Abstract

We have identified a new protease in Escherichia coli, which is required for its viability under normal growth conditions. This protease is anchored in the inner membrane and the gene encoding it has been named ecfE, since it is transcribed by EσE polymerase. Multicopy expression of the ecfE gene was found to turn down expression of both EσE- and Eσ32-transcribed promoters. Purified EcfE degrades both heat shock sigma factors RpoE and RpoH in vitro. EcfE has a zinc binding domain at the N-terminus, a PDZ-like domain in the middle and a highly conserved tripeptide, LDG, at the C-terminus. These features are characteristic of members of a new class of proteases whose activity occurs close to the inner membrane or within the inner membrane. Temperature-sensitive mutants of this gene were isolated mapping to the catalytic site and other domains that exhibited constitutively elevated levels of both heat shock regulons.

Keywords: EcfE/heat shock regulation/protease/RpoE/RpoH

Introduction

The heat shock response is a highly conserved phenomenon. In Escherichia coli, upon heat shock, synthesis of a number of proteins is induced rapidly. This response is under the control of two alternative heat shock sigma (σ) factors, RpoH and RpoE. RpoH controls the synthesis of >30 proteins, most of them involved in protein folding (DnaK/J, GroEL/S) and protein degradation, such as Lon and Clps proteins (for review, see Gross, 1996; Yura et al., 2000).

The rpoE regulon is also induced by heat shock and controls the synthesis of >25 proteins (Dartigalongue et al., 2001). Some of the products of RpoE-controlled genes are also involved in protein folding (surA, fkpA, dsbC and skp) and lipid biogenesis (lpxD/A, rfaD and others) (Dartigalongue et al., 2001). It is now established that these two heat shock regulons seem to control and respond to protein misfolding in specific compartments. While rpoH responds to protein misfolding in the cytoplasm, rpoE responds to protein misfolding in the extracytoplasm (for review, see Missiakas and Raina, 1997; Raivio and Silhavy, 2000).

Both heat shock responses are tightly regulated at several levels. The heat shock response mediated by rpoH depends on the transient increase in the levels of RpoH. RpoH is normally very unstable with a half-life of <1 min (Tilly et al., 1989; Morita et al., 2000). Many factors contribute to this unusual instability. FtsH (HflB), an integral membrane protein, has been shown to be responsible for the proteolysis of RpoH (Herman et al., 1995; Tomoyasu et al., 1995), based on the findings that the stability of RpoH is increased in ftsH mutants and that FtsH degrades RpoH in vitro. However, this FtsH-mediated degradation under in vitro conditions is extremely slow, and observed mostly for a 30-fold excess of protease over the substrate (Tomoyasu et al., 1995). Further, it has been suggested that FtsH-mediated turnover required the C-terminus of RpoH (Blaszczak et al., 1999). However, genetic experiments do not support a role for the C-terminus in its in vivo stability (Nagai et al., 1994; Arsene et al., 1999; Morita et al., 1999).

Further genetic studies showed that hslV/U (clpQ/Y) gene products are also involved in modulation of the rpoH-controlled heat shock response (Missiakas et al., 1996). HslV/ClpQ shares homology with β-type catalytic subunits of the 20S proteosome. It has been further shown that the HslV/U complex can degrade RpoH in vitro (Kanemori et al., 1999). In vivo, HslV/U, ClpA/P and Lon participate in the turnover of RpoH (Kanemori et al., 1997), but it is difficult to evaluate the relative contribution of these proteases (for review, see Yura et al., 2000).

The availabilty of other alternative σ factors is also tightly controlled. For example, rpoE is controlled at the transcriptional level via two promoters. One of them is autoregulated (Raina et al., 1995; Rouviere et al., 1995). RpoE availability is also modulated at the post-translational level by interaction with a specific anti-σ factor, RseA. rseA is the second gene of the four-gene rpoE rseA rseB rseC operon (De Las Penas et al., 1997; Missiakas et al., 1997). It has been reported that DegS controls the degradation of RseA, which could relieve the inhibitory effect of RseA on RpoE upon the induction of envelope stress (Ades et al., 1999). However, under all growth conditions a stoichiometry of 2:5:1 for RpoE:RseA:RseB, respectively, has been observed (Collinet et al., 2000). The mechanism responsible for this stoichiometry is unknown.

The present study addresses the role of additional gene(s) whose product(s) may be controlling this complex heat shock response. Here, we report identification of a gene designated ecfE, whose product modulates the levels of both RpoE and RpoH σ factors. ecfE was isolated because in multicopy it decreased the activity of both rpoE- and rpoH-transcribed promoters. We show that purified EcfE can degrade RpoE as well as RpoH in vitro in sub-stoichiometric amounts. We also show that ecfE is an essential gene. EcfE shares homology with the recently identified protease S2P (Site-2 Protease), a membrane-anchored protease (Ye et al., 2000). S2P protease cleaves the N-terminal domains of membrane-bound sterol regulatory element binding proteins (Brown et al., 2000; Ye et al., 2000). EcfE also shows some homology in the catalytic domain with Bacillus subtilis sporulation protein SpoIVFB. SpoIVFB has been shown to be necessary for the processing of σ factor σK (Rudner et al., 1999). Sequence comparison with the available microbial genomes shows that EcfE homologues are present in all eubacteria except Mycoplasma.

Results

Identification of the ecfE gene

We have been interested in the σE regulon as well as regulation of rpoE activity and turnover of another heat shock σ factor RpoH. Here, we looked for multicopy clones in a p15A-based vector that reduced the activity of EσE-regulated promoters. With this approach, we previously cloned the rseA gene, whose product negatively regulates RpoE activity, since it acts as an anti-σ factor specific to RpoE. To avoid recloning the rseA gene, we constructed a multicopy library using chromosomal DNA isolated from a strain carrying a null mutation in rseA. This library was used to isolate clones that turned off the EσE-regulated promoters htrA–lacZ, rpoEP2–lacZ and rpoHP3–lacZ.

Since the heat shock response is elicited upon protein misfolding, we also tested whether these plasmids also affected the rpoH regulon. These plasmids were transformed into strains carrying Eσ32-transcribed promoters, namely groEL–lacZ, rpoDPhs–lacZ, ftsH–lacZ and lon:: Mu53–lacZ. Most of these plasmids were also found to similarly reduce the transcription of rpoH regulon. Analysis using different restriction enzymes identified 25 plasmids carrying identical DNA fragments. Three such plasmids were randomly chosen and sequenced. The sequence analysis of the three clones showed that they contained the cdsA gene (encoding CDP-diacylglycerol synthase) and a hypothetical ORF designated yaeL, which corresponds to the 4.3 min region of the chromosome.

We first tested whether the cdsA gene in multicopy was responsible for decreased EσE or Eσ32 activity. We did not find any influence of clones that contained the cdsA gene alone on the multicopy plasmid (pSR3657) as compared with the parental plasmid (pSR3612) carrying the second ORF yaeL. We named this ORF ecfE after analysing its unction and its transcriptional regulation. The ecf gene designation is based on its identification as part of the σE regulon (Dartigalongue et al., 2001). Based on our transcriptional mapping of the ecfE promoter (Dartigalongue et al., 2001) and previous work, it appears that ecfE is transcribed as a three-gene operon, in the order uppS cdsA ecfE.

Overall we observed that the basal level activity of RpoE-regulated promoters is reduced by a factor of 4- to 7-fold upon EcfE overexpression (Table I). ecfE-bearing plasmids reduced the activity of Eσ32-transcribed promoters by a factor of 2- to 4-fold (Table I). The lesser effect was observed with the groEL–lacZ fusion-bearing strain. This promoter fusion also has a Eσ70 promoter, which masks the effect on the Eσ32-dependent promoter. To confirm that the effect is specific to these heat shock regulons, we also tested four different promoters transcribed by other σ factors. We used htrL–lacZ and htrP–lacZ (RpoD transcribed), pspA–lacZ (RpoN transcribed) and dps–lacZ (RpoS transcribed). The data presented in Table I show no significant changes in the expression of these promoters upon ecfE overexpression. Among these fusions we deliberately used fusion to pspA and dps genes since it is known that pspA is also induced by a variety of stresses including heat shock but is not controlled by rpoH, and that dps is strongly induced in stationary phase under the control of rpoS (Altuvia et al., 1997). RpoS, quite like RpoH, is an unstable protein and in this way we also rule out the possibility that the EcfE overexpression effect may be on labile proteins in general.

