Abstract

Background

Chronic venous disease (CVD) is a common vascular condition that can have debilitating effects on quality of life and daily function. The Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) sought to develop evidence-based guidelines to support patients, clinicians, and other stakeholders in their treatment decisions about management of CVD.

Methods

SCAI convened a balanced multidisciplinary guideline panel to minimize potential bias from conflicts of interest. The Evidence Foundation, a registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, provided methodological support for the development of the guidelines. The guideline panel formulated and prioritized clinical questions following the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach in population, intervention, comparison, outcome format. A technical review team of clinical and methodological experts conducted systematic reviews of the published evidence, synthesized data, and graded the certainty of the evidence across outcomes. The guideline panel then reconvened to develop recommendations and supporting remarks informed by the results of the technical review, as well as additional contextual factors described in the GRADE evidence-to-decision framework.

Results

The guideline panel reached consensus on 9 recommendations to address variations in treatment of CVD across 8 different clinical scenarios. The panel also identified 4 anatomical scenarios with significant knowledge gaps.

Conclusions

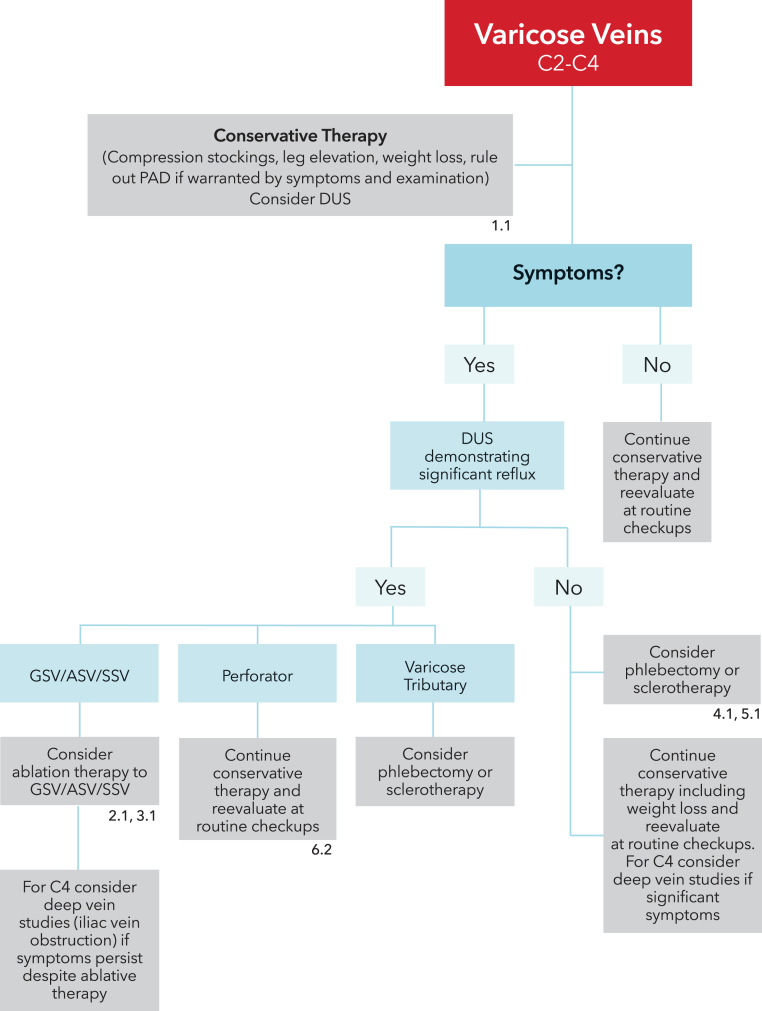

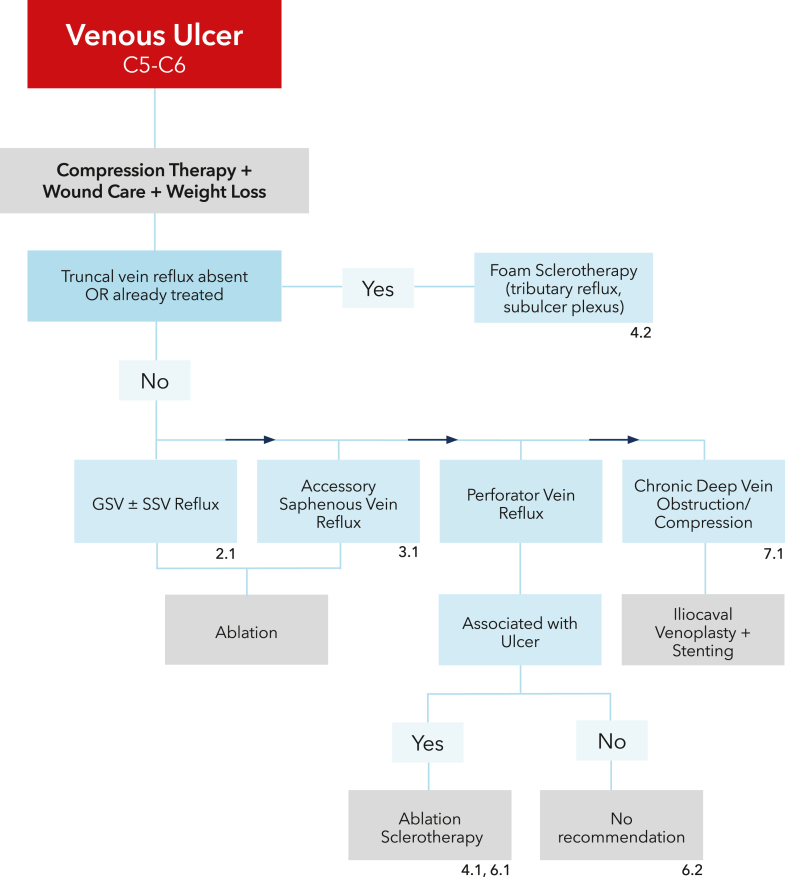

Key recommendations address patient selection for compression therapy, ablation of saphenous and perforator veins, sclerotherapy, phlebectomy, and deep vein revascularization. Two algorithms for the management of symptomatic varicose veins and venous ulcer disease were created to facilitate implementation of these evidence-based recommendations. The panel also identified several anatomical and clinical areas where future research is needed to advance the CVD field.

Keywords: chronic venous disease, ulceration, varicose veins, venous insufficiency

Summary of recommendations

Background

Chronic venous disease (CVD) affects over 25 million adults in the United States and is associated with symptoms that can adversely affect quality of life (QoL), such as leg discomfort, aching, heaviness, pruritis, edema, and ulceration. Treatments for CVD range from conservative therapy centered on use of compression and wound care to more invasive approaches such as ablation, sclerotherapy, phlebectomy, venoplasty, and stenting.

Methods

These Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) guidelines are based on original systematic reviews of evidence conducted with support from the Evidence Foundation. The panel followed best practices for guideline development described by the National Academies of Medicine (formerly Institute of Medicine) and the Guidelines International Network.1, 2, 3 The panel used Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology to assess the certainty of the evidence and formulate recommendations.4,5

Interpretation of strong and conditional recommendations

The strength of a recommendation is expressed as either strong (the guideline panel recommends…) or conditional (the guideline panel suggests…) and has the following interpretations:

Strong recommendation

-

⁃

For patients: most patients in this situation would want the recommended course of action, and only a small proportion would not.

-

⁃

For clinicians: most patients should receive the recommended intervention or test. Formal decision aids are not likely to be needed to assist individual patients in making decisions consistent with their values and preferences.

-

⁃

For policy makers: the recommendation can be adopted as policy in most situations. Adherence to this recommendation according to the guideline could be used as a quality metric/criterion or performance indicator.

Conditional recommendation

-

⁃

For patients: the majority of individuals in this situation would want the suggested course of action, but some would not.

-

⁃

For clinicians: recognize that different choices will be appropriate for individual patients and that you must help each patient arrive at a management decision consistent with his or her values and preferences. Decision aids may be useful in helping individuals to make decisions consistent with their values and preferences.

-

⁃

For policy makers: policymaking will require substantial debate and involvement of various stakeholders. Performance measures about the suggested course of action should focus on documentation of an appropriate decision making process.

Recommendations

-

1.In patients who have symptomatic CVD of the lower extremities, should compression therapy be used rather than no compression?

