Abstract

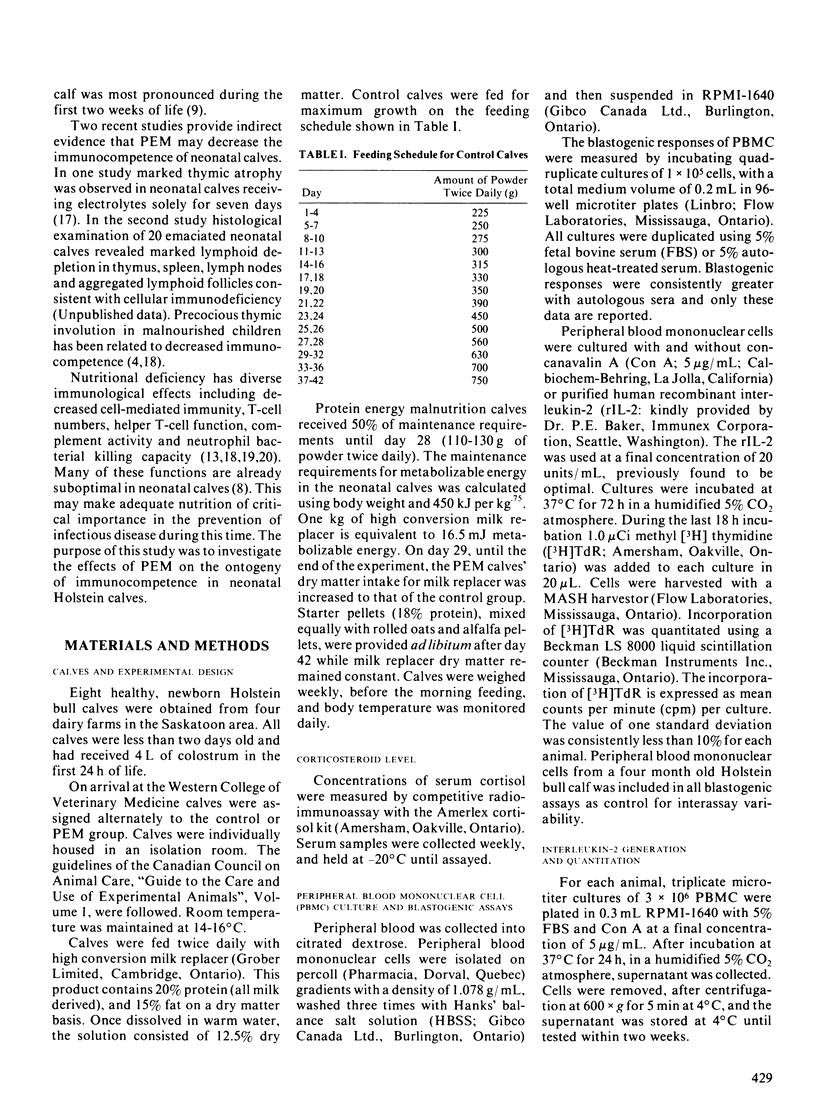

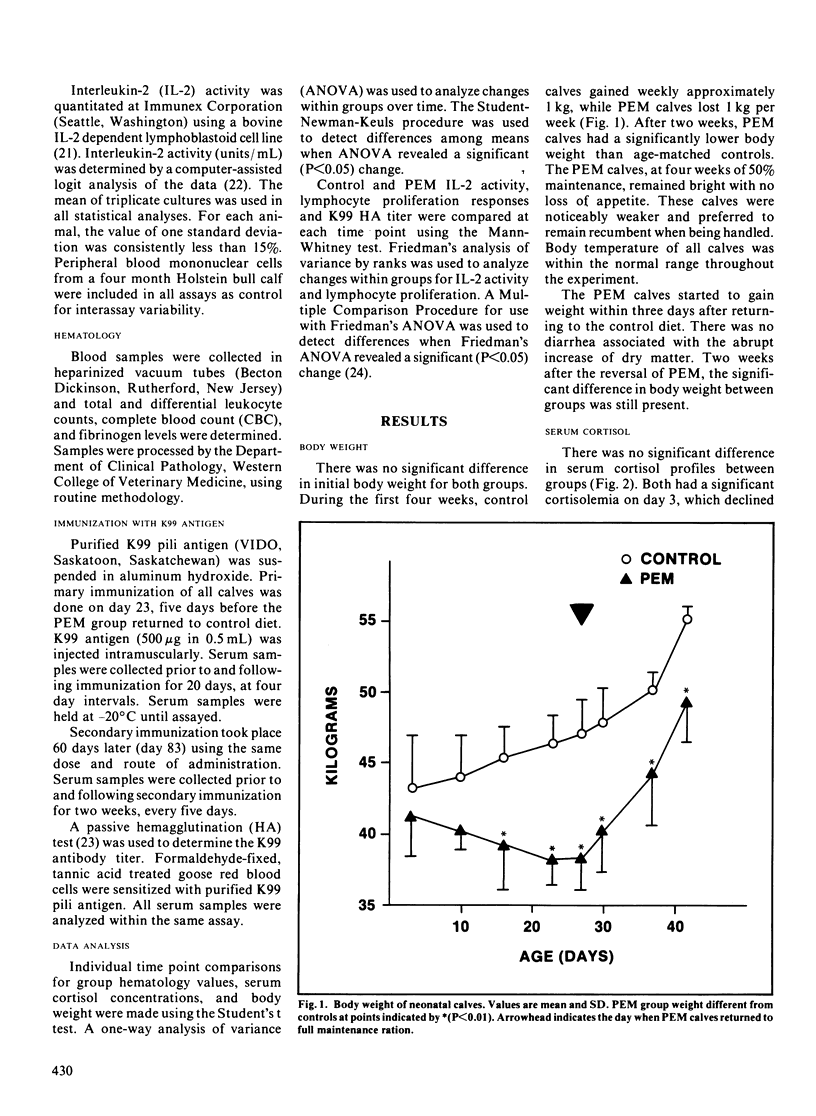

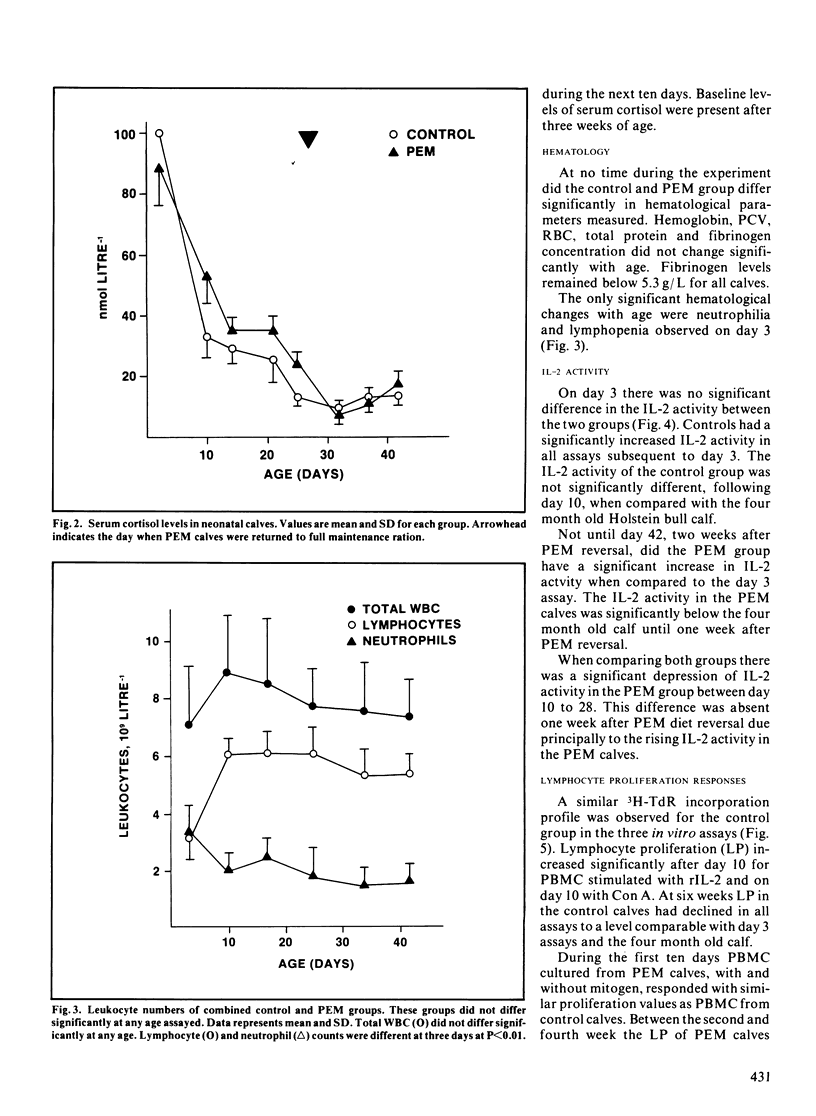

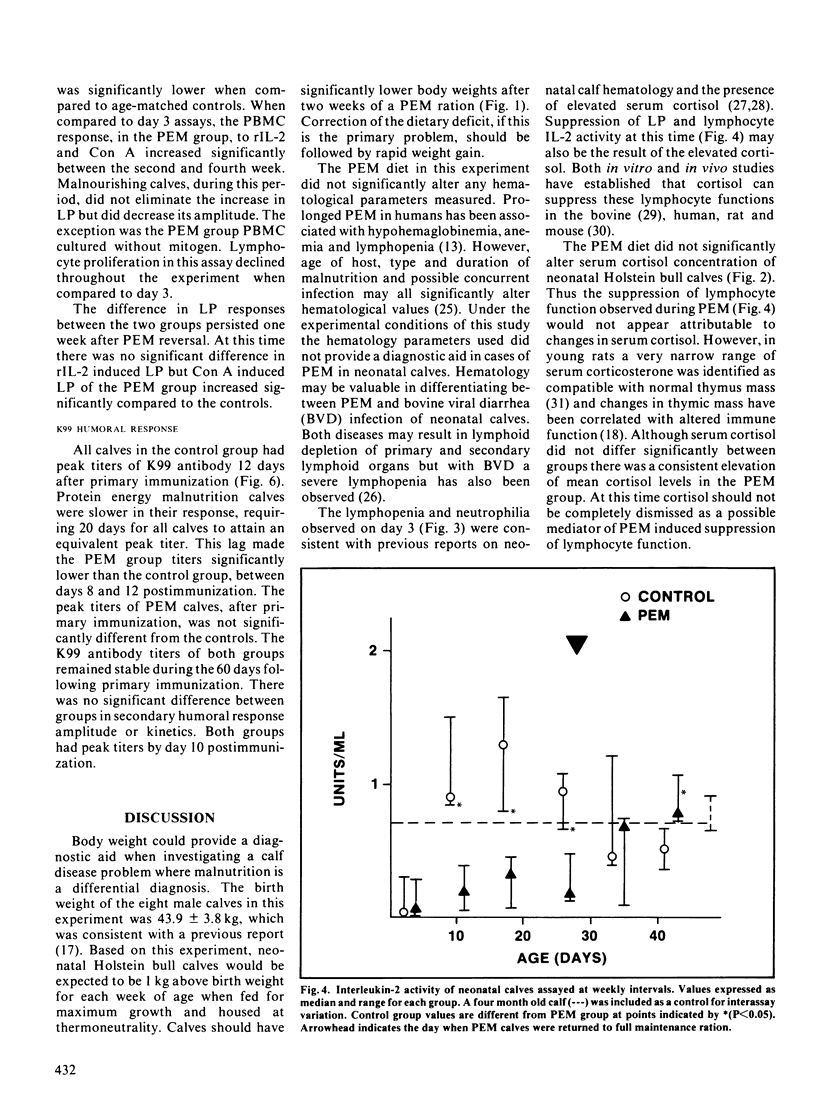

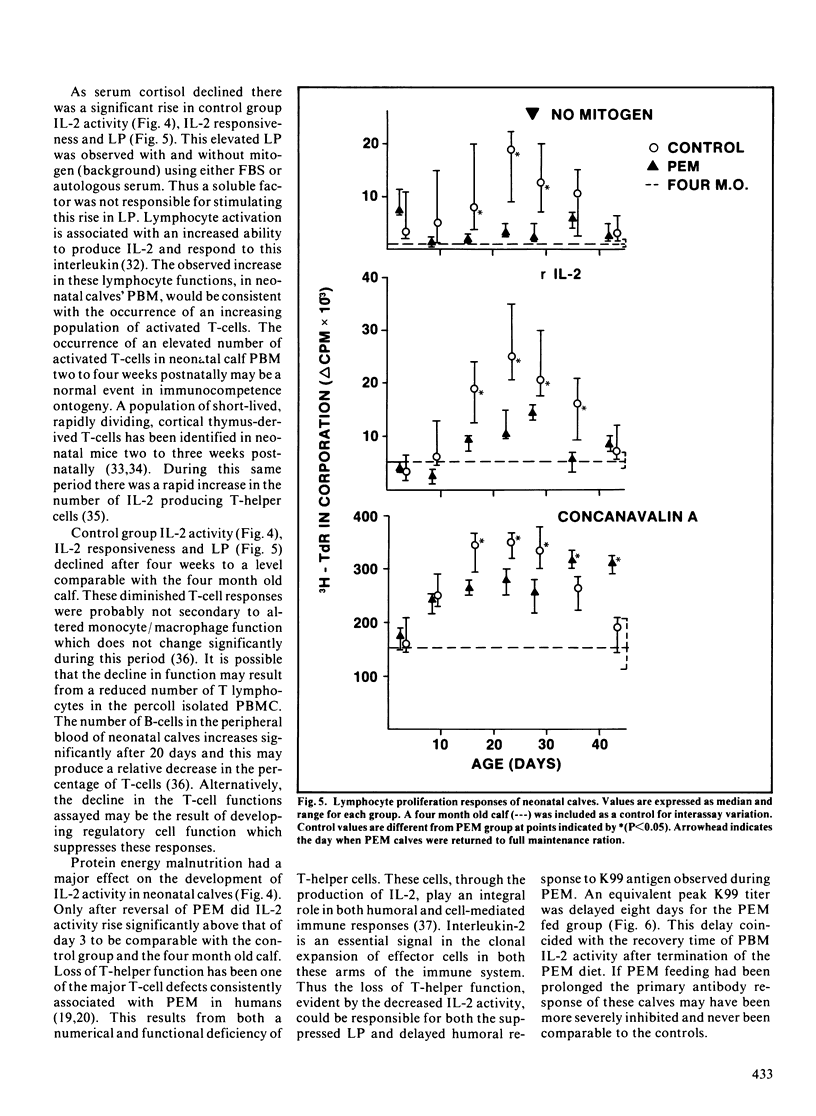

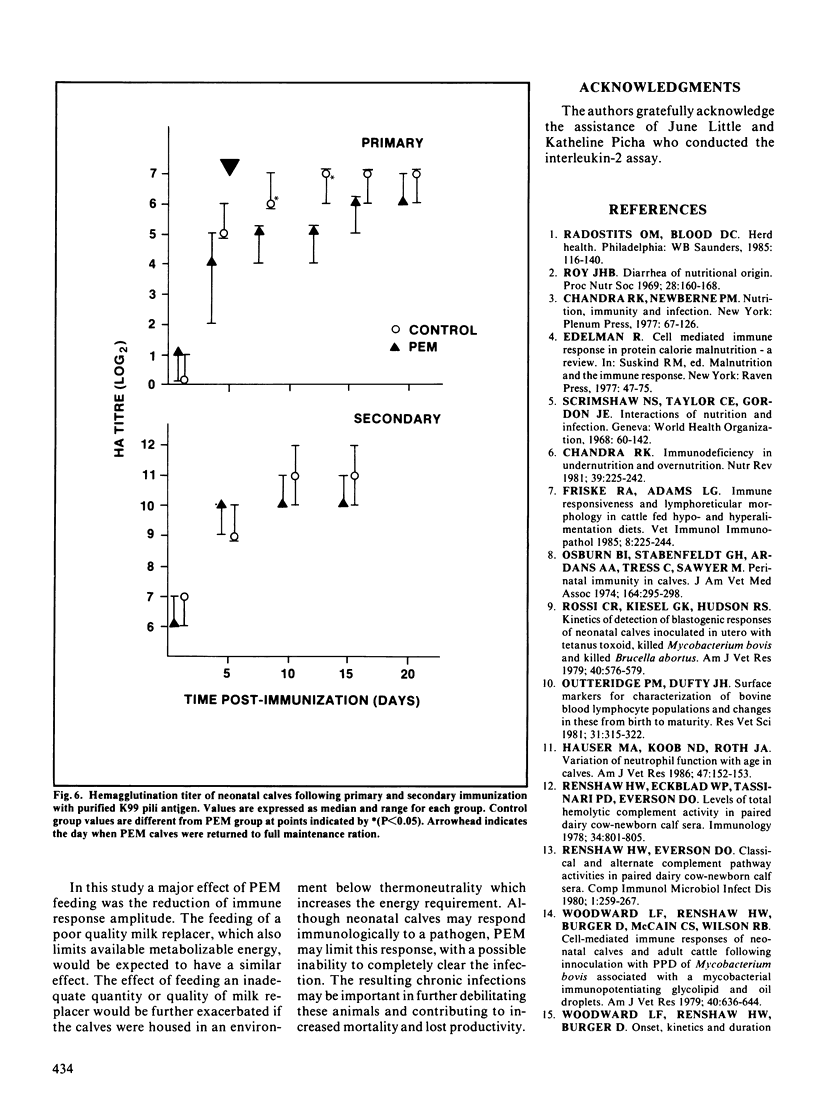

Immunocompetence of neonatal, Holstein bull calves fed for maximal growth (Control; n = 4) or protein energy malnutrition feeding (PEM; n = 4) for four weeks was assayed in vitro and in vivo. All calves exhibited elevated cortisol levels for ten days postnatally. At this time calves also were neutrophilic and lymphopenic. In addition lymphocyte function, as measured by lymphocyte proliferation and interleukin-2 activity, was reduced at this time as compared to older calves. After two weeks of protein energy malnutrition feeding, calves had significantly lower body weight, lymphocyte interleukin-2 activity and lymphocyte proliferation when compared with age-matched controls. Two weeks after protein energy malnutrition ration reversal, interleukin-2 activity and lymphocyte proliferation was comparable for both groups. There was no significant difference in serum cortisol concentration between control and protein energy malnutrition calves. The kinetics of the protein energy malnutrition group's primary humoral immune response was retarded, thus significantly lower antibody levels to K99 antigen were observed 8 to 12 days postimmunization. There was no significant difference between groups when comparing secondary response to K99 antigen.