Abstract

The clinical landscape of Gram-positive infections has been reshaped with the introduction of long-acting lipoglycopeptides, particularly dalbavancin and oritavancin. Both agents share broad-spectrum activity against multidrug-resistant pathogens, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant strains, yet differ markedly in pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, resistance profiles, and clinical adoption. This review presents a comprehensive comparative analysis of their structural innovations, distinct pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics, and dual mechanisms of action, supported by minimum inhibitory concentration data across key pathogens. Despite belonging to the same antimicrobial class, these agents exhibit important differences in real-world applications and clinical integration. We highlight real-world evidence supporting off-label use in osteomyelitis, endocarditis, and bloodstream infections, where traditional therapies fall short. Furthermore, we explore resistance development, drug–drug interaction profiles, and outpatient utility, providing actionable insights for optimizing treatment strategies. These findings underscore the need for tailored clinical integration of dalbavancin and oritavancin and spotlight their potential roles in future antimicrobial stewardship frameworks.

Keywords: Antimicrobial resistance, Dalbavancin, Oritavancin, Off-label use, Pharmacokinetics, Antimicrobial stewardship, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Key Summary Points

| Dalbavancin and oritavancin are long-acting lipoglycopeptides used to treat complicated Gram-positive infections. |

| This review compares their mechanisms of action, in vitro potency, resistance patterns, and pharmacokinetics. |

| Dalbavancin demonstrates favorable pharmacokinetics with convenient weekly dosing; oritavancin shows potent activity against vancomycin-resistant strains. |

| Key clinical trials, pediatric studies, and real-world data highlight differences in efficacy, safety, and economic implications. |

| This review aims to guide clinicians in selecting the appropriate agent based on infection type, resistance profile, and patient needs. |

Vancomycin Resistance and the Rise of Next-Generation Lipoglycopeptides

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) was first reported in the 1960s, and has since become a problematic human pathogen responsible for infections in both community and healthcare settings [1]. Despite its name indicating resistance solely to methicillin due to the penicillin binding protein coded by the gene mecA, recent MRSA clinical isolates often exhibit resistance to all β-lactam antibiotics, including cephalosporins and carbapenems, with the exception of certain newer cephalosporins [2]. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has designated MRSA as a serious threat due to its capacity to cause a range of serious antimicrobial resistant (AMR) infections, which are associated with significant morbidity and mortality [3], while the World Health Organization (WHO) includes MRSA in their ‘High Group’ of Bacterial Priority Pathogens List in 2024 [4].

Since the 1980s, the glycopeptide antibiotic vancomycin has been widely used in the treatment for MRSA [5]. Vancomycin’s primary mechanism involves binding to and isolating the Lipid II intermediate, which is crucial for cell wall biosynthesis. It specifically targets the d-alanine-d-alanine (d-Ala-d-Ala) dipeptide sequence within the Lipid II structure (Fig. 1), thereby inhibiting the transpeptidation reaction. This action effectively halts the late-stage bacterial cell wall biosynthesis [6].

Fig. 1.

Primary mode of action of oritavancin and dalbavancin. WTA wall teichoic acid, Und-PP undecaprenyl pyrophosphate, NAG N-acetylglucosamine, NAM N-acetylmuramic acid, D-Glu d-glutamic acid, D-Ala d-alanine, L-Ala l-alanine, L-Lys l-lysine, Gly5 pentaglycine bridge, LIIA-WTA / LIIB-WTA / LIIC-WTA lipid-linked intermediates in WTA biosynthesis, MurG, TagB enzymes involved in peptidoglycan/WTA biosynthesis, C carbon, H hydrogen, O oxygen, N nitrogen, Cl chlorine, OH hydroxyl group, NH/NH2 amide/amine nitrogen (secondary/primary), CH3 (Me) methyl group

Despite its long-standing clinical success, the clinical utility of vancomycin is overshadowed by several drawbacks, such as nephrotoxicity, inconsistent tissue penetration, and ‘red man syndrome’ (primarily pruritus) [7], though the latter was believed to be associated with impure preparations initially employed [8]. Vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) strains (MIC ≥ 16 µg/mL) evade vancomycin by modifying the d-Ala-d-Ala sequence to either d-alanine-d-lactate or d-alanine-d-serine [9]. The former modification prevents vancomycin from recognizing Lipid II, while the latter reduces the antibiotic’s binding affinity by approximately tenfold [9]. On the other hand, vancomycin-intermediate resistant S. aureus (VISA) strains (MIC between 4 and 8 µg/mL) synthesize excessive amounts of peptidoglycan rich in d-alanyl-d-alanine, leading to cell wall thickening and vancomycin binding to free side chains and excessive d-Ala-d-Ala intermediates [10, 11]. Heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (hVISA) are strains that appear to be sensitive to vancomycin (susceptible range of 1–2 µg/mL) but contain a subpopulation of vancomycin-intermediate daughter cells (MIC ≥ 2 or 4 µg/mL). The limited clinical options for MRSA treatment and the growing demand for safe and effective antibiotics have led to the development of two novel lipoglycopeptide antibiotics dalbavancin and oritavancin, which are effective against VRSA and offer improved pharmacological profiles compared to vancomycin [12].

Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), particularly Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium, have emerged as major nosocomial pathogens associated with significant morbidity, especially in immunocompromised and critically ill patients [11, 13]. Their intrinsic resistance to many antibiotic classes, coupled with the acquisition of van genes, limits treatment options and complicates infection control [13]. Although dalbavancin and oritavancin are not approved for the treatment of VRE, both agents are indicated for acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) caused by vancomycin-susceptible E. faecalis [14]. This inclusion expands their clinical utility beyond staphylococcal infections, particularly in polymicrobial or catheter-associated infections involving susceptible enterococci [15–17].

This review critically compares dalbavancin and oritavancin, highlighting their structural innovations, dual antibacterial mechanisms, differences in pharmacodynamic activity, and expanding applications in both inpatient and outpatient care. Drawing on recent in vitro, pharmacokinetic, and real-world efficacy data, we assess their potential to address unmet needs in managing resistant Gram-positive infections and support evolving antimicrobial stewardship strategies to preserve the activity of these important antibiotics.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Historical Perspectives: The Development of Dalbavancin and Oritavancin

In 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved dalbavancin and oritavancin for treating ABSSSI caused by susceptible Gram-positive organisms, including MRSA and VRSA [18–20]. Similar to vancomycin and teicoplanin [21], dalbavancin and oritavancin disrupt bacterial cell wall synthesis by inhibiting the cross-linking of peptidoglycan chains. However, these antibiotics are modified with lipophilic side chains, enhancing their effectiveness against vancomycin-resistant Gram-positive bacteria [22]. It is noteworthy to mention that teicoplanin exhibits approximately 90–95% protein binding, a terminal half-life of 70–100 h, and its pharmacodynamic activity is primarily AUC/MIC-driven, similar to other glycopeptides [21]. Additionally, dalbavancin and oritavancin offer several pharmacological advantages over vancomycin, such as fewer adverse effects, a lower propensity for drug–drug interactions, and a vastly extended half-life that allows for once-weekly dosing interval [23, 24].

Dalbavancin

Dalbavancin, originally designated as BI-397, was discovered in the early 1990s by researchers at Biosearch Italia, derived as a semisynthetic derivative of a fermentation product of Nonomuraea species [25]. Biosearch developed dalbavancin in 1997, focusing on its potential as a long-acting lipoglycopeptide antibiotic with enhanced activity against Gram-positive pathogens, including MRSA [26]. In 2003, Biosearch merged with Versicor to form Vicuron Pharmaceuticals, which advanced dalbavancin into late-stage clinical development. Pfizer acquired Vicuron in 2005, along with the intellectual property rights to dalbavancin [27]. Phase III clinical trials evaluating dalbavancin’s efficacy for ABSSSI were conducted between 2003 and 2005, ultimately supporting its regulatory approval [28, 29]. However, the FDA requested additional clinical data from Pfizer to demonstrate dalbavancin’s non-inferiority compared to vancomycin before granting approval, which delayed the clinical approval process by almost a decade [18, 25].

In 2009, Durata Therapeutics acquired the rights to dalbavancin and conducted two additional phase III trials (DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2), which supported its eventual FDA approval [27]. Dalbavancin was approved by the US FDA in May 2014 and subsequently by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2015 for the treatment of ABSSSI (Table 1).