Table I. The effect of ecfE overexpression on the heat shock response.

| Strains | Regulated by | Vector alone | p(ecfE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| htrA–lacZ | RpoE | 100 ± 9 | 23 ± 5 |

| rpoHP3–lacZ | RpoE | 78 ± 7 | 19 ± 5 |

| rpoEP2–lacZ | RpoE | 350 ± 15 | 49 ± 6 |

| groEL–lacZ | RpoH | 720 ± 30 | 330 ± 17 |

| lon–lacZ | RpoH | 360 ± 21 | 53 ± 7 |

| rpoDPhs–lacZ | RpoH | 83 ± 7 | 21 ± 4 |

| ftsJ/H–lacZ | RpoH | 470 ± 37 | 140 ± 15 |

| htrP–lacZ | RpoD | 1510 ± 74 | 1570 ± 91 |

| htrL–lacZ | RpoD | 230 ± 19 | 225 ± 19 |

| dsp–lacZ | RpoS | 15 200 ± 520 | 16 000 ± 140 |

| pspA–lacZ | RpoN | 73 ± 7 | 69 ± 7 |

Isogenic cultures of bacteria carrying fusions to different RpoE-regulated promoters, RpoH-regulated promoters and those transcribed by other σ factors in the presence of a plasmid carrying ecfE were analysed for β-galactosidase activity (Miller units). Bacterial cultures were grown overnight in LB broth at 30°C, diluted 1:100 and allowed to reach an OD595 of 0.2 for monitoring β-galactosidase activity. Samples were assayed in duplicate and the data presented here are the average of three independent experiments.

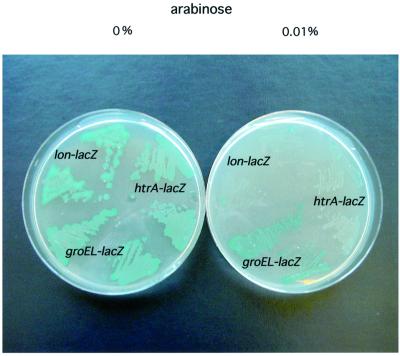

A minimal clone carrying the ecf gene under the arabinose-inducible promoter vector pBAD24 (pSR4173) was also tested. Introduction of this plasmid into strains carrying EσE or Eσ32 promoters led to a decrease in the expression of the corresponding promoters depending on the amount of inducer used (Figure 1). Concentrations of arabinose >0.2% render E.coli very sick, and further such arabinose-dependent EcfE overproduction leads to complete growth arrest at temperatures >42°C.

Fig. 1. EcfE induction represses the heat shock response and suppresses the mucoidy of a lon mutant. Strains carrying promoter fusions under the control of RpoE (htrA–lacZ) or RpoH (groEL–lacZ and lon::Mu53–lacZ) were transformed with plasmid pSR4173 (pBAD24-ecfE+). Two independent transformants were streaked on LB plates containing X-gal to visualize reporter gene activity. ecfE expression was induced with 0.01% arabinose in the plate and is shown on the right side.

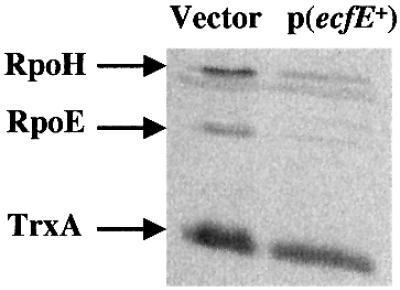

Levels of RpoE and RpoH in vivo upon overexpression of ecfE

To verify that overexpression of ecfE was directly affecting the two heat shock regulons, we examined the levels of RpoE and RpoH in isogenic derivatives of strain LMG194 with pBAD24 vector either alone or carrying the ecfE gene. Expression of ecfE was turned on with the addition of inducer arabinose (0.01%) and after 2 h, cell extracts were analysed by western blotting using RpoE and RpoH antisera. As can be seen in Figure 2, the levels of RpoE and RpoH protein are reduced upon overexpression of ecfE while the amount of the control protein TrxA remains unchanged. A quantitative measurement shows an ∼12-fold reduction in RpoE amount as compared with an ∼6-fold reduction in the amount of RpoH.

Fig. 2. Induction of ecfE leads to a reduction in the levels of RpoE and RpoH. Cultures of LMG194 strain carrying pBAD24 or pSR4173 (pBAD24-ecfE+) were grown in M9 medium with glucose at 30°C. At an OD595 of 0.2, cultures were centrifuged, washed and resuspended in M9 medium containing 0.01% arabinose for ∼2 h. Total cell extracts were analysed by SDS–PAGE, followed by western blotting with a mixture of anti-RpoH, anti-RpoE and anti-TrxA antibodies.

ecfE is an essential gene under normal growth conditions in E.coli

We recently reported that ecfE is an essential gene (Dartigalongue et al., 2001). We constructed two null alleles by inserting an ΩKan cassette at BsiWI and SmaI sites. Such disrupted ecfE alleles were transferred to the gene replacement vector pKO3 (Link et al., 1997). Recombination on to the chromosome occurred only in the presence of plasmid pSR4173 (pBAD-ecfE+) (Dartigalongue et al., 2001). In order to establish that ecfE is essential, we constructed a merodiploid strain carrying λecfE+ on the chromosome at the λ attachment site and then repeated the gene replacement experiment. Only in this situation could we resolve the ecfE::ΩKan and obtained the null allele at the chromosomal location and the wild-type gene at λecfE+. To rule out that essentiality was not due to any polar effect on the downstream gene, we inserted an ΩKan cassette in the downstream ORF (yaeT, renamed ecfK; Dartigalongue et al., 2001). We could easily transfer the null allele to the downstream gene using conventional genetic techniques. No obvious phenotype was observed, hence the essentiality of the ecfE gene product has nothing to do with the downstream ORF ecfK.

Subcellular localization of EcfE

ecfE is predicted to encode a 450 amino acid polypeptide. The amino acid sequence examination of EcfE predicted it to be an inner membrane protein with five putative transmembrane protein helices spanning 5–24, 55–73, 99–123, 379–400 and 426–444 (predicted from the programs DAS and TMpred at EMBnet).

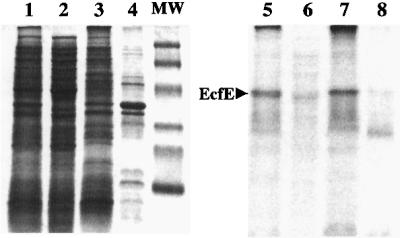

To confirm the inner membrane localization, we performed the following experiments. First, we induced the synthesis of ecfE by cloning ecfE under a tightly controlled T7 promoter expression system (pSR4932). The total cell extract was fractionated by sonication to separate soluble versus insoluble fractions (containing aggregates, inner and outer membrane). The inner membrane fraction was released by Sarkosyl treatment (Figure 3). As can be seen, most of the EcfE protein was solubilized by Sarkosyl (Figure 3, lanes 3 and 7). These results are further supported by the purification of EcfE from inner membrane fraction.

Fig. 3. Subcellular fractionation of EcfE. Strains carrying pSR4932 (pET22b-ecfE+) were grown at 37°C in M9 medium. Protein production was induced by the addition of 0.01 mM IPTG. After 30 min induction, cells were treated with rifampicin (200 µg/ml) for another 30 min and then labelled with [35S]methionine (50 µCi/ml) for 10 min. Cell extracts were submitted to fractionation as described in Materials and methods. Proteins were resolved by SDS–PAGE (12.5%) and visualized both by Coomassie Blue staining and by autoradio graphy of the dried gel (lanes 5–8). Lanes 1 and 5 represent total cell extract. Lanes 2 and 6 show the soluble fraction (soluble), and lanes 3 and 7, and 4 and 8 show inner membrane fraction (IM) and outer membrane fraction (OM), respectively. The molecular weight markers correspond to 110, 76, 49, 35.6, 29 and 19 kDa and were obtained from Bio-Rad.

