Abstract

To visualize the formation of disulfide bonds in living cells, a pair of redox-active cysteines was introduced into the yellow fluorescent variant of green fluorescent protein. Formation of a disulfide bond between the two cysteines was fully reversible and resulted in a >2-fold decrease in the intrinsic fluorescence. Inter conversion between the two redox states could thus be followed in vitro as well as in vivo by non-invasive fluorimetric measurements. The 1.5 Å crystal structure of the oxidized protein revealed a disulfide bond-induced distortion of the β-barrel, as well as a structural reorganization of residues in the immediate chromophore environment. By combining this information with spectroscopic data, we propose a detailed mechanism accounting for the observed redox state-dependent fluorescence. The redox potential of the cysteine couple was found to be within the physiological range for redox-active cysteines. In the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli, the protein was a sensitive probe for the redox changes that occur upon disruption of the thioredoxin reductive pathway.

Keywords: fluorescence indicator/oxidoreductase/redox potential/thioredoxin reductase/YFP

Introduction

While disulfide bonds serve as important structural components of many of the proteins exported from the cell, they are almost completely absent from their cytosolic counterparts (Gilbert, 1990). In the periplasm of Escherichia coli, disulfide bonds are introduced into nascent proteins through the action of the DsbA and DsbC pathways (reviewed by Rietsch and Beckwith, 1998; Debarbieux and Beckwith, 1999). In the cytosol, protein disulfide bonds are also found; however, here they are only formed transiently. Thus, disulfides are found as part of the catalytic cycle of enzymes such as ribonucleotide reductase or in redox-regulated proteins such as the chaperone Hsp33 and the transcription factor OxyR (Aberg et al., 1989; Zheng et al., 1998; Jakob et al., 1999). Maintenance of protein sulfhydryls in general as well as recycling of these proteins to the reduced state relies on two partially redundant pathways, one involving thioredoxins (encoded by trxA and trxC) and the other glutaredoxins (encoded by grxA, B and C) (Prinz et al., 1997; Aslund and Beckwith, 1999). These thiol–disulfide oxidoreductases belong to a family of enzymes having in common a pair of redox-active cysteines in a Cys-Xaa-Xaa-Cys motif (Martin, 1995). Cycling of the active site cysteines between the reduced and oxidized state allows them to undergo disulfide exchange reactions with protein substrates or small thiol compounds such as glutathione. Both pathways rely on NADPH as the source of reducing equivalents. In the thioredoxin pathway, they are delivered to thioredoxin by the flavoenzyme thioredoxin reductase (encoded by trxB), while electrons are transferred via glutathione reductase and glutathione to the glutaredoxins (Holmgren, 1989).

Characterization of the pathways leading to the formation or reduction of disulfide bonds has relied extensively on the use of naturally occurring proteins as endogenous probes of the cellular thiol–disulfide redox state. These have been selected based on discernible characteristics of their oxidized and reduced state such as enzymatic activity [e.g. alkaline phosphatase (Derman et al., 1993) and β-galactosidase (Bardwell et al., 1991; Jonda et al., 1999)] and electrophoretic mobility (e.g. OmpA and β-lactamase; Bardwell et al., 1991). However, although a variety of such reporters are available in E.coli, only few exist in yeast and mammalian cells and none support non-invasive redox monitoring at the single-cell level. To overcome these limitations, we have engineered a new type of redox reporter based on the fluorescent properties of green fluorescent protein (GFP). Besides its bright and visible fluorescence, GFP exhibits a number of attractive features for in vivo reporter applications. It is chemically inert and does not interfere with cellular processes; contains no disulfide bonds, and can be targeted specifically to subcellular compartments such as the endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria and the periplasmic space in bacteria (De Giorgi et al., 1999; Casey et al., 2000).

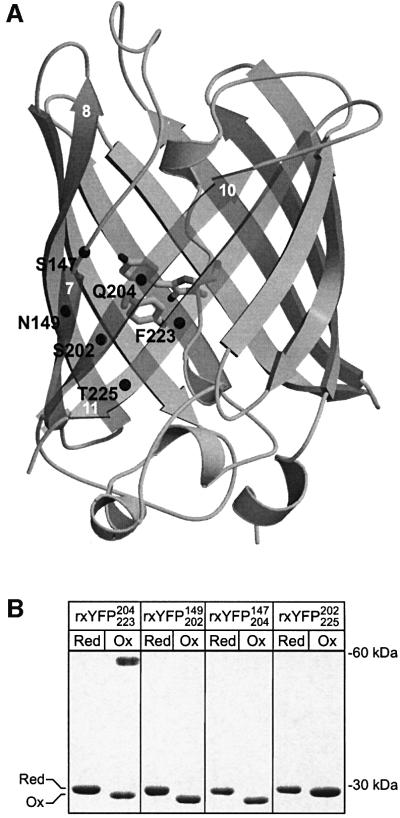

GFP consists of 238 amino acids folded into an 11-stranded β-barrel wrapped around a central irregular α-helix (see Figure 1A) (Ormo et al., 1996; Yang et al., 1996). The chromophore is situated in the middle of the α-helix and is generated by an autocatalytic cyclization of the tripeptide segment -Ser65-Tyr66-Gly67- (Cody et al., 1993; Heim et al., 1994; Reid and Flynn, 1997). Mutagenesis of the chromophore sequence and the surrounding barrel structure has resulted in variants with significantly altered absorption and emission spectra (reviewed by Tsien, 1998; Palm and Wlodawer, 1999; Remington, 2000). One example is the yellow fluorescent variant of GFP (YFP) with a Thr→Tyr mutation at position 203. In the crystal structure of YFP (termed wtYFP in the following), the highly polarizable tyrosine side chain stacks with the phenolic moiety of chromophore, leading to a red shift of the fluorescence spectrum (Wachter et al., 1998).

Fig. 1. Cysteine mutants of the yellow fluorescent protein. (A) The six positions at which cysteines residues were introduced are marked with black spheres in the crystal structure of wtYFP (Wachter et al., 1998). The chromophore and the side chain of Tyr203 are shown as stick representations. Relevant β-strands are numbered in white according to Yang et al. (1996). (B) Spontaneous oxidation of the cysteine mutants as monitored by non-reducing SDS–PAGE. Reduction of the four mutant proteins was performed by overnight incubation with 20 mM DTT. Subsequently they were dialysed against 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0 for 17 h at room temperature to promote oxidation. Trichloroacetic acid (10% v/v) was added to aliquots of the samples taken before (marked Red) and after (marked Ox) dialysis. The protein precipitate was washed twice with acetone and then alkylated with 50 mM N-ethylmaleimide before analysis by non-reducing SDS–PAGE on a 16% gel.

Using YFP as a template, we present here the design and the biochemical and structural characterization of a novel fluorescent disulfide bond reporter and show that it is a sensitive probe of the redox state in the cytoplasm of E.coli.