-

1.1For patients with symptomatic varicose veins and/or chronic venous insufficiency, the SCAI guideline panel suggests compression therapy rather than no compression therapy (conditional recommendation, very low certainty of evidence).

- Remarks: Some patients who value more rapid resolution of symptoms and are less concerned with potential complications may prefer interventional alternatives to compression therapy such as sclerotherapy, phlebectomy, or ablation if appropriate. Stronger grades of compression therapy may be more effective.

-

1.2For patients with venous ulcers, the SCAI guideline panel recommends compression therapy rather than no compression therapy (strong recommendation, moderate certainty of evidence).

- Remarks: Stronger grades of compression therapy may be more effective.

-

1.1

-

2.In adults with symptomatic great saphenous vein with or without small saphenous vein reflux, should ablation therapy plus conservative management be performed rather than conservative management alone?

-

2.1For patients with symptomatic great saphenous vein (GSV) with or without small saphenous vein (SSV) reflux, the SCAI guideline panel suggests ablation therapy plus conservative management rather than conservative management alone (conditional recommendation, low certainty of evidence).

- Remarks: Patients without ulcers may place a higher value on avoiding procedural complications and a lower value on uncertain benefits of ablation and may reasonably choose conservative management. Patients with ulcers, with debilitating symptoms, or who failed conservative therapy may prefer ablation therapy. Depending on the functional and anatomic status of GSV, intervention on the GSV may impact availability for future coronary artery bypass grafting or vascular surgery and may not be suitable for patients with advanced coronary or peripheral artery disease. However, the decision to preserve a GSV for potential future bypass would depend on its suitability, and dilated GSVs may not be suitable conduits.

-

2.1

-

3.In adults with symptomatic accessory GSV reflux, should ablation therapy plus conservative therapy be performed rather than conservative therapy alone?

-

3.1For patients with symptomatic accessory GSV reflux, the SCAI guideline panel suggests ablation therapy plus conservative management rather than conservative management alone (conditional recommendation, very low certainty of evidence).

- Remarks: Accessory veins encompass normal anatomic variants including the anterior and posterior accessory, which often run adjacent to the GSV. When accessory veins are associated with pathology such as ulcers or other symptoms, patients may reasonably choose ablation therapy. An accessory GSV sometimes drains pathologic tributary veins that may not be treatable with ablative therapy due to tortuosity or other anatomic considerations. The anterior and posterior accessory GSV were recently renamed anterior and posterior GSV.

-

3.1

-

4.In adults with symptomatic varicose veins, should sclerotherapy plus conservative management be performed rather than conservative therapy alone?

-

4.1For patients with symptomatic varicose veins without truncal vein reflux, the SCAI guideline panel suggests foam sclerotherapy plus conservative management rather than conservative management alone (conditional recommendation, very low certainty of evidence).

- Remarks: Most patients with symptomatic varicose veins would prefer sclerotherapy over conservative therapy, but some may not. Hyperpigmentation can occur following sclerotherapy and, in some cases, may be permanent. This may be of lesser concern to patients who place a greater emphasis on symptom relief over cosmetic outcome.

-

4.2For patients with venous ulcers without truncal vein reflux, the SCAI guideline panel suggests foam sclerotherapy plus conservative management rather than conservative management alone (conditional recommendation, low certainty of evidence).

- Remarks: Patients with recurrent ulcers or ulcers that do not respond to conservative management may prefer sclerotherapy. Sclerotherapy would target varicosities associated with the ulcer bed and the venous subulcer plexus. Patients with nonhealing ulcers where mixed etiology is suspected (eg, with concomitant peripheral artery disease) may benefit from arterial revascularization.

-

4.1

-

5.In adults with symptomatic varicose veins (C2-C4), should phlebectomy plus conservative therapy be performed rather than conservative therapy alone?

-

5.1For patients with symptomatic varicose veins without truncal vein reflux, the SCAI guideline panel suggests phlebectomy plus conservative management rather than conservative management alone (conditional recommendation, very low certainty of evidence).

- Remarks: Patients who have recurrent symptomatic varicose veins despite treatment of truncal veins and patients without truncal vein reflux but with symptomatic tributary varicose veins may prefer phlebectomy.

-

5.2The SCAI guideline panel makes no recommendation regarding phlebectomy plus conservative management compared with conservative management alone in patients with venous ulcers (no recommendation, knowledge gap).

-

5.1

-

6.In adults with symptomatic perforator vein reflux, should ablation therapy plus conservative management be performed rather than conservative management alone?

-

6.1For patients with ulcer-associated perforator vein reflux, the SCAI guideline panel suggests ablation therapy plus conservative management rather than conservative management alone (conditional recommendation, low certainty of evidence).

-

6.2The SCAI guideline panel makes no recommendation regarding patients with symptomatic perforator reflux without associated ulcer(s) (no recommendation, knowledge gap).

-

6.1

-

7.In patients with symptomatic CVD with severe deep venous stenosis of the iliocaval segment, should venoplasty or stenting plus conservative management be performed rather than conservative management alone?

-

7.1For patients with symptomatic chronic deep vein obstruction/stenosis, the SCAI guideline panel suggests venoplasty or stenting of iliocaval veins plus conservative management rather than conservative management alone (conditional recommendation, low certainty of evidence).

- Remarks: Appropriate patient selection based on clinical and anatomical factors and technical expertise are important to derive benefit and minimize complications from iliocaval stenting. Patients may reasonably decline venoplasty or stenting if they place a higher value on avoiding potential procedure-related adverse events and a lower value on potential reduction of discomfort or improvement of symptoms. Diagnosis and vessel sizing can be aided with the use of intravascular imaging.

-

7.1

-

8.In patients with symptomatic CVD with deep venous obstruction/stenosis of the femoral veins, should venoplasty with or without stenting plus conservative management be performed rather than conservative management alone?

-

8.1The SCAI guideline panel makes no recommendation regarding venoplasty with or without stenting plus conservative management compared with conservative management alone in patients with postthrombotic chronic isolated femoral vein disease (no recommendation, knowledge gap).

-

8.2The SCAI guideline panel makes no recommendation regarding venoplasty with or without stenting plus conservative management compared with conservative management alone in patients with postthrombotic chronic isolated common femoral vein disease (no recommendation, knowledge gap).

-

8.1

Good practice statement

As obesity negatively impacts outcomes in CVD, clinicians should continue to address lifestyle changes, weight loss, and exercise for all patients including candidates for interventional treatment.

Definitions

Truncal veins are the major veins in the leg carrying blood from the superficial into the deep venous system, with the 3 major ones being the GSV, SSV, and accessory GSVs. Anterior and posterior accessory GSVs have been renamed anterior and posterior GSVs, respectively. Axial reflux is defined as uninterrupted retrograde flow: in the case of the GSV, from the groin to the upper calf and, in the SSV, from the calf to the ankle. This is in contrast to segmental reflux. Reflux is defined as reverse flow within truncal or perforator veins of >500 milliseconds.6

Introduction

Chronic venous insufficiency is associated with venous obstruction, reflux, or both, resulting in ambulatory venous hypertension and inflammation.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Lower extremity chronic venous disease (CVD) can be associated with progressive discomfort, heaviness, edema, discoloration, and ulceration.11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Although often overlooked by health care providers, it can impose a significant burden on patients’ quality of life (QoL).16,17 In the United States, more than 25 million adults experience chronic venous insufficiency.17

Risk factors for CVD include age, a family history, female sex, obesity, prolonged standing, pregnancy, parity, and a history of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). The prevalence of varicose veins can be as high as 57% in men and 73% in women.17,18 Edema and ulcers are more common in patients aged >65 years.12

Chronic venous disease is the leading cause of leg ulcers.19 Venous leg ulcers can affect as much as 2% of the population.7,20, 21, 22, 23 Venous ulcers are typically found in the gaiter zone of the legs (in particular at the medial and lateral aspects of malleoli and pretibial regions). They are associated with depression and poor QoL.24 An estimated 2.2% of Medicare beneficiaries in the United States have venous leg ulcers, with an annual payer burden of $14.9 billion.25

Venous valvular reflux can occur within various locations such as the saphenous, perforator, and deep veins.26 Saphenous veins form part of the superficial venous system draining the subcutaneous tissues and skin. The deep venous system includes the tibial, peroneal, gastrocnemius, soleal, popliteal, femoral, common femoral, and iliac veins.27 The deep venous system is responsible for the majority of the venous return from the lower extremities. Obstruction can occur following DVT, but can also be nonthrombotic, for instance, during iliac vein compression.28,29

The first line of treatment for CVD is conservative therapy, which generally includes compression therapy, venotonic medications, lifestyle changes, weight loss if applicable, and wound care for patients with ulcerative disease. Compression garments can take the form of bandages, stockings, Velcro wrap devices, pumps, or a combination of these items. Conservative therapy, however, may not resolve all symptoms, and poor adherence is a well-documented limitation of conservative therapy.30,31 Furthermore, patients with advanced disease such as ulcers may warrant early invasive intervention, where appropriate.

