Abstract

Background

Chronic low back pain (CLBP) is a highly prevalent and burdensome musculoskeletal disorder globally, significantly impacting individuals’ health and quality of life. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the somatic cell therapies in treating CLBP.

Methods

All relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in the Cochrane, Embase, PubMed, and Web of Science databases were systematically searched for the meta-analysis. The outcomes consisted of Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scores, Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) scores, and the incidence of serious adverse events (SAE). Dichotomous outcomes were described as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), while continuous data were presented as mean difference (MD) with 95% CIs. Statistical analysis was performed with RevMan 5.4 and stata 17 software.

Results

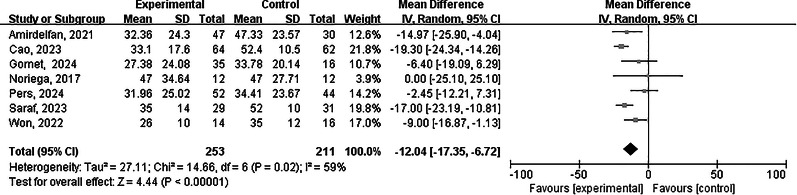

A total of seven RCTs involving 518 patients were included in the meta-analysis. The results showed that somatic cell therapies were effective in terms of VAS scores [MD = -12.04 (-17.35,-6.72)] and ODI scores [MD = -8.03 (-12.84,-3.22)], while not increasing risk of SAE [OR = 0.70 (0.19, 2.64)].

Conclusions

Our findings suggested that somatic cell therapy demonstrated significant therapeutic efficacy in the management of CLBP. Future large-scale, multicenter RCTs with extended follow-up durations are warranted to confirm the optimal somatic cell type and dosage regimen for maximal therapeutic benefit.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13287-025-04628-4.

Keywords: Chronic low back pain, Somatic cell, Meta-analysis

Introduction

CLBP represents a prevalent and multifaceted musculoskeletal condition [1], clinically characterized as persistent lumbosacral region discomfort exceeding three months’ duration [2]. Epidemiological studies reveal substantial disease burden, with annual incidence rates of back pain ranging between 15% and 45% and point prevalence rates averaging 30% across populations [3]. Notably, the global lifetime prevalence of CLBP approximates 9%, signifying its status as a major public health challenge [4]. Socioeconomic analyses estimate the total annual economic burden attributable to CLBP in the United States at 84.1 billion to 624.8 billion, encompassing direct healthcare expenditures, indirect productivity losses, and intangible social costs [5]. Given this significant clinical and financial impact, the medical community necessitates urgent development of novel therapeutic interventions that optimize both efficacy and safety profiles.

Current guidelines recommend exercise and multidisciplinary rehabilitation as first-line therapy in patients with CLBP [6]. For some patients, these conservative treatments exhibit suboptimal efficacy, failing to relieve pain and improve dysfunction [7]. Meanwhile, some commonly used medications for chronic low back pain may cause certain side effects. For example, taking NSAIDs may cause indigestion, heartburn, nausea, renal side effects, and increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases [7], while taking duloxetine may cause nausea, dry mouth, constipation, insomnia, dizziness, fatigue, irritability, and excessive sweating [8]. Emerging as a transformative regenerative medicine paradigm (Fig. 1), cellular therapy demonstrates translational potential for addressing CLBP pathophysiology through targeted tissue repair mechanisms [9].

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of cell therapy for chronic back pain treatment (TGF-β: Transforming Growth Factor - Beta, IGF-1: Insulin - like Growth Factor-1, PDGF: Platelet - Derived Growth Factor, bFGF: Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor, IDO: Indoleamine 2,3 - dioxygenase, VEGF: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor, IL-10: Interleukin-10)

Current RCTs on cell therapy for CLBP are limited by small sample sizes, raising concerns about false-positive efficacy [10]. To our best knowledge, no meta-analysis has incorporated sufficient high-quality RCTs to robustly demonstrate the effectiveness and safety of cell therapy for CLBP, and its long-term efficacy remains to be explored. Our study included multiple high-quality RCTs and analyzed multiple indicators for evaluating the efficacy and safety of somatic cell therapy for CLBP.

