Abstract

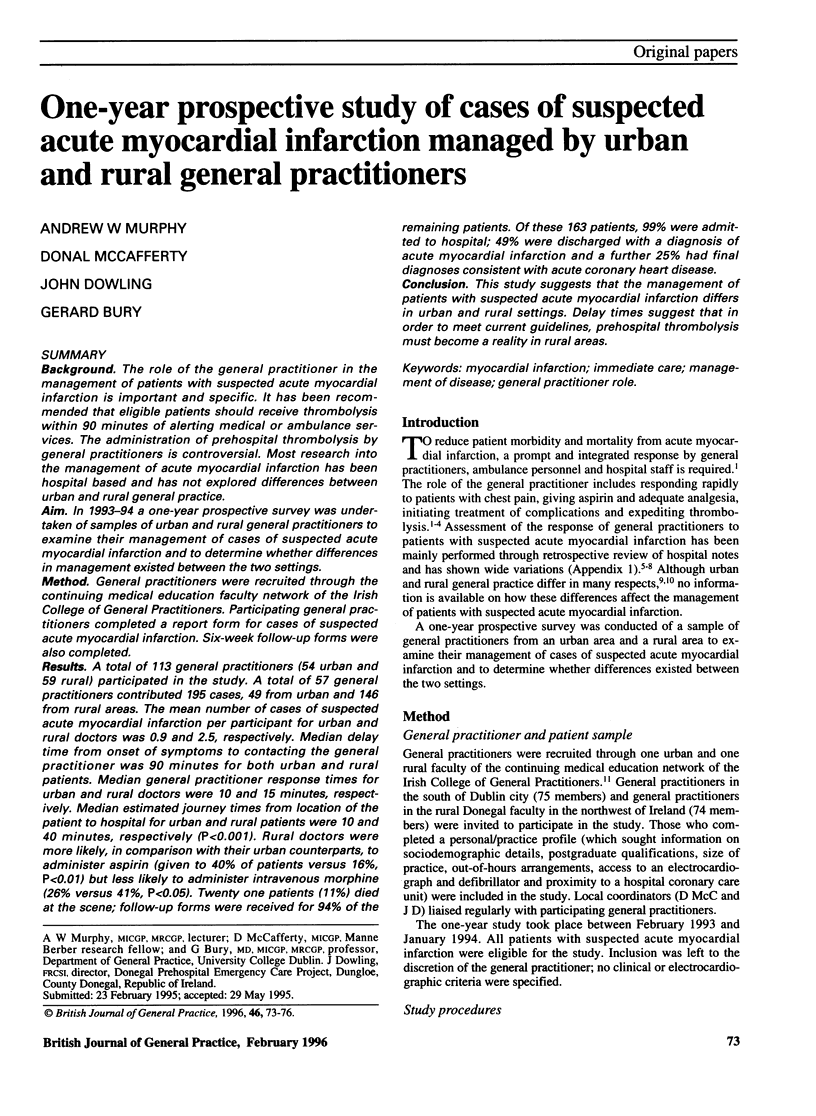

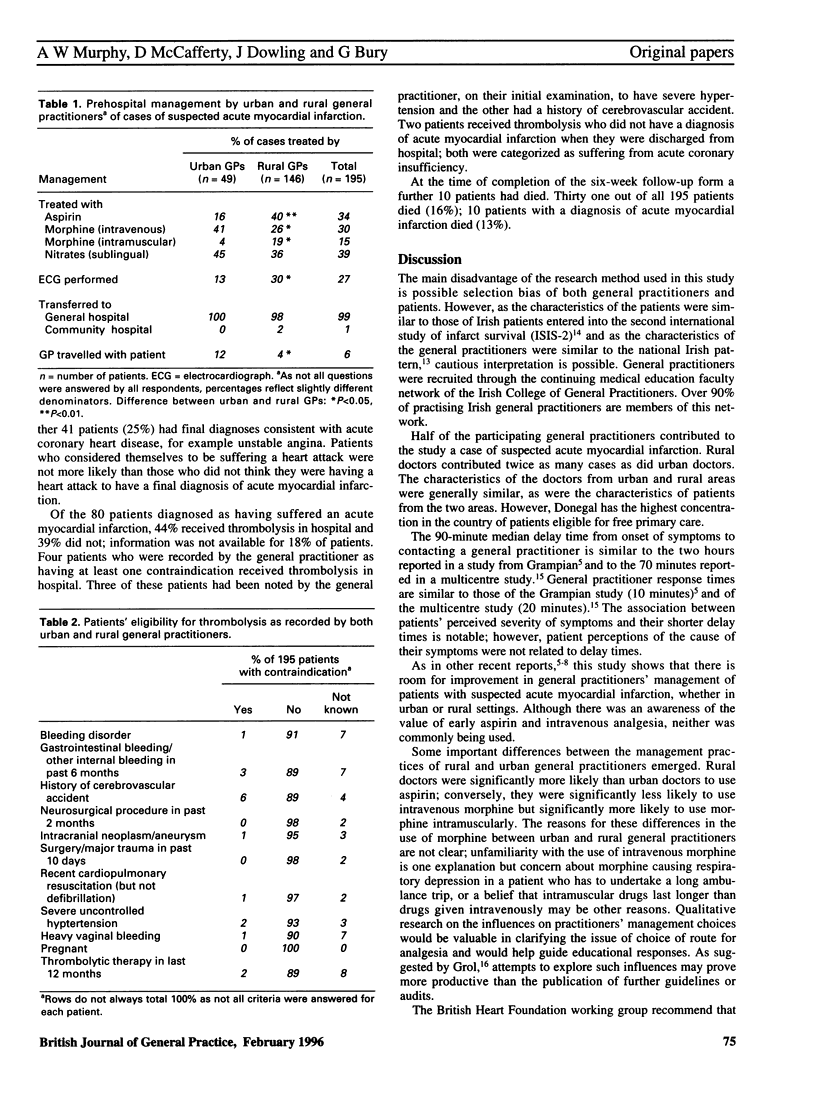

BACKGROUND: The role of the general practitioner in the management of patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction is important and specific. It has been recommended that eligible patients should receive thrombolysis within 90 minutes of alerting medical or ambulance services. The administration of prehospital thrombolysis by general practitioners is controversial. Most research into the management of acute myocardial infarction has been hospital based and has not explored differences between urban and rural general practice. AIM: In 1993-94 a one-year prospective survey was undertaken of samples of urban and rural general practitioners to examine their management of cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction and to determine whether differences in management existed between the two settings. METHOD: General practitioners were recruited through the continuing medical education faculty network of the Irish College of General Practitioners. Participating general practitioners completed a report form for cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction. Six-week follow-up forms were also completed. RESULTS: A total of 113 general practitioners (54 urban and 59 rural) participated in the study. A total of 57 general practitioners contributed 195 cases, 49 from urban and 146 from rural areas. The mean number of cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction per participant for urban and rural doctors was 0.9 and 2.5, respectively. Median delay time from onset of symptoms to contacting the general practitioner was 90 minutes for both urban and rural patients. Median general practitioner response times for urban and rural doctors were 10 and 15 minutes, respectively. Median estimated journey times from location of the patient to hospital for urban and rural patients were 10 and 40 minutes, respectively (P<0.001). Rural doctors were more likely, in comparison with their urban counterparts, to administer aspirin (given to 40% of patients versus 16%, P<0.01) but less likely to administer intravenous morphine (26% versus 41%, P<0.05). Twenty one patients (11%) died at the scene; follow-up forms were received for 94% of the remaining patients. Of these 163 patients, 99% were admitted to hospital; 49% were discharged with a diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction and a further 25% had final diagnoses consistent with acute coronary heart disease. CONCLUSION: This study suggests that the management of patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction differs in urban and rural settings. Delay times suggest that in order to meet current guidelines, prehospital thrombolysis must become a reality in rural areas.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Birkhead J. S. Time delays in provision of thrombolytic treatment in six district hospitals. Joint Audit Committee of the British Cardiac Society and a Cardiology Committee of Royal College of Physicians of London. BMJ. 1992 Aug 22;305(6851):445–448. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6851.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland M. William Pickles Lecture 1991. My brother's keeper. Br J Gen Pract. 1991 Jul;41(348):295–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J. Rural general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1994 Sep;44(386):388–389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol R. Implementing guidelines in general practice care. Qual Health Care. 1992 Sep;1(3):184–191. doi: 10.1136/qshc.1.3.