Abstract

Introduction

Burnout among clinicians can jeopardize their well-being, productivity, and quality of patient care. However, research on burnout of physician assistants/associates (PAs) is limited. This study investigates factors associated with burnout among PAs.

Methods

Using the Conservation of Resources theory as a framework and robust national data (N = 122 360), we examined factors associated with PA burnout. Analyses included descriptives, bivariate statistics, and multivariate logistic regression with marginal effects.

Results

A third (34.2%) reported experiencing at least one symptom of burnout; however, differences by specialty were observed, with emergency medicine PAs having the highest prevalence (42.2%) while dermatology PAs had the lowest (26.1%). Multivariate analysis revealed that the strongest factor associated with a 19.9 percentage point higher probability of burnout was a perceived decline in the quality of working conditions in the past year. PAs in emergency medicine were more likely than PAs in other specialties to report worsening conditions. Other factors associated with increased burnout included workload, understaffing, and educational debt.

Conclusion

The declining quality of working conditions among PAs was the strongest factor associated with increased burnout, while satisfaction with work-life balance was protective. Strategies and policies focusing on maintaining quality working environments to reduce burnout risk should be prioritized.

Keywords: burnout, Conservation of Resources theory, healthcare workforce, physician assistants, physician associates

Key points.

Over a third of physician assistants/associates (PAs) (34.2%) indicated at least one symptom of burnout, with the highest prevalence among PAs in emergency medicine.

The highest probability of burnout was reported among PAs who perceived a decline in the quality of working conditions in the past year.

Satisfaction with work-life balance emerged as the strongest factor associated with reduced probability of burnout among PAs.

Introduction

Burnout among healthcare providers (HCPs) threatens their well-being, productivity, and the delivery of high-quality patient care.1 Maslach and Jackson's work in 1981 identified 3 domains of burnout: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment.1,2 Research shows that emotional exhaustion is most often associated with adverse outcomes compared to depersonalization and personal accomplishment.3 The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated burnout, and this syndrome has become a global health workforce crisis with far-reaching consequences.2,4

Prevalence of burnout in HCPs

Burnout has been studied across occupations, with research indicating a higher prevalence among HCPs.5,6 A systematic review that included 182 studies with 109 628 physicians found an overall burnout prevalence of 67%, though this varied across studies.7 Prasad et al. found a combined prevalence of 47.7% among 1055 advanced practice providers (APPs), encompassing physician assistants/associates (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs).8 Other studies indicated burnout rates for NPs at approximately 25% in primary care settings9 and 31.3% among hematology/oncology NPs.10 The 2018 American Academy of PAs (AAPA) report revealed that across all specialties, 28.5% experienced burnout, with the highest rate of 34.5% reported among PAs in emergency medicine.11 A 2021 systematic review that included 6 studies exploring PA burnout showed that rates varied depending on the study, but concluded that PAs experience burnout similar to that of other providers.12

Adverse outcomes associated with burnout among HCPs

Williams et al. conducted a systematic review of the consequences of physician burnout.3 Their results showed that overall burnout (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment) was associated with a range of detrimental outcomes, including decreased engagement, depression and anxiety, substance abuse, declining physical health, and suicidal ideation.3 However, emotional exhaustion was more frequently associated with adverse outcomes compared to depersonalization and reduced personal accomplishment. Other studies have linked burnout with increased medical errors, healthcare-associated infections, malpractice lawsuits, and even patient mortality.5,6,13,14 The heightened risk of medical errors and suboptimal care quality resulting from burnout compromises patient safety.6,13,15,16 Abraham et al. found that burnout in NPs significantly predicted lower perceived quality of care.9 Similarly, Shanafelt et al. reported that medical errors were strongly related to burnout among surgeons.17 However, the relationship between burnout and care quality may be complex. In a study of family physicians, Casalino et al. found that overall, there were no consistent associations between burnout and patient outcomes.18 There were even a few significant results suggesting that physicians reporting occasional or frequent burnout tended to have lower rates of adverse outcomes.18

Risk factors for burnout in HCPs

Poor work environments and inadequate staffing have been consistently and strongly associated with a higher burnout risk.19-23 Research shows that excessive hours worked for a prolonged time can lead to burnout.19 Lin et al. found that, compared to a 40-h work week, the likelihood of burnout in healthcare workers doubled when their hours exceeded 60, tripled when they surpassed 74, and quadrupled when they went beyond 84.24 Jung et al. found that physicians considering reducing their work hours were more likely to be experiencing burnout compared to those who were not.25 One study among PAs found that hours worked in the past 7 days were significantly associated with burnout in bivariate analyses.26 However, this association was not significant in adjusted analyses.

HCPs in different specialties may experience distinct workloads, working conditions, and resource access. For example, the emergency medicine specialty is fast-paced and involves high-acuity patients, and thus can be more demanding than other specialties. In contrast, others, such as dermatology, may offer more predictable working hours and greater control over workload. A systematic review suggests emergency medicine physicians may be more susceptible to burnout than physicians in other specialties.27 Similarly, for PAs, Dyrbye et al. found that those practicing in emergency medicine had higher odds of burnout compared to their peers in other disciplines.26

PAs can transition between different medical and surgical specialties due to their generalist medical education and certification. Research indicates that 76% of PAs change specialties at least once by late career.28 PAs may change for various reasons, including higher income, better benefits, improved work-life balance, professional growth, or skill development. Others may seek to leave a high-stress specialty, leaving one with declining opportunities or unstable employment, or departing a role that no longer provides fulfillment. A study with PAs in Minnesota determined that most viewed the ability to change disciplines as crucial for preventing burnout.29 However, changing specialties also involves learning and adapting to the new discipline. Research suggests that transitioning to a new specialty can be challenging if onboarding and other support are not provided.30

Education-related debt can strain HCPs’ financial resources and contribute to overall resource depletion. Research shows that higher educational debt is associated with an increased risk of burnout among physiatrists, internal medicine residents, and oncology trainees.31-33 One recent study found an association between the amount of education debt accrued and initial specialty choices of early career PAs.34 Qualitative analyses in that study revealed that educational debt was a significant stressor for many PAs, with some choosing non-primary care specialties due to higher incomes to more quickly pay off their loans.34

HCP demographic characteristics have also often been investigated regarding their association with burnout. For example, Meredith et al., in their systematic review, included 73 studies on gender, 53 on age, and 17 on race/ethnicity as predictors of HCP burnout.19 Research suggests that HCPs who are women and younger may be more likely to report burnout, while findings by race and ethnicity are inconsistent.19 Coplan et al. found that female PAs were more likely than male PAs to leave their positions due to stress.35

Research on burnout among PAs has increased over the past decade; however, more studies are needed, particularly with robust national datasets.36,37 The PA profession has experienced rapid growth since 2013 and is projected to further expand by 28% between 2023 and 2033.38,39 Given the profession's vital role in healthcare, it is critically important to better understand factors contributing to PA burnout.

