Abstract

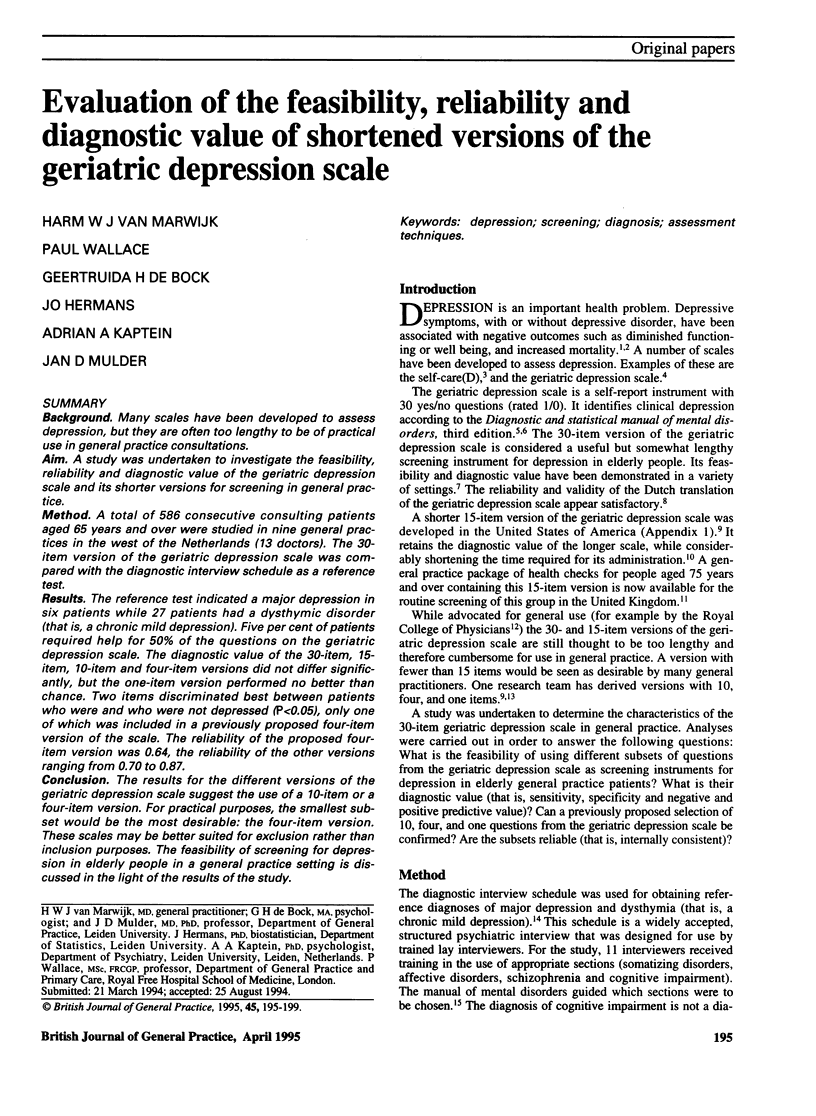

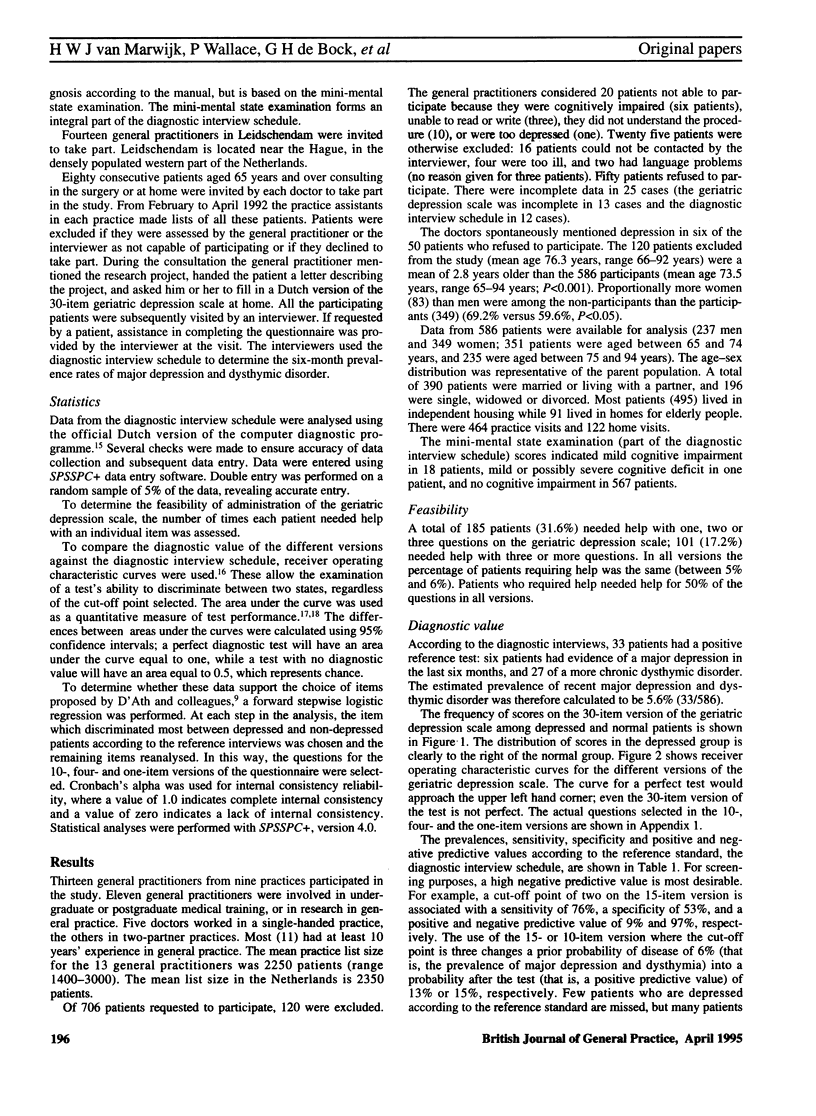

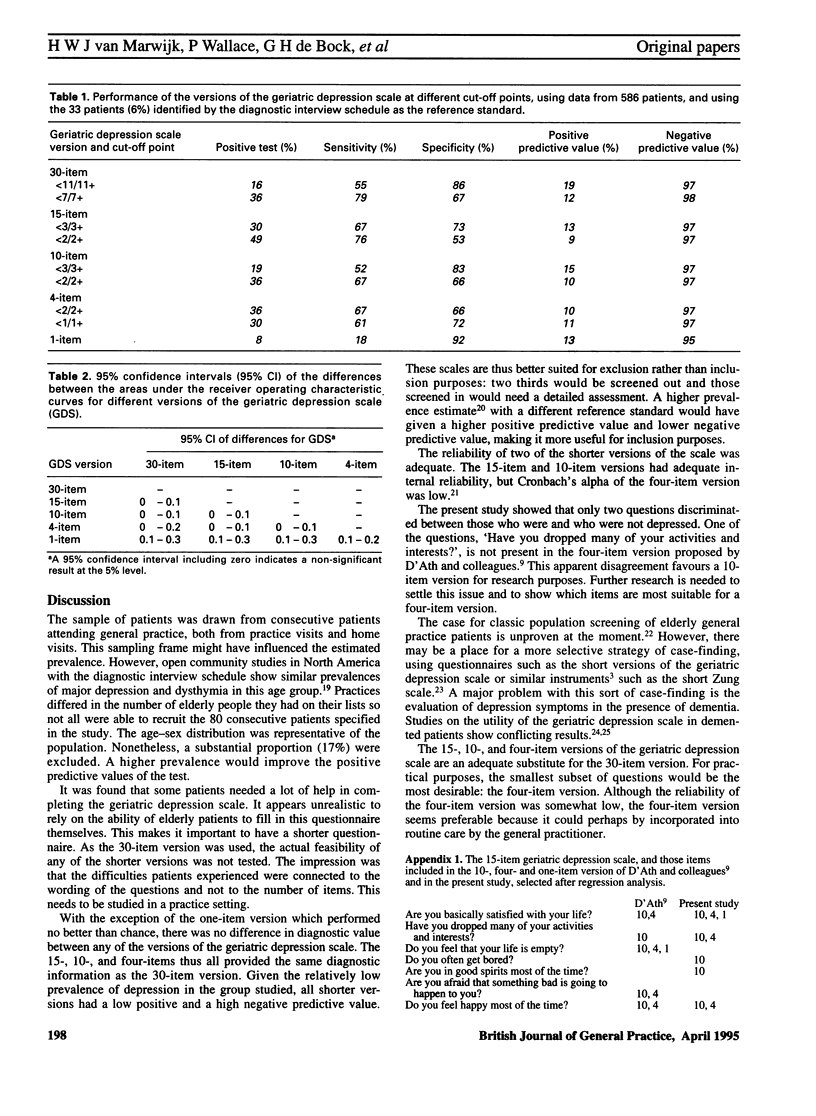

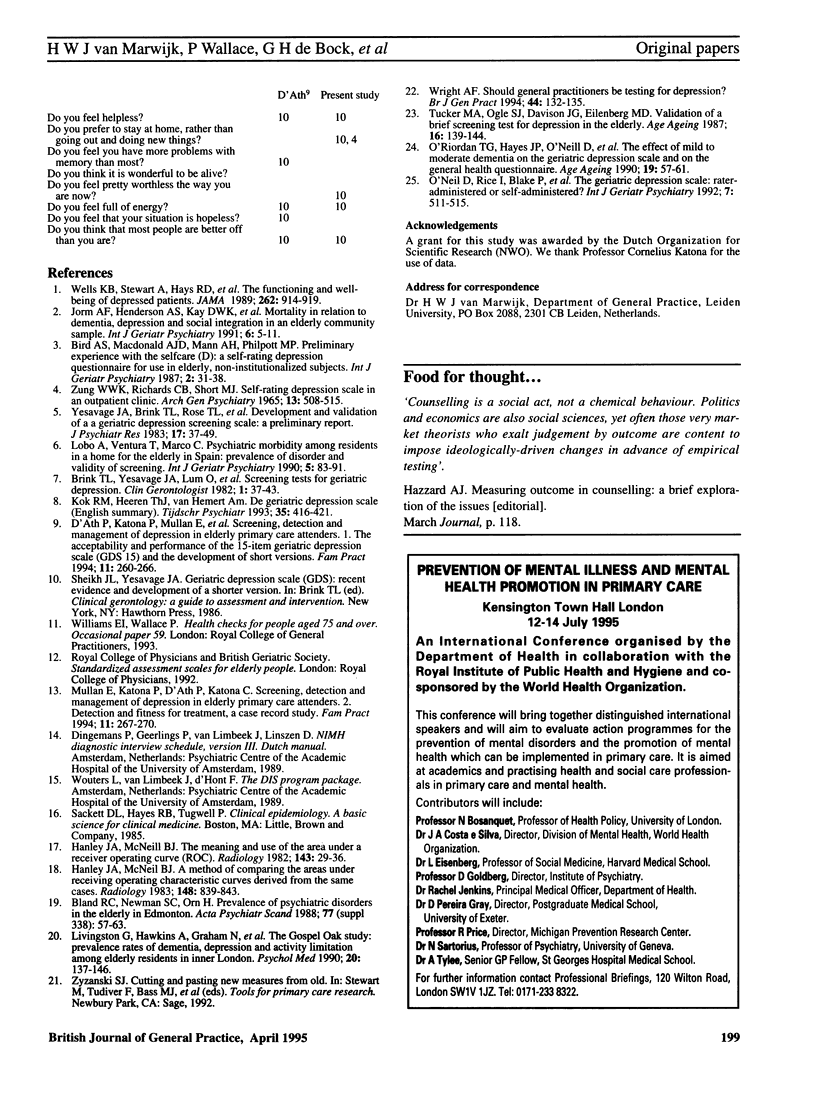

BACKGROUND. Many scales have been developed to assess depression, but they are often too lengthy to be of practical use in general practice consultations. AIM. A study was undertaken to investigate the feasibility, reliability and diagnostic value of the geriatric depression scale and its shorter versions for screening in general practice. METHOD. A total of 586 consecutive consulting patients aged 65 years and over were studied in nine general practices in the west of the Netherlands (13 doctors). The 30-item version of the geriatric depression value was compared with the diagnostic interview schedule as a reference test. RESULTS. The reference test indicated a major depression in six patients while 27 patients had a dysthymic disorder (that is, a chronic mild depression). Five per cent of patients required help for 50% of the questions on the geriatric depression scale. The diagnostic value of the 30-item, 15-item, 10-item and four-item versions did not differ significantly, but the one-item version performed no better than chance. Two