Abstract

The MEK inhibitor selumetinib induces objective responses and provides clinical benefit in children with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and inoperable plexiform neurofibromas (PNs). To evaluate whether similar outcomes were possible in adult patients, in whom PN growth is generally slower than in pediatric patients, we conducted an open-label phase 2 study of selumetinib in adults with NF1 PNs. The study was designed to evaluate objective response rate (primary objective), tumor volumetric responses, patient reported outcomes, and pharmacodynamic effects in PN biopsies. The objective response rate was 63.6% (21/33 participants). Median maximal PN volume decrease was 23.6% (range: −48.1%-5.5%). No disease progression relative to baseline PN volumes occurred prior to data cut-off with a median of 28 cycles completed (range: 1–78, 28 days/cycle). Participants experienced decreased tumor pain intensity and pain interference. Adverse events (AEs) were similar to those of the pediatric trial; acneiform rash was the most prevalent AE. Phosphorylation ratios of ERK1/2 decreased significantly (ERK1 median change: −64.6% [range: −99.5%-104.3%], ERK2 median change: − 57.7% [range: −99.9%-84.6%]) in paired PN biopsies (P≤0.001 for both isoforms) without compensatory phosphorylation of AKT1/2/3. The sustained PN volume decreases, associated improvement in pain, and manageable AE profile indicate selumetinib provides benefit to adults with NF1 and inoperable PNs. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02407405.

Keywords: Neurofibromatosis, NF1, pharmacodynamics, MEK signaling

Introduction

Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1) is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder that can manifest in benign and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST). Nearly half of patients develop histologically benign PNs which are at risk to transform into MPNST1–4. PN location and involvement of multiple nerve branches often cause substantial morbidity for patients and usually preclude complete surgical resection5,6. Morbidity can result from locality and can include airway impairment, pain, disfigurement, bowel/bladder dysfunction, motor impairment, and/or visual comorbidities7,8.

Predisposition for PNs derives from germline mutations in the NF1 gene that occur in approximately 1 in 3,500 births in the United States9. NF1 encodes the tumor suppressor protein neurofibromin, which mediates Ras signaling activity by acting as a RAS GTPase10. Neurofibromin mutations result in hyperactive signaling via the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway (Extended Data Figure 1)11,12. More than 20 clinical trials for inoperable NF1 PNs have been completed, including studies of Ras pathway-targeting agents13. Many trials were focused on children with NF1 PNs, as the most rapid PN growth occurs in childhood and PNs show minimal or no growth in adults14. The majority of these trials did not demonstrate partial responses (PRs), defined as ≥20% PN volume decrease using the Response Evaluation in Neurofibromatosis and Schwannomatosis (REiNS) criteria15.

Selumetinib (ARRY-142886, NSC 741078), an allosteric kinase inhibitor specifically targeting MEK1/2, has demonstrated preclinical efficacy against a wide range of cancers16. Its binding to MEK1/2 inhibits ERK1/2 phosphorylation and subsequent activation of processes involved in cell proliferation, survival, differentiation, and apoptosis17,18. An NCI-sponsored phase 1/2 trial of selumetinib (SPRINT, NCT01362803) was the first to demonstrate PRs in a majority of participating children with inoperable NF1 PNs (phase 1: 71%, 17/24 participants; phase 2: 68%, 34/50 participants)19. In the phase 1 portion, responses were observed at all dose levels tested and the recommended phase 2 dose was 60% of the recommended dose for adults with solid cancers19. The phase 2 study confirmed the high response rate and demonstrated improvements in patient-reported and functional outcome measures19,20. In April 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved selumetinib to treat PNs in children 2–18 years old based on results from this trial21. Selumetinib is also approved in other countries including the European Union, China, Japan, and Canada for the treatment of PNs in children. Given PN shrinkage in the majority of children, we hypothesized that selumetinib would also result in objective responses and potentially clinical benefit in adults with inoperable PNs.

We thus developed an open-label phase 2 study of selumetinib for adult participants with NF1 and inoperable PNs that were growing or symptomatic (NCT02407405). The primary objective was to determine the confirmed objective response rate (ORR) according to REiNS criteria15. Secondary objectives included evaluations of volumetric responses, assessments of AEs, and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) similar to the SPRINT trial. Multiple studies have reported compensatory crosstalk between the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways in cell lines in response to inhibition of one of these pathways (i.e., AKT activation in response to MEK inhibition)22–24. While the SPRINT trial demonstrated the clinical efficacy of selumetinib, biopsies were not collected in children during that study. This adult trial included mandatory paired PN biopsies for evaluating molecular pharmacodynamic effects and thereby gain a mechanistic understanding of selumetinib in this disease setting.

Results

Participant Characteristics and Objectives

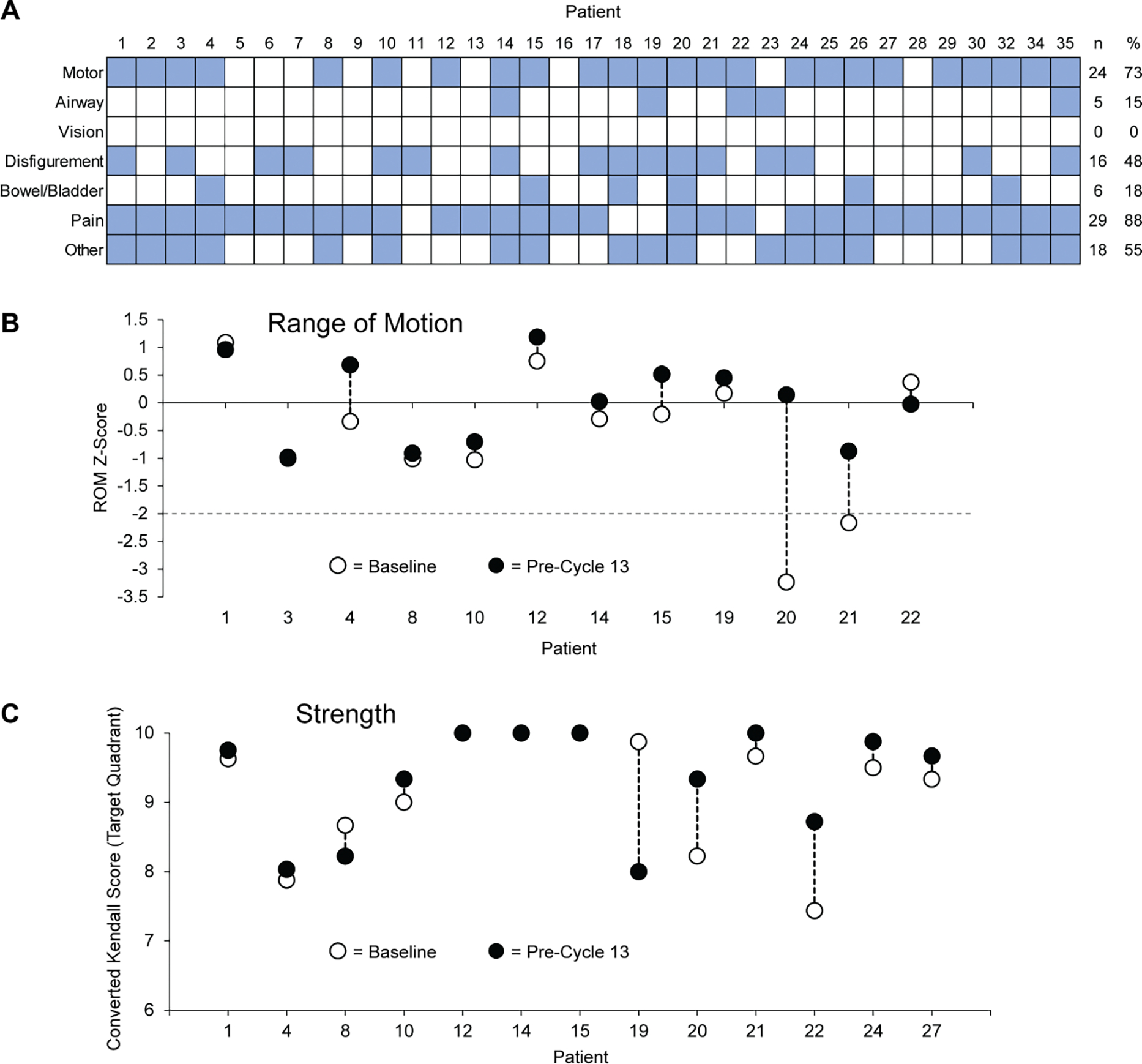

Participants with NF1 based on genetic testing or clinical NIH consensus criteria and who had at least one PN measurable by volumetric MRI were eligible; they were required to be ≥18 years of age, have adequate organ and bone marrow function, and have an ECOG performance status of ≤2. PNs were required to be inoperable, symptomatic, or growing with the potential to cause morbidity. Ability to understand and willingness to sign a written informed consent document were also required. A total of 37 participants were screened, of whom 33 were enrolled from 4 January 2016 through 8 November 2021 (Figure 1); data collected prior to data cut-off (DCO) on April 30, 2022 are presented. Characteristics of the 33 enrolled participants are reported in Table 1. Median age at enrollment was 35.6 years (range: 18.3–60.2 years) and 33% (11/33) of participants were female. The median target neurofibroma volume at baseline was 1170 mL (range: 27–8282 mL). Four participants had progressive disease prior to enrollment, other participants were eligible based on symptomatic tumors. Paired biopsies were collected from 24 participants for pharmacodynamic analyses (Figure 1). A median of 3 PN-related morbidities (range: 1–5) were present per participant (Table 1, Extended Data Figure 2) and are discussed below.