Results

Engineering disulfide bonds in YFP

The spectral properties of GFPs are determined in part by a number of non-covalent interactions between the chromophore and residues in the surrounding barrel structure. The majority of these residues are situated on the inner side of three consecutive β-strands 7, 10 and 11, shielding the chromophore from the bulk solvent (Figure 1A). In wtYFP, these residues constitute His148, Tyr203, Glu222, Asn146 and Ser205 (Wachter et al., 1998). Previous studies have identified this region of the β-barrel as being structurally flexible, tolerating the introduction of new N- and C-termini by circular permutation and even insertion of entire protein domains (Baird et al., 1999; Topell et al., 1999). This led us to speculate that reversible formation of a strained disulfide in this part of the protein might perturb the surrounding structure sufficiently to bring about a measurable change in the fluorescent properties of the protein. By visual inspection of the crystal structure of wtYFP, four pairs of residues 147–204, 149–202, 202–225 and 204–223, were found suitable for disulfide engineering. As shown in Figure 1A, each pair bridges two of the three β-strands interacting with the chromophore and are, furthermore, solvent exposed to enable free access of the surrounding redox buffer.

GFP contains two native cysteines, Cys48 and Cys70. Previous work by Inouye and Tsuji (1994) indicated that Cys48, being partially solvent exposed, might be susceptible to modification by thiol-specific reagents. To avoid interfering side reactions, it was substituted for a valine (see Materials and methods for details). The four proteins were produced in high yield in E.coli, indicating that the mutations did not significantly impair protein folding or autocatalytic formation of the chromophore. In the following, they will be referred to as rxYFPXaa1Xaa2, where Xaa1 and Xaa2 designate the two positions at which cysteines were introduced.

To investigate whether the four cysteine variants were able to form disulfide bonds under oxidizing conditions, the purified proteins were dialysed against air-saturated buffer at pH 8.0. Pre-treatment with dithiothreitol (DTT) was performed to reduce any disulfide bonds present in the starting material. For each of the proteins, complete oxidation was found to occur within hours, observed by non-reducing SDS–PAGE as a slight increase in electrophoretic mobility (Figure 1B). One of the mutant forms, rxYFP204223, in addition to forming oxidized monomers, also associated into disulfide-bonded dimers (apparent as a band at ∼60 kDa). These were highly stable and required prolonged incubation with high concentrations of DTT to dissociate (data not shown). Consequently, rxYFP204223 was not investigated further.

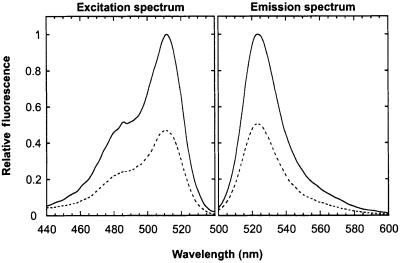

The most pronounced difference in the fluorescent properties of the reduced and oxidized state was observed for rxYFP149202, where formation of the disulfide resulted in a 2.2-fold reduction of the emission peak at pH 7.0 (Figure 2). In comparison, rxYFP147204 and rxYFP202225 only displayed an ∼1.2-fold change. Apart from the change in amplitude, the spectra of the two redox states were essentially identical and similar to those of wtYFP, with excitation and emission peaks at 512 and 523 nm, respectively, and a minor shoulder around 488 nm. The substantial spectral response of rxYFP149202 to changes in its redox state prompted us to characterize this variant in further detail.

Fig. 2. Fluorescence excitation and emission spectra of oxidized (dashed line) and reduced (solid line) rxYFP149202 in 100 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.0, 1 mM EDTA at 30°C. The two spectra were recorded at emission and excitation wavelengths of 540 and 490 nm, respectively. The fluorescent properties of reduced rxYFP149202 are identical to those of the template YFP used (see Materials and methods).

Stability and reactivity of the C149–C202 disulfide bond

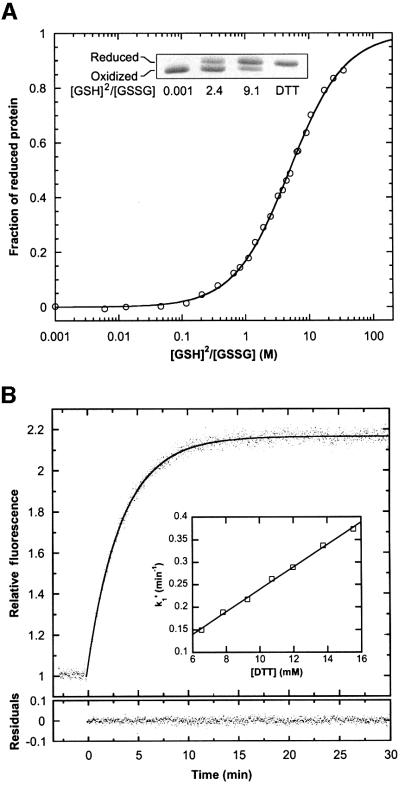

The redox potential of the cysteine couple in rxYFP149202 was determined from the equilibrium constant of the reaction with glutathione at pH 7.0 and 30°C. By measuring the intrinsic fluorescence of rxYFP149202 equilibrated in buffers with various ratios of reduced and oxidized glutathione (abbreviated GSH and GSSG, respectively), Kox was determined to 5.0 ± 0.15 M (Figure 3A). Analysis of the equilibrium mixtures by non-reducing SDS–PAGE (Figure 3A, inset) yielded the same value of Kox and thereby reconfirmed the tight correlation between the intrinsic fluorescence of the protein and its redox state. For the calculation of Kox, it was assumed that the concentration of protein–glutathione mixed disulfide at equilibrium was insignificant, an assumption that was justified by the close fit of the model to the experimental data as well as the high effective molarity of the cysteine residues relative to the concentrations of glutathione used (the equilibrium constant for protein–glutathione mixed disulfides are generally <1) (Gilbert, 1990, 1995). A standard redox potential (Eo′) of –261 mV was calculated from the Nernst equation using an Eo′ value of –240 mV for the GSH/GSSG redox couple (Rost and Rapoport, 1964). In comparison, disulfide redox potentials encountered in proteins vary from –122 mV (DsbA; Wunderlich and Glockshuber, 1993; Huber-Wunderlich and Glockshuber, 1998) to –270 mV (thioredoxin; Lin and Kim, 1989; Krause et al., 1991) for the family of thiol–disulfide oxidoreductases. For disulfide bonds serving structural purposes, it can be as low as –470 mV (Gilbert, 1990).