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Akana S. F., Cascio C. S., Shinsako J., Dallman M. F. Corticosterone: narrow range required for normal body and thymus weight and ACTH. Am J Physiol. 1985 Nov;249(5 Pt 2):R527–R532. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1985.249.5.R527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker P. E., Knoblock K. F. Bovine costimulator. II. Generation and maintenance of a bovine costimulator-dependent bovine lymphoblastoid cell line. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1982 Jul;3(4):381–397. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(82)90021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blecha F., Baker P. E. Effect of cortisol in vitro and in vivo on production of bovine interleukin 2. Am J Vet Res. 1986 Apr;47(4):841–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabello G. Neonatal changes in the plasma levels of cortisol, cortisone and aldosterone in the calf. Biol Neonate. 1979;36(1-2):35–39. doi: 10.1159/000241204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra R. K. Immunodeficiency in undernutrition and overnutrition. Nutr Rev. 1981 Jun;39(6):225–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1981.tb07446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra R. K. Numerical and functional deficiency in T helper cells in protein energy malnutrition. Clin Exp Immunol. 1983 Jan;51(1):126–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Däubener W., von Steldern D., Maxeiner B., Scheurich P., Pfizenmaier K. Postnatal development of functional T cell subsets in the mouse: a frequency analysis of mitogen reactive precursors of proliferating, of cytotoxic and of IL 2 producing T cells. Immunobiology. 1985 Jul;169(5):472–485. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(85)80003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart R. J., Patt J. A., Jr Plasma cortisol concentrations in newborn calves. Am J Vet Res. 1971 Dec;32(12):1921–1927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske R. A., Adams L. G. Immune responsiveness and lymphoreticular morphology in cattle fed hypo- and hyperalimentative diets. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1985 Feb;8(3):225–244. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(85)90083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossum C., Larsson B., Matsson P. Development of mononuclear cell subpopulations and their function during calfhood. Zentralbl Veterinarmed B. 1986 Sep;33(7):518–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1986.tb00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis S., Crabtree G. R., Smith K. A. Glucocorticoid-induced inhibition of T cell growth factor production. I. The effect on mitogen-induced lymphocyte proliferation. J Immunol. 1979 Oct;123(4):1624–1631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser M. A., Koob M. D., Roth J. A. Variation of neutrophil function with age in calves. Am J Vet Res. 1986 Jan;47(1):152–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osburn B. I., Stabenfeldt G. H., Ardans A. A., Trees C., Sawyer M. Perinatal immunity in calves. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1974 Feb 1;164(3):295–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outteridge P. M., Dufty J. H. Surface markers for characterisation of bovine blood lymphocyte populations and changes in these from birth to maturity. Res Vet Sci. 1981 Nov;31(3):315–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri S., Chandra R. K. Nutritional regulation of host resistance and predictive value of immunologic tests in assessment of outcome. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1985 Apr;32(2):499–516. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)34800-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purtilo D. T., Connor D. H. Fatal infections in protein-calorie malnourished children with thymolymphatic atrophy. Arch Dis Child. 1975 Feb;50(2):149–152. doi: 10.1136/adc.50.2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw H. W., Eckblad W. P., Tassinari P. D., Everson D. O. Levels of total haemolytic complement activity in paired dairy cow-newborn calf sera. Immunology. 1978 May;34(5):801–805. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw H. W., Everson D. O. Classical and alternate complement pathway activities in paired dairy cow--newborn calf sera. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 1979;1(4):259–267. doi: 10.1016/0147-9571(79)90027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosnek E. E., Brouwer M. C., Aarden L. A. T cell triggering by lectins. II. Stimuli for induction of interleukin 2 responsiveness and interleukin 2 production differ only in quantitative aspects. Eur J Immunol. 1985 Jul;15(7):657–661. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830150704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi C. R., Kiesel G. K., Hudson R. S. Kinetics of detection of blastogenic responses of neonatal calves inoculated in utero with tetanus toxoid, killed Mycobacterium bovis, and killed Brucella abortus. Am J Vet Res. 1979 Apr;40(4):576–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi C. R., Kiesel G. K., Hudson R. S., Powe T. A., Fisher L. F. Evidence for suppression or incomplete maturation of cell-mediated immunity in neonatal calves as determined by delayed-type hypersensitivity responses. Am J Vet Res. 1981 Aug;42(8):1369–1370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy J. H. Diarrhoea of nutritional origin. Proc Nutr Soc. 1969 Mar;28(1):160–170. doi: 10.1079/pns19690027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoonderwoerd M., Doige C. E., Wobeser G. A., Naylor J. M. Protein energy malnutrition and fat mobilization in neonatal calves. Can Vet J. 1986 Oct;27(10):365–371. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutman O. Intrathymic and extrathymic T cell maturation. Immunol Rev. 1978;42:138–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1978.tb00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutman O. Two main features of T-cell development: thymus traffic and postthymic maturation. Contemp Top Immunobiol. 1977;7:1–46. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-3054-7_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodard L. F., Renshaw H. W., Burger D., McCain C. S., Wilson R. B. Cell-mediated immune responses of neonatal calves and adult cattle following inoculation with PPD of Mycobacterium bovis associated with a mycobacterial immunopotentiating glycolipid and oil droplets. Am J Vet Res. 1979 May;40(5):636–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]