Abstract

Background

Palliative care is crucial for enhancing the quality of life for terminally ill patients, like those with cancer, but only 14% of those in need receive it, especially in resource-limited areas like Papua New Guinea (PNG). In 2018, PNG reported 7,477 cancer deaths and 11,913 new cases, with a projected 79% increase in patients by 2040. Nurses are vital to palliative care, yet gaps in competencies, particularly in pain management, affect care quality. This study aims to evaluate nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and competencies in palliative care in PNG, considering the unique challenges posed by limited resources and cultural factors.

Method

A mixed-method research design was employed, combining quantitative and qualitative approaches. Quantitative phase involved a survey of 150 registered nurses from two major hospitals in PNG, using simple random sampling. Data were collected via standardized questionnaires assessing knowledge, attitudes, and competencies in palliative care. Qualitative phase included semi-structured interviews with 20 nurses, selected through purposive sampling, to explore their experiences and challenges. Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS, while qualitative data were analyzed thematically using NVivo. The study adhered to the GRAMMS checklist to ensure methodological rigor.

Result

Nurses demonstrated a moderate level of knowledge in palliative care (mean score = 3.34, SD = 0.69), lowest scores in pain management (mean = 2.82, SD = 0.49). Attitudes toward palliative care were moderately positive (mean = 2.22, SD = 1.12), and high confidence in providing end-of-life care (mean = 4.51, SD = 0.66). Competency levels were modest (mean = 3.59, SD = 0.82), with the highest proficiency in assessing physical symptoms (mean = 4.67, SD = 0.67) and lowest in involving community clergy support (mean = 3.19, SD = 1.01).

Conclusion

The study highlights the essential role of nurses in palliative care in Papua New Guinea (PNG) and identifies gaps in knowledge and skills related to pain management. It recommends targeted training, resource allocation, and cultural sensitivity training to improve care delivery. The findings underscore the need for policy development and interdisciplinary collaboration to address challenges in resource-constrained settings.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12913-025-13311-6.

Keywords: Palliative care, Papua new guinea, Nurses, Knowledge, Attitudes, Competencies, Pain management, Cultural sensitivity, Resource limitations, Interdisciplinary collaboration.

Introduction

Palliative care is a critical component of healthcare, aiming to alleviate suffering and enhance the quality of life for patients and their families facing serious health-related suffering [1–4]. It aims to alleviate suffering and enhance the quality of life for both patients and their families [5]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a significant gap exists between the need for and the provision of palliative care globally [3, 4, 6–8]. Prioritizing palliative care services is essential for reducing preventable suffering and improving the quality of life for individuals and their families affected by advanced chronic or life-limiting illnesses [4, 6, 9–12]. The situation is particularly challenging in Papua New Guinea (PNG), where healthcare resources are constrained, and the burden of cancer is substantial [13–15]. In 2018, PNG recorded approximately 7,477 cancer-related deaths and 11,913 new cancer cases [4, 16–19]. With the number of cancer patients in PNG expected to increase by 79% by 2040, the need for effective palliative care services in the region is increasingly urgent [4, 20, 21]. Nurses play a pivotal role in palliative care, often serving as the first point of contact for patients with life-threatening illnesses [4, 16, 17, 20]. However, there are notable gaps in critical competencies, such as medication administration and pain assessment, as nurses’ knowledge and skills in palliative care are frequently derived from practical experience rather than formal education [21–25]. It is important to consider the role of education and training, including the different levels of palliative care provision and any prior training nurses may have received [26, 27] This lack of formal training can hinder the delivery of high-quality palliative care, particularly in resource-constrained settings like PNG. Previous studies have explored the influence of sociodemographic factors such as age, gender, and marital status on nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and competencies in palliative care. While some studies suggest that demographic factors may influence training outcomes and care delivery in resource-rich healthcare settings [23, 28–30], others have found no significant correlation between these factors and palliative care competencies [31, 32]. For example, Bennett et al. (2009) found that health literacy, rather than demographic factors, played a more significant role in shaping healthcare outcomes [31]. Similarly, Koffman et al. (2007) reported that awareness of palliative care services was not significantly influenced by demographic factors such as marital status [29]. These findings suggest that while demographic factors may play a role in some contexts, they are not universally predictive of palliative care competencies. This study aims to further explore these relationships in the context of Papua New Guinea, where resource constraints and cultural factors may influence the delivery of palliative care differently than in more developed settings. The primary objective of this study is to assess nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and competencies in providing holistic palliative care management in PNG. By employing a mixed-methods approach, this research aims to evaluate nurses’ attitudes and knowledge while exploring the factors that influence these aspects in the context of palliative care [23, 30]. The findings of this study are expected to provide valuable insights for healthcare managers and policymakers, enabling them to design targeted training programs that address specific knowledge and competency gaps in palliative care [33]. In summary, this study seeks to contribute to the advancement of palliative care education and practice in PNG by identifying the unique challenges faced by nurses in resource-limited settings. By addressing these challenges, the study aims to improve the quality of palliative care services, ultimately enhancing the quality of life for patients with terminal illnesses and their families [33].

Method

Study design

This study employed a convergent parallel mixed-methods design. This approach was selected because neither quantitative nor qualitative methods alone could comprehensively address the complexity of assessing nurses’ palliative care knowledge, attitudes, and competencies in Papua New Guinea’s resource-limited context. Quantitative surveys provided statistical insights into knowledge levels and self-reported confidence, identifying measurable gaps. Simultaneously, qualitative interviews captured rich contextual insights into experiences, barriers, and cultural factors influencing care delivery. Data were collected concurrently but analyzed separately (SPSS for surveys; NVivo for thematic analysis of interviews). Findings were integrated during interpretation via triangulation to identify convergence, divergence, and complementarity, generating nuanced meta-inferences.

Reporting guidelines

To ensure methodological rigor, this study followed the Good Reporting of a Mixed Methods Study (GRAMMS) checklist and the Reporting Consolidated Criteria for Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines. These guidelines were used to structure the reporting of the mixed-methods design, data collection, and analysis processes, see Appendix A [34].

Study setting and participants

The study was conducted at Port Moresby General Hospital and Angau Memorial Hospital in Papua New Guinea, selected for their high volume of cancer patients, making them suitable for examining nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and competencies in palliative care [35]. These institutions serve patients with palliative care needs as part of their routine nursing duties, particularly in oncology wards, and also in general wards due to factors such as treatment waiting times and limited bed space [35, 36]. There is a newly established palliative care ward in the hospital, separate from the oncology ward, although most nurses working in these wards primarily rely on their general nursing experience rather than specialized training [37]. The hospital has a church chaplain available for spiritual support [38]. The palliative care service is in the process of being integrated into the overall healthcare system, and while the Palliative Care Association is in the process of registering, Papua New Guinea has an established oncology society called PaNGONA [39]. The study is beginning to implement a multidisciplinary team approach to palliative care, involving collaboration among doctors, nurses, social workers, and chaplains to provide comprehensive care. Essential medicines for palliative care, including oral morphine, are included in the WHO Essential Medicines List, with Papua New Guinea primarily using 10 mg morphine injections and oral formulations [40]. Patients are typically admitted to the palliative care setting through oncology clinics and the main emergency admission protocol. Upon admission, patients undergo a comprehensive assessment that evaluates their physical, emotional, and psychosocial needs, aligning with WHO guidelines emphasizing pain management, symptom control, and overall quality of life [41]. Following the assessment, a tailored care plan is developed, involving the multidisciplinary team, in accordance with WHO recommendations for holistic palliative care [42, 43]. Most patients transition out of the palliative care setting to return home, often influenced by cultural beliefs that prioritize family care [13]. This transition can present challenges, as patients may experience neglect due to the minimal availability of community caregivers [44]. Efforts are needed to strengthen community support systems to better assist families in providing care for their loved ones [45]. To verify participants’ work history and experience in palliative care settings, data were obtained from the Human Resource Departments of both hospitals, focusing on their work location (e.g., oncology units, medical/Palliative wards) and their self-reported experience. Inclusion in the study was not solely based on the location of work, as palliative care needs can arise in various settings. Instead, direct experience in palliative care was explicitly required, confirmed through a combination of self-reporting and HR verification to ensure both inclusivity and exclusivity. This approach ensured that nurses with relevant experience were included, while those without direct palliative care involvement were excluded, regardless of their work location.

