Abstract

Amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) is generated by the consecutive cuts of two membrane-bound proteases. β-Secretase cuts at the N terminus of the Aβ domain, whereas γ-secretase mediates the C-terminal cut. Recent evidence suggests that the presenilin (PS) proteins, PS1 and PS2, may be γ-secretases. Because PSs principally exist as high molecular weight protein complexes, biologically active γ-secretases likely require other cofactors such as nicastrin (Nct) for their activities. Here we show that preferentially mature Nct forms a stable complex with PSs. Furthermore, we have down-regulated Nct levels by using a highly specific and efficient RNA interference approach. Very similar to a loss of PS function, down-regulation of Nct levels leads to a massive accumulation of the C-terminal fragments of the β-amyloid precursor protein. In addition, Aβ production was markedly reduced. Strikingly, down-regulation of Nct destabilized PS and strongly lowered levels of the high molecular weight PS1 complex. Interestingly, absence of the PS1 complex in PS1−/− cells was associated with a strong down-regulation of the levels of mature Nct, suggesting that binding to PS is required for trafficking of Nct through the secretory pathway. Based on these findings we conclude that Nct and PS regulate each other and determine γ-secretase function via complex formation.

Amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) is a central player of Alzheimer's disease. After its generation by proteolytic processing (1), the peptide oligomerizes to neurotoxic species that affect long-term potentiation (2). Moreover, familial Alzheimer's disease-associated mutations in three different genes all enhance the relative amount of a longer 42-aa Aβ peptide (Aβ42) (1). Aβ42 preferentially aggregates (3) and is therefore predominantly deposited in amyloid plaques (4).

Aβ is generated by the consecutive action of two proteases, β-secretase and γ-secretase (5). Whereas β-secretase has been identified as a membrane-bound aspartyl protease (6), the identity of γ-secretase is still a matter of ongoing debate (7). Studies with protease inhibitors strongly suggest that γ-secretase is an aspartyl protease (8). At present, the presenilin (PS) proteins, PS1 and PS2, are plausible γ-secretase candidates. Clearly, PSs are required for Aβ production, because a double knockout of PS1 and PS2 (9, 10) and dominant negative mutations of either of the two conserved critical aspartates of PS1 and PS2 block Aβ generation (11–13). A recent, controversial report of continuous Aβ production in the absence of both PSs (14) has not been confirmed (T. Hartmann and B. De Strooper, personal communication). Furthermore, well-characterized γ-secretase inhibitors that mimic the transition state of an aspartyl protease mechansism directly bind to PSs (15, 16). Finally, PSs exhibit considerable homology to one of the active-site aspartates of bacterial polytopic aspartyl proteases (17).

Although both PSs are directly involved in γ-secretase-mediated processing, they likely require additional binding partners for their biological activity (18, 19). This finding is in agreement with the observation that PSs principally exist as high molecular weight (HMW) protein complexes (18, 20–22) and suggests that γ-secretase activity is tightly associated with the PS complex (18). Because PS1 and PS2 do not interact with each other, two distinct HMW PS complexes, a PS1 complex and a PS2 complex, may exist (20, 22, 23). Besides the N-terminal fragment (NTF) and C-terminal fragment (CTF) of PS, other components may be part of these complexes and these components could be involved in the regulation and/or assembly of these protein complexes and their γ-secretase activities.

Indeed, Yu et al. (24) made the pivotal observation that the type I transmembrane glycoprotein nicastrin (Nct) binds to PSs (24). A functional role of Nct as a PS complex component is supported by the observation that deletion of a conserved DYIGS domain of Nct reduces Aβ production (24). However, although reduced Aβ production was observed, the expected increase in the β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) CTFs C99 (generated by β-secretase cleavage) and C83 (generated by α-secretase cleavage), which are the immediate substrates of γ-secretase, could not be detected. This finding is very surprising, because inactivation of γ-secretase activity by several different approaches, such as PS1 and PS1/PS2 knockouts, pharmacological inhibition of γ-secretase, and expression of dominant negative PS mutants, consistently leads to a massive build-up of the APP CTFs (1). Furthermore, deletion of the conserved DYIGS motif showed only a very modest effect on endoproteolysis of Notch at site 3 (S3) (25), another PS-dependent γ-secretase-like cleavage (1). On the other hand, signaling via the Notch pathway was affected by mutations in the Nct gene of Caenorhabditis elegans (24, 26) and Drosophila (27–29). Consistent with reduced Notch signaling, loss of Nct function abolishes S3 cleavage of Notch in Drosophila (27–29). This may be caused by a lack of PS transport to the cell surface (27), because S3 cleavage occurs at the plasma membrane (1). However, surface transport of PS is in clear contrast to the predictions made by the “spatial paradox” (30, 31), which excludes PS from the plasma membrane. An alternative explanation may come from the recent finding that Nct may be required for PS expression or stability (28, 29).

