Abstract

The Multiphase Optimization STrategy (MOST) is a framework that uses three phases—preparation, optimization, and evaluation—to develop multicomponent interventions that achieve intervention EASE by strategically balancing Effectiveness, Affordability, Scalability, and Efficiency. In implementation science, optimization of the intervention requires focus on the implementation strategies—things that we do to deliver the intervention—and implementation outcomes. MOST has been primarily used to optimize the components of the intervention related to behavioral or health outcomes. However, innovative opportunities to optimize discrete (i.e. single strategy) and multifaceted (i.e. multiple strategies) implementation strategies exist and can be done independently, or in conjunction with, intervention optimization. This article details four scenarios where the MOST framework and the factorial design can be used in the optimization of implementation strategies: (i) the development of new multifaceted implementation strategies; (ii) evaluating interactions between program components and a discrete or multifaceted implementation strategies; (iii) evaluating the independent effects of several discrete strategies that have been previously evaluated as a multifaceted implementation strategy; and (iv) modification of a discrete or multifaceted implementation strategy for the local context. We supply hypothetical school-based physical activity examples to illustrate these four scenarios, and we provide hypothetical data that can help readers make informed decisions derived from their trial data. This manuscript offers a blueprint for implementation scientists such that not only is the field using MOST to optimize the effectiveness of an intervention on a behavioral or health outcome, but also that the implementation of that intervention is optimized.

Keywords: intervention optimization, methods, implementation science, social theory, systems theory, youth

Lay summary

The Multiphase Optimization STrategy (MOST) is a method used to create interventions that work well, are cost-effective, and can be used widely. Normally, MOST focuses on making interventions better at improving health or behaviors. This article demonstrates that MOST can also improve how interventions are implemented and provide four examples: (i) the development of a new multipart implementation plan; (ii) evaluating how different parts of an intervention and its implementation plan work together; (iii) evaluating how different parts of a multipart implementation plan work alone and in combination; and (iv) modification of an implementation plan for local context. This article is meant to help scientists who work on putting interventions into practice. It shows how MOST can make interventions better and make sure they are used well in different places. By focusing on both the intervention and the implementation plan, we can do a better job of using interventions that have been proven to work in real life.

Introduction

The Multiphase Optimization STrategy (MOST) is a framework to develop multicomponent interventions that achieve intervention EASE by strategically balancing Effectiveness, Affordability, Scalability, and Efficiency [1–3]. Inherently, most is an implementation-forward framework because the dissemination and implementation of an intervention are considered from the outset (i.e. optimization objective), rather than waiting to first determine effectiveness before considering the context or parameters in which an intervention will ultimately be deployed [4, 5]. MOST has been used predominantly in effectiveness research to test how program components affect a behavioral or health outcome [6–9]. In contrast to the classic treatment package approach [1], in which an intervention is evaluated as a package using a randomized controlled trial (RCT), interventions developed and optimized using MOST employ a variety of experimental designs [e.g. factorial, sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART) or microrandomized trials (MRT)] to optimize which individual intervention components should be included as part of a larger intervention package [1, 10]. The optimization process offers information about the performance of components independently and in combination, advancing science.

Implementation scientists often start with an evidence-based intervention (EBI) that is effective at improving a behavioral or health outcome but that may need a new or modified implementation plan [11, 12]. In this case, optimization of the intervention plan requires a focus on the implementation strategies—things that implementers do to deliver the intervention—and implementation outcomes [13–15]. An extensive list of discrete implementation strategies (i.e. a single strategy that supports program delivery) currently exists [13, 16]; however, in practice, most implementers generally use multifaceted implementation strategies (i.e. packages of implementation strategies) within their implementation plan.

Discrete implementation strategies are building blocks (e.g. training, program champions, learning coalitions) that can be used to construct multifaceted implementation strategies [13, 16]. However, when organizations are asked to use multiple discrete implementation strategies at once (as a package), it is unknown whether each strategy has a positive, negative, or null effect on implementation outcomes or how the strategies work in the presence (or absence) of one another. To achieve public health impact, it is imperative we understand how discrete strategies can be combined [17].

Commonly, multiple discrete implementation strategies are evaluated together as a multifaceted implementation strategy (i.e. implementation strategy package), usually via an RCT through which they are compared with a suitable control condition [18–20]. This approach has numerous limitations, including ad hoc modification of the multifaceted implementation strategy when used in new settings, an inability to identify which of the discrete strategies drive the desired result, and an inability to evaluate interactions between discrete strategies [21, 22]. Although evaluating a multifaceted implementation strategy in comparison to a control condition or the standard of care is important, the amount of detail provided by other experimental designs can provide additional guidance on the discrete strategies, interactions between discrete strategies, as well as inform future research that aims to use the multifaceted strategy in a new setting—other important goals in the field of implementation science [20, 23, 24].

