Abstract

Articular cartilage’s avascular and aneural nature severely limits its intrinsic regenerative capacity, making injuries and degenerative diseases like osteoarthritis a significant clinical challenge. This review comprehensively examines the paradigm shift towards regenerative medicine strategies, focusing on the integration of the natural polyphenol curcumin into advanced cartilage tissue engineering. While curcumin possesses potent multi-modal therapeutic properties—including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-catabolic, and chondroprotective effects—its clinical translation is hindered by poor bioavailability and rapid metabolism. We explore innovative biomaterial-based solutions to these limitations, detailing the development of sophisticated DDSs such as nanoparticles, hydrogels (e.g., chitosan, gelatin methacrylate), and synthetic scaffolds (e.g., PCL, PLGA) that enable targeted, sustained release. The review critically analyzes the transition from conventional surgical techniques to emerging therapies like MSC-based treatments, gene therapy, and 3D-bioprinted constructs. Furthermore, we synthesize compelling clinical evidence demonstrating that bioavailable curcumin formulations (e.g., Meriva®, Theracurmin®) significantly improve pain, stiffness, and functional scores in OA and RA patients. By bridging cutting-edge biomaterial science with the ancient therapeutic wisdom of curcumin, this review highlights a promising frontier in restoring joint integrity and offers a critical roadmap for future research in combinatorial regenerative approaches.

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Curcumin, Cartilage tissue engineering, Cartilage regeneration, Anti- inflammatory, Curcumin-based biomaterial

Introduction

Cartilage is a specialized connective tissue essential for joint function, providing mechanical support, load distribution, and frictionless movement. Structurally, it comprises chondrocytes embedded within an extracellular matrix (ECM) dominated by collagen type II, proteoglycans, and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) like hyaluronic acid (HA) [1]. Unlike other tissues, cartilage lacks vasculature and innervation, rendering it inherently limited in self-repair capabilities. This vulnerability predisposes it to degenerative and inflammatory diseases such as osteoarthritis (OA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [2]. OA, the most prevalent degenerative joint disorder, involves progressive ECM degradation, chondrocyte apoptosis, and subchondral bone remodeling. Key molecular drivers include upregulated matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), particularly MMP-13, and a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS-5), which disrupt collagen (COL) and proteoglycan networks [3]. Conversely, RA is an autoimmune condition marked by synovial hyperplasia, immune cell infiltration, and cytokine-driven cartilage destruction. Pro-inflammatory mediators like Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNF-α), Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), and Interleukin-6 (IL-6) activate pathways such as Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), perpetuating inflammation and ECM catabolism [4].

Curcumin (Cur), a polyphenol derived from Curcuma longa, has garnered attention for its therapeutic potential in cartilage regeneration. Its bioactivity spans multiple mechanisms: (1) anti-inflammatory effects via suppression of NF-κB and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) pathways, reducing IL-1β and TNF-α levels [5]; (2) antioxidant properties through Reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging and upregulation of endogenous antioxidants like superoxide dismutase (SOD) [6]; (3) chondroprotection by inhibiting MMPs and promoting COL type II and aggrecan synthesis [7]; and (4) immunomodulation via macrophage polarization toward anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes. Despite these benefits, curcumin’s clinical translation is hindered by poor bioavailability, rapid metabolism, and low aqueous solubility [8].

To overcome these limitations, cartilage tissue engineering (CTE) strategies have innovatively integrated curcumin into biomaterial scaffolds and Drug Delivery Systems (DDSs). Natural polymers like alginate(Alg) [9], Chitosan (CH) [9], COL [10], HA, and gelatin (Gel) [11]are engineered into hydrogels for pH-responsive or sustained drug release, leveraging their biocompatibility and ECM-mimetic properties [12, 13]. Synthetic platforms, such as polycaprolactone (PCL) and Poly Lactic-Glycolic acid (PLGA), offer tunable degradation rates and mechanical strength, enabling controlled delivery via electrospun nanofibers or 3D-printed matrices. Hybrid systems, including fibrin / PCL composites [14, 15] or decellularized ECM/PCL scaffolds, combine structural stability with bioactivity, often enhanced by curcumin-loaded nanoparticles or microspheres [16] .Advanced DDSs like liposomes and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) further refine cartilage-specific targeting, exemplified by dCOL2-CM-Cur-PNPs, which home to damaged collagen II sites [17].

Clinical evidence underscores curcumin’s translational promise. Trials with Meriva®, a curcumin-phosphatidylcholine complex, demonstrated significant reductions in Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) scores and inflammatory markers (e.g., IL-6, CRP) in OA patients over 8 months [18]. Similarly, Theracurmin®, a nanoparticulate formulation, improved joint function and cartilage stiffness in post-mosaicplasty patients, validated by arthroscopic and MRI analyses [19]. RA studies highlight curcumin’s immunomodulatory efficacy, with reductions in Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28) and synovitis severity [20]. However, variability in trial outcomes—partly due to dosing inconsistencies—calls for standardized protocols and long-term follow-ups [20, 21]. This review synthesizes the curcumin’s multifaceted therapeutic roles, and cutting-edge CTE advancements. By bridging biomaterial innovation with clinical insights, we aim to accelerate the development of curcumin-based therapies for restoring joint integrity and mitigating degenerative disease progression.

Curcumin: bridging ancient wisdom and modern medicine

Curcumin multifaceted therapeutic applications and safety profile

Curcumin, a prominent natural polyphenolic compound with a characteristic yellow-orange hue, is primarily derived from the rhizomes of Curcuma longa Linn, a plant associated with the Zingiberaceae and Araceae families. This lipophilic molecule is known for its ability to swiftly permeate cellular membranes, influencing their structure and functionality [22–25]. First isolated from turmeric over 200 years ago, curcumin has a rich history of use in traditional medicine across regions like China, India, and Iran, particularly within Ayurvedic practices. Its therapeutic versatility has made it globally recognized for addressing a wide range of conditions, including diabetes, liver disorders, rheumatoid ailments, atherosclerosis, infectious diseases, and various cancers [26]. Curcumin boasts a strong safety profile, endorsed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), with an acceptable daily intake (ADI) of 0–3 mg per kg of body weight. Historically, its applications in Ayurvedic medicine extended to treating infections, eye inflammations, respiratory and digestive issues, wound care, and even alleviating hallucinations, underscoring its multifaceted medicinal value [26].

Curcumin structural insights

Curcumin, chemically known as (1E,6E)-1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione, with the molecular formula C₂₁H₂₀O₆, is a bioactive compound characterized by its unique chemical structure comprising two aromatic rings (phenyl groups) substituted with hydroxyl (–OH) and methoxy (–OCH₃) groups, linked by a seven-carbon chain featuring α,β-unsaturated β-diketone functionality [27]. This diketone group predominantly exists in a stable enol form in solution, contributing to curcumin’s distinctive properties, including its bright yellow color due to the presence of conjugated double bonds and planar structure. Its lipophilic nature, attributed to the aromatic rings and extended conjugation system, allows it to easily traverse cell membranes [9, 28, 29]. Renowned for its therapeutic potential, curcumin exhibits strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, making it effective in managing inflammatory conditions, metabolic syndrome, pain, degenerative eye diseases, and even certain cancers and neurological disorders [30]. Additionally, it acts as an epigenetic regulator and modulator of protease pathways, further expanding its therapeutic scope. However, curcumin’s clinical application is significantly hindered by its poor solubility and low bioavailability, resulting from limited absorption, rapid metabolism, and swift systemic elimination. To overcome these limitations, various strategies have been developed to enhance its bioavailability by improving its solubility, cellular permeability, and resistance to metabolic degradation, thereby unlocking its full therapeutic potential [28, 30].

Curcumin extraction methods

The isolation of curcumin, the principal bioactive compound from turmeric (Curcuma longa L.), is a critical step that significantly influences its yield, purity, and subsequent application. Extraction methods are broadly classified into conventional and novel (advanced) techniques, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

Conventional methods

Conventional techniques, historically the foundation of curcumin isolation, include solvent extraction (maceration), Soxhlet extraction, and hydro-distillation. Solvent extraction involves mass transfer, where a solvent (e.g., ethanol, methanol, acetone, or isopropanol) penetrates the dried, powdered plant matrix, dissolves the curcuminoids, and diffuses out [31, 32]. Ethanol is often the preferred solvent due to its effectiveness and higher safety profile; optimal yields have been achieved using ethanol at 30 °C for 1 h with an 8:1 solvent-to-solid ratio [33, 34].

