Abstract

The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of resistance exercise programs on older adults’ physical and psychological health indicators. Twelve randomized controlled trials published in Korean between January 2000 and July 2024 were included in this meta-analysis. The subjects in the selected studies were all aged 65 and over. The intervention group performed resistance exercise, and the control group did not engage in structured exercise programs. The resistance exercise programs were implemented for an average of 8–12 weeks, 2–3 sessions per week, with each session lasting 40–70 min. Effect sizes were calculated using standardized mean differences, and statistical analysis was conducted using R software. The results revealed that resistance exercise significantly improved various fall-related physical outcomes, including grip strength, flexibility, static and dynamic balance, lower body strength, and coordination. Also, fall efficacy was significantly increased. However, there was no statistically significant change in skeletal muscle mass and body fat percentage. These findings suggest that resistance exercise is an effective intervention for improving physical function and psychological stability in older adults.

Keywords: Meta-analysis, Resistance exercise, Older adults, Muscle strength, Fall prevention, Fall efficacy

INTRODUCTION

South Korea is undergoing rapid demographic aging, with older adults accounting for approximately 17.4% of the total population in 2024, around 9.5 million people, according to projections by Statistics Korea. Life expectancy is also expected to increase steadily, reaching 88.4 years for women and 83.0 years for men by 2030. This demographic shift presents significant challenges for public health, as age-related conditions become more prevalent and long-term care needs expand. In 2023, data from the National Health Insurance Service indicated that older adults accounted for 43.1% of total healthcare expenditures, highlighting the growing financial burden on the national healthcare system. Given this context, promoting physical function and preventing disability in older adults has become an urgent public health priority. As the proportion of older adults increases, the need for targeted interventions to support their health and independence becomes more urgent. This need arises from the physiological changes associated with aging, such as progressive declines in muscle strength, endurance, flexibility, and cardiopulmonary function. These changes contribute to chronic conditions like sarcopenia, osteoporosis, and cardiovascular disease, ultimately reducing functional capacity and compromising independent living (Trombetti et al., 2016). Sarcopenia, in particular, leads to reduced physical function and quality of life, while increasing the risk of falls and fractures, thereby imposing substantial healthcare costs (Lopez et al., 2018). Additionally, sarcopenia is associated with mental health issues, including depression, further exacerbating its societal and economic impact (Singh et al., 2005).

In recognition of these challenges, the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) emphasized the critical role of exercise for older adults in 1998 (American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand, 1998). Since then, various exercise interventions, including aerobic exercise, combined aerobic and anaerobic exercise, and flexibility exercises such as yoga, have been studied both domestically and internationally (Baker et al., 2010; Harber et al., 2009). However, despite the ACSM’s 2009 recommendation highlighting the benefits of high-intensity resistance training for older adults, research focusing exclusively on resistance exercise interventions remains limited.

Participation in resistance exercise among older adults is often hindered by perceptions of difficulty, risk, or monotony compared to other lifestyle activities such as dance sports or aquatic exercise (Burton et al., 2017; Hurst et al., 2023). Nevertheless, recent studies have demonstrated that resistance training significantly improves muscular strength, endurance, balance, and functional ability, thereby reducing the risk of falls and enhancing independence in daily activities (Cadore et al., 2014; Molino-Lova et al., 2013). Furthermore, increases in muscle mass resulting from resistance exercise promote the secretion of myokines, cytokines produced by muscle cells, which have been shown to enhance cognitive function (Sleiman et al., 2016). Resistance exercise has also been associated with improvements in psychological outcomes, including reductions in depression and anxiety symptoms (Bushman and Goddard, 2020; Westcott, 2015).

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to conduct a meta-analysis of Korean studies examining the effects of resistance exercise in adults aged 65 years and older, with a particular interest in fall-related physical functions (e.g., balance, lower limb strength, coordination) as well as psychological indicators such as fall self-efficacy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study participants

To investigate the effects of resistance exercise interventions among older adults, this study searched for theses and journal articles published in Korea from January 2000 to July 2024, written in Korean. The search was conducted using major academic databases, including the Research Information Sharing Service, Korean Information Service System, DBpia, and the National Assembly Library. Key terms such as “older adults,” “intervention,” “resistance,” and “exercise” were combined in various ways to perform the search.

