ABSTRACT

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignant tumors, and its morbidity ranks third among all cancers, with a trend toward younger patients. Metabolic reprogramming, a unique metabolic mode in tumor cells, is closely related to the occurrence and development of CRC. Numerous studies have confirmed that many genetic and protein changes can regulate cellular metabolic reprogramming, of which changes in glucose metabolism have the greatest impact. These aberrant metabolic processes provide energy and essential nutrients to CRC cells, promoting their proliferation and metastasis and influencing tumor resistance. The purpose of this review is to outline the role of glucose metabolic reprogramming in the onset and development of CRC, discuss the research progress in the dual reprogramming of glucose metabolism and lipid metabolism or glucose metabolism and amino acid metabolism, and address the issues of targeted metabolism therapy and drug resistance.

Methods

We searched PubMed for review articles published in English between January 1, 2015, and April 26, 2024, which included “Colorectal Neoplasms” with “Metabolic Reprogramming” OR “Glucose Metabolism Disorders” OR “The Warburg Effect” OR “Targeted Therapy.” Subsequently, the literature was classified, organized, and summarized. Various types of studies were integrated and compiled into this review. Additionally, mechanism diagrams were drawn to facilitate the understanding of this study. The figures were created using BioRender.com and has obtained the official publication license.

Conclusions

Glucose metabolic reprogramming serves as a pivotal driver of CRC initiation, progression, and chemoresistance, while its crosstalk with lipid or amino acid metabolic reprogramming further amplifies the malignant phenotype of CRC. Targeted therapeutic strategies aiming at glucose metabolic reprogramming (such as metabolic inhibitors, combination with immunotherapy) and related clinical research have demonstrated potential for inhibiting CRC progression and improving treatment outcomes.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, glucose metabolism, metabolic reprogramming, targeted therapy

Abbreviations

- 2‐DG

2‐Deoxy‐D‐glucose

- 4‐OI

4‐Octyl itaconate

- ADMA

asymmetric dimethylarginine

- AF9

ALL1‐fused gene from chromosome 9

- AMPK

AMP‐activated protein kinase

- ARL15

ADP‐ribosylation factor‐like 15

- ART1

arginine ADP‐ribosyltransferase 1

- ATF4

transcription factor 4

- ChREBP

carbohydrate response element binding protein

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- CRMP2

collapsin response mediator protein 2

- DC

dendritic cells

- FABP4

fatty‐acid‐binding protein 4

- FBP

fructose‐1,6‐bisphosphate

- FOXM1

Forkhead box M1

- G6PD

glucose‐6‐phosphate dehydrogenase

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase

- GLUT

glucose transporter

- GPR37

G protein‐coupled receptor 37

- GSK‐3

glycogen synthase kinase‐3

- HIF1‐α

hypoxia‐inducible factor 1 alpha

- HK2

hexokinase 2

- HKDC1

hexokinase domain component 1

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- MnSOD

manganese superoxide dismutase

- OXPHOS

oxidative phosphorylation

- PBX3

Pre‐B‐cell leukemia transcription factor 3

- PCK

phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase

- PEPCK

phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase

- PFKFB3

fructose‐2,6‐biophosphatase 3

- PGC‐1α

peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma coactivator‐1α

- PGD

phosphogluconate dehydrogenase

- PHD2

prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2

- PLOD2

procollagen‐lysine, 2‐oxoglutarate 5‐dioxygenase 2

- PROX1

prospero‐related homeobox 1

- RARRES1

retinoic acid receptor responder 1

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RPIA

ribose‐5‐phosphate isomerase A

- SCD1

stearoyl‐CoA desaturase 1

- SELENBP1

selenium‐binding protein 1

- SIRT1

silent information regulator of transcription, sirtuin 1

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphisms

- SOX2

sex‐determining region Y‐box2

- TCA cycle

tricarboxylic acid cycle

- TME

tumor microenvironment

- Trx‐1

thioredoxin‐1

- XN

xanthohumol

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer‐related death globally [1]. CRC is a multifactorial disease influenced by both environmental and genetic factors. In addition to aging, adverse factors such as obesity, physical inactivity, and smoking further increase the risk of developing CRC [2]. Between 2012 and 2021, owing to health education and the reduction in smoking, the mortality rate of CRC patients has declined by 1.8% per year in both men and women [3]. Despite continuous advancements in screening methods, with significant improvements in detection rates, the mortality of advanced CRC patients remains unacceptably high even after undergoing comprehensive treatments such as surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy [4].

Metabolic reprogramming is a hallmark of cancer cells, representing a core characteristic of malignancy wherein alterations in the quantity and properties of metabolic enzymes, upstream regulatory molecules, and downstream metabolic products occur [5]. To meet the heightened demand for energy and nutrients, tumor cells have developed novel metabolic pathways involving modifications in the glycolytic pathway, induction of the Warburg effect, lipid metabolism remodeling, regulation of amino acid metabolism, alterations in one‐carbon unit metabolism, and nucleotide metabolism [6]. Among these, glucose metabolic reprogramming has been proven to occur in various tumors, playing crucial roles in gene transcription, DNA damage repair, and the regulation of epigenetic modifications [7, 8, 9].

The primary goal of glucose metabolic reprogramming in CRC cells is to maximize anabolic metabolism and obtain the energy required for rapid growth. Other functions include providing anti‐apoptotic signals and substances that allow cancer cells to evade programmed cell death, thereby increasing their survival and proliferation. Additionally, considering that cancer cells often experience hypoxic conditions, glucose metabolic reprogramming assists in their adaptation and survival in low‐oxygen environments [10]. These aberrant metabolic processes provide energy and essential nutrients for CRC cells, thereby promoting their proliferation and metastasis [11]. Moreover, aberrant metabolism often leads to reduced chemotherapy efficacy, thus increasing the complexity of treatment [12, 13].

In recent years, with the development of experimental techniques, the targeting of genes and proteins related to metabolic reprogramming has provided a new direction for the prevention and treatment of CRC [14, 15]. Its core principle is to selectively inhibit or modulate key metabolic enzymes or pathways on the basis of the characteristics of tumor cell metabolic reprogramming, thereby suppressing the proliferation of tumor cells. Detection technologies based on tumor metabolism (such as fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)‐PET) have been widely applied in clinical trials of cancer [16]. These technologies can not only help identify the metabolic characteristics of tumor cells but also be used to evaluate the effects of targeted metabolism therapies.

Cellular metabolism is an integrated and dynamic process. The metabolism of the three major nutrients—glucose, lipids, and amino acids—is closely interconnected. This interconnection is further accentuated in the metabolic reprogramming of tumor cells [17]. Many factors that modulate the reprogramming of glucose metabolism in CRC also concurrently influence lipid or amino acid metabolism, thereby collectively impacting the biological characteristics of CRC. In this review, we analyze how glucose metabolic reprogramming in CRC interacts with other metabolic pathways, such as amino acid and lipid metabolism, to collectively impact tumor progression. Our review highlights the compilation and analysis of studies involving dual metabolic reprogramming related to glucose metabolism and lipid metabolism or glucose metabolism and amino acid metabolism. Additionally, we reviewed and integrated research on cuproptosis, a form of programmed cell death that has been widely studied in recent years, elucidating its underlying mechanisms and its relationship with glucose metabolic reprogramming. These two novel perspectives provide new insights into the future research directions for CRC.

This article systematically elaborates on glucose metabolic reprogramming in CRC, introducing potential mechanisms that affect tumor growth, proliferation, and metastasis. The impact of concurrent dual metabolic reprogramming in CRC was systematically analyzed. Targeted therapies, new drug developments, and clinical trials related to glucose metabolic reprogramming are also discussed. In summary, we described how glucose metabolism‐related molecules interact with carcinogenic factors and lead to the occurrence and development of CRC, which may help better understand their potential roles in intestinal diseases.

2. Mechanism of Glucose Metabolism Reprogramming in CRC

Glucose plays a pivotal role in cell metabolism as a primary energy source. It is involved in various metabolic processes, including glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, the pentose phosphate pathway, gluconeogenesis, and glycogen metabolism. In addition to producing ATP, the energy currency of the cell, glucose can also be utilized in the synthesis of macromolecules such as nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids. Its metabolism also influences crucial cellular processes, including the regulation of gene expression and signaling pathways [18].

2.1. The Warburg Effect

The Warburg effect was the first formally proposed metabolic reprogramming pathway. In the 1920s, Otto Warburg discovered that cancer tissue slices consumed a substantial amount of glucose in vitro to produce lactate, even under aerobic conditions [19]. This process provides additional energy and nutrients to tumor cells. In 1929, the British biochemist Herbert Crabtree subsequently expanded upon Warburg's work and studied the heterogeneity of glycolysis in different tumor types. They confirmed the Warburg effect and further discovered that there are differences in the levels of respiration among different types of tumor cells, with many tumors exhibiting extensive respiration. To some extent, the carbohydrate metabolism of tumors is influenced by the environment in which they grow [20].

