Abstract

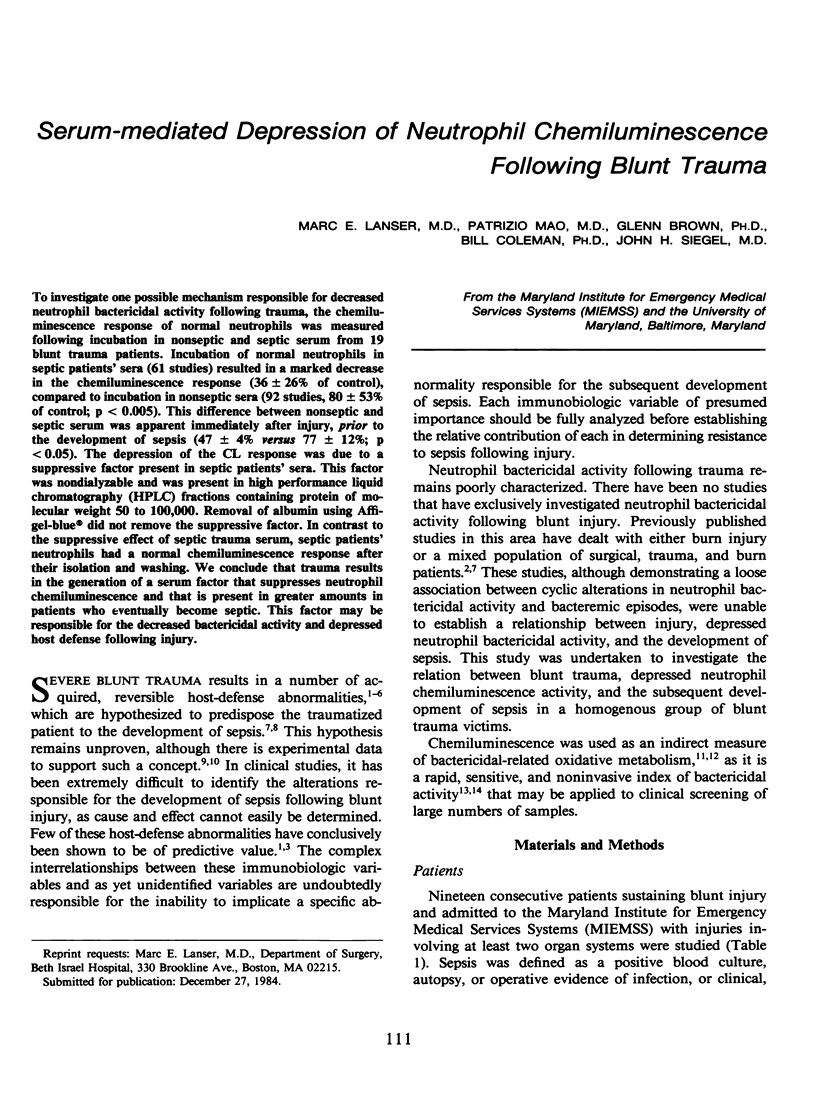

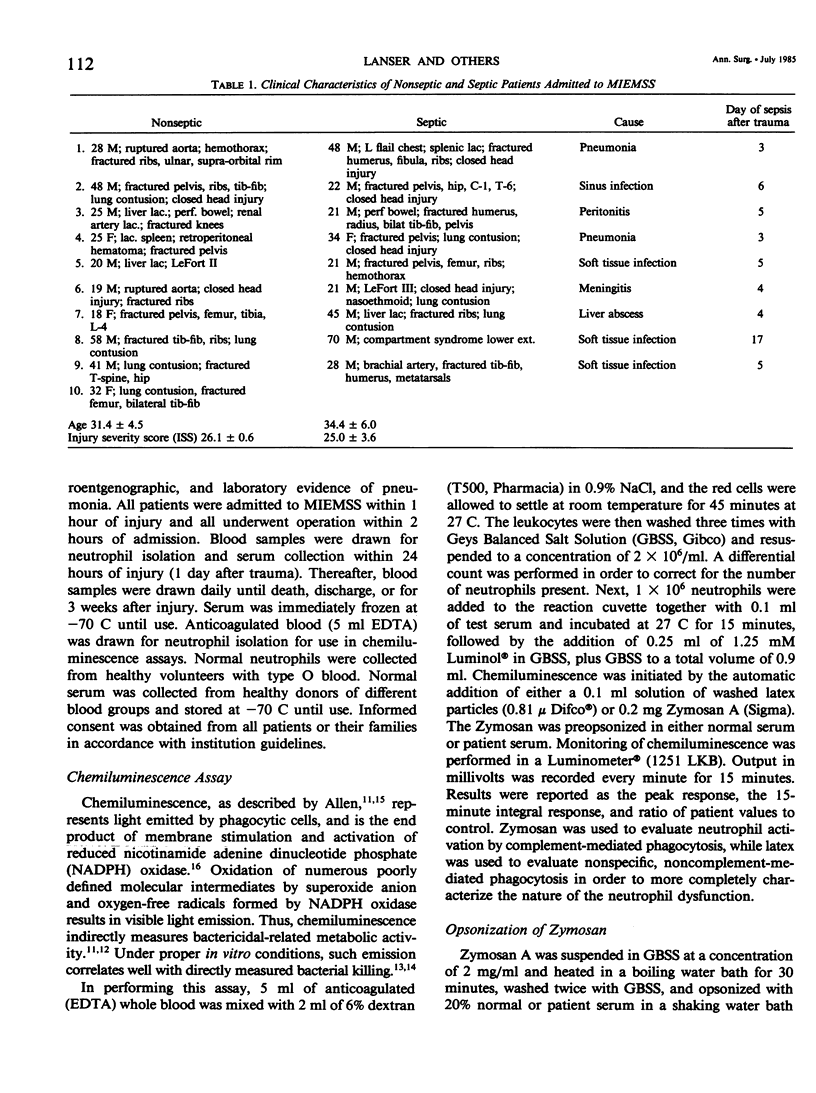

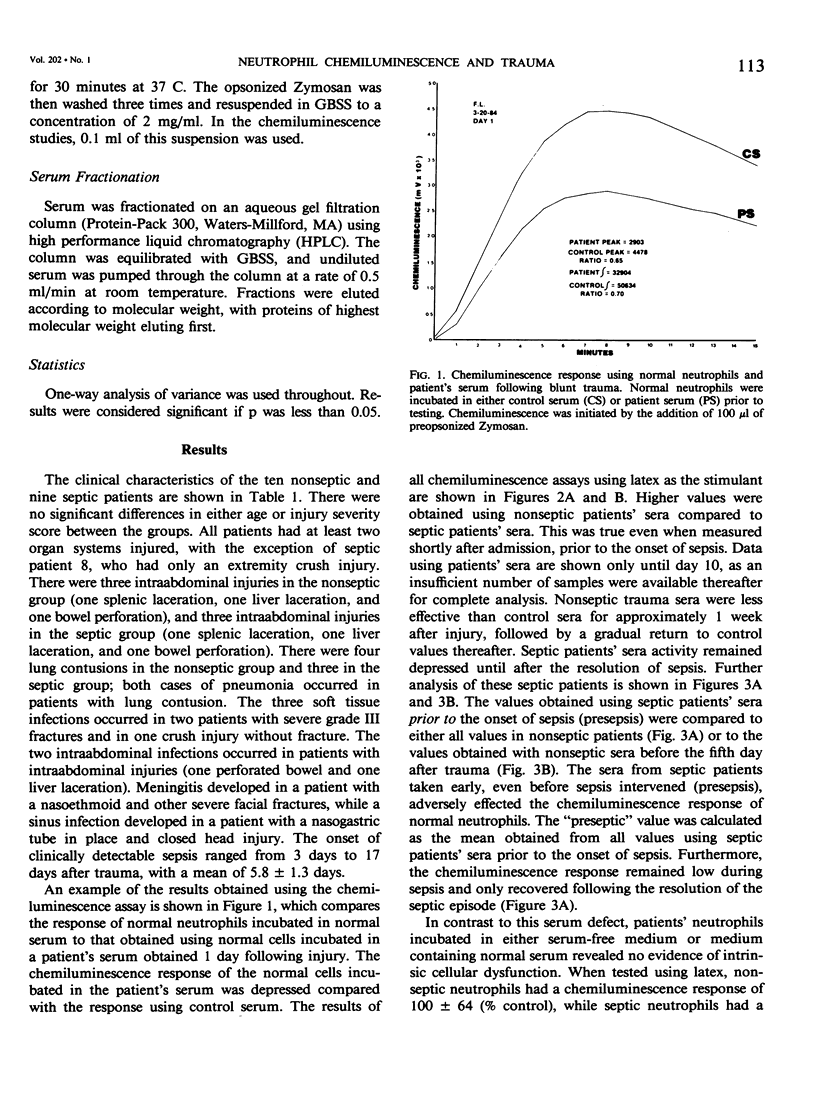

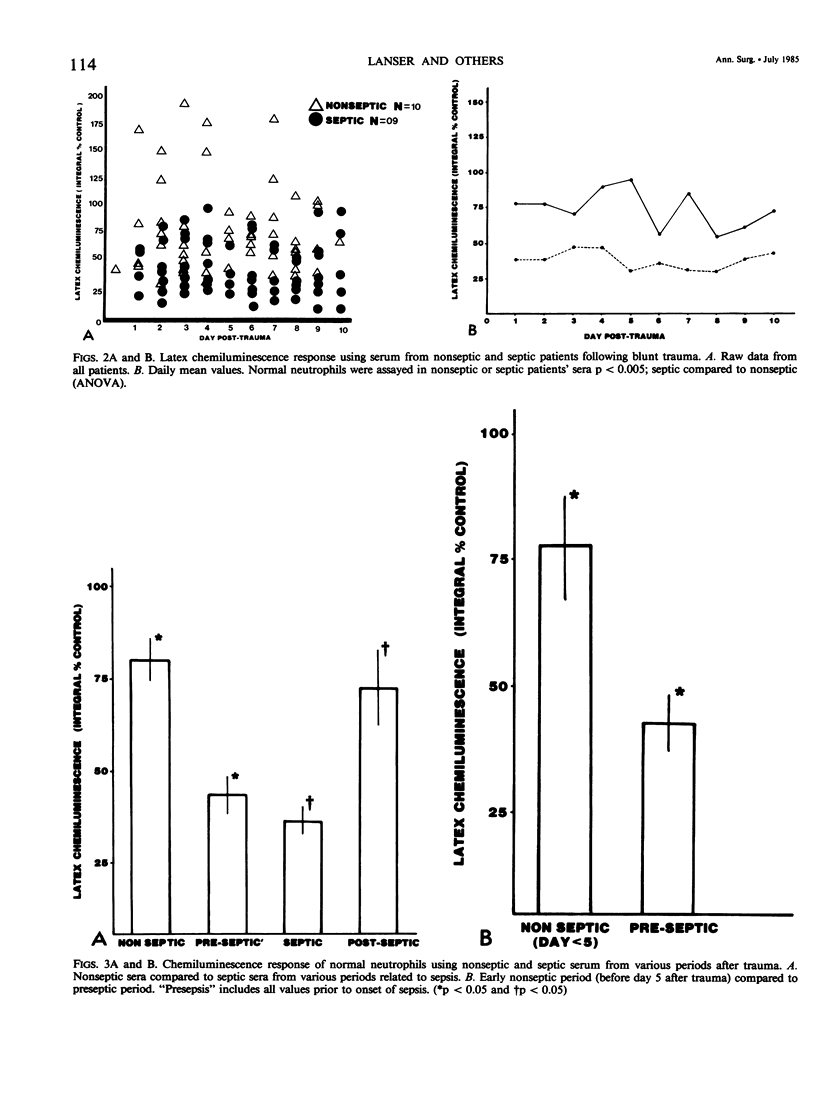

To investigate one possible mechanism responsible for decreased neutrophil bactericidal activity following trauma, the chemiluminescence response of normal neutrophils was measured following incubation in nonseptic and septic serum from 19 blunt trauma patients. Incubation of normal neutrophils in septic patients' sera (61 studies) resulted in a marked decrease in the chemiluminescence response (36 +/- 26% of control), compared to incubation in nonseptic sera (92 studies, 80 +/- 53% of control; p less than 0.005). This difference between nonseptic and septic serum was apparent immediately after injury, prior to the development of sepsis (47 +/- 4% versus 77 +/- 12%; p less than 0.05). The depression of the CL response was due to a suppressive factor present in septic patients' sera. This factor was nondialyzable and was present in high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) fractions containing protein of molecular weight 50 to 100,000. Removal of albumin using Affigel-blue did not remove the suppressive factor. In contrast to the suppressive effect of septic trauma serum, septic patients' neutrophils had a normal chemiluminescence response after their isolation and washing. We conclude that trauma results in the generation of a serum factor that suppresses neutrophil chemiluminescence and that is present in greater amounts in patients who eventually become septic. This factor may be responsible for the decreased bactericidal activity and depressed host defense following injury.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alexander J. W., Hegg M., Altemeier W. A. Neutrophil function in selected surgical disorders. Ann Surg. 1968 Sep;168(3):447–458. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196809000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander J. W., Meakins J. L. A physiological basis for the development of opportunistic infections in man. Ann Surg. 1972 Sep;176(3):273–287. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197209000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen R. C., Loose L. D. Phagocytic activation of a luminol-dependent chemiluminescence in rabbit alveolar and peritoneal macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976 Mar 8;69(1):245–252. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(76)80299-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen R. C., Stjernholm R. L., Steele R. H. Evidence for the generation of an electronic excitation state(s) in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes and its participation in bactericidal activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1972 May 26;47(4):679–684. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(72)90545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar R., Schirmer R., Ernst M., Decker K. Superoxide release by zymosan-stimulated rat Kupffer cells in vitro. Eur J Biochem. 1981 Sep;119(1):171–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb05590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornson A. B., Altemeier W. A., Bjornson H. S. Host defense against opportunist microorganisms following trauma. II. Changes in complement and immunoglobulins in patients with abdominal trauma and in septic patients without trauma. Ann Surg. 1978 Jul;188(1):102–108. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197807000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung K., Archibald A. C., Robinson M. F. The origin of chemiluminescence produced by neutrophils stimulated by opsonized zymosan. J Immunol. 1983 May;130(5):2324–2329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conolly W. B., Hunt T. K., Sonne M., Dunphy J. E. Influence of distant trauma on local wound infection. