Abstract

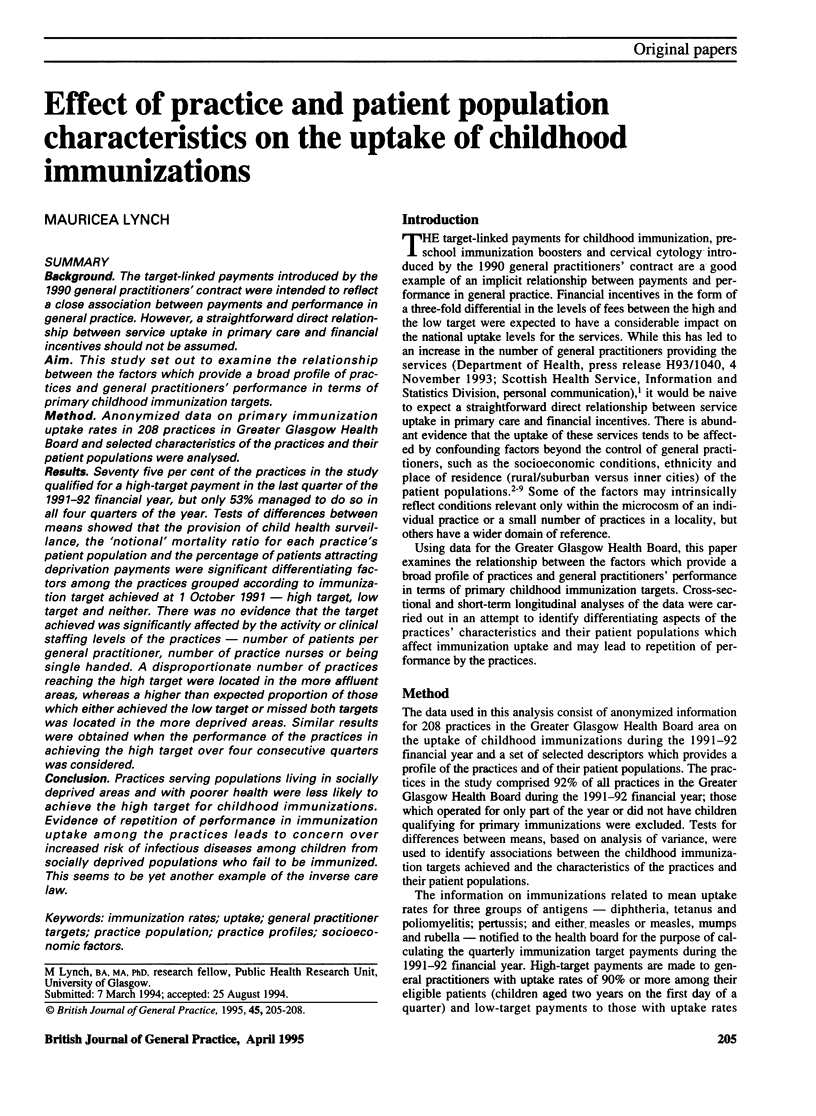

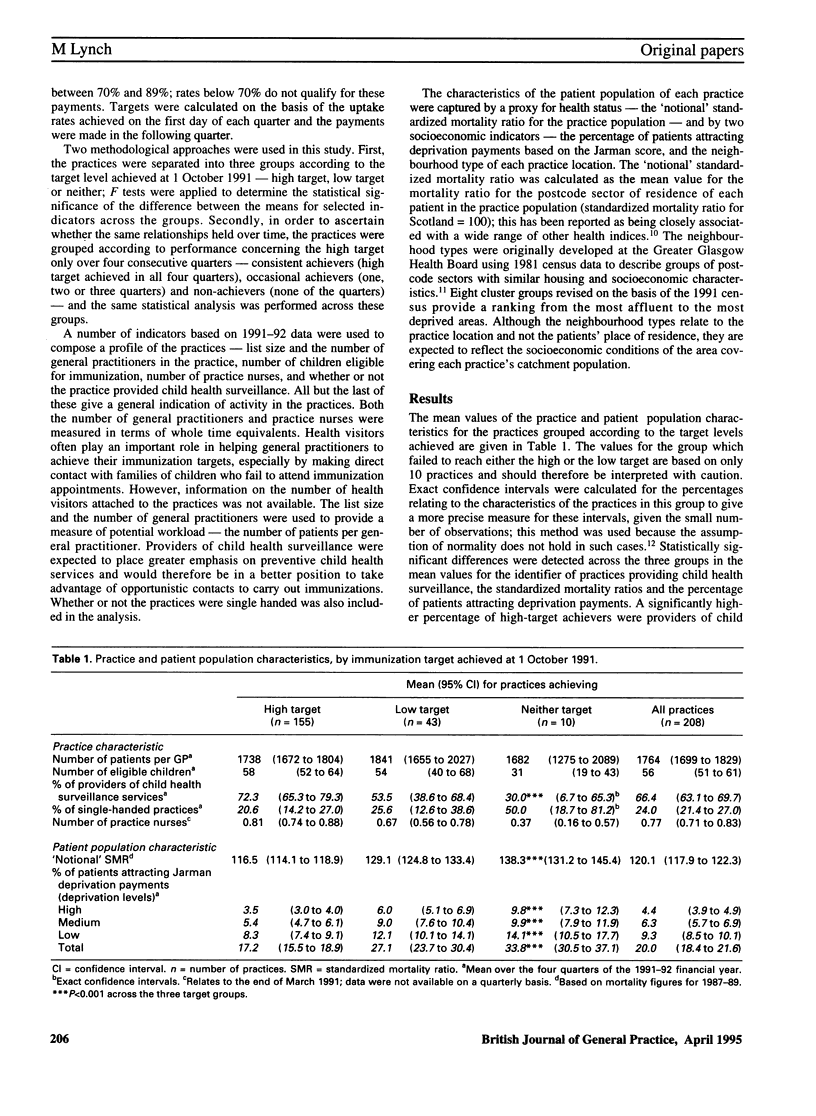

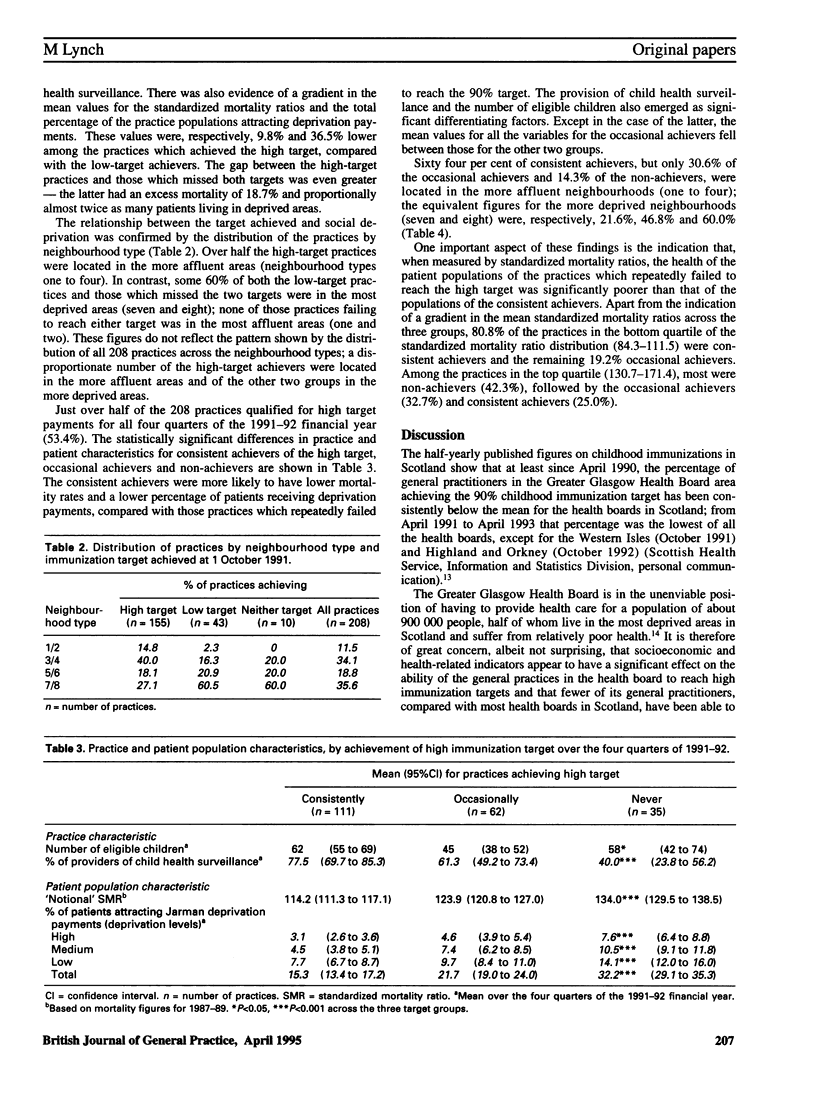

BACKGROUND. The target-linked payments introduced by the 1990 general practitioners' contact were intended to reflect a close association between payments and performance in general practice. However, a straightforward direct relationship between service uptake in primary care and financial incentives should not be assumed. AIM. This study set out to examine the relationship between the factors which provide a broad profile of practices and general practitioners' performance in terms of primary childhood immunization targets. METHOD. Anonymized data on primary immunization uptake rates in 208 practices in Greater Glasgow Health Board and selected characteristics of the practices and their patient populations were analysed. RESULTS. Seventy five per cent of the practices in the study qualified for a high-target payment in the last quarter of the 1991-92 financial year, but only 53% managed to do so in all four quarters of the year. Tests of differences between means showed that the provision of child health surveillance, the notional' mortality ratio for each practice's patient population and the percentage of patients attracting deprivation payments were significant differentiating factors among the practices grouped according to immunization target achieved at 1 October 1991--high target, low target and neither. There was no evidence that the target achieved was significantly affected by the activity or clinical staffing levels of the practices--number of patients per general practitioner, number of practice nurses or being single handed. A