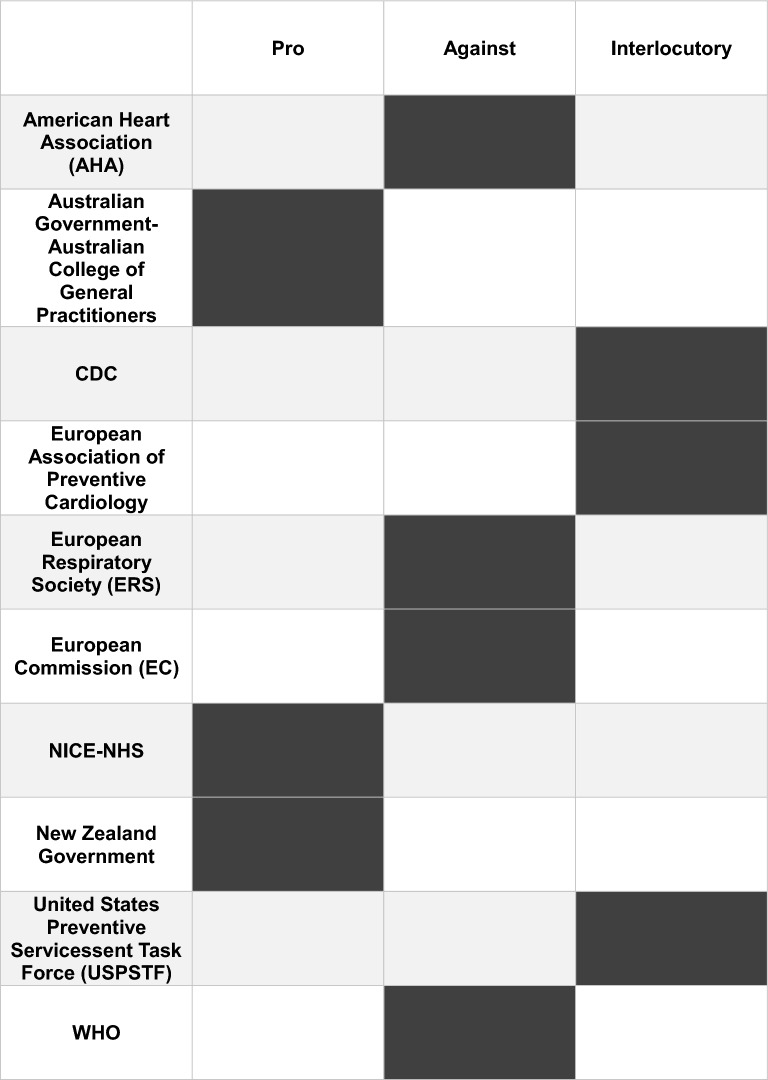

The issue of ENDS has started to attract the attention of scientific societies. Their positions on the use of these devices as a tool for smoking cessation vary and are summarized in Table 2. The lack of clear positions can be explained by the dichotomy between the experience of ENDS used as a smoking cessation tool and the possible effects that these devices could have in the long term. Further studies, particularly on the long-term effects of ENDS on human health, are needed.

Table 2.

Conclusions

Although promoted as cigarette smoking cessation aids, manufacturers first proposed ENDS as consumer products, probably for commercial reasons. While RCTs show that e-cigs—the most commonly used type of ENDS—may be effective as smoking cessation aids, their role in real life is debated. At present, there is no clear association between the prevalence of e-cig use among current smokers and overall quit rates [78]. Some scientific organizations endorse the use of ENDS to help in quitting and believe that they can reduce exposure to harmful chemicals with respect to tobacco cigarette smoking, at least if the cigarette user is able to switch completely away from smoking [79–81]. Other associations advise against the use of ENDS (Table 2 [82–96]), as their effect on health in the long term is unknown, but not risk-free. In addition, the recent increased use of novel e-cigs mainly in never-smoker youth is a matter of concern, because exposure to nicotine during adolescence can damage normal brain development [97, 98], seems to increase the potential for abuse liability [99], and is associated with increased risk of subsequent smoking initiation with respect to never-vapers [48, 100]. Health authorities strictly monitor ENDS use, usually consider them to be tobacco products, and try to place limitations on their wide commercialization, above all in never-smoker adolescents. However, it should be remembered that strict restrictions might lead people to seek other ways to find ENDS, as shown by the large role of the black market in Australia, where selling e-cigs without a medical prescription was forbidden [101].