Mutational analysis of ecfE

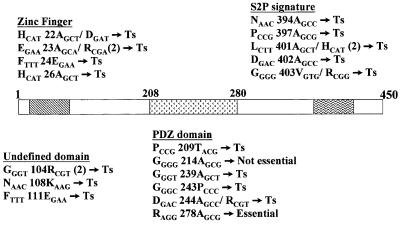

Examination of the amino acid sequence of EcfE shows three interesting features. First, EcfE has a potential zinc binding ‘H22EFGH26’ motif. This motif is right at the end of the first transmembrane domain facing the cytoplasm. The second motif is a conserved PDZ domain spanning amino acid residues 208–280. PDZ domains are present in a variety of proteins with different functions (Pallen and Ponting, 1997; Bezprozvanny and Maximov, 2001). The third feature is characterized by the presence of a highly conserved C-terminal amino acid sequence N394XXP- XXXLDG403 also found in the human S2P protease. H22, E23 and H26 of the zinc binding motif were changed to A using plasmid pSR4173 (pBAD-ecfE+) as a template. Based on sequence alignment of various PDZ domains, we chose to change by site-directed mutagenesis the G214, G239, D244 and R278 residues of EcfE to A. To test the role of conserved C-terminal amino acids we constructed the following changes: N394, P397, L401 and D402 to A and G403V. To check whether any of these residues play any critical role in the activity of EcfE, the following experiments were performed. First, we tested whether these plasmids encoding the respective ecfE mutants affected heat shock regulation. As shown in Figure 4A, none of the mutants could down-regulate either σE- or σ32-transcribed promoters, unlike the wild-type ecfE, with the exception of G214 to A. Also overexpression of these mutant proteins did not result in toxicity or growth arrest.

Fig. 4. Residues important for EcfE activity. Conserved residues in the predicted zinc binding domain, PDZ domain and undefined regions of EcfE were mutated using plasmid pSR4173 (pBAD24-ecfE+). Mutant plasmids were transformed in an appropriate background to examine their effect on the RpoE- and RpoH-dependent heat shock response (A). β-galactosidase activities were measured as explained for Table I. (B) Induction of heat shock response in ecfE chromosomal point mutants. All the point mutants were transferred to the chromosome in strains carrying either htrA–lacZ or lon–lacZ fusion and assayed for β-galactosidase activity.

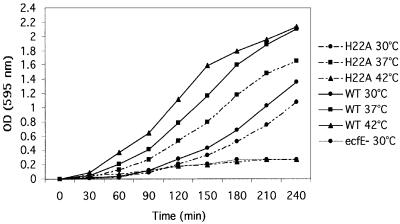

Secondly, we tested whether they have a phenotype when transferred to the chromosome in single copy using the bacteriophage λ red-mediated recombination. The mutant alleles were transferred to the plasmid that carries the ΩKan null inserted 700 nucleotides downstream of the ecfE gene stop codon. PCR-amplified DNA fragments carrying mutant alleles along with the ΩKan were transformed into strain DY 392 (Yu et al., 2000) and first selected for Kan resistance. The correct mutations were transduced into wild-type background carrying different EσE- or Eσ32-transcribed promoter fusions. We could transfer G214A to the chromosome without any obvious phenotype. However, other alleles behaved differently. DNA fragments carrying the respective changes H22, E23, G239, D244, N394, P397, L401 and D402 to A and G403V could be transferred to the chromosome but not the DNA fragment carrying R278A. Transfer of the R278A mutation to the chromosome was achieved only in a merodiploid strain. The rest of the mutants displayed a temperature-sensitive (Ts) phenotype and showed a constitutive, high basal level activity of the EσE- or Eσ32-transcribed promoter (Figures 4B and 5). The growth analysis of ecfE point mutant H22A was compared at 30, 37 and 42°C. The data presented in Figure 6 show clearly that the strain carrying the active site point mutant shows a decline in growth rate at both 37 and 42°C. This is more acute at 42°C as compared with the isogenic wild type and hence leads to lack of colony forming ability at high temperature. Also, the strain carrying the ecfE conditional null allele does not grow at any of these temperatures unless a wild-type copy is provided in trans. The data for the ecfE conditional are presented only at 30°C since they do not grow at any other temperature. These results argue that the putative zinc binding motif and NXXPXXXLDG motif are needed for EcfE activity in modulating heat shock response but are not essential for the viability of E.coli below 41°C.

Fig. 5. Schematic presentation of various ecfE point mutants. All the point mutations generated either by site directed mutagenesis or by localized mutagenesis are shown. All the mutants are in a single copy on the chromosome. The thermosensitive phenotype is indicated as Ts and numbers in parenthesis indicate the number of times a particular mutant allele was isolated. The exact nucleotide change in each case is indicated.

Fig. 6. Growth curves of isogenic strains with ecfE+, ecfE H22A and ecfE conditional null alleles. Exponentially growing cultures at 30°C were diluted 1:100 into prewarmed LB medium and incubated at 30, 37 and 42°C. For ecfE conditional null, arabinose was depleted from the medium and replaced with 0.2% glucose. Bacterial growth was monitored by measuring the OD595 after various time intervals.

Isolation of Ts mutant alleles in ecfE

In a complementary approach we further isolated Ts mutants of the ecfE gene on the chromosome. To achieve this, we used the ecfK::Kan null mutant strain (ecfK is located downstream of ecfE) and isolated Ts mutants linked to this Kan marker that led to increased expression of the RpoH and RpoE regulons. This was achieved by hydroxylamine mutagenesis of P1 bacteriophage grown on ecfK::Kan. Such lysates were used in transduction of the KanR marker into strain using rpoH-regulated rpoDPhs– lacZ fusion. rpoDPhs is a relatively weak promoter and it was easier to score for Lac up mutants. We isolated 45 independent Ts mutants, which simultaneously show constitutively high β-galactosidase activity of rpoDPhs– lacZ. Only those mutants which were ∼90% linked to KanR and the Ts phenotype were retained. Twenty-nine mutants were kept and checked for complementation by ecfE plasmid (pSR4173). Of them, 15 mutants were retained since they were fully complemented by the minimal ecfE-containing plasmid. All 15 mutants isolated were transduced into strains carrying rpoE-regulated promoters like htrA–lacZ, rpoHP3–lacZ or rpoEP2–lacZ. In all cases they showed a 5- to 7-fold induction of LacZ activity at 30°C (Figure 4B). We also transduced them into the strain carrying the lon–lacZ promoter fusion. Again an ∼4-fold induction was observed (Figure 4B). The chromosomal DNA from these mutants was sequenced. Interestingly, some of the mutations were mapped to the catalytic HEXXH site and L and G residues of the NXXPXXXLDG motif at the C-terminus (Figure 5). The Ts phenotype, heat shock expression (for some of the mutants) are shown in Figures 4B and 5. The results are summarized and the exact nucleotide changes depicted in Figure 5.

