Abstract

Objective

Gastric cancer (GC), a widely recognized malignant neoplasm, poses significant treatment challenges. It is essential to pursue additional research to uncover novel therapeutic approaches and predictive methodologies. The phenomenon of disulfidptosis, recently identified as a distinct type of programmed cell death, offers intriguing possibilities for therapeutic applications.

Method

This study performed differential analysis, GO analysis, KEGG, GSEA, and other analyses to investigate the relationship between disulfidptosis-related LncRNAs (DRLs) and TCGA GC data. The analysis included 373 gastric cancer samples and 32 normal gastric tissue samples, obtained from [specify data source, e.g., TCGA, GEO, or in-house cohorts]. Samples were rigorously screened based on [criteria, e.g., histopathological confirmation, RNA quality, or clinical completeness], and transcriptomic data were processed using [specific tools or pipelines] to ensure reproducibility. A new, more accurate predictive model was constructed, identifying potential therapeutic targets, signaling pathways, and sensitive drugs.

Results

A refined prognostic signature associated with disulfidptosis in GC was developed through over 200 Lasso regression and MultiCox calculations. It was discovered that AL359182.1 and AC107021.2 could influence GC prognosis by modulating the MYH10/LIGHT JUNCTION or MYH10/REGULATION OF ACTIN CYTOSKELETON pathways. Notably, AL359182.1, newly identified as linked to GC prognosis, emerges as a potential novel therapeutic target. Furthermore, this study enhanced the accuracy of immunotherapy evaluations and screened for potential sensitive drugs.

Conclusion

Leveraging DRLs and TCGA GC data, this research identified highly precise prognostic signatures consisting of four LncRNAs: PINK1-AS, AC107021.2, AL359182.1, and AC009486.1. The discovery of two new signaling pathways could impact the prognosis of GC. AL359182.1 is proposed as a novel potential therapeutic target. The identified signature also effectively predicts the immunogenicity of GC and facilitates the screening of sensitive drugs. Further experimental validation is suggested to strengthen these conclusions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-025-03160-4.

Keywords: Disulfidptosis, Gastric cancer, Signature, Therapeutic target, Immunity, Prognosis

Introduction

GC exhibits higher incidence and mortality rates compared to other malignancies [1]. The distribution of this disease exhibits significant geographic variation, with particularly elevated incidence rates found in East Asian countries [2] such as Japan and South Korea [3–5]. The initial manifestations of GC frequently present in a subtle manner, resulting in a diagnosis that is often postponed, typically occurring five years subsequent to the emergence of symptoms. While the five-year survival rate for individuals diagnosed at early stages (IA or IB) following surgical intervention is notably elevated, it markedly declines as the disease progresses to more advanced stages [6]. As a result, identifying new biomarkers and understanding the underlying mechanisms is crucial for enhancing prognosis and therapeutic results.

Long non-coding RNAs (LncRNAs), a subset of the larger ncRNA family, are essential in the regulation of gene expression and participate in numerous biological and pathological processes, such as the development and progression of cancer [7]. Recent studies have highlighted the crucial function of LncRNAs in the development of GC [8]. For instance, LncRNA SNHG3 promotes the proliferation of GC cells and facilitates distant metastasis through the miRNA139-5p/MYB pathway [9], while LncRNA SNHG6 plays a role in the chemoresistance of these cells to cisplatin and their progression via the miR-1297/BCL-2 pathway [10].

Recent discoveries have illuminated disulfidptosis [11, 12], an intriguing form of cellular demise triggered by the abnormal buildup of intracellular disulfides in conditions of glucose deprivation. This mechanism is unique when compared to other extensively studied cellular demise processes like cuproptosis and ferroptosis. Initial investigations have associated disulfidptosis with clinical outcomes and immune responses in liver cancer, indicating its possible role as a therapeutic target in liver cancer [13]. Nonetheless, the precise function and underlying mechanisms of disulfidptosis in GC necessitate additional clarification [14].

In the context of disulfide apoptosis, the composition and functional status of immune infiltrating cells undergo dynamic alterations, exerting a profound impact on cancer treatment response. These changes intricately modulate the tumor microenvironment, thereby influencing how tumors respond to therapeutic interventions. Systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), combining platelets, neutrophils, and lymphocytes, correlates with TME immunosuppression [15]. A variety of immune cells exhibited significant variations, such as M2 macrophages, mast cells, MHC class I, neutrophils, T helper cells, Th1 and Th2 cells, Type II IFN response, cytolytic activity, and APC co-inhibition [16]. The CD36-BATF2/MYB axis, which modulates the expression of these T cells, seems to impact GC prognosis [15], highlighting their significance in disease progression.

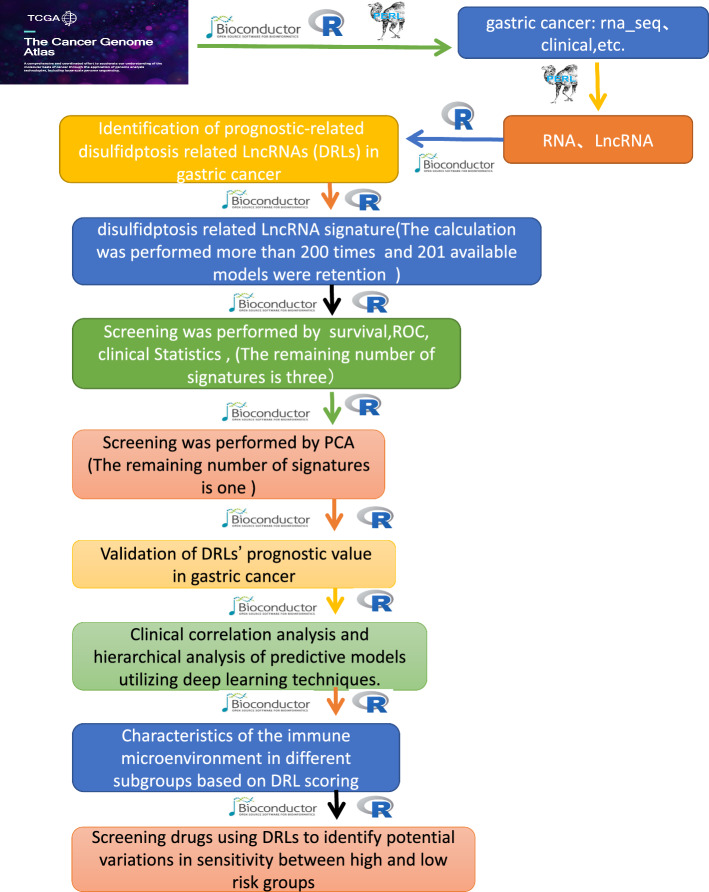

In this study, sequencing data from GC tissues and adjacent non-cancerous tissues, sourced from the TCGA [17], were analyzed alongside 24 disulfidptosis genes [11]. The aim was to explore the mechanisms by which DRLs contribute to GC’s occurrence and progression. A novel signature related to DRLs was established, and its feasibility and predictive accuracy were validated. Through norm plots, independent factors influencing GC were identified, paving the way for new therapeutic targets and potential sensitive drugs. Further details are provided in the flowchart (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of this study

Materials and methods

Sample selection criteria

We collected and curated gastric cancer (GC)-related gene expression data from the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/repository), comprising 373 gastric cancer tissue samples, 32 normal gastric tissue samples, corresponding clinical data (443 samples), and mutation/copy number data (434 samples). The sample selection criteria are as follows: (1) gastric cancer; (2) clearly distinguish tumor vs. normal tissue, different subtypes (such as Lauren classification and WHO classification of gastric cancer), and different stages (such as TNM stage); (3) the number of patients ≥ 30; (4) clinical characteristics (such as age, gender, treatment history) were matched to avoid confounding variables.

