Abstract

The present work is a detailed analysis of the numerical and positional parameters of cell proliferation in all of the derivatives of the wing disk. We have made use of twin clones resulting from mitotic recombination events at three different ages of development. The interfaces between twin clones indicate the relative position in the anlage of the mother cells. Interface types vary with age of clone initiation and with wing regions. They are indicative of the main allocation of postmitotic cells of the growing clones. Growth is exponential and intercalar, i.e., the progeny of ancestor cells becomes more and more separated. Clones are compact, indicating that daughter cells tend to remain side by side. The shape of the clones is wing region characteristic. Subpopulations of cells grow preferentially along veins and wing margins and show characteristic shapes in different pleural regions. The shape and size of the adult wing regions largely depend on the shape of clones and hence of the allocation of successive rounds of daughter cells. The role of mitogenic morphogens in wing size and shape is discussed.

In multicellular organisms morphogenesis highly depends on cell proliferation. Morphogenesis relates to the genetic mechanisms that determine specific sizes and shapes. Morphogenetic analyses need a detailed description of growth in terms of cell lineages. Cell lineage studies reveal spatial and numerical parameters of ordered cell proliferation, an indication of genetic control of cell behavior. The wing disk of Drosophila melanogaster possibly is, in this sense, the best-studied growing anlage. The imaginal wing disk is a monolayer of cells that give rise to the adult epidermis of the dorsal mesothorax, including notum and wing. Cell lineage analyses of the disk have been carried out with mitotic recombination clones labeled with mutant but gratuitous cell markers (1, 2). These clonal analyses have revealed clonal restrictions that separate so-called “compartments,” subdividing the early anlage in four major compartments, anterior/posterior (A/P) and dorsal/ventral (D/V). A subsequent subdivision separates notum and pleura from the wing proper (3, 4). New clonal restrictions, less stringent than in compartment boundaries, later symmetrically subdivide the dorsal and ventral wing compartments into sectors delimited by the veins (5, 6). Cell proliferation within these compartments and wing sectors is more undetermined with clone borders overlapping in the same regions of different wings. The shape of these clones is, however, region characteristic, symmetrical in both dorsal and ventral surfaces and near symmetrical in both anterior and posterior compartments (1, 2); see ref. 7 for review.

In the wing disk and the presumptive wing blade in particular, cell proliferation increases the number of cells in an exponential mode, with an average cycle time of 8.5 h (8). The wing disk primordium in the embryo contains about 20 cells and the proliferation period ends with about 50,000, the equivalent to 10–11 rounds of cell division (8). Direct observation of growing imaginal discs has shown that clusters of neighboring cells, not clonally related, enter both the S phase of the cell cycle and mitosis in synchrony (9). Anaphases in a cluster are randomly oriented in the planar axis, but subsequently the two daughter cells allocate along either the A/P axis (y axis) or the proximo-distal axis (x axis) (9). Moreover, the shape of the clones in the growing disk corresponds with that of the clones seen in the adult wing, indicating that there are no major changes in the relative position of neighboring cells during the eversion of the disk at metamorphosis (9). During the larval and pupal periods cell death in the disk affects a very low number of cells in the hinge. There are therefore no major morphogenetic changes associated with cell death in late larval or pupal stages (10).

But how do these morphogenetic parameters relate to the final constant wing shape and size? It has been proposed that compartment boundaries work as “organizers” of compartment growth and patterning. Along the growing A/P boundary, the selector gene engrailed (en), acting in the P compartment, elicits the expression of genes encoding for diffusible ligands. In the P compartment en directs the expression of hedgehog (hh), and through it promotes the expression of decapentaplegic (dpp) in a few cells in the A compartment. These morphogens are proposed to promote cell proliferation and later vein patterning (see refs. 11–14 for reviews). In a similar way, in the D/V boundary the selector gene apterous (ap) expressed in the dorsal compartment affects the regulation of the downstream effector wingless (wg), another diffusible ligand, which has been suggested to act as a morphogen in growth and patterning from the D/V boundary (see refs. 11–13 for reviews). However, whereas the role of these morphogens in the wing pattern formation is well established, their role in the control of cell proliferation leading to size and shape of the wing remains elusive (13, 15, 16).

