Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent key drug targets, with approximately 30%–40% of all medications acting on these receptors. Recent advancements have uncovered the complexity of GPCR signaling, including biased signaling, which allows selective activation of specific intracellular pathways—primarily mediated by G proteins and β-arrestins. Among aminergic GPCRs, the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor has garnered attention for its potential to generate therapeutic effects without adverse outcomes, such as hallucinations, through biased agonism. This review delivers a comprehensive overview of 5-HT2A receptor-biased signaling and its significance in developing safer mental health therapeutics, particularly for depression and anxiety. We provide a critical evaluation of methodologies for assessing biased signaling, spanning from traditional radioligand binding assays to advanced biosensor technologies. Furthermore, we review structural studies and computational modeling that have identified key receptor residues modulating biased signaling. We also highlight novel biased ligands with selective pathway activation, presenting a promising avenue for developing targeted antidepressant therapies without psychedelic effects. Additionally, we explore the 5-HT2A receptor's role in memory processes and stress response regulation. Ultimately, advancing our understanding of 5-HT2A receptor-biased signaling could drive the development of next-generation GPCR-targeted therapies, maximizing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing side effects in psychiatric treatment.

Key words: 5-HT2A receptor, Biased agonism, Biased signaling, G protein-coupled receptors, Mental health disorders, Psychedelics

Graphical abstract

Biased signaling via GPCRs gains increasing attention as it can lead to the elaboration of more efficient and safer drugs. This review focuses on 5-HT2A receptor biased signaling from structural and pharmacological perspectives as a potential source of future CNS disease treatments.

1. Introduction

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are among the most intensively exploited drug targets1, as approximately 30%–40% of marketed drugs act through these receptors2. They also serve as molecular targets for 50% of newly launched drugs3. The function of GPCRs was classically explained by the ternary complex model, where receptor activation by an agonist leads to interactions with G protein and the initiation of specific signaling cascades. However, it is now recognized that GPCR signaling is much more complex4, involving multiple G proteins and even pathways independent of G proteins, such as those mediated by β-arrestins. This complexity has facilitated the design of biased ligands, which can selectively affect certain signaling pathways, leading to more efficient and selective drugs with fewer side effects.

Today, GPCRs are understood as allosteric proteins that bind to various ligands, altering their conformation to transmit signals from extracellular to intracellular spaces. Initially, the interaction of a single GPCR with different G proteins was thought to be the main source of functional selectivity. Later, it was discovered that phosphorylated GPCRs, including the 5-HT2A receptor, have a high affinity for arrestins, a finding that was first demonstrated for rhodopsin5,6.

The 5-HT2A receptor is widely distributed in both the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral tissues. Within the CNS, it is predominantly localized in serotonin-rich regions, including the neocortex, olfactory tubercle, hippocampus, and amygdala, as well as limbic and basal ganglia structures7. In the cerebral cortex, the highest density of 5-HT2A receptors is observed in the apical dendrites of layer V pyramidal neurons, suggesting its crucial role in modulating cognitive processes such as working memory, cognitive flexibility, and creative thinking8,9. In the human brain, autoradiographic analyses using ketanserin have revealed high 5-HT2A receptor density in layers III and V of the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital cortices, as well as in the entorhinal region. Significant expression has also been detected in the mammillary bodies of the hypothalamus, claustrum, and lateral nucleus of the amygdala9. At the subcellular level, the 5-HT2A receptor is localized in both presynaptic and postsynaptic terminals, dendritic spines, and neuronal somata, as confirmed by immunomicroscopy studies8,9. In the mouse hippocampus, this receptor is present in CA1 neurons, indicating its involvement in synaptic plasticity and memory processes9.

The 5-HT2A receptor plays a pivotal role in regulating cognitive, emotional, and neuroplastic processes. Its particularly high concentration on the apical dendrites of layer V pyramidal neurons in the cerebral cortex enables modulation of working memory, attention, and other executive functions through both glutamate release regulation and interactions with other receptor systems10. This receptor is critically important for hippocampal and amygdalar function—key structures involved in learning, memory formation, and emotional processing. Both regions receive dense serotonergic innervation from the raphe nuclei, and 5-HT2A receptor activation modulates their activity through processes such as enhanced spatial coding precision, regulation of GABAergic interneuron-mediated inhibition11, facilitation of memory consolidation processes. Influencing these processes is associated with therapies for diseases of the nervous system.

Although the 5-HT2A receptor antagonists and inverse or partial agonists are widely used to treat schizophrenia, cognitive impairments, and migraines, using its agonists therapeutically is challenging. This difficulty arises because the receptor can activate different effector proteins, specifically Gq and β-arrestin. Gq primarily associates with the receptor to initiate the activation of phospholipase C (PLCβ), which then leads to the production of secondary messengers like inositol triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG), resulting in calcium release and protein kinase C (PKC) activation12. Moreover, the 5-HT2A receptor interacts with β-arrestin, facilitating receptor internalization and desensitization while also initiating distinct intracellular signaling cascades13,14. These mechanisms contribute to different physiological effects, such as antidepressant and hallucinogenic outcomes.

It has been shown that receptor activation induces conformational changes that selectively engage the effector proteins. Pharmacological assays have demonstrated that known agonists like LSD typically stimulate both Gq and β-arrestin pathways15, 16, 17. Importantly, it has been found that selective activation of Gq is responsible for the hallucinogenic effects16,18. However, the exact physiological mechanisms underlying Gq activation and β-arrestin recruitment by serotonergic ligands remain poorly understood. This uncertainty drives ongoing efforts to develop receptor-biased agonists that preferentially activate one signaling pathway over the other19.

Considering the above, the purpose of this review is to summarize the current state of the art, regarding biased signaling via the 5-HT2A receptor to explore its structural and pharmacological aspects in drug design. We critically assess the potential application of 5-HT2A receptor-mediated functional selectivity as a basis for developing more effective and safer therapeutic agents.

2. Signaling pathways mediated by 5-HT2A receptor

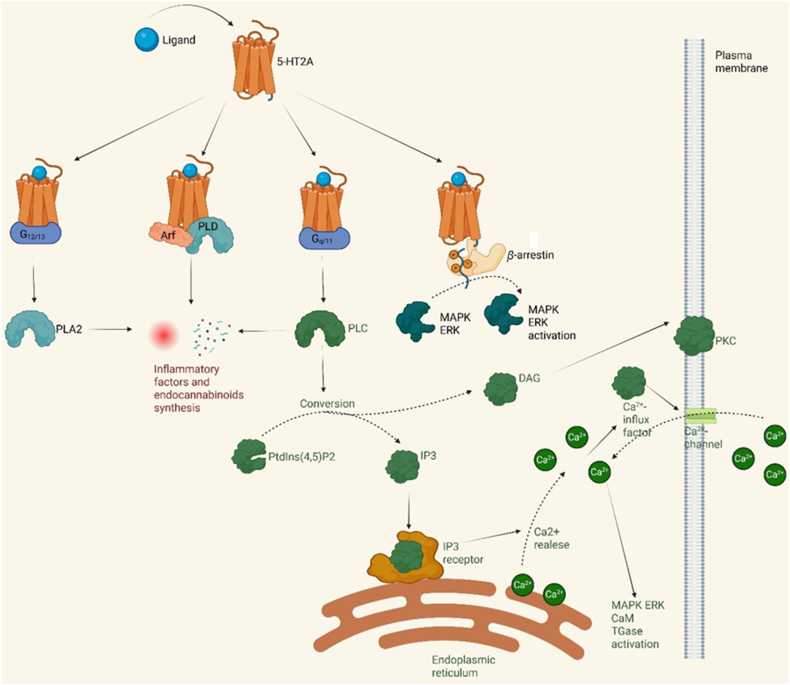

Activation of the 5-HT2A receptor leads to the engagement of a G protein, which subsequently triggers downstream signaling pathways (Fig. 1). Among these, the Gq/11-mediated activation of phospholipase C (PLC) is considered the most significant which is often referred to as the canonical pathway. Gq/11 proteins are primarily expressed in the central nervous system, and studies on Gq/11-deficient (Gq/11−/−) mice have demonstrated that the activation of this pathway is essential for the development of certain brain regions20.

Figure 1.

Most important signaling pathways induced by 5-HT2A receptors.

Upon activation, Gq/11 stimulates phospholipase C (PLC), which catalyzes the conversion of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P2) into inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3), a Ca2+-mobilizing second messenger, and diacylglycerol (DAG)21. IP3 binds to its receptors on the endoplasmic reticulum membrane, inducing the release of Ca2+ from the organelle. The released Ca2+ then triggers further downstream signaling, while DAG diffuses along the plasma membrane to activate membrane-bound forms of protein kinase C (PKC).

