Abstract

The gene Rv1625c from Mycobacterium tuberculosis encodes a membrane-anchored adenylyl cyclase corresponding to exactly one-half of a mammalian adenylyl cyclase. An engineered, soluble form of Rv1625c was expressed in Escherichia coli. It formed a homodimeric cyclase with two catalytic centers. Amino acid mutations predicted to affect catalysis resulted in inactive monomers. A single catalytic center with wild-type activity could be reconstituted from mutated monomers in stringent analogy to the mammalian heterodimeric cyclase structure. The proposed existence of supramolecular adenylyl cyclase complexes was established by reconstitution from peptide-linked, mutation-inactivated homodimers resulting in pseudo-trimeric and -tetrameric complexes. The mycobacterial holoenzyme was expressed successfully in E.coli and mammalian HEK293 cells, i.e. its membrane targeting sequence was compatible with the bacterial and eukaryotic machinery for processing and membrane insertion. The membrane-anchored mycobacterial cyclase expressed in E.coli was purified to homogeneity as a first step toward the complete structural elucidation of this important protein. As the closest progenitor of the mammalian adenylyl cyclase family to date, the mycobacterial cyclase probably was spread by horizontal gene transfer.

Keywords: adenylyl cyclases/bacterial–eukaryotic expression/catalysis/evolution/Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a dreadful intracellular pathogen that presently causes more deaths than any other single pathogen (Snider et al., 1994; Murray and Salomon, 1998). The tubercle bacillus survives the entry into mammalian cells, mainly mononuclear phagocytes, monocytes and macrophages, which usually are designed to destroy bacteria, and causes a persistent and chronic infection. Undoubtedly, a variety of cross-talk modalities must exist between the mammalian host and its invasive pathogen, with the result that the host’s defenses can be bypassed and the pathogen’s disguises are maintained during its proliferation. Moreover, M.tuberculosis shows considerable plasticity to switch its metabolism and exploit different carbon sources that become available during the course of infection. Surprisingly little is known about the chemical nature of this host–pathogen communication, and the bacterial signal transduction pathways involved in the regulation and response to changing environments remain elusive. This extends even to one of the most universal communication systems, the cyclic nucleotide second messenger cascades (Padh and Venkitasubramanian, 1980; Bhatnagar et al., 1984; Shankar et al., 1997).

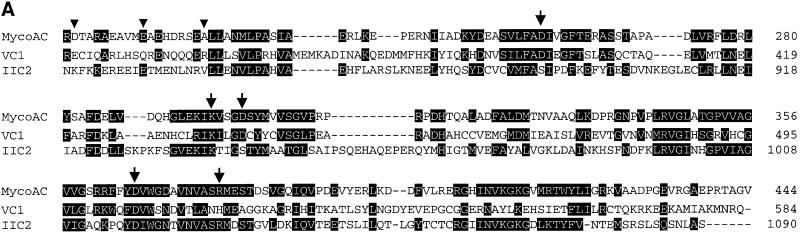

In 1998, the complete genome sequence of M.tuberculosis H37Rv was reported (Cole et al., 1998). Thus, genes of interest are now easily accessible by PCR using specific primers and genomic DNA as a template. Proteins may then be expressed and studied biochemically in detail. In the M.tuberculosis genome, 15 open reading frames (ORFs) have been identified which probably code for functional class III adenylyl cyclases (ACs; Cole et al., 1998; McCue et al., 2000). These cyclase isozymes belong to evolutionarily segregated branches. Nine are predicted to be similar to ACs found in Streptomyces, and four appear to be similar to ACs identified in bacteria such as myxobacterium Stigmatella aurantiaca (McCue et al., 2000). Two genes, Rv1625c and Rv2435c, code for proteins that are grouped with the mammalian ACs on a branch separate from other prokaryotic cyclases. The predicted protein of Rv1625c has a molecular mass of 47 kDa. It consists of a large N-terminal membrane domain, which is made up of six transmembrane spans, and a single C-terminal catalytic domain (Tang and Hurley, 1998). As such, the predicted protein topology corresponds exactly to one-half of a mammalian membrane-bound AC, which is a pseudoheterodimer composed of two highly similar domains linked by a peptide chain designated as C1b (Tang and Hurley, 1998; see model in Figure 1B). The mycobacterial catalytic domain displays considerable sequence identities with those of mammalian ACs (Figure 1A). This unexpected and so far unique similarity of a bacterial AC to mammalian ACs raises questions about their evolutionary and functional relationship and the pathophysiological role of this M.tuberculosis version of a mammalian AC. Additionally, the cloned gene Rv1625c opens up novel experimental opportunities because, as shown here, the full-length, membrane-bound AC can be expressed actively in mammalian HEK293 cells as well as in Escherichia coli. We report on the expression and characterization of the catalytic center of gene Rv1625c product from M.tuberculosis and address the question of a functional tetrameric structure of ACs as crystallized by Zhang et al. (1997). All molecular and biochemical properties of the mycobacterial AC monomer Rv1625c indicate that it may constitute a direct progenitor to the mammalian pseudoheterodimeric ACs, possibly acquired during evolution by eukaryotic cells from bacteria via a horizontal gene transfer event (Baltimore, 2001).

Fig. 1. (A) Alignment of the catalytic domains of the mycobacterial adenylyl cyclase with C1 from canine type V (VC1) and C2 from rat type II (IIC2) adenylyl cyclases (residues shared with either mammalian sequence are inverted). The triangles indicate D204, E213 and A221 as starting points of the cytosolic constructs. The arrows mark the mutated amino acids (to alanine) that are involved in substrate definition (K296 and D365), coordination of metal ions (D256 and D300) and transition state stabilization (R376). Note that in the mammalian domains, the equivalents of D256 and D300 are contributed by C1 whereas D365 and R376 are contributed by C2. (B) Predicted topology of the pseudoheterodimeric mammalian adenylyl cyclases (left) and the monomeric mycobacterial AC. M designates a membrane cassette of six transmembrane spans. In the mycobacterial enzyme, the homodimerization is intimated by a sketchy second M domain. (C) Symbolized homodimeric catalytic center of the mycobacterial adenylyl cyclase capable of forming two catalytic sites. D256, D300 and R376 are outlined; binding of the adenine ring A is indicated by dotted lines. (D and E) Proposed homodimeric structure of the (D) D300A and (E) R376A mutants. (F) Symbolized heterodimer with a single catalytic site reconstituted from the D300A and R376A mutant monomers. The same model may be applied to the D256A mutation (not depicted). P = phosphate; Me = divalent metal cation.