Materials and methods

Protocol and registration

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in accordance with the requirements of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). The protocol for this systematic review was registered prospectively with Prospero (ID-number: CRD42024625727).

Information sources and search strategy

In December 2024, a comprehensive search was carried out across several prominent databases, namely PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science. The search terms used were ((“stem cell” OR “somatic cell”) AND (“chronic low back pain”)). The latest retrieval time was December 11, 2024. Additionally, references of the retrieved articles were reviewed to include any potentially relevant studies that were not initially identified in the database search. The publication language was not restricted.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: [1] Adult patients (≥ 18 years old) with nonspecific low back pain or low back pain caused by lumbar disc degeneration, lumbar facet joint lesions or lumbar muscle strain and other conditions, whose pain had lasted at least three months, were included. However, those with low back pain caused by tumors, infections, fractures, spinal deformities, metabolic diseases, urinary system diseases, gynecological diseases, and vascular diseases were excluded; [2] The intervention measures involved local injection of cellular components such as Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), Disc Progenitor Cells (DPCs), Mesenchymal Precursor Cells (MPCs), Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP), Fibroblasts, etc. at the painful area or at the corresponding nerve root and intervertebral foramen; [3] The control group was only injected with physiological saline, hyaluronic acid (HA), lidocaine and so on, or was only observed and followed up; [4] The research design was RCTs with random allocation to the intervention and control groups.

Study selection and data extraction

Two independent reviewers (Li Zihao and Sun Yuming) conducted the literature search, data extraction, and quality assessment process in accordance with the inclusion criteria. Any discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion. Study selection was initially based on titles and abstracts, and full texts were retrieved and reviewed when necessary. The following data were extracted from the included studies: basic information of the study (author, publication year, research location, etc.), baseline characteristics of patients (age, gender etc.), details of intervention measures (cell type, number of cells, injection method etc.), control measures, follow-up time, and data on various outcome indicators (such as VAS scores, ODI scores, occurrence of adverse events). Automated data extraction tools were not used. In case of missing or unclear data, attempts were made to contact the corresponding author of the study for supplementary information. If multiple attempts were unsuccessful, reasonable assumptions were made based on existing data and the overall situation of the study during data synthesis analysis, with detailed explanations provided in the results.

Quality assessment

The Cochrane bias risk assessment tool was used to evaluate the bias risk of the included RCTs. Two independent reviewers (researchers Li Zihao and Sun Yuming) separately assessed the bias risk of each study. The Cochrane tool evaluates aspects such as random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and individuals, blinding of outcome evaluation, completeness of outcome data, selective reporting, and other potential sources of bias. After completion of the assessment, the two reviewers compared their results and discussed any differences to reach a consensus. No automated evaluation tools were used throughout the process.

Data synthesis and analysis

Meta-analyses were conducted using Review Manager 5.4 and STATA 17. For continuous outcome measures like VAS scores, ODI scores and so on, mean difference (MD) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were used as effect measures to measure differences between the intervention group and the control group, while for binary outcome measures such as the incidence of SAE, odds ratios (OR) and its 95% CI were used for effect evaluation [11]. Firstly, the intervention features in the study (including stem cell type, administration route, somatic cell type etc.) were compiled into a table and compared with the pre-set comprehensive grouping plan (stem cell therapy group, somatic cell therapy group, and their subgroups) to determine the comprehensive group each study belonged to. For outcome measures meeting the criteria for meta-analysis, appropriate models were selected based on heterogeneity test results. The random effects model was used to combine the effect sizes of VAS, ODI and SAE. For outcome measures that couldn’t be subjected to meta-analysis or cases with a small number of studies, a narrative synthesis method was used to systematically describe, compare, and summarize the results of each study and analyze their trends and consistency.