In MOST, a commonly used experimental design for an optimization RCT is the 2k factorial experiment [25, 26]. A full discussion on the design of factorial trials is beyond the scope of this article; see Collins [1]. Briefly, factor (k) can be used to evaluate the performance of a discrete implementation strategy independently (i.e. main effect), and in combination (i.e. interactions). The factorial experimental design allows the researcher to examine all possible combinations of candidate strategies. Factorial 2k experiments are efficient because all participants contribute to the estimation of all effects, and a researcher can add additional candidate strategies (and, thus, experimental conditions) without increasing the required number of participants in the experiment [23]. Optimization RCTs provide empirical information that investigators can use to make decisions about which discrete strategies should be tested as a package vs. a suitable control condition in an evaluation RCT.

Integrating principles of intervention optimization with implementation science can advance the goal of designing effective interventions that can be widely disseminated and implemented. A 2021 commentary by Guastaferro and Collins offered three areas of focus where MOST can be applied in the field of implementation science [8]. We expand on these recommendations by detailing four scenarios using MOST to optimize implementation strategies via factorial experiment. We also provide hypothetical school-based physical activity examples that use factorial experiments to demonstrate these scenarios. The intention is not to provide explicit guidance or parameters for using a factorial experiment within implementation science, but rather to inspire the integration of MOST and implementation science to advance the field.

Scenarios

The following scenarios describe how the factorial experiment may be applied to answer sequenced scientific questions about implementation strategies. Note, implementation strategies selected in the scenarios that follow are not meant to serve as explicit recommendations but rather were selected for illustrative purposes.

