Abstract

The sustainability of irrigated agriculture in many arid and semiarid areas of the world is at risk because of a combination of several interrelated factors, including lack of fresh water, lack of drainage, the presence of high water tables, and salinization of soil and groundwater resources. Nowhere in the United States are these issues more apparent than in the San Joaquin Valley of California. A solid understanding of salinization processes at regional spatial and decadal time scales is required to evaluate the sustainability of irrigated agriculture. A hydro-salinity model was developed to integrate subsurface hydrology with reactive salt transport for a 1,400-km2 study area in the San Joaquin Valley. The model was used to reconstruct historical changes in salt storage by irrigated agriculture over the past 60 years. We show that patterns in soil and groundwater salinity were caused by spatial variations in soil hydrology, the change from local groundwater to snowmelt water as the main irrigation water supply, and by occasional droughts. Gypsum dissolution was a critical component of the regional salt balance. Although results show that the total salt input and output were about equal for the past 20 years, the model also predicts salinization of the deeper aquifers, thereby questioning the sustainability of irrigated agriculture.

Keywords: regional hydrology, salinization, vadose zone

Salinization affects ≈20–30 million hectares (ha) of the world's current 260 million ha of irrigated land (1, 2) and limits world food production (3). Salinity reduces water availability to plants (4) by the accumulation of dissolved mineral salts in waters and soils due to evaporation, transpiration, and mineral dissolution. Subsequent salt leaching leads to salt buildup in both shallow groundwater below the plant root-zone (RZ) and deeper groundwater bodies (aquifers). The San Joaquin Valley, which makes up the southern portion of California's Central Valley, is among the most productive farming areas in the United States. However, salt buildup in the soils and groundwater is threatening its productivity and sustainability.

Currently, there is a good understanding of the fundamental soil hydrological and chemical processes (5) that control soil and groundwater salinity. Much of this understanding was achieved by using modeling approaches that consider the hydrology and soil chemistry separately, that assume simplified steady-state flow for spatial scales not larger than the field, and that only consider the RZ. However, recent research (6–11) has shown that soils must be fully coupled with the vadose zone and groundwater systems for regional-scale studies, especially in areas where groundwater tables are shallow or groundwater pumping is used (12). Innovative predictive tools are needed that can be applied at the regional scale and at the long term, so that the sustainability of alternative management strategies can be evaluated. For this purpose, an integrated regional-scale hydrosalinity model was developed to fully couple the hydrology and salt chemistry of the vadose zone with the groundwater system. This model enables us to reconstruct historical changes in soil and groundwater salinization in general and for the western San Joaquin Valley in particular (13).

Historical Context

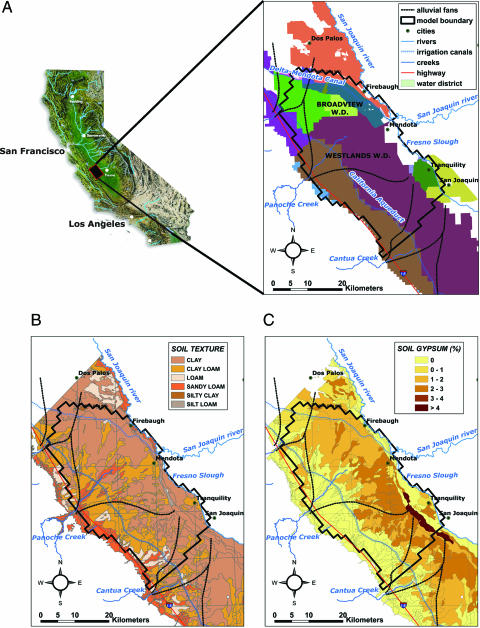

The study area represents a 1,400-km2 irrigated agricultural region in western Fresno County on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley (Fig. 1A) and includes three alluvial fans. The alluvial soils are derived from Coast Range alluvium and are generally fine-textured (Fig. 1B). Irrigation water is managed by water districts for water distribution and drainage management. Details on the hydrogeologic setting, soils, and history of irrigation are published elsewhere (6, 14, 15) and are summarized in Supporting Text and Fig. 5, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. Early irrigation in the valley, starting at the end of the 19th century, was limited to gravity diversions from the San Joaquin River and developed into intense groundwater pumping starting in the 1920s, leading to an increase in irrigated acreage westwards and upslope. After completion of the Central Valley Project and the State Water Project in 1953 and 1967, respectively, the whole study area was irrigated with high-quality imported water from the Sacramento Valley conveyed by the Delta-Mendota Canal and the California Aqueduct. These projects initially resulted in soil leaching of predevelopment salts. However, increased deep percolation rates combined with a sharp decrease in groundwater pumping resulted in a rise of the water table over much of the area (16). Since the mid-1980s the extent of saline-sodic soils has steadily migrated to the west, generally following the expansion of the shallow water table area [K. Arroues (2002), personal communication, Natural Resources Control Service, Hanford, CA].