In this work we analyze in detail the cell proliferation parameters of the wing anlage by using twin clones, the labeled offspring of the daughter cells of a cell in which a mitotic recombination event has taken place. In this way the topological position of the mother cell of a clone and its subsequent growth can be estimated and the geometrical parameters of cell proliferation can be evaluated.

Materials and Methods

Clonal Analysis.

Clones in the adult.

Mitotic recombination was generated by the FLP/FRT technique (17), by heat shock treatment in a water bath at 37°C for 10 min. f36a hs-FLP; mwh P{f+}77a FRT80B/FRT80B larvae were treated at 38–62, 48–72, or 60–84 h after egg laying (AEL). A total of 712 twin clones were studied (230 at 38–62 h, 204 at 48–72 h, and 278 at 60–84 h).

Clones in larval discs.

Mitotic recombination was generated by the FLP/FRT technique, by heat shock treatment in a water bath at 37°C for 30 min. hs-FLP; P{2×GFP} FRT40A/FRT40A larvae were treated at 24–48, 48–72 or 70–96 h AEL. Larvae were dissected during the third larval stage. Twin clones were visualized in a BioRad Radiance 2000 confocal microscope. Seventy twin ventral clones were studied. The multiple wing hair (mwh) and forked36a (f36a) mutations and the 2×GFP and wild-type forked transgene (f+) are gratuitous genetic variants in proliferating cells. We have found no systemic differences in the number of cells (size) of the twin clones. Thus, in the adult wing the f/mwh size correlation coefficient is 1.0294 ± 0.4.

Staining and Antibodies.

Dissected larvae were fixed for 20 min in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution in PBT (PBS/0.1% Tween 20) and inmunostained with either anti-Engrailed antibody (1:4) or anti-Armadillo antibody (1:20) in PBT-BSA (PBT/0.3% BSA). An Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated secondary anti-mouse antibody (Molecular Probes) was used to detect primary antibodies localization. Anti-Engrailed (18) and anti-Armadillo (19) antibodies were provided by the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, Iowa City. To determine nuclei shape, density, and localization, discs were stained for 20 min in a 1 mM To-Pro-3 iodide (Molecular Probes) solution in PBT and washed three times in PBT for 20 min.

Results

Clones in the Adult Cuticle.

The wing blade: Position of clone mother cells.

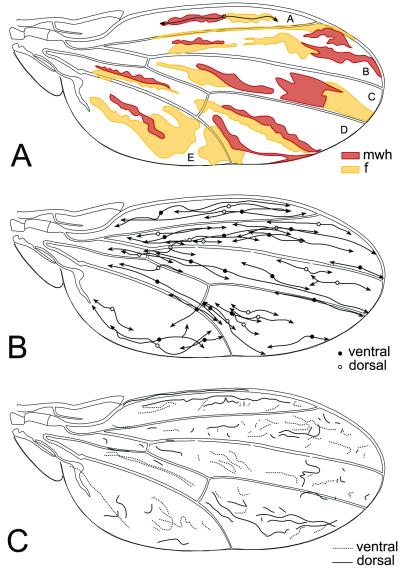

The use of twin clones allows us to reveal the topological position of mother cells. That topological position corresponds to some point in the interface between the twin clones. Twin clones may appear in tandem along the proximo-distal (x) axis of the wing, run parallel along the A/P (y) axis, or a combination of both (Fig. 1A). In the first type, the interfaces are of few cells, in the second of many cells, indicating a preferential location of daughter cells along the proximo-distal axis of the wing blade. A plot of tandem clones on the wing shows that the position of the mother cells can be anywhere in the anlage (Fig. 1B). Because longitudinal twin clones extend at both sides of these positions (Fig. 1B) it follows that cell proliferation is intercalar, with successive mother cells being more and more separated from the location of the first mother cell of the twin. That must apply to parallel clones as well, and thus the topological position of the mother cell of the twin must be in the middle of the interface of parallel clones and by extension in the center of clones. Because twin clones are of similar size, proliferation is, in addition to intercalar, exponential in all of the wing cells of the wing blade. This finding applies equally to both dorsal and ventral wing surfaces.

Figure 1.

Clones in the adult wing. (A) Some examples of representative twin (f and mwh) clones; A–D, wing sectors. They were initiated at 48–72 h AEL. Arrows indicate main axes of the twin clones starting in the topological position of the mother cell (circle). (B) Plot of twins in both wing surfaces. (C) Interfaces of the twin clones.