Figure 1:

CONSORT-style flow diagram. Left column: Four participants were screened but did not enroll in the study; reasons for not enrolling included lack of growing tumor or PN-related co-morbidity (n=2), baseline ophthalmologic condition (n=1), and clinical judgement of the investigator (n=1). All 33 participants who were eligible received at least one dose of selumetinib and were considered evaluable for toxicity. Two participants came off study before the first re-staging scan prior to cycle 5. All 33 evaluable participants completed patient-reported outcome measures at baseline, although only 31 completed them prior to cycle 5, 30 prior to cycle 9, and 28 prior to cycle 13. These numbers reflect that some participants came off study between each PRO assessment. Of the 24 participants from whom biopsy pairs were collected, multiple biopsy pairs were collected from several participants (i.e., a biopsy pair each from a target and non-target lesion) and other participants only had biopsies collected from non-target lesions. Right column: A total of 26 paired core biopsies were collected. All available biopsy tissue from some participants was used for pMEK/pERK analysis; RNA-Seq and kinome analyses could only be performed on remaining biopsy cores and therefore had fewer paired biopsies analyzed.

Table 1:

Patient enrollment characteristics

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Patients enrolled (n)* | 33 |

|

| |

| Median age at enrollment - years (range) | 35.6 (18.3 – 60.2) |

|

| |

| Sex (n)* | |

| Male | 22 |

| Female | 11 |

|

| |

| Race (n) | |

| White | 25 |

| Black or African-American | 5 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 |

| Asian | 1 |

| Unknown | 1 |

|

| |

| Ethnicity (n) | |

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 30 |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 3 |

|

| |

| Median volume of target neurofibroma at trial entry - mL (range) | 1170 (27 – 8282) |

|

| |

| Progression status of target neurofibroma at trial entry (n) | |

| Progressive | 4 |

| Nonprogressive | 20 |

| Unknown | 9 |

|

| |

| Location of the target neurofibroma (n) | |

| Trunk and limbs | 7 |

| Neck, trunk, and limbs | 6 |

| Limbs only | 6 |

| Neck and limbs | 5 |

| Trunk only | 3 |

| Neck only | 3 |

| Head and neck | 2 |

| Neck and trunk | 1 |

|

| |

| Neurofibroma-related comorbidities per participant - median (range) | 3 (1 – 5) |

|

| |

| Type of neurofibroma-related complication - number (%) | |

| Pain | 29 (88) |

| Motor dysfunction | 24 (73) |

| Disfigurement | 16 (48) |

| Bowel or bladder | 6 (18) |

| Airway | 5 (15) |

| Vision | 0 (0) |

| Other | 18 (55) |

The study was not designed to compare responses based on participants’ sex.

The primary objective of this study was to determine the objective response rate to selumetinib in adult participants with NF1 and PNs. Secondary objectives included analysis of tumor volumetric responses, progression-free survival, steady-state pharmacokinetics, and patient-reported and functional outcome measures. Exploratory objectives included pharmacodynamic analysis of MEK, ERK, and AKT phosphorylation; tumor kinome; and tumor transcriptome in paired pre- and on-treatment biopsies.

Overall Response Rate

At least 1 re-staging MRI was performed for 31/33 participants evaluable for volumetric response. The confirmed ORR was 63.6% (21/33 participants; 95% exact binomial CI 54.5%-86.7%; Figure 2A). Of the 21 participants who achieved confirmed partial responses, 17 achieved sustained PR (sPR, PR measured on 3 consecutive scans); three additional participants achieved unconfirmed PRs (uPR) and are not included as responders in the overall response rate determination. Fourteen participants had a PR that lasted ≥12 cycles (approximately 1 year). No participants experienced progressive disease (PD) while on study, although 1 participant had target lesion growth of 17.6% above baseline at re-staging prior to cycle 13 and underwent resection of the target lesion before the subsequent scan (Extended Data Figure 3, orange triangles). This participant’s tumor was deemed inoperable due to risk/benefit ratio at baseline; tumor growth during the study shifted that ratio such that surgery was deemed more favorable. Confirmed response rates for participants whose target lesions were classified as typical, nodular, or solitary nodular PNs were 61.5% (16/26 participants, 95% binomial CI: 40.6%-79.8%), 100% (2/2 participants, 95% binomial CI: 15.8%-100%), and 60% (3/5 participants, 95% binomial CI: 14.7%-94.7%), respectively; counts were too low to allow for comparisons between groups.

Figure 2:

Best responses, numbers of cycles completed, and PFS. (A) Target lesion volume change from baseline is shown at time of best response. The dashed line indicates the threshold for partial response. Bar colors indicate disease progression status at baseline for each participant. (B) The numbers of cycles completed by each participant at DCO are shown. Arrows indicate that a participant remains on study at DCO. White circles denote times of initial partial response, orange circles denote times of best response, and split white/orange circles denote instances where initial partial response and best response occurred simultaneously. Bars are colored based on selumetinib dose as indicated. Participants 1 and 2 initiated selumetinib treatment at 75 mg BID and were reduced to 50 mg BID after developing grade 3 acneiform rashes during cycle 1; the protocol was amended such that 50 mg BID was the initial dose for all subsequent participants. (C) PFS was calculated per protocol based on the proportion of participants whose tumor volumes increased at least 20% above baseline values (black line); PFS after 60 cycles (4.6 years) was 100%. The previously published pediatric trial of selumetinib for the treatment of PNs (SPRINT) defined progression as tumor growth of at least 20% above tumor volume at the time of best response. Using that definition of progression, PFS after 60 cycles was 72.9% (2-sided 95% CI 52.7–100%) in this study (red line). The two definitions of PFS led to differing numbers of participants at risk at several time points; the numbers of participants at risk are indicated below the x-axis and color-coded according to their respective curves.

Tumor Volumetric Responses

Among all participants, the median target lesion volume change from baseline at best response was −23.6% (range: −48.1%-5.5%). Among confirmed responders, median time to first response was 12 cycles (range 4–54 cycles), and median time to best response was 20 cycles (range: 12–72 cycles). The confirmed response rate among participants with disease in the trunk was 57.9% (11/19; 95% binomial CI: 33.5%-79.7%), and that among participants with disease outside of the trunk was 71.4% (10/14; 95% binomial CI: 41.9%-91.6%). The confirmed response rate among participants with baseline status of stable disease (SD) was 60% (12/20; 95% binomial CI: 36.1%-80.9%), while that rate among participants with baseline status of PD was 75% (3/4; 95% binomial CI: 19.4%-99.4%). The small sample sizes of these groups preclude robust statistical analysis of the differing response rates. The confirmed response rate among participants with unknown baseline progression status was 66.7% (6/9; 95% binomial CI: 29.9%-92.5%). At DCO, 19/33 participants remain on study with a median of 38 cycles completed (range: 6–78 cycles, Figure 2, Extended Data Figure 3). Of these 19 participants, 7 maintain SD at DCO, 1 has uPR, 3 have confirmed PR (cPR, PR on 2 consecutive scans), and 8 have sPRs. Among those with sPRs at DCO, 4/8 participants (participants 1, 3, 14, and 30) achieved their best volumetric response at their most recent scan (Figure 2B). These data demonstrate that selumetinib treatment can result in continued PN volume reduction after years of treatment.

Local COVID-19 safety protocols were followed, which resulted in 10 participants missing at least one scheduled re-staging appointment (median: 2 missed re-staging appointments, range: 1–3). Two participants missed their last scheduled re-staging prior to DCO: participant 2 missed their re-staging prior to cycle 73 after maintaining stable disease prior to cycle 67 (Extended Data Figure 3, black squares) and participant 14 missed their re-staging prior to cycle 61 after continuing an sPR prior to cycle 55 (Extended Data Figure 3, gray squares). Participant 16 achieved an unconfirmed PR prior to cycle 21 then maintained stable disease through the beginning of cycle 31. They missed 2 consecutive re-staging appointments due to COVID-19 prior to cycles 37 and 43 before coming off study prior to their next scheduled re-staging appointment prior to cycle 49 (Extended Data Figure 3, gray Xs). Two initial PRs and 1 cPR may be reported later due to missed appointments. Participants 23 and 28 missed re-staging appointments, then achieved initial PRs at their next appointment. Participant 29 achieved an initial PR prior to cycle 5, then missed their re-staging prior to cycle 9. Their re-staging MRIs to confirm a PR ultimately occurred prior to cycles 13 and 17.

Progression-Free Survival

No participants experienced PD relative to baseline tumor volumes, as defined in the protocol, resulting in a progression-free survival (PFS) of 100% (Figure 2C, black line). To evaluate whether tumor volume increased after the time of best response, which was the method used to calculate PFS in the SPRINT trial20, a PFS curve was generated post hoc showing tumor volume increases ≥20% above nadir (Figure 2C, red line). Using this threshold, PFS after 60 cycles (approximately 4.6 years) was 72.9% (95% CI, 52.7%-100%). Median time to progression has not yet been established using either definition of progression.

