Abstract

Background

Persistent low fertility in China poses critical socioeconomic challenges. Family functioning has been implicated in reproductive decisionmaking, yet its heterogeneity remain underexplored, particularly among young adults. This study employs Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) to identify high and lowfunctioning family profiles among Chinese university students and their parents, and to quantify their associations with marriageandchildbearing attitudes and explicit fertility intentions.

Methods

In a crosssectional survey of 484 student–parent pairs from two northwest Chinese universities, we administered a 68item questionnaire incorporating the 30item Chinese Family Assessment Device and standardized measures of fertility intentions and marriageandchildbearing views. LPA classified families into two profiles. Multinomial logistic regression (Models 1–3) tested the effect of family functioning on students’ ideal number of children (“0,” “1,” “≥ 2,” vs. “indifferent”), sequentially adjusting for student and parental sociodemographic covariates.

Results

LPA yielded two profiles: lowfunctining (57.0%) and highfunctoning (43.0%) families. In Model 1, lowfunctioning membership increased the odds of intending 0 children (R = 2.90, 95% CI 1.53–5.49, p < 0.01), 1 child (OR = 2.65, 1.51–4.63, p < 0.01), and ≥ 2 children (OR = 3.54, 2.28–5.49, p < 0.001) versus remaining indifferent. Adjusting for student factors (Model 2) attenuated the zerochild effect (p = 0.21) but retained significant associations for 1 child (OR = 2.22, 1.20–4.12, p < 0.05) and ≥ 2 children (OR = 3.08, 1.77–5.35, p < 0.001). In the fully adjusted model (Model 3), lowfunctioning status remained a predictor only of ≥ 2 children (OR = 2.57, 1.40–4.73, p < 0.01). Older parental age independently predicted zerochild intentions (OR = 1.20, 1.08–1.33, p < 0.001), while parental occupation moderated highintention outcomes.

Conclusions

Low family functioning exerts a robust influence on both low and high fertility intentions, although its effect on zerochild plans is largely explained by student and parental characteristics. By uncovering multidimensional familyfunctioning profiles and their differential impacts, this study advances theoretical models of intergenerational value transmission and informs targeted familyeducation and policy interventions aimed at mitigating China’s lowfertility trajectory.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-025-24358-9.

Keywords: Family functioning, Fertility intentions, Latent profile analysis (LPA), University students, Generational differences

Introduction

The population not only underpins social development but also plays a pivotal role in driving sustainable and high-quality economic growth. Over the past three decades, one of the most notable demographic shifts has been the marked decline in global fertility rates, except for a few in impoverished rural areas [1]. A study published in The Lancet projected that by 2100, the global total fertility rate is expected to decline to 1.7, indicating that women, on average, would have only 1.7 children over their reproductive lifespan. This anticipated drop underscores the significant demographic transitions shaping future population structures [2]. The global fertility trend chart depicted in Fig. 1 is constructed on the basis of the fertility rate data provided by the United Nations, Our World In Data, and Statista websites [3–5]. Both scholars and policymakers in China and globally have increasingly concentrated on the challenges posed by declining birth rates and an aging population. Since 2013, China has experienced a rapid decline in its total fertility rate and the proportion of individuals within the working-age demographic. Although the government introduced the three-child policy in 2021, women of reproductive age continue to exhibit low fertility intentions [6–11]. (On May 31, 2021, the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of China Central Committee held a meeting and pointed out that the birth policy should be further optimized, with a policy allowing couples to have three children and supporting measures to be implemented. “Decision on Optimizing the Birth Policy and Promoting Long-term Balanced Population Development” [12]. For more details on the scope and provisions of China’s threechild policy, see the references [13].) Chinese fertility situation has become increasingly severe. Analyses of both period and cohort measures indicate a sustained decline: the period total fertility rate fell below 1.5 in the early 2000 s and the completed cohort fertility rate for women aged 45–49 declined from 5.37 in the 1982 cohort to 1.62 in the 2015 cohort [6]. With this historic change, the fertility rate is likely to continue to decline even after China implemented its universal three-child policy in 2021. Data from the Seventh National Population Census show that the total fertility rate has declined to a low level of 1.3 [6]. From 2021 to 2023, the number of births in China was 10.63 million, 9.56 million, and 9.02 million, respectively. By 2023, China’s total fertility rate had fallen to around 1.0, substantially below the long-established ‘low‐fertility’ benchmark of 1.5 children per woman (Bongaarts & Sobotka, 2012) [14].The persistently low birth rate in China is expected to further reduce its labor supply and accelerate population aging. These demographic challenges have already been identified as significant long-term factors hindering a country’s economic growth and diminishing its developmental momentum [15, 16].

Fig. 1.

Global fertility trends

With respect to their fertility intentions, university students, as a distinct segment of the youth population, exert a substantial influence on actual birth outcomes. Studies conducted among college students in Denmark, South Korea, and Saudi Arabia have demonstrated that while the majority of females are open to parenthood, they generally prefer to delay childbearing [17–19]. Chinese university students, as a unique young demographic, have long been a focus of research due to their reproductive age and the challenges of balancing education, careers, marriage, and childbearing. In China, the proportion of individuals with college-level education increased from 2.8% in 1998 to 24.9% in 2022, highlighting the growing importance of understanding their fertility intentions and influencing factors for the country’s future population structure [20]. More importantly, compared with other groups, university students are in a unique stage of life where they are simultaneously living within their family of origin while also preparing to establish their own new families. During this period, familial influence factors may hold greater research significance in shaping fertility intentions.

A widely used conceptualization of family functioning is provided by Epstein and colleagues in the development of the McMaster Family Assessment Device, which defines healthy family functioning in terms of clear role organization, effective communication patterns, and strong emotional bonds among members [21]. According to Olson’s Circumplex Model, healthy families balance cohesion and flexibility, whereas unbalanced systems exhibit disengagement or enmeshment, rigidity or chaos, all of which shape individual attitudes and intentions [22]. In the demographic literature, fertility intentions are typically conceptualized as the subjective desire or plan to have (an additional) child within a specified time frame [23], and have been shown to reliably predict subsequent fertility behaviors across diverse settings [24]. Internationally, a growing body of work has linked family functioning to fertility outcomes. In Europe, Some studies have found that higher couple-relationship quality and familial cohesion positively correlate with the likelihood of intending and actually having children [25]. In the United States, Guzzo and Hayford used nationally representative survey data to show that young adults embedded in cohesive, communicative family environments express stronger and more stable fertility intentions over time [26]. However, most studies remain descriptive, and the mediating mechanisms—such as how communication patterns or parental role negotiation translate into concrete fertility plans—are underexplored, particularly using person‐centered methods like latent profile analysis. In China, the unique sociocultural context adds layers of complexity [27]. Factors such as the historical impact of the one-child policy, changing gender norms, and evolving economic pressures significantly mediate family dynamics and fertility intentions [28, 29].

This study employs latent profile analysis (LPA) to explore patterns of family functioning among Chinese college students and their links to fertility intentions. Latent profile analysis (LPA) offers unique advantages for studying family functioning variables. To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale investigation to: Identify latent family‐functioning profiles among Chinese university students using Latent Profile Analysis (LPA), rather than assume homogeneity or rely on variable‐centered averages. Link these empirically derived profiles directly to two dimensions of fertility attitudes—the likelihood of marriage and childbearing (Marriage and childbearing view) and explicit fertility intentions (Fertility intentions)—within the same sample. Control for both parental and student sociodemographic factors in a single structural model, thereby isolating the contribution of family functioning patterns above and beyond established predictors. By combining LPA with Analysis of influencing factors, this study not only charts the types of family environments that prevail among contemporary Chinese youth but also quantifies their distinct influences on reproductive decision‐making. Such insights provide actionable guidance for family‐education programs and social‐policy measures aimed at reversing China’s low‐fertility trajectory. LPA identifies representative latent classes on the basis of individuals’ performance across multiple dimensions, effectively reflecting the diversity of family functioning. For example, Li et al. applied a related technique—LCA—to identify pregnancy‐intention subgroups [30]. Similarly, Wang et al. (2023) employed LPA to identify distinct family personality profiles and explored their associations with happiness and health outcomes [31], demonstrating the applicability of LPA in family studies. In the present study LPA is preferable because our family‐functioning scales are continuous and we wish to model their variation within as well as between profiles. Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) and Latent Class Analysis (LCA) are both finite mixture models, but they differ in the nature of their indicators and underlying distributional assumptions [32]. Based on existing data, we understand that LCA is mainly used to model binary or multi-variable categorical observation variables, while LPA is geared toward continuous observation indicators [33, 34]. By estimating profile‐specific means and variances on these continuous indicators, LPA can uncover nuanced subgroups in family functioning that would be obscured by purely categorical methods. So latent profile analysis empirically uncovers distinct family‐functioning subgroups—with minimal measurement error—that differentially predict university students’ fertility intentions, thereby providing actionable insights for tailored policy interventions [35].