Fig. 3. Stability and reactivity of the disulfide bond in rxYFP149202 at pH 7.0 and 30°C. (A) Redox titration of rxYFP149202 with reduced and oxidized glutathione. After equilibration in buffers with varying [GSH]2/[GSSG] ratios, the fraction of protein in the reduced state was measured by the intrinsic fluorescence at 523 nm, as described in Materials and methods. Due to trace impurities of GSSG in the commercially available GSH, the last part of the titration curve could not be obtained. However, addition of DTT to a subset of the samples yielded, within experimental error, the same specific fluorescence of the reduced form as was estimated by curve fitting. Inset: the distribution of rxYFP149202 between the two redox states as monitored by non-reducing SDS–PAGE. Samples were prepared as described in Figure 1B. (B) Reduction of the protein (∼0.3 µM) was performed under pseudo first-order conditions with 12 mM DTT in 100 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.0 and 1 mM EDTA. The reaction was followed by the change in fluorescence at 523 nm. A pseudo first-order rate constant (k1′) was obtained by fitting the progress curve to a single exponential function (residuals are shown below the curve). Inset: a plot of k1′ versus [DTT], obtained from a series of similar experiments, yielded a value of 24.8 ± 0.6 M/min for the apparent second-order rate constant.

The reactivity of the disulfide bond was determined from the kinetics of its reaction with DTT at pH 7.0 and 30°C. The time course of the reaction was followed by the increase in fluorescence at 523 nm. Initial experiments made it clear that high concentrations of DTT were required to achieve a reasonable rate of reduction. Therefore, reactions were performed under pseudo first-order conditions with a >104 molar excess of DTT (Figure 3B). From a fit of the progress curves to a single exponential function, the apparent second-order rate constant (k2) was estimated to 24.8 ± 0.6 M/min, which is close to the value of 14.1 M/min reported for reduction of oxidized glutathione by DTT (Szajewski and Whitesides, 1980).

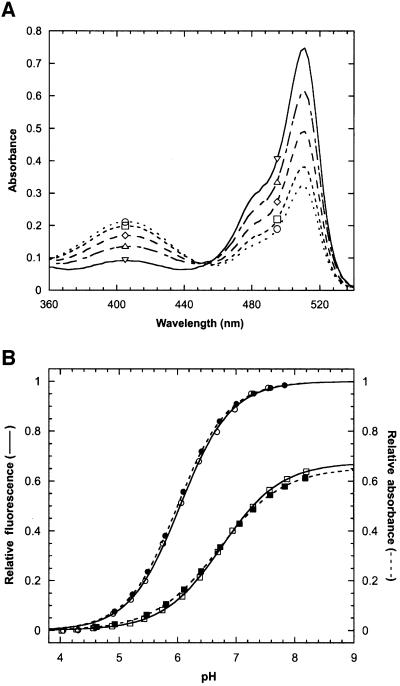

Spectral properties of rxYFP149202

Next, we investigated the mechanism underlying the redox state-dependent shift in fluorescence emission. Figure 4A shows the absorption spectra of the protein at five different points on the redox titration curve given in Figure 3A. Peaks are observed at 404 and 512 nm. Previous studies have shown the two absorption bands to arise from a protonated and deprotonated state of the chromophore, respectively (Chattoraj et al., 1996; Niwa et al., 1996; Brejc et al., 1997; Elsliger et al., 1999). The phenolic moiety of Tyr66 is responsible for this behaviour (Elsliger et al., 1999); it is a weak monoprotic acid and, despite its location in the interior of the β-barrel, it responds rapidly to changes in the external pH. In YFP, the protonated chromophore is non-fluorescent. The increase in the 404/512 nm peak ratio upon oxidation suggests that bridging of the two cysteines shifts the equilibrium between the two chromophore protonation states towards the non-fluorescent, protonated form. This was confirmed by fluorescence pH titrations of the free and disulfide-bonded protein yielding apparent chromophore pKa values of 6.05 ± 0.01 [Hill coefficient (n) = 1.00] and 6.76 ± 0.01 (n = 0.86), respectively (Figure 4B). Similar values, 6.00 ± 0.01 (n = 0.98) and 6.70 ± 0.03 (n = 0.79), were obtained by absorbance measurements. A shift in the chromophore ionization constant of 0.7 units alone, however, is not sufficient to account for the observed change in the intrinsic fluorescence. Disulfide bond formation also leads to an ∼1.5-fold reduction in the molar extinction coefficient of the deprotonated chromophore, which is evident from the lack of convergence of the two absorption pH titration curves at high pH, where the chromophore is predominantly negatively charged (see Figure 4B).

Fig. 4. Redox state-dependent spectral properties of rxYFP149202 at 30°C. (A) Absorption spectra were recorded after equilibration of the protein in redox buffers with [GSH]2/[GSSG] ratios of 0.004 M (open circles), 0.55 M (open squares), 2.17 M (open diamonds) and 8.13 M (open triangles) (see Figure 3A). Reduced protein (open inverted triangles) was obtained by incubation with 10 mM DTT for 2 h. (B) The relative fluorescence (open symbols) and relative absorbance (closed symbols) of reduced (circles) and oxidized (squares) rxYFP149202 as a function of pH. Data were fitted as described in Materials and methods. The estimated values of the chromophore pKa and the Hill coefficient (n) are given in the text.

Crystallographic analysis of oxidized rxYFP149202

To define the structural basis of the redox state-dependent fluorescence, the crystal structure of oxidized rxYFP149202 was determined. The protein was crystallized at pH 8.0 to ensure a homogenous population of deprotonated chromophores. Using wtYFP as a search model, the structure was solved by molecular replacement. The final resolution was 1.5 Å, with R-factors of 18.3 and (Rfree) 21.2%, respectively (data collection and refinement statistics are given in Table I).

Table I. Data collection and refinement statistics.

| Data collection | Refinement | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.0362 | Rconv (%) | 18.3 |