Studies on the human frontal cortex have demonstrated a significant positive correlation between 5-HT2A binding density and IP3 concentrations, confirming the crucial role of this axis in signal transmission22. Additionally, it has been shown that 5-HT2A activation leads to Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum, a process that can be inhibited by blocking either PLC or IP323. The increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration induced by 5-HT2A is not only the result of the release of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum but is also associated with the influx of Ca2+ from the extracellular space. It has been suggested that the initial rise in Ca2+ concentration, triggered by its release from the endoplasmic reticulum, activates a Ca2+-influx factor (CIF), which subsequently opens specific Ca2+ channels in the cell membrane24. Notably, 5-HT2A receptor activation modulates calcium channels, encompassing both voltage-gated (e.g., Cav1.2) and voltage-independent varieties, thereby influencing neuronal excitability and astrocytic intercellular signaling9,25.

The rise in intracellular Ca2+ levels significantly affects various proteins and intracellular pathways. It has been found that PLC activation and elevated Ca2+ levels are essential for the activation of molecules such as calmodulin (CaM) and transglutaminase (TGase)26. TGase is activated by Ca2+ in a dose-dependent manner27, and its activation leads to Rac1 transamidation28.

PLC is, however, not the only phospholipase that can be activated by the 5-HT2A receptor. Phospholipase A2 is activated through interactions between 5-HT2A and G12/13 proteins29, while phospholipase D directly binds to both 5-HT2A receptors and ADP-ribosylation factor (Arf)30. All of these phospholipases play crucial roles in the release of arachidonic acid from phosphatidylcholine, which in turn activates the pro-inflammatory response and promotes the synthesis of endocannabinoids31,32.

The MAP kinase pathway, particularly ERK1/2, plays a crucial role in 5-HT2A receptor signaling. ERK activation can occur through distinct mechanisms—in PC12 cells it requires increased intracellular calcium levels, CaM activation, and Src kinase activity, while in other cellular models, it may depend on Gβγ subunits of Gi/o proteins9,33.

An intriguing aspect of 5-HT2A receptor activity regulation involves its interaction with ribosomal S6 kinase 2 (RSK2). Activated through the Ras–ERK–MAPK cascade, RSK2 phosphorylates numerous transcription factors to modulate gene expression. Studies have demonstrated that RSK2 binds to the 5-HT2A receptor and inhibits its signaling, which may have implications for neurodevelopmental disorders, particularly since loss-of-function RSK2 mutations are associated with neurological diseases34. Furthermore, the 5-HT2A receptor participates in the activation of additional pathways, including JAK2–STAT3 signaling, potentially relevant for responses to hallucinogenic substances such as DOI33.

Another important downstream protein of the 5-HT2A receptor is β-arrestin, which exhibits two opposing mechanisms of action that appear dependent on the cell type and agonist involved35. β-Arrestin is believed to be responsible for desensitizing GPCRs, thereby attenuating G-protein signaling. Nevertheless, β-arrestin can bind to the activated receptor, leading to the formation of complexes with proteins such as Raf-1, MEK1, and ERK1/2, resulting in their activation36,37. Knockout studies have revealed that β-arrestin is essential for ERK activation in the frontal cortex by serotonin38. The 5-HT2A receptor has been shown to interact with β-arrestin 1 and β-arrestin 2, both in vitro and in vivo; however, it seems to have a preference for β-arrestin 238,39.

Different ligands of the 5-HT2A receptor can selectively activate specific signaling pathways, leading to diverse cellular responses. This functional selectivity (biased signaling) complicates the unambiguous characterization of signaling pathways, necessitating simultaneous analysis of multiple parameters across different cellular models. In summary, the two most significant downstream pathways of the 5-HT2A receptor are the 5-HT2A-Gq/11-PLC-IP3–Ca2+ axis and the β-arrestin-dependent MAPK ERK pathway (Fig. 1).

3. Structural aspects of 5-HT2A biased signaling

The binding of specific intracellular signaling or scaffolding proteins depends on the conformational states adopted by a given receptor. Increasing evidence suggests that multiple factors influence GPCR signaling bias, including receptor palmitoylation40,41, phosphorylation42,43, oligomerization or heterodimerization44. Significant attention has been devoted to functional selectivity in Class A GPCRs, the most populous subfamily, which is characterized by numerous similarities and conserved sequence motifs45. These conserved motifs often form molecular switches that regulate activation and induce conformational changes throughout the receptor. From this perspective, the structural aspects of activation and biased signaling should be considered across the entire family, as many mechanisms may be evolutionarily conserved.

Structural features responsible for biased signaling across the GPCR family were recently reviewed by Wootten et al.46 Notably, the article highlights several studies linking the conformation of transmembrane helix 7 (TM7) to arrestin recruitment47, 48, 49, 50. TM7 has also been identified as a key player in arrestin recruitment in recent studies on the angiotensin II type 1 receptor51, 52, 53. Computational analyses of experimental structures indicate that the intracellular conformation of TM7 is allosterically linked to the ligand-binding pocket. Compared to the G protein-bound conformation, the TM7 region in the arrestin-biased structure is twisted counterclockwise (as viewed from the extracellular side) above its conserved proline 7.50 kink. This conformational shift affects several residues, including N1.50, N7.46, and C7.47 (Cys296), and moves the intracellular portion of TM7 closer to TM3. The universal role of TM7 in Class A GPCRs is further supported by studies on signaling bias in opioid receptors54. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies, combined with molecular dynamics simulations, have highlighted the crucial role of the conserved W6.48 residue, the NPxxY motif, and N1.50 in this process55. The role of TM7 in biased signaling is further underscored by the observation that arrestin recruitment in many GPCRs is triggered by specific phosphorylation patterns. Arrestin–receptor interactions can take the form of core interactions or tail interactions56, involving the receptor's C-terminal tail, a sequence segment that follows helices H8 and TM7.

The 5-HT2A receptor interacts with multiple intracellular partners, including Gαq, Gαi/o, and Gα12/13 proteins57, raising questions about functional selectivity and its implications for drug design. Recent studies suggest that the psychedelic effects of 5-HT2A activation require activation Gq protein pathway16. Meanwhile, antipsychotic action of antagonists and inverse agonists of serotonin receptors might be affected by both their subtype selectivity and their bias towards specific G protein subtypes. It was recently shown that an approved antipsychotic drug, primavanserin, exhibits inverse agonism toward Gαi1, while simple antagonism toward Gαq/11 subtype58,59. Recent medicinal chemistry efforts revealed that except of the signaling bias, a proper subtype selectivity balance toward 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C subtypes is an important factor in antipsychotic properties of the primavanserin scaffold60. While understanding of structural basis of inhibition bias might be challenging, the recently solved X-ray structure of primavanserin-bound 5-HT2A receptor may serve as a foundation for future studies on this issue60.

Structural data obtained from X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM), while providing only static snapshots of receptor conformations, offer high-resolution insights into the low-energy states associated with different signaling modes. Until recently, the most extensive structural data on serotonin receptors were available for the 5-HT2B receptor48,61. However, the 5-HT2A receptor has also been the subject of recent structural biology studies19,62, 63, 64. Some experimental structures feature the receptor bound to biased ligands, providing key insights and serving as starting points for computational studies. In particular, the recent work of Gumpper et al.65 reveals a structure of the 5-HT2A receptor in complex with a β arrestin-biased compound and describes its distinct binding mode, characterized by unique interactions with the ‘toggle switch’ tryptophan (W6.48) that induces a cascade of conformational changes involving PIF motif residues and NPxxY motif. These conformational changes result in an altered arrangement of TM5, TM6, and TM7, being a non-canonical intermediate state between active and inactive conformations.

The third intracellular loop (ICL3) appears to play a particularly important role in 5-HT2A receptor interactions with arrestin (Fig. 2), as demonstrated by in vitro studies on over-expressed and purified ICL3 fusion proteins66. Another study highlights the crucial role of this loop in functional selectivity. Karaki et al.67 found that phosphorylation of the Ser280 residue in ICL3 differentiates between 5-HT2A receptor molecules activated by the hallucinogen DOI and those activated by the non-hallucinogen lisuride. This study describes a biased phosphorylation of the 5-HT2A receptor in response to hallucinogenic versus non-hallucinogenic agonists, which underscores their distinct capacity to desensitize the receptor.

Figure 2.

Structural features relevant for GPCR biased signaling marked on a cryo-EM 5-HT2B receptor structure coupled with beta-arrestin (PDB ID: 7SRS). The orthosteric pocket is shown in yellow. TM3 and TM7 are highlighted with black edges. Conserved N1.50, W6.48 and NPxxY motif are marked blue. Regions shown to affect arrestin coupling by 5-HT2A receptor are shown in red.

In silico studies indicate that the second intracellular loop (ICL2) may also contribute to biased signaling68. The role of ICL2 is further supported by findings that an I181E mutation in this loop significantly reduces the receptor's coupling to Gαq while simultaneously increasing its interaction with β-arrestin62. This underscores a common feature among many GPCRs, where ICL2 plays a crucial role in arrestin recruitment6. Furthermore, the involvement of both ICL2 and ICL3 in signal transmission has been demonstrated in a recent cryo-EM study on the closely related 5-HT2B receptor61.

Some computational studies aim to link conformational changes in the extracellular loops to signaling bias in serotonin receptors69. However, this aspect of receptor function remains complex, as shown by Kim et al. Their study revealed that the binding pocket of the 5-HT2A receptor can assume highly variable shapes while still inducing the same psychedelic effect62.