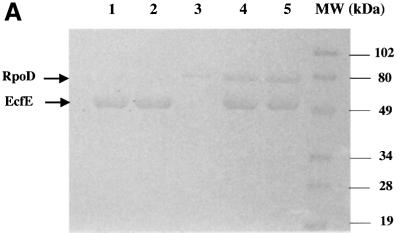

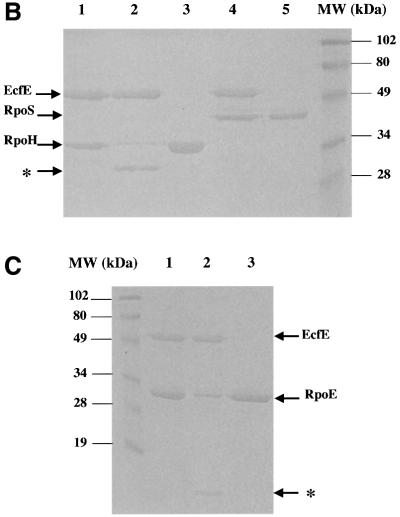

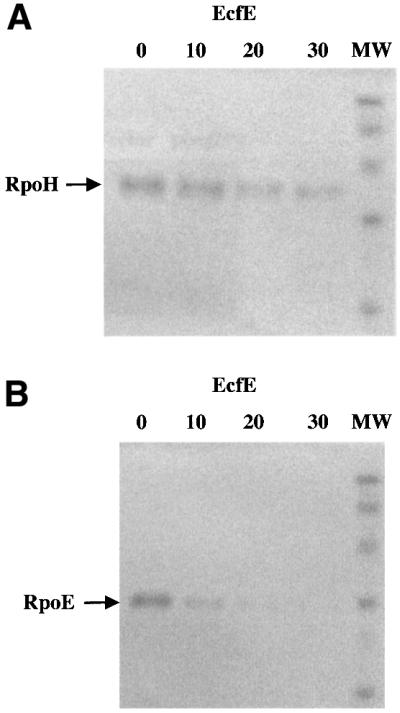

Purified EcfE degrades RpoH and RpoE

In multicopy, the ecfE gene down-regulates the two heat shock regulons, and point mutations in this gene have elevated heat shock levels. One explanation for this behaviour and consistent with the sequence prediction is that EcfE acts as a protease, degrading RpoE and RpoH. To test this, the EcfE–6His variant carrying a 6 × histidine tag fused to the C-terminus was purified. As mentioned earlier, overexpression of the ecfE gene is toxic, making it extremely difficult to purify the protein. EcfE–His6 was recovered from the inner membrane fraction, by solubilizing using 0.3% Sarkosyl, dialysed in Tris–HCl 50 mM pH 7.5 containing 0.5% Triton X-100 and purified over Ni-NTA beads. The purified protein was pre-incubated in the presence of 100 µM ZnCl2 and assayed for its activity on purified RpoE, RseA and RpoH as substrates. One microgram of each protein substrate was added to 10, 20 and 30 ng of EcfE protein and incubated for 30 min at 25°C. The reaction mixture was analysed by loading samples on to a SDS–polyacrylamide gel followed by western blotting. RpoE, RpoH and RseA were visualized using specific antisera. As shown in Figure 7 there is a progressive decrease in the amount of RpoH or RpoE detected by western blot using specific antibodies (Figure 7A and B, respectively). The degradation of RpoE was somewhat more efficient than that of RpoH. Under similar conditions, we did not see any cleavage of the RseA anti-σ factor (data not shown). Thus, EcfE degrades the two σ factors RpoE and RpoH in sub-stoichiometric amounts. As a control we also purified the EcfE-H22A mutant protein (Figure 8). The mutant protein was inactive, further supporting the notion that the zinc binding motif is required for proteolytic activity (Figure 8B and C). Purified RpoD and RpoS proteins were used as a control to rule out the possibility that EcfE degrades σ factors in a non-specific manner (Figure 8A and B). For in vitro proteolytic assay the best conditions for RpoH were found with incubation at 37°C when EcfE was supplemented with 0.5% Triton X-100 and 0.5% Tween-20.

Fig. 7. Degradation of RpoE and RpoH using purified EcfE. One microgram of RpoE (A) or RpoH (B) was incubated with varying amounts of EcfE (0, 10, 20 or 30 ng) for 30 min at 25°C. The proteins were resolved by 12.5% SDS–PAGE, then transferred to a nitro cellulose membrane and analysed by western blotting with antibodies raised against RpoE (A) or RpoH (B). MW, molecular weight.

Fig. 8. Wild-type EcfE but not EcfE-H22A degrades RpoE and RpoH. The migration of EcfE, RpoD, RpoS, RpoH and RpoE is shown with arrows. (A) Lanes 1 and 2 show purified wild-type EcfE and EcfE-H22A proteins. Lane 3 shows purified RpoD. Lanes 4 and 5 show after 30 min incubation of RpoD with EcfE wild-type and EcfE-H22A protein at 25°C. (B) Lanes 3 and 5 show purified RpoH and RpoS, respectively. Lanes 2 and 4 show the protease assay with wild-type EcfE and RpoH or RpoS, respectively, after an incubation of 30 min at 37°C. Lane 1 shows results with incubation as above but with EcfE-H22A, using RpoH as the substrate. Lanes 2 and 4 show the protease assay with wild-type EcfE and RpoH and RpoS as the substrates. The asterisk on the left is for lane 2, which shows the accumulation of cleaved RpoH. (C) Lane 3 shows purified RpoE alone, lanes 2 and 3 show the protease assay with wild-type and EcfE-H22A proteins, respectively. Note the accumulation of degraded RpoE product near the bottom of the gel in lane 2 with wild-type EcfE, indicated by an asterisk. For (A) and (B), proteins were resolved by 12% SDS–PAGE and for (C) showing RpoE degradation, proteins were resolved by 15% SDS–PAGE. Proteins were visualized by Coomassie Blue staining.

The N-terminal domain of RpoH is susceptible to proteolysis

The exact region of RpoH contributing to its extreme susceptibility to proteolysis is not known. We used a newly developed in vivo assay for characterization of proteases and their substrates. This system is based on using an E.coli strain deficient in the cya gene [encoding adenyl cyclase (AC)] and expression of the cognate gene from Bordetella pertussis to give rise to a Cya+ phenotype. If the two subdomains T25 and T18 of Bordetella AC are in separate molecules, the cells exhibit a Cya– phenotype. The two subdomains are required for enzymic activity but can tolerate large in-frame polypeptide insertions without loss of enzymic activity. If a protein sequence inserted between the subdomains is cleaved by a protease, the cells will become Cya–. Two regions from RpoH (N-terminal residues M1–M156 and C-terminal residues T142–A284) were inserted between the subdomains of AC. Interest ingly, fusion with the N-terminal fragment rendered the cells partly Cya– indicating that they are likely to be impaired in AC activity. The β-galactosidase activity, which reflects the AC activity, declined 30-fold when an ecfE-encoding plasmid was provided in trans (Table II). Consistent with these results, when we tested the same N-terminal fusion in isogenic strains but carrying two mutant alleles, H22A and P209T, of ecfE, there was a marked stabilization of this fusion as reflected by the increased β-galactosidase activity and a Cya+ phenotype. In contrast, the fusion to the C-terminal domain was completely stable and cells remained Cya+ with the control plasmid. The introduction of the ecfE plasmid did not lead to a Cya– phenotype and no reduction in β-galactosidase activity was observed (Table II). Similarly there was no effect on the ecfE point mutant backgrounds. These results clearly argue that the N-terminal domain is the target for proteolysis in vivo.

Table II. The N-terminal domain of RpoH is susceptible to EcfE-mediated proteolysis.

| Vector | β-galactosidase activity (Miller units) |

|---|---|

| pKAC | 5500 ± 145 |

| pKAC (N-terminal rpoH) | 700 ± 50 |

| pKAC (N-terminal rpoH) + p(ecfE) | 25 ± 3 |

| pKAC (N-terminal rpoH) + p(ecfE- P209T) | 2500 ± 170 |

| pKAC (N-terminal rpoH) + p(ecfE- H22A) | 3700 ± 250 |

| pKAC (C-terminal rpoH) | 6500 ± 370 |

| pKAC (C-terminal rpoH) + p(ecfE) | 5900 ± 450 |

| pKAC (C-terminal rpoH) + p(ecfE- P209T) | 6700 ± 340 |

| pKAC (C-terminal rpoH) + p(ecfE- H22A) | 6100 ± 330 |

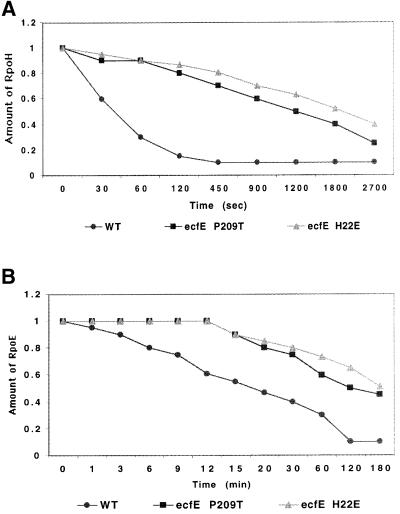

Stabilization of RpoH and RpoE in ecfE mutants

It is known that RpoH is extremely unstable, with a half-life of ∼30 s. Since our biochemical data show that EcfE can efficiently degrade RpoH in vitro at submolar concentrations, we examined the in vivo half-life of RpoH. As shown in Figure 9, the half-life of RpoH is increased in strains carrying mutant EcfE-P209T (SR4861) or EcfE-H22A (SR5070), from 45 s to ≥20 and 30 min, respectively (Figure 9A). The stabilization of RpoH might be even greater under non-permissive conditions.

Fig. 9. Stability of RpoE and RpoH in strains carrying ecfE point mutants. Cultures were pulse labelled for 20 s (time 0) and chased with cold methionine. Samples were taken at different intervals and immunoprecipitated with anti-RpoH (A) and anti-RpoE (B) antibodies and analysed by SDS–PAGE. The amounts of RpoE and RpoH were quantified by densitometry using a PhosphorImager.