Theoretical framework

The Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, developed by Hobfoll in 1989,40 has gained attention as a practical framework for understanding and predicting burnout among HCPs in the current demanding healthcare environment characterized by high workloads and resource shortages.3,21 COR theory proposes that individuals strive to obtain, retain, and cultivate resources.41 Stress arises when these resources are threatened, lost, or unobtainable despite extended effort.41 Resources are defined as anything perceived to help attain goals; their value is context-dependent, and losses or gains in 1 area can impact others.42,43 Resources can be classified into objects, conditions, personal characteristics, and energies.44 Objects are tangible items that carry functional or symbolic value, such as transportation, shelter, or tools essential for work.42,45 Conditions refer to internal states or external circumstances that facilitate access to or attainment of other resources; examples include stable employment, a supportive work environment, good health, and job seniority.41,43,46,47 Personal characteristics encompass traits and skills such as conscientiousness, adaptability, a sense of mastery, and social or technical skills that enable individuals to manage challenges and engage effectively with their environment.41,43,46,47 Energies are valuable for their capacity to be exchanged for other resources and include physical and mental energy, time, and finances.40,43,48 COR theory emphasizes safeguarding and building diverse resources to manage demands and establish a reserve for future challenges.41 Notably, resource loss has a disproportionately greater impact than resource gain, and resource depletion can trigger a cascading loss spiral.41 Conversely, acquiring 1 resource facilitates obtaining others.41 A diverse array of resources acts as a buffer against burnout, while prolonged depletion or insufficient resources to meet work demands contribute to burnout.43-45,48

COR posits that greater resources are protective against negative outcomes; thus, based on prior findings and COR, we hypothesize that increased condition, personal, and energy resources will be negatively associated with the probability of burnout among PAs.

Methods

This cross-sectional study utilized 2023 data from the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants (NCCPA) PA Professional Profile. This secure online portal collects workforce information from board certified PAs in the US. The NCCPA database includes demographics, professional practice characteristics, and other self-reported measures, including burnout.49 The questions in the PA Professional Profile are voluntary, allowing PAs to update their responses at any time or when logging their continuing medical education credits every 2 years. Out of 178 708 board certified PAs, 149 909 provided or updated their responses within the past 3 years; most (71.1%) did so in 2023 (see figure in the Appendix of participation rates by year and month). Among these, 122 360 (81.6%) responded to the burnout item.

Burnout was the primary outcome variable, reflecting the effects of chronic resource depletion, perceived threats to resources, or insufficient resource gains relative to investment, as described by COR theory. Burnout was assessed using a nonproprietary, validated single-item measure,50,51 which asked: “Overall, based on your definition of burnout, how would you rate your level of burnout?” The responses were rated on a 5-point scale:

I enjoy my work; I have no symptoms of burnout;

Occasionally, I am under stress, and I don't always have as much energy as I once did, but I don't feel burned out;

I am definitely burning out and have one or more symptoms of burnout, such as physical and emotional exhaustion;

The symptoms of burnout that I'm experiencing won't go away. I think about frustration at work a lot;

I feel completely burned out and often wonder if I can go on. I am at the point where I may need some changes or may need to seek some sort of help.

Consistent with previous research, we dichotomized the scale into “no symptoms” (ratings 1 and 2) and “one or more symptoms of burnout” (ratings 3 to 5), which served as a positive screen for burnout.50,51 This single-item measure has previously been used in studies involving physicians, PAs, and NPs50,51 and highly correlates with the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) emotional exhaustion subscale.50 Research shows that emotional exhaustion is most often associated with adverse outcomes compared to the other subscales (depersonalization and personal accomplishment).3

We examined resources (conditions, personal, and energies) according to COR theory. Condition resources were operationalized as changes in the quality of working conditions (improved, no change, and worsened) in the past year, practice settings (hospital, office-based private practice, etc.), and whether the place of employment was recruiting/hiring PAs (Figure 1). Different practice settings were assessed as they may offer distinct availability and access to resources. If the place of employment is actively recruiting/hiring PAs, it may indicate being understaffed. Speaking another language besides English with patients served as a personal resource (a skill that facilitates communication with diverse patient populations). Types of specialties were considered personal resources (acquired specialized knowledge and skills). The ability to change specialties is a personal resource enabled by PAs’ generalist medical education and certification. Energy resources were operationalized as weekly working hours, the proportion of time spent in direct patient care, working after hours (nights and weekends), having a secondary position (clinical or non-clinical), satisfaction with work-life balance, satisfaction with number of hours worked, satisfaction with income, and current educational debt. Demographics (age, gender, race, and ethnicity) were considered contextual factors that may influence resource access, loss, or gain.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of COR theory for burnout among PAs.

We performed bivariate analyses using Pearson's chi-square test to assess the association between each variable and the likelihood of PAs reporting 1 or more symptoms of burnout. We also assessed whether changes in the quality of working conditions varied by practice settings and specialties. Following this, we conducted a multivariate logistic regression52 and used marginal effects to identify mean percentage point differences in the probability of reporting burnout symptoms, incorporating all covariates. Variance inflation factors (VIFs) were assessed to ensure multicollinearity was not a concern in the multivariate logistic model; all VIF values were below 3, confirming the absence of multicollinearity.53 All analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Marginal effects were calculated using the marginal effects R package.54 All statistics were 2-sided; a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Limitations

Our study has several important limitations. First, we used a cross-sectional design and did not assess burnout changes over time, which limits any causal interpretations. A second limitation is that most of the variables included in our study were self-reported, and this is particularly important if particular PA groups were less likely to disclose burnout due to stigma. A third limitation is the instrument we used to assess burnout symptoms, which only captures emotional exhaustion, not depersonalization and personal accomplishment. However, emotional exhaustion has been most often associated with adverse outcomes compared to the other facets.3 The single-item measure we used has demonstrated a high correlation with the emotional exhaustion subscale of the MBI.50 Another limitation is that the PA Profile does not ask follow-up questions regarding the nature of the worsening quality of working conditions. This is critically important to better understand what specific changes in the working environment increase the likelihood of burnout. Lastly, our study is limited by reliance on a secondary dataset. The variables, although relevant, were not specifically tailored to the constructs of COR theory as they would have been if we had designed a questionnaire or used the COR-Evaluation instrument.43 Despite the limitations, the major strengths of our study include using a robust national dataset with PAs practicing across a wide spectrum of specialties and practice settings, a high participation rate of 81.6%, and using COR theory as a framework for understanding burnout among PAs.