Recruitment and sampling

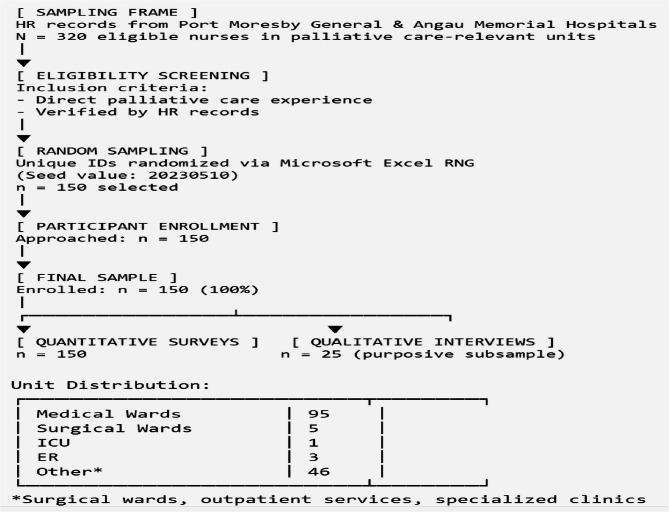

Participants were recruited using a combination of purposive sampling for the qualitative phase and simple random sampling for the quantitative phase. The sampling frame was established using HR department records from Port Moresby General and Angau Memorial Hospitals, identifying nurses in palliative care-relevant units. Unique participant IDs were randomized via Microsoft Excel’s RNG (seed documented). Despite achieving a 100% response rate (n = 150) through institutional support and personalized follow-ups, we acknowledge potential selection bias. Palliative care experience was verified through HR records and triangulated with knowledge assessments, though the Palliative Care Experience Scale (PCES) was not used due to contextual constraints. Underrepresentation of ICU/ER nurses (ICU = 0.7%, ER = 2%) limits generalizability to high-acuity settings. The “Other” category (30.7%) includes surgical, outpatient, and specialized clinic nurses. Figure 1 below illustrates the flow diagram to improve transparency. We have included a participant flow diagram detailing recruitment, inclusion, exclusion, and response tracking throughout the study phases.

Fig. 1.

Participant selection flow diagram

Quantitative phase

The required sample size was determined using the Krejcie and Morgan sample size determination table [46]. For a population of 150 registered nurses working in palliative care settings in PNG, a sample size of approximately 108 nurses was recommended, based on a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error. However, to enhance the representativeness of the sample and allow for more robust statistical analyses, a larger sample size of 150 nurses was selected. Simple random sampling was achieved by assigning each nurse a unique number and using a random number generator (Microsoft Excel) to select participants without replacement. This ensured that each nurse had an equal chance of being chosen, thereby increasing the validity and reliability of the research findings.

Qualitative phase

Purposive sampling was used to select 20 nurses with experience in end-of-life care, focusing on those from various specialties and levels of training. Participants were recruited based on their willingness to share their experiences and their ability to articulate their perspectives on palliative care. The inclusion criteria for the qualitative phase were the same as for the quantitative phase, ensuring consistency across both phases of the study.

Data collection process

Both quantitative and qualitative data collection techniques were employed.

Quantitative phase

A standardized questionnaire was distributed to assess nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and confidence in palliative care. The questionnaire included three main sections:

Demographic and Work-related Data Questionnaire: This section collected information on age, gender, marital status, education level, years of experience, and current area of work [47]. The standardized demographic questionnaires were adapted from Moreira et al. and were revised to ensure relevance and inclusivity for the current study setting in Papua New Guinea [48]. (See Appendix B for full questionnaires.)

Palliative Care Knowledge Questionnaire: A 10-item scale was developed specifically for this study to assess nurses’ knowledge of palliative care principles, including pain management, symptom control, and ethical considerations. The items were adopted from the Palliative Care Quiz for Nursing developed by Ross and McGuinness (1996) and were revised to ensure relevance and appropriateness for the context of Papua New Guinea [49]. It was used to assess participants’ understanding of palliative care principles. This helped confirm that participants had a baseline understanding of palliative care before their self-reported experience was considered valid. Each correct answer was scored 1 point, with a total score ranging from 0 to 10. The scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.855) [47, 50]. (See Appendix C for the full questionnaire.)

Nurses’ Palliative Attitude Scale: A 9-item Likert scale was used to evaluate nurses’ attitudes toward palliative care, with scores ranging from 9 to 45. This scale showed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.786) [51, 52],. The items were adopted from the Palliative Attitudes Scale (PCAC-9) developed by Perry et al. (2020) and revised to ensure relevance and suitability for the context of Papua New Guinea [53]. (See Appendix D for the full questionnaires.)

Confidence Scale: A 10-item Likert scale assessed nurses’ self-reported confidence in providing palliative care, with scores ranging from 10 to 50. The scale demonstrated acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.761) [54]. This scale was adapted from Parajuli et al. (2022), but it was revised to focus on confidence rather than competency, as the original questionnaire assessed confidence levels among oncology nurses [54]. (See Appendix E for the full questionnaires.). All instruments underwent cultural adaptation for PNG through expert consultation and pilot testing with 15 local nurses. Linguistic adjustments improved the clarity of palliative care concepts, pain management, and spiritual support terminology. Modified scales demonstrated acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.761–0.855) in our sample. While full psychometric validation was beyond scope, this process enhanced cultural relevance. Limitations regarding comprehensive validation are acknowledged in the Discussion.

Qualitative phase

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 nurses. The interview guide included eight open-ended questions exploring nurses’ attitudes, experiences, and challenges in providing palliative care (see Appendix F/G for the interview guide). The questions were designed to elicit rich, contextual insights into the nurses’ experiences, including their most unforgettable experiences (e.g., “Could you please share your most unforgettable experience related to providing palliative care?“). Participants expressed their opinions by responding to the eight open-ended, semi-structured questions on the questionnaire. Thematic analysis was then used to examine the written responses. Thematic saturation was determined iteratively: after each interview, transcripts were coded and compared to prior data, with saturation confirmed when no new themes emerged in three consecutive interviews. Additional illustrative quotes were incorporated per theme (e.g., “Lack of equipment and training hinders our ideal care level” [P7]), enhancing credibility and depth.

Data analysis

Quantitative Analysis: Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS version 26.0. Descriptive statistics (means, medians, standard deviations) were calculated to summarize the data. Inferential statistics (t-tests, ANOVA, regression analysis) were used to examine relationships between variables. Item analysis was performed to identify strengths and weaknesses in the knowledge questionnaire. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d for t-tests; η² for ANOVAs) will be reported alongside p-values to indicate practical significance.

Qualitative Analysis: Qualitative data were analyzed using NVivo software and manual coding. Thematic analysis, following Braun and Clarke’s six-step framework [55], was used to identify patterns and themes in the interview transcripts [56]. Emerging themes were reviewed and refined to ensure accuracy and relevance. To enhance the depth of the analysis, direct quotes from participants were incorporated into the results section, providing valuable insights into their experiences and perspectives.

Saturation determination**

After each interview, transcripts were coded and compared to prior data. Saturation was confirmed when three consecutive interviews yielded no new themes (achieved at Interview 15).

Integration of findings

Quantitative and qualitative findings were integrated through triangulation [57]. The research team compared and contrasted the two datasets to identify areas of convergence, divergence, and complementarity. This approach provided a comprehensive understanding of nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and confidence in palliative care, as well as the contextual factors influencing their practice.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Central South University (CSU)-Xiangya College of Nursing Department under ethical review number 2024WJ003. This approval facilitated the issuance of an official letter to the selected hospitals, Port Moresby General Hospital and Angau Memorial Hospital Health Bureau, requesting their permission and cooperation for the study with ethical review number EC#061. Approvals were also obtained from the participating hospitals.

In accordance with the declaration of Helsinki, all research involving human participants was conducted with the utmost respect for their rights, dignity, and welfare. Verbal consent was obtained from each participant, ensuring that they were adequately informed about the study’s purpose, procedures, risks, and benefits. Participants’ anonymity and confidentiality were maintained throughout the research process. They were informed of their right to decline participation or withdraw from the study at any stage without any repercussions. This study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the declaration of Helsinki, ensuring the protection and respect of all individuals involved in the research.