Data processing steps

Data processing and analysis were primarily performed using R software (version 4.1.3) and Perl software (version 5.30.0). First, a Perl script was used to extract and organize the expression matrix for gastric cancer and adjacent normal tissues, from which long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) and messenger RNA (mRNA) expression matrices were isolated for downstream analysis. Clinical data were similarly extracted via Perl scripting. Next, by integrating disulfide death-related genes (DRLs), we extracted the corresponding mRNA and lncRNA expression matrices associated with disulfide death. Clinical data were then merged with the disulfide death-related lncRNA expression matrix to generate a comprehensive dataset containing survival information. Finally, we analyzed the correlation between disulfide death-related mRNAs and lncRNAs to investigate their interdependencies.

Screening of DRLs and establishment and validation of DRLs signature

We performed a thorough investigation of disulfidptosis genes after extracting GC-related data from the TCGA database. After using R software to study LncRNAs linked to disulfidptosis genes, highly correlated LncRNAs were identified through univariate analysis. In order to construct a predictive model, further analyses comprised multivariate and univariate Cox regression as well as Lasso regression. A criteria of P < 0.01 was used for filtering, and samples were divided 200 times at random, producing 201 unique predictive models. Proponent component analysis (PCA), clinical statistics, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, and survival analysis all verified the validity. The expression formula [18] is as follows: , where Coefi is the coefficient and Xi is the expression level of LncRNA. The heatmap shows the results of the analysis of the correlations between the disulfidptosis genes and the LncRNAs in the predictive model. The TCGA database was queried for samples pertaining to disulfide death genes using subgroup analysis. The samples were then randomly assigned to either the testing or training groups. For each subgroup, we ran survival analyses, ROC curves, risk curves, and survival status graphs. A heatmap was created using cluster analysis on the LncRNA of the predictive model, and PFS analysis was carried out to further validate the model.

, where Coefi is the coefficient and Xi is the expression level of LncRNA. The heatmap shows the results of the analysis of the correlations between the disulfidptosis genes and the LncRNAs in the predictive model. The TCGA database was queried for samples pertaining to disulfide death genes using subgroup analysis. The samples were then randomly assigned to either the testing or training groups. For each subgroup, we ran survival analyses, ROC curves, risk curves, and survival status graphs. A heatmap was created using cluster analysis on the LncRNA of the predictive model, and PFS analysis was carried out to further validate the model.

Comparison of the accuracy of risk score with age, gender, grade, and stage in predicting GC prognosis, with construction of normogram

Following univariate and multivariate COX, ROC, and C-curve analyses on age, gender, grade, stage, and risk score, a normogram was produced. Conformance curves validated the normogram's prognostic precision. Age, gender, G stage, M stage, N stage, Stage, and T stage prognosis studies were conducted utilizing the Risk score, and principal component analysis (PCA) was used to analyze the score's efficacy.

Difference analysis, gene ontology (GO), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

Samples were grouped based on risk scores from the predictive model for conducting difference analysis, identifying significantly differentiated genes. These genes underwent GO [2, 5], KEGG [2, 5, 19], and GSEA [2, 5, 20] analysis to identify potential pathways and functions.

Analysis of the correlation between the risk model and immune-related features in GC

The predictive model was employed to investigate the tumor microenvironment (TME), incorporating CIBERSORT [2, 5, 21], immCor, immFunction, tumor mutational burden (TMB) [5, 22, 23], TMB stratification, and Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE) analysis. The tumor microenvironment (TME) scores, including StromalScore, ImmuneScore, and ESTIMATEScore, are computational metrics derived from bulk tumor transcriptomic data to quantify the proportions of stromal and immune cells within tumor tissues. These scores are calculated using the ESTIMATE algorithm (Estimation of STromal and Immune cells in MAlignant Tumor tissues using Expression data) as follows: (1) Stromal Score: Reflects the abundance of stromal components (e.g., fibroblasts, endothelial cells) in the tumor. It is calculated based on the expression of stromal-specific genes. (2) Immune Score: Represents the infiltration level of immune cells (e.g., T cells, B cells, macrophages) using immune-related gene signatures. (3) ESTIMATE Score: A composite score combining StromalScore and ImmuneScore, providing an overall assessment of the tumor microenvironment's non-malignant cellular composition. These thorough examinations evaluated the relationship between the risk model and immune-related characteristics in GC.

Drug sensitivity analysis

Predictive models, in conjunction with the oncoPredict package, were utilized to screen and identify drugs with potentially significant differences in sensitivity for GC treatment.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.1.3), and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