This study employs Latent Profile Analysis to classify participating families into high‑ and low‑functioning profiles among Chinese university students and their parents, thereby moving beyond single‑dimension assessments of family environments. We then examine how these empirically derived profiles relate to both marriage‑and‑childbearing attitudes and explicit fertility intentions, while controlling for key student and parental sociodemographic factors. By quantifying the unique contribution of multidimensional family‑functioning patterns to reproductive decision‑making, we not only enrich theoretical models of intergenerational value transmission but also generate actionable guidance for family‑education initiatives and targeted policy interventions to address China’s persistently low fertility.

Materials and methods, subjects

Sample and setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted at two universities—one in Yinchuan and one in Lanzhou—chosen both for our existing institutional partnerships (which streamlined recruitment and data collection) and to ensure coverage of Chinese northwest inland regions; their differing profiles across other project dimensions enabled us to explore potential variations in family‐functioning patterns and fertility intentions. Data collection included face‒to-face surveys with students, followed by the distribution of parental questionnaires through the students, who facilitated completion by their parents. Each student–parent pair constituted a matched unit. In a 2021 survey of Chinese university students, 37% of respondents indicated that they planned to have at least one child within five years after graduation (P = 0.37; Q = 0.63) [36]. On the basis of an epidemiological sample size formula with a 5% margin of error and accounting for a 10% increase in potential nonresponses (N = 400Q/P), the target sample size was calculated to be 750 participants.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) students and their parents from the two universities, (2) the ability to independently read and complete questionnaires, (3) consent to assist with the parental survey, and (4) voluntary participation with informed consent. The exclusion criterion included students residing outside the university (e.g., internship accommodations). During the three-month survey period, 760 student–parent pairs participated, with 484 pairs providing valid responses.

Questionnaire and study variables

The questionnaire covering four domains: personal demographic information, marital and fertility view, family functioning, and fertility intentions. The family function assessment uses the Chinese version of the Family Function Scale, which is a psychometrically validated tool that is highly mature and stable [37, 38]. Marriage and childbearing view draw on the research of Hao et al. (2022) [39]. This variable aims to capture the attachment-based dimension of students’ attitudes toward marriage and childbearing. Remaining personal demographic information items followed conventions in national population studies. For detailed settings for each section of the questionnaire, please refer to the descriptions of each section below. We tested the reliability and validity of the questionnaire, and the results were satisfactory. (Cronbach’s α) = 0.81, KMO = 0.94. All sections were translated, back‑translated, and pretested twice with 30 students to ensure clarity; pilot data were excluded from final analyses. The full questionnaire appears in the Supplementary material.

Sociodemographic variables

Among the participants, university students reported their age, gender, place of birth, academic year, and monthly living expenses. The parents of these students provided information about their age, gender, educational attainment, occupation, and monthly income.

Fertility intention variables

The questionnaire administered to university students included items on their ideal number of children, preferred age for having children, and gender preference for offspring. The questionnaire for the parents of these students included items on their expected number of grandchildren, preferred age for their children to have offspring, and their preferred gender for grandchildren. A widely adopted proxy for fertility intentions in demographic surveys is the “ideal number of children,” elicited by asking respondents how many children they would ideally like to have. This measure has been shown to correlate strongly with subsequent childbearing behaviour and to capture both normative preferences and planned timing of births [24, 40, 41].

Marriage and childbearing view variables

Marriage and fertility view refer to a set of beliefs about processes such as romantic relationships, marriage, and childbirth, which significantly influence individuals’ marital and reproductive practices [39]. In this study, marriage and fertility view are categorized into two types: type of continuum and type of fracture.

The type of continuum refers to an ideal sequence of “romantic relationship–marriage–childbirth,” emphasizing that emotional connection is the most important basis for marriage and childbirth. The type of fracture refers to the view that romantic relationships, marriage, and childbirth can be separate processes, with no inherent connection among them. This view opposes traditional family constraints and supports ideas such as remaining childfree, rejecting marriage, or both. It includes individuals who prefer only romantic relationships without marriage or childbirth or those who marry but do not have children.

Family functioning variables

To better fit the actual situation of Chinese families, we used the revised Chinese version of the Family Assessment Device (FAD) to measure family functioning among college students. The questionnaire includes five dimensions—emotional communication, positive communication, egocentrism, problem solving, and family rules—with a total of 30 items. The emotional communication dimension focuses primarily on the breadth, depth, and methods of emotional exchange among family members. The positive communication dimension reflects constructive communication styles, such as frankness, warmth, and affection among family members. The egocentrism dimension evaluates whether family members prioritize their own interests, including whether family responsibilities are distributed equitably. The problem-solving dimension describes how families handle and resolve issues. The family rules dimension assesses whether effective rules exist to monitor and regulate family members’ behaviors, such as the allocation and fulfillment of household duties [42–44]. The questionnaire uses a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all like my family” to “very much like my family.” Higher scores indicate healthier family functioning. The FAD has been shown to have good reliability and validity among Chinese participants aged 12 years and above [45]. Reliability analysis of the Family Assessment Device (FAD) used in this study yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.861. KMO = 0.93.

To achieve the research objectives of this study—comprehensively uncovering the heterogeneity and diversity of family functioning, exploring the association between family functioning variables and fertility intentions, and reducing the interference of measurement errors to improve the reliability and validity of the research—the family functioning variable in this study was analyzed via latent profile analysis (LPA). Specifically, the family functioning scores of university students and their parents were averaged and subjected to LPA to derive the results.

Data analyses

Data entry and verification were performed via Epdata 3.1 software. Statistical analyses were conducted via SPSS 27.0 and Mplus 8.3 software.

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics were performed via SPSS 27.0 to analyze the fertility intentions of university students and their parents, including the ideal number of children, preferred age for having children, and gender preference for offspring. The samples of college students and their parents were subsequently analyzed via the chi-square test and one-way analysis of variance. Continuous variables are reported as the means and standard deviations (means ± SDs), whereas categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages (n, %).

Latent profile analysis (LPA)

In terms of statistics, latent profile analysis (LPA) is a model-based approach that provides several objective criteria to assess model fit and guide the selection of the final model [35]. Mplus 8.3 software was used to explore the latent profiles of family functioning among the respondents on the basis of the scores from the Chinese version of the Family Assessment Device (FAD). Models with 1 to 5 profiles were estimated, and the model fit evaluation criteria included the following: (1). The Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and adjusted BIC (aBIC)—lower values indicate better model fit. (2). Entropy values closer to 1 indicate higher classification accuracy. (3). LoMendell–Rubin (LMR) adjusted likelihood ratio tests and bootstrap likelihood ratio tests (BLRTs) were used to evaluate differences between the k profile model and the (k-1) profile model. A P value < 0.05 indicates that the k profile model fits the data better [46, 47].

Finally, the optimal number of profiles was determined by comprehensively considering these indices in conjunction with the substantive interpretability of the classifications. Through reviewing the literature, we found that selecting 30 entries for LPA was more suitable for our study in terms of choosing clearer cross-sections and better capturing subtle subgroup structures [34, 48].

Univariate analysis

The univariate analysis employed the x2 test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine the impact of university students’ demographic and sociological variables, their parents’ demographic and sociological variables, their views on marriage and childbirth, and the influencing factors related to family functioning on the fertility intentions of university students.

Model analysis

Multivariate analyses were performed via SPSS 27.0 with multivariate logistic regression models, which were divided into three stages:

Model 1: The dependent variable was university students’ fertility intention (ideal number of children), and the independent variable was the family functioning classification derived from latent profile analysis.

Model 2: Model 1, with the addition of various influencing factors related to university students.

Model 3: Model 2, with the inclusion of various influencing factors related to the parents of university students.

Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P value of less than 0.05. Factors related to university students and their parents that were included in the model analysis were those found to be statistically significant in the univariate analysis.

Subjects

A three-month cross-sectional survey of college students was conducted from April 1 to July 15, 2024, in Gansu Province and Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, China.The study protocol and questionnaire survey were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Ningxia Medical University (Approval Number:2023-057). Before the questionnaires were distributed, an informed consent form was provided to the respondents, which explained the purpose and procedures of the study. The respondents indicated their agreement to participate in the study by selecting the “agree” option before proceeding with the questionnaire. Participation in the study was voluntary, anonymous, and confidential. To maintain anonymity, the participants were instructed not to provide their names. Data collection adhered to the “Code of Conduct for Market Research,” and all collected data were handled in an anonymous and confidential manner.