Soxhlet extraction, invented in 1879, remains a benchmark method [31, 35]. It involves continuous cycling of hot solvent through the solid material, leading to high extraction yields, often near 100% for curcumin [36]. However, it is a lengthy process (e.g., 14 h), requires large volumes of solvent and high energy, and prolonged heating can degrade heat-sensitive compounds [33, 34, 36]. Hydro-distillation is primarily used to produce deodorized turmeric extracts by removing volatile essential oils while retaining the curcuminoid content, demonstrating efficacy comparable to solvent deodorization [33, 37].

Novel extraction methods

To overcome the drawbacks of conventional methods—such as long extraction times, high solvent consumption, and compound degradation—novel, eco-friendlier “green” technologies have been developed.

Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) utilizes cavitation phenomena generated by sound waves (20–100 MHz) to rupture cell walls, enhancing mass transfer. This method drastically reduces extraction time and solvent use. Optimized conditions using ethanol at 40 °C for 2 h can achieve yields of 73.18%, far more efficient than the many hours required for Soxhlet [36, 38]. Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) uses microwave energy to heat moisture within cells rapidly, creating internal pressure that ruptures the cell walls and releases bioactives. MAE has been shown to outperform both UAE and Soxhlet, yielding higher curcuminoid content (326.79 mg/g) with less energy and shorter times (e.g., < 30 min) [31, 39, 40].

Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE) employs hydrolytic enzymes (e.g., pectinase, cellulase) to break down polysaccharide cell walls, liberating bound metabolites. While environmentally friendly, its main drawback is a long incubation time [41, 42]. Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE), often using CO₂, operates at temperatures and pressures above the solvent’s critical point. It is ideal for heat-sensitive compounds due to its low operating temperature, though reported yields for curcuminoids can be relatively low (0.68–0.73%) [43, 44]. Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE) uses elevated temperature and pressure to maintain solvents in a liquid state far above their normal boiling points, dramatically enhancing extraction efficiency and speed. PLE can achieve high yields in very short times (e.g., 5–20 min), making it three to six times faster than Soxhlet extraction while using less solvent [31, 45, 46].

The choice of method depends on the desired balance between yield, purity, processing time, cost, and environmental impact. The trend is moving towards these advanced techniques, which offer superior efficiency, reduced ecological footprint, and better preservation of curcumin’s chemical integrity.

Curcumin synthesis methods

While extraction from turmeric is commercially prevalent, the chemical synthesis of curcumin is crucial for producing high-purity compounds and generating novel structural analogues for research. The development of synthetic routes has progressed through several key milestones [47].

The first successful synthesis was reported by Lampe in 1918, following the initial structural elucidation. This pioneering five-step route began with ethyl acetoacetate and carbomethoxy feruloyl chloride. It proceeded through a series of condensations, saponifications, and decarboxylation steps to build the diferuloylmethane skeleton, ultimately yielding curcumin [47, 48].

A significant simplification was introduced by Pavolini in 1950, who demonstrated that curcumin could be formed in a one-pot reaction by directly condensing two equivalents of vanillin with one equivalent of acetylacetone in the presence of boron trioxide. However, this method suffered from a very low yield of approximately 10% [47, 49].

The major breakthrough came from Pabon in 1964, who vastly improved upon Pavolini’s methodology. By employing a reagent system of boron trioxide, tri-sec-butyl borate, and n-butylamine in ethyl acetate at room temperature, Pabon achieved a dramatically increased yield of nearly 80%. This efficient protocol not only provided superior access to curcumin itself but was also successfully applied to synthesize eight structural analogues, establishing it as a foundational method for generating curcuminoid derivatives [47, 49].

Curcumin identification methods

Curcumin, the primary curcuminoid derived from turmeric (Curcuma longa), is identified and characterized through various analytical methods that leverage its unique physical and chemical properties. Among these, spectroscopic techniques like UV-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, along with chromatographic methods such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), are widely employed to analyze curcumin’s molecular structure, purity, and concentration [50–52].

High-Performance Thin-Layer chromatography (HPTLC)

HPTLC serves as a reliable technique for quantifying curcumin. This method uses densitometric scanning to determine curcumin concentrations, constructing calibration curves based on peak areas relative to standard concentrations (100–600 ng per band). Validation of the HPTLC method follows International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) guidelines, assessing parameters like linearity, precision, accuracy, limits of detection (LOD), limits of quantification (LOQ), and recovery. Intra-day and inter-day precision analyses confirm the reproducibility of results, as evidenced by low mean relative standard deviations (RSD).HPLC is often the preferred method for curcumin analysis due to its high sensitivity, accuracy, and efficiency. Its simple sample preparation and robustness make it particularly suitable for field applications and laboratories operated by minimally trained technicians. HPLC allows for sharp baseline separation of curcuminoids with low detection limits, making it indispensable for quality control and research involving complex mixtures [53, 54].

UV-Vis spectroscopy

Spectrophotometric techniques, including UV-Vis spectroscopy, are also employed for curcumin analysis. UV-Vis spectroscopy offers a rapid and straightforward approach for analyzing colored compounds like curcumin. Its non-destructive nature enables repeated testing on the same sample, with simpler waste disposal compared to other methods. However, it is limited to samples that absorb light in the UV-Vis range and may face interference from impurities or background noise, making it less suitable for low-concentration samples. Despite its limitations, UV-Vis spectroscopy remains a valuable tool for routine analyses due to its ease of use. However, HPLC is often preferred for curcumin characterization because of its superior accuracy and versatility in handling complex mixtures, making it ideal for both research and quality control applications [55–57].

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

NMR spectroscopy is an advanced analytical method utilized to investigate the molecular structure and behavior of compounds like curcumin. By employing nuclear magnetic resonance, this technique takes advantage of the magnetic properties of atomic nuclei to provide in-depth insights into molecular characteristics, including the identification of functional groups, structural elucidation, and the study of molecular interactions. Furthermore, NMR is instrumental in examining the conformational dynamics and stability of substances under varying environmental conditions [14, 58, 59]. When used alongside complementary techniques such as UV-Vis spectrophotometry and HPLC, NMR spectroscopy enhances the accuracy and depth of compound characterization. Together, these methods offer a robust and comprehensive approach to understanding curcumin and other bioactive molecules with precision [56, 60–62].

Challenges and innovations in overcoming defects in cartilage regeneration

Cartilage, a unique connective tissue with limited regenerative ability due to its avascularity and low cellular density, presents significant challenges for repair and regeneration. Damage to articular cartilage (AC) disrupts tissue equilibrium, often leading to the release of inflammatory cytokines like IL-1 and subsequent joint degeneration. The International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) grading system is a critical tool for assessing cartilage damage, categorized into four grades: Grade I involves superficial damage such as softening or minor irregularities; Grade II affects less than 50% of the cartilage depth; Grade III extends through 50–100% of the cartilage thickness without exposing the bone; and Grade IV represents full-thickness cartilage loss with bone exposure. This classification aids in diagnosing defects, determining treatment strategies, and predicting outcomes. Moderate injuries (Grades II and III) are often treated with surgical techniques like microfracture (MFX) or mosaicplasty, while severe damage (Grade IV) may necessitate more invasive interventions such as artificial joint replacement or osteotomies. Despite advancements in traditional treatments, challenges in cartilage regeneration persist, underscoring the urgent need for innovative therapeutic approaches to address these complex issues effectively [9, 61].