The ratio of longitudinal to transverse width (measured in number of cells) of clones varies with the age of clone initiation. This ratio is 9.78 in clones initiated at 50 h AEL, 5.51 for those at 60 h, and 2.83 for those at 72 h. Previous work had shown that whereas mitotic spindles appear in the planar axis at random in clusters of dividing cells, the daughter cells allocate either longitudinally or transversally in the wing anlage (9). Those ratios reflect the alternating orientation of the first cell division of the mother cell of twin clones. Thus, those figures indicate that the wing blade anlage grows preferentially distalward at the beginning and more isodiametrically at the end of development.

The wing blade: Shape and size of clones.

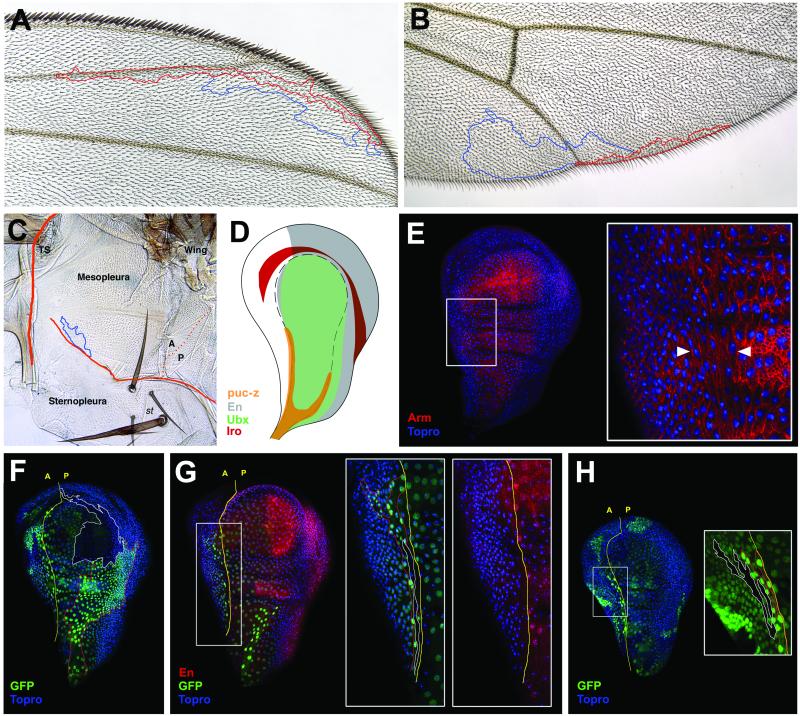

A plot of twin interfaces in the wing reveals some precision to these general trends. In Fig. 1C we observe mainly longitudinal interfaces in wing sector A and D whereas transversal interfaces are abundant in other regions. Longitudinal interfaces and clones bend in the distal wing margin to run parallel to it. Longitudinal clones tend also to be associated with certain pattern elements such as veins. This histotypic restriction can extend for hundreds of cells (Figs. 2A and 3 A and B). In fact, the veins are associated with late restriction borders (5). The same restriction applies to long narrow clones running along the wing margin in both most anterior and most posterior margins (Fig. 2A). There are some indications that the posterior wing margin may be considered a hidden vein, because of the expression along it of rhomboid (rho) (a vein-specific marker) (20) and the absence of blistered (bs) (specific of intervein regions) (21). Thus, an early determination of cells to become vein histotype may be associated with a particular mode of cell proliferation.

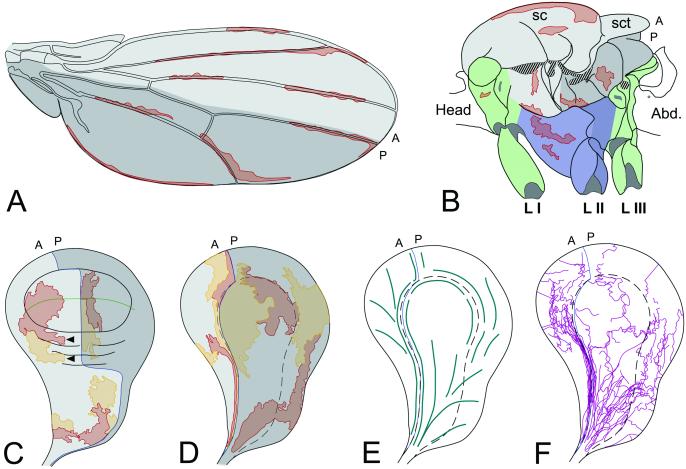

Figure 2.