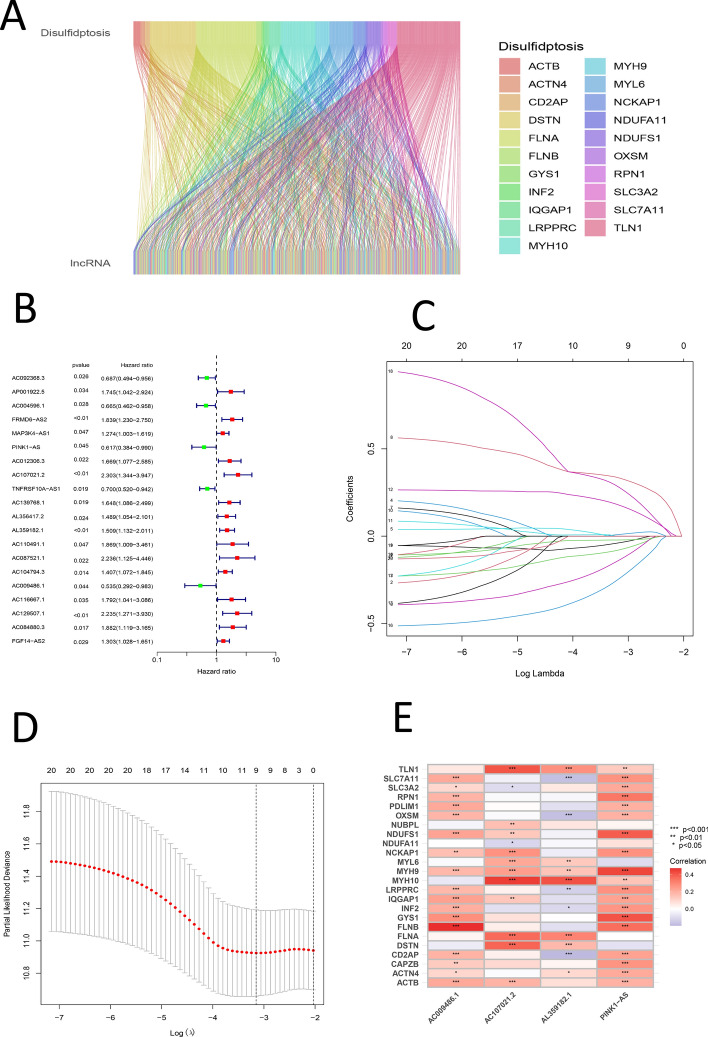

Screening of DRLs, establishment of a prognostic signature, correlation heatmap results between signature-related LncRNAs and Cuprotosis Genes, and validation of the GC DRLs signature

A Sankey diagram, produced with the ggalluvial package in R, illustrated the relationships between lncRNAs and genes associated with disulfidptosis (Fig. 2A). Univariate Cox analysis was utilized to pinpoint lncRNAs exhibiting significant differential expression, which were then illustrated in a forest plot (Fig. 2B). A prognostic signature associated with GC disulfidptosis was developed using LASSO regression and MultiCox methods, with over 200 iterations performed. The established signature, validated through survival, ROC, clinical statistics, and PCA analyses, is defined by the following equation: Risk score = (− 0.442699326178612 * expression of PINK1-AS) + (− 0.707433510160127 * expression of AC107021.2) + (0.339431715443403 * expression of AL359182.1) + (− 0.529105377757355 * expression of AC009486.1) (Fig. 2C). Heatmaps were also presented to illustrate the correlations between disulfidptosis-related genes and the signature (Fig. 2C–E). Model lncRNAs and their associated disulfidptosis-related genes were further identified (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

A Sankey diagram illustrating the relationship between disulfidptosis genes and LncRNAs. B Forest plot of univariate analysis of significantly different LncRNAs. C Lasso regression plot. D Cvfit plot of lasso regression. E Heatmap showing the relationship between DRGs and signature LncRNAs

DRL-related samples were evenly divided into testing and training groups. The DRLs signature categorized the stratified samples of the overall, test, and training groups into high-risk and low-risk classifications. The conducted analyses encompassed survival metrics, risk scoring, survival duration, enrichment factors, and progression-free survival (PFS) for each distinct group. The findings revealed a markedly poorer prognosis for the high-risk cohort (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3A–C). The patterns observed in risk scores were uniform across the different groups, exhibiting values below 1 in the low-risk category and exceeding 1 in the high-risk category (Fig. 3D–F). Survival time analysis showed a consistent distribution of survival times, with fewer deaths in the low-risk group (Fig. 3G–I). Enrichment analysis of signature lncRNAs was conducted for each group, identifying AC107021.2 and AL359182.1 as high-risk lncRNAs, and PINK1-AS and AC009486.1 as low-risk lncRNAs (Fig. 3J–L). PFS analysis revealed a lower PFS probability in the high-risk group (Fig. 3M).

Fig. 3.

A Survival analysis of high- and low-risk groups in the total sample (P < 0.05). B Survival analysis between high- and low-risk groups in the test sample (P < 0.05). C Survival analysis between high- and low-risk groups in the training sample (P < 0.05). D Risk curve for the total sample. E Risk curve for the test sample. F Risk curve for the training sample. G Survival status map for the total sample. H Survival status map for the test sample. I Survival status map for the training sample. J Prognostic lncRNA signature heatmap for the total sample. K Prognostic lncRNA signature heatmap for the test sample. L Prognostic lncRNA signature heatmap for the training sample. M PFS between high- and low-risk groups (P < 0.05)

Evaluating the impact of clinical parameters including risk score, age, gender, grade, and stage on the prognosis of GC, with results of nomogram, adjusted curves, stratified analysis of clinical characteristics, and PCA analysis

Univariate and multivariate Cox analyses, ROC analyses for clinical characteristics, ROC analyses for survival duration, and Concordance index (C-index) analyses were performed for the Risk score, alongside the clinical characteristics of Age, Gender, Grade, and Stage. It was observed that Age, Grade, Stage, and Risk score had a significant influence on the prognosis of GC (P < 0.05), whereas Gender did not exhibit a significant effect (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4A, B). ROC analysis of clinical characteristics indicated that the AUC values for Age, Grade, Stage, and Risk score exceeded 0.5, while the AUC for Gender fell below 0.5 (Fig. 4C). ROC analysis concerning survival duration indicated that the AUC values for 1, 3, and 5 years exceeded 0.6 (Fig. 4D). The analysis of the Concordance index (C-index) revealed that the Risk score serves as the predominant factor influencing the prognosis of GC, while Gender exhibits the minimal effect (Fig. 4E). A normogram was developed utilizing Risk score, Age, Gender, Grade, Stage, M stage, N stage, and T stage, highlighting Risk score and Age as independent variables affecting prognosis (Fig. 4F). A correction curve was plotted to validate the normogram’s accuracy (Fig. 4G).

Fig. 4.

A Univariate COX analysis of Age, Grade, Stage, and Risk score. B Multivariate COX analysis of Age, Grade, Stage, and Risk score. C ROC analysis of Age, Grade, Stage, and Risk score. D ROC curves of Risk Score for 1, 3, and 5 years. E C curves for Age, Grade, Stage, and Risk score. F Norm plots for T, N, M, Age, Grade, Stage, and Risk score. G Column line calibration curve