Development of new multifaceted implementation strategies

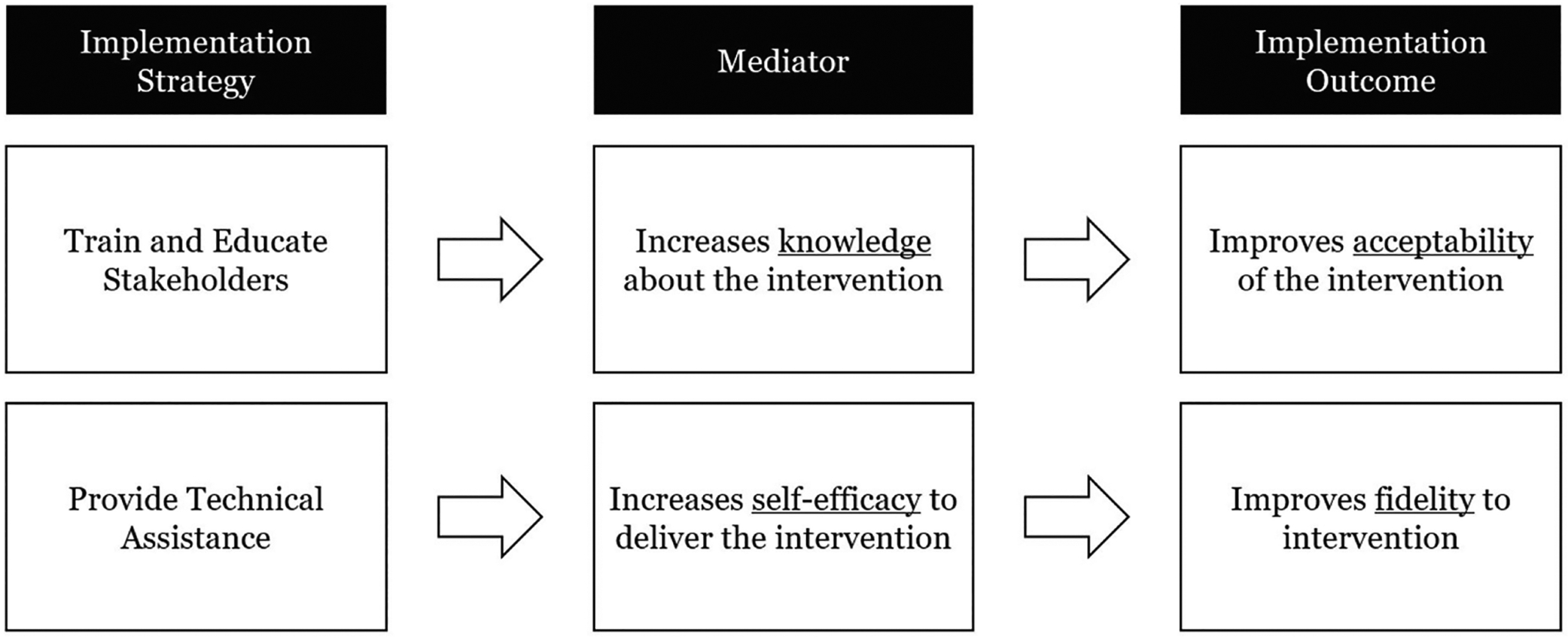

The conceptual model developed in the preparation phase of MOST (Fig. 1) specifies the discrete implementation strategies being considered for inclusion, the target mediator(s) that the strategy is hypothesized to address, and the expected outcome of changing that mediator [27–29]. Mediators in implementation science are best conceptualized as psychosocial behavioral determinants, barriers, and facilitators affecting program implementation. At the individual-level mediators may include psychosocial behavioral determinants such as knowledge of the intervention, self-efficacy for delivering the intervention, or attitudes toward the intervention, among other constructs [30, 31]. Existing behavior change theories (e.g. social cognitive theory, theory of planned behavior) are often used to identify individual-level mediators that a discrete implementation strategy will target [32, 33]. At the organization or community level, implementation science frameworks, such as the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) or organizational readiness, can be useful in identifying target barriers or facilitators that are mediators (e.g. organizational climate, communication) [34, 35]. Regardless of the level of the targeted mediators, implementation outcomes remain relatively consistent (e.g. acceptability, feasibility) but it is important to specify the level at which they are targeted (i.e. individual vs. organization level) in the conceptual model [36]. Specifying the level of these outcomes is important because it has implications for how they are measured, intervened upon, and analyzed as part of the study.

Figure 1.

A hypothetical conceptual model for two discrete implementation strategies within a multifaceted implementation strategy.

Example 1.

Suppose you are interested in developing a multifaceted implementation strategy to support the use of active breaks—5- to 15-min sessions where teachers introduce short bursts of physical activity into the academic lesson—as an effective approach to increasing physical activity in the school setting [37–39]. Hypothetical pilot work within a school could reveal that schoolteachers do not think that active breaks are acceptable in their setting, they have limited knowledge of how to use active breaks, low self-efficacy for using active breaks, and poor outcome expectations about using active breaks.

To affect knowledge, you select the discrete implementation strategy of conducting educational outreach visits; for self-efficacy, you decide to provide ongoing technical assistance; and for outcome expectations, you have staff shadow other experts. Each implementation discrete strategy is paired with one target mediator hypothesized to affect the acceptability of using active breaks. Using the conceptual model (Fig. 2), you then design an optimization RCT using a factorial experimental design. For example, you would assign each program implementor to receive or not receive each of the discrete implementation strategies (yes vs. no). Using this experimental design, you could assess the main effect of each discrete strategy, as well as interactions between them. Furthermore, it is highly recommended that you also measure hypothesized proximal mediators (e.g. knowledge, self-efficacy, outcome expectations).

Figure 2.

Conceptual model to improve acceptability of active breaks.

Evaluating interactions between program components and a discrete or multifaceted implementation strategy

There is also value in determining how discrete implementation strategies—designed to improve an implementation outcome—interact with program components of an EBI that are designed to target a behavioral or health outcome. This is important because changes to an EBI, including delivery changes, have the potential to influence behavioral or health outcomes [15]. Specifically, effects may be additive (i.e. the positive effect of the implementation strategy summed with the positive effect of the program component), synergistic (i.e. the interaction between the discrete implementation strategy and the program component such that their combined effect is greater than their individual effects), or antagonistic (e.g. the interaction between the discrete implementation strategy and program component such that their combined effect is less than the sum of their individual effects). In implementation science, these types of questions are often addressed via type 2 hybrid implementation-effectiveness trial designs [40].

Example 2.