We also determined the stability of RpoE in both wild type and the isogenic ecfE point mutants. RpoE is much more stable than RpoH. RpoE’s half-life as measured by pulse–chase experiments show that in wild-type it is ∼15 min. However, in the point mutants this half-life was increased to >120 min in the strain encoding EcfE-P209T and to >180 min in the strain encoding EcfE-H22A (Figure 9B). We did not detect any change in the half-life of the anti-σ factor RseA (data not shown) using the ecfE point mutants as compared with the isogenic wild-type.

Phenotypic characterization of EcfE point mutants

As mentioned above, we isolated ecfE point mutants on the basis of up-regulation of both heat shock regulons and temperature sensitivity. We examined these mutants for other phenotypes.

ecfE point mutants exhibited pleiotropic defects, including hypersensitivity to aminoglycoside antibiotics such as anikacin. ecfE point mutants did not grow at an anikacin concentration of >2 µg/ml, compared with wild-type, which can grow in anikacin up to 10 µg/ml. This probably reflects increased permeability of the outer membrane.

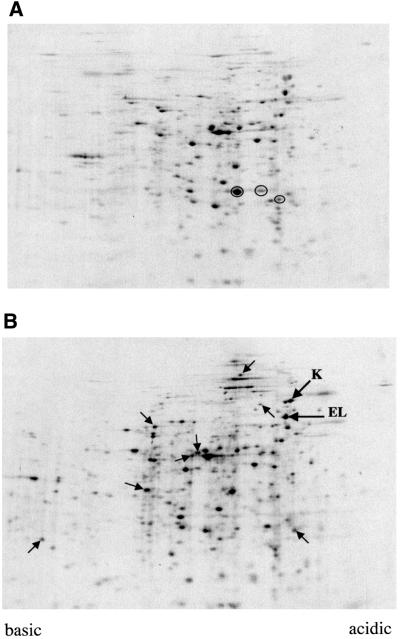

Effect of mutation in ecfE or depletion of EcfE protein on the overall protein profile

We performed several experiments to see the global effect on the protein profile. First, we performed two-dimensional SDS–PAGE analysis of isogenic strains MC4100 and SR4861 (ecfE point mutant). Culture were labelled with [35S]methionine and analysed by two-dimensional SDS–PAGE. As can be seen (Figure 10) there is an increased accumulation of major heat shock proteins such as DnaK and GroEL. However, we also see changes in the accumulation of many other proteins.

Fig. 10. Global changes in protein profile in ecfE mutant. Isogenic wild-type and an ecfE mutant strain were grown at 30°C to OD595 0.3 in M9 medium supplemented with glucose. Cells were labelled with [35S]methionine (50 µCi/ml) for 1 min. Cells were lysed and extracted with detergents (2% Nonidet P-40) and 8 M urea followed by several freeze–thawing cycles. The solubilized fraction was separated by charge electrophoresis using a mixture of ampholytes (1.6 and 0.4% in the pH ranges 5.0–7.0 and 3.5–10.0, respectively) in the first dimension and a 12.5% SDS–PAGE in the second dimension. Autoradiograms of the two-dimensional SDS–PAGE are shown: wild type (A) or ecfE P209T mutant (B). Circles in (A) identify proteins of lesser abundance in the ecfE mutant. Arrows in (B) identify proteins with increased abundance in the ecfE mutant. The letters K and EL identify DnaK and GroEL, respectively.

To further confirm these results, we carried out depletion experiments using the ecfE null allele on the chromosome and a wild-type gene present on a pBAD plasmid. Cells were depleted of EcfE by diluting out the arabinose contained in the growing medium. Samples were analysed by two-dimensional SDS–PAGE following various intervals of depletion. Protein spots were excised and analysed by tryptic digestion and MALDI-TOF analysis or by Edman degradation. The sequences of up-regulated as well as down-regulated proteins were compiled and analysed. The data presented in Table III show an increase in the accumulation of major outer membrane proteins (OMPs) upon depletion. Quantification of OMPs, which include OmpA, OmpF, OmpC and OmpX showed that they were up-regulated by at least 95%. In addition a protein involved in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) biogenesis, RfaD/HtrM, was also similarly increased in abundance upon the depletion of EcfE. The increased accumulation of RfaD/HtrM may be due to the induction of two promoters of the corresponding genes, which are under the control of Eσ32 or EσE RNA polymerase (Raina and Georgopoulos, 1991; Dartigalongue et al., 2001). We reported previously that the rfaD gene has a relatively strong rpoE-regulated promoter (Dartigalongue et al., 2001). There was also increased accumulation of putative inner membrane proteins YfgM, YbgI, both of which, from the recent microbial genome sequence analysis, are highly conserved, although no function has been assigned to them. Another protein, which was prominently induced upon depletion was the periplasmic oligopeptide binding protein OppA. Some of the proteins were also down-regulated upon depletion, including periplasmic proteins such as cystine binding protein and d-ribose binding protein (see Table III for more details).

Table III. Changes in protein profile upon depletion of EcfE.

| Protein | Protein level | Functions and localization |

|---|---|---|

| OmpA | up | major OMP |

| OmpC | up | major OMP |

| OmpF | up | major OMP |

| OmpX | up | major OMP |

| DnaK | up | protein folding, gene under σ32 control (cytoplasmic) |

| GroEL | up | protein folding, gene under σ32 control (cytoplasmic) |

| OppA | up | peptide binding protein (periplasmic) |

| HtrM/ RfaD | up | epimerase/LPS biogenesis (cytoplasmic) |

| ManC | up | colanic acid (cytoplasmic) |

| YfgM | up | highly conserved inner membrane protein |

| YbgI | up | highly conserved inner membrane protein |

| FecA | down | iron (III) dictrate transport (OMP) |

| FliY | down | cystine binding periplasmic protein (periplasmic) |

| GlyA | down | serine hydroxylmethyl transferase—interconversion of serine and glycine— key enzyme in biosynthesis of lipids and purines (cytoplasmic) |

| PpcK | down | phosphoenol pyruvate carboxykinase (cytoplasmic) |

| RbsB | down | d-ribose binding periplasmic protein (periplasmic) |

| SyfA | down | phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase α chain (cytoplasmic) |

| YeiP | down | belongs to elongation factor P family (cytoplasmic) |

The proteins that are more abundant or decreased upon depletion of EcfE are indicated by ‘up’ and ‘down’, respectively. Only the major changes (induction or reduction by 40% or more) as observed on two-dimensional SDS–PAGE are reported.

Induction of EcfE suppresses mucoidy of Lon mutants

It is known that mutations in the lon gene lead to a constitutive synthesis of colanic acid. This is due to stabilization of RcsA, a positive regulator for the transcription of cps genes, leading to overproduction of colanic acid (Jubete et al., 1996). During our analysis of EcfE overproduction effects on Eσ32-driven heat shock promoters, the fusion used was lon–lacZ. This transcription fusion is inserted in the lon gene (lon::Mu53–lacZ) and gives a Lon– phenotype which includes a mucoid phenotype. However, when the ecfE gene is induced with arabinose, the strain becomes non-mucoid. We further analysed this phenotype by introducing a Δlon::Tn10 insertion in strain MC4100 carrying the cpsB–lacZ fusion. The data presented in Table IV show that overexpression of ecfE reduces cps expression in a lon mutant. As a control, we used another plasmid carrying ecfE::ΩKan, which is identical to pSR4173, or the ecfE plasmid derivative encoding EcfE-H22A. In both cases there was no reduction of cps gene expression as measured by cps–lacZ activity.

