Abstract

Background SRS

(Short Internodes/Stylish/SHI-Related Sequence) genes play a crucial role in plant developments, encompassing organ morphogenesis. However, at present, the biological significance of potato StSRS genes remains unknown. This study comprehensively identified and analysed the potential functions of StSRS genes in potato tuberization.

Results

Through phylogenetic and conserved motif analyses, eight members of the StSRS family were successfully identified and classified into five distinct subfamilies. The intraspecies and interspecies collinearity analyses offered insights into the evolutionary clues of the StSRS family, showing closer homology to tomato and tobacco. High-quality RNA-sequencing (Q30 > 97.16%) revealed dynamic gene expression profiles, with 146 to 997 differentially expressed transcription factors (DETFs), particularly from the MYB-related, GATA, and bHLH families. Among them, the expression of two StSRS genes, StSRS1 and StSRS8, were dramatically changed during potato tuber formation. Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) uncovered stage-specific gene modules and spotlighted hub genes. Specifically, StSRS8 was strongly associated with the Stolon stage, while StSRS1 was evidently linked to the Tuber stage. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis revealed that the transcripts of both StSRS1 and StSRS8 were predominantly expressed during potato tuberization, as compared to those in other tissues. However, it is scarcely detectable for other six StSRS genes. Furthermore, the transcripts of StSRS8 were repressed under short-day (SD) conditions.

Conclusion

These findings yield critical insights into the potato StSRS gene family and furnish essential information for further function investigation of StSRS genes, particularly StSRS1 and StSRS8, in the context of potato tuberization.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-025-07172-8.

Keywords: Potato tuberization, Transcriptome, Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA), Short internodes/Stylish (SHI/STY) and SHI-related sequence (SRS) family

Introduction

The SRS (Short Internodes/Stylish/SHI-Related Sequence) gene family is a unique, evolutionarily conserved group of plant-specific transcription factors characterized by two conserved domains: an N-terminal RING finger-like zinc finger motif that mediates protein–protein interactions, and a C-terminal IGGH domain defined by four invariant residues unique to this family [1, 2]. While these domains are conserved, sequence variation in other regions suggests functional diversification among family members. Phylogenetic analyses indicate gene duplication and divergence have expanded this family across angiosperms, contributing to the evolutionary diversification of plant morphology and development. Functionally, SRS genes regulate plant architecture and lateral organ development such as leaves, roots, and flowers primarily by modulating hormone biosynthesis and signaling pathways, particularly those involving auxin [3]. These transcription factors integrate hormonal and developmental signals to finely tune growth responses, influencing plant stature and organ patterning. Their roles in coordinating hormonal crosstalk involving gibberellin and cytokinin highlight their broad regulatory potential [4].

The regulatory mechanisms of SRS genes have been most extensively studied in model plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana, where they orchestrate diverse developmental processes. For example, Arabidopsis LATERAL ROOT PRIMORDIUM1 (LRP1) interacts with chromatin remodeling complexes to regulate auxin-responsive gene expression during lateral root initiation. Together with STY1, LRP1 directly controls YUCCA4 (YUC4), a key enzyme in auxin biosynthesis, maintaining auxin homeostasis essential for organogenesis [1, 5]. Beyond roots, SRS transcription factors modulate shoot growth and floral patterning by regulating crosstalk between auxin and gibberellin signaling pathways, coordinating cell elongation and organ morphogenesis [6]. The conservation of these roles across species is evident: in barley (Hordeum vulgare), they regulate inflorescence architecture; in maize (Zea mays), root development and nutrient uptake via auxin pathways; in the moss (Physcomitrella patens), developmental transitions through auxin biosynthesis; and in rice (Oryza sativa), shoot architecture and plant stature [7, 8]. Recent studies in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) reveal additional functions in abiotic stress tolerance, with genes such as SlSRS3 and SlSRS7 responding to drought and salt stresses [9]. Notwithstanding these advancements, the intricate regulatory networks of SRS genes remain only partially deciphered. This is particularly true in economically significant tuber crops such as potato (Solanum tuberosum). In potato, tuberization, a pivotal process for determining yield, involves the SRS genes, yet the roles of these genes in this process have not been fully elucidated.

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) is a globally important food crop with substantial nutritional and economic value [10, 11]. Although tuber tuberization is a crucial factor determining yield, the molecular mechanisms governing this process are still only partially understood [12–14]. The regulatory network governing tuberization is highly intricate and influenced by many factors, including environmental cues and genetic components [15]. Among these, photoperiodic regulation has been extensively studied, with several key signalling molecules identified as critical regulators of tuberization. These include StPHYB (PHYTOCHROME B), StSP6A (SELF-PRUNING 6 A), StCO (CONSTANS), StCDF1 (CYCLING DOF FACTOR 1), and StBEL5 (BEL1-LIKE TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR 5). Notably, StSP6A, StCDF1, and StBEL5 act as positive regulators of tuber formation, promoting the transition to tuber [16, 17]. In contrast, StPHYB and StCO function as negative regulators, suppressing tuberization under non-inductive conditions [16]. Recent work implicated that StPHYF in modulating tuberization via circadian and source-sink pathways [18].

Recent advances in transcriptomic technologies have enabled deeper insights into the complex gene regulatory networks controlling plant developmental transitions [19–24]. Moreover, Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis WGCNA delineates co-expression modules and hub genes governing specific developmental stages [14, 15, 25–27].

In the current study, we hypothesized that members of the SRS gene family serve as pivotal regulators of potato tuberization by modulating transcriptional networks. To verify this hypothesis, we adopted a comprehensive strategy that integrated genome-wide identification of SRS genes, transcriptome profiling, and Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA). The aims of this research were as follows: (i) to characterize the structural and evolutionary characteristics of the SRS gene family in potato; (ii) to investigate their spatiotemporal expression patterns during tuberization; and (iii) to identify candidate SRS genes and their co-expression modules associated with tuberization. This integrative analysis is intended to uncover novel regulatory elements involved in tuber formation and lay a foundation for future functional validation.

Materials and methods

Plant and experimental details

In this study, the potato cultivar “Solanum tuberosum cv. E-potato 3 (E3)” was provided by prof. Botao Song, National Key Laboratory for Germplasm Innovation and Utilization of Horticultural Crops, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, Hubei 430,070, China. Potato plants (E3) were propagated in vitro as single-node stem cuttings on 4% (w/v) sucrose-supplemented Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium. The cultures have been kept in controlled environmental conditions at a photoperiod of 16 h in light and 8 h in darkness with a light intensity of 100 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹. After three weeks of in vitro growth, individual potato seedlings were transferred to plastic pots (20 cm in diameter) containing a 3:1 (v/v) soil-vermiculite mixture. The plants were cultivated in a growth chamber set at 20 ± 2℃ under medium photoperiod conditions (12 h light/12 h dark) with a light intensity of 250 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹ for four weeks. Sampling was performed based on the stolons’ subapical diameter and morphological characteristics. Four distinct developmental stages were identified and categorized as follows: non-swollen stolons (Stolon), swelling stolons (Swelling), tuber initiation stage (Initiation), and small tubers (Tuber), as illustrated in Fig. 1 [28]. Samples from each category were collected, immediately placed in 50 mL RNase-free centrifuge tubes, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80℃ for subsequent transcriptome sequencing analysis. Each experimental group included a minimum of three independent biological replicates to ensure statistical robustness.