Building off Fig. 2, you decide that you still want to evaluate the impact of the three discrete implementation strategies on the acceptability of active breaks. However, you also know that the addition of new physical activity equipment to the classroom can have a positive impact on physical activity; thus, you decide to add this as a program component into the EBI. As you are now interested in both implementation strategies and program components, it is important to select an experimental design that allows you to assess implementation (i.e. acceptability) and effectiveness outcomes (i.e. physical activity). You design a 24 factorial experiment (Table 1) in which all sites will receive physical activity breaks (referred to as a constant component as it is not experimentally manipulated). This optimization RCT results in 16 different experimental conditions reflecting all possible combinations of the program components and implementation strategies. Teachers will be recruited as implementers and fill out surveys related to implementation outcomes. You can also have them report on students’ physical activity to evaluate effectiveness. Differential analysis plans will be needed for evaluating implementation vs. effectiveness outcomes. For example, the analysis plan for effectiveness will need to include processes for controlling classroom-level clustering, whereas the plan for implementation outcomes may necessitate the use of statistical tests for smaller sample sizes (e.g. factorial analysis of variance) and prespecified effect sizes that can guide decisions about which components/strategies to keep and/or discard.

Table 1.

Experimental conditions in a 24 factorial design

| Experimental condition | Program components | Implementation strategies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA breaks | New PA equipment | Educational outreach | Technical assistance | Shadow other experts | |

| 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| 3 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 5 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| 7 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 8 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| 9 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 10 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| 11 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| 12 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| 13 | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 14 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| 15 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| 16 | Yes | No | No | No | No |

Notes: Physical activity breaks are a constant component across all conditions. Shading identifies groupings within strategies and components. PA, physical activity.

Suppose the results of this optimization RCT suggest one of the discrete implementation strategies (e.g. technical assistance) improves program acceptability, but decreases levels of student physical activity (potentially by making the breaks less fun). Then, suppose findings demonstrate that decreases in physical activity resulting from the additional technical assistance are offset by the addition of new physical activity equipment resulting in an effect that is equivalent to the original EBI (i.e. active breaks), but with increased acceptability via the technical assistance. Had you used a traditional two-arm RCT, these critically important and nuanced findings would not be available. The results from the optimization RCT using a factorial experiment can help you make important decisions about which program components or strategies to keep or discard.

Evaluating the independent effects of several discrete strategies that have been previously evaluated as a multifaceted implementation strategy

In the translational research spectrum, researchers often focus their initial development efforts on the components of the intervention that produce changes in health behavior or health outcomes, and they place less emphasis on systematically developing or selecting implementation strategies [41, 42]. However, when interventions run into implementation challenges (as most do), or are ready to be scaled up or disseminated, researchers pay more attention to the implementation strategies [43]. Thus, several questions often remain unanswered for existing multifaceted implementation strategies. For example, if a multifaceted strategy was found to improve an implementation outcome, a researcher may still want to know which discrete strategies are driving the outcome or how the discrete strategies interact to help guide modification of the multifaceted strategy for use with another population or differently resourced setting.

It is possible to optimize a multifaceted strategy originally developed and evaluated using the classical treatment package approach. For example, an investigator can use MOST to conduct an optimization RCT that helps to ensure the affordability, scalability, and efficiency of the multifaceted strategy. Results may identify one or more inactive discrete implementation strategies that can be removed, antagonistic interactions between strategies that can be eliminated, or strategies that produce minimal effects and could be dropped. By identifying the key aspects of existing multifaceted implementation strategies and removing null or inactive discrete strategies, the MOST framework can better position a multifaceted implementation strategy to enhance EBI delivery.

Example 3.

Let us say that you developed an intervention where teachers provide students with active breaks. You could have also used a multifaceted implementation strategy where all teachers received some initial education on active breaks, had the opportunity to shadow other experts before the school year started, and were provided ongoing technical assistance. If you found out that the program improved physical activity and was implemented with moderate fidelity, you may want to implement it in other districts. However, before scaling up the program, you want to refine the multifaceted implementation strategy.

To optimize the multifaceted implementation strategy, suppose you decide to conduct a 23 factorial experiment with each discrete implementation strategy identified as a factor. Once completed, you use the empirical data to estimate the main effect of each discrete strategy and interaction effects (assume no three-way interaction). Suppose the estimated marginal mean (i.e. main effect) of each discrete strategy were as follows: educational outreach = 10; technical assistance = 6; and shadow other experts = 5 (note: these results are hypothetical). Fig. 3a demonstrates how it might look if educational outreach and technical assistance had an additive effect (i.e. 10 + 6 = 16). Fig. 3b depicts a synergistic effect between technical assistance and shadowing other experts (i.e. 22 > 6 + 5). Fig. 3c illustrates an antagonistic effect between educational outreach and shadowing other experts (i.e. 12 < 10 + 5). Fig. 3d provides an example of no interaction effects. Using empirical data, we determined that the most impactful multifaceted implementation strategy would be technical assistance plus shadowing other experts. Thus, we could remove educational outreach from the multifaceted implementation strategy in preparation for intervention scale-up.

