Abstract

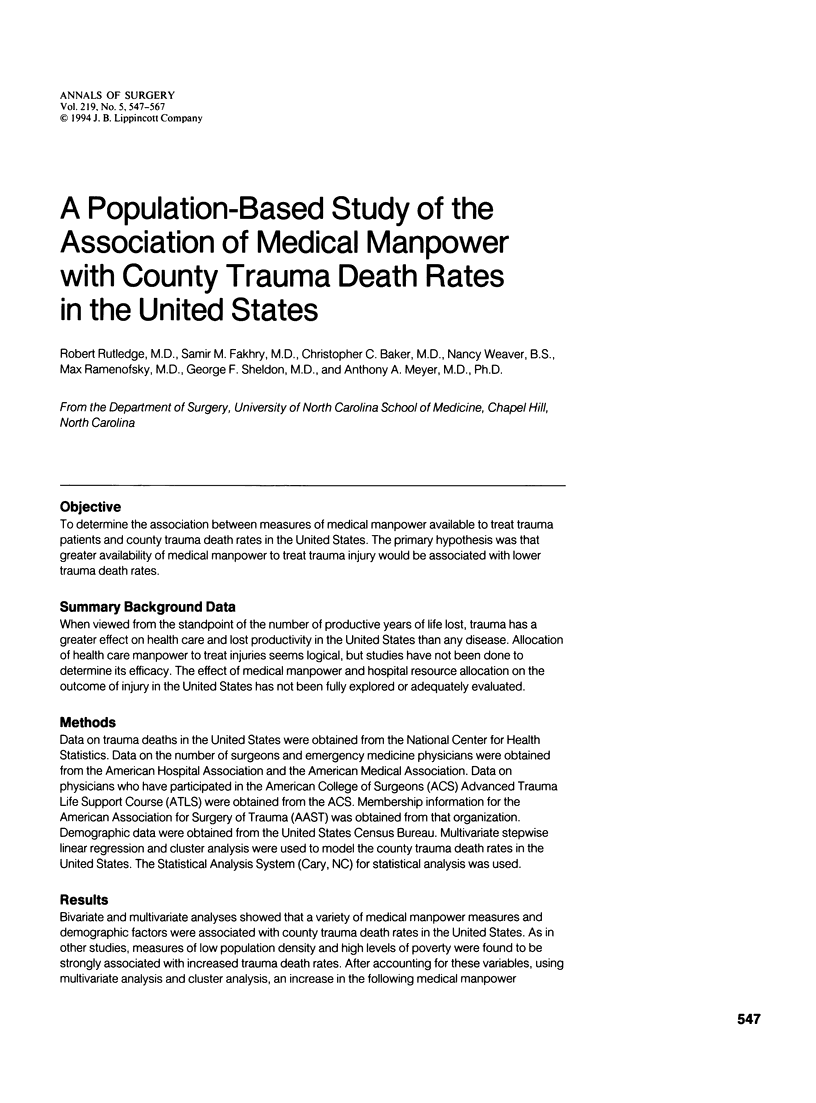

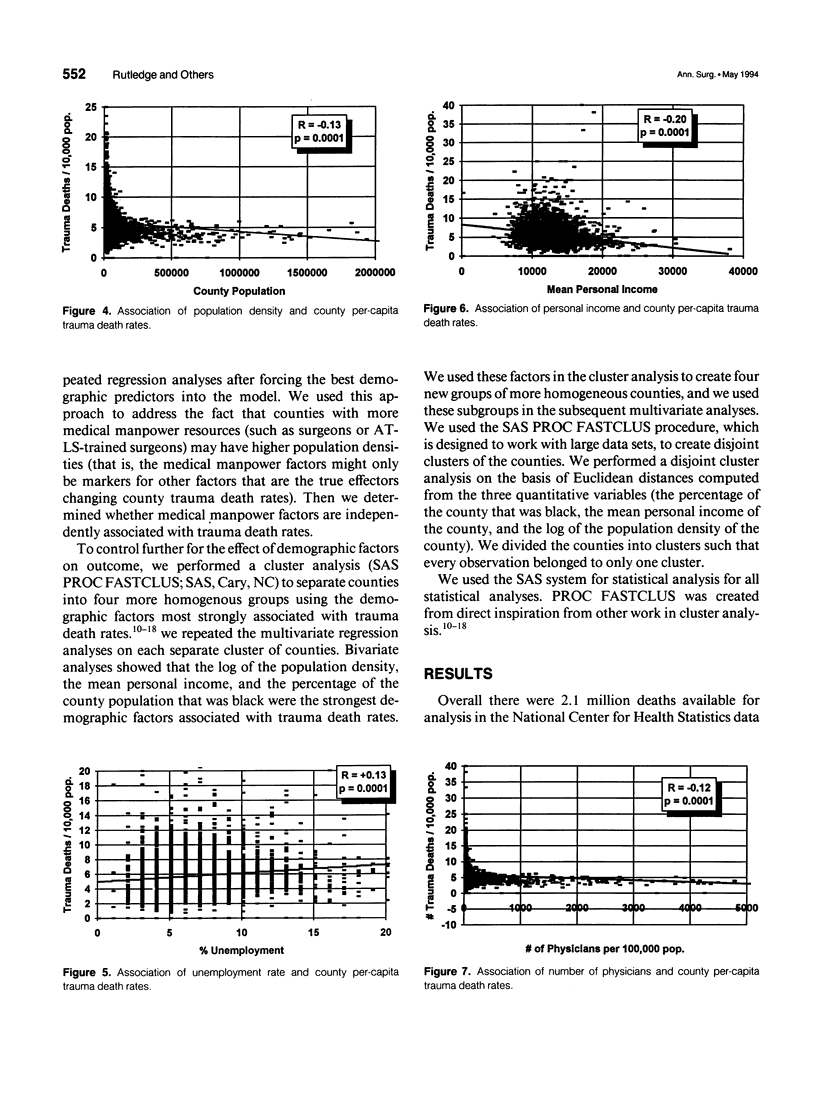

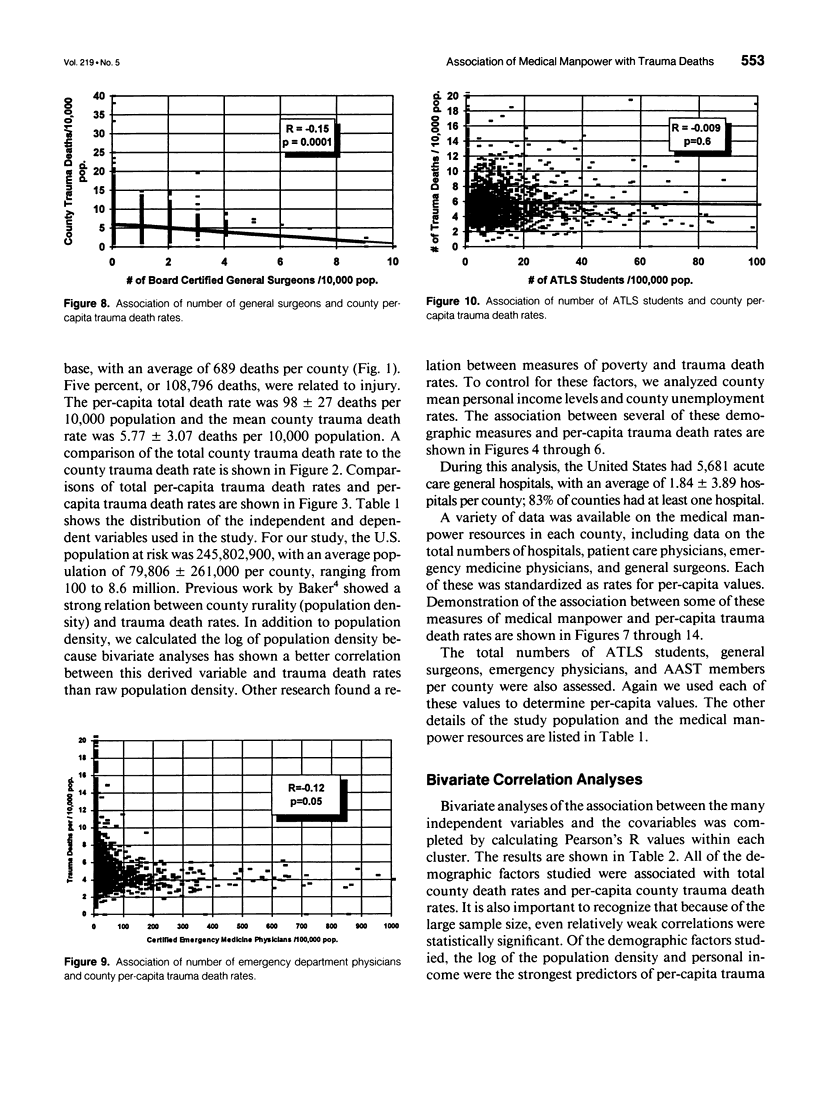

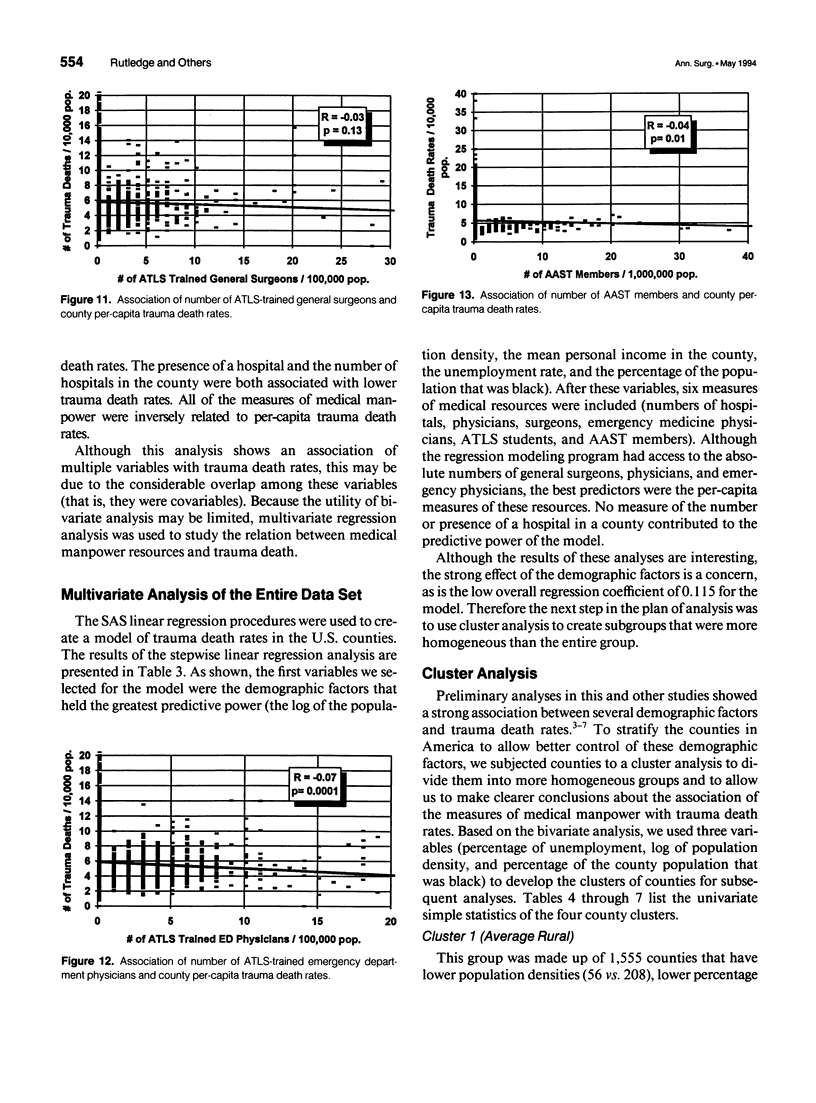

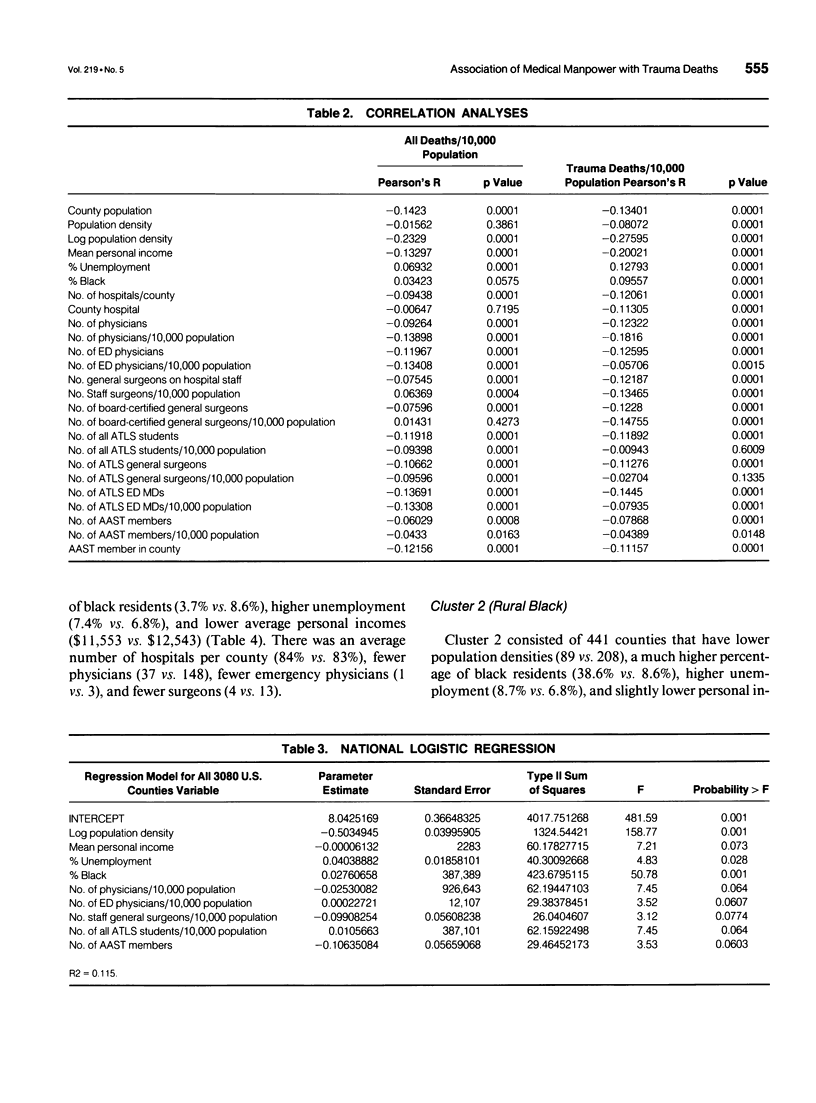

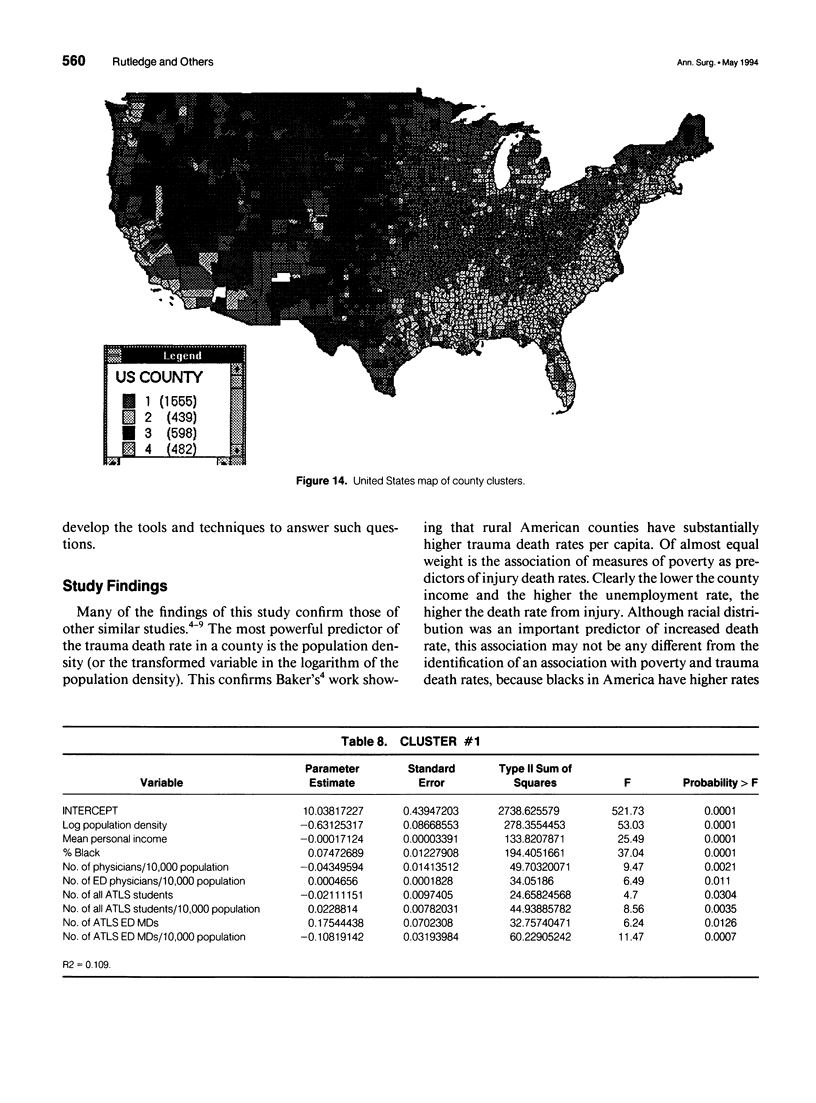

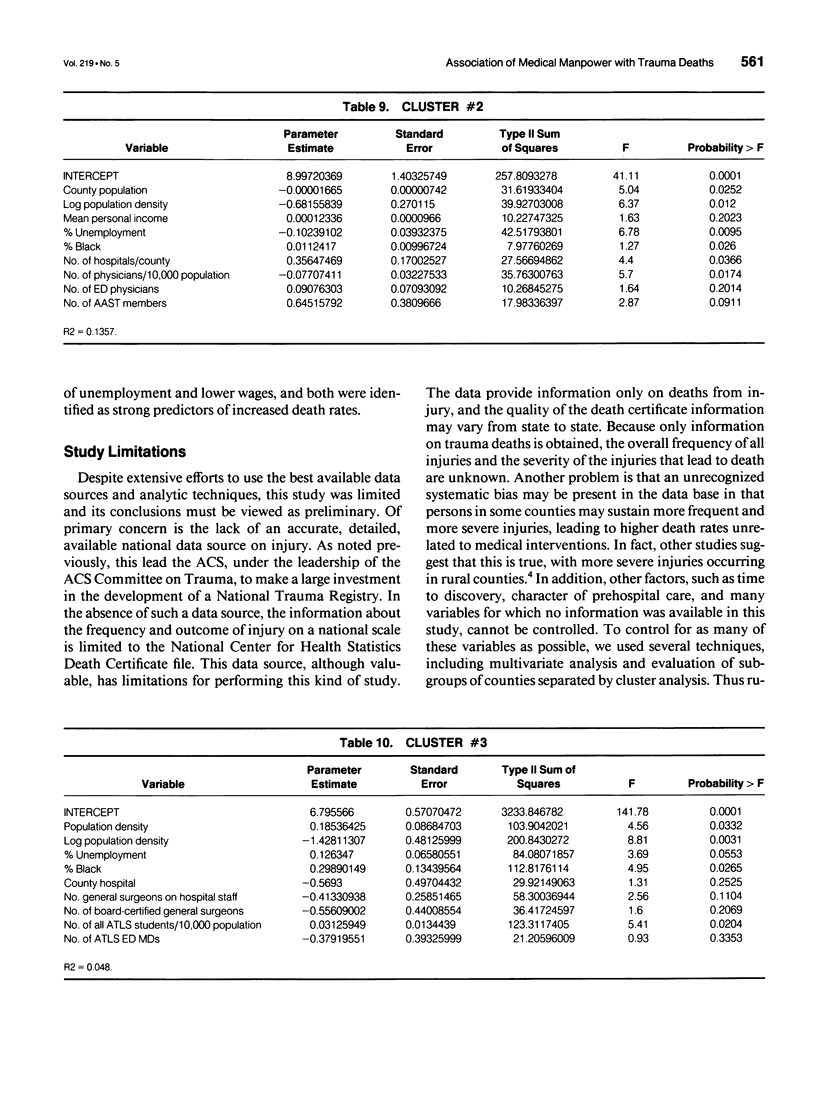

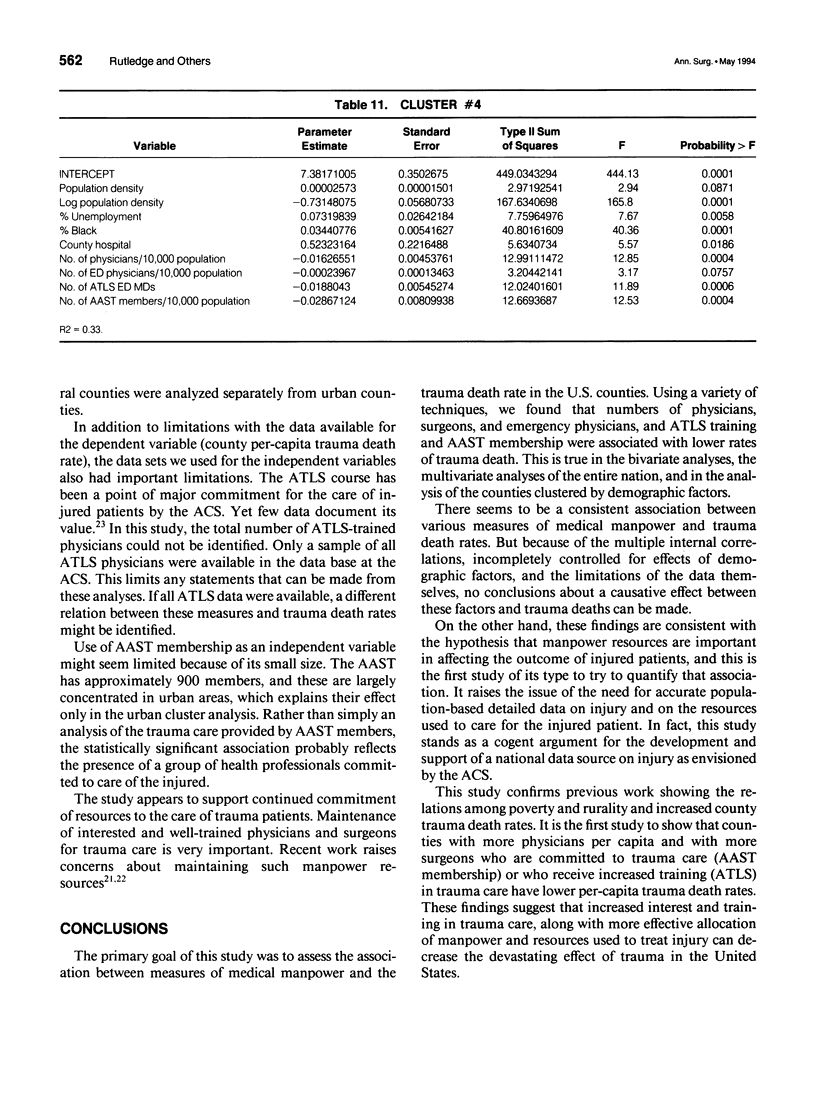

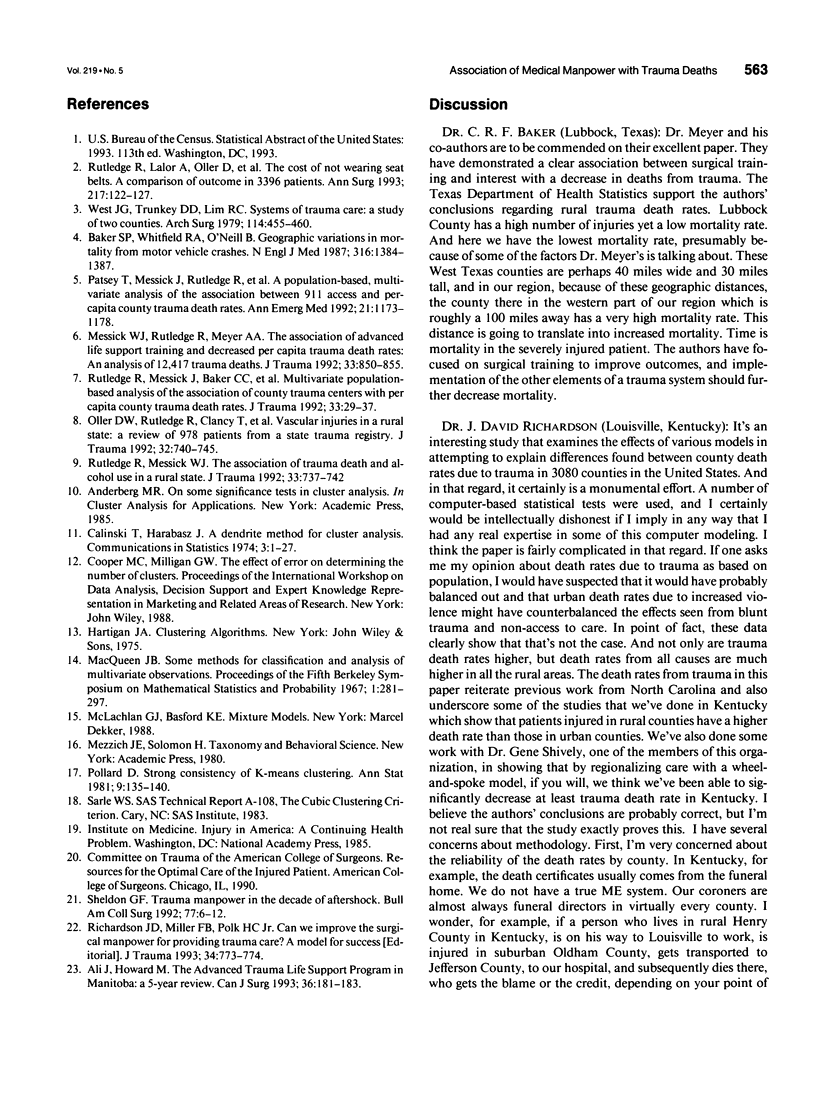

OBJECTIVE: To determine the association between measures of medical manpower available to treat trauma patients and county trauma death rates in the United States. The primary hypothesis was that greater availability of medical manpower to treat trauma injury would be associated with lower trauma death rates. SUMMARY BACKGROUND DATA: When viewed from the standpoint of the number of