Fig. 1.

Chromosomal distribution of StSRS genes. Chromosomal information for the StSRS genes was obtained from the S. tuberosum genome annotation file and TBtools was used to generate this figure

High-throughput RNA-Seq and data analysis

RNA sequencing was performed by Frasergen (Wuhan, China) using DNB T7 sequencing technology. The sequencing method was paired-end sequencing, with each read length set to 150 base pairs (bp). Quality control and pre-processing of raw sequencing data were conducted using the fastp tool. Clean reads were obtained by filtering out reads containing adapter sequences, reads with an N ratio exceeding 10%, reads composed entirely of A bases, and reads with more than 50% of bases having a quality score (Q) ≤ 20 [29]. A ribosome database was constructed to remove ribosomal RNA (rRNA) contamination by extracting sequences annotated with rRNA keywords from the NCBI GenBank database, specifically targeting potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Clean reads were then aligned to this potato ribosome database using the bowtie2 short-read alignment tool. Reads that matched the ribosome database were discarded without allowing mismatches, while the remaining unmapped reads were retained for downstream transcriptomic analysis [30, 31]. Subsequent alignment of the unmapped reads to the Solanum Tuberosum Group Phureja clone DM1-3 (DM) v6.1 reference genome was performed using HISAT2 software (v2.1.0). Based on the alignment results generated by HISAT2, String Tie was used to reconstruct transcripts and quantify gene expression levels across all samples. Gene expression levels were normalized and calculated as fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped (FPKM) [32]. Differential gene expression analysis was conducted using DESeq2 software (v1.20.0) implemented in R (v3.6.0) via RStudio. Read counts were normalized, and p-values were calculated based on the DESeq2 model. To account for multiple tests, the false discovery rate (FDR) was computed. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using a significance threshold of p-value < 0.05 and an absolute log2 fold change (|log2FC|) greater than 1. These DEGs were further analysed to explore their potential roles in the biological processes under investigation [33, 34]. The sequencing raw data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database under accession number PRJNA1221064, publicly available since February 13, 2025.

Construction of Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

To identify key regulatory genes associated with tuber formation, we performed Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) using the top 5,000 most variable genes. According to previous report, several criteria were implemented for creating this co-expression network: firstly, constructing a scale-free network by setting the soft-threshold power (β) as 20 based on the scale-free topology criterion (R2 = 0.75, Fig. S1), ensuring each module consists enough genes; and conducting correlation analysis between four potato tuber formation stages and key modules [35]. Hub genes were defined based on module membership (MM) and gene significance (GS) values. Specifically, genes with MM ≥ 0.8 and GS ≥ 0.7 in MEblue and MEdarkseagreen4 were designated as hub genes [35]. These cut-offs balance statistical robustness with biological relevance, ensuring that selected genes are both central within the network and significantly correlated with tuber developmental stages. Top hub genes (HGs) and transcription factors (HTFs) were further prioritized based on their MM and GS rankings. The final co-expression network, refined by retaining interactions with topological overlap (TOM) weight ≥ 0.1, was visualized in Gephi 0.9.2. software [25].

Genome-wide identification of the SRS gene family in potato

We obtained the potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) whole genome data (v6.1) from the SpudDB database (https://spuddb.uga.edu/dm_v6_1_download.shtml), including full genome sequence, amino acid sequence, and genome annotation files; The whole genome sequence, annotation files and SRS genes amino acid sequence of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) are obtained from the TAIR website (https://www.arabidopsis.org/) obtained. The other plant species, including Pepper (Capsicum annuum), Tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana), and Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), were obtained from the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The accession numbers are GCF_002878395.1 (pepper, Capsicum annuum), GCA_034376525.1 (tobacco, Nicotiana benthamiana), and GCF_036512215.1 (tomato, Solanum lycopersicum), respectively [36].

Prediction of physiochemical properties of SRS gene family in potato

To comprehensively identify the members of the potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) SRS gene family, we use the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) SRS amino acid sequence as the query sequence, uses BLAST software to perform homology searches, and sets the parameter E-value 1e−5 for filtering. In addition, the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) file corresponding to the protein domain (PF05142) of the SRS gene family was downloaded from the Pfam database (http://pfam-legacy.xfam.org/), and Hmmsearch v3.2 was used. The software searches the amino acid sequence of the entire potato genome, and the parameters are default. The results of the two search methods are combined. After redundancy is removed, the candidate sequences are submitted to the Conserved Domains Database (CDD) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd) for verification, and the SRS genes in the potato genome is determined as family members. The identification methods of SRS family members in pepper, tobacco, and tomato are consistent with the above [20]. To verify the physiochemical properties of molecular weight (Mw) and isoelectric point (Pi) of the amino acid sequences of potato SRS gene family members were estimated using the online tool Protparam (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) [37].

Phylogenetic analysis, gene structure, and conserved motif analysis

The protein sequences of SRS genes from Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis), S. tuberosum (potato), S. lycopersicum (tomato), C. annuum (pepper), and N. benthamiana (tobacco) were used for phylogenetic analysis to elaborate the evolutionary relationship of potato SRS genes with other species. After merging the amino acid sequences of SRS gene family members from potato, Arabidopsis, tomato, pepper, and tobacco, multiple sequence alignment was performed using MUSCLE (v3.8) software. Then, MEGA11 software was used to construct a phylogenetic tree using Neighbor-Joining (NJ) with the bootstrap value set to 1,000. Finally, the iTOL (v6.7.6 https://itol.embl.de/) online website was used to visualize the phylogenetic tree [38, 39].

MEME v5.5.3 was used to analyze the conserved motifs of the amino acid sequence encoded by the potato SRS genes (set the maximum number of identifiable motifs to 10). In addition, the Conserved Domains Database (CDD) database was used to retrieve the conserved domains of SRS protein sequences, and the annotation information of the potato SRS genes was extracted from the whole-genome annotation file. Finally, TBtools (v1.120) software was used to study the conserved motif, domain, and gene structure of the potato SRS gene amino acid sequence [40].