Traditional treatments: Non-operative methods for managing symptoms

Current non-operative approaches for OA focus primarily on symptom management and slowing disease progression through various pharmacological and biological interventions. These traditional treatments target different aspects of OA pathophysiology, from inflammation reduction to cartilage protection, and are typically employed for early-stage disease. While these modalities can provide meaningful symptomatic relief, their ability to regenerate native cartilage structure remains limited, often necessitating eventual surgical intervention in advanced cases. The following sections examine the evidence for these conventional therapies, including their mechanisms of action, clinical efficacy, and limitations in comprehensive OA management.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including Halofuginone, Etoricoxib, Ibuprofen, and Diclofenac, have demonstrated therapeutic potential for AC regeneration and OA management [9, 63, 64]. These agents exert their pharmacological effects primarily through COX enzyme inhibition, thereby reducing prostaglandin synthesis - key mediators of inflammation and pain perception [65–67]. The NSAID class encompasses both traditional non-selective inhibitors (e.g., ibuprofen, diclofenac) and selective COX-2 inhibitors (e.g., celecoxib), with the latter offering improved gastrointestinal tolerability while maintaining comparable efficacy [68, 69]. Major clinical guidelines, including those from the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) and American College of Rheumatology (ACR), recommend NSAIDs as first-line pharmacotherapy for OA-related pain [70, 71]. However, their chronic administration requires vigilant clinical oversight due to dose-dependent risks of gastrointestinal complications, cardiovascular events, and renal impairment [72, 73]. This safety profile has prompted ongoing research into optimized dosing strategies and alternative therapeutic approaches for long-term OA management [65].

Hyaluronic acid

Hyaluronic acid intra-articular injections have become a well-established treatment for OA-related joint pain, particularly when NSAIDs or analgesics like acetaminophen prove ineffective. The FDA has approved seven hyaluronate formulations for knee injections: Synvisc, Synvisc-One, Hyalgan, Supartz, OrthoVisc, Euflexxa (formerly Nuflexxa), and Gel-One, with emerging research exploring their potential application in other joints including the hip, shoulder, facet joints, and small joints of the hands and feet [74]. Native hyaluronate remains in the joint space for only 12–24 h post-injection [75], functioning primarily as a viscosupplement that supplements endogenous hyaluronan rather than simply acting as a joint lubricant. This limited residence time has driven the development of enhanced formulations, including high-molecular-weight (HMW) and crosslinked HA preparations that demonstrate extended intra-articular persistence (> 48 h in animal studies) and are gaining clinical acceptance [76, 77] .

The therapeutic benefits of HA injections are multifaceted, encompassing anti-inflammatory effects, mechanical cushioning, pain relief, and stimulation of proteoglycan and GAGs synthesis [78]. Clinical evidence suggests repeated HA injections can effectively maintain or improve knee pain without significant safety concerns [79], with high-molecular-weight HA (HMWHA) demonstrating particular promise by outperforming both conventional NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors in OA management [80]. However, while meta-analyses confirm HA’s statistically significant benefits for pain and function compared to placebo, the clinical meaningfulness of these effects remains modest, though the treatment does offer a superior safety profile relative to oral NSAIDs [77, 81].

Corticosteroid injections

Corticosteroids have been extensively utilized in both clinical practice and research settings to mitigate joint inflammation [9]. These small (< 700Da), highly hydrophobic molecules can reach the joint space through trans-capillary diffusion following systemic administration, though synovial fluid bioavailability remains significantly lower than systemic concentrations. This pharmacokinetic limitation has driven the development of intra-articular delivery methods, which not only enhance effective dosing but also enable administration of modified corticosteroid formulations with improved joint retention properties that would be unsuitable for systemic use. As a cornerstone of OA management, intra-articular corticosteroids are primarily indicated for joints with refractory pain and/or effusion. While providing symptom relief for up to 4 weeks post-injection [82], concerns about potential cartilage damage and disease progression have led to clinical guidelines recommending no more than 3–4 annual injections per affected joint [77, 83]. Several FDA-approved formulations are available for intra-articular use, including Hydrocortisone tebutate (Hydrocortone-TBA), Betamethasone acetate/sodium phosphate (Celestone Soluspan), Methylprednisone acetate (Depo-Medrol), Triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog-40), Triamcinolone diacetate (Aristocort Forte), Triamcinolone hexacetonide (Aristospan), and Dexamethasone sodium phosphate [77].

These injections specifically target inflammatory processes and pain associated with conditions like tendinitis and OA. A Cochrane review found they offer moderate pain relief and modest functional improvement, though with a side-effect profile similar to placebo. The evidence quality was rated very low due to study inconsistencies and reliance on small, low-quality trials [84]. While widely used for short-term symptom control, emerging data suggests intra-articular glucocorticoids may be less effective than physical therapy for long-term (1-year) symptom management [85]. This evolving understanding highlights the need for careful consideration of corticosteroid use in OA treatment algorithms, particularly regarding frequency of administration and alternative therapeutic options [65].

Natural products

Natural products such as terpenoids, polysaccharides, polyphenols, flavonoids, alkaloids, and saponins are increasingly being investigated for OA treatment due to their multi-target mechanisms, low toxicity, and cost-effectiveness [9]. However, their ability to fully replicate the complex zonal microstructure and composition of AC remains limited. Among these natural compounds, curcumin has shown promise for its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties. A 12-week study of 70 knee OA patients demonstrated that 1,000 mg daily of Curcuma longa provided greater pain relief than placebo, though the clinical significance was marginal and no differences were observed in effusion-synovitis volume on MRI [86, 87]. Bioavailability challenges have led to the development of enhanced formulations combining curcumin with piperine or BioPerine. Boswellia serrata, traditionally used for its anti-inflammatory effects, showed potential benefits in a meta-analysis of seven trials, though the evidence was limited by low study quality and incomplete adverse event reporting [88]. The efficacy of glucosamine and chondroitin supplements has been particularly inconsistent, with pharmaceutical-grade formulations showing modest statistical benefits over placebo but questionable clinical relevance [89, 90]. Notably, the placebo effect was substantial in trials of these supplements, with approximately 60% of participants reporting meaningful pain reduction regardless of treatment. Omega-3 fatty acids from fish oil demonstrated dose-dependent effects, with lower doses (0.45 g/day) showing better pain and functional outcomes than higher doses (4.5 g/day) over two years, though gastrointestinal side effects were common [91]. Krill oil, while demonstrating modest benefits in mild OA, showed no significant effects in moderate-to-severe cases [92]. Phytoflavonoids have exhibited potential for symptom improvement but carry risks of serious adverse effects, particularly with compounds like flavocoxid that have been associated with liver injury and pneumonitis [93]. While these natural products offer theoretically attractive therapeutic options for OA, most demonstrate only modest efficacy in clinical studies, with inconsistent results and variable safety profiles that warrant further investigation through rigorous, large-scale clinical trials [65] .

Platelet-Rich plasma (PRP) therapy

PRP therapy involves concentrating autologous platelets containing growth factors that modulate inflammation, stimulate angiogenesis, and promote tissue repair. While studies consistently demonstrate short- to medium-term analgesic effects of platelet-rich plasma in knee OA, substantial heterogeneity in preparation protocols and administration methods complicates definitive conclusions about its clinical efficacy [94]. Although some clinical studies report improvements in pain and function for cartilage injuries and early OA [95], a comprehensive meta-analysis of 40 trials (n = 3,035) found no significant advantage of PRP over hyaluronic acid, intra-articular steroids, or saline placebo for pain relief or functional improvement [96]. Notably, a randomized trial of 288 patients within this meta-analysis showed equivalent outcomes between PRP and saline for both symptomatic relief and structural changes [65, 97].

The therapeutic potential of PRP appears highly dependent on preparation methodology. Current evidence suggests leukocyte-poor PRP prepared via double-spin centrifugation (initial spin at 100×g followed by 1600×g for 20 min each) yields optimal results, achieving platelet recovery rates of 86–99% and approximately 6× baseline concentration while maintaining platelet integrity [98]. Bansal et al. further demonstrated that formulations containing approximately 10 billion platelets may produce sustained benefits in moderate knee OA [99]. However, significant variability in cellular composition, activation protocols, and injection regimens continues to challenge the standardization and reproducibility of PRP therapy in clinical practice [100].

Medications

Metformin originally developed for type 2 diabetes management has emerged as a potential disease-modifying agent for OA due to its pleiotropic effects extending beyond glycemic control [101]. Growing evidence suggests its anti-inflammatory properties may help mitigate joint degradation by modulating inflammatory pathways and cellular stress responses, thereby preserving cartilage integrity and soft tissues vulnerable to OA-related damage [102, 103]. These mechanisms could translate to clinically meaningful improvements in pain relief and physical function, positioning metformin as a promising adjunctive therapy for OA [104]. For OA specifically, metformin’s capacity to enhance joint integrity while improving functional outcomes [105] is complemented by its favorable safety profile and low cost. Further research is needed to optimize dosing regimens and validate its efficacy in OA management, but current evidence supports its repurposing as a disease-modifying therapy [65].

