Abstract

Objectives To develop and implement an educational outreach programme for the integrated case management of priority respiratory diseases (practical approach to lung health in South Africa; PALSA) and to evaluate its effects on respiratory care and detection of tuberculosis among adults attending primary care clinics.

Design Pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial, with clinics as the unit of randomisation.

Setting 40 primary care clinics, staffed by nurse practitioners, in the Free State province, South Africa.

Participants 1999 patients aged 15 or over with cough or difficult breathing (1000 in intervention clinics, 999 in control clinics).

Intervention Between two and six educational outreach sessions delivered to nurse practitioners by usual trainers from the health department. The emphasis was on key messages drawn from the customised clinical practice guideline for the outreach programme, with illustrative support materials.

Main outcome measures Sputum screening for tuberculosis, tuberculosis case detection, inhaled corticosteroid prescriptions for obstructive lung disease, and antibiotic prescriptions for respiratory tract infections.

Results All clinics and almost all patients (92.8%, 1856/1999) completed the trial. Although sputum testing for tuberculosis was similar between the groups (22.6% in outreach group v 19.3% in control group; odds ratio 1.22, 95% confidence interval 0.83 to 1.80), the case detection of tuberculosis was higher in the outreach group (6.4% v 3.8%; 1.72, 1.04 to 2.85). Prescriptions for inhaled corticosteroids were also higher (13.7% v 7.7%; 1.90, 1.14 to 3.18) but the number of antibiotic prescriptions was similar (39.7% v 39.4%; 1.01, 0.74 to 1.38).

Conclusions Combining educational outreach with integrated case management provides a promising model for improving quality of care and control of priority respiratory diseases, without extra staff, in resource poor settings.

Trial registration Current controlled trials ISRCTN13438073.

Introduction

Tuberculosis, driven largely by the HIV/AIDS epidemic, is a growing problem in lower and middle income countries, including South Africa.1-3 The World Health Organization estimates that about two thirds of people with tuberculosis are never diagnosed as having the disease and so cannot benefit from treatment,4 leaving the epidemic unchecked despite increasing global coverage by treatment programmes.5

Improved passive case detection is fundamental to the control of the tuberculosis epidemic and depends on alert clinicians identifying tuberculosis in patients seeking primary care for respiratory symptoms.6 In South Africa such patients account for one third of ambulatory visits and usually receive initial care from a nurse practitioner at a public sector clinic. Among these patients, asthma is undertreated,7,8 antibiotics are overprescribed,9,10 and tuberculosis is underdiagnosed.4

The DOTS Expansion Working Group considers the lack of trained staff to be the most important constraint on the control of tuberculosis.11 We recognised that knowledge translation strategies, increasingly used to close gaps between evidence and practice in the developed world,12 might improve quality of care in South Africa within existing constraints on human resources. We developed a syndromic case management intervention for respiratory illness in adults6 and implemented it in the Free State province, South Africa, using educational outreach visits to nurse practitioners in primary care clinics by specially trained nurse supervisors.

Methods

We used a pragmatic cluster randomised design for our trial. Pragmatic trials evaluate the effects of health service interventions under the human, financial, and logistic constraints of typical, real world situations.13,14 The unit of randomisation was the clinic, although we collected outcome data from individual patients.

Intervention

Educational outreach (non-commercial, short, face to face, in-service interactive education by a trusted outsider) is an effective strategy for promoting evidence based choices among physicians (median improvement 6%, range -4% to 17%).15 We selected this model (box) over off-site education because it was sustainable, drawing on and expanding the educational role of existing supervisory staff, and because it minimised disruption in understaffed front line facilities.