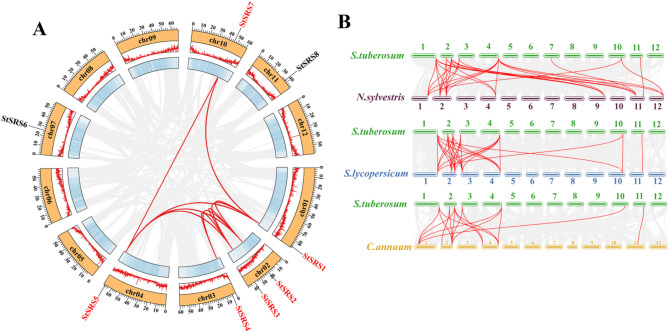

Chromosome location and collinearity analysis

The chromosomal locations of all SRS genes were determined using the positional information from the annotation of the potato (S. tuberosum) genome sequence. Gene annotation information of potato SRS family members was extracted, and TBtools (v1.120) was used to perform the chromosomal location of the identified members. In addition, MCScanX software was used to conduct intraspecific collinearity analysis of potatoes and interspecific collinearity analysis of potato (S. tuberosum), pepper (C. annuum), wild tobacco (Nicotiana sylvestris), and tomato (S. lycopersicum). The specific method used the local BlastP program for comparison, in which the E-value was set to 1e−10. Then, MSCanX was used to generate collinearity files. The intraspecific collinear gene pairs and gene duplication types of the potato StSRS genes can be seen, as well as the interspecific collinearity. TBtoolsJ and Circos Visualization Interface (CVI) were used to visualize intraspecific and interspecific collinearity, respectively, and SRS collinear gene pairs were marked in red [41].

Quantitative real-time PCR

Eight random selected genes from the co-expression module associated with stolon or tuber were screened for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) to ensure precise and reproducible sequencing results. In addition, eight potato StSRS genes were tested by qRT-PCR to confirm their expression patterns. cDNAs from four tissue samples (Stolon, Swelling, Initiation, and Tuber) were used in this experiment. Moreover, other tissues, including root, stem, and leaves from plants growing under long day condition (16 h light/8 h dark) or short day (8 h light/16 h dark), were also used. Each gene and sample were repeated in triplicate. Elongation factor-1 alpha (Stef1α) was used for each sample as an endogenous control [42, 43]. BlazeTaq™ SYBR® Green qPCR Mix 2.0 (GeneCopoeia, Rockville, MD, USA) was used for RT-qPCR reactions on a CFX96 Real-Time System (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA). Each reaction contained 1 µL of 10 × diluted cDNA strand, 5 µL of SYBR Green qPCR Mix, 4.6 µL of ddH2O, and 0.2 µL of each primer, accumulating a final volume of 10 µL in total. The formula F = 2–∆∆Ct was used to calculate the relative expression levels. Specific primers were designed using Primer3web version 4.1.0 [25] and are shown in Supplementary Table S8. Gene expression data are reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) based on three independent biological replicates. Statistical significance of differential expression was determined using a Student’s t-test, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Identification and physiochemical properties of potato StSRS family members

We systematically identified the members of the potato StSRS gene family using the Arabidopsis AtSRS amino acid sequence as a query for homology searching through BLAST. This search led to the identification of 8 members belonging to the potato StSRS gene family. A thorough physical and chemical property analysis was performed on these members, revealing key characteristics such as sequence length, molecular weight, isoelectric point, and chromosomal distribution.

The 8 StSRS gene family members are unevenly distributed across different chromosomes (chr), with 8 members located on chromosomes chr1, chr2, chr3, chr4, chr7, chr10, and chr11 (Fig. 1). The length of these proteins ranges from 175 to 383 amino acids, their molecular weights vary between 19.31 and 41.49 kD, and the isoelectric points range from 6.4 to 8.94 (Table S1). This comprehensive characterization of the potato StSRS family offers preliminary insights into their possible involvement in the physiological processes of potato plants.

Gene structure and conserved domain analysis

Using the identified protein sequences of the potato StSRS gene family members and the annotated genome sequences, the diversity of StSRS transcription factors was systematically evaluated, and their gene structures were analyzed. The results (Fig. 2) indicate that StSRS6 contains 3 exons and 2 introns, while the other StSRS genes contain 2 exons and 1 intron each. Remarkably, StSRS genes within the same subfamily share similar gene structures. Domain analysis revealed that all 8 identified StSRS genes contain the DUF702 conserved domain, confirming their classification as members of the StSRS gene family. Additionally, conserved motif analysis using the MEME online tool showed that the number of motifs in the potato StSRS protein sequences ranges from 3 to 10. Motif 1, Motif 2, and Motif 3 were present in all StSRS proteins, and motifs within the same subfamily exhibit relatively conserved patterns in both type and quantity. In contrast, motifs across different subfamilies display less conservation. These structural variations might contribute to the functional and structural diversity among members.

Fig. 2.

StSRS gene structure and conserved motifs analysis. Conserved motifs were detected using MEME and are represented by boxes of different colors

Phylogenetic analysisof SRS gene family

Furthermore, a multiple sequence alignment was performed for the SRS gene family across 5 species, including Arabidopsis, tomato, tobacco, pepper, and potato. An evolutionary tree was constructed using the Neighbor-Joining method to elucidate the phylogenetic relationships among these species. The StSRS gene family comprises 5 distinct subfamilies, with Class I, Class II, Class III, Class IV, and Class V, containing 1, 1, 1, 2, and 3 members, respectively, in the potato StSRS family. Additionally, the resulting phylogeny indicated that the potato StSRS genes form a distinct clade closely allied with those from Solanum lycopersicum (tomato). Among the 8 StSRS genes identified in potato, StSRS1, StSRS4, StSRS5, StSRS7, and StSRS8 share a closer evolutionary relationship with their tomato counterparts. StSRS2 is more closely related to a chili pepper homolog, while StSRS3 shows similarity to both tomato and pepper genes. Notably, StSRS6 appears to be evolutionarily distant from all compared StSRS genes, suggesting potential divergence in function or regulation. This phylogenetic proximity highlights a high degree of evolutionary conservation within the SRS gene family among solanaceous plants, implying potential conservation of functional roles across these species (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of SRS gene family from Solanum tuberosum, Arabidopsis thaliana, Solanum lycopersicum, Nicotiana benthamiana, and Capsicum annuum. Phylogenetic tree was constructed by MEGA11 using Neighbour-Joining method with 1,000, bootstrap values

Collinearity analysis

Gene duplication is a pivotal mechanism in promoting biological evolution and functional diversification. We performed comprehensive intraspecific and interspecific collinearity analyses to elucidate the evolutionary trajectories and duplication events within the Solanum tuberosum SRS gene family. Intraspecific analysis within the potato genome identified 10 pairs (StSRS1 and StSRS2, StSRS1 and StSRS3, StSRS2 and StSRS3, StSRS2 and StSRS4, StSRS3 and StSRS4, StSRS1 and StSRS5, StSRS2 and StSRS5, StSRS3 and StSRS5, StSRS1 and StSRS7, StSRS5 and StSRS7). Among them, 6 StSRS genes originated from segmental duplication events, emphasizing the critical role of duplication in the expansion and evolution of this gene family (Fig. 4A; Table 2).

Fig. 4.

Intraspecific and interspecific collinearity analysis of potato SRS gene family. (A) Duplication status of the StSRS gene family within the potato genome; (B) Duplication status of the SRS gene family between potato and tobacco, tomato, and pepper

Interspecific collinearity analysis was conducted to assess the evolutionary relationships of the SRS gene family with its homologs in other Solanaceae species, including Nicotiana tabacum (tobacco), Solanum lycopersicum (tomato), and Capsicum annuum (pepper). The analysis revealed 29 collinear gene pairs between potato and tobacco, 27 collinear gene pairs between potato and tomato, and 16 collinear gene pairs between potato and pepper (Fig. 4B; Table 2). This pattern suggests that potato and tobacco may have experienced similar evolutionary pressures, leading to the closest evolutionary relationship of the SRS gene family between these two species. Notably, exception of StSRS6, other seven StSRS display collinearities with all three species, highlighting their conserved evolutionary roles. These findings contribute to our understanding of the evolutionary dynamics and potential functional conservation of the SRS gene family across species.

