Abstract

This study investigated the effects of 17β-estradiol (E2) on male goldfish, with particular focus on how social interactions modify physiological responses. Four experimental groups were housed in 80 L tanks and received two injections at 14-day intervals over 28 days: MF (5 males + 5 females, sesame oil), M (10 males, sesame oil), MEF (5 males + 5 females, E2), and ME (10 males, E2). The MF group exhibited the highest growth performance, with significantly greater final weight (36.3 ± 1.1 g), weight gain (11.3 ± 1.4 g), and specific growth rate (1.8 ± 0.2% day⁻1) (P < 0.05). E2 exposure disrupted biochemical parameters, elevating cholesterol and triglycerides while reducing glucose and phosphorus (P < 0.05). Testosterone levels were significantly lower in E2-treated groups, with MF maintaining the highest levels (P < 0.05). Sperm activity and motility were severely impaired in E2-treated groups, with MF showing the highest sperm activity (95.6%) and motility time (371.2 sec) (P < 0.05). Gonadosomatic index was highest in MF (5.99%) but significantly reduced in MEF (4.56%), indicating gonadal impairment (P < 0.05). E2 exposure and social isolation inhibited spermatogenesis, reducing spermatogonia and spermatocytes. Liver histopathology revealed severe damage in ME, while MF displayed optimal hepatic structure. These results highlight the negative impact of E2 exposure on growth, reproduction, and liver function, while social interactions mitigated some effects. This underscores the complex interplay between endocrine disruption, social dynamics, and physiological health in goldfish.

Keywords: 17β-estradiol, Goldfish, Biochemical parameters, Sperm characteristics, Gonadal development, Endocrine disruption

Subject terms: Physiology, Zoology

Introduction

Estrogens exert pleiotropic effects in vertebrates, regulating diverse physiological processes including growth, metabolic homeostasis, neural function, and tissue development across multiple organ systems1–5. The three primary endogenous estrogens, estrone (E1), 17β-estradiol (E2), and estriol (E3), serve as key endocrine signaling molecules that coordinate systemic physiology through both genomic and non-genomic mechanisms3,6,7. While classically associated with gonadal function, these steroid hormones demonstrate broad tissue distribution and influence numerous non-reproductive pathways, including hepatic metabolism, cardiovascular regulation, and bone maintenance3,6,7. E2, a hormone in vertebrates, plays a key role in the reproductive system4,5,8–11. Spermatogenesis is a crucial process in the male reproductive system3,12,13, and previous studies have demonstrated significant associations between sex steroids and factors such as spermatogenesis, sperm survival, and DNA fragmentation14–16. Although estrogen is typically regarded as a female hormone, its synthesis in males has often been overlooked due to the focus on testosterone (T), the androgen primarily responsible for male reproductive structure and function. While estrogens are classically known for their central role in female reproduction, there is now compelling evidence that they also play a key role in regulating male reproductive function3,7,17,18.

The reproductive physiology and behavior of male fish are regulated by sex steroids, particularly E2, which plays a critical role in spermatogenesis, steroidogenesis, and reproductive behaviors. While estrogens are primarily associated with female reproductive function, their presence in males is essential for maintaining hormonal balance and modulating reproductive processes. Previous studies have shown that exogenous E2 administration affects testicular development, plasma steroid levels, and reproductive behaviors in teleost fish3,19,20. In species such as common carp (Cyprinus carpio), zebrafish (Danio rerio), and neotropical fish (Astyanax rivularis), E2 treatment has been reported to induce vitellogenin (Vtg) synthesis, alter testicular morphology, and suppress androgen production21–23. Even though the effects of environmental endocrine disruptors have been widely studied, relatively little is known about how direct E2 administration influences male reproductive physiology, particularly in the presence or absence of social interactions. Male reproductive function is known to be socially responsive, as the presence of females can influence hormone secretion, gametogenesis, and reproductive behaviors24,25. However, few studies have examined how hormonal and social factors interact to regulate male reproductive function. To address this gap, the present study investigates the effects of E2 injection on reproductive and endocrine responses in male goldfish (Carassius auratus), with a particular focus on the interaction between hormonal treatment and social environment. Goldfish is an established model for studying reproductive physiology, fertility, growth, and hepatotoxicity due to well-characterized endocrine system, sensitivity to hormonal and environmental disruptions, and ease of experimental manipulation26–29.

This study provides the first systematic investigation of direct E2 administration on male reproductive physiology while simultaneously evaluating social interaction as a potential modulator. Our experimental design uniquely dissects the interplay between endocrine disruption and social ecology by comparing E2 effects in socially isolated males versus those maintained with female conspecifics-an approach previously unexplored in teleost reproductive studies. This work advances beyond conventional estrogen research by concurrently assessing multiple physiological endpoints (reproductive, endocrine, hepatic, and growth parameters) under controlled social conditions, establishing novel cause-and-effect relationships. The study establishes goldfish as a model for social-endocrine interactions, providing mechanistic insights into how natural social structures may buffer or exacerbate hormonal disruptions.

By comparing male goldfish injected with E2 under different social conditions (paired with females vs. isolated males), this study aims to evaluate the combined effects of exogenous estrogen administration and social interactions on sperm quality, testicular function, steroid hormone levels, and hepatic histology. Additionally, we assess growth performance, physiological responses, and gonadal development, as well as the potential hepatotoxic effects of E2. These findings will contribute to a deeper understanding of how estrogens regulate male reproductive physiology, expanding beyond previous research that primarily examined environmental estrogen exposure.

Results

Growth performance in male

The MF group had the highest final weight, significantly exceeding the other groups (P < 0.05, Table 1). WG and SGR were highest in the MF group, significantly exceeding the other groups (P < 0.05, Table 1). CF showed minor variations, with the MF group having the highest and the MEF group having the lowest values (P < 0.05). FCR was significantly greater in the MF group, which also exhibited the most efficient FCR, while the MEF group had the least efficient FCR (P < 0.05, Table 1).

Table 1.

Growth parameters of male goldfish (Carassius auratus) following a 28-day experimental period (n = 3).

| Parameters | MF | M | MEF | ME |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial weight (g) | 25.0 ± 0.0 | 25.0 ± 0.3 | 23.3 ± 0.5 | 24.6 ± 0.2 |

| Initial length (cm) | 12.7 ± 0.2 | 12.6 ± 0.2 | 12.3 ± 0.1 | 12.6 ± 0.2 |

| Final weight (g) | 36.3 ± 1.1a | 29.0 ± 0.4b | 26.2 ± 0.8b | 29.3 ± 0.7b |

| Final length (cm) | 13.0 ± 0.3 | 13.2 ± 0.2 | 12.7 ± 0.2 | 12.8 ± 0.6 |

| WG (g) | 11.3 ± 1.4a | 4.0 ± 0.2b | 2.8 ± 0.3b | 4.6 ± 0.8b |

| SGR (% day−1) | 1.8 ± 0.2a | 0.7 ± 0.0b | 0.5 ± 0.1b | 0.8 ± 0.1b |

| CF | 1.6 ± 0.0a | 1.3 ± 0.1bc | 1.1 ± 0.1c | 1.5 ± 0.1ab |

| FI fish−1 (g) | 23.7 ± 0.9a | 17.0 ± 0.6b | 13.7 ± 0.9b | 18.0 ± 1.7b |

| FCR | 2.1 ± 0.2b | 4.3 ± 0.3ab | 5.0 ± 0.8a | 4.1 ± 0.8ab |

| SR (%) | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 93.3 ± 3.3 | 80.0 ± 20.0 | 93.3 ± 3.3 |

MF group (5 males and 5 females receiving sesame oil injections), M group (10 males receiving sesame oil injections), MEF group (5 males treated with E2 + sesame oil, and paired with 5 females), and ME group (10 males treated with E2 + sesame oil). Values are presented as mean ± standard error, with superscript letters indicating significant differences among groups (P < 0.05). WG, weight gain, SGR, specific growth rate, CF, condition factor, SR, survival rate, FI, feed intake per fish, and FCR, feed conversion ratio.

Biochemical parameters in male

The results showed that glucose levels were highest in the MF group and lowest in the ME group, with a significant decrease in the latter (P < 0.05; Table 2). Cholesterol levels increased with E2 exposure, with the lowest in MF and the highest in ME, showing significant differences between groups (P < 0.05). Triglyceride levels were lowest in MF and M groups and highest in MEF and ME groups, with significant differences (P < 0.05). Total protein concentrations were highest in the MEF and ME groups, while albumin levels showed no significant differences across groups (P > 0.05). Phosphorus levels decreased with E2 treatment, with the lowest in ME and the highest in MF, showing significant differences (P < 0.05). Calcium levels were lowest in MF and M groups, with the highest in MEF and ME groups, with significant differences observed (P < 0.05), as presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Plasma biochemical parameters of male goldfish (Carassius auratus) following a 28-day experimental period (n = 10 per tretament).

| Parameters | MF | M | MEF | ME |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose (mg dL−1) | 71.9 ± 5.4a | 59.6 ± 9.7ab | 61.0 ± 5.4ab | 43.5 ± 4.8b |

| Cholesterol (mg dL−1) | 213.9 ± 27.2b | 239.0 ± 18.1ab | 257.9 ± 14.9ab | 296.7 ± 6.8a |

| Triglyceride (mg dL−1) | 181.6 ± 22.6b | 179.0 ± 5.8b | 231.4 ± 7.5a | 224.5 ± 2.7a |

| Total protein (g dL−1) | 4.2 ± 0.1b | 4.1 ± 0.2b | 5.4 ± 0.1a | 5.4 ± 0.3a |

| Albumin (g dL−1) | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 0.8 | 3.3 ± 0.5 |

| Phosphorus (mg dL−1) | 3.7 ± 0.1a | 3.5 ± 0.1ab | 2.9 ± 0.4ab | 2.8 ± 0.4b |

| Calcium (mg dL−1) | 7.6 ± 0.7b | 8.1 ± 0.2b | 9.1 ± 0.5ab | 9.4 ± 0.4a |

MF group (5 males and 5 females receiving sesame oil injections), M group (10 males receiving sesame oil injections), MEF group (5 males treated with E2 + sesame oil, and paired with 5 females), and ME group (10 males treated with E2 + sesame oil). Values are presented as mean ± standard error, with superscript letters indicating significant differences among groups (P < 0.05).

