Abstract

Background

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) is a prevalent metabolic condition during pregnancy that can affect up to 24.9% of pregnancies in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). GDM can impair the mother’s Quality of life (QOL) due to physical, psychological, and social challenges. Understanding how GDM affects the QOL is essential for effective treatment and intervention. This study aims to assess the QOL among women with GDM in the UAE, with a focus on how the condition impacts their overall well-being.

Methods

A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted at Thumbay University Hospital in Ajman, UAE. The study assessed the quality of life of 90 pregnant women with dietary or insulin-treated GDM who visited the antenatal/postnatal OPD and labor unit. A structured questionnaire was used to collect data on “socio-demographic” and obstetrical parameters and the standardized GDMQ-36 for QOL assessment on a five-point Likert scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree) with a score range from 1 to 5.

Results

The study found that 77.8% of the mothers experienced moderate QOL, while 22.2% had high QOL. Furthermore, concerns about high-risk pregnancy had the highest mean score (Mean = 29.59, SD = 10.902), while Medication and treatment had the lowest mean score (Mean = 15.71, SD = 3.036), suggesting lower perceived burden. Support was perceived as moderate (Mean = 23.24, SD = 3.718) and Perceived constraints (Mean = 20.7, SD = 6.173) and complications of GDM (Mean = 16.17, SD = 4.465) also contributed to overall QOL. This study also found that Education level (χ² = 12.936, p = 0.044) and Previous history of GDM (χ² = 5.625, p = 0.018) were significantly associated with QOL, with woman with higher education and no history of GDM reporting a higher QOL.

Conclusion

The study highlights that concerns about high-risk pregnancy and complications of GDM negatively impact QOL. Higher education and no previous GDM history were associated with better QOL, emphasizing the role of education and early intervention, and supportive care in shaping the mother’s well-being.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12884-025-08154-2.

Keywords: Quality of life, Gestational diabetes mellitus, Cross sectional study, Women's health, UAE

Introduction

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) is a common metabolic disorder characterized by glucose intolerance that develops during pregnancy. Globally, GDM affects approximately 14% of pregnancies [1] with rising prevalence attributed to factors such as obesity and advanced maternal age [2]. In the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the prevalence of GDM is notably high, ranging between 7.9% and 24.9%, with some studies reporting rates exceeding 37% depending on screening protocols and population demographics [3].

GDM poses significant short- and long-term health risks for both mothers and newborns, including hypertensive disorders, cesarean deliveries, macrosomia, neonatal hypoglycemia, and increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes later in life [4]. While glycemic control is essential in minimizing these risks, the psychosocial and emotional burden of the condition is often overlooked.

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus can significantly compromise a woman’s quality of life, affecting her emotional well-being, social functioning, and daily routines. The condition often requires women to follow restrictive diets, make substantial lifestyle adjustments, and cope with heightened concerns about pregnancy outcomes, factors which collectively contribute to increased stress and a reduced sense of well-being. Factors such as self-efficacy, social support, and access to culturally tailored health education play a pivotal role in coping and self-management [5]. In the UAE, cultural and lifestyle factors including high-carbohydrate diets, limited physical activity during pregnancy, and varying levels of health literacy can further complicate disease management [3].

Despite the high burden of GDM in the region, few studies have examined its impact on women’s quality of life in the UAE or similar Middle Eastern contexts. Most existing research focuses on clinical outcomes, overlooking the emotional, social, and lifestyle dimensions critical to holistic care. Understanding these dimensions is essential because QoL influences self-care behaviors, coping strategies and ultimately long-term health outcomes for both mother and child.

Therefore, this study aims to explore the clinical association between GDM and quality of life among women in the UAE, with specific objectives to assess QoL levels and investigate their relationship with selected demographic and obstetrical variables. Addressing this gap will help guide culturally sensitive healthcare interventions and policies aimed at improving maternal well-being and reducing chronic disease risk in this vulnerable population.

Aim of the study

To explore the clinical association between Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Quality of Life among women.

Objectives of the study

Assess the Quality of life among women with gestational diabetes mellitus.

To determine the predictors of Quality of Life among women with Gestational Diabetes.

Associate the Quality of life with selected demographic variables of the women with gestational diabetes mellitus.

Methods

A Quantitative research approach with a descriptive cross-sectional survey design was used to assess the Quality of Life among Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in a Tertiary Care Hospital, Ajman, UAE.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All participants included in the study had confirmed GDM diagnosis following WHO guidelines. GDM was diagnosed using a 75-gram oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) performed between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation. A diagnosis of GDM was made if any one of the following plasma glucose values was met or exceeded: (Fasting glucose ≥ 5.1 mmol/L (92 mg/dL, 1-hour post-glucose ≥ 10.0 mmol/L (180 mg/dL), 2-hour post-glucose ≥ 8.5 mmol/L (153 mg/dL). These results were documented in the mother’s prenatal medical records.