Experimental design

This study was conducted following the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses guidelines, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The inclusion criteria were based on the persistent compute object framework (Cooper et al., 2018) as follows: participants were older adults aged 65 years or older without major health issues; interventions consisted of resistance exercise programs; comparisons involved control groups that maintained their usual daily activities without intervention; outcomes were defined as improvements in physical and psychological factors following exercise interventions; and study design was restricted to randomized controlled trials. An initial search yielded 198 articles. After removing 24 duplicates and 40 irrelevant studies, the remaining articles were manually screened by reviewing titles and abstracts. The exclusion criteria at this stage encompassed studies targeting older adults with chronic conditions such as obesity, diabetes, or hypertension; studies combining pharmacological interventions; and studies involving combined exercise interventions other than resistance training. Following full-text review, articles were further excluded if they lacked pre- and postintervention assessments, did not include a control group, or did not provide sufficient statistical data to calculate effect sizes. Finally, 12 articles written in Korean were selected for this meta-analysis.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study selection process.

Data processing and analysis methods

All selected studies were coded based on first author, year of publication, sample sizes of the experimental and control groups, dependent variables, and the content of the exercise intervention programs. These characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The quality of the selected studies was assessed using the Korean version of the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias 2 tool, given that all 12 included studies were randomized controlled trials. The risk of bias was rated as low risk (L) across six domains: (a) generation of the randomization sequence, (b) concealment of the allocation sequence, (c) blinding of participants and researchers, (d) blinding of outcome assessors, (e) incomplete outcome data, and (f) selective reporting of outcomes. Two independent researchers participated in the quality assessment process to ensure interrater reliability (Higgins et al., 2011). Homogeneity and heterogeneity across studies were assessed using Stata 17 (StataCorp LLC, USA), and meta-analyses were conducted using the “meta” and “metafor” packages in R ver. 4.1.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria). The effect size was calculated as the standardized mean difference using the following formula:

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study | No. | Sex | Exercise Intervention | Dependent variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | Control | Program | Duration (wk) | Frequency per week) | Time (min) | |||

| Hyeong-Su Lee (2007) | 15 | 15 | F | Resistance band exercise+ proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation | 8 | 3 | 50 | Agility, endurance, flexibility, balance, body composition (weight, BMI, body fat %, lean body mass), strength |

| Geon Kim (2008) | 15 | 15 | M & F | Resistance band exercise | 9 | 3 | 50 | Isometric strength, balance |

| Hanju Lee (2009) | 12 | 12 | F | Resistance exercise | 8 | 3 | 50 | Body composition, balance |

| Hye-Sang Park (2009) | 13 | 9 | F | Resistance band exercise | 8 | 3 | 50 | Lower limb muscular endurance, balance, flexibility, gait ability |

| Jun-Myoung Cho (2012) | 10 | 10 | F | Resistance band exercise | 12 | 3 | 60 | Body composition (weight, lean body mass), immune function |

| Seol-Jung Kang (2014) | 7 | 7 | F | Walking+resistance band exercise | 12 | 3 | 30 | Sarcopenia indicators, inflammatory cytokines, insulin resistance |

| Bong-Gil Choi (2016) | 12 | 12 | F | Resistance exercise including blood flow restriction | 12 | 3 | - | Body composition (height, weight, muscle mass, body fat mass, body fat %), isokinetic strength (Cybex 770) |

| Hyang-Beum Lee (2018) | 11 | 11 | F | Resistance band exercise | 12 | 3 | 50–60 | Functional fitness (muscle function, balance, flexibility, cardiopulmonary endurance, coordination), bone mineral density |

| Seong-Jun Lim (2019) | 15 | 15 | F | High-intensity resistance training | 8 | 3 | 60 | Fall-related physical performance (grip strength, lower limb strength, flexibility, cardiopulmonary endurance, balance, coordination), HOMA-IR, HbA1c |