In the case of superficial venous reflux, when conservative therapy fails to control symptoms of CVD, invasive treatment has included the resection or closure of the incompetent truncal veins (great saphenous vein [GSV], small saphenous vein [SSV], and accessory saphenous vein), or perforator veins. To accomplish this, particularly in Western countries, ablation has largely replaced surgical stripping.32,33 Ablation therapy can be divided into thermal and nonthermal modalities. Thermal ablation uses radiofrequency or laser energy administered through a narrow fiber directly inserted into the target vein. The generated heat leads to injury and eventual vein fibrosis and occlusion. Nonthermal ablation modalities include mechanochemical ablation, cyanoacrylate adhesive ablation, and foam sclerotherapy. As with thermal ablation, nonthermal techniques can be complicated by DVT, although it is rare.34,35 For patients with deep venous obstruction of either the iliocaval or femoral veins, venoplasty and/or stenting have been used as treatment, with limited evidence supporting their use.36,37 The past 15 years have seen a significant rise in the number of endovascular venous procedures performed in the United States, with cardiology being one of the leading specialties involved.38 Cardiologists and interventional cardiologists play a critical role as key stakeholders in managing CVD and providing longitudinal care for affected patients. Additionally, cardiologists are asked to evaluate and treat leg edema more than any other specialty, resulting in a patient population that may not be reflected in existing guidelines on management of CVD.

Methods

The guideline panel developed clinical questions, assessed the certainty of the evidence, and graded the recommendations in these guidelines following the GRADE approach.5,39,40 The evidence profile and certainty of the evidence are discussed in detail in the accompanying technical review article.41 Readers should refer to the technical review for additional details about the evidence supporting the recommendations discussed in this article.

The guideline development process, including funding, establishment of the guideline panel, management of conflicts of interest, internal and external review, and societal approval, was directed by SCAI policies and procedures derived from the Guidelines International Network–McMaster Guideline Development Checklist (http://cebgrade.mcmaster.ca/guidecheck.html) and intended to meet standards for trustworthy guidelines from the National Academies of Medicine (formerly Institute of Medicine).42

Organization, guideline panel composition, planning, and coordination

The panel was coordinated and sponsored by SCAI. The Standards and Guidelines Committee, reporting to the Executive Committee, provided oversight of the project. SCAI appointed individuals to the guideline panel and separately identified a group of researchers who conducted a series of systematic reviews to support the guideline development process. The membership of the guideline panel and the technical review team is described in Supplemental Table S1.

The guideline panel included interventional cardiologists, vascular surgeons, and 1 vascular medicine specialist representing the Society for Vascular Medicine, who have clinical and research expertise on the management of patients with CVD and methodologists with expertise in evidence appraisal and guideline development. The panel’s work and deliberations were conducted via a series of virtual meetings conducted between October 10, 2023, and November 2, 2023.

Guideline funding and management of conflicts of interest

Development of these guidelines was wholly funded by SCAI, a nonprofit medical specialty society that represents interventional cardiologists. SCAI staff provided logistical support for the technical review, management of conflict of interest, guideline development process, and manuscript preparation but had no role in selecting the guideline questions or determining the recommendations.

Physician members of the panel participated voluntarily and received no financial compensation for their contributions. Methodological support was provided by the Evidence Foundation, a registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

All participants’ conflicts of interest were managed in accordance with SCAI policies, which align with recommendations from the National Academies of Medicine and the Guidelines International Network.1,43 At the time of appointment, a majority of the guideline panel, including the chair and the vice chair, had no conflicts of interest as defined and judged by the Standards and Guidelines Committee. Researchers affiliated with the Evidence Foundation, who assisted with the technical review and guideline development, had no financial ties to commercial entities with products potentially impacted by the guidelines.

Before joining the panel, individuals disclosed financial and nonfinancial interests, which was reviewed by the Standards and Guidelines Committee. Supplemental Table S1 provides the complete disclosure of interest forms of all panel members.

Formulating specific clinical questions and determining outcomes of interest

The SCAI guideline panel and methodologists formulated each clinical question and prioritized outcomes a priori using the GRADE approach.39 Each question was developed using a framework that identifies a specific population, intervention, comparator, and outcomes (PICO). Outcomes were rated numerically for their relative importance to clinical decision making on a scale of 1-9. Outcomes receiving a score of 7 to 9 were considered critical, while scores of 4 to 6 were considered important, and scores of 1 to 3 were considered less important for clinical decision making. Only critical outcomes (7-9) were included in the final list of PICO questions. PICO questions were further reviewed by the technical review team (Supplemental Table S2).

Evidence review and development of recommendations

Each PICO question was addressed by a rigorous systematic review, with the findings summarized in GRADE evidence profiles (Supplemental Table S3).5,44 These results are reported in detail in the companion technical review article.41 The certainty of the evidence (also known as the level or quality of the evidence) relevant to each outcome was assessed using the GRADE approach based on the risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, likelihood of publication bias, magnitude of effect, dose–response relationship, and opposing residual effect. Guideline panel members received the evidence profiles before deliberating on recommendations.

The panel developed recommendations during four 2-hour virtual meetings. Recommendations were informed by the evidence profiles, certainty of evidence ratings, patient values and preferences, the balance of benefits and harms of the intervention and comparator, resource use, health equity, acceptability to key stakeholders, and feasibility considerations. The panel agreed on each recommendation statement including the direction of the recommendation (for or against the intervention or comparator), strength of recommendation (strong or conditional), and if deemed appropriate, accompanying remarks by consensus. Unanimity among a quorum of 75% of the authors was required for consensus. During the panel deliberation, the accompanying text for the narrative, including implementation considerations and future research priorities, was also discussed. The final manuscript has been reviewed and approved by all members of the panel.

Document review

The draft manuscript was reviewed by all members of the panel and then made available online in November 2024 for external review by stakeholders. The document was revised to address relevant comments. In April 2025, the SCAI Standard and Guidelines Committee approved the manuscript; in May 2025, the officers of the SCAI Executive Committee approved the guidelines for publication under the imprimatur of SCAI.

How to use these guidelines

These guidelines are intended to help clinicians and patients make decisions about the management of CVD, including procedural interventions and their alternatives. The guidelines should also be used to inform policy, education, and advocacy and to describe knowledge gaps to stimulate future research. These guidelines are not intended to serve as a standard of care. Clinicians must take into account the unique circumstances of each patient, ideally through a collaborative process that considers the patient’s values and preferences. Decisions may be influenced by clinical setting and local resources, including institutional policies and availability of treatments, technologies, or providers. These guidelines may not be inclusive of all appropriate methods of care for the clinical scenarios described. As new evidences are published, the recommendations contained within may become outdated.

The accompanying remarks describing providing context to the recommendations and containing underlying values and preferences should not be omitted when recommendations from these guidelines are quoted or translated. The recommendations are presented as treatment algorithms for patients with symptomatic varicose veins (Figure 1) and patients with venous ulcers (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Treatment algorithm for patients with symptomatic varicose veins (C2-C4 disease).

Figure 2.

Treatment algorithm for patients with venous ulcer.

Updating guidelines

An update of this guideline may be initiated any time between 2 and 5 years after publication. Updates are prioritized according to the criteria described in the SCAI Publications Committee Manual of Standard Operating Procedures: 2022 Update.42

If an update is warranted but not initiated after 5 years, the guideline is considered retired. If a literature search is performed and the Standards and Guidelines Committee determines that an update is not warranted, the guideline will be modified to reflect the date of the most recent assessment and a revision will be added stating that the recommendations still represent the best guidance available on the topic.

Recommendations

-

1.