Transcriptome analysis of potato tuberization

To uncover the role of StSRS genes involved in potato tuberization, transcriptome sequencing was conducted across four critical stages of potato tuberization: Stolon, Swelling, Initiation, and Tuber (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Transcriptomic analysis of four potato tuerization stages. A The images of four key stages of potato tuberization (Stolon, Swelling, Initiation, and Tuber), bar = 1 cm; B Principal component analysis of 12 samples; C Correlation analysis of 12 samples

After rigorous quality control, raw sequencing data were processed to remove adapter sequences and low-quality reads, yielding between 24,036,559 and 32,836,330 clean reads across 12 samples. Of these, 89.96–91.02% aligned to the reference genome, with 81.36–83.11% mapping uniquely, reflecting the high quality and reliability of the sequencing data. Quality analysis revealed that the Q30 scores indicating the proportion of bases with a quality score exceeded 97.16% in all samples (Table S3). A total of 49,642 genes were detected in each sample, of which genes with FPKM > 0 were deemed expressed. On average, 71.45% of the genes were expressed across the four developmental stages, with the overall dataset showing 73.41% expression (Table S3).

The principal component analysis (PCA) revealed the samples from the same stage showed high consistency, indicating strong reproducibility of the experimental design (Fig. 5B). These observations were corroborated by tissue correlation analysis, which highlighted robust correlations among biological replicates. The gene expression profiles across developmental stages exhibited moderate variability, with pairwise correlation coefficients ranging from 0.88 to 0.97. This suggests high transcriptional similarity across stages while maintaining stage-specific characteristics (Fig. 5C).

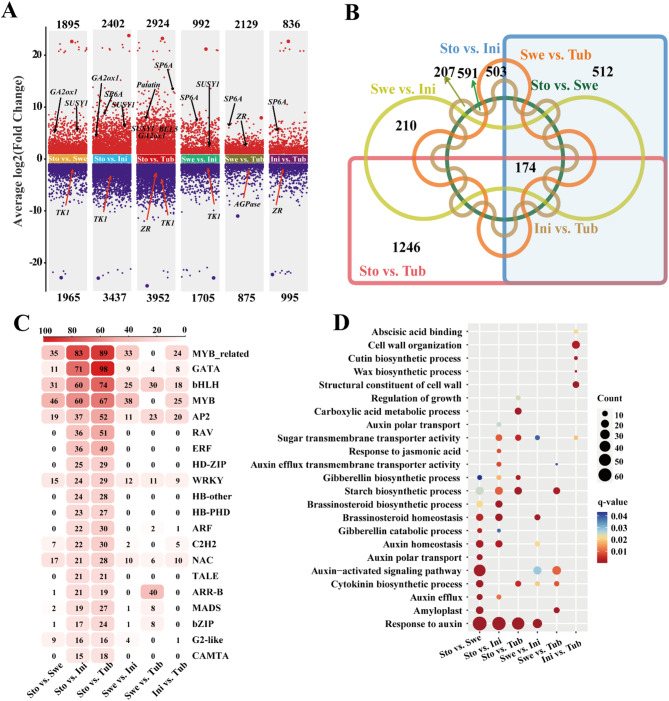

Differential expression analysis reveals key genes regulating potato tuberization

To elucidate the key genes regulation of potato tuberization, differential expression analysis was conducted across the four key developmental stages. 6 pairwise comparisons were performed Stolon vs. Swelling, Stolon vs. Initiation, Stolon vs. Tuber, Swelling vs. Initiation, Swelling vs. Tuber, and Initiation vs. Tuber yielding 3,860, 5,839, 6,876, 2,697, 3,004, and 1,831 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), respectively (Table S4). From Stolon to Swelling, 1,895 genes were upregulated and 1,965 genes were downregulated. In the transition from Swelling to Initiation, 992 genes were upregulated, and 1,705 genes were downregulated. During the progression from Initiation to Tuber, 836 genes were upregulated and 995 were downregulated (Fig. 6A). A Venn diagram summarizing DEG overlap across the 6 comparisons identified 174 shared DEGs (Fig. 6B). As expect, among the 8 StSRS transcription factor genes, the transcripts of StSRS1 and StSRS8 were significantly changed during tuberization. Additionally, we observed that the transcription levels of several known-tuberization positive regulatory genes, such as StSP6A, StbHLH93, and StAGPase, were dramatically up-regulated. While, these repressor genes, including StBRC1b and StAST1, were strongly down-regulated.

Fig. 6.

Comparative analysis of DEGs and DETFs. A Volcano plot of up-regulated and down-regulated genes for each comparison combination; B Venn plot for each comparison combination; C Heat map of DETFs for each comparison combination; D GO enrichment of DETFs for each comparison combination analysis

Transcription factors (TFs), as central regulators of plant development, were analyzed across the same pairwise comparisons. A total of 263, 798, 997, 202, 211, and 146 differentially expressed transcription factor genes (DETFs) were individually identified in the 6 comparisons, with MYB-related, GATA, bHLH, MYB, and AP2 representing the most abundant families (Fig. 6C). To elucidate the functional roles of these DETFs during potato tuber formation, Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed for each pairwise developmental stage comparison. Noticeably, the DETFs involved in phytohormone biosynthesis, metabolism, as well as signalling, especially related to auxin (GO:0009734), gibberellin (GO:0009686), brassinosteroid (GO:0010268), cytokinin (GO:0009691), abscisic acid (GO:0010427), and jasmonic acid (GO:0009753) were significantly enriched. Additionally, the sugar transmembrane transporter activity (GO:0051119) and starch biosynthetic process (GO:0019252) were also remarkedly enriched (Fig. 6D). These results underscore the critical role of transcription factors in orchestrating the developmental transitions from stolon to tuber.