While primarily prescribed for dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disease prevention, statins have emerged as a promising therapeutic option for OA due to their pleiotropic effects. Growing evidence suggests these medications may modify OA progression through multiple mechanisms, positioning them as potential disease-modifying OA drugs (DMOADs) [106].

The anti-inflammatory properties of statins appear particularly relevant to OA pathogenesis [107]. By inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, TNF-α) while upregulating anti-inflammatory mediators, statins may disrupt the chronic low-grade inflammation that drives joint degeneration [108, 109]. This immunomodulatory action creates a more favorable joint microenvironment, potentially slowing cartilage degradation [110].

Notably, statins demonstrate direct chondroprotective effects by stimulating ECM production [111]. Experimental studies show enhanced synthesis of cartilage-specific components including proteoglycans and type II collagen - key structural elements whose depletion characterizes OA progression [112]. These anabolic effects may complement statins’ anti-catabolic actions, collectively preserving joint architecture and function [113].

Emerging evidence suggests statins may benefit the osteochondral unit more broadly [114]. Their positive effects on subchondral bone remodeling could help maintain joint biomechanics, while potential anti-osteoporotic properties may address the bone-cartilage crosstalk implicated in OA pathogenesis. This multi-tissue action makes statins particularly intriguing as they may simultaneously target several pathological features of OA [65, 115].

Emerging research suggests that angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), while primarily used to treat hypertension and heart failure, may also benefit OA patients by modulating the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) [116]. These medications appear to combat OA progression through multiple mechanisms: they reduce joint inflammation and oxidative stress by suppressing angiotensin II-mediated production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [117], help preserve cartilage integrity by inhibiting matrix-degrading enzymes [118], and may maintain synovial fluid homeostasis to improve joint lubrication and mobility. This dual-action potential makes RAAS inhibitors particularly valuable for OA patients who frequently have comorbid conditions like hypertension and metabolic syndrome [119, 120]. By simultaneously addressing cardiovascular risks and joint degeneration, these well-established medications could offer a novel therapeutic approach for managing both conditions [121]. While current evidence remains primarily preclinical, the strong mechanistic rationale and existing safety data support further clinical investigation into repurposing these drugs for OA treatment, potentially providing a comprehensive solution for patients with these interconnected health challenges [65].

Despite their widespread use, current nonoperative OA treatments demonstrate significant limitations in clinical practice. While palliative options like NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and HA provide temporary symptom relief, they generally fail to restore the complex zonal architecture of AC or halt disease progression. Natural products and emerging therapies like PRP show theoretical promise but lack consistent clinical evidence, while repurposed medications (metformin, statins, RAAS inhibitors) offer intriguing disease-modifying potential that requires further validation. This therapeutic gap underscores the need for both improved conservative treatments that can truly regenerate cartilage and better patient stratification to match individuals with optimal therapies. Future research should focus on developing interventions that not only alleviate symptoms but also address the underlying structural degeneration characteristic of OA progression [65].

Conventional treatments: surgical management of cartilage defects

The surgical management of cartilage defects has evolved significantly, offering both reparative and restorative approaches. Conventional techniques range from marrow stimulation procedures to advanced cell-based therapies, each targeting specific defect characteristics and patient needs. While these methods vary in complexity, they share the common goal of restoring functional articular surfaces. This section critically examines current surgical options, their biological rationale, and clinical outcomes.

Microfracture

Full-thickness AC lesions exhibit minimal intrinsic healing potential, necessitating surgical intervention to stimulate repair [122]. Among bone marrow stimulation techniques, microfracture has been extensively studied and refined since its development by Steadman et al. [123, 124]. The procedure involves creating perforations in the subchondral bone, allowing the release of bone marrow components, including Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), into the defect. These MSCs differentiate into fibrochondrocytes, forming a fibrocartilaginous repair tissue [125, 126].

Technical refinements in MFX have improved outcomes, including removal of calcified cartilage, creation of stable vertical lesion margins, and closely spaced perforations [127]. The resulting marrow clot adheres to the roughened subchondral surface, facilitating tissue formation [128]. However, the repair tissue primarily consists of type I collagen-rich fibrocartilage, which differs biomechanically from native hyaline cartilage (composed predominantly of type II collagen) [129]. Fibrocartilage has inferior load-bearing capacity, reduced GAGs content, and diminished shear resistance, contributing to long-term functional limitations [126, 130].

While MFX demonstrates good short-term clinical outcomes, longer follow-up reveals declining durability, with patient satisfaction decreasing over time [131]. Complications such as subchondral bone overgrowth (25–49% incidence) and incomplete defect filling further limit its efficacy [126, 132]. Additionally, factors such as larger lesion size, advanced age, obesity, and malalignment negatively influence outcomes [133] .

Despite these limitations, MFX remains a first-line option for small, focal defects in carefully selected patients [134]. Combining MFX with corrective osteotomy may improve outcomes in malaligned knees [133]. Future advancements, including biologic augmentation and optimized rehabilitation protocols, aim to enhance repair tissue quality and longevity [100].

Autologous Matrix-Induced chondrogenesis (AMIC)

Autologous Matrix-Induced Chondrogenesis is a single-stage cartilage repair technique that combines MFX with the application of a biocompatible scaffold to enhance healing [135]. While MFX alone relies on the formation of a blood clot containing MSCs, the lack of clot stability in larger defects can lead to MSC washout and suboptimal repair. AMIC addresses this limitation by using a collagen I/III membrane or other scaffolds to stabilize the clot, providing a structured environment for MSC differentiation into chondrocytes and promoting hyaline-like cartilage formation [100, 126].

First described by Behrens et al. in 2005, AMIC was developed as an enhancement of microfracture, particularly for larger defects where the clot alone lacks mechanical stability [136]. The scaffold acts as a temporary matrix, supporting cell migration and tissue formation while preventing clot dislodgement [137]. Unlike cell-based therapies (e.g., matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation, MACI), AMIC does not require cell harvesting or in vitro expansion, making it a simpler, more cost-effective single-stage procedure [138].

Clinical studies report improved mid- to long-term outcomes compared to MFX alone. While both techniques show comparable results at 2 years, MFX often exhibits declining function beyond this point, whereas AMIC maintains stable clinical outcomes for up to 5 years [126]. Additionally, AMIC demonstrates better defect filling and tissue quality, particularly in larger lesions [100, 131, 138] .

Despite its advantages, AMIC still results in fibrocartilage or hybrid repair tissue rather than true hyaline cartilage. However, its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and reproducibility make it an attractive option for focal chondral defects, especially where more complex procedures are not feasible. Future refinements in scaffold design and biologic augmentation may further enhance its regenerative potential [138, 139].

Scaffold-Augmented microfracture

Scaffold-augmented MFX represents an advanced evolution of traditional MFX techniques, where biocompatible scaffolds are implanted over the microfractured area to enhance structural support and create an optimal microenvironment for chondrogenesis. This approach addresses key limitations of standard MFX by preventing clot disruption, maintaining defect architecture, and promoting organized tissue regeneration. Three principal scaffold categories have emerged as particularly promising for cartilage repair: hydrogels, biodegradable synthetic polymers, and natural polymers [140].

Hydrogels have gained significant attention due to their remarkable similarity to native cartilage ECM. These three-dimensional, water-rich networks provide excellent conditions for cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation. Recent advancements have focused on improving their mechanical properties and biofunctionality, with some formulations now incorporating bioactive molecules to further stimulate regeneration. Their tunable physical characteristics allow precise matching with the mechanical demands of specific joint compartments, making them versatile tools in cartilage repair [141].

Biodegradable synthetic polymers, particularly polylactic acid (PLA) and polyglycolic acid (PGA), offer temporary structural support while gradually resorbing as native tissue forms. The development of copolymer systems like PLGA has enabled precise control over degradation rates to align with tissue regeneration timelines. These porous scaffolds typically feature interconnected pore networks (350–550 μm) with optimal porosity (35–45%) for cell infiltration and nutrient exchange. Modern fabrication techniques now allow customization of mechanical properties and architecture to match defect-specific requirements [142].