Hormonal parameters in male

The MF group exhibited the highest T concentration, significantly exceeding the MEF and ME groups (Table 3; P < 0.05). The M group displayed moderate T levels, which were not significantly different from the MF group but were significantly higher than the MEF and ME groups (P < 0.05). Both the MEF and ME groups showed the lowest T concentrations, with the ME group having the lowest overall levels. This highlights a clear decline in T levels in E2-treated groups (MEF and ME), while the MF group maintained the highest levels due to the absence of hormonal treatment and isolation effects. These findings suggest that E2 exposure, particularly in the male-alone condition (ME group), leads to a significant reduction in T levels compared to both the control group and the paired treatment groups. Regarding E2, the ME group showed significantly elevated levels compared to the other groups (MF, M, and MEF), all of which had similar concentrations (Table 3; P < 0.05). This confirms that the experimental E2 injections effectively increased plasma E2 levels in the ME group. For T3, the highest levels were observed in the MF group, which significantly differed (Table 3; P < 0.05) from the MEF and ME groups. The M group displayed intermediate T3 levels, which were not significantly different from MF or MEF groups, suggesting a partial influence of the male-alone condition. The MEF and ME groups exhibited similarly low T3 concentrations, with no significant difference between them, indicating that E2 injections had a suppressive effect on T3 levels. T4 concentrations were significantly higher (Table 3; P < 0.05) in the MF, M, and ME groups compared to the MEF group. Notably, the MF group had the highest T4 concentration, while the MEF group displayed markedly reduced levels. Interestingly, the ME group exhibited T4 levels comparable to the MF and M groups, suggesting that E2 administration does not consistently lower T4 when males are isolated.

Table 3.

Plasma hormonal parameters of male goldfish (Carassius auratus) following a 28-day experimental period (n = 10 per treatment).

| Parameters | MF | M | MEF | ME |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17β-estradiol (ng mL−1) | 41.4 ± 4.3b | 42.8 ± 2.7b | 35.1 ± 3.6b | 56.5 ± 5.9a |

| Testosterone (ng mL−1) | 58.5 ± 4.0a | 50.3 ± 3.9ab | 49.4 ± 1.3ab | 47.2 ± 1.5b |

| Triiodothyronine (ng mL−1) | 25.1 ± 1.9a | 18.0 ± 3.6ab | 10.9 ± 2.4b | 10.9 ± 2.8b |

| Thyroxine (ng mL−1) | 7.7 ± 0.4a | 5.2 ± 0.8a | 1.3 ± 0.6b | 5.6 ± 0.7a |

MF group (5 males and 5 females receiving sesame oil injections), M group (10 males receiving sesame oil injections), MEF group (5 males treated with E2 + sesame oil, and paired with 5 females), and ME group (10 males treated with E2 + sesame oil). Values are presented as mean ± standard error, with superscript letters indicating significant differences among groups (P < 0.05).

Sperm characteristics

As shown in Fig. 1A, sperm activity varied significantly among groups (P < 0.05), with the MF group exhibiting the highest activity, significantly greater than the M, MEF, and ME groups, which showed comparable reductions (P > 0.05). Figure 1B similarly revealed significant differences in motility duration (P < 0.05), where the MF group-maintained sperm movement longest, followed by the M group, while E2-treated groups showed the most severe declines.

Fig. 1.

Sperm characteristics of male goldfish (Carassius auratus) following a 28-day experimental period. The figure illustrates changes in (A) sperm activity (%) and (B) motility time (sec) across the four experimental groups. MF group (5 males and 5 females receiving sesame oil injections), M group (10 males receiving sesame oil injections), MEF group (5 males treated with E2 + sesame oil, and paired with 5 females), and ME group (10 males treated with E2 + sesame oil). Data are presented as mean ± standard error, with significant differences among groups indicated by different letters (P < 0.05; n = 10 per treatment).

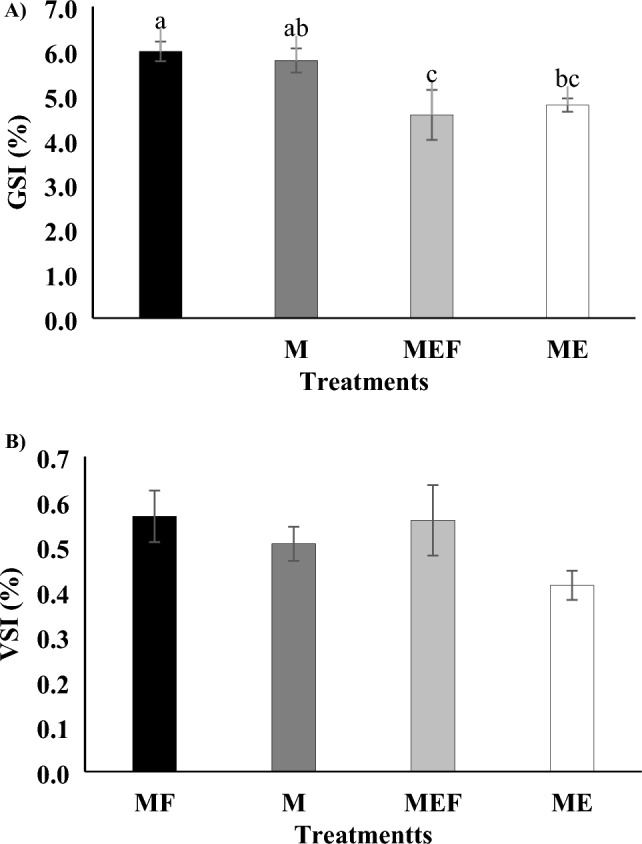

GSI and VSI in male

The MF group showed the highest GSI, significantly greater than the MEF group (Fig. 2 A; P < 0.05). The M and ME groups had intermediate values, with ME being significantly lower than MF. The MEF group had the lowest GSI, indicating E2’s strong inhibitory effect on gonadal development when males were paired with females. Isolation (M, ME groups) resulted in milder but still significant GSI reductions. No significant differences were observed in the VSI across the groups (Fig. 2B; P > 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Gonadosomatic index (GSI), and viscero-somatic index (VSI) of male goldfish (Carassius auratus) following a 28-day experimental period. The figure illustrates changes in (A) gonadosomatic index (%) and (B) viscero-somatic index (%) across the four experimental groups. MF group (5 males and 5 females receiving sesame oil injections), M group (10 males receiving sesame oil injections), MEF group (5 males treated with E2 + sesame oil, and paired with 5 females), and ME group (10 males treated with E2 + sesame oil). Data are presented as mean ± standard error, with significant differences among groups indicated by different letters (P < 0.05) (n = 10 per treatment).

Gonadal development in male

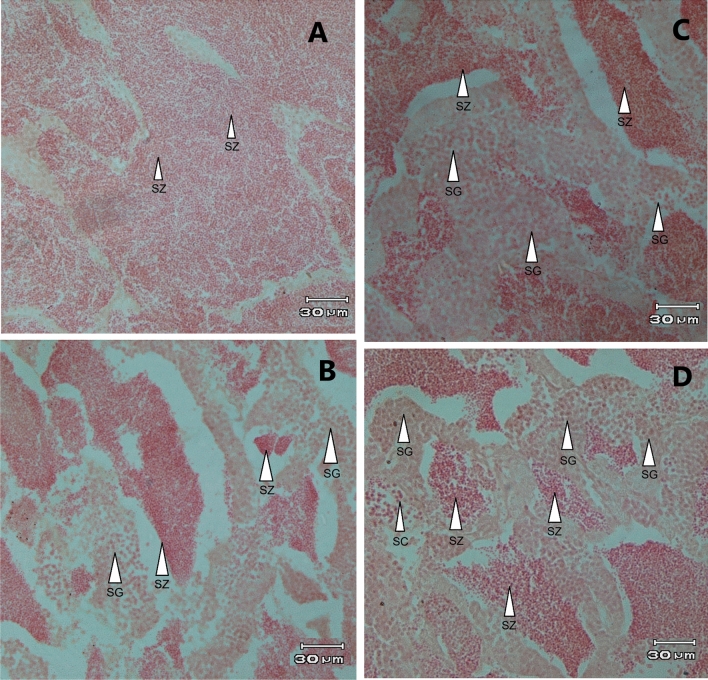

The histological analysis of goldfish testes revealed distinct differences in testicular development across the experimental groups (Fig. 3A–D). In the ME group, the testes showed relatively poor development, with SG being the predominant cell type. SCs were also observed, but SZs were largely absent, indicating that E2 treatment in isolation inhibited spermatogenesis. In the MEF group, testicular development was slightly better than in the ME group, but it was still not as advanced as in the MF group. While SG and SC were more prominent in this group, SZs were still limited, suggesting that pairing with females did not fully counteract the negative effects of E2 on testicular development. The M group showed more advanced testicular development compared to both the ME and MEF groups. In this group, the testes displayed a higher proportion of SZ, alongside SG, indicating active spermatogenesis. However, the testes in the M group were still less developed than those in the MF group, suggesting that the absence of E2 treatment had a positive effect on spermatogenesis, but male-female interactions still played a crucial role in promoting optimal testicular development. In contrast, the MF group exhibited the most developed testes, with SZ being the dominant cell type, indicating active spermatogenesis.

