Abstract

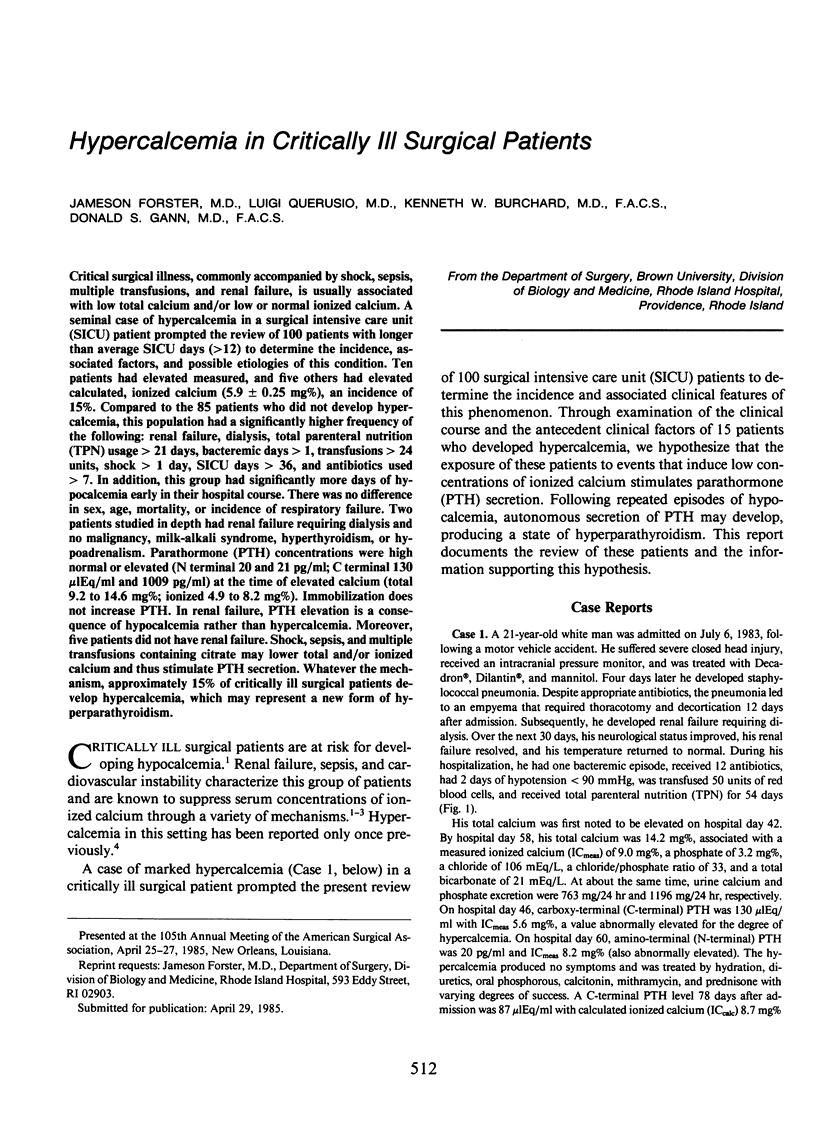

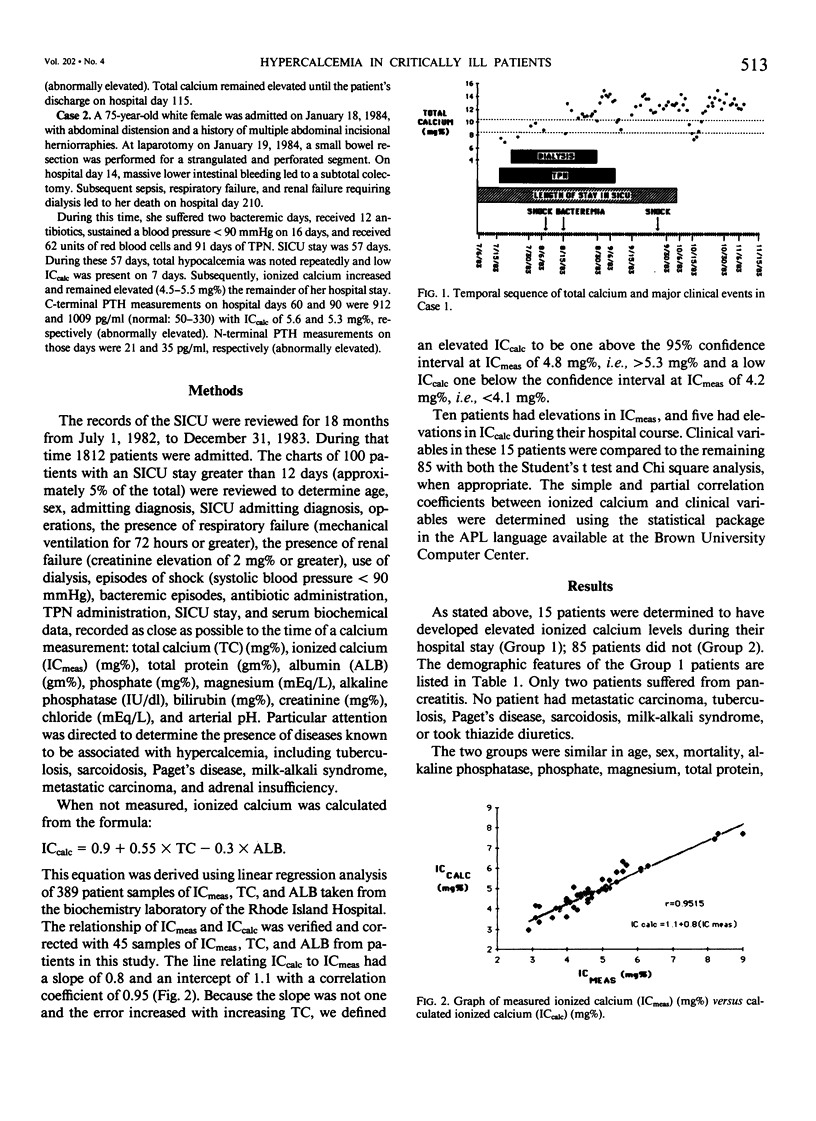

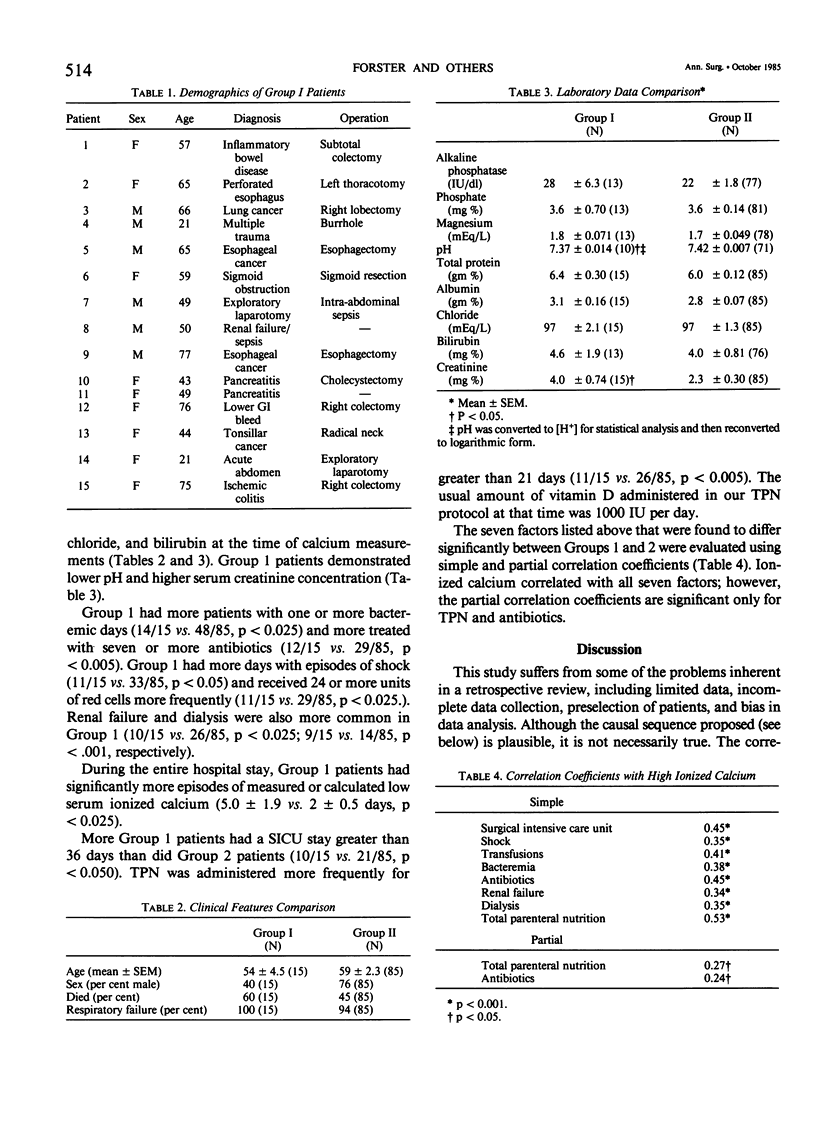

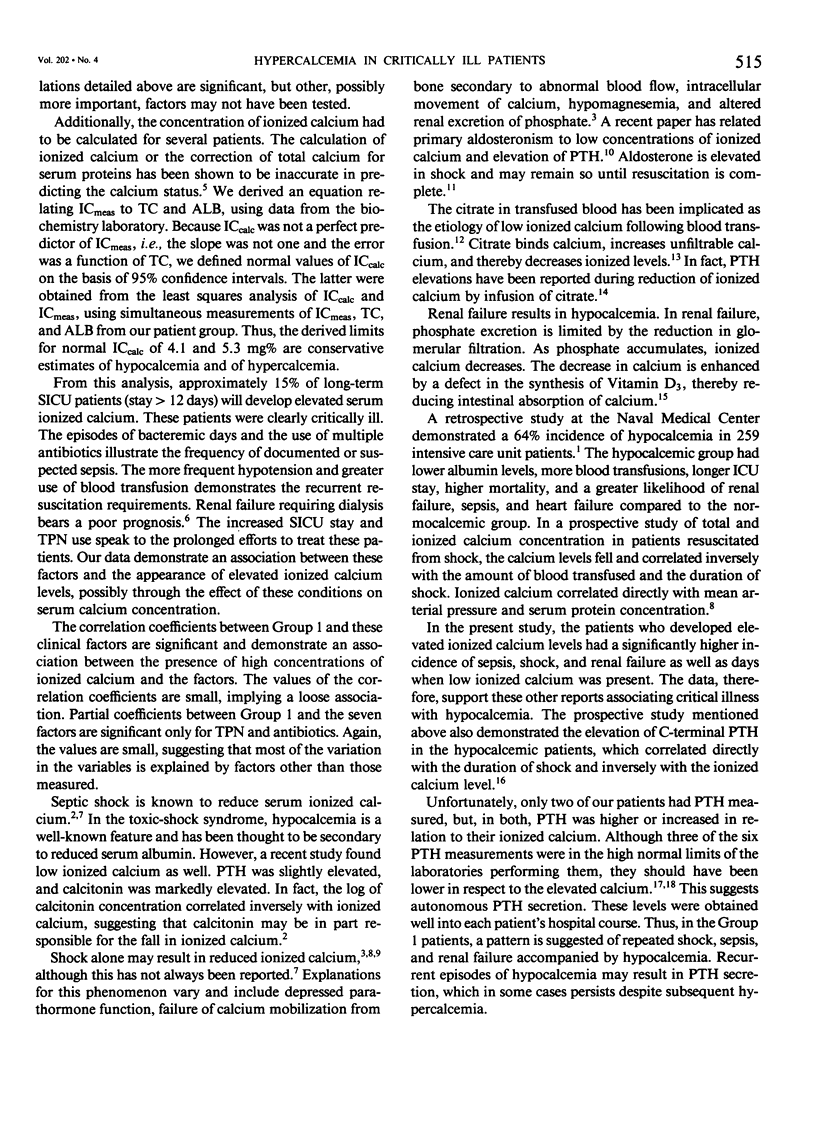

Critical surgical illness, commonly accompanied by shock, sepsis, multiple transfusions, and renal failure, is usually associated with low total calcium and/or low or normal ionized calcium. A seminal case of hypercalcemia in a surgical intensive care unit (SICU) patient prompted the review of 100 patients with longer than average SICU days (greater than 12) to determine the incidence, associated factors, and possible etiologies of this condition. Ten patients had elevated measured, and five others had elevated calculated, ionized calcium (5.9 +/- 0.25 mg%), an incidence of 15%. Compared to the 85 patients who did not develop hypercalcemia, this population had a significantly higher frequency of the following: renal failure, dialysis, total parenteral nutrition (TPN) usage greater than 21 days, bacteremic days greater than 1, transfusions greater than 24 units, shock greater than 1 day, SICU days greater than 36, and antibiotics used greater than 7. In addition, this group had significantly more days of hypocalcemia early in their hospital course. There was no difference in sex, age, mortality, or incidence of respiratory failure. Two patients studied in depth had renal failure requiring dialysis and no malignancy, milk-alkali syndrome, hyperthyroidism, or hypoadrenalism. Parathormone (PTH) concentrations were high normal or elevated (N terminal 20 and 21 pg/ml; C terminal 130 microliters Eq/ml and 1009 pg/ml) at the time of elevated calcium (total 9.2 to 14.6 mg%; ionized 4.9 to 8.2 mg%). Immobilization does not increase PTH. In renal failure, PTH elevation is a consequence of hypocalcemia rather than hypercalcemia. Moreover, five patients did not have renal failure. Shock, sepsis, and multiple transfusions containing citrate may lower total and/or ionized calcium and thus stimulate PTH secretion. Whatever the mechanism, approximately 15% of critically ill surgical patients develop hypercalcemia, which may represent a new form of hyperparathyroidism.