Results

Literature search

The PRISMA flowchart of the studies in this review was presented (Fig. 2). A total of 2629 records were retrieved from four databases, including 440 from PubMed, 124 from Cochrane, 834 from Embase, and 1231 from Web of Science. Before screening, 945 duplicate records were removed, then 1523 records were excluded based on titles and abstracts, and 161 records were evaluated for eligibility. 156 reports were ultimately excluded due to reasons such as non-randomized controlled trials, unexpected outcomes, incomplete data, involvement of acute or subacute back pain, and grey literature. Five new studies were included, along with two manually retrieved from other review references, for a total of seven studies included in this review.

Fig. 2.

PRISMA Flow Diagram of Literature Screening Process

Patient characteristics

Among the seven [12–18] included studies, one study included patients from France, Spain, Italy, and Germany [12]. There are two studies from the United States [13, 17], one from Spain [18], one from China [15], one from South Korea [16], and one from India [14]. In these studies, MSCs were infused in two studies [12, 18], DPCs were infused in one study [13], Mesenchymal Precursor Cells (MPCs) were infused in one study [17], and PRP was infused in three studies [14–16]. All studies were RCTs. All included RCTs were published between 2017 and 2024. In each study, the demographic characteristics of the two groups were similar. A total of 518 patients were included, with study sample sizes ranging from 24 to 126. The follow-up period ranges from eight weeks to 36 months. Characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Author, year | Country | Participants (exp/con) | Age (mean) | Male (exp/con) | Cell type | Amount of cells | Injection method | Control | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amirdelfan, 2021 | America, Australia | 60/40 | 33.6 | 33/20 | MPCs |

6*106/injection; 18*106/injection |

Intradiscal injection | 1% HA vehicle; saline placebo | 36 |

| Gornet, 2024 | America | 40/20 | 37.9 | 24/12 | DPCs |

3*106/mL; 9*106/mL |

Intradiscal injection | Sodium hyaluronate vehicle; normal saline placebo | 24 |

| Noriega, 2017 | Spain | 12/12 | 38.0 | NR | MSCs | 2.5 × 10⁷/segment | Intradiscal injection | Sham paravertebral muscle anesthesia infiltration | 12 |

| Pers, 2024 | France, Spain, Italy, Germany | 58/56 | 40.9 | NR | MSCs | 2 × 10⁷/injection | Intradiscal injection | Sham injection (2 mL sterile saline subcutaneously) | 24 |

| Cao, 2023 | China | 64/62 | 49.6 | 34/38 | PRP | 2 mL/injection | Intradiscal injection | RFAT + interventional circulatory perfusion only | 2 |

| Won, 2022 | South Korea | 14/16 | 50.7 | 6/6 | PRP | 5 ~ 6mL/injection | Injected at tenderness points | Lidocaine injection | 6 |

| Saraf, 2023 | India | 29/31 | 44.0 | 15/16 | PRP | 3 mL/injection | Transforaminal injection | Methylprednisolone acetate injection | 6 |

exp: experimental group; con: control group; NR: Not reported; MPCs: Mesenchymal Precursor Cells; DPCs: Disc Progenitor Cells; MSCs: Mesenchymal Stem Cells; PRP: Platelet - Rich Plasma;

HA: Hyaluronic Acid; RFAT: Radiofrequency Ablation and Thermocoagulation

Risk of bias

The assessment results of bias risk and methodological suitability of the included studies are presented in Fig. 3a, b. In the risk assessment of random sequence generation, incomplete outcome data, and other bias, all studies were rated as low-risk. In the allocation concealment risk assessment, one [15] study was rated as uncleared and six [12–14, 16–18] were rated as low-risk. In the assessment of blinding of participants and personnel, three [14, 15, 17] articles were rated as high-risk and four [12, 13, 16, 18] articles were rated as low-risk. In the blinding of outcome risk assessment, one [15] article was rated as unclear and six [12–14, 16–18] articles were rated as low-risk. In the selective reporting risk assessment, three [14–16] articles were rated as unclear and four [12, 13, 17, 18] articles were rated as low-risk.