This study sample included all the pregnant women with dietary or insulin-treated GDM attending the Antenatal/Postnatal OPD and admitted in the Labor Units of the Tertiary Care Hospital, Ajman, UAE from 1/4/2025 till 27/5/2025. The inclusion criteria were pregnant women who had either dietary- or insulin-treated gestational diabetes mellitus, had been diagnosed with GDM at least two weeks prior, were at least 18 years old, and were able to read and understand English or Arabic.

Exclusion criteria included pregnant women with preexisting Type I or Type II diabetes mellitus, as well as those with complications in their current pregnancy, such as multiple pregnancies, gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, or threatened preterm birth.

Study design

Total enumeration plus convenience sampling, a non-probability sampling technique, was employed in this study. A total of 90 pregnant women with GDM who satisfied the inclusion criteria were included during the 6–8 week data collection period. By applying a typical prevalence-based formula (Z = 1.96, p = 0.075, d = 0.05), it was determined that a minimum of 107 samples were needed. Nevertheless, the necessary sample was lowered to roughly 63 after applying a finite population correction for an estimated 150–200 women with GDM during the study period. As a result, the actual sample size of 90 participants surpassed this requirement and included all available and eligible individuals. The mothers were told about the project, and before to data collection, their informed consent was acquired. The study was explained to the mothers, and informed consent was obtained prior to data collection.

A structured questionnaire was developed specifically for this study to assess the socio-demographic and obstetrical characteristics of women with gestational diabetes mellitus. The socio-demographic section included items such as age, education, and occupation, while the obstetrical section covered variables such as gravidity, previous GDM history, and obstetrical complications. The complete English version of the questionnaire is provided as (Supplementary File 1).

The Quality of life questionnaire for women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDMQ-36), a standardized tool with an opinionnaire on a 5-point Likert scale (Strongly Agree, Agree, Not sure, Disagree and Strongly Disagree) was used to assess the QOL of women with GDM consisting of 5 domains [6]:

-

A.

Concerns about high-risk pregnancy (11 items),

-

B.

Perceived constraints (7 items).

-

C.

Complications of GDM (6 items).

-

D.

Medication and treatment (5 items).

-

E.

Support (6 item).

Due to the cultural sensitivity of Question 17 which states “My sexual activity has decreased due to GDM” the “GDMQ36” was modified, and this question was removed, thus making the total score out of 175 instead of the usual 180 and adapted version is provided in (Supplementary File 2).

As each area has a different number of questions, for easier interpretation, the total score of the questionnaire, as well as the score for each area, was calculated to be 0 to 100. Thus, the best being high QOL in each area was 100 points and the worst being low QOL was 0.

Adjusted score = (acquired raw score/maximum possible score) *100.

To classify the QOL levels as low, moderate, or high, we followed the classification system described in previous related research, as a reference in this study [7]. According to this classification:

Low QOL: scores from 0 to 33.

Moderate QOL: scores from 34 to 66.

High QOL: scores from 67 to 100.

The questionnaire was prepared in English and translated to Arabic and retranslated to English to maintain the consistency of the tool.

Validity and reliability

Content validity of the above tools was obtained from three nursing experts with PhD specialties in obstetrics for assessment of the validity. The reliability of the GDMQ-36 questionnaire was established by its developers. Internal consistency was measured using Cronbach’s alpha, with an overall coefficient of 0.93 for the entire instrument and subscale coefficients ranging from 0.77 to 0.90, indicating good to excellent reliability. Instrument stability was confirmed through a test-retest method using the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC), which showed an overall ICC of 0.95 and subscale ICCs between 0.85 and 0.98, demonstrating excellent stability. These findings support the use of the GDMQ-36 as a reliable and stable instrument to assess quality of life among women with gestational diabetes mellitus [6].

Statistics

In this study, Descriptive and Inferential statistics were used to analyze and interpret the data, which were coded and tabulated into an excel spreadsheet and further analyzed using SPSS v26 software. Descriptive statistics such as Frequency and Percentage were used to describe the socio- demographic and gynecological variables. Also, Regression analysis was carried out to determine the predicators for QoL among with GDM and quantify the relationship between the predictors and QoL score.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. For continuous variables, the mean and standard deviation (SD) were reported when the data followed a normal distribution. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The results indicated no significant departure from normality (W = 0.9836, p = 0.316), justifying the use of mean ± SD. If any variable had not been normally distributed (p < 0.05), the median and interquartile range (IQR) would have been used instead.

Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. The Chi-Square test was used to assess associations between categorical variables. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Note on AI use

ChatGPT (OpenAI) was used to assist in refining the grammar, structure, and clarity of the manuscript text. No content generation, data analysis, or interpretation was performed by the AI. Final editing and approval were conducted by the authors.

Results

A total of 90 pregnant women diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus participated in this study. Most of the participants were English-speaking, accounting for 66.7%, 77.9% were aged between 26 and 40 and 74.4% identified as Muslim. The most prevalent nationalities among women were Indian 25.6% followed by Arab 22.2% and Pakistani 18.9% (Supplementary Table 1).

The participants’ educational attainment was rather high, with nearly half, 48.9% holding a bachelor’s degree and 17.8% having earned a master’s degree or higher. All participants were married; the majority were housewives 67.8% and lived in nuclear families 73.3%. More than half of the participants reported their monthly family income ranged from 5,000 to 15,000 AED. Notably, 96.7% were satisfied with their spouses, and 83.3% had previously encountered material concerning GDM (Supplementary Table 1).

In terms of obstetric history, most women had one to three children, accounting for 63.4% and two to four pregnancies at 63.3%. More than half, 53.3% had a previous history of GDM, with only a modest fraction reporting additional gynecological problems at 6.7% or obstetrical problems at 18.9%. A significant proportion of 38.9% had experienced a previous miscarriage or abortion (Supplementary Table 1).

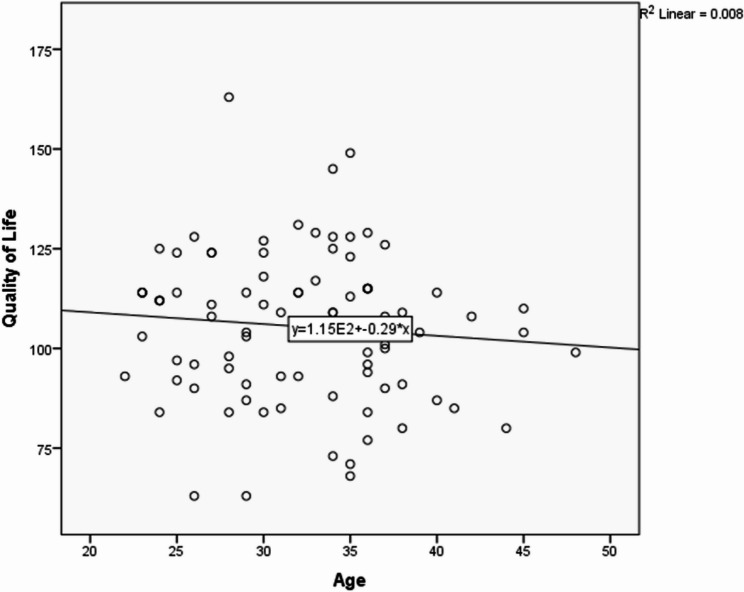

Assessment of quality of life using the GDMQ-36 revealed that 77.8% of participants experienced a moderate QOL, while 22.2% reported a high QOL. Notably, none of the subjects indicated a low quality of life (See Fig. 1 and Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Frequency distribution of quality of life among pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus

Table 1.

Frequency and percentage distribution of classification of quality of life among pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus

| Classification of QOL | Full score based on QOL GDMQ36 | QOL GDMQ36 score out of 100 | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 1–58 | 0–33 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Moderate | 59–117 | 34–66 | 70 | 77.8 |

| High | 118–175 | 67–100 | 20 | 22.2 |

| Total QOL | 90 | 100 |

When sub-parameters of QOL were examined, concerns regarding high-risk pregnancy had the highest mean score (mean = 29.59, SD = 10.90), followed by perceived support (mean = 23.24, SD = 3.72). While Medication and treatment (mean = 15.71, SD = 3.04) had the lowest score, suggesting lower perceived burden. Other categories, such as perceived constraints (mean = 20.74, SD = 6.17), and complications of GDM (mean = 16.17, SD = 4.47) also had an impact on total QOL.

While concerns about high-risk pregnancy and perceived constraints varied more among respondents, perceived support was the most positively assessed, with more than 90% agreeing or strongly agreeing that they received appropriate assistance (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean and SD of Sub-parameters of Quality of life among pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus n=90

| Sub-parameters of QOL | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Concern about High-risk Pregnancy | 29.59 | 10.902 |

| Perceived constraints | 20.74 | 6.173 |

| Complications of GDM | 16.17 | 4.465 |

| Medication and treatment | 15.71 | 3.036 |

| Support | 23.24 | 3.718 |

Chi-square analysis was used to investigate the relationships between QOL and a variety of demographic and obstetrical variables. Among the demographic characteristics, education level was the only factor significantly associated with QOL (χ² = 12.936, p = 0.044). Participants with higher educational attainment reported improved quality of life. Other variables such as age, religion, nationality, occupation, family type, income, marital relationship and prior exposure to GDM material, did not show statistically significant associations. Although mean QoL scores were marginally higher for English-speaking, employed women and those who had received information about GDM, these differences were not statistically significant (Supplementary Table 2).