Owing to the limitations of the experimental conditions at the time, Warburg and colleagues were unable to investigate the mechanism behind the phenomenon, nor did they know what specifically caused it, whether it was driven by intrinsic factors or propelled by external factors. Warburg hypothesized that cancer is ultimately triggered by chemicals that destroy cellular respiratory organs, which are now known as mitochondria, damaging the ability of cells to perform oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Normal somatic cells meet their energy requirements by breathing oxygen, whereas cancer cells generate energy primarily through fermentation. Therefore, if the respiratory function of body cells remains intact, cancer can be prevented [21]. Racker further investigated and developed this theory by analyzing the differences in the respiratory capacity of tumor cells from the perspective of imbalanced intracellular pH and active‐defective ATP enzymes [22, 23]. Subsequent observations revealed that aerobic glycolysis is a controllable process that can be directly influenced by modulating growth factor signals, providing new insights into the development of the Warburg effect [24, 25].

However, the causative theory proposed by Warburg was later proven incorrect. In 2006, Leder et al. demonstrated that knocking out lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) to inhibit aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells led to an oxygen‐dependent compensatory increase in oxygen consumption and OXPHOS. Knockout of LDH inhibits the proliferative capacity of cancer cells. Therefore, tumor cells retain the ability for normal respiration but preferentially utilize aerobic glycolysis to rapidly produce less ATP, enabling them to grow and divide more quickly [26]. With the development of genetics and metabolomics, oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes were subsequently discovered, demonstrating a causal relationship between their mutations and malignant transformation. The linkage between genes and metabolism offers new insights into the Warburg effect, thus ushering research on the Warburg effect into a new phase (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Illustration of the genes associated with metabolic reprogramming in the Warburg effect and the TCA cycle in CRC cells, along with their interconnections.

Over time, scientists discovered that the Warburg effect is evident in nearly all solid tumor cells, including CRC cells, and serves as an “energy supply station” for tumor growth and proliferation [27]. It also promotes the invasion and metastasis of CRC by reshaping the tumor microenvironment (TME). The Warburg effect enhances the ability of cancer cells to produce lactate, leading to acidification of the TME, and an acidic pH can accelerate the migration rate of tumor cells [28].

In recent years, on the basis of the metabolic characteristics of tumor cells and the expression levels of the Warburg effect, some scholars have classified tumors into different Warburg subtypes for research purposes [29, 30, 31]. A Dutch study used immunohistochemistry to quantify and analyze the expression levels of six proteins related to the Warburg effect (LDHA, GLUT1, MCT4, PKM2, p53, and PTEN) and classified CRC patients into three Warburg subtypes (low/medium/high) on the basis of these levels. The results revealed that patients with the high‐Warburg phenotype had the worst disease‐specific and overall survival rates. Nevertheless, there are many challenges in investigating the value of the Warburg subtype in the diagnosis and treatment of CRC patients [32]. A comprehensive multicenter study investigating the association between the Warburg effect and the TME revealed no significant correlation between the Warburg phenotype and the tumor‐infiltrating lymphocyte score or stromal score. The Warburg subtype cannot be directly linked to the quantity of lymphocytes infiltrating CRC or to the relative amount of tumor stroma content [33]. Furthermore, the Warburg subtype may also be correlated with tumor immune cells and cancer‐associated fibroblasts. This classification has promising implications for the metabolic treatment of patients with CRC. Personalized metabolic treatments can be implemented by discerning the metabolic characteristics of tumors in different patients. In summary, the influence of the Warburg effect on the treatment strategies and prognosis of CRC patients warrants further investigation [34].

The development of genomics and proteomics has also aided the study of the Warburg effect. On the basis of epigenetic studies of non‐coding RNAs, researchers have identified key factors in CRC cells associated with the Warburg effect, including transcription‐related factors (KRAS, APC, c‐Myc, and HIF1‐α), metabolic product transport proteins (GLUTs), and glycolytic enzymes (HK2, PDK1, and LDH) [35]. The glucose transporter (GLUT) is responsible for the specialized uptake and transport of glucose [36]. In CRC, GLUT3 is highly expressed. Under conditions of limited glucose availability, GLUT3 accelerates glucose uptake and promotes nucleotide synthesis, thereby facilitating the growth of CRC cells through the AMPK/CREB1/GLUT3 axis. This effect is even more pronounced than the impact of GLUT1 on cellular growth [37, 38, 39]. In a low‐oxygen environment, hypoxia‐inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF1‐α) is activated, facilitating cellular metabolic adaptation. This adaptation includes an increase in glucose uptake and the acceleration of its conversion to lactate. Hexokinase 2 (HK2) plays a crucial role in glucose metabolism by catalyzing the conversion of glucose to glucose‐6‐phosphate. As a downstream target gene of HIF1‐α, HK2 is directly regulated. Elevated HK2 activity amplifies glucose absorption and metabolism within cells, thus providing the necessary energy and biosynthetic building blocks crucial for the growth and survival of tumor cells [40, 41]. Measures to counteract the overexpression or mutation of these factors, such as personalized epigenetic modulators, can potentially improve the unfavorable prognosis of patients with CRC.

The increased glycolysis rate caused by the Warburg effect promotes the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). During glycolysis, some intermediate products may enter the mitochondria and participate in the electron transport chain, thereby increasing ROS production. ROS promote the tendency of cancer cells to utilize glycolysis for metabolism, thereby promoting the Warburg effect [42]. ROS can affect multiple signaling pathways, such as the PI3K/Akt and HIF‐1α pathways, which play important roles in regulating cellular metabolism. While modest levels of ROS disrupt signaling pathways that are advantageous for cell proliferation, an overabundance of ROS can inflict harm on nucleic acids and cell membranes, culminating in cell death. Cancer cells maintain appropriate levels of ROS through alterations in the mitochondrial redox potential, which is influenced by the Warburg effect. Furthermore, they enhance their antioxidant defense systems to offset excess ROS, thus promoting their proliferation and survival [43, 44]. Manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD/SOD2), a key mitochondrial enzyme, regulates the spectrum of ROS produced by organelles, significantly influencing cellular signaling dynamics. Studies have revealed that MnSOD upregulation perpetuates the Warburg effect by modulating mitochondrial ROS and AMPK‐mediated cancer signaling pathways. Curtailing MnSOD expression or inhibiting AMPK activity curbs cancer cell metabolism, underscoring the pivotal role of the MnSOD/AMPK axis in sustaining cancer cell bioenergetics. MnSOD has emerged as a potential biomarker for gauging cancer progression and is a central regulatory element in tumor cell metabolism [45, 46].

Compared with the complete oxidation of glucose, the glycolytic pathway generates fewer NADH molecules per unit of glucose consumed. This is because glycolysis produces only two NADH molecules per molecule of glucose, whereas the complete oxidation of a single glucose molecule can generate a greater number of NADH molecules. As a result, the overall production of NADH in tumor cells is reduced [47]. Additionally, under normal circumstances, NADH is reoxidized in the mitochondrial electron transport chain to NAD+, generating a large amount of ATP [48]. Therefore, compared with that in normal cells, the proportion of NADH that is reoxidized through the electron transport chain to produce ATP in tumor cells is decreased, and more NAD+ is regenerated through lactate fermentation [49]. In summary, the Warburg effect, by reducing the production of NADH and altering its utilization, significantly changes the internal energy metabolism of tumor cells, which is crucial for their growth and survival. Some researchers believe that in cancer cells, the Warburg effect occurs after the cycle and closure circuit between Glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and LDH, leading to an increase in endogenous oxidative stress and carcinogenesis. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cancer cells results in high levels of glycolysis, which leads to the accumulation of NADH. H, thereby promoting the Warburg effect. Similarly, the oxidation of NADH. H produced excess NAD+ by LDH, which secondarily drives the GAPDH reaction to irreversibly produce NADH. Pyruvate acts as an antioxidant, whereas lactate acts as a pro‐oxidant, leading to an increase in endogenous oxidative stress and tumor hypoxia and high levels of glycolysis with NADH in cancer cells. On the basis of these findings, they proposed methods that might help prevent and combat the Warburg effect: the use of siRNAs to target GAPDH and LDH and the use of strong antioxidants to induce antioxidant–oxidant antagonism or antioxidant–salicylate antagonism to inhibit the Warburg effect, thus breaking the closed cycle [50].

Key enzymes involved in metabolic processes are our focal point in the study of metabolic reprogramming. Pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) is an isozyme of pyruvate kinase that activates the glycolytic pathway, enabling CRC cells to utilize glucose more efficiently for energy generation [51]. Studies have reported significantly elevated levels of PKM2 expression in CRC tissues compared with normal tissues. Furthermore, PKM2 contributes to the early diagnosis and prognosis assessment of CRC, with high expression associated with clinical features such as lymph node metastasis, tumor staging, and poor prognosis [52, 53, 54, 55]. PKM2 directly interacts with OTUB2, an OTU deubiquitinase overexpressed in CRC, inhibiting its ubiquitination by blocking the interaction between PKM2 and the ubiquitin E3 ligase Parkin. This process enhances PKM2 activity, consequently promoting glycolysis [56]. In the presence of fructose‐1,6‐bisphosphate (FBP), FOXM1D, an isoform of Forkhead box M1, binds to tetrameric PKM2, forming a hetero‐octameric structure. This interaction significantly limits the metabolic activity of PKM2, thereby promoting aerobic glycolysis [57]. These studies indicate that PKM2 has the potential to serve as a tumor marker for CRC, assisting in diagnosis, prognosis assessment, and monitoring treatment effectiveness. Figure 1 displays a portion of genes related to the Warburg effect and their interconnections in CRC.