Fig. 1.

Overview of the study area. (A) Location of the study area in the western San Joaquin Valley that includes 13 water districts (W.D.). (B) Soil texture map. (C) Soil gypsum contents. The main soil types are clay (52% of the study area), clay loam (35%), loam (4%), and sandy loam (9%). The finer-textured soils are found in the valley trough near the San Joaquin River. These soils have clay contents from 40% to 60%. The clay fraction is dominated by the montmorillonite mineral. Going from east to west, the soils gradually become more coarsely textured. A distinct feature is the sandy loam soils developed in stream deposits of Panoche Creek. Organic matter contents are low. Gypsum is predominantly present in the downslope soils. Soil data are from ref. 14.

The salinity problem on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley is partly attributed to the continuous presence of a low-permeability Corcoran clay layer (6), ranging in depths from ≈30 m near the San Joaquin River in the east to a depth of ≈250 m in the west, thereby largely defining the regional hydrology. To lower the water tables, subsurface drainage systems were installed to intercept and collect the shallow groundwater. Yet, soon thereafter it became eminently clear that drainage waters must be disposed off in an environmentally safe manner. Specifically, the 1983 discovery of migratory bird deaths and deformities was linked to elevated selenium levels in agricultural drainage water impounded in Kesterson Reservoir (17, 18). This finding led to an intensive investigation carried out jointly by federal and state agencies through the San Joaquin Valley Drainage Program (19). Current solutions include increasing irrigation efficiency, growing alternative salt-tolerant crops, drainage-water reuse, the collection of drainage water in evaporation ponds, land retirement, and increased groundwater pumping. However, for irrigated agriculture to remain sustainable, a soil salt balance must be maintained that allows for productive cropping systems.

Model Environment

The adapted modeling approach is based on the coupling of a soil chemistry module (20) with a regional-scale hydrology model (21) to yield an integrated approach for simulating three-dimensional variably saturated subsurface flow and reactive salt transport (13). The horizontal boundaries of the model domain coincided with the hydrologic boundaries of an earlier regional groundwater flow model (6), defined by the trough of the San Joaquin Valley on the east, the Coast Range foothills in the west, and no-flow boundaries in the north and south of the regional flow domain (Fig. 1 A). The model domain was discretized into a regular finite difference grid of 2,960 square cells of 805-m (0.5 mi) side length and 64-ha area, corresponding to a typical field size. In the vertical direction, the model domain extended from the land surface to the top of the Corcoran clay, using 17 layers of increasing thickness from the surface downwards. The total number of active model grid cells was 36,040. Hydrologic flows and salt transport were simulated for a 57-year period, from 1940 to 1997, using annual average boundary conditions and grid cell-specific soil parameters (Figs. 1 B and C and 5). The salinity module included reactions such as cation exchange and precipitation and dissolution of gypsum and calcite (22, 23). By using historical crop acreage and water delivery records for each water district, crops and irrigation amounts were randomly distributed, leading to the annual assignment of a single crop to each grid cell. Other required boundary conditions were needed to quantify vertical (across Corcoran clay and into deep groundwater) and lateral (toward San Joaquin River) water flow and salt fluxes and exchange between the simulated domain and its surroundings (13), so that an annual salt balance could be estimated. Spatially distributed water flow and salinity reaction and transport parameters were obtained from soil survey data and 242 well logs (more information is available in Supporting Text). Hydrological parameter values were either optimized (15, 24) or obtained from existing information (see Tables 1 and 2, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Results and Discussion: Salt Balance

Simulation model results included spatial maps of the groundwater table (see Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), drainage flows (15), and groundwater pumping (see Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), as well as regional water fluxes across the domain boundaries, starting in 1940. The hydrologic component simulated the dynamics of the regional variation in water table depths well (Fig. 6), reconstructing the gradual increase in shallow water table area from the 1950s to the 1990s because of increased recharge from irrigated agriculture compared with predevelopment conditions and the shift in irrigation water supply from locally pumped groundwater to imported surface water in the early 1970s.