Results

Sequence analysis of the Rv1625 adenylyl cyclase

The M.tuberculosis gene Rv1625c (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. AF017731) codes for an AC (mycoAC) with six putative transmembrane helices as a membrane anchor and a single catalytic domain (M and C; Figure 1B; Tang and Hurley, 1998). In contrast, the mammalian membrane-bound ACs consist of two different cytoplasmic catalytic domains (C1a,b and C2), each following a transmembrane segment with six α-helices (M1 and M2; Figure 1B) (Krupinski et al., 1989; Sunahara et al., 1996; Tang and Hurley, 1998). Thus, mammalian ACs are pseudoheterodimers. An alignment of the single mycobacterial catalytic loop with the mammalian C1a or C2 catalytic segments revealed extensive similarities (Figure 1A). The identity to C1a from canine AC type V was 30% (73 of 241 amino acids); with conservative replacements, the similarity was 40%. Similar values were obtained in a comparison with C2 from rat AC type II; 31% identity (75 of 241) and 45% similarity [rat type II and canine type V ACs were chosen because these domains were used in the available X-ray structures (Tesmer et al., 1997, 1999; Zhang et al., 1997)]. The single catalytic domain of the mycoAC contains each of the amino acids in-register that have been identified crystallographically as participating in catalysis, i.e. in the definition of substrate specificity (K296 and D365), in the coordination of two metal ions (D256 and D300) and in transition state stabilization (R376). In mammalian ACs, these amino acids are contributed either from the C1 domain (D396 and D440 in canine AC type V for metal coordination) or from the C2 segment (K938 and D1018 for binding to N1 and N6 of the adenine moiety and R1029 to stabilize the transition state in rat AC type II). The gaps of four, three and 11 amino acids in the alignment with the C2 domain possibly indicate a closer kinship of the mycobacterial catalytic loop to the mammalian C1a units. Notably, the 11 amino acid gap excludes the QEHA motif, which has been proposed to bind the β,γ subunits of G-proteins (Chen et al., 1995). In the canonical mammalian ACs, dimerization of the cyclase homology domains is required to form the catalytic pocket at the domain interface. Thus, the mycobacterial monomer probably functions as a C1 as well as a C2 catalytic domain in a homodimer which may form two competent catalytic sites (symbolized in Figure 1C).

Characterization of a soluble mycobacterial AC homodimer

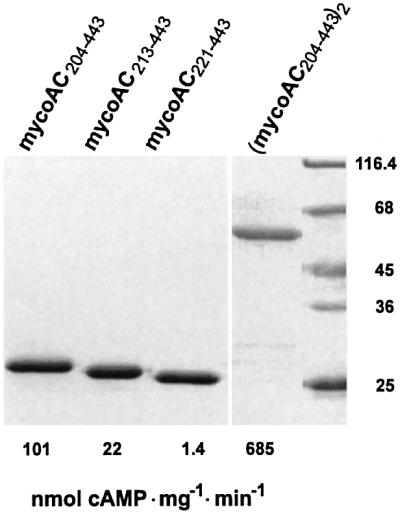

First we constructed three cytosolic segments of different lengths to generate a soluble, enzymatically active catalytic domain from mycoAC (Tang and Gilman, 1995; Whisnant et al., 1996; Yan et al., 1996). The N-terminally His-tagged constructs, which started at D204, i.e. at the calculated exit of the last transmembrane span, at E213 and at A221 (marked in Figure 1A), were expressed in E.coli and purified to homogeneity by Ni-NTA chromatography (Figure 2). At 750 nM protein, the AC activities were 101, 22 and 1.4 nmol cAMP/mg/min (100, 22 and 1.4%), respectively, i.e. the activities declined upon shortening of the N-terminus ahead of F254, the presumed beginning of the catalytic core. Therefore, mycoAC204–443 was used for further investigations.

Fig. 2. Purification and activity of recombinant mycobacterial adenylyl cyclase catalytic domains (SDS–PAGE analysis, Coomassie blue staining). The soluble cytoplasmic domains started at D204 (mycoAC204–443), E213 (mycoAC213–443) and A221 (mycoAC221–443) as indicated in Figure 1A. The specific activities indicated below each lane were determined with 75 µM ATP at a protein concentration of 2 µg/assay (750 nM). The dimer (mycoAC204–443)2 was assayed at 0.6 µg protein/assay (110 nM).