Fig. 3.

a: Risk of bias graph. b: Summary of study risk bias analysis

VAS score

A total of seven [12–18] studies reported the VAS scores at the last follow-up. A total of 464 patients were included, including 253 in the experimental group and 211 in the control group. There was high heterogeneity between the two groups (I2 = 59%, p = 0.02), and a random-effects model was used for meta-analysis. The results showed that there was a statistically significant difference in the VAS scores between the two groups Weighted Mean Difference (WMD) = -12.04, 95% CI [-17.35,-6.72], p < 0.00001) (Fig. 4). The VAS score of the experimental group was lower than that of the control group.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot showing the effect of cell therapy on VAS scores of chronic low back pain at Last Follow-up

Time subgroup of VAS

To explore the effect of somatic cell therapy on VAS score at different time points after infusion, we conducted a time subgroup analysis for VAS score (Fig. 5). Pooled analysis showed that the experimental group significantly decreased VAS score (MD = -6.74; 95% CI [-10.60, -2.88], p = 0.0006; heterogeneity test p < 0.00001; I2 = 76%), compared with the control group. Subgroup analysis with random-effects model showed that the experimental group significantly decreased VAS score in two months (MD: -19.30; 95% CI [-24.34, -14.26], p < 0.00001), six months (MD: -10.09; 95% CI [-15.79, -4.40], p = 0.0005), 12 months (MD: -10.78; 95% CI [-17.22, -4.35], p = 0.001) and 36 months (MD: -14.97; 95% CI [-25.90, -4.04], p = 0.007). However, comparisons between the experimental group and the control group showed no difference in one month (MD: 0.63, 95% CI [-8.30, 9.55], p = 0.89), three months (MD: -3.85, 95% CI [− 8.15, 0.46], p = 0.08) and in 24 months (MD: -6.51; 95% CI [-13.95, 0.92]; p = 0.09).

Fig. 5.

Subgroup Analysis of VAS Scores at Different Follow-up Times

Injection subgroup of VAS

To investigate the effect of injecting different types of cells on VAS scores, we conducted an injection subgroup analysis for VAS scores (Fig. 6). Pooled analysis showed that the experimental group significantly decreased VAS scores (MD = -12.04, 95% CI [-17.35, -6.72], p < 0.00001; heterogeneity test p = 0.02; I2 = 59%), compared with the control group. Subgroup analysis with random-effects model showed a significant decrease in VAS scores in the experimental group injected with MPCs (MD: -14.97, 95% CI [-25.90, -4.04], p = 0.007) and with PRP (MD: -15.76, 95% CI [-21.31, -10.21], p < 0.00001). However, comparisons between the experimental group and the control group showed no difference in MSCs group (MD: -2.13, 95% CI [-11.22, 6.96], p = 0.65) and DPCs group (MD: -6.40, 95% CI [-19.09, 6.29], p = 0.32).

Fig. 6.

Subgroup Analysis of VAS Scores for Different Injections (1: The injection substance for the experimental group was MSCs; 2: The injection substance for the experimental group was MPCs; 3: The injection substance for the experimental group was DPCs; 4: The injection substance for the experimental group was PRP)

ODI scores

A total of six [12, 14–18] studies reported the ODI scores at the last follow-up. A total of 413 patients were included, including 218 in the experimental group and 195 in the control group. There was high heterogeneity between the two groups (I2 = 76%, p = 0.0008), and a random-effects model was used for meta-analysis. The results showed that there was a statistically significant difference in the ODI scores between the two groups (WMD = -8.03, 95% CI [-12.84, -3.22], p < 0.00001) (Fig. 7). The ODI score of the experimental group was lower than that of the control group. Follow-up Times subgroup and injection subgroup analysis of ODI Scores are in the supplementary materials (Fig S1, S2).