Results

Participant overview

A total of 150 registered nurses participated in the study, achieving a 100% response rate from Port Moresby General Hospital and Angau Memorial Hospital [manuscript data]. All participants met the inclusion criterion of having at least six months of experience in providing palliative care. There were no study dropouts, ensuring a complete dataset for analysis. To strengthen data integration, we employed Hong et al.‘s (2017) typology using comparison and assimilation strategies [58]. A joint display table (Table 11) aligns quantitative results (knowledge scores, competency levels) with qualitative themes and illustrative quotes, visually mapping areas of convergence, divergence, and complementarity. For example, low quantitative pain management scores were assimilated with qualitative reports of training gaps and resource constraints. This structured triangulation generated meta-inferences that deepen understanding of palliative care challenges beyond either dataset al.one. Participant Characteristics: Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. The majority were female (79.3%), with the 31–40 age group being the most prevalent (42.7%). A significant portion of participants were married (70.7%) and held a Registered Nurse qualification (89.3%). Most nurses worked in medical wards (63.3%), with 45.3% reporting 11 years or more of nursing experience. Educational backgrounds varied, with 36.0% holding a certificate, 30.0% a diploma, and 34.0% a degree.

Table 11.

Joint display of integrated quantitative and qualitative findings

| Quantitative Finding | Qualitative Theme | Illustrative Quote | Integration Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low pain management knowledge scores (35% correct) | Resource limitations in symptom control | “We often run out of even basic pain meds - sometimes we improvise with prayer” (P14) | Complementarity |

| High communication confidence (82% self-rated ≥ 4/5) | Cultural barriers in end-of-life discussions | “Families forbid us from mentioning death - they fear it invites evil spirits” (P09) | Divergence |

| Moderate competency in spiritual care (mean 3.1/5) | Integrating traditional beliefs | “We ask about clan rituals early - this opens doors for care” (P21) | Convergence |

| Low medication access scores (42% reported regular access) | Systemic supply chain failures | “The pharmacy stock is unpredictable; we might have morphine one week and none the next” (P07) | Complementarity |

| High value placed on family involvement (89% agreed) | Family as decision-makers in care | “The uncle or elder must approve every treatment; we cannot proceed without family consent” (P18) | Convergence |

| Low psychological support knowledge (28% correct) | Emotional burden and coping mechanisms | “We see so much suffering but have no training on how to help families grieve” (P05) | Complementarity |

| High positive attitudes toward palliative care (78% agreed it’s rewarding) | Motivation despite challenges | “Even with few resources, helping patients die with dignity gives me purpose” (P12) | Convergence |

| Underrepresentation of ICU/ER nurses (ICU = 0.7%, ER = 2%) | Workload disparities | “Emergency cases leave no time for palliative care - we’re just putting out fires” (P03) | Complementarity |

| Cultural barriers in pain assessment (mean score 2.4/5) | Spirituality and pain interpretation | “Some believe pain is punishment from ancestors - they refuse medication” (P16) | Complementarity |

Table 1.

Presents socio-demographic analysis

| Demographic Characteristics | Demographic data | Count | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 31 | 20.7 |

| Female | 119 | 79.3 | |

| Age | 21–30 years | 39 | 26.0 |

| 31–40 years | 64 | 42.7 | |

| 41–50 years | 30 | 20.0 | |

| 51–60 years | 17 | 11.3 | |

| Marital_Status | Single | 29 | 19.3 |

| Married | 106 | 70.7 | |

| Others | 15 | 10.0 | |

| Higest_Nursing_Qualification | Registered Nurse | 134 | 89.3 |

| Enrolled Nurse | 16 | 10.7 | |

| Years_of_Nursing_Experience | 1 year or less | 9 | 6.0 |

| 2–5 years | 27 | 18.0 | |

| 6–10 years | 46 | 30.7 | |

| 11 years or more | 68 | 45.3 | |

| Current_Area_of_Work | Medical ward | 95 | 63.3 |

| Surgical ward | 5 | 3.3 | |

| ICU | 1 | 0.7 | |

| ER | 3 | 2.0 | |

| Others | 46 | 30.7 | |

| Education_Level | Certificate | 54 | 36.0 |

| Diploma | 45 | 30.0 | |

| Degree | 51 | 34.0 |

Summary scale scores of palliative care knowledge, attitudes, and competence

Knowledge scale results

The total mean knowledge score was 3.34 (SD = 0.69), with highest proficiency in “Understanding of Palliative Care Concepts” (M = 3.56, SD = 0.32, η² = 0.18) and lowest in “Pain Management” (M = 2.82, SD = 0.49, d = 1.51 vs. concepts). Qualitative insights suggest resource limitations confound these scores: *"We rarely see advanced pain cases - only basic analgesics available” (P7) *. Attitude scores (M = 2.22, SD = 1.12) showed high confidence in end-of-life care (M = 4.51, d = 2.04 vs. overall), though cultural barriers emerged as potential confounders: “Families resist opioid use despite visible suffering” (P10). Competency scores (M = 3.59, SD = 0.82) peaked in “Assessing Physical Symptoms” (M = 4.67, η² = 0.22) and were lowest in “Involving Community Clergy Support” (M = 3.19, d = 1.81 vs. physical), reflecting systemic gaps in spiritual care integration (*"Hospital chaplains don’t understand ancestral rituals” - P17*). Community Clergy refers to religious leaders or spiritual advisors who are part of the patient’s community and provide spiritual support. This term is specific to PNG as the hospital has a church chaplain available for spiritual support [59]. No age/gender differences were found (all p > 0.05, d < 0.2), suggesting training should target al.l nurses equally. Table 2. Below show the knowledge scores with effect size comparisons.

Table 2.

Knowledge scores with effect size comparisons

| Dimension | Item Count | Mean Score (SD) | Comparison | Effect Size | Magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Knowledge | 10 | 3.34 ± 0.69 | - | - | - |

| Palliative Care Concepts | 4 | 3.56 ± 0.32 | vs. Pain Management | d = 1.51 | Large |

| Pain Management | 3 | 2.82 ± 0.49 | vs. Psychological | d = 1.32 | Large |

| Psychological/Spiritual Concerns | 3 | 3.42 ± 0.35 | vs. Concepts | d = 0.42 | Medium |

Effect sizes calculated using Cohen's d (group comparisons) and 𝜂2 (ANOVA). Magnitude thresholds: d=0.2 (small), 0.5 (medium), 0.8 (large); 𝜂2=0.01 (small), 0.06 (medium), 0.14 (large)

Attitude scale results

The overall mean attitude score was 2.22 (SD = 1.12), reflecting moderate comfort in discussing end-of-life issues. Nurses expressed exceptionally high confidence in end-of-life care (M = 4.51, SD = 0.66, d = 2.04 vs. overall [large effect]), though qualitative data revealed this confidence may reflect institutional expectations rather than actual preparedness: “We must appear strong for families even when unprepared” (P9). Attitudes toward palliative care goals were mixed, with the belief that palliative care prolongs dying showing moderate acceptance (M = 3.05, SD = 1.18, d = 0.74 vs. overall [medium effect]). Cultural barriers emerged as key confounders: “Families view stopping treatment as abandonment” (P14). No gender differences in confidence scores (t = 1.21, p = 0.227, d = 0.18 [small effect]). The table presents the attitude score with effect size magnitudes. Table 4 presents the attitude score with size magnitudes.

Table 4.