Results

Descriptive statistics results

The study sample consisted of 484 pairs of university students and their parents. The average expected age for childbirth among university students was 29.15 years (SD = 3.07), whereas their parents’ average was 27.70 years (SD = 2.264). The results were obtained via one-way ANOVA of the sample of college students and their parents (F = 69.715, P < 0.001). Among the university students, the most common ideal number of children was 2 or more (38.2%), while a greater percentage of their parents selected the same option (48.6%). The results were obtained after a chi-square test between the samples of college students and their parents (X2 = 61.282, P < 0.001). Regarding gender preference, 63.2% of the students reported “no preference,” whereas 49.6% of the parents also indicated this choice but at a lower rate, as depicted in Table 1. The results were obtained via a chi-square test between the samples of college students and their parents (X2 = 37.241, P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Fertility intentions of college students and their parents (N = 484)

| College students | n, % | Parents | n, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fertility intention (Number)*** | |||||

| 0 | 54 | 11.2 | 0 | 5 | 1 |

| 1 | 75 | 15.5 | 1 | 39 | 8.1 |

| 2 or more | 185 | 38.2 | 2 or more | 235 | 48.6 |

| Indifferent | 170 | 35.1 | Indifferent | 205 | 42.4 |

| Reproductive sex preference*** | |||||

| Male | 9 | 1.9 | Male | 28 | 5.8 |

| Female | 32 | 6.6 | Female | 14 | 2.9 |

| Both male and female | 137 | 28.3 | Both male and female | 202 | 41.7 |

| No preference | 306 | 63.2 | No preference | 240 | 49.6 |

| Expected reproductive age*** | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||

| 29.15 ± 3.07 | 27.70 ± 2.264 | ||||

(Chi-square p values for samples of college students versus parents, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

Latent profile analysis (LPA) results

Based on the 30-item Chinese Revised Family Assessment Device (FAD), five latent profile analysis (LPA) models were constructed [49], with the fit indices presented in Table 2. AIC, BIC, and aBIC values decreased as the number of profiles increased. For the two-profile solution, both LMRT and BLRT were statistically significant (P < 0.05), and the entropy exceeded the ideal threshold (> 0.8). Considering all fit indices in Table 3, the two-profile model was selected as optimal.

Table 2.

Model fit indices for the latent profile of the Chinese revised FAD scale (N = 484)

| Models | AIC | BIC | aBIC | LMRT | BLRT | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 26879.7 | 27130.63 | 26940.19 | |||

| 2 | 23436.7 | 23817.27 | 23528.45 | 0.0001 | 0 | 0.935 |

| 3 | 21911.49 | 22421.71 | 22034.49 | 0.0002 | 0 | 0.959 |

| 4 | 21147.32 | 21787.18 | 21301.57 | 0.4365 | 0 | 0.965 |

| 5 | 20538.58 | 21308.08 | 20724.08 | 0.549 | 0 | 0.961 |

AIC, Akaike information criterion; BIC, Bayesian information criterion; aBIC, adjusted BIC; LMR, LoMendell-Rubin; BLRT, bootstrap likelihood ratio test

Table 3.

Fit indices

| Four-class fit indices | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.975 | 0.025 |

| 2 | 0.013 | 0.987 |

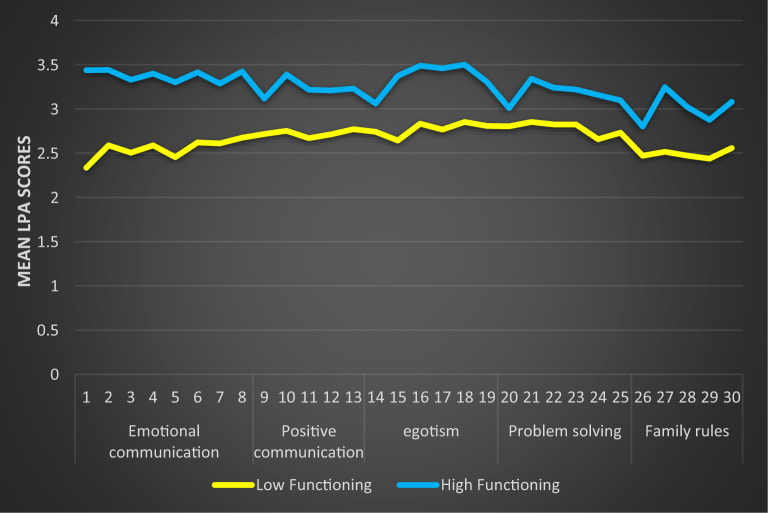

In this model, respondents were categorized into two profiles on the basis of their scores across five dimensions. Specifically, 57.03% were classified as low functioning (Profile 1), and 42.98% were classified as high functioning (Profile 2), as shown in Table 4. The average values of the explicit indicators were used to construct latent profiles, depicted in Fig. 2.

Table 4.

LPA FAD scores of the four profiles

| FAD dimensions | Items | Family functioning categories | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Functioning | High Functioning | ||

| Emotional communication | 1 | 2.341 | 3.444 |

| 2 | 2.594 | 3.447 | |

| 3 | 2.51 | 3.336 | |

| 4 | 2.593 | 3.406 | |

| 5 | 2.461 | 3.307 | |

| 6 | 2.626 | 3.42 | |

| 7 | 2.616 | 3.292 | |

| 8 | 2.68 | 3.43 | |

| Positive communication | 9 | 2.723 | 3.122 |

| 10 | 2.758 | 3.395 | |

| 11 | 2.675 | 3.223 | |

| 12 | 2.718 | 3.215 | |

| 13 | 2.777 | 3.236 | |

| Egotism | 14 | 2.747 | 3.067 |

| 15 | 2.649 | 3.379 | |

| 16 | 2.838 | 3.495 | |

| 17 | 2.772 | 3.465 | |

| 18 | 2.858 | 3.507 | |

| 19 | 2.813 | 3.312 | |

| Problem solving | 20 | 2.81 | 3.015 |

| 21 | 2.858 | 3.347 | |

| 22 | 2.831 | 3.246 | |

| 23 | 2.83 | 3.225 | |

| 24 | 2.663 | 3.163 | |

| 25 | 2.737 | 3.103 | |

| Family rules | 26 | 2.477 | 2.807 |

| 27 | 2.521 | 3.251 | |

| 28 | 2.478 | 3.028 | |

| 29 | 2.443 | 2.882 | |

| 30 | 2.563 | 3.086 | |

Fig. 2.

Latent profiles based on the 30 items of the FAD

Univariate analysis results

Univariate analysis revealed significant differences among university students’ characteristics, including age, expected age at childbirth, gender, household registration (hukou), gender preference for offspring, academic year, and monthly living expenses. Similarly, among parental characteristics, significant differences were observed in terms of age, expected age for childbirth, educational level, occupation, marital and fertility view, and gender preference for offspring. Additionally, the two-class latent profile model of family functioning showed statistically significant differences, as indicated in Table 5.

Table 5.

χ2 test and ANOVA results (N = 484)

| Factors of college students | Fertility intention | X2/F | P | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 or more | Indifferent | |||||||

| Age | 20.0 ± 1.5 | 21.1 ± 2.2 | 21.0 ± 2.2 | 20.6 ± 1.8 | 5.442 | 0.001 | ||||

| Expected reproductive age | 30.9 ± 3.5 | 29.5 ± 4.7 | 28.4 ± 2.3 | 29.3 ± 2.4 | 10.487 | <0.001 | ||||

| Gender | 14.175 | 0.003 | ||||||||

| Male | 10 | 5.60% | 22 | 12.30% | 82 | 45.80% | 65 | 36.30% | ||

| Female | 44 | 14.40% | 53 | 17.40% | 103 | 33.80% | 105 | 34.40% | ||

| Household registration | 11.832 | 0.008 | ||||||||

| Urban | 31 | 14.20% | 38 | 17.40% | 66 | 30.30% | 83 | 38.10% | ||

| Rural | 23 | 8.60% | 37 | 13.90% | 119 | 44.70% | 87 | 32.70% | ||

| Reproductive sex preference | 170.898 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Male | 2 | 22.20% | 4 | 44.40% | 2 | 22.20% | 1 | 11.10% | ||