Different shapes of clones in different adult regions (A and B) and interfaces of the wing disk (C–F). (A) Outlines of clones running along the veins and the wing margin. (B) mwh clones in a notum and pleura lateral view (and coxa of first and second legs). Blue background in second leg distinguishes imaginal discs derivatives. All thoracic regions, except mesothorax, are in green. Bases of wing (in mesothorax) and haltere (in metathotax) are in shadow. Black lines mark thorax sutures. sc, scutum; sct, scutellum; Abd., abdomen; L I, L II, and L III, first, second, and third legs. (C) Twin (red and yellow) clones in the dorsal side of the disk. Arrows point to clones growing perpendicular to the A/P compartment boundary. Green line separates dorsal from ventral wing surfaces. (D) Twin clones in the most ventral side of the wing disk. (E) Main directions of the clones. (F) Interfaces of twin clones. A, anterior; P, posterior compartments. (C–F) Blue lines mark A/P boundary. (D–F) Dash lines separate squamous cells from cylindric cells. Dark gray marks posterior compartments.

Figure 3.

Representative clones in the adult and imaginal wing disk. (A and B) Cases of twin clones in the adult wing veins (A) and wing margin (B). Note in B that the f (blue) clone does not reach the wing margin. mwh has a red outline. (C) Clones running parallel to the border of the wing disk and second leg derivatives. Thick orange line separates prothorax from mesothorax. Thin orange line separates mesopleura from sternopleura. Dotted line marks wing A/P boundary. TS, thorax spiracle; st, sternopleural chaetae. (D) Scheme of gene expression pattern of several histotypic markers in the ventral surface: puckered-Lacz (puc-z), Engrailed (En), Ultrabithorax (Ubx), Iroquois (Iro). (E) Expression of Armadillo (red) marking apical cell membranes and To-Pro-3 iodide (blue) marking cell nuclei, show the morphology of fusiform cells (white arrows) between cylindrical (pleura) and squamous cells (peripodial membrane). (F) Twin 2×GFP (red outline)/0×GFP (white outline) clones in the peripodial and the posterior pleura. (G) Twin clone in the ventral horn of fusiform cells. Late third instar disk. (H) Similar twin clones in early third instar disk, showing the elongated clone shape with cell body shorter than later, as observed in G. (E–H) Wing discs are at the same magnification; (Insets) higher magnification.

Those clonal restrictions may cause asymmetries in size of twin clone size, because one of the members of the twin cannot cross them. This situation applies mainly to clones between the basal trunks of veins, where clones are smaller than in more distal regions (80% of clones in proximal regions show these asymmetries). These singularities also reflect postmitotic cell allocation and therefore are indicative of differential cell behavior during cell proliferation associated with imaginal histotypes. Interestingly, at 50 h AEL, when the disk contains about 200 cells, 58.3% of the twins that abut the D/V compartment boundary, the interface of the twin runs along the wing margin boundary. Twin clones initiated later, after the D/V clonal restriction, are in either the dorsal or the ventral surface.

Clones are very compact. “Split” clones, members of a clone separated from the main body by more than one cell diameter are rare: 5.2% in early (50 h) clones (n = 136; clone size of about 400 cells). These clones consist of groups of fewer than 10 cells. In one case, a clone was split in two groups of 300 and 160 cells each. Thus split clones are preferentially late events. Reciprocally, few (a total of 2–30) nonmarked cells within clone territories are also rare: 1.2% of early initiated (50 h) clones. They appear in the borders of the clone. Related to these split clones is indentation in clone borders. This finding is very frequent in the most posterior wing sector of the wing, perhaps reflecting a hidden vein plexate, the “anal plexus.”

Notum and pleura.

The same clonal analysis in regions of the mesothorax other than the wing blade reveals new territorial specificities in cell proliferation. In the notum the cell marker f is not very reliable for trichomes and the data correspond to mwh clones. In the notum, large (early initiated) clones are more isodiametric than clones in the wing blade, although they have a main A/P component (Fig. 2B) (1, 2). Clones running along the border between both heminota are narrow and long (see below). Clones crossing the notal sutures do not show differences in shape, an indication that these infolded cuticles (apodemes) do not represent clonal restrictions. In fact, direct counting of cells in the adult sutures shows very few cells (data not shown).