| X-ray source | 711 Lund | Rfree (%) | 21.2 |

| Resolution (Å) | Resolution (Å) | 78.09–1.50 | |

| overall | 78.09–1.50 | No. of reflections | |

| outer shell | 1.55–1.50 | Working set | 109 885 |

| No. of reflections | Test set | 5546 | |

| overall | 750 960 | No. of atoms | |

| unique | 116 321 | Protein | 5627 |

| Mosaicity | 0.25 | Solvent | 840 |

| Rsym (%) | B-factor, protein atoms (Å2) | 16.8 | |

| overall | 3.3 | B-factor, solvent atoms (Å2) | 31.1 |

| outer shell | 43.9 | R.m.s.d. bond distance (Å) | 0.011 |

| I/σI | R.m.s.d. bond angle (°) | 1.8 | |

| overall | 18.3 | Ramachandran plot, residues in | |

| outer shell | 2.0 | Most favourable regions (%) | 90.8 |

| Completeness (%) | Additional allowed regions (%) | 9.0 | |

| overall | 89.1 | Disallowed regions (%) | 0.0 |

| outer shell | 72.9 | Estimated coordinate error from sigmea (Å) | 0.16 |

| C–V estimated coordinate error from sigmea (Å) | 0.16 |

Overall, the crystal structure of rxYFP149202 resembles that of wtYFP, with a root mean square deviation of 0.5 Å for the α carbons (Figure 5A). As shown in Figure 5B, significant 2Fo – Fc electron density is visible between β-strands 7 (residues 147–153) and 10 (residues 199–208) corresponding to the disulfide bridge, which is completely exposed on the surface of the protein. The cysteine side chain adopts a right-handed staple conformation, which is identical to that of naturally occurring disulfides spanning adjacent antiparallel β-strands (Harrison and Sternberg, 1996). Due to the geometrical requirements of the disulfide, the distance separating the two Cα atoms is reduced by 0.8 Å relative to wtYFP, resulting in a local constriction of the two β-strands at the site of the disulfide bridge (Figure 5C). This is brought about mainly by a movement of Cys149 towards β-strand 10. Movement of Asn164, Phe165 and Lys166 (part of β-strand 8) in the opposite direction leads to an unzipping of the β-sheet between strands 7 and 8 and the concomitant loss of three main chain hydrogen bonds (one of them mediated by a water molecule; marked with dashed lines in Figure 5C). On the molecular surface, the strand separation is evident as a narrow, water-filled groove running along the β-strands. However, direct solvent access to the chromophore, which is located immediately behind the strands, is prevented due to steric blocking by the side chain of His148 (see below).

Fig. 5. Crystal structure of oxidized rxYFP149202. (A) Superposition of oxidized rxYFP149202 (throughout the figure in blue) and wtYFP (throughout in yellow; Wachter et al., 1998) (r.m.s. deviation is 0.5 Å for equivalent Cα atoms). The chromophore, Cys149 and Cys202 are shown as ball-and-stick representations with the disulfide bond coloured green. (B) The 2Fo – Fc electron density map of the C149–C202 disulfide bridge (contoured at 1σ in blue and at 8σ in green). Superimposed is the final model of the disulfide bridge, which adopts the right-handed staple conformation. (C) Overlay of the backbone trace of wtYFP and oxidized rxYFP149202. Also shown are the disulfide bond (in green), the side chain of His148 and the chromophore (Cro66). The dashed lines indicate those hydrogen bonds that are present in wtYFP but absent in the rxYFP149202 structure. (D) Position of Tyr203 and His148 relative to the chromophore. The superimposed chromophore structures of rxYFP149202 and wtYFP are shown in grey. Dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds to the δ1 and ε2 nitrogens of His148.

In wtYFP, the imidazole of His148 is wedged between strands 7 and 8 (Wachter et al., 1998). It receives a hydrogen bond from the backbone of Arg168 and serves as an obligate hydrogen bond donor, via Nδ1, to the phenolate oxygen of Tyr66 (Figures 5C and 6D). Site-directed mutagenesis of His148 has shown this interaction to be highly important in stabilizing the negatively charged deprotonated state of the chromophore (Elsliger et al., 1999). Substitution by glycine or glutamine residues, which do not hydrogen-bind to the chromophore, lowers the equilibrium constant for ionization by more than one order of magnitude (Wachter et al., 1998, 2000). In oxidized rxYFP149202, a major repositioning of His148 has taken place. Relative to wtYFP, it has moved away from the plane of the β-sheet by 1.4 Å and the imidazole side chain has rotated 108° around the χ1 bond (Figure 5D). It is now in a position where it can interact with the chromophore phenolic oxygen through the Nε2 atom. As the hydrogen bond partner to the Nδ1 atom is a solvent molecule (located in the groove between the β-strands 7 and 8), Nε2 can serve as both a donor and an acceptor of the hydrogen bond depending on the protonation state of Tyr66. The loss of directionality of the hydrogen bond is most likely to be the major cause of the observed increase in the chromophore pKa.

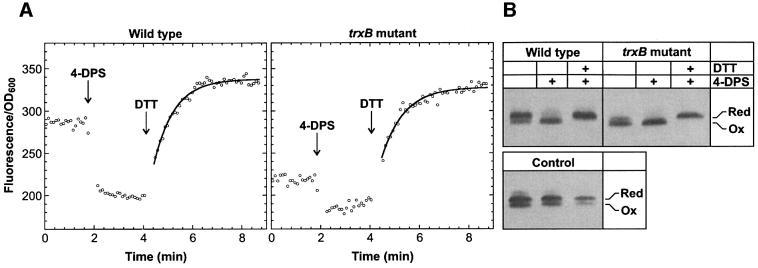

Fig. 6. Redox state of rxYFP149202 expressed in wild-type E.coli and a trxB mutant at 30°C. (A) Fluorescence was monitored continuously at 523 nm in a standard fluorimeter (see Materials and methods). From the initial fluorescence and the fluorescence after sequential addition of 50 µl of 3.6 mM 4-DPS and 50 µl of 1 M DTT to 900 µl of the cultures, the proportion of oxidized reporter in the two strains was calculated to 53% (wild type) and 86% (trxB), respectively. (B) Western blot detection of rxYFP149202 in the cultures before (lane 1) and after treatment with 4-DPS and DTT (lanes 2 and 3, respectively). In the lanes marked ‘Control’ were loaded equal amounts of reduced and oxidized rxYFP149202 at increasing dilution to show that the anti-GFP antibodies used bind with lower affinity to the oxidized reporter. Quantitative densitometric analysis of the bands corresponding to the untreated cultures, taking into account the weaker binding of the antibodies to the oxidized protein, indicated 50% oxidized reporter in the wild type and 83% in the trxB mutant.

In the interior of the protein, the chromophore has moved 0.7 Å away from the gap in the β-sheet and now occupies a position similar to that of wild-type GFP and S65T GFP (Ormo et al., 1996; Yang et al., 1996). The side chain of Tyr203 has rotated 30° around the χ1 bond in the same direction. Compared with the off-centred parallel displaced arrangement of the Tyr203 side chain and the chromophore phenol in wtYFP, the two aromatic rings are positioned at skewed angles in rxYFP149202 (Figure 5D). It presently is not clear to what extent this misalignment or other small-scale movements of side chains in the immediate chromophore environment contribute to the observed drop in the molar extinction coefficient upon oxidation.

Redox monitoring in the cytoplasm

To demonstrate the functionality of rxYFP149202 in vivo, it was expressed in the cytoplasm of wild-type E.coli and an isogenic strain disrupted in the trxB gene encoding thioredoxin reductase. Deficiency of trxB leads to the accumulation of thioredoxin in the oxidized state, which promotes the incorporation of disulfide bonds into nascent cytoplasmic proteins (Derman et al., 1993; Stewart et al., 1998).

Fluorescence measurements were carried out in a standard fluorimeter after expression of the reporter from the lac promoter in exponentially growing cells for >10 generations. As expected, fluorescence intensity per OD600 was found to be highest for the wild type, indicating increased levels of oxidized rxYFP149202 in the trxB mutant (Figure 6A). Due to the dependency of fluorescence intensity on the protein concentration, calibration was required to determine the exact ratio between oxidized and reduced reporter. This was carried out by measuring the fluorescence after sequential addition of oxidant (Fox) and reductant (Fred) directly to the culture in the cuvette. After addition of the membrane-permeable thiol-oxidant 4,4′-dithiodipyridine (4-DPS; Grassetti and Murray, 1967) and DTT, the fraction of oxidized reporter in the wild type and the trxB mutant was found to be 53 ± 3 and 86 ± 3%, respectively. Similar distributions were obtained by western blotting (Figure 6B). Oxidation of rxYFP149202 also occurred after addition of the widely used thiol-oxidant diamide although with a rate constant more than two orders of magnitude lower than that of oxidation by 4-DPS.