In patients who have symptomatic CVD of the lower extremities, should compression therapy be used rather than no compression?

Recommendation 1.1

For patients with symptomatic varicose veins, the SCAI guideline panel suggests compression therapy rather than no compression therapy (conditional recommendation, very low certainty of evidence).

Remarks: Some patients who value more rapid resolution of symptoms and are less concerned with potential complications may prefer interventional alternatives to compression therapy such as sclerotherapy, phlebectomy, or ablation if appropriate. Stronger grades of compression therapy may be more effective.

Summary of the evidence

The guideline panel identified 9 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared use of compression with no therapy,45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52 although the primary outcome was generally wound healing in patients with venous ulcers rather than symptomatic varicose veins. Three RCTs measured discomfort according to varying numerical rating scales, and 3 reported adverse events, as well. Quality of life was reported in 2 of the studies, and edema was reported in 1.

Benefits, harms, and burden

In patients with symptomatic varicose veins, compression may reduce discomfort (standard mean difference, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.87-0.49), which studies measured using a numerical rating scale from 0 or 1 (least pain) to 10 (most pain). Compression may also reduce volume of edema (mean difference [MD], 0.21 L; 95% CI, 0.29-0.12) and improve QoL (MD, 6.87 points lower; 95% CI, 13.1-0.64 points lower) assessed with the Charing Cross Venous Ulcer Questionnaire from 0 (best QoL) to 100 (worst QoL).

Compression hosiery may have little to no effect on wound complications, but the evidence is very uncertain. Three RCTs reported no clinically meaningful increase in adverse events in patients using compression therapy (risk ratio [RR], 0.98; 95% CI, 0.25-3.80). The panel discussed the potential for limb ischemia with compression in patients with advanced peripheral artery disease (PAD); however, there was agreement that this risk is negligible.

Other considerations

A common challenge with compression therapy is nonadherence due to discomfort and inability to apply (don) and remove (doff).53 This can be exacerbated by obesity, pregnancy, joint disease, frailty, and the lack of flexibility. In addition, within the US, compression hosiery and donning devices are typically not reimbursed by health insurance. Payers are encouraged to cover donning devices to improve access to compression therapy. Some patients may prefer alternative options to compression therapy such as sclerotherapy, phlebectomy, or ablation if appropriate.

Conclusions and research needs for this recommendation

Compression therapy is suggested for symptom and edema relief in CVD of the lower extremities. Adherence is a known challenge with compressive therapy. In the future, more comfortable and donnable stockings, better coverage by payors, along with coverage for donning devices would improve utilization.

Recommendation 1.2

For patients with venous ulcers, the SCAI guideline panel recommends compression therapy rather than no compression therapy (strong recommendation, moderate certainty of evidence).

Remarks: Stronger grades of compression therapy may be more effective.

Summary of the evidence

Eight RCTs reported the rate of wound healing at 12 months with use of compression therapy, either by measuring surface area or epithelialization.45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51 Five RCTs measured the time to wound healing at 12 months, also via surface area or epithelialization. The additional outcomes presented previously for Recommendation 1.1 were considered valid for this population, as well.

Benefits, harms, and burden

Compression bandages or stockings were associated with a probable increase in the rate of ulcer healing compared to no compression at 12 months (RR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.41-2.21). In absolute terms, this amounted to 311 more wounds healed per 1000 patients (95% CI, 166-489). Likewise, time to wound healing also showed a likely benefit of compression therapy in data synthesized from 5 RCTs (HR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.59-3.10).

Other considerations

Stronger compression therapy may be more effective for the treatment of venous ulcers. Compression therapy for venous ulcers and comprehensive wound care are feasible and necessary, but supplementary ablative therapy may be needed to achieve faster and higher rates of ulcer healing. Given the evidence that compression probably improves wound healing, particularly for patients with more advanced forms of venous disease, it is prudent that payors support coverage for compression garments.

Conclusions and research needs for this recommendation

Compression therapy is recommended for patients with venous ulcer disease of the lower extremities. In the future, as with patients with symptomatic varicose veins, more comfortable and donnable stockings and better coverage by payors would improve utilization.

-

2.

In adults with symptomatic GSV with or without SSV reflux, should ablation therapy plus conservative management be performed rather than conservative management alone?

Recommendation 2.1

For patients with symptomatic GSV with or without SSV reflux, the SCAI guideline panel suggests ablation therapy plus conservative management rather than conservative management alone (conditional recommendation, low certainty of evidence).

Remarks: Patients without ulcers may place a higher value on avoiding procedural complications and a lower value on uncertain benefits of ablation and may reasonably choose conservative management. Patients with ulcers, with debilitating symptoms, or who failed conservative therapy may prefer ablation therapy. Depending on the functional and anatomic status of the GSV, intervention on the GSV may impact availability for future coronary artery bypass grafting or vascular surgery and may not be suitable for patients with advanced coronary artery disease or PAD. However, the decision to preserve a GSV for potential future bypass would depend on its suitability, and dilated GSVs may not be suitable conduits.

Summary of the evidence

Three studies were identified to inform a comparison of conservative therapy plus GSV ablation (with or without SSV reflux) with conservative therapy alone; 2 of these studies were RCTs,54,55 and 1 was a nonrandomized study (NRS).56

Benefits, harms, and burden

Ablation probably decreases the time to ulcer healing (MD, 31.73 fewer days; 95% CI, 45.1-18.3 fewer days). The evidence also supports a possible increase in ulcer healing rate at 1 year (RR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.88-1.21) and fewer ulcer recurrences at 1 year (RR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.42-1.13) and 2 years (RR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.18-0.81) with ablation therapy compared with those with conservative management alone.

In patients with symptomatic venous insufficiency, ablation therapy may result in improved symptoms at 6 weeks per the venous clinical severity score (VCSS) from 0 (no symptoms) to 30 (severe symptoms; MD, 2.1 lower; 95% CI, 2.99 lower to 1.21 lower). Ablation may also increase QoL at 12 months. One study reported that EQ-ED-5L (from 0 [lowest QoL] to 100 [highest QoL]) was a mean 1.3 higher (95% CI, 2.1 lower to 4.8 higher) among people who received ablation therapy.

One study reported on rates of procedural complications, comparing patients who received early with those who received delayed ablation. As such, both arms reported similar rates of procedure-related adverse events. Of note, the panel considered the magnitude of adverse events to be minimal and fairly transient, ranging from 10.6% (delayed ablation group) to 12.5% (early intervention group). Additionally, nonthermal ablation may be preferred to reduce the risk of nerve injury that can occur, particularly with ablations below the knee and to the SSV.

Other considerations

While out-of-pocket procedural costs may not necessarily be prohibitive for patients, the administrative burden of preauthorization can be significant and may sometimes limit patient accessibility. While most payors cover the cost of ablation therapy, most do not cover compression stockings.

The panel agreed that proper operator training and proctorships for most ablative techniques is generally necessary and accessible. Most centers planning to start ablative therapy procedures are able to overcome logistic or financial barriers to deliver this therapy.

As rates of DVT following ablation are low,54 routine follow-up ultrasound studies conducted to rule out DVT may be unnecessary in low-risk patients undergoing treatment with thermal ablation. Routine postprocedural ultrasound monitoring may be appropriate if foam is used. Less experienced operators may also wish to use routine ultrasound follow-up more liberally.

Patients with ulcer disease are more likely to benefit from ablative therapy upfront, while others should generally consider an initial course of conservative management with compression therapy. A patient-centered discussion of risks and benefits of ablation therapy should be undertaken, particularly in patients with advanced coronary artery disease or PAD.

Among patients with a history of extensive hypersensitivity, operators may opt to avoid cyanoacrylate adhesive. In patients with needle phobia and significant discomfort with injections, operators can choose nonthermal ablative therapy to avoid tumescent anesthetic application. Saphenous segments with significant tortuosity may preclude the insertion of a catheter and be best approached by foam sclerotherapy. With very superficial saphenous veins, where adequate tumescent cannot be applied, nonthermal ablation can be considered to reduce the risk of skin thermal injury. When the below-knee GSV segment needs to be treated, nonthermal techniques may reduce the risk of saphenous nerve injury. Based on recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses, utilization of compression stockings after thermal ablation results in reduced postprocedural pain without affecting procedural outcomes.57,58

There is less clarity on the efficacy of saphenous vein ablation in the setting of concomitant deep vein reflux, with mixed findings in the literature. While the authors agree that patients with combined deep and superficial venous reflux may benefit from ablation of superficial reflux, patient selection criteria are beyond the scope of this analysis.59,60

Conclusions and research needs for this recommendation

The guideline panel determined that there is a net benefit for ablation therapy in addition to compression therapy as opposed to conservative therapy alone in patients with symptomatic GSV reflux with or without SSV reflux. Furthermore, patients with venous ulceration derived the greatest benefit from combined ablative and compression therapy. In patients with symptomatic GSV and/or SSV reflux without ulcers, the risks and benefits should be discussed, and patient values should be considered as part of a shared decision making process.