| Jeongok Cho (2020) | 21 | 21 | F | Resistance band exercise | 8 | 2 | 40 | Physical function (balance, gait speed, five chair stands), grip strength, flexibility, activities of daily living (K-MBI), self-efficacy (FES-K), quality of life |

| Kyu-Ho Lee (2023) | 15 | 15 | F | Resistance band exercise | 12 | 3 | 60 | Body composition, muscle function, cognitive function, blood tau protein concentration |

| Ga-Hyun Kim (2024) | 15 | 15 | F | Bodyweight resistance+ resistance band exercise | 12 | 3 | 60 | Bone metabolism, fall self-efficacy |

BMI, body mass index; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; K-MBI, modified Barthel index; FES-K, family environment scale-Korean version.

Interpretation of effect sizes followed Cohen criteria (Cohen, 1992), where an effect size between 0.2 and 0.5 indicates a small effect, between 0.5 and 0.8 a medium effect, and above 0.8 a large effect. Homogeneity was further examined using the weighted average method proposed by Hedges (1992), and Cochran Q-test was conducted to determine homogeneity. A fixed-effect model was applied when homogeneity was confirmed; otherwise, a random-effects model was used. Publication bias was assessed using Egger linear regression asymmetry test for meta-analyses involving three or more studies. All statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

RESULTS

Effect size of resistance training on body composition

Skeletal muscle mass

A fixed-effects model was used due to moderate heterogeneity (I2=43%). As shown in Fig. 2, the findings suggest limited and uncertain benefits of resistance training on skeletal muscle mass in older adults.

Fig. 2.

Effect size of resistance training on skeletal muscle mass. SD, standard deviation; SMD, standardized mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

Body fat

The effect of resistance exercise on body fat percentage in older adults is presented in Fig. 3. A fixed-effects model was employed due to the absence of heterogeneity across studies. The findings were largely consistent, with most effect sizes clustering near the null. Overall, the pooled effect was small and not statistically significant.

Fig. 3.

Effect size of resistance training on body fat percentage. SD, standard deviation; SMD, standardized mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

Effect size of resistance exercise on fall-related physical fitness resistance training on body composition

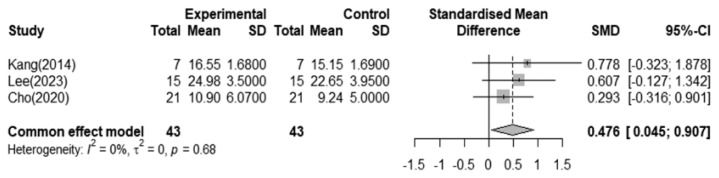

Handgrip strength

The impact of resistance training on handgrip strength in older adults is presented in Fig. 4. A fixed-effects model was selected due to the absence of heterogeneity. The results consistently indicated a statistically significant improvement in handgrip strength, reflecting the positive effect of resistance training on muscular strength in older adults.

Fig. 4.

Effect size of resistance training on handgrip strength. SD, standard deviation; SMD, standardized mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

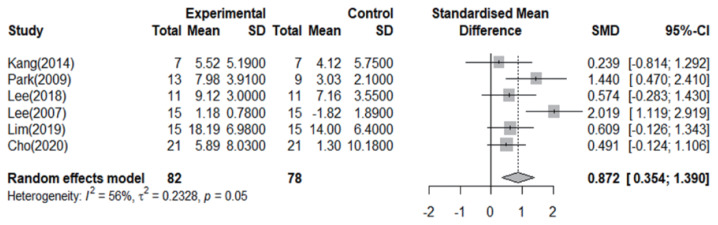

Flexibility

The effect of resistance training on flexibility in older adults is illustrated in Fig. 5. Due to moderate heterogeneity across studies (I2=56%), a random-effects model was applied. The pooled results indicated a statistically significant and relatively large improvement in flexibility following resistance training.

Fig. 5.