The above-described observations offer four different explanations for Nct function. First, Nct might play a role in cellular trafficking of PS to the cell surface; second, Nct may be involved in the regulation of the stability of the PS complex; third, Nct may affect secretion but not production of Aβ; and fourth, Nct may be required for binding of γ-secretase substrates. To clarify the functional role of Nct we used a highly specific RNA interference (RNAi) approach (32) to inhibit Nct expression in cultured cells. We demonstrate that reduced Nct expression causes a loss of γ-secretase activity as shown by the accumulation of C99 and C83 with concomitant inhibition of Aβ production. Strikingly, the loss of γ-secretase activity upon inhibition of Nct expression was associated with reduced PS1 (and PS2) expression and reduced formation of the PS1 complex, suggesting that Nct is a limiting factor for assembly of PS into the PS complex. Moreover, absence of the PS1 complex in PS1−/− cells was associated with a strong reduction in Nct maturation. Thus, our data surprisingly demonstrate that Nct and PS regulate each other and determine γ-secretase activity via HMW complex formation.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies.

The polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies against the large cytoplasmic loop domains of PS1 (3027; BI.3D7) and PS2 (3711, BI.HF5c) have been described (33). Polyclonal antibodies against the N terminus of PS1 (2953) (34) and PS2 (2972) (35) and the mAb against the N terminus of PS1 (PS1N) have been described (36). The mAb BI.5D3 was raised against a fusion protein containing the PS2 N terminus (amino acids 2–87). Antibodies against the C terminus of APP (6687) (17) and against Aβ1–42 (3926) (37) have been described. Polyclonal antibodies against the C terminus of Nct were obtained from Affinity BioReagents, Neshanic Station, NJ (PA1–758, to residues 688–708) and Sigma (Nct-C, to residues 693–709).

Cell Culture, Cell Lines, and Transfection.

Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK 293) stably expressing expressing Swedish mutant APP (swAPP) (38) were cultured as described (17). Immortalized mouse embryonic fibroblast cells derived from PS1+/+ or PS1−/− mice were cultured as described for HEK 293 cells. To down-regulate expression of endogenous target genes, small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) directed to AAN(19)TT target sequences (32) were used. SiRNA duplex Nct-1045 to down-regulate Nct expression was directed to the target sequence 5′-AAGGGCAAGTTTCCCGTGCAGTT-3′ of the Nct cDNA. The siRNA duplex to lamin A/C used as control has been described (32). siRNA duplexes were transfected by using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen) as described (32) according to the supplier's instructions. To down-regulate Nct expression, cells were transfected with siRNA duplex Nct-1045, split when appropriate, and analyzed after 2–6 days. In case of consecutive transfections with siRNA duplex Nct-1045, cells were split 3 days after the initial transfection and then retransfected.

Analysis of APP, PSs, and Nct.

APP, APP CTFs C99 and C83, and secreted Aβ and APPs species were analyzed as described (17). Analysis of PSs has been described (33), and Nct was analyzed by immunoblotting with antibody PA1–758 or combined immunoprecipitation/immunoblotting with antibody Nct-C. Coimmunopreciptations were performed according to previously published procedures (20).

Detergent Solubilization of PS Complexes.

PS complexes were isolated from membrane preparations of HEK 293 cells or mouse embryonic fibroblast cells by detergent solubilization with 0.5% n-dodecyl β-d-maltoside (DDM), which appeared to be more compatible with blue native PAGE (BN-PAGE) (see below) than 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) and 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-2-hydroxy-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPSO) used previously (18, 20). To enrich PS complexes, membranes were pre-extracted with 2% Brij 35.

BN-PAGE.

DDM-solubilized membrane fractions were subjected to BN-PAGE essentially as described (39). Marker proteins used in BN-PAGE were BSA, 66 kDa; β-amylase, 200 kDa; apoferritin, 443 kDa; and thyroglobulin, 669 kDa (Sigma). After electrophoresis, Western blotting was performed and protein complexes were analyzed by immunoblotting with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham Pharmacia).

Enzymatic Deglycosylation.

Cell lysates were treated with endoglycosidase H (endo H) and N-glycosidase F after immunoprecipitation as described (40). DDM-solubilized membrane fractions were treated with endo H according to the supplier's instruction (Roche Molecular Biochemicals).

Results

PSs Bind Preferentially Mature Nct.