Regardless of our own opinion on ENDS and the health risks described in the previous sections, physicians should regularly ask for ENDS use at each visit (see Table 4 for main suggested items, i.e., recording how much and which ENDS are used [type—disposable, not disposable; use at least once a day, not daily], and the nicotine dosage). In a large sample of 134,931 US adult patients referred to primary care clinics in 2022, rates of e-cig screening (n = 46,997; 34.8%) were significantly lower than those for tobacco (99.5%) and alcohol (96.2%) use [102]. Clinicians should also know how to manage ENDS. They should discourage uptake of ENDS among never-smokers and long-term former smokers, advise against dual smoking, and suggest ENDS use only for quitting cigarettes. ENDS is now the most widely used pharmacological support for smoking cessation not only in the UK (where e-cigs have been promoted as support for quitting), but even in the USA, France (27% of attempts), Greece (26%), Germany (15%), and Italy (7%, 103). Many experts do not suggest ENDS as the first-choice pharmacological treatment in individuals requiring support for cigarette cessation attempts, but we cannot exclude their use if the individual desires it, eventually in association with other drugs. Dependent dual smokers who succeed in stopping cigarettes should gradually reduce their vaping frequency or nicotine strength only when they feel confident that they can do this without going back to smoking. E-cigs should not be used indefinitely. Proper information from health caregivers might play a critical role in success among smokers using ENDS for quitting [125]. In this respect, it may be interesting to remember the findings of a national US cohort study where smokers who used e-cigs on their own were less successful in quitting [58].

Acknowledgements

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

The authors did not receive any medical writing or editorial support during manuscript preparation. Editorial assistance was limited to final language review prior to submission.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Jean-Guillaume Starnini, Federico Nigroli, Giulio Natalello, Chiara Diana, Elena Bargagli, Andrea Sisto Melani; writing—original draft preparation: Jean-Guillaume Starnini, Federico Nigroli, Giulio Natalello, Chiara Diana, Andrea Sisto Melani; writing—review and editing: Jean-Guillaume Starnini, Federico Nigroli, Giulio Natalello, Chiara Diana; visualization: Jean-Guillaume Starnini, Federico Nigroli, Giulio Natalello, Chiara Diana; supervision: Elena Bargagli, Andrea Sisto Melani. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study. All data can be found in the articles shown in the bibliography.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Jean-Guillaume Starnini, Federico Nigroli, Giulio Natalello, Elena Bargagli, and Andrea Sisto Melani have nothing to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Gordon T, Karey E, Rebuli ME, Escobar YH, Jaspers I, Chen LC. E-Cigarette toxicology. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2022;62:301–22. 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-042921-084202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belushkin M, Tafin Djoko D, Esposito M, et al. Selected harmful and potentially harmful constituents levels in commercial E-Cigarettes. Chem Res Toxicol. 2020;33(2):657–68. 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.9b00470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Upadhyay S, Rahman M, Johanson G, Palmberg L, Ganguly K. Heated tobacco products: Insights into composition and toxicity. Toxics. 2023;11(8):667. 10.3390/toxics11080667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cordery S, Thompson K, Stevenson M, et al. The product science of electrically heated tobacco products: an updated narrative review of the scientific literature. Cureus. 2024;16(5): e61223. 10.7759/cureus.61223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghuman A, Choudhary P, Kasana J, et al. A systematic literature review on the composition, health impacts, and regulatory dynamics of vaping. Cureus. 2024;16(8): e66068. 10.7759/cureus.66068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Commission. EU Rules on Tobacco Products.2016; Available from: https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/7223d20d-4dad-451e-bcc7-ac134fb6d1d7_en?filename=tobacco_info-graph2_en.pdf27. Last accessed 1st March 2025