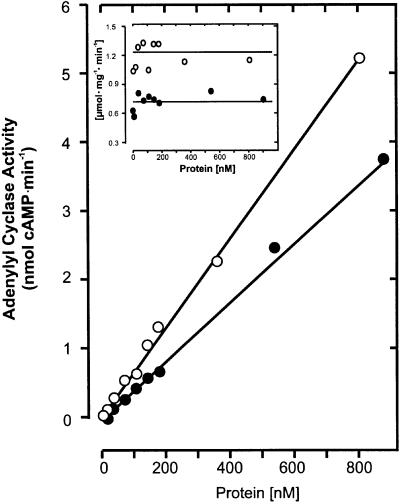

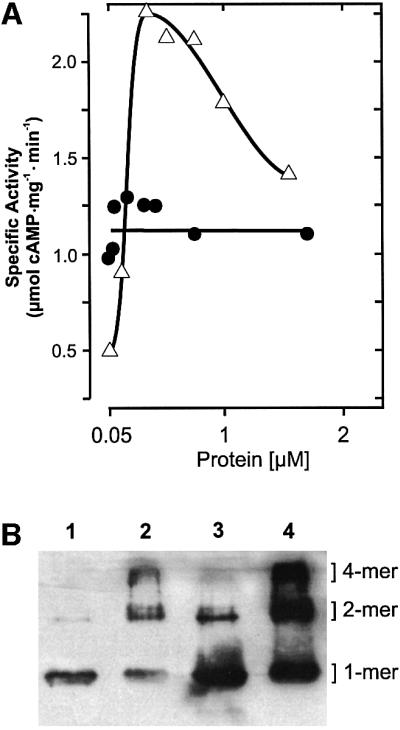

The specific activity of mycoAC204–443 was dependent on the protein concentration. From 50 to 300 nM, it increased 5-fold, suggesting the formation of a homodimer (Figure 3A). Further increments in the protein concentration resulted in a decrease of the specific activity (Figure 3A). The dimerization was substantiated with a construct in which two monomers were joined by a flexible tetradekapeptide linker (mycoAC204–443)2. The dimer was expressed in E.coli and purified by Ni-NTA chromatography (Figure 2). The specific activity of (mycoAC204–443)2 was independent of the protein concentration (Figure 3A). We reasoned that the decreasing activity of the monomer at protein concentrations >300 nM might have been caused by the formation of less productive multimers. Therefore, mycoAC204–443 at 0.3 and 2 µM concentrations was treated with the cross-linking reagent glutaraldehyde (20 mM), and protein multimerization was analyzed by western blotting (Figure 3B). The extent of the oligomerization that was substrate independent (not shown) was dependent on the protein concentration, i.e. differences in the oligomeric state may, at least in part, be responsible for the decreasing AC activity at higher protein concentrations.

Fig. 3. (A) Protein dependence of mycoAC204–443 (open triangles) and linked (mycoAC204–443)2 (filled circles) activity (850 µM Mn-ATP, 4 min). (B) Western blot analysis of mycoAC204–443 oligomers cross-linked by 20 mM glutaraldehyde. Lane 1, 300 nM mycoAC204–443 (0.24 µg protein), no glutaraldehyde; lane 2, + 20 mM glutaraldehyde; lane 3, 2 µM mycoAC204–443 (1.6 µg protein), no glutaraldehyde; lane 4, + 20 mM glutaraldehyde. Densitometric evaluation (lanes 1–4): the monomers accounted for 96, 31, 80 and 30%, the dimers for 4, 44, 18 and 33%, and the tetramers for 0, 25, 2 and 37%, respectively.

The kinetic properties of mycoAC204–443 and (mycoAC204–443)2 were analyzed using Mn2+ or Mg2+ (Table I). The Km values for ATP were considerably lower with Mn2+ compared with Mg2+. Similarly, the Vmax values were highest with Mn-ATP as a substrate, with the linked dimer showing a considerably higher value (Table I). The pH optimum (7.2; tested range pH 4–9.5), the temperature optimum (37°C) and the activation energy derived from a linear Arrhenius plot (67.5 kJ/mol; tested range 0–60°C) were similar to the constants reported for the mammalian AC catalysts. The Hill coefficients indicated a slight cooperativity for the linked construct. Mn-GTP was not accepted as a substrate. Not surprisingly, 100 µM forskolin did not activate the mycoAC204–443. Forskolin efficiently activates most membrane-bound mammalian ACs by binding to a pseudosymmetric substrate-binding site, which in the mycoAC is probably part of a second catalytic site (Tesmer et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 1997).

Table I. Kinetic characterization of the mycoAC monomer and peptide-linked dimer.

| Enzyme | MycoAC204–443 |

(MycoAC204–443)2 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 mM Mn2+ | 20 mM Mg2+ | 2 mM Mn2+ | 20 mM Mg2+ | |

| Km(ATP) (µM) | 150 | 417 | 54 | 400 |

| Vmax (nmol/mg/min) | 2100 | 27 | 3600 | 73 |

| Hill coefficient | 1.1 | 0.98 | 1.63 | 1.35 |

Assays were conducted at 288 nM (monomer) and 36 nM (dimer) of protein when using Mn2+ as a cation (for Mg2+, the protein concentrations were 4.4 µM and 196 nM, respectively).

Generation of an active heterodimeric from a homodimeric AC

The crystal structure of the mammalian AC heterodimer predicts which amino acids of the mycoAC ought to be involved in catalysis (Liu et al., 1997; Tesmer et al., 1997, 1999; Yan et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 1997; Sunahara et al., 1998). In Figure 1C, part of this information has been modeled for a mycobacterial AC homodimer. From such a model, testable predictions can be derived. First, the mycoAC should be capable of forming two catalytically productive sites. Secondly, all single mutations of the amino acid residues outlined above should be largely inactivating. Thirdly, any reconstitution of a productive heterodimer from inactive mutated monomers should be restricted to those combinations that enable a mammalian C1–C2-like situation and result in the reconstitution of only a single catalytic site (as modeled in Figure 1F). These possibilities were examined.

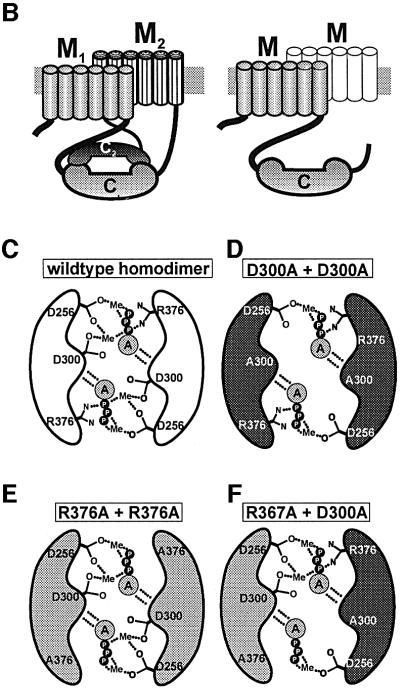

In the soluble mycoAC204–443, we individually mutated D256, K296, D300, D365 and R376 to alanines. The constructs were expressed in E.coli and purified to homogeneity (Figure 4). The mutant proteins had residual AC activities of <5% of the wild-type monomer when compared under identical assay conditions (Figure 4, see also Figure 5). Therefore, they were suitable to investigate by reconstitution experiments the formation of the catalytic fold in analogy to a mammalian C1–C2 arrangement. Point mutations that targeted the same functional subdomain and excluded the assembly of a mammalian C1–C2-like heterodimer could not reconstitute each other effectively (Table II). Further, mutants that targeted the substrate recognition site, mycoAC204–443K296A and mycoAC204–443D365A, reconstituted to a limited extent only (Table II).