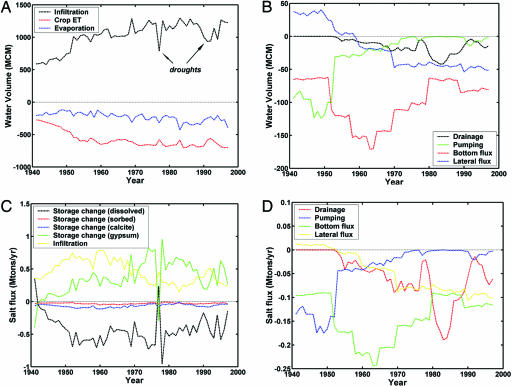

The steady increases in infiltration (positive) and crop evapo-transpiration (negative) reflect the increase in irrigated acreage during the first 30 years (Fig. 2A). The decrease in infiltration and increased pumping volumes in the mid-1970s and early 1990s reflect corresponding droughts that coincided with short periods of reduced drainage and deeper groundwater tables (13, 15). Initially, water moved into the simulated domain from the eastern boundary (positive). However, the direction reversed in the early 1970s, with water leaving the region laterally westwards (negative) toward the valley trough (lateral flux in Fig. 2B). Deep percolation of water through the Corcoran clay was highest during the 1950–1970 period (Fig. 2B), when pumping rates from the confined aquifer were the highest. As surface water was increasingly used, the hydraulic head gradient across the clay layer decreased, thus reducing deep percolation flows. Drainage flows were relatively small, starting in the late 1950s and reaching a maximum when the drainage systems in Westlands water district were operated from 1980 to 1985.

Fig. 2.

Simulated water and salt fluxes. (A and B) Annual-averaged water fluxes for the western San Joaquin Valley [million m3 (MCM) divide by 1,372 million m2 (after 1970) to describe fluxes in m/yr; i.e., 1,000 MCM/yr corresponds to 72.8 cm/yr]. (C and D) Salt balance (Mton/yr) for the western San Joaquin Valley. Positive fluxes designate incoming salt, whereas positive storage terms reflect a decrease in storage. Salt import by infiltration is controlled by ion concentrations of rainfall, surface water, and pumped groundwater. Drainage, bottom flux through Corcoran clay, and lateral salt fluxes toward the San Joaquin Valley trough were generally negative, indicating an export of salts. A major source of dissolved salt was due to gypsum dissolution (green). Respective maxima in 1977 were caused by reduced surface water applications during the drought. The temporary increase in salt export by drainage in the early 1980s was a result of the operation of the Westlands water district drainage system, which was permanently closed down in 1986.

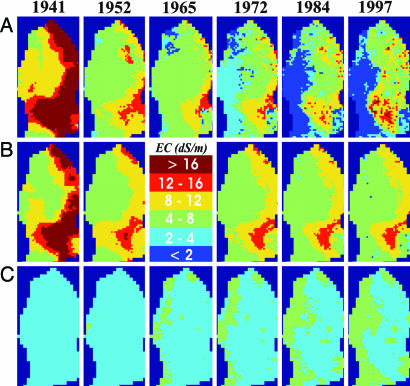

Much of the spatial and temporal dynamics in RZ and groundwater salinity were adequately described with the hydro-salinity model (Fig. 3; see also Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The salinity dynamics in the shallow groundwater generally followed that of the RZ, indicating that the two systems were closely connected. However, changes in salinity were typically less abrupt in shallow groundwater due to increased mixing of incoming and resident waters in the deeper layers. The relatively slow movement of salts to larger depths indicates that it takes a long time for salts to move into the deeper groundwater. Our model simulations demonstrated that a significant portion of the soil salinity dynamics was controlled by the cycling of soil gypsum through dissolution and precipitation (Fig. 2C), as caused by changes in salt leaching with time and soil depth, and soil cation exchange between Ca and Na (13, 22). This process leads to gypsum dissolution in the upper RZ with subsequent precipitation in the lower RZ and shallow groundwater, as well as high Na and SO4 concentrations in shallow groundwater (13).

Fig. 3.

