Abstract

Individual differences in executive functions (or executive control abilities) predict variation in creative thinking ability. Relatedly, propensity for mind-wandering—or task unrelated thought—has been gaining attention among creativity scholars, but its effects on creativity remain unclear. The present study conceptually replicates and extends recent laboratory and experience-sampling work to assess the links between individual differences in divergent thinking, executive control abilities (working memory capacity and attention control), and measures of mind-wandering collected in both contexts. SEM analyses indicated that executive control factors weakly predicted divergent thinking scores, mainly due to their role in filtering out uncreative ideas rather than generating highly novel ones. Lab-based measures of mind-wandering didn’t significantly correlate with overall creative thinking, challenging the idea that mind-wandering uniformly enhances creativity, but they were positively linked to highly creative divergent thinking scores. Daily-life measures of mind-wandering, meanwhile, did not provide stronger predictive insights into creative thinking than lab measures. Finally, exploratory analyses found that divergent thinking scores based on highly creative responses were positively associated with episodes of more fantastical, unrealistic mind-wandering, or “daydreaming.” We end our investigation with a call for greater theoretical precision and some hypotheses to guide future work. [Data, scripts, and preprint: https://osf.io/at5gx/]

Keywords: creativity, divergent thinking, mind wandering, executive control, individual differences, working memory capacity, attention control

Demands for creative solutions to the challenges of modern life are of increasing interest to policy makers, business professionals, and scientists (e.g., Gottschling et al., 2021; Sternberg, 2021; Wai & Lovett, 2021). Moreover, at the individual level, people’s ability to respond to situations in novel and useful ways enables successful everyday problem solving and is likely instrumental to living a healthy and fulfilling life (Conner et al., 2018). Some people are nonetheless much more successful than others with creative and novel idea generation, or “divergent thinking,” whether it’s in the arts, science, business, or other fields.

Recent evidence suggests that individual differences in executive functioning related to attention control and working memory might predict normal variation in creative-thinking ability (Benedek et al., 2014; Palmiero et al. 2022). Propensity for mind-wandering—often operationalized as task-unrelated thought (TUT)—has also emerged as a related variable of interest among creativity researchers, but the potential benefits versus harms of mind-wandering to divergent thinking have been the subject of debate. The present study conceptually replicates and extends recent laboratory and ecological work (see especially Frith et al., 2021; Zeitlen et al., 2022) assessing the individual-differences associations among divergent thinking (measured by “alternative uses” laboratory tasks), executive control abilities (measured by performance tasks of attention and working memory), and measures of TUT propensity collected in the laboratory and during daily-life activities using experience sampling.

Executive Control and Creative Cognition

In a recent narrative review on divergent thinking and core executive functions, Palmiero et al. (2022) described executive functioning as “a multidimensional construct, defined as a family of top-down cognitive abilities” (p. 342; see also Miyake & Friedman, 2012). Executive control of attention, or attention control, comprises the processes by which people direct and regulate their conscious focus to solve novel problems, overcome habitual or inappropriate responses, and ignore distracting information (e.g., Burgoyne & Engle, 2020; Kane et al., 2016; Mashburn et al., in press; Zelazo et al., 2004). Working memory capacity (WMC) is a related and partially overlapping construct encompassing the memorial and attentional processes involved in maintaining and updating information for ready access during complex cognitive activities (e.g., Engle, 2002; Shipstead et al., 2014; Stedron et al., 2005; Unsworth & Spillers, 2010).

Given that divergent thinking has typically been measured in this literature with alternative-uses tasks, in which subjects generate novel and creative uses for a particular object (e.g., a brick), attention control and WMC might benefit performance in multiple ways (e.g., Beaty & Silvia, 2012; De Dreu et al., 2012; Palmiero et al. 2022; Zabelina et al., 2019). Attention control might support divergent thinking by preventing common uses of the target object from (repeatedly) coming to mind, by facilitating shifting of focus away from recalled common uses and toward more productive mental-search strategies, or simply by keeping environmental distractions or irrelevant thoughts from derailing ongoing idea generation. WMC might be used during divergent thinking to maintain partial solutions to the problem during idea manipulation, to retrieve relevant information or strategies from long-term memory, to enable reflection on the quality of retrieved ideas, or simply to keep the goal of the task accessible enough to exert control over thought and behavior. Although WMC and attention control measures frequently correlate positively with divergent thinking performance (e.g., Benedek et al., 2014; De Dreu et al., 2012; Frith et al., 2021; Oberauer et al., 2008), null and mixed findings have also been reported (e.g., Dygert & Jarosz, 2020; Lin & Lien, 2013; Smeekens & Kane, 2016), suggesting that executive processes might contribute to some components of creative cognition but not others.

Based on the claimed positive association between executive control and divergent thinking, it may be surprising that some theorists suggest that mind-wandering may also support divergent thinking. Mind-wandering propensity typically correlates negatively with attention control and WMC: People who score higher on tests of executive control typically report fewer TUTs during laboratory tasks and challenging daily-life activities (see Kane & McVay, 2012). If good executive control typically leads to less mind-wandering, then how might TUTs lead to better divergent thinking? Anecdotes suggest that people sometimes come to highly creative solutions to longstanding problems suddenly, without apparent effort, at moments when they were not even attempting to solve the problem (e.g., Mullis, 1998; Poincaré, 1910). Such reports suggest that executive control may be helpful during only some stages of divergent thinking, whereas mind-wandering (and a lack of control) may be helpful during others.

How Cognitive Theories of Creativity Might Accommodate Mind-Wandering

The debate over whether mind-wandering might facilitate creative ideation is rooted not just in anecdotes, but also in theorized cognitive mechanisms of creativity. Early theories of creativity, such as the associative theory, defined individual differences in creative cognition according to the organization of concepts, from conceptually close to conceptually distant, in a person’s semantic knowledge (Mednick, 1962). In this view, the semantic organization of knowledge serves as the foundation for creative idea generation, because it facilitates making novel associations between seemingly unrelated or conceptually distant concepts, including drawing concepts from different domains or fields. Individual differences in semantic organization also lead to variations in three cognitive processes: priming (what is at the forefront of one’s conscious thought), retrieval (what can be accessed quickly from long-term memory), and flexible thinking (how easy it is to shift between perspectives or concepts). When concepts are efficiently organized in semantic knowledge, creative ability flourishes: Ideas become more accessible, readily connectable, and efficient to sort through.

People who differ in creative ability should also show differences in semantic network organization. First, the readily available concepts that come to mind for people with lower creative ability should reflect more limited associations between ideas that are more repetitive, conventional, and predictable than are those for people with higher creative ability. Then, when ideas must be retrieved quickly, people lower in creativity should struggle more to shift through their semantic space to produce viable ideas and to navigate around mental blocks to explore alternative paths; people higher in creativity should demonstrate more fluent idea generation and overcome impasses more readily. Finally, flexible thinking should be hindered in less creative people because their semantic networks are more rigid, thus frustrating the adaptation to novel problems, constraining idea generation within conventional boundaries, and blocking the ability to shift between disparate categories and blend ideas across domains. The semantic networks of highly creative people, in contrast, should allow for adaptability, conceptual blending, and freedom from conventional limitations.

Many studies have tested the predictions of Mednick’s associative theory. Brown (1973) and Mednick (1964), for example, initially studied associative processes through performance on word-association tasks: The disparity in learning between strong and weak word-association pairs was less pronounced in more creative than less creative people. Relatedly, associative abilities (measured, for example, using word-association tasks) account for about half of the individual-differences variance in divergent thinking performance (Benedek et al., 2012). Associative theory has been most recently examined through modeling connectivity differences in semantic-network path structures between people of higher versus lower creative ability (for a review, see Beaty & Kenett, 2023). For example, when modeling the path lengths and clustering of relatedness judgments of semantic concepts, the semantic associations in more creative subjects show shorter path lengths between unrelated concepts and less rigid semantic memory networks (Benedek et al., 2017; Christensen et al., 2018; Kenett et al., 2014; Kenett & Faust, 2019; Rossmann & Fink, 2010). Extending from Mednick’s (1962) associative theory and these more recent advancements, it could be hypothesized that TUTs aid creative cognition by allowing (or encouraging) attention to flow to more distantly related concepts in semantic memory.

More recently, theories of creative cognition have put executive processes, viewed broadly, at the center of creative thinking (Barr et al., 2015; Beaty et al., 2016; Preiss, 2022). In this approach, top-down cognitive control fosters creativity via many pathways, such as enabling complex idea generation strategies, inhibiting obvious ideas that come to mind quickly, and selectively searching and retrieving knowledge, among others (e.g., Beaty et al., 2016; Benedek et al., 2012; Silvia, 2015). These high-level executive processes interact with low-level associative processes, so this approach sees executive and associative aspects of creative thought as integrated rather than opposed (Beaty & Kenett, 2023; Beaty et al., 2016). As a result, this approach doesn’t offer any additional, straightforward prediction about how mind-wandering might affect creative thought, although it would emphasize the importance of attention control in guiding how people generate, judge, and refine their creative ideas that were produced via associated processes.

Mixed Empirical Findings on TUTs and Divergent Thinking

Creative thought involves a complex interplay of associative and controlled-attentional processes (Beaty & Kenett, 2023; Benedek et al., 2012), so mind-wandering could be expected to facilitate creative cognition, at least under some situations or during some stages of processing. Below we review relevant studies that assessed TUT rates using experience-sampling probes during ongoing tasks or activities (rather than using retrospective questionnaire assessments of mind-wandering propensity) and measured divergent thinking performance using alternative-uses-like tasks.