-

3.

In adults with symptomatic accessory GSV reflux, should ablation therapy plus conservative management be performed rather than conservative management alone?

Recommendation 3.1

For patients with symptomatic accessory GSV reflux, the SCAI guideline panel suggests ablation therapy plus conservative management rather than conservative management alone (conditional recommendation, very low certainty of evidence).

Remarks: Accessory veins encompass normal anatomic variants including the anterior and posterior accessory veins, which were recently renamed, which often run adjacent to the GSV. When accessory veins are associated with pathology such as ulcers or other symptoms, patients may reasonably choose ablation therapy. An accessory GSV sometimes drains pathologic tributary veins that may not be treatable with ablative therapy due to tortuosity or other anatomic considerations. The anterior and posterior accessory GSV were recently renamed anterior and posterior GSV, respectively.

Summary of the evidence

Two RCTs54,55 and 1 NRS56 were identified to address accessory saphenous vein ablation in addition to truncal vein ablations with conservative therapy compared with compression therapy alone. The 2 RCTs assessed time to ulcer healing and ulcer recurrence. The rate of ulcer healing without recurrence was reported in the NRS. Data on symptom improvement and QoL were reported by 1 RCT.

Benefits, harms, and burden

As with GSV reflux with or without SSV reflux, the data from the included studies indicate that ablation therapy probably reduces median days to ulcer healing (MD, 31.73 fewer days; 95% CI, 45.1-18.3). In this instance, the certainty of evidence is lower because 1 of the relevant RCTs included few patients with symptomatic accessory GSV.

Ablation therapy may also reduce the rate of ulcer recurrence at 2 years (RR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.18-0.81), lead to symptom improvement (VCSS MD, 2.1 lower; 95% CI, 2.99-1.21), and improve QoL (EQ-ED-5L MD, 1.3 higher; 95% CI, 2.1-4.8). Evidence for all these benefits is very uncertain. In all 3 studies, patients treated with ablation for accessory veins were subsets of the overall patient population, and many of these patients did eventually receive ablation along with treatment of other segments of superficial reflux and subulcer venous plexus.

Potential adverse events are the same as procedural complications reported in the preceding section. The panel agreed that the impact of these events was minimal and fairly transient and likely related to anatomy or technical approach.

Other considerations

Out-of-pocket procedural costs may not necessarily be prohibitive for patients; reimbursement covers most expenses for the provider. However, preauthorization for these procedures is often required. Although Medicare/Medicaid covers most expenses associated with ablation procedures, they do not cover various methods of compression therapy.

Venous ablation techniques are generally easy to learn for clinicians, and training is accessible. Patients with ulcers benefit the most and tend to choose ablative interventions sooner. Some patients with less severe symptoms and wishing to avoid risk of complications associated with ablation therapy may prefer long-term compression therapy.

More recently, a multisociety position statement proposes referring to the anterior accessory saphenous vein as the anterior saphenous vein. This position statement was made to reflect its clinical significance as a truncal vein.61

Conclusions and research needs for this recommendation

The guideline panel determined there is low to very low certainty of evidence for ablation therapy with conservative management as opposed to conservative management alone in patients with symptomatic accessory saphenous vein reflux. Owing to the possible improvement in time to ulcer healing, the panel suggests ablation therapy with conservative management for these patients rather than conservative management alone. Dedicated studies addressing accessory saphenous reflux only in patients whose other truncal veins have already been treated or are free of reflux are needed.

-

4.

In adults with symptomatic varicose veins, should sclerotherapy plus conservative management be performed rather than conservative management alone?

Recommendation 4.1

For patients with symptomatic varicose veins without truncal vein reflux, the SCAI guideline panel suggests foam sclerotherapy plus conservative management rather than conservative management alone (conditional recommendation, very low certainty of evidence).

Remarks: Most patients with symptomatic varicose veins would prefer sclerotherapy over conservative therapy, but some may not. Hyperpigmentation can occur following sclerotherapy and, in some cases, may be permanent. This may be of lesser concern to patients who place a greater emphasis on symptom relief over cosmetic outcome.

Summary of the evidence

Randomized controlled trials that used either sodium tetradecyl sulfate or polidocanol for the treatment of varicose veins and included a conservative comparator group were screened for study inclusion. The guideline panel considered 3 RCTs that addressed the use of sclerotherapy in patients with symptomatic varicose veins,62, 63, 64 although the studies compared sclerotherapy with placebo rather than with conservative therapy. Additionally, the studies tended to have incomplete reporting, which resulted in serious concerns about risk of bias.

This discussion applies specifically to foam sclerotherapy. Data on liquid sclerotherapy were not analyzed. Additionally, physician-compounded foam using room air vs carbon dioxide in some trials may have altered the efficacy or led to an increased rate of complications.

Benefits, harms, and burden

Two RCTs comparing polidocanol 1% vs placebo found that treatment was associated with fewer residual varicose veins (RR, 0.19; 95% CI, 0.13-0.29) and an improvement in symptoms at 8 weeks (VCSS MD, 3.25 lower; 95% CI, 3.9-2.6).62,63 Sclerotherapy was performed on refluxing truncal veins only, although tributary varicose veins are often treated concurrently given their role in contributing to symptoms of CVD. A third RCT also reported on QoL,64 and the combined treatment groups reported significant improvement in QoL using the VEINES-QOL symptom scale from 0 (worst symptoms) to 50 (better) (MD, 12.41 higher; 95% CI, 9.56-15.26). The panel agreed that sclerotherapy can be very effective in terms of the cosmetic benefit.

The reported rates of adverse events such as DVT (RR, 5.10; 95% CI, 1.30-20.01), phlebitis or thrombophlebitis (RR, 3.12; 95% CI, 1.10-8.83), neurologic complications (RR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.22-4.91), and hemorrhagic complications (RR, 1.83; 95% CI, 0.75-4.47) were higher in the groups that received sclerotherapy. Rates of discoloration, hyperpigmentation, and posttreatment pain were not reported, although such factors may be important to patients.

Other considerations

Overall, the effect of treatment with sclerotherapy may be highly dependent on anatomy. Clinicians should also be aware of the risk of air emboli in patients with known patent foramen ovale. This is an area of controversy since the rare neurologic manifestations associated with foam sclerotherapy may be related to alternative causes (eg, endothelin release). However, caution with patient selection and procedural technique in the setting of known patent foramen ovale is advisable.

Insurance providers generally do not cover sclerotherapy unless saphenous vein reflux has been addressed first. Cosmetic procedures are not covered by most private insurers. Sclerotherapy is generally covered by Medicare/Medicaid.

Sclerotherapy has no significant barrier to entry for providers; however, these procedures can be nuanced, with minor risks. The panel recommends that the operator receive proper training before the initiation of these procedures.

Most patients will find sclerotherapy to be acceptable and tolerable, although some patients may find injections uncomfortable. Veins can become inflamed and tender after sclerotherapy, and the discomfort can last days to weeks, particularly in areas of coagulum formation. Repeat procedures may also be required. Conversely, sclerotherapy is minimally invasive and can be administered in an outpatient setting without the need for sedation or significant capital equipment.

Conclusions and research needs for this recommendation

Sclerotherapy is a minimally invasive technique that can be of benefit for the treatment of symptomatic varicose veins. There is a small risk of complications, and there may be a need for repeat or staged procedures. Additional research is required regarding optimal dosage and injection technique.

Recommendation 4.2

For patients with venous ulcers without truncal vein reflux, the SCAI guideline panel suggests foam sclerotherapy plus conservative management rather than conservative management alone (conditional recommendation, low certainty of evidence).