Competency scores with effect size magnitudes

| Dimension | M ± SD | Effect Size (d) | Magnitude | Qualitative Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Competency | 3.59 ± 0.82 | - | - | - |

| Physical Symptom Assessment | 4.67 ± 0.67 | 1.32 | Large | “Drilled in vital signs but not emotional needs” (P8) |

| Emotional Support | 3.99 ± 0.82 | 0.49 | Medium | “No training for family grief crises” (P12) |

| Clergy/Community Integration | 3.19 ± 1.01 | −0.49 | Medium | “Chaplains don’t know village mourning customs” (P17) |

| Care Plan Negotiation | 3.31 ± 0.99 | −0.34 | Small | “Families override patient wishes regularly” (P4) |

| Discussing Intervention Limits | 3.25 ± 0.98 | −0.41 | Small | “Seen as giving up hope” (P10) |

| Documenting Code Status | 3.25 ± 0.91 | −0.41 | Small | “Advanced directives aren’t culturally accepted” (P6) |

| Discharge Coordination | 3.71 ± 1.03 | 0.15 | Small | *"No community nurses for follow-up” (P15) * |

| Patient Advocacy | 4.19 ± 0.88 | 0.73 | Medium | “We fight for pain meds against pharmacy limits” (P3) |

| Culturally Sensitive Communication | 3.47 ± 1.01 | −0.15 | Small | *"800 languages - no training for this” (P11) * |

| Role Satisfaction | 4.57 ± 0.73 | 1.2 | Large | “Serving my people gives purpose” (P9) |

Effect sizes calculated as (Dimension Mean - Overall Mean)/Overall SD. Magnitude thresholds: |d|=0.2(small), 0.5(medium), 0.8(large). Qualitative insights from interview transcripts

*Effect size (d) indicates how many standard deviations a dimension is above/below the average competency. Negative values mark priority improvement areas

Table 3.

Attitude scores with effect size magnitudes

| Dimension | Item Count | M ± SD | Comparison | Effect Size | Magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Attitude | 9 | 2.22 ± 1.12 | - | - | - |

| Evaluative Dimensions | |||||

| Comfort Discussing Pain | 1 | 2.98 ± 1.31 | vs. Overall | d = 0.68 | Medium |

| Perceptions of Palliative Care | 1 | 1.77 ± 0.70 | vs. Overall | d = −0.40 | Small |

| Pain Management Priority | 1 | 1.83 ± 0.77 | vs. Overall | d = −0.35 | Small |

| Spiritual/Cultural Relevance | 1 | 1.80 ± 0.58 | vs. Overall | d = −0.38 | Small |

| Withdrawal of Aggressive Care | 1 | 2.09 ± 1.20 | vs. Overall | d = −0.12 | Negligible |

| Potency Dimensions | |||||

| Confidence in End-of-Life Care | 1 | 4.51 ± 0.66 | vs. Overall | d = 2.04 | Large |

| Beliefs About the Dying Process | 1 | 3.05 ± 1.18 | vs. Overall | d = 0.74 | Medium |

| Role in Discussing Prognosis | 1 | 3.93 ± 1.02 | vs. Overall | d = 1.53 | Large |

| Activity Dimension | |||||

| Focus on Curing Illnesses | 1 | 1.11 ± 0.32 | vs. Overall | d = −0.99 | Large |

Effect sizes calculated using Cohen’s d. Magnitude thresholds: d = 0.2(small), 0.5(medium), 0.8 (large). Negative values indicate lower scores than the overall mean

Competency scale results

The mean competency score was 3.59 (SD = 0.82), indicating modest self-reported proficiency. Nurses showed strongest competence in physical symptom assessment (M = 4.67, SD = 0.67, d = 1.32 vs. overall [large effect]), though qualitative data revealed this may reflect task-focused training: “We’re drilled in vital signs but not emotional needs” (P8). The lowest scores emerged in clergy/community integration (M = 3.19, SD = 1.01, d = −0.49 [medium effect]), with cultural mismatches identified as key barriers: “Hospital chaplains don’t understand village mourning customs” (P17). Table 4 below presents the competency findings scores with effect size magnitudes.

Summary of influence of sociodemographic characteristics on nurses’ knowledge, attitude, and competency

The analysis explored the impact of sociodemographic factors on nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and competencies in palliative care. No significant differences in knowledge scores were found based on gender, age, marital status, highest nursing qualification, years of experience, area of work, or educational level. Similarly, gender, age, marital status, and nursing qualification did not significantly affect nurses’ attitudes toward palliative care. However, years of experience showed marginal significance (F(3, 146) = 2.669, p = 0.050, η² = 0.052), indicating a small effect, with nurses having more experience reporting more favorable attitudes, as shown in Table 6. In terms of competency, years of nursing experience exhibited a significant positive effect (F(3, 146) = 3.646, p = 0.014, η² = 0.070), indicating a small-to-medium effect, with more experienced nurses demonstrating higher competency levels. Educational qualifications also showed significant differences, with degree holders achieving higher competency scores compared to those with certificates or diplomas. The examination of sociodemographic characteristics revealed no statistically significant variations in knowledge, attitudes, or competencies based on age, marital status, or gender. This suggests that these demographic factors do not significantly influence nurses’ understanding or delivery of palliative care. These findings align with previous studies that have similarly found no strong correlation between demographic factors such as marital status and palliative care competencies [29, 31]. However, the positive correlation between years of experience and competency levels (η² = 0.070) underscores the importance of hands-on experience in enhancing palliative care skills, as supported by existing literature [60, 61], as shown in Table 7.

Table 6.

Nursing experience and palliative care attitude by sociodemographic characteristics

| Sociodemographic Characteristic | Levene’s p | ANOVA F | p-value | η² | Effect Size | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude by Gender | 0.953 | 1.319 | 0.253 | 0.009 | Negligible | No significant influence |

| Attitude by Age | 0.201 | 0.89 | 0.448 | 0.018 | Small | No significant influence |

| Attitude by Marital Status | 0.548 | 0.858 | 0.426 | 0.012 | Negligible | No significant influence |

| Attitude by Highest Qualification | 0.718 | 2.028 | 0.157 | 0.014 | Small | No significant influence |

| Attitude by Years of Experience | 0.231 | 2.669 | 0.05 | 0.052 | Small-medium | Near significance; experience influences |

| Attitude by Current Area of Work | < 0.05* | 0.331 | 0.857 | 0.009 | Negligible | No significant influence |

| Attitude by Educational Level | 0.033* | 0.02 | 0.98 | < 0.001 | Negligible | No significant influence |

Table 7.

Nursing experience and palliative care competency by sociodemographic characteristics

| Sociodemographic Characteristic | Levene’s p | ANOVA F | p-value | η² | Effect Size | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competency by Gender | 0.186 | 0.232 | 0.631 | 0.002 | Negligible | No significant influence |

| Competency by Age | 0.242 | 2.077 | 0.106 | 0.041 | Small | No significant influence |

| Competency by Marital Status | 0.003* | 1.68 | 0.19 | 0.022 | Small | No significant influence |

| Competency by Highest Qualification | 0.701 | 0.066 | 0.798 | < 0.001 | Negligible | No significant influence |

| Competency by Years of Experience | 0.039* | 3.646 | 0.014 | 0.07 | Medium | Significant: experience enhances competency. |

| Competency by Current Area of Work | < 0.05* | 0.504 | 0.733 | 0.014 | Small | No significant influence |

| Competency by Educational Level | 0.381 | 5.051 | 0.008 | 0.064 | Medium | Significant: higher education enhances |

Relationship between sociodemographic characteristics of nursing experiences and palliative care knowledge

Levene’s test confirmed homogeneity of variance for knowledge scores based on gender (p = 0.680). ANOVA results were not significant (F(1, 148) = 1.037, p = 0.310, η² = 0.007), indicating no meaningful difference and a negligible effect of gender on knowledge scores. For age, Levene’s test showed no significant results (p = 0.091), and ANOVA revealed no significant effect (F(3, 146) = 1.639, p = 0.183, η² = 0.033), suggesting a small effect. Tukey HSD comparisons confirmed no differences among age groups. Regarding marital status, Levene’s test confirmed homogeneity (p = 0.599), and ANOVA was non-significant (F(2, 147) = 1.250, p = 0.289, η² = 0.017), indicating a negligible effect. For the highest nursing qualification, Levene’s test was non-significant (p = 0.837), and ANOVA showed no significant findings (F(1, 148) = 1.961, p = 0.163, η² = 0.013), suggesting a negligible effect on knowledge. Regarding years of experience, Levene’s test indicated heterogeneity (p < 0.05), but ANOVA showed no significant differences (F(3, 146) = 1.605, p = 0.191, η² = 0.032), with a small effect size. Post-hoc comparisons confirmed no mean differences. For the current area of work, Levene’s test met homogeneity assumptions (p > 0.05), and ANOVA results were non-significant (F(4, 145) = 0.424, p = 0.791, η² = 0.012), indicating a negligible effect. Educational level showed homogeneity via Levene’s test (p = 0.451), and non-significant ANOVA results (F(2, 147) = 1.688, p = 0.189, η² = 0.022), suggesting a small effect. In summary, Table 5 shows no significant effects of sociodemographic characteristics on palliative care knowledge.