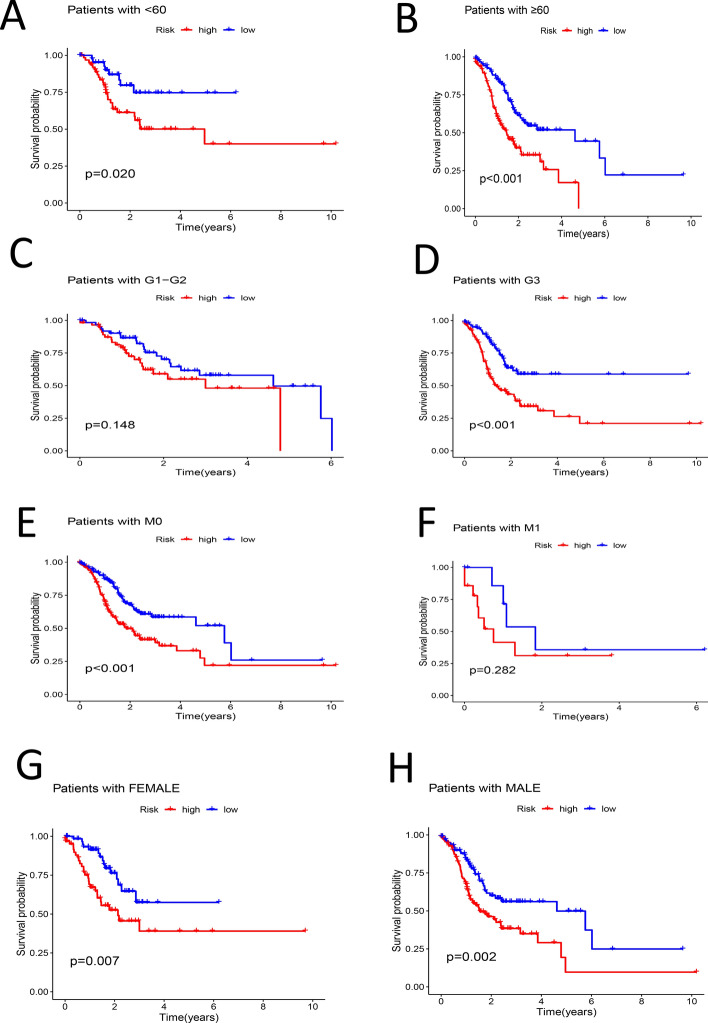

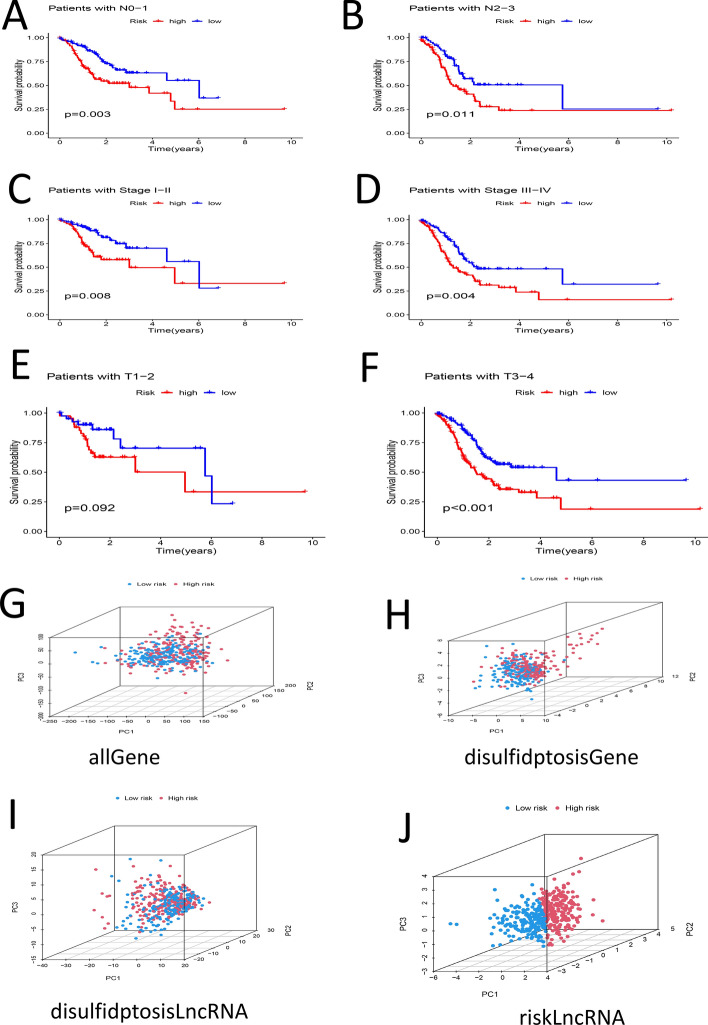

Patient ages were categorized, and samples were separated into groups of less than 60 years old and 60 years old or older. Survival analysis was conducted on both groups, revealing that the survival rate of the high-risk group was lower in each instance (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5A, B). Samples were categorized according to their G stage into G1-G2 and G3 groups, revealing notable differences in survival rates exclusively within the G3 group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5C, D). At the M stage, samples were categorized into M0 and M1 groups; notable differences in survival were observed in the M0 group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5E, F). The categorization of individuals into Female and Male groups demonstrated notable disparities in survival rates between high-risk and low-risk cohorts (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5G, H). The classification of N stage into N0-1 and N2-3 groups revealed notable disparities in survival rates (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6A, B). The classification of stages into Stage I-II and Stage III-IV revealed notable disparities in survival rates (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6C, D). Samples were categorized into T1-2 and T3-4 groups based on T stage; notable differences in survival rates were found exclusively in the T3-4 group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6E, F). PCA analysis was performed on various groups, highlighting the riskLncRNA group as having the highest degree of discrimination (Fig. 6G–J).

Fig. 5.

A Survival analysis between high- and low-risk groups in samples aged less than 60 years (P < 0.05). B Survival analysis between high- and low-risk groups in samples aged 60 years or older (P < 0.05). C Survival analysis of high- and low-risk groups in G1–G2 samples (P > 0.05). D Survival analysis of high- and low-risk groups in G3 samples (P < 0.05). E Survival analysis of high- and low-risk groups in M0 samples (P < 0.05). F Survival analysis between high- and low-risk groups in M1 samples (P > 0.05). G Survival analysis between high- and low-risk groups in Female samples (P < 0.05). H Survival analysis between high- and low-risk groups in Male samples (P < 0.05)

Fig. 6.

A Survival analysis between high- and low-risk groups in N0–N1 samples (P < 0.05). B Survival analysis between high- and low-risk groups in N2-N3 samples (P < 0.05). C Survival analysis of high- and low-risk groups in Stage I-II samples (P < 0.05). D Survival analysis of high- and low-risk groups in Stage III–IV samples (P < 0.05). E Survival analysis of high- and low-risk groups in T1–T2 samples (P > 0.05). F Survival analysis between high- and low-risk groups in T3-T4 samples (P < 0.05). G PCA distribution map for the total sample. H PCA distribution map for the DRG sample. I PCA distribution map for the DRL sample. J PCA distribution map for the RisklncRNA sample