- 7.Jha P, Peto R. Global effects of smoking, of quitting, and of taxing tobacco. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(1):60–8. 10.1056/NEJMra1308383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction. 2004;99(1):29–38. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filippidis FT, Laverty AA, Mons U, Jimenez-Ruiz C, Vardavas CI. Changes in smoking cessation assistance in the European Union between 2012 and 2017: pharmacotherapy versus counselling versus E-Cigarette. Tob Control. 2019;28(1):95–100. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindson N, Theodoulou A, Ordóñez-Mena JM, Fanshawe TR, Sutton AJ, Livingstone-Banks J, Hajizadeh A, Zhu S, Aveyard P, Freeman SC, Agrawal S, Hartmann-Boyce J. Pharmacological and electronic cigarette interventions for smoking cessation in adults: component network meta-analyses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;9(9):CD015226. 10.1002/14651858.CD015226.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benowitz NL. Nicotine addiction. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2295–303. 10.1056/NEJMra0809890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldenson NI, Augustson EM, Chen J, Shiffman S. Pharmacokinetic and subjective assessment of prototype JUUL2 electronic nicotine delivery system in two nicotine concentrations, JUUL system, IQOS, and combustible cigarette. Psychopharmacology. 2022;239(3):977–88. 10.1007/s00213-022-06100-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell C, Jin T, Round EK, Nelson PR, Baxter S. Abuse liability of two electronic nicotine delivery systems compared with combustible cigarettes and nicotine gum from an open-label randomized crossover study. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):18951. 10.1038/s41598-023-45894-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christen SE, Hermann L, Bekka E, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of inhaled nicotine salt and free-base using an E-Cigarette: a randomized crossover study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2024;26(10):1313–21. 10.1093/ntr/ntae074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDermott S, Reichmann K, Mason E, Fearon IM, O’Connell G, Nahde T. An assessment of nicotine pharmacokinetics and subjective effects of the pulze heated tobacco system compared with cigarettes. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):9037. 10.1038/s41598-023-36259-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanobe MN, Makena P, Prevette K, Baxter SA. Assessment of abuse liability and nicotine pharmacokinetics of glo heated tobacco products in a randomized, crossover study. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2024;49(6):733–50. 10.1007/s13318-024-00921-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maloney S, Eversole A, Crabtree M, et al. Acute effects of JUUL and IQOS in cigarette smokers. Tob Control. 2021;30:449–52. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leavens ELS, Lambart L, Diaz FJ, Wagener TL, Ahluwalia JS, Benowitz N, Nollen NL. Nicotine delivery and changes in withdrawal and craving during acute electronic cigarette, heated tobacco product, and cigarette use among a sample of black and white people who smoke. Nicotine Tob Res. 2024;26(6):780–4. 10.1093/ntr/ntad247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitajima T, Hisamatsu T, Kanda H, Tabuchi T. Nicotine dependence based on the tobacco dependence screener among heated tobacco products users in Japan, 2022–2023: The JASTIS study. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2025;45(1): e12512. 10.1002/npr2.12512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller CR, Schneller-Najm LM, Leigh NJ, Agar T, Quah AC, Cummings KM, Fong GT, O’Connor RJ, Goniewicz ML. Biomarkers of exposure to nicotine and selected toxicants in individuals who use alternative tobacco Products sold in Japan and Canada from 2018 to 2019. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2025;34(2):298–307. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-24-0836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akiyama Y, Sherwood N. Systematic review of biomarker findings from clinical studies of electronic cigarettes and heated tobacco products. Toxicol Rep. 2021;8:282–94. 10.1016/j.toxrep.2021.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dai H, Benowitz NL, Achutan C, Farazi PA, Degarege A, Khan AS. Exposure to toxicants associated with use and transitions between cigarettes, E-Cigarette, and no tobacco. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2): e2147891. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.47891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heywood J, Abele G, Langenbach B, Litvin S, Smallets S, Paustenbach D. Composition of E-Cigarette aerosols: a review and risk assessment of selected compounds. J Appl Toxicol. 2025;45(3):364–86. 10.1002/jat.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wills TA, Soneji SS, Choi K, et al. E-Cigarette use and respiratory disorders: an integrative review of converging evidence from epidemiological and laboratory studies. Eur Respir J. 2021;57(1):1901815. 10.1183/13993003.01815-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rebuli ME, Rose JJ, Noël A, et al. The E-cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injury epidemic: pathogenesis, management, and future directions: an official American Thoracic Society Workshop report. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2023;20(1):1–17. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202209-796ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim CCW, Sun T, Leung J, et al. Prevalence of adolescent cannabis vaping: a systematic review and meta-analysis of US and Canadian studies. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176:42–51. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.4102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joshi D, Duong M, Kirkland S, Raina P. Impact of electronic cigarette ever use on lung function in adults aged 45–85: a cross-sectional analysis from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. BMJ Open. 2021;11(10): e051519. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allbright K, Villandre J, Crotty Alexander LE, Zhang M, Benam KH, Evankovich J, Königshoff M, Chandra D. The paradox of the safer cigarette: understanding the pulmonary effects of electronic cigarettes. Eur Respir J. 2024;63(6):2301494. 10.1183/13993003.01494-2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song C, Hao X, Critselis E, Panagiotakos D. The impact of electronic cigarette use on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Med. 2025;239: 107985. 10.1016/j.rmed.2025.107985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qureshi MA, Vernooij RWM, La Rosa GRM, Polosa R, O'Leary R. Respiratory health effects of E-Cigarette substitution for tobacco cigarettes: a systematic review. Harm Reduct J. 2023;20(1):143. 10.1186/s12954-023-00877-9. Erratum in: Harm Reduct J. 2024;21(1):60. 10.1186/s12954-024-00968-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Odani S, Koyama S, Miyashiro I, Tanigami H, Ohashi Y, Tabuchi T. Association between heated tobacco product use and airway obstruction: a single-centre observational study, Japan. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2024;11(1): e001793. 10.1136/bmjresp-2023-001793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polosa R, Morjaria JB, Prosperini U, Busà B, Pennisi A, Gussoni G, Rust S, Maglia M, Caponnetto P. Health outcomes in COPD smokers using heated tobacco products: a 3-year follow-up. Intern Emerg Med. 2021;16(3):687-696. 10.1007/s11739-021-02674-3. Erratum in: Intern Emerg Med. 2022;17(6):1849. 10.1007/s11739-022-03043-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Benowitz NL, Liakoni E. Tobacco use disorder and cardiovascular health. Addiction. 2022;117(4):1128–38. 10.1111/add.15703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang D, Choi KH, Kim H, Park H, Heo J, Park TK, Lee JM, Cho J, Yang JH, Hahn JY, Choi SH, Gwon HC, Song YB. Prognosis after switching to electronic cigarettes following percutaneous coronary intervention: a Korean nationwide study. Eur Heart J. 2025;46(1):84–95. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi S, Lee K, Park SM. Combined associations of changes in noncombustible nicotine or tobacco product and combustible cigarette use habits with subsequent short-term cardiovascular disease risk among South Korean men: a Nationwide Cohort Study. Circulation. 2021;144(19):1528-1538. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.054967. Erratum in: Circulation. 2021;144(19):e306. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001034. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Alnajem A, Redha A, Alroumi D, et al. Use of electronic cigarettes and second-hand exposure to their aerosols are associated with asthma symptoms among adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):300. 10.1186/s12931-020-01569-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cui T, Lu R, Liu C, Wu Z, Jiang X, Liu Y, Pan S, Li Y. Characteristics of second-hand exposure to aerosols from E-Cigarettes: a literature review since 2010. Sci Total Environ. 2024;926: 171829. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.171829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tattan-Birch H, Brown J, Jackson SE, Jarvis MJ, Shahab L. Secondhand nicotine absorption from E-Cigarette vapor vs tobacco smoke in children. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(7): e2421246. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.21246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lampos S, Kostenidou E, Farsalinos K, Zagoriti Z, Ntoukas A, Dalamarinis K, Savranakis P, Lagoumintzis G, Poulas K. Real-time assessment of E-Cigarettes and conventional cigarettes emissions: aerosol size distributions, mass and number concentrations. Toxics. 2019;7(3):45. 10.3390/toxics7030045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Odani S, Tabuchi T. Prevalence of heated tobacco product use in Japan: the 2020 JASTIS study. Tob Control. 2022;31(e1):e64–5. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Office for National Statistics (ONS), released 5 September 2023, ONS website, statistical bulletin, Adult smoking habits in the UK: 2022 Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandlifeexpectancies/bulletins/adultsmokinghabitsingreatbritain/2022#E-Cigarette-use-and-vaping-prevalence-in-great-britain