Fig. 4. SDS–PAGE analysis of purified mycoAC204–443 mutant constructs (Coomassie blue staining). Molecular mass standards are on the left. The following amounts of protein were applied (left to right): D256A, 4 µg; K296A, 1.5 µg; D300A, 4 µg; D365A, 2 µg; R376A, 2.3 µg; D300A-L-D300A, R376A-L-R376A and R376A-L-D300A, 4 µg each. The specific AC activities determined at 75 µM Mn-ATP and 4 µM protein are indicated below each lane (114 nM for R376A-L-D300A).

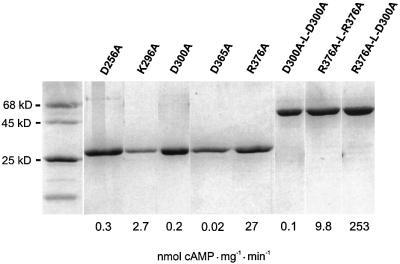

Fig. 5. Reconstitution of mycobacterial adenylyl cyclase activity from the D256A, D300A and R376A mutants. (A) Protein dependency of R376A activity. The protein concentration marked by the filled circle (45 nM) was used in (B) for reconstitution with increasing amounts of D256A (open triangles) and D300A (filled circles); D256A (filled triangles) and D300A (open circles) alone. Note the different scales (assays with 850 µM Mn-ATP, 4 min).

Table II. AC reconstitution in pairs from point-mutated mycoAC monomers.

| Protein concentration |

Activity (pmol cAMP/min) | |

|---|---|---|

| 4 µM | 45 nM | |

| K296A (C1) | 30 | |

| + D256A (C2) | 86 | |

| + D300A (C2) | 46 | |

| + D365A (C1) | 28 | |

| + R376A (C1) | 29 | |

| D365A (C1) | 0.2 | |

| + D256A (C2) | 3.6 | |

| + D300A (C2) | 0.7 | |

| + R376A (C1) | 1.7 | |

| D300A (C2) | 2.6 | |

| + D256A (C2) | 2.8 | |

The functional analogies to the C1 and C2 catalytic domains of mammalian ACs are in parentheses.

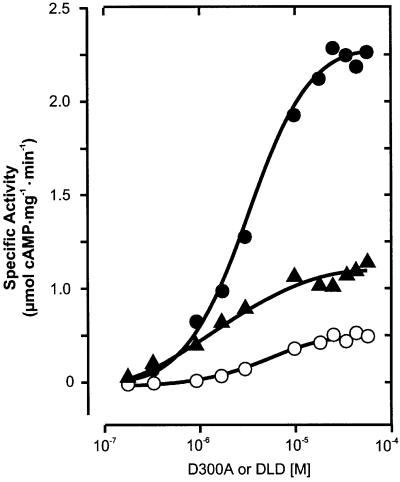

In contrast, AC reconstitution to almost wild-type levels was encountered when mixing mycoAC204–443R376A with either mycoAC204–443D256A or mycoAC204–443 D300A because these amino acids contribute to the catalysis from different protein domains, very much like in a C1–C2 complex. A protein dose–response curve of mycoAC204–443R376A showed that it had no detectable AC activity up to 1 µM (Figure 5A). Above this concentra tion, a very small amount of AC activity was detectable (Figure 5A). MycoAC204–443D256A and mycoAC204–443 D300A were essentially inactive up to 55 µM protein (Figure 5B). We then used 45 nM mycoAC204–443R376A, an inactive protein concentration serving as a mammalian C1-like analog (filled circle in Figure 5A), and added increasing amounts of mycoAC204–443D300A as a presumptive C2 analog (Figure 5B). A highly active enzyme was reconstituted in analogy to a C1–C2 heterodimer as symbolized in Figure 1F. Plotting the concentration of mycoAC204–443D300A versus AC activity, we derived an apparent Vmax value for the rate-limiting amount of mycoAC204–443R376A of 2.2 µmol cAMP/mg/min. The apparent Kd value of 2 µM for the mycoAC204–443D300A/mycoAC204–443R376A couple was independent of the ATP concentration in the assay, indicating that the association of the monomers was not substrate mediated (not shown). The same type of experiment was carried out with the mycoAC204–443D256A mutant serving as a C2 analog (Figure 5B). Again, we were able to reconstitute activity with mycoAC204–443R376A. The Kd was 2 µM and the apparent Vmax for the rate-limiting amount of mycoAC204–443R376A was 2.1 µmol cAMP/mg/min. Obviously, the 500- to 1000-fold excess of mycoAC204–443 D256A or mycoAC204–443D300A over mycoAC204–443 R376A resulted in the quantitative formation of a productive heterodimeric complex.