Modern research on the ostensible connection between TUTs and divergent thinking traces to a widely cited study by Baird et al. (2012), who used an incubation design to assess whether momentary mind-wandering might facilitate creative thinking. Incubation effects are studied in the laboratory by having experimental subjects stop working on a creative problem to briefly switch to another task before returning to the initial creative problem; “incubation” is said to occur if creative output increases post-switch, relative to post-switch performance of control subjects who do not take an incubation break. Of relevance to Baird et al. (2012), a meta-analysis had found that incubation-break tasks that imposed a low cognitive load produced larger incubation benefits than did higher-load (more difficult) tasks or rest breaks without a task (Sio & Ormerod, 2009); as well, the mind-wandering literature had indicated that people report more TUTs during easier than harder tasks (see Smallwood & Schooler, 2006).

Baird et al. (2012) tested whether divergent thinking would benefit from the TUTs elicited by low-load incubation tasks. Subjects first generated novel uses for two objects for 2 min each (e.g., a brick, a paperclip) and then were randomized into one of four conditions: no incubation break, incubation rest break (with no task), incubation with low-load task, incubation with high-load task; all but the no-break group took a 12 min incubation break, after which they completed a questionnaire about their TUTs during the break. All groups then generated novel uses for the two initial objects and two additional objects (e.g., a knife, a tire) in a random order for 2 min each. Subjects in the low-load group reported more TUTs during incubation than did subjects in the high-load group, and they showed a greater increase in creative uses generated for the repeated objects than did all the other groups (i.e., they produced more unique responses not given by other subjects). Mind-wandering during incubation therefore appeared to improve creative thinking.

Subsequent research identified problems with the Baird et al. (2012) conclusions and has mostly failed to replicate the findings. Smeekens and Kane (2016), for example, argued that the uniqueness score for divergent thinking from Baird et al. (2012) had been criticized as a poor measure of creativity (Silvia et al., 2008), that retrospective post-incubation TUT reports were prone to error, and that the correlated outcomes of TUT reports and divergent-thinking scores could not support causal claims (i.e., that increased mind-wandering caused increased creativity). In three studies, Smeekens and Kane (2016) probed for TUTs during several different incubation tasks, rated divergent thinking output for creativity, and failed to find a positive correlation between incubation TUT rates and post-incubation creativity scores (or pre-to-post improvement in scores).

Teng and Lien (2022) similarly reported no association between incubation TUT rate and pre-to-post incubation increase in uniqueness of divergent thinking responses, whereas Yamoaka and Yukawa (2019) found no difference in the uniqueness or creativity of post-incubation divergent thinking between subjects who reported more versus fewer TUTs on a post-incubation questionnaire. Steindorf et al. (2020) attempted to conceptually replicate aspects of both Baird et al. (2012) and Smeekens and Kane (2016) and found that low-load incubation did not increase divergent-thinking scores compared to no incubation, and neither incubation TUT rate nor post-incubation retrospective TUT reports correlated with divergent-thinking scores. Finally, Murray et al. (2021) more directly replicated the Baird et al. (2012) method and, although they found that low-load incubation increased TUT rates relative to high-load incubation, it did not lead more creative divergent thinking (and subjects with higher TUT rates were not more creative than those with lower TUT rates).

Studies taking less similar methodological approaches have also yielded negative results. In an incubation context, Yang and Wu (2022) had subjects complete a 60 min incubation period between divergent-thinking attempts, but half the subjects had their mind-wandering minimized by presenting them with punishing visual and audio feedback following incubation-task performance errors and TUT reports. Although the punished subjects reported fewer TUTs than controls, the two group’s divergent-thinking responses did not differ in uniqueness. Outside of the incubation context, Hao et al. (2015) measured TUTs during a 20-min divergent thinking task, and Frith et al. (2021) measured TUT rates in two stand-alone tasks, and both correlated TUT rates with divergent-thinking performance. Hao et al. (2015) found that subjects reporting fewer TUTs produced significantly more original divergent-thinking responses than did those reporting more TUTs, and Frith et al. (2021) similarly found a non-significant negative correlation between TUT rate and creativity of divergent thinking (whereas attention-control performance measures correlated significantly positively with creativity).

Going Beyond Laboratory TUT Rates in Exploring Divergent Thinking?

The totality of empirical evidence does not favor a positive association between the propensity for TUTs and creative responding in divergent thinking tasks. Does this indicate that mind-wandering is unrelated to creative thinking? Not necessarily. Mind-wandering is a complex and multi-faceted construct that may be operationalized in many ways and studied in many contexts (see Christoff et al., 2016; Seli et al. 2018a, 2018b). Perhaps operationalizing mind-wandering as reports of TUTs during laboratory tasks is not ideal for creativity research (Christoff et al., 2016); that is, maybe only some varieties of mind-wandering—such as more freely flowing, unconstrained thoughts—facilitate creativity (Girn et al., 2020; Irving et al., 2022). Or, maybe laboratory contexts that require concentrated focus aren’t sensitive to the kinds of positive-constructive mind-wandering experiences that might support creative cognition (e.g., Agnoli et al., 2018; McMillan et al., 2013). Indeed, some researchers argue that the extent to which thoughts are freely moving and unconstrained in form, rather than off-task in content, should determine their association with creativity (e.g., Irving et al., 2022; Murray et al., 2021). Others suggest that the extent to which thoughts are fantastical, playful, and imaginative in content, rather than simply off-task and potentially mundane in content, should determine their association with divergent thinking (e.g., Zedelius et al., 2020). Finally, given that laboratory and daily-life assessments of mind-wandering may have different causes and correlates (Kane et al., 2017), still others have asked whether ecologically valid assessments of mind-wandering during everyday activities might shed more light on creative thinking than do TUT rates derived from short laboratory tasks that are unusually challenging or boring (e.g., Gable et al., 2019; Zedelius et al., 2020; Zeitlen et al., 2022).

In fact, alternative conceptions of mind-wandering, beyond TUT, have led to more positive results (although not universally positive). Teng and Lien (2022), for example, found that post-incubation increases in one dimension of divergent-thinking performance—a flexibility score reflecting the extent to which subjects generated unusual uses from more distinct semantic categories—correlated positively with participants’ post-incubation ratings of how diverse their mind-wandering content had been during incubation (mind-wandering diversity was not correlated, however, with divergent thinking originality ratings). As well, their subjects reported whether each of their TUTs were intentional, and the proportion of intentional TUTs correlated positively with post-incubation increase in the originality of divergent-thinking responses.

In terms of conceptualizing mind-wandering as freely moving thought, several recent studies have assessed its prediction of creative cognition, with inconsistent results. Irving and colleagues (2022) examined the association of freely moving thoughts recorded during boring or engaging incubation periods with divergent thinking. During a 3 min incubation period, freely moving thought (measured from three thought probes) predicted the number of divergent-thinking ideas generated after the engaging incubation task, but not their originality. No such effects were seen following a boring incubation task. A. P. Smith et al. (2022) examined freely moving thought rates in three contexts: during incubation, during divergent-thinking trials, or during a stand-alone task. They found that rates of freely moving thought correlated negatively with divergent-thinking creativity ratings, regardless of the measurement context. Only the rate of switching between freely moving and constrained thoughts yielded a weak, positive correlation with divergent thinking creativity. Finally, Raffaelli et al. (2023) examined freely moving thought during think-aloud rest periods, in addition to during a divergent thinking task; specifically, raters coded subjects’ spoken-aloud thoughts during rest for how often the content transitioned, and at the end of the rest period (and at the end of divergent thinking), subjects rated how freely moving their thoughts had been. Both the number of coded content transitions during rest and the post-rest freely-moving ratings correlated positively with originality scores in divergent thinking. However, this study had a small sample size for correlational analyses (ns < 80 for most analyses), and freely moving thoughts during the divergent-thinking task itself correlated as strongly with divergent-thinking performance as did freely moving thoughts during rest, suggesting that “mind-wandering” may not have driven these findings. Taken together, then, the limited literature on freely moving thought might suggest some connection of mind-wandering to creativity, but findings are mixed.

Finally, we consider research on mind-wandering and creativity using daily-life experience-sampling or diary assessments. In a daily-diary study of physicists and professional writers, Gable et al. (2019) examined the frequency of creative idea generation during episodes of mind-wandering compared to periods of on-task activity. Although participants reported that nearly a fifth of their creative ideas were generated while thinking about something else (i.e., mind-wandering) and while not working on problem-solving, most creative ideas were generated while on-task (i.e., while intentionally working on and thinking about the problem). Further, ideas generated during mind-wandering weren’t judged to be significantly more creative or important than were ideas generated during other times (only ideas generated during “Aha!” experiences were). Zedelius and colleagues (2020) had undergraduate subjects complete, in the lab, two divergent thinking tasks and a trait questionnaire about their engagement in six different types of daydreaming, as well as providing daily-diary self-reports (outside the lab) of creative behavior and daydreaming. None of the trait daydreaming factors correlated significantly with divergent thinking performance, and the study did not report whether daily-life daydreaming predicted divergent thinking. Most recently, Zeitlen et al. (2022) found that rates of mind-wandering recorded with experience-sampling probes in everyday life were not associated with divergent thinking performance in the lab (or with self-reported creative achievement, or momentarily thinking about a creative project in daily life).

An increasing number of studies have been investigating the possible link between divergent thinking and either alternative conceptions of mind-wandering (beyond TUT) measured in the lab, or daily-life experiences of mind-wandering measured outside the lab. Support for such a link, however, remains limited and inconsistent.