- 42.Smoking Toolkit Study (https://smokinginengland.info/graphs/top-line-findings)

- 43.Jackson SE, Tattan-Birch H, Shahab L, Brown J. Trends in long term vaping among adults in England, 2013–23: population based study. BMJ. 2024;386: e079016. 10.1136/bmj-2023-079016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pisinger C, Rasmussen SKB. The health effects of real-world dual use of electronic and conventional cigarettes versus the health effects of exclusive smoking of conventional cigarettes: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(20):13687. 10.3390/ijerph192013687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Piper ME, Baker TB, Benowitz NL, Jorenby DE. Changes in Use Patterns Over 1 Year Among Smokers and Dual Users of Combustible and Electronic Cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(5):672-680. 10.1093/ntr/ntz065. Erratum in: Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(10):1934. 10.1093/ntr/ntz164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Jackson SE, Shahab L, Tattan-Birch H, Brown J. Vaping among adults in England who have never regularly smoked: a population-based study, 2016–24. Lancet Public Health. 2024;9(10):e755–65. 10.1016/S2468-2667(24)00183-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller CR, Sutanto E, Smith DM, Hitchman SC, Gravely S, Yong HH, Borland R, O’Connor RJ, Cummings KM, Fong GT, Hyland A, Quah ACK, Goniewicz ML. Characterizing heated tobacco product use among adult cigarette smokers and nicotine vaping product users in the 2018 ITC four country smoking & vaping survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2022;24(4):493–502. 10.1093/ntr/ntab217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sreeramareddy CT, Acharya K, Manoharan A, Oo PS. Changes in E-Cigarette use, cigarette smoking, and dual-use among the Youth (13–15 Years) in 10 countries (2013–2019)-analyses of global youth tobacco surveys. Nicotine Tob Res. 2024;26(2):142–50. 10.1093/ntr/ntad124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gallus S, Stival C, McKee M, Carreras G, Gorini G, Odone A, van den Brandt PA, Pacifici R, Lugo A. Impact of electronic cigarette and heated tobacco product on conventional smoking: an Italian prospective cohort study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tob Control. 2024;33(2):267–70. 10.1136/tc-2022-057368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsuyama Y, Tabuchi T. Heated tobacco product use and combustible cigarette smoking relapse/initiation among former/never smokers in Japan: the JASTIS 2019 study with 1-year follow-up. Tob Control. 2022;31(4):520–6. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Odani S, Tsuno K, Agaku IT, Tabuchi T. Heated tobacco products do not help smokers quit or prevent relapse: a longitudinal study in Japan. Tob Control. 2023. 10.1136/tc-2022-057613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Royal College of Physicians. RCP advice E-Cigarettes-and-harm-reduction_executive-summary_and recommendations. Available at: https://www.rcp.ac.uk/policy-and-campaigns/policy-documents/E-Cigarettes-and-harm-reduction-an-evidence-review/pdf Last accessed March 1st, 2024.