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bergstrom W. H. Hypercalciuria and hypercalcemia complicating immobilization. Am J Dis Child. 1978 Jun;132(6):553–554. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1978.02120310017001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernow B., Zaloga G., McFadden E., Clapper M., Kotler M., Barton M., Rainey T. G. Hypocalcemia in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 1982 Dec;10(12):848–851. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198212000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney R. W., McCarron D. M., Haddad J. G., Hawker C. D., DiBella F. P., Chesney P. J., Davis J. P. Pathogenic mechanisms of the hypocalcemia of the staphylococcal toxic-shock syndrome. J Lab Clin Med. 1983 Apr;101(4):576–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cioffi W. G., Ashikaga T., Gamelli R. L. Probability of surviving postoperative acute renal failure. Development of a prognostic index. Ann Surg. 1984 Aug;200(2):205–211. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198408000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley S. B., Shackelford G. D., Robson A. M. Severe immobilization hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, and calcification. Pediatrics. 1979 Jan;63(1):142–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bella F. P., Hawker C. D. Parathyrin (parathyroid hormone): radioimmunoassays for intact and carboxyl-terminal moieties. Clin Chem. 1982 Jan;28(1):226–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drop L. J., Laver M. B. Low plasma ionized calcium and response to calcium therapy in critically ill man. Anesthesiology. 1975 Sep;43(3):300–306. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197509000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans R. A., Bridgeman M., Hills E., Dunstan C. R. Immobilisation hypercalcemia. Miner Electrolyte Metab. 1984;10(4):244–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan C., Lucas C. E., Ledgerwood A. M. Significance of hypocalcemia following hypovolemic shock. J Trauma. 1983 Jun;23(6):488–493. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198306000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howland W. S., Schweizer O., Carlon G. C., Goldiner P. L. The cardiovascular effects of low levels of ionized calcium during massive transfusion. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1977 Oct;145(4):581–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleeman C. R., Better O., Massry S. G., Maxwell M. H. Divalent ion metabolism and osteodystrophy in chronic renal failure. Yale J Biol Med. 1967 Aug 1;40(1):1–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladenson J. H., Lewis J. W., Boyd J. C. Failure of total calcium corrected for protein, albumin, and pH to correctly assess free calcium status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1978 Jun;46(6):986–993. doi: 10.1210/jcem-46-6-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard A., Nelms R. J., Jr Hypercalcemia in diuretic phase of acute renal failure. Ann Intern Med. 1970 Jul;73(1):137–137. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-73-1-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman S., Canterbury J. M., Reiss E. Parathyroid hormone and the hypercalcemia of immobilization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1977 Sep;45(3):425–428. doi: 10.1210/jcem-45-3-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas C. E., Sennish J. C., Ledgerwood A. M., Harrigan C. Parathyroid response to hypocalcemia after treatment of hemorrhagic shock. Surgery. 