Several other structure-based studies have explored the mechanisms underlying ligand bias at the 5-HT2A receptor. For example, Perez-Aguilar et al.68 used molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to show that the intracellular loop 2 (ICL2) of the 5-HT2A receptor adopts a more outward-upward conformation when bound to hallucinogenic compounds. This distinct conformation was not observed with non-hallucinogenic ligands. Their analysis also identified critical amino acids, such as D172ˆ3.49 and H183ˆ3.52, that may contribute to functional bias.

4. Computational methods to identify 5-HT2A biased ligands

Ever since the breakthrough of technology, computational techniques have become an integral part of drug development, particularly in studies aimed at identifying molecules that target specific receptors. Recently, biased ligands for the 5-HT2A receptor have emerged as potential new-generation drugs due to their functional bias toward specific G-protein/β-arrestin signaling pathways, which can lead to differentiated physiological effects.

Currently, the rational design for biased agonists remains challenging due to the baffling mystery of functional selectivity of 5-HT2A receptor ligands. However, molecular dynamic (MD) simulations proved to be a powerful technique that has been widely exploited to study the structural basis of functional selectivity. Martí-Solano et al.70 applied MD simulations to learn the pattern of ligand–receptor interactions of known 5-HT2A biased ligands and utilized this knowledge to develop new biased ligands with desired profile. As a result, they discovered exclusive ligand features and hotspots that promote signaling bias. For instance, an interaction with residue N6.55 promotes bias for arachidonic acid (AA) signaling pathway and binding with S5.46 promotes bias for inositol phosphate (IP) signaling. Furthermore, multiple potential biased ligands were developed by using this structural insight for 5-HT2A receptor. Moreover, the biased behavior of the predicted compounds was verified through in vivo studies, suggesting their potential as candidates for future antipsychotic drugs70.

Likewise, Kossatz et al.71 explored the complex nature of 5-HT2A receptor signaling in response to different signaling probes by using MD simulations followed by in vitro and in vivo studies. They utilized small molecules (for example OTV1 (2-[5-(2,3-dihydro-1,4-benzodioxin-6-yl)-1H-indol-3-yl]ethan-1-amine), OTV2 (2-(5-phenoxy-1H-indol-3-yl)ethan-1-amine)) and Nitro-I (2-(5-nitro-1H-indol-3-yl)ethamine hydrochloride)) that were close analogs of 5-HT agonists as probes and observed their coupling preferences to provide an insight into the structural basis of functional selectivity. The outcomes showed that the type of ligand interaction with the extracellular loop 2 ECL2 mainly affects the potential of 5-HT2A receptor to activate different G protein subtypes. In addition, small molecules in this study have shown an overall preference for Gαq over Gαi and β-arrestin subtypes. Interestingly, it was shown that substitutions at position 5 of OTV1 could shift the coupling preferences to Gαi over Gαq. Moreover, different chemical modifications lead to the activation of the preferred G-protein subtype ultimately leading to different physiology responses as well71.

More recently, Wallach et al.16 developed a series of 5-HT2A biased agonists using molecular docking followed by MD simulations and mutagenesis study. The results showed that interactions with W336 are responsible for functional selectivity for β-arrestin 2 biased agonists. In addition, the psychedelic potential of identified 5-HT2AR ligands was determined in knock out mice study that might hold a therapeutic potential for future psychedelic drugs16.

Another noteworthy study by Kaplan et al.63 utilized structure-based virtual screening to assess a library of virtually generated 75 million tetrahydropyridine compounds (THPs). The best-performing 5-HT2A receptor model was screened against 75 million THP molecules, generating over 7 trillion complexes. The top 300,000 docked molecules were clustered yielding about 15,000 unique clusters. The top-scoring molecules from 4000 clusters were screened for unfavorable features and interactions with key residues. Of these, 205 chemically novel candidates were selected, leading to the synthesis of 17 highly functionalized THPs, which were then subjected to further validation. Initially, four of these molecules exhibited no activity against the 5-HT2A and 5-HT2B receptors; however, structure-based modifications resulted in the discovery of two 5-HT2A receptor agonists, (R)-69 and (R)-70, with EC50 values of 41 and 110 nmol/L, respectively. Notably, these agonists showed bias toward G-protein signaling over β-arrestin signaling. Cryo-electron microscopy analysis further corroborated the binding of these agonists to the 5-HT2A receptor. Interestingly, both agonists exhibited unusual signaling kinetics, demonstrating no psychedelic activity while still exhibiting antidepressant effects63.

5. HT2A receptor biased signaling and potential drugs

5.1. Antipsychotics and pimavanserin

Antipsychotic drugs are categorized into "typical" and "atypical" based on their antagonism towards dopaminergic and serotonergic receptors, as well as the tendency of typical drugs to cause extrapyramidal side effects. The etiology of schizophrenia involves dysregulation of the 5-HT2A receptor. Given the functional selectivity and the presence of distinct signaling pathways mediated by this receptor, it is essential to reconsider the classification of antipsychotics to better understand their therapeutic effects and side effects72.

Drugs commonly used to treat neuropsychiatric disorders exhibit a strong affinity for the 5-HT2A receptor. Typically, second-generation atypical antipsychotics function as neutral antagonists or inverse agonists within canonical 5-HT2A receptor pathways. However, recent research suggests that clozapine may display agonistic properties, either by interacting with other GPCRs or directly through the 5-HT2A receptor. Studies conducted in heterologous expression systems demonstrate that clozapine enhances Gi/o protein-dependent signaling in cells co-expressing the 5-HT2A receptor and the Gi/o protein-coupled metabotropic glutamate receptor 2 (mGluR2) in a GPCR heterocomplex. Additionally, clozapine activates the Akt pathway via the 5-HT2A receptor through a mechanism that is independent of β-arrestin.

In this context Martín-Guerrero et al.73 discuss the complex role of the 5-HT2A receptor subtype in mediating the effects of clozapine, emphasizing how genetic variations can influence drug response by altering signaling mechanisms. The His452Tyr polymorphism has been associated with a reduced response to clozapine in schizophrenia patients. This study investigates how this variant affects the signaling mechanisms caused by clozapine, revealing that the His452Tyr polymorphism in the 5-HT2A receptor influences both G-protein and β-arrestin signaling pathways. Specifically, in cells expressing the 5-HT2A-H452Y variant, the receptor exhibits diminished G-protein signaling. Furthermore, this polymorphism also affects β-arrestin-dependent signaling, indicating a nuanced impact of genetic variations on receptor function and drug efficacy.

In the case of clozapine, which can activate Akt via a β-arrestin-independent mechanism, the polymorphism reduces the ability to fully engage these phosphorylation-based networks. A further interesting insight is the one proposed by Gaitonde et al.74 where they examined the signaling profiles of six antipsychotic drugs with the aim of understanding how these may interact and which of them interact with G proteins or β-arrestins. Using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) assays, they detected activity of risperidone, clozapine, olanzapine and haloperidol as selective inverse agonists towards G proteins and demonstrated partial agonism of aripiprazole and cariprazine mainly at the Gαq family, and with minimal activity for β-arrestin recruitment. In particular, Kossatz et al.71 investigated the binding and activation of G-proteins and other pathways in order to shed light on a potential future design of antipsychotic drugs. Specifically, this study is based on how different G-protein subtypes are linked to psychosis-related effects and also to memory deficits. They focused on the role of Gαq and Gαi1 in modulating behavioral and physiological outcomes. Combining computational modelling studies, in vitro and in vivo experiments, they studied these pathways after stimulation with structurally closely related probes of the endogenous 5-HT agonist. For instance, both pro-hallucinogenic and anti-hallucinogenic properties of 5-HT2AR drugs depend on Gαi/o proteins and their pathways, thus psychotic behaviors are related to their modulation while memory deficits are dependent on Gαq activation.

Remaining in this line of research, it is also important to focus on another drug, an orally available, small-molecule, pimavanserin75. Pimavanserin is a well-known and potent drug that operates primarily through the 5-HT2A receptor. It has exhibited atypical antipsychotic activity across several preclinical models76. This FDA-approved atypical antipsychotic is indicated for treating Parkinson's disease psychosis (PDP), particularly addressing hallucinations and delusions associated with the condition. Approved and commercially available for the treatment of Parkinson's disease77, it is currently undergoing clinical trials to evaluate its efficacy in additional conditions, such as psychosis associated with Alzheimer's disease, irritability in autism, and Tourette's syndrome.