As the fundamental metabolic process underlying the Warburg effect, subtle alterations in glycolysis have garnered significant attention in recent CRC research [58]. These studies often identify upstream factors associated with glycolytic enzymes and utilize cell line experiments or animal studies to elucidate their direct or indirect impacts on glycolysis in CRC cells. Table 1 summarizes the core molecules, research methods, and key conclusions of relevant studies.

TABLE 1.

A compilation of reports on glycolysis abnormalities in CRC from the latest research.

| Core molecule | Key downstream molecules | Impacts on glycolysis | Research method | Impacts on CRC | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSUN2 | YBX1/m5C‐ENO1 | ↑ | In vivo and vitro |

Promote tumorigenesis and metastasis. Inhibit tumor immunity. |

[59] |

| Plectalibertellenone A |

TGF‐β/Smad pathway Wnt pathway |

↓ | In vitro | Inhibit proliferation, migration and invasion. | [60] |

| CMTM6 | GLUT1 | ↑ | In vivo and vitro | Promote proliferation and metastasis. | [61] |

| SHP2 | PKM2 | ↑ | In vivo and vitro |

Promote proliferation, migration and invasion. Inhibit apoptosis and increase cisplatin resistance. |

[62] |

| PTBP1 | PKM2 | ↑ | In vivo and vitro | Promote proliferation, invasion, migration. | [63] |

| TMPO‐AS1 | PKM2 | ↑ | In vitro | Promote proliferation and migration. | [64] |

| SPAG4 | PI3K/Akt pathway | ↑ | In vitro | Promote growth and metastasis. | [65] |

| miR‐486‐5p | NEK2 | ↓ | In vitro | Inhibit proliferation, migration, and cell stemness. | [66] |

| UBTD1 | c‐Myc/HK2 | ↑ | In vivo and vitro | Promote proliferation and migration. | [67] |

| BRIX1 | GLUT1 | ↑ | In vivo and vitro | Promote proliferation. | [68] |

| Tectorgenin |

LncRNA CCAT2 miR‐145 |

↓ | In vivo and vitro | Promote proliferation. | [69] |

| PHD2 | NF‐κB pathway | ↓ | In vivo and vitro | Inhibit proliferation. | [70] |

| SELEENBP1 | HIF1α | ↓ | In vivo and vitro | Inhibit proliferation and promote cell apoptosis. | [71] |

| GPR37 | Hippo pathway | ↑ | In vivo and vitro | Promote metastasis. | [72] |

| AF9 | PCK2 | ↓ | In vivo and vitro | Inhibit proliferation and migration. | [73] |

| STING | HK2 | ↑ | In vivo and vitro | Promote tumor immunity. | [74] |

| FABP4 | ROS/ERK/mTOR pathway | ↑ | In vivo and vitro |

Promote proliferation and stemness. Inhibit apoptosis. |

[75] |

| CircVMP1 | HKDC1 | ↑ | In vivo and vitro | Promote proliferation and metastasis. | [76] |

| SETD8 | HIF1α /HK2 pathway | ↑ | In vivo and vitro | Promote proliferation and inhibit cell apoptosis. | [40] |

| SOX2 | GLUT1 | ↑ | In vivo and vitro |

Promote proliferation and migration. Promote vasculogenic mimicry. |

[77] |

| PROX1 | SIRT3 | ↑ | In vivo and vitro | Promote proliferation. | [78] |

2.2. Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle

The tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle is significantly affected during tumor development. In normal cells, the TCA cycle is one of the key metabolic pathways essential for cell survival, as it oxidizes organic substances into carbon dioxide and water, generating ATP for energy (Figure 1). However, in tumor cells, owing to factors such as hypoxia, nutrient deficiency, and increased metabolic demands, there is a preference toward anaerobic glycolysis, possibly inhibiting or altering the TCA cycle to some extent [79]. With the development of metabolomics, differences in the metabolic profiles between normal cells and tumor cells have increasingly been discovered. Some intermediate products of the TCA cycle, such as isocitrate and malate, are considered biomarkers for distinguishing the malignancy of tumors [80].

Genetic variations in the enzymes of the TCA cycle are significantly associated with CRC susceptibility. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the TCA cycle are diagnostic biomarkers for CRC, and researchers have proposed identifying high‐risk CRC populations by detecting these SNPs [81]. OGT is the sole enzyme responsible for O‐GlcNAc glycosylation, and depleting OGT can significantly enhance TCA cycle metabolism in CRC cells. The OGT‐c‐Myc‐PDK2 axis is a key mechanism linking oncogene activation to the dysregulation of TCA cycle metabolism [82]. The TCA cycle is also associated with ferroptosis in tumor cells. Research has demonstrated that inhibiting activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) and cystathionine β‐synthase (CBS) can target the mitochondrial cycle, increasing the susceptibility of CRC cells to ferroptosis. Therefore, blocking the ATF3‐CBS signaling axis may represent a potential therapeutic strategy for CRC [83].

In addition to ferroptosis, cuproptosis is a newly discovered type of programmed cell death related to cellular metabolism [84]. Cuproptosis participates in and accelerates the Fenton reaction in the body, generating highly reactive hydroxyl free radicals and ROS. Excessive ROS can damage cellular lipids, proteins, and DNA, ultimately leading to cell death. Additionally, the accumulation of ROS damages mitochondria by affecting their membrane potential, causing mitochondrial dysfunction. This process is a primary factor in how cuproptosis leads to the reprogramming of the TCA cycle [85] On the basis of the metabolic activity of the tumor, the degree of immune infiltration, and fibrosis, CRC can be divided into three distinct cuproptosis–hypoxia (CHS) subtypes. Studies indicate that in different CHS groups, patients exhibit significant differences in prognosis and sensitivity to conventional drugs [86]. In a study of CRC immunotherapy, researchers selected 10 genes associated with cuproptosis to determine the patterns of cuproptosis and related TME characteristics. They established the COPsig score to quantify the cuproptosis patterns in individual patients. Patients with higher COPsig scores were characterized by longer overall survival times, lower infiltration of immune and stromal cells, and a higher tumor mutation burden. Additionally, single‐cell transcriptomics analysis suggested that cuproptosis marker genes, such as ASPRV1 and TNKS, recruit tumor‐associated macrophages to the TME by regulating the TCA cycle and glutamine and fatty acid metabolism, thereby affecting the prognosis of CRC patients [87]. Cuproptosis‐related long non‐coding RNAs have also been demonstrated to be applicable in the chemotherapy and immunotherapy of CRC [88]. Moreover, there is a relationship between glycolysis levels and cuproptosis. 2‐DG, an inhibitor of glycolysis, can sensitize cells to cuproptosis. Additionally, galactose further promotes cuproptosis. The study also revealed that 4‐Octyl itaconate (4‐OI) significantly enhanced cuproptosis. Mechanistically, 4‐OI inhibits aerobic glycolysis by targeting GAPDH, a key enzyme in glycolysis, thereby sensitizing cells to cuproptosis [89]. This mechanism of promoting cuproptosis by inhibiting aerobic glycolysis is also a potential target for further research on targeted therapies.

2.3. OXPHOS

OXPHOS is closely linked to the TCA cycle. The TCA cycle generates NADH and FADH2 by oxidizing acetyl‐CoA, which is then used in OXPHOS to create a proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane. This gradient drives ATP synthase to produce ATP, linking the TCA cycle's metabolites directly to OXPHOS's energy production. Owing to the occurrence of the Warburg effect and the suppression of the TCA cycle, the level of OXPHOS in tumor cells is reduced. Changes in the efficiency of OXPHOS can impact the energy balance and survival of cancer cells and may also encourage cancer cells to develop strategies to evade detection by the immune system, such as by altering the extracellular pH or affecting antigen expression [90]. Moreover, the reprogramming of OXPHOS can lead to stress in the intracellular environment, affecting cell signaling pathways, thus potentially affecting the proliferation and survival of cancer cells. However, OXPHOS has recently been identified as an emerging contributor to tumorigenesis and tumor progression. OXPHOS is important not only because of its ability to generate sufficient energy to support tumor cells but also because of its key role in regulating cell death and its ability to produce ROS, which can promote the malignant transformation of normal cells. Therefore, OXPHOS is involved in several aspects of cancer progression.

PPARγ coactivator 1α (PGC‐1α) profoundly influences OXPHOS by stimulating mitochondrial biogenesis, thereby causing cells to exhibit more oxidation and less glycolysis [91, 92]. Studies have shown that the expression of PGC‐1α is associated with tumor growth and metastasis. Moreover, the increase in OXPHOS mediated by PGC‐1α is a key factor leading to cancer resistance to first‐line chemotherapy drugs (oxaliplatin and 5‐FU) [93, 94, 95]. One study in which exosomes circ_0001610 from oxaliplatin‐resistant cell models were collected revealed that circ_0001610 upregulated the activity of PGC‐1α‐dependent OXPHOS, leading to reduced drug sensitivity in recipient cells [96]. Investigating the mechanisms of the exosome‐mediated increase in OXPHOS and exploring its link to chemotherapy resistance may provide a new target for CRC treatment.