Fig. 3.

Testicular histological characteristics of male goldfish (Carassius auratus) following a 28-day experimental period. The figure illustrates the testicular changes observed in the four experimental groups: MF group (5 males and 5 females receiving sesame oil injections; A), M group (10 males receiving sesame oil injections; B), MEF group (5 males treated with E2 + sesame oil, and paired with 5 females; C), and ME group (10 males treated with E2 + sesame oil; D). Testicular sections were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H & E), showing key features such as SG (spermatogonia cells), SC (spermatocyte cells), and SZ (spermatozoa cell). Scale bar: 30 µm at 40 × magnification.

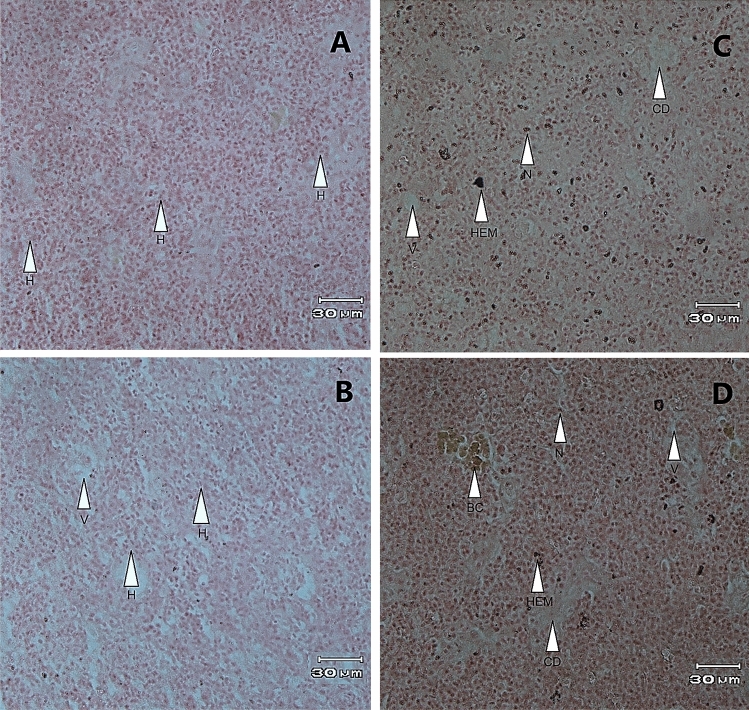

Liver histological analysis in male

The histological analysis of goldfish liver revealed distinct differences in liver health condition across the experimental groups (Fig. 4A–D). The histological analysis of liver tissue indicated that the M group exhibited liver tissue that was like the MF group. Both groups showed predominantly intact hepatic cells, with no significant evidence of necrosis or cell death. However, the M group displayed slight vacuolization (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the MF group showed the healthiest liver tissue, with minimal structural abnormalities and no signs of hemorrhage or blood congestion, suggesting that male interaction with females in an untreated state maintain optimal liver health (Fig. 4A). The MEF and ME groups showed moderate hepatic stress. Additionally, there were moderate occurrences of necrosis and cell death, along with mild blood congestion and rare hemorrhage (Fig. 4C, D). These findings suggest that while E2 treatment induces hepatic stress, the presence of females as social partners may have a mitigating effect, reducing the severity of liver damage compared to isolated males treated with E2. In contrast, the ME group displayed the most severe liver damage (Fig. 4D). Extensive necrosis and cell death were observed, alongside pronounced vacuolization, blood congestion, and frequent hemorrhage.

Fig. 4.

Liver histological characteristics of male goldfish (Carassius auratus) following a 28-day experimental period.. The figure illustrates the hepatic changes observed in the four experimental groups: MF group (5 males and 5 females receiving sesame oil injections; A), M group (10 males receiving sesame oil injections; B), MEF group (5 males treated with E2 + sesame oil, and paired with 5 females; C), and ME group (10 males treated with E2 + sesame oil; D). Liver sections were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H & E), showing key features such as H (hepatic cells), V (vacuolization), N (necrosis), CD (cell death), BC (blood congestion), and HEM (hemorrhage). Scale bar: 30 µm at 40 × magnification.

Discussion

Growth performance

Social interaction without E2 exposure promotes optimal growth in male goldfish, as shown by significantly higher weight gain and growth rates in the MF group. This supports previous findings that E2 suppresses growth by downregulating IGF-1 and IGF-2 within the growth hormone/Insulin-like growth factor axis (GH/IGF axis)39,40. Notably, while final lengths remained unchanged, weight-based metrics proved to be more sensitive to endocrine disruption a pattern consistent with other teleosts41. The MEF group’s pronounced reduction in WG and SGR suggests a compounded negative effect from the combined influences of E2 exposure and lack of social cues42. Beyond confirming these known effects, our results offer novel insights: the MF group’s superior CF and FCR imply that social cues may enhance neuroendocrine regulation of appetite and digestion. We hypothesize that dopaminergic signaling, known to modulate social behavior in fish, may also play a role in these growth effects potentially marking an unexplored pathway for future investigation43–45. Additionally, the MF group’s efficient feed consumption may indicate positive social buffering reducing stress via hypothalamic–pituitary–interrenal (HPI-axis) modulation and cortisol suppression, as observed in other cyprinids46. Conversely, high FCR and low feed intake in MEF suggest that E2-induced suppression of appetite might occur through thyroid pathway disruptions47–49. High feed intake in the MF group suggests social stimuli enhance appetite and metabolism, while low FC in MEF indicates E2 suppresses feeding, potentially via thyroid hormone pathway disruptions47–49. Finally, we note that the heightened stress of social isolation combined with hormonal imbalance could prime the HPI axis for more severe endocrine disruption a hypothesis that merits molecular exploration in future work. To build on this, assessing stress markers like cortisol and exploring temporal dynamics in the GH/IGF, thyroid, and dopaminergic signaling pathways would significantly advance the mechanistic understanding of E2’s multifaceted impact.

Biochemical parameters

Our study demonstrated that E2 exposure significantly reduced glucose levels in the ME group, consistent with findings in snakeskin gourami (Trichopodus pectoralis), where E2-treated fish showed elevated plasma glucose due to increased energetic demands during vitellogenesis50. The unexpected glucose reduction in isolated male goldfish, however, suggests a sex-specific metabolic reprogramming: in males, E2 likely diverts glucose toward lipogenesis, resulting in a paradoxical hypoglycemia consistent with “metabolic feminization” of male fish under estrogen exposure51,52. The increase in cholesterol and triglyceride levels across E2-treated groups supports previous evidence that estrogens drive lipid synthesis and deposition30,53,54. This effect mirrors observations in E2-exposed juvenile stellate sturgeon (Acipenser stellatus) and Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus)30,50, and is complemented by hepatic excess lipogenesis linked to estrogen-induced metabolic gene regulation. Elevated triglycerides as a precursor for vitellogenesis are therefore probable, although maladaptive in male fish. The significant rise in total protein levels in the MEF and ME groups aligns with E2’s role in stimulating protein synthesis to support vitellogenesis30,55, and unchanged albumin levels imply selective induction of reproductive proteins rather than a general hepatic protein increase56,57, with potential interactions between contaminants and cellular nucleoproteins leading to modified protein production and compromised cellular stability56,57. The decrease in phosphorus levels and increase in calcium concentrations in E2-treated groups mirror findings in trout, where E2-induced hypercalcemia was linked to vitellogenesis58. Elevated calcium may facilitate yolk protein synthesis and deposition, as observed in various teleost species30,59, while reduced phosphorus levels may reflect its utilization in energy-intensive pathways during hormonal regulation58. These findings demonstrate that E2-induced metabolic shifts in male goldfish extend beyond classical estrogen effects, engaging in complex reprogramming of energy and nutrient partitioning. Specifically, metabolic feminization including lipogenic reprogramming, targeted protein synthesis, and modified mineral metabolism suggests endocrine disruption can override male metabolic identity. This raises ecological concerns for wild male fish exposed to xenoestrogens and hints at potential productivity losses in aquaculture. Future research should explore the molecular mechanisms behind these changes, particularly E2’s impact on metabolic enzymes and pathways, as well as its role in energy partitioning and the implications for growth and reproduction in aquaculture systems.