Figure 3.

(a–d) Four types of effects were found in the optimization trial using the factorial experimental design.

Modifying a discrete or multifaceted implementation strategy for the local context

As implementation strategies are replicated across new settings, ad hoc modifications (e.g. adding or dropping a discrete strategy) can—and likely will—occur in response to resource constraints, differences in the local context identified through a needs assessment, or differences in how stakeholders view the value of an implementation strategy [44, 45]. In theory, if an implementation strategy was developed using MOST from the outset, many elements of the implementation context would have been accounted for in its development. However, we know that new constraints arise all the time.

When a modification is needed for a new context or to respond to a new constraint, a researcher who has used MOST may be able to return to the results of their optimization trial to help select the best combination of discrete implementation strategies that produce the best-expected outcome. That is, data from one optimization trial may be used across multiple contexts and it is not always necessary to conduct an entirely new optimization trial. Should a new optimization trial be needed because the setting or the population are substantially different, the data from the previous trial can provide information about what discrete strategies to consider and discrete strategies that can be excluded. These data will help to improve the efficiency of the process for developing the new multifaceted implementation strategy.

Example 4.

Building off the prior example, Table 2 depicts the estimated implementation effect (Ŷ) and the estimated implementation cost for each of the eight experimental conditions. The results indicate technical assistance plus shadowing other experts produces the best implementation outcome (Experimental Condition 5). However, if a school feels that shadowing other experts is not feasible because they have too many teachers to provide them all with the opportunity to shadow other experts, they will want the next best option that fits their constraints. Results from the optimization trial can empirically identify the next best-performing combination of implementation strategies, which may not be just the removal of the discrete strategy that was not feasible. For example, when shadowing other experts is dropped from the multifaceted implementation strategy and technical assistance is the only remaining implementation strategy, the estimated effect is among the weakest combinations (Experimental Condition 6). Instead, this school can use the optimization trial to choose educational outreach and technical assistance, as it is the combination with the largest effect that does not include shadowing other experts (Experimental Condition 2).

Table 2.

Experimental conditions, estimated implementation effects, and estimated cost

| Experimental condition | Educational outreach | Technical assistance | Shadow experts | Ŷ | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4 | $1700 |

| 2 | Yes | Yes | No | 12 | $1200 |

| 3 | Yes | No | Yes | 16 | $700 |

| 4 | Yes | No | No | 10 | $200 |

| 5 | No | Yes | Yes | 22 | $1500 |

| 6 | No | Yes | No | 5 | $1000 |

| 7 | No | No | Yes | 6 | $500 |

| 8 | No | No | No | 0 | $0 |

Note: Ŷ parsimonious model represents the estimated effect for that combination of strategies and not the effect for participants within that specific experimental group. Cost is the estimated cost per counselor. Shading identifies groupings within strategies.

Another context-specific constraint is budget. Suppose a school has a limited budget and cannot afford the combination that was identified as the most effective multifaceted implementation strategy (Experimental Condition 5 for $1500). The school has a maximum of $1000 to spend. Data may be used to identify the most effective combination of discrete implementation strategies given their budget. In this case, Experimental Condition 3 in which educational outreach plus shadowing other experts is implemented costs $700 and has the second largest estimated effect (Ŷ = 16). Thus, the school has identified the most effective multifaceted implementation strategy obtainable under the constraint of $1000. In this way, using MOST helps schools choose the implementation strategy that best fits their local context, but also produces the best effect within their specified constraints. This is not possible in the classic treatment package approach.

Discussion

Researchers are rapidly developing and testing multifaceted implementation strategies using the classical treatment package approach; however, this results in limitations as we try to modify those implementation strategies to new contexts. If we are to avoid the pitfalls produced by an overreliance on the classical treatment package approach, implementation scientists must consider alternative approaches to developing and testing implementation strategies. The MOST framework is a rigorous and efficient way to advance implementation science and accelerate the delivery of EBIs.

The application of MOST in implementation science is an emerging area of study and, as can be expected, new challenges arise. The assessment of implementation outcomes requires a site to have some knowledge of the effectiveness of the EBI before it can complete a baseline assessment. Furthermore, implementation outcomes may not have a linear relationship with the delivery of an implementation strategy [46]. Often, program implementers are most positive about a program before it is implemented, which decreases as people begin to implement the program, and then, hopefully, increases as time goes on. Thus, more data collection time-points may be needed. Finally, implementation outcomes are only important if they result in improved behavioral or health outcomes. Accordingly, hybrid implementation-effectiveness study designs are important [40]. Curran et al. provide several hybrid study designs (i.e. Types I, II, and III) that differentially emphasize the relative importance of effectiveness or implementation outcomes. Additional types of statistical analysis may also be needed (e.g. mediation models, outcomes weighting) to ensure that changes in implementation outcomes are leading to changes in behavioral or health outcomes [47].