Patient-Reported and Functional Outcome Measures

All participants (n=33) completed the NRS-1125 and PII26,27 scales at baseline. Subsequent evaluations, including the post-baseline GIC28 scales, were performed prior to cycle 5 (n=30), prior to cycle 9 (n=30), and prior to cycle 13 (n=28). On the NRS-11 significant decreases were measured from baseline (NRS-11=5.93±2.9) to pre-cycle 9 (NRS-11=4.18±3.14, P=0.013) and from baseline to pre-cycle 13 (NRS-11=3.46±3.2, P=0.002). Mean target tumor pain rating decreased from baseline to pre-cycle 5 (NRS-11=4.36±3.1), but did not reach statistical significance (P=0.089 Figure 3A). Mean PII scores decreased significantly (i.e., pain interference improved) from baseline (PII=2.90±1.5) to pre-cycle 5 (PII=1.96±3.1, P=0.006, Figure 3B), from baseline to pre-cycle 9 (PII=2.10±2.0, P=0.027), and from baseline to pre-cycle 13 (PII=1.76±1.7, P=0.002). Participants used the GIC rating scale to assign a numeric value from 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse) to the change in overall symptoms; a score of 4 indicates no change28. This measure indicated minimal improvement pre-cycle 5 (median rating=3, Figure 3C), minimal-to-much improvement pre-cycle 9 (median=2.5), and minimal improvement pre-cycle 13 (median=3). Pre-cycle 13, 23/28 participants (82.1%) reported some degree of improvement. Only 1 participant (1/30, 3%) reported minimally worse pain at pre-cycle 9, and only 1 participant (1/28, 4%) reported much worse pain at pre-cycle 13; the participant reporting much worse pain at pre-cycle 13 had been on a 6-week drug hold approximately 2 months prior to this assessment.

Figure 3:

Patient-reported outcome measures. Participants completed the Numeric Rating Scale-11 (A) and Pain Interference Index (B) at baseline (n=32), then prior to cycles 5 (n=30), 9 (n=30), and 13 (n=28); Global Impression of Change (C) assessments were completed prior to cycles 5, 9, and 13. NRS-11 and PII data were analyzed by two-sided repeated measures ANOVA (NRS-11: F=8.690, P<0.001; PII: F=8.645, P<0.001). (A) NRS-11 rating decreased significantly from baseline prior to cycles 9 and 13 (P=0.013 and 0.002, respectively). (B) Pain Interference Index decreased significantly from baseline prior to cycles 5, 9, and 13 (P=0.006, 0.027, and 0.002, respectively). No other individual contrasts between timepoints were statistically significant. (C) The Global Impression of Change assessment indicated that tumor pain was minimally improved or better in 82.1% of participants (23 of 28 participants) prior to cycle 13. No participants reported that tumor pain was very much worse at any time point. Error bars indicate mean values ± standard deviations. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01.

The most common baseline PN-related symptoms other than pain were motor impairment (24/33 participants, 73%), including muscle weakness and decreased range of motion (ROM). Complete strength data were measured for 13 participants in the target PN quadrant at baseline and pre-cycle 13 evaluations. Of these, 8/13 participants (62%) had any increase in strength, 3/13 (23%) remained the same, and 2/13 (15%) had a decrease during that time. Across all participants, there was no statistically significant change in the median strength score (median intra-participant change: 0.16 [IQR: 0.00–0.33, P=0.311). For ROM, complete baseline and pre-cycle 13 evaluations were completed for 14 participants. Of these, 10 (71%) had any increase in target PN-quadrant ROM, 4 (29%) had any decrease. There was no statistically significant increase in absolute ROM (median intra-participant change: 19.5 degrees [IQR: −0.5–45.5 degrees], P=0.068). However, when ROM Z-scores were calculated, there was a statistically significant improvement with treatment (median intra-participant change: 0.32 [IQR: 0.07–0.80], P=0.027).

Safety and Adverse Event Profile

While not a protocol-defined objective, AEs were compiled post-hoc for the 33 participants evaluable for toxicity. The most common AEs (any grade, at least possibly related to selumetinib) were acneiform rash (32/33 participants, 97%), increase in creatinine phosphokinase level (27/33, 82%), dry skin (23/33, 70%), pruritis (20/33, 61%), increase in alanine aminotransferase level (18/33, 55%), and limb edema (18/33, 55%) (Supplementary Table S1). These AEs occurred only at grade 1 in a majority of participants (55–87%). The highest grade ≥2 AEs per participant are reported (Extended Data Table 1). Acneiform rash was the most common treatment-related AE with 42% of participants (14/33 participants) experiencing grade ≥2. The prevalence of grade ≥2 hypertension was higher in this study (9/33, 27%, all grade 2) than was reported in the SPRINT study (1/50, 2%, grade 2)20. Of the 9 participants with grade ≥2 hypertension, 3 had a baseline history of hypertension that worsened on selumetinib, while the remaining 6 had no significant history of hypertension.

Grade 3 treatment-related AEs included acneiform rash (4/33, 12%), scalp pain (1/33, 3%), intracranial hemorrhage (1/33, 3%), syncope (1/33, 3%), and asymptomatic increases in levels of lipase (1/33, 3%), alanine aminotransferase (ALT, 4/33, 12%), aspartate aminotransferase (AST, 3/33, 9%), creatinine phosphokinase (CPK, 4/33, 12%), and/or serum amylase (1/33, 3%). The only grade 4 AEs were asymptomatic increases in AST and lipase (both n=1). AEs were evaluated based on number of cycles completed (Supplementary Table S2). After cycle 24, the only grade 3 AEs were one instance each of elevated CPK and lipase. No grade 4 AEs occurred after cycle 24 in any participant.

Fourteen participants required dose reductions during this study. The first 2 participants experienced grade 3 acneiform rashes during cycle 1; their doses were changed from 75 mg BID to 75 mg daily. The starting dose was lowered from 75 mg BID to 50 mg BID for all subsequent participants. Twelve additional participants required dose reductions from the 50 mg BID starting dose to 35 mg BID; 4 of these participants required a further dose reduction to 25 mg BID. Of the 14 participants no longer receiving study treatment at DCO, the reasons for discontinuing selumetinib included complicating disease or intercurrent illness (n=3), PI discretion (n=3), participant refusing further treatment (n=3), participant noncompliance (n=2), treatment-limiting toxicity (n=2), and resection of target PN (n=1).

Pharmacokinetics

Blood was collected for steady-state pharmacokinetic analysis on day 28 (±7 days) of cycle 1 or 2, prior to beginning the next cycle, from 27 participants. The mean plasma concentration of selumetinib was 408.4 (±276.0) ng/mL (range: 93.1–1030 ng/mL, Extended Data Figure 4A). Samples were collected an average of 4.5 (±3.0) hours after the participant’s last dose (range: 1.1–12.3 hours). Plasma concentration correlated with time since the participant’s last dose (R2=0.2595). As described in the next section, the time after dosing during which the greatest plasma concentrations were measured was consistent with the times at which the greatest percent reductions in ERK1/2 phosphorylation were measured in tumor biopsies.

Selumetinib Effects on MEK/ERK Signaling

Levels of MEK1/2 and ERK1/2 in tumor biopsies were quantified using an isoform-specific multiplex immunoassay measuring total and phosphorylated analytes29. Paired biopsies were collected from 24/33 participants with minimal complications (Extended Data Table 2). On-treatment biopsies were collected prior to initiating cycle 2 or cycle 3. Selumetinib does not inhibit phosphorylation of MEK1/2; it induces conformational changes in both isoforms that trap them in catalytically inactive conformations30. Consistent with these published findings, phosphorylation ratios of MEK1 and MEK2 increased by medians of 27.9% (range: −89.6%-333.4%) and 31.2% (range: −94.2%-325.6%), respectively, but did not achieve statistical significance (P=0.153 and 0.137, respectively, Figure 4). Statistically significant decreases were measured in the phosphorylation ratios of ERK1 and ERK2, with median values of −64.6% (range: −99.5%-104.3%, P<0.001, Figure 4) and −57.7% (range: −99.9%-84.6%, P=0.001, Figure 4), respectively. Plotting total ERK1/2 and MEK1/2 and phosphorylation ratios as functions of time after dosing indicates that ERK1/2 phosphorylation ratios were suppressed from 2–12 hours after dosing, which is consistent with published data31; no reduction in total ERK1/2 was observed (Extended Data Figure 4B–E). No such suppression in total MEK1/2 or phosphorylation ratios were observed. At baseline, total MEK1 was significantly more abundant than MEK2 (P<0.001, Extended Data Figure 5), while total ERK1 and ERK2 were not significantly different (P=0.414). No significant changes occurred in total MEK1/2 or ERK1/2 levels with selumetinib treatment (Figure 4, P=0.437–0.995).