OMA1 is a mitochondrial protease that is activated under stress conditions and promotes the development of CRC by driving metabolic reprogramming. The OMA1‐OPA1 axis is activated by hypoxia, increasing mitochondrial ROS to stabilize HIF‐1α, thereby promoting glycolysis in CRC cells. In contrast, under hypoxic conditions, depletion of OMA1 promotes the accumulation of components of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, such as NDUFB5 and COX4L1, supporting the suppression of OXPHOS in tumor cells. The results show that the coordinated action of OMA1 in glycolysis and OXPHOS promotes the development of CRC and highlight OMA1 as a potential target for the treatment of CRC [97]. In fact, many other factors affect OXPHOS in CRC. For example, leptin is a hormone secreted by adipose tissue. It can regulate fatty acid β‐oxidation and the TCA cycle in tumor cells through the c‐Myc/PGC‐1 pathway and greatly increase OXPHOS activity [98]. OXPHOS is weakened in CRC; however, even under these conditions, the OXPHOS process still promotes the growth and metastasis of CRC. Therefore, for tumor types such as CRC, which tend to rely on glycolysis, reducing OXPHOS might be more effective in limiting tumor development. However, many factors need to be considered in the treatment of tumors, and treatments that target metabolism should consider drug side effects and be personalized.

2.4. Other Glucose Metabolism Pathways

The metabolic reprogramming of glucose metabolism in cells also involves several other aspects (Figure 2). The pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) is an important pathway in glucose metabolism that functions primarily to decompose glucose into pentoses while generating ATP and NADPH to provide the energy and materials required for cell growth and metabolism [99]. Owing to the need for metabolic activity that is greater than normal, the PPP often tends to increase in tumor cells [100]. Pre‐B‐cell leukemia transcription factor 3 (PBX3) belongs to the PBX family and is known for its elevated expression in various tumors, which is correlated with metabolic reprogramming. Glucose‐6‐phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) is a pivotal rate‐limiting enzyme in the PPP, and research has revealed that PBX3 functions as a positive regulator of G6PD. In CRC cells, PBX3 enhances the transcriptional activity of G6PD by directly binding to its promoter, thereby augmenting PPP activity. The PBX3/G6PD axis also has tumorigenic potential both in vitro and in vivo [101]. In addition, NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4) enhances PPP activity through its interaction with G6PD, promoting the clearance of ROS and thereby protecting CRC cells from ferroptosis [102]. ATP13A2, a lysosome‐related transmembrane P5‐type ATP transportase, has been identified as a novel gene associated with the PPP. ATP13A2 primarily regulates the PPP by influencing the mRNA expression of phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (PGD). The overexpression of ATP13A2 promotes its nuclear localization by inhibiting the phosphorylation of TFEB, thereby increasing the transcription of PGD and ultimately affecting PPP activity. Conversely, a deficiency in ATP13A2 leads to reduced levels of PPP products and an increase in ROS, thereby inhibiting the growth and invasion of CRC [103].

FIGURE 2.

Illustration of the pentose phosphate pathway, gluconeogenesis, glycogenesis, and glycogenolysis in CRC, along with the genes and mechanisms associated with metabolic reprogramming displayed above.

Gluconeogenesis is a process opposite to glycolysis and involves the generation of glucose from noncarbohydrate precursors such as pyruvate, lactate, amino acids, and glycerol, which primarily occurs in the liver and, to a lesser extent, in the kidneys. This pathway plays a crucial role in maintaining normal blood glucose levels, particularly during extended periods of fasting or intense physical activity. Tumor growth requires the substantial synthesis of biomacromolecules, whereas gluconeogenesis consumes the potential carbon sources required for proliferation. Gluconeogenesis is an energy‐consuming process. Therefore, enhancing glycolysis and reducing gluconeogenesis are beneficial for tumor cells. Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PCK) is a rate‐limiting enzyme in gluconeogenesis that catalyzes the conversion of oxaloacetate (OAA) to phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) [104, 105]. PCK1 is the cytosolic isoform of the enzyme, and PCK1 deficiency can regulate gluconeogenesis and lead to inherited metabolic disorders [106]. Research has shown that the cytosolic level of PCK1 is significantly reduced in CRC, and high PCK1 deficiency can regulate gluconeogenesis and lead to inherited metabolic disorders. PCK1 counteracts CRC growth by inactivating the phosphorylation of UBAP2L at serine 454 and enhancing autophagy. On the other hand, from a metabolic standpoint, low PCK1 expression weakens gluconeogenesis, which to some extent benefits tumor growth [107].

Owing to their high energy demands, tumor cells break down glycogen more than they synthesize and store it. Glycogen synthase kinase‐3 (GSK‐3) is a serine/threonine kinase that does not directly catalyze glycogen synthesis. GSK‐3 indirectly regulates glycogen synthesis by inhibiting glycogen synthase (GS) activity. GSK‐3 phosphorylates GS, which reduces the activity of glycogen synthase, thereby inhibiting glycogen synthesis. GSK‐3 has been shown to be significantly correlated with tumor budding grade and PD‐L1 levels in CRC, providing new insights into immunotherapeutic approaches for patients with CRC who have a poor prognosis [108]. Dynamin‐related protein 1 (Drp1), a member of the dynamin family of GTPases, triggers the activation of a compensatory metabolic pathway through the activation of AMPK due to the silencing of Drp1 expression. In this pathway, increased glucose uptake funnels into the glycogen biosynthesis pathway, resulting in glycogen buildup in CRC cells. Research shows that targeting Drp1 for treatment is unlikely to be sufficient to eliminate cancer cells, but inhibiting the breakdown of glycogen could increase the chemosensitivity of cancer [109].

3. Dual Metabolic Reprogramming of Glucose and Lipid/Amino Acid in CRC

The metabolism of nutrients within the cell is a complex, dynamic, and interrelated process. In normal cells, the metabolism of the three major nutrients is closely interconnected and can be interconverted. In CRC cells, metabolic reprogramming is not limited to glucose metabolism; lipid metabolism and amino acid metabolism also undergo significant reprogramming [110]. The coordinated regulation of these metabolic pathways plays a crucial role in the progression and chemoresistance of CRC.

Short‐chain fatty acids (such as butyrate) can trigger a series of events in cells, inhibiting glycolysis in cancer cells and affecting fatty acid oxidation at the same time, thus exerting a dual influence on CRC metabolism through this metabolic chain reaction [111, 112, 113]. Recent reports have indicated that the combination of butyrate and selenite can inhibit colon cancer by influencing amino acid metabolism, which may serve as an effective strategy to increase the efficacy of chemotherapy in the future [114]. Silent information regulator of transcription, sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) is a NAD+‐dependent deacetylase that is well known for its impact on both glycolysis and lipid metabolism in tumors. SIRT1 exerts its effects by modulating the Wnt/β‐catenin pathway, thereby inhibiting glycolysis and promoting fatty acid oxidation, which in turn facilitates tumor cell proliferation. Additionally, the mutual negative feedback loop between Wnt and SIRT1 has recently emerged as a focal point of research [115, 116]. O‐GlcNAcylation is a type of post‐translational modification of proteins that involves the addition of N‐acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) to serine or threonine residues of cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins [117]. Recent studies have shown that ACLY senses elevated glucose levels through O‐GlcNAc glycosylation, thereby enhancing lipid synthesis to promote the rapid proliferation of tumor cells [118]. Additionally, this O‐GlcNAc modification enhances the nuclear localization of SRPK2, regulates de novo lipid synthesis in tumor cells at the post‐transcriptional level, and consequently promotes tumor growth [119].