Based on the measured values of Fred/Fox and the correlation between fluorescence and pH given in Figure 4B, the pH in the cytoplasmic compartment of the two strains could be estimated to 7.4 ± 0.1. This corresponds well with the value of 7.5 determined by 31P NMR in aerobically respiring E.coli cells grown at neutral pH (Slonczewski et al., 1981). While oxidation of the reporter by 4-DPS was too fast (within the mixing time in the cuvette) to allow for a kinetic characterization of the reaction, reduction by DTT occurred over minutes. The progress curve conformed to pseudo first-order kinetics from which apparent second-order rate constants of 30 ± 1 M/min (wild type) and 28 ± 1 M/min (trxB mutant) could be extracted. The elevated pH of the cytosol most probably accounts for the slightly higher values of k2 as compared with those determined in vitro (see Figure 3B).

Discussion

Functional and structural properties of rxYFP149202

In an effort to visualize the formation of disulfide bonds in living cells, redox-active cysteines were introduced into YFP. Of the four double-cysteine mutants constructed, only rxYFP149202 exhibited a change in the intrinsic fluorescence sufficient to enable in vivo redox monitoring. The >2-fold change observed at neutral pH is comparable in magnitude with the dynamic range of other YFP-based reporters (Miyawaki et al., 1997; Jayaraman et al., 2000). However, due to differential pH sensitivities of the reduced and oxidized state, the dynamic range was found to vary substantially according to the pH. Thus, at pH 6.5, corresponding to the pH in the cytoplasm of yeast (Calahorra et al., 1998), the relative difference between the two redox states was 2.9 as compared with a factor of only 1.75 at pH 7.5 (the cytoplasm of E.coli).

Spectroscopic studies showed the oxidation-induced reduction of the intrinsic fluorescence to be caused by the combined effects of (i) a shift in the equilibrium between the two chromophore protonation states towards the non-fluorescent, protonated state and (ii) a lower molar extinction coefficient of the fluorescent, deprotonated chromophore. Quantum yield therefore appears to be unaffected by disulfide bond formation, implying that the disulfide bond itself does not quench the chromophore fluorescence. The crystal structure of oxidized rxYFP149202 rather points to a role for the disulfide bond as a source of strain, which through a distortion of the β-barrel perturbs the local environment of the chromophore. The importance of the exact position of the disulfide bond in bringing about this change is illustrated by the other two double-cysteine mutants, where fluorescence changes of only ∼1.2-fold were observed, although the disulfide bond in these cases is <8 Å away from the 149–202 site. The location of the cysteine pair also had a dramatic effect on the redox potential. While the disulfide bond between Cys147 and Cys204 (Kox = 2.4 M; data not shown) was almost as stable as that between Cys149 and Cys202, moving it to the 202–225 site resulted in a >104-fold decrease in the equilibrium constant (Kox) with glutathione (data not shown). One of the major factors contributing to this large difference in stability is probably the lack of backbone hydrogen bonds between the cysteines in rxYFP149202 and rxYFP147204, which allows the two residues to approach each other relatively unhindered upon oxidation (in the right-handed staple conformation, the Cα interatomic distance is ∼3.9 Å as compared with the normal distances of ∼4.5 and ∼5.5 Å between adjacent antiparallel β-strands; Wouters and Curmi, 1995). In rxYFP202225, on the other hand, two main chain hydrogen bonds have to be broken or at least distorted for the disulfide to adopt the right geometry. This is an energetically costly process, decreasing the stability of the disulfide. The unfavourable situation of having a disulfide bond bridging two backbone hydrogen-bonded cysteines is emphasized by the fact that disulfides spanning adjacent antiparallel β-strands in natural proteins occur exclusively at the so-called wide-pair hydrogen bonding positions (Harrison and Sternberg, 1996).

In vivo redox monitoring

In a screen for mutants that would allow a signal-sequenceless version of alkaline phosphatase to fold into its active, disulfide-bonded conformation, Derman et al. (1993) identified thioredoxin reductase (trxB) as being a key determinant of the cytoplasmic thiol–disulfide redox status. Using rxYFP149202 as an indicator of the cytoplasmic redox state, we reached the same result. Upon disruption of the trxB gene, the fraction of disulfide-bonded reporter increased by >30%, corresponding to a shift in the redox potential from –259 mV to –237 mV (calculated from the actual distribution of the reporter between the two redox states assuming a pH of 7.0). Interestingly, half of the reporter was already oxidized in the wild type. Only in very few cases have stable disulfide bonds been observed in cytosolic proteins (Nilsson et al., 1991; Locker and Griffiths, 1999). Based on the following observations, we believe the cytosolic pool of oxidized glutathione to be the primary oxidant of the reporter: (i) reduced thioredoxin (trxA) does not react with oxidized rxYFP149202 in vitro (data not shown); (ii) the cytoplasmic GSH/GSSG redox potential, roughly estimated to be within –220 to –245 mV [using GSH/GSSG ratios of 1:50–1:200 (Hwang et al., 1992; Tuggle and Fuchs, 1985) and a concentration of GSH of 3.6–6.6 mM (Kosower and Kosower, 1978)], is close to that determined using rxYFP149202, as would be expected if the two redox pairs were in equilibrium. It is presently not known whether increased amounts of oxidized glutathione are responsible for the higher proportion of oxidized rxYFP149202 in the trxB mutant or whether disulfide bond formation during folding catalysed by oxidized thioredoxin also plays a role. In vitro refolding of acid-denatured rxYFP149202 shows that the oxidized state folds as efficiently as the reduced state (data not shown).

Seen in a broader perspective, the above findings raise the question as to why cytoplasmic proteins are devoid of disulfide bonds. Clearly, sufficient oxidation potential is present for them to form. Moreover, disulfide bonds serving structural purposes are often more stable than that in rxYFP149202, making oxidation an even more favourable reaction (Gilbert, 1990). Part of the reason is probably that disulfide bond formation in the absence of a disulfide catalyst in most cases is too slow to compete with protein folding (Stewart et al., 1998). In rxYFP149202, however, the situation is quite different, as disulfide bond formation is not restricted to the short period of time it takes for the protein to fold but can also take place in the native protein.

In summary, by rational disulfide engineering on the YFP, we have created a non-invasive, redox-sensitive reporter and furthermore demonstrated its functionality in vivo. The ability to functionally express GFP in virtually any organism combined with its targetability to the different subcellular compartments should make it a highly useful redox reporter in a wide range of different applications. It is important to note that its use is not restricted to compartments that are normally reducing; redox monitoring in oxidizing environments such as the periplasm and the endoplasmic reticulum should also be possible.