- 53.Lindson N, Butler AR, McRobbie H, Bullen C, Hajek P, Wu AD, Begh R, Theodoulou A, Notley C, Rigotti NA, Turner T, Livingstone-Banks J, Morris T, Hartmann-Boyce J. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2025;1(1):CD010216. 10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tuisku A, Rahkola M, Nieminen P, Toljamo T. Electronic Cigarettes vs Varenicline for Smoking Cessation in Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2024;184(8):915-921. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.1822. Erratum in: JAMA Intern Med. 2024;184(8):993. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.3981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Tattan-Birch H, Kock L, Brown J, Beard E, Bauld L, West R, Shahab L. E-Cigarettes to augment stop smoking in-person support and treatment With Varenicline (E-ASSIST): a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2023;25(3):395–403. 10.1093/ntr/ntac149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hajek P, Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, Pesola F, Myers Smith K, Bisal N, Li J, Parrott S, Sasieni P, Dawkins L, Ross L, Goniewicz M, Wu Q, McRobbie HJ. A randomized trial of E-Cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(7):629–37. 10.1056/NEJMoa1808779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McNeill A, Simonavičius E, Brose L, Taylor E, East K, Zuikova E, et al. Nicotine vaping in England: an evidence update including health risks and perceptions, 2022. A report commissioned by the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. London: Office for Health Improvement and Disparities; 2022. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1107701/Nicotine-vaping-in-England-2022-report.pdf. Last Accessed March 1st, 2024.