Figure 4:

Changes in total analyte and phosphorylation ratios of MEK1, MEK2, ERK1, and ERK2 isoforms. Total MEK1, MEK2, ERK1, and ERK2 levels were normalized to total protein levels in tumor lysates (panels A, C, E, and G, respectively). Phosphorylation ratios of each isoform (pSer218/222-MEK1, pSer222/226-MEK2, pThr202/Tyr204-ERK1, or pThr185/Tyr187-ERK2) are shown as the ratio of phosphorylated to total analyte (panels B, D, F, and H). Pre-treatment (i.e., baseline) and on-treatment (prior to cycle 2 or cycle 3) values are indicated as filled black diamonds; unfilled black diamonds indicate that values were outside the range of the assay’s standard curve and were extrapolated. Lines connect paired pre- and on-treatment data points for each biopsy pair. The differences between pre- and on-treatment values are shown as blue diamonds. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Samples sizes (i.e., n values) indicate the number of biopsy pairs for which quantifiable data were collected for each analyte in both pre-treatment and on-treatment biopsies. Error bars represent mean values with 95% confidence intervals. P-values were determined using two-tailed paired t-tests. No significant changes in expression level were measured for any isoform. Apparent increases in phosphorylation ratios of MEK1 and MEK2 were not statistically significant (P=0.153 and 0.137, respectively, panels B and D), while phosphorylation ratios of both ERK1 and ERK2 decreased significantly (P=0.0005 and 0.0002, respectively, panels F and H).

Effects on AKT Signaling and Ribosomal Protein S6 (rpS6)

Mean baseline total AKT3 was significantly higher than mean baseline total AKT1 or AKT2 (Extended Data Figure 5, P<0.001 for AKT3 compared to both AKT1 and AKT2); total AKT1 and AKT2 were not significantly different from one another (P=0.888). Among all AKT isoforms, a statistically significant decrease with treatment was only measured for AKT3 (Extended Data Figure 6; P=0.380, 0.202, and 0.034 for AKT1 AKT2, and AKT3, respectively). Phospho-T:total and phospho-S:total ratios were significantly higher for AKT2 than for AKT1 or AKT3 despite the low total AKT2 at baseline (Extended Data Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure S1). These ratios were not significantly different between AKT1 and AKT3 at either phosphorylation site at baseline. No significant changes in phosphorylation ratios were observed at the phospho-T sites (Extended Data Figure 6; P= 0.687, 0.896, and 0.107 for AKT1, AKT2, and AKT3, respectively) or the phospho-S sites (Extended Data Figure 6, P=0.308, 0.295, and 0.809 for AKT1, AKT2, and AKT3, respectively) of any AKT isoform.

rpS6 is a substrate of both the AKT and MEK/ERK signaling pathways via mTOR (Extended Data Figure 1). Total rpS6 and phospho:total rpS6 ratios for 2 phosphorylation sites were determined in pre-treatment and on-treatment biopsies. In paired biopsies, total rpS6 did not change significantly with selumetinib treatment (Extended Data Figure 7, P=0.225). Phosphorylation ratio of rpS6 at either Ser235 or Ser240/Ser244 did not change significantly in paired biopsies (P=0.731 and 0.851, respectively).

Kinome and transcriptome profiling

For tumor specimens with sufficient flash-frozen material, kinome profiling by multiplexed kinase inhibitor bead (MIB) affinity chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (MS, n=15) and RNA sequencing (n=17) were performed. Comparison of paired samples revealed substantial loss of MIB binding of numerous kinases, but MEK2 (MAP2K2 gene product) was the most statistically significant change observed (P=0.005, Figure 5). Changes in MEK1 (MAP2K1 gene product) were not statistically significant (P=0.142). Response heterogeneity was evident in the top 20 kinases exhibiting the greatest sum decrease in binding (Figure 5). To probe for potential significance of these observed changes and available clinical data, individual kinase log2 fold changes were analyzed with respect to clinical variables using arsenal in R. Notably, the log2 fold change of MEK2 correlated with tumor volumetric change pre-cycle 5 relative to baseline (Figure 5). RNA-sequencing of paired biopsies demonstrated significant changes in 645 genes (P<0.05, log2FC>1) including downregulation of known biomarkers of MAPK activation, DUSP4 (P=0.0004), SPRY4 (P=0.0001), and ETV4 (P=0.005). Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) using the defined Ras pathway geneset confirmed downregulation of this signaling pathway in on-treatment samples (P=0.001, Figure 5). PNs are composed of a complex cellular tumor microenvironment (TME)3. To resolve the potential effects of selumetinib on the cellular compartments of the TME, CIBERSORTx32 was employed using single-cell RNA sequencing of PN biopsies as reference 3. Significant contraction of the macrophage compartment (baseline median 24%; on-treatment median 18%; P=0.002) and expansion of the fibroblast population (baseline median 34%; on-treatment median 46%; P=0.023) were seen across participants but were not correlated with clinical response (Figure 5). These results were supported by immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence analyses demonstrating a decrease in CD68+ cells (likely macrophages) and an increase in vimentin+ cells (likely fibroblasts) with selumetinib treatment (Extended Data Figure 8).

Figure 5:

Kinome and RNA-Seq analyses of tumor biopsies. (A) Kinase log2 LFQ intensities were analyzed using two-sample, unpaired student’s t-test. The most significant change in MIB binding was measured for MEK2. The log2 fold change for MEK1 MIB binding did not decrease significantly. (B) Kinase-specific changes in MIB binding varied between participants. The 20 kinases with the largest sum MIB binding differences are shown. Participant-specific components of each kinase’s sum are color coded as indicated. (C) Correlation between MEK2 expression and tumor volume. MIB binding values for all kinases from paired biopsy samples (n=13) were used for analysis with tumor volumetric measurements using the arsenal package in R. Baseline and pre-cycle 5 tumor volumes were used, while MIB binding values were obtained from biopsies collected at baseline and at either pre-cycle 2 or pre-cycle 3. The correlation between log2 fold change MIB binding of MEK2 and the percent change in tumor volume from baseline to pre-cycle 5 was determined to be significant using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. (* = P<0.05, ** = P<0.01, *** = P<0.001) (D) Ras pathway genes are significantly downregulated in paired PN biopsies after 1 or 2 cycles of selumetinib treatment. Center lines indicate median GSVA scores, box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software, whiskers extend 1.5-times the interquartile range (25th to 75th percentiles). Significance was determined using two-sided paired t-tests (***: P=0.001). (E) Contractions of the macrophage populations were measured in these biopsies, while the fibroblast populations expanded

Discussion

This trial determined the response rate among adults with NF1 and inoperable, growing or symptomatic PNs treated with selumetinib. Our hypothesis was that we would observe similar objective response rates in adults as was seen in children and that we might see clinical benefit even though the tumors have been established for more years. Using volumetric MRI analyses, 63.6% of evaluable participants (21/33) achieved a cPR. Seven participants remain on study after >60 cycles (~5 years) with continued cPR (n=4) or SD (n=3). No participants experienced PD on study as defined by the study protocol, although one participant’s tumor underwent tumor resection after it had grown to 17.6% above baseline volume. Key secondary objectives included analyses of patient-reported and functional outcomes, safety, and the pharmacodynamic responses to selumetinib treatment. Notably, pain scores improved significantly beginning with the pre-cycle 5 assessment. GIC ratings indicated some degree of improvement in PN-related symptoms in 82% of participants after nearly a year on study. The AE profile in this study was similar to that in the pediatric SPRINT trial with the exception of hypertension, which was seen more frequently in the adult study20. No cumulative or new AEs were observed during later cycles and all AEs were reversible. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of paired tumor biopsies demonstrated selumetinib’s mechanism of action, significantly decreasing phosphorylation ratios of ERK1 and ERK2 but not MEK1, MEK2, or AKT1/2/3. A relationship between target inhibition and volumetric response was difficult to assess as no participants had PD, no biopsies were obtained at the time of best response, and timing between the last dose of selumetinib and biopsy collection varied between participants, precluding evaluation of maximal drug effect (Extended Data Figure 4).

Long-term PN growth data were recently reported for 47 adults with NF1 and neurofibromas not receiving MEK inhibitors (median age: 42 years, range: 18–70 years) over a median of 10.4 years33. Among this cohort, the median baseline PN volume was 11.2 mL (range: 0.78–1609.8 mL), while the median baseline PN volume was nearly 100-fold larger in the present study (1066 mL, range: 27–8282 mL, Table 1). In the long-term growth study, the median average annual change in PN tumor volume was −13.7% (range: −16.1 to 469.9%) and 62.3% of PNs shrank spontaneously. No tumors shrank ≥20% within one year and 17.1% of PNs increased ≥20% in volume during this natural history study (median: 81.8% growth, range: 23.8% to 2153.6%). This supports the finding that PN volume reductions measured in our trial were mediated by selumetinib and not the trajectory of PNs in NF1. In a 2-year phase 2 trial of the MEK inhibitor mirdametinib (PD-0325901) for inoperable, progressive or symptomatic PN in participants ≥16 years old, 8 of 19 participants (42%) achieved a partial response34. In a similarly designed phase 2 trial of the multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor cabozantinib, the same PR rate was achieved (42%)35,36. These studies represent the highest published response rates reported to date for adults with NF1-related PNs. The SPRINT trial yielded PRs in 34/50 pediatric participants (68%) with inoperable PNs receiving selumetinib; 28 of these participants (56%) had PRs lasting ≥1 year. The confirmed response rate reported here (63.6%, 21/33 participants) for selumetinib in adult participants was similar to that achieved in the SPRINT trial, with 14/33 participants (42.4%) having responses that lasted ≥1 year. The extended duration drug administration in this trial allowed for demonstration of durable PRs with 19 participants continuing to receive treatment at DCO after completing up to 78 cycles (Figure 2). Four participants enrolled on this study had confirmed progressive disease prior to study enrollment. Three of these participants achieved sPRs for 48+, 44+, and 32+ cycles and remain on study at DCO. The overall response rate is the highest reported to date for adult participants with NF1 and inoperable PNs, and responses within the small group of participants with PD at baseline indicate that selumetinib retains efficacy within this population.