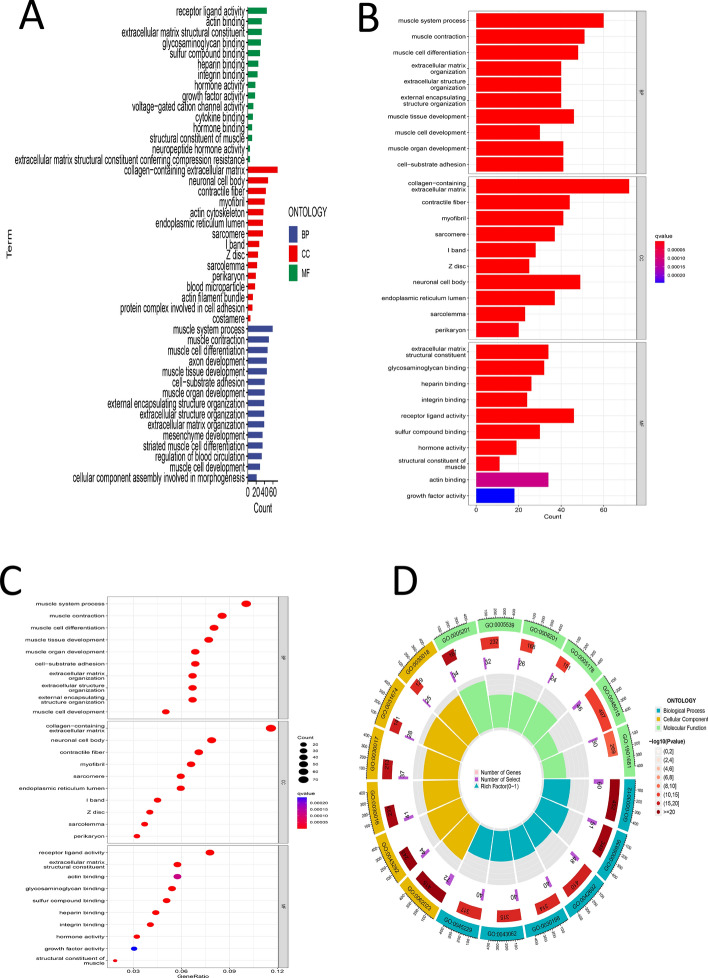

Results of differential expression, GO, KEGG, and GSEA for risk score-related samples

Differential analysis was conducted on samples related to risk scores to identify significantly differential genes. The GO analysis conducted on these genes revealed significant enrichment in various biological processes, including the muscle system process, muscle contraction, muscle cell differentiation, and extracellular matrix organization. The cellular components identified encompassed the collagen-containing extracellular matrix and contractile fibers. Additionally, the molecular functions exhibited enrichment for activities such as glycosaminoglycan binding and integrin binding (Fig. 7A–D), (Supplementary Material 1). Through KEGG analysis, major enrichments were identified in pathways including muscle cell cytoskeleton, dilated cardiomyopathy, and vascular smooth muscle contraction (Fig. 8A, B), (Supplementary Material 2). GSEA analysis primarily highlighted enrichments in pathways such as tight junction regulation, actin cytoskeleton regulation, and mitochondrial gene expression (Fig. 8C–F) (Supplementary Materials 3, 4). According to Supplementary Material 3, MYH10 was enriched in the tight junction and actin cytoskeleton regulation pathways, and based on Table 2, showed a significant positive correlation with AC107021.2 and AL359182.1.

Fig. 7.

A Bar chart of GO analysis results. B Bar chart of GO analysis results. C Bubble chart of GO analysis results. D Circle chart of GO analysis results

Fig. 8.

A Bar chart of KEGG analysis results. B Bubble chart of KEGG analysis results. C Distribution plot of high-risk group results from GSEA-GO analysis. D Distribution plot of low-risk group results from GSEA-GO analysis. E Distribution plot of high-risk group results from GSEA-KEGG analysis. F Distribution plot of low-risk group results from GSEA-KEGG analysis

Analysis of the correlation between risk score and GC immune characteristics

The analysis of TME scores revealed significant variations in StromalScore, ImmuneScore, and ESTIMATEScore between the high-risk and low-risk groups (Fig. 9A). The quantification and representation of 22 distinct immune cell types were depicted in a bar chart (Fig. 9B). A differential analysis indicated notable differences in the abundance of plasma cells, activated memory CD4 T cells, resting NK cells, and M2 macrophages among the groups (P < 0.05), (Fig. 9C). The examination of 29 immune functions revealed notable variations in ten immune-related functions, such as APC co-inhibition and cytolytic activity (Fig. 9D) [24]. In examining the correlation between risk score and TMB, it was observed that TP53 displayed an elevated mutation rate within the high-risk cohort, while other genes demonstrated increased mutation rates in the low-risk cohort (Fig. 10A, B). Significant variations in TMB were detected between the high-risk and low-risk cohorts (Fig. 10C). Survival analysis revealed notable differences in survival rates between the high and low TMB groups (Fig. 10D). Stratified survival analysis categorized high and low TMB samples into four distinct subgroups, demonstrating a reduced survival rate for the high-risk group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 10E). The TIDE analysis revealed elevated scores and an increased likelihood of immune evasion within the high-risk cohort (P < 0.05) (Fig. 10F).

Fig. 9.

A Violin plot of TME-score in high- and low-risk groups. B Bar chart of the percentage distribution of immune cells in high- and low-risk groups. C Box plot of the difference analysis of immune cells in high- and low-risk groups. D Box plot of the difference analysis of immune functions in high- and low-risk groups. (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001)

Fig. 10.

A Waterfall plot of TMB in the high-risk group. B Waterfall plot of TMB in the low-risk group. C Violin plot of differential analysis of TMB between high- and low-risk groups (P < 0.05). D Survival analysis plot of samples with high and low TMB (P < 0.05). E Stratified survival analysis plot of samples with high and low TMB between high- and low-risk groups (P < 0.05). F Violin plot of differential analysis of TIDE between high- and low-risk groups (P < 0.05)

Sensitive drugs related to risk score

A P-value threshold (pFilter = 0.0000001) was set for screening sensitive drugs. Seven significantly sensitive drugs were ultimately identifieD 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU), Ceralasertib (AZD6738), BMS-345541, Oxaliplatin, Pevonedistat, Ulixertinib, Vinblastine (Fig. 11A–G). As shown in Fig. 11, these drugs were assigned higher scores at elevated risk levels; however, higher scores correlated inversely with sensitivity. Thus, these screened drugs may offer effective treatment for low-risk patients, supporting personalized treatment approaches for GC.

Fig. 11.

A Box plot of PC50 analysis for 5-Fluorouracil (P < 0.000000000000001). B Box plot of PC50 analysis for AZD6738 (P < 0.000000000000001). C Box plot of PC50 analysis for BMS-345541 (P < 0.000000000000001). D Box plot of PC50 analysis for Oxaliplatin (P < 0.000000000000001). E Box plot of PC50 analysis for Pevonedistat (P < 0.000000000000001). F Box plot of PC50 analysis for Ulixertinib (P < 0.000000000000001). G Box plot of PC50 analysis for Vinblastine (P < 0.000000000000001)

Discussion

GC plays a crucial role in the overall cancer burden worldwide, exhibiting notable rates of incidence and mortality [25]. Even with advancements in diagnostic and therapeutic methods, the outlook for numerous patients continues to be poor [26]. Consequently, it is essential to pinpoint new biomarkers and create predictive models to enhance treatment results and prognostic precision.

Comprehensive studies have indicated a role for LncRNA in numerous pathological mechanisms, implying that its dysregulation could be associated with cancer progression [9]. Furthermore, the phenomenon of ferroptosis has shown a growing association with the prognosis of GC [27–29].