Table 1.

| Dalbavancin (DALVANCE) | Oritavancin (ORBACTIV) | |

|---|---|---|

| Registered indications | Acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections caused by susceptible Gram-positive bacteria in adult patients | Acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections caused by susceptible Gram-positive bacteria in adult patients |

| Microbiology | S. aureus (including MSSA and MRSA), Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus dysgalactiae, Streptococcus anginosus group (including S. anginosus, S. intermedius, S. constellatus) and vancomycin-susceptible E. faecalis | S. aureus (including MSSA and MRSA), Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus dysgalactiae, Streptococcus anginosus group (includes S. anginosus, S. intermedius, and S. constellatus), and vancomycin-susceptible E. faecalis |

| Dose regimen | 1500 mg single dose or 1000 mg on day 1 followed by 500 mg on day 8; intravenous infusion over 30 min | 1200 mg single dose; intravenous infusion for more than 3 h |

| Adverse effects | Nausea, headache, diarrhea, infusion-site reactions | Nausea, headache, pruritus, vomiting, infusion-site reactions, coagulation test interference |

| Dose adjustment for special population |

For patients with CrCl < 30 mL/min but not on regular hemodialysis: 1125 mg single dose or 750 mg on day 1 followed by 375 mg on day 8 |

MSSA methicillin-susceptible S. aureus, MRSA methicillin-resistant S. aureus, CrCl creatinine clearance

Oritavancin

Oritavancin was first synthesized by Eli Lilly, the same company that discovered vancomycin. After vancomycin hit the market, Eli Lilly anticipated the inevitable emergence of vancomycin resistance [30]. In an attempt to find a druggable glycopeptide superior to vancomycin, Eli Lilly identified chloroeremomycin, a vancomycin analogue with a different central vancosamine sugar. They synthesized and screened over 500 semisynthetic chloroeremomycin analogues and identified LY33328, now known as oritavancin [31, 32]. In 2001, Eli Lilly sold oritavancin to InterMune, which advanced the compound into clinical trials. In 2005, oritavancin was sold to Targanta Therapeutics Corporation, which successfully completed a phase III clinical trial. However, similarly to dalbavancin, in 2008, the FDA declined the approval of oritavancin because of insufficient clinical data demonstrating efficacy [33]. The FDA concluded that the two clinical trials did not sufficiently prove safety and effectiveness for treating complicated skin and soft tissue infections. They recommended additional studies to confirm the drug’s efficacy against MRSA ABSSSI and to monitor macrophage function and phlebitis rates [33]. Following these additional clinical studies, FDA approval was granted in 2014 for use against acute skin infections, followed by EMA approval in 2015 for use against acute skin infections in adults (Table 1) [34].

Chemical Structures and Mechanisms of Action

Dalbavancin

Dalbavancin is a semisynthetic lipoglycopeptide derived from the natural product A40926, a member of the teicoplanin glycopeptide family fermented from actinomycete Nonomuraea spp. [35]. Dalbavancin is chemically synthesized from A40926 through three reaction steps as shown in Fig. 2: (1) selective methyl esterification of the N-acyl amino glucuronic acid; (2) amidation of the carboxy side group (3,3-dimethylaminopropylamide); and (3) saponification of the sugar methyl ester [36]. Compared to A40926, dalbavancin exhibits enhanced antimicrobial activity against staphylococci, especially coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) [37]. The absence of acetylglucosamine in dalbavancin does not broadly impact its antimicrobial activity; however, it improves activity against vancomycin-resistant bacteria namely vanB and vanC enterococci [38].

Fig. 2.

Chemical structure of a dalbavancin and b A40926. C carbon, H hydrogen, O oxygen, N nitrogen, Cl chlorine, OH hydroxyl group, NH2 amide/amine nitrogen, HO2C carboxyl group (–CO2H), Me methyl group (present in panel B).

Reproduced from Alduina et al. [148]. Licensed under CC BY 4.0

Dalbavancin’s mechanism of action is similar to vancomycin, as it binds to the carboxyl-terminal d-Ala-d-Ala terminus of nascent cell wall peptidoglycan and forms a stable complex that impedes peptidoglycan cross-linking by inhibiting transpeptidation [39]. The disruption of cell wall integrity results in autolysis [39]. While dalbavancin’s primary mechanism of action mirrors vancomycin, the lipidic modification of its structure enhances antibacterial activity and improves its pharmacokinetic properties [11]. The lipophilic side chain allows dalbavancin to dimerize and secure its binding pocket at the prime position, enhancing its cooperative binding. Additionally, membrane anchoring via the lipophilic side chain increases binding affinity, facilitating nucleation near its target in the bacterial membrane [36, 40]. The lipophilic side chain also boosts binding to serum proteins, which extends its plasma half-life [41].

Oritavancin

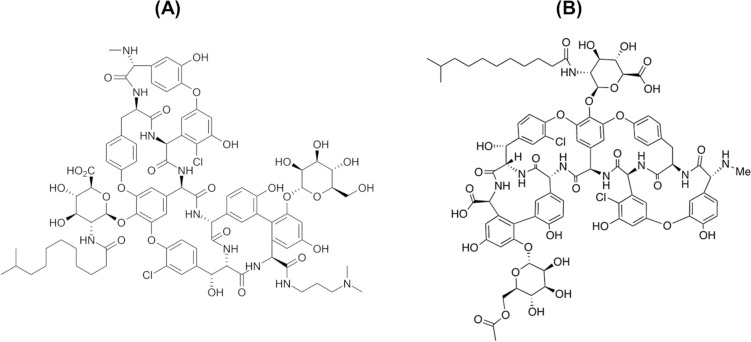

Oritavancin is a semisynthetic derivative obtained from the natural product glycopeptide chloroeremomycin, a secondary metabolite isolated from the fermentation of Kibdelosporangium orienticin [42]. Oritavancin contains a heptapeptide core of five amino acids with aromatic side chains (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Chemical structures of a chloroeremomycin and b oritavancin. C carbon, H hydrogen, O oxygen, N nitrogen, Cl chlorine, OH hydroxyl group, NH/NH2 amide/amine nitrogen (secondary/primary).

Both structures were redrawn with modification from Biondi et al. [42], with permission. Copyright © 2016 Elsevier

Chloroeremomycin differs from vancomycin by the addition of a 4-epi-vancosamine monosaccharide, a sugar moiety at position 1 thought to enhance its antibacterial activity with a reverse of the alcohol chiral center at position 2 (Fig. 3a). Williams et al. discovered that eremomycin, a glycopeptide related to chloroeremomycin, displays an increased killing effect partially due to the sugar attached to position 1, which increased the affinity of the glycopeptide for the d-Ala-d-Ala terminus of the Lipid II intermediate [43]. Empirically, chloroeremomycin did show improved antimicrobial activity against VRSA and VISA [44].

Oritavancin is semisynthetically derived from chloroeremomycin by adding a lipophilic 4-chlorobiphenylmethyl group to the disaccharide sugar linking ring 4 on the amine group (Fig. 3b). Similar to vancomycin and dalbavancin, oritavancin binds to d-Ala-d-Ala; however; the lipophilic 4-chlorobiphenylmethyl side chain on the disaccharide enhances its binding efficiency compared to vancomycin. The hydrophobic interaction between the lipophilic side chain with the bacterial lipid membrane allows oritavancin to anchor and accumulate more effectively on the bacterial cell surface [44]. Additionally, oritavancin dimerizes more effectively than vancomycin, and this property improves its activity independently of d-Ala-d-Ala binding. Upon dimerization, two oritavancin molecules form a large steric blockage homodimer anchored in the bacterial cell membrane, disrupting the cell membrane ultrastructure and contributing to bacterial killing [45]. Notably, this unique secondary mechanism of action allows oritavancin to maintain antibacterial activity against vancomycin-resistant organisms, such as VRSA strains with amino acid mutations such as d-alanine-d-lactate or d-alanine-d-serine.

Unlike vancomycin, which exhibits concentration-independent (time dependent) slow bactericidal killing activity, time-kill studies with oritavancin against VISA and VRSA demonstrated a concentration-dependent killing mechanism [46]. The difference in killing kinetics is attributed to the self-associated dimerization of oritavancin at the membrane surface [47]. Belley et al. employed a fluorescent probe, 3,3-dipropylthiadicarbocyanine iodide, to assess the ability of oritavancin to induce membrane depolarization in a panel of Gram-positive isolates [46]. Their findings demonstrated that oritavancin induces membrane depolarization, which is linked to the insertion of the 4′-chlorobiphenylmethyl group into the bacterial membrane, increasing membrane permeability.

Overall, the rapid concentration-dependent killing demonstrated by oritavancin against Gram-positive pathogens is due to the disruption of cell wall synthesis and the integrity and selective permeability of the bacterial cell membrane.

In Vitro Activity and Mechanisms of Resistance

Dalbavancin

Dalbavancin is FDA approved for treating ABSSSI caused by Gram-positive bacteria including MRSA, streptococci, and vancomycin-susceptible [47]. The FDA has endorsed the dalbavancin MIC breakpoint ≤ 0.25 μg/mL for the treatment of S. aureus on the basis of susceptibility testing of 59,903 clinical isolates [47].