1984 Oct;96(4):711–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posen S., Clifton-Bligh P., Mason R. S. The measurement of calcium-regulating hormones in clinical medicine. Prog Biochem Pharmacol. 1980;17:220–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick L. M., Laragh J. H. Calcium metabolism and parathyroid function in primary aldosteronism. Am J Med. 1985 Mar;78(3):385–390. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90328-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal A. J., Miller M., Moses A. M. Hypercalcemia during the diuretic phase of acute renal failure. Ann Intern Med. 1968 May;68(5):1066–1068. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-68-5-1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shike M., Harrison J. E., Sturtridge W. C., Tam C. S., Bobechko P. E., Jones G., Murray T. M., Jeejeebhoy K. N. Metabolic bone disease in patients receiving long-term total parenteral nutrition. Ann Intern Med. 1980 Mar;92(3):343–350. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-92-3-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A. F., Adler M., Byers C. M., Segre G. V., Broadus A. E. Calcium homeostasis in immobilization: an example of resorptive hypercalciuria. N Engl J Med. 1982 May 13;306(19):1136–1140. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198205133061903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szyfelbein S. K., Drop L. J., Martyn J. A. Persistent ionized hypocalcemia in patients during resuscitation and recovery phases of body burns. Crit Care Med. 1981 Jun;9(6):454–458. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198106000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toffaletti J. Changes in protein-bound, complex-bound, and ionized calcium related to parathyroid hormone levels in healthy donors during plateletapheresis. Transfusion. 1983 Nov-Dec;23(6):471–475. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1983.23684074265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tori J. A., Hill L. L. Hypercalcemia in children with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1978 Oct;59(10):443–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkington R. W., Delcher H. K., Neelon F. A., Gitelman H. J. Hypercalcemia following acute renal failure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1968 Aug;28(8):1224–1226. doi: 10.1210/jcem-28-8-1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman C., Askanazi J., Hyman A. I., Weber C. Hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria in a critically ill patient. Crit Care Med. 1983 Jul;11(7):576–578. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198307000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters J. L., Kleinschmidt A. G., Jr, Frensilli J. J., Sutton M. Hypercalcemia complicating immobilization in the treatment of fractures. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1966 Sep;48(6):1182–1184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf A. W., Chuinard R. G., Riggins R. S., Walter R. M., Depner T. Immobilization hypercalcemia: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976 Jul-Aug;(118):124–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo P., Carpenter M. A., Trunkey D. Ionized calcium: the effect of septic shock in the human. J Surg Res. 1979 Jun;26(6):605–610. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(79)90056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Torrente A., Berl T., Cohn P. D., Kawamoto E., Hertz P., Schrier R. W. Hypercalcemia of acute renal failure. Clinical significance and pathogenesis. Am J Med. 1976 Jul;61(1):119–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zuiden L., Anquist K. A., Schachar N., Kastelen N. Immobilization hypercalcemia. Can J Surg. 1982 Nov;25(6):646–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]