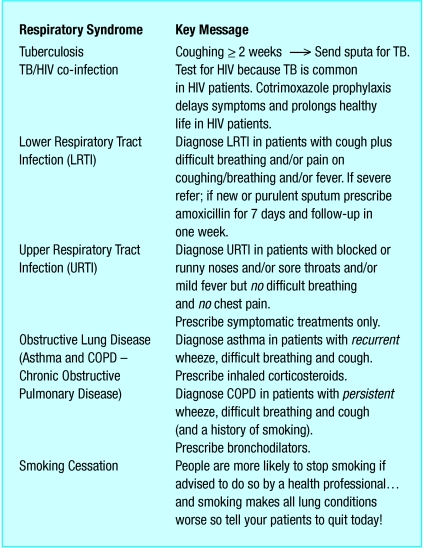

We developed an algorithmic guideline using symptoms and simple signs for the diagnosis and management of respiratory diseases in adults, including tuberculosis, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, acute upper and lower respiratory tract infections, and opportunistic infections in patients with HIV. We collaborated with front line clinicians and managers to ensure local applicability and consistency with national tuberculosis policies16 and essential drugs lists.17 We incorporated key messages from the guideline (fig 1 and see bmj.com) into a colourful, illustrated flip chart for use by the nurse trainers during educational outreach visits, and into a desk blotter (see bmj.com) for the nurse practitioners whom they trained. These were tested in pilot sites and adapted before implementation.

Fig 1.

Key messages as presented to front line nurses

Eight senior nurses running the tuberculosis programme attended a five day workshop on the techniques of interactive educational outreach and the clinical content of the guidelines, especially the key messages. They were to deliver three or four educational outreach sessions, each lasting one to three hours to all clinical staff, in groups, in each of their intervention clinics over a three month period.

The Free State department of health permitted nurse practitioners in intervention clinics to newly prescribe inhaled corticosteroids for asthma (with review by a physician within one month), short course oral corticosteroids for exacerbations of obstructive lung disease, and cotrimoxazole prophylaxis for symptomatic HIV infection. The nurses had long been permitted to renew physician initiated prescriptions.

Components of the practical approach to lung health in South Africa (PALSA) intervention

A median of two educational outreach sessions to groups of primary care nurse practitioners delivered by trained nurse supervisors

Expanded prescribing provisions for nurse practitioners to include inhaled corticosteroids for asthma, short course oral corticosteroids for exacerbations of obstructive lung disease, and cotrimoxazole prophylaxis for symptomatic HIV infection

Illustrated support materials for outreach sessions: flip chart for nurse trainers and desk blotters (incorporating key messages) for the nurse practitioners they trained

Locally tailored, evidence based, brief (22 pages), symptom and sign based guideline on common respiratory conditions in adults (tuberculosis, TB/HIV coinfection, respiratory tract infections, and obstructive lung disease)

Control clinics received no new training. Usual off-site training, received by fewer than 5% of staff each year, continued in both groups.

Participants and randomisation

The estimated prevalence of HIV among people attending antenatal clinics in impoverished communities of the Free State, predominantly in rural areas with high rates of tuberculosis and HIV (tuberculosis notification rate (all cases) 494/100 000 in 2002),18 was 30.1% in 2003.19 On a typical day around 200 people attend one of these clinics; about one third of these are children. A clinic is staffed by a median of nine nurses, some of whom see only children or pregnant women. Problem cases are referred to doctors who visit weekly.

On the basis of total annual attendances, we included in our study the 40 largest eligible primary care clinics. Randomisation was stratified by district. Clinics were ranked by size and allocated to intervention or control arms using a random number table in blocks of four. Allocation was carried out by a trial statistician before intervention or patient recruitment.

Patient recruitment

In each clinic waiting room a trained fieldworker screened all adult patients, independent of the nurse practitioners, for cough or difficult breathing on presentation or within the past six months. Patients aged 15 years or over who answered yes to either query and who were willing to take part in the study, were invited to meet the research team after their consultation with the nurse. Fieldworkers then obtained written consent and interviewed patients with any one of the following: difficult breathing on the day of interview or during the past six months; current cough for seven days or more; recurrent cough in the past six months; and current cough with a temperature above 38°C or a respiratory rate of 30 breaths per minute or more. We excluded patients who had been urgently referred elsewhere by their nurse practitioner. Recruitment began one month after the start of educational outreach and lasted one week in each clinic, with clinics staggered over five months (May to September 2003).

Data collection

Fieldworkers interviewed patients after their consultation, and three months later by appointment. Interviews were carried out in one of the five local languages, chosen by the patient. The questionnaire was translated in accordance with internationally accepted practices.20 Patient held records and dispensed drugs were examined and, for patients with tuberculosis cards, details were noted.

Patients and fieldworkers were blind to the intervention status of each clinic. Nurse trainers and nurse practitioners allocated to the intervention arm could not be blinded for obvious reasons.