GDM history was found to have a significant association with QOL (χ² = 5.625, p = 0.018). Participants without a previous GDM diagnosis reported greater QOL than those with a recurrent diagnosis. Other obstetrical characteristics, such as number of children, number of pregnancies or miscarriage/abortion, did not have a significant effect on QOL. Although trends were observed, such as women with fewer children and pregnancies being more likely to have a high QOL, these differences were not statistically significant (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of Quality of life with the gynaecological variables of pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus n =90

| Gynaecological Variable | Quality of life | Chi-Square | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | High | ||||||

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | χ2 | P-value | ||

| Number of Children | 0 | 12 | 17.1 | 4 | 20.0 | 9.751 |

0.203 NS |

| 1 | 10 | 14.3 | 8 | 40.0 | |||

| 2 | 22 | 31.4 | 3 | 15.0 | |||

| 3 | 11 | 15.7 | 3 | 15.0 | |||

| 4 | 5 | 7.1 | 2 | 10.0 | |||

| 5 | 5 | 7.1 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| 6 | 3 | 4.3 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| 7 | 2 | 2.9 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| Number of Pregnancy | 0 | 1 | 1.4 | 1 | 5.0 | 5.364 |

0.718 NS |

| 1 | 11 | 15.7 | 4 | 20.0 | |||

| 2 | 21 | 30.0 | 7 | 35.0 | |||

| 3 | 10 | 14.3 | 3 | 15.0 | |||

| 4 | 13 | 18.6 | 3 | 15.0 | |||

| 5 | 3 | 4.3 | 2 | 10.0 | |||

| 6 | 6 | 8.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| 7 | 2 | 2.9 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| 8 | 3 | 4.3 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| Previous history of GDM | Yes | 42 | 60.0 | 6 | 30.0 | 5.625 | 0.018** |

| No | 28 | 40.0 | 14 | 70.0 | |||

| Any other Gynaecological Complications1 | Yes | 6 | 8.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1.837 |

0.175 NS |

| No | 64 | 91.4 | 20 | 100.0 | |||

| Previous Obstetrical Complication | Yes | 16 | 22.9 | 1 | 5.0 | 3.238 |

0.072 NS |

| No | 54 | 77.1 | 19 | 95.0 | |||

| History of miscarriage and abortion | Yes | 29 | 41.4 | 6 | 30.0 | 0.855 |

0.355 NS |

| No | 41 | 58.6 | 14 | 70.0 | |||

**Significant at p<0.05

NS Not significant

1“Gynecological Complications” refers to the self-reported presence of any gynecological condition (e.g., PCOS, endometriosis, obesity-related menstrual irregularities), collected through a Yes/No response. Specific diagnoses were not recorded

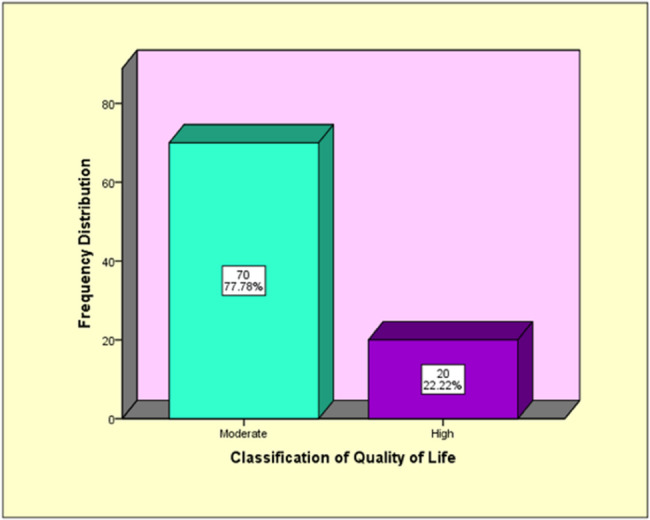

In addition to the chi-square analyses, linear regression models were used to explore the relationship between quality of life and both age and selected gynecological variables.