Recent studies have revealed that numerous molecules or signaling pathways can reprogram glucose metabolism in CRC, while simultaneously affecting the metabolism of various other substances (Table 1). In summary, the interplay among different metabolic reprogramming processes further promotes the progression of CRC through complex mechanisms. In recent years, research has increasingly focused on overall metabolic alterations in cancer. If their common upstream regulators could be inhibited, targeted metabolic therapies would achieve a significant improvement in efficiency (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Research progress on dual metabolic reprogramming in CRC.

| Target molecule | Metabolic impact | Related downstream molecules or pathways | Main function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FUT2 | Glucose and lipid |

YAP/TAZ signaling SREBP‐1 |

Promote proliferation and metastasis. | [120] |

| SCD1 | Glucose and lipid | — | Promote cancer development and progression. | [121] |

| PBX3 | Glucose, lipid, and nucleotide | G6PD | Promote proliferation and inhibit intracellular ROS and apoptosis. | [101] |

| ATF4 | Glucose and amino acid | SLC1A5 | Promote viability, migration, invasion, and metastasis. | [122] |

| GLUT5 | Glucose and lipid | AKT1/3‐miR‐125b‐5p | Induce migratory activity and drug resistance. | [123] |

| GLUT14 | Glucose and creatine | HIF1α | Promote proliferation. | [124] |

| ARL15 | Glucose & lipid | AKT/AMPK | Promote the occurrence of colon cancer. | [125] |

| CRMP2 | Glucose & lipid | GLUT4 | Regulate apoptosis/proliferation, cell migration and differentiation. | [126] |

| Maggot extracts | Glucose & lipid | HMOX1/GPX4 signaling pathway | Inhibit proliferation and induce ferroptosis. | [127] |

| PEPCK | Glucose & amino acid | mTORC1 | Promote proliferation. | [105] |

| ChREBP | Glucose & lipid | p53 pathway | Regulate proliferation and cell cycle arrest. | [128] |

| SIRT6 | Glucose & lipid | PKCζ | Regulate lipid homeostasis. | [129] |

| RARRES1 | Glucose & lipid | PPAR pathway | Regulate fatty acid metabolism in epithelial cells. | [130] |

| PLOD2 | Glucose & amino acid | STAT3 pathway;HK2 | Promote proliferation and invasiveness. | [131] |

| ADMA | Glucose & lipid, amino acid & nucleic acid | — | Regulate apoptosis and cell cycle. | [132] |

| RPIA | glucose & nucleic acid | CARM1 | Promote ROS clearance and growth. | [133] |

| ART1 | Glucose & amino acid | PI3K/AKT/HIF1α | Promote proliferation. | [134] |

| AMPK | Glucose & amino acid | PPARδ | Inhibit colon tumor growth. | [135] |

| c‐Src | Glucose & amino acid | PFKFB3 | Promote tumorigenesis and progression. | [136] |

| PFKFB4 | Glucose & amino acid | — | Regulate immune infiltration. | [137] |

| LINC01764 | Glucose & amino acid | c‐Myc | Promote proliferation, metastasis, and 5‐FU resistance. | [138] |

| LINC01615 | Glucose & lipid & nucleotide | G6PD | Promote proliferation and inhibit intracellular ROS and apoptosis. | [139] |

4. Therapeutics Targeting Glucose Metabolic Reprogramming

Targeting genes and proteins associated with glucose metabolic reprogramming can effectively inhibit the energy supply to tumor cells, disrupt key metabolic pathways, and utilize specific metabolic characteristics for targeted treatments [116, 140]. This approach holds significant promise and offers new insights and strategies for the treatment of CRC. This section introduces some of the latest research developments on the reprogramming of glucose metabolism in CRC cells.

Exogenous drugs or reagents have been employed in research on glucose metabolism. A class of drugs called mTOR inhibitors targets the rapamycin signaling pathway, effectively suppressing glucose metabolism in CRC cells. Inhibition of LDHA can sensitize CRC cells to rapamycin, and the combined use of rapamycin with the glycolysis inhibitor oxamate exhibits a potent inhibitory effect on CRC [141]. Xanthohumol (XN) is a prenylated flavonoid compound that is obtained primarily through extraction from hops. Low doses of XN can inhibit the proliferation and progression of HT29 cells by downregulating inflammatory signaling and cellular metabolism. Specifically, low doses of XN can suppress glucose and oxidative metabolism as well as lipid peroxidation with minimal effects on cell viability. Although researchers have indicated that strategies are being developed to increase the bioavailability of XN, this study has not yet been completed in terms of metabolic transformations [142].

2‐DG can enter the glycolytic metabolic pathway in cells and competitively inhibit the phosphorylation of glucose to glucose‐6‐phosphate, greatly reducing energy production. 2‐DG has a broad range of metabolic effects, including the depletion of cellular energy, intensification of oxidative stress, and interference with N‐linked glycosylation. It also activates various signaling pathways, such as the PI3K/AKT, MAPK, and AMPK pathways [143, 144, 145]. These events are interconnected to some extent and are collectively influential. The toxicity observed after treatment with 2‐DG was caused by one or more of the mechanisms mentioned above. Studies have shown that treating CRC cells resistant to chemotherapeutic drugs, such as 5‐fluorouracil or oxaliplatin, with 2‐DG can inhibit glycolytic enzymes in cells, reduce the invasive capability of tumor cells, and improve their resistance to drugs [146, 147, 148]. Nevertheless, the therapeutic efficacy of 2‐DG is limited by high‐dose systemic toxicity, and research into its resistance mechanisms has attracted attention. Recent studies have shown that 2‐DG inhibits glycolysis, which in turn increases the expression of thioredoxin‐1 (Trx‐1) in CRC cells. Trx‐1 overexpression can reduce the cytotoxicity of 2‐DG. Mechanistically, Trx‐1 increases glutathione (GSH) levels by modulating SLC1A5, thereby rescuing the cytotoxic effects of 2‐DG on CRC cells [149]. Combining glycolysis inhibition with Trx‐1 or SLC1A5 inhibition may be a promising strategy for the treatment of CRC.

Theoretically, endogenous molecules that are capable of inhibiting glucose metabolism are the best natural therapeutic agents. The active form of vitamin D, calcitriol, can inhibit glycolysis and tumor growth in human CRC cells [150]. Fructose‐2,6‐bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3) catalyzes the production of fructose‐2,6‐bisphosphate and acts as an oncogene, and its mechanism is linked to the expression of IL‐1β and TNF‐α. Inhibitors of PFKFB3 and PFK158 can reduce the survival rate, migration, and invasion of CRC cells caused by the overexpression of PFKFB3 [151]. Vitamin C induces ATP depletion and a decrease in the phosphorylation of pyruvate dehydrogenase E1‐α at serine 293, thereby increasing the activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and citrate synthase. Furthermore, vitamin C downregulated pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase‐1 (PDK‐1) in KRAS‐mutant CRC cells through prolyl hydroxylation (Pro402) of HIF‐1α, significantly affecting the TCA cycle and mitochondrial metabolism in multiple ways. Vitamin C may play a role in the clinical treatment of anti‐EGFR chemotherapy‐resistant CRC [152, 153]. In summary, endogenous glucose metabolism inhibitors not only directly suppress tumor cell growth but also increase the sensitivity of various tumors to chemotherapeutic drugs. Glycolysis inhibitors are targeted metabolic drugs that are closest to widespread clinical use, bringing hope to patients with advanced CRC.

Immune cells in CRC also undergo metabolic reprogramming. Using specific methods to help them adapt to the TME and function more effectively is also a therapeutic strategy. A P2A‐linked bicistronic vector named GT5‐19BBz was constructed to express GLUT5 and an anti‐CD19 CAR. GLUT5‐engineered CAR‐T cells more effectively utilize fructose in glucose‐restricted tumor environments, thereby increasing the activity of the TCA cycle and the pentose phosphate pathway. In a melanoma mouse model, GLUT5‐engineered T cells accumulated in the TME and inhibited tumor growth. Moreover, combination therapy with PD‐1/CTLA‐4 immune checkpoint inhibitors significantly improved the survival rate of tumor‐bearing mice [15]. In addition, studies targeting dendritic cells (DCs) have shown that NCoR1 mediates the regulation of glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation in DC cells, which is beneficial for their immune tolerance [154]. Combining immunotherapy with targeted metabolism can overcome the immunosuppressive microenvironment, enhance the function of immune cells, and improve the response rate of immunotherapy through multitarget collaboration. This approach is not only a hot topic of research in recent years, but is also set to become a new strategy for future cancer treatment.

Clinical studies have applied glucose metabolic reprogramming‐related genes as diagnostic and prognostic markers for CRC (Table 3). (https://clinicaltrials.gov/) Some of these studies have been completed, but many are still in the recruitment phase. Metabolic imaging techniques such as FDG‐PET have been employed in many clinical trials. FDG‐PET is a molecular imaging technology that combines positron emission tomography (PET) and computed tomography (CT). It can reflect the metabolic activity of tumor cells by detecting their glucose uptake. By analyzing the distribution of FDG uptake, researchers can better understand the metabolic characteristics of CRC and provide a basis for personalized treatment.

TABLE 3.