Effect size of resistance training on flexibility. SD, standard deviation; SMD, standardized mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

Static and dynamic balance

The effect size of resistance training on balance in older adults are shown in Figs. 6 and 7. For static balance (eyes-open standing posture), moderate heterogeneity was observed (I2=61%), and a random-effects model was applied. The overall findings indicated a statistically significant and substantial improvement in static balance following resistance exercise. In contrast, the results for dynamic balance (chair sit-to-walk tasks) showed a large and statistically significant improvement, with low heterogeneity across studies (I2=19%).

Fig. 6.

Effect size of resistance training on static balance. SD, standard deviation; SMD, standardized mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 7.

Effect size of resistance training on dynamic balance. SD, standard deviation; SMD, standardized mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

Lower limb strength

Fig. 8 shows the effect of resistance training on lower limb strength in older adults. A random-effects model was applied due to moderate heterogeneity (I2=49%). Overall, resistance training led to a significant increase in lower limb strength.

Fig. 8.

Effect size of resistance training on lower limb strength. SD, standard deviation; SMD, standardized mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

Coordination

Fig. 9 shows the effect of resistance training on coordination in older adults. A fixed-effects model was applied, as heterogeneity among studies was low (I2=0%). The findings across studies were consistent, supporting the effectiveness of resistance training in enhancing coordination ability.

Fig. 9.

Effect size of resistance training on coordination. SD, standard deviation; SMD, standardized mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

Effect size of resistance exercise on fall self-efficacy

Fig. 10 shows the effect of resistance training on fall self-efficacy in older adults. A fixed-effects model was applied due to the absence of heterogeneity (I2=0%), indicating a high level of consistency among the included studies. Overall, resistance training had a large and statistically significant positive effect, suggesting enhanced confidence in avoiding falls.

Fig. 10.

Effect size of resistance training on fall self-efficacy. SD, standard deviation; SMD, standardized mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

This meta-analysis provides evidence that resistance exercise contributes to improved fall-related physical performance, such as lower limb strength, balance, flexibility, and coordination, as well as psychological confidence, such as fall self-efficacy, in older adults. Significant improvements were observed in lower limb strength, with a large effect size. This aligns with previous research highlighting the strength-enhancing effects of resistance training in older adults (Borde et al., 2015; Jiang et al., 2025) and its importance in maintaining walking ability and functional independence (Fraga-Germade et al., 2024; Sherrington et al., 2011). In addition, both static and dynamic balance were significantly improved (Westcott, 2015), underscoring the role of resistance exercise in enhancing gait stability and preventing falls (Wang et al., 2024).

Improved flexibility and coordination were also noted, contributing to greater joint mobility, smoother postural transitions, and better control in daily movements. In terms of fall self-efficacy, resistance training demonstrated a large and consistent positive effect. This is particularly meaningful, as fear of falling can lead to reduced physical activity, thereby accelerating physical decline and increasing fall risk. Resistance training may thus help to disrupt this cycle and promote active aging (Zhao et al., 2019). These findings are especially relevant in the context of aging-related physical decline. A substantial portion of the reduction in physical fitness and overall functional capacity with aging has been attributed to musculoskeletal deterioration, including losses in muscle mass, strength, and bone density (Papa et al., 2017). Such changes can result in postural imbalances, which are known to contribute to musculoskeletal disorders and increase the risk of falls. Poor posture and bilateral lower limb imbalances impair balance maintenance during postural transitions (Cheng et al., 2001). As such, exercise programs that incorporate postural stability, flexibility, lower limb strength, and reaction time are essential for effective fall prevention (Pavol et al., 2001). The improvements observed in this study suggest that resistance training can effectively target these risk factors and provide broad physical and psychological benefits for older adults.

The degree of between-study heterogeneity varied across the variables analyzed. Fall self-efficacy demonstrated highly consistent results across studies, whereas outcomes such as flexibility and static balance exhibited moderate heterogeneity. These differences may arise from variations in intervention types, intensity, duration, measurement tools, and participant characteristics. This suggests that although the overall direction of the effects was positive, further standardization in resistance training protocols and assessment methods is necessary to enhance the comparability and reliability of future studies.