The Present Research: Goals and Questions

WMC, attention control, and mind-wandering are all implicated in contemporary thought on creative idea production. However, the relations between each of these executive-control constructs and creative cognition are not yet well established and, for mind-wandering, are hotly debated. Some research (Frith et al., 2021; Murray et al., 2021; Smeekens & Kane, 2016; Steindorf et al., 2020) suggests that mind-wandering inhibits the creative process (or is irrelevant to it), but other studies suggest its positive contribution (Baird et al., 2012; Irving et al., 2022; Tan et al., 2022; Teng & Lien, 2022;). As noted above, better progress might be made by measuring different facets or dimensions of mind-wandering beyond TUT, as well as measuring propensity for mind-wandering beyond the laboratory, in everyday life circumstances.

The present study, in addition to offering a conceptual replication of Frith et al. (2021) by examining how lab-based measures of executive control and mind-wandering relate to divergent thinking in a large undergraduate sample, speaks to Zeiten et al. (2022) by examining the association of divergent thinking with daily-life mind-wandering rates as measured with experience sampling methods. It also presents exploratory analyses offering a preliminary examination of other laboratory measures of mind-wandering experiences, particularly those involving fantastical daydreaming, and their potential correlations with divergent thinking. Finally, the present study includes an alternative measure of divergent thinking creativity that might offer greater sensitivity to the potential advantages of TUTs.

This work was guided by the following research questions: (1) How strongly is divergent thinking associated with WMC, attentional control, and TUT rate measured in the laboratory? (2) How does considering daily-life TUT propensities provide additional information for this model? (3) Does considering subjects’ rate of fantastical, unrealistic TUTs in a laboratory setting provide stronger evidence for a positive association between mind-wandering and creative cognition? (4) Are divergent thinking measures that emphasize participants’ most creative ideas, rather than their average idea quality, more sensitive to individual differences in executive control and mind-wandering?

Methods

The executive control and mind-wandering measures used here were taken from Kane et al. (2016) and Kane et al. (2017); the laboratory subjects reported on by Kane et al. (2016) also completed two divergent thinking tasks that were not analyzed for that article and are the focus of the present work. Those prior articles describe how we determined our sample sizes, as well as all data exclusions and all included measures (following Simmons et al., 2012). The study received ethics approval from the Institutional Review Board at UNC Greensboro (UNCG; protocol 10–0412).

Subjects

As reported in Kane et al. (2016), 541 UNCG undergraduates completed the first of three laboratory sessions, 492 completed the second, and 472 completed the third; the divergent thinking measures were collected in the third session. The originally reported demographic information for these subjects is below:

Sixty-six percent of our 541 analyzed subjects self-identified as female and 34% as male (5 missing cases), with a mean age of 19 years (sd = 2; 2 missing cases). Also by self-report, the racial composition of the sample was 49% White (European/Middle Eastern descent); 34% Black (African/Caribbean descent); 7% Multiracial; 4% Asian; <1% Native American/Alaskan Native; 0% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander; 4% Other (4 missing cases). Finally, self-reported ethnicity, asked separately, was 7% Latino/Hispanic (1 missing case).

(Kane et al., 2016, pp. 1026–1027)

As reported in Kane et al. (2017), 274 of these subjects completed an additional daily-life experience sampling protocol. Here is the originally reported demographic information for this subset of subjects:

We collected usable experience-sampling data from 274 subjects (188 female, 81 male, 5 with unreported gender), ages 18 to 35 years (M = 18.74, SD = 1.79; n = 273) after dropping 2 subjects’ data…The self-reported racial distribution of the sample (n = 271) was 44% African American, 42% White, 3% Asian, 0% Native American or Alaskan Native, 0% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, 6% multiracial, and 6% other; in response to a separate question, 8% of the sample (n = 272) reported being Latino or Hispanic.

(Kane et al., 2017, pp. 1273)

The present study analyzes the data from the 467 subjects who completed all three laboratory sessions (for our analyses of laboratory predictors of divergent thinking performance) and from the 266 subjects who completed the daily-life protocol and all three laboratory sessions (for our analyses of daily-life and laboratory predictors of divergent thinking performance).

Tasks and Measures

Kane et al. (2016) described the laboratory cognitive tasks used as predictors here, as well as their scoring and dependent measures, whereas Kane et al. (2017) described the relevant daily-life mind-wandering measure. We therefore provide only brief descriptions of the relevant measures here. We provide more detailed information, however, about the divergent thinking tasks that are central for the current study. Across the three experimental sessions reported in Kane et al. (2016), subjects completed at least one measure of each construct and at least one probed task (with the exception of the two divergent thinking measures, which were both completed in the third session).

WMC

Subjects completed six WMC measures. Four complex span tasks (operation, reading, symmetry, and rotation spans) presented sequences of to-be-remembered items (e.g., letters; spatial locations in a matrix) of varying set sizes for immediate serial recall; prior to the presentation of each memory item, an unrelated processing task required a yes/no response prior to a deadline (e.g., a mathematical equation that was correct or incorrect; an abstract pattern that was vertically symmetrical or not). Two memory-updating tasks (an updating counters task and a running span task) required subjects to maintain an evolving set of stimuli (numbers or letters) of varying set sizes and to abandon no-longer relevant stimuli from the memory set. Across all WMC tasks, higher scores reflected more accurate recall (i.e., higher proportion-correct scores).

Attention Control (Failures)

Five tasks required subjects to override a prepotent response in favor of a goal-appropriate one; Kane et al. (2016) characterized these as “attention restraint” tasks. Subjects completed two antisaccade tasks (that required identifying pattern-masked stimuli [either arrows or letters] presented to the opposite side of an attention-attracting cue; the dependent variable for each was error rate), a go/no-go SART task (that required withholding a key-press response on a minority of semantic-classification trials [animal stimuli appeared on 89% of trials while vegetables appeared on 11%]; dependent variables were d’ and intrasubject standard deviation in RT [RTsd]), and two Stroop-like tasks, a spatial Stroop and a number Stroop (that both required ignoring a salient stimulus dimension in favor of responding to another stimulus dimension; the dependent variable for spatial Stroop was the residual of the incongruent trial error rate regressed on the congruent trial error rate, and for number Stroop was the M RT on incongruent trials). For most of the attention control measures (other than SART dʹ), higher scores reflected worse performance (i.e., greater error rate, longer or more variable RTs).

TUT Rates

TUT rates were calculated from subjects’ responses to thought probes that appeared in five tasks. The letter flanker task presented 12 probes (following 8.3% of total trials), 4 after congruent trials, 2 after neutral trials, 2 after stimulus-response (S-R) conflict trials, 2 after stimulus-stimulus (S-S) conflict trials, and 2 after trials with a set of mixed flankers. The SART presented 45 probes following no-go target trials (6.6% of total trials). The number Stroop task presented 20 probes in the second block of the task, all following incongruent trials (13% of block 2 trials). The arrow flanker task presented 20 probes across two task blocks, 4 in the first block and 16 in the second (10.4% of total trials). Finally, the 2-back task presented 15 probes (following 6.3% of trials).

Each probe presented 8 response options and subjects selected the one that most closely reflected the content of their immediately preceding thoughts by pressing the corresponding number key: 1) “the task” (thoughts about the task stimuli or goals), 2) “task experience/performance” (evaluative thoughts about one’s task performance, 3) “everyday things” (thoughts about normal life concerns and activities), 4) “current state of being” (thoughts about one’s physical, cognitive, or emotional states), 5) “personal worries” (worried thoughts), 6) “daydreams” (fantastical, unrealistic thoughts), 7) “external environment” (thoughts about environmental stimuli), and 8) “other” (thoughts not fitting other categories). As in Kane et al. (2016), here we defined TUTs as response options 3–8. In exploratory analyses, we will define daydreaming-focused TUTs as corresponding to response option 6.

Daily-Life Mind-wandering

As reported in Kane et al. (2017), subjects completed a 7-day experience sampling protocol, in which they were randomly signaled throughout eight stratified time blocks during the day (once per 90 min time window between noon and midnight) by a study-supplied device to complete a questionnaire about their immediately preceding thoughts and their current psychological and physical context. The first item of each questionnaire asked participants whether they were mind-wandering (i.e., thinking about something other than their ongoing activity) at the time of the signal, for a yes or no response. For the current analyses, we took the rate of each subject’s mind-wandering (yes) responses across all the signals to which each subject responded (each subject’s denominator was individualized because not all subjects responded to all signals throughout the week).

Divergent Thinking

Subjects completed two alternative uses tasks to measure divergent thinking, one asking for creative uses for a knife and the other for a brick. The knife task was the second task in the third laboratory session, and the brick task was the ninth and final task in that session. The instructions for the two tasks were identical, aside from the target-cue item (brick or knife). Specifically, subjects were encouraged to think up unique and clever ways to use an everyday object; that is, they were explicitly instructed to “be creative” (e.g., Nusbaum et al., 2014):

Certainly there are many common and everyday ways to use a [knife/brick]. But for this task, we want you to list all of the unusual and uncommon uses that you can invent or think of. Try to think creatively, and try to come up with clever uses for a [knife/brick] that are not like any uses that you’ve ever seen or heard of before. Your goal is to try to develop such original and clever uses for a [knife/brick] that few other UNCG students will come up with the same ideas as you.

After typing each response, subjects hit the ENTER key to record it. Subjects had 3 min to generate responses for each task.

We followed guidelines for subjective scoring of creativity measures as detailed by Silvia et al. (2008). For each response, six raters (four of the present authors [RRB, MSW, RAB, and MJK], a graduate student who is not a co-author, and an undergraduate research assistant who is not a co-author) determined how creative/original the response was on a scale of 1 (not at all creative) to 5 (highly creative). Raters holistically scored the creativity of individual responses based on three facets: how uncommon (but appropriate1) they are, how different from everyday ideas they are, and how clever the response was. Raters received the individual responses from all subjects for a given task (e.g., all brick responses) in different alphabetized orders, starting with the first letter of the response (e.g., Rater 1 saw A–Z; Rater 2 saw Z–A etc.). This prevented later items from being biased and scored differently across raters. Raters were blinded to which responses came from which participants (and whether any of multiple responses came from any single participant) and blinded to all other task measures from each participant.