Results

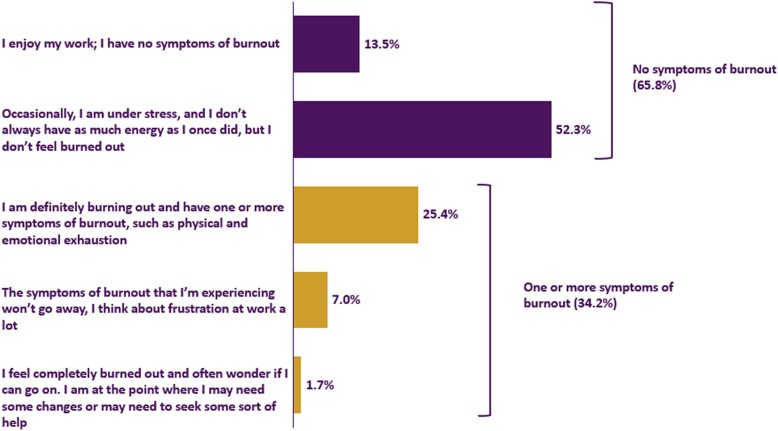

Figure 2 shows that 65.8% of PAs had no burnout symptoms: 13.5% selected “I enjoy my work; I have no symptoms of burnout,” and 52.3% indicated, “Occasionally, I am under stress, and I don't always have as much energy as I once did, but I don't feel burned out.” Over a third (34.2%) reported at least one burnout symptom. Of these, the highest proportion (25.4%) reported, “I am definitely burning out and have one or more symptoms of burnout, such as physical and emotional exhaustion.” Further, 7.0% chose “The symptoms of burnout that I'm experiencing won't go away, I think about frustration at work a lot” as their response. The fewest (1.7%) specified, “I feel completely burned out and often wonder if I can go on. I am at the point where I may need some changes or may need to seek some sort of help.”

Figure 2.

Proportion of PAs reporting burnout symptoms.

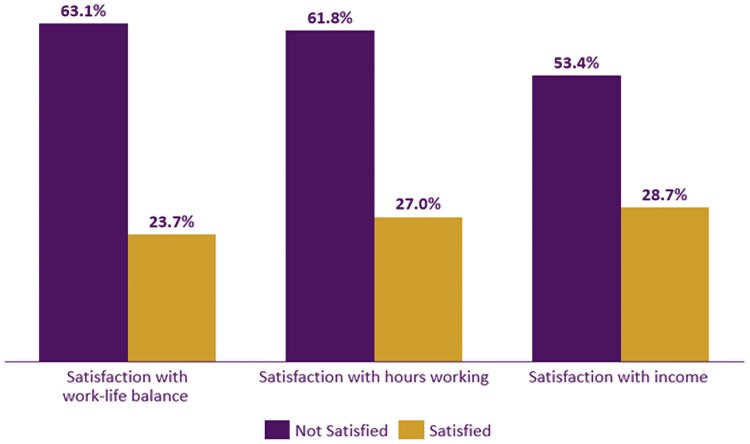

In bivariate analyses, all factors assessed showed significant associations with burnout (all P < 0.001; Table 1). Among the highest and lowest proportions of reporting at least one burnout symptom were PAs not satisfied and satisfied with work-life balance (63.1% vs 23.7%; P < 0.001), hours working (61.8% vs 27.0%; P < 0.001), and income (53.4% vs 28.7%; P < 0.001; Figure 3), respectively.

Table 1.

PA personal and professional characteristics and their association with burnout symptoms.

| No symptoms of burnout n = 80 534 (65.8%) |

One or more symptoms of burnout n = 41 826 (34.2%) |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Less than 35 | 26 875 (66.9%) | 13 293 (33.1%) | P < 0.001 |

| 35-44 | 26 199 (63.2%) | 15 248 (36.8%) | ||

| 45-54 | 15 662 (65.5%) | 8256 (34.5%) | ||

| 55-64 | 8342 (67.5%) | 4010 (32.5%) | ||

| 65+ | 3456 (77.2%) | 1019 (22.8%) | ||

| Gender | Female | 54 570 (63.7%) | 31 046 (36.3%) | P < 0.001 |

| Male | 25 945 (70.7%) | 10 772 (29.3%) | ||

| Race | White | 64 808 (65.6%) | 33 968 (34.4%) | P < 0.001 |

| Asian | 5251 (68.4%) | 2423 (31.6%) | ||

| Black/African American | 2860 (70.6%) | 1189 (29.4%) | ||

| Othera | 4520 (66.5%) | 2275 (33.5%) | ||

| Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic/Latino(a/x) | 72 193 (65.8%) | 37 476 (34.2%) | P < 0.001 |

| Hispanic/Latino(a/x) | 5682 (68.9%) | 2559 (31.1%) | ||

| Speaks another language | No | 60 695 (65.6%) | 31 800 (34.4%) | P < 0.001 |

| Yes | 17 832 (67.1%) | 8752 (32.9%) | ||

| Secondary position | One clinical PA position | 68 465 (66.1%) | 35 067 (33.9%) | P < 0.001 |

| Secondary non-clinical position | 2724 (62.6%) | 1627 (37.4%) | ||

| Two or more clinical PA positions | 8905 (64.5%) | 4902 (35.5%) | ||

| Specialty | Primary care | 17 222 (63.4%) | 9939 (36.6%) | P < 0.001 |

| Surgery—subspecialties | 15 858 (69.4%) | 6983 (30.6%) | ||

| Emergency medicine | 7575 (57.8%) | 5532 (42.2%) | ||

| Internal medicine—subspecialties | 7943 (66.0%) | 4085 (34.0%) | ||

| Dermatology | 3846 (73.9%) | 1357 (26.1%) | ||

| Hospital medicine | 2718 (63.0%) | 1599 (37.0%) | ||

| Surgery—general | 2664 (71.7%) | 1052 (28.3%) | ||

| Psychiatry | 1857 (64.8%) | 1010 (35.2%) | ||

| Critical care medicine | 1505 (61.5%) | 944 (38.5%) | ||

| Other | 18 942 (67.5%) | 9109 (32.5%) | ||

| Changed specialties | Did not change | 34 699 (66.5%) | 17 513 (33.5%) | P < 0.001 |