- 58.Wang RJ, Bhadriraju S, Glantz SA. E-Cigarette use and adult cigarette smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(2):230–46. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen R, Pierce JP, Leas EC, Benmarhnia T, Strong DR, White MM, Stone M, Trinidad DR, McMenamin SB, Messer K. Effectiveness of E-Cigarettes as aids for smoking cessation: evidence from the PATH Study cohort, 2017–2019. Tob Control. 2023;32(e2):e145–52. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pierce JP, Luo M, McMenamin SB, Stone MD, Leas EC, Strong D, Shi Y, Kealey S, Benmarhnia T, Messer K. Declines in cigarette smoking among US adolescents and young adults: indications of independence from E-Cigarette vaping surge. Tob Control. 2023. 10.1136/tc-2022-057907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carpenter MJ, Wahlquist AE, Dahne J, Gray KM, Cummings KM, Warren G, Wagener TL, Goniewicz ML, Smith TT. Effect of unguided E-Cigarette provision on uptake, use, and smoking cessation among adults who smoke in the USA: a naturalistic, randomised, controlled clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;63: 102142. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Glasser AM, Vojjala M, Cantrell J, evy DT, Giovenco DP, Abrams D, Niaura R. Patterns of E-Cigarette use and subsequent cigarette smoking cessation over two years (2013/2014 to 2015/2016) in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(4):669–677. 10.1093/ntr/ntaa182 Erratum in: Nicotine Tob Res. 2024 10.1093/ntr/ntae234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Kasza KA, Edwards KC, Kimmel HL, Anesetti-Rothermel A, Cummings KM, Niaura RS, Sharma A, Ellis EM, Jackson R, Blanco C, Silveira ML, Hatsukami DK, Hyland A. Association of E-Cigarette Use With Discontinuation of Cigarette Smoking Among Adult Smokers Who Were Initially Never Planning to Quit. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(12):e2140880. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40880. Erratum in: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.26687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Foulds J, Cobb CO, Yen MS, Veldheer S, Brosnan P, Yingst J, Hrabovsky S, Lopez AA, Allen SI, Bullen C, Wang X, Sciamanna C, Hammett E, Hummer BL, Lester C, Richie JP, Chowdhury N, Graham JT, Kang L, Sun S, Eissenberg T. Effect of electronic nicotine delivery systems on cigarette abstinence in smokers with no plans to quit: exploratory analysis of a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2022;24(7):955–61. 10.1093/ntr/ntab247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hajek P, Przulj D, Phillips A, Anderson R, McRobbie H. Nicotine delivery to users from cigarettes and from different types of E-Cigarettes. Psychopharmacology. 2017;234(5):773–9. 10.1007/s00213-016-4512-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kasza KA, Rivard C, Seo YS, Reid JL, Gravely S, Fong GT, Hammond D, Hyland A. Use of electronic nicotine delivery systems or cigarette smoking after US Food and drug administration-prioritized enforcement against fruit-flavored cartridges. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(6): e2321109. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.21109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gravely S, Smith TT, Toll BA, Ashley D, Driezen P, Levy DT, Quah ACK, Fong GT, Michael CK. Electronic nicotine delivery system flavors, devices, and brands used by adults in the United States who smoke and formerly smoked in 2022: Findings from the United States International Tobacco Control Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey. Prev Med Rep. 2024;47: 102905. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2024.102905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kasza KA, Rivard C, Goniewicz ML, Fong GT, Hammond D, Cummings KM, Hyland A. E-Cigarette characteristics and cigarette cessation among adults who use E-Cigarettes. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(8): e2423960. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.23960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tattan-Birch H, Hartmann-Boyce J, Kock L, Simonavicius E, Brose L, Jackson S, Shahab L, Brown J. Heated tobacco products for smoking cessation and reducing smoking prevalence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;1(1):CD013790. 10.1002/14651858.CD013790.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Caponnetto P, Campagna D, Maglia M, et al. Comparing the effectiveness, tolerability, and acceptability of heated tobacco products and refillable electronic cigarettes for cigarette substitution (CEASEFIRE): randomized controlled trial. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2023;9: e42628. 10.2196/42628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Palmer AM, Smith TT, Nahhas GJ, Rojewski AM, Sanford BT, Carpenter MJ, Toll BA. Interest in quitting E-Cigarettes among adult E-Cigarette users with and without cigarette smoking history. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4): e214146. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.4146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Koops A, Yong HH, Borland R, McNeill A, Hyland A, Lohner V, Mons U. Does perceived vaping addiction predict subsequent vaping cessation behaviour among adults who use nicotine vaping products regularly? Addict Behav. 2025;160: 108172. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2024.108172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kundu A, Seth S, Felsky D, Moraes TJ, Selby P, Chaiton M. A systematic review of predictors of vaping cessation among young people. Nicotine Tob Res. 2025;27(2):169–78. 10.1093/ntr/ntae181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training. Vaping: a guide for health and social care professionals. Available at: https://www.ncsct.co.uk/library/view/pdf/Vaping-a-guide-for-health-and-socialcare-professionals.pdf Last accessed March 1st, 2024.

- 75.Caponnetto P, Campagna D, Ahluwalia JS, Russell C, Maglia M, Riela PM, Longo CF, Busa B, Polosa R. Varenicline and counseling for vaping cessation: a double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Med. 2023;21(1):220. 10.1186/s12916-023-02919-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Palmer AM, Carpenter MJ, Rojewski AM, Haire K, Baker NL, Toll BA. Nicotine replacement therapy for vaping cessation among mono and dual users: a mixed methods preliminary study. Addict Behav. 2023;139: 107579. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vickerman KA, Carpenter KM, Mullis K, Shoben AB, Nemeth J, Mayers E, Klein EG. Quitline-based young adult vaping cessation: a randomized clinical trial examining NRT and mHealth. Am J Prev Med. 2025;68(2):366–76. 10.1016/j.amepre.2024.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rigotti NA, Benowitz NL, Prochaska JJ, Cain DF, Ball J, Clarke A, Blumenstein BA, Jacobs C. Cytisinicline for vaping cessation in adults using nicotine E-Cigarettes: The ORCA-V1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2024;184(8):922–30. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jackson SE, Brown J, Beard E. Associations of prevalence of E-Cigarette use with quit attempts, quit success, use of smoking cessation medication, and the overall quit rate among smokers in England: a time-series analysis of population trends 2007–2022. Nicotine Tob Res. 2024;26(7):826–34. 10.1093/ntr/ntae007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on the Review of the Health Effects of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. Eaton DL, Kwan LY, Stratton K, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2018 Jan 23.