In the pleura, clones are also rather isodiametric although they run preferentially perpendicular to the notum/pleura sutures (Fig. 2B). They run parallel to the junction between wing pleura and the derivatives of the mesothoracic leg disk (Figs. 2B and 3C). Thus, the regions connecting the contralateral discs and the ipsolateral leg disk show a preferential elongated shape along the adult borders. This situation may extend to the junction between the wing and the haltere discs of the same side but we do not have enough large clones to confirm it. A survey of twin clones in the legs also indicates a preferential growth along the legs in narrow clones (data not shown) (1).

Clones in the Imaginal Wing Disc.

In the imaginal disk twin clones are marked by the expression of four doses of green fluorescent protein (GFP) (4×GFP) vs. 0×GFP in a background of 2×GFP (see Fig. 3 F–H). The twin clones visualized in the imaginal disk of late third instar larvae show the same features observed in the adult cuticle. This applies to the presumptive wing blade and notum (Fig. 2C). Clones are compact with clone interfaces in tandem, in parallel, or composite. They are mainly elongated in the proximo-distal axis in the wing blade, where, depending on age of clone initiation, they may cross the D/V boundary or be separated by it (Fig. 2C). Clones in the wing base can extend to more central regions of the hinge (arrows in Fig. 2C), although clones in the (dorsal) notum are, again like in the adult, more isodiametric and can grow along the A/P compartment boundary or perpendicular to it but always with shapes in position characteristic ways.

A more complex, albeit constant, clonal pattern appears in the ventral side of the wing disk, which corresponds to the adult pleural regions (Fig. 2 E and F). The pleural region in the disk contains about 600 squamous cells (the peripodial membrane; Fig. 3 D and E) as well as cylindrical cells like in the rest of the epithelium. The borders of this cell shape discontinuity are not sharp, but can be defined easily (dash lines in Fig. 2 E and F and 3D). In addition, there is a stripe of very elongated fusiform cells at both sides of the A/P boundary, anterior to the peripodial membrane (Fig. 3E). We have used gene expression as a way of labeling the different pleural regions (Fig. 3D). Ultrabithorax (Ubx) is expressed mainly in squamous cells of the peripodial membrane (22). The puckered-LacZ (puc-z) marker appears as a double horn (23), in the anterior horn the cells are fusiform running to the stalk of the imaginal disk (Fig. 3D). Given the squamous shape of the cells of the peripodial membrane, clones appear large in surface but contain few cells. Clones including the fusiform cells run parallel to the A/P boundary with a width of only one cell (Figs. 2D and 3 G and H). This clone and cell elongation starts early in development because it is noticed in early third larval instar discs (Fig. 3H). More distal cells of the same clone or its twin expand to the rest of the ventral surface (Fig. 2D). Large clones seem to be distally restricted to either side of the histologic border of the peripodial membrane (Fig. 2D). The main trends in the shape and extension of clones in the ventral surface of the wing disk are visualized in a plot in Fig. 2 E and F. Clones expand in distal regions and become elongated and narrow in proximal (stalk) regions, where they are defined by parallel bundles of cells of different lineages. During disk eversion in metamorphosis, wing blade, notum, and pleura pass through this stalk to merge with the derivatives of ipsolateral and contralateral discs.

Discussion

The use of twin clones has allowed us to get a detailed insight in how ordered cell proliferation generates the shape and size of the growing wing disk. The interface between the twin clones reveals the topological position of the mother cell of both clones. It follows that for daughter single clones the mother cell is topologically located in its center. Interfaces appear everywhere in the adult wing but with shape, extent, and positions that are wing sector and initiation age specific. Frequencies and position specificities correspond to the developmentally changing location of clusters of cells in the G2 stage of the cell cycle, when the cells are sensitive to induced mitotic recombination (5, 9). Mitotic spindle orientations in the planar axis of the wing epithelium are random, but postmitotic cells allocate preferentially along the x or y axis of the wing blade (24). The shape of interfaces reflects the main orientations of successive clonal cell divisions. The fact that twin clones are of similar sizes and mother cells appear anywhere in the wing indicate that growth is exponential and intercalar. Clones are in the wing blade preferentially longitudinal, along the proximo-distal axis, with ratios of length/width always larger than one (9.8 in early clones and 2.8 in late ones). Thus, cell allocation and growth in the wing occurs in a proximo-distal direction at the beginning, perpendicular to the base of the primordium, and more isodiametricaly or anterior-posteriorly later. This finding is in agreement with the expansion of distances between precursor cells in gynandromorph maps when compared with the derived adult landmarks (25).