Table IV. Effect of EcfE overproduction on the transcriptional activity of the cpsB gene.

| Strains (MC4100 background) | β-galactosidase activity (Miller units at 30°C) |

|---|---|

| cpsB–lacZ | 19 ± 2 |

| cpsB–lacZ + pBAD24 | 21 ± 3 |

| lon::Tn10, cpsB–lacZ + pBAD24 | 470 ± 23 |

| lon::Tn10, cpsB–lacZ + pBAD24 (ecfE+) | 65 ± 6 |

| lon::Tn10, cpsB–lacZ + pBAD24 (ecfE::ΩKan) | 457 ± 29 |

| lon::Tn10, cpsB–lacZ + pBAD24 (ecfE-H22A) | 430 ± 33 |

Discussion

EcfE is as a protease in E.coli

Degradation of RpoH. In this work, we have characterized a new essential protease in E.coli. The gene encoding this protease was obtained initially as a multicopy clone that reduced the expression of both Eσ32 and EσE heat shock regulons. Interestingly, RpoH is a highly unstable protein and many proteases have been implicated in its turnover (Maurizi et al., 1999; Morita et al., 2000; Yura et al., 2000). The most important role has been assigned to HflB (FtsH) protease based on in vivo and in vitro data (Herman et al., 1995; Tomoyasu et al., 1995). In this study we show that RpoH is also partially stabilized in vivo in strains carrying mutations in the ecfE gene. In addition, we show that purified EcfE can catalytically degrade RpoH. Purified EcfE-H22A protein did not exhibit any proteolytic activity. Also this mutant elicited heat shock response in vivo. H22 belongs to the H22EFGH26 zinc binding motif, found in a variety of metalloproteases (Brown et al., 2000). This motif is predicted to be at the end of the first potential transmembrane domain just near the cytoplasmic face. Earlier observations by Bukau et al. (1993) showed that a fraction of DnaK is always associated with the inner membrane. Since it is known that DnaK/DnaJ and RpoH interact physically (Gamer et al., 1992; Liberek and Georgopoulos, 1993), it is likely that RpoH might be targeted to EcfE proteolysis via an RpoH–DnaK–DnaJ complex.

Degradation of RpoE. RpoE is the only σ factor other than the housekeeping σ factor RpoD that is essential for growth in E.coli. Interestingly, we have shown recently that ecfE itself is part of the σE regulon (Dartigalongue et al., 2001). As pointed out, induction of ecfE transcription even under mild conditions leads to a reduction in RpoE activity as judged by the activity of reporter fusions htrA–lacZ, rpoHP3–lacZ and rpoEP2–lacZ as well as in vivo measurement of RpoE levels. These results cannot be an indirect effect on β-galactosidase degradation since the Eσ70-transcribed promoters htrL and htrP were unaffected. In addition, RpoE half-life was increased by at least 8-fold in a strain encoding the EcfE P209 mutant and 12-fold in a strain encoding the EcfE-H22A mutant. Our in vitro studies confirmed that RpoE is a good substrate for EcfE.

How is RpoE targeted to membrane proteolysis by EcfE in vivo? RpoE interacts with a cognate anti-σ factor RseA (De Las Penas et al., 1997; Missiakas et al., 1997). RseA is anchored to the inner membrane and a fraction of RpoE (36%) is always found to fractionate to the membrane in a RseA-dependent manner (Collinet et al., 2000). Hence, RpoE could be targeted to proteolysis in complex with RseA.

Why is EcfE essential in E.coli?

Altering the amounts of functional EcfE overexpression drastically alters the heat shock response. Such changes are obviously going to be harmful to the cells. As pointed out, the three other σ factors seem to be unaffected as judged by transcriptional fusions to rpoS-, rpoN- and rpoD-regulated promoters. Further, no degradation of RpoD and RpoS was observed in vitro in the presence of purified EcfE. Misregulation of the heat shock response can in part explain why EcfE is essential. However, the effect on heat shock response may not be the sole reason for the essentiality of EcfE. Most of the OMPs are overproduced upon depletion of EcfE in vivo. Over production of OMPs is known to induce the rpoE regulon (Mecsas et al., 1993). We also see some LPS components to be affected like RfaD. We have already shown that essential genes like lpxD/A fabZ are partly subject to rpoE regulation. Hence in the absence of EcfE there may be an imbalance in the amounts of some components involved in LPS and lipid A biogenesis since not all of their cognate genes are under the control of the rpoE gene. Also a number of periplasmic proteins are either increased in their abundance or are decreased. This suggests an overall defect in balancing the amounts of exported proteins. Together they may all contribute towards the essentiality of the ecfE gene. It is also likely some cell wall/cell division apparatus may be affected. It may be relevant to point out that ecfE homologues are present in all sequenced bacterial genomes but not in Mycoplasma, which lacks a cell wall. Clearly more detailed analysis of cell wall biogenesis in the ecfE mutants is needed.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table V.

Table V. Bacterial strains and plasmids.

| Relevant characteristics | Reference or source | |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| MC4100 | F– araD139 Δ(argF–lac) U169 | our collection |

| BL21 | ompT lon– | our collection |

| BL21(pLysE) | ompT lon– CmR | Invitrogen |

| DHT1 | F glnV44(AS) recA1 endA1 gyrA96 (Nalr) thi-1 hsdR17 spoT1 rfbD1 cya-854 ilv-691::Tn10 | Dautin et al. (2000) |

| GS043 | MC4100 φ (dps–lacZ) | Altuvia et al. (1997) |

| PJD31 | MC4100 φ (pspA–lacZ) | P.Model |

| SR933 | MC4100 φ (htrP–lacZ) | Raina et al. (1991) |

| SR1208 | MC4100 φ (groEL–lacZ) | Missiakas et al. (1993) |

| SR1421 | MC4100 φ (lon::Mu53–lacZ) | Missiakas et al. (1996) |

| SR1458 | MC4100 φ (htrA–lacZ) | Raina et al. (1995) |

| SR1588 | MC4100 φ (htrL–lacZ) | Missiakas et al. (1993) |

| SR1710 | MC4100 φ (rpoHP3–lacZ) | Raina et al. (1995) |

| SR2195 | MC4100 φ (rpoEP2–lacZ) | Raina et al. (1995) |

| SR3328 | MC4100 φ (rpoDPhs–lacZ) | this study |

| SR3556 | MC4100 rseA::Tn10 | Missiakas et al. (1997) |

| SR4496 | MC4100 φ (ftsJ/H–lacZ) | this study |

| SR4861 | MC4100 ecfE-P209T | this study |

| SR5070 | MC4100 ecfE-H22A | this study |

| |

||

| Plasmids | ||

| pKO3 | allelic replacement vector | Link et al. (1997) |

| pKAC | derivative of pSU40 | Dautin et al. (2000) |

| pSR1628 | pOK12 rpoE+ (1.4 kb Sau3A) | Raina et al. (1995) |

| pSR3612 | pOK12 (ecfE 2.9 kb Sau3A fragment) | this study |

| pSR3636 | pOK12 (ecfE 1.5 kb KpnI–AccI fragment) | this study |

| pSR3640 | pKO3 (ecfE with ΩKan at BsiWI) | this study |

| pSR3641 | pKO3 (ecfE with ΩKan at SmaI) | this study |

| pSR3657 | pOK12 (cdsA fragment) | this study |

| pSR4173 | pBAD (ecfE) | this study |

| pSR4932 | pET-22b (ecfE-His6) | this study |

| pSR 5096 | pET-22b (rpoS-His6) | this study |

| pCD73 | pBAD (ecfE-His6-myc) | this study |

| pCD951 | pKAC (rpoH-N-terminal fragment M1–M156) | this study |

| pCD953 | pKAC (rpoH-C-terminal fragment T142–A284) | this study |

Media and chemicals

Luria–Bertani (LB) broth, M9 and M63 minimal media were prepared as described by Miller (1992). When necessary, the media were supplemented with ampicillin (Amp, 100 µg/ml), tetracycline (Tet, 15 µg/ml), kanamycin (Kan, 50 µg/ml) or chloramphenicol (Cm, 20 µg/ml). The indicator dye 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactoside (X-gal) was used at a final concentration of 40 µg/ml in the agar medium. Different concentrations of arabinose were used depending upon experiment.