- 81.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NICE guideline [NG209] - Tobacco: preventing uptake, promoting quitting and treating dependence – 1.12 Stop-smoking interventions. November 30, 2021. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng209/chapter/Recommendations-on-treating-tobacco-dependence#stop-smoking-interventions [PubMed]

- 82.New Zealand guidelines for helping people to stop Smoking. Ministry of Health, New Zealand Government; 2021. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/the-new-zealand-guidelines-for-helping-people-to-stop-smoking-2021.pdf. Last Accessed, 8 Oct 2024

- 83.Australian Government. Department of health policy and regulatory approach to electronic cigarettes (E-Cigarettes) in Australia; 2019. Available at: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/policy-and-regulatory-approach-to-electronic-cigarettes-E-Cigarettes-in-australia?language=en. Last Accessed, 8th Oct 2024

- 84.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. E-Cigarettes, Vapes, and other Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/products-ingredients-components/E-Cigarettes-vapes-and-other-electronic-nicotine-delivery-systems-ends Last accessed, 8 Oct 2024

- 85.European Commission. EU Rules on Tobacco Products. 2016; Available from: https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/7223d20d-4dad-451e-bcc7-ac134fb6d1d7_en?filename=tobacco_info-graph2_en.pdf27. Last Accessed 8th Oct 2024

- 86.European Commission, Directorate-General for Communication, Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety, and quality requirements for tobacco and electronic cigarettes: report, European Commission, Law 2015/1139. Available at: https://health.ec.europa.eu/tobacco/product-regulation/electronic-cigarettes_en. Last Accessed 1st March 2025

- 87.Department of Health, Services, for Disease Control, Center for Chronic Disease Prevention, Promotion, on Smoking. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General [Internet]. 2016;1–298. Available from: https://ecigarettes.surgeongeneral.gov/documents/2016_sgr_full_report_non-508.pdf Last Accessed 1st March 2025

- 88.Bhatnagar A, Whitsel LP, Ribisl KM, Bullen C, Chaloupka F, Piano MR, Robertson RM, McAuley T, Goff D, Benowitz N, American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Electronic cigarettes: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;130(16):1418–36. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bhatnagar A, Whitsel LP, Blaha MJ, Huffman MD, Krishan-Sarin S, Maa J, Rigotti N, Robertson RM, Warner JJ. New and emerging tobacco products and the nicotine Endgame: the role of robust regulation and comprehensive tobacco control and prevention: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(19):e937–58. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rose JJ, Krishnan-Sarin S, Exil VJ, Hamburg NM, Fetterman JL, Ichinose F, Perez-Pinzon MA, Rezk-Hanna M, Williamson E, American Heart Association Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Stroke Council; and Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. Cardiopulmonary impact of electronic cigarettes and vaping products: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023;148(8):703–28. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schraufnagel DE, Blasi F, Drummond MB, Lam DC, Latif E, Rosen MJ, Sansores R, Van Zyl-Smit R, Forum of International Respiratory Societies. Electronic cigarettes. A position statement of the forum of international respiratory societies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(6):611–8. 10.1164/rccm.201407-1198PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.McDonald CF, Jones S, Beckert L, Bonevski B, Buchanan T, Bozier J, Carson-Chahhoud KV, Chapman DG, Dobler CC, Foster JM, Hamor P, Hodge S, Holmes PW, Larcombe AN, Marshall HM, McCallum GB, Miller A, Pattemore P, Roseby R, See HV, Stone E, Thompson BR, Ween MP, Peters MJ. Electronic cigarettes: a position statement from the thoracic society of Australia and New Zealand. Respirology. 2020;25(10):1082–9. 10.1111/resp.13904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hayes D Jr, Board A, Calfee CS, Ellington S, Pollack LA, Kathuria H, Eakin MN, Weissman DN, Callahan SJ, Esper AM, Crotty Alexander LE, Sharma NS, Meyer NJ, Smith LS, Novosad S, Evans ME, Goodman AB, Click ES, Robinson RT, Ewart G, Twentyman E. Pulmonary and critical care considerations for E-Cigarette, or Vaping, product use-associated lung injury. Chest. 2022;162(1):256–64. 10.1016/j.chest.2022.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chen DT, Grigg J, Filippidis FT, Tobacco Control Committee of the European Respiratory Society. European Respiratory Society statement on novel nicotine and tobacco products, their role in tobacco control and “harm reduction.” Eur Respir J. 2024;63(2):2301808. 10.1183/13993003.01808-2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kavousi M, Pisinger C, Barthelemy J-C, et al. Electronic cigarettes and health with special focus on cardiovascular effects: position paper of the European association of preventive cardiology (EAPC). Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2021;28:1552–66. 10.1177/2047487320941993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.WHO FCTC. Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. FCTC/COP8(22). Novel and Emerging Tobacco Products. Available online: https://www.who.int/fctc/cop/sessions/cop8/decisions/en/ (Accessed on 9 February 2021).