| Female | 5 | 15.60% | 11 | 34.40% | 12 | 37.50% | 4 | 12.50% | ||

| Both male and female | 3 | 2.20% | 7 | 5.10% | 110 | 80.30% | 17 | 12.40% | ||

| No preference | 44 | 14.40% | 53 | 17.30% | 61 | 19.90% | 148 | 48.40% | ||

| Grade level | 33.14 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Freshman | 39 | 19.10% | 29 | 14.20% | 86 | 42.20% | 50 | 24.50% | ||

| Sophomore and above | 15 | 5.40% | 46 | 16.40% | 99 | 35.40% | 120 | 42.90% | ||

| Marriage and childbearing view | 4.215 | 0.239 | ||||||||

| Type of continuum | 2 | 3.40% | 11 | 19.00% | 24 | 41.40% | 21 | 36.20% | ||

| Type of fracture | 52 | 12.20% | 64 | 15.00% | 161 | 37.80% | 149 | 35.00% | ||

| College student living expenses | 31.637 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| < 1000¥ | 5 | 7.20% | 6 | 8.70% | 44 | 63.80% | 14 | 20.30% | ||

| 1000–2000 ¥ | 40 | 10.50% | 65 | 17.10% | 135 | 35.50% | 140 | 36.80% | ||

| > 2000¥ | 9 | 25.70% | 4 | 11.40% | 6 | 17.10% | 16 | 45.70% | ||

| Parental factors | ||||||||||

| Age | 48.54 ± 4.63 | 48.5 ± 4.6 | 48.4 ± 4.0 | 47.1 ± 3.8 | 3.85 | 0.01 | ||||

| Expected reproductive age | 27.5 ± 2.1 | 27.8 ± 2.2 | 27.3 ± 2.1 | 28.1 ± 2.5 | 3.962 | 0.008 | ||||

| Gender | 5.297 | 0.151 | ||||||||

| Male | 28 | 12.40% | 26 | 11.60% | 88 | 39.10% | 83 | 36.90% | ||

| Female | 26 | 10.00% | 49 | 18.90% | 97 | 37.50% | 87 | 33.60% | ||

| Level of education | 20.424 | 0.015 | ||||||||

| Primary school and below | 9 | 7.00% | 24 | 18.80% | 61 | 47.70% | 34 | 26.60% | ||

| Junior high school | 16 | 9.00% | 24 | 13.50% | 60 | 33.70% | 78 | 43.80% | ||

| High school or technical school | 12 | 14.50% | 11 | 13.30% | 31 | 37.30% | 29 | 34.90% | ||

| Bachelor degree or above | 17 | 17.90% | 16 | 16.80% | 33 | 34.70% | 29 | 30.50% | ||

| Career | 42.542 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Farmer | 14 | 8.90% | 22 | 13.90% | 76 | 48.10% | 46 | 29.10% | ||

| Worker | 11 | 11.20% | 14 | 14.30% | 28 | 28.60% | 45 | 45.90% | ||

| Within the government system | 8 | 12.50% | 15 | 23.40% | 25 | 39.10% | 16 | 25.00% | ||

| Businessman or private industry | 9 | 10.70% | 10 | 11.90% | 18 | 21.40% | 47 | 56.00% | ||

| Service industry and others | 12 | 15.00% | 14 | 17.50% | 38 | 47.50% | 16 | 20.00% | ||

| Monthly income | 9.362 | 0.405 | ||||||||

| < 2000¥ | 10 | 11.60% | 15 | 17.40% | 40 | 46.50% | 21 | 24.40% | ||

| 2000ཞ5000¥ | 23 | 11.40% | 32 | 15.80% | 72 | 35.60% | 75 | 37.10% | ||

| 5000ཞ10000¥ | 18 | 10.50% | 25 | 14.60% | 60 | 35.10% | 68 | 39.80% | ||

| >10,000¥ | 3 | 12.00% | 3 | 12.00% | 13 | 52.00% | 6 | 24.00% | ||

| Marriage and childbearing view | 7.975 | 0.047 | ||||||||

| Type of continuum | 21 | 8.20% | 34 | 13.30% | 104 | 40.60% | 97 | 37.90% | ||

| Type of fracture | 33 | 14.50% | 41 | 18.00% | 81 | 35.50% | 73 | 32.00% | ||

| Reproductive sex preference | 76.231 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Male | 6 | 21.40% | 7 | 25.00% | 11 | 39.30% | 4 | 14.30% | ||

| Female | 4 | 28.60% | 4 | 28.60% | 5 | 35.70% | 1 | 7.10% | ||

| Both male and female | 17 | 8.40% | 23 | 11.40% | 115 | 56.90% | 47 | 23.30% | ||

| No preference | 27 | 11.30% | 41 | 17.10% | 54 | 22.50% | 118 | 49.20% | ||

| Fertility intention (Number) | 3.453 | 0.063 | ||||||||

| 0 | 3 | 60.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 2 | 40.00% | 0 | 0.00% | ||

| 1 | 4 | 10.30% | 22 | 56.40% | 8 | 20.50% | 5 | 12.80% | ||

| 2 or more | 25 | 10.60% | 27 | 11.50% | 138 | 58.70% | 45 | 19.10% | ||

| Indifferent | 22 | 10.70% | 26 | 12.70% | 37 | 18.00% | 120 | 58.50% | ||

| Family functioning | ||||||||||

| Two classification of LPA | 36.463 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Low Functioning | 35 | 12.70% | 47 | 17.00% | 128 | 46.40% | 66 | 23.90% | ||

| High Functioning | 19 | 9.10% | 28 | 13.50% | 57 | 27.40% | 104 | 50.00% | ||

Model analysis results

Multinomial logistic regression results are summarized in Table 6. Using students who reported being “indifferent” about their ideal number of children as the reference category, three sequential models were fitted. Model 1 (family functioning only) revealed that membership in the low‑functioning profile was associated with significantly higher odds of expressing a clear fertility intention of zero children (B = 1.066, OR = 2.90, 95% CI 1.53–5.49, p < 0.01), one child (B = 0.973, OR = 2.65, 1.51–4.63, p < 0.01) or two or more children (B = 1.264, OR = 3.54, 2.28–5.49, p < 0.001) compared with remaining “indifferent”. Model 2, which added student sociodemographic covariates, attenuated the association between family functioning and the zero‑child outcome to non‑significance (p = 0.21) but retained significant effects for one child (B = 0.798, OR = 2.22, 1.20–4.12, p < 0.05) and ≥ 2 children (B = 1.125, OR = 3.08, 1.77–5.35, p < 0.001). Among student characteristics, each additional year in expected age at first birth increased the odds of zero‑child intention (B = 0.120, OR = 1.13, 1.02–1.25, p < 0.05). Males were less likely than females to intend zero children (B = − 1.069, OR = 0.34, 0.15–0.80, p < 0.05). Freshmen exhibited substantially higher odds of zero‑child intention (B = 2.145, OR = 8.54, 2.97–24.55, p < 0.001) and ≥ 2 children (B = 0.905, OR = 2.47, 1.24–4.94, p < 0.05). Preferences for a son or daughter also strongly predicted non‑“indifferent” intentions (e.g., preferring a boy: OR = 14.04, 1.08–182.43; preferring a girl: OR_1 = 8.19, 2.35–28.49; OR_≥2 = 6.85, 2.00–23.43; all p < 0.05). Model 3 incorporated parental factors in addition to student covariates. Family functioning remained non‑significant for zero‑ and one‑child outcomes (p > 0.10) but continued to predict intentions of two or more children (B = 0.944, OR = 2.57, 1.40–4.73, p < 0.01). Older parental age elevated the odds of zero‑child intention (B = 0.181, OR = 1.20, 1.08–1.33, p < 0.001). Relative to service‑industry parents, those employed as farmers (B = − 1.254, OR = 0.29, 0.12–0.71, p < 0.01), workers (B = − 1.562, OR = 0.21, 0.08–0.55, p < 0.01) or private-sector employees (B = − 1.436, OR = 0.24, 0.09–0.66, p < 0.01) were less likely to have intentions of two or more children. Taken together, these models indicate that while low family functioning is initially associated with both low and high fertility intentions, its effect is largely explained by student and parental characteristics, which themselves exert independent influences on fertility planning. as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Model analysis results