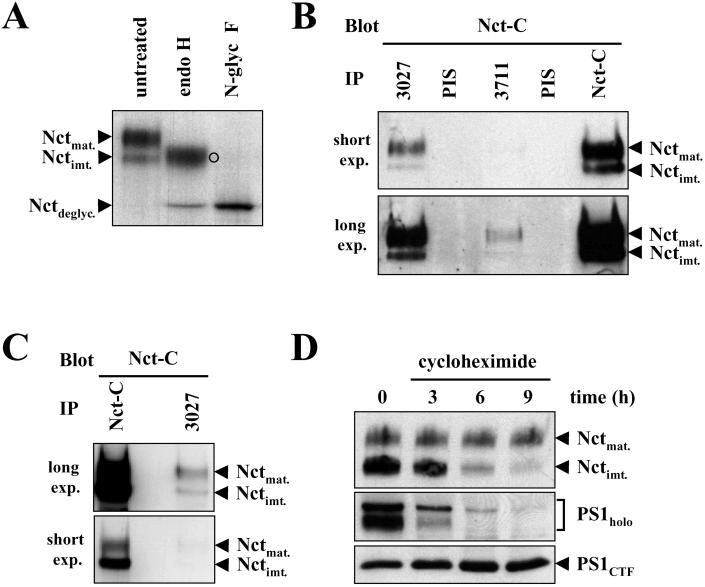

To investigate the functional role of the PS binding protein Nct in γ-secretase activity, we first analyzed its expression in HEK 293 cells stably expressing swAPP. Endogenous Nct occurs in a higher (≈120 kDa) and to minor extent also in a lower molecular mass (≈110 kDa) form (Fig. 1A). Treatment of cell lystates with endo H revealed that the upper band is not shifted to the native molecular mass (≈80 kDa) as observed upon N-glycosidase F treatment. The molecular mass shift of mature Nct upon endo H treatment may thus be caused by incomplete maturation of at least one of the multiple sugar side chains (24). Because at least some sugar side chains undergo complex glycosylation, trafficking of Nct to a late secretory compartment must occur. Therefore, these data demonstrate that the higher molecular form represents mature Nct, whereas the lower molecular form represents immature Nct.

Figure 1.

PS1 preferentially binds mature Nct. (A) Cell lysates of HEK 293 cells stably expressing swAPP were immunoprecipitated with antibody Nct-C, and the immunoprecipitates were treated with or without endo H or N-glycosidase F and analyzed for Nct species by immunoblotting with antibody Nct-C. ○, Partially endo H-digested Nct (compare Fig. 4 B and C). (B) Membrane fractions of HEK 293 cells stably expressing swAPP were solubilized with 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) and analyzed for PS1/Nct, PS2/Nct interactions by immunoprecipitation (IP) with antibodies 3027 and 3711 and immunoblotting with antibody Nct-C. Note that antibody 3711 coimmunoprecipitated lower levels of Nct consistent with the low expression levels of PS2. As a negative control the corresponding preimmunesera (PIS) were used. (C) Membrane fractions of HEK 293 cells stably coexpressing swAPP and Nct were solubilized with CHAPS and analyzed for PS/Nct interactions as in B. Note that PS1 preferentially binds to mature Nct. (D) HEK 293 cells stably coexpressing swAPP, wild-type PS1, and wild-type Nct were treated with cycloheximide (100 μg/ml) for the indicated time points. Cell lysates were analyzed for mature and immature Nct by immunoblotting with antibody PA1–758 and for PS1 holoprotein and the PS1 CTF by combined immunoprecipitation/immunoblotting with antibodies 3027/BI.3D7.

We next investigated complex formation between Nct and either PS1 or PS2. 3-[(3-Cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS)-solubilized membrane fractions from HEK 293 cells stably expressing swAPP were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation analysis. High levels of mature and lower levels of immature Nct species were coimmunoprecipitated with a PS1 C-terminal antibody (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, small amounts of mature and immature Nct were also immunoprecipitated with a PS2 C-terminal antibody (Fig. 1B). Finally, we analyzed complex formation of PS and Nct in HEK 293 stably coexpressing swAPP and Nct. Overexpression of Nct led to a strong increase of immature Nct (Fig. 1C). Under these conditions mature Nct was preferentially coimmunoprecipitated with PS1 and PS2, although the immature species is by far the most abundant Nct form upon overexpression (Fig. 1C). Taken together, these data demonstrate that PS preferentially forms complexes with mature Nct and indicate that assembly of Nct into the PS complex may be limited. However, binding to immature Nct also occurred under both conditions, which may suggest complex formation of PS and Nct in early compartments of the secretory pathway (see also below).

Because PSs assembled into HMW complexes are rather stable over a long time period (41, 42) a similar stability is expected for mature Nct, as a bona fide PS complex component. We therefore next investigated the stability of Nct in the absence of de novo protein synthesis. Cycloheximide treatment of cells overexpressing Nct and wild-type PS1 indicated that immature Nct was rapidly degraded whereas the mature Nct was rather stable (Fig. 1D). Consistent with previous results, the PS1 holoprotein was also rapidly degraded whereas the PS1 CTF was stable (41, 42). Similar results were observed for the stability of immature and mature Nct in untransfected cells (data not shown). These data may therefore indicate that binding of PS to Nct leads to the accumulation of a stable protein complex composed of mature Nct and PS fragments.