We instructed raters to read through the entire list of items before rating to check for nonsensical responses (which did not receive a score) and to bulk score uncreative items (e.g., “to build a house” for Brick, or “to cut an apple” for Knife); all responses judged to reflect the intended use of the object received a score of 1 (e.g., build a brick walkway; use a knife to slice bread), and all responses judged to reflect unintended but common uses of the object received a score of 2 (e.g., using a brick as a doorstop; scraping muddy shoe soles with a knife). We further instructed raters to use the whole rating scale. Following completion of scoring, raters were asked to sort the file by ratings to ensure the range was used and to calibrate accordingly if there was an imbalance of scores. Intraclass correlations, calculated using the irr package (Gamer & Lemon, 2019), among the raters suggested adequate reliability and consistency (ICCBrick = .896, 95% CI [.880, .910]; ICCKnife = .935, 95% CI [.925, .944]), consistent with previous work (Silvia et al., 2008).2

The primary dependent measure for the creativity measures was each subject’s average item rating for each rater, for each task. Thus, for each divergent thinking task, there were six rater-specific indicator scores contributing to each latent variable for Brick and Knife (five scores in the case of Brick, as there were only five Brick raters). As a secondary measure, which we thought might be more sensitive to variation in executive abilities, TUT propensity, or both, we instead used the number of 4 or 5 ratings each subject received from each rater, for each task. Many approaches to divergent thinking scoring have noted that the “better responses” (as selected by linguistic features, rater scores, or the participants) are often stronger predictors (Gonthier & Besançon, 2022; Reiter-Palmon et al., 2019; Runco, 1986; Silvia, 2008; Yu et al., 2023), usually because the common, early responses drag down the average creativity level. If good executive control affects subjects’ metacognitions about their creativity and their discernment about their output, it might be less associated with their maximal (most creative) scores than with their average scores, which are pulled down by noncreative output. Moreover, if TUTs—or some other dimensions of mind-wandering—help subjects produce some especially creative ideas, then this might be best reflected in their highest-rated output rather than their average output.

Results

We present our results in several sections. The first focuses on the relations between laboratory measures of executive control, including TUT rates, and divergent thinking scores (both average and most creative), which uses the full sample of subjects from Kane et al. (2016). The subsequent section uses the reduced sample of subjects from Kane et al. (2017), who additionally had experience-sampling measures of daily-life mind-wandering rate. The final section considers the association between divergent thinking and only TUTs reported as having fantastical, unrealistic content (“daydreams”). Data and analysis scripts are available via the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/at5gx/).

Before conducting analyses, we screened for and removed multivariate outliers in each dataset using the Routliers package (Delacre & Klein, 2019). We identified 10 multivariate outliers in the full lab dataset, resulting in a final sample of 457 (these were not identified or dropped from the original Kane et al. [2016] dataset). In the daily-life dataset, there were 2 multivariate outliers, leaving the final sample at 264. Unless otherwise stated, all latent variable models were run using the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012).

Descriptive Measures

Table 1 provides the descriptive measures for the divergent thinking variables of interest from the full sample’s laboratory assessments (descriptive measures and reliabilities for the executive measures from the full sample are provided in Kane et al., 2016, Table 4). Table 2 provides the bivariate correlations involving the average creativity ratings from the divergent thinking tasks. As with the full sample reported by Kane et al. (2016), cross-task correlations were moderate to strong within each ostensible predictor construct (WMC, Attention Control [failures], and TUT rate), indicating convergent validity, and were weaker between constructs, indicating discriminant validity. For the divergent thinking tasks, raters showed strong intercorrelations across Brick average scores (Mdn r = .54) and Knife average scores (Mdn r = .74), indicating good agreement in the average scoring within each task (consistent with the intraclass correlations reported above) and, moreover, raters showed moderate correlations across Brick and Knife scores for individual subjects (Mdn r = .28), indicating that the raters reliably captured individual differences in average divergent thinking performance.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Divergent Thinking Measures for Full lab sample

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | Skew | Kurtosis | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVERAGE DIVERGENT THINKING RATINGS | |||||||

| KNIFE R1 | 2.44 | 0.58 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.09 | 0.39 | 452 |

| KNIFE R2 | 1.79 | 0.43 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 0.62 | 1.32 | 452 |

| KNIFE R3 | 2.02 | 0.41 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 0.40 | 1.08 | 454 |

| KNIFE R4 | 2.02 | 0.41 | 1.00 | 3.20 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 454 |

| KNIFE R5 | 2.31 | 0.36 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 0.19 | 0.88 | 454 |

| KNIFE R6 | 1.83 | 0.48 | 1.00 | 3.40 | 0.56 | 0.18 | 452 |

| BRICK R1 | 2.75 | 0.37 | 1.00 | 4.25 | −0.52 | 1.69 | 450 |

| BRICK R2 | 1.75 | 0.37 | 1.00 | 3.50 | 0.59 | 1.05 | 450 |

| BRICK R3 | 2.10 | 0.36 | 1.00 | 3.50 | −0.05 | 0.40 | 450 |

| BRICK R4 | 1.94 | 0.39 | 1.00 | 3.50 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 450 |

| BRICK R5 | 2.03 | 0.31 | 1.00 | 3.25 | 0.23 | 0.85 | 450 |

| NUMBER OF 4/5 DIVERGENT THINKING RATINGS | |||||||

| KNIFE R1 | 0.78 | 1.06 | 0.00 | 7.00 | 1.86 | 4.63 | 443 |

| KNIFE R2 | 0.12 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 3.04 | 9.14 | 443 |

| KNIFE R3 | 0.23 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 2.02 | 3.30 | 443 |

| KNIFE R4 | 0.19 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.99 | 11.10 | 443 |

| KNIFE R5 | 0.34 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 1.98 | 5.12 | 443 |

| KNIFE R6 | 0.36 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.05 | 4.41 | 443 |

| BRICK R1 | 1.47 | 1.55 | 0.00 | 11.00 | 1.70 | 4.87 | 439 |

| BRICK R2 | 0.28 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 3.01 | 13.39 | 439 |

| BRICK R3 | 0.38 | 0.71 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 2.52 | 8.98 | 439 |

| BRICK R4 | 0.47 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 2.33 | 6.78 | 439 |

| BRICK R5 | 0.38 | 0.64 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 1.60 | 1.97 | 439 |

Notes. KNIFE = creative uses for a knife task; BRICK = creative uses for a brick task; R1–R6 = divergent thinking raters 1–6.

Table 4.

Zero-order correlations for the subsample who completed the daily-life experience sampling study.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 OPERSPAN | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 READSPAN | 0.56 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 SYMSPAN | 0.39 | 0.31 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 ROTSPAN | 0.48 | 0.31 | 0.62 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 RUNNSPAN | 0.43 | 0.32 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 COUNTERS | 0.29 | 0.17 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.42 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 ANTI-ARROW | −0.22 | −0.08 | −0.26 | −0.39 | −0.23 | −0.30 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 ANTI-LETTER | −0.14 | −0.07 | −0.27 | −0.24 | −0.21 | −0.32 | 0.56 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 SART d’ | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.20 | −0.25 | −0.36 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 SART RTSD | −0.14 | −0.15 | −0.30 | −0.21 | −0.21 | −0.21 | 0.26 | 0.38 | −0.61 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 11 S-STROOP | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.12 | −0.22 | −0.04 | −0.11 | 0.23 | 0.17 | −0.23 | 0.27 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 12 N-STROOP | −0.11 | 0.03 | −0.15 | −0.16 | −0.06 | −0.15 | 0.25 | 0.23 | −0.20 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 13 LETTER FLANKER TUTS | 0.13 | 0.08 | −0.11 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.15 | −0.22 | 0.32 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 14 SART TUTS | 0.04 | −0.12 | −0.11 | −0.07 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.12 | −0.19 | 0.31 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.45 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 15 N-STROOP TUTS | −0.09 | −0.13 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.06 | −0.05 | 0.14 | 0.14 | −0.26 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.34 | 0.46 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 16 ARROW FLANKER TUTS | −0.05 | −0.09 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.16 | −0.21 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.69 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 17 2-BACK TUTS | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.10 | −0.14 | −0.13 | 0.26 | 0.19 | −0.28 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.13 | 0.31 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.38 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 18 DAILY LIFE TUTs | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 19 KNIFE R1 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.04 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.06 | −0.07 | 0.10 | −0.04 | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.08 | 0.00 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 20 KNIFE R2 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.03 | −0.06 | 0.10 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.83 | 1 | |||||||||

| 21 KNIFE R3 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.08 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.10 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 1 | ||||||||

| 22 KNIFE R4 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.09 | 0.07 | 0.05 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.03 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 0.00 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.87 | 1 | |||||||

| 23 KNIFE R5 | −0.06 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.05 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.08 | 0.11 | −0.05 | 0.10 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.09 | 0.06 | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 1 | ||||||

| 24 KNIFE R6 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.09 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.07 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.64 | 1 | |||||

| 25 BRICK R1 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.06 | −0.13 | 0.08 | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 1 | ||||

| 26 BRICK R2 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.10 | −0.10 | −0.13 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.02 | −0.08 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.49 | 1 | |||

| 27 BRICK R3 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.09 | −0.13 | −0.17 | 0.06 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.62 | 0.59 | 1 | ||

| 28 BRICK R4 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.13 | −0.18 | 0.11 | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.60 | 0.69 | 0.87 | 1 | |

| 29 BRICK R5 | 0.13 | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.14 | −0.13 | −0.15 | 0.20 | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.05 | −0.06 | 0.01 | −0.13 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 1 |

Notes. OPERSPAN = operation span; READSPAN = reading span; SYMMSPAN = symmetry span; ROTASPAN = rotation span; RUNNSPAN = running span; COUNTERS = updating counters; ANTI-ARROW = antisaccade with arrow stimuli; ANTI-LETTER = antisaccade with letter stimuli; SART = sustained attention to response task; RTSD = intrasubject standard deviation in RT from SART; S-Stroop = spatial Stroop; N-Stroop = number Stroop; TUTs = rate of task-unrelated thoughts from task; KNIFE = average creativity rating for uses of a knife; BRICK = average creativity rating for uses of a brick; R1–R6 = divergent thinking raters 1–6.