Another notable challenge is understanding if implementation barriers (or outcomes) should be conceptualized at the individual or organization/community level. For example, program acceptability (e.g. how active breaks are received) may be conceptualized at the teacher or school levels, and some discrete implementation strategies (e.g. providing financial resources) could have impacts at the organization and/or individual level. Data at multiple levels create a clustering effect that has implication for powering a study design. The factorial experiment can handle clustering [1], but this is a growing area of inquiry. For example, recent work has led to protocols on multilevel adaptive implementation strategies (MAISYs) [48, 49]. The more MOST is applied increasingly in implementation science, the more guidance will be needed.

The MOST framework guides users to evaluate important details that may be related to the success of the implementation strategy. Proctor et al. recommend that implementation strategy developers define: (i) the strategy enactor, (ii) performance objectives, (iii) implementation strategy targets, (iv) temporality (i.e. when the strategy is used), (v) strategy dose, and (vi) implementation outcome [50]. Each of these decision points could be tested as a factor in an optimization trial (e.g. the principal as the actor, as opposed to the school nurse). However, the level of granularity at which we test these decision points (e.g. 30- vs. 45-min training) should be evaluated against the additional resources required to conduct the study. Furthermore, not all decision points are time (or person) varying, and in that case, an adaptive implementation strategy may be better tested using a different type of experimental design (e.g. SMART, MRT). For example, in a previous study, Kilbourne et al. assessed three discrete implementation strategies—replicating effective programs, coaching, and facilitation—in an SMART trial that compared two multifaceted implementation strategy packages, and the effect of augmenting those packages with time-vary facilitation [47]. Results suggest that the timing of facilitation is important [49].

One major benefit of MOST is the use of optimization objectives, which are the defined balance of intervention Effectiveness against Affordability, Scalability, and Efficiency (i.e. EASE). For example, an optimization objective might specify that a multifaceted implementation strategy can be delivered in no more than 10 h per week or for <$500. As a result, the multifaceted implementation strategy with the largest effect on implementation outcomes may not always be the strategy that is selected. Instead, the fit of the strategy for the population and setting is prioritized. It is important to define optimization objectives with community partners and keeping diversity, equity, and inclusion in mind. This is another open area of inquiry for those working on MOST.

Conclusion

Developing, evaluating, and adapting multifaceted implementation strategies are important for putting EBIs into practice. The MOST framework allows researchers to overcome limitations of the classical treatment package approach by optimizing implementation strategies for effectiveness, but also affordability, scalability, and efficiency. In this article, building off Guastaferro and Collins’s commentary [51], we detailed four ways that MOST can be used in the optimization of implementation strategies. These scenarios are not meant to be exhaustive. Rather, it is our intent that these examples offer an initial guide for implementation scientists to follow in their own research developing and evaluating multifaceted implementation strategies. This is an exciting time for implementation scientists to adopt methods of intervention optimization into their work and to lead the field toward a new generation of EBIs supported by multifaceted implementation strategies.

Implications.

Practice:

Integrating principles of intervention optimization with implementation science can advance the goal of designing effective interventions that can be widely disseminated in practice.

Policy:

Optimization objectives set within the MOST framework can be aligned with policy constraints to ensure that implementation strategies are easily translated into practice.

Research:

Researchers can use the MOST framework to optimize the effectiveness of an intervention on a behavioral or health outcome, but also the implementation of that intervention.

Funding Sources

J.S. is funded (in part) by the Texas A&M AgriLife Institute for Advancing Health Through Agriculture. Some of the ideas presented in this manuscript stem from work funded by J.S.’s American Heart Association Career Development Award (#933664). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Human Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

This study does not involve human participants and informed consent was therefore not required.