Outcome measures and sample size calculations

For tuberculosis, the primary goal was to increase case detection, documented on the tuberculosis card or by patient report; in South Africa this diagnosis is based on the results of sputum microscopy, or culture.16 Sputum testing for tuberculosis was indicated by patient report. For obstructive lung disease, the primary goal was to improve therapy, indicated by prescriptions for inhaled corticosteroids. Receiving counselling for smoking cessation and stopping smoking were indicated by patient report. For respiratory tract infections, the primary goal was to rationalise prescribing, indicated by antibiotic prescription. Improved care of HIV/AIDS was indicated by the number of patients receiving voluntary counselling and testing, and by cotrimoxazole prescription among patients with tuberculosis. Appropriate referral of patients with severe disease (indicated by any of the following: temperature 3 38°C, respiratory rate over 30 breaths per minute, breathlessness at rest, use of accessory muscles) was measured by patient reported referral to a doctor. Outcomes were assessed one and four months after the intervention began and were deemed present if reported at either interview.

In advance of the trial, policymakers specified the minimal important improvement for the case detection of tuberculosis by the health service to be 25%. Our initial sample size calculations showed that too few patients with tuberculosis would attend within a feasible study duration to detect this difference. We therefore selected as a surrogate the more common measure of sputum sampling for tuberculosis. One thousand patients per arm provided 90% power (α = 0.05) to detect 10% improvements in sputum screening for tuberculosis and inhaled corticosteroid prescriptions, and a 10% reduction in antibiotic prescriptions. We assumed an intra-clinic correlation coefficient of 0.02.21

Statistical analysis

We analysed outcomes on an intention to treat basis. To evaluate the effect of the intervention with stratification as a cofactor, we used a logistic regression model. The model parameters were estimated by the generalised estimating equations approach, which takes into account the clustering of patients within clinics. Odds ratios are presented with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

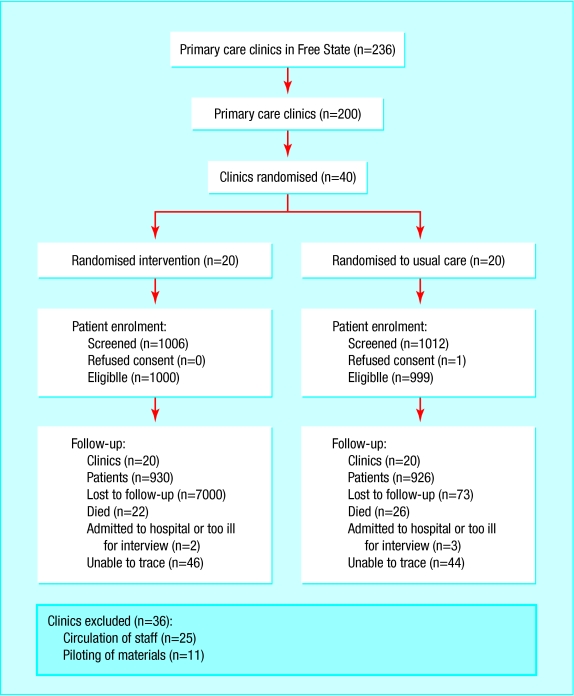

All 40 clinics completed the trial (fig 2). The characteristics of the patients at enrolment were similar between the groups (table 1).

Fig 2.

Trial profile

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients and clinics allocated to an educational outreach programme (practical approach to lung health in South Africa) or no new training (control group). Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Outreach group | Control group |