Fig. 7.

Forest plot showing the effect of cell therapy on ODI scores of chronic low back pain at Last Follow-up

SAE

Among the seven RCTs [12–18] we included, four studies [14– [16, 18] did not report any SAEs, while three studies [12, 13, 17] reported the SAEs. In the study by Gornet et al. [13], four SAEs occurred only in the control group, but the specific details of the SAEs were not reported. In the study by Amirdelfan et al. [17], eight participants in the experimental group experienced SAEs, including one case of implant site infection and one case of severe back pain that led to the discontinuation of the study. In the control group, four participants had SAEs, but none of them were described [17]. In the study by Pers et al. [12], seven participants in both the experimental group and the control group experienced SAEs. Among them, three patients in the experimental group and two patients in the control group experienced severe but transient low back pain exacerbation, which was considered to be related to the study drug or injection procedure. Other SAEs reported in the research [12] included hospitalizations, musculoskeletal disorders, nervous system disorders, infections, oncologic disorders, psychiatric disorders, obstetrical disorders, etc. A total of 298 patients were included, including 170 in the experimental group and 128 in the control group [12, 13, 17]. There was significant heterogeneity between the two groups (I2 = 54%, P = 0.11), and a random effect model was used for the meta-analysis. The results indicated that there was no significant difference between the two groups (OR = 0.70, 95% CI (0.19, 2.64), P = 0.60) (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Forest plot showing Serious Adverse Event (SAE) after cell therapy

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

A total of seven articles were included, so we used a funnel plot to qualitatively analyze publication bias. The VAS, ODI, and SAE after cell therapy for CLBP were basically symmetrical in the funnel plot (Fig S3-S5), indicating that the influence of publication bias was relatively small. In addition, we conducted a sensitivity analysis on VAS, ODI, and SAE (Fig S6-S8). Removing any one study did not affect the significance of the overall effect.

Discussion

Somatic cell therapy is a promising new type of therapy [19, 20]. In our study, we found that the use of somatic cell therapy can significantly reduce the VAS scores and ODI scores of patients with CLBP, without increasing the incidence of SAE. Our work included high-quality RCT studies with a large enough sample size, which can strongly support the effectiveness and safety of cell therapy. In addition, injection subgroup analysis results indicate that the injection of PRP appears to yield significant therapeutic effects, whereas the injection of MSCs does not seem to have such pronounced effects. MPC was found to be effective in one study, which need more investigations to validate. In the time subgroup analysis, we found that there was no significant difference in symptoms between the experimental group and the control group 24 months after treatment.

The mechanism by which cell therapy improves the symptoms of patients with CLBP remains unclear [19]. Some evidence suggests that MSCs mainly exert beneficial effects through mechanisms such as paracrine effects, efferocytosis, and mesodermal differentiation [21]. MPCs are relatively homogeneous cell populations obtained through immunoselection, and they differ from MSCs in terms of cell characteristics and isolation methods [22]. In addition to the mechanisms of MSCs, the surface markers of MPCs may make them more likely to interact with the intervertebral disc tissue and home more effectively to the lesion site, thus exerting a therapeutic effect. PRP contains multiple anti-inflammatory factors such as interleukin-1 receptor antagonists [23–25], which can alleviate inflammation; the adhesion factors and chemokines in it can recruit endogenous stem cells to the nucleus pulposus, promote the regeneration of nucleus pulposus cells, collagen secretion, repair degenerated intervertebral discs, and improve the symptoms of CLBP [26, 27]. It is likely because PRP contains these anti-inflammatory factors, adhesion factors and chemokines that it has a therapeutic effect in the present study. Moreover, the injected cells rapidly die due to immune-mediated damage as well as the lack of nutrition and oxygen, and the half-life of soluble factors and mediators produced by paracrine secretion is short [21], which may explain why the therapeutic effect of somatic cell therapy on CLBP cannot be long-lasting or sustained.