This study also presents a pharmacodynamic view of selumetinib treatment in these participants and is the first study to safely collect and analyze pre- and on-treatment biopsies from participants with PNs. Pharmacodynamic biomarkers demonstrated that selumetinib treatment decreases the phosphorylation ratios of ERK1 and ERK2 without significantly increasing the phosphorylation ratio of any AKT isoform (Figure 4 and Extended Data Figure 6). ERK1/2 phosphorylation ratios were suppressed from 2 to 12 hours after oral dosing, supporting a BID dosing regimen to maintain molecular control of ERK signaling (Extended Data Figure 4). Maximal decreases in ERK1 and ERK2 phosphorylation ratios were 96.7% and 91.5%, respectively. A pharmacodynamics-driven study evaluating the combination of selumetinib with the allosteric AKT1/2/3 inhibitor MK-2206 in participants with metastatic colorectal cancer failed to achieve its objective of 70% decrease in pERK; in 2 participants who achieved ≥70% pAKT inhibition, pERK inhibition was 34% and 13%37. This suggests that inhibition of ERK phosphorylation may be tissue dependent. Although low levels of rpS6 limited our assessment of downstream signaling, the absence of statistically significant increases in total AKT1/2/3 or phosphorylation ratios suggest the AKT pathway is not activated as a compensatory mechanism for ERK inhibition in these tumors (Extended Data Figure 6). This observation offers a possible explanation for the susceptibility of PNs to selumetinib treatment. Kinome profiling of paired biopsies, though restricted to those with sufficient biological material, revealed significant impact of selumetinib treatment on MEK2 (though not on MEK1). Loss of binding of MEK2 in post-treatment samples correlating with volumetric responses is encouraging as a potential predictive biomarker. However, further studies with an increased number of paired biopsies would be required to establish the predictive power of MEK2. Transcriptome analysis confirmed downregulation of Ras signaling and target genes in on-treatment samples, however the magnitude of the observed changes were not correlated with the depth of the clinical response. Interestingly, deconvolution of the expression data revealed significant decreases in the calculated macrophage population within the PN TME and a corresponding increase in the fibroblast population. These results were supported by immunohistochemical and immunofluorescent analyses of macrophage and fibroblast marker expression (Extended Data Figure 8). Given that macrophages typically encompass 20–30% of the total cellular content and are the major inflammatory cell within PNs,38 clearance of these cells may contribute to the observed clinical effect.

This study demonstrates that selumetinib induces sustained tumor volume reduction, suppresses phosphorylation of ERK1/2, and is well tolerated in adults with inoperable, symptomatic or growing PNs. While 63.6% of participants achieved cPRs, 82.1% of patients assessed prior to cycle 13 reported at least some improvement in their GIC rating of tumor-related symptoms, indicating that clinical benefit may be gained even with volume reductions that did not meet cPR criteria. Three participants achieved their initial partial response following at least one dose reduction, and 6 participants achieved their best volumetric response to date following at least one dose reduction. These observations suggest that selumetinib can retain antitumor activity at these lower doses and raises the possibility that lower maintenance dosing could be an option, but this point was outside of the scope of the present study. The AKT signaling pathway is not activated in response to selumetinib treatment, which offers a possible explanation for why MEK inhibitors induce sustained responses with no evidence of resistance in this study. Selumetinib has been approved to treat children with PNs and data from this study indicate that it provides durable clinical benefit to adult patients as well. An ongoing randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 study of selumetinib in adults with NF1 and inoperable PNs has completed enrollment (KOMET, NCT04924608). Expanding the approval of selumetinib to adults with NF1 PNs will be contingent on the efficacy and safety data from that study.

Methods

Trial Design

This study (NCT02407405) was an open-label, NCI-coordinated single-site study conducted at the NIH Clinical Center (Bethesda, MD). The study protocol is available online. This phase 2 study utilized a Simon optimal 2-stage design. Selumetinib was initially administered at the adult recommended phase 2 dose for oncologic indications of 75 mg twice daily approximately every 12 hours on a continuous dosing schedule in 28-day cycles. However, the first 2 participants experienced dose limiting skin toxicity and the study was amended such that all subsequent participants received selumetinib at 50 mg BID, which corresponds to the recommended phase 2 dose of 25 mg/m2 body surface area in children with NF1 PN. Selumetinib was supplied by AstraZeneca PLC in 10 mg or 25 mg capsules and taken with water on an empty stomach (no food or other drinks 2 hours before or 1 hour after dosing). Participants continued to take selumetinib until disease progression as defined below, unacceptable AEs occurred, until the participant chose to withdraw consent, or if the participant and study PI decided it was in the participant’s best interest to stop treatment. Up to 2 dose reductions (to 35 mg BID, then to 25 mg BID) were allowed for treatment-limiting toxicity (TLT) that resolved within 21 days or within 3 months if clinical benefit had been attained (clinical benefit defined as PR in any participant, SD in participants with progressive disease at enrollment, or improved symptoms or function). Continued toxicities after 2 dose reductions would lead to a participant being removed from the study. All participants followed a schedule of evaluations (clinical and laboratory) and PN imaging, with exceptions allowed at investigators’ discretion to accommodate COVID-19 safety protocols.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Institutional Review Board and by the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration. All participants provided written informed consent before participating in this study. All study procedures were performed according to guidelines in the US Common Rule.

Participants

Participants aged ≥18 years old were eligible if they had a germline NF1 mutation documented by a CLIA-certified laboratory or a clinical diagnosis of NF1 based on clinical NIH consensus criteria39. Histologic confirmation of a PN was not required in the presence of consistent clinical and imaging findings. Participants were required to have at least one measurable PN of at least 3 cm in one dimension, be able to swallow intact capsules, and undergo MRI examinations15,40. Eligibility was limited to participants with symptomatic or growing, inoperable PNs, defined as a PN that could not be completely surgically removed without risk for substantial morbidity; up to 10 participants who met all other criteria but could not be safely biopsied were allowed to enroll. The study protocol includes full lists of eligibility and exclusion criteria.

Objectives, Assessments, and Endpoints

The primary objective was to determine the confirmed ORR (ORR) using REiNS criteria for selumetinib in adult participants with inoperable PNs; partial response (PR) is defined as a target PN volume decrease of ≥20% from baseline41. ORR was defined as the number of participants with a confirmed PR, meaning a PR on 2 consecutive re-staging evaluations at least 3 months apart. Sustained PR (sPR) was defined as a PR on at least 3 consecutive scans each at least 3 months apart (6 months total). Stable disease was defined as changes in tumor volume between −20% (decrease) and 20% (increase). Progressive disease was defined as an increase in target PN volume of at least 20% above baseline. Secondary objectives included longitudinal analyses of tumor volumes by 3D MRI, patient-reported and functional outcome measures, measurement of pharmacodynamic biomarker responses in paired tumor biopsies, and correlation of 3D MRI tumor volumetric responses with target inhibition in tumors. Target PNs were classified by imaging appearance as either typical, nodular, or solitary nodular PNs and by histopathology as either atypical neurofibromas42 or typical PN/neurofibromas. Target PN growth prior to study enrollment was defined as progressive (≥20% increase by volumetric analysis, or ≥13% increase in the product of the longest 2 perpendicular diameters, or ≥6% increase in the longest diameter within approximately 3 years prior to enrollment), non-progressive, or unknown (i.e., prior imaging not available or measurable). Participants were not stratified based on any of these classifications for determining the overall response rate, but comparisons of volumetric responses between classifications were performed. All trial objectives are listed in the study protocol (available online).

Statistical Analysis for Primary Objective

A Simon two-stage optimal design was employed. If no more than 5 responses were observed among the first 20 participants, the study would be closed for futility. Otherwise, an additional 15 participants would be enrolled and, if at least 12 responses were observed among up to 35 participants, the trial would be considered positive. This design yielded at least 90% power to reject a null response rate of 0.24 when the true response rate was 0.45 (with one-sided type-I error of at most 0.1). There would be a 0.66 probability of stopping early for negative results under the null hypothesis.

Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

Patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures were administered at baseline and at restaging visits. These evaluations included measures of pain intensity (Numeric Rating Scale – 11 [NRS-11]) and interference of pain with daily functioning (Pain Interference Index [PII])25–27. Participants also completed a measure assessing perceived changes with treatment (Global Impression of Change [GIC] scale) at post-baseline evaluations28. Both the NRS – 11 and GIC scales have been recommended for use in pain assessment in this population43,44. For this study, the NRS-11 scale was modified to ask participants to rate their physician-selected target tumor pain at its worst in the past 7 days. The PII is a 6-item measure that assesses the extent to which pain interferes with daily functioning in the past two weeks and is validated in children and adolescents with NF126. The version used in this study was modified to assess pain interference in adults within the past 7 days. The PII score is obtained by calculating the mean of the 6 items. The GIC scale is a self-report measure of perceived changes that have occurred since starting a new treatment. The measure asks respondents to rate how much their symptoms have changed since pre-treatment on a scale of 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse)28. The scale was modified for the current study to assess perceived change in tumor pain. Repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare changes in pain measures over time.

Functional Outcome Measures

At baseline, the study team determined which PN-related morbidities were present or could develop based on the location of the PN if it were to continue to grow. The present and potential morbidity assignment categories (motor, airway, vision, disfigurement, bowel/bladder, pain, and other) determined which functional assessments would be performed for each participant (Supplementary Table S3). Standardized photography images were obtained for participants with PN-related disfigurement. Detailed analysis methods are described in the Supplementary Materials (Supplementary Methods S1, Supplementary Figure S2, and Supplementary Table S4). Whenever possible, evaluations were performed by the same examiner. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank tests were used to compare baseline and pre-cycle 13 strength and range of motion (ROM) values.

MEK, ERK, and AKT Signaling

Quantitative evaluation of inhibition of MEK, ERK, and AKT phosphorylation was performed as previously described29. Briefly, isoform-specific primary antibodies covalently attached to Luminex magnetic beads bind analytes in the prepared lysates. Beads are washed and detection antibodies bind analytes phosphorylated at specific sites to allow quantitative measurements in a sandwich multiplexed immunoassay format (SOP for sample preparation is available at https://dctd.cancer.gov/ResearchResources/biomarkers/signaling.htm). Detection antibodies against phosphorylated MEK/ERK proteins recognize phosphorylation at Ser218/Ser222 in MEK1, Ser222/Ser226 in MEK2, Thr202/Tyr204 in ERK1, or Thr185/Tyr187 in ERK2. Phosphorylation-specific antibodies against AKT1/2/3 recognize either a phospho-threonine (phospho-T) at position 308, 309, or 305 in AKT1, AKT2, and AKT3, respectively, or a phospho-serine (phospho-S) at position 473, 474, or 472, respectively. Antibodies against phosphorylated rpS6 are specific to phosphorylation at either position Ser235 or Ser240/Ser244.

Statistical analyses of isoform-specific MEK/ERK and AKT phosphorylation were performed by pairwise two-sided T-tests with α=0.05 using GraphPad Prism version 9.3.1. This pairwise analysis allowed direct comparison between isoforms and time points and was followed up with two-way ANOVA of the entire dataset. Significant differences reported in the text reflect T-test results. In some instances, values were outside of the range of the standard curves of the assays. In these instances, values were extrapolated and these data points are clearly indicated in figures.

MIB Chromatography, LC-MS/MS, and Analysis

Kinome profiling utilizes a mixture of linker adapted kinase inhibitors coupled to Sepharose beads to enrich for kinases based on their expression level, activity, and affinity for the bead mixture35,45,46. Subsequent quantification of apparent relative kinase abundance can confirm on-target inhibition and reveal global alterations in the functional kinase network in response to therapy. Flash-frozen tumor samples from paired biopsies were crushed by mortar and pestle in ice-cold multiplexed kinase inhibitor bead (MIB) lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.5) supplemented with complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 1% phosphatase inhibitor cocktails 2 and 3 (Sigma). MIB chromatography was performed as previously described35. Extracts were sonicated 3 × 10 s, and clarified by microcentrifugation (4 deg C, 13,500 × g, 10 min) before quantifying the concentration by Bradford assay. Equal amounts of total protein were gravity-flowed over MIB columns in high-salt MIB lysis buffer (1 M NaCl). The MIB columns consisted of a 125-μl mixture of five type I kinase inhibitors: VI-16832, PP58, purvalanol B, UNC-21474 and BKM-120, which were custom synthesized with hydrocarbon linkers and covalently linked to ECH-Sepharose, except for purvalanol B, which was linked to EAH-Sepharose beads as previously described45,47. Columns were washed sequentially with 5 mL of high salt (1 M NaCl), 5 mL of low salt (150 mM NaCl) MIB lysis buffer, and 0.5 mL low-salt lysis buffer with 0.1% SDS. Bound protein was eluted twice with 0.5% SDS, 1% beta-mercaptoethanol, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8 for 15 min at 100 °C. Eluate was treated with DTT (5 mM) for 25 min at 60 °C and 20 mM iodoacetamide for 30 min in the dark. Following spin concentration using Amicon Ultra-4 (10k cut-off) to ~100 μL, samples were precipitated by methanol/chloroform, dried in a speedvac and resuspended in 50 mM HEPES (pH 8.0). Tryptic digests were performed overnight at 37 °C, extracted four times with 1 mL ethyl acetate to remove detergent, dried in a speedvac, and peptides further cleaned using C-18 spin columns according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Pierce). Peptides were resuspended in 2% ACN and 0.1% formic acid. Approximately 40% of the final peptide suspension was injected onto a Thermo Easy-Spray 75 μm × 25 cm C-18 column and separated on a 120 min gradient (5–40% ACN) using an Easy nLC-1200. The Thermo Orbitrap Exploris 480 MS ESI parameters were as follows: Full Scan – Resolution 120,000, Scan range 375–1500 m/z, RF Lens 40%, AGC Target-Custom (Normalized AGC Target, 300%), 60 sec maximum injection time, Filters – Monoisotopic peak determination: Peptide, Intensity Threshold 5.0e3, Charge State 2–5, Dynamic Exclusion 30 sec, Data Dependent Mode – 20 Dependent scans, ddMS2 – Isolation Window 2 m/z, HCD Collision Energy 30%, Resolution 30,000, AGC Target – Custom (100%), maximum injection time 60 sec. Raw files were processed for label-free quantification by MaxQuant LFQ (version 1.6.11.0) using the Uniprot/Swiss-Prot human protein database and default parameters were used with the following exceptions—only razor+unique peptides were used, carbidomethyl (C) fixed modification, and oxidation (M) and acetyl (protein N-term) dynamic modifications, and matching between runs was utilized. In Perseus software version 1.6.10.50 (Max Planck Institute), kinase LFQ intensities (minimum 2 razor+unique peptides) were log2 transformed and missing values were imputed by column using default parameters (width 0.3, down shift 1.8). Kinase log2 LFQ intensities (MIB binding estimates) were used for two-sample, unpaired student’s T-test and for correlation to clinical variables using the arsenal package in R.

RNA Extraction and Bulk RNA Sequencing

Flash-frozen tumor samples from paired biopsies were subjected to RNA purification using a Qiagen RNeasy Plus Mini kit essentially as described in the manufacturer’s protocol. After adding the RLT lysis buffer supplemented with beta-mercaptoethanol, samples were homogenized using QiaShredder columns. Samples were also subjected to on-column Dnase I treatment to remove genomic DNA. RNA samples were first evaluated for quantity and quality using Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100. RNA quality was mostly low with RNA integrity number (RIN) ranging from 1.7 to 8.3, most of which had RIN of 2–3. However, all samples had DV200 more than 60%. The total amount of RNA also had large variation, ranging from 4.7 to 500ng, most of which were less than 50ng. As a result, samples were grouped by starting amount of RNA for library preparation, in groups of 5ngs, 10ngs, 20ngs, 50ngs and 100ngs. cDNA library preparation included cDNA synthesis, dA tailing, ligation of indexed adaptors, and amplification, following the SureSelect XT HS2 RNA System with Pre-Capture Pooling Protocol Version C0, June 2022 (Agilent Technologies), with some modifications. Briefly, all RNAs were treated as FFPE samples with no heat fragmentation due to heavy RNA degradation. One hour of adaptor ligation and 14 cycles of pre-hybridization PCR were applied to the sample groups starting less than 10ngs, while 30 minutes of adaptor ligation and 12–13 cycles of pre-hybridization PCR were used to sample groups starting more than 10ngs. Libraries were then pooled 4 libraries per pool in equal amount. Pooled libraries were then hybridized, captured, and amplified with Agilent Human All Exon V7 probe set (48Mb, hg38). Each resulting captured library pool was quantified and its quality assessed by Qubit and Agilent Bioanalyzer. Average size of library insert was about 180bp. The pooled libraries were further pooled in equal molarity. The pooled libraries were then denatured and neutralized, before loading to NovaSeq 6000 sequencer at 300pM final concentration for 100b paired-end sequencing (Illumina, Inc.). Approximately 30M raw reads per library were generated. A Phred quality score (Q score) was used to measure the quality of sequencing. More than 90% of the sequencing reads reached Q30 (99.9% base call accuracy). Partek Flow was used to generate count matrices from FASTQ files and DESeq2 package 1.41.8 was used to calculate differential gene expression comparisons between baseline and on-treatment samples. The differential gene list was used to perform gene set enrichment analysis with R package GSVA v1.48.348. The input list was ranked based on log2(fold change) and compared against Msigdb hallmarks gene set as well as De Raedt’s Ras pathway gene set49. Single-cell gene expression data from four reference PNs were processed using the Seurat package in R3. Low-quality cells were removed, and gene expression values were normalized. Standard integration using the reciprocal principal component analysis (rPCA) pipeline was applied to the data, which allowed for batch correction of single-cell data while preserving biological variability. To provide an overview of the different cell types present in the single-cell gene expression data, clusters were generated based on the integrated dataset, and cells were assigned cell identity labels based on well-defined markers. Next, a signature matrix was built for each cell type in the bulk RNAseq dataset using the CIBERSORTx algorithm32. The average gene expression threshold was set to 0.5 (in log2 space) for cells with the same identity/phenotype showing evidence of expression. The minimum and maximum number of barcode genes to consider for each phenotype when building the signature matrix were set to the default range of 300 to 500. The CIBERSORTx cell fraction mode was used to deconvolute 45 bulk RNA-seq samples, including 25 pre-treatment samples and 20 on-treatment samples. “S-mode” was enabled to correct for batch effects that occur when comparing a single-cell matrix with bulk RNAseq data. Statistical analysis included 500 permutations. A t-test was performed to test if there was a statistical difference between cell proportion before and after treatment.