Clinical trials on metabolic alterations in CRC.

| NCT number | Official title | Study status | Conditions | Interventions | Primary outcome measures | Enrollment | Study type | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04516681 | Vitamin C intravenously with chemotherapy and Adebrelimab in metastatic colorectal cancer with high expresison level of GLUT3. | Recruiting |

Colorectal Cancer Vitamin C GLUT3 |

Ascorbic acid FOLFOX protocol Adebrelimab |

Target response rate, which refers to the total tumor response rate of subjects receiving combination therapy of ascorbic acid and FOLFOX RI+/− bevacizumab versus receiving the latter alone. | 400 | Interventional | Treatment |

| NCT01591590 | Correlating the tumoral metabolic progression index measured by serial FDG‐PET CT and apparent diffusion coefficient measured by MRI to patient's outcome in advanced colorectal cancer. | Completed | Colorectal Cancer |

FDG PET‐CT MRI |

Mortality, 12 months. | 53 | Interventional | Diagnosis |

| NCT00184782 | Exploratory study on FDG‐PET scanning in evaluating the metabolic activity of liver metastases before and after resection of the primary tumor in patients with a colorectal malignancy. | Unknown | Colorectal Neoplasms | FDG‐PET | Increase in metabolic activity of liver metastases after resection of the primary tumor compared to the activity of metastases in patients without primary tumor resection. | 30 | Interventional | Diagnosis |

| NCT06011473 | Continuous glucose monitoring for colorectal cancer. | Recruiting |

Continuous Glucose Monitoring Colorectal Cancer |

CGM (FreeStyle Libre 3) | Feasibility of CGM system. | 40 | Interventional | Supportive care |

| NCT02700555 | Surveillance of metabolic parameters in patients who will receive chemotherapy after surgical resection of colorectal cancer: KBSMC colon cancer cohort. | Terminated | Colorectal Cancer | — | Incidence of newly developed diabetes mellitus in patients with colorectal cancer after post‐operative chemotherapy, up to 12 months. | 23 | Observational | Supportive care |

| NCT06614660 | Multimodality metabolism and imaging genomics model for predicting the short‐term and long‐term outcomes for colorectal cancer patients. |

Active Not recruiting |

Colorectal Cancer | Metabolism genomics and imaging genomics | Overall survival, assessed up to 60 months. | 800 | Observational |

Prognosis biomarker |

| NCT06117241 | A transdisciplinary approach to investigating metabolic and risk of early‐onset colorectal cancer: a randomized intervention trial in human dyads and mechanistic study in animals. | Recruiting | Colorectal Cancer | Imagine healthy | Blood, TNFα, IL‐6, CRP, reversal of metabolic dysfunction, Baseline, 3‐month, 6‐month. | 180 | Interventional | Prevention |

| NCT01426490 | The effects of vitamin B‐6 status on homocysteine, oxidative stress, one‐carbon metabolism and methylation: cross‐section, case–control, intervention and follow‐up studies in colorectal cancer. | Unknown | Colorectal Cancer | Dietary supplement | The oxidative stress (TBARs), antioxidant activities and DNA methylation in colorectal cancer patients, 12 months. | 300 | Intervention | Prevention |

| NCT06643429 | Impact of environmental factors and metabolomics on colorectal cancer development and prognosis based on environmental factors and metabolomics. |

Active Not recruiting |

Colorectal Cancer Metabolic Disease |

Diagnostic test: colorectal cancer | Rate of postoperative complications, assessed up to 2 months after surgery. | 700 | Observational | Diagnosis |

| NCT00394615 | Metabolic imaging: predicting histopathologic response to preoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. | Terminated | Rectal Cancer | Metabolic imaging | To learn whether new medical imaging technology can help predict the response of rectal cancer to preoperative chemotherapy and radiation therapy. | 15 | Intervention | Treatment |

Changes in enzyme activity resulting from metabolic reprogramming are key factors in the pathogenesis of CRC and in its adaptive stress response. Modulation of these metabolic enzymes significantly improves treatment outcomes and survival rates in patients with cancer. Extensive research has confirmed the viability of targeting the key genes and proteins involved in the reprogramming of glucose metabolism. Combining targeted therapy with other treatments has a positive impact on limiting malignant tumors and contributes to improving patient prognosis and survival rates.

5. Conclusion and Perspective

Metabolic reprogramming is an intrinsic mechanism in tumor cells, and almost all types of tumors exhibit several common metabolic alterations, especially alterations in glucose metabolism. CRC cells consume a substantial amount of glucose and produce lactate via the Warburg effect to meet their continuous energy demands. Increased lactate production also contributes to immunosuppression. In CRC, the tricarboxylic acid cycle is downregulated and associated with cellular cuproptosis (Figure 1). The levels of OXPHOS are also reduced, affecting multiple signaling pathways and immunotherapy in CRC cells. Upregulation of the pentose phosphate pathway generates reducing equivalents to counteract the oxidative stress encountered by rapidly proliferating cancer cells. Gluconeogenesis and glycogen metabolism also exhibit a certain degree of reprogramming to meet high energy and biosynthesis demands (Figure 2).

Similar to other malignant tumors, the development and progression of CRC necessitate metabolic activities distinct from those of normal cells. CRC cells undergo metabolic reprogramming of glucose to acquire the additional energy necessary for their growth and proliferation, establishing a TME conducive to invasion and metastasis, thus facilitating the rapid proliferation of the cell population. In recent years, further insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the development and progression of CRC have emerged, particularly into the pathways associated with tumor growth metabolism. Glucose metabolic reprogramming also affects the treatment of CRC, with therapies targeting metabolism having significant research potential. Inhibiting key metabolic pathways not only slows the rate of tumor cell proliferation and spread but also increases resistance to chemotherapy and enhances the efficacy of immunotherapy [155].

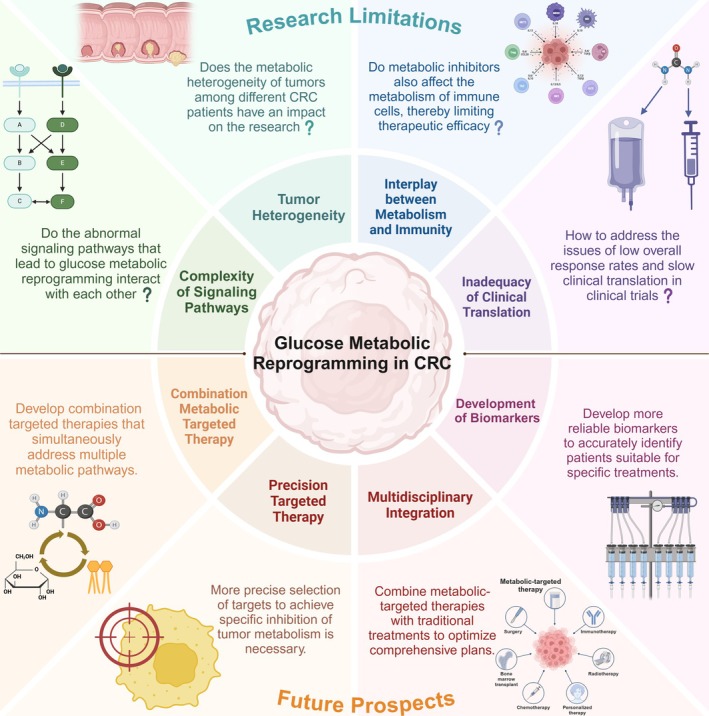

Despite the many advances in the study of CRC metabolomics, research on the interrelationships between the various signaling pathways that affect glucose metabolism in CRC remains incomplete. Moreover, the impact of metabolic reprogramming on the TME and tumor immunity is a valuable research direction, but there is currently a scarcity of clinical translation in this area [156, 157]. Under physiological conditions, the metabolism of different nutrients is interconnected and can be interconverted, a phenomenon that is even more pronounced in tumors. In recent years, an increasing number of studies have revealed the interactions between glucose metabolism and lipid or amino acid metabolism. Future research should continue to focus on precise biomarkers and targeting points that can simultaneously modulate the metabolism of multiple substances. Owing to insufficient validation in clinical trials, uncertainties and limitations exist in the treatment of targeted metabolism. These potential limitations include effects on the metabolism and biosynthesis of normal cells, which could lead to adverse reactions and side effects in patients. Considering that such treatment may require a sustained period to achieve efficacy, long‐term therapy could result in increased drug tolerance and treatment costs for patients. Additionally, more thought should be given to how to integrate metabolism‐targeting therapies with traditional cancer treatments to devise better comprehensive treatment plans for CRC patients. In summary, although there are numerous studies on glucose metabolism reprogramming and its clinical applications, many challenges and issues remain to be addressed (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

The current challenges in basic and clinical research on glucose metabolic reprogramming in CRC, as well as the key issues that future research should prioritize.

As genomics, energy metabolism, and other theories and technologies have advanced, we anticipate uncovering more CRC‐related metabolic characteristics. This progress will enable the development of efficient and safe targeted drugs for clinical application. In summary, by deepening our understanding of the metabolic mechanisms of glucose, we aim to prevent, diagnose, and treat CRC from a metabolic perspective, thereby further improving the cure rate and survival time of patients with CRC.

Author Contributions

R.Z. organized the literature and drafted the manuscript. F.W. and J.W. made the mechanism diagram. X.Z. and Y.W. provided critical comments and supervised this study. All authors contributed to the writing, review, and editing of the original draft and validated the final manuscript.

Disclosure

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria: We searched PubMed for review articles published in English between January 1, 2015, and April 26, 2024, which included “Colorectal Neoplasms” with “Metabolic Reprogramming” OR “Glucose Metabolism Disorders” OR “The Warburg Effect” OR “Targeted Therapy.” We also searched the reference lists of the articles identified by this search strategy and selected those that were judged to be relevant. Review articles provide readers with an overview of some aspects of glucose metabolism mechanisms. As this article presents the discovery and historical evolution of the Warburg effect theory, it cites a small number of older publications.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jingyi Zhou, Qingshan Luo, and Jinfeng Cai from the Shanghai General Hospital for their valuable comments.

Zhou R., Wang F., Wen J., Zhou X., and Wen Y., “Glucose Metabolic Reprogramming in Colorectal Cancer: From Mechanisms to Targeted Therapy Approaches,” Cancer Medicine 14, no. 17 (2025): e71185, 10.1002/cam4.71185.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81972215 to Yugang Wen).