The hydrophobic nature of dalbavancin means that it can bind to the surface of plastic and glass, lowering the effective solution concentration. As a result, the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines for dalbavancin MIC assays require the inclusion of 0.002% polysorbate 80 (P80) [48, 49].

A prospective surveillance study by the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research found dalbavancin to have a MIC50/90 of 0.06/0.06 μg/mL against S. aureus (including MRSA) and E. faecalis; 0.06/0.12 μg/mL against CoNS, ≤ 0.03/≤ 0.03 μg/mL against S. pyogenes ≤ 0.03/0.06 μg/mL against S. agalactiae; and viridans group streptococci [50]. Dalbavancin demonstrated greater antibacterial potency than other glycopeptides, with a MIC90 of 0.06 μg/mL against key Gram-positive pathogens [50]. A comparative summary of MIC ranges for key glycopeptides against selected Gram-positive pathogens is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

In vitro MIC ranges (μg/mL) of glycopeptide antibiotics against major Gram-positive pathogens, summarized from Biondi et al. [42]

| Organism | MIC range (μg/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vancomycin | Oritavancin | Teicoplanin | Dalbavancin | |

| S. aureus methicillin-susceptible | 0.13–1 | 0.13–1 | 0.25–8 | ≤ 0.03–0.5 |

| S. aureus methicillin-resistant | 0.5–4 | 0.13–4 | 0.13–8 | 0.06–1 |

| S. aureus vancomycin-intermediate | 8 | 1–8 | 8–32 | 2 |

| S. epidermidis methicillin-susceptible | 0.13–1 | 0.25–1 | 0.25–16 | ≤ 0.03–0.25 |

| S. epidermidis methicillin-resistant | 1–4 | 0.25–4 | 1–16 | ≤ 0.03–1 |

| S. haemolyticus methicillin-susceptible | 1–4 | 0.06–1 | 1–32 | ≤ 0.03–0.25 |

| S. haemolyticus methicillin-resistant | 0.5–8 | 0.13–1 | 2–128 | ≤ 0.03–4 |

| CoNS methicillin-susceptible | 0.5–2 | 0.06–0.5 | 0.13–4 | ≤ 0.03–0.13 |

| CoNS methicillin-resistant | 0.5–4 | ≤ 0.03–0.5 | 0.06–32 | ≤ 0.03–0.13 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 0.5 | 0.016–0.13 | 0.008–0.06 | ≤ 0.002–0.06 |

| S. pneumoniae penicillin-susceptible | 0.13–0.5 | ≤ 0.002–0.06 | 0.008–0.06 | 0.016–0.13 |

| S. pneumoniae penicillin-resistant | 0.25–2 | ≤ 0.002–0.06 | 0.016–0.13 | 0.008–0.13 |

| Viridans streptococci | 0.25–2 | NA | ≤ 0.12–2 | ≤ 0.03–0.06 |

| Penicillin-susceptible streptococci | 0.12–1 | ≤ 0.01 | ≤ 0.01–0.5 | NA |

| Penicillin-resistant streptococci | 0.25–1 | 0.01–0.06 | ≤ 0.01–0.5 | NA |

| β-Hemolytic streptococci | 0.25–1 | NA | ≤ 0.12–0.25 | ≤ 0.03–0.12 |

| Enterococcus spp. vancomycin susceptible | 0.25–4 | 0.06–0.25 | 0.13–0.5 | 0.06–0.13 |

| Enterococcus spp. VanA | > 128 | 0.06–1 | 64 to > 128 | 0.5 to > 128 |

| Enterococcus spp. VanB | 8–128 | ≤ 0.03–0.13 | 0.13–8 | 0.02–2 |

| Enterococcus spp. VanC | 4–16 | ≤ 0.03–1 | 0.125–4 | NA |

| Bacillus spp. | ≤ 0.12–1 | ≤ 0.015–0.5 | ≤ 0.12–4 | ≤ 0.03–2 |

| Corynebacterium spp. | 0.25–0.5 | NA | ≤ 0.12–1 | ≤ 0.03–0.12 |

| Listeria spp. | 0.25–2 | ≤ 0.03–0.125 | 0.06–0.25 | NA |

| Clostridium difficile | 0.5–4 | 0.016–2 | 0.064–0.5 | 0.125–0.5 |

| Clostridium perfringens | 0.025–4 | 0.016–2 | 0.064–4 | 0.03–0.125 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | ≥ 16 | 16–32 | NA | 8–64 |

CoNS coagulase-negative staphylococci; NA not assessed; VanA vancomycin-resistance gene cluster A; VanB vancomycin-resistance gene cluster B; VanC vancomycin-resistance gene cluster C

Dalbavancin showed synergism with only oxacillin against MRSA, methicillin-resistant CoNS, and VISA isolates, suggesting potential clinical use for this combination [18]. However, dalbavancin’s MIC90 was > 4 μg/mL against both vancomycin-resistant E. faecalis and vancomycin-resistant E. faecium, whereas oritavancin had a more than 30-fold lower MIC against vancomycin-resistant enterococci [50, 51].

Resistance to dalbavancin is rarely observed among staphylococci and streptococci. Dalbavancin remained effective against glycopeptide-resistant strains, with minimal MIC90 shifts (0.12–0.25 μg/mL). No resistance was observed in S. aureus ATCC 25923 following 24 passages with sub-MIC concentrations of dalbavancin [52]. In Gram-positive organisms, resistance to dalbavancin was only observed in intrinsically glycopeptide-resistant enterococci and VRSA. Even VISA and hVISA strains exhibited increased susceptibility to dalbavancin compared to vancomycin [50, 53]. Enterococci with a vanA operon or other microorganisms carrying over vanA from enterococcal species became resistant to dalbavancin by changing peptidoglycan precursors from d-alanyl-d-alanine to d-alanyl-d-lactate [54]. Since dalbavancin is not an activator of the vanB operon, the expression of the vanB gene cluster cannot confer resistance. Not unlike teicoplanin, dalbavancin is also active against intrinsically vancomycin-resistant enterococcal species which express the vanC operon [50]. Additionally, staphylococci appear to be slower to develop resistance against dalbavancin compared to vancomycin [55]. However, despite its favorable resistance profile, recent studies have begun to document emerging instances of dalbavancin resistance under specific clinical and genetic conditions. Dalbavancin resistance has been observed in VISA and S. epidermidis clinical isolates, with mutations such as an Ile78 deletion in the yvqF gene linked to cross-resistance with vancomycin. Its prolonged half-life may increase the risk of resistance emergence by extending the mutant selection window [56, 57].

Dalbavancin has also demonstrated notable antibiofilm activity, particularly against S. aureus and S. epidermidis. A study by Žiemytė et al. showed that dalbavancin not only inhibited biofilm formation at low concentrations (MBIC 0.5–2 mg/L) but was also uniquely effective in halting the growth of already-established biofilms when compared to other antibiotics like vancomycin and linezolid [58]. Moreover, dalbavancin reduced biofilm formation dose-dependently and showed synergy with ficin, though antagonism was observed with N-acetylcysteine [58]. This suggests that dalbavancin is a promising candidate for treating biofilm-associated infections, particularly those related to prosthetic devices and persistent staphylococcal infections. Complementary findings by Yan et al. further supported this, reporting a minimum biofilm bactericidal concentration (MBBC90) of 4 μg/mL for S. aureus and 8 μg/mL for methicillin-resistant S. epidermidis, highlighting its sustained activity against biofilm-embedded cells [59].

Oritavancin

The in vitro antimicrobial spectrum of oritavancin is similar to that of dalbavancin [60]. Oritavancin was active against 99.7–99.89% of 3875 S. aureus isolates from the US and Europe in a 2018 report, with MICs below the FDA susceptible breakpoint of 0.12 µg/mL for S. aureus [60]. Oritavancin MIC90, 0.06 µg/mL demonstrated greater potency against staphylococci compared to comparator antibiotics, being 8-, 16-, and 32-fold lower than daptomycin (0.5 µg/mL), vancomycin (1 µg/mL), and linezolid (2 µg/mL), respectively [61]. CoNS, an oxacillin-resistant isolate with a susceptibility rate of 23.5%, was reported to be susceptible to oritavancin with a MIC90 of 0.06 µg/mL [60]. Additionally, hVISA and VISA showed less resistance to oritavancin compared to vancomycin.

Oritavancin is prone to nonspecific binding to polystyrene microplates, which can result in a significant underestimation of its antimicrobial potency. Studies have shown that the inclusion of 0.002% polysorbate 80 during broth microdilution testing dramatically improves oritavancin recovery and lowers the observed MICs by up to 32-fold for S. aureus and 16-fold for E. faecalis compared to assays without the surfactant. Accordingly, the CLSI now recommends the use of polysorbate 80 in susceptibility testing for oritavancin to ensure reproducibility and comparability across laboratories [62, 63].