The scatter plot supports the statistical finding that age has a very weak and non-significant association with quality of life among women with GDM. The line of best fit shows a slight downward trend, suggesting that QoL marginally decreases as age increases; however, the R² value of 0.008 indicates that age explains less than 1% of the variation in QoL scores. This explains that the relationship is not statistically significant (p = 0.390) (See Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Regression analysis with quality of life and age of the mothers with GDM

The regression analysis examining the relationship between obstetrical variables and quality of life among women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus revealed that approximately 17.2% of the variation in QoL scores could be explained by the included variables. Among these, previous history of GDM and past obstetric complications were found to be statistically significant predictors. Specifically, women with a prior history of GDM reported lower QoL scores (B = −8.780, p = 0.035), indicating that the recurrence of GDM may negatively impact their physical and emotional well-being. Similarly, those with previous obstetric complications also demonstrated significantly reduced QoL (B = −13.005, p = 0.014), likely due to heightened anxiety or medical vulnerability in the current pregnancy. Other variables such as total number of children, total pregnancies, history of miscarriages or abortions, and other gynecological complications did not show a statistically significant relationship with QoL (See Table 4).

Table 4.

Regression analysis with quality of life and gynaecological variables

| Gynaecological Variables | B | Std. Error | 95.0% Confidence Interval | β | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||

| (Constant) | 114.623 | 4.000 | 106.668 | 122.578 | 0.000 | |

| Total Children | 0.848 | 2.486 | −4.098 | 5.793 | 0.079 | 0.734 |

| Total Pregnancies | −1.298 | 2.350 | −5.972 | 3.376 | −0.130 | 0.582 |

| Previous History of GDM | −8.780 | 4.089 | −16.913 | −0.648 | −0.239 | 0.035 |

| Any other Gynaecological Complications | −8.561 | 7.956 | −24.385 | 7.263 | −0.117 | 0.285 |

| Previous Obstetric complications | −13.005 | 5.196 | −23.340 | −2.670 | −0.278 | 0.014 |

| History of miscarriages or abortions | 1.654 | 4.723 | −7.740 | 11.048 | 0.044 | 0.727 |

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the quality of life of women with gestational diabetes mellitus and explore its association with selected demographic and obstetrical variables. The findings demonstrated that the overall quality of life in women with GDM was primarily moderate, which is consistent with previous research [7]. The absence of low QOL scores among the study population may indicate adequate baseline healthcare access, support systems or personal coping strategies. This suggests that while essential care is being provided, deeper psychosocial or lifestyle burdens persist, which may not be fully addressed by current GDM management protocols (Table 5).

Table 5.

Regression model summary for the effect of gynaecological variables on quality of life

| Gynaecological Variables | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square |

| .415a | 0.172 | 0.113 |

r = multiple correlation coefficient; R² = proportion of variance in quality of life explained by gynaecological variables; adjusted R² = adjusted value accounting for sample size and number of predictors

The GDMQ-36 assessed five domains, with “Concern about High-Risk Pregnancy” having the highest mean score (29.59 ± 10.90). This indicates significant worry among women regarding probable consequences such as hypertension, macrosomia, or cesarean birth. This is consistent with prior research emphasizing the psychological impact of high-risk pregnancies [8]. This finding is significant because it reflects ongoing anxiety related to fetal and maternal health, even in women receiving active medical care. It highlights the need for integrated psychological support within prenatal diabetes care to reduce fear-driven stress and improve overall emotional well-being.

Moreover, this pattern of anticipatory anxiety has been reported in diverse geographic contexts, suggesting it is a universal experience among women with GDM The consistency across countries indicates that anxiety related to pregnancy outcomes may serve as a core marker of GDM-related quality of life deterioration, making it a critical target for intervention [8].

In contrast, “Medication and Treatment” scored the lowest (15.71 ± 3.04), indicating that pharmacological therapies were well-tolerated and potentially supported by the healthcare system. This finding could be attributable to familiarity with treatment procedures and adequate support, as evidenced by prior studies demonstrating the acceptability and efficacy of insulin and metformin for GDM therapy [9]. This may imply that current treatment protocols and patient education on pharmacological management are effective in this setting, representing a strength of the healthcare delivery system.

Other domains, such as “Support” (mean = 23.24 ± 3.72) and “Perceived Constraints” (mean = 20.74 ± 6.17), also influenced QOL. Moderate levels of support were observed, which is consistent with previous research demonstrating that social and healthcare support improves quality of life [10]. Lifestyle adjustments, particularly food limits, presented substantial obstacles. This is confirmed by data that women with GDM had a lower perceived freedom to eat [11]. This finding is important as it suggests that nutritional guidance may need to be more culturally sensitive, considering the traditional high-carbohydrate dietary patterns common in the region. Without this adjustment, perceived constraints could worsen adherence and psychological distress.

Although the GDMQ-36 did not differentiate specific sources of support, it is reasonable to assume that women received support from family members, healthcare professionals (especially diabetes educators and obstetricians) and peer groups. Prior literature highlights that emotional and informational support from these sources can significantly alleviate the psychological burden of GDM, improve treatment adherence and positively influence QOL [12].