Evidence for active pseudo-trimeric and -tetrameric AC species

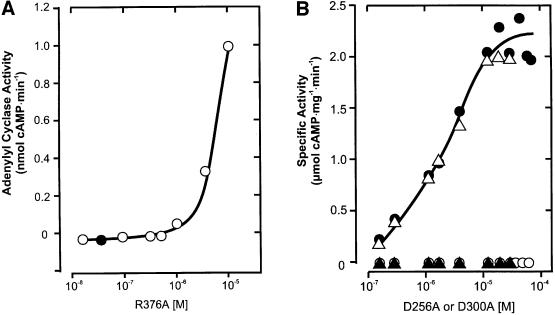

The membrane-bound mammalian ACs are pseudoheterodimers in which the C1 and C2 domains are derived from an intramolecular association. Crystallographically, a tetrameric C2 structure has been reported (Zhang et al., 1997). The relevance of this tetramer remained unresolved because it has not been possible to examine the possibility of an intermolecular association experimentally, i.e. the formation of catalytic centers by an association of C1 and C2 domains originating from different AC proteins. With the available mycoAC mutant proteins, such a possibility could be tested. We generated mutated homodimers linked by a tetradekapeptide chain, i.e. mycoAC204–443R376A-TRAAGGPPAAGGLE-mycoAC204–443R376A (R376A-L-R376A), D300A-L-D300A and R376A-L-D300A. The constructs were expressed in E.coli and affinity purified to homogeneity (Figure 4). D300A-L-D300A was enzymatically dead, R376A-L-R376A had residual activity and R376A-L-D300A was highly active (Figure 4). R376A-L-D300A supposedly can form a single catalytic center (Figure 1F). The Km for Mn-ATP was 72 µM, the Vmax was 1.6 µmol cAMP/mg/min and the Hill coefficient was 0.98. As observed with the (mycoAC204–443)2 homodimer, the protein dependency of the R376A-L-D300A heterodimer was linear and the specific activity was constant over the tested range of protein concentrations from 5 to 800 nM (Figure 6). The specific activity of R376A-L-D300A was 65% of (mycoAC204–443)2 (1.100 ± 41 versus 722 ± 25 nmol cAMP/mg/min; SEM, n = 9; Figure 6). This is convincing evidence that in the linked wild-type homodimer two positive cooperative catalytic centers (Hill coefficient 1.68) are formed and only one in the internally complementing mutant protein R376A-L-D300A (Hill coefficient 0.98).

Fig. 7. Intermolecular formation of adenylyl cyclase catalysts from mutated, inactive monomers and homodimers. Filled circles: 45 nM R376A (inactive) titrated with increasing amounts of D300A-L-D300A (DLD). Filled triangles: 36 nM R376A-L-R376A titrated with D300A. Open circles: 36 nM R376A-L-R376A titrated with D300A-L-D300A. Assays were carried out with 850 µM Mn-ATP as a substrate for 4 min. The specific activity was calculated on the basis of the fixed concentration of the minor constituent.

We then investigated whether R376A-L-R376A could be competed by the mycoAC204–443D300A monomer or even the D300A-L-D300A dimer with reconstitution of catalytic sites. A concentration of 36 nM R376A-L-R376A, which is inactive, was partially reactivated in a dose-dependent fashion by increasing amounts of mycoAC204–443D300A (Figure 7). Similarly, 36 nM R376A-L-R376A was partially reconstituted by increasing concentrations of D300A-L-D300A. We thus proved that even the mutated dimers interacted productively and formed a competent catalytic complex with a pseudo-trimeric and -tetrameric entity (Figure 7). Conversely, we found that 45 nM R376A could be reactivated by increasing amounts of the D300A-L-D300A dimer to form a functional AC catalytic center with a specific activity comparable to wild-type levels (Figure 7). From the dose–response curves, apparent Kd values in the range of 2–4 µM were derived. These Kd values were identical to those determined for the mutated monomer pairs (Figure 5B). The differences in the extent of the reconstitution are not apparent at this point. Perhaps un appreciated conformational peculiarities of individual constructs may be involved.

Fig. 6. One and two catalytic centers formed by (mycoAC204–443)2 (open circles) and R376A-L-D300A (filled circles), respectively, demonstrated by the linearity of the protein dependences and the unchanging specific activities. Inset: specific activity (same symbols; 850 µM Mn-ATP, 4 min).

Expression of the membrane-bound mycoAC in E.coli and HEK293 cells

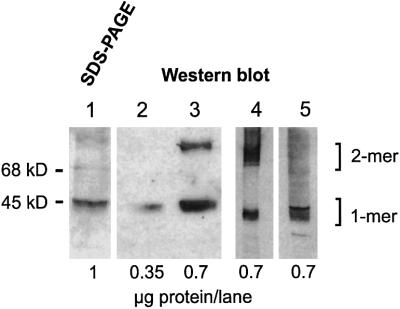

Obviously, M.tuberculosis carries the information for a mammalian type AC that requires membrane targeting. We attempted to express the mycoAC holoenzyme, i.e. including its huge membrane anchor, in E.coli as well as in mammalian HEK293 cells. To date, no bacterial AC has been expressed in a mammalian cell, and the bacterial expression and successful membrane targeting of a mammalian membrane-bound AC holoenzyme have not been reported. For expression in E.coli, the mycoAC ORF was cloned into pQE30 adding an N-terminal His6 tag. After transformation and induction, a bacterial membrane preparation yielded a high AC activity (19 nmol cAMP/mg/min), indicating expression and successful dimerization in the bacterial membrane. This was demonstrated by a western blot because a substantial amount of the protein remained dimerized during SDS–PAGE (Figure 8). In the soluble fraction of the bacterial lysate, no AC activity was detectable. The mycoAC was solubilized from the bacterial membrane with 1% polydocanol as a detergent and purified to homogeneity. SDS–PAGE analysis yielded a single, somewhat fuzzy band typical of a membrane protein at 46 kDa, and a faint band at 92 kDa representing a dimer (Figure 8). A band at 92 kDa was consistent with the presence of the homodimer (Figure 8). The purified holoenzyme had a specific activity of 1.2 µmol cAMP/mg/min using 75 µM Mn-ATP as a substrate.

Fig. 8. Electrophoretic analysis (SDS–PAGE and western blot) of the mycobacterial adenylyl cyclase holoenzyme. Lane 1, Coomassie blue-stained SDS–PAGE of purified enzyme expressed in E.coli; lanes 2 and 3, western blot of purified protein probed with antibodies against the N-terminal His tag. Note the distinct 92 kDa band in lane 3 demonstrating a homodimer. Escherichia coli (lane 4) and HEK293 homogenates (lane 5) expressing the holoenzyme were probed with an antibody directed against mycoAC204–443.

The mycobacterial protein could also be functionally expressed in stably transfected mammalian HEK293 cells. HEK293 membranes had an activity of 65 nmol cAMP/mg/min compared with 24 pmol cAMP/mg/min in the vector control. The Km for Mn-ATP was 65 µM. The robust expression of mycoAC in HEK293 cells was also detected by a western blot using an antibody against the cytosolic portion of the protein (Figure 8). A dimerized protein was not detected in HEK293 cells after SDS–PAGE, possibly due to the different lipid composition of bacterial and mammalian cell membranes. We thus established that the monomeric mycobacterial AC Rv1625c not only sequentially and topologically resembled a mammalian, membrane-bound, pseudoheterodimeric AC, but it could also be expressed, processed and correctly membrane targeted successfully by mammalian cells.