Oritavancin is highly active against streptococci with a MICs ranging from 0.0005 to 0.5 µg/mL against S. pneumoniae [61]. It also shows significant activity against β-hemolytic streptococci with MIC90 values ranging from 0.12 to 0.25 µg/mL [64]. Compared to dalbavancin and other comparator agents, oritavancin exhibits exceptional in vitro potency against enterococci. For E. faecalis, oritavancin has a MIC50/90 of 0.03/0.03 µg/mL for vancomycin-susceptible isolates and 0.5/1 µg/mL for vancomycin-resistant isolates. Against vancomycin-susceptible and vancomycin-resistant E. faecium, oritavancin displays a MIC50/90 of 0.015/0.015 µg/mL and 0.06/0.25 µg/mL, respectively [51].

In vitro studies indicate that oritavancin demonstrates strong bactericidal activity against non-dividing MRSA and MRSA-hVISA isolates, unlike dalbavancin and vancomycin [65]. The ability to maintain bactericidal activity against non-dividing bacteria is likely due to its ability to disrupt bacterial membrane integrity, making it beneficial for treating infection sites that typically harbor bacteria in the non-dividing or dormant state, which are particularly challenging to clear [65].

Oritavancin resistance occurs only when there is complete replacement of the crucial amino acid block d-Ala-d-Ala. In a 10-day multistep resistance selection study with VRSA isolated at Hershey Medical Center, oritavancin MICs increased by only two- to fourfold. In contrast, vancomycin, teicoplanin, and dalbavancin MICs increased by 32- to 128-fold [66].

In vitro agar-dish-based drug resistance studies have shown that vanA and vanB phenotype enterococci exhibit moderate-level resistance to oritavancin [67, 68]. Mutations in the vanS(B) sensor gene, which enable activation by teicoplanin or lead to constant expression of the vanB cluster, result in resistance to oritavancin (MIC 8–16 µg/mL). Overproduction of VanH, VanA, and VanX proteins, involved in the synthesis of d-alanyl-d-lactate and d-Ala-d-Ala hydrolysis, also confers resistance to oritavancin (MIC 16 µg/mL). In some vanA and vanB type strains, mutations in the d-Ala-d-Ala ligase contribute to oritavancin resistance, though the MICs remained below 16 µg/mL. Additionally, the vanZ gene within the vanA cluster provides resistance to oritavancin (MIC 8 µg/mL) through an unidentified mechanism. These findings suggest that VanA and VanB-type enterococci can develop moderate resistance to oritavancin (MIC ≤ 16 µg/mL) through multiple mechanisms in a single step [67, 68].

In addition to its broad-spectrum Gram-positive activity, oritavancin has demonstrated potent antibiofilm activity against S. aureus and S. epidermidis strains isolated from prosthetic joint infections. In vitro testing showed minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration at 90% (MBIC90) values of 2 μg/mL and 4 μg/mL, and MBBC90 values of 4 μg/mL and 8 μg/mL for S. aureus and methicillin-resistant S. epidermidis, respectively [69]. These concentrations are below the maximum non-protein-bound plasma levels achieved with standard dosing, supporting the potential role of oritavancin in treating biofilm-associated infections, particularly those involving prosthetic devices or indwelling catheters [69].

Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Characteristics

Dalbavancin

Like other glycopeptide antibiotics, dalbavancin has poor oral absorption, making IV injection the only viable route of administration [70]. In healthy patients, the elimination half-life of dalbavancin is 8.5 days (204 h), with the terminal elimination phase lasting for approximately 14.5–16.5 days (Fig. 4) [47, 71]. This extended half-life is due to its lipidic moiety, which confers high protein binding in human plasma (93% bound, primarily to albumin) [70]. This long half-life allows for a convenient dosing regimen, such as once-a-week injections, which facilitates improved patient compliance.

Fig. 4.

Dalbavancin plasma concentration in 10 healthy volunteers following once-weekly intravenous administration over 30 min of 1000 mg on day 1 and 500 mg on day 8 [47]. Redrawn and based on data from US FDA, NDA 021883S007 Clinical Pharmacology and Biopharmaceutics Review

The FDA has approved two dosage regimens for dalbavancin: 1500 mg single-dose and a two-dose regimen involving IV administration of 1000 mg over 30 min on day 1, followed by 500 mg weekly as a complete treatment cycle [47]. Phase I studies showed that the maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and the area under the exposure curve over 24 h (AUC0–24h) increased in a dose-proportional manner with increasing dalbavancin doses ranging from 140 to 1500 mg, indicating linear pharmacokinetics [72]. The Cmax of dalbavancin was 285 ± 31 mg/L at 0.75 h post-infusion of a single 1000 mg dose in healthy volunteers. For most patients, the plasma concentration of unbound dalbavancin with the two-dose regimen remained over 1 μg/mL for 14 days, which is higher than the MIC for strains related to ABSSSI [73].

The pharmacokinetics of dalbavancin are best described by a three-compartment model with first-order elimination kinetics [74]. The estimated volume of distribution at steady state is 15.7 L. After 24–48 h of infusion, plasma concentration decreases rapidly as dalbavancin distributes to the tissue, resulting in central and peripheral volumes of 4.03 L and 11.8 L, respectively. Tissue penetration in skin and blister fluid is demonstrated by an AUCskin to AUCplasma ratio of 0.6 within 144 h post-administration. The mean concentration in the blister fluid remains above 30 μg/mL for 7 days after a single 1000 mg dose, exceeding the MIC for most bacteria related to ABSSSI [75, 76].

As a result of its extensive distribution to bone and articular tissues, a two-dose dalbavancin regimen providing tissue exposures above the MIC for S. aureus for 8 weeks is proposed as a promising treatment strategy for bone and articular tissue infections [77]. However, dalbavancin’s concentration in brain tissue and cerebrospinal fluid was low as a result of poor blood–brain barrier penetration, making IV delivery unsuitable for treating meningitis, spinal epidural abscess, or endocarditis with suspected septic emboli. Clinical studies focusing on intraventricular and intrathecal delivery approaches are warranted given dalbavancin’s exceptional antimicrobial activity [71, 78].

Dalbavancin demonstrates good penetration into the lungs, with concentrations in the epithelial lining fluid (ELF) exceeding therapeutic levels needed for S. pneumoniae and S. aureus after a single dose [79, 80].

Dalbavancin is metabolized by hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP-450) isoenzymes and does not inhibit or induce CYP-450 activity [81]. Dalbavancin has two major metabolites, hydroxy-dalbavancin, mannosyl aglycone (the major thermal and acid degradation product) and DB-R6, an additional acid degradation product [82]. Hydroxy-dalbavancin was observed in urine with an excretion level of 12% of the administrated dose in both animal models and patients [50].

Dalbavancin is cleared mostly unchanged in urine and feces, with approximately 33% recovered in urine over 42 days and 20% in feces over 70 days [72, 83]. While body surface area and creatinine clearance influence its clearance, these factors together account for less than 25% of the interindividual variability [82]. In healthy subjects, the total clearance of dalbavancin was 0.047 L/h, including renal clearance, which was 0.015 L/h [72]. These data suggest that non-renal excretion routes play a significant role in total clearance; unlike vancomycin and teicoplanin, which are primarily excreted through the renal route [84, 85].

Therefore, dose adjustment for dalbavancin is not required for patients with any degree of hepatic injury or with mild to moderate kidney dysfunction (CrCl > 30 mL/min). However, for patients with severe renal injury (CrCl < 30 mL/min), the treatment regimen should be reduced to a 750 mg dose on day 1, followed by a 375 mg dose 1 week later to maintain an appropriate plasma concentration (above 20 mg/L).

Monte Carlo simulations using population pharmacokinetic models have been employed in pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) analyses to simulate the probability of target attainment and potential susceptibility breakpoints for dalbavancin [71, 86]. The AUC/MIC was suggested to be the best parameter to evaluate dalbavancin efficacy based on both in vitro and in vivo data [71, 86]. On the basis of the target AUC/MIC over a 14-day period for the two-dose dalbavancin treatment regimen (1000 mg i.v. followed by 500 mg i.v. 1 week later), Dowell et al. reported that there was at least 90% target attainment for MICs of up to 0.5 μg/mL against S. aureus and MICs ≥ 2 μg/mL for β-hemolytic Streptococcus [73]. Another Monte Carlo simulation performed with data from 10,000 subjects showed that the two-dose regimen achieved 100% target attainment for MICs up to 0.25 μg/mL for MRSA in intensive care unit settings [87]. Monte Carlo simulations for the two-dose regimen and a single dose predicted that 99% of the subjects achieved the target for MIC ≤ 2 μg/mL against S. aureus, Streptococcus dysgalactiae, S. pyogenes, and vancomycin-susceptible E. faecalis [74]. This study highlighted the potential efficacy of dalbavancin against isolates with higher MICs than the current 0.25 μg/mL breakpoint. Furthermore, studies using a neutropenic murine thigh infection model demonstrated that a free AUC0−24h/MIC (fAUC0−24h/MIC) ratio > 111.1 was associated with a 2-log reduction in S. aureus burden, offering a robust PD target to support population PK models for off-label indications [88].

