Abstract

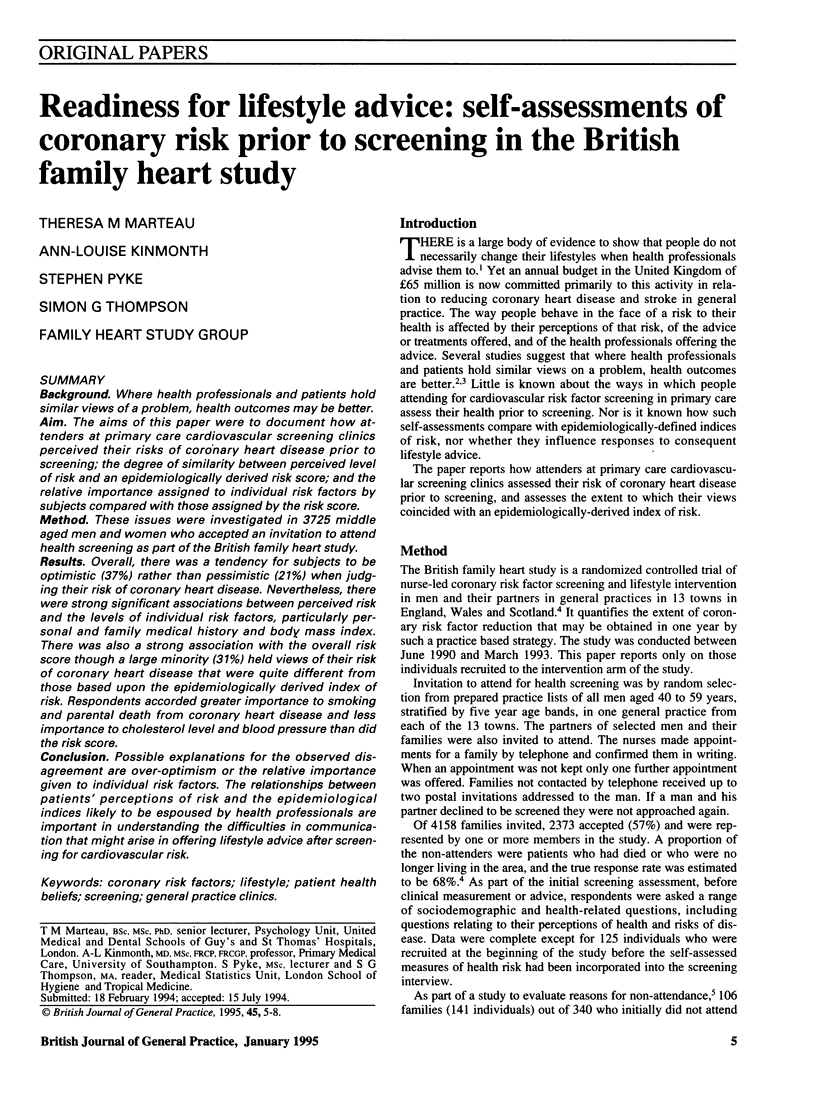

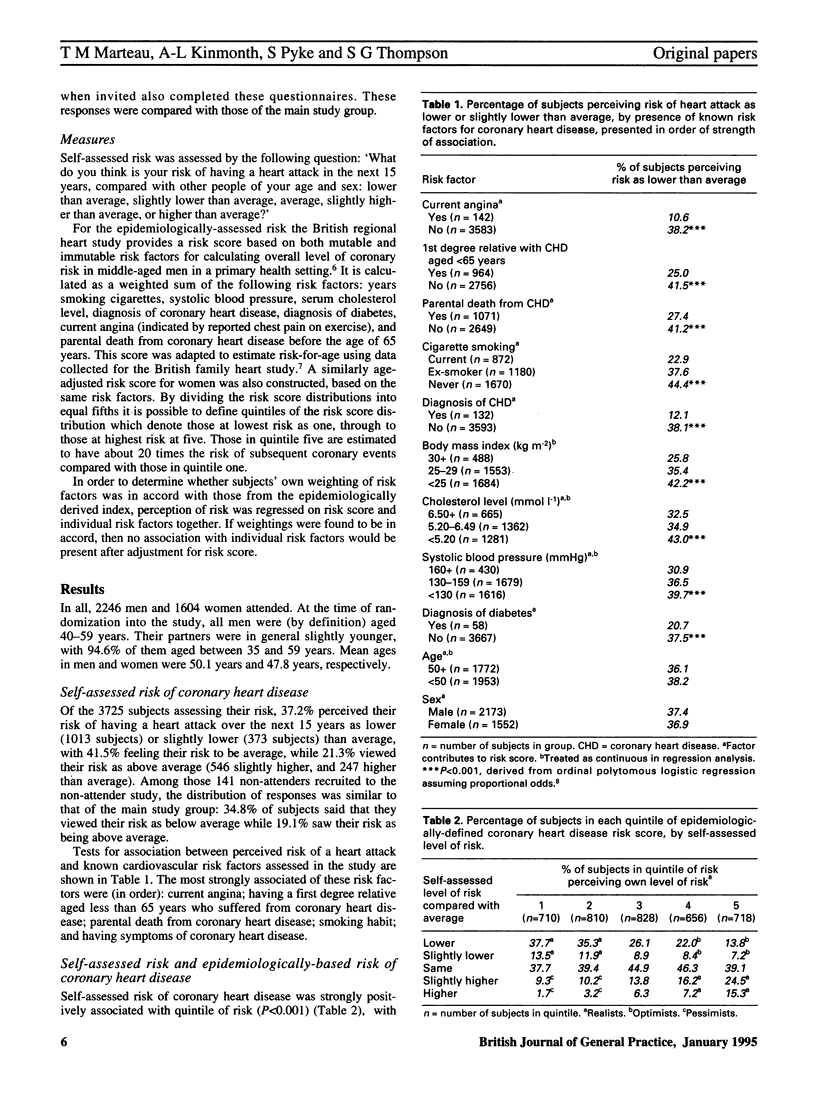

BACKGROUND. Where health professionals and patients hold similar views of a problem, health outcomes may be better. AIM. The aims of this paper were to document how attenders at primary care cardiovascular screening clinics perceived their risks of coronary heart disease prior to screening; the degree of similarity between perceived level of risk and an epidemiologically derived risk score; and the relative importance assigned to individual risk factors by subjects compared with those assigned by the risk score. METHOD: These issues were investigated in 3725 middle aged men and women who accepted an invitation to attend health screening as part of the British family heart study. RESULTS. Overall, there was a tendency for subjects to be optimistic (37%) rather than pessimistic (21%) when judging their risk of coronary heart disease. Nevertheless, there were strong significant associations between perceived risk and the levels of individual risk factors, particularly personal and family medical history and body mass index. There was also a strong association with the overall risk score though a large minority (31%) held views of their risk of coronary heart disease that were quite different from those based upon the epidemiologically derived index of risk. Respondents accorded greater importance to smoking and parental death from coronary heart disease and less importance to cholesterol level and blood pressure than did the risk score. CONCLUSION. Possible explanations for the observed disagreement are over-optimism or the relative importance given to individual risk factors. The relationships between patients' perceptions of risk and the epidemiological indices likely to be espoused by health professionals are important in understanding the difficulties in communication that might arise in offering lifestyle advice after screening for cardiovascular risk.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Avis N. E., Smith K. W., McKinlay J. B. Accuracy of perceptions of heart attack risk: what influences perceptions and can they be changed? Am J Public Health. 1989 Dec;79(12):1608–1612. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.12.1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie C. R., Bradley C. Causal attributions of doctor and patients in a diabetes clinic. Br J Clin Psychol. 1988 Feb;27(Pt 1):67–76. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1988.tb00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSENGREN W. R. Some social psychological aspects of delivery room difficulties. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1961 Jun;132:515–521. doi: 10.1097/00005053-196106000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaper A. G., Pocock S. J., Phillips A. N., Walker M. A scoring system to identify men at high risk of a heart attack. Health Trends. 1987 May;19(2):37–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silagy C., Muir J., Coulter A., Thorogood M., Roe L. Cardiovascular risk and attitudes to lifestyle: what do patients think? BMJ. 1993 Jun 19;306(6893):1657–1660. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6893.1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein N. D., Sandman P. M. A model of the precaution adoption process: evidence from home radon testing. Health Psychol. 1992;11(3):170–180. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.3.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein N. D. Why it won't happen to me: perceptions of risk factors and susceptibility. Health Psychol. 1984;3(5):431–457. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.3.5.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]