Remarks: Patients with recurrent ulcers or ulcers that do not respond to conservative management may prefer sclerotherapy. Patients with nonhealing ulcers where mixed etiology is suspected (eg, with concomitant PAD) may benefit from arterial revascularization.

Summary of the evidence

In addition to the 3 aforementioned RCTs comparing foam sclerotherapy to placebo,62, 63, 64 2 additional RCTs reported outcomes in patients with ulceration and provided data on healing of ulcers.54,65

Benefits, harms, and burden

Only 1 RCT from 1973 directly compared sclerotherapy vs compression therapy.65 The treatment group was limited to pregnant women and received 0.5 mL sodium tetradecyl sulfate. They reported an increase in ulcers after treatment in the sclerotherapy group (RR, 13.63; 95% CI, 0.77-240.13). This finding may be attributed to the use of older techniques and has not been replicated in any study since.

More recent RCT data found that sclerotherapy may improve healing time for ulcers (MD, 26 fewer days; 95% CI, 40.69-11.31). The panel agreed that sclerotherapy is likely more beneficial in this patient population than in patients with symptomatic varicose veins.

The data reported for Recommendation 4.1 regarding symptom improvement and QoL apply similarly to the patient population with ulceration.

Other considerations

The same considerations that apply to patients with symptomatic varicose veins apply to patients with venous ulceration. Sclerotherapy would target varicosities associated with the ulcer bed and the venous subulcer plexus.

Conclusions and research needs for this recommendation

Sclerotherapy is suggested for the treatment of venous ulcers. As discussed previously, there is a small risk of complications, and there may be a need for repeat or staged procedures. Additional research is required regarding optimal dosage and injection technique in this patient population.

-

5.

In adults with symptomatic varicose veins (C2-C4), should phlebectomy plus conservative management be performed rather than conservative management alone?

Recommendation 5.1

For patients with symptomatic varicose veins without truncal vein reflux, the SCAI guideline panel suggests phlebectomy plus conservative management rather than conservative management alone (conditional recommendation, very low certainty of evidence).

Remarks: Patients who have recurrent symptomatic varicose veins despite treatment of truncal veins and patients without truncal vein reflux but with symptomatic tributary varicose veins may prefer phlebectomy.

Summary of the evidence

The guideline panel found no studies that directly compared phlebectomy vs conservative management or vs placebo and was unable to quantitatively assess these data. Ultimately, 5 RCTs were included as relevant evidence,66, 67, 68, 69, 70 although the indirectness of the evidence is a very serious concern across all outcomes of interest. Comparison groups in 2 of the RCTs received sclerotherapy and endovenous ablation in 3 RCTs.

Benefits, harms, and burden

Improvement in symptoms has been observed in clinical practice with phlebectomy, although this outcome was not reported in any of the relevant studies. The recurrence rate of symptomatic varicosities was lower after phlebectomy than that with sclerotherapy both at 1 year (2.1% vs 25%) and at 2 years (2.1% vs 37.5%). Data regarding the rates of ulcer recurrence are mixed when comparing phlebectomy vs sclerotherapy, with very low certainty in the evidence. The panel agreed that according to experience, phlebectomy can lead to visual improvement of varicose veins as well as faster resolution of varicosities compared with sclerotherapy.

One RCT suggested that blistering may be a concern with phlebectomy compared with that with other treatment modalities. However, clinicians may be able to avoid thrombophlebitis in large varices, which is a potential adverse event associated with sclerotherapy.66, 67, 68, 69, 70

Other considerations

Phlebectomy is typically an adjunctive treatment, and other potential sources of varices should be addressed first. Phlebectomy is a minimally invasive procedure and often requires only local anesthesia, has a relatively short procedure time, and requires minimal capital equipment. In many cases, phlebectomy can be performed in an outpatient or office setting, with fast recovery time for the patient. Most insurance plans cover the procedure. Appropriate training and expertise to perform phlebectomy is required.

Conclusions and research needs for this recommendation

Owing to the possible reduction in recurrence of symptomatic varicosities and related improvement in symptoms, the panel suggests phlebectomy with conservative management rather than conservative management alone for patients with symptomatic varicose veins. Further research regarding the effectiveness of phlebectomy in patients who are still symptomatic after ablative therapy is needed. There is a lack of evidence comparing phlebectomy performed concomitantly with ablation vs a staged phlebectomy procedure at a later date.

Recommendation 5.2

The SCAI guideline panel makes no recommendation regarding phlebectomy plus conservative management compared with conservative management alone in patients with venous ulcer (no recommendation, knowledge gap).

Summary of the evidence

All evidence assessed by the panel regarding phlebectomy applied to patients with symptomatic varicose veins. Patients with ulceration were not represented in the available data, and the panel opted to formally recognize a knowledge gap for this patient population.

Benefits, harms, and burden

The available evidence was deemed too indirect to extrapolate to patients with venous ulcers. Data regarding ulcer healing were not available.

Conclusions and research needs for this recommendation

Studies in patients with venous ulcer disease are needed to provide data regarding the frequency of ulcer healing and ulcer recurrence.

-

6.

In adults with symptomatic perforator vein reflux, should ablation therapy plus conservative management be performed rather than conservative management alone?

Recommendation 6.1

For patients with ulcer-associated perforator vein reflux, the SCAI guidelines panel suggests ablation therapy in addition to conservative management rather than conservative management alone (conditional recommendation, low certainty of evidence).

Summary of the evidence

Two RCTs and 1 NRS compared perforator vein ablation with conservative therapy in patients with lower extremity ulcer(s).54, 55, 56 Two RCTs also assessed time to ulcer healing and ulcer recurrence. The rate of ulcer healing without recurrence was reported in the NRS. Data on symptom improvement and QoL were reported by 1 of the RCTs.

Benefits, harms, and burden

Ablative therapy probably results in a clinically meaningful reduction in days to ulcer healing (MD, 31.73 fewer days; 95% CI, 45.1-18.3).

Additionally, ablative therapy may increase the rate of ulcer healing at 1 year (RR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.16-2.76), but the evidence is very uncertain. The panel also noted a possible reduction in ulcer recurrences at 1 year (RR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.42-1.13) and 2 years (RR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.18-0.81) with ablation compared with conservative management.

Ablation therapy may result in improved symptoms at 6 weeks (VCSS score MD, 2.1 points lower; 95% CI, 2.94-1.26) and QoL at 12 months (EQ-ED-5L Health Scale MD, 1.1 points higher; 95% CI, 2.4-4.6). The data on procedure-related adverse events reported for Recommendations 2.1 and 3.1 also applies for this patient population.

In all studies, patients with incompetent perforator veins were a subset of the larger patient population with CVD. Additionally, as discussed previously, the 2 RCTs have serious concerns with indirectness because many patients in the comparison groups subsequently received ablation therapy along with treatment of other segments of superficial reflux, as well as the subulcer venous plexus.

Other considerations

Out-of-pocket expenses are not necessarily prohibitive for patients, and reimbursement covers most expenses for health care providers. However, preauthorization is often required, and although Medicare/Medicaid cover most ablation procedures, they do not cover compression therapy.

Venous ablation techniques are generally easy to learn for clinicians, and training is accessible. Patients who place a high value on the possible reduction in time to ulcer healing are more likely to choose ablative interventions.

Conclusions and research needs for this recommendation

The panel determined there is likely benefit to perforator ablation therapy combined with conservative therapy compared with conservative therapy alone in patients with perforator vein reflux associated with ulcers, with low certainty in the evidence. Dedicated studies addressing perforator reflux only in patients whose truncal veins have already been addressed or are free of reflux need to be performed, along with comparison of different modalities for perforator ablation.

Recommendation 6.2

The SCAI guideline panel makes no recommendation regarding patients with symptomatic perforator reflux without associated ulcer(s) (no recommendation, knowledge gap).

Summary of the evidence

No evidence was identified for treatment of symptomatic perforator reflux without ulceration(s).

Benefits, harms, and burden

As reported previously, ablation therapy may result in improved symptoms at 6 weeks and QoL at 12 months. However, these data were exclusively derived from patients with venous ulceration(s), and the panel could not generalize recommendations to patients with lower severity CVD without ulceration(s).

Conclusions and research needs for this recommendation

There is a considerable knowledge gap regarding the use of ablation therapy to treat perforator reflux without associated ulcer(s). Future studies should examine the feasibility and efficacy of treatment of perforator reflux without associated ulcer(s).