Table 2.

Zero-order correlations of full lab sample

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 OPERSPAN | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 READSPAN | 0.59 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 SYMSPAN | 0.42 | 0.39 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 ROTSPAN | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.54 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 RUNNSPAN | 0.46 | 0.38 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 COUNTERS | 0.36 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.39 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 ANTI-ARROW | −0.25 | −0.19 | −0.30 | −0.37 | −0.27 | −0.33 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 ANTI-LETTER | −0.20 | −0.16 | −0.32 | −0.22 | −0.25 | −0.33 | 0.59 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 SART d’ | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.20 | −0.28 | −0.38 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 10 SART RTSD | −0.17 | −0.19 | −0.23 | −0.14 | −0.23 | −0.21 | 0.28 | 0.37 | −0.63 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 11 S-STROOP | −0.04 | −0.06 | −0.10 | −0.20 | −0.11 | −0.09 | 0.21 | 0.19 | −0.20 | 0.19 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 12 N-STROOP | −0.16 | −0.02 | −0.18 | −0.17 | −0.11 | −0.20 | 0.28 | 0.23 | −0.13 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 13 LETTER FLANKER TUTS | 0.09 | 0.00 | −0.10 | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.13 | −0.20 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 14 SART TUTS | −0.03 | −0.15 | −0.10 | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.13 | −0.23 | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.52 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 15 N-STROOP TUTS | −0.05 | −0.12 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.12 | −0.03 | 0.11 | 0.13 | −0.21 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 16 ARROW FLANKER TUTS | 0.00 | −0.08 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.10 | −0.04 | 0.06 | 0.15 | −0.19 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.67 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 17 2-BACK TUTS | −0.07 | −0.10 | −0.07 | −0.16 | −0.21 | −0.14 | 0.21 | 0.19 | −0.28 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.41 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 18 KNIFE R1 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.08 | 0.06 | −0.12 | −0.10 | 0.02 | −0.03 | −0.09 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 19 KNIFE R2 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.04 | −0.09 | 0.03 | −0.01 | −0.09 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.81 | 1 | |||||||||

| 20 KNIFE R3 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.05 | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.08 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.78 | 0.74 | 1 | ||||||||

| 21 KNIFE R4 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.07 | −0.06 | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.83 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 1 | |||||||

| 22 KNIFE R5 | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.05 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.63 | 1 | ||||||

| 23 KNIFE R6 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.74 | 0.57 | 1 | |||||

| 24 BRICK R1 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.12 | −0.08 | 0.11 | −0.03 | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 1 | ||||

| 25 BRICK R2 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.08 | −0.15 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.07 | −0.03 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.53 | 1 | |||

| 26 BRICK R3 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.05 | −0.17 | −0.09 | 0.04 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.36 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 1 | ||

| 27 BRICK R4 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.19 | −0.08 | 0.08 | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.88 | 1 | |

| 28 BRICK R5 | 0.14 | 0.11 | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.06 | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 1 |

Notes. OPERSPAN = operation span; READSPAN = reading span; SYMMSPAN = symmetry span; ROTASPAN = rotation span; RUNNSPAN = running span; COUNTERS = updating counters; ANTI-ARROW = antisaccade with arrow stimuli; ANTI-LETTER = antisaccade with letter stimuli; SART = sustained attention to response task; RTSD = intrasubject standard deviation in RT from SART; S-Stroop = spatial Stroop; N-Stroop = number Stroop; TUTs = rate of task-unrelated thoughts from task; KNIFE = average creativity rating for uses of a knife; BRICK = average creativity rating for uses of a brick; R1–R6 = divergent thinking raters 1–6.

Measurement Model of Divergent Thinking

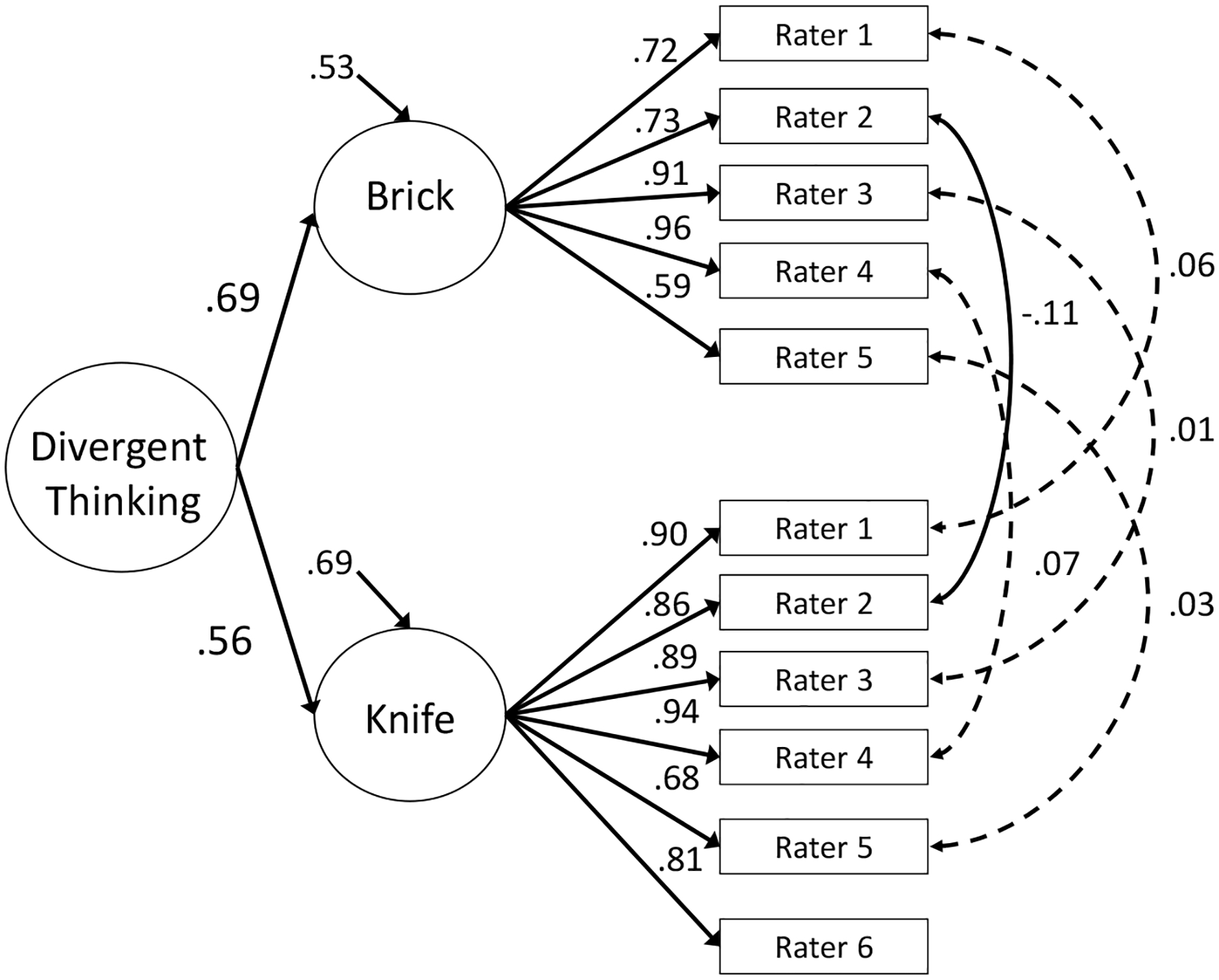

We first tested whether a hierarchical structure fit the divergent thinking data (e.g., Frith et al., 2021; Silvia et al., 2008). To do this, we modeled first-order latent variables for both the brick and knife tasks based on individual raters’ average scores. Given that most of the raters scored both brick and knife responses, and that raters may have similar scoring tendencies (or biases) for each task, we included residual correlations amongst raters (i.e., a residual correlation for Rater 1 Brick and Rater 1 Knife; note that one rater scored only the Knife task). Since there were only two first-order factors, we also constrained these Brick and Knife factors to load equally onto the second-order Divergent Thinking variable for model identification. This hierarchical model adequately fit the data, χ2(38) = 204.83, CFI =.959, TLI = .941, RMSEA [90% CI] = .098 [.085, .111], SRMR = .034. As seen in Figure 1, all raters loaded significantly onto their respective task factors. As well, both first-order factors loaded significantly onto the higher-order factor.

Figure 1.

Measurement model for the divergent thinking construct (average scores). Brick = unusual uses for a brick task; Knife = unusual uses for a knife task. Dotted arrows represent non-significant paths.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Cognitive Correlates of Divergent Thinking

Our next analysis focused on the relations between our executive control constructs and divergent thinking, all measured in the laboratory. Specifically, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis including latent factors for each cognitive ability construct and the divergent thinking hierarchical construct presented above. This model provided an adequate fit to the data, χ2(333) = 681.68, CFI =.943, TLI = .936, RMSEA = .048 [.043, .053], SRMR = .046. Figure 2 displays the model (factor loadings for the manifest variables are presented in Table 5). Both WMC and attention control (failures) correlated modestly with higher divergent thinking scores, with higher ability scores associated with more creative divergent thinking responses. TUT rates during the laboratory tasks, however, did not correlate significantly with divergent thinking creativity ratings (path estimate = −.002).