Its activity likely extends to the 5-HT2C receptor as well, raising questions regarding its precise mode of action. In particular, it is important to determine whether it functions as an antagonist blocking receptor activity. Alternatively, it may act as a reverse agonist, which not only blocks but also reduces the intrinsic activity of the 5-HT2A receptor in the absence of its agonist, serotonin. Pimavanserin is particularly valuable in PDP because, unlike other antipsychotics, it does not interact with dopaminergic D2 receptors. This characteristic suggests that it may help restore the balance between serotonin and dopamine in this disorder78. Given that atypical antipsychotics generally have a narrower range of side effects79, attempt to rationalize the effects of pimavanserin in terms of pathway activation, moving away from canonical 5-HT2A receptor activation. Current understanding holds that pimavanserin blocks the 5-HT2A–Gq pathway and exhibits inverse agonism on the 5-HT2A–Gi1 pathway. In contrast, the inactive compound glemanserin (MDL-11939) has been shown to block both pathways, however, it did not prove effective and was not marketed79. This leads to the conclusion that inverse agonism at the 5-HT2A–Gi1 receptor complex is essential for antipsychotic properties and that activation of this pathway is sufficient to induce psychosis-like symptoms. Consequently, future studies should focus on gaining a deeper understanding of this signaling pathway and the β-arrestin pathway79.

5.2. Antidepressants

Antidepressants remain among the most widely prescribed medications globally, playing a crucial role in treating a range of mental health disorders. Traditionally, these drugs have included monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs), and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). However, these treatments often present challenges such as delayed onset of therapeutic effects, variable efficacy, and the need for prolonged administration before achieving noticeable clinical improvement.

In recent years, attention has focused on the role of the 5-HT2A receptor in depression and the action of related drugs80. Unlike classical therapies, which predominantly modulate serotonin availability, biased agonism at the 5-HT2A receptor offers a unique approach by selectively engaging signaling pathways that contribute to antidepressant effects without triggering adverse responses. For instance, the development of ligands that bias signaling towards β-arrestin pathway may allow the antidepressant effects associated with 5-HT2A activation while avoiding the psychedelic effects seen with compounds like LSD or psilocybin. This differentiation is critical in moving towards safer, non-hallucinogenic treatments for depression. Furthermore, compounds such as IHCH-7086 and IHCH-7079, β-arrestin biased 5-HT2A serotonin receptor agonists, are experimental compounds currently under preclinical investigation in murine models. They have demonstrated the ability to harness β-arrestin signaling to achieve antidepressant effects without the psychoactive properties typical of traditional psychedelics81,82.

Very recently, Vargas et al.83 discovered that the activation of intracellular serotonin 5-HT2A receptors underlies the plasticity-enhancing and antidepressant-like effects of psychedelic compounds.

These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of functionally selective ligands in revolutionizing the pharmacological management of depression.

5.3. Anxiolytics

The serotonin 5-HT2A receptor plays a critical role in modulating both excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission in brain regions associated with stress and anxiety. The involvement of the 5-HT2A receptor in regulating stress responses has spurred interest in its potential as a target for anxiolytic therapies84,85. By exploiting biased signaling, researchers aim to develop drugs that provide anxiety relief through precise modulation of 5-HT2A-mediated pathways, avoiding the side effects associated with broader serotonergic interventions81,86,87.

Recent advances have identified small heterocyclic compounds with functional selectivity that act as Gq-biased agonists for the 5-HT2A receptor. These compounds not only exhibit anxiolytic properties but also demonstrate selectivity for 5-HT2A over 5-HT2B and 5-HT2C receptors88. The ability of these ligands to selectively activate specific signaling pathways may lead to more refined treatments for anxiety disorders, offering therapeutic benefits without the sedative or dependency risks associated with benzodiazepines and other traditional anxiolytics.

While psychedelics have shown efficacy in reducing anxiety in clinical settings, particularly for treatment-resistant cases and in palliative care, the primary focus of current research is to separate therapeutic benefits from hallucinogenic effects33,89. Instead of reiterating the psychedelic mechanisms detailed in Section 6, it is essential to emphasize that ongoing studies are exploring how functional selectivity, particularly through the β-arrestin pathway, could lead to non-hallucinogenic anxiolytics33,90. Such advancements could offer new treatment options that effectively manage anxiety symptoms while maintaining a favorable safety and tolerability profile.

5.4. Memory enhancers

5-HT2A receptors play a crucial role in modulating memory processes, particularly through their involvement in neural plasticity. 5-HT2A is widely expressed in brain regions associated with cognition: the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala. Its activation modulates synaptic plasticity, which underlies the brain's ability to adapt, from new connections, and recognize in response to experience. It has been noticed that disturbances in 5-HT2A receptor activity, associated with some mental disorders, can affect cognitive functions, potentially resulting in memory deficits or enhancements. Therefore, 5-HT2A receptors are being investigated as potential targets for psychiatric disorders accompanied by cognitive disturbances7,9,71,91. According to recent reports, exploring functionally selective ligands for the treatment of memory deficits holds significant potential, but this area remains underexplored.

The compounds discussed in Section 5 along with their effects are summarized in Table 119,74,79,82,92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97.

Table 1.

Selected 5-HT2A receptor ligands and their characterization in the context of functional signaling.

| Drug | 5-HT2A receptor ligand type | Preferred pathway(s) | Target receptor(s) | Functional effect | Clinical indication/status | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risperidone | Inverse agonist | Gαq, Gα11, Gα14 | 5-HT2A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT2C, 5-HT7, D2 |

Inhibition of 5-HT2A activity | Schizophrenia, bipolar disorder | 74,92,93 |

| Clozapine | Inverse agonist | Gαq, Gαi1, Gα11, Gα14, Gαz | 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT6, 5-HT7 |

Inhibition of 5-HT2A activity | Schizophrenia | 74 |

| Olanzapine | Inverse agonist | Gαq, Gαi1, Gα11, Gα14 | 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT3, 5-HT6, D2 |

Inhibition of 5-HT2A activity | Schizophrenia, bipolar disorder | 74,94 |

| Haloperidol | Inverse agonist | Gαi1 | 5-HT2A, D2 |

Inhibition of 5-HT2A and D2 activity | Schizophrenia, acute psychosis | 74,95 |

| Aripiprazole | Partial agonist | Gαq, Gαi1, Gα11, Gα14 | 5-HT2A, 5-HT1A, D2 |

Receptor activity stabilization | Schizophrenia, depression | 74,96 |

| Cariprazine | Partial agonist | Gαq, Gα11, Gα14 | 5-HT2A, 5-HT1A, D2, D3 |

Receptor activity stabilization | Schizophrenia, bipolar depression | 74,96 |

| Pimavanserin | Inverse agonist | Gαq, Gα11, Gαi1 | 5-HT2A, 5HT2C |

Inhibition of 5-HT2A activity | Parkinson's disease psychosis | 74,79 |

| Glemanserin | Antagonist | Gαq, Gαi1, | 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C |

Blocks 5-HT2A-mediated signaling | Investigational | 79,97 |

| IHCH-7086 | Agonist | β-Arrestin | 5-HT2A | Receptor activation | Investigational | 19,82 |

| IHCH-7079 | Agonist | β-Arrestin | 5-HT2A | Receptor activation | Investigational | 19,82 |

6. Psychedelics and 5-HT2A biased signaling

Psychedelics have intrigued humanity for millennia, initially as sacraments in various cultural and religious ceremonies, and more recently as tools for exploring consciousness and potential therapeutic agents98. These substances induce profound alterations in perception, mood, and cognition, phenomena collectively termed “psychedelic experiences”. Common features include visual and auditory hallucinations, altered sense of time, enhanced introspection, and sometimes mystical or spiritual experiences. The intensity and nature of these experiences vary based on the specific psychedelic, dosage, individual biochemistry, and environmental context. Banned from scientific research for decades they enjoyed renewed interest being investigated for various psychiatric disorders, e.g., depression or addiction99. Psychedelics can also prove to be beneficial in eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa100, managing of end-of-life anxiety101, disorders characterized by autonomic dysregulation102 or in chronic pain management103.

Classical psychedelics, such as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), psilocybin, and mescaline, exert their psychoactive effects primarily through agonism at the 5-HT2A receptor. The role of the 5-HT2A as a target of psychedelics was first proposed by Glennon104. This was later corroborated by studies demonstrating, that ketanserin (5-HT2A antagonist) is capable of reversing the psychedelic effects105 and also by studying the effect in 5-HT2A in knockout mice106.

It was noted that not all 5HT2A agonists elicit psychedelic effects. For instance, lisuride being a weak 5-HT2A agonist does not produce a psychedelic effect and the behavioral changes are mediated via 5-HT1A107. While activating the 5-HT2A receptor leads to the hallucinogenic effects of psychedelics, it is uncertain if this activation is necessary for all therapeutic benefits of psychedelic-assisted therapy108. The literature seems to be not conclusive in this regard109, 110, 111. There are currently ongoing efforts directed at developing non-hallucinogenic compounds for the treatment of depression or other disorders such as addiction90. One hypothesis suggests that the therapeutic and hallucinogenic effects of psychedelics may diverge due to functional selectivity at the 5-HT2A receptor, leading to different downstream intracellular signaling pathways112. Indeed, it was demonstrated that the activation of the 5-HT2A receptor via Gq and not β-arrestin 2 signaling is essential for inducing psychedelic-like effects, as assessed by the HTR (Head Twitch Response)16. It was also shown that disrupting Gq–PLC signaling reduces the HTR, indicating that a minimum level of Gq activation is necessary to produce psychedelic-like effects aligning with the observation that certain 5-HT2A partial agonists, such as mentioned above lisuride, do not produce psychedelic effects.