Resistance training did not yield statistically significant effects on skeletal muscle mass or body fat percentage in older adults. This may be attributed to the limited intensity and duration of interventions, as well as physiological characteristics associated with aging. While studies in younger adults report measurable increases in muscle mass after 8 to 12 weeks of training (Tieland et al., 2018), older adults may require at least 16 weeks of progressive overload to achieve similar results due to age-related declines in protein synthesis (Kim and Kang, 2020; Radaelli et al., 2025). In addition, resistance training in older populations often involves safety-related intensity limitations, making it difficult to apply sufficient overload to induce muscle hypertrophy. Furthermore, improvements in muscular strength and balance without corresponding changes in muscle mass are physiologically consistent with early-phase neural adaptations, such as increased motor unit recruitment and enhanced neuromuscular coordination (Del Vecchio et al., 2019). These factors collectively may explain why significant gains in physical function were observed in this meta-analysis, despite the lack of statistically significant changes in body composition.

One notable strength of this study is its integrative and standardized approach to analyzing fall prevention. Unlike prior studies that focused on isolated outcomes, this meta-analysis simultaneously assessed a broad range of physical and psychological variables. These outcome variables were selected in alignment with the National Physical Fitness 100, a standardized fitness assessment for older adults in Korea. By grounding its analysis in these criteria, the study enhances both the methodological rigor and practical relevance of its findings for fall prevention. While most exercise programs for older adults have traditionally emphasized aerobic or flexibility-based activities such as swimming or yoga, this study provides compelling evidence for the essential inclusion of resistance training in future elderly-specific exercise interventions and public health policy design. However, the relatively small number of included studies and limited sample sizes suggest the need for further research with broader populations and longer intervention periods.

In conclusion, resistance training should be considered a core component of long-term exercise programs for older adults. By improving not only fall-related physical functions but also psychological confidence, resistance exercise plays a crucial role in maintaining independence, preventing falls, and supporting healthy aging. Based on the findings of this meta-analysis, resistance training should be recognized as a core component of evidence-based exercise prescriptions and systematically incorporated into public health strategies for aging populations.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors received no financial support for this article.