Hormonal parameters

The decline in testosterone (T) levels in E2-treated groups supports previous research indicating that E2 suppresses androgen production by inhibiting steroidogenesis-related enzymes such as 17α-hydroxylase and 11β-hydroxylase60,61. This reduction likely compromises spermatogenesis and reproductive capacity, given that androgens like T and 11-ketotestosterone (11-KT) are essential for testicular development in teleosts62,63. Elevated E2 levels in the ME group suggest that social isolation enhances endocrine disruption, likely due to the absence of behavioral or physiological buffering typically provided by social interactions. Environmental estrogens disrupt sex steroid homeostasis through feedback loops or direct interference with steroidogenic enzymes64,65. The effects of xenoestrogens on steroidogenic pathways depend on factors such as dose, exposure duration, species, and developmental stage66. For instance, male rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) exposed to 4-NP showed increased plasma E2 without corresponding changes in T, indicating sex-specific steroid interference67. Documented T suppression in brown trout (Salmo trutta) larvae after BPA exposure68, and male common carp69 reinforces the broad-spectrum nature of E2-induced androgen suppression. Mammalian studies further support these findings via impaired gene and enzyme expression in T biosynthesis pathways70–74. Interestingly, the more pronounced T suppression in the MEF group suggests that female presence may amplify E2’s endocrine effects, potentially through behavioral or pheromonal modulation of hormone receptor sensitivity or metabolism a mechanism rarely explored in teleosts. This observation challenges the assumption that social interaction is always protective and calls for mechanistic studies to elucidate how social context influences endocrine disruption. E2 treatment also significantly suppressed T3 and T4 levels, especially in the MEF group, aligning with findings in rainbow trout where E2 reduced thyroid activity via reduced thyrotrope activity and peripheral deiodination58,75. The higher T4 levels in the ME group compared to MEF may reflect an adaptive response to isolation, with thyroid hormones playing a role in stress and energy regulation75–77. The paradoxical increase in T4 in the isolated ME group compared to MEF suggests a potential compensatory thyroid upregulation in response to isolation stress a novel mechanism that could be mediated by deiodinase activity in target tissues75–77. Investigating gene expression changes in deiodinases (e.g., dio1, dio2, dio3) and thyroid receptors may clarify this adaptive endocrine adjustment. Future research should explore the molecular mechanisms of these effects and the role of social interactions in mitigating hormonal disruptions in aquaculture.

Sperm activity and motility time

The results of this study demonstrate that sperm activity and motility time in goldfish are significantly influenced by both E2 exposure and social environment. The MF group exhibited the highest sperm activity and the longest motility duration, underscoring the crucial role of social/pheromonal stimulation in enhancing sperm function78,79. In contrast, both E2-treated groups (MEF and ME) experienced substantial reductions in these parameters, indicating a strong inhibitory effect of E2 on sperm physiology3,4. This aligns with findings from Roggio et al.80, who documented reduced motile sperm counts in killifish (Jenynsia multidentate) following EE2 exposure. These findings suggest that E2 not only compromises ATP production81,82, but may also directly impair mitochondrial function and flagellar assembly, which are critical for sperm mobility83. Interestingly, while E2 negatively impacted sperm function, male-female pairing (MF group) mitigated these effects, likely due to pheromonal cues that enhance male reproductive performance84. These findings align with previous research showing that diminished sperm motility occurred in Siamese fighting fish (Betta splendens) after four weeks of exposure to 100 ng L−1 EE2 and in mature male rats after seven days of EE2 administration at 10, 20, and 40 μg kg day−185,86. This suggests that natural pheromonal cues may help counteract E2-induced sperm damage, highlighting the harmful effects of E2 and the protective role of male-female interactions in reproduction.

GSI, testicular development and VSI

GSI were significantly influenced by E2 treatment and social context: the MF group exhibited the highest GSI, while the MEF group had the lowest, confirming a robust inhibitory effect of E2 on gonadal development80,87. The intermediate GSI in the M and ME groups suggest that social isolation alone has lesser impact than hormonal disruption88. The absence of significant variation in VSI across groups reinforces GSI, rather than VSI, as a more sensitive marker of reproductive health in teleosts89. A notable finding was the lower GSI in MEF compared to ME, indicating that female presence may exacerbate E2’s negative effects perhaps through interactions between exogenous and endogenous hormone signaling. Our study reveals that E2 exposure significantly reduces sperm activity, motility, and GSI, indicating its inhibitory effects on male reproductive function. However, male-female interactions mitigate some of these adverse effects, highlighting their crucial role in supporting reproductive success. While E2 had a strong inhibitory effect, male-female interactions mitigated some of its negative impacts, suggesting that social and behavioral factors play a role in counteracting endocrine disruption90,91. However, research on zebrafish and rare minnows showed a contradictory pattern, with EE2 exposure leading to a significant reduction in male GSI. GSI is widely used as a marker of sexual maturation and EDC exposure, with multiple studies confirming that estrogenic substances suppress testicular development 92,93,94,3,7,95. This study shows that E2 significantly impairs spermatogenesis, especially in isolated males, while male-female interactions help support testicular development. These findings align with previous studies on E2’s negative effects on male gonadal development in fish3,96. Conversely, the MF group displayed the most developed testes, with spermatozoa as the dominant cell type, emphasizing the crucial role of male-female interactions in promoting spermatogenesis. E2 inhibits meiotic division and delays spermatozoa formation7,61, with males in the ME group exhibiting poor testicular development dominated by spermatogonia. This suggests that E2 disrupts spermatogenesis by impairing meiotic division, potentially through its effects on Sertoli cells, which play a vital role in supporting germ cell development97. E2 inhibits spermatogenesis, whereas male-female interactions enhance testicular development, as evidenced by the MF group’s well-developed testes and abundant spermatozoa, underscoring the role of social interactions in reproductive health. This aligns with research demonstrating that female presence enhances testicular development and spermatogenesis in teleosts via hormonal and pheromonal signaling98,99. Female presence likely enhances gonadotropin and reproductive hormone secretion, counteracting E2’s inhibitory effects100,101. The MF group exhibited the most advanced testicular development, followed by the M group, while the ME and MEF groups showed the least development. This suggests that while the absence of E2 prevents inhibition, male-female interactions further enhance testicular maturation. E2 may inhibit spermatogenesis by disrupting Sertoli cell function, which is essential for spermatogenic cyst formation and spermatozoa development97. Estrogenic compounds like E2 have been shown to impair Sertoli cell function, leading to hypertrophy and structural alterations such as vacuolization and disrupted rough endoplasmic reticulum, as observed in nonylphenol exposure studies102. Additionally, E2 can affect Leydig cells by suppressing T production, further disrupting hormonal regulation essential for spermatogenesis86,103. This study confirms that E2 strongly suppresses GSI and spermatogenesis, while male-female interactions partially mitigate these effects. Further research should explore E2’s impact on Sertoli cells and gonadotropin signaling, and assess pheromone supplementation as a potential protective strategy.

Hepatic health

The histological evaluation of liver tissues revealed a clear gradient of E2-induced hepatic damage, modulated by social context. The M (isolated control) group displayed minor vacuolization, indicating some metabolic stress from social isolation. In contrast, the MF group exhibited minimal vacuolization and no necrosis, highlighting the protective effect of social interaction via stress buffering104,105. E2-treated males experienced varying degrees of hepatic damage depending on social context. The MEF group displayed moderate vacuolization, necrosis, and occasional hemorrhage, indicating that while E2 induces hepatic stress, female presence appears to mitigate E2 toxicity in the liver, likely by attenuating stress responses and stabilizing metabolic pathways104,105. The ME group suffered the most severe liver damage, including extensive necrosis, pronounced vacuolization, and frequent hemorrhage, suggesting that social isolation exacerbates E2 toxicity104,105. These results align with previous studies on E2-induced histological liver alterations in fish, including hepatocyte vacuolization, necrosis, and hepatomegaly in species such as rainbow trout106 and guppies107. Similar hepatic disturbances, including oxidative stress-related necrosis, have been reported in South American cichlid (Cichlasoma dimerus)108 and summer flounder (Paralichthys dentatus)109. Elevated Vtg levels in male fish, a key marker of estrogenic disruption, likely contribute to these effects by inducing metabolic strain, cytoplasmic vacuolization, and nuclear hypertrophy due to the inability to store excess Vtg, as observed in Hong Kong grouper, European eel, and summer flounder110–112. Histopathological alterations like those in this study were also documented in the kidneys and liver of rainbow trout exposed to E2 (30 mg/kg feed)106. Liver damage was a significant response in EE2-exposed adult male poecilid fish (Cnesterodon decemmaculatus), occurring in a concentration-dependent manner. Initial changes included mild macrovesicular steatosis and apoptotic cell death, progressing to severe macrovesicular steatosis and cystic degeneration filled with eosinophilic material113. Degeneration and necrosis of hepatocytes were also observed in rats administered high EE2 doses, likely due to estrogen-induced lipoprotein synthesis associated with vitellogenin and egg yolk production114. Apoptotic cell death has been attributed to EE2 hepatotoxicity, while cystic degeneration, though previously unreported in EE2-treated fish, may result from excessive Vtg accumulation and requires further investigation114. E2’s hepatotoxic effects are likely mediated by oxidative stress and redox imbalance. Although oxidative stress was not directly measured in this study, prior research suggests that acute E2 exposure disrupts redox balance, leading to cellular damage115. Over prolonged exposure, adaptive responses may mitigate oxidative stress, as observed in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides)116. The distinct differences between the MEF and ME groups highlight the interplay between environmental and endocrine factors in hepatic health. Social enrichment appears to counteract E2 toxicity, potentially by modulating stress responses or metabolic pathways. Importantly, these histopathological changes illustrate that behavioral context (social presence) can modulate endocrine and metabolic outcomes, signaling that endocrine disruptors must be evaluated within ecological and social frameworks. Monitoring liver function and histology is therefore essential in assessing EDC impacts.