Natural polymer-based scaffolds utilizing COL, HA, or other ECM components provide inherent bioactivity that promotes cell-matrix interactions [143]. These biomimetic materials support chondrocyte phenotype maintenance and matrix production. Recent processing innovations have enhanced their mechanical resilience while preserving biological functionality, addressing previous limitations in load-bearing applications [100].

The field is now witnessing revolutionary advances with 4D bioprinting technologies that create dynamic, stimuli-responsive scaffolds capable of shape transformation in physiological environments [144]. Particularly noteworthy are magnetic-responsive constructs using silk fibroin-gelatin bioinks that can adapt to irregular defect geometries upon external magnetic field application [145]. These intelligent scaffolds represent a paradigm shift, offering unprecedented integration potential and long-term functional outcomes in cartilage regeneration [100].

Biological augmentation with bone marrow aspirate concentrate

Bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC) has emerged as a promising biological augmentation strategy for cartilage repair, particularly when combined with MFX procedures. BMAC is an autologous product rich in MSCs, growth factors, and cytokines that enhance tissue regeneration. Unlike isolated microfracture, which relies on the migration of endogenous MSCs, BMAC delivers a concentrated population of progenitor cells directly to the defect site, potentially improving the quality and durability of repair tissue [100, 146] .

The therapeutic potential of BMAC stems from its unique composition and multifaceted mechanisms of action. Compared to conventional intra-articular treatments like HA and PRP, BMAC offers superior regenerative capacity through its MSC content and immunomodulatory properties [99]. While PRP primarily provides platelet-derived growth factors (PDGF, TGF-β) with short-term effects, and HA functions mainly as a joint lubricant, BMAC promotes cartilage repair through MSC differentiation while simultaneously modulating inflammatory pathways [147]. This dual action addresses both structural degeneration and the inflammatory microenvironment characteristic of OA [100].

Clinical applications of BMAC involve bone marrow aspiration (typically from the iliac crest) followed by centrifugation to concentrate cellular components [99]. When used with microfracture, BMAC is applied directly to the prepared defect, creating a cell-rich environment for tissue regeneration. Preliminary studies demonstrate improved short- to mid-term clinical outcomes compared to MFX alone, with potential to delay more invasive interventions like total knee arthroplasty [25]. The anti-inflammatory effects of MSCs may contribute to these benefits by creating a more favorable environment for cartilage repair [100].

Despite these advantages, challenges remain regarding standardization of preparation protocols, optimal cell dosing, and long-term efficacy [148]. Comparative studies with other biological treatments are needed to better define BMAC’s role in cartilage repair. However, its unique combination of cellular and humoral factors positions BMAC as a compelling option for enhancing MFX outcomes, particularly in cases where more complex cell-based therapies may not be feasible [149].

Recent preclinical studies have demonstrated the enhanced regenerative potential of BMAC when combined with specialized scaffolds. One investigation evaluated cell-derived ECM scaffolds incorporating BMAC, comparing bone marrow MSC-derived (BM-d) and chondrocyte-derived (Ch-d) ECM scaffolds. Both scaffold types effectively promoted chondrogenesis in vitro, with progressive scaffold biodegradation observed over time. In vivo results using nude mice models showed both ECM groups developed cartilage-like tissue with superior integration and mechanical properties compared to MFX alone. While both ECM groups produced hyaline-like cartilage, the BM-d ECM scaffolds showed more significant calcium deposition over time, suggesting enhanced osteochondral potential. After 12 weeks, both ECM groups demonstrated complete defect filling with tissue resembling native cartilage, while the MFX group formed predominantly fibrocartilage [150].

Osteochondral autograft transfer system (OATS)

The Osteochondral Autograft Transfer system represents an effective biological approach for repairing focal cartilage defects by transplanting cylindrical plugs of healthy hyaline cartilage and subchondral bone from non-weight-bearing areas to damaged weight-bearing regions [151]. This technique offers several advantages, including rapid osseous integration, immediate structural support with viable chondrocytes, and the ability to treat various lesion sizes (typically < 2 cm², though effective for 2–4 cm² defects in young, active patients) [152]. Histological analyses confirm successful integration of transplanted grafts, maintaining articular surface congruity and preserving hyaline cartilage structure [153] .

Biomechanical studies in animal models demonstrate the procedure’s efficacy. Nakaji et al. [154] reported initial normal cartilage stiffness (107,695.1 ± 11,610.1 N/m²) in rabbit grafts, with temporary decreases during early remodeling phases before returning to baseline by 12 weeks (104,683.7 ± 3,311.5 N/m²). Kuroki et al. [155] found no significant alterations in cartilage stiffness or surface characteristics immediately post-implantation in porcine models. Long-term studies by Lane et al. [156] and Nam et al. [157] showed maintained chondrocyte viability (95%) and superior histological scores (21.6 ± 1.3 at 6 weeks) compared to untreated defects, though with transient biomechanical changes during integration.

Despite its advantages, the OATS technique has limitations. Donor site morbidity remains a concern, with reported rates of 2.3–12.6% [158], particularly for defects > 3 cm² [159]. The finite availability of autologous graft material also restricts its use for larger lesions. However, OATS demonstrates excellent long-term outcomes, with clinical benefits persisting beyond 15 years in appropriately selected cases [160]. When compared to allograft alternatives, OATS provides more reliable integration without risks of immune rejection, making it particularly valuable for smaller defects in young, active patients where preservation of native hyaline cartilage is prioritized [126].

Autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI)

First introduced in 1994, ACI is a two-stage procedure for repairing AC defects [122]. The first stage involves harvesting chondrocytes from a non-weight-bearing area of the joint, which are then expanded in vitro. In the second stage, the cultured cells are implanted into the defect, often covered with a periosteal patch or COL membrane. ACI is particularly effective for large lesions (up to 10 cm²), as it promotes the formation of hyaline-like cartilage with biomechanical properties approaching those of native tissue [161, 162].

Biomechanical studies demonstrate that ACI-repaired tissue can achieve stiffness comparable to healthy cartilage. Brittberg et al. [163] reported graft stiffness values of 2.4 ± 0.3 N (vs. 3.2 ± 0.3 N for normal cartilage), with hyaline-like repairs reaching 3.0 ± 1.1 N—significantly higher than fibrous tissue (1.5 ± 0.35 N). Vasara et al. [161] observed that repaired tissue stiffness averaged 62% of adjacent cartilage, with some cases exceeding 80%, suggesting near-native mechanical function. Henderson et al. [164] found that hyaline-like repairs exhibited stiffness matching or exceeding native cartilage in long-term follow-ups, though excessive stiffness in some cases raised concerns about abnormal load transmission and potential joint dysfunction.

Histologically, ACI yields superior repair tissue compared to microfracture, with hyaline or hyaline-like cartilage predominating in successful cases (65% vs. 28% in fibrocartilage repairs) [165]. However, complications such as periosteal hypertrophy, graft delamination, and reoperation rates remain significant drawbacks. These limitations spurred the development of matrix-induced ACI (MACI), which uses scaffold-based delivery to improve cell retention and reduce surgical morbidity [126].

Despite its regenerative potential, ACI’s two-stage approach, cost, and technical complexity restrict its widespread use. Further refinements in cell culture techniques and scaffold design may enhance its efficacy and accessibility [100].

Matrix-Induced autologous chondrocyte implantation (MACI)

MACI represents an advanced evolution of traditional ACI, combining autologous chondrocytes with a biodegradable COL scaffold to enhance cartilage regeneration. This next-generation technique eliminates the need for periosteal harvest by utilizing a biocompatible matrix that supports cell adhesion and proliferation, while allowing implantation via arthroscopy or mini-arthrotomy [166]. Preclinical studies demonstrate MACI’s ability to promote healing in full-thickness defects, with minimal inflammatory response to the scaffold itself [167]. The technique is particularly indicated for lesions > 2 cm², though it may also benefit smaller defects [168].

Biomechanical evaluations reveal MACI’s capacity to restore near-native tissue properties. Lee et al. [169] reported repaired tissue achieving 15% of native cartilage’s aggregate modulus in type II collagen scaffolds, while ovine models demonstrated stiffness reaching 16–50% of healthy tissue [170]. Griffin et al. [171] found MACI-treated equine cartilage recovered 70% of native compressive modulus, with comparable frictional properties (coefficients 0.42–0.52). However, shear modulus remained significantly lower (0.2–0.5 MPa vs. 1.0-1.5 MPa in healthy tissue), potentially affecting long-term durability under shear forces.