Figure 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis of the cognitive correlates of divergent thinking average scores. WMC = working memory capacity; Attention Control = attention control (failures); TUT rate = task-unrelated thought rate; Brick = unusual uses for a brick task; Knife = unusual uses for a knife task. Dotted arrows represent non-significant paths. Factor loadings for manifest variables are presented in Table 5. The path estimate between TUT rate and Divergent thinking (−.00), is negative when expressed to three decimal places.

Table 5.

Standardized Factor Loadings (and Standard Errors) for Latent Variable Models

| Construct and Measure | Model Name | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Lab Divergent Thinking CFA | Full Lab Divergent Thinking Bifactor | ESM Divergent Thinking CFA | |

| WMC/WMC resid | |||

| OPERSPAN | .66 (.04) | .74 (.07) | .60 (.06) |

| READSPAN | .54 (.05) | .61 (.07) | .42 (.07) |

| SYMSPAN | .61 (.04) | .39 (.06) | .55 (.07) |

| ROTSPAN | .53 (.05) | .35 (.06) | .58 (.07) |

| RUNSPAN | .61 (.04) | .44 (.06) | .59 (.07) |

| UPDATING | .59 (.04) | .30 (.06) | .60 (.06) |

| Attention Control | |||

| ANTI-LETTER | .75 (.03) | .70 (.05) | |

| ANTI-ARROW | .73 (.04) | .67 (.05) | |

| SART d’ | −.50 (.05) | −.50 (.06) | |

| SART RTSD | .49 (.05) | .55 (.06) | |

| S-STROOP | .28 (.06) | .34 (.07) | |

| N-STROOP | .35 (.05) | .37 (.07) | |

| TUT/TUT resid | |||

| SART TUT | .63 (.04) | .60 (.05) | .65 (.06) |

| N-STROOP TUTS | .69 (.04) | .69 (.05) | .66 (.05) |

| ARROW FLANKER TUTS | .67 (.04) | .68 (.05) | .60 (.06) |

| LETTER FLANKER TUTS | .52 (.05) | .48 (.05) | .51 (.07) |

| N-BACK TUTS | .64 (.04) | .53 (.05) | .66 (.05) |

| Common Executive | |||

| OPERSPAN | −.32 (.05) | ||

| READSPAN | −.26 (.05) | ||

| SYMSPAN | −.44 (.05) | ||

| ROTSPAN | −.41 (.05) | ||

| RUNSPAN | −.38 (.05) | ||

| UPDATING | −.45 (.05) | ||

| ANTI-LETTER | .74 (.03) | ||

| ANTI-ARROW | .74 (.04) | ||

| SART d’ | −.49 (.05) | ||

| SART RTSD | .49 (.05) | ||

| S-STROOP | .30 (.05) | ||

| N-STROOP | .35 (.05) | ||

| SART TUT | .19 (.05) | ||

| N-STROOP TUTS | .21 (.05) | ||

| ARROW FLANKER TUTS | .18 (.05) | ||

| LETTER FLANKER TUTS | .18 (.05) | ||

| N-BACK TUTS | .34 (.05) | ||

| Brick | |||

| RATER 1 | .72 (.03) | .72 (.03) | .66 (.04) |

| RATER 2 | .73 (.02) | .73 (.02) | .71 (.03) |

| RATER 3 | .91 (.01) | .91 (.01) | .90 (.02) |

| RATER 4 | .96 (.01) | .96 (.01) | .96 (.02) |

| RATER 5 | .59 (.03) | .59 (.03) | .47 (.05) |

| Knife | |||

| RATER 1 | .90 (.01) | .90 (.01) | .92 (.01) |

| RATER 2 | .86 (.01) | .86 (.01) | .89 (.02) |

| RATER 3 | .89 (.01) | .89 (.01) | .91 (.01) |

| RATER 4 | .94 (.01) | .94 (.02) | .93 (.01) |

| RATER 5 | .68 (.03) | .68 (.01) | .72 (.03) |

| RATER 6 | .81 (.02) | .81 (.03) | .85 (.02) |

Note. ESM = experience sampling measurement; OPERSPAN = operation span; READSPAN = reading span; SYMMSPAN = symmetry span; ROTASPAN = rotation span; RUNNSPAN = running span; COUNTERS = updating counters; ANTI-ARROW = antisaccade with arrow stimuli; ANTI-LETTER = antisaccade with letter stimuli; SART = sustained attention to response task; RTSD = intrasubject standard deviation in RT from SART; S-Stroop = spatial Stroop; N-Stroop = number Stroop; TUTs = rate of task-unrelated thoughts from task. R1–R6 = divergent thinking raters 1–6.

Bifactor Model of Cognitive Correlates of Divergent Thinking

Following conceptually from the model tested by Frith et al. (2021), we next assessed whether the variance common to all our executive control measures, or the residual variance shared among the WMC tasks or among TUT rates, predicted divergent thinking scores. To do so, we created a bifactor model in which all cognitive indicators loaded onto a common executive control factor, indicating variance shared across the indicator measures. We also specified residual (orthogonal) WMC and TUT rate factors, indicating unique variance to WMC and TUT rates, after accounting for the general executive factor variance.

The bifactor model adequately fit the data, χ2(325) = 647.10, CFI =.948, TLI = .939, RMSEA = .047 [.041, .052], SRMR = .043. The resulting structural model is displayed in Figure 3 (factor loadings are presented in Table 5). Consistent with Frith et al. (2021), divergent thinking ability was significantly predicted by general executive failures (β = −.20, p = .006). Further, neither of the specific (residual) factors significantly predicted divergent thinking: residual WMC (β = .07, p = .369), residual TUT rate (β = .07, p = .352). Thus, the associations of WMC and attention control with divergent thinking scores are due to their shared executive-control-related variance.

Figure 3.

Bifactor model of executive control correlates of divergent thinking scores. Executive control = variance common to all working memory capacity (WMC), attention control, and task-unrelated thought (TUT) rate indicators; WMCresid = variance shared among WMC task scores after accounting for shared executive control variance; TUTresid = variance shared among TUT rates after accounting for shared executive control variance; Brick = unusual uses for a brick task; Knife = unusual uses for a knife task. Dotted arrows = nonsignificant paths. Factor loadings for manifest variables are presented in Table 5.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Including Daily-Life Mind-wandering Rate

Our next analysis included only the subsample of subjects who completed the daily-life experience-sampling study reported in Kane et al. (2017), in addition to the laboratory tasks reported by Kane et al. (2016). We used the laboratory-task data, including divergent thinking, from these 264 subjects and added the manifest variable for their daily-life TUT rate. Descriptive statistics for the divergent thinking measures are reported in Table 3 and correlations among the measures are reported in Table 4.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of Divergent Thinking measures and daily life mind wandering for subsample of subjects completing the daily-life experience sampling study.

| M | SD | Min | Max | Skew | Kurtosis | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAILY LIFE TUTS | 0.32 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.97 | 0.74 | 0.61 | 266 |

| AVERAGE DIVERGENT THINKING RATING | |||||||

| KNIFE R1 | 2.44 | 0.60 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.17 | 0.59 | 263 |

| KNIFE R2 | 1.80 | 0.44 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 0.73 | 1.90 | 263 |

| KNIFE R3 | 2.03 | 0.44 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 0.42 | 1.02 | 265 |

| KNIFE R4 | 2.02 | 0.43 | 1.00 | 3.20 | 0.14 | −0.10 | 263 |

| KNIFE R5 | 2.29 | 0.37 | 1.00 | 3.29 | −0.07 | −0.12 | 265 |

| KNIFE R6 | 1.83 | 0.52 | 1.00 | 3.40 | 0.47 | −0.24 | 265 |

| BRICK R1 | 2.76 | 0.37 | 1.00 | 3.75 | −0.79 | 2.22 | 261 |

| BRICK R2 | 1.74 | 0.35 | 1.00 | 3.14 | 0.40 | 0.58 | 261 |

| BRICK R3 | 2.11 | 0.35 | 1.00 | 3.00 | −0.31 | 0.38 | 261 |

| BRICK R4 | 1.95 | 0.37 | 1.00 | 2.87 | 0.04 | −0.12 | 261 |

| BRICK R5 | 2.07 | 0.38 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 2.01 | 8.59 | 261 |

| NUMBER OF 4/5 DIVERGENT THINKING RATING | |||||||

| KNIFE R1 | 0.88 | 1.27 | 0.00 | 9.00 | 2.39 | 8.58 | 265 |

| KNIFE R2 | 0.15 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 3.54 | 14.36 | 265 |

| KNIFE R3 | 0.28 | 0.59 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 2.33 | 5.39 | 265 |

| KNIFE R4 | 0.43 | 0.79 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 2.35 | 6.68 | 265 |

| KNIFE R5 | 0.25 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.97 | 9.54 | 265 |

| KNIFE R6 | 0.34 | 0.57 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 1.55 | 2.02 | 265 |

| BRICK R1 | 1.69 | 1.72 | 0.00 | 11.00 | 1.87 | 5.11 | 261 |

| BRICK R2 | 0.31 | 0.58 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.20 | 6.58 | 261 |

| BRICK R3 | 0.42 | 0.75 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 2.38 | 7.52 | 261 |

| BRICK R4 | 0.55 | 0.90 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 2.21 | 5.84 | 261 |

| BRICK R5 | 0.39 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 1.55 | 1.93 | 261 |

Notes. R1–R6 = divergent thinking raters 1–6.