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1969 Apr;128(4):713–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahinden C. A., Fehr J., Hugli T. E. Role of cell surface contact in the kinetics of superoxide production by granulocytes. J Clin Invest. 1983 Jul;72(1):113–121. doi: 10.1172/JCI110948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeChatelet L. R., Shirley P. S. Chemiluminescence of human neutrophils induced by soluble stimuli: effect of divalent cations. Infect Immun. 1982 Jan;35(1):206–212. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.1.206-212.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esrig B. C., Frazee L., Stephenson S. F., Polk H. C., Jr, Fulton R. L., Jones C. E. The predisposition to infection following hemorrhagic shock. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1977 Jun;144(6):915–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewetz L., Palmblad J., Thore A. The relationship between luminol chemiluminescence and killing of staphylococcus aureus by neutrophil granulocytes. Blut. 1981 Dec;43(6):373–381. doi: 10.1007/BF00320316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heggers J. P., Loy G. L., Robson M. C., Del Beccaro E. J. Histological demonstration of prostaglandins and thromboxanes in burned tissue. J Surg Res. 1980 Feb;28(2):110–117. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(80)90153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan T. D., English D., McPherson T. A. Association of neutrophil chemiluminescence with microbicidal activity. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1982 Feb;22(2):259–269. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(82)90042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan J. E., Saba T. M. Humoral deficiency and reticuloendothelial depression after traumatic shock. Am J Physiol. 1976 Jan;230(1):7–14. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.230.