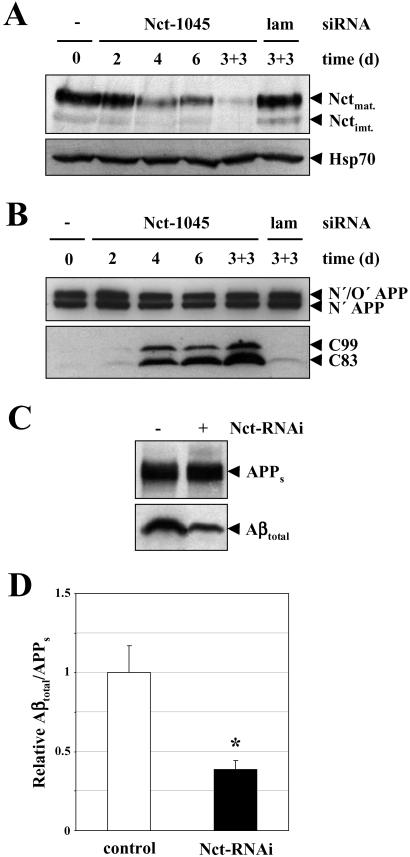

Reduction of Endogenous Nct Levels Affects Aβ Production.

The functional role of Nct in Aβ production can best be assessed by decreasing Nct levels. Because no Nct knockout in vertebrates is currently available, we made use of the highly specific RNAi (43) to inhibit Nct expression in cultured cells (32). HEK 293 cells stably expressing swAPP were transfected with the siRNA duplex Nct-1045 to down-regulate Nct. Cell lysates were prepared 2–6 days after one or two consecutive transfections and analyzed for levels of Nct. In untransfected control cells mature and immature Nct species were detected (Fig. 2A). Transfection with the siRNA duplex Nct-1045 severely reduced Nct expression in a time-dependent manner. In fact, 6 days after the initial transfection very little Nct expression was observed (Fig. 2A). The strongest down-regulation of Nct expression was observed after two consecutive transfections (Fig. 2A). Transfection with the unrelated siRNA duplex to lamin A/C did not have any effect on Nct expression (Fig. 2A). Down-regulation of Nct with siRNA Nct-1045 was specific because expression of Hsp70 was not affected (Fig. 2A). To investigate whether Nct affects Aβ production directly via the γ-secretase activity or indirectly via inhibition of Aβ secretion, we next analyzed samples from above for the levels of APP and its CTFs C99 and C83. If only secretion of Aβ would be affected no accumulation of C99 and C83, the immediate γ-secretase substrates, should be observed. In contrast, a direct inhibition of Aβ production is expected to be accompanied by a massive build-up of C99 and C83 (1). Inhibition of Nct expression by RNAi with siRNA duplex Nct-1045 caused a strong time-dependent accumulation of C99 and C83 fragments without affecting the levels of the APP holoprotein (Fig. 2B). Thus, these data strongly suggest that Nct plays a direct role in the proteolytic generation of Aβ. To prove this, HEK 293 cells stably expressing swAPP were treated with or without siRNA duplex Nct-1045. After metabolic labeling, conditioned media were analyzed for levels of secreted Aβ and soluble APP species. Down-regulation of Nct expression by RNAi markedly reduced the production of Aβ but not the secretion of soluble APP (APPs) species derived from ectodomain shedding by β-secretase and α-secretase (Fig. 2C). Quantitation demonstrated that Aβtotal (Aβ40 and Aβ42) was reduced by ≈60% (P < 0.01, Fig. 2D and data not shown).

Figure 2.

Inhibition of Nct expression by RNAi causes a loss of γ-secretase function. (A) (Upper) HEK 293 cells stably expressing swAPP were subjected to single transfections for 2–6 days or to two consecutive transfections (that were repeated 3 days after the initial transfection; 3 + 3) with the siRNA duplexes Nct-1045 or lamin A/C (lam). After the indicated time, cell lysates were prepared and analyzed for Nct by immunoblotting using antibody PA1–758. Note that transfection with Nct-1045 siRNA duplex results in a strong time-dependent reduction of Nct expression, whereas transfection with lamin A/C siRNA duplex has no effect on Nct expression. (Lower) As a control, aliquots of lysates from above were analyzed for levels of Hsp70. (B) Aliquots of lysates from above were analyzed for APP endoproteolysis. Full-length APP and APP-CTFs C99 and C83 were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibody 6687. Note the strong time-dependent accumulation of C99 and C83 in cells treated with the Nct-1045 siRNA duplex. (C) HEK 293 cells stably expressing swAPP were subjected to two consecutive transfections with siRNA duplex Nct-1045 as described in A. After metabolic labeling, conditioned media were analyzed for levels of Aβtotal by immunoprecipitation with antibody 3926 and for APPs by immunoprecipitation with antibody 5313. Note that inhibition of Nct expression by RNAi causes a marked reduction in secreted Aβtotal but not in the secretion of APPs species. (D) Aβtotal and APPs were analyzed as in C and quantified by phosphorimaging. Normalized levels of Aβtotal/APPs are expressed relative to those in untreated control cells. Bars represent the mean ± SE of three independent experiments. * indicates the significance (Student's t test) relative to the control (*, P < 0.01).