Discussion

The availability of genomic DNA sequences greatly advances our understanding of infectious diseases and microbial pathogenesis, yet the significance of each gene can only be learned from the individual expression products because proteins carry out most biochemical reactions. In the mycobacterial genome, 15 putative ACs are detected (Cole et al., 1998; McCue et al., 2000). This unique situation implies that the resulting signal transduction modalities using cAMP as a second messenger are of great importance to the tubercle bacillus. Although it has been reported that in macrophages with ingested mycobacteria cAMP levels are elevated and the phagosome– lysosome fusion is impaired, at this point it remains to be demonstrated in which function any of the mycobacterial cyclases may be required for pathogenesis (Lowrie, 1978). We chose to investigate the protein product of Rv1625c because of its surprising topological identity and sequence similarity to mammalian membrane-bound ACs. The sequence-derived insights are now covered by the biochemical properties of the expressed protein. Dimerization was a prerequisite and sufficient for formation of the catalytic center. The molecular details were in agreement with the crystallographic description of a mammalian heterodimeric catalytic fold, as evident from the studies with single amino acid mutants and from the reconstitution experiments. Because the mycoAC is most probably a symmetric homodimer, two identical and equivalent catalytic sites are generated. We assume that the measured activity represented that of a basal state. This leaves the question of its regulation in the bacillus to be resolved. One possibility is that the mycoAC uses intermediary proteins like the mammalian ACs. The presence in mycobacteria of proteins resembling the α-, β- and γ-subunits of mammalian G-proteins has been suggested (Shankar et al., 1997), yet an evaluation of the mycobacterial genome has not uncovered proteins with evident structural similarities. Therefore, the molecular nature of these proteins remains to be defined. A plausible regulatory input to the membrane-anchored mycoAC may come from lipids of the complex mycobacterial cell envelope because they may affect the monomer/dimer ratio and thus the AC activity in the pathogen.

In the mammalian heterodimer, forskolin binds to the catalytic core at the opposite end of the same ventral cleft that contains the active site. Thr410 and Ser942 (rat type II AC numbering) are implicated in forskolin binding (Tesmer et al., 1997). The correspondingly located amino acids in the mycoAC are Asp300 and Asn372 (Figure 1A). These two amino acids are a prerequisite for the formation of a second substrate-binding site and probably are responsible for the observed lack of a forskolin effect in the mycobacterial AC. Actually, the elimination of the second substrate-binding site in the mammalian ACs and its replacement by a regulatory site renews the question about the presence of an elusive endogenous forskolin-like molecule in eukaryotes.

Several experimental observations have posed the question of whether the pseudoheterodimeric mammalian AC might exist as a true dimer. A tetrameric X-ray structure was observed with the cytosolic C2 segment (Zhang et al., 1997). Further, target size (Rodbell et al., 1981) and hydrodynamic analysis (Haga et al., 1977; Yeager et al., 1985) showed possible monomer/dimer transitions of the mammalian pseudoheterodimers, and immunoprecipitation of recombinant type I AC yielded a functional oligomer (Tang et al., 1995). With the soluble constructs from mammalian ACs, it was impossible to address the question of a potential true dimerization of two pseudoheterodimers. We were able to carry out a first biochemical test using linked mutation-inactivated homodimers that were complementary to each other. Biochemically, we demonstrated the formation of catalytic centers within pseudo-trimeric and -tetrameric structures. The findings are consistent with the possibility of tetramers or higher order structures in mammalian ACs. Such processes could add additional levels of AC regulation in eukaryotic cells.

What is the evolutionary relationship of mycoAC Rv1625c and the mammalian, membrane-bound ACs? The current data are compatible with the earlier hypothesis that initially membrane-anchored monomers formed a homodimeric AC and that independent evolution led to heterodimeric ACs in eukaryotes (Linder et al., 1999). In fact, the spectacular degree of similarity in sequence, topology and biochemical properties of ACs from such distant organisms suggests a possible horizontal gene transfer event because they must have evolved from a common ancestor. The newly elucidated human genome shows that bacterial genomes can be direct donors of genes to vertebrates (Baltimore, 2001). This does not imply that mycobacteria were the actual donors of a progenitor gene for mammalian ACs (Kasahara et al., 2001). It is thought that mycobacteria arose from a soil bacterium. In view of the genetic stability of the M.tuberculosis complex, which lacks interstrain diversity and rarely has nucleotide changes, the properties of the AC progenitor that was actually transferred from bacteria to eukaryotes may have been largely conserved in the mycoAC Rv1625c gene (Cole et al., 1998). This hypothesis is supported by the highly surprising finding that the mycoAC gene could be expressed directly equally well in E.coli and in mammalian HEK293 cells (Figure 8). This attests to the fact that the as yet unknown membrane-targeting signal of this mycobacterial membrane-bound enzyme is compatible with the bacterial as well as the eukaryotic facilities for targeting, transport and insertion into the respective cell membrane. This was not at all self-evident. For example, the potassium-selective prokaryotic glutamate receptor from Synechocystis had to be fitted for eukaryotic expression with 31 N-terminal amino acids of the rat glutamate R6 receptor including a 5′-untranslated region (Chen et al., 1999). Taken together, the data are consistent with the view that this protein served as a progenitor of the mammalian pseudoheterodimeric AC family. A potential retrograde capture of this AC by the pathogen is considered less likely in view of the occurrence of the class III AC catalyst in distant bacteria (e.g. in the cyanobacterium Spirulina; Kasahara et al., 2001).

Finally, bacterial membrane proteins provide attractive systems for structural characterization of homologs of integral membrane proteins present in eukaryotes. This has been demonstrated convincingly with examples such as the bacterial rhodopsin (Deisenhofer et al., 1985), the potassium channel from Streptomyces (Chen et al., 1999) and the mechanosensitive channel from M.tuberculosis (Chang et al., 1998). The expression in E.coli and purification of the mycobacterial homolog of a mammalian AC, including its membrane anchor, may be seen as the first step toward a structural elucidation of this important protein.