Welfare of Animals

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Transparency Statement

Statements about study registration, analytic plan registration, availability of analytic code, and availability of materials are not applicable to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Collins LM. Optimization of Behavioral, Biobehavioral, and Biomedical Interventions: The Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST). New York, NY: Springer, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins LM, Murphy SA, Strecher V. The multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) and the sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART): new methods for more potent eHealth interventions. Am J Prev Med 2007;32:S112–8. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins LM, Kugler KC. Optimization of Behavioral, Biobehavioral, and Biomedical Interventions: Advanced Topics. New York, NY: Springer, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins LM, Nahum-Shani I, Guastaferro K et al. Intervention optimization: a paradigm shift and its potential implications for clinical psychology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2024;20. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-080822-051119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Hara KL, Knowles LM, Guastaferro K et al. Human-centered design methods to achieve preparation phase goals in the multiphase optimization strategy framework. Implement Res Pract 2022;3:26334895221131052. 10.1177/26334895221131052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernstein SL, Dziura J, Weiss J et al. Tobacco dependence treatment in the emergency department: a randomized trial using the multiphase optimization strategy. Contemp Clin Trials 2018;66:1–8. 10.1016/j.cct.2017.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spring B, Pfammatter AF, Marchese SH et al. A factorial experiment to optimize remotely delivered behavioral treatment for obesity: results of the Opt-IN study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28:1652–62. 10.1002/oby.22915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wyrick DL, Tanner AE, Milroy JJ et al. itMatters: optimization of an online intervention to prevent sexually transmitted infections in college students. J Am Coll Health 2022;70:1212–22. 10.1080/07448481.2020.1790571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dionne-Odom JN, Wells RD, Guastaferro K et al. An early palliative care telehealth coaching intervention to enhance advanced cancer family caregivers’ decision support skills: the CASCADE pilot factorial trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 2022;63:11–22. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.07.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guastaferro K, Collins LM. Achieving the goals of translational science in public health intervention research: the multiphase optimization strategy (MOST). Am J Public Health 2019;109:S128–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lobb R, Colditz GA. Implementation science and its application to population health. Annu Rev Public Health 2013;34:235–51. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H et al. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol 2015;3:32. 10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci 2015;10:21. 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook CR, Lyon AR, Locke J et al. Adapting a compilation of implementation strategies to advance school-based implementation research and practice. Prev Sci 2019;20:914–35. 10.1007/s11121-019-01017-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health 2011;38:65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirchner JE, Waltz TJ, Powell BJ et al. Implementation strategies. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK (eds.), Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2017, 245–66. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Fernández ME et al. Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implement Sci 2019;14:1–15. 10.1186/s13012-019-0892-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suman A, Dikkers MF, Schaafsma FG et al. Effectiveness of multifaceted implementation strategies for the implementation of back and neck pain guidelines in health care: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2015;11:1–11. 10.1186/s13012-016-0482-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwak L, Toropova A, Powell BJ et al. A randomized controlled trial in schools aimed at exploring mechanisms of change of a multifaceted implementation strategy for promoting mental health at the workplace. Implement Sci 2022;17:1–16. 10.1186/s13012-022-01230-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powell BJ, Fernandez ME, Williams NJ et al. Enhancing the impact of implementation strategies in healthcare: a research agenda. Front Public Health 2019;7:3. 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wyrick DL, Rulison KL, Fearnow-Kenney M et al. Moving beyond the treatment package approach to developing behavioral interventions: addressing questions that arose during an application of the Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST). Transl Behav Med 2014;4:252–9. 10.1007/s13142-013-0247-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collins LM, Strayhorn JC, Vanness DJ. One view of the next decade of research on behavioral and biobehavioral approaches to cancer prevention and control: intervention optimization. Transl Behav Med 2021;11:1998–2008. 10.1093/tbm/ibab087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bucknall T, Fossum M. It is not that simple nor compelling!: comment on “Translating evidence into healthcare policy and practice: single versus multi-faceted implementation strategies—is there a simple answer to a complex question?”. Int J Health Policy Manage 2015;4:787–8. 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rycroft-Malone J It’s more complicated than that: comment on “Translating evidence into healthcare policy and practice: single versus multi-faceted implementation strategies—is there a simple answer to a complex question?”. Int J Health Policy Manage 2015;4:481–2. 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins LM, Dziak JJ, Li R. Design of experiments with multiple independent variables: a resource management perspective on complete and reduced factorial designs. Psychol Methods 2009;14:202–24. 