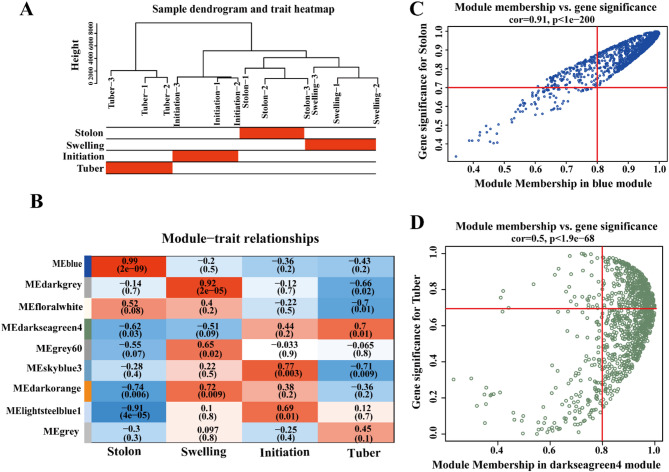

Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) identifies key modules and candidate genes in potato tuberization

Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) was conducted to identify gene modules associated with key biological processes during potato tuber development. Gene expression data from 12 samples covering four developmental stages were analyzed. Hierarchical clustering produced a dendrogram (Fig. 7A), showing clear stage-specific grouping without any outlier samples, indicating high data reliability and biological consistency. Then, a co-expression matrix was constructed using a soft-thresholding power (β) as 20 based on the scale-free topology criterion (R2 = 0.75, Fig. S1), resulting in the identification of nine distinct gene modules in each developmental stage (Fig. 7B). Of these, four modules showed strong correlations with specific developmental stages: MEblue (Stolon stage), MEdarkgrey (Swelling stage), MEskyblue3 (Initiation stage), and MEdarkseagreen4 (Tuber stage), comprising 1,028, 1,077, 95, and 929 genes, respectively, as summarized in Table S5. To identify hub genes, we assessed the correlation between gene significance (GS) and module membership (MM). For the MEblue module, a strong GS-MM correlation was observed (r = 0.91; p < 1e-200), and genes with GS ≥ 0.7 and MM ≥ 0.8 were selected as hub candidates (Fig. 7C). In the MEdarkseagreen4 module, similarly robust correlation (r = 0.5; p < 1.9e-200) supported the use of GS ≥ 0.7 and MM ≥ 0.8 thresholds (Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

WGCNA analysis of four different stages of potato tuber formation. A Sample clustering tree and trait heat map between each sample; B Correlation analysis of tissues and modules; C Scatter plot of correlation results between gene MM in MEbule module and gene GS in Stolon; D Scatter plot of correlation results between gene MM in MEdarkseagreen4 module and gene GS in Tuber

Co-expression network analysis of DEGs during stolon and tuber stages

In potato (Solanum tuberosum L.), tuber yield largely depends on tuber number, which are directly regulated by tuberization [44]. Therefore, understanding the molecular regulatory mechanisms that control the stolon-to-tuber transition is essential. Based on WGCNA, the MEblue and MEdarkseagreen4 modules exhibited the strongest associations with Stolon and Tuber stages, respectively. Interestingly, we also found that StSRS1 and StSRS8 were belonging to those two key modules, respectively. Therefore, by integrating module membership (MM), gene significance (GS), and differentially expressed genes (DEGs), the candidate hub genes (HGs) and hub transcription factors (HTFs) were identified for those two modules as potential key regulators (Table S6).

The MEblue module associated with the Stolon stage, comprising a co-expression network of 452 genes, with 33 transcription factors. Notably, StSRS8 emerged as a central hub gene, displaying co-expression with 351 (78%) of genes within the network (Fig. 8A). Moreover, StbHLH93, a known positive regulator of tuber formation, emerged as a central hub TF, displaying co-expression with 284 (63%) of genes within the network (Fig. 8A). The MEdarkseagreen4 module linked to the Tuber stage, containing 893 genes, with 79 transcription factors within it (Fig. 8B). In this module, StSRS1 came to the fore as a central hub gene, showing co-expression with 770 (86%) of gene within it. Interestingly, StDICH (StBRC1b), a known negative regulator of tuber formation, also acted as a central hub TF, playing co-expression with 640 (72%) of genes within the network (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Co-expression network diagram. A Co-expression network diagram of MEblue module related to potato Stolon stage. B Co-expression network diagram of MEdarkseagreen4 module related to potato small tuber stage. C qRT-PCR verification of the WGCNA data. Statistical significance of differential expression was determined using a Student’s t-test, with p < 0.05

To validate the WGCNA data, 8 representative DEGs were selected for expression profiling using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). The expression trends observed from qRT-PCR were highly consistent with the RNA-seq results, confirming the accuracy of transcript abundance estimates and validating the reliability of the RNA-seq data (Fig. 8C). Together, these results insighted into the complex gene regulatory networks controlling stolon-to-tuber transitions.

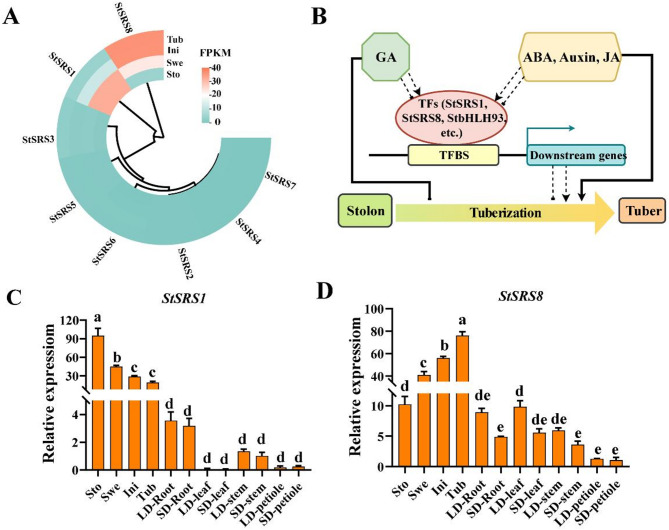

Analysis of potato StSRS genes expression pattern

First, the expression patterns of the StSRS gene family during potato tuberization were analyzed by heatmap based on our transcriptome data (Fig. 9A). The results indicated that most StSRS genes maintained stable low expression levels across the four developmental stages of tuber formation, with minimal variation. However, StSRS1 and StSRS8, exhibited significant differential expression. Specifically, the expression of StSRS1 was markedly downregulated from the Stolon stage to the Tuber stage, whereas StSRS8 was significantly upregulated during the same transition. Additionally, the expression patterns of 8 StSRS genes in different tissues of potato variety E-potato 3 (E3), including Stolon, Swelling, Initiation, Tuber, Leaves, Stem and Petiole, were monitored by qRT-PCR. Due to that it is scarcely detectable for StSRS2, StSRS3, StSRS4, StSRS5, StSRS6 and StSRS7 during potato tuberization, therefore we tested StSRS1 and StSRS8 in the subsequent experiment (Fig. 9C and D). The results exhibited that compared to other tissues, StSRS1 was predominately expressed during potato tuberization, showing a trend of substantial reduction. Moreover, the expression of StSRS1 was almost not affected by photoperiod. Conversely, even though StSRS8 was expressed in all tissues; however, which was also mainly expressed during the stolon-to-tuber transition. Notably, StSRS8 transcripts were repressed under short day (SD) condition. These observations indicate that StSRS1 and StSRS8 may play critical but distinct regulatory roles in tuber formation. Based on these results, a schematic diagram outlining the proposed mode of action was presented (Fig. 9B). During potato tuberization, plant hormones, such as gibberellin, abscisic acid, auxin, and jasmonic acid, exert antagonistic effects. This is mainly achieved through the direct or indirect regulation of the expression levels of crucial transcription factors, including StSRS1, StSRS8, StbHLH93, etc. Moreover, these hormones may govern the stolon-to-tuber transition through other pathways. Nonetheless, experimental validation is required to substantiate these putative regulatory functions.