Genetic manipulation and cloning experiments to isolate the ecfE gene

First, a multicopy library was constructed using the p15A-based vector pOK12 (Vieira and Messing, 1991). Chromosomal DNA from strain SR3556 (rseA::Tn10Tet) was subjected to partial digestion with Sau3A. DNA fragments 2–5 kb in length were collected, purified and cloned into the BamHI site of pOK12 vector. This was done to eliminate the possibility of recloning the rseA gene. This library was used to isolate clones that decreased htrA–lacZ expression, using the strain SR1458 (Raina et al., 1995). The transformants were plated on X-gal-containing plates. White or pale blue colonies were retained and tested to verify that the promoter fusion htrA–lacZ was not lost. Plasmid DNA were transformed into strains carrying either htrA–lacZ, rpoEP2–lacZ or rpoHP3–lacZ fusions, to see if they bred true. About 70 such plasmids were retained and used to transform two strains carrying σ70-driven promoter fusions htrP–lacZ and htrL–lacZ, respectively, and three strains carrying different rpoH-regulated promoters, groEL–lacZ, rpoDPhs–lacZ and lon::Mu53–lacZ, respectively. These strains have been described previously (Raina et al., 1995; Missiakas et al., 1996). Thirty-seven plasmids that led to a strong repression of RpoE-regulated promoter fusions were also found to reduce the activity of all RpoH-regulated promoters tested. DNA restriction analysis of these 37 independent plasmids using various restriction enzymes showed that 25 of them contained a unique 2.3 kb SphI–HincII DNA fragment. Three of these clones were used for hybridization to the ordered E.coli genomic library (Kohara et al. 1987) by random priming using [α-32P]dATP. The DNA isolated from these clones was sequenced and a Blast search revealed the presence of the promoter-less cdsA gene followed by yaeL and the beginning of a third ORF. The minimal 1493 bp KpnI–AccI DNA fragment carrying yaeL/ecfE exclusively was constructed. This clone, pSR3636, was found to reduce the transcriptional activity of both RpoH- and RpoE-regulated promoters. For controlled expression, the ecfE gene was subcloned in vector pBAD24 under the control of arabinose-inducible pSR4173. For protein purification ecfE was cloned using NdeI–XhoI restriction sites in pET-22b vector using primers 5′-CGGAAGGTCATATGCTGAGT-3′ and 5′-CTAACTAACTCGAGTAACCGAGAG-3′ (pSR4932).

The DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession number for the sequenced ecfE gene is AF407012.

Insertion of ΩKan in the ecfE gene

The 2.3 kb SphI–HincII DNA fragment carrying ecfE was subcloned in the Ts replicon vector pKO3 (Link et al., 1997). This DNA fragment was made blunt by treatment with Klenow enzyme and inserted into pKO3 at SmaI site. The ΩKan cassette was inserted into the unique BsiWI and SmaI sites. The resulting clones were transformed into recA+ strain LMG194 and plated at 43°C for co-integrate formation. Gene replacement with the ecfE::Kan was obtained only when an extra copy of ecfE was provided in trans.

Mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out using the Quik Change procedure as described by the manufacturer (Stratagene). Plasmid pSR4173 was used as a template with the appropriate oligonucleotides. Such ecfE alleles were either subcloned into pKO3 vector or transferred to a plasmid carrying a kan cassette downstream of the ecfE gene. Various mutant alleles were transferred to the chromosome in single copy, in the presence or absence of plasmid pSR4173 (pBAD-ecfE+). Some of the mutant alleles were transferred to the chromosome using a λ red-mediated system (Yu et al., 2000).

Additional point mutants in the ecfE gene were obtained using the mutagen hydroxylamine

For this purpose, the gene immediately following ecfE, yaeT/ecfK (Dartigalongue et al., 2001), was disrupted by inserting an ΩKan cassette at NruI site using conventional techniques. The null allele was recombined to the chromosome using the pKO3 vector as described earlier, and transduced into MC4100. Linked mutagenesis to the KanR marker was carried out by growing bacteriophage P1 on ecfK::ΩKan and mutagenizing it with hydroxylamine as described earlier (Raina et al., 1995). This mutagenized lysate was transduced into strain SR3328 carrying rpoDPhs–lacZ and plated on agar containing X-gal (20 µg/ml) and kanamycin. The rpoDPhs–lacZ-carrying strain appears pale blue on such plates, as rpoDPhs is a relatively weak promoter. Two hundred deep blue KanR transductants were retained. Of these, 45 were found to be >90% linked to the KanR marker as well as Ts above 41°C. To verify that such strains carried mutation in the ecfE gene, they were tested for complementation using the ecfE+-containing plasmid pSR4173. Of them, 15 were retained and the nature of the mutation was determined by directly sequencing the PCR-generated DNA using oligonucleotides covering the ecfE gene, using standard procedures.

Purification of EcfE

BL21 strain pLysE was used as the host to purify EcfE. EcfE with a C-terminal His6 tag was expressed from vector pET-22b (pSR4932). This plasmid with EcfE appended to histidine tag did not interfere with EcfE activity, since it complemented ecfE point mutants just like the control plasmid (pSR4173). To induce the synthesis of the ecfE gene product, a 10 l culture of strain carrying pSR4932 was induced with 0.05 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at an OD at 595 nm (OD595) of 0.2 for 2 h. Cultures were harvested spun at 6000 g, at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer [50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl and 10 mM imidazole (buffer A) supplemented with lysozyme to a final concentration of 200 µg/ml]. The mixture was incubated on ice for 20 min, sonicated and spun at 100 000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The insoluble pellet was resuspended in buffer A containing 0.3% Sarkosyl at 4°C for 45 min to solubilize the inner membrane proteins. Solubilized proteins were recovered by centrifugation at 100 000 g for 45 min at 4°C. The supernatant was dialysed against 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 7.5 containing 0.5% Triton X-100 and 50 mM NaCl. Ten millilitres of this solution was applied to Ni-NTA beads (Qiagen), washed and eluted as recommended by the manufacturer. The mutant EcfE-H22A was purified in the same manner. RpoD–His6 was expressed using plasmid pCL391 and purified as described by Sharp et al. (1999). RpoS–6His was expressed using plasmid pSR5096 in Rapid translation system RTS 500 E.coli HY kit as described in the Roche Molecular Biochemical manual. The translation product was applied to Ni-NTA beads and eluted with imidazole. Purifications of RpoH, RpoE and RseA have been described previously (Raina et al., 1995; Collinet et al., 2000).

Biochemical assays

The protease assay for EcfE protein was carried out at 25°C using increased concentration of this protease and various substrates at a concentration of 1 µg each. The β-galactosidase assays were carried out as described by Miller (1992).

Stability of RpoE and RpoH

Bacterial cultures were grown in M9 medium supplemented with 0.2% glucose and labelled with 100 µCi/ml [35S]methionine for 20 s and chased with 100 µg/ml of cold methionine for various periods of time. Aliquots of cells were harvested at different intervals and immediately precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid. Protein samples were immunoprecipitated using either anti-RpoH or anti-RpoE antibodies. The complexes were concentrated by protein A–Sepharose beads (Pharmacia) and analysed by 12.5% SDS–PAGE. The incorporated radioactivity was quantified using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

Fractionation experiments

Cells were grown in LB broth at 37°C to an OD595 of 0.5. Cells were resuspended in 100 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM EDTA and incubated with 1 mg/ml of lysozyme for 20 min, followed by treatment with DNase I. Cells were lysed by multiple freeze–thaw. The lysate was centrifuged at 25 000g for 15 min. The supernatant containing all soluble proteins (periplasmic and cytoplasm) was removed. The pellet containing the membrane fractions and insoluble material was resuspended in 20 mM NaPO4 (pH 7.0) containing 0.5% Sarkosyl for 30 min at 20°C and spun at 100 000 g at 4°C for 30 min. The supernatant containing the inner membrane fraction was removed. The pellet containing the OMPs was washed with the same buffer and resuspended in SDS–PAGE sample buffer. Fractions were analysed by loading on to SDS–polyacrylamide gels (12.5%).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank R.Landick for the gift of the rpoD-encoding plasmid and D.Missiakas for the gift of RpoE antibodies and critical reading of this manuscript. We also thank S.Gottesman for valuable suggestions, and T.Posch and C.Gauss for two-dimensional gel and mass spectrometry analysis. This work was supported by a grant from the Fond National Scientifique Suisse (FN31-42429-94 and FN3100-059131.99/1) to S.R.