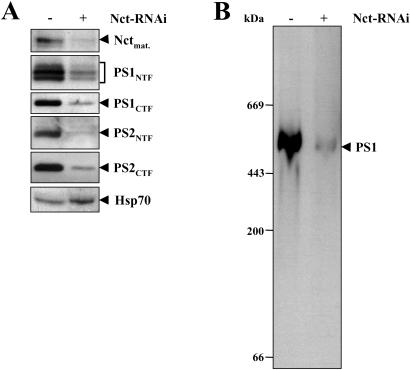

Reduced Assembly of the PS1 Complex in the Absence of Nct.

The results shown above demonstrate that inhibition of Nct expression results in the same biochemical phenotype as observed in the PS1 and PS1/PS2 knockouts, upon γ-secretase inhibition via specific inhibitors, or upon mutagenesis of the critical aspartates in PSs (1). We therefore investigated whether Nct is required for PS expression and formation of PS complexes. Lysates from cells treated with or without siRNA duplex Nct-1045 were analyzed for levels of the PS1 CTF and NTF. Strikingly, down-regulation of Nct expression by RNAi was associated with a significant reduction of the levels of both PS1 and PS2 fragments (Fig. 3A). This finding may indicate that the PS fragments were destabilized because of the lack of their binding partner Nct. Consequently, inhibition of Nct expression should result in a significant reduction of PS complexes. Protein complexes were isolated from cells treated with or without siRNA duplex Nct-1045 by extraction of membrane fractions with DDM, separated by BN-PAGE (39) that allows the analysis of native membrane protein complexes, and analyzed for the PS1 complex. DDM solubilized PSs without disrupting PS NTF/CTF and PS/Nct interactions (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 3B, a HMW PS1 complex was observed that apparently migrated at about 500–600 kDa under the native gel electrophoresis conditions used. Strikingly, upon lowering Nct expression by RNAi a strong reduction of the PS1 complex was observed. These data therefore indicate that Nct may be required for the assembly and stabilization of PS complexes.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of Nct expression by RNAi causes a loss of PS expression and inhibits formation of the PS1 complex. (A) HEK 293 cells stably expressing swAPP were subjected to two consecutive transfections with siRNA duplex Nct-1045 as described in Fig. 2A. Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed for levels of PS1 NTF and CTF by combined immunoprecipitation/immunoblotting with antibodies 2953/PS1N and antibodies 3027/BI.3D7. Levels of PS2 NTF and CTF were analyzed by combined immunoprecipitation/immunoblotting with antibodies 2972/BI.5D3 and antibodies 3711/BI.HF5c. Down-regulation of Nct expression was confirmed by immunoblotting with antibody PA1–758. (B) HEK 293 cells stably expressing swAPP were subjected to Nct RNAi as in A. Membrane fractions were solubilized with DDM, subjected to BN-PAGE, and analyzed for the PS1 complex by immunoblotting with antibody PS1N to PS1.

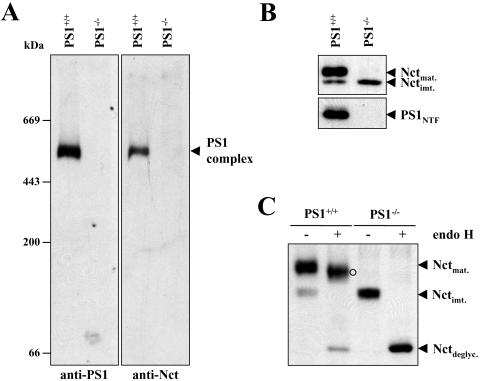

Absence of the PS1 Complex Is Associated with Reduced Nct Maturation.

Because loss of Nct affected PS levels and PS1 complex formation, we next investigated Nct expression and HMW complex formation in the presence or absence of PS1. DDM-solubilized membrane fractions from PS1+/+ and PS1−/− mouse embryonic fibroblast cells were separated by BN-PAGE and analyzed for formation of the PS1 complex. As expected, a PS1 complex that apparently contained Nct and that was of similar molecular mass as the PS1 complex in HEK 293 cells was observed in PS1+/+ cells but not in PS1−/− cells (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, lower molecular weight Nct-containing complexes of similar abundance as the HMW Nct-containing PS1 complex in PS1+/+ cells were not observed under these conditions in PS1−/− cells (Fig. 4A). This finding may suggest that Nct levels are regulated by PSs. We therefore analyzed Nct under denaturing conditions. Surprisingly, analysis of DDM-solubilized membrane fractions by SDS/PAGE revealed that the absence of PS1 inhibited maturation of Nct (Fig. 4B). Nct appeared predominantly as an immature low molecular weight species in PS1−/− cells, suggesting reduced maturation within the secretory pathway. In contrast to mature Nct, the low molecular weight species was fully endo H-sensitive, demonstrating that it represents immature N-glycosylated Nct (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these data demonstrate that absence of the PS1 complex in PS1−/− cells is associated with a defect in maturation of Nct.