In 2018, Wu et al. [28] carried out the first one-arm meta-analysis on cell therapy for disc-derived low back pain. Their finding that cell therapy can alleviate discogenic low back pain offers preliminary evidence regarding the effectiveness of this therapeutic approach. Later in the same year, Sanapati et al. [29] published a study that comprehensively assessed the efficacy of MSCs and PRP injections in treating CLBP and lower limb pain. Regrettably, among the included studies, high-quality RCTs were scarce. Most of them were observational studies and case reports, which significantly restricted the strength of the evidence. In 2021, Xie et al. [19] conducted a meta-analysis and discovered that MSC therapy could notably reduce the VAS and ODI scores in patients with DDD. In 2023, Zhang et al. [30] systematically and comprehensively evaluated the efficacy and safety of MSCs in treating lumbar discogenic pain. However, this study only analyzed the clinical efficacy and safety of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), excluding cells from other sources. As a result, its findings may not be applicable to other types of intercellular therapies. The study by Zhang et al. [31] in 2024 provides a more comprehensive reference for clinical treatment. However, the maximum follow-up period was only six months, making it impossible to evaluate the long-term effects of PRP and other therapies and to determine whether there were any delayed adverse effects.

Our work incorporates existing high-quality RCT studies with a sufficiently large sample size to strongly support the efficacy and safety of cell therapy. Subgroup analysis was performed with different injections and different follow-up times. The conclusion obtained has relatively high reliability and wide applicability. However, our study also has some limitations. Firstly, we only included high quality RCTs, which may have led us to ignore evidence from other important research types such as observational studies such as cohort studies, case-control studies, etc. Secondly, although we conducted subgroup analysis of different injectors, we could not fully guarantee the homogeneity of each study within the same subgroup of injectors, and the extraction, culture, and injection processes of injectors may be different. Third, subgroup analysis with different follow-up times found no significant differences in VAS and ODI at 24 months. We speculate that cell therapy for CLBP may fail after two years, and more studies including long-term follow-up data are needed to further determine the long-term effectiveness of cell therapy. Finally, our study did not directly compare somatic cell therapies with other non-cell-based therapies that might affect the injection site (such as local injection of cytokines like Insulin-like Growth Factor-1, Platelet-Derived Growth Factor or other effective drugs). Therefore, this study cannot determine the specific mechanism of cell therapy for chronic low back pain or judge whether cell therapy is more effective than directly injecting its non-cellular components or other effective drugs.

Future studies may need to pay attention to the comparison of the curative effects of cell therapies and non-cell therapies in treating chronic low back pain and develop a standard for all types of cell therapy and conduct more multi-center, large-sample, long-term, high-quality studies to further clarify the long-term effectiveness of cell therapy for CLBP. If the cell therapy fails after a certain period, then it is necessary to study whether continuing the cell therapy again has a good effect, and it is necessary to find out the appropriate time to give another injection.

Conclusion

Somatic cell therapy has a certain therapeutic effect on CLBP, which can effectively reduce the pain level of patients and improve lumbar spine dysfunction. This treatment method does not increase the incidence of SAE under current research conditions. However, the effect of a single cell therapy seems to last no more than two years which still needs more long-term studies to be verified. In summary, somatic cell therapy for CLBP is a safe and effective therapy, but its long-term efficacy still awaits further verification.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1. Extracted data from RCTs.

Acknowledgements

The authors declare that they have not used AI-generated work in this manuscript. We would like to clarify that no outsourcing work was involved in any stage of the study, from the literature search and data extraction to the statistical analysis and manuscript writing. All the work was independently carried out by the listed authors.