|---|---|---|

| Clinics | ||

| No of clinics | 20 | 20 |

| Median total No of adult attendances a quarter | 12 749 | 12 935 |

| Median No of nurses per clinic | 9 | 8.5 |

| Tuberculosis treatment service available | 19 (95) | 20 (100) |

| 24 hour emergency service available | 4 (20) | 2 (10) |

| Median distance (km) from local referral hospital | 7.0 | 5.5 |

| Patients | ||

| No of patients | 1000 | 999 |

| Women | 643 (64.3) | 660 (66.1) |

| Mean age (years) | 44.9 | 44.2 |

| Education: | ||

| Never attended school | 169 (17.0) | 154 (15.4) |

| Attended primary school only | 464 (46.6) | 433 (43.4) |

| Attended secondary school | 363 (36.4) | 410 (41.1) |

| Employment: | ||

| Employed | 155 (15.6) | 209 (21.0) |

| Unemployed without welfare | 569 (57.2) | 557 (56.0) |

| Receiving welfare | 271 (27.2) | 230 (23.1) |

| Smoking history: | ||

| Current | 164 (16.5) | 193 (19.4) |

| Past | 313 (31.4) | 300 (30.1) |

| Never | 519 (52.1) | 504 (50.6) |

| Mean pack year history (smokers only) | 8.9 | 8.3 |

Of the 2000 patients enrolled, 1999 completed the initial interview and one refused consent; 1856 (92.8%) were re-interviewed at four months. Forty eight patients (2.4%) were reported by their families to have died. The groups had similar mortality (intervention, 22/1000; control, 26/999: odds ratio 0.84, 95% confidence interval 0.46 to 1.53).

Training intensity fell short of the targets. Nurses in intervention clinics received a median of two educational outreach visits (range 0-4 visits).

Outcome measures

Tuberculosis

Sputum screening for tuberculosis was higher among patients in the intervention arm but not significantly so (odds ratio 1.22, 0.83 to 1.80; table 2). During the three months of the study period 57 new cases of tuberculosis were diagnosed in intervention clinics compared with 34 in control clinics (odds ratio 1.72, 1.04 to 2.85). The groups had similar numbers of patients diagnosed as having tuberculosis before outreach started (intervention clinics, 108; control clinics, 109).

Table 2.

Trial outcomes

| Outcome | No (%) in outreach group | No (%) in control group | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Intracluster correlation coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sputum screening for tuberculosis | 226/1000 (22.6) | 193/999 (19.3) | 1.22 (0.83 to 1.80) | 0.33 | 0.049 |

| Tuberculosis case detection | 57/892* (6.4) | 34/890* (3.8) | 1.72 (1.04 to 2.85) | 0.04 | 0.007 |

| Prescriptions for inhaled corticosteroids | 137/1000 (13.7) | 77/999 (7.7) | 1.90 (1.14 to 3.18) | 0.006 | 0.019 |

| Prescriptions for antibiotics | 397/1000 (39.7) | 394/999 (39.4) | 1.01 (0.74 to 1.38) | 0.95 | 0.042 |

Denominator limited to all patients who had not been diagnosed as having tuberculosis before educational outreach started.

Obstructive lung disease

Almost twice as many prescriptions were filled out for inhaled corticosteroids in the intervention group than in the control group (13.7%, 137/1000 v 7.7%, 77/999; odds ratio 1.90, 1.14 to 3.18; table 2).

At enrolment 164 patients in the intervention group and 193 patients in the control group reported that they were current smokers. The groups had similar rates for counselling on smoking cessation (68.3%, 112/164 v 65.8%, 127/193 in controls) and smoking cessation for the period between interviews (12.2%, 20/164 v 10.4%, 20/193).

Antibiotic prescriptions

The prescription rates of antibiotics commonly used for respiratory indications did not differ between the groups (odds ratio 1.01, 0.74 to 1.38; table 2).

HIV/AIDS

The groups were similar for voluntary counselling and testing (9.7%, 97/1000 v 7.3%, 73/999 in controls) and for prescriptions for co-trimoxazole among patients with a diagnosis of tuberculosis during the study (7.8%, 13/167 v 7.5%, 11/147 in controls).

Referral

A higher proportion of severely ill patients in the intervention group were referred to a doctor than in the control group (10.5%, 27/257 v 4.8%, 8/166; odds ratio 2.59, 1.06 to 6.19).

Discussion

An educational outreach intervention on syndromic management of respiratory diseases in adults improved the case detection of tuberculosis and the treatment of asthma by nurse practitioners working in typical South African primary care clinics. In this pragmatic trial, the intervention was a “black box” and the relative contributions of the various elements of this multifaceted intervention cannot be distinguished. Although trainers reported using almost all of their visit time for education, they were also middle managers and may, in passing, have provided some managerial support.

Clinic and patient follow-up were exceptionally high, enhancing the internal validity of our trial. The cluster randomised design was accounted for in the analysis. Follow-up was short (only four months); longer term effects could be diluted by the turnover of staff and could decline with time. Emerging studies, however, suggest that evidence based education strategies may trigger long term change in practice.22,23

Appropriateness of care improved across several of the most important conditions: the effect of the intervention on tuberculosis case detection was higher than expected. By contrast, the effect on sputum collection was small. This suggests that the intervention improved clinical selection of cases for sputum sampling.