Fig. 9.

Expression analysis of StSRS gene family in different tissues of potato. A Heatmap analysis of expression levels of the StSRS gene family in the four stages of tuber formation; B The schematic diagram outlining the proposed mode of action. GA, gibberellin; ABA, abscisic acid, JA, jasmonic acid; TFs, transcription factors; TFBS, transcription factor binding sites; C, D qRT-PCR analysis of the StSRS1 and StSRS8 in different tissues of potato. Statistical significance of differential expression was determined using a Student’s t-test, with p < 0.05

Discussion

The present study comprehensively explores the potential roles of StSRS genes driving potato tuber tuberization, integrating transcriptomic data, Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA), gene co-expression networks, and a detailed characterization of the StSRS gene family. The SRS gene was first characterized in Arabidopsis thaliana through analysis of a dwarf mutant phenotype. Following its discovery, orthologous SRS genes have been identified in phylogenetically diverse species, including the moss (Physcomitrella patens), the crop plants Brassica rapa, Zea mays, Hordeum vulgare, and Oryza sativa, as well as additional members within Arabidopsis itself. This expansion highlights the evolutionary conservation and functional significance of SRS genes across the plant kingdom [7, 8, 45].

The systematic identification and characterization of the potato StSRS gene family revealed eight members with diverse physical and chemical properties. The uneven distribution of these genes across chromosomes and their conserved domain structures suggests functional specialization within the family. Phylogenetic analysis shows potato StSRS genes closely relate to tomato homologs, reflecting conservation within Solanaceae. Conserved motifs and domain structures further support their roles in plant development and stress responses [9, 46]. As revealed by collinearity analysis, gene duplication events played a significant role in potatoes expansion and diversification of the StSRS gene family. Identifying segmental duplication events and interspecific collinear gene pairs highlights the evolutionary dynamics of this gene family. These findings align with previous studies emphasizing the role of gene duplication in driving functional diversification and plant adaptation [47, 48]. Expression analysis of StSRS genes in potato revealed tissue-specific and developmentally regulated expression patterns. StSRS1 and StSRS8 exhibited significant differential expression during tuberization, suggesting their potential roles in regulating the stolon-to-swelling transition. The downregulation of StSRS1 and upregulation of StSRS8 during this critical phase highlight their distinct regulatory functions. These findings are consistent with previous studies implicating SRS genes in plant growth and development, particularly in response to hormonal signals [8, 17, 49].

Transcriptome analysis across four key developmental stages Stolon, Swelling, Initiation, and Tuber revealed dynamic gene expression patterns, highlighting the complexity of tuber development. High-quality sequencing data, with Q30 scores exceeding 97.16% and robust alignment rates to the reference genome, ensured the reliability of our results. Principal component analysis (PCA) and tissue correlation analysis confirmed stage-specific transcriptional signatures, demonstrating the reproducibility of the experimental design and the distinct molecular profiles associated with each developmental phase. These findings align with previous studies emphasizing the importance of transcriptional regulation in tuberization, particularly during the transition from stolon to tuber [14, 25].

Differential expression analysis pinpointed thousands of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) across the developmental stages. Notable changes were detected, with the most substantial variation (6,876 DEGs) occurring in the comparison between Stolon and Tuber. These findings are in line with previous research, emphasizing that the stolon-to-tuber transition phase was completed, subsequent to tuber expansion and maturation [13]. Notably, 174 shared DEGs were identified across all comparisons, suggesting the presence of core regulatory genes that play pivotal roles throughout tuber formation. Transcription factors (TFs) emerged as central regulators of potato tuber development, with differentially expressed transcription factors (DETFs) identified across all pairwise comparisons. Enriching DETFs in pathways related to jasmonic acid, gibberellin, and auxin highlights their critical roles in orchestrating developmental transitions. These results are consistent with prior research highlighting the role of phytohormones in controlling tuber initiation and growth [50, 51]. The predominance of MYB-related, GATA, bHLH, MYB, and AP2 TF families suggests their involvement in key regulatory networks during tuberization. These findings are supported by previous studies demonstrating the importance of TFs in plant development, particularly in response to hormonal cues [17, 25, 52]. Recent studies underscore the importance of m6A RNA modifications in regulating plant development via hormonal pathways [53]. showed that m6A influences transcript stability and translation of key genes involved in auxin and gibberellin signalling hormonal pathways also enriched in our analysis. Similarly [54], highlighted how combined abiotic stress alters hormone-responsive genes through integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic changes. Furthermore, recent advances in agrochemical research, including the synthesis of stable cyclopropane-based compounds that target hormone signalling pathways [55]. Such compounds may be utilized to fine-tune endogenous hormonal signalling, presenting novel opportunities to integrate genetic and chemical approaches for improving tuberization and stress resilience in potato. These findings suggest that m6A-mediated transcriptional regulation adds other layers of control to the phytohormone dynamics and signalling also might involve in tuberization, enhancing our understanding of its regulatory complexity.

Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) revealed stage-specific gene modules associated with tuber development, providing a systems-level understanding of the molecular networks involved. Key modules, such as MEblue (Stolon stage) and MEdarkseagreen4 (Tuber stage), and their associated hub genes, offer valuable insights into the regulatory mechanisms governing tuberization. The strong correlation between gene significance (GS) and module membership (MM) within these modules underscores the robustness of the co-expression networks and the potential functional importance of the identified hub genes. These findings align with previous studies utilizing WGCNA to dissect complex biological processes in plants [15, 56].

Due to limited functional annotation of the candidate hub genes (HGs) and transcription factors (HTFs) in potato, homologous genes were identified in other species to infer putative functions (Table S7). Most homologs from the MEblue module were involved in essential biological processes, including cell elongation, flowering, and hormonal signal transduction. Specifically, the Arabidopsis AtLRP1 gene, the homologous of StSRS8, acts as a crucial role in lateral root development, flower organ morphogenesis via controlling auxin signalling [1, 5]; which implied that StSRS8 might function in tuberization through plant hormone signalling. Additionally, most genes in the MEdarkseagreen4 module were participated into photoperiod, gibberellin signalling, and sugar transporter. It is noteworthy that the tomato SlSRS1 gene, the homologous of StSRS1, shows high transcript accumulation in vegetative organ, and responds to auxin, ABA, as well as abiotic stress such as dehydration [9]; which suggested that StSRS1 might participated in drought repression potato tuberization.

Overall, this study represents a significant advancement in understanding the potential function of StSRS, specifically StSRS1 and StSRS8, in regulation of potato tuber formation. Several limitations should be acknowledged. Moreover, the absence of metabolomic and proteomic data limits comprehensive biological interpretation, highlighting the need for integrative multi-omics approaches in future studies. Additionally, functional validation through experimental approaches, such as CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing or overexpression studies, is necessary to confirm their roles in tuberization [57, 58].