productive years of life lost, trauma has a greater effect on health care and lost productivity in the United States than any disease. Allocation of health care manpower to treat injuries seems logical, but studies have not been done to determine its efficacy. The effect of medical manpower and hospital resource allocation on the outcome of injury in the United States has not been fully explored or adequately evaluated. METHODS: Data on trauma deaths in the United States were obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics. Data on the number of surgeons and emergency medicine physicians were obtained from the American Hospital Association and the American Medical Association. Data on physicians who have participated in the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Advanced Trauma Life Support Course (ATLS) were obtained from the ACS. Membership information for the American Association for Surgery of Trauma (AAST) was obtained from that organization. Demographic data were obtained from the United States Census Bureau. Multivariate stepwise linear regression and cluster analysis were used to model the county trauma death rates in the United States. The Statistical Analysis System (Cary, NC) for statistical analysis was used. RESULTS: Bivariate and multivariate analyses showed that a variety of medical manpower measures and demographic factors were associated with county trauma death rates in the United States. As in other studies, measures of low population density and high levels of poverty were found to be strongly associated with increased trauma death rates. After accounting for these variables, using multivariate analysis and cluster analysis, an increase in the following medical manpower measures were associated with decreased county trauma death rates: number of board-certified general surgeons, number of board-certified emergency medicine physicians, number of AAST members, and number of ATLS-trained physicians. CONCLUSIONS: This study confirms previous work that showed a strong relation among measures of poverty, rural setting, and increased county trauma death rates. It also found that counties with more board-certified surgeons per capita and with more surgeons with an increased interest (AAST membership) or increased training (ATLS) in trauma care have lower per-capita trauma death rates.