There are regional differences in these general cell allocation trends. The preferential longitudinal orientation of growth in intervein sectors changes to parallel to the wing margin in anterior and posterior wing borders and perpendicular to the margin in the tip of the wing. In contrast, clones in the notum are more isodiametric with the exception of a ribbon of cells along the thorax middle line between contralateral discs. Departures from the regularity of the geometry of clones in wing sectors appear in the wing veins and wing margin. Narrow clones may run for hundreds of cells of vein histotype (5), revealing a connection of cell allocation to hystotipical cell specification. The rule of similar clone sizes in twins that applies to the wing blade and notum is broken in several regions of the wing disk. Clones abutting the base of the veins are smaller than those in the distal wing sectors. The same applies to the D/V wing margin (but not the A/P boundary) and to cells that differentiate the squamous territory of the peripodial membrane, its most distal border and the “horns” of fusiform cells anterior to the peripodial membrane and connecting the pleura with the disk stalk. These restrictions in growth may reflect, like in the veins, the appearance of differently specified (or differentiated) cell populations that may act as clonal boundaries (see gene expression patterns in Fig. 3D). These constraints to growth and shape of the clones indicate that the anlage is formed as a mosaic of differently specified cell territories with local limits related to cell proliferation constraints.

Clones and members of twin clones appear very compact, with all of the clone cells remaining side by side, with the exception of rare “islands” and “lakes” that originate late in development. Why members of the clone remain together is difficult to explain whether daughter cells move freely in the epithelium. This behavior may reflect an inertia or delay in the separation of daughter cells, perhaps in the formation of new membranes (26) or the connection of cells by filopodia that retain cell recognition or adhesion features. As a whole, it is the allocation of proliferating cells in the disk that relates to the final shape of the wing. Clone shape in imaginal discs (Fig. 2C) can directly be transformed into the shape of clones in the adult, indicating the absence of morphogenetic movements or separation of neighbor cells in the eversion of the disk (9). However, the eversion of the wing imaginal disk through the stalk connecting it to the larval epidermis at metamorphosis may be an exception. The eversion of the disk poses morphogenetic problems (27, 28). How is the stalk, which is few cells in circumference, enlarged to make a border of hundreds of cells with ipsolateral and contralateral discs?

We now turn to the question of the role of morphogens (such as dpp or wg) in the growth and morphogenesis of the imaginal disk. The role of diffusible morphogenes in patterning of the anlage is well documented. dpp concentration thresholds determines the expression of region-specific transcription factor genes like spalt (sal), spalt-related (sal-r) (29–31), and optomotor blind (omb) (32) in the wing blade in the early disk. On the other hand, wg is operational in the definition of the wing margin and in the expression of transcription factors distalless (dll) (33) and vestigial (vg) needed for distal wing specification (34, 35). The same genes are operative later in the differentiation of pattern elements, wg in the wing margin and dpp in veins. The role of these genes in growth or cell proliferation is less clear (see below). The absence of dpp or its receptors, such as thickveins (tkv), prevents cell proliferation in clones. The clonal overexpression of activated receptor tkvQ253D leads to extra growth in pleural regions but less so in the wing blade, where mutant cells do not intermingle with surrounding cells in mosaics (36). wg overexpression clones initiated during larval development are normal in the wing blade (37). These observations are compatible with a permissive role rather than an instructive one of these two classical morphogens in an ordered cell proliferation.