Recent qualitative evidence further suggests that social support for women with GDM is multidimensional, encompassing communal support from family and peers, indirect support involving logistical assistance such as childcare and transportation, and direct support including help with healthy eating and glucose monitoring [13]. These forms of support facilitate adherence to treatment and lifestyle modifications, which are essential for improving quality of life. The implication is that QOL can be improved not only through medical management but also through strengthening and diversifying social support networks. Future studies should consider exploring these specific sources of support more explicitly to better understand their unique contributions to patient well-being.

Clinically, the moderate QoL found in women with GDM indicates that, despite treatment, they still encounter significant obstacles that may affect their day-to-day activities. This degree of QoL may reflect ongoing concerns about the results of pregnancy, shame or anxiety about controlling blood sugar levels, and stress from rigorous dietary changes that might go against family or cultural eating customs. Additionally, a moderate QoL score may indicate concerns about labor and delivery problems, limitations in social and physical activities, and a diminished sense of freedom due to lifestyle constraints and greater medical surveillance. These elements used together may have an impact on family relations and emotional health. From a clinical perspective, this underlines the need for comprehensive, culturally sensitive education, accessible dietary counseling that respects local food practices, and regular psychological support to address emotional stressors. Providing tailored support can help women feel more empowered, improve adherence to treatment plans, and ultimately enhance both maternal and fetal outcomes [12].

Regarding demographic variables, education level had a significant association with QOL (χ² = 12.936, p = 0.044). Women with greater education levels reported higher quality of life, which was most likely attributable to improved health literacy and self-care. This conclusion confirms prior research that shows that educational achievement improves QOL by enabling women to properly manage GDM [14]. Furthermore, educational treatments have been shown to lower fear, worry and depression, which contributes to better mother well-being [8].

From a clinical perspective, this underlines the need for comprehensive, culturally sensitive education, accessible dietary counseling that respects local food practices, and regular psychological support to address emotional stressors. Providing tailored support can help women feel more empowered, improve adherence to treatment plans, and ultimately enhance both maternal and fetal outcomes. Regarding demographic variables, education level had a significant association with QOL (χ² = 12.936, p = 0.044). Women with greater education levels reported higher quality of life, which was most likely attributable to improved health literacy and self-care. This conclusion confirms prior research that shows that educational achievement improves QOL by enabling women to properly manage GDM [14]. Furthermore, educational treatments have been shown to lower fear, worry and depression, which contributes to better mother well-being [8]. This finding supports the development of targeted educational interventions, particularly for women with lower education levels, to reduce disparity in GDM outcomes and empower patients through knowledge.

Other variables, including age, language, religion, country, occupation, family income, family type, spousal relationship satisfaction and exposure to information about GDM, had no statistically significant association with QOL (p > 0.05). Although no statistically significant association was found between family income and quality of life, it is important to interpret these findings within the local economic context. The average monthly cost of living for a family of four in Ajman in 2025 is approximately 11,600 AED [15]. Since the income of participants ranged from 5,000 to 15,000 AED, this suggests that a portion of the sample may experience financial constraints that could indirectly impact their well-being. While income alone may not predict QoL in this study, its interaction with living expenses, healthcare access, and dietary management remains relevant. This highlights the importance of offering financial guidance and improving access to affordable resources to support women with GDM, particularly those in lower-income brackets.

However, although the differences were not statistically significant, English-speaking and employed women reported slightly higher QoL scores, which may reflect greater access to healthcare resources and support. This is somewhat confirmed by Iranian research, which discovered that higher socioeconomic level and employment correspond with improved quality of life outcomes, notably in psychological and social dimensions [16]. This suggests that language and occupation may serve as proxy indicators for health literacy and access, both of which influence how women experience and manage GDM.

Although spousal relationship satisfaction was not statistically significant, the high satisfaction rate (96.7%) among participants indicates an indirect positive impact on emotional well-being. This is consistent with research suggesting that emotional connection and everyday partner support reduce stress and maintain relationship satisfaction throughout pregnancy [17]. This implies that partner engagement strategies could be included in GDM education sessions to enhance maternal emotional support and treatment adherence.