In this study, disulfidptosis and LncRNAs were combined to identify accurate prognostic signatures related to DRLs and novel therapeutic targets. Using a P-value threshold of < 0.01, over 200 calculations were conducted based on screened DRLs, identifying 201 initial GC prognostic signatures. Through survival analysis, only 23 signatures met the criteria. Further refinement through clinical statistics analysis, with a threshold of P > 0.05, reduced this number to 17. Using ROC analysis with a criterion of Risk AUC greater than age, gender, grade, and stage, the number was narrowed to 14 signatures. Finally, PCA analysis with the discriminative power of 3D PCA for riskLncRNA as the criterion retained one signature (Fig. 2D). This study introduced a stringent multi-stage screening process to select the most promising DRL-related prognostic signature for GC under various conditions.

By examining the GC prognosis model related to DRLs, through difference analysis, GO, KEGG, and GSEA, the relationship between model LncRNAs and disulfide death genes was determined (Fig. 2E). Analyses suggest that AC107021.2 and AL359182.1 could regulate pathways like TIGHT JUNCTION and REGULATION OF ACTIN CYTOSKELETON through positive regulation of MYH10, impacting GC prognosis. TIGHT JUNCTION has been linked to various cancers such as liver [30], gastrointestinal tumors [30], oral [31], bladder [32], and ovarian cancer [33], and is associated with tumor invasion and metastasis [31]. Claudin 6 has emerged as a promising therapeutic target in gastric adenocarcinoma, affecting prognosis via the tight junction pathway [34]. Conversely, a low expression of Claudin 4 promotes lymphangiogenesis, which facilitates tumor invasion through the same pathway [35].MICAL1 has been recognized as a facilitator of GC cell migration by influencing the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton [36]. Extracts from Celastrus orbiculatus Thunb have demonstrated the ability to impede the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis in GC cells through a comparable mechanism [37]. The lncRNA AC107021.2 has been linked to the prognosis of GC [38], whereas AL359182.1 has recently emerged as a potential prognostic marker and therapeutic target for GC, although additional research is necessary to validate its function. Thus, AL359182.1 and AC107021.2 may influence GC prognosis by regulating the MYH10/TIGHT JUNCTION or MYH10/REGULATION OF ACTIN CYTOSKELETON signaling axes.While direct evidence of MYH10 in gastric cancer (GC) remains limited, MYH10 (non-muscle myosin II heavy chain) is a key regulator of cytoskeletal dynamics, governing processes such as cell migration, polarization, and cytokinesis (Wu, Mingfang e.g. [39], Technology in cancer research & treatment vol. 23 (2024)). Our GO/GSEA analyses revealed significant enrichment of MYH10 in tight junction and actin cytoskeleton regulation pathways (Fig. 8C–F). This aligns with its established role in stabilizing cell–cell junctions and driving cytoskeletal remodeling, which may facilitate tumor invasion and immune evasion in GC.

This study conducted a stratified analysis of 14 clinical factors, among which no significant differences in survival were observed for 2 factors, while significant differences were noted for the remaining 12 factors. This demonstrates that a GC prognosis model based on DRLs can provide more accurate personalized predictions for patient outcomes.

The examination of the tumor microenvironment in relation to GC prognosis has revealed notable differences in TME scores when comparing high-risk and low-risk groups (P < 0.05). Inflammatory biomarkers have emerged as clinically significant predictors of survival outcomes in malignancies [40]. A variety of immune cells exhibited significant variations, such as M2 macrophages, mast cells, MHC class I, neutrophils, T helper cells, Th1 and Th2 cells, Type II IFN response, cytolytic activity, and APC co-inhibition [24]. The low-risk group exhibited a greater prevalence of activated memory CD4 T cells, which correlate with better prognoses. The CD36-BATF2/MYB axis, which modulates the expression of these T cells, seems to impact GC prognosis [40], highlighting their significance in disease progression. Resting NK cells, recognized for their cytotoxic capabilities against GC cells [41], exhibited a higher prevalence in the low-risk group, indicating a potential protective influence on prognosis. In contrast, M2 macrophages, known for their secretion of chitinase 3-like protein 1 (CHI3L1) that facilitates GC cell metastasis [42], were primarily identified in the high-risk group, suggesting a possible risk factor for unfavorable outcomes [43]. The glutamine-enriched metabolic microenvironment drives M2 macrophage polarization, thereby promoting trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive gastric carcinomas [44].This is consistent with the pro-tumorigenic properties attributed to M2 macrophages [45]. The association of AL359182.1 and AC107021.2 with MYH10-driven pathways (Fig. 3J–L) suggests that MYH10 may influence GC prognosis by enhancing metastatic potential or reshaping the tumor microenvironment (M2 macrophage infiltration in high-risk groups, Fig. 9C). Targeting M2 polarization (e.g., via 5-Fluorouracil or immune checkpoint inhibitors) may sensitize tumors to disulfidptosis-inducing therapies, as low-risk GC patients with reduced M2 infiltration show better response to immunotherapy [46].This hypothesis is further supported by the correlation between MYH10 and immune-suppressive features (e.g., elevated TIDE scores, Fig. 10F). Moreover, mast cells, found in higher numbers in the high-risk group, are believed to promote GC development through the IL-33/mast cell/IL-2 and TNF-α-PD-L1 pathways, further suggesting their role as a risk factor [46]. The established prognostic model is shown to effectively evaluate the efficacy of immunotherapy in treating GC [47]. Ye, Bicheng et al. [48] demonstrated that the Sig subgroup displayed significant immune cell infiltration and elevated tumor immunogenicity, suggesting improved responsiveness to immunotherapy. In contrast, the high-risk group exhibited diminished immune activity and mechanisms of immune evasion. These findings highlight a critical divergence in immune dynamics between subgroups, positioning this axis as a promising research direction for optimizing immunotherapy strategies in similar contexts.