| Changed | 38 406 (65.3%) | 20 423 (34.7%) | ||

| Practice setting | Office-based private practice | 31 128 (68.9%) | 14 081 (31.1%) | P < 0.001 |

| Hospital | 32 370 (64.0%) | 18 200 (36.0%) | ||

| Urgent care | 4284 (60.5%) | 2794 (39.5%) | ||

| Federal government | 3613 (65.0%) | 1943 (35.0%) | ||

| Other | 8722 (65.5%) | 4588 (34.5%) | ||

| Quality of working conditions | No change | 38 421 (75.4%) | 12 548 (24.6%) | P < 0.001 |

| Worsened | 18 626 (47.6%) | 20 519 (52.4%) | ||

| Improved | 10 490 (78.5%) | 2865 (21.5%) | ||

| Direct patient care | <25% | 1775 (63.8%) | 1009 (36.2%) | P < 0.001 |

| 25%-50% | 12 333 (63.3%) | 7147 (36.7%) | ||

| 51%-75% | 23 996 (64.9%) | 12 957 (35.1%) | ||

| >75% | 41 437 (67.1%) | 20 278 (32.9%) | ||

| Hours working | 30 or fewer hours | 11 874 (72.5%) | 4493 (27.5%) | P < 0.001 |

| 31-40 | 47 558 (67.5%) | 22 862 (32.5%) | ||

| 41-50 | 16 766 (60.9%) | 10 771 (39.1%) | ||

| More than 50 h | 3937 (53.0%) | 3485 (47.0%) | ||

| Working after hours | No | 35 736 (68.1%) | 16 711 (31.9%) | P < 0.001 |

| Yes | 37 088 (63.8%) | 21 019 (36.2%) | ||

| Place of employment currently hiring PAs | No | 47 273 (69.6%) | 20 677 (30.4%) | P < 0.001 |

| Yes | 28 948 (60.3%) | 19 046 (39.7%) | ||

| Not sure | 3860 (67.6%) | 1853 (32.4%) | ||

| Current educational debt | No educational debt | 31 303 (67.9%) | 14 815 (32.1%) | P < 0.001 |

| Less than $50 000 | 8054 (65.7%) | 4206 (34.3%) | ||

| $50 000-$99 999 | 8708 (66.3%) | 4433 (33.7%) | ||

| $100 000-$149 999 | 9972 (64.1%) | 5577 (35.9%) | ||

| $150 000 or more | 11 218 (62.3%) | 6796 (37.7%) | ||

Source: National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants.

aOther race includes PAs who selected “other,” Multiple Race, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native.

Figure 3.

One or more symptoms of burnout by satisfaction with work-life balance, hours working, and income (all P < 0.001).

PAs who reported improved working conditions in the past year had the lowest rate of burnout symptoms (21.5%), while those who indicated worsened conditions had one of the highest rates (52.4%). Other elevated rates of burnout were observed among PAs working more than 50 h weekly (47.0%), practicing in emergency medicine (42.2%), employed by organizations currently recruiting/hiring PAs (39.7%), and working in urgent care (39.5%).

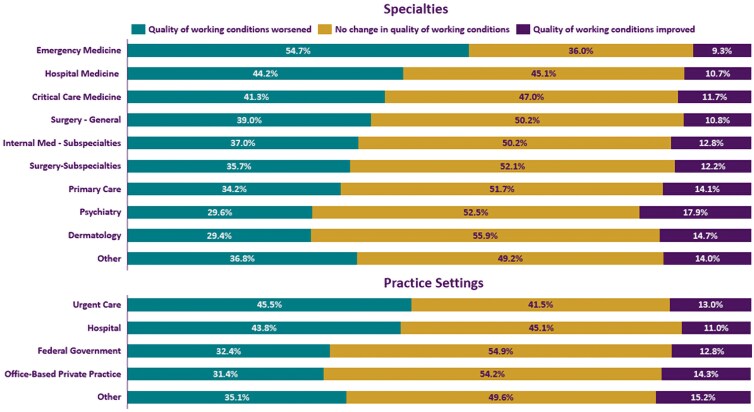

Figure 4 illustrates significant (both P < 0.001) changes in the quality of working conditions in the past year by specialties and practice settings. PAs in emergency medicine were most likely to report worsening conditions, while PAs practicing in dermatology were least likely (54.7% vs 29.4%). Regarding practice settings, PAs in urgent care had a higher proportion of noting that their working environment worsened compared to PAs in office-based private practice (45.5% vs 31.4%).

Figure 4.

Changes in quality of working conditions in the past year by specialties and practice settings (both P < 0.001).

Table 2 presents the results of a multivariate logistic regression with all covariates explored in the bivariate analyses. The factor most strongly associated with an increased probability of reporting at least one burnout symptom was the changing quality of working conditions. Compared to those who reported no changes, PAs who said their working conditions had worsened in the past year had a 19.9 percentage points higher probability of burnout (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Multivariate results: factors associated with reporting one or more burnout symptoms.

| 95% CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Marginal effects | LL | UL | P-value | |

| Age (less than 35 reference) | 35-44 | 0.022 | 0.014 | 0.030 | <0.001 |

| 45-54 | 0.006 | −0.004 | 0.016 | 0.235 | |

| 55-64 | −0.017 | −0.030 | −0.005 | 0.006 | |

| 65+ | −0.078 | −0.096 | −0.059 | <0.001 | |

| Gender (female reference) | Male | −0.069 | −0.077 | −0.062 | <0.001 |

| Race (white reference) | Asian | −0.013 | −0.027 | 0.001 | 0.059 |

| Black/African American | −0.048 | −0.066 | −0.031 | <0.001 | |

| Other | −0.006 | −0.020 | 0.009 | 0.442 | |

| Ethnicity (non-Hispanic Latino(a/x) reference)) | Hispanic/Latino(a/x) | −0.024 | −0.038 | −0.010 | 0.001 |

| Speaks another language (no reference) | Yes | −0.014 | −0.023 | −0.006 | 0.001 |

| Second position (only 1 clinical reference) | Secondary non-clinical position | 0.022 | 0.004 | 0.039 | 0.014 |