Materials and methods

Recombinant cDNAs

Genomic DNA from M.tuberculosis was a gift of Dr Boettger, Medical School, Hannover, Germany. The mycoAC gene Rv1625c was amplified by PCR using specific primers and genomic DNA as a template. A BamHI restriction site was added at the 5′ end and a SacI site at the 3′ end. The DNA was inserted either into the multiple cloning site of pQE30 (Qiagen) with the N-terminal addition of a MRGSH6GS peptide sequence or into pQE60, which added a C-terminal histidine tag. In conjunction with specific primers, this clone served as a template to generate by PCR three DNA constructs comprising the catalytic C-terminus starting at D204 (mycoAC204–443), E213 (mycoAC213–443) or A221 (mycoAC221–443). After partial restriction of the products with BamHI and SacI, the fragments were ligated into pQE30.

Two catalytic mycoAC204–443 segments were linked (C- to N-terminal) via the insertion of a DNA sequence coding for the peptide linker TRAAGGPPAAGGLE using conventional molecular biology techniques. Thus, a pQE30 plasmid was generated that coded for the protein MRGSH6GS-mycoAC204–443-TRAAGGPPAAGGLE-mycoAC204–443, abbreviated (mycoAC204–443)2.

Single amino acid mutations in the catalytic domain of the mycoAC (D256A, K296A, D300A, D365A and R376A) were introduced by site-directed mutagenesis using respective PCR primers and the DNA coding for mycoAC204–443 as a template. Nearby restriction sites were used as appropriate. The fidelity of all constructs was verified by double-stranded sequencing. The sequences of all primers are available on request.

Expression and purification of bacterially expressed proteins

The constructs in the pQE30 expression plasmid were transformed into E.coli BL21(DE3)[pREP4]. For the holoenzyme, the cya- strain DHP1[pREP4] was used. Cultures were grown in Lennox L broth at 25°C containing 100 mg/l ampicillin and 25 mg/l kanamycin, and induced with 30 µM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside at an A600 of 0.4. Bacteria were harvested after 3 h, washed once with 50 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM EDTA pH 8 and stored at –80°C. For purification, frozen cells were suspended in 20 ml of cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol pH 8) and sonicated (3 × 10 s). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (48 000 g, 30 min). To the supernatants, 200 µl of nickel-NTA slurry (Qiagen) were added. After gentle rocking for 30 min at 0°C, the resin was poured into a column and washed (2 ml/wash: wash buffer A: 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM MgCl2, 400 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole; wash buffer B: wash buffer A with 15 mM imidazole; wash buffer C: wash buffer A with 10 mM NaCl and 15 mM imidazole). Proteins were eluted with 0.5–1 ml of buffer C containing 150 mM imidazole. Because the mycoAC was inhibited by >1 mM imidazole, the eluates were dialyzed overnight against 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM NaCl and 20% glycerol. The purified proteins could be stored in dialysis buffer at 4°C.

Expression of mycoAC in HEK293 cells

For expression of the mycoAC in HEK293 cells, the coding region in pQE60 (Qiagen) containing an RGSH6 sequence at the C-terminus was excised from pQE60 with NcoI and HindIII, filled in and cloned into the EcoRV site of pIRES1neo (Clontech). HEK293 cells were grown at 37°C in minimum essential medium (Gibco-BRL #31095-029) containing 10% fetal calf serum and 20 µg/ml gentamicin sulfate. For transfection, the calcium phosphate method was used with 10 µg of plasmid DNA/10 cm dish (Kingston et al., 1992). Cells were selected with 800 µg/ml G418 starting 3 days after transfection. After 10 days, the surviving cells were propagated in the presence of 400 µg/ml G418.

For membrane preparation, cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, suspended and lysed in 250 µl of buffer (20% glycerol, 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 1% thioglycerol, 1 mM EDTA and 1 mM benzamidine; two freeze–thaw cycles). The suspension was diluted with 4 vols of buffer (without glycerol) and sonicated (3 × 10 s, microtip setting 4). After removal of nuclei and debris (6000 g), membranes of HEK293 cells were pelleted at 50 000 g for 30 min.

Adenylyl cyclase assay

Adenylyl cyclase activity was measured for 10 min in a final volume of 100 µl (Salomon et al., 1974). The reactions contained 22% glycerol, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, either 2 mM MnCl2 or 20 mM MgCl2, the indicated concentrations of [α-32P]ATP (25 kBq) and 2 mM [2,8-3H]cAMP (150 Bq). Creatine phosphate (3 mM) and 1 U of creatine kinase were used as an ATP-regenerating system when assaying crude extracts. To determine kinetic constants, the concentration of ATP was varied from 10 to 550 µM with a fixed concentration of 2 mM Mn2+ or 20 mM Mg2+. Assays were pre-incubated at 30°C for 5 min (37°C with HEK293 membranes) and the reaction was started by the addition of enzyme. Usually, <10% of the ATP was consumed at the lowest substrate concentrations.

Western blot analysis

Protein was mixed with sample buffer and subjected to SDS–PAGE (15%). Proteins were blotted onto PVDF membranes and sequentially probed with a commercial anti-RGS-His4 antibody (Qiagen) and with a 1:5000 dilution of a peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Dianova). Peroxidase detection was carried out with the ECL-Plus kit (Amersham-Pharmacia). An affinity-purified, highly specific antibody against mycoAC204–443 raised in rabbits was employed to detect AC expression in homogenates from E.coli and HEK293 cells.

Cross-linking with glutaraldehyde

The cross-linking of purified mycoAC204–443 was carried out in 30 µl at 22°C in 50 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, ± 850 µM ATP, 20 mM glutaraldehyde and 20% glycerol pH 7.4. After 60 min, the reaction was quenched with 1 µl of 1 M Tris–HCl pH 7.5. After addition of 5 µl of sample buffer, proteins were resolved by 15% SDS–PAGE and detected in a western blot using the anti-RGS-His4 antibody.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Jost Weber and Christian Beyer for help. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