Immunohistochemistry staining

Immunohistochemistry for CD68 was performed using the Benchmark Ultra automated stainer and pre-diluted anti-CD68 (KP-1, Roche Diagnostics). Pre-treatment was done with Ultra Cell Conditioning Solution (CCl) for 36 minutes, the primary antibody for 30 minutes, and standard UltraView Universal DAB Detection Kit. Human tonsil was used as the positive control.

Multiplex Immunofluorescence (mIF)

Deparaffinization of 5 μm sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue was achieved through a series of xylenes and decreasing ethanol concentrations. Antigen retrieval was conducted using 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 005000) for 45 minutes at 95°C. After allowing sections to cool to room temperature (RT), BLOXALL blocking solution (Vector Laboratories, SP-6000–100) was applied for 10 minutes at RT to inhibit non-specific binding. Sections were washed in PBS before incubation with the primary antibody specific to the antigen of interest, which was diluted in PerkinElmer’s antibody diluent (Akoya Biosciences, ARD1001EA) and left for 1 hour at RT. Primary antibodies were mouse anti-α-SMA (1:500 dilution, Dako, MO851) and rabbit anti-Vimentin (1:10,000 dilution, Cell Signaling Technology, 5741). Following three washes in TBS, the sections were incubated with Vector ImmPRESS HRP anti-mouse or -rabbit (Vector Laboratories, MP-7452–50 and MP-7451–50, respectively) diluted 1:4 in PBS for 10 minutes at RT. The tyramide signal amplification system was employed using a 1X working amplification buffer (Biotium, 22029), with 0.0015% H2O2 (Millipore-Sigma, 386790–100ML). CF dye (Biotium, CF488 92171, CF660 92195) was diluted 1:250 in the H2O2 amplification buffer to create the working Tyramide Amplification Buffer, which was incubated for 10 minutes at RT and protected from light. This procedure was sequentially repeated for each primary antibody and its corresponding secondary antibody using a fluorophore-conjugated tyramide. After completing multiplex staining, nuclei were counterstained with VECTASHIELD Hardset Antifade Mounting Medium containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories, H-1500–10), cover-slipped, stored protected from light, and imaged within 7 days on a Zeiss Axioscan 7 at 20X magnification.

Image Acquisition and Analysis

Stained slides were digitized ensuring uniform illumination and focus across the entire tissue section. Digital images were imported into the HALO image analysis software platform (HALO Indica Labs, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA; https://www.indicalab.com/halo/). Regions of interest (ROIs) were manually delineated using HALO’s annotation tools. Color thresholds were established on no-treatment slides where applicable. The specific algorithm used was Area Quantification FL v2.3.4, calibrated to match the magnification and staining characteristics. Settings were adjusted to align with the fluorophores’ emission spectra used in the staining protocol. Color thresholds were set to ensure accurate detection of each tissue component. Following threshold adjustments, the software’s algorithm automatically calculated the area within the marked boundaries. Parameters such as total area, percentage area, and staining intensity were recorded for each ROI. Images were cropped, merged, and optimized using Photoshop 24.7 (Adobe) and were arranged using Illustrator 27.5 (Adobe).

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1:

Signaling pathway overview. Inactive Ras-GDP can release GDP and become activated by binding GTP. Ras-GTP activates signaling via the RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K pathways. Neurofibromin functions as a negative regulator of this signaling by maintaining the inactive Ras-GDP. When neurofibromin is mutated (i.e., in patients with neurofibromatosis), that regulation of the RAF and PI3K pathways is lost. Selumetinib does not inhibit MEK phosphorylation. When MEK is inhibited by selumetinib, phosphorylation of its enzymatic substrate ERK is inhibited. Phosphorylation of rpS6 can still be achieved via PI3K/AKT/mTOR despite MEK inhibition by selumetinib. Other factors involved in these pathways and other pathways regulated by Ras have been omitted for clarity.

Extended Data Figure 2:

(A) PN-related morbidities present during baseline evaluation are presented by category. Comorbidities present during baseline evaluation (blue squares) were assigned to one of 7 categories. Several participants had more than one morbidity in the “Other” category; those morbidities included sensory deficit (n=14), abnormal gait (n=2), hearing loss (n=2), facial dysfunction (n=1), inability to carry pregnancy to term (n=1), kyphosis (n=1), leg asymmetry (n=1), nocturia (n=1), post-surgery neurogenic bladder (n=1), pes cavus (n=1), and sexual dysfunction (n=1). (B) Z-score change from baseline to pre-cycle 13 evaluations demonstrates that 2 participants (20 and 21) had significant ROM impairment at baseline (Z-score <−2) that was no longer significant at the later timepoint; no participants experienced significant ROM worsening by this evaluation. (C) While some participants (20 and 22) demonstrated modest improvement, no statistically significant change in converted Kendall Score as measured.

Extended Data Figure 3:

(A) Spider plot showing tumor volume change from baseline for each participant through DCO. Percent tumor volume changes for each participant at each re-staging scan are shown using unique combinations of marker shape and color for each participant as indicated. Participants 31 and 33 did not meet screening criteria and participants 5 and 18 came off study prior to their first re-staging scans; no data are available for these participants. Participant 1 (black circles) continues to experience sPR after 78 cycles (approximately 6 years on study, PR lasting ≥48 cycles). Participant 14 (gray squares) achieved the greatest reduction in tumor volume (48.1%). Participant 7 (blue triangles) had a prolonged drug hold prior to cycle 66 and their data are censored at the time of this hold; they resumed treatment and remain on study at DCO. (B) Participant 14 (gray squares in part A) had archival images available from participation in the NIH natural history study. MRI images are shown from the prior study at age 15.5 years (left image), at the time of enrollment on this study (age 21.6 years, center image), and at the last re-staging prior to DCO (age 25.6 years, right image). Tumor volumes are graphed versus age during both studies with the natural history study indicated as a black line and the current study as a red line.

Extended Data Figure 4:

Plasma concentrations and percent changes in total analyte levels and phosphorylation ratios as a function of time since last dose. (A) Plasma concentrations tended to decrease as sampling time progressed further from the time of the last dose. Colors and shapes of data markers indicate individual participants and correspond to the markers used to indicate tumor volume in Extended Data Figure 3. Not all participants had blood collected for PK analysis and only those from whom samples were collected are indicated in the legend. (B) Total MEK1 (blue) and MEK2 (orange) remained near or above baseline across most time points. (C) Mean phosphorylated:total MEK1 (blue) and MEK2 (orange) ratios increased with selumetinib treatment, but neither achieved statistical significance across all quantifiable paired biopsies (P=0.153 and 0.137, respectively). (D) No significant changes were measured in total ERK1 (blue) or ERK2 (orange) concentrations. (E) ERK1 (blue) and ERK2 (orange) phosphorylation ratios were consistently suppressed from approximately 2 to 12 hours after dosing (P=0.0003 and 0.0002 for ERK1 and ERK2, respectively, for all quantifiable paired biopsies).