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 400 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ali J., Howard M. The Advanced Trauma Life Support Program in Manitoba: a 5-year review. Can J Surg. 1993 Apr;36(2):181–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker S. P., Whitfield R. A., O'Neill B. Geographic variations in mortality from motor vehicle crashes. N Engl J Med. 1987 May 28;316(22):1384–1387. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198705283162206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messick W. J., Rutledge R., Meyer A. A. The association of advanced life support training and decreased per capita trauma death rates: an analysis of 12,417 trauma deaths. J Trauma. 1992 Dec;33(6):850–855. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199212000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oller D. W., Rutledge R., Clancy T., Cunningham P., Thomason M., Meredith W., Moylan J., Baker C. C. Vascular injuries in a rural state: a review of 978 patients from a state trauma registry. J Trauma. 1992 Jun;32(6):740–746. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199206000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patsey T., Messick J., Rutledge R., Meyer A., Butts J. M., Baker C. A population-based, multivariate analysis of the association between 911 access and per-capita county trauma death rates. Ann Emerg Med. 1992 Oct;21(10):1173–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81741-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson J. D., Miller F. B., Polk H. C., Jr Can we improve the surgical manpower for providing trauma care? A model for success. J Trauma. 1993 Jun;34(6):773–774. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199306000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge R., Lalor A., Oller D., Hansen A., Thomason M., Meredith W., Foil M. B., Baker C. The cost of not wearing seat belts. A comparison of outcome in 3396 patients. Ann Surg. 1993 Feb;217(2):122–127. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199302000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge R., Messick J., Baker C. C., Rhyne S., Butts J., Meyer A., Ricketts T. Multivariate population-based analysis of the association of county trauma centers with per capita county trauma death rates. J Trauma. 1992 Jul;33(1):29–38. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge R., Messick W. J. The association of trauma death and alcohol use in a rural state. J Trauma. 1992 Nov;33(5):737–742. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199211000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon G. F. Trauma manpower in the decade of aftershock. Bull Am Coll Surg. 1992 May;77(5):6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West J. G., Trunkey D. D., Lim R. C. Systems of trauma care. A study of two counties. Arch Surg. 1979 Apr;114(4):455–460. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1979.01370280109016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]