Conclusion

This study investigated the effects of E2 exposure, social interactions, and their combined impacts on the growth, biochemical, hormonal, reproductive, and histological parameters of goldfish. The results clearly indicate that male-female interactions (MF group) without E2 treatment promoted the best overall growth performance, gonadal development, and liver health. In contrast, E2 exposure, particularly in isolated males (ME group), resulted in significant reductions in growth, testicular development, sperm characteristics, and liver integrity. The combination of social isolation and E2 treatment exacerbated these effects, particularly in the MEF group, where a more pronounced inhibition of spermatogenesis and liver damage was observed. Biochemically, E2 treatment led to altered glucose, cholesterol, triglyceride, and calcium levels, further underscoring its metabolic impact. These findings highlight the critical roles of both hormonal balance and social interactions in maintaining the health and reproductive success of goldfish. Future research should explore the dose-response relationship between E2 exposure and its effects on male reproductive health to identify specific thresholds for hormonal disruption. Investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying E2-induced impairments in spermatogenesis and liver function, including the role of specific genes and receptors, will provide deeper insights into the pathways involved. Future research should investigate the chronic effects of E2 on male fertility and offspring viability, including intergenerational impacts, while also assessing its ecological relevance in wild fish populations. Additionally, studies should explore how male-female interactions, potentially mediated by pheromones, may mitigate E2-induced reproductive and physiological disruptions. These investigations will improve understanding of endocrine disruption in aquatic species and inform conservation and aquaculture strategies to reduce the effects of environmental contaminants.

Materials and methods

Ethical information

All experiments were conducted in accordance with Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. In addition, the study followed the ARRIVE guidelines to ensure transparency and reproducibility of animal research. The experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Faculty of Natural Resources, University of Guilan. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering throughout the study, including the use of appropriate anesthesia during handling and sampling, careful monitoring of fish health, and humane endpoints to prevent any unnecessary pain or distress.

Fish maintenance

Adult goldfish, both male and female, with an average body weight of (male: 17.0 ± 0.3 g and total length of 10.8 ± 0.2 cm; female: 30.4 ± 0.5 g and total length of 13.0 ± 0.1 cm), were sourced from a private fish hatchery in Sangar, Guilan, Iran with a total of 180 fish obtained for the experiment. Prior to experimental treatments, all fish underwent a 30-day acclimation period in six 80 L aquaria at the wet laboratory facilities of the Faculty of Natural Resources, University of Guilan (Sowmeh Sara, Guilan, Iran), using well water. Each tank featured a physical filter and an air stone to ensure effective mechanical filtration and oxygenation. During the acclimation, the photoperiod was maintained at 12 h light/12 h dark (lights on at 08:00), and the water temperature was regulated at 19 °C. Water quality was monitored daily and maintained within optimal ranges for goldfish as: pH 7.5 ± 0.3, dissolved oxygen 7.8 ± 0.2 mg L−1, and alkalinity approximately 50 mg L−1 CaCO3. A 20% water replacement was conducted each morning before feeding to remove waste and maintain water quality, and fish were fed a commercial diet (35% crude protein, 6% fat, 5% fiber, 12% moisture; Tropical, Bangkok, Thailand) three times daily at 09:00, 13:00, and 19:00. After acclimation, all fish were judged healthy based on visual inspection displaying normal swimming behavior, coloration, and no signs of bacterial, fungal, or parasitic infection before the initiation of the experimental treatments.

Experimental design

The study comprised four treatment groups, each with three replicates (totally 12 tanks) and a combined total of 90 males and 30 female fish. All male fish averaged of 24.5 ± 0.5 g in weight and 12.5 ± 0.5 cm in total length, confirming uniformity across genders at baseline. Each 80 L aquarium was stocked with 10 fish and contained a physical filter and an air stone to maintain optimal water quality. Daily water quality (pH 7.5 ± 0.3, dissolved oxygen 7.8 ± 0.2 mg L−1, alkalinity ≈ 50 mg L−1 as CaCO3) was monitored and controlled via 20% daily water changes. E2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was first dissolved in ethanol 99% (Razi Chemical Company, Khuzestan, Iran) to ensure complete solubility (ethanol is a common solvent for steroid hormones and rapidly diffuses in aqueous environments without lasting toxicity at low volumes). After ethanol evaporated hormone was suspended in 1 mL sesame oil, which acts as a biocompatible carrier that enables slow-release over 14 days. Control fish received sesame oil alone to maintain consistency. The fish were distributed across 12 aquariums, with 10 fish in each tank, and the treatment groups were as follows: In the MF treatment (male-female control group), five male fish were paired with five female fish, and the males received a 1 mL sesame oil injection/fish, without E2 treatment. In the M treatment (isolated male control group), ten male fish were kept isolated and received only a 1 mL sesame oil injection/fish, without E2 treatment. In the MEF treatment (male-female experimental group), five male fish were paired with five female fish, and the males received E2 injection (5 mg kg body weight−1) along with a 1 mL sesame oil injection/fish. Finally, in the ME treatment (isolated male experimental group), ten male fish were kept isolated and received E2 injections (5 mg kg body weight−1) with a 1 mL sesame oil injection/fish. Each fish received two intraperitoneal injections (27-gauge insulin syringe, ~ 3 mm depth, completed in ~ 6 seconds), at a dose of 5 mg E2 kg body weight−1, with a 14-day interval between injections to sustain hormonally relevant exposure levels at target tissues. This dosing schedule was selected based on prior studies demonstrating effective endocrine response over a 28-day period. The dose was selected as suggested by Falahatkar et al.30, and sesame oil was used based on Mohammadzadeh et al.31. Anesthesia was induced using a clove powder solution at a concentration of 200 ppm32. The injection site received no additional anti-infective due to absence of adverse reactions; fish were monitored post-injection, and no signs of injury or infection at the injection site were observed. Routine observation found all fish were healthy and free from disease. An overview of the experimental design and sampling is presented in Fig. 5. Although both male and female fish were included in the MF and MEF treatment groups to evaluate the influence of social interactions, all experimental procedures, including biometric measurements, blood sampling, hormone and biochemical analyses, sperm evaluation, GSI and VSI determination, and histological assessments of the testes and liver, were conducted exclusively on male fish. Female fish were included solely to provide a natural social context, but they were not subjected to any sampling or analysis. This ensured that the data reflect the physiological, endocrine, and reproductive responses of male goldfish to the treatments, as intended in the study design.

Fig. 5.

Overview of experimental design and analyses of male goldfish (Carassius auratus) following a 28-day experimental period. The experimental setup involved four treatment groups of goldfish: MF group (5 males and 5 females receiving sesame oil injections), M group (10 males receiving sesame oil injections), MEF group (5 males treated with E2 + sesame oil, and paired with 5 females), andME group (10 males treated with E2 + sesame oil).

Growth performance

For this purpose, the weight and total length of male fish were recorded at the beginning and end of the experiment. The following growth performance parameters were quantified: weight gain (WG), specific growth rate (SGR), condition factor (CF), and survival rate (SR). These indices were calculated using the corresponding standard formulas, as detailed below, to assess the developmental responses to the experimental treatments:

|

Sampling procedure

The experimental duration was 28 days. At the termination of the study, fish were fasted for 24 h before sample collection. Ten fish from each treatment group were randomly selected for blood sampling. To euthanize the fish, they were removed from the aquariums and placed into an anesthetic solution containing 500 ppm clove powder solution, ensuring handling and minimizing stress during the procedure. Blood samples (1 mL) were collected from the caudal vein using 27-gauge heparin-coated syringes to prevent coagulation and ensure sample integrity. Plasma was separated by centrifugation at 1500 g for 10 min. The plasma samples were stored in 1.5 mL tubes and frozen at − 20 °C until further analysis.