References

- Ades S.E., Connolly,L.E., Alba,B.M. and Gross,C.A. (1999) The Escherichia coli σ(E)-dependent extracytoplasmic stress response is controlled by the regulated proteolysis of an anti-σ factor. Genes Dev., 13, 2449–2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altuvia S., Weinstein-Fischer,D., Zhang,A., Postow,L. and Storz,G. (1997) A small, stable RNA induced by oxidative stress: roles as a pleiotropic regulator and antimutator. Cell, 90, 43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arsene F., Tomoyasu,T., Mogk,A., Schirra,C., Schulze-Specking,A. and Bukau,B. (1999) Role of region C in regulation of the heat shock gene-specific σ factor of Escherichia coli, σ32. J. Bacteriol., 181, 3552–3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezprozvanny I. and Maximov,A. (2001) PDZ domains: More than just a glue. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 787–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczak A., Georgopoulos,C. and Liberek,K. (1999) On the mechan ism of FtsH-dependent degradation of the σ32 transcriptional regulator of Escherichia coli and the role of the DnaK chaperone machine. Mol. Microbiol., 31, 157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M.S., Ye,J., Rawson,R.B. and Goldstein,J.L. (2000) Regulated intramembrane proteolysis: a control mechanism conserved from bacteria to humans. Cell, 100, 391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukau B., Reilly,P., McCarty,J. and Walker,G.C. (1993) Immunogold localization of the DnaK heat shock protein in Escherichia coli cells. J. Gen. Microbiol., 139, 95–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinet B., Yuzawa,H., Chen,T., Herrera,C. and Missiakas,D. (2000) RseB binding to the periplasmic domain of RseA modulates the RseA:σE interaction in the cytoplasm and the availability of σE.RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 33898–33904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dartigalongue C., Missiakas,D. and Raina,S. (2001) Characterization of the Escherichia coli σE regulon. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 20866–20875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dautin N., Karimova,G., Ullmann,A. and Ladant,D. (2000) Sensitive genetic screen for protease activity based on a cyclic AMP signaling cascade in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 182, 7060–7066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Las Penas A., Connolly,L. and Gross,C.A. (1997) The σE-mediated response to extracytoplasmic stress in Escherichia coli is transduced by RseA and RseB, two negative regulators of σE. Mol. Microbiol., 24, 373–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamer J., Bujard,H. and Bukau,B. (1992) Physical interaction between heat shock proteins DnaK, DnaJ and GrpE and the bacterial heat shock transcription factor σ 32. Cell, 69, 833–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross C.A. (1996) Function and regulation of the heat shock proteins. In Neidhardt,F.C. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp. 1382–1399.

- Herman C., Thevenet,D., D’Ari,R. and Bouloc,P. (1995) Degradation of σ 32, the heat shock regulator in Escherichia coli, is governed by HflB. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 3516–3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jubete Y., Maurizi,M.R. and Gottesman,S. (1996) Role of the heat shock protein DnaJ in the lon-dependent degradation of naturally unstable proteins. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 30798–30803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanemori M., Nishihara,K., Yanagi,H. and Yura,T. (1997) Synergistic roles of HslVU and other ATP-dependent proteases in controlling in vivo turnover of σ32 and abnormal proteins in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 179, 7219–7225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanemori M., Yanagi,H. and Yura,T. (1999) Marked instability of the σ(32) heat shock transcription factor at high temperature. Implications for heat shock regulation. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 22002–22007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohara Y., Akiyama,K. and Isono,K. (1987) The physical map of the whole E.coli chromosome: application of a new strategy for rapid analysis and sorting of a large genomic library. Cell, 50, 495–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberek K. and Georgopoulos,C. (1993) Autoregulation of the Escherichia coli heat shock response by the DnaK and DnaJ heat shock proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 11019–11023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link A.J., Phillips,D. and Church,G.M. (1997) Methods for generating precise deletions and insertions in the genome of wild-type Escherichia coli: application to open reading frame characterization. J. Bacteriol., 179, 6228–6237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurizi M.R., Wickner,S. and Gottesman,S. (1999) Chaperones and chaperonins: protein unfolding enzymes and proteolysis. In Bukau,B. (ed.), Molecular Chaperones and Folding Catalysts. Harwood Academic, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, pp. 381–404.

- Mecsas J., Rouviere,P.E., Erickson,J.W., Donohue,T.J. and Gross,C.A. (1993) The activity of σE, an Escherichia coli heat-inducible σ-factor, is modulated by expression of outer membrane proteins. Genes Dev., 7, 2618–2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J.H. (1992) A Short Course in Bacterial Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Missiakas D. and Raina,S. (1997) Protein misfolding in the cell envelope of Escherichia coli: new signaling pathways. Trends Biochem. Sci., 22, 59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiakas D., Georgopoulos,C. and Raina,S. (1993) The Escherichia coli heat shock gene htpY: mutational analysis, cloning, sequencing and transcriptional regulation. J. Bacteriol., 175, 2613–2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiakas D., Schwager,F., Betton,J.M., Georgopoulos,C. and Raina,S. (1996) Identification and characterization of HsIV HsIU (ClpQ ClpY) proteins involved in overall proteolysis of misfolded proteins in Escherichia coli. EMBO J., 15, 6899–6909. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiakas D., Mayer,M.P., Lemaire,M., Georgopoulos,C. and Raina,S. (1997) Modulation of the Escherichia coli σE (RpoE) heat-shock transcription-factor activity by the RseA, RseB and RseC proteins. Mol. Microbiol., 24, 355–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita M., Kanemori,M., Yanagi,H. and Yura,T. (1999) Heat-induced synthesis of σ32 in Escherichia coli: structural and functional dissection of rpoH mRNA secondary structure. J. Bacteriol., 181, 401–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita M.T., Kanemori,M., Yanagi,H. and Yura,T. (2000) Dynamic interplay between antagonistic pathways controlling the σ 32 level in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 5860–5865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai H., Yuzawa,H., Kanemori,M. and Yura,T. (1994) A distinct segment of the σ32 polypeptide is involved in DnaK-mediated negative control of the heat shock response in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 10280–10284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallen M.J. and Ponting,C.P. (1997) PDZ domains in bacterial proteins. Mol. Microbiol., 26, 411–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina S. and Georgopoulos,C. (1991) The htrM gene, whose product is essential for Escherichia coli viability only at elevated temperatures, is identical to the rfaD gene. Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 3811–3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina S., Mabey,L. and Georgopoulos,C. (1991) The Escherichia coli htrP gene product is essential for bacterial growth at high temperature: mapping, cloning, sequencing and transcriptional regulation of htrP. J. Bacteriol., 173, 5999–6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina S., Missiakas,D. and Georgopoulos,C. (1995) The rpoE gene encoding the σE (σ24) heat shock σ factor of Escherichia coli. EMBO J., 14, 1043–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raivio T.L. and Silhavy,T.J. (2000) Sensing and responding to envelope stress. In Storz,G. and Hengge-Aronis,R. (eds), Bacterial Stress Responses. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp. 19–32.

- Rouviere P.E., De Las Penas,A., Mecsas,J., Lu,C.Z., Rudd,K.E. and Gross,C.A. (1995) rpoE, the gene encoding the second heat-shock σ factor, σE, in Escherichia coli. EMBO J., 14, 1032–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudner D.Z., Fawcett,P. and Losick,R. (1999) A family of membrane-embedded metalloproteases involved in regulated proteolysis of membrane-associated transcription factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 14765–14770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp M.M., Chan,C.L., Lu,C.Z., Marr,M.T., Nechaev,S., Merritt,E.W., Severinov,K., Roberts,J.W. and Gross,C.A. (1999). The interface of σ with core RNA polymerase is extensive, conserved and functionally specialized. Genes Dev., 13, 3015–3026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilly K., Spence,J. and Georgopoulos,C. (1989) Modulation of stability of the Escherichia coli heat shock regulatory factor σ. J. Bacteriol., 171, 1585–1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomoyasu T. et al. (1995) Escherichia coli FtsH is a membrane-bound, ATP-dependent protease which degrades the heat-shock transcription factor σ32. EMBO J., 14, 2551–2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira J. and Messing,J. (1991) New pUC-derived cloning vectors with different selectable markers and DNA replication origins. Gene, 100, 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J., Dave,U.P., Grishin,N.V., Goldstein,J.L. and Brown,M.S. (2000) Asparagine-proline sequence within membrane-spanning segment of SREBP triggers intramembrane cleavage by site-2 protease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 5123–5128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu D., Ellis,H.M., Lee,E.C., Jenkins,N.A., Copeland,N.G. and Court D.L. (2000) An efficient recombination system for chromosome engineering in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 5978–5983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yura T., Kanemori,M. and Morita,M.T. (2000) The heat shock response: regulation and function. In Storz,G. and Hengge-Aronis,R. (eds), Bacterial Stress Responses. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp. 3–18.