Extended Data Figure 5:

Isoform-specific total MEK, ERK, AKT, and rpS6 levels. Total protein levels from all quantifiable pre-treatment biopsies (n values indicated in figure) are shown regardless of whether paired biopsies were available or quantifiable. Black bars indicate mean values and error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. (A) Total MEK1 was significantly more abundant than MEK2 (P=0.0006); total ERK2 was not significantly different from total ERK1 (P=0.414). P-values were calculated using ordinary one-way ANOVA analyses and Šidák’s multiple comparisons test. (B) Total AKT1 and AKT2 were not significantly different from each other (P=0.888), while total AKT3 was significantly more abundant than either AKT1 or AKT2 (P=0.0009 and 0.0001, respectively). P-values were calculated using ordinary one-way ANOVA and Sidák’s multiple comparisons test; F values were 8.046 for the MEK/ERK analysis and 11.07 for the AKT1/2/3 analysis. (* = P<0.05, ** = P<0.01, *** = P<0.001)

Extended Data Figure 6:

Comparison of isoform-specific total AKT and site-specific phosphorylated:total analyte ratios. Total levels of AKT1, −2, and −3 (panels A, B, and C, respectively) were normalized to total protein levels in tumor lysates. Phosphorylation ratios for each isoform at the phospho-T site (panels D, E, and F) and the phospho-S site (panels G, H, and I) are shown as the ratio of phosphorylated to total analyte. Pre-treatment (i.e., baseline) and on-treatment (prior to cycle 2 or cycle 3) values are indicated as black diamonds; lines connect paired pre- and on-treatment data points for each biopsy pair. The differences between pre- and on-treatment values are shown as blue diamonds. Error bars represent mean values with 95% confidence intervals. Samples sizes (i.e., n values) indicate the number of biopsy pairs for which quantifiable data were collected for each analyte in both pre-treatment and on-treatment biopsies. P-values were determined using two-tailed paired t-tests. Total AKT3 decreased significantly from the pre-treatment to on-treatment biopsies (P=0.0034). No significant changes were measured in phosphorylation ratios at the phospho-T and phospho-S sites for AKT1 (panels D and G), AKT2 (panels E and H), and AKT3 (panels F and I). The number of paired biopsies that yielded quantifiable data for AKT1 was limited due to low total and phosphorylated analyte levels. (* = P<0.05, ** = P<0.01, *** = P<0.001)

Extended Data Figure 7:

Total rpS6 (A) and phosphorylated:total ratios for the Ser235 and Ser240/244 phosphorylation sites (B and C, respectively). Samples sizes (i.e., n values) indicate the number of biopsy pairs for which quantifiable data were collected for each analyte in both pre-treatment and on-treatment biopsies. Error bars represent mean values with 95% confidence intervals. P-values were determined using two-tailed paired t-tests. No significant changes in total rpS6 or phosphorylation ratio were measured. (* = P<0.05, ** = P<0.01, *** = P<0.001)

Extended Data Figure 8:

H&E, CD68, vimentin, and alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) staining of pre- and on-treatment biopsies. (A) Representative H&E demonstrated stable histologic findings between baseline and on-treatment samples and anti-CD68 staining images from participants 8 and 21 demonstrated diminished CD68+ cells, likely macrophages, in the on-treatment samples, consistent with the RNA-Seq result. A total of 16 biopsy pairs were analyzed. (B) Representative anti-vimentin (yellow) and anti-α-SMA (green) staining images from participants 6 and 9 demonstrated increased vimentin+ cells, likely fibroblasts, in the on-treatment samples, consistent with RNA-Seq data. A total of 6 biopsy pairs were analyzed.

Extended Data Table 1:

Highest grade ≥2 adverse events at least possibly related to selumetinib per participant during any cycle

| Grade | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTCAE v5.0 Category | Adverse Event | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|

| ||||

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | Anemia | 2 | ||

|

| ||||

| Cardiac disorders | Sinus tachycardia | 1 | ||

| Other - Left ventricle dilation | 2 | |||

| Other - Left ventricular function decreased | 1 | |||

|

| ||||

| Eye disorders | Blurred vision | 1 | ||

| Other - Elevated intraocular pressure | 1 | |||

|

| ||||

| Gastrointestinal disorders | Abdominal pain | 1 | ||

| Diarrhea | 4 | |||

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 1 | |||

| Mucositis - Oral | 3 | |||

| Nausea | 2 | |||

|

| ||||

| General disorders and administration site conditions | Edema - Limbs | 3 | ||

| Fatigue | 3 | |||

|

| ||||

| Immune system disorders | Lupus | 1 | ||

|

| ||||

| Infections and infestations | Folliculitis | 3 | ||

| Nail infection | 1 | |||

| Paronychia | 8 | |||

| Skin infection | 1 | |||

|

| ||||

| Investigations | Alanine aminotransferase increased | 4 | ||

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 3 | 1 | ||

| Blood bilirubin increased | 2 | |||

| CPK increased | 8 | 4 | ||

| Ejection fraction decreased | 6 | |||

| Lipase increased | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 1 | |||

| Lymphocyte count increased | 1 | |||

| Neutrophil count decreased | 1 | |||

| Serum amylase increased | 3 | 1 | ||

|

| ||||

| Metabolic and nutrition disorders | Hypoalbuminemia | 1 | ||

| Hypocalcemia | 1 | |||

| Hypophosphatemia | 3 | |||

|

| ||||

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | Back pain | 1 | ||

| Buttock pain | 1 | |||

| Muscle cramp | 1 | |||

| Other - Neck muscle weakness | 1 | |||

|

| ||||

| Nervous system disorders | Dizziness | 2 | ||

| Headache | 1 | |||

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 1 | |||

| Presyncope | 1 | |||

| Syncope | 1 | |||

|

| ||||

| Psychiatric disorders | Depression | 2 | ||

| Insomnia | 2 | |||

|

| ||||

| Renal and urinary disorders | Proteinuria | 1 | ||

|

| ||||

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | Dry skin | 3 | ||

| Pruritis | 5 | |||

| Rash - Acneiform | 11 | 4 | ||

| Scalp pain | 1 | |||

| Skin ulceration | 2 | |||

| Other - Hair thinning | 1 | |||

| Other - Psoriasiform dermatitis | 1 | |||

|

| ||||

| Vascular disorders | Flushing | 1 | ||

| Hypertension | 9 | |||

Extended Data Table 2:

Biopsy information

| Participant | PN Location | Target Lesion? | PN Status at Enrollment | Tumor Type on Imaging | Basline PN Pathology | Best Target PN Response | Biopsy collection? | Paired pMEK/pERK Analysis? | Paired Kinome Analysis? | Paired RNAseq Analysis? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Pre | On | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| 1 | R Neck | Y | PD | SN | Atypical NF | cPR | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 2 | L Thigh | Y | SD | Typical PN | NF | cPR | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 3 | R Thigh | Y | SD | Typical PN | NF | cPR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| 4 | R Thigh | Y | SD | Typical PN | NF | cPR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | L Thigh | N | SD | Typical PN | Atypical NF | N/A | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 6 | L Arm | Y | PD | SN | Atypical NF | cPR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | Back | Y | Unknown | Typical PN | NF | cPR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | L Buttock | Y | SD | Typical PN | NF | uPR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 9 | L Hip | N | PD | Typical PN | NF | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 10 | Sacrum | Y | SD | Typical PN | Atypical NF | SD | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 10 | L Chest | N | SD | SN | Atypical NF | N/A | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 11 | R Arm | Y | PD | SN | Atypical NF | SD | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 14 | R Neck | Y | SD | Typical PN | Atypical NF | cPR | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 15 | R Retroperitoneal Mass | Y | SD | SN | NF | cPR | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 16 | L Thigh | Y | SD | Typical PN | Atypical NF | uPR | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 17 | R Knee | Y | SD | Typical PN | Atypical NF | SD | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 18 | L Buttock | Y | SD | Typical PN | NF | SD | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 19 | L Neck | Y | SD | Typical PN | NF | cPR | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 20 | L Buttock | Y | Unknown | Typical PN | NF | SD | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 21 | R Thigh | Y | Unknown | Typical PN | NF | cPR | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 21 | R Knee | Y | Unknown | Nodular PN | Atypical NF | cPR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 22 | L Knee | Y | SD | Typical PN | NF | cPR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| 23 | Neck | Y | SD | Typical PN | NF | cPR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 24 | L Shoulder/Arm | Y | SD | Typical PN | ANNUBP | SD | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 25 | R Abdomen | N | Unknown | Typical PN | Atypical NF | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 26 | R Shoulder | Y | Unknown | Typical PN | Atypical NF | cPR | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 27 | L Knee | Y | SD | SN | NF | uPR | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 27 | R Arm | N | Unknown | SN | ANNUBP | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 29 | L Flank | N | SD | Typical PN | NF | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 30 | R Neck/Head | Y | SD | Nodular PN | NF | cPR | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 32 | R Thigh | N | Unknown | SN | NF | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| 34 | L Knee | Y | Unknown | Typical PN | NF | cPR | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

SN: solitary nodular; NF: neurofibroma; ANNUBP: atypical neurofibromatous neoplasm of uncertain biologic potential

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all trial participants. We also thank Muhammad Bashir and Andrea Lucas from the NCI’s Pediatric Oncology Branch (POB), Neeraja Syed, and the NCI’s Childhood Cancer Data Initiative for their contributions to this study. This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract Number HHSN261200800001E and by the NIH, NCI, Center for Cancer Research Intramural Research Program. AstraZeneca/Alexion provided selumetinib and clinical trial support through a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement with the NCI Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. This research was further supported by a Developmental and Hyperactive Ras Tumor SPORE funded through the NIH/NCI (Project Number 5U54CA196519–05 awarded to SPA, SDR, and DWC).

Financial Support:

This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract Number HHSN261200800001E and by the NIH, NCI, Center for Cancer Research Intramural Research Program. AstraZeneca/Alexion provided selumetinib and clinical trial support through a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement with the NCI Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. This research was further supported by a Developmental and Hyperactive Ras Tumor SPORE funded through the NIH/NCI (Project Number 5U54CA196519–05).

Footnotes

Competing Interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Data Availability