The therapeutic potential of psychedelics, particularly for treating depression, has attracted considerable attention. Studies have shown that compounds like psilocybin can significantly reduce depressive symptoms113. However, recent research has questioned the role of the 5-HT2A receptor in mediating these antidepressant effects, suggesting that the benefits may occur independently of the hallucinogenic properties and possibly without engaging the 5-HT2A receptor at all114. Notably, this study also supports previous findings115 showing that lisuride produces antidepressant effects in mouse models despite lacking psychedelic activity. This observation aligns with a broader effort to develop non-hallucinogenic compounds that preserve the therapeutic benefits of psychedelics90,116,117, where functional selectivity is thought to play a crucial role. For instance, β-arrestin-biased ligands have demonstrated antidepressant activity while this β-arrestin signaling was insufficient to induce hallucinogenic action19.

It is believed that long-term improvements elicited by psychedelics stem from rapid and lasting neuroplasticity118. It remains unclear why certain 5-HT2A receptor ligands can promote neuroplasticity and induce sustained therapeutic behavioral effects without producing hallucinogenic responses, while other 5-HT2A agonists fail to promote plasticity altogether. Notably, serotonin itself does not trigger psychedelic-like effects. This puzzling observation cannot be readily explained by conventional biased agonism, as serotonin is a balanced 5-HT2A agonist with high potency and efficacy for activating both G protein and β-arrestin signaling pathways. Therefore, another form of functional selectivity was proposed, known as location bias to explain signaling differences between endogenous membrane-impermeable and membrane-permeable ligands83.

Animal models, particularly the head twitch response (HTR) in rodents, have been instrumental in studying psychedelics. HTR is closely linked to the hallucinogenic effects of these compounds in humans and serves as a marker for distinguishing psychedelics from non-hallucinogenic substances119. Additionally, drug discrimination tests (DDT) in rodents have provided valuable insights into the pharmacological properties of psychedelics, although these methods require extensive training and are labor-intensive120. Newer methods such as PsychLight can predict hallucinogenic potential and measure 5-HT dynamics in behaving mice REF116.

Understanding the nuanced mechanism of 5-HT2A receptor activation and signaling, particularly the concept of biased signaling, is essential for unraveling the complex pharmacology of psychedelics and their impact on human cognition and perception. The concept of biased signaling at the 5-HT2A receptor provides a sophisticated framework for understanding the diverse effects of psychedelics on the human brain. By elucidating how different psychedelics preferentially engage specific signaling pathways, researchers can better predict their pharmacological outcomes, paving the way for more targeted and effective therapeutic applications. As research continues to uncover the intricate dynamics of 5-HT2A receptor signaling, the potential for psychedelics to revolutionize mental health treatment becomes increasingly promising.

7. Overview of novel biased 5-HT2A ligands

7.1. Ligands biased to G proteins and β-arrestins

Currently, only a few Gq- and β-arrestin-biased ligands have been identified (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Selected novel biased 5-HT2A ligands.

In 2022, Kaplan et al.63 reported the design and synthesis of two novel Gq-biased agonists. Subsequent structural optimization efforts resulted in the development of two potent 5-HT2A receptor agonists, i.e., (R)-69 and (R)-70 (Fig. 4A and B). These compounds exhibited EC50 of 41 and 110 nmol/L, respectively. Importantly, both agonists displayed biased signaling towards G-protein activation, showing high efficacy in activating Gq signaling at mid-nanomolar concentrations, while β-arrestin recruitment was only observed at higher concentrations. Notably, these new agonists exhibited high brain permeability and significant antidepressant activity in mouse models without inducing psychedelic effects, achieving comparable efficacy to fluoxetine at much lower doses88,121.

Figure 4.

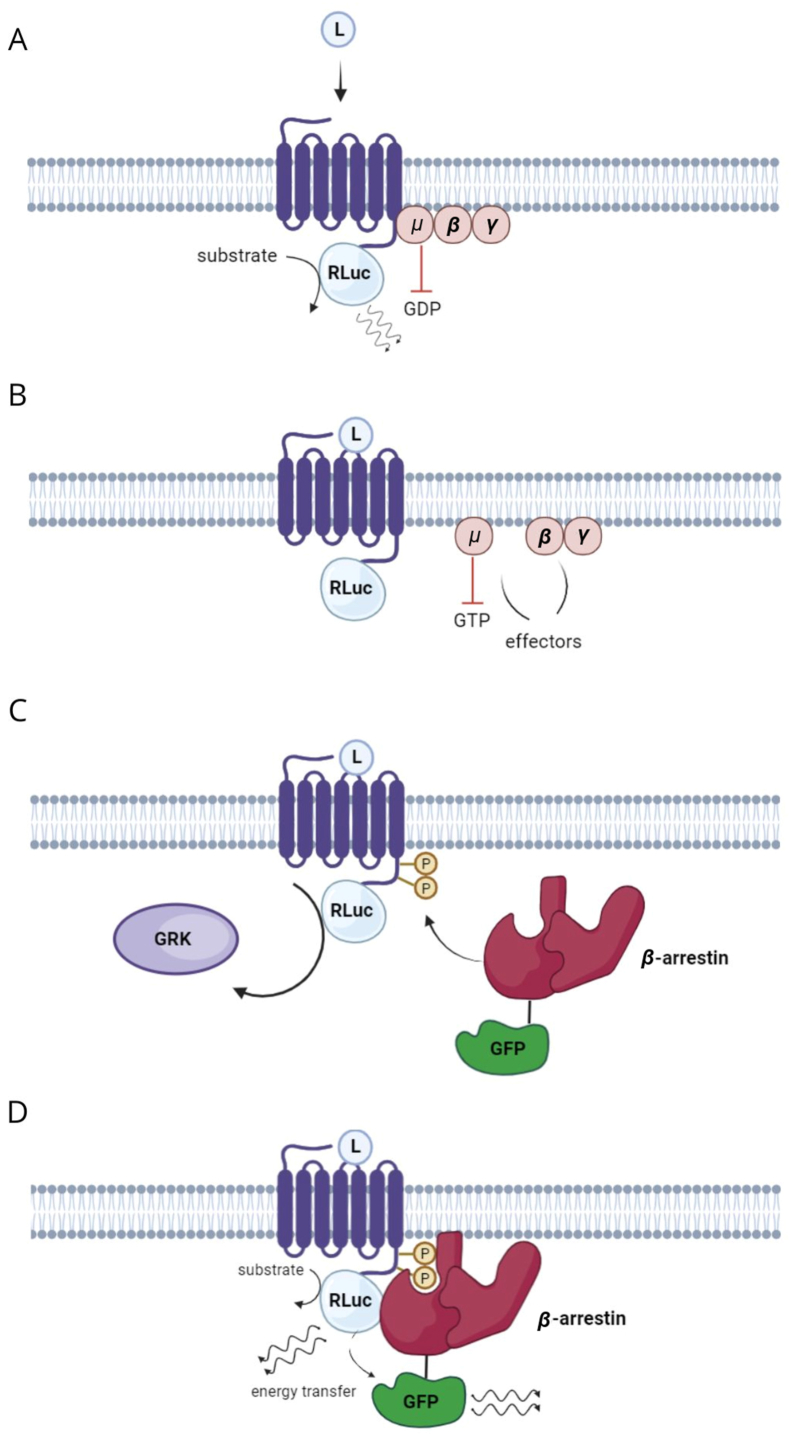

Principle of the BRET2/arrestin assay152. A, activation; B, desensitization; C, β-arrestin binding; D, energy transfer. The figure was created using BioRender.

More recently, a new class of small heterocyclic compounds has emerged as Gq-biased agonists targeting the 5-HT2A receptor (Fig. 4C). These compounds, structurally related to Kaplan's compounds, are particularly promising due to their selectivity. Unlike broad-spectrum agonists that interact with similar receptors such as 5-HT2B and 5-HT2C, these compounds selectively target the 5-HT2A receptor. Furthermore, they preferentially activate the Gq signaling pathway over the recruitment of β-arrestin. However, more thorough assessments are necessary to ascertain their therapeutic viability for clinical use88,121.

It is equally challenging to identify new ligands acting as biased towards β-arrestins, as to Gq-biased ligands. Selective 5-HT2AR agonists include indoloalkylamines and phenylalkylamines, particularly N-benzylphenethylamines. A highly selective phenylalkylamine analog is 25CN-NBOH (Fig. 4D), which has been tested for functional selectivity at 5-HT2A receptor and identified as the first effective β-arrestin 2-biased agonist. In the context of biased signaling at 5-HT2A receptor, interactions with Ser159ˆ3.36 are crucial for efficacy. The loss of this interaction significantly reduces potency and efficiency in β-arrestin 2 and miniGαq assays, with Gαq signaling being more noticeably affected16,122,123.