disproportionate number of practices reaching the high target were located in the more affluent areas, whereas a higher than expected proportion of those which either achieved the low target or missed both targets was located in the more deprived areas. Similar results were obtained when the performance of the practices in achieving the high target over four consecutive quarters was considered. CONCLUSION. Practice serving populations living in socially deprived areas and with poorer health were less likely to achieve the high target for childhood immunizations. Evidence of repetition of performance in immunization uptake among the practices leads to concern over increased risk of infectious diseases among children from socially deprived populations who fail to be immunized. This seems to be yet another example of the inverse care law.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baker M. R., Bandaranayake R., Schweiger M. S. Differences in rate of uptake of immunisation among ethnic groups. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984 Apr 7;288(6423):1075–1078. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6423.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balarajan R., Yuen P., Machin D. Socioeconomic differentials in the uptake of medical care in Great Britain. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1987 Sep;41(3):196–199. doi: 10.1136/jech.41.3.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillam S. J. Provision of health promotion clinics in relation to population need: another example of the inverse care law? Br J Gen Pract. 1992 Feb;42(355):54–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart J. T. The inverse care law. Lancet. 1971 Feb 27;1(7696):405–412. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)92410-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes R. Inequalities in health and health service use: evidence from the General Household Survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33(4):361–368. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarman B., Bosanquet N., Rice P., Dollimore N., Leese B. Uptake of immunisation in district health authorities in England. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988 Jun 25;296(6639):1775–1778. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6639.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Taylor B. Comparison of immunisation rates in general practice and child health clinics. BMJ. 1991 Oct 26;303(6809):1035–1038. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6809.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M. L. The uptake of childhood immunization and financial incentives to general practitioners. Health Econ. 1994 Mar-Apr;3(2):117–125. doi: 10.1002/hec.4730030208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie L. D., Bisset A. F., Russell D., Leslie V., Thomson I. Primary and preschool immunisation in Grampian: progress and the 1990 contract. BMJ. 1992 Mar 28;304(6830):816–819. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6830.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorogood M., Coulter A., Jones L., Yudkin P., Muir J., Mant D. Factors affecting response to an invitation to attend for a health check. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1993 Jun;47(3):224–228. doi: 10.1136/jech.47.3.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]