- 97.US Preventive Services Task Force, Krist AH, Davidson KW, et al. Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(3): 265–279. 10.1001/jama.2020.25019 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 98.Tobore TO. On the potential harmful effects of E-Cigarettes (EC) on the developing brain: the relationship between vaping-induced oxidative stress and adolescent/young adults social maladjustment. J Adolesc. 2019;76:202–9. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Laviolette SR. Molecular and neuronal mechanisms underlying the effects of adolescent nicotine exposure on anxiety and mood disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2021;184: 108411. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2020.108411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hammond D, Reid JL, Burkhalter R, O’Connor RJ, Goniewicz ML, Wackowski OA, Thrasher JF, Hitchman SC. Trends in e-cigarette brands, devices and the nicotine profile of products used by youth in England, Canada and the USA: 2017–2019. Tob Control. 2023;32(1):19–29. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Egger S, David M, Watts C, Dessaix A, Brooks A, Jenkinson E, Grogan P, Weber M, Luo Q, Freeman B. The association between vaping and subsequent initiation of cigarette smoking in young Australians from age 12 to 17 years: a retrospective cohort analysis using cross-sectional recall data from 5114 adolescents. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2024;48(5): 100173. 10.1016/j.anzjph.2024.100173.E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mendelsohn C, Wodak A, Hall W. How should nicotine vaping be regulated in Australia? Drug Alcohol Rev. 2023;42(5):1288–94. 10.1111/dar.13663.67.Saff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sanford BT, Rojewski AM, Palmer AM, Baker NL, Carpenter MJ, Smith TT, Toll BA. E-cigarette screening in primary care. Am J Prev Med. 2023;65(3):517–20. 10.1016/j.amepre.2023.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Eurobarometer. Attitudes of Europeans Towards Tobacco and Electronic Cigarettes. Special Eurobarometer 506. 2021. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/ResultDoc/download/DocumentKy/91136.

- 105.Prochaska JJ, Vogel EA, Benowitz N. Nicotine delivery and cigarette equivalents from vaping a JUULpod. Tob Control. 2022;31:e88–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Stiles MF, Campbell LR, Graff DW, Jones BA, Fant RV, Henningfield JE. Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic assessment of electronic cigarettes, combustible cigarettes, and nicotine gum: implications for abuse liability. Psychopharmacology. 2017;234(17):2643–55. 10.1007/s00213-017-4665-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, Pesola F, Smith KM, Hajek P. Nicotine delivery and user ratings of IQOS heated tobacco system compared with cigarettes, Juul, and refillable E-cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(11):1889–94. 10.1093/ntr/ntab094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.DeVeaugh-Geiss AM, Chen LH, Kotler ML, Ramsay LR, Durcan MJ. Pharmacokinetic comparison of two nicotine transdermal systems, a 21-mg/24-hour patch and a 25-mg/16-hour patch: a randomized, open-label, single-dose, two-way crossover study in adult smokers. Clin Ther. 2010;32(6):1140–8. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.ASH Use of vapes (e-cigarettes) among adults in Great Britain, Feb-March 2024, ash.org.uk

- 110.Odani S, Tabuchi T. Prevalence of heated tobacco product use in Japan: the 2020 JASTIS study. Tob Control. 2022;31(e1):e64–5. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tabuchi T, et al. Heat-not-burn tobacco product use in Japan: its prevalence, predictors and perceived symptoms from exposure to secondhand heat-not-burn tobacco aerosol. Tob Control. 2018;27(e1):e25–33. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kramarow EA, Elgaddal N. Current electronic cigarette use among adults aged 18 and over: United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief. 2023;475:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sparrock LS, Phan L, Chen-Sankey J, Hacker K, Ajith A, Jewett B, Choi K. Heated tobacco products: awareness, beliefs, use and susceptibility among US adult current tobacco users, 2021. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(3):2016. 10.3390/ijerph20032016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022–2023: Vaping and e-cigarette use in the NDSHS

- 115.American Heart Association (AHA):

- 116.https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-lifestyle/quit-smoking-tobacco/what-you-need-to-know-about-vaping

- 117.Australian Government: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/smoking-vaping-and-tobacco/about-vaping

- 118.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/e-cigarettes/quitting.html Food and Drug Administration (FDA): https://www.fda.gov/safety/medical-product-safety-information/e-cigarette-products-safety-communication-due-incidents-severe-respiratory-disease-associated-use-e

- 119.European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC): https://www.escardio.org/Sub-specialty-communities/European-Association-of-Preventive-Cardiology-(EAPC)/News/e-cigarettes

- 120.European Respiratory Society (ERS): https://www.ersnet.org/news-and-features/news/the-european-respiratory-society-updated-position-on-novel-nicotine-and-tobacco-products-their-role-in-tobacco-control-and-harm-reduction/

- 121.World Health Organization (WHO): https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/tobacco-e-cigarettes

- 122.United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTE): https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions

- 123.New Zealand Government (NZG): https://www.smokefree.org.nz/quit/help-and-support/how-to-quit

- 124.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE-HS): https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng209/chapter/Treating-tobacco-dependence#stop-smoking-interventions

- 125.European Commission (EC): https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-15059-2024-INIT/en/pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study. All data can be found in the articles shown in the bibliography.