Figure 4.

Absence of PS1 complex formation in PS1−/− cells is associated with significantly reduced maturation of Nct. (A) Membrane fractions from PS1+/+ or PS1−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts were solubilized with DDM, subjected to BN-PAGE, and analyzed for the PS1 complex by immunoblotting with antibodies to PA1–758 and 2953. Note that under these conditions Nct monomers were not detected. (B) Aliquots of DDM-solubilized membrane fractions from A were subjected to SDS/PAGE and analyzed for Nct by immunoblotting with antibody PA1–758. Note the strongly reduced levels of mature Nct in PS1−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts. (C) Aliquots of DDM-solubilized membrane fractions from A were subjected to endo H treatment and analyzed for Nct as in B. ○, Partially endo H-digested Nct.

Discussion

Although Nct has been implicated to be involved in intramembrane proteolysis (44), very little is known about the function of Nct in Aβ generation. Mutagenesis of a conserved DYIGS motif indicated that a loss of Nct function does not directly affect the proteolytic activity of γ-secretase because the immediate substrates of γ-secretase cleavage, the APP CTFs, did not accumulate (24). This result together with the very limited effect of these mutants on Notch endoproteolysis (25) indicated that Nct may be indirectly involved in processing of Notch and APP. However, our data now provide clear evidence that Nct is directly involved in the proteolytic generation of Aβ generation via formation of the PS1 complex. RNAi-mediated down-regulation of Nct expression causes a similar accumulation of APP CTFs and significantly reduced Aβ production as observed in the PS1 knockout, upon mutagenesis of the critical PS aspartates, or with γ-secretase inhibitors (1). Thus, a gene knockout of Nct is expected to cause not only a full Notch-deficient phenotype but also a complete loss of Aβ production as observed upon deletion of PS1/PS2 (9, 10). An essential role of Nct in PS-mediated γ-secretase cleavage is further supported by the demonstration that Nct copurifies with γ-secretase activity (19). This result is in agreement with our finding that PS and Nct both are required for the assembly of a functional HMW PS1 complex complex (see below). Under conditions of BN-PAGE, the PS1 HMW complex was consistently found at 500–600 kDa. The molecular mass of the PS1 complex observed in previous studies (20, 22) as well as in this study is substantially lower than that of the PS1 complex observed by Li et al. (18). This extremely high molecular mass (2,000 kDa) may be caused by multimerization during gel filtration. However, we cannot rule out the existence of PS1 complexes with higher molecular mass, although these were not observed under our experimental conditions.

As expected for a bona fide PS complex component, we observed that mature Nct is rather stable over a long time period as has also been observed for PSs (41, 42). In addition, we show that PSs bind predominantly mature Nct. The latter finding is in apparent conflict with the spatial paradox (30, 31), a phenomenon that claims that PSs are exclusively localized in the early compartments of the secretory pathway, i.e., in the endoplasmic reticulum, the intermediate compartment, and the early Golgi. According to the spatial paradox, PS may be a trafficking factor for γ-secretase rather than γ-secretase itself, because very little γ-secretase activity is observed in early compartments. However, small amounts of PSs may also be located in post-Golgi compartments and on the cell surface (45, 46). Clearly, the demonstration that PS predominantly binds mature Nct additionally questions the existence of the spatial paradox. Moreover, because PS1 coimmunoprecipitates with cell surface-labeled Nct (C. Kaether and C.H., unpublished results), it is very likely that a biologically active PS1 complex is located on the plasma membrane.

How may Nct influence γ-secretase activity? Based on our results we propose that Nct provides an essential scaffold for the assembly and transport of the PS complex. If Nct is missing PS is destabilized, less PS complex is formed and consequently γ-secretase activity is reduced. This finding is also supported by similar findings in Drosophila (27–29). On the other hand, in the absence of PS1 maturation of Nct to the complex glycosylated endo H-resistant Nct species is strongly reduced, suggesting a severe reduction of its trafficking through the secretory pathway. This finding implies that PS, Nct, and presumably other components of the PS complex (47) assemble in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) before they undergo further trafficking and maturation through the secretory pathway. The finding that small amounts of immature Nct coimmunoprecipitate with PSs supports an early complex assembly in the ER. A requirement of PS for the maturation/trafficking of Nct is also supported by recent data in C. elegans, where a sel-12/hop-1 deficiency affects the cell surface localization of aph-2, the C. elegans Nct homologue (47). Taken together, these results suggest that a PS/Nct-containing complex is released from the ER only after full assembly. Based on these data, we propose a dual function model for PS in trafficking and intramembrane proteolysis. PS is required for the maturation of Nct (and probably other PS complex components as well) probably as guidance protein of the PS complex through the secretory pathway. In addition, PS contributes the catalytic moiety for γ-secretase activity. The catalytic function may indeed be mediated by the two active-site aspartate residues within PSs as suggested previously (11). Importantly, the observation that mutagenesis of an PS active-site aspartate residue does not affect Nct binding (24) although it abolishes Aβ production is in support of a dual function of PSs.