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family functioning variables | Family functioning variables, College student factors | Family functioning variables, College student factors, Parental factors | ||||||||||

| B | OR | 95%CI | B | OR | 95%CI | B | OR | 95%CI | ||||

| Fertility intention (Number)−0 | ||||||||||||

| Family factors | ||||||||||||

| Family functioning | ||||||||||||

| Low Functioning | 1.066** | 2.903 | 1.534 | 5.494 | 0.615 | 1.85 | 0.889 | 3.85 | 0.142 | 1.153 | 0.514 | 2.585 |

| High Functioning (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| N | 484 | |||||||||||

| R 2 | 0.079 | |||||||||||

| Factors of college students | ||||||||||||

| Age | 0.177 | 1.194 | 0.9 | 1.584 | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.715 | 1.372 | ||||

| Expected reproductive age | 0.12* | 1.128 | 1.019 | 1.248 | 0.166** | 1.18 | 1.044 | 1.334 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | −1.069* | 0.343 | 0.147 | 0.802 | −1.155* | 0.315 | 0.123 | 0.807 | ||||

| Female (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| Household registration | ||||||||||||

| Urban | 0.126 | 1.134 | 0.557 | 2.308 | −0.382 | 0.683 | 0.269 | 1.73 | ||||

| Rural (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| Grade level | ||||||||||||

| Freshman | 2.145*** | 8.538 | 2.969 | 24.551 | 2.336*** | 10.345 | 3.197 | 33.47 | ||||

| Sophomore and above (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| College student living expenses | ||||||||||||

| < 1000¥ | −0.915 | 0.401 | 0.086 | 1.862 | −0.411 | 0.663 | 0.121 | 3.625 | ||||

| 1000–2000 ¥ | −0.795 | 0.451 | 0.16 | 1.273 | −0.504 | 0.604 | 0.188 | 1.94 | ||||

| > 2000¥(Reference) | ||||||||||||

| Reproductive sex preference | ||||||||||||

| Male | 2.642* | 14.038 | 1.08 | 182.433 | 2.761* | 15.809 | 1.08 | 231.447 | ||||

| Female | 1.412 | 4.103 | 0.957 | 17.586 | 1.144 | 3.139 | 0.635 | 15.524 | ||||

| Both male and female | −0.215 | 0.807 | 0.81 | 3.101 | −0.539 | 0.583 | 0.137 | 2.492 | ||||

| No preference (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| N | 484 | |||||||||||

| R 2 | 0.469 | |||||||||||

| Parental factors | ||||||||||||

| Age | 0.181*** | 1.199 | 1.083 | 1.327 | ||||||||

| Expected reproductive age | −0.148 | 0.863 | 0.724 | 1.028 | ||||||||

| Career | ||||||||||||

| Farmer | −0.682 | 0.506 | 0.148 | 1.733 | ||||||||

| Worker | −0.266 | 0.767 | 0.22 | 2.676 | ||||||||

| Within the government system | −0.75 | 0.472 | 0.115 | 1.947 | ||||||||

| Businessman or private industry | −0.507 | 0.602 | 0.163 | 2.219 | ||||||||

| Service industry and others (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| Level of education | ||||||||||||

| Primary school and below | −1.013 | 0.363 | 0.088 | 1.504 | ||||||||

| Junior high school | −0.51 | 0.6 | 0.184 | 1.955 | ||||||||

| High school or technical school | 0.038 | 1.039 | 0.335 | 3.222 | ||||||||

| Bachelor degree or above (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| Marriage and childbearing view | ||||||||||||

| Type of continuum | −0.688 | 0.502 | 0.224 | 1.126 | ||||||||

| Type of fracture (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| Reproductive sex preference | ||||||||||||

| Male | 1.529 | 4.616 | 0.892 | 23.874 | ||||||||

| Female | 1.539 | 4.659 | 0.369 | 58.834 | ||||||||

| Both male and female | 0.449 | 1.566 | 0.644 | 3.809 | ||||||||

| No preference (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| N | 484 | |||||||||||

| R 2 | 0.544 | |||||||||||

| Fertility intentio (Number)−1 | ||||||||||||

| Family factors | ||||||||||||

| Family functioning | ||||||||||||

| Low Functioning | 0.973** | 2.645 | 1.51 | 4.633 | 0.798* | 2.222 | 1.198 | 4.12 | 0.598 | 1.819 | 0.91 | 3.636 |

| High Functioning (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| N | 484 | |||||||||||

| R 2 | 0.079 | |||||||||||

| Factors of college students | ||||||||||||

| Age | 0.243* | 1.275 | 1.049 | 1.549 | 0.151 | 1.163 | 0.929 | 1.458 | ||||

| Expected reproductive age | 0.032 | 1.033 | 0.934 | 1.142 | 0.033 | 1.034 | 0.923 | 1.158 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | −0.48 | 0.619 | 0.327 | 1.171 | −0.472 | 0.624 | 0.319 | 1.221 | ||||

| Female (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| Household registration | ||||||||||||

| Urban | 0.063 | 1.066 | 0.586 | 1.937 | −0.222 | 0.801 | 0.383 | 1.673 | ||||

| Rural (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| Grade level | ||||||||||||

| Freshman | 0.778 | 2.178 | 0.983 | 4.826 | 0.52 | 1.683 | 0.715 | 3.961 | ||||

| Sophomore and above (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| College student living expenses | ||||||||||||

| < 1000¥ | 0.016 | 1.016 | 0.205 | 5.044 | 0.051 | 1.052 | 0.185 | 5.99 | ||||

| 1000–2000 ¥ | 0.719 | 2.053 | 0.603 | 6.99 | 0.965 | 2.625 | 0.724 | 9.517 | ||||

| > 2000¥(Reference) | ||||||||||||

| Reproductive sex preference | ||||||||||||

| Male | 2.66* | 14.29 | 1.488 | 137.225 | 2.61* | 13.593 | 1.284 | 143.943 | ||||

| Female | 2.103** | 8.19 | 2.354 | 28.493 | 2.057* | 7.826 | 2.073 | 29.545 | ||||

| Both male and female | 0.269 | 1.309 | 0.491 | 3.49 | 0.243 | 1.275 | 0.453 | 3.593 | ||||

| No preference (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| N | 484 | |||||||||||

| R 2 | 0.469 | |||||||||||

| Parental factors | ||||||||||||

| Age | 0.087* | 1.09 | 1.002 | 1.187 | ||||||||

| Expected reproductive age | 0.012 | 1.012 | 0.874 | 1.171 | ||||||||

| Career | ||||||||||||

| Farmer | −1.019 | 0.361 | 0.129 | 1.007 | ||||||||

| Worker | −1.2* | 0.301 | 0.102 | 0.892 | ||||||||

| Within the government system | 0.495 | 1.641 | 0.453 | 5.943 | ||||||||

| Businessman or private industry | −0.898 | 0.407 | 0.132 | 1.257 | ||||||||

| Service industry and others (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| Level of education | ||||||||||||

| Primary school and below | 1.022 | 2.779 | 0.832 | 9.283 | ||||||||

| Junior high school | 0.526 | 1.692 | 0.559 | 5.124 | ||||||||

| High school or technical school | 0.079 | 1.083 | 0.358 | 3.271 | ||||||||

| Bachelor degree or above (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| Marriage and childbearing view | ||||||||||||

| Type of continuum | −0.552 | 0.576 | 0.298 | 1.112 | ||||||||

| Type of fracture (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| Reproductive sex preference | ||||||||||||

| Male | 1.058 | 2.881 | 0.641 | 12.944 | ||||||||

| Female | 1.657 | 5.244 | 0.468 | 58.765 | ||||||||

| Both male and female | −0.118 | 0.889 | 0.414 | 1.909 | ||||||||

| No preference (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| N | 484 | |||||||||||

| R 2 | 0.544 | |||||||||||

| Fertility intentio (Number)−2or more | ||||||||||||

| Family factors | ||||||||||||

| Family functioning | ||||||||||||

| Low Functioning | 1.264*** | 3.539 | 2.282 | 5.488 | 1.125*** | 3.08 | 1.773 | 5.352 | 0.944** | 2.569 | 1.395 | 4.73 |

| High Functioning (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| N | 484 | |||||||||||

| R 2 | 0.079 | |||||||||||

| Factors of college students | ||||||||||||

| Age | 0.169 | 1.184 | 0.995 | 1.41 | 0.075 | 1.078 | 0.885 | 1.313 | ||||

| Expected reproductive age | −0.088 | 0.916 | 0.828 | 1.013 | −0.09 | 0.914 | 0.817 | 1.023 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | 0.082 | 1.085 | 0.636 | 1.854 | 0.122 | 1.129 | 0.64 | 1.994 | ||||

| Female (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| Household registration | ||||||||||||

| Urban | < 0.001 | 1 | 0.586 | 1.705 | −0.218 | 0.804 | 0.412 | 1.572 | ||||

| Rural (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| Grade level | ||||||||||||