10.1037/a0015826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins LM, Dziak JJ, Kugler KC et al. Factorial experiments: efficient tools for evaluation of intervention components. Am J Prev Med 2014;47:498–504. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kugler KC, Wyrick DL, Tanner AE et al. Using the Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) to develop an optimized online STI preventive intervention aimed at college students: description of conceptual model and iterative approach to optimization. In: Collins LM, Kugler KC (eds.), Optimization of Behavioral, Biobehavioral, and Biomedical Interventions: Advanced Topics. New York, NY: Springer, 2018, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landoll RR, Vargas SE, Samardzic KB et al. The preparation phase in the multiphase optimization strategy (MOST): a systematic review and introduction of a reporting checklist. Transl Behav Med 2022;12:291–303. 10.1093/tbm/ibab146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Broder-Fingert S, Kuhn J, Sheldrick RC et al. Using the multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) framework to test intervention delivery strategies: a study protocol. Trials 2019;20:1–15. 10.1186/s13063-019-3853-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker TJ, Craig DW, Robertson MC et al. The relation between individual-level factors and the implementation of classroom-based physical activity approaches among elementary school teachers. Transl Behav Med 2021;11:745–53. 10.1093/tbm/ibaa133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szeszulski J, Walker TJ, Robertson MC et al. Differences in psychosocial constructs among elementary school staff that implement physical activity programs: a step in designing implementation strategies. Transl Behav Med 2021;12:237–42. 10.1093/tbm/ibab120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eldredge LKB, Markham CM, Ruiter RA et al. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simons-Morton B, McLeroy K, Wendel M. Behavior Theory in Health Promotion Practice and Research. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scaccia JP, Cook BS, Lamont A et al. A practical implementation science heuristic for organizational readiness: R = MC2. J Commun Psychol 2015;43:484–501. 10.1002/jcop.21698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breimaier HE, Heckemann B, Halfens RJ et al. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR): a useful theoretical framework for guiding and evaluating a guideline implementation process in a hospital-based nursing practice. BMC Nurs 2015;14:1–9. 10.1186/s12912-015-0088-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B et al. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front Public Health 2019;7:64. 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walker TJ, Kohl HW, Bartholomew JB et al. Using implementation mapping to develop and test an implementation strategy for active learning to promote physical activity in children: a feasibility study using a hybrid type 2 design. Implement Sci Commun 2022;3:1–9. 10.1186/s43058-022-00271-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Biddle SJ, Asare M. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: a review of reviews. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:886–95. 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dale LP, Vanderloo L, Moore S et al. Physical activity and depression, anxiety, and self-esteem in children and youth: an umbrella systematic review. Ment Health Phys Act 2019;16:66–79. 10.1016/j.mhpa.2018.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B et al. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care 2012;50:217–26. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lane-Fall MB, Curran GM, Beidas RS. Scoping implementation science for the beginner: locating yourself on the “subway line” of translational research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019;19:1–5. 10.1186/s12874-019-0783-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leppin AL, Mahoney JE, Stevens KR et al. Situating dissemination and implementation sciences within and across the translational research spectrum. J Clin Transl Sci 2020;4:152–8. 10.1017/cts.2019.392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leeman J, Birken SA, Powell BJ et al. Beyond “implementation strategies”: classifying the full range of strategies used in implementation science and practice. Implement Sci 2017;12:1–9. 10.1186/s13012-017-0657-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mackie TI, Ramella L, Schaefer AJ et al. Multi-method process maps: an interdisciplinary approach to investigate ad hoc modifications in protocol-driven interventions. J Clin Transl Sci 2020;4:260–9. 10.1017/cts.2020.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller CJ, Barnett ML, Baumann AA et al. The FRAME-IS: a framework for documenting modifications to implementation strategies in healthcare. Implement Sci 2021;16:1–12. 10.1186/s13012-021-01105-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B et al. ; Treatment Fidelity Workgroup of the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychol 2004;23:443–51. 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strayhorn JC, Collins LM, Brick TR et al. Using factorial mediation analysis to better understand the effects of interventions. Transl Behav Med 2022;12:ibab137. 10.1093/tbm/ibab137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quanbeck A, Almirall D, Jacobson N et al. The balanced opioid initiative: protocol for a clustered, sequential, multiple-assignment randomized trial to construct an adaptive implementation strategy to improve guideline-concordant opioid prescribing in primary care. Implement Sci 2020;15:1–13. 10.1186/s13012-020-00990-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kilbourne AM, Smith SN, Choi SY et al. Adaptive School-based Implementation of CBT (ASIC): clustered-SMART for building an optimized adaptive implementation intervention to improve uptake of mental health interventions in schools. Implement Sci 2018;13:1–15. 10.1186/s13012-018-0808-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci 2013;8:1–11. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guastaferro K, Collins LM. Optimization methods and implementation science: an opportunity for behavioral and biobehavioral interventions. Implement Res Pract 2021;2:26334895211054363. 10.1177/26334895211054363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]