Conclusion

In conclusion, eight StSRS genes were identified in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). A comprehensive analysis was carried out on their phylogenetic relationship, conserved motifs, chromosomal location, and evolutionary relationship. Moreover, by integrating transcriptomic data, Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA), co-expression networks, and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), it was shown that some of these StSRS genes, especially StSRS1 and StSRS8, potentially play crucial roles in regulating the transition from stolon to small tuber. Overall, our findings lay a vital foundation for the subsequent functional exploration of these StSRS genes.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to prof. Botao Song from Huazhong Agricultural University for providing the plant materials “Solanum tuberosum cv. E-potato 3 (E3)”.

Abbreviations

- RNA-seq

RNA-sequencing

- FPKM

Fragments Per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped fragments

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative Real-time PCR

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- GO

Gene Ontology

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- TF

Transcription factor

Authors’ contributions

Y.Y., Y.L.Y., L.Y.Z., Z.J.X., and S.G., writing, original draft, formal analysis, and visualization; S.G., H. G., L.W., and D.Y. L., writing, review and editing, conceptualization, and project administration; X.M.L., and A.S., writing, review and editing and resources; Y.L., and F.M.L., software and visualization; S.G., H. G., L.W., and D.Y. L., writing, review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China(2022YFD1201600, 2022YFD1601404), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (SWU-KR22042, SWU-XDJH202315), Chongqing Technology Innovation and Application Development Program (CSTB2024TIAD-GPX0039, CSTB2022TIAD-CUX0012), Chongqing Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System (CQMAITS202303), the Talent Introduction Program of Southwest University Project (SWU019008), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (32260527).

Data availability

The sequencing data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database under accession number PRJNA1221064, publicly available since February 13, 2025.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article did not contain any studies with human participants or animals and did not involve any endangered or protected species.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yang Yang, Yunling Ye and Shareef Gul contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Hameed Gul, Email: hameed_gul@outlook.com.

Dianqiu Lv, Email: smallpotatoes@126.com.

Lin Wu, Email: wulin2022@swu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Fang D, Zhang W, Ye Z, Hu F, Cheng X, Cao J. The plant specific SHORT INTERNODES/STYLISH (SHI/STY) proteins: structure and functions. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023;194:685–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuusk S, Sohlberg JJ, Magnus Eklund D, Sundberg E. Functionally redundant SHI family genes regulate Arabidopsis gynoecium development in a dose-dependent manner. Plant J. 2006;47(1):99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eklund DM, Ståldal V, Valsecchi I, Cierlik I, Eriksson C, Hiratsu K, Ohme-Takagi M, Sundström JF, Thelander M, Ezcurra I. The Arabidopsis thaliana STYLISH1 protein acts as a transcriptional activator regulating auxin biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 2010;22(2):349–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Showk S, Ruonala R, Helariutta Y. Crossing paths: cytokinin signalling and crosstalk. Development. 2013;140(7):1373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh S, Yadav S, Singh A, Mahima M, Singh A, Gautam V, Sarkar AK. Auxin signaling modulates LATERAL ROOT PRIMORDIUM 1 (LRP 1) expression during lateral root development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2020;101(1):87–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saidi A, Hajibarat Z. Phytohormones: plant switchers in developmental and growth stages in potato. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2021;19(1):89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thelander M, Landberg K, Sundberg E. Auxin-mediated developmental control in the moss physcomitrella patens. J Exp Bot. 2018;69(2):277–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang J, Xu P, Yu D. Genome-wide identification and characterization of the SHI-related sequence gene family in rice. Evolutionary Bioinf. 2020;16:1176934320941495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu W, Wang Y, Shi Y, Liang Q, Lu X, Su D, Xu X, Pirrello J, Gao Y, Huang B. Identification of SRS transcription factor family in solanum lycopersicum, and functional characterization of their responses to hormones and abiotic stresses. BMC Plant Biol. 2023;23(1): 495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andualem M, Tadesse B, Bitew A, Tesfaw A. Analysis of the nutritional and antinutritional contents of tubers of Agew potatoes (Plectranthus edulis) grown in the Awi zone, Amhara regional state of Ethiopia. Food Chemistry Advances. 2024;5: 100829. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devaux A, Goffart J-P, Kromann P, Andrade-Piedra J, Polar V, Hareau G. The potato of the future: opportunities and challenges in sustainable agri-food systems. Potato Res. 2021;64(4):681–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qu L, Huang X, Su X, Zhu G, Zheng L, Lin J, Wang J, Xue H. Potato: from functional genomics to genetic improvement. Mol Hortic. 2024;4(1): 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathura SR, Sutton F, Rouse-Miller J, Bowrin V. The molecular coordination of tuberization: current status and future directions. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2024;82: 102655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shirani-Bidabadi M, Nazarian-Firouzabadi F, Sorkheh K, Ismaili A. Transcriptomic analysis of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tuber development reveals new insights into starch biosynthesis. PLoS One. 2024;19(4): e0297334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Z, Wang J, Wang J. Identification of a comprehensive gene co-expression network associated with autotetraploid potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) development using WGCNA analysis. Genes. 2023;14(6):1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dutt S, Manjul AS, Raigond P, Singh B, Siddappa S, Bhardwaj V, Kawar PG, Patil VU, Kardile HB. Key players associated with tuberization in potato: potential candidates for genetic engineering. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2017;37(7):942–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kondhare KR, Natarajan B, Banerjee AK. Molecular signals that govern tuber development in potato. Int J Dev Biol. 2020;64(1–2–3):133–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang E, Zhou T, Jing S, Dong L, Sun X, Fan Y, Shen Y, Liu T, Song B. Leaves and stolons transcriptomic analysis provide insight into the role of phytochrome F in potato flowering and tuberization. Plant J. 2023;113(2):402–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panahi B, Hamid R, Jalaly HMZ. Deciphering plant transcriptomes: leveraging machine learning for deeper insights. Curr Plant Biol. 2024:100432. 10.1016/j.cpb.2024.100432.

- 20.Shahzad A, Shahzad M, Imran M, Gul H, Gul S. Genome wide identification and expression profiling of PYL genes in barley. Plant Gene. 2023;36: 100434. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agho C, Avni A, Bacu A, Bakery A, Balazadeh S, Baloch FS, Bazakos C, Čereković N, Chaturvedi P, Chauhan H. Integrative approaches to enhance reproductive resilience of crops for climate-proof agriculture. Plant Stress. 2024:100704. 10.1016/j.stress.2024.100704.