Blood plasma biochemical analysis

Plasma biochemical parameters, including glucose, cholesterol, triglycerides, total protein, albumin, phosphorus, and calcium, were quantified from 10 samples per treatment using commercial assay kits (Pars Azmun, Karaj, Iran). Glucose concentration was determined through a colorimetric reaction based on the GPO-PAP method at 546 nm (Pars Azmun, Karaj, Iran; product number: 1500017, detection range 5–400 mg dL−1). Cholesterol and triglyceride levels were measured spectrophotometrically (UV/Vis 2100; Unico, New Jersey, USA) using the GPO-PAP and CHOPD-PAP methods, respectively, at 546 nm (Pars Azmun, Karaj, Iran; product numbers: 1500010 and 1500012, cholesterol detection range 5–500 mg dL−1; triglyceride detection range 5–700 mg dL−1). Total protein concentration was assessed by the Biuret method at 546 nm, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Pars Azmun, Karaj, Iran; product numbers: 1500028, detection range 0.5–15 g dL−1). Plasma albumin levels were analyzed using the Biuret method and a colorimetric assay with commercial kits (Pars Azmun, Karaj, Iran; product number: 1500001, detection range 0.2–6 g dL−1). Plasma phosphorus concentration was measured using a colorimetric reaction method, where molybdate reacts with phosphorus in the presence of acid to form molybdenum blue, which was quantified using the UV test method at 340 nm (Pars Azmun, Karaj, Iran; product number: 1500027, detection range: 0.2–30 mg dL−1). Calcium concentration was quantified through the photometric Cresolphthalein Complexone method at 570 nm (Pars Azmun, Karaj, Iran; product number: 1400007; detection range 0.2–20 mg dL−1).

Blood plasma hormonal analysis

Different hormones, including E2 (Product numbers: 4925 300; AccuBind ELISA Microwells, Monobind, Inc., Lake Forest, CA, USA; sensitivity for E2: 0.00082 μg dL−1), T (Product numbers: 3725-300; AccuBind ELISA Microwells, Monobind, Inc., Lake Forest, CA, USA; sensitivity for T: 0.0038 μg dL−1), triiodothyronine (T3), and thyroxine (T4) (Product numbers for T3 and T4 kits were 125-300 and 225-300; AccuBind ELISA Microwells, Monobind, Inc., Lake Forest, CA, USA; sensitivity for T3 and T4 was 0.004 μg dL−1 and 0.128 μg dL−1, respectively), were enzymatically assayed with commercial kits based on the manufacturer’s instructions. In summary, to measure plasma hormone levels, 50 µL of plasma was pipetted into each well, followed by the addition of 100 µL of prepared reagent. After vortexing for 30 s, the mixture was left to incubate for 1 h at 25 °C. The contents were then aspirated, and the wells were rinsed four times with 350 µL of washing solution. Subsequently, 50 µL of stop solution was introduced into each well and allowed to react for 20 sec. Absorbance was recorded using an ELISA reader (Epoch 2, Microplate Spectrophotometer, Winooski, Vermont, USA) set at a wavelength of 450 nm. The validity of this commercial kit for fish plasma was previously verified33. The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were calculated for each hormone as follows: E2 (5.5% and 7.8%), T (6.4% and 9.5%), T3 (8.3% and 9.2%), and T4 (5.0% and 6.4%), respectively.

Sperm assessment

At the end of the experiment, ten fish were randomly collected from each treatment and after the gentle abdominal massaging, the pure semen was precisely collected with an insulin syringe to prevent any contamination with mucus, urine, and feces. The percentage of activity of sperm and motility time were evaluated for each sample. For this purpose, 50 µL of water was added to 10 µL semen and following the activity of sperm and motility time (sec) was examined with a light microscope (×40 magnification, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The activity of sperms was considered as a percentage of motile sperms after activation until 100% of them were inactivated. The time between the activation of sperms and the stopping of their movement was used for calculating the motility time34.

Gonadosomatic and viscero-somatic indexes

The gonads and viscera were carefully removed from the body of 10 fish from each treatment, and the gonadosomatic index (GSI) and viscero-somatic index (VSI) were calculated. The GSI and VSI were determined using the following formulas:

|

|

Testicular and liver histology

The testes and liver of 10 fish from each treatment were subsequently placed in Bouin’s solution for fixation for two days, after which they were rinsed in 50% ethanol and stored in 70% ethanol (Razi, Khuzestan, Iran). A cross-section of the tissues was then dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol concentrations (70%, 96%, 100%) using an automatic tissue processor (Opti-Wax, SCILAB, England). The samples were then embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 5 µm using a microtome (2125 RT, Leica RM, Germany). The sectioned tissues were mounted on slides coated with albumin glue. After drying the slides at 37 °C in an oven, they were stained with hematoxylin and eosin solution (Sigma, Schnelldorf, Germany). The prepared slides were examined under a light microscope (Olympus BX51, Tokyo, Japan), and images were captured with a camera (VisiCam, Avantor, Radnor, PA, USA). The developmental stage of the gonads and histology of the liver hepatoxicity were classified based on35–38.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). Before analysis, the data were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and for homogeneity of variances using Levene’s test. A One-Way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to assess differences among experimental groups, followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test for comparisons. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 22.0, Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical analyses were conducted at a 95% confidence level, with differences considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the University of Guilan for providing the necessary resources and support throughout this study. Special thanks are extended to Dr. M. Abbasi, Dr. A.A. Rahdari, and H.A. Zamani for their invaluable assistance during this research. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge our colleagues for their assistance in sampling and fieldwork, whose contribution was instrumental to the successful completion of this study.

Author contributions

Hamed Abdollahpour: Visualization, Validation, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing–review & editing. Naghmeh Jafari Pastaki: Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing–review & editing. Bahram Falahatkar: Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Writing–review & editing. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The data analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Guo, C. et al. Cyp19a1a promotes ovarian maturation through regulating E2 synthesis with estrogen receptor 2a in Pampus argenteus (Euphrasen, 1788). Int. J. Mol. Sci.25, 1583. 10.3390/ijms25031583 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pan, Y. et al. Effects of exogenous hormones on spawning performances, serum gonadotropin and sex steroid hormone in Manchurian trout (Brachymystax lenok) during sexual maturation. Fishes9, 269. 10.3390/fishes9070269 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan, M. L., Shen, Y. J., Chen, Q. L., Wu, F. R. & Liu, Z. H. Environmentally relevant estrogens impaired spermatogenesis and sexual behaviors in male and female zebrafish. Aquat. Toxicol.273, 107008. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2024.107008 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang, D. et al. Expression characteristics of the Cyp19a1b aromatase gene and its response to 17β-estradiol treatment in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Fish Physiol. Biochem.50, 575–588. 10.1007/s10695-023-01291-5 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdollahpour, H., Pastaki, N. J. & Falahatkar, B. Gender differences in response to 17β-estradiol in zebrafish (Danio rerio): Growth, physiology, and reproduction. Aquac. Rep.36, 102065. 10.1016/j.aqrep.2024.102065 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciślak, M., Kruszelnicka, I., Zembrzuska, J. & Ginter-Kramarczyk, D. Estrogen pollution of the European aquatic environment: a critical review. Water Res.229, 119413. 10.1016/j.watres.2022.119413 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ribeiro, Y. M. et al. Chronic estrone exposure affects spermatogenesis and sperm quality in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol.98, 104058. 10.1016/j.etap.2022.104058 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li, M., Sun, L. & Wang, D. Roles of estrogens in fish sexual plasticity and sex differentiation. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol.277, 9–16. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2018.11.015 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amenyogbe, E. et al. A review on sex steroid hormone estrogen receptors in mammals and fish. Int. J. Endocrinol.2020, 5386193. 10.1155/2020/5386193 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu, Q. et al. Effects of exogenous steroid hormones on growth, body color, and gonadal development in Opsariichthys bidens. Fish Physiol. Biochem.50, 449–461. 10.1007/s10695-023-01275-5 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu, S. et al. Production of neofemale by 17β-estradiol and YY super-male breeding in mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi). Aquaculture581, 740479. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2023.740479 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotimi, D. E. et al. Energy metabolism and spermatogenesis. Heliyon10, e38591 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e38591 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuyama, S. & DeFalco, T. Steroid hormone signaling: multifaceted support of testicular function. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.11, 1339385. 10.3389/fcell.2023.1339385 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatef, A. & Unniappan, S. Metabolic hormones and the regulation of spermatogenesis in fishes. Theriogenology134, 121–128. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2019.05.021 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhat, I. A. et al. Testicular development and spermatogenesis in fish: Insights into molecular aspects and regulation of gene expression by different exogenous factors. Rev. Aquac.13, 2142–2168. 10.1111/raq.12563 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vizziano-Cantonnet, D., Benech-Correa, G. & Lasalle-Gerla, A. Estradiol-17β but not 11β-hydroxyandrostenedione induces sex transdifferentiation in Siberian sturgeon. Aquaculture596, 741735. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2024.741735 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang, C. S. et al. Combined effects of binary mixtures of 17β-estradiol and testosterone in western mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis) after full life-cycle exposure. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol.280, 109887. 10.1016/j.cbpc.2024.109887 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma, A., Kumari, P. & Sharma, I. Experimental exploration of estrogenic effects of norethindrone and 17α-ethinylestradiol on zebrafish (Danio rerio) gonads. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol.275, 109782. 10.1016/j.cbpc.2023.109782 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paraso, M. G. V., Morales, J. K. C., Clavecillas, A. A. & Lola, M. S. E. G. Estrogenic effects in feral male common carp (Cyprinus carpio) from Laguna de Bay, Philippines. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol.98, 638–642. 10.1007/s00128-017-2060-3 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weber, A. A. et al. Environmental exposure to oestrogenic endocrine disruptors mixtures reflecting on gonadal sex steroids and gametogenesis of the neotropical fish Astyanax rivularis. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol.279, 99–108. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2018.12.016 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carnevali, O., Santangeli, S., Forner-Piquer, I., Basili, D. & Maradonna, F. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals in aquatic environment: What are the risks for fish gametes?. Fish Physiol. Biochem.44, 1561–1576. 10.1007/s10695-018-0507-z (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ardeshir, R. A. et al. The effect of nonylphenol exposure on the stimulation of melanomacrophage centers, estrogen and testosterone level, and ERα gene expression in goldfish. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol.254, 109270. 10.1016/j.cbpc.2022.109270 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cossaboon, J. M., Teh, S. J. & Sant, K. E. Reproductive toxicity of DDT in the Japanese medaka fish model: Revisiting the impacts of DDT+ on female reproductive health. Chemosphere357, 141967. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.141967 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baatrup, E. & Henriksen, P. G. Disrupted reproductive behavior in unexposed female zebrafish (Danio rerio) paired with males exposed to low concentrations of 17α-ethinylestradiol (EE2). Aquat. Toxicol.160, 197–204. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2015.01.020 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meijide, F. J. et al. Effects of waterborne exposure to 17β-estradiol and 4-tert-octylphenol on early life stages of the South American cichlid fish Cichlasoma dimerus. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.124, 82–90. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.10.004 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blanco, A. M., Unniappan, S. Goldfish (Carassius auratus): Biology, husbandry, and research applications, in: Lab Fish Biomed. Res. pp. 373–408, 10.1016/B978-0-12-821099-4.00012-2 (2022).