| Two or more clinical PA positions | −0.007 | −0.017 | 0.003 | 0.165 | |

| Specialty (primary care reference) | Surgery—subspecialties | −0.071 | −0.082 | −0.061 | <0.001 |

| Emergency medicine | 0.021 | 0.007 | 0.035 | 0.003 | |

| Internal medicine—subspecialties | −0.042 | −0.054 | −0.030 | <0.001 | |

| Dermatology | −0.058 | −0.075 | −0.041 | <0.001 | |

| Hospital medicine | −0.018 | −0.038 | 0.001 | 0.066 | |

| Surgery—general | −0.101 | −0.121 | −0.082 | <0.001 | |

| Psychiatry | 0.007 | −0.015 | 0.029 | 0.538 | |

| Critical care medicine | −0.015 | −0.039 | 0.010 | 0.236 | |

| Other | −0.039 | −0.049 | −0.029 | <0.001 | |

| Changed specialty (did not change reference) | Changed | 0.001 | −0.005 | 0.008 | 0.723 |

| Practice setting (office-based private practice reference) | Hospital | 0.002 | −0.007 | 0.010 | 0.729 |

| Urgent care | 0.046 | 0.030 | 0.061 | <0.001 | |

| Federal government | 0.018 | 0.002 | 0.035 | 0.029 | |

| Other | 0.004 | −0.007 | 0.015 | 0.494 | |

| Quality of working conditions (no changes reference) | Worsened | 0.199 | 0.192 | 0.207 | <0.001 |

| Improved | −0.032 | −0.042 | −0.023 | <0.001 | |

| Direct patient care (>75% reference) | <25% | 0.019 | −0.002 | 0.041 | 0.074 |

| 25%-50% | 0.012 | 0.002 | 0.021 | 0.013 | |

| 51%-75% | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.015 | 0.035 | |

| Hours working (30 or fewer hours reference) | 31-40 h | 0.053 | 0.043 | 0.062 | <0.001 |

| 41-50 h | 0.091 | 0.080 | 0.103 | <0.001 | |

| More than 50 h | 0.121 | 0.104 | 0.137 | <0.001 | |

| Working after hours (no reference) | Yes | −0.007 | −0.014 | 0.000 | 0.056 |

| Place of employment currently hiring PAs (no reference) | Yes | 0.055 | 0.049 | 0.062 | <0.001 |

| Not sure | 0.026 | 0.012 | 0.039 | <0.001 | |

| Satisfaction with work-life balance (not satisfied reference) | Satisfied | −0.251 | −0.263 | −0.239 | <0.001 |

| Satisfaction with number of hours working (not satisfied reference) | Satisfied | −0.045 | −0.057 | −0.034 | <0.001 |

| Satisfaction with income (not satisfied reference) | Satisfied | −0.045 | −0.053 | −0.036 | <0.001 |

| Current educational debt (no debt reference) | Less than $50 000 | 0.010 | −0.001 | 0.020 | 0.064 |

| $50 000-$99 999 | 0.005 | −0.005 | 0.016 | 0.307 | |

| $100 000-$149 999 | 0.019 | 0.009 | 0.029 | <0.001 | |

| $150 000 or more | 0.025 | 0.016 | 0.035 | <0.001 | |

Source: National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants.

Abbreviations: LL, lower limit; UL, upper limit; CI, confidence interval.

The second strongest factor associated with increased burnout was weekly hours worked. PAs working more than 50 h, compared to those working 30 or fewer, had a 12.1 percentage point higher probability of reporting burnout symptoms (P < 0.001). Additionally, PAs whose employers were recruiting/hiring PAs vs not had a 5.5 percentage point higher probability of burnout (P < 0.001). Compared to PAs in office-based private practice, those who practiced in urgent care were 4.6 percentage points more likely to report burnout (P < 0.001).

Compared to PAs with no educational debt, those with $150 000 or more had a 2.5 percentage point higher probability of burnout (P < 0.001). Other factors associated with higher probability included being 35-44 years old compared to under 35 (0.022; P < 0.001), having a second non-clinical position compared to 1 clinical position (0.022; P = 0.014), practicing in emergency medicine compared to primary care (0.021; P = 0.003), and working in the federal government vs office-based private practice (0.018; P = 0.029).

Spending 25% to 50% of the time in direct patient care (0.012; P = 0.013) and 51% to 75% (0.008; P = 0.035), compared to more than 75%, was also associated with a higher probability of burnout. Interestingly, unlike in the bivariate analyses, changing specialties in the past and working after hours were no longer significantly associated with burnout in the adjusted analysis. Conversely, the strongest factor associated with a lower probability of burnout was satisfaction with work-life balance. PAs who were satisfied with their work-life balance had a 25.1 percentage points lower probability of reporting burnout symptoms (P < 0.001) than those who were not satisfied. Regarding specialties, PAs practicing in general surgery (−0.101; P < 0.001), surgical subspecialties (−0.071; P < 0.001), dermatology (−0.058; P < 0.001), internal medicine subspecialties (−0.042; P < 0.001), and other specialties (−0.039; P < 0.001) had lower probability of burnout compared to those in primary care.

Regarding demographics, PAs aged 65 and over (−0.078; P < 0.001) had a significantly lower probability of burnout compared to those under 35. Male PAs had 6.9 percentage points lower burnout probability than their female colleagues (P < 0.001). PAs who self-identified as African American/Black (−0.048; P < 0.001) or Hispanic/Latino(a/x) (−0.024; P = 0.001) had a lower probability of reporting burnout symptoms compared to their White and non-Hispanic/Latino(a/x) counterparts, respectively. Additionally, PAs who spoke a second language with patients (−0.014; P = 0.001) also had a lower probability of burnout. Lastly, satisfaction with the number of working hours per week (−0.045; P < 0.001) and income (−0.045; P < 0.001), as well as improvements in working conditions over the past year (−0.032; P < 0.001), were associated with a lower probability of burnout.

Discussion

Our study explored a national dataset using COR theory as a lens to enhance our understanding of burnout among PAs. We found that over a third reported at least one symptom of burnout. Highlighting the importance of resources as they relate to burnout according to COR theory, a decline in working conditions over the past year was the most potent predictor of burnout. Conversely, being satisfied with work-life balance emerged as the strongest protective factor. Numerous other conditions, energy, and personal resources, along with demographic characteristics, demonstrated significant associations with burnout risk.