REFERENCES

- American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:992–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LD, Frank LL, Foster-Schubert K, Green PS, Wilkinson CW, McTiernan A, Plymate SR, Fishel MA, Watson GS, Cholerton BA, Duncan GE, Mehta PD, Craft S. Effects of aerobic exercise on mild cognitive impairment: a controlled trial. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:71–79. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borde R, Hortobágyi T, Granacher U. Dose-response relationships of resistance training in healthy old adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2015;45:1693–1720. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0385-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton E, Hill AM, Pettigrew S, Lewin G, Bainbridge L, Farrier K, Airey P, Hill KD. Why do seniors leave resistance training programs? Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:585–592. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S128324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushman B, Goddard S. Keep on: staying active to promote well-being during the golden years. ACSM Health Fit J. 2020;24:46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cadore EL, Pinto RS, Bottaro M, Izquierdo M. Strength and endurance training prescription in healthy and frail elderly. Aging Dis. 2014;5:183–195. doi: 10.14336/AD.2014.0500183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng PT, Wu SH, Liaw MY, Wong AM, Tang FT. Symmetrical body-weight distribution training in stroke patients and its effect on fall prevention. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:1650–1654. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.26256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C, Booth A, Varley-Campbell J, Britten N, Garside R. Defining the process to literature searching in systematic reviews: a literature review of guidance and supporting studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:85. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0545-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Vecchio A, Casolo A, Negro F, Scorcelletti M, Bazzucchi I, Enoka R, Felici F, Farina D. The increase in muscle force after 4 weeks of strength training is mediated by adaptations in motor unit recruitment and rate coding. J Physiol. 2019;597:1873–1887. doi: 10.1113/JP277250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraga-Germade E, Carballeira E, Iglesias-Soler E. Effect of resistance training programs with equated power on older adults’ functionality and strength: a randomized controlled trial. J Strength Cond Res. 2024;38:153–163. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000004588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harber MP, Konopka AR, Douglass MD, Minchev K, Kaminsky LA, Trappe TA, Trappe S. Aerobic exercise training improves whole muscle and single myofiber size and function in older women. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297:R1452–R1459. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00354.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV. Meta-analysis. J Educ Behav Stat. 1992;17:279–296. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA, Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst C, Dismore L, Granic A, Tullo E, Noble JM, Hillman SJ, Witham MD, Sayer AA, Dodds RM, Robinson SM. Attitudes and barriers to resistance exercise training for older adults living with multiple long-term conditions, frailty, and a recent deterioration in health: qualitative findings from the Lifestyle in Later Life - Older People’s Medicine (LiLL-OPM) study. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23:772. doi: 10.1186/s12877-023-04461-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang G, Tan X, Zou J, Wu X. A 24-week combined resistance and balance training program improves physical function in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. J Strength Cond Res. 2025;39:e62–e69. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000004941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KM, Kang HJ. Effects of resistance exercise on muscle mass, strength, and physical performances in elderly with diagnosed sarcopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Exerc Sci. 2020;29:109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez P, Pinto RS, Radaelli R, Rech A, Grazioli R, Izquierdo M, Cadore EL. Benefits of resistance training in physically frail elderly: a systematic review. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30:889–899. doi: 10.1007/s40520-017-0863-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molino-Lova R, Pasquini G, Vannetti F, Paperini A, Forconi T, Polcaro P, Zipoli R, Cecchi F, Macchi C. Effects of a structured physical activity intervention on measures of physical performance in frail elderly patients after cardiac rehabilitation: a pilot study with 1-year follow-up. Intern Emerg Med. 2013;8:581–589. doi: 10.1007/s11739-011-0654-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa EV, Dong X, Hassan M. Skeletal muscle function deficits in the elderly: current perspectives on resistance training. J Nat Sci. 2017;3:e272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavol MJ, Owings TM, Foley KT, Grabiner MD. Mechanisms leading to a fall from an induced trip in healthy older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M428–M437. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.7.m428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radaelli R, Rech A, Molinari T, Markarian AM, Petropoulou M, Granacher U, Hortobágyi T, Lopez P. Effects of resistance training volume on physical function, lean body mass and lower-body muscle hypertrophy and strength in older adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of 151 randomised trials. Sports Med. 2025;55:167–192. doi: 10.1007/s40279-024-02123-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrington C, Tiedemann A, Fairhall N, Close JC, Lord SR. Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: an updated meta-analysis and best practice recommendations. N S W Public Health Bull. 2011;22:78–83. doi: 10.1071/NB10056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh NA, Stavrinos TM, Scarbek Y, Galambos G, Liber C, Fiatarone Singh MA. A randomized controlled trial of high versus low intensity weight training versus general practitioner care for clinical depression in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:768–776. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.6.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleiman SF, Henry J, Al-Haddad R, El Hayek L, Abou Haidar E, Stringer T, Ulja D, Karuppagounder SS, Holson EB, Ratan RR, Ninan I, Chao MV. Exercise promotes the expression of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) through the action of the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate. Elife. 2016;5:e15092. doi: 10.7554/eLife.15092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tieland M, Trouwborst I, Clark BC. Skeletal muscle performance and ageing. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2018;9:3–19. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trombetti A, Reid KF, Hars M, Herrmann FR, Pasha E, Phillips EM, Fielding RA. Age-associated declines in muscle mass, strength, power, and physical performance: impact on fear of falling and quality of life. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27:463–471. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3236-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang C, Wang B, Zhang D, Song X. Comparative effects of cognitive and instability resistance training versus instability resistance training on balance and cognition in elderly women. Sci Rep. 2024;14:26045. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-77536-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westcott WL. Build muscle, improve health: benefits associated with resistance exercise. ACSM Health Fit J. 2015;19:22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R, Bu W, Chen X. The efficacy and safety of exercise for prevention of fall-related injuries in older people with different health conditions, and differing intervention protocols: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:341. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1359-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]