Abbreviations

- CLBP

Chronic low back pain

- RCTs

randomized controlled trials

- VAS

Visual analogue scale

- ODI

Oswestry disability index

- SAE

Serious adverse events

- NSAIDs

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor-beta

- IGF-1

Insulin-like Growth Factor-1

- PDGF

Platelet-derived growth factor

- bFGF

Basic fibroblast growth factor

- IDO

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- IL-10

Interleukin-10

- PRISMA

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- MSCs

Mesenchymal stem cells

- DPCs

Disc progenitor cells

- MPCs

Mesenchymal precursor cells

- PRP

Platelet-rich plasma

- HA

Hyaluronic acid

- MD

Mean difference

- OR

Odds ratios

- CIs

Confidence intervals

- WMD

Weighted mean difference

- DDD

Degenerative disc disease

- BMSCs

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

Author contributions

WY T, and YH Y led on the conception and design of the study. ZH L, YM S, YK Z and SR L searched, extracted, and critically appraised the studies included in the analysis. ZH L planned and performed the statistical analyses. ZH L and YM S wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings and the final draft of the paper. H L and all other authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Provincial Natural Science Foundation of Hunan (2020JJ4907).

Data availability

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This program of systematic evaluation and meta-analysis has previously been registered with PROSPERO (CRD42024625727). Because the study did not involve human participants, consent to participate was not required.

Consent for publication

All authors agreed to publish this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yuanheng Yang, Email: yuanhengyang@csu.edu.cn.

Wuyuan Tan, Email: darma_tan@aliyun.com.

References

- 1.Collaborators G. 2019 D and I. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Lond Engl. 2020;396(10258):1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Vlaeyen JWS, Maher CG, Wiech K, Van Zundert J, Meloto CB, Diatchenko L, et al. Low back pain. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2018;4(1):52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson GB. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. Lancet. 1999;354(9178):581–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GBofDS2013C. Global, regional, and National incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet Lond Engl. 2015;386(9995):743–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dagenais S, Caro J, Haldeman S. A systematic review of low back pain cost of illness studies in the united States and internationally. Spine J Off J North Am Spine Soc. 2008;8(1):8–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Migliorini F, Maffulli N, Eschweiler J, Betsch M, Catalano G, Driessen A, et al. The Pharmacological management of chronic lower back pain. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2021;22(1):109–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA, for the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians*. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American college of physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(7):514–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choy EHS, Mease PJ, Kajdasz DK, Wohlreich MM, Crits-Christoph P, Walker DJ, et al. Safety and tolerability of Duloxetine in the treatment of patients with fibromyalgia: pooled analysis of data from five clinical trials. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28(9):1035–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drazin D, Rosner J, Avalos P, Acosta F. Stem cell therapy for degenerative disc disease. Adv Orthop. 2012;2012:961052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakai D, Schol J. Cell therapy for intervertebral disc repair: clinical perspective. J Orthop Transl. 2017;9:8–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quantifying heterogeneity in. a meta-analysis - PubMed [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 25]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12111919/