These findings align with COR theory, which posits that resource loss renders HCPs vulnerable to burnout, whereas gain offers protection.3 Deterioration of working conditions represents a loss of valuable condition resources. Consistent with COR predictions, PAs reporting worsening working conditions in the past year had a 19.9 percentage point higher probability of experiencing burnout than those reporting no change, even after controlling for covariates. This factor represented the strongest association with increased burnout observed in our study. Further in alignment with COR theory, specifically that losses exert a greater impact than equivalent gains,48 PAs reporting improved working conditions compared to those reporting no change experienced a less pronounced, though still significant, reduction in probability of burnout (3.2% lower).

We also found that the likelihood of worsening working conditions significantly differed by practice settings and specialties. PAs practicing in the emergency medicine specialty and urgent care practice setting were more likely to report a deteriorating working environment compared to their colleagues in other specialties and practice settings. Quality of working conditions may encompass pace of work, administrative burden, access to necessary equipment, support from administration, and many other important components.23,55,56 Additional qualitative research is needed to uncover more detailed insights into the nature of the worsening working conditions among PAs, especially those in emergency medicine and urgent care.

Our analysis identified additional workload-related factors associated with increased probability of burnout, including working more hours and the place of employment recruiting/hiring PAs. The finding that longer working hours are associated with increased burnout risk is consistent with prior literature. For example, Coplan et al. found that over half of PAs indicated excessive work hours contributed to their stress levels.35 Similarly, Tetzlaff and colleagues found that working more hours was associated with a greater risk for burnout among PAs practicing in oncology.57 Furthermore, the observed link between burnout and the place of employment actively recruiting/hiring PAs may indicate inadequate staffing and, consequently, higher individual workloads. In a study of Veteran Affairs (VA) primary care team members, which included PAs, Helfrich et al. found that the strongest association with decreased odds of burnout was having a fully staffed team.58 Viewed through COR theory, prolonged work hours and working in short-staffed environments drain energy reserves and, over time, contribute to burnout. Future studies should investigate if the duration in months the positions have been unfilled is monotonically associated with burnout risk among PAs.

Interestingly, while a secondary clinical position showed no significant association, a secondary non-clinical position was linked to a significantly higher probability of burnout. This suggests that the non-clinical role may drain more energy resources (physical and mental) due to a different skill requirement compared to the second clinical position, which allows for more efficient use of core clinical knowledge and skills. Additionally, we found that the probability of burnout was higher among PAs who spent less time in direct patient care. This finding likely reflects a corresponding increase in time dedicated to administrative tasks, a known contributor to burnout. In a recent longitudinal study, Arndt and colleagues showed that time spent on electronic health record activities increased from 2019 to 2023 among primary care physicians.59 A systematic review revealed that a high number of patient messages and insufficient time for documentation were frequently associated with higher burnout rates among HCPs.60 Future research should examine the potential mediating effect of the proportion of time spent in direct patient care on the relationship between longer working hours and burnout.

Consistent with other studies, we found differences in the likelihood of experiencing burnout by specialties. Compared to primary care, PAs in emergency medicine exhibited a higher probability of reporting burnout, which aligns with the 2018 AAPA report showing that PAs in emergency medicine have the highest prevalence of burnout.11 Similarly, a recent systematic review indicated high burnout rates among physicians and nurses in emergency departments.61 This increased risk may reflect the unique high-acuity, high-pressure demands inherent to emergency medicine, distinct from the primary care stressors, such as high patient volume. Similarly, PAs in urgent care vs office-based private practice had 4.6 percentage points higher probability of reporting burnout. In contrast, those in general surgery, surgery subspecialties, dermatology, and internal medicine subspecialties had a lower probability than primary care.

Interestingly, having changed specialties was not significantly associated with burnout symptoms in the multivariate model. The non-significant finding may be due to the variability in the timing of switching specialties (recently vs years ago), which we did not account for in our study. Research suggests that transitioning to a new specialty can be challenging in the first few months, but PAs quickly adapt, particularly if onboarding is provided.30 Future research should investigate the relationship between the timing of specialty transitions and burnout, particularly focusing on whether burnout risk is higher during the period immediately following the change and lower after a year or longer has passed.

In our study, high educational debt vs none was also associated with a higher probability of burnout. For example, accruing $150 000 in educational debt was associated with a 2.5 percentage point higher probability vs no debt. A study with oncology fellows showed that having $150 000 in debt was associated with over 2-fold higher odds of burnout.33 High educational debt may necessitate working more hours, taking on more shifts, or delaying taking needed time off to pay off the debt, further perpetuating burnout.62 From a COR perspective, high educational debt acts as an initial resource deficit and a chronic threat to current and future resources. Paying off the debt necessitates further resource expenditure (working more hours), taking jobs for financial reasons rather than professional fit or work-life balance, and hindering resource replenishment activities (taking vacations or self-care practices).

Conversely, the strongest factor associated with decreased burnout was satisfaction with work-life balance. PAs who were satisfied with work-life balance had a 25.1 percentage point lower probability of burnout. This finding is consistent with Dyrbye et al., who found that PAs who were not satisfied with their work-life balance had almost 3-fold higher odds of reporting burnout.26 Moreover, we found that satisfaction with hours worked and income were associated with a lower probability of reporting burnout symptoms. PAs satisfied with work-life balance, hours, and income likely perceive their resources (time, energy, financial stability) as not being threatened but stable and replenished. These resources may buffer them against stressors inherent in their work, leading to less burnout.

Lastly, we also found that PA demographics were associated with burnout. Compared to PAs under 35, those 55-64 and 65 and over had a lower probability of burnout; however, PAs 35-44 had a higher probability. Male PAs had a lower probability of burnout than their female colleagues. These results are consistent with a systematic review showing that younger HCPs and females are more likely to experience burnout. We also found that PAs self-identifying as Hispanic/Latino(a/x) and African American/Black had a lower probability of burnout. These results are similar to a study by Garcia and colleagues of 4424 physicians across different specialties.63 From a COR perspective, our findings suggest that these demographic groups might possess or have access to key personal and condition resources that protect against the chronic resource depletion characteristic of burnout. For example, older PAs may have accumulated more resources over their careers. Hispanic and African American/Black PAs might have social or community resources or developed personal resources, such as resilience, potentially cultivated through other life challenges. However, these are only interpretations based on general principles of COR theory, and further research is needed. Moreover, Garcia et al. warned that the observed differences by race and ethnicity in their study must be interpreted with caution and further studied, given that HCPs from minority backgrounds may be less likely to acknowledge experiencing burnout due to stigma, survival bias (not accounting HCPs from minority backgrounds who have left the profession), or due to a selection process that prioritizes resilience among students from minority backgrounds.63

Conclusion

Using COR theory as a practical framework, we found that condition, energy, and personal resources were associated with the probability of burnout among PAs. However, a decline in working conditions over the past year was the most potent predictor of burnout. Conversely, being satisfied with work-life balance emerged as the strongest factor associated with a lower risk of burnout. Strategies and local and national policies focusing on maintaining quality working environments to reduce burnout risk should be prioritized. Our work advances the literature on burnout among PAs and contributes to the basis for future research. We recommend monitoring changes in the quality of working conditions, uncovering the underlying reasons for these changes through qualitative research, and identifying effective interventions that can prevent or decrease burnout risk. Understanding the specific challenges PAs face and addressing burnout is vital to ensuring a sustainable and resilient workforce.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Andrzej Kozikowski, National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants, Johns Creek, GA 30097, United States.