-

7.

In patients with symptomatic CVD with severe deep venous stenosis of the iliocaval segment, should venoplasty and/or stenting plus conservative management be performed rather than conservative management alone?

Recommendation 7.1

In patients with symptomatic chronic deep vein obstruction/stenosis, the SCAI guideline panel suggests venoplasty and/or stenting of iliocaval veins plus conservative management rather than conservative management alone (conditional recommendation, low certainty of evidence).

Remarks: Appropriate patient selection based on clinical and anatomical factors and technical expertise are important to derive benefit and minimize complications from iliocaval stenting. Patients may reasonably decline venoplasty or stenting if they place a higher value on avoiding potential procedure-related adverse events and a lower value on potential reduction of discomfort or improvement of symptoms. Diagnosis and vessel sizing can be aided with the use of intravascular imaging.

Summary of the evidence

In patients with symptomatic Iliocaval obstruction (such as postthrombotic lesions, nonthrombotic iliac vein lesions, and May-Thurner syndrome), stenting in selective cases may be appropriate. Much of the available literature is observational. RCTs are limited to 1 small study conducted in 207 patients with C3-C6 disease with a ≥50% iliac vein obstruction on intravascular ultrasound (IVUS).71 Of those 207 patients, only 51 limbs were eligible and had anatomy suitable for randomization. The results were consistent with several NRSs, reporting on procedural success and symptom improvement over an 11.8 months (mean) follow-up period.

The panel discussed whether to develop separate recommendations for patients with postthrombotic vs those without postthrombotic disease. The RCT combines these groups, and thus, such distinctions could not be made.

Benefits, harms, and burden

The single RCT was conducted in 207 patients who had already failed a concerted trial of conservative therapy, which is commonly used as an initial therapy. The results demonstrated a possible increase in wound healing rates (90% in the stent group vs 40% for conservative therapy) and possible improvement in symptoms (VCSS MD, 7 lower after stenting vs 1 lower in the group receiving usual care). Likewise, iliocaval stenting may lead to improved QoL as assessed on a scale of 0 (complete disability) to 100 (least disability) by the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (median 180-day score, 85.0 vs 59.8 for best medical therapy).

Longer-term benefits and harms were not measured in the studies; case reports have noted very serious adverse events such as embolization from incorrectly placed or undersized stents and restenosis/occlusion. Adverse periprocedural events reported in the RCT included transient back pain (25%) and access site hematoma (4%). There is overall consensus that the decision for iliocaval stenting is based on the presence of at least 50% lumen area stenosis by IVUS accompanied by the presence of severe, lifestyle-limiting clinical symptoms.36,72,73

It is imperative to ascertain that the technical aspects of the procedure are optimized in order to minimize potential complications (eg, stent migration). Use of imaging with IVUS is strongly encouraged to achieve appropriate stent sizing, expansion, and wall apposition. Patients who have been fasted before invasive venography may benefit from intravenous prehydration before venography and IVUS to help ensure optimal lesion assessment and stent sizing.74

Rarely, stent migration can occur, which can be a devastating complication of iliocaval stenting, requiring endovascular intervention or open surgery (including sternotomy) to address.75 Risk factors for stent migration appear to include stents with smaller diameter and shorter stents (≤60.0 mm in length).76

Other considerations

The cost of treatment may differ significantly based on the setting; reimbursement in an office-based laboratory may not cover all expenses for the health care provider. Medicare/Medicaid generally cover the costs of the procedure, although some challenges have been observed in Medicare Advantage coverage based on procedural setting. Coverage policies are siloed, and sites of service are affected differently. There is an operator-dependent learning curve, and the clinical and technical expertise of the operator may have a significant impact on procedural outcomes.

The panel agreed that the procedure is generally acceptable to patients, feasible to perform for clinicians, and safety has improved in recent years. Indications for the procedure are not universally agreed upon and should be individualized based on clinical presentation and severity of stenosis. Shared decision making regarding the balance of short-term and mid-term symptom improvement and QoL vs the low certainty regarding the potential longer-term adverse events due to stent occlusion is important. The panel felt that there can be an overuse of iliocaval venous stenting procedures in patients with questionable indication; programmatic quality assurance measures involving peer institutional/office-based laboratory case reviews should be implemented. Appropriately selected patients with advanced C4-C6 disease are more likely to benefit from iliocaval stenting than patients with C2-C3 disease.

In interventions for postthrombotic obstruction, better patency and outcomes would be expected if both the inflow and outflow diseases are treated. However, the panel cautions against stenting the common femoral vein below the profunda, as jailing this vessel may compromise this important conduit.

Conclusions and research needs for this recommendation

Iliocaval stenting may offer short-term to mid-term symptom and QoL improvement for patients in which conservative management has failed. Additional RCTs with longer follow-up and focus on a subgroup of compressive CVD from thrombotic disease will be required to clarify future recommendations. Furthermore, in patients with symptomatic combined deep vein obstruction and superficial venous reflux, there are limited quality data regarding the optimal approach and sequence of intervention.

-

8.

In patients with symptomatic CVD with deep venous obstruction/stenosis of the femoral veins, should venoplasty with or without stenting plus conservative management be performed rather than conservative therapy alone?

Recommendation 8.1

The SCAI guideline panel makes no recommendation regarding venoplasty with or without stenting plus conservative management compared with conservative management alone in patients with postthrombotic chronic isolated femoral vein disease (no recommendation, knowledge gap).

Summary of the evidence

Evidence regarding femoral vein intervention in patients with postthrombotic syndrome (PTS) is very limited and generally includes femoral vein intervention performed concomitantly with iliac or iliocaval stenting. The panel reviewed 2 NRSs in which femoral venoplasty was performed in addition to adjacent iliac vein stenting.77,78 One NRS assessed the impact of endovascular iliofemoral venous stenting vs elastic compression at 30 to 40 mm Hg in patients with PTS.77 The other single-center NRS evaluated the feasibility and efficacy of endovascular stenting in patients with PTS.78

Benefits, harms, and burden

Patients undergoing endovascular procedures were not compared directly with patients receiving conservative therapy alone, and the data from the 2 studies could not be synthesized quantitatively. The panel felt that the reported outcomes of symptom improvement and QoL were insufficient to support a recommendation for those with isolated femoral vein disease.

Conclusions and research needs for this recommendation

The panel recognized femoral venoplasty with or without stenting as a knowledge gap and, therefore, chose not to provide any recommendation for balloon venoplasty and cautions against stenting due to concerns of femoral vein reocclusion and lack of efficacy.

Further studies are needed to evaluate the value of venoplasty with or without stenting in this population to improve venous flow and symptoms. Postthrombotic narrowing of the common femoral vein is another area for further investigation.

Recommendation 8.2

The SCAI guideline panel makes no recommendation regarding venoplasty with or without stenting plus conservative management compared with conservative management alone in patients with postthrombotic chronic isolated common femoral vein disease (no recommendation, knowledge gap).

Summary of the evidence

In patients with PTS, evidence regarding common femoral vein venoplasty with or without stenting is likewise very limited and consists of study populations in which common femoral vein venoplasty with or without stenting is performed concomitantly with iliac or iliocaval stenting.77,78 Because common femoral vein venoplasty with or without stenting has been reported more frequently in the literature than femoral vein intervention, the panel felt that it should be given a separate consideration from an isolated femoral vein intervention.

Benefits, harms, and burden

The available data on symptom improvement and QoL were sparse and not synthesized quantitatively; the panel determined that the evidence is insufficient to support a recommendation for those with postthrombotic chronic isolated common femoral vein disease.

Conclusions and research needs for this recommendation

The panel recognized common femoral vein venoplasty with or without stenting as a knowledge gap and decided not to provide any recommendation. A randomized trial evaluating venoplasty and stenting of the common femoral vein in patients with PTS could provide useful insight for clinicians.

Discussion

These guidelines aim to add clarity and direction to a field that is commonly guided by observational and retrospective studies. With the increased prevalence of venous procedures in recent years, SCAI leadership recognized the need for recommendations to aid health care providers, interventional cardiologists, patients, and payors in making choices about different management strategies.