- 12.Pers YM, Soler-Rich R, Vadalà G, Ferreira R, Duflos C, Picot MC, et al. Allogenic bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stromal cell–based therapy for patients with chronic low back pain: a prospective, multicentre, randomised placebo controlled trial (RESPINE study). Ann Rheum Dis. 2024;83(11):1572–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gornet MF, Beall DP, Davis TT, Coric D, LaBagnara M, Krull A, et al. Allogeneic disc progenitor cells safely increase disc volume and improve pain, disability, and quality of life in patients with lumbar disc Degeneration—Results of an FDA-Approved biologic therapy randomized clinical trial. Int J Spine Surg. 2024;18(3):237–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saraf A, Hussain A, Sandhu AS, Bishnoi S, Arora V. Transforaminal injections of Platelet-Rich plasma compared with steroid in lumbar radiculopathy: A prospective, Double-Blind randomized study. Indian J Orthop. 2023;57(7):1126–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao ZL, Xu H, Wu JQ, Dai JH, Lin SJ, Zou LF et al. The Clinical Efficacy of Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma Interventional Circulatory Perfusion Combined with Radiofrequency Ablation and Thermocoagulation in the Treatment of Discogenic Low Back Pain. Wan C, editor. Int J Clin Pract. 2023;2023:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Won SJ, Kim Dye, Kim JM. Effect of platelet-rich plasma injections for chronic nonspecific low back pain: A randomized controlled study. Med (Baltim). 2022;101(8):e28935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amirdelfan K, Bae H, McJunkin T, DePalma M, Kim K, Beckworth WJ, et al. Allogeneic mesenchymal precursor cells treatment for chronic low back pain associated with degenerative disc disease: a prospective randomized, placebo-controlled 36-month study of safety and efficacy. Spine J. 2021;21(2):212–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noriega DC, Ardura F, Hernández-Ramajo R, Martín-Ferrero MÁ, Sánchez-Lite I, Toribio B, et al. Intervertebral disc repair by allogeneic mesenchymal bone marrow cells: A randomized controlled trial. Transplantation. 2017;101(8):1945–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie B, Chen S, Xu Y, Han W, Hu R, Chen M, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of human mesenchymal stem cell therapy for degenerative disc disease: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stem Cells Int. 2021;2021:9149315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schol J, Tamagawa S, Volleman TNE, Ishijima M, Sakai D. A comprehensive review of cell transplantation and platelet-rich plasma therapy for the treatment of disc degeneration-related back and neck pain: A systematic evidence-based analysis. JOR Spine. 2024;7(2):e1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng BG, Yan XJ. Barriers to mesenchymal stromal cells for low back pain. World J Stem Cells. 2022;14(12):815–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mesodermal Progenitor Cells. (MPCs) Differentiate into Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSCs) by Activation of Wnt5/Calmodulin Signalling Pathway - PMC [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 9]. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3183072/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.O’Shaughnessey KM, Panitch A, Woodell-May JE. Blood-derived anti-inflammatory protein solution blocks the effect of IL-1β on human macrophages in vitro. Inflamm Res Off J Eur Histamine Res Soc Al. 2011;60(10):929–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng PG, Yang KD, Huang LG, Wang CH, Ko WS. Comparisons of cytokines, growth factors and clinical efficacy between Platelet-Rich plasma and autologous conditioned serum for knee osteoarthritis management. Biomolecules. 2023;13(3):555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baltzer AWA, Moser C, Jansen SA, Krauspe R. Autologous conditioned serum (Orthokine) is an effective treatment for knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17(2):152–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawabata S, Akeda K, Yamada J, Takegami N, Fujiwara T, Fujita N, et al. Advances in Platelet-Rich plasma treatment for spinal diseases: A systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(8):7677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen WH, Liu HY, Lo WC, Wu SC, Chi CH, Chang HY, et al. Intervertebral disc regeneration in an ex vivo culture system using mesenchymal stem cells and platelet-rich plasma. Biomaterials. 2009;30(29):5523–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu T, Song H, xin, Dong Y, Li Jhua. Cell-Based therapies for lumbar discogenic low back pain systematic review and Single-Arm Meta-analysis. Spine. 2018;43(1):49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanapati J, Manchikanti L, Atluri S, Jordan S, Albers SL, Pappolla MA, et al. Do regenerative medicine therapies provide Long-Term relief in chronic low back pain: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Pain Physician. 2018;21(6):515–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang W, Wang D, Li H, Xu G, Zhang H, Xu C, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells can improve discogenic pain in patients with intervertebral disc degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023;11:1155357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang X, Zhang A, Guan H, Zhou L, Zhang J, Yin W. The clinical efficacy of Platelet-Rich plasma injection therapy versus different control groups for chronic low back pain: A network Meta-Analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Pain Res. 2024;17:1077–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1. Extracted data from RCTs.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.