Based on the promising results obtained from the initial series of 25CN-NBOH derivatives, further investigation was conducted to determine whether Gq signaling could be reduced. This was explored by substituting the N-benzyl ring with more sterically demanding bi-aryl ring systems, such as N-naphthyl and N-biphenyl. Notably, compounds 25N-N1-Nap and 25N-NBPh exhibited a marked reduction in 5-HT2A-Gq efficacy at 5-HT2A receptor while maintaining β-arrestin 2 efficacy at the same receptor. This revealed a distinct biased agonism profile favoring β-arrestin over Gq signaling, in contrast to the balanced agonist 25CN-NBOMe. Interestingly, the β-arrestin-biased agonists were also observed to partially antagonize 5-HT2A-Gq activity16.

The exploration of biased 5-HT2A receptor agonists derived from phenylalkylamines has been significantly advanced by studies conducted by Pottie et al.124 This study evaluated structure–activity relationships and biased agonism in a diverse panel of phenylalkylamines, focusing on their ability to induce β-arrestin 2 or miniGαq recruitment to the 5-HT2A receptor. The compounds were assessed against established reference points, including LSD and serotonin. The mechanism of action of all studied compounds was closely linked to β-arrestin 2 and miniGαq recruitment in assays125. Interestingly, the lipophilicity of phenethylamines was found to be correlated with their increased agonist efficacies whereby the correlation was stronger with miniGαq than β-arrestin 2. Since these compounds only differ at position-4 of the phenethylamine, the moiety substitution might contribute to overall ligand lipophilicity and preferred efficacy. Additionally, the implementation of molecular docking suggested that 4-substituted group of phenethylamines occupies the hydrophobic pocket of 5-HT2A receptor between transmembrane helices 4 and 5 which could be the reason for this difference124,126.

The β-arrestin 2-biased 5-HT2A receptor agonists identified include phenethylamine compounds: 6.1, 6.2, 1.65, and 11.3 (Fig. 3E–H)125. In particular, compound 6.1 displayed potency and efficacy values equal to 11.1 nmol/L and 112%, respectively, for β-arrestin recruitment, and 48.8 nmol/L and 28% for miniGαq activation, when compared to LSD. The compound 11.3 displayed potency and efficacy values of 108 nmol/L and 82.9%, respectively, in the βarr2 assay, and 631 nmol/L and 18% for miniGαq recruitment.

7.2. Other selective ligands acting on 5-HT2A

Potent, selective biased agonists of the 5-HT2A receptor include the compounds MetI, MetT, and NitroI, identified by Martí-Solano et al70. Notably, NitroI acts as a full agonist for IP signaling at nanomolar concentrations while refraining from activating the AA pathway. This study provides a valuable framework for exploring specific signaling pathways related to 5-HT2A receptor activation. It is important to highlight that the compounds obtained are tryptamine derivatives. Unlike serotonin, methyltryptamine derivatives do not activate 5-HT2A receptors through the β-arrestin 2/Src/Akt signaling complex, suggesting a distinct mechanism of action. This distinction underscores the necessity for further research to explore the mechanisms underlying the activity of tryptamine derivatives127.

Wallach et al.16 also proposed the compound 25N-NBI, which demonstrated 23-fold selectivity for 5-HT2AR over 5-HT2CR, as confirmed in three independent functional assays, indicating its higher selectivity compared to 25CN-NBOH. Additionally, 25N-NBI exhibited selectivity for 5-HT2AR over 5-HT2BR and 5-HT2CR in competitive binding studies. Finally, 25N-NBI induced HTR in mice, confirming the psychedelic potential of selective 5-HT2AR agonists. Interestingly, 25N-NBI did not show a preference for either 5-HT2AR-Gq or 5-HT2AR-β-arrestin 2 activity.

The compounds described in Section 7 are summarized in Table 216,63,70,88,123,125,128.

Table 2.

Overview of 5-HT2A biased ligands.

| Compd. | Pharmacological properties | Receptor selectivity | Primary clinical/research use | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (R)-69 | Gq-biased (EC50 = 41 nmol/L) | 5-HT2A (Ki = 680 nmol/L) | Antidepressant-like effects in mice | 63 |

| (R)-70 | Gq-biased (EC50 = 110 nmol/L) | 5-HT2A (Ki = 880 nmol/L) | Antidepressant-like effects in mice | 63 |

| Kargbo's compounds | Gq-biased | 5-HT2A | Possible application in neuropsychiatric treatment (need to further research) | 88 |

| 25CN-NBOH | β-Arrestin 2-biased (EC50 = 2.75 nmol/L) | 5-HT2A (Ki = 1.7 nmol/L) | Research tool for biased signaling | 123,128 |

| 25N-N1-Nap | β-Arrestin-biased | 5-HT2A | 16 | |

| 25N-NBPh | β-Arrestin 2-biased | 5-HT2A | Functional bias studies | 16 |

| 25N-NBI | Balanced activity (Gq and β-arrestin 2) | 5-HT2A | Psychedelic research | 16 |

| 6.1, 6.2, 1.65, 11.3 | β-Arrestin 2-biased | 5-HT2A | 125 | |

| MetI, MetT, NitroI | IP signaling agonist | 5-HT2A | Research compound | 70 |

8. In vitro assays to study biased signaling of 5-HT2A receptor

Measuring selectivity in the context of biased signaling is a methodological challenge. Numerous methods aimed at capturing receptor distribution, receptor activation, or changes in receptor structure during ligand docking have been extensively described by Pottie and Stove129. This text provides a brief overview of the most common methods.

The first category of techniques used to determine receptor distribution within the studied tissue includes radioligand-based approaches. Among these, the most commonly used radioactive antagonists are [3H]-spiperone, [3H]-ketanserin, and [3H]-MDL100,907, with the latter exhibiting the highest selectivity for the 5-HT2A receptor130,131. It is also worth noting that radioligands have found applications in binding assays, where agonists such as [3H]-5-HT, [3H]-LSD, [3H]-DOB, [125I]-DOI, [125I]-2C-I, [125I]-2I-LSD and [3H]-INBMeO, which show higher selectivity towards 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C, are more frequently employed81,132.

The second category of methods used to determine receptor activation includes techniques such as the [35S]GTPγS binding assay, which allows for the detection of the early stages of GDP exchange for the non-hydrolyzable GTP analog [35S]GTPγS in G proteins133,134. Other methods include receptor internalization assays using confocal microscopy or flow cytometry, second messenger assays (such as cAMP, DAG, IP-3, or IP-1 assays), and calcium mobilization assays135.

The third type of method depicts changes within the receptor or the overall cellular response and includes techniques like real-time live-cell biosensors, such as dynamic mass redistribution (DMR) and electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS)136, 137, 138, 139. Although these methods provide substantial information—given that conformational changes of the receptor caused by ligand binding determine affinity coupling to transducer proteins—they have only indirect relevance in the context of biased signaling48,140. More specific information about intracellular signaling pathways can be provided by other techniques. Below are several examples of these techniques and how they are applied in the context of GPCRs.

The earliest method for specific detection of pathways activated as a result of antagonist binding to the GPCR, such as 5-HT2A, was immunoblotting (Western blotting)141. This technique allows the detection of not only receptor phosphorylation, which can indicate specific substance actions, as shown in the example of Ser280 phosphorylation67 but also downstream signaling molecules using specific antibodies142,143. A related technique, ELISA, based on the same antigen–antibody interaction principle, may be a better choice for broader studies. In proteomics and phosphoproteomic studies, mass spectrometry has become a useful and powerful technology73. Unlike Western blotting, which is a semi-quantitative method, mass spectrometry provides both a qualitative assessment and precise quantification of phosphorylated proteins, including the number of phosphorylation sites67.

Reporter gene assays are widely used to identify and measure the activation levels of specific signaling pathways. These assays utilize promoter elements responsive to specific signaling pathways, downstream responses, and reporter genes placed upstream. Currently, several types of reporter genes are commonly used, among which the most commonly used in cell biology are fluorescent proteins, secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP), and luciferases. While the first are convenient as pathway activity changes can be observed in real-time under a fluorescent or confocal microscope without cell lysis, enzymatic methods or luciferases provide a more accurate picture of cellular responses. Particularly convenient and precise for determining pathway activity are reporters secreted outside the cell, such as SEAP or Gaussia Luciferase. In studies on 5-HT2A activation, elements like the Fos promoter (c-Fos), SRE promoter (serum response element) and NFAT promoter (nuclear factor of activated T-cells) have been previously used144,145.

Due to the dynamic interactions between these proteins and the activated receptor, several techniques have been developed to measure protein–protein interactions. One such method is the PRESTO-TANGO system146. This system consists of three elements: two fusion proteins and a reporter system. The first fusion protein comprises the receptor under study fused to a transcription activator (tTA). A sequence recognized by the TEV protease (tobacco etch virus protease) is situated between the receptor and tTA. The second element of the system involves the TEV protease, which, along with β-arrestin, co-creates a functional component. Upon receptor activation, the β-arrestin-TEV element is recruited, leading to the release of tTA. Subsequently, tTA is transported to the cell nucleus, where it binds to a reporter sequence consisting of a reporter gene encoding a fluorescent protein or luciferase. This gene is preceded by tTA recognition sites, activating transcription of a reporter that can be readily measured.