Clinically, MACI demonstrates superior outcomes to MFX at 5-year follow-up, with significant improvements in KOOS pain and function scores [126, 172]. The scaffold’s 3D architecture facilitates chondrocyte distribution and phenotype maintenance, yielding more hyaline-like tissue compared to fibrous repair [100]. While avoiding ACI’s common complications like periosteal hypertrophy, MACI retains the limitations of two-stage procedures and requires careful postoperative rehabilitation. Current evidence positions MACI as an effective option for larger defects where MFX proves inadequate, though long-term data beyond 10 years remains limited. Ongoing refinements in scaffold composition and cell-seeding techniques continue to optimize its regenerative potential [126].

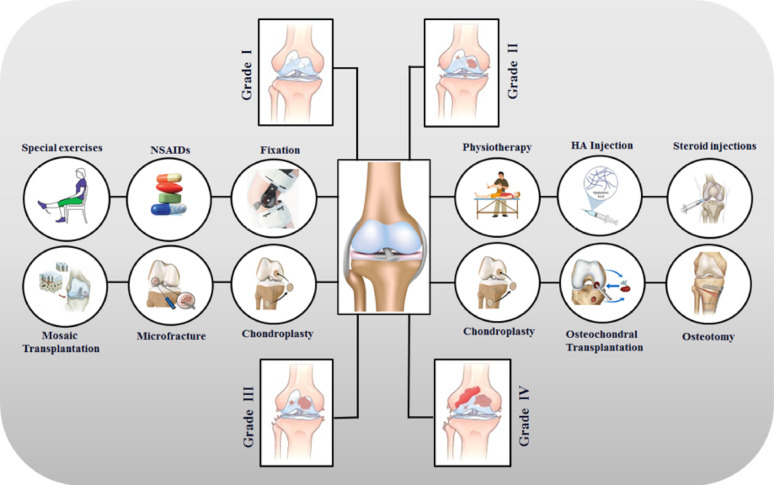

Current surgical techniques for cartilage repair demonstrate varying degrees of success, with optimal outcomes depending on careful patient selection and defect-specific approach selection. While no single method perfectly replicates native hyaline cartilage, technological advances continue to bridge the gap between biological and functional restoration. The integration of scaffolds, biologics, and minimally invasive approaches represents the next frontier in cartilage repair. Future developments must address long-term durability while improving accessibility and cost-effectiveness of these interventions Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Various treatment strategies to repair different grades of cartilage defects

Emerging therapies: innovations in cartilage repair

The persistent challenge of cartilage repair is being revolutionized by a new wave of regenerative therapies. Moving beyond palliative care and invasive surgeries, these innovations aim to achieve true biological restoration. This section explores three of the most promising frontiers in this field: cell-based strategies, genetic engineering, and advanced tissue engineering. Together, they represent a paradigm shift towards restoring the intricate structure and function of articular cartilage.

MSC -based therapy

MSC-based therapy represents a transformative approach in cartilage regeneration, harnessing the unique ability of MSCs to differentiate into chondrocytes while secreting bioactive molecules that modulate the joint microenvironment [173]. These multipotent cells are derived from various sources including bone marrow (BM-MSCs), adipose tissue (AD-MSCs), and umbilical cord (UC-MSCs), each offering distinct advantages in yield, proliferative capacity, and chondrogenic potential. While bone marrow-derived cells were historically predominant, their invasive harvesting and restricted expansion capability have shifted focus toward adipose-derived MSCs obtained through minimally invasive lipoaspiration and umbilical cord-derived cells demonstrating superior proliferative capacity while maintaining differentiation potential across passages [174]. Therapeutic efficacy is enhanced through hypoxic conditioning (5% O₂), which upregulates chondrogenic markers (SOX9, COL2A1, aggrecan) via HIF-1α stabilization, though prolonged hypoxia requires careful optimization to avoid necrosis. Growth factor supplementation, particularly TGF-β3 and BMP-7, significantly enhances chondrogenesis and matrix synthesis [175], with synergistic effects observed when combined with ghrelin through ERK1/2 and DNMT3A phosphorylation pathways [176]. Small molecules like kartogenin (KGN) provide a stable alternative for inducing chondrogenic differentiation in both BMSCs and synovial MSCs [9, 177].

Emerging cell-free strategies utilizing MSC-derived exosomes demonstrate comparable therapeutic effects through miRNA and protein cargo delivery [178], while co-culture systems with chondrocytes enhance matrix production via paracrine signaling [179]. Clinical meta-analyses report significant pain reduction (VAS: -2.1 ± 0.8; WOMAC: -15.3 ± 4.2 points) and functional improvement (Lysholm: +12.7 ± 3.5 points) at 12-month follow-up [180, 181], though MRI-based cartilage repair outcomes remain inconsistent across studies (WORMS score Δ = 0.84 ± 0.21, p = 0.07) [182]. While demonstrating excellent safety profiles (adverse event rate < 3% across 19 trials) [181], challenges persist in donor variability (20–30% non-responders) and standardization of cell dosing (range 10⁶-10⁸ cells/injection) [12, 65]. Current innovations focus on combinatorial approaches using 3D bioprinted scaffolds and oxygen-controlled bioreactors to improve cell retention (> 50% increase vs. suspension injection) [183], with ongoing phase III trials evaluating allogeneic UC-MSC formulations (NCT04241323) and engineered exosomes for targeted delivery [100].

Gene therapy

Gene therapy represents a transformative strategy for AC repair, aiming to overcome the limitations of conventional treatments by enabling the sustained, endogenous production of therapeutic factors directly within the joint environment. This approach involves the transfer of nucleic acids encoding therapeutic or regenerative proteins into target cells, facilitating continuous production and site-specific release for long-term treatment of AC injuries [184]. In preclinical models, this method has successfully treated injuries to cartilage, bone, and skeletal muscle by addressing the complex interplay between temporary mechanical incompetence and altered metabolic and inflammatory homeostasis [185, 186].

The therapeutic strategy primarily involves two mechanisms: promoting anabolism and inhibiting catabolism. The overexpression of anabolic factors, such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), members of the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family, and the transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) superfamily, has proven effective in stimulating chondrogenesis and the synthesis of cartilage-specific matrix components, leading to the formation of hyaline-like repair tissue [187]. Concurrently, the delivery of anticatabolic or anti-inflammatory agents, including interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) and interleukins 4 and 10 (IL-4/IL-10), can potently inhibit excessive cartilage degradation [188].

Beyond protein-encoding genes, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) have emerged as crucial regulators and promising therapeutic targets. A multitude of ncRNAs, including circular RNAs (e.g., circRSU1, circHIPK3) and microRNAs (e.g., miR-125a-5p, miR-30a-3p), have been shown to intricately regulate cell proliferation, inflammation, apoptosis, and ECM maintenance by modulating key signaling pathways like MEK/ERK and NF-κB through competitive endogenous RNA networks [189–192].

The successful clinical translation of gene therapy is contingent on the development of safe and efficient delivery systems. Polymeric biomaterials are particularly attractive as gene-activated matrices due to their tunable properties, which allow for the sustained and spatiotemporally controlled release of genetic cargo [184, 193]. Viral vectors remain highly effective; for instance, hydrogel-guided delivery of a recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector coding for IGF-1 enabled long-term cartilage repair and protection against OA in a large animal model [187]. Similarly, lentiviral vectors have been used to encode factors like CLOCK to counteract MSCs decay and promote regeneration [194]. Furthermore, exosomes are being explored as highly absorbable natural vectors for gene delivery [9, 195].

This technology also significantly advances CTE by enhancing the chondrogenic potential of MSCs. Genetic modification, through the overexpression of master regulators like SOX9 or precise gene editing using tools like CRISPR/Cas9 to knockout genes such as RUNX2, can direct differentiation towards a stable chondrogenic lineage and promote the production of a superior quality ECM, thereby improving repair outcomes [100, 196]. Thus, gene therapy offers a powerful tool for the effective, safe, and durable delivery of chondroprotective and chondroregenerative sequences.