Contributor Information

Xuefeng Zhou, Email: dtzxf4490@163.com.

Yugang Wen, Email: wenyg1502@hotmail.com.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

- 1. Siegel R. L., Giaquinto A. N., and Jemal A., “Cancer Statistics, 2024,” CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 74, no. 1 (2024): 12–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dekker E., Tanis P. J., Vleugels J. L. A., Kasi P. M., and Wallace M. B., “Colorectal Cancer,” Lancet 394, no. 10207 (2019): 1467–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R. L., et al., “Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries,” CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 71, no. 3 (2021): 209–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Biller L. H. and Schrag D., “Diagnosis and Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Review,” JAMA 325, no. 7 (2021): 669–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yang J., Shay C., Saba N. F., and Teng Y., “Cancer Metabolism and Carcinogenesis,” Experimental Hematology & Oncology 13, no. 1 (2024): 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yang F., Hilakivi‐Clarke L., Shaha A., et al., “Metabolic Reprogramming and Its Clinical Implication for Liver Cancer,” Hepatology 78, no. 5 (2023): 1602–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miao D., Wang Q., Shi J., et al., “N6‐Methyladenosine‐Modified DBT Alleviates Lipid Accumulation and Inhibits Tumor Progression in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Through the ANXA2/YAP Axis‐Regulated Hippo Pathway,” Cancer Commun (London) 43, no. 4 (2023): 480–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Parida P. K., Marquez‐Palencia M., Ghosh S., et al., “Limiting Mitochondrial Plasticity by Targeting DRP1 Induces Metabolic Reprogramming and Reduces Breast Cancer Brain Metastases,” Nature Cancer 4, no. 6 (2023): 893–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sun J., Ding J., Shen Q., et al., “Decreased Propionyl‐CoA Metabolism Facilitates Metabolic Reprogramming and Promotes Hepatocellular Carcinoma,” Journal of Hepatology 78, no. 3 (2023): 627–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bruno G., Li Bergolis V., Piscazzi A., et al., “TRAP1 Regulates the Response of Colorectal Cancer Cells to Hypoxia and Inhibits Ribosome Biogenesis Under Conditions of Oxygen Deprivation,” International Journal of Oncology 60, no. 6 (2022): 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Montero‐Calle A., Gomez de Cedron M., Quijada‐Freire A., et al., “Metabolic Reprogramming Helps to Define Different Metastatic Tropisms in Colorectal Cancer. Front,” Oncologia 12 (2022): 903033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lin J. F., Hu P. S., Wang Y. Y., et al., “Phosphorylated NFS1 Weakens Oxaliplatin‐Based Chemosensitivity of Colorectal Cancer by Preventing PANoptosis,” Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 7, no. 1 (2022): 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tang R., Xu J., Wang W., et al., “Targeting Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy‐Induced Metabolic Reprogramming in Pancreatic Cancer Promotes Anti‐Tumor Immunity and Chemo‐Response,” Cell Reports Medicine 4, no. 10 (2023): 101234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang M., Wu Y., Cheng L., et al., “Multi‐Omics Analyses of Glucose Metabolic Reprogramming in Colorectal Cancer,” Frontiers in Immunology 14 (2023): 1179699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schild T., Wallisch P., Zhao Y., et al., “Metabolic Engineering to Facilitate Anti‐Tumor Immunity,” Cancer Cell 43, no. 3 (2025): 552–562.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lu X., Liu J., Feng L., et al., “BATF Promotes Tumor Progression and Association With FDG PET‐Derived Parameters in Colorectal Cancer,” Journal of Translational Medicine 22, no. 1 (2024): 558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wyart E., Carrà G., Angelino E., Penna F., and Porporato P. E., “Systemic Metabolic Crosstalk as Driver of Cancer Cachexia,” Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism, ahead of print, January 4, 2025, 10.1016/j.tem.2024.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18. Lin J., Xia L., Oyang L., et al., “The POU2F1‐ALDOA Axis Promotes the Proliferation and Chemoresistance of Colon Cancer Cells by Enhancing Glycolysis and the Pentose Phosphate Pathway Activity,” Oncogene 41, no. 7 (2022): 1024–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Warburg O., Wind F., and Negelein E., “The Metabolism of Tumors in the Body,” Journal of General Physiology 8, no. 6 (1927): 519–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Crabtree H. G., “Observations on the Carbohydrate Metabolism of Tumours,” Biochemical Journal 23, no. 3 (1929): 536–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Warburg O., “On the Origin of Cancer Cells,” Science 123, no. 3191 (1956): 309–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Racker E., “Bioenergetics and the Problem of Tumor Growth,” American Scientist 60, no. 1 (1972): 56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Racker E., “Resolution and Reconstitution of Biological Pathways From 1919 to 1984,” Federation Proceedings 42, no. 12 (1983): 2899–2909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hiraki Y., Rosen O. M., and Birnbaum M. J., “Growth Factors Rapidly Induce Expression of the Glucose Transporter Gene,” Journal of Biological Chemistry 263, no. 27 (1988): 13655–13662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boerner P., Resnick R. J., and Racker E., “Stimulation of Glycolysis and Amino Acid Uptake in NRK‐49F Cells by Transforming Growth Factor Beta and Epidermal Growth Factor,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 82, no. 5 (1985): 1350–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fantin V. R., St‐Pierre J., and Leder P., “Attenuation of LDH‐A Expression Uncovers a Link Between Glycolysis, Mitochondrial Physiology, and Tumor Maintenance,” Cancer Cell 9, no. 6 (2006): 425–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jing Z., Liu Q., He X., et al., “NCAPD3 Enhances Warburg Effect Through c‐Myc and E2F1 and Promotes the Occurrence and Progression of Colorectal Cancer,” Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 41, no. 1 (2022): 198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang Z., Li X., Liu W., et al., “Polyphenol Nanocomplex Modulates Lactate Metabolic Reprogramming and Elicits Immune Responses to Enhance Cancer Therapeutic Effect,” Drug Resistance Updates 73 (2024): 101060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Offermans K., Jenniskens J. C. A., Simons C., et al., “Association Between Mutational Subgroups, Warburg‐Subtypes, and Survival in Patients With Colorectal Cancer,” Cancer Medicine 12, no. 2 (2023): 1137–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhu Z., Qin J., Dong C., et al., “Identification of Four Gastric Cancer Subtypes Based on Genetic Analysis of Cholesterogenic and Glycolytic Pathways,” Bioengineered 12, no. 1 (2021): 4780–4793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yu M., Zhou Q., Zhou Y., et al., “Metabolic Phenotypes in Pancreatic Cancer,” PLoS One 10, no. 2 (2015): e0115153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Offermans K., Jenniskens J. C., Simons C. C., et al., “Expression of Proteins Associated With the Warburg‐Effect and Survival in Colorectal Cancer,” Journal of Pathology: Clinical Research 8, no. 2 (2022): 169–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Steeghs J., Offermans K., Jenniskens J. C. A., et al., “Relationship Between the Warburg Effect in Tumour Cells and the Tumour Microenvironment in Colorectal Cancer Patients: Results From a Large Multicentre Study,” Pathology, Research and Practice 247 (2023): 154518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Offermans K., Jenniskens J. C. A., Simons C., et al., “Association Between Adjuvant Therapy and Survival in Colorectal Cancer Patients According to Metabolic Warburg‐Subtypes,” Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 149, no. 9 (2023): 6271–6282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Abi Zamer B., Abumustafa W., Hamad M., Maghazachi A. A., and Muhammad J. S., “Genetic Mutations and Non‐Coding RNA‐Based Epigenetic Alterations Mediating the Warburg Effect in Colorectal Carcinogenesis,” Biology (Basel) 10, no. 9 (2021): 847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li C., Chen Q., Zhou Y., et al., “S100A2 Promotes Glycolysis and Proliferation via GLUT1 Regulation in Colorectal Cancer,” FASEB Journal 34, no. 10 (2020): 13333–13344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dai W., Xu Y., Mo S., et al., “GLUT3 Induced by AMPK/CREB1 Axis Is Key for Withstanding Energy Stress and Augments the Efficacy of Current Colorectal Cancer Therapies,” Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 5, no. 1 (2020): 177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Libby C. J., Gc S., Benavides G. A., et al., “A Role for GLUT3 in Glioblastoma Cell Invasion That Is Not Recapitulated by GLUT1,” Cell Adhesion & Migration 15, no. 1 (2021): 101–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yang M., Guo Y., Liu X., and Liu N., “HMGA1 Promotes Hepatic Metastasis of Colorectal Cancer by Inducing Expression of Glucose Transporter 3 (GLUT3),” Medical Science Monitor 26 (2020): e924975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ke B. and Ye K., “SETD8 Promotes