In this study, the prediction model identified drugs potentially more effective for GC treatment, including: 5-FU, Ceralasertib (AZD6738), BMS-345541, Oxaliplatin, Pevonedistat, Ulixertinib, and Vinblastine [49]. 5-FU, used to treat GC, may reduce multidrug resistance when combined with allicin, and is believed to inhibit the carcinogenic effects of GC cells by down-regulating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [50]. This drug was found to be more sensitive in the low-risk group. The combination of AZD6738 and durvalumab shows promise in treating refractory advanced GC, though more research is needed as studies are limited [51]. Oxaliplatin, commonly used in combination with S-1, demonstrates efficacy in advanced GC treatment. Pevonedistat, used with capecitabine and oxaliplatin, requires further study to assess its long-term effects. Ulixertinib shows potential against NRAS and BRAF V600 and non-V600 mutant solid malignancies, but its effectiveness in GC still requires verification [52]. Similarly, more research on Vinblastine’s role in GC treatment is needed [52]. This signature model effectively identifies drugs sensitive to GC treatment, underscoring its clinical significance for personalized therapy [53], although further experimental validation is required. Literature review found that only two studies [54, 55] reported that the high expression level of AL359182.1 was significantly associated with poor OS in GC patients. Therefore, the potential molecular mechanism of AL359182.1 needs further experimental verification to clarify its specific role in the progression of gastric cancer.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the dataset included 373 gastric cancer samples and 32 normal tissues from TCGA, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to more diverse populations. Larger patient cohorts are needed to validate and strengthen these conclusions. Second, the newly developed four-lncRNA prognostic signature has not yet been externally validated. Prospective clinical studies are necessary to confirm its predictive value and clinical utility. Third, although AL359182.1 was identified as a potential therapeutic target, its functional role remains unclear. Further studies are required to explore its interaction with MYH10 and its potential relevance to gastric cancer therapy. Fourth, although the sensitivity of seven drugs was evaluated in relation to the risk score, further studies are needed to validate the predictive value of the risk score for these drugs in clinical trials.

Conclusion

Prognostic stratification

The four-lncRNA signature (PINK1-AS, AC107021.2, AL359182.1, AC009486.1) provides a robust tool for risk stratification in GC patients. Clinically, this model could guide personalized surveillance schedules or adjuvant therapy decisions, particularly for high-risk patients with poor survival outcomes (e.g., 5-year AUC > 0.6, Fig. 4D).

Therapeutic targeting

AL359182.1, identified as a novel prognostic marker, represents a potential therapeutic target. Inhibiting its interaction with MYH10-driven pathways (e.g., actin cytoskeleton remodeling) may suppress metastasis, offering a rationale for drug development or repurposing (e.g., combining with screened agents like AZD6738 or 5-FU, Fig. 11).

Immunotherapy optimization

The risk model’s correlation with immune features (e.g., M2 macrophages, cytolytic activity, Fig. 9C, D) could aid in predicting immunotherapy response. High-risk patients with elevated TIDE scores (Fig. 10F) may benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors to counteract evasion mechanisms.

Translational next steps

Future clinical studies should validate this signature in prospective cohorts and explore MYH10-targeted therapies in combination with existing regimens (e.g., platinum-based chemotherapy).