Oritavancin

Oritavancin has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of ABSSSI in adults with a single 1200 mg dose via intravenous infusion over 3 h. This regimen is well tolerated and has a similar safety profile and clinical efficacy as a twice-daily vancomycin regimen administered for 7–10 days. According to the FDA drug inset, the AUC0−24h and AUC0−∞for oritavancin are 1110 μg·h/mL and 2800 μg·h/mL, respectively, with a Cmax of 138 μg/mL. These recommendations are based on two phase 3 clinical studies involving 297 patients with ABSSSI who received a single 1200 mg dose [89]. An earlier pharmacokinetic study by Boylan et al. in 2004 compared oritavancin exposure achieved in the interstitial space fluid (by inflammatory blister fluid models) with exposure in plasma and found that oritavancin tended to cluster at sites congested with macrophages [90]. Another skin blister fluid study by Fetterly et al. examined two dosage regimens, 200 mg administered once a day for 3 days and 800 mg once a day for 1 day. After 3 days of treatment, the highest mean concentration of oritavancin was observed at approximately 1 and 10 h in plasma and blister fluid, respectively [91]. At these time points, the mean maximum drug concentration was about eightfold higher in plasma than in the blister fluid. The concentration of oritavancin started to decrease 15 h after the last injection and became undetectable after 100–150 h. The mean maximum plasma concentration was approximately 11-fold greater than that in blister fluid after a single 800 mg dose of oritavancin [92].

Oritavancin has a volume of distribution of 87.6 and 97.8 L for total and mean steady-state distribution, respectively [92]. Similar to dalbavancin, oritavancin has high plasma protein binding at approximately 85%, due to the lipidic moiety in its structure, which enhances plasma protein binding [93].

Oritavancin is primarily cleared through urine and feces with no detectable metabolites, leaving the excreted drug unchanged. A population pharmacokinetic analysis indicates that the elimination process is slow, with a terminal half-life of approximately 245 h and a clearance of 0.445 L/h [94]. About 6% of the drug is eliminated within a week following a single intravenous dose [23].

Although detailed information on the metabolism of oritavancin is limited, oritavancin does not interact with cytochrome P450 enzymes [93]. According to the FDA report and pharmacodynamic studies, a 1200 mg infusion of oritavancin induced the activity of CYP3A4 and CYP2D6, leading to a decrease in midazolam and dextromethorphan concentrations when co-administered [95]. Oritavancin is also a weak inhibitor of CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 as it caused a moderate increase in the plasma concentrations of 5-OH-omeprazole and warfarin when these drugs were co-administered. Despite these interactions, there is no need to adjust dosages for patients with renal or hepatic impairment, and combined treatment with other antibiotics does not show competitive interference. Another therapeutic study determined that the AUC72h/MIC90 ratio threshold was 11,982 when using oritavancin alone for treating S. aureus infections [96]. In this study, 96.2% of the patients achieved clinical success when this threshold was exceeded.

Clinical Efficacy

Dalbavancin

The clinical efficacy of dalbavancin was first demonstrated in a 2005 phase III randomized, double-blind study comparing dalbavancin to linezolid for treating complicated skin and soft structure infections (cSSSIs) [97]. The study evaluated the efficacy of a two-dose dalbavancin regimen (1000 mg on day 1 followed by 500 mg for 1 week) versus linezolid (600 mg i.v. for 14 days). Upon completion of therapy, the clinical success and microbiological response in both arms were > 90% for dalbavancin and > 85% for linezolid. Additionally, the dalbavancin group had a lower proportion of patients (25.4%) with adverse effects compared to the linezolid group (32.2%). In 2010, a meta-analysis of 14 randomized controlled trials involving 8395 patients with cSSSIs reported that dalbavancin displayed higher success rates (87.7%) compared to vancomycin (74.7%), linezolid (84.4%), telavancin (83.5%), daptomycin (78.1%), and tigecycline (70.4%) [98].

DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 were international multicenter phase III studies evaluating dalbavancin for the treatment of ABSSSI. DISCOVER-1 included more patients with major abscesses, while DISCOVER-2 had more patients with cellulitis; both trials had a median infected area exceeding 300 cm2 [27]. The primary endpoints for both trials were clinical responses assessed by cessation of infection spread and high temperatures, 48–72 h after starting therapy. Both trials met their primary endpoints and demonstrated non-inferiority of the two-dose dalbavancin compared to daily administrated comparator agents (vancomycin 1 g or 15 mg/kg, IV q12 h for at least 3 days followed by linezolid 600 mg p.o. q12 h for total 10–14 days) for treating Gram-positive ABSSSI.

The DISCOVER trials also demonstrated that for patients meeting systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria, clinical response rates were nearly equivalent between the dalbavancin (74.7%) and vancomycin/linezolid (78.6%) groups at the cessation of therapy [99]. Although the clinical responses in patients who met SIRS criteria was lower than in those who did not (86.6% in the dalbavancin group versus 81.3% in vancomycin-linezolid group), dalbavancin still showed non-inferiority in seriously ill patients compared to those that received vancomycin-linezolid therapy.

A pooled analysis of primary endpoints from DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 showed that 79.7% of patients receiving dalbavancin had successful outcomes (early clinical response) compared to 79.8% of patients in the vancomycin-linezolid group [100]. Regarding the endpoint of reduction in lesion size by 20% or more, the dalbavancin group had a similar success rate compared to the vancomycin-linezolid group (88.6% and 88.1%, respectively) 48 to 72 h post-treatment initiation. This analysis also revealed that for patients infected with S. aureus (including MRSA) the clinical success rates for dalbavancin and vancomycin-linezolid were 90.6% and 93.8%, respectively. In diabetic patients with cSSSIs, clinical responses and at least 20% reduction of lesion size were achieved by 82.8% and 86.8% of patients receiving dalbavancin at 48–72 h, respectively, versus 76.5% and 83.7% of patients receiving vancomycin-linezolid therapy [29]. The use of dalbavancin in diabetic patients with cSSSIs is particularly important, as patients with diabetes are at a major risk for skin and skin structure infections; this clinical outcome is notable given the global burden of diabetic patients with SSSI [101]. Additionally, an open-labelled, parallel-assignment phase III study (NCT02814916; DUR001-306; 2014-005281-30) conducted in patients ages 3 months to 11 years with ABSSSI assessed the safety and efficacy of dalbavancin versus comparators such as vancomycin, oxacillin, or flucloxacillin [102]. The pharmacokinetic results indicated that an age-dependent regimen matched the adult exposure for both two-dose and single-dose (1500 mg) administration of dalbavancin. In children, dalbavancin was well tolerated, and the safety profile was comparable to that of adults [103]. Additionally, a phase 1 open-label multicenter study in hospitalized pediatric patients aged 3 months to 11 years established an age-adjusted dosing regimen that achieved adult-equivalent systemic exposure, with dalbavancin showing excellent tolerability and no serious adverse events reported [104].

A 2018 prospective open-label randomized study reported that a single 1500 mg dose of dalbavancin had better efficacy than repeated doses of telavancin (daily 10 mg/kg for 6 days, IV) in 200 patients with ABSSSI [105]. More recently, a study comparing outpatients and inpatients with ABSSSI found that both single-dose or two-dose dalbavancin treatments had similar efficacy and safety profiles. However, the outpatient group receiving the single-dose regimen reported higher treatment satisfaction and convenience [106]. Therefore, single-dose dalbavancin is an excellent alternative to the two-dose regimen, especially in the outpatient setting.

Recent real-world data continue to expand dalbavancin’s clinical applications beyond ABSSSI. A multicenter cohort study by Zambrano et al. [107] investigated dalbavancin use in 176 patients with serious Gram-positive infections, including bloodstream infections and endocarditis, comparing outcomes between people who use drugs (PWUD) and non-users. The study found similar clinical cure rates in both groups at 90 days, indicating dalbavancin’s utility even in complex social and clinical settings. Higher rates of early discharge and follow-up challenges were reported in PWUD, highlighting the importance of dalbavancin’s long-acting formulation in improving treatment adherence [107].