Glycolysis in Colorectal Cancer via Regulating HIF1α/HK2 Axis,” Tissue & Cell 82 (2023): 102065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bai Z., Lu Z., Liu R., et al., “Iguratimod Restrains Circulating Follicular Helper T Cell Function by Inhibiting Glucose Metabolism via Hif1α‐HK2 Axis in Rheumatoid Arthritis,” Frontiers in Immunology 13 (2022): 757616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kang S. W., Lee S., and Lee E. K., “ROS and Energy Metabolism in Cancer Cells: Alliance for Fast Growth,” Archives of Pharmacal Research 38, no. 3 (2015): 338–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang C., Cao S., Toole B. P., and Xu Y., “Cancer May Be a Pathway to Cell Survival Under Persistent Hypoxia and Elevated ROS: A Model for Solid‐Cancer Initiation and Early Development,” International Journal of Cancer 136, no. 9 (2015): 2001–2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pak J. N., Lee H. J., Sim D. Y., et al., “Anti‐Warburg Effect via Generation of ROS and Inhibition of PKM2/β‐Catenin Mediates Apoptosis of Lambertianic Acid in Prostate Cancer Cells,” Phytotherapy Research 37, no. 9 (2023): 4224–4235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hart P. C., Mao M., de Abreu A. L., et al., “MnSOD Upregulation Sustains the Warburg Effect via Mitochondrial ROS and AMPK‐Dependent Signalling in Cancer,” Nature Communications 6 (2015): 6053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Holley A. K., Dhar S. K., and St Clair D. K., “Curbing Cancer's Sweet Tooth: Is There a Role for MnSOD in Regulation of the Warburg Effect?,” Mitochondrion 13, no. 3 (2013): 170–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mc Cluskey M., Dubouchaud H., Nicot A. S., and Saudou F., “A Vesicular Warburg Effect: Aerobic Glycolysis Occurs on Axonal Vesicles for Local NAD+ Recycling and Transport,” Traffic 25, no. 1 (2024): e12926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Luengo A., Li Z., Gui D. Y., et al., “Increased Demand for NAD (+) Relative to ATP Drives Aerobic Glycolysis,” Molecular Cell 81, no. 4 (2021): 691–707.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yaku K., Okabe K., Hikosaka K., and Nakagawa T., “NAD Metabolism in Cancer Therapeutics,” Frontiers in Oncology 8 (2018): 622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. El Sayed S. M., “Biochemical Origin of the Warburg Effect in Light of 15 Years of Research Experience: A Novel Evidence‐Based View (An Expert Opinion Article),” OncoTargets and Therapy 16 (2023): 143–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Inoue M., Nakagawa Y., Azuma M., et al., “The PKM2 Inhibitor Shikonin Enhances Piceatannol‐Induced Apoptosis of Glyoxalase I‐Dependent Cancer Cells,” Genes to Cells 29, no. 1 (2024): 52–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhao G., Yuan H., Li Q., et al., “DDX39B Drives Colorectal Cancer Progression by Promoting the Stability and Nuclear Translocation of PKM2,” Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 7, no. 1 (2022): 275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yin C., Lu W., Ma M., et al., “Efficacy and Mechanism of Combination of Oxaliplatin With PKM2 Knockdown in Colorectal Cancer,” Oncology Letters 20, no. 6 (2020): 312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shi J., Ji X., Shan S., Zhao M., Bi C., and Li Z., “The Interaction Between Apigenin and PKM2 Restrains Progression of Colorectal Cancer,” Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 121 (2023): 109430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yan S. H., Hu L. M., Hao X. H., et al., “Chemoproteomics Reveals Berberine Directly Binds to PKM2 to Inhibit the Progression of Colorectal Cancer,” IScience 25, no. 8 (2022): 104773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yu S., Zang W., Qiu Y., Liao L., and Zheng X., “Deubiquitinase OTUB2 Exacerbates the Progression of Colorectal Cancer by Promoting PKM2 Activity and Glycolysis,” Oncogene 41, no. 1 (2022): 46–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang W., Zhang X., Huang S., et al., “FOXM1D Potentiates PKM2‐Mediated Tumor Glycolysis and Angiogenesis,” Molecular Oncology 15, no. 5 (2021): 1466–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Liu X. S., Chen Y. X., Wan H. B., et al., “TRIP6 a Potential Diagnostic Marker for Colorectal Cancer With Glycolysis and Immune Infiltration Association,” Scientific Reports 14, no. 1 (2024): 4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chen B., Deng Y., Hong Y., et al., “Metabolic Recoding of NSUN2‐Mediated m(5)C Modification Promotes the Progression of Colorectal Cancer via the NSUN2/YBX1/m(5)C‐ENO1 Positive Feedback Loop,” Advanced Science (Weinheim) 11, no. 28 (2024): e2309840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gamage C. D. B., Kim J. H., Zhou R., et al., “Plectalibertellenone A Suppresses Colorectal Cancer Cell Motility and Glucose Metabolism by Targeting TGF‐β/Smad and Wnt Pathways,” BioFactors 51, no. 1 (2025): e2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Shaha A., Wang Y., Wang X., et al., “CMTM6 Mediates the Warburg Effect and Promotes the Liver Metastasis of Colorectal Cancer,” Experimental & Molecular Medicine 56, no. 9 (2024): 2002–2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhou B., Fan Z., He G., et al., “SHP2 Mutations Promote Glycolysis and Inhibit Apoptosis via PKM2/hnRNPK Signaling in Colorectal Cancer,” IScience 27, no. 8 (2024): 110462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hou J. Y., Wang X. L., Chang H. J., et al., “PTBP1 Crotonylation Promotes Colorectal Cancer Progression Through Alternative Splicing‐Mediated Upregulation of the PKM2 Gene,” Journal of Translational Medicine 22, no. 1 (2024): 995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Jin Y., Jiang A., Sun L., and Lu Y., “Long Noncoding RNA TMPO‐AS1 Accelerates Glycolysis by Regulating the miR‐1270/PKM2 Axis in Colorectal Cancer,” BMC Cancer 24, no. 1 (2024): 238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zhou J., Sun H., Zhou H., and Liu Y., “SPAG4 Enhances Mitochondrial Respiration and Aerobic Glycolysis in Colorectal Cancer Cells by Activating the PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway,” Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology 38, no. 11 (2024): e70009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cui F., Chen Y., Wu X., and Zhao W., “Mesenchymal Stem Cell‐Derived Exosomes Carrying miR‐486‐5p Inhibit Glycolysis and Cell Stemness in Colorectal Cancer by Targeting NEK2,” BMC Cancer 24, no. 1 (2024): 1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zhao L., Yu N., Zhai Y., et al., “The Ubiquitin‐Like Protein UBTD1 Promotes Colorectal Cancer Progression by Stabilizing c‐Myc to Upregulate Glycolysis,” Cell Death & Disease 15, no. 7 (2024): 502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Jiang C., Sun L., Wen S., et al., “BRIX1 Promotes Ribosome Synthesis and Enhances Glycolysis by Selected Translation of GLUT1 in Colorectal Cancer,” Journal of Gene Medicine 26, no. 1 (2024): e3632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Xing Y., Lin B., Liu B., Shao J., and Jin Z., “Tectorigenin Inhibits Glycolysis‐Induced Cell Growth and Proliferation by Modulating LncRNA CCAT2/miR‐145 Pathway in Colorectal Cancer,” Current Cancer Drug Targets 24, no. 10 (2024): 1071–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Xiang L., Wei H., Ye W., Wu S., and Xie G., “Prolyl Hydroxylase 2 Inhibits Glycolytic Activity in Colorectal Cancer via the NF‐κB Signaling Pathway,” International Journal of Oncology 64, no. 1 (2024): 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Song T., Zhang X., Ren J., Hu Z., Wang X., and Niu G., “SELENBP1 Inhibits the Warburg Effect and Tumor Growth by Reducing the HIF1α Expression in Colorectal Cancer,” Current Cancer Drug Targets, ahead of print, September 12, 2024, 10.2174/0115680096320837240806172245. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72. Zhou J., Xu W., Wu Y., et al., “GPR37 Promotes Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases by Enhancing the Glycolysis and Histone Lactylation via Hippo Pathway,” Oncogene 42, no. 45 (2023): 3319–3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. He X., Zhong X., Fang Y., et al., “AF9 Sustains Glycolysis in Colorectal Cancer via H3K9ac‐Mediated PCK2 and FBP1 Transcription,” Clinical and Translational Medicine 13, no. 8 (2023): e1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Zhang L., Jiang C., Zhong Y., et al., “STING Is a Cell‐Intrinsic Metabolic Checkpoint Restricting Aerobic Glycolysis by Targeting HK2,” Nature Cell Biology 25, no. 8 (2023): 1208–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gao Y., Wang Y., Wang X., et al., “FABP4 Regulates Cell Proliferation, Stemness, Apoptosis, and Glycolysis in Colorectal Cancer via Modulating ROS/ERK/mTOR Pathway,” Discovery Medicine 35, no. 176 (2023): 361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Chen H. Y., Li X. N., Yang L., Ye C. X., Chen Z. L., and Wang Z. J., “CircVMP1 Promotes Glycolysis and Disease Progression by Upregulating HKDC1 in Colorectal Cancer,” Environmental Toxicology 39, no. 3 (2024): 1617–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Huang S., Wang X., Zhu Y., Wang Y., Chen J., and Zheng H., “SOX2 Promotes Vasculogenic Mimicry by Accelerating Glycolysis via the lncRNA AC005392.2‐GLUT1 Axis in Colorectal Cancer,” Cell Death & Disease 14, no. 12 (2023): 791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]