- 27.Kakuta, I. & Takase, K. Exposure to neonicotinoid pesticides induces physiological disorders and affects color performance and foraging behavior in goldfish. Physiol. Rep.12, e16138. 10.14814/phy2.16138 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Filice, M. et al. Functional, structural, and molecular remodelling of the goldfish (Carassius auratus) heart under moderate hypoxia. Fish Physiol. Biochem.50, 667–685. 10.1007/s10695-024-01297-7 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Golshan, M., Alavi, S.M.H., Hatef, A., Kazori, N., Socha, M., Milla, S., Linhart O. Impact of absolute food deprivation on the reproductive system in male goldfish exposed to sex steroids. J. Comp. Physiol. B. 1–16, 10.1007/s00360-024-01570-4 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Falahatkar, B., Poursaeid, S., Meknatkhah, B., Khara, H. & Efatpanah, I. Long-term effects of intraperitoneal injection of estradiol-17β on the growth and physiology of juvenile stellate sturgeon Acipenser stellatus. Fish Physiol. Biochem.40, 365–373. 10.1007/s10695-013-9849-8 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohammadzadeh, M. et al. The effects of sesame oil and different doses of estradiol on testicular structure, sperm parameters, and chromatin integrity in old mice. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med.48, 34. 10.5653/cerm.2020.03524 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kookaram, K. et al. Effect of oral administration of GnRHa+ nanoparticles of chitosan in oogenesis acceleration of goldfish Carassius auratus. Fish Physiol. Biochem.47, 477–486. 10.1007/s10695-021-00926-9 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abdollahpour, H., Falahatkar, B., Efatpanah, I., Meknatkhah, B. & Van Der Kraak, G. Hormonal and physiological changes in sterlet sturgeon Acipenser ruthenus treated with thyroxine. Aquaculture507, 293–300. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.03.063 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nargesi, E. A., Gorouhi, D., Alavi, S. M. H. & Falahatkar, B. Spermiation induction in the common bream (Abramis brama) using sGnRHa and domperidone (Ovaprim): Sperm production, seminal plasma composition, and spermatozoa motility and fertilizing ability. Aquaculture597, 741902. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2024.741902 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marinović, Z. et al. Cryosurvival of isolated testicular cells and testicular tissue of tench Tinca tinca and goldfish Carassius auratus following slow-rate freezing. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol.245, 77–83. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2016.07.005 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seyedi, J., Kalbassi, M. R., Esmaeilbeigi, M., Tayemeh, M. B. & Moghadam, J. A. Toxicity and deleterious impacts of selenium nanoparticles at supranutritional and imbalance levels on male goldfish (Carassius auratus) sperm. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol.66, 126758. 10.1016/j.jtemb.2021.126758 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang, J. et al. Effects of Aloe-emodin on growth performance, biochemical parameters, and histopathology of goldfish (Carassius auratus). Aquaculture550, 737891. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.737891 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang, C. et al. Toxic effect of combined exposure of microplastics and copper on Goldfish (Carassius auratus): Insight from oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis and autophagy in Hepatopancreas and Intestine. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol.109, 1029–1036. 10.1007/s00128-022-03585-5 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riley, L. G., Hirano, T. & Grau, E. G. Disparate effects of gonadal steroid hormones on plasma and liver mRNA levels of insulin-like growth factor-I and vitellogenin in the tilapia, Oreochromis mossambicus. Fish Physiol. Biochem.26, 223–230. 10.1023/A:1026209502696 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, L.Y., Qi, P. P., Chen, M., Yuan, Y. C., Shen, Z. G., Fan, Q. X. Effects of sex steroid hormones on sexual size dimorphism in yellow catfish (Tachysurus fulvidraco), Acta Hyd. Sinica, 379–388. 10.7541/2020.046 (2020).