Another method, BRET, employs the transfer of light energy emitted by a donor protein, such as luciferase, to an acceptor, like a fluorescent protein (Fig. 4). This allows for the observation of the acceptor's fluorescence, but only when luciferase and the fluorescent protein are in close proximity (∼115 Å) and in the presence of a substrate for luciferase. This approach has been utilized to study 5-HT2A–β-arrestin 2 and 5-HT2A–Gq activity directly147 confirming 5-HT2A–G protein coupling preferences148 and even identifying a broader list of effectors16,71,74. Building on the BRET phenomenon, many innovative platforms for studying GPCR activity have been developed, including TRUPATH and ONE-GO149, 150, 151.

TRUPATH, the first of these platforms, utilizes BRET2, an enhanced BRET system with increased resolution (∼45–55 nm). It incorporates NanoLuc luciferase (NLuc) fused to Gα and a fluorescent protein, GFP2, fused to Gβγ149,152. This extensive structure allows it to cover as many as 14 G protein pathways. Conversely, the ONE-GO platform enables the detection of active Gαs by employing peptides specifically designed to recognize Gαs–GTP. These peptides, combined with NLuc luciferase as BRET donors, use yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) as the acceptor. This system encompasses four families of G proteins150.

Another technique based on the same phenomenon of energy transfer, fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) (Fig. 5), has also been utilized to detect interactions between proteins involved in signal transduction153. Both methods, FRET and BRET, have been used for capturing ligand–receptor interaction and are compatible with downstream signaling measurements listed above 154.

Figure 5.

TR-FRET assay. The figure was created using BioRender.

Lin Tian's research group155 demonstrated an innovative approach by building on their previous work to develop a recombinant form of the 5-HT2A receptor, known as psychLight. This sensor is specifically designed to detect the hallucinogenic potential of compounds, making it valuable for studying this phenomenon in vitro and in vivo. The psychLight system functions by causing cells to emit green fluorescence when exposed to compounds with hallucinogenic properties. This fluorescence facilitates easy signal detection and enables the implementation of the system in high-throughput screening of various substances116.

Additionally, deliberate modifications of individual elements within the signaling network can be instrumental in determining their specific functions. Techniques commonly employed to remove a particular protein or reduce its expression include methods based on CRISPR/Cas9 technology and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs)17,156.

Each of the aforementioned techniques offers a wealth of information about the functioning of GPCRs, including the 5-HT2A receptor. However, it is only through the combination of several of these techniques that a comprehensive understanding of the changes occurring in the cell during ligand binding and intracellular signal transduction can be achieved.

9. Behavioral studies of 5-HT2A biased ligands

Activation of the 5-HT2A receptor modulates distinct behavioral processes across neuropsychiatric conditions. In animal models, activation of the 5-HT2A receptor engages multiple signaling pathways. Notably, Gq protein activation has been implicated in modulating memory deficits71 and is essential for the antidepressant-like effects of 5-HT2A receptor ligands81. While β-arrestin recruitment could be insufficient to produce these therapeutic outcomes, ligands biased toward β-arrestin with minimal G protein signaling can offer antidepressant benefits without inducing hallucinations19. Both Gq- and Gi/o-dependent pathways have been implicated in the psychosis-related and hallucinogenic effects observed in rodent models16,18,71,157. In addition, several investigations describe signaling crosstalk involving β-arrestin-2 and downstream effectors such as phospholipase C and extracellular signal-regulated kinase19,38,81. These interacting pathways further modulate anxiety-like behaviors and fear extinction18,158.

Behavioral tests like the HTR, FST (Forced Swim Test), TST (Tail Suspension Test), and DDT are valuable in evaluating the effects of psychedelics on behavior and mood. In the HTR, after drug is administered, the animal's head movements are measured. It is often used as an indicator of serotonergic activity and is notably elicited by compounds such as LSD and psilocybin, reflecting activation of 5-HT2A receptors159. An increase in head twitches indicates activation of these receptors, often related to hallucinogenic or psychoactive effects.

In FST and TST, both of which measure despair-like behavior in rodents, psychedelics like psilocybin have demonstrated potential antidepressant effects by reducing immobility time, suggesting mood-enhancing properties likely mediated by serotonin and other neuroplastic changes (Fig. 6)160. The FST and TST assess depressive-like behavior by measuring the amount of time the mouse remains immobile. Prolonged immobility in both tests suggests learned helplessness or depression, while decreased immobility time is interpreted as a positive response to antidepressants.

Figure 6.

Forced swim test (FST) and tail suspension test (TST). The figure was created using BioRender.

In DDT, mice are trained to associate a specific drug with a particular behavioral response, such as lever pressing. The ability to correctly identify the drug state indicates the mouse's perception of the drug's effects. DDT is employed to assess the subjective effects of psychedelics, as animals can be trained to distinguish between the drug and placebo based on sensory or motor cues, offering insight into the reinforcing properties and specific receptor interactions of substances like DMT and MDMA120,161.

It has been found that lisuride, IHCH-7079, and IHCH-7086 significantly reduced freezing behavior induced by acute restraint stress (ARS), which triggers depression-like behavior, as assessed using FST and TST in rodents. This effect was 5-HT2A receptor-dependent. In addition, LSD, IHCH-7079, and IHCH-7086 reduced an increase in immobility in mice induced by corticosterone chronic administration (three weeks of treatment), and the 5-HT2A receptor was also involved in this activity19,82.

Similarly, phenethylamine-based compounds with high selectivity for the 5-HT2A receptor have been studied for their psychedelic potential. While some of these compounds, such as 25N-N1-Nap and 25N-NBPh, fail to induce the HTR due to their β-arrestin 2 bias, others, like 25O-N1-Nap, exhibit weak Gq efficacy but effectively block the HTR induced by DOI, further illustrating the complexity of 5-HT2A receptor signaling16. DOI-induced HTR was attenuated in Gq knock-out mice while was observed in β-arrestin 2 knockout mice38 (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Effects induced by Gq/i and β-arrestin 2-mediated 5-HT2A receptor activation.

10. Conclusions and perspectives

GPCRs, including serotonin 5-HT2A receptor, are key drug targets for treating mental diseases, in particular schizophrenia, depression, and anxiety. Taking into consideration biased signaling via this receptor, novel more effective and safer drugs can be developed. It can be facilitated by structural biology (X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM microscopy) and computer-assisted approaches, in particular advanced molecular dynamics techniques which uncovered subtle aspects of biased ligands–receptor interactions at the molecular level.

The therapeutic potential of biased 5-HT2A receptor ligands is not only conceptual. Compounds, such as 25CN-NBOH, are biased 5-HT2A receptor ligands able to achieve therapeutic effects without inducing hallucinogenic experience which are typically connected with this receptor stimulation. Next, the clinical efficacy of pimavanserin, a drug with antipsychotic properties and no dopamine D2 receptor affinity but a unique biased signaling profile via 5-HT2A receptor stresses the potential of biased signaling to revolutionize the safety and effectiveness in the field of antipsychotics.

Despite significant progress in the field, there are still key challenges in the design and optimization of biased ligands. Importantly, novel more advanced predictive models to accurately predict ligand bias profiles should be developed. This can be achieved by a combination of advanced high-throughput screening technologies with machine learning approaches.

To translate laboratory findings into clinical practice, novel compounds need first a robust in vivo validation. Behavioral models such as HTR, STR, and DDT as well as new imaging technologies and molecular analyses are valuable tools to further assess a link between the biased signaling profile and behavioral outcome. In addition, clarification of the molecular mechanisms underlying therapeutic versus hallucinogenic effects is necessary for the development of safer, more selective therapies. By identifying the specific conformational states and signaling pathways engaged, ligands with maximal therapeutic effects and minimal side effects can be developed.

The importance of 5-HT2A receptor-biased signaling goes beyond psychiatry. There is increasing evidence that it may be involved in neurodegenerative diseases, pain, and immunomodulation. With increasing clinical translation, stringent regulatory rules will have to be developed that will ascertain the efficacy as well as safety of these new drugs. Their novel drug pharmacological profiles, enabling targeted treatment with reduced side effects, can open the way for new paradigms of therapy, such as optimized regimens of dosing and tailored medicine strategies.

Finally, expanding our understanding of biased signaling on the 5-HT2A receptor is more than incremental progress: it's a paradigm shift in GPCR-targeted therapy. By weighing the desire to maximize therapeutic effect against minimizing risks, this paradigm has vast potential to revolutionize treatment for psychiatric illness and a wide variety of other complex medical illnesses.

Author contributions

Michał K. Jastrzębski wrote and revised the manuscript, prepared the figures; Piotr Wójcik wrote the manuscript (Section 2); Angelika Grudzińska wrote the manuscript (Section 5); Giorgia Andreozzi wrote the manuscript (Section 5); Tommaso Vetrò wrote the manuscript (Section 7); Ayesha Asim wrote the manuscript (Section 4); Akanksha Mudgal wrote the manuscript (Section 9); Jakub Czapiński wrote the manuscript (Section 8); Tomasz M. Wróbel wrote the manuscript (Section 6) and revised the manuscript; Damian Bartuzi wrote the manuscript (Section 3); Katarzyna M. Targowska-Duda wrote the manuscript (Section 9) and revised the manuscript; Agnieszka A. Kaczor wrote the manuscript (Section 10) and critically revised the manuscript.