Subjects reported TUTs at 32% of the daily-life thought probes, on average, with considerable variation around that mean (SD = 16%; Min = 2%; Max = 97%). Daily-life TUT rates, moreover, correlated much less strongly with the laboratory-task TUT rates (Mdn r = .05) than the laboratory-task TUT rates correlated with each other (Mdn r = .41). Finally, daily-life TUT rates showed almost no correlation with any of the rater-specific scores for either divergent thinking task (Mdn r = .00).

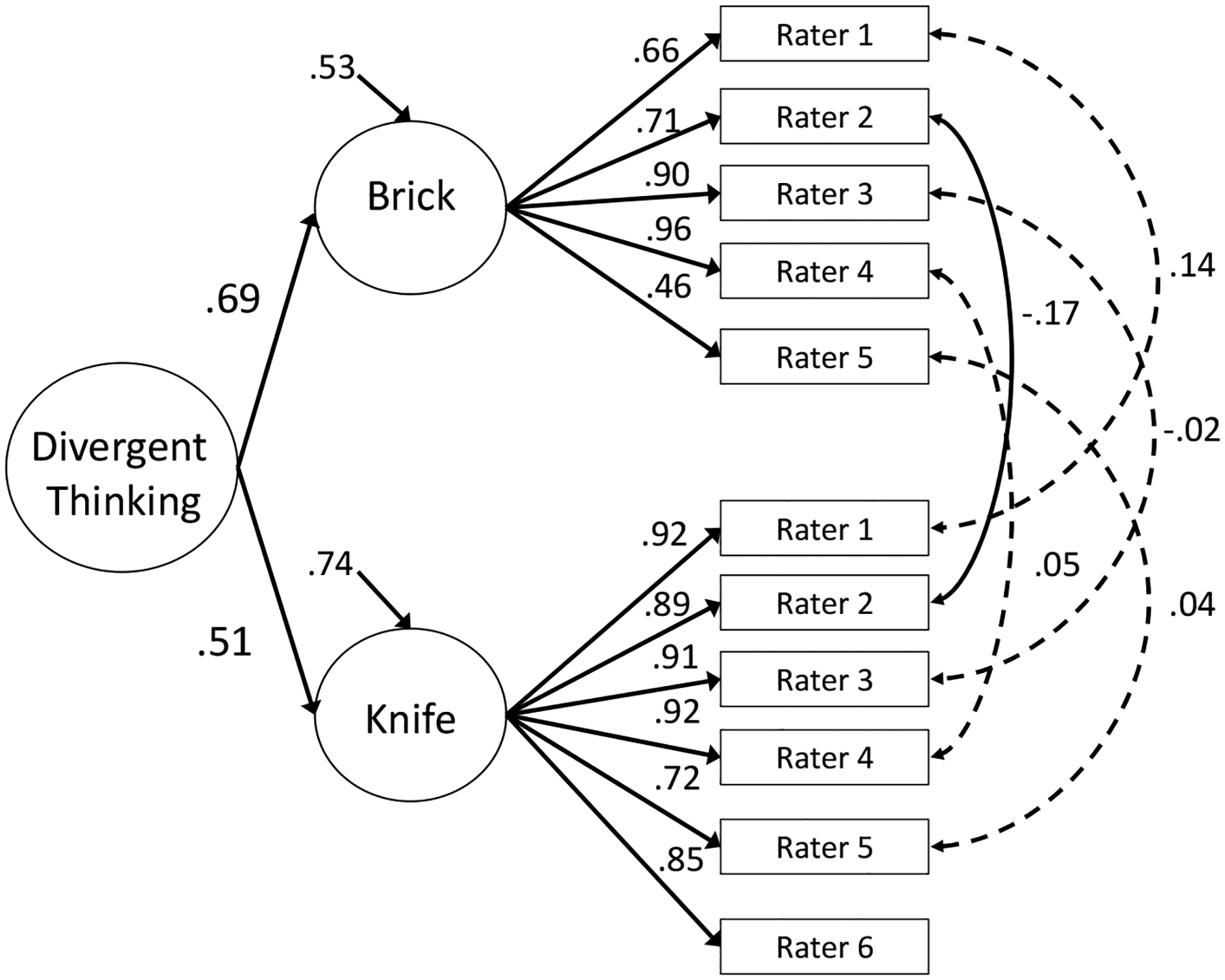

As shown in Appendix A (Figure A1), the hierarchical measurement model of divergent thinking also fit the data from this subsample of subjects who completed the daily life assessment. We therefore conducted a CFA including latent factors for WMC, attention control (failures), laboratory-task TUT rate, and a manifest variable for daily-life TUT rate, along with the hierarchical divergent thinking construct. This model provided an adequate fit to the data, χ2(357) = 528.18, CFI =.951, TLI = .944, RMSEA [90% CI] = .043 [.035, .050], SRMR = .053. The resulting model is displayed in Figure 4 (factor loadings of manifest variables are presented in Table 5).

Figure 4.

Confirmatory factor analysis of the cognitive correlates of divergent thinking, for the subject subsample who completed the daily-life experience sampling study.. WMC = working memory capacity; Attention Control = attention control (failures); TUT rate = task-unrelated thought rate from laboratory tasks; Daily-Life TUT rate = task-unrelated thought rate during daily-life experience sampling; Brick = unusual uses for a brick task; Knife = unusual uses for a knife task. Dotted arrows represent non-significant paths. Factor loadings for manifest variables are presented in Table 5.

In this reduced sample, WMC did not correlate significantly with divergent thinking creativity ratings (p = .070), although the association was in the same direction with a comparable effect size to the full-sample model. Attention control (failures) did again correlate significantly, but modestly, with divergent thinking scores. TUT rates measured during laboratory tasks and in daily-life were weakly and nonsignificantly correlated with each other, and both showed near-zero, nonsignificant correlations with divergent thinking.

Scoring Divergent Thinking for Highly Creative Responses

Modeling creativity as an average rating across generated ideas will penalize subjects who produce some uncreative ideas, even if they also produce some highly creative ideas. Averaging all ratings, then, might conflate creative output with idea discernment (or metacognition about creativity). Perhaps the increased mind-wandering that comes with poorer attention control really does allow people better access to more creative ideas, but if that poorer attention control also causes those people to blurt out obvious responses before landing upon more novel ones, its benefit is functionally negated.

As an alternative scoring method to capture primarily peak creativity rather than discernment, then, we counted the total number of highly creative responses (ideas rated as a 4 or 5) for each rater for each subject; these scores reflect the frequency of a subject’s highly creative ideas independent of their worst ideas. We followed the same multivariate outlier procedure as before, with highly creative responses as the divergent thinking measure rather than average ratings. Our multivariate outlier screening identified 21 outliers who were removed before performing analyses using highly creative responses (this resulted in different Ns reported in Tables 1 and 3).

We used the same modeling approach in examining the relationship between (highly creative) Divergent Thinking and executive abilities in both the lab and daily-life samples. Descriptive statistics for these measures are presented in Tables 1 and 3 for the lab and the reduced daily-life samples, respectively. Zero-order correlations between the cognitive measures and these highly creative response scores are presented in Tables 6 and 7 for the lab and daily-life samples, respectively. Despite the high (positive) skewness and kurtosis of the highly creative scores, they correlated strongly across raters and moderately across brick and knife tasks.3

Table 6.

Zero-order correlations of full lab sample using the number of highly creative responses from divergent thinking tasks (number of creativity ratings of 4 or 5)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 OPERSPAN | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 READSPAN | 0.57 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 SYMSPAN | 0.39 | 0.32 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 ROTSPAN | 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.61 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 RUNNSPAN | 0.42 | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 COUNTERS | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.42 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 ANTI-ARROW | −0.21 | −0.09 | −0.25 | −0.37 | −0.24 | −0.29 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 ANTI-LETTER | −0.14 | −0.08 | −0.26 | −0.23 | −0.23 | −0.31 | 0.57 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 SART d’ | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.19 | −0.24 | −0.34 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 10 SART RTSD | −0.14 | −0.16 | −0.30 | −0.20 | −0.21 | −0.21 | 0.25 | 0.37 | −0.60 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 11 S-STROOP | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.08 | −0.20 | −0.03 | −0.06 | 0.21 | 0.17 | −0.16 | 0.20 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 12 N-STROOP | −0.11 | 0.02 | −0.14 | −0.16 | −0.05 | −0.14 | 0.24 | 0.22 | −0.20 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 13 LETTER FLANKER TUTS | 0.13 | 0.08 | −0.10 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.15 | −0.22 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 14 SART TUTS | 0.04 | −0.13 | −0.10 | −0.07 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.12 | −0.18 | 0.31 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.45 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 15 N-STROOP TUTS | −0.08 | −0.14 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.07 | −0.04 | 0.13 | 0.13 | −0.25 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.34 | 0.46 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 16 ARROW FLANKER TUTS | −0.05 | −0.09 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.16 | −0.21 | 0.20 | −0.01 | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.68 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 17 2-BACK TUTS | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.09 | −0.14 | −0.12 | 0.26 | 0.18 | −0.27 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.13 | 0.31 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.37 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 18 KNIFE R1 4/5 | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 19 KNIFE R2 4/5 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.10 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.08 | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 1 | |||||||||

| 20 KNIFE R3 4/5 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.18 | −0.06 | −0.03 | 0.10 | −0.07 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.06 | −0.03 | −0.08 | 0.43 | 1 | ||||||||

| 21 KNIFE R4 4/5 | −0.09 | 0.06 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.02 | −0.06 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.00 | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.50 | 0.42 | 1 | |||||||

| 22 KNIFE R5 4/5 | −0.11 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.09 | 0.10 | −0.06 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.08 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 1 | ||||||

| 23 KNIFE R6 4/5 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.10 | −0.08 | −0.07 | −0.05 | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.00 | −0.09 | 0.59 | 0.42 | 0.58 | 0.51 | 1 | |||||

| 24 BRICK R1 4/5 | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 1 | ||||

| 25 BRICK R2 4/5 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.04 | −0.09 | −0.08 | 0.18 | −0.13 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.31 | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 1 | |||

| 26 BRICK R3 4/5 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.06 | −0.05 | −0.10 | 0.05 | 0.00 | −0.09 | −0.06 | 0.07 | 0.04 | −0.04 | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.01 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.23 | 0.32 | 0.52 | 1 | ||

| 27 BRICK R4 4/5 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.12 | −0.15 | 0.10 | −0.09 | −0.09 | −0.07 | −0.04 | 0.00 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 1 | |

| 28 BRICK R5 4/5 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.07 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.10 | −0.14 | 0.08 | −0.09 | −0.08 | −0.12 | −0.06 | −0.02 | 0.10 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.91 | 1 |