Tissue engineering

Tissue engineering technology presents a highly viable strategy for AC defect repair, offering a paradigm shift from traditional methods. Since its development in the 1980s, CTE involves the combination of seed cells (e.g., chondrocytes, mesenchymal stem cells), biomaterial scaffolds, and bioactive factors to cultivate a biomimetic tissue in vitro for subsequent implantation and repair in vivo [197]. The relatively simple structure of cartilage, devoid of blood vessels and nerves, made it an early and ideal model for tissue engineering research [88].

The field was pioneered by Vacanti et al. [198], who in 1991 generated cartilage in nude mice using bovine chondrocytes seeded onto a synthetic biodegradable polymer scaffold. This was followed by the landmark creation of a human-shaped ear cartilage by Cao et al. [199] in 1997. These foundational studies paved the way for extensive research in small and large animal models, the latter being critical for clinical translation due to their complete immunogenicity and anatomical similarity to humans [200]. This progress has culminated in several commercial clinical products, such as MACI®, CaReS®, and BioSeed®, which are based on ACI onto matrices and have demonstrated positive repair outcomes [201]. Innovations like the biphasic MaioRegen scaffold, which targets osteochondral defects by mimicking both cartilage and bone layers, can avert two-stage surgeries and simplify the clinical process [9, 202].

A significant challenge in the field is that AC defects, particularly in OA, often extend beyond the cartilage into the calcified cartilage and subchondral bone. Therefore, current research focuses on developing zonal, microstructured scaffolds that can mimic this complex osteochondral unit to achieve complete and integrated repair. The scaffolds themselves are crucial, serving as an artificial ECM to provide structural support and stimulate cellular processes [203]. Ideal scaffolds must possess appropriate mechanical properties to mitigate cell death and promote tissue development [204], and are fabricated from both natural polymers (e.g., alginate, chitosan, collagen, hyaluronic acid) and synthetics (e.g., PLLA/PGA) [126].

Hydrogels are a particularly promising class of biomaterials due to their high-water content, porosity for nutrient transport, and ability to encapsulate cells, encouraging a spherical chondrogenic phenotype and reducing fibrous tissue formation [205]. Their properties, such as polymer chemistry, crosslinking density, and mechanical strength—which can range from under 1 MPa for natural variants to over 100 MPa for synthetic ones—are highly tunable [206]. A critical factor for success is maintaining physioxia (5% O₂) during cell culture, as this physiological oxygen concentration significantly promotes chondrogenesis, enhances GAGs and type II collagen production, and improves the compressive strength of the engineered construct [207, 208]. Despite these advances, challenges remain, including improving the often-limited mechanical strength of hydrogels for load-bearing joints and enhancing integration with the surrounding native tissue [126, 209].

In summary, the convergence of MSCs biology, gene editing, and biomaterial science is forging a new future for cartilage repair. While challenges in standardization, mechanical strength, and integration persist, the progress is undeniable. These innovative approaches are transitioning from laboratory concepts to tangible clinical solutions with demonstrated efficacy. The continued refinement of these therapies promises to finally provide durable and functional restoration for damaged joints.

Cartilage tissue engineering

Tissue engineering represents a promising avenue for cartilage repair, combining cells, biomaterials, and bioactive molecules to create functional tissue constructs [20]. Recent advancements in cell-based tissue engineering have enabled the integration of diverse cell types, matrices, and bioactive molecules, paving the way for innovative approaches to both AC and osteochondral regeneration. Nonetheless, a deeper understanding of cartilage’s limited healing capacity and the mechanisms underlying its regenerative potential is essential to develop more effective and sustainable therapeutic solutions [9, 210].

Cell sources in cartilage tissue engineering

Tissue engineering employs various types of seed cells, including autologous chondrocytes, MSCs, and iPSCs, each with distinct advantages and challenges [211].

Autologous chondrocyte transplantation (ACT) is a technique used to repair cartilage defects by implanting reparative chondrocytes [212]. The first generation of ACT used periosteum sealing, but issues such as rupture and hypertrophy led to the adoption of COL membranes in the second generation [213]. While ACT has demonstrated favorable long-term outcomes, challenges remain, including risks of chondrocyte leakage, uneven cell distribution, and the dedifferentiation of chondrocytes during in vitro culture. Additionally, the procedure is costly, technically complex, and requires joint incisions [211, 214]. The third generation of ACT introduced the use of carriers preloaded with chondrocytes to improve delivery and enhance cell survival post-surgery. Despite these advancements, limitations like limited chondrocyte availability and the need for two surgeries persist, highlighting the need for further innovation in this field [215].

MSCs are multipotent and self-renewing cells with significant chondrogenic differentiation potential, making them a valuable resource for cartilage regeneration. Derived from autologous tissues such as bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord, and synovial tissue, MSCs contribute to local repair and metabolic regulation [216, 217]. However, their therapeutic application faces challenges, including limited migration to injury sites and poor engraftment [138]. To address these limitations, exosomes (Exos), small vesicles secreted by cells, have emerged as a promising alternative. MSC-derived Exos carry bioactive molecules that mediate intercellular communication while avoiding risks like immunogenicity and tumorigenicity associated with cell transplantation [218]. Studies have highlighted the regenerative and immunomodulatory properties of MSC-Exos, demonstrating their anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and wound healing effects [211, 219].

iPSCs are reprogrammed somatic cells with pluripotency and self-renewal capabilities similar to embryonic stem cells, making them valuable for regenerative medicine and disease modeling [220]. Despite their potential, iPSC-based applications face challenges, including genetic instability due to viral vector use and risks of teratoma formation [221, 222]. iPSCs hold ethical advantages over embryonic stem cells and can be derived from healthy or diseased donors [223]. In chondrogenic differentiation, protocols utilizing factors like TGFβ1, TGFβ3, BMP2, and BMP4 have shown promise, with co-culture systems and small molecule inhibitors reducing off-target differentiation. However, safety concerns persist, and stringent controls are required before clinical approval. While progress has been made in laboratory-scale applications, iPSC-based therapies remain limited to research settings, highlighting the need for further refinement in differentiation protocols and safety measures [211].

Signaling in cartilage tissue engineering

Chondrocyte differentiation and cartilage repair are regulated by intricate signaling pathways involving key factors such as Wnt, nitric oxide (NO), RA, and protein kinase C (PKC). PKC promotes differentiation through the ERK-MAPK pathway and regulates the chondrocyte phenotype via the actin cytoskeleton [224]. Integrins play a crucial role in cell-matrix interactions, enabling mechano-transduction and force transmission, essential for cartilage tissue engineering [225]. Cytokines and growth factors, including TGF-βs, BMPs, IGF-1, and FGF, are vital for chondrogenesis and ECM metabolism [211, 226], with TGF-β inducing SOX9 synthesis and promoting collagen type II and aggrecan production [227]. BMPs further enhance cartilage synthesis while reducing catabolic cytokine activity [228]. Hypoxia, mediated by HIF signaling, enhances chondrogenesis by upregulating SOX9, COL II, and aggrecan while suppressing hypertrophy markers like COL I and X. Hypoxic conditions also improve GAG retention and HA synthesis in the ECM [229, 230]. Reactive oxygen species and oxygen tension influence chondrocyte metabolism, with hypoxia reducing oxidative stress and altering pH regulation. These complex interactions between signaling pathways, growth factors, and environmental conditions provide promising avenues for advancing CTE and repair strategies [231, 232].

Scaffolds in cartilage tissue engineering

Scaffolds are influenced by material selection, structural design, and fabrication methods. Both natural and synthetic polymers are widely utilized for these applications. Natural polymer-based hydrogels, often termed “ECM mimics,” incorporate ECM molecules such as COL, GAG, HA, agarose, Alg, fibrin, Gel, CH, and silk fibroin. These materials have been extensively studied due to their biomimetic properties. Synthetic polymers like polyglycolic acid, polylactic acid, polylactide-co-glycolide, polycaprolactone, and polyethylene glycol are also commonly employed [233]. Natural hydrogels degrade through enzymatic activity by cell-secreted enzymes like collagenase, gelatinase, and hyaluronidase, making them particularly suitable for applications requiring biodegradability [234]. Natural materials, while offering benefits such as biocompatibility and adaptability for modifications, often encounter limitations like inadequate mechanical strength and unpredictable degradation rates [235]. To overcome these challenges, integrating synthetic and composite materials is crucial, as they provide improved durability and more predictable performance [232].