| Freshman | 0.905* | 2.471 | 1.235 | 4.942 | 0.599 | 1.82 | 0.864 | 3.838 | ||||

| Sophomore and above (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| College student living expenses | ||||||||||||

| < 1000¥ | ||||||||||||

| 1000–2000 ¥ | 0.959 | 2.61 | 0.664 | 10.253 | 0.958 | 2.605 | 0.608 | 11.17 | ||||

| > 2000¥(Reference) | 0.914 | 2.494 | 0.773 | 8.043 | 0.921 | 2.513 | 0.732 | 8.624 | ||||

| Reproductive sex preference | ||||||||||||

| Male | 1.502 | 4.489 | 0.377 | 53.423 | 1.555 | 4.735 | 0.353 | 63.581 | ||||

| Female | 1.924** | 6.852 | 2.004 | 23.426 | 1.907** | 6.73 | 1.875 | 24.161 | ||||

| Both male and female | 2.629*** | 13.855 | 7.245 | 26.498 | 2.558*** | 12.915 | 6.389 | 26.109 | ||||

| No preference (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| N | 484 | |||||||||||

| R 2 | 0.469 | |||||||||||

| Parental factors | ||||||||||||

| Age | 0.065 | 1.067 | 0.99 | 1.15 | ||||||||

| Expected reproductive age | 0.072 | 1.074 | 0.938 | 1.23 | ||||||||

| Career | ||||||||||||

| Farmer | −1.254** | 0.285 | 0.115 | 0.71 | ||||||||

| Worker | −1.562** | 0.21 | 0.081 | 0.545 | ||||||||

| Within the government system | −0.514 | 0.598 | 0.19 | 1.882 | ||||||||

| Businessman or private industry | −1.436** | 0.238 | 0.086 | 0.655 | ||||||||

| Service industry and others (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| Level of education | ||||||||||||

| Primary school and below | 0.041 | 1.042 | 0.364 | 2.98 | ||||||||

| Junior high school | −0.185 | 0.831 | 0.321 | 2.156 | ||||||||

| High school or technical school | −0.212 | 0.809 | 0.308 | 2.123 | ||||||||

| Bachelor degree or above (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| Marriage and childbearing view | ||||||||||||

| Type of continuum | −0.16 | 0.852 | 0.48 | 1.512 | ||||||||

| Type of fracture (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| Reproductive sex preference | ||||||||||||

| Male | 0.572 | 1.773 | 0.433 | 7.254 | ||||||||

| Female | 1.284 | 3.61 | 0.32 | 40.675 | ||||||||

| Both male and female | 0.411 | 1.508 | 0.789 | 2.885 | ||||||||

| No preference (Reference) | ||||||||||||

| N | 484 | |||||||||||

| R 2 | 0.544 | |||||||||||

(*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001)

Discussion

This work extends prior research in three key ways. Whereas most studies have examined family functioning and fertility intentions separately or descriptively, our person‑centered LPA approach uncovers naturally occurring subgroups of family environments and directly quantifies their differential associations with both marriage‑and‑childbearing attitudes and explicit fertility intentions. By integrating parental and student sociodemographic controls, we demonstrate that these family‑functioning profiles retain a distinct predictive effect even after accounting for age, gender preferences, and parental characteristics. Finally, by examining low‑, medium‑, and high‑functioning families in parallel across three analytic models, we reveal that family functioning exerts a stable influence on low fecundity intentions but a more pronounced effect on high fertility aspirations, highlighting pathway‑specific mechanisms—such as emotional support versus normative pressure—that can inform more nuanced policy responses. First the results demonstrate that compared with students from high-functioning families, those from low-functioning families are significantly more likely to express fertility intentions of “zero,” “one,” or “two or more” children compared with remaining “indifferent”. This finding corroborates the findings of previous studies, which indicate that family functioning plays a pivotal role in shaping fertility intentions, especially through its impact on emotional and structural support systems in fertility decision-making [50]. Families with limited functionality often lack adequate emotional and logistical support, which may exacerbate stress or uncertainty related to childbearing [50]. The family system plays an essential role in shaping individuals’ fertility intentions by indirectly influencing their values, social norms, and expectations regarding family life [51].

This study also revealed that, compared with high-functioning families, family functioning in low-functioning families significantly impacts university students’ fertility intentions, with the magnitude of this effect varying on the basis of different fertility intentions. The influence of family functioning type is relatively stable for low fertility intentions (0 and 1 child) but becomes more pronounced for high fertility intentions (2 or more children). This may suggest that the effect of family functioning type is less significant for students with low fertility intentions, possibly because other factors, such as individual independence or career planning, play a more dominant role in this group. The significant impact of family functioning type on high fertility intentions may stem from the transmission of traditional family values or the imposition of familial pressure, such as parental expectations regarding the number of children. Some studies have shown that family dynamics significantly influence individuals’ fertility choices. For example, studies have revealed an association between effective family communication and greater fertility intentions among women [52]. Effective family communication helps alleviate stress and enhance subjective well-being, thereby strengthening women’s fertility intentions. Support and understanding among family members are particularly crucial for women when making fertility-related decisions [53].

In response, diversified fertility education and support measures should be provided for students from different family backgrounds to help them form more rational and realistic fertility decisions aligned with their actual circumstances. Enhancing family communication and emotional support through counseling and education programs can improve family dynamics, particularly for low-functioning families. Providing reproductive education and tailored support services, such as financial aid and childcare resources, can alleviate external pressures and help individuals make autonomous fertility decisions. Additionally, efforts to challenge traditional family expectations and promote equitable family roles are crucial to mitigating the impact of parental pressures and gendered responsibilities on fertility choices. By fostering both supportive family environments and broader societal resources, these measures aim to empower young individuals to pursue their fertility preferences while reducing the constraints imposed by dysfunctional family systems.

After incorporating relevant influencing factors among university students, it was found that students with a higher expected age of childbirth were more likely to have a fertility intention of zero. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies, which suggest that prioritizing career or educational goals often leads individuals to delay childbirth, accompanied by lower fertility intentions. Studies have shown that delayed childbirth is typically associated with higher opportunity costs and lifestyle adjustments, both of which may influence fertility decisions [52].

In terms of gender differences among university students, male respondents were less likely than female respondents were to choose a fertility intention of zero. This reflects findings that men in traditional societies tend to bear less responsibility for childcare, which results in lower resistance to fertility intentions. Expectations of gender roles often play a significant part in these views, with women typically anticipated to shoulder greater responsibilities associated with childbearing, including physical, emotional, and financial burdens [54].

With respect to the grade level of university students, first-year students were more likely than students in other grades to express zero fertility intentions. Students who have just completed high school and are in the early stages of their university education often prioritize academic goals, perceiving childbearing as incompatible with academic progress. This can be attributed to the intense pressure of high school education and the fierce competition of the college entrance examination in China. After spending some time at university, students tend to gradually shift their attention from academics to life and begin to consider fertility-related issues. This finding aligns with previous research on university students’ fertility intentions conducted in China, which indicated that young adults in academic environments often exhibit lower fertility intentions [52].