We have not found in the present work any relationship between the known gradient of morphogens emanating from compartment borders in cell proliferation, either in mitotic rates or in clone shapes or main orientations. We have seen that growth seems to be related rather to regional specifications. We will see its relation to positional heterogeneities of the proliferating cells. Patterned cell proliferation varies in a number of morphogenetic mutants. For example, en mutant wings show a mirror image transformation of a posterior compartment into an anterior one. This substitution is correlated with a pattern of cell proliferation like in the anterior compartment (38). The gene nubbin (nub) encoding a transcription factor (39) causes in mutant condition smaller wings reduced along the proximo-distal axis (x axis). In nub mutant wings cells show preferential alocation perpendicular to that axis (40). Mutations in genes related to ligands and receptors of several signaling pathways reveal cell behaviors that point to the existence of positional values in wing sectors. Thus, in genetic mosaics, mutant clones may show failures in the preferential allocation of daughter cells. Clones of Notch (N) mutant cells impair cell proliferation and tend to growth toward veins (41). Similar behavior applies to clones of mutations in extramacrochaetae (emc), encoding a negative cofactor of basic helix–loop–helix transcription factors (42). veinlet (rhove) mutations, which encodes for a transmembrane protein of the Drosophila epidermal growth factor receptor signaling pathway, directs cells to grow away of veins, where the wild-type gene is maximally expressed (43). Contrarily bs, encoding the Drosophila serum response factor (44) and expressed in interveins, in the mutant condition in mosaics causes cells to grow toward and differentiate as veins (21). In genetic mosaics, clones of nub mutant cells grow toward the base of the wing (40). These mutant cell behaviors reveal properties of cells that relate to the generation of space and the acquisition of positional values (see below). Cell allocation possibly reflects preferential cell adhesion and/or affinity properties that relate to position, as shown in cell dissociation and reaggregation experiments (45). Positional values seem to be intimately related to growth. vein (vn), a ligand Drosophila epidermal growth factor receptor, causes in mutant combination with rhove, in mosaics, lower cell proliferation and reduction of the intervein regions (43), as it occurs in emc territories that abut neighboring veins (42).

A generative model of wing morphogenesis has been presented [the Entelechia model (6, 46)], in which dividing cells acquire positional values intermediate between those of neighboring cells and are allocated according to these values in intermediate positions along the x and y axes by cell–cell recognition to the best matching positions in this positional values landscape. These values relate to the activity of so-called “martial” genes, which determine highest values at restriction borders and lowest away from the border. The highest values are in compartment boundaries at the beginning and are substituted by vein restriction boundaries later. With cell proliferation in the anlage, boundary values increase up to a species-specific maximum. Intercalar cell proliferation continues until intermediate values reach a specific minimum where the value differences between neighboring cell become indistinguishable i.e., the anlage reaches the Entelechia condition.

This model accounts for and explains several observations. The formation of a new A/P boundary in mosaics of en in the posterior compartment and of a new D/V boundary in ap mosaics in the dorsal compartments is associated with nonautonomous extraproliferation. This observation was the basis for the proposal of a mitogenic role for the dpp and wg ligands arising in those boundaries (11–13). The observations that the size of these overgrowths depends on the position of the clone rather than on the extent of the border, and that this growth ends in pattern duplications, suggests a different interpretation. It may result from positional “accommodation” reminiscent of intercalar growth in regeneration experiments (43). This positive accommodation can be negative in nub mosaics that nonautonomously cause reduced growth distally to the mutant territory (40). The activities of these mutations (emc, N, Drosophila epidermal growth factor receptor, and nub) are related to the acquisition of positional values. Low values (caused by Drosophila epidermal growth factor receptor) and high values (by emc) may fail to elicit lack of intercalary cell proliferation in wing sectors, because of mutant cells having similar (low or high) positional values.

Thus, the morphogenetic role of dpp (and wg) morphogens could affect the wing vein patterning first, and the vein restriction borders, or gene expression discontinuities, will act later as positional references to intercalary cell proliferation. In this later stage these morphogens will then be permissive rather than instructive in cell proliferation. It seems from this work that wing size and shape result from highly determined cell lineages with a controlled postmitotic cell allocation in internal wing regions rather than from instructions of diffusible morphogens emanating from clonal restriction borders. Size and shape of the wing seem rather to be locally determined by cell interactions of the proliferating cell population.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Carroll, E. Bier, L. A. Baena, and other members of the lab for reading and discussing this work. We also thank the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for providing antibodies. This work was supported by grants from the Dirección General de Investigación Científica y Técnica and an institutional grant from the F. Ramón Areces to the Centro de Biología Molecular Severo Ochoa. J.R. is a fellow of the Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid, and P.S.-C. is a fellow of the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