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannaford P. C., Waine C. Practice policies for responding to patients with chest pain. Br J Gen Pract. 1994 May;44(382):195–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannaford P., Vincent R., Ferry S., Hirsch S., Kay C. Assessment of the practicality and safety of thrombolysis with anistreplase given by general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 1995 Apr;45(393):175–179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert P. Suspected myocardial infarction and the GP. BMJ. 1994 Mar 19;308(6931):734–735. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6931.734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketley D., Woods K. L. Impact of clinical trials on clinical practice: example of thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1993 Oct 9;342(8876):891–894. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91945-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGowan G. A., O'Callaghan D., Horgan J. H. Medical management of acute myocardial infarction in Ireland: information from the Second International Study of Infarct Survival (ISIS-2). Ir J Med Sci. 1991 Nov;160(11):347–349. doi: 10.1007/BF02957892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher M., Johnson N. Use of aspirin by general practitioners in suspected acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1994 Mar 19;308(6931):760–760. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6931.760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy A. W., Bury G., Dowling E. J. Teaching immediate cardiac care to general practitioners: a faculty-based approach. Med Educ. 1995 Mar;29(2):154–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1995.tb02820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy A. W., Power R., Ungruh K., Bury G. Pre-hospital management of acute myocardial infarction. Ir J Med Sci. 1992 Oct;161(10):593–596. doi: 10.1007/BF02942365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawles J. Attitudes of general practitioners to prehospital thrombolysis. BMJ. 1994 Aug 6;309(6951):379–382. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6951.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawles J. What should be the general practitioner's role in early management of acute myocardial infarction? Br J Gen Pract. 1995 Apr;45(393):171–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Round A., Marshall A. J. Survey of general practitioners' prehospital management of suspected acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1994 Aug 6;309(6951):375–376. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6951.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt I. S., Franks A. J., Sheldon T. A. Rural health and health care. BMJ. 1993 May 22;306(6889):1358–1359. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6889.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston C. F., Penny W. J., Julian D. G. Guidelines for the early management of patients with myocardial infarction. British Heart Foundation Working Group. BMJ. 1994 Mar 19;308(6931):767–771. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6931.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyllie H. R., Dunn F. G. Pre-hospital opiate and aspirin administration in patients with suspected myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1994 Mar 19;308(6931):760–761. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6931.760a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]