Notes. OPERSPAN = operation span; READSPAN = reading span; SYMMSPAN = symmetry span; ROTASPAN = rotation span; RUNNSPAN = running span; COUNTERS = updating counters; ANTI-ARROW = antisaccade with arrow stimuli; ANTI-LETTER = antisaccade with letter stimuli; SART = sustained attention to response task; RTSD = intrasubject standard deviation in RT from SART; S-Stroop = spatial Stroop; N-Stroop = number Stroop; TUTs = rate of task-unrelated thoughts from task; KNIFE = number of creativity ratings of 4 or 5 for uses of a knife; BRICK = number of creativity ratings of 4 or 5 for uses of a brick; R1–R6 = divergent thinking raters 1–6.

Table 7.

Zero-order correlations for the subsample who completed the daily-life experience sampling study using the number of highly creative responses from divergent thinking tasks (number of creativity ratings of 4 or 5).

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 OPERSPAN | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 READSPAN | 0.56 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 SYMSPAN | 0.39 | 0.31 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 ROTSPAN | 0.48 | 0.31 | 0.62 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 RUNNSPAN | 0.43 | 0.32 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 COUNTERS | 0.29 | 0.17 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.42 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 ANTI-ARROW | −0.22 | −0.08 | −0.26 | −0.39 | −0.23 | −0.30 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 ANTI-LETTER | −0.14 | −0.07 | −0.27 | −0.24 | −0.21 | −0.32 | 0.56 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 SART d’ | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.20 | −0.25 | −0.36 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 SART RTSD | −0.14 | −0.15 | −0.30 | −0.21 | −0.21 | −0.21 | 0.26 | 0.38 | −0.61 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 11 S-STROOP | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.12 | −0.22 | −0.04 | −0.11 | 0.23 | 0.17 | −0.23 | 0.27 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 12 N-STROOP | −0.11 | 0.03 | −0.15 | −0.16 | −0.06 | −0.15 | 0.25 | 0.23 | −0.20 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 13 LETTER FLANKER TUTS | 0.13 | 0.08 | −0.11 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.15 | −0.22 | 0.32 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 14 SART TUTS | 0.04 | −0.12 | −0.11 | −0.07 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.12 | −0.19 | 0.31 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.45 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 15 N-STROOP TUTS | −0.09 | −0.13 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.06 | −0.05 | 0.14 | 0.14 | −0.26 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.34 | 0.46 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 16 ARROW FLANKER TUTS | −0.05 | −0.09 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.16 | −0.21 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.69 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 17 2-BACK TUTS | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.10 | −0.14 | −0.13 | 0.26 | 0.19 | −0.28 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.13 | 0.31 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.38 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 18 DAILY LIFE TUTs | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 19 KNIFE R1 4/5 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.04 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.06 | −0.07 | 0.10 | −0.04 | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.08 | 0.00 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 20 KNIFE R2 4/5 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.03 | −0.06 | 0.10 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.83 | 1 | |||||||||

| 21 KNIFE R3 4/5 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.08 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.10 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 1 | ||||||||

| 22 KNIFE R4 4/5 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.09 | 0.07 | 0.05 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.03 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 0.00 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.87 | 1 | |||||||

| 23 KNIFE R5 4/5 | −0.06 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.05 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.08 | 0.11 | −0.05 | 0.10 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.09 | 0.06 | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 1 | ||||||

| 24 KNIFE R6 4/5 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.09 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.07 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.64 | 1 | |||||

| 25 BRICK R1 4/5 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.06 | −0.13 | 0.08 | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 1 | ||||

| 26 BRICK R2 4/5 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.10 | −0.10 | −0.13 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.02 | −0.08 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.49 | 1 | |||

| 27 BRICK R3 4/5 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.09 | −0.13 | −0.17 | 0.06 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.62 | 0.59 | 1 | ||

| 28 BRICK R4 4/5 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.13 | −0.18 | 0.11 | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.60 | 0.69 | 0.87 | 1 | |

| 29 BRICK R5 4/5 | 0.13 | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.14 | −0.13 | −0.15 | 0.20 | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.05 | −0.06 | 0.01 | −0.13 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 1 |

Notes. OPERSPAN = operation span; READSPAN = reading span; SYMMSPAN = symmetry span; ROTASPAN = rotation span; RUNNSPAN = running span; COUNTERS = updating counters; ANTI-ARROW = antisaccade with arrow stimuli; ANTI-LETTER = antisaccade with letter stimuli; SART = sustained attention to response task; RTSD = intrasubject standard deviation in RT from SART; S-Stroop = spatial Stroop; N-Stroop = number Stroop; TUTs = rate of task-unrelated thoughts from task; KNIFE = number of creativity ratings of 4 or 5 for uses of a knife; BRICK = number of creativity ratings of 4 or 5 for uses of a brick; R1–R6 = divergent thinking raters 1–6.

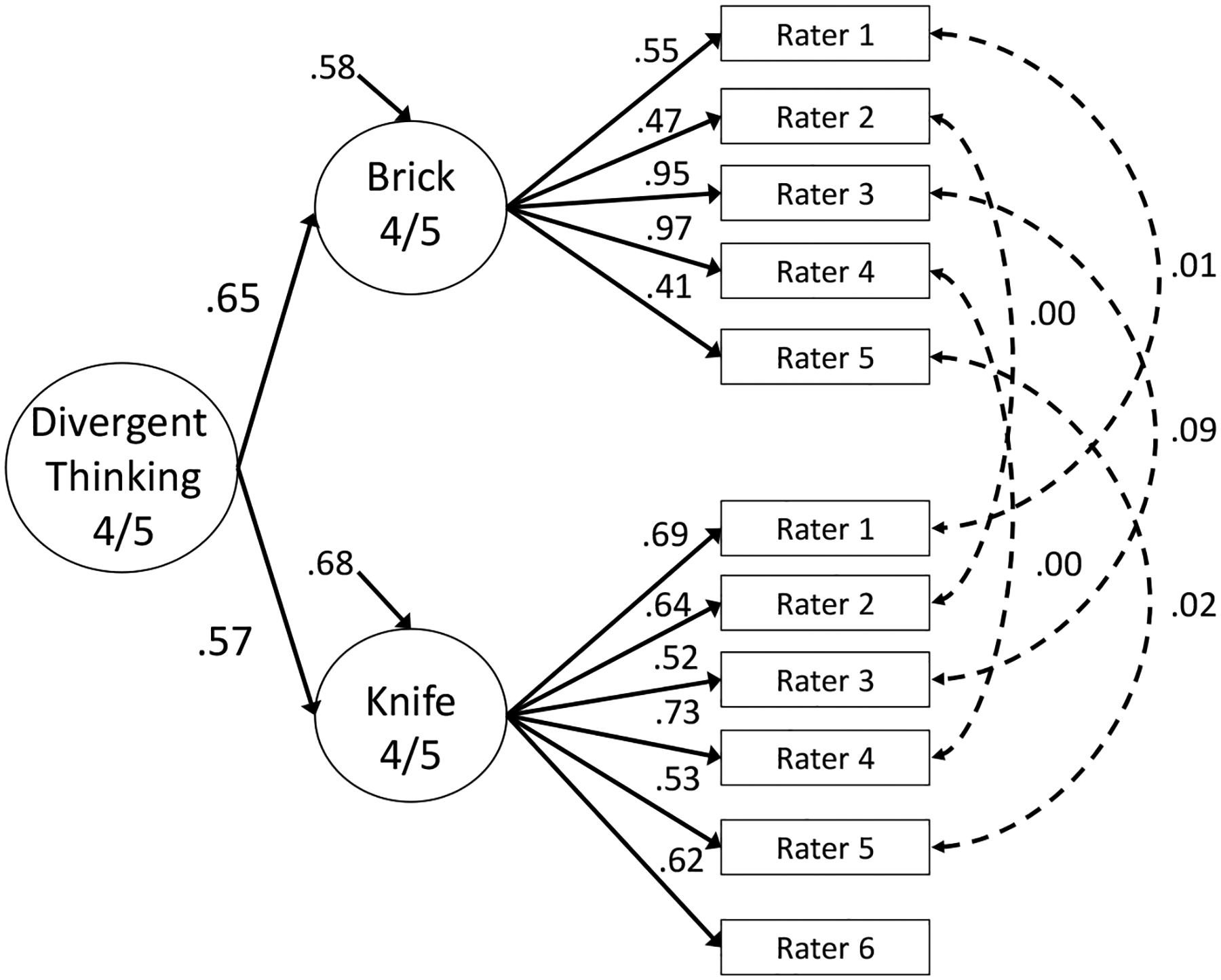

Measurement Model of Highly Creative Divergent Thinking Scores