Inhaled corticosteroid prescribing for asthma also increased, which may be appropriate given that these drugs are known to be underprescribed in South Africa.8 A post hoc analysis also suggested that these prescriptions were clinically appropriate, in that response to β agonists was more often reported by patients who were prescribed inhaled corticosteroids in the intervention group than in their equivalent controls (85%, 117/137 v 73%, 56/77), suggesting that the treated disease was asthma.

The lack of change in antibiotic prescribing may well be appropriate for this severe case mix; only 4.8% of the sample reported symptoms consistent with uncomplicated upper respiratory tract infection, lower than in comparable surveys. In patients with predefined markers of severe disease, referral to physicians was higher in the intervention group.

The number of patients receiving voluntary counselling and testing remained unchanged. Nurses may have seen little point in this practice at a time before antiretroviral treatment was made available in South Africa.24 Repeated central drug shortages prevented the intervention from achieving increases in prescribing of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis. The failure to increase advice on smoking cessation may reflect light smoking at low prevalence (table 1) and thus the low salience of this issue for nurse practitioners dealing with patients with acute severe infectious disease.

What is already known on this topic

In Africa, passive case detection of tuberculosis has not increased detection rates to levels at which the epidemic could be controlled

To date, training is of doubtful effectiveness and has largely been conducted off site, interrupting clinical services, and limiting sustainability and coverage

What this study adds

Educational outreach training in syndromic approaches achieved large improvements in the quality of tuberculosis and asthma care without interrupting services, and within existing staff constraints

Well designed pragmatic randomised controlled trials usefully inform policy decisions

The intervention was carried out in small towns and rural primary care clinics in a poor province with a high rate of tuberculosis and HIV infection. It was delivered by existing staff, and was effective despite the low number of educational contacts, reportedly due to difficulties accommodating visits in clinic schedules.

The Free State and other provinces are adapting educational outreach for HIV/AIDS and implementing it widely. We suggest that in other lower and middle income countries where non-physicians provide primary care, equipping middle managers as outreach trainers is feasible within existing constraints on staff and could improve quality of care.

Our trial was a collaboration between evaluation science and policy development, producing a widely applicable and rigorously evaluated intervention for real world conditions. The challenges facing Africa need more of these partnerships.

Supplementary Material

The guideline and desk blotter are on bmj.com

The guideline and desk blotter are on bmj.com

We thank our PALSA nurse trainers from the Free State Department of Health: Leona Smith, Annette Exley, Sandra Korkie, Tebogo Mothibeli, Francis MacKay, Mariana Thirtle, and Elizabeth Bolofo; fieldwork supervisors Mariëtte van Rensburg and Gloria Gogo from the Centre for Health Systems Research and Development, University of the Free State, for coordination of patient recruitment and interviews; Ineke Buskens for training our nurse trainers; Michael Wyeth and Val Myburgh for layout and illustration of training materials; Chris Seebregts and Clive Seebregts from the Biomedical Informatics Research Division, Medical Research Council, for data collection support, database design, and collation; Chrismara Güttler and Amanda Fourie from the Medical Research Council for data capture; Sonja Botha for data checking and cleaning; and Sonja van der Merwe and Annette Furter from the Free State Department of Health for logistical assistance in setting up pilot sessions and retrieving routine data. For crucial early support and guidance we thank Victor Litlhakanyane and Mosiuoa Shuping from the Free State Department of Health, European Union funded collaborations AfroImplement and PRACTIHC (pragmatic randomised controlled trials in health care) for technical support; Refiloe Matji formerly of the South African National tuberculosis control programme; Robert Scherpbier formerly of Practical Approach to Lung Health at WHO; Salah-Eddine Ottmani of Practical Approach to Lung Health; Louis Niessen from Erasmus University; and Andy Oxman from the Department of Health Services Research, Norwegian directorate for health and social welfare.

Contributors: MZ conceived the project and designed the first protocol. EDB and RGE led development of the guideline. LRF, RGE, AB, ACP, PM, MZ, and RDC contributed to the development and implementation of the intervention. MZ, LRF, MB, and EDB established links with policymakers. LRF, CL, MB, EDB, BPM, MZ, and GJ contributed to the final protocol and design of the questionnaire. DvR, LRF, and BPM oversaw data collection. CL led the analysis with LRF. LRF, CL, MZ, MB, and EDB interpreted the data. LRF, MZ, and BPM prepared the first draft of this paper, and all authors contributed to the final version. MZ and LRF are guarantors.