To assure the highest level of transparency, the SCAI guideline panel, consisting of experienced methodologists and experts in the fields of venous disease, used the GRADE approach to develop a series of clinical questions and outcomes. Each clinical question was subjected to a prioritization process and was addressed by a technical review panel. The technical review findings informed judgments by the guideline panel to develop each recommendation. The strength of the recommendation was driven by the certainty of the evidence for patient-centered benefits and harms, as well as systematic consideration of values, resource use, acceptability, feasibility, and equity.

Data from 9 RCTs that evaluated ulcer healing and 3 trials that evaluated leg discomfort supported the panel’s decision to suggest compression therapy rather than no compression for patients with symptomatic varicose veins. For patients with venous ulcer disease, the panel made a strong recommendation for compression therapy. Stronger grades of compression therapy may be preferable in ulcer disease.

The panel agreed on a conditional recommendation for ablation therapy of the GSV due to faster and more complete ulcer healing rates, with low adverse event rates. Nonthermal ablation of below the knee segments could reduce the risk of nerve injury. While data on the accessory GSV and perforator vein were more indirect, leading to a lower certainty in the evidence, the panel agreed on conditional recommendations in favor of ablation therapy in these populations. If present, saphenous vein reflux should be ablated first. There were no data to support a recommendation for or against perforator ablation for nonulcer disease; therefore, the panel recognized a knowledge gap in that population.

For patients with symptomatic varicose veins in the absence of truncal vein reflux, as well as those who still have ongoing symptoms despite ablation of truncal vein reflux, the panel agreed that sclerotherapy may lead to improvement in symptoms and QoL. However, there are additional risks of procedure-related adverse events with sclerotherapy compared with conservative management alone, including DVT and thrombophlebitis. This led to a conditional recommendation in favor of foam sclerotherapy for patients with symptomatic varicose veins without truncal vein reflux.

The panel found no direct data comparing phlebectomy vs conservative management in patients with symptomatic varicose veins, but the potential for faster resolution of varicose veins and lower recurrence rates in patients led to a conditional recommendation in favor of phlebectomy despite the indirectness of the study populations. The lack of data for phlebectomy for venous ulcer disease was acknowledged, and thus, no recommendation was given.

Despite an increase in iliocaval venous stenting for obstructive disease over the past 2 decades, the panel was not able to find prospective long-term follow-up data. One small RCT found improved symptoms among patients with C3-C6 disease following stenting. As both patients with PTS and those with nonthrombotic syndrome were included, the panel suggested venoplasty or stenting of iliocaval veins rather than conservative management alone in selected severely symptomatic patients but could not offer separate recommendations for patients with postthrombotic disease vs those without.

There were very little data on femoral vein intervention in patients with postthrombotic disease, which prompted the panel to recognize venoplasty in these patients as a knowledge gap. While intervention to the common femoral vein in postthrombotic disease has been reported more commonly within the literature, insufficient evidence prompted the panel to also recognize common femoral vein postthrombotic disease intervention as a knowledge gap.

These guidelines represent the most comprehensive effort by SCAI to synthesize and interpret the evidence regarding CVD interventions in a variety of clinical scenarios. The panel has also formulated algorithms on the management for C2-C4 and ulcer disease.

For most of the prioritized scenarios discussed, evidence regarding the intervention carries some degree of uncertainty. The panel recognizes that RCTs are needed to provide higher certainty in the potential consequences of treatment decisions for many of these patients. The recommendations of the panel are based on available data, which are sometimes indirect, imprecise, or at some risk of bias. These limitations are described in further detail in the accompanying technical review.41 The decision to perform a venous intervention on any patient for any clinical scenario should be highly individualized and should include a comprehensive patient-focused discussion of their needs and values. The panel hopes that future clinical trials will support updates to these guidelines.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sanjum Sethi, MD, MPH, FSCAI, and Jun Li, MD, FSCAI, for peer reviewing the manuscript.

Peer review statement

Sahil A. Parikh is an Associate Editor for JSCAI. As an author of this guidelines document, he participated in drafting and review of the guidelines and in all pre-submission responses to reviewers; however, after submission, he had no involvement in the peer-review process or decision for publication.

Declaration of competing interest

Jeffrey G. Carr discloses serving on the speaker's bureau and as a consultant for BD. Eric A. Secemsky discloses serving on the advisory board for Boston Scientific and Medtronic, the speaker's bureau for BD, Boston Scientific, Cook, and Medtronic, and consulting for BD, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. Karem C. Harth discloses serving as a consultant for Boston Scientific, Cook, and Medtronic. All other authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding sources

Development of these guidelines was wholly funded by SCAI, a nonprofit medical specialty society that represents interventional cardiologists.

Footnotes

To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of the Journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions at 10.1016/j.jscai.2025.103729.

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Graham R., Mancher M., Wolman D.M., Greenfield S., Steinberg E., Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines, Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine . National Academies Press; 2011. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qaseem A., Forland F., Macbeth F., et al. Guidelines International Network: toward international standards for clinical practice guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(7):525. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-7-201204030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schünemann H.J., Wiercioch W., Etxeandia I., et al. Guidelines 2.0: systematic development of a comprehensive checklist for a successful guideline enterprise. CMAJ. 2014;186(3):E123–E142. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guyatt G.H., Oxman A.D., Vist G.E., et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guyatt G., Oxman A.D., Akl E.A., et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lurie F. Anatomical extent of venous reflux. Cardiol Ther. 2020;9(2):215–218. doi: 10.1007/s40119-020-00182-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eberhardt R.T., Raffetto J.D. Chronic venous insufficiency. Circulation. 2014;130(4):333–346. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meissner M.H., Gloviczki P., Bergan J., et al. Primary chronic venous disorders. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46(suppl S):S54–S67. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pocock E.S., Alsaigh T., Mazor R., Schmid-Schönbein G.W. Cellular and molecular basis of venous insufficiency. Vasc Cell. 2014;6(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s13221-014-0024-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mansilha A., Sousa J. Pathophysiological mechanisms of chronic venous disease and implications for venoactive drug therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(6):1669. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pannier F., Rabe E. Progression in venous pathology. Phlebology. 2015;30(suppl 1):95–97. doi: 10.1177/0268355514568847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pappas P.J., Lakhanpal S., Nguyen K.Q., Vanjara R. The Center for Vein Restoration Study on presenting symptoms, treatment modalities, and outcomes in Medicare-eligible patients with chronic venous disorders. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2018;6(1):13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2017.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wrona M., Jöckel K.H., Pannier F., Bock E., Hoffmann B., Rabe E. Association of venous disorders with leg symptoms: results from the Bonn Vein Study 1. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;50(3):360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans C.J., Fowkes F.G., Ruckley C.V., Lee A.J. Prevalence of varicose veins and chronic venous insufficiency in men and women in the general population: Edinburgh Vein Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53(3):149–153. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.3.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Criqui M.H., Jamosmos M., Fronek A., et al. Chronic venous disease in an ethnically diverse population: the San Diego population study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(5):448–456. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carradice D., Mazari F.A., Samuel N., Allgar V., Hatfield J., Chetter I.C. Modelling the effect of venous disease on quality of life. Br J Surg. 2011;98(8):1089–1098. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beebe-Dimmer J.L., Pfeifer J.R., Engle J.S., Schottenfeld D. The epidemiology of chronic venous insufficiency and varicose veins. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15(3):175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.da Silva A., Widmer L.K., Martin H., Mall T., Glaus L., Schneider M. Varicose veins and chronic venous insufficiency. Vasa. 1974;3(2):118–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelzén O., Bergqvist D., Lindhagen A. Venous and non-venous leg ulcers: clinical history and appearance in a population study. Br J Surg. 1994;81(2):182–187. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robertson L., Evans C., Fowkes F.G.R. Epidemiology of chronic venous disease. Phlebol J Venous Dis. 2008;23(3):103–111. doi: 10.1258/phleb.2007.007061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robertson L.A., Evans C.J., Lee A.J., Allan P.L., Ruckley C.V., Fowkes F.G.R. Incidence and risk factors for venous reflux in the general population: Edinburgh Vein Study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2014;48(2):208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2014.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salim S., Machin M., Patterson B.O., Onida S., Davies A.H. Global epidemiology of chronic venous disease: a systematic review with pooled prevalence analysis. Ann Surg. 2021;274(6):971–976. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chi Y.W., Raffetto J.D. Venous leg ulceration pathophysiology and evidence based treatment. Vasc Med. 2015;20(2):168–181. doi: 10.1177/1358863X14568677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]