With respect to gender preferences in terms of fertility among university students, respondents with a preference for female offspring or a balanced gender composition were significantly more likely to express a fertility intention of “2 or more” than those with no gender preference. However, respondents with a preference for male offspring were significantly more likely to express a fertility intention of “1” than those without a gender preference. This finding may indicate that, in the context of low fertility rates in China, gender preference has a significant effect on fertility intentions. These findings are consistent with prior research, which suggests that traditional cultural norms—particularly in China—exert a strong influence on gender-based fertility preferences, reinforcing the desire for a “balanced” family composition [55]. At the same time, this may also suggest that the gender preferences of today’s university students are shifting compared with those of previous generations. More importantly, in the context of low fertility rates in China, respondents with a preference for female offspring or a balanced gender composition exhibit stronger fertility intentions, whereas those with a preference for male offspring display lower fertility intentions. This contrasts with prior research conducted in developed countries such as Finland and Italy [56, 57], as well as in developing countries such as Nepal, Malawi, and Iran [58–61]. Most notably, this study also differs from earlier studies conducted within China [62]. Notably, the results of the descriptive analysis reveal significant differences between the surveyed university students and their parents in terms of the average desired childbearing age, ideal number of children, and gender preferences. These intergenerational differences in frtility may reflect generational shifts in reproductive behaviors in China. The younger generation tends to delay childbirth due to economic pressures and personal development goals, aligning with the contemporary trend of delayed fertility in China [55, 63]. In contrast, the older generation exhibits a preference for earlier childbearing, influenced by historical policies [64]. Differences in fertility intentions between university students and their parents may be attributed to shifts in social norms, economic pressures, and changes in government policies. While the older generation may continue to adhere to traditional views on family size, the younger generation is increasingly influenced by factors such as economic insecurity, career aspirations, and evolving gender roles [65, 66]. With increasing equality in gender roles, young women’s fertility intentions are increasingly shaped by career aspirations and societal values rather than traditional preferences for male offspring [52]. However, despite the growing trend toward gender neutrality, the preference for sons persists in certain rural areas and among older generations, highlighting the enduring influence of Confucian culture on fertility decision-making [67]. These findings highlight the unique characteristics of contemporary Chinese society and the new generation of individuals of reproductive age. China’s society and social attitudes are evolving rapidly, and it is essential to approach current fertility issues in China with a forward-looking view rather than directly applying outdated viewpoints or those derived from other countries. Universities could integrate career planning and fertility education into their curricula, offering workshops and counseling services that emphasize the interplay between professional growth and reproductive decision-making. Such initiatives can help students navigate the challenges of aligning long-term career aspirations with family planning. For first-year students, who often prioritize academic success due to the intense pressure of transitioning from high school to university, tailored mental health support and resources promoting life planning are particularly beneficial. Promoting gender equality remains pivotal; policy interventions should encourage the equitable distribution of childcare responsibilities, such as incentivizing male participation in parenting, to reduce the disproportionate burden on women. To address persistent gender preferences, public education campaigns are essential for challenging deep-rooted cultural biases that favor male offspring while fostering inclusive and balanced family models. Recognizing generational shifts in fertility behavior, the economic pressures faced by younger generations warrant comprehensive support, including affordable housing, extended parental leave, and financial subsidies for early childbearing. Additionally, outreach programs targeting rural areas and older demographics could facilitate acceptance of evolving fertility attitudes, mitigating traditional expectations that place undue stress on younger individuals. Given the complex role of gender preferences in the context of low fertility in China, further cross-cultural research is vital to understanding these dynamics and their implications for policy. By aligning education, gender equity, and economic support strategies, these measures not only enhance fertility intentions among students but also address broader demographic challenges in China, offering a sustainable framework for future population policies.

After incorporating factors related to university students’ parents, it was found that students with older parents are more likely to express zero fertility intentions. This finding aligns with studies indicating that parental characteristics and gender preference norms strongly influence fertility behaviors. Traditional cultural pressures, such as the emphasis on male heirs, may contribute to hesitations in fertility planning, particularly within the context of a modern economy [68].

Additionally, the presence of older parents among university students may suggest that their parents had children at a later age. Research has demonstrated a significant correlation between parents’ fertility patterns and those of their children, with this association strengthening over time [69].

With respect to the occupations of university students’ parents, those whose parents are engaged in manual labor (farmers or workers) report lower fertility intentions for having two or more children than do those whose parents work in the service sector or other industries. This result reflects the impact of parental occupation on children’s fertility intentions, as economic and cultural resources associated with occupational status significantly influence fertility decisions. Parents with lower socioeconomic stability—commonly observed in physical labor occupations such as farming and manual work—may unintentionally constrain their children’s fertility planning choices because of reduced economic or social support [70, 71]. A study published in Frontiers in Sociology (2021) [72] highlights how parental involvement and occupational roles mediate fertility intentions by shaping perceptions of feasibility and readiness for family planning [72]. This finding underscores the complex interplay between family socioeconomic factors and cultural expectations in fertility planning, suggesting that fertility-oriented policies should address parental occupations and their indirect effects on younger generations. Additionally, this finding may indicate that the balance between parental work and family responsibilities has a significant influence on the fertility intentions and behaviors of reproductive-age individuals. The conflict between work pressures and family responsibilities among parents may reduce fertility intentions, while effective balancing mechanisms can help increase them. Employment conditions and the ability to balance work and family life also affect fertility intentions. Research has shown that flexible work arrangements can enhance individual fertility intentions [73]. This study further reveals that the influence of university students’ marital and reproductive view on their fertility intentions does not demonstrate statistical significance in univariate analysis, whereas their parents’ marital and reproductive view exhibit a significant effect. This discrepancy may reflect intergenerational differences in priorities: the younger generation places greater emphasis on personal and career goals, whereas parents, shaped by traditional cultural contexts, play a pivotal role in fertility-related decisions through their upbringing and expectations. These dynamics underscore the interplay between intergenerational priorities and cultural influences in shaping fertility intentions [74]. On the basis of these findings, policy recommendations should focus on eliminating structural and cultural barriers that influence university students’ fertility intentions, especially in contexts where parental characteristics and socioeconomic factors play significant roles. First, public awareness campaigns should prioritize challenging traditional gender roles and fertility norms to reduce potential obstacles to reproductive planning. For example, in families where parents are primarily engaged in physical labor, targeted support, such as financial subsidies or childcare services, could effectively alleviate the economic pressures that constrain fertility choices. Moreover, more flexible work‒family balance policies, including flexible working hours and comprehensive parental leave policies, should be introduced to mitigate the conflict between professional responsibilities and family planning. A family-friendly workplace environment, particularly support during the early stages of parenthood, is crucial in enhancing fertility intentions. It is essential to fully understand the intergenerational connections in reproductive decision-making. Parent‒child participation in specially designed awareness and education programs can foster a shared understanding of modern fertility expectations, thereby narrowing the generational gap caused by cultural pressures. Within higher education systems, integrating fertility-related knowledge into the curriculum can also play a positive role, such as by exploring the balance between personal development goals and family planning, to equip students with a comprehensive understanding of reproductive decisions. Finally, in addressing differences in fertility attitudes among various groups, policymaking should consider the complex interactions between cultural expectations, economic resources, and career aspirations to propose targeted measures. Special attention should be given to young individuals who aim to balance career advancement with family building. By reducing the indirect impact of parental occupation and socioeconomic background on young people’s fertility intentions, a more inclusive social environment can be cultivated. The implementation of these measures will not only help individuals achieve their dual goals of reproduction and career development but also provide long-term support for addressing issues related to sustainable population development.

Conclusion

This study highlights the critical influence of family functioning on university students’ fertility intentions, emphasizing that low-functioning families may transmit traditional values or impose parental pressures, disproportionately shaping students’ preferences for higher fertility. Socioeconomic factors, such as parental occupation and family stability, further modulate fertility intentions, with students from disadvantaged backgrounds showing lower intentions for multiple children. Generational shifts, reflecting younger generations’ delayed childbearing and prioritization of personal development, underscore evolving societal norms. Gender differences also play a significant role, with female students expressing lower fertility intentions due to persistent societal expectations regarding childbearing. Additionally, the study underscores the influence of cultural gender preferences on reproductive decisions, especially in the context of China’s declining fertility rates. These findings suggest that enhancing family functioning through communication and support, integrating fertility education into curricula, and addressing gender and economic barriers are critical. Policymakers should prioritize flexible family policies, financial subsidies, and childcare support to alleviate external pressures and foster sustainable fertility behavior. Tailored interventions that address family, socioeconomic, and gender disparities can bridge generational gaps and empower young individuals to make informed reproductive decisions in line with personal and societal aspirations. This research provides a foundation for addressing demographic challenges in the Chinese context, offering evidence-based strategies to promote sustainable fertility intentions amid rapid societal change.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design restricts causal inference, as it does not capture temporal changes in family functioning or fertility intentions. Second, self-reported data on sensitive topics may introduce social desirability or recall bias, affecting response accuracy. Third, while the revised Chinese Family Assessment Device (FAD) showed reliability, its cultural applicability and validity in capturing complex family interactions need further validation. Additionally, the study did not examine how fertility intentions translate into actual behaviors, limiting insights into long-term outcomes. Lastly, the dichotomous classification of family functioning oversimplifies its complexity, potentially obscuring nuanced variations. Future research should use longitudinal designs to explore causal relationships, and employ mixed-methods and more diverse samples to better understand the complexities of fertility intentions and family dynamics.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to all the university students and their parents who participated in this study, as well as to the faculty and staff at Ningxia Medical University for their invaluable assistance during the data collection process. We also extend our appreciation to the reviewers and editors for their constructive feedback, which significantly contributed to improving the quality of this manuscript. This research was supported by the Scientific Research Funding Project of Ningxia Medical University (Grant number: XZ2021034) and the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 23BRK036). The authors acknowledge the financial support provided by these institutions, which facilitated the completion of this study. Finally, we would like to thank our colleagues at the Department of Epidemiology and Statistics and the Key Laboratory of Environmental Factors and Chronic Disease Control for their insightful discussions and technical support throughout the research process.