Among obstetrical variables, a history of GDM was significantly associated with QOL (χ² = 5.625, p = 0.018). Women with no prior GDM were more likely to report high QOL, whereas those with repeating episodes reported more moderate QOL levels. This confirms research demonstrating that recurring GDM causes cumulative physical and emotional consequences, which may outweigh the coping gains received from previous encounters [10]. These women also experience increased levels of anxiety and stress because of the anticipation of difficulties [5]as well as higher rates of depression and mental distress [8]. This finding signals that multiparous women with prior GDM may require proactive mental health screening and additional resources, as repeat experiences may exacerbate emotional burden rather than build resilience. These findings were further supported by regression analysis. The linear regression model confirmed that a previous history of GDM and prior obstetric complications were statistically significant predictors of poorer quality of life. Women with a previous diagnosis of GDM experienced notably lower QOL scores, likely due to the emotional and physical toll of managing recurrent illness. Similarly, those with prior obstetric complications may carry psychological burdens such as fear of recurrence or trauma-related anxiety, which negatively influence their well-being during subsequent pregnancies. Although other gynecological factors such as number of children or pregnancies and history of miscarriage did not reach statistical significance, the model as a whole explained 17.2% of the variance in QOL. This reinforces the notion that personal medical history—particularly adverse or high-risk outcomes—can deeply affect maternal perceptions of quality of life during a GDM pregnancy. Clinical interventions may benefit from stratifying support based on these risk histories to provide tailored emotional and medical care.

Finally even though Other obstetrical variables, such as number of pregnancies or children and history of miscarriage/abortion, did not have statistically significant association with QOL (p > 0.05), it is indicated that women who had fewer pregnancies or children reported higher quality of life. Supporting research suggests that primiparity, a younger maternal age and strong social support systems are linked to better pregnancy outcomes [18]. The absence of previous deliveries may result in lower cumulative physical strain and psychological stress, allowing first-time moms to have a higher quality of life.

Strengths and limitations

This study had a cross-sectional design which enabled the gathering of real-time data during pregnancy, providing insights into the direct impact of GDM on maternal well-being. However, the cross-sectional approach used which records associations at a single moment in time rather than changes over time, restricts the capacity to demonstrate causal correlations between quality of life and gestational diabetes mellitus. Secondly, the results might not apply to all women with GDM as the study was conducted from a single hospital in Ajman, UAE, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions or healthcare settings in Ajman. Also, the study relied on self-reported data from the GDMQ-36 questionnaire, which may introduce recall bias, especially when describing prior experiences or sentiments, or social desirability bias, where individuals may react in ways they believe to be more acceptable. Finally, the study did not collect or adjust for BMI, which may influence quality of life outcomes in women with GDM. A more thorough understanding of QoL in this population may be achieved through future studies that include BMI and other relevant clinical parameters, use mixed-method approaches, adopt longitudinal designs, and draw on multi-center samples.

Implication on nursing practice

To improve the quality of life of women with GDM, nursing practices should adopt holistic approaches that address both physical and emotional requirements. Priority should be given to patient education, psychological support, and culturally sensitive care. Standardized standards for early screening, personalized care plans, and interdisciplinary teamwork are critical.

Implication on nursing research

The focus of research should be on establishing evidence-based interventions to improve the quality of life of women with GDM. Future research must investigate the psychological, social and cultural aspects that influence QOL. Nursing research capability can be strengthened by including quality of life research into courses and encouraging student participation in clinical investigations.

Implication on nursing education

The nursing curriculum should incorporate contemporary GDM management practices, emphasizing psychological support, patient education, and cultural competency. Regular training programs and workshops are required to provide nurses with the necessary skills for holistic treatment.

Implication on nursing administration

Nursing leaders should ensure that women with GDM receive evidence-based care. Regular staff training, continuous education, and quality control procedures are critical for providing comprehensive and patient-centered treatment.

Conclusion

This study found that most women with gestational diabetes mellitus in the UAE reported a moderate quality of life, with concerns about high-risk pregnancy emerging as the most prominent domain negatively impacting their well-being. Among the demographic and gynecological variables examined, only education level and a history of GDM showed significant associations with QOL, highlighting the role of health literacy and the cumulative emotional and physical burden of recurrent GDM.

These findings reflect the unique sociocultural and economic context of the study population, which includes linguistic diversity, variable access to health information, and dietary practices that may complicate disease management. The results emphasize the need for patient-centered, culturally tailored nursing interventions that address not only medical needs, but also psychosocial and lifestyle challenges faced by women with GDM.

Future research should incorporate larger, more diverse samples and include control groups, such as pregnant women without GDM, to better isolate the impact of GDM on quality of life. Longitudinal designs would also help capture how QOL evolves throughout pregnancy and postpartum, and how interventions can be timed for maximum benefit.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms. Joselly Monickaraj for her valuable support andguidance in statistical analysis during the study. We would also like to thank Dr. Veena M. Joseph and Ms.Thushara Sekhar for their supervision, academic guidance, and critical revisions.We also thank the pregnantwomen with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) for their participation andcooperation throughout the research process.