Scaffold materials for cartilage tissue engineering

Biomaterials play a pivotal role in the success of tissue-engineered constructs for cartilage repair. An ideal scaffold must be biocompatible, promote cellular attachment and proliferation, and possess a degradation rate that aligns with the healing timeline of cartilage defects [236]. Studies indicate that initial cartilage repair occurs within 4–12 weeks post-implantation [237], with complete regeneration observed around 24 weeks [238]. Therefore, scaffolds should maintain structural integrity for 3–6 months to support tissue formation effectively while degrading gradually as new cartilage matures. Mechanical properties are equally critical, as the scaffold should mimic the biomechanical characteristics of native cartilage [239].

Biomaterials for scaffold fabrication fall into three categories: natural, synthetic, and composite materials. Each type offers unique advantages and can be tailored to achieve the desired properties for cartilage tissue engineering. The careful selection and design of these biomaterials are essential to ensure optimal performance and successful outcomes in cartilage regeneration applications [239].

Natural biomaterials

Natural biomaterials derived from plant and animal sources present significant benefits for tissue engineering applications. These materials are recognized for their inherent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and ability to support cell attachment and tissue remodeling processes [239, 240]. A common application of natural biomaterials is in the form of hydrogels, which are characterized by their high-water content and adaptability for injectability. This feature enhances their integration with cartilage repair cells and supports the preservation of the rounded AC phenotype, minimizing differentiation. Additionally, hydrogels are highly valued in studies involving cellular mechanical signaling, as they effectively transmit mechanical signals to encapsulated cells [211, 241]. Despite these advantages, natural biomaterials are not without challenges. They often exhibit low biostability, limited mechanical strength, and the potential to elicit inflammatory responses, which can complicate their use in clinical and research settings. Addressing these limitations remains a critical focus in the development of advanced biomaterials for tissue engineering [240].

Hyaluronic acid. HA is a critical component in cartilage repair due to its natural presence in synovial fluid, where it fosters an environment conducive to cartilage regeneration. It aids in the early differentiation of MSCs into cartilage by encouraging the accumulation of proteoglycans and COL2 [113, 211, 242]. Structurally, HA is an acidic glycosaminoglycan composed of D-glucuronic acid and N-acetylglucosamine, with a high molecular weight typically in the millions. Found abundantly in brain nerve tissue, connective tissue, and epithelial cells, HA plays vital roles in joint lubrication, wound healing, and water retention [14]. Recent advancements, such as the development of an electrospun cell-free fibrous HA scaffold by Martin et al., have shown promise. These scaffolds are designed to deliver growth factors like SDF-1α and TGF-β3, which enhance cartilage repair by recruiting mesenchymal progenitor cells and encouraging matrix deposition [243]. Li et al. developed a long-acting injectable hydrogel combining Epigallocatechin-3-0-gallate (EGCG), a green tea-derived antioxidant with strong ROS scavenging properties, and HA, which effectively captures excess ROS. When this hydrogel, loaded with adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs), was administered via intra-articular injection, it demonstrated significant therapeutic effects. Specifically, it shifted synovial macrophages toward the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, reduced the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, MMP-13, and TNF-α, and facilitated the formation of cartilage matrix, suggesting its potential in treating inflammatory joint conditions [244]. Moreover, the incorporation of methacrylate groups into HA allows for light-curing, making it a viable component for bio-ink applications. A commercially produced HA-based scaffold known as Hyaff-11 has shown significant success in cartilage repair. This scaffold exhibits time-controlled degradation, excellent biocompatibility, and the ability to reconstruct cartilage effectively. In studies using ACT with Hyaff-11, histological analyses revealed well-organized hyaline cartilage and ECM formation after 24 weeks. In contrast, untreated defects showed no signs of ECM formation over the same period.These advancements underscore HA’s versatility and potential as a cornerstone in cartilage repair therapies [14].

Collagen COL a key structural protein in connective tissue, cartilage, and skin, is highly valued in tissue engineering due to its biodegradability and low antigenicity. Recent studies have highlighted its potential in cartilage repair and scaffold development [211]. For instance, Lim et al. demonstrated that injecting clinical-grade soluble COL1 combined with human nasal septum-derived chondrocytes significantly enhanced cartilage repair in rats compared to COL injection alone [245]. Further advancements were made by Zhang et al., who investigated the impact of pore size in COL porous scaffolds on chondrocyte behavior. Using pre-made ice particulates as a porogen material, they fabricated scaffolds with controlled pore sizes and high porosity, ensuring efficient cell seeding and uniform distribution. In vivo testing in nude mice revealed promising results: histological analysis confirmed cell morphology, while Safranin O staining identified GAGs, and immunostaining detected type II collagen and aggrecan, indicative of cartilaginous tissue formation. Moreover, a correlation was established between scaffold pore size and mechanical properties. Scaffolds with pore sizes ranging from 150 to 250 μm exhibited the highest compressive modulus, suggesting they possess optimal mechanical characteristics for CTE applications. These findings underscore collagen’s significant potential in regenerative medicine and its role in advancing cartilage repair methodologies [246].

Chitosan CH is a naturally occurring linear polysaccharide found in the exoskeletons of crustaceans like crabs and shrimps, as well as in the cell walls of fungi. Structurally, it is composed of glucosamine units and contains glycosaminoglycans, which are known to support chondrogenesis and promote cell attachment and growth due to its hydrophilic surface. CH is highly regarded as a scaffold material in CTE because of its excellent biodegradability, antimicrobial properties, and physiological activity [14, 247]. Additionally, due to its structural resemblance to GAGs in the cartilage ECM, CH enhances the resilience of hyaline cartilage against mechanical stresses like shear and compression forces. By modifying its molecular mass and degree of deacetylation, chitosan’s mechanical properties, osteo-inductivity, and immunological compatibility can be further improved, making it a versatile and effective material for biomedical applications [91].

Research by Sadeghian et al. explored how CH concentration and crosslinking mechanisms influence the physical and mechanical attributes of 3D-printed pure CH scaffolds. Their findings highlighted that scaffolds with larger pore sizes exhibited higher swelling rates, while higher chitosan concentrations resulted in reduced swelling rates. This indicates that lower concentrations of chitosan, which promote greater swelling ratios, are more suitable for CTE applications. Moreover, air-dried scaffolds demonstrated superior elastic modulus compared to vacuum-dried ones, with a 10% CH concentration offering optimal printability and interconnected pores essential for tissue integration. The study also confirmed the biocompatibility of these scaffolds, as evidenced by successful chondrocyte attachment [248]. In related advancements, Zhou et al. developed catechol-modified chitosan (CH-C) hydrogels catalyzed by horseradish peroxidase and hydrogen peroxide. These hydrogels were found to support the proliferation and chondrogenic differentiation of BMSCs in vitro. When loaded with BMSCs, the CH-C hydrogels showed superior efficacy in repairing cartilage defects in vivo compared to hydrogels without cell loading [249]. Similarly, Lin et al. created a composite hydrogel scaffold using COL, carboxymethyl chitosan, and Arg-Gly-Asp peptide. This scaffold demonstrated excellent cell adhesion and biocompatibility, effectively enhancing BMSC adhesion and promoting cartilage regeneration [9]. Another promising approach involves combining CH and COL in a 1:1 ratio, as shown by Haaparanta et al., who utilized the freeze-drying method to fabricate cartilage scaffolds. This hybrid scaffold exhibited enhanced mechanical properties, such as improved stiffness, which is crucial for cartilage tissue engineering. Additionally, its high porosity facilitated cell migration and supported excellent chondrocyte viability. These findings collectively emphasize the potential of composite scaffolds to provide robust mechanical support and foster cellular integration for effective cartilage repair applications [250]. Huang et al. developed hydrogels incorporating BMSCs using CH and decalcified bone, demonstrating a notable enhancement in chondrogenic differentiation [251]. Additionally, another research effort designed an innovative CH/nano-hydroxyapatite (nHAP)/ Alg hybrid scaffold through extrusion bioprinting. This method employed an impregnation technique to integrate Alg and nHAP particles into the scaffold. The inclusion of Nhap particles contributed to improved elastic modulus, thermal stability, and cell attachment, fostering a stable physical and chemical microenvironment suitable for chondrocytes. Furthermore, scaffolds impregnated with sodium Alg exhibited enhanced swelling capacity, hydrophilicity, and cell viability, highlighting their potential for advanced tissue engineering applications [252].