Abbreviations

- LPA

Latent profile analysis

- FAD

Family assessment device

- AIC

Akaike information criterion

- BIC

Bayesian information criterion

- aBIC

Adjusted Bayesian information criterion

- LMR

LoMendell–Rubin

- BLRTs

Bootstrap likelihood ratio tests

Author contributions

Author Affiliation and Research InterestsHanyu PengHanyu Peng is a graduate student in the Department of Epidemiology and Statistics, School of Public Health and Management, Ningxia Medical University, Yinchuan, China. He is also affiliated with the Key Laboratory of Environmental Factors and Chronic Disease Control at Ningxia Medical University. His primary research focuses on fertility intentions, family functioning, and their impact on reproductive health, with expertise in quantitative methodologies such as latent profile analysis (LPA). As the first author of this study, he was responsible for formal analysis, data visualization, and manuscript drafting.Xintong ChouXintong Chou is a graduate student in the Department of Epidemiology and Statistics, School of Public Health and Management, Ningxia Medical University. Her research interests lie in reproductive epidemiology, public health policy, and social determinants of fertility behavior. She has experience in formal statistical analysis and methodology development, particularly in the application of advanced statistical modeling techniques to assess fertility-related factors.Zhen ZhangZhen Zhang is a researcher at the Department of Epidemiology and Statistics, School of Public Health and Management, Ningxia Medical University, and is also affiliated with the Key Laboratory of Environmental Factors and Chronic Disease Control. His research focuses on conceptual modeling of fertility behaviors, intergenerational influences on reproductive decision-making, and methodological advancements in public health studies. In this study, he contributed to research conceptualization and methodological design.Hongyan Qiu*Hongyan Qiu is a professor in the Department of Epidemiology and Statistics, School of Public Health and Management, Ningxia Medical University, and a senior researcher at the Key Laboratory of Environmental Factors and Chronic Disease Control. Her research expertise includes reproductive health, demographic studies, and epidemiological modeling of fertility behavior. She has led multiple national and provincial research projects in the field of fertility policy and reproductive health interventions. As the corresponding author, she supervised the project administration and contributed to the critical review and editing of this manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Scientific Research Funding Project of Ningxia Medical University (Grant number: XZ2021034) and the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 23BRK036), Natural Science Foundation of Ningxia Province, (Grant number: 2024AAC03226).

Data availability

Data availability Data and materials are available upon reasonable request. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to yanzide80@163.com or 19914567741@163.com.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and it has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Ningxia Medical University (Approval Number:2023-057). and informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Aassve A, Cavalli N, Mencarini L, Plach S, Livi Bacci M. The COVID-19 pandemic and human fertility. Science. 2020;369:370–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vollset SE, Goren E, Yuan C-W, Cao J, Smith AE, Hsiao T, et al. Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the global burden of disease study. Lancet. 2020;396:1285–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Fertility Data | Population Division. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/data/world-fertility-data?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Accessed 9 Jan 2025.

- 4.Total fertility rate globally. and by continent 1950–2024. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1034075/fertility-rate-world-continents-1950-2020/?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Accessed 9 Jan 2025.

- 5.Roser M. Fertility Rate. Our World Data. 2024.

- 6.Yang S, Jiang Q, Sánchez-Barricarte JJ. China’s fertility change: an analysis with multiple measures. Popul Health Metr. 2022;20: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yufen T, Zhili L, Qiannan G. The new situation of labor force change in China based on the 7th population census data. Popul Res. 2021;45:65. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yi Z. Improving population policy and promoting family patterns of respecting the aged, caring for the young and intergenerational assistance. Sci Technol Rev. 2021;39:130–40. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Main Data of the Seventh National Population Census. https://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202105/t20210510_1817185.html. Accessed 8 Jan 2025.

- 10.Full text. Resolution of CPC Central Committee on further deepening reform comprehensively to advance Chinese modernization. https://english.www.gov.cn/policies/latestreleases/202407/21/content_WS669d0255c6d0868f4e8e94f8.html. Accessed 8 Jan 2025.

- 11.National Economy Withstood Pressure and Reached a New Level. in 2022. https://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202301/t20230117_1892094.html. Accessed 8 Jan 2025.

- 12.China releases decision on third-child policy. supporting measures. https://english.www.gov.cn/policies/latestreleases/202107/20/content_WS60f6c308c6d0df57f98dd491.html. Accessed 16 Jul 2025.

- 13.China’s three-. child policy to improve demographic structure. http://en.qstheory.cn/2021-06/02/c_628976.htm. Accessed 16 Jul 2025.

- 14.Bongaarts J, Sobotka T. A demographic explanation for the recent rise in European fertility. Popul Dev Rev. 2012;38:83–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhenwu Z, Ruizhen Z. On the relationship between aging and macroeconomy. Popul Res. 2016;40:75. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jinying W, Zhuangyuan L, Dongmei W. A reconceptualization of china’s goals for Long-term population development to strengthen the economy. Popul Res. 2022;46:40. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sørensen NO, Marcussen S, Backhausen MG, Juhl M, Schmidt L, Tydén T, et al. Fertility awareness and attitudes towards parenthood among Danish university college students. Reprod Health. 2016;13:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim HW, Kim SY. Gender differences in willingness for childbirth, fertility knowledge, and value of motherhood or fatherhood and their associations among college students in South Korea, 2021. Arch Public Health. 2023;81(1): 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alfaraj S, Aleraij S, Morad S, Alomar N, Rajih HA, Alhussain H, et al. Fertility awareness, intentions concerning childbearing, and attitudes toward parenthood among female health professions students in Saudi Arabia. Int J Health Sci. 2019;13:34–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou Y, Luo Y, Wang T, Cui Y, Chen M, Fu J. College students responding to the Chinese version of Cardiff fertility knowledge scale show deficiencies in their awareness: a cross-sectional survey in Hunan, China. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epstein NB, Baldwin LM, Bishop DS. THE McMASTER FAMILY ASSESSMENT DEVICE. J Marital Fam Ther. 1983;9:171–80. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olson D. FACES IV and the circumplex model: validation study. J Marital Fam Ther. 2011;37:64–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bongaarts J, Casterline J. Fertility transition: is sub-Saharan Africa different?? Popul Dev Rev. 2013;38(Suppl 1):153–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mencarini L, Vignoli D, Gottard A. Fertility intentions and outcomes: implementing the theory of planned behavior with graphical models. Adv Life Course Res. 2015;23:14–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lebano A, Jamieson L. Childbearing in Italy and spain: postponement narratives. Popul Dev Rev. 2020;46:121–44. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guzzo KB, Hayford SR. Pathways to parenthood in social and family contexts: decade in review, 2020. J Marriage Fam. 2020;82:117–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winckler EA. Chinese reproductive policy at the turn of the millennium: dynamic stability. Popul Dev Rev. 2002;28:379–418. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jing W, Liu J, Ma Q, Zhang S, Li Y, Liu M. Fertility intentions to have a second or third child under China’s three-child policy: a national cross-sectional study. Hum Reprod. 2022. 10.1093/humrep/deac101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo Q. How people’s concepts of marriage, childbearing, childrearing, and child education affect their fertility willingness and behaviour under the three-child policy in China?? Int J Law Policy Family. 2023;37: ebad028. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li X, Curran M, Paschall K, Barnett M, Kopystynska O. Pregnancy intentions and family functioning among low-income, unmarried couples: Person-centered analyses. J Fam Psychol JFP J Div Fam Psychol Am Psychol Assoc Div. 2019;43:33:830–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Identifying family personality profiles using latent profile analysis: Relations to happiness and health | Request PDF. ResearchGate. 2024. 10.1016/j.paid.2021.111480

- 32.Spurk D, Hirschi A, Wang M, Valero D, Kauffeld S. Latent profile analysis: a review and how to guide of its application within vocational behavior research. J Vocat Behav. 2020;120: 103445. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent class and latent transition analysis: with applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. John Wiley and Sons Inc.; 2010.

- 34.Berlin KS, Williams NA, Parra GR. An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 1): overview and cross-sectional latent class and latent profile analyses. J Pediatr Psychol. 2014;39:174–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pastor DA, Barron KE, Miller BJ, Davis SL. A latent profile analysis of college students’ achievement goal orientation. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2007;32:8–47. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu J, Li L, Ma X-Q, Zhang M, Qiao J, Redding SR, et al. Fertility intentions, parenting attitudes, and fear of childbirth among college students in China: a cross-sectional study. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2023;36:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]