Materials and methods

Cloning and mutagenesis of YFP

Construction of the four YFP variants shown in Figure 1A was based on a synthetic, E.coli codon-optimized YFP gene present in the pFHC2191 plasmid (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. AF325903). Relative to wild-type GFP, it contains the following mutations: S65A/V68L/S72A/Q80R/M153V/T203Y/D234H. Cysteines were introduced by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis using standard methods. Cys48 was mutated to either alanine, methionine, threonine or valine by PCR using a degenerate oligonucleotide. The C48V mutation gave the brightest colonies at 37°C and was therefore incorporated into the YFP template. For overexpression of protein, the four mutant genes were transferred as NdeI–SpeI fragments to the NdeI–NheI site of the pET24 vector (Novagen) and finally introduced into the BL21(DE3) strain (Novagen).

Expression and purification

Cultures were grown at 37°C in terrific broth with 30 µg/ml kanamycin (Sambrook et al., 1989). At an OD600 of 2.5, the growth temperature was shifted to 22°C and protein expression induced by addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to 0.25 mM. After 17 h of incubation, the cells were harvested, resuspended in 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA (3 ml/g wet pellet), and lysed by three freeze–thaw cycles. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation and subsequently loaded onto a DE52 (Whatman) anion exchange column. The protein was eluted with a linear gradient from 0 to 0.5 M NaCl in lysis buffer. Highly fluorescent fractions were pooled, adjusted to 20% saturation with ammonium sulfate, and applied to a phenyl-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) column. The ammonium sulfate concentration was decreased linearly to 0%, and fluorescent fractions, which eluted at the end of the gradient, were pooled and dialysed overnight against 5 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.0. Finally, the protein was subjected to anion exchange chromatography on a Resource Q column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) equilibrated in 5 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.0. The protein eluted at ∼0.1 M NaCl. Pooled fractions were dialysed against water and stored at –18°C. The protein is estimated to be >95% pure as judged by SDS–PAGE.

Crystallization and data collection

Oxidized rxYFP149202 was concentrated to 24 mg/ml in 10 mM HEPES pH 8.0 using a Centriprep-10 concentrator (Amicon). Crystallization was performed by the hanging drop vapour diffusion method. Equal volumes (2 µl) of protein solution and mother liquor, containing 100 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 100 mM MgCl2 and 14% (w/v) PEG4000 (Merck), were mixed in a single droplet and equilibrated against 1 ml of mother liquor. Rectangular-shaped crystals with approximate dimensions of 0.5 × 0.1 × 0.1 mm3 appeared within 4–5 days at 22°C. Before data collection, the crystals were transferred to mother liquor containing 30% glycerol as cryoprotectant and subsequently flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at beamline 711 at MAX-Lab, Lund University. The data extended to 1.5 Å (Table I). They were integrated and scaled using the HKL software package (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997).

Structure determination

The crystals of oxidized rxYFP149202 contain three molecules per asymmetric unit. Initial phases were determined by molecular replacement (Navaza and Saludjian, 1997) with wtYFP (Wachter et al., 1998) as a search model. The models were refined by slow-cool annealing (Brünger et al., 1998), first applying strict non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) to the molecules and in later stages with no NCS imposed. Individual and restrained B-factors were used in the final cycles of the refinement. The final B-factors of the sulfurs in the disulfide bridge (<BSγ> = 13.1 Å2) resemble the B-factors of its immediate environment. An attempt to refine the occupancy of the sulfur atoms in the disulfide bridge resulted in occupancies of 1.00 ± 0.02, and therefore they were assigned a fixed value of 1.00. The final model consists of three monomers of 230 residues each (residues 2–231), two chloride ions and 840 water molecules. The positional differences between the NCS-related molecules are located primarily in four loops participating in intermolecular interactions. No significant differences are found in the chromophore environment. Refinement statistics are given in Table I. Significant 2Fo – Fc and Fo – Fc electron density is observed in all three molecules close to Cys70. The excess electron density has a centre 1.5 Å from the Sγ position, indicating that the cysteine is in an oxidized state. An oxygen atom at this position is not included in the model, as the exact oxidation state of Cys70 is not known.

Figures were generated using MOLSCRIPT (Kraulis, 1991), Raster3D (Merritt and Bacon, 1997) and Dino (http://www.dino3d.org). The refined coordinates and structure factors of oxidized rxYFP149202 have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, accession code 1h6r.

Protein techniques

Thiol concentrations were determined using Ellman’s reagent (Riddles et al., 1979). GSSG in stock solutions was quantified by absorption at 248 nm (ε = 382 M/cm; Chau and Nelson, 1991). Fluorescence measurements were performed using a Perkin-Elmer Luminescence Spectrometer LS50B with a thermostatted, stirred single-cell holder. Unless stated otherwise, excitation and emission wavelengths were 512 and 523 nm, respectively, at 3 nm slit widths. Absorption spectra were measured using a thermostatted Perkin-Elmer UV/VIS λ16 Spectrometer.

Determination of redox potential

Redox potentials of the YFP variants were determined from their reaction with glutathione essentially as described elsewhere (Loferer et al., 1995). Oxidized protein (∼0.3 µM) was incubated in 100 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.0, 1 mM EDTA (thoroughly purged with argon) containing varying concentrations of oxidized (5–50 µM) and reduced glutathione (250 µM–225 mM). After equilibration of the protein samples under an argon atmosphere for 21 h at 30°C, the redox state of the protein was assessed by spectrofluorimetry. In order to compensate for air oxidation of GSH, an aliquot of the reaction mixture was quenched by addition of formic acid to 10% (v/v) and the equilibrium concentration of GSSG determined by HPLC as described below. The equilibrium constant, Kox, was determined by fitting the data to F = Fox + (Fred – Fox)([GSH]2/[GSSG])/(Kox+[GSH]2/[GSSG]), where Fred and Fox are the fluorescence of the reduced and oxidized protein, respectively.

To determine the concentration of GSSG, 100 µl of the quenched samples were loaded onto a C18 reversed phase column (Vydac 218TP5415). GSSG was eluted with a linear gradient (0–5% in 12 min; 1 ml/min) of acetonitrile in 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid and detected by absorption at 248 nm. The concentration of GSSG was determined by relating the integrated peak area to a GSSG standard curve. Linearity was observed in the range from 2 to 60 nmol.

pH titrations

pH titrations of reduced and oxidized rxYFP149202 were carried out at 30°C in solutions containing 100 mM K2SO4 and 25 mM of one of the following buffers: citrate pH 4.0–5.2, MES pH 5.5–7.0, HEPES pH 7.0–8.0 or Bicine pH 8.2–8.8. Buffers were chosen so that they did not contain any halides or other ions known to quench the YFP fluorescence (Jayaraman et al., 2000). The protein was diluted 50-fold into buffer and, after 5 min of equilibration, fluorescence intensity at 523 nm or absorbance at 512 nm was recorded. The apparent pKa of the chromophore was obtained by fitting the data to S = Smax/[1 + 10n(pKa – pH)], where Smax is the limiting fluorescence/absorbance at high pH and n is the Hill coefficient.