Mirela Bruza-Augatis, National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants, Johns Creek, GA 30097, United States.

Sarah Maddux, Department of Physician Assistant Studies, Idaho State University, Caldwell, ID 83605, United States.

Kasey Puckett, National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants, Johns Creek, GA 30097, United States.

Dawn Morton-Rias, National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants, Johns Creek, GA 30097, United States.

Joshua Goodman, National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants, Johns Creek, GA 30097, United States.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Health Affairs Scholar online.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

The Serling Institutional Review Board (IRB#10826) determined that the study was not human subject research and required no further review.

Notes

- 1. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113. 10.1002/job.4030020205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dean W, Morris D, Llorca PM, et al. Moral injury and the global health workforce crisis—insights from an international partnership. New J Med. 2024;391(9):782–785. 10.1056/NEJMp2402833 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Williams ES, Rathert C, Buttigieg SC. The personal and professional consequences of physician burnout: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2020;77(5):371–386. 10.1177/1077558719856787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kaushik D. COVID-19 and health care workers burnout: a call for global action. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;35:100808. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Burnout among health care professionals: a call to explore and address this underrecognized threat to safe, high-quality care. In: NAM Perspect. Discussion Paper. National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC; 2017:1–11. 10.31478/201707b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reith TP. Burnout in United States healthcare professionals: a narrative review. Cureus. 2018;10:e3681. 10.7759/cureus.3681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1131–1150. 10.1001/jama.2018.12777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Prasad K, McLoughlin C, Stillman M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of stress and burnout among US healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cross-sectional survey study. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;35:100879. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abraham CM, Zheng K, Norful AA, Ghaffari A, Liu J, Poghosyan L. Primary care nurse practitioner burnout and perceptions of quality of care. Nursing Forum. Vol 56. Wiley Online Library; 2021:550–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bourdeanu L, Zhou QP, DeSamper M, Pericak KA, Pericak A. Burnout, workplace factors, and intent to leave among hematology/oncology nurse practitioners. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2020;11(2):141. 10.6004/jadpro.2020.11.2.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. American Academy of PAs . Are PAs Burned Out? May 4, 2018. Accessed March 10, 2025. https://www.aapa.org/news-central/2018/05/pas-report-low-burnout/

- 12. Gisewhite S, Reith A. Burnout among physician assistants: a systematic review. J Med Pract Manage. 2021;36(4):195–204. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lacy BE, Chan JL. Physician burnout: the hidden health care crisis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(3):311–317. 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Blackstone SR, Johnson AK, Smith NE, McCall TC, Simmons WR, Skelly AW. Depression, burnout, and professional outcomes among PAs. JAAPA. 2021;34(9):35–41. 10.1097/01.JAA.0000769676.27946.56 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abraham CM, Zheng K, Norful AA, Ghaffari A, Liu J, Poghosyan L. Primary care nurse practitioner burnout and perceptions of quality of care. Nurs Forum. 2021;56(3):550–559. 10.1111/nuf.12579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tawfik DS, Scheid A, Profit J, et al. Evidence relating health care provider burnout and quality of care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(8):555. 10.7326/M19-1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995–1000. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Casalino LP, Li J, Peterson LE, et al. Relationship between physician burnout and the quality and cost of care for Medicare beneficiaries is complex. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(4):549–556. 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Meredith LS, Bouskill K, Chang J, Larkin J, Motala A, Hempel S. Predictors of burnout among US healthcare providers: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022;12(8):e054243. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054243 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Azam K, Khan A, Alam MT. Causes and adverse impact of physician burnout: a systematic review. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2017;27(8):495–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Linzer M, O’Brien EC, Sullivan E, et al. Burnout in modern-day health care: where are we, and how can we markedly reduce it? A meta-narrative review from the EUREKA* project. Health Care Manage Rev. 2025;50(2):57–66. 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rotenstein LS, Brown R, Sinsky C, Linzer M. The association of work overload with burnout and intent to leave the job across the healthcare workforce during COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(8):1920–1927. 10.1007/s11606-023-08153-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sibeoni J, Bellon-Champel L, Mousty A, Manolios E, Verneuil L, Revah-Levy A. Physicians’ perspectives about burnout: a systematic review and metasynthesis. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(8):1578–1590. 10.1007/s11606-019-05062-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lin RT, Lin YT, Hsia YF, Kuo CC. Long working hours and burnout in health care workers: non-linear dose-response relationship and the effect mediated by sleeping hours—a cross-sectional study. J Occup Health. 2021;63(1):e12228. 10.1002/1348-9585.12228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jung FU, Bodendieck E, Bleckwenn M, Hussenoeder FS, Luppa M, Riedel-Heller SG. Burnout, work engagement and work hours—how physicians’ decision to work less is associated with work-related factors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):157. 10.1186/s12913-023-09161-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dyrbye LN, West CP, Halasy M, O’Laughlin DJ, Satele D, Shanafelt T. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration among PAs relative to other workers. JAAPA. 2020;33(5):35–44. 10.1097/01.JAA.0000660156.17502.e6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang Q, Mu M-C, He Y, Cai Z-L, Li Z-C. Burnout in emergency medicine physicians: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(32):e21462. 10.1097/MD.0000000000021462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kozikowski A, Bruza-Augatis M, Morton-Rias D, et al. Physician assistant/associate career flexibility: factors associated with specialty transitions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024;24(1):1660. 10.1186/s12913-024-12158-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Osborn M, Satrom J, Schlenker A, Hazel M, Mason M, Hartwig K. Physician assistant burnout, job satisfaction, and career flexibility in Minnesota. JAAPA. 2019;32(7):41–47. 10.1097/01.JAA.0000558344.55492.5a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ward-Lev E, Kuriakose C, Navoa JJ, Halley M. Career flexibility for PAs: what makes switching specialties successful? JAAPA. 2024;37(5):29–34. 10.1097/01.JAA.0000000000000004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Verduzco-Gutierrez M, Larson AR, Capizzi AN, et al. How physician compensation and education debt affects financial stress and burnout: a survey study of women in physical medicine and rehabilitation. PM R. 2021;13(8):836–844. 10.1002/pmrj.12534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. West CP, Shanafelt TD, Kolars JC. Quality of life, burnout, educational debt, and medical knowledge among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2011;306(9):952–960. 10.1001/jama.2011.1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ahmed AA, Ramey SJ, Dean MK, et al. Socioeconomic factors associated with burnout among oncology trainees. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16(4):e415–e424. 10.1200/JOP.19.00703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kozikowski A, Bruza-Augatis M, Morton-Rias D, et al. The effect of education debt on PAs’ specialty choice or preference. JAAPA. 2025;38(1):35–44. 10.1097/01.JAA.0000000000000166 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Coplan B, McCall TC, Smith N, Gellert VL, Essary AC. Burnout, job satisfaction, and stress levels of PAs. JAAPA. 2018;31(9):42–46. 10.1097/01.JAA.0000544305.38577.84 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hoff T, Carabetta S, Collinson GE. Satisfaction, burnout, and turnover among nurse practitioners and physician assistants: a review of the empirical literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2019;76(1):3–31. 10.1177/1077558717730157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Essary AC. Burnout and job and career satisfaction in the physician assistant profession: a review of the literature. In: Discussion Paper. National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC; 2018:1–11. 10.31478/201812b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. US Bureau of Labor Statistics . Fastest Growing Occupations. August 29, 2024. Accessed March 16, 2025. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/fastest-growing.htm