Declaration of generative AI in scientific writing

The GPT chat (OpenAI GPT 4.0) was used to check the language's correctness. The authors bear all responsibility for the substantive value of the text and for linguistic errors in the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by a statutory funds grant from the Medical University of Lublin, Poland (grant number DS33), to Agnieszka A. Kaczor.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Contributor Information

Michał K. Jastrzębski, Email: michal.jastrz1998@gmail.com.

Agnieszka A. Kaczor, Email: agnieszka.kaczor@umlub.pl.

References

- 1.Hauser A.S., Attwood M.M., Rask-Andersen M., Schiöth H.B., Gloriam D.E. Trends in GPCR drug discovery: new agents, targets and indications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:829–842. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevens R.C., Cherezov V., Katritch V., Abagyan R., Kuhn P., Rosen H., et al. The GPCR Network: a large-scale collaboration to determine human GPCR structure and function. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:25–34. doi: 10.1038/nrd3859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tautermann C.S. GPCR structures in drug design, emerging opportunities with new structures. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014;24:4073–4079. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobson K.A. New paradigms in GPCR drug discovery. Biochem Pharmacol. 2015;98:541–555. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.08.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray-Keller M.P., Detwiler P.B., Benovic J.L., Gurevich V.V. Arrestin with a single amino acid substitution quenches light-activated rhodopsin in a phosphorylation-independent fashion. Biochemistry. 1997;36:7058–7063. doi: 10.1021/bi963110k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marion S., Oakley R.H., Kim K.M., Caron M.G., Barak L.S. A beta-arrestin binding determinant common to the second intracellular loops of rhodopsin family G protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2932–2938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508074200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bombardi C., Di Giovanni G. Functional anatomy of 5-HT2A receptors in the amygdala and hippocampal complex: relevance to memory functions. Exp Brain Res. 2013;230:427–439. doi: 10.1007/s00221-013-3512-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu T., Pandey S.C. Cellular localization of serotonin(2A) (5HT(2A)) receptors in the rat brain. Brain Res Bull. 2000;51:499–505. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(99)00278-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang G., Stackman R.W. The role of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors in memory and cognition. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:225. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aghajanian G.K., Marek G.J. Serotonin, via 5-HT2A receptors, increases EPSCs in layer V pyramidal cells of prefrontal cortex by an asynchronous mode of glutamate release. Brain Res. 1999;825:161–171. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang X., Xing G., Yang C., Verma A., Zhang L., Li H. Stress impairs 5-HT2A receptor-mediated serotonergic facilitation of GABA release in juvenile rat basolateral amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:410–423. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickson E.J., Falkenburger B.H., Hille B. Quantitative properties and receptor reserve of the IP(3) and calcium branch of G(q)-coupled receptor signaling. J Gen Physiol. 2013;141:521–535. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith J.S., Rajagopal S. The β-Arrestins: multifunctional regulators of G protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:8969–8977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.713313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhatnagar A., Willins D.L., Gray J.A., Woods J., Benovic J.L., Roth B.L. The dynamin-dependent, arrestin-independent internalization of 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A (5-HT2A) serotonin receptors reveals differential sorting of arrestins and 5-HT2A receptors during endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8269–8277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez-Reyes O.B., Zilberg G., McCorvy J.D., Wacker D. Molecular insights into GPCR mechanisms for drugs of abuse. J Biol Chem. 2023;299 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.105176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallach J., Cao A.B., Calkins M.M., Heim A.J., Lanham J.K., Bonniwell E.M., et al. Identification of 5-HT2A receptor signaling pathways associated with psychedelic potential. Nat Commun. 2023;14:8221. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-44016-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguiz R.M., Nadkarni V., Means C.R., Pogorelov V.M., Chiu Y.T., Roth B.L., et al. LSD-stimulated behaviors in mice require β-arrestin 2 but not β-arrestin 1. Sci Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-96736-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia E.E., Smith R.L., Sanders-Bush E. Role of G(q) protein in behavioral effects of the hallucinogenic drug 1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl)-2-aminopropane. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:1671–1677. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao D., Yu J., Wang H., Luo Z., Liu X., He L., et al. Structure-based discovery of nonhallucinogenic psychedelic analogs. Science. 2022;375:403–411. doi: 10.1126/science.abl8615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wettschureck N., Moers A., Hamalainen T., Lemberger T., Schütz G., Offermanns S. Heterotrimeric G proteins of the Gq/11 family are crucial for the induction of maternal behavior in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8048–8054. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8048-8054.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berridge M.J. Inositol trisphosphate and diacylglycerol: two interacting second messengers. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:159–193. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosel P., Arranz B., San L., Urretavizcaya M., Marcusson J., Navarro M.A. 5-HT2A receptors and their second messenger IP3 are only correlated in human brain and not in platelets. Neurosci Res Commun. 1999;25:129–138. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hagberg G.B., Blomstrand F., Nilsson M., Tamir H., Hansson E. Stimulation of 5-HT2A receptors on astrocytes in primary culture opens voltage-independent Ca2+ channels. Neurochem Int. 1998;32:153–162. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(97)00087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Putney J.W., Bird G.S. Calcium mobilization by inositol phosphates and other intracellular messengers. Trends Endocrinol Metabol. 1994;5:256–260. doi: 10.1016/1043-2760(94)p3085-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raote I., Bhattacharya A., Panicker M.M. In: Serotonin receptors in neurobiology. Chattopadhyay A., editor. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; Boca Raton (FL): 2007. Serotonin 2A (5-HT2A) receptor function: ligand-dependent mechanisms and pathways. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dai Y. Loyola University Chicago; Chicago: 2009. Regulation of transglutaminase by 5-HT2A receptor signaling and calmodulin[Dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morotomi-Yano K., Yano K.I. Calcium-dependent activation of transglutaminase 2 by nanosecond pulsed electric fields. FEBS Open Bio. 2017;7:934–943. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dai Y., Dudek N.L., Patel T.B., Muma N.A. Transglutaminase-catalyzed transamidation: a novel mechanism for Rac1 activation by 5-hydroxytryptamine2A receptor stimulation. J Pharmacol Exp Therapeut. 2008;326:153–162. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.135046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurrasch-Orbaugh D.M., Parrish J.C., Watts V.J., Nichols D.E. A complex signaling cascade links the serotonin2A receptor to phospholipase A2 activation: the involvement of MAP kinases. J Neurochem. 2003;86:980–991. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barclay Z., Dickson L., Robertson D.N., Johnson M.S., Holland P.J., Rosie R., et al. 5-HT2A receptor signalling through phospholipase D1 associated with its C-terminal tail. Biochem J. 2011;436:651–660. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang X., Edwards E.M., Holmes B.B., Falck J.R., Campbell W.B. Role of phospholipase C and diacylglyceride lipase pathway in arachidonic acid release and acetylcholine-induced vascular relaxation in rabbit aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H37–H45. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00491.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cas M.D., Roda G., Li F., Secundo F. Functional lipids in autoimmune inflammatory diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:3074. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.López-Giménez J.F., González-Maeso J. Hallucinogens and serotonin 5-HT2A receptor-mediated signaling pathways. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2018;36:45–73. doi: 10.1007/7854_2017_478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roth B.L., Allen J.A., Yadav P.N. Insights into the regulation of 5-HT2A receptors by scaffolding proteins and kinases. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:961–968. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gray J.A., Bhatnagar A., Gurevich V.V., Roth B.L. The interaction of a constitutively active arrestin with the arrestin-insensitive 5-HT(2A) receptor induces agonist-independent internalization. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:961–972. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.5.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luttrell L.M., Roudabush F.L., Choy E.W., Miller W.E., Field M.E., Pierce K.L., et al. Activation and targeting of extracellular signal-regulated kinases by beta-arrestin scaffolds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2449–2454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041604898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeFea K.A., Vaughn Z.D., O'Bryan E.M., Nishijima D., Déry O., Bunnett N.W. The proliferative and antiapoptotic effects of substance P are facilitated by formation of a beta-arrestin-dependent scaffolding complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11086–11091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190276697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmid C.L., Raehal K.M., Bohn L.M. Agonist-directed signaling of the serotonin 2A receptor depends on beta-arrestin-2 interactions in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1079–1084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708862105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bohn L.M., Schmid C.L. Serotonin receptor signaling and regulation via β-arrestins. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;45:555–566. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2010.516741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Charest P.G., Bouvier M. Palmitoylation of the V2 vasopressin receptor carboxyl tail enhances beta-arrestin recruitment leading to efficient receptor endocytosis and ERK1/2 activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41541–41551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306589200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaizuka T., Hayashi T. Comparative analysis of palmitoylation sites of serotonin (5-HT) receptors in vertebrates. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2018;38:75–85. doi: 10.1002/npr2.12011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]