items discriminated best between patients who were and who were not depressed (P < 0.05), only one of which was included in a previously proposed four-item version of the scale. The reliability of the proposed four-item version was 0.64, the reliability of the other versions ranging from 0.70 to 0.87. CONCLUSION. The results for the different versions of the geriatric depression scale suggest the use of a 10-item or a four-item version. For practical purposes, the smallest subset would be the most desirable: the four-item version. These scales may be better suited for exclusion rather than inclusion purposes. The feasibility of screening for depression in elderly people in a general practice setting is discussed in the light of the results of the study.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bland R. C., Newman S. C., Orn H. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the elderly in Edmonton. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1988;338:57–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1988.tb08548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Ath P., Katona P., Mullan E., Evans S., Katona C. Screening, detection and management of depression in elderly primary care attenders. I: The acceptability and performance of the 15 item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS15) and the development of short versions. Fam Pract. 1994 Sep;11(3):260–266. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley J. A., McNeil B. J. A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology. 1983 Sep;148(3):839–843. doi: 10.1148/radiology.148.3.6878708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley J. A., McNeil B. J. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982 Apr;143(1):29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston G., Hawkins A., Graham N., Blizard B., Mann A. The Gospel Oak Study: prevalence rates of dementia, depression and activity limitation among elderly residents in inner London. Psychol Med. 1990 Feb;20(1):137–146. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700013313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullan E., Katona P., D'Ath P., Katona C. Screening, detection and management of depression in elderly primary care attenders. II: Detection and fitness for treatment: a case record study. Fam Pract. 1994 Sep;11(3):267–270. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Riordan T. G., Hayes J. P., O'Neill D., Shelley R., Walsh J. B., Coakley D. The effect of mild to moderate dementia on the Geriatric Depression Scale and on the General Health Questionnaire. Age Ageing. 1990 Jan;19(1):57–61. doi: 10.1093/ageing/19.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker M. A., Ogle S. J., Davison J. G., Eilenberg M. D. Validation of a brief screening test for depression in the elderly. Age Ageing. 1987 May;16(3):139–144. doi: 10.1093/ageing/16.3.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K. B., Stewart A., Hays R. D., Burnam M. A., Rogers W., Daniels M., Berry S., Greenfield S., Ware J. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989 Aug 18;262(7):914–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright A. F. Should general practitioners be testing for depression? Br J Gen Pract. 1994 Mar;44(380):132–135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zung W. W., Richards C. B., Short M. J. Self-rating depression scale in an outpatient clinic. Further validation of the SDS. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965 Dec;13(6):508–515. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01730060026004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]