Abbreviations

- A/P

anterior/posterior

- D/V

dorsal/ventral

- AEL

after egg laying

- PBT

PBS/0.1% Tween 20

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

References

- 1.Bryant P J, Schneiderman H A. Dev Biol. 1969;20:263–290. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(69)90015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Bellido A, Merriam J R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:2222–2226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.9.2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia-Bellido A, Ripoll P, Morata G. Nat New Biol. 1973;245:251–253. doi: 10.1038/newbio245251a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Bellido A, Ripoll P, Morata G. Dev Biol. 1976;48:132–147. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(76)90052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez-Gaitan M, Capdevila M P, Garcia-Bellido A. Mech Dev. 1994;46:183–200. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)90070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Bellido A, de Celis J F. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;26:277–304. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.001425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen S M. BioEssays. 1996;18:855–858. doi: 10.1002/bies.950181102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia-Bellido A, Merriam J R. Dev Biol. 1971;24:61–87. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(71)90047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milan M, Campuzano S, Garcia-Bellido A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:640–645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milan M, Campuzano S, Garcia-Bellido A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5691–5696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blair S S. BioEssays. 1995;17:299–309. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawrence P A, Struhl G. Cell. 1996;85:951–961. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teleman A A, Strigini M, Cohen S M. Cell. 2001;105:559–562. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pages F, Kerridge S. Trends Genet. 2000;16:40–44. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01880-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neufeld T P, de la Cruz A F, Johnston L A, Edgar B A. Cell. 1998;93:1183–1193. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81462-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawrence P A. Curr Biol. 2001;11:R638–R639. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chou T B, Perrimon N. Genetics. 1992;131:643–653. doi: 10.1093/genetics/131.3.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel N H, Martin-Blanco E, Coleman K G, Poole S J, Ellis M C, Kornberg T B, Goodman C S. Cell. 1989;58:955–968. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90947-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riggleman B, Schedl P, Wieschaus E. Cell. 1990;63:549–560. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90451-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sturtevant M A, Roark M, Bier E. Genes Dev. 1993;7:961–973. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.6.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roch F, Baonza A, Martin-Blanco E, Garcia-Bellido A. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1998;125:1823–1832. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.10.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brower D L. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1987;101:83–92. doi: 10.1242/dev.101.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agnes F, Suzanne M, Noselli S. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1999;126:5453–5462. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.23.5453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milan M, Campuzano S, Garcia-Bellido A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11687–11692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ripoll P. Roux Arch Entwicklungsmech Org. 1972;169:200–215. doi: 10.1007/BF00582553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knox A L, Brown N. Science. 2002;295:1285–1288. doi: 10.1126/science.1067549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guillermet C M P. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1980;57:107–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fristrom D, Fristrom J W. Dev Biol. 1975;43:1–23. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(75)90127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Celis J F, Barrio R, Kafatos F C. Nature (London) 1996;381:421–424. doi: 10.1038/381421a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lecuit T, Brook W J, Ng M, Calleja M, Sun H, Cohen S M. Nature (London) 1996;381:387–393. doi: 10.1038/381387a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nellen D, Burke R, Struhl G, Basler K. Cell. 1996;85:357–368. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grimm S, Pflugfelder G O. Science. 1996;271:1601–1604. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zecca M, Basler K, Struhl G. Cell. 1996;87:833–844. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81991-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams J A, Paddock S W, Vorwerk K, Carroll S B. Nature (London) 1994;368:299–305. doi: 10.1038/368299a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim J, Sebring A, Esch J J, Kraus M E, Vorwerk K, Magee J, Carroll S B. Nature (London) 1996;382:133–138. doi: 10.1038/382133a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin-Castellanos C E B. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2002;129:1003–1013. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.4.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baonza A, Garcia-Bellido A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2609–2614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040576497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia-Bellido A, Santamaria P. Genetics. 1972;72:87–104. doi: 10.1093/genetics/72.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ng M, Diaz-Benjumea F J, Cohen S M. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1995;121:589–599. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cifuentes F J, Garcia-Bellido A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11405–11410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Celis J F, Garcia-Bellido A. Mech Dev. 1994;46:109–122. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Celis J F, Baonza A, Garcia-Bellido A. Mech Dev. 1995;53:209–221. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00436-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia-Bellido A, Cortes F, Milan M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10222–10226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montagne J, Groppe J, Guillemin K, Krasnow M A, Gehring W J, Affolter M. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1996;122:2589–2597. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garcia-Bellido A. Dev Biol. 1966;14:278–306. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(66)90017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.García-Bellido A, García-Bellido C A. Int J Dev Biol. 1998;42:353–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]