- 39. National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants, Inc. 2023 Statistical Profile of Board Certified PAs,Annual Report 2024. Accessed January 20, 2025. https://www.nccpa.net/resources/nccpa-research/ [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. 1989;44(3):513–524. 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hobfoll SE, Halbesleben J, Neveu JP, Westman M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2018;5(1):103–128. 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Halbesleben JRB, Neveu JP, Paustian-Underdahl SC, Westman M. Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J Manage. 2014;40(5):1334–1364. 10.1177/0149206314527130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources theory: its implication for stress, health, and resilience. In: The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping. Oxford University Press; 2012:127–147. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195375343.013.0007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hobfoll SE, Ford JS. Conservation of resources theory. In: Fink G, ed. Encyclopedia of Stress. 2nd ed. Vol 1. Oxford: Academic Press; 2007:562–567. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Munoz A, Girguis S, Martin L, Hollifield M. Applying and extending the Conservation of Resources (COR) model to trauma in U. S. veterans. Trauma Care. 2024;4(1):22–30. 10.3390/traumacare4010003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Westman M, Hobfoll SE, Chen S, Davidson OB, Laski S. Organizational Stress Through The Lens of Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory. In: Research in Occupational Stress and Well Being. Vol 4. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2004:167–220. 10.1016/S1479-3555(04)04005-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Alvaro C, Lyons RF, Warner G, et al. Conservation of resources theory and research use in health systems. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):79. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hobfoll SE, Freedy J. Conservation of resources: a general stress theory applied to burnout. In: Professional Burnout. Routledge; 2017:115–129. 10.4324/9781315227979-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Glicken AD. Physician assistant profile tool provides comprehensive new source of PA workforce data. JAAPA. 2014;27(2):47–49. 10.1097/01.JAA.0000442708.26094.02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dolan ED, Mohr D, Lempa M, et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: a psychometric evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):582–587. 10.1007/s11606-014-3112-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rohland BM, Kruse GR, Rohrer JE. Validation of a single-item measure of burnout against the Maslach Burnout Inventory among physicians. Stress Health. 2004;20(2):75–79. 10.1002/smi.1002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Norton EC, Dowd BE, Garrido MM, Maciejewski ML. Requiem for odds ratios. Health Serv Res. 2024;59(4):e14337. 10.1111/1475-6773.14337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. O’brien RM. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual Quant. 2007;41(5):673–690. 10.1007/s11135-006-9018-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Arel-Bundock V, Greifer N, Heiss A. How to interpret statistical models using marginaleffects for R and Python. J Stat Softw. 2024;111(9):1–32. 10.18637/jss.v111.i09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. de Vries N, Boone A, Godderis L, et al. The race to retain healthcare workers: a systematic review on factors that impact retention of nurses and physicians in hospitals. Inquiry. 2023;60:00469580231159318. 10.1177/00469580231159318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Seidler A, Thinschmidt M, Deckert S, et al. The role of psychosocial working conditions on burnout and its core component emotional exhaustion—a systematic review. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2014;9(1):10. 10.1186/1745-6673-9-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tetzlaff ED, Hylton HM, DeMora L, Ruth K, Wong YN. National study of burnout and career satisfaction among physician assistants in oncology: implications for team-based care. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14(1):e11–e22. 10.1200/JOP.2017.025544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Helfrich CD, Simonetti JA, Clinton WL, et al. The association of team-specific workload and staffing with odds of burnout among VA primary care team members. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(7):760–766. 10.1007/s11606-017-4011-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Arndt BG, Micek MA, Rule A, Shafer CM, Baltus JJ, Sinsky CA. More tethered to the EHR: EHR workload trends among academic primary care physicians, 2019-2023. Ann Fam Med. 2024;22(1):12–18. 10.1370/afm.3047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yan Q, Jiang Z, Harbin Z, Tolbert PH, Davies MG. Exploring the relationship between electronic health records and provider burnout: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(5):1009–1021. 10.1093/jamia/ocab009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Jachmann A, Loser A, Mettler A, Exadaktylos A, Müller M, Klingberg K. Burnout, depression, and stress in emergency department nurses and physicians and the impact on private and work life: a systematic review. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2025;6(2):100046. 10.1016/j.acepjo.2025.100046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Shanafelt T. Burnout in anesthesiology: a call to action. Anesthesiology. 2011;114(1):1–2. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318201cf92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Garcia LC, Shanafelt TD, West CP, et al. Burnout, depression, career satisfaction, and work-life integration by physician race/ethnicity. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2012762. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.