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Study design and data collection: JY (Jing Yu) and LKY (Longkuan Yin); Data analysis and interpretation: ML (Min Li),QL (Qian Li), XZQ (Xiangzhi Qin), and LQ (Long Qin); Manuscript drafting: JY (Jing Yu); Critical revision:YHT (Yunhong Tian). All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in this study are publicly available in the TCGA repository (https://www.cancer.gov/tcga). Data is also provided within the supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jing Yu, Longkuan Yin and Min Li have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van Grieken NC, Lordick F. Gastric cancer. Lancet (London, England). 2020;396:635–48. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chia NY, Tan P. Molecular classification of gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:763–9. 10.1093/annonc/mdw040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang X, et al. Temporal trend of gastric cancer burden along with its risk factors in China from 1990 to 2019, and projections until 2030: comparison with Japan, South Korea, and Mongolia. Biomarker Res. 2021;9:84. 10.1186/s40364-021-00340-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu SL, Zhang Y, Fu Y, Li J, Wang JS. Gastric cancer incidence, mortality and burden in adolescents and young adults: a time-trend analysis and comparison among China, South Korea Japan and the USA. BMJ Open. 2022;12: e061038. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-061038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan WL, He Y, Xu RH. Gastric cancer treatment: recent progress and future perspectives. J Hematol Oncol. 2023;16:57. 10.1186/s13045-023-01451-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sexton RE, AlHallak MN, Diab M, Azmi AS. Gastric cancer: a comprehensive review of current and future treatment strategies. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020;39:1179–203. 10.1007/s10555-020-09925-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan YT, et al. LncRNA-mediated posttranslational modifications and reprogramming of energy metabolism in cancer. Cancer Commun (London, England). 2021;41:109–20. 10.1002/cac2.12108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guan J, et al. Babao Dan inhibits lymphangiogenesis of gastric cancer in vitro and in vivo via lncRNA-ANRIL/VEGF-C/VEGFR-3 signaling axis. Biomed Pharmacotherapy. 2022;154: 113630. 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie Y, et al. LncRNA SNHG3 promotes gastric cancer cell proliferation and metastasis by regulating the miR-139-5p/MYB axis. Aging. 2021;13:25138–52. 10.18632/aging.203732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mei J, et al. LncRNA SNHG6 knockdown inhibits cisplatin resistance and progression of gastric cancer through miR-1297/BCL-2 axis. 2021. Biosci Rep. 10.1042/bsr20211885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu X, et al. Actin cytoskeleton vulnerability to disulfide stress mediates disulfidptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2023;25:404–14. 10.1038/s41556-023-01091-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X, et al. Actin cytoskeleton vulnerability to disulfide stress mediates disulfidptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2023. 10.1038/s41556-023-01091-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang T, et al. Disulfidptosis classification of hepatocellular carcinoma reveals correlation with clinical prognosis and immune profile. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;120: 110368. 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang J, et al. Identification of disulfidptosis-related subtypes, characterization of tumor microenvironment infiltration, and development of a prognosis model in breast cancer. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1198826. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1198826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun W, Zhang P, Ye B, Situ MY, Wang W, Yu Y. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts survival in patients with resected lung invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma. Transl Oncol. 2024;40: 101865. 10.1016/j.tranon.2023.101865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ye B, Fan J, Xue L, Zhuang Y, Luo P, Jiang A, Xie J, Li Q, Liang X, Tan J, Zhao S, Zhou W, Ren C, Lin H, Zhang P. iMLGAM: integrated machine learning and genetic algorithm-driven multiomics analysis for pan-cancer immunotherapy response prediction. Imeta. 2025;4(2): e70011. 10.1002/imt2.70011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomczak K, Czerwińska P, Wiznerowicz M. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): an immeasurable source of knowledge. Contemporary Oncol (Poznan, Poland). 2015;19:A68-77. 10.5114/wo.2014.47136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Q, Yin LK. Comprehensive analysis of disulfidptosis related genes and prognosis of gastric cancer. World J Clin Oncol. 2023;14:373–99. 10.5306/wjco.v14.i10.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hänzelmann S, Castelo R, Guinney J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinform. 2013;14:7. 10.1186/1471-2105-14-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen B, Khodadoust MS, Liu CL, Newman AM, Alizadeh AA. Profiling tumor infiltrating immune cells with CIBERSORT. Methods Mol Biol (Clifton NJ). 2018;1711:243–59. 10.1007/978-1-4939-7493-1_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu L, et al. Combination of TMB and CNA stratifies prognostic and predictive responses to immunotherapy across metastatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:7413–23. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-19-0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Addeo A, Friedlaender A, Banna GL, Weiss GJ. TMB or not TMB as a biomarker: that is the question. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;163: 103374. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun Y, et al. Metabolic reprogramming involves in transition of activated/resting CD4(+) memory T cells and prognosis of gastric cancer. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1275461. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1275461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Z, Liu Y, Niu X. Application of artificial intelligence for improving early detection and prediction of therapeutic outcomes for gastric cancer in the era of precision oncology. Semin Cancer Biol. 2023;93:83–96. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2023.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang K, Li X, Peng Y, Zhou Y. Comprehensive analysis of disulfidptosis-related LncRNAs in molecular classification, immune microenvironment characterization and prognosis of gastric cancer. Biomedicines. 2023. 10.3390/biomedicines11123165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan J, et al. Clinical significance of disulfidptosis-related genes and functional analysis in gastric cancer. J Cancer. 2024;15:1053–66. 10.7150/jca.91796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu X, Ou J. The development of prognostic gene markers associated with disulfidptosis in gastric cancer and their application in predicting drug response. Heliyon. 2024;10: e26013. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J, et al. Integrated analysis of disulfidptosis-related immune genes signature to boost the efficacy of prognostic prediction in gastric cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2024;24:112. 10.1186/s12935-024-03294-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeisel MB, Dhawan P, Baumert TF. Tight junction proteins in gastrointestinal and liver disease. Gut. 2019;68:547–61. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu YN, Deng MS, Liu YF, Yao J, Xiao ZY. Tight junction protein CLDN17 serves as a tumor suppressor to reduce the invasion and migration of oral cancer cells by inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Arch Oral Biol. 2022;133: 105301. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2021.105301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee YC, et al. High expression of tight junction protein 1 as a predictive biomarker for bladder cancer grade and staging. Sci Rep. 2022;12:1496. 10.1038/s41598-022-05631-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang L, Feng T, Spicer LJ. The role of tight junction proteins in ovarian follicular development and ovarian cancer. Reproduction (Cambridge, England). 2018;155:R183-r198. 10.1530/rep-17-0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon AG, et al. The tight junction protein claudin 6 is a potential target for patient-individualized treatment in esophageal and gastric adenocarcinoma and is associated with poor prognosis. J Transl Med. 2023;21:552. 10.1186/s12967-023-04433-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shareef MM, Radi DM, Eid AM. Tight junction protein claudin 4 in gastric carcinoma and its relation to lymphangiogenic activity. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2015;16:105–12. 10.1016/j.ajg.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ye F, et al. PlexinA1 promotes gastric cancer migration through preventing MICAL1 protein ubiquitin/proteasome-mediated degradation in a Rac1-dependent manner. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2024;1870: 167124. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2024.167124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang H, et al. Celastrus orbiculatus Thunb. extract inhibits EMT and metastasis of gastric cancer by regulating actin cytoskeleton remodeling. J Ethnopharmacol. 2023;301: 115737. 10.1016/j.jep.2022.115737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fan Z, Wang Y, Niu R. Identification of the three subtypes and the prognostic characteristics of stomach adenocarcinoma: analysis of the hypoxia-related long non-coding RNAs. Funct Integr Genomics. 2022;22:919–36. 10.1007/s10142-022-00867-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu M, et al. Gastric cancer signaling pathways and therapeutic applications. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2024;23:15330338241271936. 10.1177/15330338241271935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang Q, et al. CD36-BATF2\MYB axis predicts anti-PD-1 immunotherapy response in gastric cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19:4476–92. 10.7150/ijbs.87635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mimura K, et al. Therapeutic potential of highly cytotoxic natural killer cells for gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:1390–8. 10.1002/ijc.28780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Y, Zhang S, Wang Q, Zhang X. Tumor-recruited M2 macrophages promote gastric and breast cancer metastasis via M2 macrophage-secreted CHI3L1 protein. J Hematol Oncol. 2017. 10.1186/s13045-017-0408-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li W, et al. Gastric cancer-derived mesenchymal stromal cells trigger M2 macrophage polarization that promotes metastasis and EMT in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:918. 10.1038/s41419-019-2131-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu X, et al. Glutamine metabolic microenvironment drives M2 macrophage polarization to mediate trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive gastric cancer. Cancer Commun (London, England). 2023;43:909–37. 10.1002/cac2.12459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mi T, Kong X, Chen M, Guo P, He D. Inducing disulfidptosis in tumors: potential pathways and significance. MedComm (2020). 2024;5(11): e791. 10.1002/mco2.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hardaker EL, Sanseviero E, Karmokar A, et al. The ATR inhibitor ceralasertib potentiates cancer checkpoint immunotherapy by regulating the tumor microenvironment. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):1700. 10.1038/s41467-024-45996-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lv Y, Zhao Y, Wang X, et al. Increased intratumoral mast cells foster immune suppression and gastric cancer progression through TNF-α-PD-L1 pathway. J Immunotherapy Cancer. 2020. 10.1136/jitc-2020-0530-3corr1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ye B, et al. Navigating the immune landscape with plasma cells: a pan-cancer signature for precision immunotherapy. BioFactors (Oxford England). 2025;51(1): e2142. 10.1002/biof.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khakbaz P, Panahizadeh R, Vatankhah MA, Najafzadeh N. Allicin reduces 5-fluorouracil-resistance in gastric cancer cells through modulating MDR1, DKK1, and WNT5A expression. Drug Res. 2021;71:448–54. 10.1055/a-1525-1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou H, et al. Loganetin and 5-fluorouracil synergistically inhibit the carcinogenesis of gastric cancer cells via down-regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:13715–26. 10.1111/jcmm.15932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kwon M, et al. Phase II study of ceralasertib (AZD6738) in combination with durvalumab in patients with advanced gastric cancer. J Immunotherapy Cancer. 2022. 10.1136/jitc-2022-005041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang X, et al. Perioperative or postoperative adjuvant oxaliplatin with S-1 versus adjuvant oxaliplatin with capecitabine in patients with locally advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma undergoing D2 gastrectomy (RESOLVE): an open-label, superiority and non-inferiority, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:1081–92. 10.1016/s1470-2045(21)00297-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sullivan RJ, et al. First-in-class ERK1/2 inhibitor Ulixertinib (BVD-523) in patients with MAPK mutant advanced solid tumors: results of a phase I dose-escalation and expansion study. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:184–95. 10.1158/2159-8290.cd-17-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wei J, Zeng Y, Gao X, Liu T. A novel ferroptosis-related lncRNA signature for prognosis prediction in gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):1221. 10.1186/s12885-021-08975-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yi C, Zhang X, Chen X, Huang B, Song J, Ma M, Yuan X, Zhang C. A novel 8-genome instability-associated lncRNAs signature predicting prognosis and drug sensitivity in gastric cancer. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2022;36:3946320221103195. 10.1177/03946320221103195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this study are publicly available in the TCGA repository (https://www.cancer.gov/tcga). Data is also provided within the supplementary information files.