References

- Baltimore D. (2001) Our genome unveiled. Nature, 409, 814–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar N.B., Bhatnagar,R. and Venkitasubramanian,T.A. (1984) Characterization and metabolism of cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 121, 634–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang G., Spencer,R.H., Lee,A.T., Barclay,M.T. and Rees,D.C. (1998) Structure of the MscL homolog from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a gated mechanosensitive ion channel. Science, 282, 2220–2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G.Q., Cui,C., Mayer,M.L. and Gouaux,E. (1999) Functional characterization of a potassium-selective prokaryotic glutamate receptor. Nature, 402, 817–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. et al. (1995) A region of adenylyl cyclase 2 critical for regulation by G protein βγ subunits. Science, 268, 1166–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole S.T. et al. (1998) Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature, 393, 537–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisenhofer J., Epp,O., Miki,K., Huber,R. and Michel,H. (1985) Structure of the protein subunits in the photosynthetic reaction centre of Rhodopseudomonas viridis at 3 Å resolution. Nature, 318, 618–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haga T., Haga,K. and Gilman,A.G. (1977) Hydrodynamic properties of the β-adrenergic receptor and adenylate cyclase from wild type and variant S49 lymphoma cells. J. Biol. Chem., 252, 5776–5782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara M., Unno,T., Yashiro,K. and Ohmori,M. (2001) CyaG, a novel cyanobacterial adenylyl cyclase and a possible ancestor of mammalian guanylyl cyclases. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 10564–10569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston R.E., Chen,C.A. and Okayama,H. (1992) Calcium phosphate transfection. In Ausubel,F.M., Brant,A., Kingston,R.E., Moore,P., Sudman,J.G., Smith,J.A. and Struhl,K. (eds), Short Protocols in Molecular Biology. John Wiley and Sons, New York, pp. 9.7–9.9.

- Krupinski J., Coussen,F., Bakalyar,H.A., Tang,W.J., Feinstein,P.G., Orth,K., Slaughter,C., Reed,R.R. and Gilman,A.G. (1989) Adenylyl cyclase amino acid sequence: possible channel- or transporter-like structure. Science, 244, 1558–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder J.U., Engel,P., Reimer,A., Krüger,T., Plattner,H., Schultz,A. and Schultz,J.E. (1999) Guanylyl cyclases with the topology of mammalian adenylyl cyclases and an N-terminal P-type ATPase-like domain in Paramecium, Tetrahymena and Plasmodium. EMBO J., 18, 4222–4232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Ruoho,A.E., Rao,V.D. and Hurley,J.H. (1997) Catalytic mechanism of the adenylyl and guanylyl cyclases: modeling and mutational analysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 13414–13419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowrie D.B. (1978) Tubercle bacilli in infected macrophages may inhibit phagosome–lysosome fusion by causing increased cAMP concentrations. In Folco,G. and Paoletti,R. (eds), Molecular Biology and Pharmacology of Cyclic Nucleotides. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 311–314.

- McCue L.A., McDonough,K.A. and Lawrence,C.E. (2000) Functional classification of cNMP-binding proteins and nucleotide cyclases with implications for novel regulatory pathways in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Genome Res., 10, 204–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C.J. and Salomon,J.A. (1998) Modeling the impact of global tuberculosis control strategies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 13881–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padh H. and Venkitasubramanian,T.A. (1980) Lack of adenosine-3′,5′-monophosphate receptor protein and apparent lack of expression of adenosine-3′,5′-monophosphate functions in Mycobacterium smegmatis CDC 46. Microbios., 27, 69–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodbell M., Lad,P.M., Nielsen,T.B., Cooper,D.M., Schlegel,W., Preston,M.S., Londos,C. and Kempner,E.S. (1981) The structure of adenylate cyclase systems. Adv. Cyclic Nucleotide Res., 14, 3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon Y., Londos,C. and Rodbell,M. (1974) A highly sensitive adenylate cyclase assay. Anal. Biochem., 58, 541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar S., Kapatral,V. and Chakrabarty,A.M. (1997) Mammalian heterotrimeric G-protein-like proteins in mycobacteria: implications for cell signalling and survival in eukaryotic host cells. Mol. Microbiol., 26, 607–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider D.E.J., Raviglioni,M. and Kochi,A. (1994) Tuberculosis: Pathogenesis, Protection and Control. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- Sunahara R.K., Dessauer,C.W. and Gilman,A.G. (1996) Complexity and diversity of mammalian adenylyl cyclases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol., 36, 461–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunahara R.K., Beuve,A., Tesmer,J.J., Sprang,S.R., Garbers,D.L. and Gilman,A.G. (1998) Exchange of substrate and inhibitor specificities between adenylyl and guanylyl cyclases. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 16332–16338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W.J. and Gilman,A.G. (1995) Construction of a soluble adenylyl cyclase activated by Gsα and forskolin. Science, 268, 1769–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W.J. and Hurley,J.H. (1998) Catalytic mechanism and regulation of mammalian adenylyl cyclases. Mol. Pharmacol., 54, 231–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W.J., Stanzel,M. and Gilman,A.G. (1995) Truncation and alanine-scanning mutants of type I adenylyl cyclase. Biochemistry, 34, 14563–14572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesmer J.J., Sunahara,R.K., Gilman,A.G. and Sprang,S.R. (1997) Crystal structure of the catalytic domains of adenylyl cyclase in a complex with Gsα-GTPγS. Science, 278, 1907–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesmer J.J., Sunahara,R.K., Johnson,R.A., Gosselin,G., Gilman,A.G. and Sprang,S.R. (1999) Two-metal-ion catalysis in adenylyl cyclase. Science, 285, 756–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisnant R.E., Gilman,A.G. and Dessauer,C.W. (1996) Interaction of the two cytosolic domains of mammalian adenylyl cyclase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 6621–6625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S.Z., Hahn,D., Huang,Z.H. and Tang,W.J. (1996) Two cytoplasmic domains of mammalian adenylyl cyclase form a Gsα- and forskolin-activated enzyme in vitro. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 10941–10945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S.Z., Huang,Z.H., Shaw,R.S. and Tang,W.J. (1997) The conserved asparagine and arginine are essential for catalysis of mammalian adenylyl cyclase. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 12342–12349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager R.E., Heideman,W., Rosenberg,G.B. and Storm,D.R. (1985) Purification of the calmodulin-sensitive adenylate cyclase from bovine cerebral cortex. Biochemistry, 24, 3776–3783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G., Liu,Y., Ruoho,A.E. and Hurley,J.H. (1997) Structure of the adenylyl cyclase catalytic core. Nature, 386, 247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]