In vivo characterization of rxYFP

The gene encoding rxYFP149202 was excised from the pFHC2191 vector and inserted as an NdeI fragment into the corresponding site of pFHC2102 (F.G.Hansen, unpublished), a pBR322-derived (Bolivar et al., 1977) expression vector carrying the IPTG-inducible lacP(A1/04/03) promotor and the wild-type lacI gene from pBEX5BA (Diederich et al., 1994). The resulting plasmid, pHOJ124, was introduced into the E.coli strain MC1000 [araD139Δ(ara-leu)7697ΔlacX-74 galU galK strA] and HOJ156. The latter was constructed by transducing the trxB::kan mutation present in AD494 (Novagen; Derman et al., 1993) into MC1000 by P1 transduction.

The strains were grown at 30°C in AB minimal medium pH 7.0 (Clark and Maaløe, 1967) supplemented with 1 µg/ml thiamine, 100 µg/ml ampicillin, 0.2% glucose and all the 20 amino acids except cysteine at 50 µg/ml. To ensure identical and reproducible levels of protein expression, log-phase cultures (OD600 <0.5) were maintained for at least 10 generations in the presence of 1 mM IPTG before fluorescence measurements were performed. At an OD600 of 0.4–0.5, 900 µl of the culture were transferred to a pre-warmed cuvette. Fluorescence was monitored continuously at 523 nm, with excitation at 512 nm and slit widths of 4 nm. After a stable baseline was obtained (Finit), 50 µl of 3.6 mM 4-DPS (in water; Aldrich) were added, followed by 50 µl of 1 M DTT (in water; Sigma) to oxidize (Fox) and reduce (Fred), respectively, the protein. The oxidant, 4-DPS, as well as its reaction product 4-thiopyridone absorb well below 400 nm and thus do not interfere with the fluorescence measurements (Grassetti and Murray, 1967). The fraction of oxidized reporter in the untreated culture was calculated from the expression: 1 – (Finit – Fox)/(Fred – Fox).

The redox state of rxYFP149202 was also determined by western blotting. A 1 ml aliquot of culture (before or after treatment with 4-DPS or DTT) was acid quenched by addition of 1/10 volume of 100% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid. After centrifugation, the pellet was washed twice with 0.5 ml of ice-cold acetone and then resuspended in 200 µl of 2% SDS, 100 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 40 mM N-ethylmaleimide (Sigma). Following 1 h of incubation at room temperature, the sample was separated on a 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gel, blotted to a nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond-C extra; Amersham Life Sciences) and probed with rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP antibodies (IgG fraction; Molecular Probes). The primary antibodies were detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated swine anti-rabbit antibodies (DAKO-immunoglobulins A/S) and the enhanced chemiluminescence western blot detection kit (ECL+; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Anette W.Bruun and Søs Koefoed for excellent technical assistance, Morten Kielland-Brandt and Kresten Lindorff-Larsen for critically reading the manuscript, and Per Nørgaard for stimulating discussions. MAX-Lab, beamline 711 and Yngve Cerenius are also gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by a grant from the Carlsberg Foundation to F.G.H. and by the European Community—Access to Research Infrastructure action of the Improving Human Potential Programme.