A single-center retrospective study from Greece conducted between 2017 and 2022 assessed dalbavancin use across various infections, including osteoarticular (43%), ABSSSI (37%), and cardiovascular infections (10%) [108]. The clinical cure rate was 88%, with no reported mortality, and increased reliance on dalbavancin was observed during the COVID-19 period. These findings reinforce the growing empirical use of dalbavancin in serious Gram-positive infections and support its expanding role in real-world clinical settings [108]. Additionally, the EN-DALBACEN 2.0 cohort study investigated dalbavancin as a consolidation therapy for infective endocarditis caused by Gram-positive cocci. Outcomes were favorable, supporting its consideration as an alternative to extended intravenous regimens in selected stable patients.

Oritavancin

The 2015 SOLO II non-inferiority trial demonstrated that a single dose of oritavancin for ABSSSI caused by Gram-positive organisms was equivalent to 7–10 days of continued twice-daily vancomycin treatment [89]. This equivalency to two single-dose treatments was most likely due to oritavancin concentration-dependent activity and its extended half-life in plasma (245 h) [109]. A retrospective analysis of patient length of stay (LOS) at selected emergency department and observation units [110] found that patients receiving the standard of care took, on average, four times longer to leave the hospital than patients receiving oritavancin treatment [110]. Economically, reducing LOS is largely beneficial for both patients and hospitals [111], especially considering that each ABSSSI-related hospitalization costs US $6000–20,000 for standard treatment [110].

Whittaker et al. found that combining oritavancin with vancomycin significantly reduced the LOS (mean ± SD, 3.5 ± 1.9 days vs. 5.6 ± 2.3 days) compared to control agents [112]. Clinical studies by Helton et al. corroborated these findings, showing similar results (mean ± SD, 19.5 ± 20.7 h vs. 85.98 ± 50.34 h) in the emergency department [113]. A pharmacokinetic analysis of a two-dose oritavancin treatment (1200 mg and 800 mg doses 1 week apart) demonstrated a therapeutic window 11 days longer than a single 1200 mg dose [114]. Additionally, a retrospective chart review of 118 patients with ABSSSI in the USA revealed a comparable clinical efficacy between multidose and single-dose oritavancin therapy [89]. Implementing oritavancin as standard of care in hospitals resulted in significant savings (US $2139 per patient) [115].

Recent real-world evidence has expanded the clinical applications of oritavancin beyond ABSSSI [116]. A retrospective study at a single academic medical center evaluated 75 patients treated with oritavancin for various Gram-positive infections, including ABSSSI, surgical wound infections, and osteomyelitis or septic arthritis. Clinical cure or improvement was achieved in 93.2% of patients, with oritavancin demonstrating a favorable safety profile. Its use facilitated outpatient treatment and reduced hospital stays, underscoring its potential as a convenient option for managing complex infections [116]. Additionally, a review of case studies involving 23 patients treated with oritavancin for osteomyelitis reported an overall clinical success rate of 87% [117]. The majority of patients received multiple doses, and the treatment was well tolerated with minimal adverse events. These findings suggest that oritavancin may offer a viable outpatient therapy for osteomyelitis, although further studies are warranted to establish optimal dosing regimens [117]. Furthermore, a 2022 pharmacokinetic modeling and simulation study proposed pediatric dosing regimens for oritavancin based on body weight and age, supporting future clinical trials and potential use in children with Gram-positive infections [118].

Potential New Indications

Osteomyelitis

A pharmacokinetic model predicted that a two-dose regimen of dalbavancin would achieve clinical success for patients with osteomyelitis by maintaining drug levels in bone above the MIC for 8 weeks. Phase I (DUR001-104 and DUR001-105) studies provided data on bone penetration (DUR001-105) and extended-duration dosing (DUR001-104) in healthy volunteers [77]. A recent phase II study involving 70 patients with osteomyelitis showed clinical improvement in 94% of patients by day 21 and clinical cure in 97% of patients by day 42 [119]. The safety and tolerability of dalbavancin were high, with only 1.42% (1/70 patients) experiencing treatment-related adverse events. However, a phase III study evaluating dalbavancin for osteomyelitis was withdrawn in 2016, indicating the need for further validation through late-stage trials.

In 2018, a multicenter retrospective study identified 36 patients with osteomyelitis treated with dalbavancin. Clinical outcomes were evaluated in 31 patients, with 90% (28/31) achieving clinical success and no adverse events reported [120]. Other real-world studies showed a 76.2% success rate for dalbavancin in treating osteomyelitis [121, 122]. A retrospective study involving 134 patients evaluated the effectiveness of once-weekly oritavancin for acute osteomyelitis [123], informed by earlier case reports of single-dose regimens [124, 125]. The dosage regimen included an initial 1200 mg dose followed by once weekly 800 mg doses for 4–5 weeks, resulting in successful clinical outcomes for 121 patients, with five cases of mild adverse effect.

Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections (CR-BSIs) and Endocarditis

In 2005, a phase II trial was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of dalbavancin for treating CR-BSIs [126]. The microbiology intent-to-treat (microITT) CR-BSIs cohort included patients with infections caused by S. aureus (including MRSA), CoNS, and E. faecalis. In the dalbavancin group, 87% (20/23) of patients achieved primary clinical success, compared to 50% (14/28) in the vancomycin group. Dalbavancin had no serious adverse effects, while the vancomycin group had one case of acute kidney failure. Additionally, microbiologic responses of organism isolates from this trial were studied in vitro, showing dalbavancin’s MICs were ≤ 0.25 μg/mL for all bacterial isolates [127]. Despite the promising results Pfizer discontinued the phase III investigation of dalbavancin for CR-BSIs in 2006.

The in vitro potency of dalbavancin against common isolates from patients with infective endocarditis (IE) was demonstrated with MIC90 of 97.6% isolates below the susceptible breakpoint (0.06 μg/mL) [128]. Retrospective clinical studies also analyzed dalbavancin’s effectiveness for IE. Hidalgo-Tenorio et al. reported a 96.7% clinical cure rate for IE and 100% for BSI in 83 patients [129]. Another retrospective study showed a 92.6% clinical success rate for bacteremia with IE [130]. In 2016, a randomized, multicenter, parallel, and open-label phase II trial (NCT03148756; DAL-MD-092016-004170-17) began to investigate dalbavancin’s effectiveness in treating IE and complicated bacteremia [131], though the study was terminated for business reasons in 2017 with no participant enrolled [132]. The study aimed to enroll 200 adults with complicated S. aureus bacteremia, including definite or possible right-sided infective endocarditis, who have received effective antibiotic therapy for at least 72 h (up to a maximum of 10 days) and shown clearance of bacteremia before randomization. Participants were to be randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either two doses of dalbavancin on days 1 and 8, or a standard intravenous antibiotic regimen lasting 4–8 weeks. The primary goal was to assess the Desirability of Outcome Ranking at day 70, with secondary objectives including quality of life outcomes and pharmacokinetic analyses of dalbavancin [131].

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring and Population PK Modeling

In addition to clinical data, population pharmacokinetic (popPK) modeling and therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) approaches are emerging as valuable strategies to optimize dalbavancin use in long-term or off-label indications such as osteoarticular infections. A 2-year prospective study demonstrated that proactive TDM in routine practice allowed for individualized dose adjustments and monitoring of drug exposure over time, aiding in the sustained management of periprosthetic joint and chronic osteoarticular infections without safety concerns [133]. Another multicenter prospective study confirmed that TDM-supported administration of dalbavancin facilitated effective long-term treatment, with trough levels maintained above efficacy thresholds throughout extended treatment courses [134]. Moreover, a recent popPK model incorporating body mass index (BMI) indicated that increased BMI was associated with delayed decline in plasma concentrations, supporting the feasibility of extending dosing intervals in patients with obesity using TDM-guided strategies [135]. These insights collectively support the integration of TDM and popPK tools to enhance treatment individualization, especially in complex infections.

Safety

Dalbavancin

Dalbavancin was shown to be well tolerated across all clinical trials, with adverse effects reported as mild to moderate. In the DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 trials, patients receiving dalbavancin experienced fewer and less severe side effects compared to those in the vancomycin-linezolid group [29, 136]. In the dalbavancin group, 2.0% of patients discontinued the trial because of adverse effects, similar to the 2.1% in the vancomycin-linezolid group [100]. The most common adverse effects of dalbavancin were nausea (4.7%), headache (3.8%), and diarrhea (3.4%) with a median duration of 3 days [137].

Hepatotoxicity was associated with dalbavancin therapy in 0.8% of patients, specifically with alanine aminotransferase levels elevated up to threefold compared to normal levels; however, this hepatotoxicity was reversible [137]. Unlike vancomycin, which poses a significant risk of nephrotoxicity [138, 139], no renal impairment was observed in patients who received dalbavancin [18]. A phase I trial, including audiological assessment, demonstrated dalbavancin had no ototoxic effects [140]. Dalbavancin did not induce QTc interval prolongation [141] and had no adverse effects on heart rate, PR or QRS intervals [142].