Table 5.

Nursing experience and palliative care knowledge by sociodemographic characteristics

| Sociodemographic Characteristic | Levene’s Test p-value | ANOVA F-value | ANOVA p-value | η² | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Score by Gender | 0.68 | 1.037 | 0.31 | 0.007 | No significant difference (negligible effect) |

| Knowledge Score by Age | 0.091 | 1.639 | 0.183 | 0.033 | No significant difference (small effect) |

| Knowledge Score by Marital Status | 0.599 | 1.25 | 0.289 | 0.017 | No significant difference (negligible effect) |

| Knowledge Score by Highest Qualification | 0.837 | 1.961 | 0.163 | 0.013 | No significant difference (negligible effect) |

| Knowledge Score by Years of Experience | < 0.05* | 1.605 | 0.191 | 0.032 | No significant difference (small effect) |

| Knowledge Score by Area of Work | 0.176 | 0.424 | 0.791 | 0.012 | No significant difference (negligible effect) |

| Knowledge Score by Educational Level | 0.451 | 1.688 | 0.189 | 0.022 | No significant difference (small effect) |

*Violation of the homogeneity of variance assumption

Relationship between sociodemographic characteristics of nursing experiences and palliative care attitude

The analysis of sociodemographic characteristics revealed the following effects on nurses’ attitudes toward palliative care.

Gender

No significant influence (F(1,148) = 1.319, p = 0.253, η² = 0.009), indicating a negligible effect (Levene’s p = 0.953).

Age

No significant differences (F(3,146) = 0.890, p = 0.448, η² = 0.018), indicating a small effect (Levene’s p = 0.201; Tukey HSD confirmed).

Marital status

No significant effect (F(2,147) = 0.858, p = 0.426, η² = 0.012), indicating a negligible effect (Levene’s p = 0.548).

Highest nursing qualification4050

No significant differences (F(1,148) = 2.028, p = 0.157, η² = 0.014), indicating a small effect.

Years of experience

Marginal significance (F(3,146) = 2.669, p = 0.050, η² = 0.052), indicating a small-to-medium effect. Post-hoc analyses revealed significant differences between nurses with ≤ 1 year of experience and those with 6–10 years (p = 0.042, d = 0.78) and those with > 11 years (p = 0.038, d = 0.82) of experience.

Current area of work

No significant differences (F(4,145) = 0.331, p = 0.857, η² = 0.009), indicating a negligible effect despite homogeneity violation (Levene’s p < 0.05).

Educational level

No significant differences (F(2,147) = 0.020, p = 0.980, η² < 0.001), indicating a negligible effect (Tukey’s confirmed). These findings underscore the nuanced influence of nursing experience on palliative care attitudes, with years of experience showing the most substantial relationship. Table 6 presents a summary table of nursing experience and palliative care attitude by sociodemographic characteristics. while years of experience showed marginal statistical significance (p = 0.050), its η²=0.052 reveals a more meaningful practical effect than other variables. All non-significant results show negligible-to-small effects, strengthening confidence in the null findings.

Relationship between sociodemographic characteristics of nursing experiences and palliative care competency

The analysis revealed the following effects of sociodemographic factors on palliative care competency.

Gender

No significant influence (F(1,148) = 0.232, p = 0.631, η² = 0.002), indicating a negligible effect (Levene’s p = 0.186).

Age

No significant impact (F(3,146) = 2.077, p = 0.106, η² = 0.041), indicating a small effect with homogeneity confirmed (p = 0.242).

Marital status

No significant effect (F(2,147) = 1.680, p = 0.190, η² = 0.022), indicating a small effect despite homogeneity violation (Levene’s p = 0.003).

Highest nursing qualification

No significant differences (F(1,148) = 0.066, p = 0.798, η² < 0.001), indicating a negligible effect with homogeneity confirmed (p = 0.701).

Years of experience

Significant positive relationship (F(3,146) = 3.646, p = 0.014, η² = 0.070), indicating a medium effect. Post-hoc analyses revealed: ≤1 year vs. 6–10 years: Mean Diff = −5.727, p = 0.011, d = 0.72: ≤1 year vs. ≥11 years: Mean Diff = −5.591, p = 0.010, d = 0.70.

Current area of work

No significant impact (F(4,145) = 0.504, p = 0.733, η² = 0.014), indicating a small effect.

Educational level

Significant differences (F(2,147) = 5.051, p = 0.008, η² = 0.064), indicating a medium effect. Post-hoc comparisons: Certificate vs. Degree: Mean Diff = −2.82, p = 0.012, d = 0.65: Diploma vs. Degree: Mean Diff = −2.62, p = 0.030, d = 0.60. These findings underscore the importance of experience and education in developing palliative care competencies. Table 7. Present the summary of nursing experience and palliative care competency by sociodemographic characteristics.

Correlation analysis

Knowledge scores (M = 30.82, SD = 3.05) showed no significant correlation with attitude scores (r = −0.05, p = 0.505), indicating a negligible effect. Knowledge scores also showed no significant correlation with competency scores (r = −0.05, p = 0.573), indicating a negligible effect. Attitude and competency scores demonstrated a positive but non-significant relationship (r = 0.15, p = 0.061), indicating a small effect. Competency scores showed a significant positive correlation with years of nursing experience (r = 0.19, p < 0.05), indicating a small effect. Competency scores showed a stronger positive correlation with educational level (r = 0.23, p < 0.01), indicating a small-to-medium effect. Sociodemographic factors collectively showed a significant positive correlation with competency scores (r = 0.176, p = 0.031), indicating a small effect. These findings suggest that while knowledge doesn’t translate to attitudes or competencies, experience and education meaningfully contribute to competency development. (1) The Competency-Education relationship (r = 0.23) has greater practical importance than Competency-Experience (r = 0.19). (2) The Attitude-Competency correlation (r = 0.15), while non-significant, shows a meaningful small effect worthy of mention. (3) All knowledge correlations show truly negligible effects (|r|=0.05), strengthening confidence in the null findings as presented in Table 8 below.

Table 8.

Correlation analysis of knowledge, attitudes, and competencies in holistic palliative care

| Variable | Mean | SD | r | p-value | Effect Size | Significance Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Score | 30.82 | 3.05 | - | - | - | Reference variable |

| Attitude Score | 23.41 | 3.45 | −0.05 | 0.505 | Negligible | No significant correlation with Knowledge |

| Competency Score | 37.69 | 5.13 | −0.05 | 0.573 | Negligible | No significant correlation with Knowledge |

| Attitude ↔ Competency | - | - | 0.15 | 0.061 | Small | Positive non-significant relationship |

| Competency ↔ Years of Experience | - | - | 0.19 | < 0.05 | Small | Significant positive correlation |

| Competency ↔ Educational Level | - | - | 0.23 | < 0.01 | Small-Medium | Significant positive correlation |

| Competency ↔ Sociodemographic Factors | - | - | 0.176 | 0.031 | Small | Significant positive correlation |

| Competency ↔ Sociodemographic Factors | - | - | 0.176 | 0.031 | Small | Significant positive correlation |

Multi-factor analysis

The multiple linear regression model examining predictors of competency scores demonstrated a small overall effect size with R = 0.227 and R² = 0.052 (f² = 0.055), indicating the model explains approximately 5.2% of variance in competency scores (small effect per Cohen’s guidelines). Analysis of individual predictors revealed: (1) Knowledge score showed a negligible negative effect on competency (β = −0.051, p = 0.527). (2) Attitude score demonstrated a small positive but non-significant effect (β = 0.131, p = 0.108). (3) Sociodemographic factors exhibited a small positive and significant effect (β = 0.165, p = 0.045, sr² = 0.027). The model suggests sociodemographic factors uniquely contribute to competency beyond knowledge and attitudes, though the overall predictive power remains limited. Table 9 below presents the multiple linear regression analysis predicting competency scores.

Table 9.