References

- Aberg A., Hahne,S., Karlsson,M., Larsson,A., Ormo,M., Ahgren,A. and Sjoberg,B.M. (1989) Evidence for two different classes of redox-active cysteines in ribonucleotide reductase of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 12249–12252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslund F. and Beckwith,J. (1999) The thioredoxin superfamily: redundancy, specificity and gray-area genomics. J. Bacteriol., 181, 1375–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird G.S., Zacharias,D.A. and Tsien,R.Y. (1999) Circular permutation and receptor insertion within green fluorescent proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 11241–11246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell J.C., McGovern,K. and Beckwith,J. (1991) Identification of a protein required for disulfide bond formation in vivo. Cell, 67, 581–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolivar F., Rodriguez,R.L., Greene,P.J., Betlach,M.C., Heyneker,H.L. and Boyer,H.W. (1977) Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. II. A multipurpose cloning system. Gene, 2, 95–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brejc K., Sixma,T.K, Kitts,P.A., Kain,S.R., Tsien,R.Y., Ormo,M. and Remington,S.J. (1997) Structural basis for dual excitation and photoisomerization of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 2306–2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger A.T. et al. (1998) Crystallography and NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D, 54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calahorra M., Martinez,G.A., Hernandez-Cruz,A. and Pena,A. (1998) Influence of monovalent cations on yeast cytoplasmic and vacuolar pH. Yeast, 14, 501–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey J.L., Coley,A.M., Tilley,L.M. and Foley,M. (2000) Green fluorescent antibodies: novel in vitro tools. Protein Eng., 13, 445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattoraj M., King,B.A., Bublitz,G.U. and Boxer,S.G. (1996) Ultra-fast excited state dynamics in green fluorescent protein: multiple states and proton transfer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 8362–8367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chau M.H. and Nelson,J.W. (1991) Direct measurement of the equilibrium between glutathione and dithiothreitol by high performance liquid chromatography. FEBS Lett., 291, 296–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark D.J. and Maaløe,O. (1967) DNA replication and the division cycle in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol., 23, 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Cody C.W., Prasher,D.C., Westler,W.M., Prendergast,F.G. and Ward,W.W. (1993) Chemical structure of the hexapeptide chromophore of the Aequorea green fluorescent protein. Biochemistry, 32, 1212–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debarbieux L. and Beckwith,J. (1999) Electron avenue: pathways of disulfide bond formation and isomerization. Cell, 99, 117–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Giorgi F. et al. (1999) Targeting GFP to organelles. Methods Cell Biol., 58, 75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derman A.I., Prinz,W.A., Belin,D. and Beckwith,J. (1993) Mutations that allow disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli. Science, 262, 1744–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederich L., Roth,A., Messer,W. (1994) A versatile plasmid vector system for the regulated expression of genes in Escherichia coli. Biotechniques, 16, 916–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsliger M.A., Wachter,R.M., Hanson,G.T., Kallio,K. and Remington,S.J. (1999) Structural and spectral response of green fluorescent protein variants to changes in pH. Biochemistry, 38, 5296–5301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert H.F. (1990) Molecular and cellular aspects of thiol–disulfide exchange. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol., 63, 69–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert H.F. (1995) Thiol/disulfide exchange equilibria and disulfide bond stability. Methods Enzymol., 251, 8–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassetti D.R. and Murray,J.F.,Jr (1967) Determination of sulfhydryl groups with 2,2′- or 4,4′-dithiodipyridine. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 119, 41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison P.M. and Sternberg,M.J. (1996) The disulphide β-cross: from cystine geometry and clustering to classification of small disulphide-rich protein folds. J. Mol. Biol., 264, 603–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim R., Prasher,D.C. and Tsien,R.Y. (1994) Wavelength mutations and posttranslational autoxidation of green fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 12501–12504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren A. (1989) Thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 13963–13966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber-Wunderlich M. and Glockshuber,R. (1998) A single dipeptide sequence modulates the redox properties of a whole enzyme family. Fold. Des., 3, 161–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang C., Sinskey,A.J. and Lodish,H.F. (1992) Oxidized redox state of glutathione in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science, 257, 1496–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye S. and Tsuji,F.I. (1994) Evidence for redox forms of the Aequorea green fluorescent protein. FEBS Lett., 351, 211–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob U., Muse,W., Eser,M. and Bardwell,J.C. (1999) Chaperone activity with a redox switch. Cell, 96, 341–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman S., Haggie,P., Wachter,R.M., Remington,S.J. and Verkman,A.S. (2000) Mechanism and cellular applications of a green fluorescent protein-based halide sensor. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 6047–6050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonda S., Huber-Wunderlich,M., Glockshuber,R. and Mossner,E. (1999) Complementation of DsbA deficiency with secreted thioredoxin variants reveals the crucial role of an efficient dithiol oxidant for catalyzed protein folding in the bacterial periplasm. EMBO J., 18, 3271–3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosower N.S. and Kosower,E.M. (1978) The glutathione status of cells. Int. Rev. Cytol., 54, 109–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis P. (1991) MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of proteins. J. Appl. Crystallogr., 24, 946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Krause G., Lundstrom,J., Barea,J.L., Pueyo,D.L.C. and Holmgren,A. (1991) Mimicking the active site of protein disulfide-isomerase by substitution of proline 34 in Escherichia coli thioredoxin. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 9494–9500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T.Y. and Kim,P.S. (1989) Urea dependence of thiol–disulfide equilibria in thioredoxin: confirmation of the linkage relationship and a sensitive assay for structure. Biochemistry, 28, 5282–5287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locker J.K. and Griffiths,G. (1999) An unconventional role for cytoplasmic disulfide bonds in vaccinia virus proteins. J. Cell Biol., 144, 267–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loferer H., Wunderlich,M., Hennecke,H. and Glockshuber,R. (1995) A bacterial thioredoxin-like protein that is exposed to the periplasm has redox properties comparable with those of cytoplasmic thioredoxins. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 26178–26183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J.L. (1995) Thioredoxin—a fold for all reasons. Structure, 3, 245–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt E.A. and Bacon,D.J. (1997) Raster3D: photorealistic molecular graphics. Methods Enzymol., 277, 505–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki A., Llopis,J., Heim,R., McCaffery,J.M., Adams,J.A., Ikura,M. and Tsien,R.Y. (1997) Fluorescent indicators for Ca2+ based on green fluorescent proteins and calmodulin. Nature, 388, 882–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaza J. and Saludjian,P. (1997) AMoRe: an automated molecular replacement program package. Methods Enzymol., 276, 581–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson B., Berman-Marks,C., Kuntz,I.D. and Anderson,S. (1991) Secretion incompetence of bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor expressed in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 2970–2977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa H., Inouye,S., Hirano,T., Matsuno,T., Kojima,S., Kubota,M., Ohashi,M. and Tsuji,F.I. (1996) Chemical nature of the light emitter of the Aequorea green fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 13617–13622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormo M., Cubitt,A.B., Kallio,K., Gross,L.A., Tsien,R.Y. and Remington,S.J. (1996) Crystal structure of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein. Science, 273, 1392–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z. and Minor,W. (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol., 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm G.J. and Wlodawer,A. (1999) Spectral variants of green fluorescent protein. Methods Enzymol., 302, 378–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz W.A., Aslund,F., Holmgren,A. and Beckwith,J. (1997) The role of the thioredoxin and glutaredoxin pathways in reducing protein disulfide bonds in the Escherichia coli cytoplasm. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 15661–15667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid B.G. and Flynn,G.C. (1997) Chromophore formation in green fluorescent protein. Biochemistry, 36, 6786–6791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remington S.J. (2000) Structural basis for understanding spectral variations in green fluorescent protein. Methods Enzymol., 305, 196–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddles P.W., Blakeley,R.L. and Zerner,B. (1979) Ellman’s reagent: 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid)—a reexamination. Anal. Biochem., 94, 75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietsch A. and Beckwith,J. (1998) The genetics of disulfide bond metabolism. Annu. Rev. Genet., 32, 163–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost J. and Rapoport,S. (1964) Reduction-potential of glutathione. Nature, 201, 185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Slonczewski J.L., Rosen,B.P., Alger,J.R. and Macnab,R.M. (1981) pH homeostasis in Escherichia coli: measurement by 31P nuclear magnetic resonance of methylphosphonate and phosphate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 78, 6271–6275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart E.J., Aslund,F. and Beckwith,J. (1998) Disulfide bond formation in the Escherichia coli cytoplasm: an in vivo role reversal for the thioredoxins. EMBO J., 17, 5543–5550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szajewski R.P. and Whitesides,G.M. (1980) Rate constants and equilibrium constants for thiol–disulfide interchange reactions involving oxidized glutathione. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 102, 2011–2026. [Google Scholar]

- Topell S., Hennecke,J. and Glockshuber,R. (1999) Circularly permuted variants of the green fluorescent protein. FEBS Lett., 457, 283–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien R.Y. (1998) The green fluorescent protein. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 67, 509–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuggle C.K. and Fuchs,J.A. (1985) Glutathione reductase is not required for maintenance of reduced glutathione in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol., 162, 448–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachter R.M., Elsliger,M.A., Kallio,K., Hanson,G.T. and Remington,S.J. (1998) Structural basis of spectral shifts in the yellow-emission variants of green fluorescent protein. Structure, 6, 1267–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachter R.M., Yarbrough,D., Kallio,K. and Remington,S.J. (2000) Crystallographic and energetic analysis of binding of selected anions to the yellow variants of green fluorescent protein. J. Mol. Biol., 301, 157–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wouters M.A. and Curmi,P.M. (1995) An analysis of side chain interactions and pair correlations within antiparallel β-sheets: the differences between backbone hydrogen-bonded and non-hydrogen-bonded residue pairs. Proteins, 22, 119–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunderlich M. and Glockshuber,R. (1993) Redox properties of protein disulfide isomerase (DsbA) from Escherichia coli. Protein Sci., 2, 717–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Moss,L.G. and Phillips,G.N.,Jr (1996) The molecular structure of green fluorescent protein. Nature Biotechnol., 14, 1246–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng M., Aslund,F. and Storz,G. (1998) Activation of the OxyR transcription factor by reversible disulfide bond formation. Science, 279, 1718–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]