Dalbavancin is contraindicated in patients hypersensitive to glycopeptides because of the risk of cross-hypersensitivity. Rapid infusion of dalbavancin led to the red man syndrome, which can be avoided by extending the infusion time to 30 min [137]. In laboratory settings, dalbavancin did not affect coagulation test results such as prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time [137].

Oritavancin

During the ABSSSI phase 3 SOLO clinical trial, the most commonly reported adverse effects of oritavancin included headache, nausea, vomiting, limb, subcutaneous abscess, diarrhea, and reversible elevation of alanine transaminase [143, 144]. Additionally, oritavancin interferes with coagulation test results by artificially prolonging the prothrombin time and international normalized ratio. Co-administration of oritavancin and warfarin should be avoided as it may increase plasma levels of warfarin and the risk of bleeding [94]. Oritavancin may also cause red man syndrome [145], with infusion-related warnings on its approval label similar to those of dalbavancin.

Future Directions

Dalbavancin and oritavancin are semisynthetic lipoglycopeptide antimicrobial agents effective against complex skin structure infections. They share a spectrum of activity against Staphylococcus spp. (both methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant strains), Streptococcus spp., and vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus spp. A notable pharmacokinetic characteristic of these agents is their prolonged half-life, due to their lipidic moieties, high protein-binding capacity, and intracellular accumulation allowing for infrequent dosing regimens—weekly for dalbavancin and single-dose for oritavancin.

Dalbavancin is excreted unchanged in urine and feces, requiring dose adjustment only in patients with severe renal dysfunction. In contrast, oritavancin requires no dose adjustment, as less than 5% of the unchanged drug is excreted via urine. Despite being available for nearly a decade, clinical uptake has been uneven. Dalbavancin has gained broader acceptance for off-label indications, including osteomyelitis, infective endocarditis, and complicated bloodstream infections, supported by real-world evidence. Conversely, clinical adoption of oritavancin remains limited, and its role in treating biofilm-associated infections and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) remains underexplored.

ClinicalTrials.gov lists only a limited number of prospective studies on the use of oritavancin, with one ongoing study investigating its safety and efficacy in pediatric populations (NCT02134301) [146]. In contrast, a pediatric trial evaluating dalbavancin is actively recruiting (NCT06810583) [147], reflecting growing interest in pediatric applications of lipoglycopeptides. Further randomized controlled trials are needed to validate its broader applications. Dalbavancin has been associated with resistance development in clinical settings, and as a result of structural similarities, vigilance is warranted for oritavancin, despite the lack of clinical resistance data. Most available data originate from phase III trials, highlighting the need for larger real-world studies to assess the safety profiles of both agents and identify rare adverse events.

Dalbavancin combination therapy for off-label uses such as prosthetic joint infections, endocarditis, and BSI also requires further clinical evaluation. In vitro data suggest synergistic effects with other antimicrobials, including activity against MRSA, daptomycin non-susceptible strains, and hVISA phenotypes. However, real-world data remain sparse, limited to isolated reports like its use alongside linezolid in prosthetic joint infection. For patients needing prolonged antibiotic treatment after hospital discharge, both dalbavancin and oritavancin offer promising alternatives to daily intravenous regimens, enabling simplified outpatient management. Recent clinical data from multicenter registries and real-world cohorts further support their safety and efficacy in off-label indications such as osteomyelitis, infective endocarditis, and bacteremia.

Conclusion

Dalbavancin and oritavancin can be considered ‘birds of a feather’ in terms of their antimicrobial spectrum and shared pharmacological class, but ‘apples and oranges’ when it comes to pharmacokinetics, real-world usage, and clinical integration. Both agents merit continued investigation, especially in complex Gram-positive infections where outpatient strategies are increasingly prioritized.

Author Contributions

Maytham Hussein, Tony Velkov, and Jian Li conceived the review topic and designed the manuscript structure. Maytham Hussein conducted the literature review and drafted the initial manuscript. James Barclay, Mark Baker, Yuezhou Wu, Varsha J. Thombare, Nitin Patil, Ananya B. Murthy, Rajnikant Sharma, Gauri G. Rao, and Mark A. T. Blaskovich contributed to critical revision and content refinement. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Gauri G. Rao, Tony Velkov, and Jian Li are supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, award numbers R01AI146241, R01AI170889. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. No funding or sponsorship was received for the development and publication of this article.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Jian Li is an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Principal Research Fellow, and Tony Velkov is an Australian Research Council Mid-Career Industry Fellow. All other authors (Maytham Hussein, James Barclay, Mark Baker, Yuezhou Wu, Varsha J. Thombare, Nitin Patil, Ananya B. Murthy, Rajnikant Sharma, Gauri G. Rao, and Mark A. T. Blaskovich) declare no conflicting interests.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Turner NA, Sharma-Kuinkel BK, Maskarinec SA, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an overview of basic and clinical research. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(4):203–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peacock SJ, Paterson GK. Mechanisms of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Annu Rev Biochem. 2015;84:577–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. The biggest antibiotic-resistant threats in the U.S: US. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/biggest_threats.html. Accessed 16 Apr 2025.

- 4.World Health Organization. Global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system (GLASS) report 2024. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240093461. Accessed 16 Apr 2025.

- 5.Levine DP. Vancomycin: understanding its past and preserving its future. South Med J. 2008;101(3):284–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Healy VL, Lessard IAD, Roper DI, Knox JR, Walsh CT. Vancomycin resistance in enterococci: reprogramming of the d-Ala–d-Ala ligases in bacterial peptidoglycan biosynthesis. Chem Biol. 2000;7(5):R109–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis PO, Heil EL, Covert KL, Cluck DB. Treatment strategies for persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2018;43(5):614–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nolin TD. Vancomycin and the risk of AKI: now clearer than Mississippi mud. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(12):2101–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park JH, Reviello RE, Loll PJ. Crystal structure of vancomycin bound to the resistance determinant D-alanine-D-serine. IUCrJ. 2024;11(Pt 2):133–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reipert A, Ehlert K, Kast T, Bierbaum G. Morphological and genetic differences in two isogenic Staphylococcus aureus strains with decreased susceptibilities to vancomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(2):568–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koh AJJ, Thombare V, Hussein M, Rao GG, Li J, Velkov T. Bifunctional antibiotic hybrids: a review of clinical candidates. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1158152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Bambeke F. Lipoglycopeptide antibacterial agents in Gram-positive infections: a comparative review. Drugs. 2015;75(18):2073–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorrie C, Higgs C, Carter G, Stinear TP, Howden B. Genomics of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. Microb Genom. 2019. 10.1099/mgen.0.000283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golan Y. Current treatment options for acute skin and skin-structure infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(Supplement_3):S206–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Díaz-Navarro M, Hafian R, Manzano I, et al. A dalbavancin lock solution can reduce enterococcal biofilms after freezing. Infect Dis Ther. 2022. 10.1007/s40121-021-00579-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lupia T, De Benedetto I, Bosio R, Shbaklo N, De Rosa FG, Corcione S. Role of oritavancin in the treatment of infective endocarditis, catheter- or device-related infections, bloodstream infections, and bone and prosthetic joint infections in humans: narrative review and possible developments. Life. 2023;13(4):959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esposito S, Pagliano P, De Simone G, et al. In-label, off-label prescription, efficacy and tolerability of dalbavancin: report from a national registry. Infection. 2024;52(4):1297–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith JR, Roberts KD, Rybak MJ. Dalbavancin: a novel lipoglycopeptide antibiotic with extended activity against Gram-positive infections. Infect Dis Ther. 2015;4(3):245–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.FDA. Dalbavancin (FDA Label). 2021. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/021883s010lbl.pdf. Accessed 16 Apr 2025.

- 20.FDA. Oritavancin (FDA Label). 2012. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/206334s006lbl.pdf. Accessed 16 Apr 2025.