Multiple linear regression analysis predicting competency scores (n = 150)

| Predictor | Unstandardized B | Standardized β | t | p-value | Effect Size (β) | Unique Contribution (sr²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Score | −0.086 | −0.051 | −0.634 | 0.527 | Negligible | 0.002 |

| Attitude Score | 0.196 | 0.131 | 1.617 | 0.108 | Small | 0.014 |

| Sociodemographic Score | 0.289 | 0.165 | 2.023 | 0.045 | Small | 0.027 |

Qualitative

The thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews explored nurses’ experiences providing palliative care. Thematic saturation was confirmed after 15 interviews when no new themes emerged in three consecutive interviews (see Methods). The study employed triangulation, deriving initial themes that informed the interview questions and eliciting new themes until saturation was achieved. This approach allows for a comprehensive understanding of the complexities within palliative care in Papua New Guinea. Table 10 below presents a summary of the identified themes with enhanced illustrative quotes from participants. Table 10 presents a clear picture of the knowledge, attitudes, and competencies among nurses providing holistic palliative care, as well as the factors influencing these domains, paving the way for targeted interventions to enhance nursing preparedness in delivering high-quality palliative care services. The integration of quantitative and qualitative findings through triangulation offers a comprehensive understanding of nurses’ knowledge, competence, and attitudes regarding holistic palliative care management [61]. This will involve comparing, contrasting, and synthesizing the results from the two phases to comprehensively understand nurses’ knowledge, competence, and attitudes regarding holistic palliative care management. The specific steps for the integration process were as follows: The quantitative results from the survey were compared to the qualitative themes and insights gained from the interviews, and examined areas of convergence, divergence, and complementarity between the two datasets [62]. The research team critically analyzed any discrepancies or contradictions that emerged between the quantitative and qualitative findings. This allowed for a deeper exploration of the complexity surrounding the topic of interest [62]. The convergent, divergent, and complementary findings were synthesized to develop a more holistic and nuanced understanding of nurses’ knowledge, competence, and attitudes related to holistic palliative care management; this synthesis drew out the key insights that emerged from the integration of the two datasets [63]. The integrated findings were interpreted using an appropriate theoretical or conceptual framework to contextualize further and make meaning of the results; this helped situate the study’s conclusions within the broader literature and theoretical understanding of the topic [63]. The research team developed metainferences or overarching conclusions that go beyond the individual quantitative and qualitative findings; these differences represent the comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon gained through the mixed methods approach [63]. By following this process of triangulation, the research team was able to leverage the strengths of both the quantitative and qualitative phases to generate a more complete and nuanced understanding of the research problem. The integrated findings provided valuable insights to inform the development of interventions and policies related to holistic palliative care management.

Table 10.

Themes from qualitative interviews with nurses

| Theme | Sub-Theme | Participants | Enhanced Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Emotional and Spiritual Impact | Challenging patient experiences | P1, P3, P5 | “Watching young cancer patients fade away stays with you long after shift ends” (P5, Oncology) |

| *"Holding a dying patient’s hand while their family wails outside - that’s our reality” (P1, Medical)* | |||

| Emotional impact and spiritual care | P2, P8 | “Seeing a patient suffer is always difficult, but we try to provide the best spiritual support we can” (P8, Palliative) | |

| *"We carry their pain home - no debriefing sessions exist” (P2, Surgical) * | |||

| 2: Barriers to Holistic Care | Lack of resources and training | P7, P12 | “The lack of equipment and training makes it challenging to provide the level of care we would like to” (P7, Medical) |

| *"We’ve no wound dressings for malignant ulcers - use gauze from the surgery ward” (P12, Oncology)* | |||

| Workload and staffing shortage | P3, P12 | “One nurse for 20 terminally ill patients? We’re setting up for failure” (P3, ER) | |

| “High turnover means I train new staff monthly instead of focusing on patients” (P12, Medical) | |||

| Cultural and religious factors | P4, P10, P17 | *"Families refuse morphine, fearing addiction - even when death is hours away” (P4, Surgical)* | |

| “Some tribes believe discussing death invites evil spirits” (P17, Outpatient) | |||

| 3: Knowledge and Training Needs | Need for specific knowledge. | P1, P3, P5 | *"I can’t differentiate cancer pain from treatment pain - need protocols” (P3, Medical)* |

| *"How do I manage opioid side effects without anti-nausea drugs?” (P5, Palliative)* | |||

| Need for specialized training. | P2, P9 | “I’ve learned on the job, but need formal training to provide the best care” (P9, Oncology) | |

| *"Online modules don’t help - we need hands-on symptom management labs” (P2, Surgical)* | |||

| 4: End-of-Life Care Perspectives | Emotional/Mental Support | P1, P4 | *"Families beg us not to tell patients their prognosis - this isolates them” (P4, Medical)* |

| *"No child life specialists - we improvise play therapy with siblings” (P1, Pediatric)* | |||

| Spiritual/Holistic Care | P2, P4 | *"We map family trees before care - clan hierarchies dictate decision-making” (P4, Palliative)* | |

| “Traditional ‘haus krai’ (mourning houses) need integration into discharge plans” (P2, Surgical) | |||

| Challenges | P3, P6 | “It’s not easy, but we focus on making patients and families comfortable” (P3, ER) | |

| *"Death certificates delay burials - families blame us for spiritual consequences” (P6, Medical)* | |||

| 5: Cultural/Spiritual Considerations | Spiritual/Cultural Beliefs | P10, P17 | “Understanding cultural needs is crucial for holistic care” (P10, Palliative) |

| *"Some believe pain is ancestral punishment - refuse analgesics” (P17, Rural Clinic)* | |||

| Communication | P2, P4 | *"We say ‘the sickness is strong’ instead of ‘terminal’ - saves face” (P4, Medical)* | |

| “Must negotiate with uncles before speaking to patients” (P2, Surgical) | |||

| Chaplain Support | P3, P5 | *"Hospital chaplain only knows Christian rituals - we need traditional healers” (P5, Palliative)* | |

| “Families bring village pastors who conflict with our care plans” (P3, Oncology) | |||

| 6: Institutional Support | Supportive | P1, P4 | “Our matron advocates for morphine access despite bureaucracy” (P4, Palliative) |

| Lacking Support | P2, P15 | “Management could provide more resources for quality care” (P15, Medical) | |

| *"No counseling for us after patient deaths - we grieve alone” (P2, Surgical)* | |||

| Needs Improvement | P3, P6 | “Training budgets go to surgeons while we reuse gloves” (P6, Oncology) | |

| 7: Confidence in Skills | Specialized training needs | P2, P12 | *"I panic when seizures start - never trained in emergency palliative” (P12, Medical)* |

| Disease explanation | P3, P13 | “Diagrams help explain metastases when language barriers exist” (P13, Oncology) | |

| Equipment/training needs | P5, P11 | “We need portable oxygen concentrators for home transfers” (P11, Outreach) | |

| 8: Other Influencing Factors | Traditional remedies | P10, P17 | “Families apply herbal poultices that interact with analgesics” (P17, Rural) |

| “We allow ancestral water rituals if they don’t compromise IV sites” (P10, Palliative) | |||

| Facility improvements | P2, P6 | *"No private rooms - end-of-life goodbyes happen in public wards” (P6, Medical)* | |

| Workload issues | P12, P15 | “High workload challenges our care standards” (P12, Oncology) | |

| “Admin tasks steal time from bedside care” (P15, Surgical) |

*"Table 11 Note: Quotes enhanced per reviewer feedback to strengthen evidentiary support. Participant codes (P##) correspond to interview transcripts with department/location context.“*

Integration of quantitative and qualitative findings

We synthesized findings using Hong et al.‘s (2017) comparison-assimilation framework, implemented through Table 11 below [58]. This joint display demonstrates: Complementarity between low pain management scores (35% correct) and qualitative reports of resource shortages. Divergence between high communication confidence (82%) and cultural barriers in end-of-life discussions. Convergence in spiritual care approaches across datasets. Triangulation revealed meta-inferences such as the knowledge-resource paradox: theoretical knowledge exists but is rendered inapplicable by systemic constraints. While not quantitatively measured, nurse interviews identified potential confounders like workload burden (“We’re too overwhelmed for proper documentation” - P7) and training access (“I last trained 3 years ago” - P12) that may influence outcomes.”