Funding: This research was completed with the aid of a research grant from the International Development Research Centre, Canada and the Medical Research Council, South Africa. The research was completed independent of the funders. Additional funding was provided by the Free State Department of Health and the University of Cape Town Lung Institute.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Free State. The Free State Department of Health gave permission for the trial.

References

- 1.Frieden TR, Sterling TR, Munsiff S, Watt CJ, Dye C. Tuberculosis. Lancet 2003;362: 887-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma DC. Tuberculosis control goals unlikely to be met by 2005. Lancet 2004;363: 1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corbett EL, Watt CJ, Walker N, Maher D, Williams BG, Raviglione MC, et al. The growing burden of tuberculosis—global trends and interactions with the HIV epidemic. Arch Intern Med 2003;163: 1009-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis control: surveillance, planning, financing. Geneva: WHO, 2004.

- 5.Dye C, Watt CJ, Bleed DM, Williams BG. What is the limit to case detection under the DOTS strategy for tuberculosis control? Tuberculosis 2003;83: 35-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raviglione MC. The TB epidemic from 1992 to 2002. Tuberculosis 2003;83: 4-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stempel DA, Roberts CS, Stanford RH. Treatment patterns in the months prior to and after asthma-related emergency department visit. Chest 2004;126: 75-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mash B, Whittaker D. An audit of asthma care at Khayelitsha Community Health Centre. S Afr Med J 1997;87: 475-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Respiratory care in primary care services—a survey in 9 countries. Geneva: WHO, 2004. (WHO/HTM/TB/2004.333.)

- 10.Louwagie GMC, Bachmann MO, Reid M. Formal clinical primary health care training. Does it make a difference? Curationis 2002;25: 32-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veron LJ, Blanc LJ, Suchi M, Raviglione MC. DOTS expansion: will we reach the 2005 targets? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004;8: 139-46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis D, Evans M, Jadad A, Perrier L, Rath D, Ryan D, et al. The case for knowledge translation: shortening the journey from evidence to effect. BMJ 2003;327: 33-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tunis SR, Stryer DB, Clancy CM. Practical clinical trials: increasing the value of clinical research for decision-making in clinical and health policy. JAMA 2004;291: 425-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartz D, Lellouch J. Explanatory and pragmatic attitudes in therapeutic trials. J Chronic Dis 1967;20: 637-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsey CR, Vale L, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess 2004;8: iii-iv,1-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.South African National Department of Health. South African tuberculosis control programme practical guidelines. Pretoria: South African National Department of Health, 2000. www.doh.gov.za/tb (accessed 13 Jan 2005).

- 17.South African National Department of Health. Standard treatment guidelines and essential drugs list for South Africa, 2nd ed. Pretoria: South African National Department of Health, 1998.

- 18.South African National Department of Health. 2002 Tuberculosis case finding and treatment outcomes. National tuberculosis control programme. Pretoria, South Africa: South African National Department of Health, 2003.

- 19.Makubalo L, Netshidzivhani P, Mahlasela L, du Plessis R. National HIV and syphilis antenatal sero-prevalence survey in South Africa 2003. Health Systems Research, Research Coordination and Epidemiology Directorate, Pretoria: South African National Department of Health, 2003. www.doh.gov.za/docs/index.html (accessed 20 Jan 2005).

- 20.Guillemin F, Bombadier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46: 1417-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams G, Gulliford MC, Ukoumunne OC, Eldridge S, Chinn S, Campbell MJ. Patterns of intra-cluster correlation from primary care research to inform study design and analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2004;57: 785-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanci LA, Coffey CM, Veit FC, Carr-Gregg M, Patton GC, Days N, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of an educational intervention for general practitioners in adolescent health care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2000;320: 224-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morgenstern LB, Bartholomew LK, Grotta JC, Staub L, King M, Chan W. Sustained benefit of a community and professional intervention to increase acute stroke therapy. Arch Intern Med 2003;163: 2198-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.South African National Department of Health. Operational plan for comprehensive HIV and AIDS care, management and treatment for South Africa. Pretoria: South African National Department of Health, 2003.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.