- 22.Wang L, Li P, Brutnell TP. Exploring plant transcriptomes using ultra high-throughput sequencing. Brief Funct Genomics. 2010;9(2):118–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agrawal L, Chakraborty S, Jaiswal DK, Gupta S, Datta A, Chakraborty N. Comparative proteomics of tuber induction, development and maturation reveal the complexity of tuberization process in potato (Solanum tuberosum L). J Proteome Res. 2008;7(9):3803–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hannapel DJ, Banerjee AK. Multiple mobile mRNA signals regulate tuber development in potato. Plants. 2017;6(1): 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang M, Jian H, Shang L, Wang K, Wen S, Li Z, Liu R, Jia L, Huang Z, Lyu DJP. Transcriptome analysis reveals novel genes potentially involved in tuberization in potato. Plants. 2024;13(6): 795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang L, Zhang L, Zhang P, Liu J, Li L, Li H, Wang X, Bai Y, Jiang G, Qin P. Comparative transcriptomes and WGCNA reveal hub genes for spike germination in different Quinoa lines. BMC Genomics. 2024;25(1): 1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sánchez-Baizán N, Ribas L, Piferrer F. Improved biomarker discovery through a plot twist in transcriptomic data analysis. BMC Biol. 2022;20(1): 208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hou X, Du Y, Liu X, Zhang H, Liu Y, Yan N, Zhang Z. Genome-wide analysis of long non-coding RNAs in potato and their potential role in tuber sprouting process. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;19(1): 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Gu J. Fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(17):i884-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim D, Langmead B, Hisat SLS. A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements 2015 12. 10.1038/nmeth.3317 3317:357–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Wang Y, Hu H, Li X. RrNAfilter: a fast approach for ribosomal RNA read removal without a reference database. J Comput Biol. 2017;24(4):368–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pertea M, Kim D, Pertea GM, Leek JT, Salzberg SL. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, stringtie and ballgown. Nat Protoc. 2016;11(9):1650–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costa-Silva J, Domingues D, Lopes FM. RNA-seq differential expression analysis: an extended review and a software tool. PLoS One. 2017;12(12): e0190152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu X, Wen S, Gul H, Xu P, Yang Y, Liao X, Ye Y, Xu Z, Zhang X, Wu L. Exploring regulatory network of Icariin synthesis in herba epimedii through integrated omics analysis. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15: 1409601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9(1):559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gul S, Gul H, Shahzad M, Ullah I, Shahzad A, Khan SU. Comprehensive analysis of potato (Solanum tuberosum) PYL genes highlights their role in stress responses. Funct Plant Biol. 2024;51(8):FP24094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cui D, Song Y, Jiang W, Ye H, Wang S, Yuan L, Liu B. Genome-wide characterization of the GRF transcription factors in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) and expression analysis of StGRF genes during potato tuber dormancy and sprouting. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15: 1417204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Susmi FA, Simi TI, Hasan MN, Rahim MA. Genome-wide identification, characterization and functional prediction of the SRS gene family in sesame (Sesamum indicum L). Oil Crop Sci. 2024;9(2):69–80. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan Y, Jiang M, Wang X. Genome-wide identification of carboxyesterase family members reveals the function of GeCXE9 in the catabolism of parishin A in Gastrodia elata. Plant Cell Rep. 2025;44(2): 45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Q, Song Y, Liu K, Su C, Yu R, Li Y, Yang Y, Zhou B, Wang J, Hu G. Genome-wide identification and functional characterization of FAR1-RELATED SEQUENCE (FRS) family members in potato (Solanum tuberosum). Plants. 2023;12(13): 2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liang L, Guo L, Zhai Y, Hou Z, Wu W, Zhang X, Wu Y, Liu X, Guo S, Gao G. Genome-wide characterization of SOS1 gene family in potato (Solanum tuberosum) and expression analyses under salt and hormone stress. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14: 1201730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang X, Zhang N, Si H, Calderón-Urrea A. Selection and validation of reference genes for RT-qPCR analysis in potato under abiotic stress. Plant Methods. 2017;13(1): 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yadav S, Badajena S, Khare P, Sundaresan V, Shanker K, Mani DN, Shukla AK. Transcriptomic insight into zinc dependency of Vindoline accumulation in catharanthus roseus leaves: relevance and potential role of a crzip. Plant Cell Rep. 2025;44(2): 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang R, Sun Y, Zhu X, Jiao B, Sun S, Chen Y, Li L, Wang X, Zeng Q, Liang Q. The tuber-specific StbHLH93 gene regulates proplastid‐to‐amyloplast development during stolon swelling in potato. New Phytol. 2024;241(4):1676–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He B, Shi P, Lv Y, Gao Z, Chen G. Gene coexpression network analysis reveals the role of SRS genes in senescence leaf of maize (Zea mays L). J Genet. 2020;99(1): 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mei C, Liu Y, Dong X, Song Q, Wang H, Shi H, Feng R. Genome-wide identification and characterization of the potato IQD family during development and stress. Front Genet. 2021;12: 693936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Panchy N, Lehti-Shiu M, Shiu S-H. Evolution of gene duplication in plants. Plant Physiol. 2016;171(4):2294–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qiao X, Li Q, Yin H, Qi K, Li L, Wang R, Zhang S, Paterson AH. Gene duplication and evolution in recurring polyploidization–diploidization cycles in plants. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1): 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kloosterman B, Vorst O, Hall RD, Visser RGF, Bachem CW. Tuber on a chip: differential gene expression during potato tuber development. Plant Biotechnol J. 2005;3(5):505–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.He S, Wang H, Hao X, Wu Y, Bian X, Yin M, Zhang Y, Fan W, Dai H, Yuan L. Dynamic network biomarker analysis discovers IbNAC083 in the initiation and regulation of sweet potato root tuberization. Plant J. 2021;108(3):793–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cai Z, Cai Z, Huang J, Wang A, Ntambiyukuri A, Chen B, Zheng G, Li H, Huang Y, Zhan J. Transcriptomic analysis of tuberous root in two sweet potato varieties reveals the important genes and regulatory pathways in tuberous root development. BMC Genomics. 2022;23(1): 473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu Y, Zeng Y, Li Y, Liu Z, Lin-Wang K, Espley RV, Allan AC, Zhang J. Genomic survey and gene expression analysis of the MYB-related transcription factor superfamily in potato (Solanum tuberosum L). Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;164:2450–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shan C, Dong K, Wen D, Cui Z, Cao J. A comprehensive review of m6A modification in plant development and potential quality improvement. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;308:142597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li H, Tang Y, Meng F, Zhou W, Liang W, Yang J, Wang Y, Wang H, Guo J, Yang Q. Transcriptome and metabolite reveal the inhibition induced by combined heat and drought stress on the viability of silk and pollen in summer maize. Ind Crops Prod. 2025;226: 120720. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang X, Tang X, Liao A, Sun W, Lei L, Wu J. Application of Cyclopropane with triangular stable structure in pesticides. J Mol Struct. 2024:141171. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.141171.

- 56.de Silva KK, Dunwell JM, Wickramasuriya AM. Weighted gene correlation network analysis (WGCNA) of Arabidopsis somatic embryogenesis (SE) and identification of key gene modules to uncover SE-Associated hub genes. Int J Genomics. 2022;2022(1):7471063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ahmad D, Zhang Z, Rasheed H, Xu X, Bao J. Recent advances in molecular improvement for potato tuber traits. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(17): 9982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.González MN, Massa GA, Andersson M, Storani L, Olsson N, Décima Oneto CA, Hofvander P, Feingold SE. CRISPR/Cas9 technology for potato functional genomics and breeding. Plant genome engineering: methods and protocols. Springer; 2023. pp. 333–61. 10.1007/978-1-0716-3131-7_21. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The sequencing data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database under accession number PRJNA1221064, publicly available since February 13, 2025.