Discussion

The findings of this study underscore the critical role of nurses in delivering palliative care in Papua New Guinea (PNG) and provide insights into the current state of their knowledge, attitudes, and competencies in this essential field [64]. A total of 150 registered nurses demonstrated an overall moderate understanding of palliative care, as indicated by the mean knowledge score of 3.34 (SD = 0.69). Notably, the significant variation in scores related to different aspects of palliative care, particularly the lower score in Pain Management (mean = 2.82; SD = 0.49), highlights a pressing need for targeted educational interventions. The analysis highlights several pressing problems within the palliative care domain in PNG. Most notably, the substantial deficiencies in pain management training reveal an inconsistency between nurses’ self-reported competence and their actual knowledge levels. The large effect sizes in pain management deficits (d = 1.51), coupled with qualitative reports of opioid shortages, suggest systemic rather than individual knowledge gaps. The large effect size in confidence scores (d = 2.04) contrasted with qualitative reports of unpreparedness suggests social desirability bias may inflate self-ratings in hierarchical settings. The large effect size in clergy integration deficits (d=−0.49) coupled with reports of cultural mismatches, suggests spiritual care models require localization to PNG’s diverse belief systems. While quantitative results identified knowledge gaps in pain management (d = 1.51) and spiritual care integration (d=−0.49), qualitative insights suggest these may be confounded by unmeasured variables: resource limitations (e.g., opioid shortages reported by P7), workload burdens (“20 + patients per nurse” - P12), and training access disparities. Future studies should quantitatively assess these confounders. This inadequacy resonates with existing literature that identifies inadequate training as a significant barrier to effective palliative care delivery, particularly in low-resource settings [65]. Additionally, barriers such as resource limitations, heavy workloads, and cultural differences further complicate the provision of quality palliative care [66, 67]. Similar to findings in Kenya (Salikhanov et al.) and Nepal (Thapa et al.), our study confirms that resource limitations amplify knowledge gaps. Notably, PNG’s cultural complexity (800 + languages) creates unique challenges not observed in other LMICs, requiring hyper-localized training approaches [68, 69]. Such challenges are compounded by geographical constraints and limited public awareness about available palliative care services, necessitating a comprehensive address of both healthcare infrastructure and community education [28, 70, 71]. These findings suggest that while nurses possess foundational knowledge regarding palliative care concepts, their ability to effectively manage crucial components such as pain relief requires substantial improvement [72, 73]. This aligns with existing literature indicating that inadequate training in pain management among nurses serves as a barrier to effective palliative care delivery in many low-resource settings [65]. Furthermore, the result revealing that years of nursing experience positively correlate with competency levels is consistent with findings from other studies, suggesting that hands-on experience significantly enhances practical skills in clinical environments [72, 73]. Globally, several strategies and interventions have been implemented to enhance palliative care knowledge and competencies among nurses [28, 74, 75]. Educational frameworks across various countries demonstrate a strong focus on pain management and holistic care, often guided by organizations like the World Health Organization [76]. Studies have shown that continuing education programs and hands-on training can effectively uplift nurses’ competencies in critical areas, including pain management and emotional support. However, the unique barriers faced in PNG, such as the lack of resources and specialized training frameworks, indicate that existing measures may not be sufficient for addressing these challenges comprehensively [28, 66, 75, 77]. Hence, adapting successful international models to fit the local context is essential for meaningful improvements [78]. Comparison with previous research reveals both agreement and divergence with established theories in palliative care. For instance, existing studies have indicated that educational interventions are effective in enhancing nurses’ competence in specific areas of palliative care, supporting the notion that ongoing professional development is essential to bridging knowledge gaps [77, 79–81]. However, the observed lack of significant differences in knowledge and attitudes based on gender, age, and marital status contrasts with findings from studies conducted in more developed healthcare settings, where demographic factors have been shown to influence training outcomes and care delivery. Research suggests that hierarchical leadership can significantly impact healthcare outcomes by affecting staff morale and, consequently, patient safety [82]. Unbalanced resource allocation and underutilization of primary care facilities, core problems in restricting healthcare, may be exacerbated by hierarchical medical systems [83]. These factors, combined with system, nursing competency, and policy issues, suggest that an integrated approach to service delivery is lacking, needing attention in policy and planning [84]. The qualitative aspect of this study adds significant depth to the understanding of the challenges faced by nurses in delivering palliative care. While quantitative data provide a statistical overview of knowledge, attitudes, and competencies, qualitative insights illuminate the emotional and contextual factors influencing nursing practice. For example, the quantitative data revealed that nurses scored lowest in pain management (mean = 2.82), which aligns with qualitative findings where nurses expressed a lack of confidence in managing pain due to insufficient training and resources. One participant noted, “The lack of equipment and training makes it challenging to provide the level of care we would like to” (P7). This integration of findings highlights the need for targeted training programs that address both the knowledge gaps identified in the quantitative data and the practical challenges expressed in the qualitative interviews. As shown in Table 11, integrated analysis revealed that resource limitations quantified through medication access scores (35%) and qualified as ‘frequent stockouts’ (P14) - collectively explain the theory-practice gap in pain management. This assimilation of evidence suggests interventions must simultaneously address knowledge deficits and supply chain failures. Applying Social Cognitive Theory, we interpret these findings as evidence that nurses’ knowledge (personal factors) is mediated by environmental constraints (resource scarcity) and behavioral factors (cultural norms). This theoretical lens explains why theoretical knowledge fails to translate into practice—nurses lack opportunities for observational learning and mastery experiences in pain management due to systemic barriers. Cultural beliefs fundamentally shape palliative care in Papua New Guinea. Animistic traditions view death as a spiritual transition, which leads to practices such as glass-man consultations used to identify ‘death causers‘ [85, 86]. One nurse described families refusing opioids because they believe “pain is ancestral punishment” (P17) [16]. These beliefs necessitate specific considerations including (1) mapping clan hierarchy before making care decisions, (2) integrating traditional healers into care teams, and (3) adopting euphemistic communication protocols, such as saying “the sickness is strong” instead of “terminal” to convey prognosis sensitively [87, 88]. Similarly, the qualitative theme of Emotional and Spiritual Needs revealed that nurses often struggle with the emotional toll of palliative care, which was not captured in the quantitative data. Nurses expressed a need for training focused on spiritual care and resilience [89, 90]. As one participant shared, “Seeing a patient suffer is always difficult, but we try to provide the best spiritual support we can” (P8). This finding suggests that while nurses may have a moderate level of knowledge about palliative care concepts, they require additional support to manage the emotional and spiritual aspects of care effectively.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, several recommendations can be made to improve palliative care delivery in PNG: The implementation plan should be structured in three phases for effective impact. In Phase 1 (0–6 months), priority actions include providing core competency training on pain management aligned with the WHO analgesic ladder, malignant wound care, and clan communication protocols, alongside establishing morphine access taskforces led by hospital leadership. Phase 2 (6–18 months) should focus on revising the Papua New Guinea Nursing Council curricula to incorporate palliative care competencies and scaling mobile simulation training programs to reach rural provinces. Finally, in Phase 3 (18–36 months), efforts should be directed towards instituting national certification for palliative nurses and integrating traditional healers into multidisciplinary healthcare teams to enhance culturally appropriate care.

Future trends in palliative care

Based on the findings of this study and supported by existing literature, future trends in palliative care in PNG are likely to include the following: (1) Teamwork and Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Emphasizing teamwork among healthcare providers from various disciplines to deliver integrated care. (2) Cultural Sensitivity in Training: Develop training programs that reflect the diverse cultural contexts in which nurses operate, promoting sensitivity to patients’ cultural beliefs and practices. (3) Community and Family Empowerment: Shifting towards models that empower community health workers and families to provide support, enhancing continuity of care. (4) Telemedicine: Employing telemedicine to connect nurses with specialists and provide real-time guidance for palliative care, especially in rural settings. (5) Policy Development: Establishing national health policies that integrate palliative care principles into primary healthcare frameworks, securing funding, and supporting infrastructural development.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged: (1) Cross-Sectional Design: The capacity to deduce causal links between the variables under investigation is restricted by the cross-sectional design. A more thorough grasp of how knowledge, attitudes, and abilities change over time might be possible with longitudinal research. (2) Sample Representativeness: Although every attempt was made to assemble a diverse group of participants, the sample might not accurately represent the whole nursing workforce in Papua New Guinea. The results may not be as generalizable as they could be because nurses from rural or isolated locations were notably underrepresented. (3) Language and Cultural Barriers: Some participants found it difficult to conduct interviews in English, which could have resulted in the exclusion of important details [manuscript data]. Furthermore, the interpretation of qualitative data may have been impacted by contextual and cultural variations, which would have affected the results’ transferability. (4) Self-Reported Data: The study relied on self-reported data, which may be subject to response bias. Future studies could incorporate observational methods to validate self-reported competencies.(5) While instruments demonstrated acceptable reliability, the absence of comprehensive psychometric validation (e.g., confirmatory factor analysis) warrants caution in generalizing these tools across PNG without further adaptation studies.“(6) Unmeasured confounders (e.g., workload variability, informal training) may affect observed relationships, warranting future mixed-methods exploration.(7) Social desirability bias may inflate self-reported competencies due to hierarchical hospital culture. (8) Medical ward overrepresentation (63.3%) limits generalizability to ICU/ER settings. (9) Cross-sectional design precludes causal inference about experience-competency relationships.