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean L. D., Meakins J. L., Taguchi K., Duignan J. P., Dhillon K. S., Gordon J. Host resistance in sepsis and trauma. Ann Surg. 1975 Sep;182(3):207–217. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197509000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maderazo E. G., Albano S. D., Woronick C. L., Drezner A. D., Quercia R. Polymorphonuclear leukocyte migration abnormalities and their significance in seriously traumatized patients. Ann Surg. 1983 Dec;198(6):736–742. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198312000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R. D., Herron M. J., Schmidtke J. R., Simmons R. L. Chemiluminescence response of human leukocytes: influence of medium components on light production. Infect Immun. 1977 Sep;17(3):513–520. doi: 10.1128/iai.17.3.513-520.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninnemann J. L., Stockland A. E. Participation of prostaglandin E in immunosuppression following thermal injury. J Trauma. 1984 Mar;24(3):201–207. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198403000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor R. A. Endotoxin in vitro interactions with human neutrophils: depression of chemiluminescence, oxygen consumption, superoxide production, and killing. Infect Immun. 1979 Sep;25(3):912–921. doi: 10.1128/iai.25.3.912-921.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimpff S. C., Miller R. M., Polkavetz S., Hornick R. B. Infection in the severely traumatized patient. Ann Surg. 1974 Mar;179(3):352–357. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197403000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B. S., Heacock E. H., Mannick J. A. Characterization of suppressor cells generated in mice after surgical trauma. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1982 Aug;24(2):161–170. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(82)90227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]