- 21.Byrne CJ, Parton T, McWhinney B, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of total and unbound teicoplanin concentrations and dosing simulations in patients with haematological malignancy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;73(4):995–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cercenado E. Espectro antimicrobiano de dalbavancina. Mecanismo de acción y actividad in vitro frente a microorganismos Gram positivos. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35:9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhavnani SM, Owen JS, Loutit JS, Porter SB, Ambrose PG. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of ascending single intravenous doses of oritavancin administered to healthy human subjects. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;50(2):95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duong M, Markwell S, Peter J, Barenkamp S. Randomized, controlled trial of antibiotics in the management of community-acquired skin abscesses in the pediatric patient. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55(5):401–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butler MS, Hansford KA, Blaskovich MA, Halai R, Cooper MA. Glycopeptide antibiotics: back to the future. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 2014;67(9):631–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen AY, Zervos MJ, Vazquez JA. Dalbavancin: a novel antimicrobial. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(5):853–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramdeen S, Boucher HW. Dalbavancin for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16(13):2073–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seltzer E, Dorr MB, Goldstein BP, et al. Once-weekly dalbavancin versus standard-of-care antimicrobial regimens for treatment of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(10):1298–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boucher HW, Wilcox M, Talbot GH, Puttagunta S, Das AF, Dunne MW. Once-weekly dalbavancin versus daily conventional therapy for skin infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2169–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barrett JF. Oritavancin. Eli Lilly & Co. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2001;2(8):1039–44. [PubMed]

- 31.Cabellos C, Fernàndez A, Maiques JM, et al. Experimental study of LY333328 (oritavancin), alone and in combination, in therapy of cephalosporin-resistant pneumococcal meningitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(6):1907–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharman GJ, Try AC, Dancer RJ, et al. The roles of dimerization and membrane anchoring in activity of glycopeptide antibiotics against vancomycin-resistant bacteria. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119(50):12041–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arena CT. Oritavancin – glycopeptide antibiotic. Oritavancin is an investigational glycopeptide antibiotic being developed by Targanta Therapeutics for the treatment of: Clinical Trials Arena; 2008. https://www.clinicaltrialsarena.com/marketdata/oritavancin/. Accessed 16 Apr 2025.

- 34.NEJM Journal Watch. FDA approves oritavancin for skin infections. 2014. https://www.jwatch.org/na35529/2014/08/26/fda-approves-oritavancin-skin-infections. Accessed 16 Apr 2025.

- 35.Juul JJ, Mullins CF, Peppard WJ, Huang AM. New developments in the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections: considerations for the effective use of dalbavancin. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016;12:225–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim A, Kuti JL, Nicolau DP. Review of dalbavancin, a novel semisynthetic lipoglycopeptide. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2007;16(5):717–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blaskovich MAT, Hansford KA, Butler MS, Jia Z, Mark AE, Cooper MA. Developments in glycopeptide antibiotics. ACS Infect Dis. 2018;4(5):715–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malabarba A, Goldstein BP. Origin, structure, and activity in vitro and in vivo of dalbavancin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55(Suppl 2):ii15-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bailey J, Summers KM. Dalbavancin: a new lipoglycopeptide antibiotic. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2008;65(7):599–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng M, Ziora ZM, Hansford KA, Blaskovich MA, Butler MS, Cooper MA. Anti-cooperative ligand binding and dimerisation in the glycopeptide antibiotic dalbavancin. Org Biomol Chem. 2014;12(16):2568–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steele JM, Seabury RW, Hale CM, Mogle BT. Unsuccessful treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis with dalbavancin. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2018;43(1):101–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Biondi S, Chugunova E, Panunzio M. Chapter 8 - From natural products to drugs: glyco- and lipoglycopeptides, a new generation of potent cell wall biosynthesis inhibitors. In: Rahman A ur, editor. Studies in natural products chemistry, vol. 50. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2016. p. 249–97.

- 43.Allen NE, Nicas TI. Mechanism of action of oritavancin and related glycopeptide antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;26(5):511–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKay GA, Beaulieu S, Arhin FF, et al. Time-kill kinetics of oritavancin and comparator agents against Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63(6):1191–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barrett J. Oritavancin. Eli Lilly & Co. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2001;2(8):1039–44. [PubMed]

- 46.Belley A, McKay GA, Arhin FF, et al. Oritavancin disrupts membrane integrity of Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococci to effect rapid bacterial killing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(12):5369–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.FDA. Dalbavancin label, highlights of prescribing information: Food and Drug Administration. 2018. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/021883s007lbl.pdf. Accessed 16 Apr 2025.

- 48.Koeth LM, DiFranco-Fisher JM, McCurdy S. A reference broth microdilution method for dalbavancin in vitro susceptibility testing of bacteria that grow aerobically. J Vis Exp. 2015;(103):53028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Rennie RP, Koeth L, Jones RN, et al. Factors influencing broth microdilution antimicrobial susceptibility test results for dalbavancin, a new glycopeptide agent. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(10):3151–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Research CfDEa. Division of Anti-infective Products. Dalbavancin, Durata Therapeutics. 2014. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2014/021883Orig1s000MicroR.pdf. Accessed 16 Apr 2025.

- 51.Zhanel GG, Calic D, Schweizer F, et al. New lipoglycopeptides: a comparative review of dalbavancin, oritavancin and telavancin. Drugs. 2010;70(7):859–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lopez S, Hackbarth C, Romano G, Trias J, Jabes D, Goldstein BP. In vitro antistaphylococcal activity of dalbavancin, a novel glycopeptide. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55(Suppl 2):ii21–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Campanile F, Borbone S, Perez M, et al. Heteroresistance to glycopeptides in Italian meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;36(5):415–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roper DI, Huyton T, Vagin A, Dodson G. The molecular basis of vancomycin resistance in clinically relevant Enterococci: crystal structure of D-alanyl-D-lactate ligase (VanA). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(16):8921–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhanel GG, Trapp S, Gin AS, et al. Dalbavancin and telavancin: novel lipoglycopeptides for the treatment of gram-positive infections. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2008;6(1):67–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Al Janabi J, Tevell S, Sieber RN, Stegger M, Söderquist B. Emerging resistance in Staphylococcus epidermidis during dalbavancin exposure: a case report and in vitro analysis of isolates from prosthetic joint infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2023;78(3):669–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Werth BJ, Jain R, Hahn A, et al. Emergence of dalbavancin non-susceptible, vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) after treatment of MRSA central line-associated bloodstream infection with a dalbavancin- and vancomycin-containing regimen. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(4):429.e1–e5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Žiemytė M, Rodríguez-Díaz JC, Ventero MP, Mira A, Ferrer MD. Effect of dalbavancin on staphylococcal biofilms when administered alone or in combination with biofilm-detaching compounds. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Yan Q, Karau MJ, Raval YS, Patel R. In vitro activity of oritavancin in combination with rifampin or gentamicin against prosthetic joint infection-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;52(5):608–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mendes RE, Sader HS, Castanheira M, Flamm RK. Distribution of main gram-positive pathogens causing bloodstream infections in United States and European hospitals during the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program (2010–2016): concomitant analysis of oritavancin in vitro activity. J Chemother. 2018;30(5):280–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arhin FF, Draghi DC, Pillar CM, Parr TR Jr, Moeck G, Sahm DF. Comparative in vitro activity profile of oritavancin against recent gram-positive clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(11):4762–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arhin FF, Sarmiento I, Belley A, et al. Effect of polysorbate 80 on oritavancin binding to plastic surfaces: implications for susceptibility testing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(5):1597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kavanagh A, Ramu S, Gong Y, Cooper MA, Blaskovich MAT. Effects of microplate type and broth additives on microdilution MIC susceptibility assays. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63(1): 10.1128/aac.01760-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Biedenbach DJ, Arhin FF, Moeck G, Lynch TF, Sahm DF. In vitro activity of oritavancin and comparator agents against staphylococci, streptococci and enterococci from clinical infections in Europe and North America, 2011–2014. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;46(6):674–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Belley A, Lalonde Seguin D, Arhin F, Moeck G. Comparative in vitro activities of oritavancin, dalbavancin, and vancomycin against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates in a nondividing state. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(7):4342–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bozdogan B, Ednie L, Credito K, Kosowska K, Appelbaum PC. Derivatives of a vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain isolated at Hershey Medical Center. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(12):4762–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arthur M, Depardieu F, Reynolds P, Courvalin P. Moderate-level resistance to glycopeptide LY333328 mediated by genes of the vanA and vanB clusters in enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43(8):1875–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Miller WR, Murray BE, Rice LB, Arias CA. Resistance in vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2020;34(4):751–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yan Q, Karau MJ, Patel R. In vitro activity of oritavancin against biofilms of staphylococci isolated from prosthetic joint infection. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;92(2):155–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bowker KE, Noel AR, MacGowan AP. Pharmacodynamics of dalbavancin studied in an in vitro pharmacokinetic system. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58(4):802–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Galluzzo M, D’Adamio S, Bianchi L, Talamonti M. Pharmacokinetic drug evaluation of dalbavancin for the treatment of skin infections. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2018;14(2):197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leighton A, Gottlieb AB, Dorr MB, et al. Tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and serum bactericidal activity of intravenous dalbavancin in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(3):940–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dowell JA, Goldstein BP, Buckwalter M, Stogniew M, Damle B. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of dalbavancin, a novel glycopeptide antibiotic. J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;48(9):1063–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Carrothers TJ, Chittenden JT, Critchley I. Dalbavancin population pharmacokinetic modeling and target attainment analysis. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2019. 10.1002/cpdd.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Garnock-Jones KP. Single-dose dalbavancin: a review in acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections. Drugs. 2017;77(1):75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]