The observation that formation of a functional PS complex requires the presence of Nct may also suggest that Nct is implicated in the “replacement” phenomenon. It is well known that because of a limiting PS binding factor, PSs cannot be overexpressed and transfection of ectopic PS simply results in the expression of the ectopic PS variant to the expense of endogenous PS (48, 49). Nct may be such a limiting factor whose expression levels may determine PS levels. However, even if so, Nct may not be the only limiting factor and additional PS complex components may be required to allow the efficient assembly of a functional PS complex. Such an additional factor may be aph-1, which is not only involved in Notch signaling but also in cell surface localization of Nct (47).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Gang Yu and Peter St. George-Hyslop for the Nct cDNA, Drs. Bart De Strooper and Paul Saftig for PS1+/+ and PS1−/− mouse embryonic fibroblast cells, Drs. Marcus Kostka and Cornelia Doerner-Ciossek for mAb BI.5D3, Dr. Ralph Nixon for mAb PS1N, Dr. Franz-Ulrich Hartl for the antibody against Hsp70, Dr. Dorit Zharhary (Sigma) for antibody Nct-C, and Anja Capell and Regina Fluhrer for helpful discussion. This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the European Union (DIADEM Project).

Abbreviations

- Aβ

amyloid β-peptide

- APP

β-amyloid precursor protein

- BN-PAGE

blue native PAGE

- CTF

C-terminal fragment

- DDM

n-dodecyl β-d-maltoside

- endo H

endoglycosidase H

- HEK 293

human embryonic kidney 293

- HMW

high molecular weight

- Nct

nicastrin

- NTF

N-terminal fragment

- PS

presenilin

- RNAi

RNA interference

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- swAPP

Swedish mutant APP

References

- 1.Steiner H, Haass C. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:217–224. doi: 10.1038/35043065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh D M, Klyubin I, Fadeeva J V, Cullen W K, Anwyl R, Wolfe M S, Rowan M J, Selkoe D J. Nature (London) 2002;416:535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jarrett J T, Berger E P, Lansbury P T., Jr Biochemistry. 1993;32:4693–4697. doi: 10.1021/bi00069a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwatsubo T, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Mizusawa H, Nukina N, Ihara Y. Neuron. 1994;13:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walter J, Kaether C, Steiner H, Haass C. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:585–590. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00253-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vassar R, Citron M. Neuron. 2000;27:419–422. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Strooper B, Annaert W. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:E221–E225. doi: 10.1038/ncb1001-e221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolfe M S, Xia W, Moore C L, Leatherwood D D, Ostaszewski B, Rahmati T, Donkor I O, Selkoe D J. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4720–4727. doi: 10.1021/bi982562p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herreman A, Serneels L, Annaert W, Collen D, Schoonjans L, De Strooper B. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:461–462. doi: 10.1038/35017105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Z, Nadeau P, Song W, Donoviel D, Yuan M, Bernstein A, Yankner B A. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:463–465. doi: 10.1038/35017108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolfe M S, Xia W, Ostaszewski B L, Diehl T S, Kimberly W T, Selkoe D J. Nature (London) 1999;398:513–517. doi: 10.1038/19077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steiner H, Duff K, Capell A, Romig H, Grim M G, Lincoln S, Hardy J, Yu X, Picciano M, Fechteler K, et al. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28669–28673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimberly W T, Xia W, Rahmati T, Wolfe M S, Selkoe D J. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3173–3178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armogida M, Petit A, Vincent B, Scarzello S, da Costa C A, Checler F. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:1030–1033. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esler W P, Kimberly W T, Ostaszewski B L, Diehl T S, Moore C L, Tsai J-Y, Rahmati T, Xia W, Selkoe D J, Wolfe M S. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:428–433. doi: 10.1038/35017062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y M, Xu M, Lai M T, Huang Q, Castro J L, DiMuzio-Mower J, Harrison T, Lellis C, Nadin A, Neduvelli J G, et al. Nature (London) 2000;405:689–694. doi: 10.1038/35015085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steiner H, Kostka M, Romig H, Basset G, Pesold B, Hardy J, Capell A, Meyn L, Grim M G, Baumeister R, et al. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:848–851. doi: 10.1038/35041097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y M, Lai M T, Xu M, Huang Q, DiMuzio-Mower J, Sardana M K, Shi X P, Yin K C, Shafer J A, Gardell S J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6138–6143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110126897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esler W P, Kimberly W T, Ostaszewski B L, Ye W, Diehl T S, Selkoe D J, Wolfe M S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2720–2725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052436599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Capell A, Grunberg J, Pesold B, Diehlmann A, Citron M, Nixon R, Beyreuther K, Selkoe D J, Haass C. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3205–3211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seeger M, Nordstedt C, Petanceska S, Kovacs D M, Gouras G K, Hahne S, Fraser P, Levesque L, Czernik A J, George-Hyslop P S, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5090–5094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu G, Chen F, Levesque G, Nishimura M, Zhang D M, Levesque L, Rogaeva E, Xu D, Liang Y, Duthie M, et al. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16470–16475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saura C A, Tomita T, Davenport F, Harris C L, Iwatsubo T, Thinakaran G. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13818–13823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.13818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu G, Nishimura M, Arawaka S, Levitan D, Zhang L, Tandon A, Song Y Q, Rogaeva E, Chen F, Kawarai T, et al. Nature (London) 2000;407:48–54. doi: 10.1038/35024009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen F, Yu G, Arawaka S, Nishimura M, Kawarai T, Yu H, Tandon A, Supala A, Song Y Q, Rogaeva E, et al. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:751–754. doi: 10.1038/35087069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goutte C, Hepler W, Mickey K M, Priess J R. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2000;127:2481–2492. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.11.2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung H-M, Struhl G. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:1129–1132. doi: 10.1038/ncb1201-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu Y, Ye Y, Fortini M E. Dev Cell. 2002;2:69–78. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez-Schier H, Johnston D S. Dev Cell. 2002;2:79–89. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Annaert W G, Levesque L, Craessaerts K, Dierinck I, Snellings G, Westaway D, George-Hyslop P S, Cordell B, Fraser P, De Strooper B. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:277–294. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.2.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cupers P, Bentahir M, Craessaerts K, Orlans I, Vanderstichele H, Saftig P, De Strooper B, Annaert W. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:731–740. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elbashir S M, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, Yalcin A, Weber K, Tuschl T. Nature (London) 2001;411:494–498. doi: 10.1038/35078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steiner H, Romig H, Grim M G, Philipp U, Pesold B, Citron M, Baumeister R, Haass C. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7615–7618. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walter J, Grunberg J, Capell A, Pesold B, Schindzielorz A, Citron M, Mendla K, George-Hyslop P S, Multhaup G, Selkoe D J, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5349–5354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomita T, Maruyama K, Saido T C, Kume H, Shinozaki K, Tokuhiro S, Capell A, Walter J, Grunberg J, Haass C, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2025–2030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Capell A, Saffrich R, Olivo J C, Meyn L, Walter J, Grunberg J, Mathews P, Nixon R, Dotti C, Haass C. J Neurochem. 1997;69:2432–2440. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69062432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wild-Bode C, Yamazaki T, Capell A, Leimer U, Steiner H, Ihara Y, Haass C. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16085–16088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Citron M, Oltersdorf T, Haass C, McConlogue L, Hung A Y, Seubert P, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Lieberburg I, Selkoe D J. Nature (London) 1992;360:672–674. doi: 10.1038/360672a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schagger H, von Jagow G. Anal Biochem. 1991;199:223–231. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90094-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Capell A, Steiner H, Willem M, Kaiser H, Meyer C, Walter J, Lammich S, Multhaup G, Haass C. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30849–30854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ratovitski T, Slunt H H, Thinakaran G, Price D L, Sisodia S S, Borchelt D R. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24536–24541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steiner H, Capell A, Pesold B, Citron M, Kloetzel P M, Selkoe D J, Romig H, Mendla K, Haass C. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32322–32331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hammond S M, Caudy A A, Hannon G J. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:110–119. doi: 10.1038/35052556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kopan R, Goate A. Neuron. 2002;33:321–324. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00585-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lah J J, Levey A I. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;16:111–126. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ray W J, Yao M, Mumm J, Schroeter E H, Saftig P, Wolfe M, Selkoe D J, Kopan R, Goate A M. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36801–36807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goutte C, Tsunozaki M, Hale V A, Priess J R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:775–779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022523499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thinakaran G, Borchelt D R, Lee M K, Slunt H H, Spitzer L, Kim G, Ratovitsky T, Davenport F, Nordstedt C, Seeger M, et al. Neuron. 1996;17:181–190. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80291-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thinakaran G, Harris C L, Ratovitski T, Davenport F, Slunt H H, Price D L, Borchelt D R, Sisodia S S. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28415–28422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]