- 41.Ma, W. et al. Sex differences in the expression of GH/IGF axis genes underlie sexual size dimorphism in the yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco). Sci. China Life Sci.59, 431. 10.1007/s11427-015-4957-6 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cavallino, L., Rincón, L. & Scaia, M. F. Social behaviors as welfare indicators in teleost fish. Front. Vet. Sci.10, 1050510. 10.3389/fvets.2023.1050510 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morohashi, K., Baba, T. & Tanaka, M. Steroid hormones and the development of reproductive organs. Sex Dev.7, 61–79. 10.1159/000342272 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang, C. S., Huang, G. Y., Lei, D. Q. & Ying, G. G. Effects of steroid hormones and their mixtures on western mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis). Aquat. Toxicol.278, 107167. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2024.107167 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Antunes, D. F., Soares, M. C. & Taborsky, M. Dopamine modulates social behaviour in cooperatively breeding fish. Mol. Cell. End.550, 111649. 10.1016/j.mce.2022.111649 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schumann, S. et al. Social buffering of oxidative stress and cortisol in an endemic cyprinid fish. Sci. Rep.13, 20579. 10.1038/s41598-023-47926-8 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang, J., Yang, Y., Yang, Q., Wang, N. & Chen, S. Effects of sex steroid hormones (estradiol and testosterone) on growth traits of female, male, and pseudo-male Chinese tongue sole (Cynoglossus semilaevis). South China Fish. Sci.17, 27–34. 10.12131/20210030 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang, N., Wang, R., Wang, R. & Chen, S. Transcriptomics analysis revealing candidate networks and genes for the body size sexual dimorphism of Chinese tongue sole (Cynoglossus semilaevis). Funct. Integr. Genom.18, 327–339. 10.1007/s10142-018-0595-y (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brent, G. A. Mechanisms of thyroid hormone action. J. Clin. Invest.122, 3035–3043. 10.1172/JCI60047 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Phumyu, N., Boonanuntanasarn, S., Jangprai, A., Yoshizaki, G. & Na-Nakorn, U. Pubertal effects of 17α-methyltestosterone on GH–IGF-related genes of the hypothalamic–pituitary–liver–gonadal axis and other biological parameters in male, female and sex-reversed Nile tilapia. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol.177, 278–292. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2012.03.008 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yinger, R. V., Evangelisto, C. J., Tucker, N. C., Billingsley, J. M. & Clair, S. L. S. β-Estradiol supplementation regulates cholesterol synthesis independent of unsaturated fat consumption in adult zebrafish. Zebrafish21, 223–230. 10.1089/zeb.2023.0066 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun, S. X. et al. Environmental estrogen exposure converts lipid metabolism in male fish to a female pattern mediated by AMPK and mTOR signaling pathways. J. Hazard Mat.394, 122537. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122537 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ito, T., Yamamoto, Y., Yamagishi, N. & Kanai, Y. Stomach secretes estrogen in response to the blood triglyceride levels. Commun. Biol.4, 1364. 10.1038/s42003-021-02901-9 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kabpha, A., Phonsiri, K., Pasomboon, P. & Boonanuntanasarn, S. Effects of dietary supplementation of estradiol-17β during fry stage on growth, physiological and immune parameters, and gonadal gene expression in adult snakeskin gourami. Animal17, 100950. 10.1016/j.animal.2023.100950 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mukherjee, U. et al. Bisphenol A-induced oxidative stress, hepatotoxicity and altered estrogen receptor expression in Labeo bata: impact on metabolic homeostasis and inflammatory response. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.202, 110944. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110944 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kori-Siakpere, O. & Ubogu, E. O. Sublethal haematological effects of zinc on the freshwater fish Heteroclarias sp. (Osteichthyes: Clariidae). Afr. J. Biotech.10.5897/AJB07.706 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen, Y. et al. Growth, blood health, antioxidant status and immune response in juvenile yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) exposed to α-ethinylestradiol (EE2). Fish Shellfish Immunol.69, 1–5. 10.1016/j.fsi.2017.08.003 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Olivereau, M., Leloup, J., De Luze, A. & Olivereau, J. Effet de l’oestradiol sur l’axe hypophyso-thyroïdien de l’anguille. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol.43, 352–363. 10.1016/0016-6480(81)90295-1 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Patiño, R. & Sullivan, C. V. Ovarian follicle growth, maturation, and ovulation in teleost fish. Fish Physiol. Biochem.26, 57–70. 10.1023/A:1023311613987 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Govoroun, M., McMeel, O. M., Mecherouki, H., Smith, T. J. & Guiguen, Y. 17β-Estradiol treatment decreases steroidogenic enzyme messenger ribonucleic acid levels in the rainbow trout testis. Endocrinology142, 1841–1848. 10.1210/endo.142.5.8142 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de Castro Assis, L. H., de Nóbrega, R. H., Gómez-González, N. E., Bogerd, J. & Schulz, R. W. Estrogen-induced inhibition of spermatogenesis in zebrafish is largely reversed by androgen. J. Mol. Endocrinol.60, 273–284. 10.1530/JME-17-0177 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Billard, R., Fostier, A., Weil, C. & Breton, B. Endocrine control of spermatogenesis in teleost fish. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci.39, 65–79. 10.1139/f82-009 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miura, T., Yamauchi, K., Takahashi, H. & Nagahama, Y. Hormonal induction of all stages of spermatogenesis in vitro in the male Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.88, 5774–5778. 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5774 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arukwe, A., Celius, T., Walther, B. T. & Goksøyr, A. Effects of xenoestrogen treatment on zona radiata protein and vitellogenin expression in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Aquat. Toxicol.49, 159–170. 10.1016/S0166-445X(99)00083-1 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huang, T., Zhao, Y., He, J., Cheng, H. & Martyniuk, C. J. Endocrine disruption by azole fungicides in fish: A review of the evidence. Sci. Total Environ.822, 153412. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153412 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kortner, T. M., Mortensen, A. S., Hansen, M. D. & Arukwe, A. Neural aromatase transcript and protein levels in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) are modulated by the ubiquitous water pollutant, 4-nonylphenol. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol.164, 91–99. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.05.009 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Naderi, M., Zargham, D., Asadi, A., Bashti, T. & Kamayi, K. Short-term responses of selected endocrine parameters in juvenile rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) exposed to 4-nonylphenol. Toxicol. Ind. Health31, 1218–1228. 10.1177/0748233713491806 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bjerregaard, L. B., Lindholst, C., Korsgaard, B. & Bjerregaard, P. Sex hormone concentrations and gonad histology in brown trout (Salmo trutta) exposed to 17β-estradiol and bisphenol A. Ecotoxicology17, 252–263. 10.1007/s10646-008-0192-2 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mandich, A. et al. In vivo exposure of carp to graded concentrations of bisphenol A. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol.153, 15–24. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2007.01.004 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Feng, Y. et al. Bisphenol AF may cause testosterone reduction by directly affecting testis function in adult male rats. Toxicol. Lett.211, 201–209. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.03.802 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Han, X. D. et al. The toxic effects of nonylphenol on the reproductive system of male rats. Reprod. Toxicol.19, 215–221. 10.1016/j.reprotox.2004.06.014 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Labadie, P. & Budzinski, H. Alteration of steroid hormone balance in juvenile turbot (Psetta maxima) exposed to nonylphenol, bisphenol A, tetrabromodiphenyl ether 47, diallylphthalate, oil, and oil spiked with alkylphenols. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol.50, 552–561. 10.1007/s00244-005-1043-2 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Laurenzana, E. M. et al. Effect of nonylphenol on serum testosterone levels and testicular steroidogenic enzyme activity in neonatal, pubertal, and adult rats. Chem. Biol. Interact.139, 23–41. 10.1016/S0009-2797(01)00291-5 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Laurenzana, E. M., Weis, C. C., Bryant, C. W., Newbold, R. & Delclos, K. B. Effect of dietary administration of genistein, nonylphenol, or ethinyl estradiol on hepatic testosterone metabolism, cytochrome P-450 enzymes, and estrogen receptor alpha expression. Food Chem. Toxicol.40, 53–63. 10.1016/S0278-6915(01)00095-3 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yuan, M. et al. Estrogenic and non-estrogenic effects of bisphenol A and its action mechanism in the zebrafish model: An overview of the past two decades of work. Environ. Int.176, 107976. 10.1016/j.envint.2023.107976 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Peter, M. S. The role of thyroid hormones in stress response of fish. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol.172, 198–210. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2011.02.023 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abdollahpour, H., Falahatkar, B. & Van Der Kraak, G. The effects of long-term thyroxine administration on hematological, biochemical and immunological features in sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus). Aquaculture544, 737065. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737065 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pinzoni, L., Rasotto, M. B. & Gasparini, C. Sperm performance in the race for fertilization, the influence of female reproductive fluid. Roy. Soc. Open Sci.11, 240156. 10.1098/rsos.240156 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ljuboratović, U. et al. Effect of sex isolation on the reproduction of pikeperch (Sander lucioperca) submitted to the cycle shift from outdoor to fully controlled conditions. Aquaculture596, 741903. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2024.741903 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Roggio, M. A. et al. Effects of the synthetic estrogen 17α-ethinylestradiol on aromatase expression, reproductive behavior and sperm quality in the fish Jenynsia multidentata. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol.92, 579–584. 10.1007/s00128-013-1185-2 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Iwamatsu, T., Ishijima, S. & Nakashima, S. Movement of spermatozoa and changes in micropyles during fertilization in medaka eggs. J. Exp. Zool.266, 57–64. 10.1002/jez.1402660109 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Burness, G., Casselman, S. J., Schulte-Hostedde, A. I., Moyes, C. D. & Montgomerie, R. Sperm swimming speed and energetics vary with sperm competition risk in bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol.56, 65–70. 10.1007/s00265-003-0752-7 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kime, D. E. et al. Use of computer assisted sperm analysis (CASA) for monitoring the effects of pollution on sperm quality of fish; application to the effects of heavy metals. Aquat. Toxicol.36, 223–237. 10.1016/S0166-445X(96)00806-5 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kime, D. E. et al. Use of computer assisted sperm analysis (CASA) for monitoring the effects of pollution on sperm quality of fish; application to the effects of heavy metals. Aquat. Toxicol.36, 223–237. 10.1016/S0166-445X(96)00806-5 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 85.Montgomery, T. M., Brown, A. C., Gendelman, H. K., Ota, M. & Clotfelter, E. D. Exposure to 17α-ethinylestradiol decreases motility and ATP in sperm of male fighting fish Betta splendens. Environ. Toxicol.29, 243–252. 10.1002/tox.21752 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lin, P. H. et al. Downregulation of testosterone production through luteinizing hormone receptor regulation in male rats exposed to 17α-ethynylestradiol. Sci. Rep.10, 1576. 10.1038/s41598-020-58125-0 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hashimoto, S. et al. Effects of ethinylestradiol on medaka (Oryzias latipes) as measured by sperm motility and fertilization success. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol.56, 253–259. 10.1007/s00244-008-9183-9 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Guyón, N. F. et al. Impairments in aromatase expression, reproductive behavior, and sperm quality of male fish exposed to 17β-estradiol. Environ. Toxicol. Chem.31, 935–940. 10.1002/etc.1790 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shirdel, I., Kalbassi, M. R., Esmaeilbeigi, M. & Tinoush, B. Disruptive effects of nonylphenol on reproductive hormones, antioxidant enzymes, and histology of liver, kidney and gonads in Caspian trout smolts. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol.232, 108756. 10.1016/j.cbpc.2020.108756 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Xie, Q. P. et al. Growth and gonadal development retardations after long-term exposure to estradiol in little yellow croaker, Larimichthys polyactis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.222, 112462. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112462 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jiang, Z. T. et al. Preliminary trial of male to female sex reversal by 17β-estradiol in combination with Trilostane in spotted scat (Scatophagus argus). Fishes9, 1. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.737960 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 92.Söffker, M. & Tyler, C. R. Endocrine disrupting chemicals and sexual behaviors in fish–a critical review on effects and possible consequences. Crit. Rev. Toxicol.42, 653–668. 10.3109/10408444.2012.692114 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Thompson, W. A. & Vijayan, M. M. Antidepressants as endocrine disrupting compounds in fish. Front. Endocrinol.13, 895064. 10.3389/fendo.2022.895064 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gao, J. et al. Responses of gonadal transcriptome and physiological analysis following exposure to 17α-ethynylestradiol in adult rare minnow Gobiocypris rarus. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.141, 209–215. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.03.028 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lee, J., Zee, S., Kim, H. I., Cho, S. H. & Park, C. B. Effects of crosstalk between steroid hormones mediated thyroid hormone in zebrafish exposed to 4-tert-octylphenol: Estrogenic and anti-androgenic effects. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.277, 116348. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.116348 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Martinez-Bengochea, A. et al. Effects of 17β-estradiol on early gonadal development and expression of genes implicated in sexual differentiation of a South American teleost, Astyanax altiparanae. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol.248, 110467. 10.1016/j.cbpb.2020.110467 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]