Abbreviations

- GDM

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

- QOL

Quality Of Life

- UAE

United Arab Emirates

- AED

United Arab Emirates Dirham

- OPD

Outpatient Department

- GDMQ-36

Quality of life questionnaire for women with gestational diabetes mellitus

Author contributions

..R.M took the lead in data collection, analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. B.S and A.B contributed to data collection and assisted in manuscript editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Funding statement

No external funding was received.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Gulf Medical University Ajman, UAE. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after explaining the purpose of the study. Participation was voluntary, and confidentiality and anonymity were assured throughout the research process.

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Clinical trial registration

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wang H, Li N, Chivese T, Werfalli M, Sun H, Yuen L, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: estimation of global and regional gestational diabetes mellitus prevalence for 2021 by international association of diabetes in pregnancy study group’s criteria. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109050. 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao X, Zhang X, Cai R, Duan Z, Xu Q, Shen F, et al. Advanced maternal age, overweight and obese positively correlate to the abnormal plasma glucose among gestational diabetes mellitus women even with physical exercise > 90 min/day: a prospective cohort study in Shanghai. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):21191. 10.1038/s41598-025-09097-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bashir MM, Ahmed LA, Alshamsi MR, Almahrooqi S, Alyammahi T, Alshehhi SA, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional survey of its knowledge and associated factors among united Arab Emirates university students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(14):8381. 10.3390/ijerph19148381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Rifai RH, Abdo NM, Paulo MS, Saha S, Ahmed LA. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in the middle East and North Africa, 2000–2019: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Front Endocrinol. 2021;12:668447. 10.3389/fendo.2021.668447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ansarzadeh S, Salehi L, Mahmoodi Z, Mohammadbeigi A. Factors affecting the quality of life in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: a path analysis model. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:1–9. 10.1186/s12955-020-01293-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mokhlesi S, Simbar M, Ramezani Tehrani F, Kariman N, Alavi Majd H. Quality of life questionnaire for women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDMQ-36): development and psychometric properties. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:1–4. 10.1186/s12884-019-2614-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malik R, Roy SM. Assessment of quality of life among antenatal women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2024. 10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20240304. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mokhlesi S, Simbar M, Tehrani FR, Kariman N, Majd HA. Quality of life and gestational diabetes mellitus: a review study. Interventions. 2019;7(3):255–62. 10.15296/ijwhr.2019.43. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garg R, Roy P, Agarwal P. Gestational diabetes mellitus: challenges in diagnosis and management. J South Asian Feder Obst Gynaecol. 2018;10(1):54–60. 10.5005/jp-journals-10006-1558. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simbar M, Mokhlesi S, Tehrani FR, Kariman N, Majd HA, Javanmard M. Quality of life and associated factors among mothers with gestational diabetes mellitus by using a specific GDMQ-36 questionnaire: a cross-sectional study. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2023;28(2):188–93. 10.4103/ijnmr.ijnmr_474_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Won S, Kim HJ, Park JY, Oh KJ, Choi SH, Jang HC, Moon JH. Quality of life in women with gestational diabetes mellitus and treatment satisfaction upon intermittently scanned continuous glucose monitoring. J Korean Med Sci. 2024;40. 10.3346/jkms.2025.40.e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Jung S, Kim Y, Park J, Choi M, Kim S. Psychosocial support interventions for women with gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2021;27(2):75–92. 10.4069/kjwhn.2021.05.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merchant T, DiTosto JD, Gomez-Roas M, Williams BR, Niznik CM, Feinglass J, Grobman WA, Yee LM. The role of social support on Self‐Management of gestational diabetes mellitus: A qualitative analysis. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2025. 10.1111/jmwh.13782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Rokni S, Rezaei Z, Noghabi AD, Sajjadi M, Mohammadpour A. Evaluation of the effects of diabetes self-management education based on 5A model on the quality of life and blood glucose of women with gestational diabetes mellitus: an experimental study in Eastern Iran. J Prev Med Hyg. 2022. 10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2022.63.3.2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Numbeo. Cost of Living in Ajman [Internet]. Numbeo; 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.numbeo.com/cost-of-living/in/Ajman

- 16.Kazemi F, Nahidi F, Kariman N. Assessment scales, associated factors and the quality of life score in pregnant women in Iran. Global J Health Sci. 2016;8(11):128–39. 10.5539/gjhs.v8n11p127. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar SA, Brock RL, DiLillo D. Partner support and connection protect couples during pregnancy: a daily diary investigation. J Marriage Fam. 2022;84(2):494–514. 10.1111/jomf.12798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lagadec N, Steinecker M, Kapassi A, Magnier AM, Chastang J, Robert S, Gaouaou N, Ibanez G. Factors influencing the quality of life of pregnant women: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:1–4. 10.1186/s12884-018-2087-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.