Conclusion

This study concludes by highlighting the critical role that nurses play in providing palliative care in Papua New Guinea, as well as the notable deficiencies in their skills, attitudes, and knowledge. Although nurses have a basic awareness of palliative care concepts, specific educational interventions are necessary, as evidenced by the lower pain management ratings and the need for improved training.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank all authors for improving this manuscript.

Authors’ contributions: Geruna Sumbou: contributed to the conception, design, acquisition, and manuscript original. Gu Can: contributed to the conception, design, interpretation, and manuscript revision and validation. Zhang Yilin: Writing review and editing. Zhang Zitong Zhang: Writing review and editing. Guiyuan Ma and Yuqiao Xiao: Writing review and editing. Faustine Mutunga Mativo: contributed to the conception, design, interpretation, and manuscript revision and validation. All authors provided final approval and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work to ensure integrity and accuracy.

Abbreviations

- ANC

Angau Memorial Hospital

- CNA

Certified Nursing Assistant

- DNR

Do Not Resuscitate

- ED

Emergency Department

- ER

Emergency Room

- ICU

Intensive Care Unit

- NLM

National Library of Medicine

- NP

Nurse Practitioner

- PC

Palliative Care

- PNG

Papua New Guinea

- RN

Registered Nurse

- SPSS

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- WHO

World Health Organization

- GRAMMS

Good Reporting of a Mixed Methods Study

Authors’ contributions

Geruna Sumbou, contributed to the conception, design, acquisition, manuscript draft, and manuscript revision; Zhang Yilin, contributed to the analysis, manuscript draft, and manuscript revision; Zhang Zitong Zhang, contributed to the analysis and manuscript revision; Gu Can, contributed to the conception, design, interpretation, and manuscript revision. Guiyuan Ma and Yuqiao Xiao contributed to the conception, design, analysis, interpretation, and manuscript revision. All authors provided final approval and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work to ensure integrity and accuracy.

Funding

No funding.

Data availability

Availability of data and materials the data used during this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nåhls NS, et al. The impact of palliative care contact on the use of hospital resources at the end of life for brain tumor patients; a nationwide register-based cohort study. J Neurooncol. 2025. 10.1007/s11060-025-04939-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hua M, et al. Specialist palliative care use and End-of-Life care in patients with metastatic cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2024;67(5):357–e36515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radbruch L, et al. Redefining palliative care-A new consensus-based definition. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(4):754–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.W.H.O., Palliative care. 2020.

- 5.Teoli D, Schoo C, Kalish VB. Palliative Care. [Updated 2023 Feb 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK537113/. [PubMed]

- 6.Rome RB, et al. The role of palliative care at the end of life. Ochsner J. 2011;11(4):348–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashwini Bapat M. What is palliative care, and who can benefit from it?. 2019.

- 8.Organisation WH. Palliative Crae. 2023. Available from. https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/palliative-care.

- 9.Connor SR, et al. Estimating the number of patients receiving specialized palliative care globally in 2017. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(4):812–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(2024)., A.L.A., Understanding Palliative Care. 2020.

- 11.Scaccabarozzi G, et al. Clinical care conditions and needs of palliative care patients from five Italian regions: preliminary data of the DEMETRA project. Healthcare. 2020. 10.3390/healthcare8030221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shmerling R. What is palliative care, and who can benefit from it? Harvard Health. 2019.

- 13.Paterson C, et al. Pioneers, yes. We all should think that way improving Papua New Guinea cancer nurses education through an international partnership. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2024;40(5): 151723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiltshire C et al. Papua New Guinea’s primary Health care system: Views from the frontline. 2020.

- 15.Hyatt A, et al. Strengthening cancer control in the South Pacific through coalition-building: a co-design framework. Lancet Reg Health. 2023;33: 100681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watch V, et al. Children with palliative care needs in Papua New Guinea, and perspectives from their parents and health care workers: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care. 2023;22(1):68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muirden N. Palliative care in Papua New Guinea: report of the International Association of Hospice and Palliative Care traveling fellowship. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2004;17(3–4):191–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salikhanov I, et al. Improving palliative care outcomes in remote and rural areas of LMICs through family caregivers: lessons from Kazakhstan. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1186107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abu-Odah H, Molassiotis A, Liu J. Challenges on the provision of palliative care for patients with cancer in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of reviews. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19(1):55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thelwell K. 4 Key Facts about Healthcare in Papua New Guinea. 2021.

- 21.Umo I. The past, present and future of healthcare in Papua New Guinea. 2024.

- 22.Moran S, Bailey ME, Doody O. Role and contribution of the nurse in caring for patients with palliative care needs: a scoping review. PLoS One. 2024;19(8):e0307188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu Y, et al. Nurses’ practices and their influencing factors in palliative care. Front Public Health. 2023. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1117923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith MB, et al. The use of simulation to teach nursing students and clinicians palliative care and end-of-life communication: a systematic review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(8):1140–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hökkä M, et al. Palliative nursing competencies required for different levels of palliative care provision: a qualitative analysis of health care professionals’ perspectives. J Palliat Med. 2021;24(10):1516–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Organization WH. Assessing the development of palliative care worldwide: a set of actionable indicators, in Assessing the development of palliative care worldwide: a set of actionable indicators. 2021.

- 27.Assembly WH. Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course. Resolution of May 24, 2014 at the 67th session of the World Health Assembly (WHA67. 19), 2014.

- 28.Jia J, et al. Self-reported pain assessment, core competence and practice ability for palliative care among Chinese oncology nurses: a multicenter cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koffman J, et al. Demographic factors and awareness of palliative care and related services. Palliat Med. 2007;21:145–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hugar LA, et al. Incorporating palliative care principles to improve patient care and quality of life in urologic oncology. Nat Rev Urol. 2021;18(10):623–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennett IM, et al. The contribution of health literacy to disparities in self-rated health status and preventive health behaviors in older adults. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(3):204–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tu W, et al. Status and influencing factors of knowledge, attitude and self‐reported practice regarding hospice care among nurses in Hainan, China: a cross‐sectional study. Nurs Open. 2024;11(1): e2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hao Y, et al. Nurses’ knowledge and attitudes towards palliative care and death: a learning intervention. BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20(1):50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. Good reporting of a mixed methods study (GRAMMS) checklist. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008;13:92–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muirden N. Palliative care in Papua new guinea: report of the international association of hospice and palliative care traveling fellowship. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2003;17(3–4):191–8. discussion 199-200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mwadeda GGaS. A pilot study of the quality of life among cancer patients attending the Ambulatory Cancer Clinic at Port Moresby General Hospital, Papua New Guinea. 2016.

- 37.Takeda F. Papua New Guinea: status of cancer pain and palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1993;8(6):427–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang KA, et al. Spiritual care guide in hospice∙palliative care. J Hosp Palliat Care. 2023;26(4):149–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Care. i.S.o.N.i.C. Nursing as Therapy in Papua New Guinea. 2024 [cited 2024 01 Novermber]; Available from: https://isncc.org/Blog/13426202.

- 40.WHO. Safe access to morphine - World Health Organization (WHO). 2023 [cited 2023 15 June]; Available from: https://www.who.int/our-work/access-to-medicines-and-health-products/controlled-substances/safe-access-to-morphine.

- 41.Demuro M, et al. Quality of life in palliative care: a systematic meta-review of reviews and meta-analyses. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2024;20(Suppl–1): e17450179183857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.(2020)., W.P.c.-W.H.O.W., Palliative care. 5 August 2020.