Temporal changes in the spatial distribution of dissolved salts, expressed by the electrical conductivity (EC, dS/m) of the average RZ (0–2 m below the land surface) (A), the shallow groundwater system (SGW; 6 m below the land surface) (B), and the deep groundwater system (DGW; 20–40 m below the land surface) (C). Clearly shown is the initially high RZ salinity in the Panoche-Cantua interfan area (southwestern portion of the study area) and the uniformly low salinity in the DGW. After 10 years of irrigation (1952), part of the initial salinity was leached, resulting in a decrease in RZ salinity. Some of the initial salinity was still present in the SGW. The DGW system on the other hand remained low in salinity. Leaching of RZ salts continued in the initial simulation period, with a sudden decrease in RZ salinity after switching from groundwater to surface water for irrigation in the 1960s. As water levels started to rise in the eastern part of the study area during the 1970s and 1980s, RZ salinity levels increased again due to the simulated increase in irrigation efficiency and capillary rise followed by evaporation as water tables became shallower. This trend of increasing salinity continued through the 1990s. The higher soil salinity in Broadview water district (northern area) was higher than the surrounding areas due to recycling of saline drainage water there.

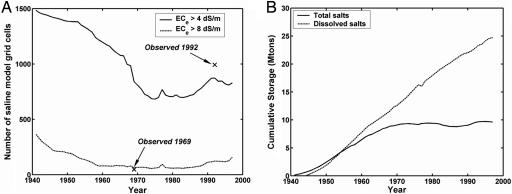

The corresponding soil salinity dynamics over the 57-year period (Fig. 4A) are represented by a time series of the number of model grid cells with a RZ average salt concentration (ECe) of >4 dS/m, which identifies the salt-affected soils. The few measured data points in Fig. 4A were derived from aggregating measured soil salinity data reported in 1969 and 1992 soil surveys. Initially, soil salinity was high in 1940 but decreased until ≈1975 due to salt leaching when water tables were relatively deep. According to the model, salt leaching occurred in three stages. The initial rate of decrease in soil salinity was low but increased first after 1953 and then even more after 1967, as less-saline imported canal water replaced the locally pumped groundwater as the main source of irrigation water. This general pattern of soil salinity decrease reversed during the 1970s, as continued irrigation raised the water table to levels that caused capillary rise of relatively high-salinity groundwater into the rooting zones. As groundwater levels rose toward the soil surface, less irrigation water was applied to prevent waterlogging. It in turn reduced salt leaching and increased soil salinity. The hydro-salinity model also reconstructed the effects of droughts in 1977 and 1991–1992, resulting in small peaks in soil salinity. The resulting increase in the extent of saline soils was caused by the substitution of surface water for irrigation with more saline groundwater (Fig. 2B) and possibly some by widespread land fallowing. Model simulations reproduced the measured increase of area with saline soils after 1970 (Fig. 4A), indicating that continued irrigation without changing management practices is not sustainable. The increase in the extent of highly saline soils since 1984 can be seen in Fig. 3A (red color in the southern part of the model domain). As a consequence, crop production has been adversely affected, and the land in this area has recently been retired (K. Arroues, personal communication).

Fig. 4.

Simulated salinity changes. (A) Time series of number of model grid cells with a simulated average RZ ECe > 4 dS/m (solid line) and >8 dS/m (dashed line). Symbols correspond to measured data. (B) Changes in total salt storage and dissolved salts (in Mton) since 1940.

When considering the salt-balance equation over an extended period without major hydrologic changes, a pseudoequilibrium will be approached, during which total salt inputs and outputs of the study area will be approximately equal (25). We note that the bottom of the model domain was the top of the Corcoran clay. Salt inflows occur by infiltration of irrigation water and rainfall (Fig. 2C), whereas salts may leave the system by the drainage system, groundwater pumping above the Corcoran clay, deep groundwater percolation through the Corcoran clay, and lateral groundwater flows toward the San Joaquin Valley trough (Fig. 2D). Moreover, much salt is produced by the net dissolution of gypsum (Fig. 2C). When analyzing the simulated annual total salt flows of the study area (Fig. 4B), the combined net influx was ≈0.3–0.4 million tons (Mton)/yr during the 1950s and 1960s, resulting in an increase in salt storage over time. However, although annual salt accumulations fluctuated later, depending on irrigation water quantity and quality and drought, the average net salt accumulation of the simulated domain appears to be near zero after 1970. The simulated cumulative change in salt storage over the 57-year simulation period (Fig. 4B) shows that a pseudoequilibrium developed after 1970, with a total net salt increase between 8 and 10 Mton since 1940. For example, in 1997, the salt input and output values were the same (Fig. 2 C and D), when the total salt input by irrigation water (0.23 Mton) was equal to salt removal by seepage through the Corcoran clay (0.12 Mton) and lateral groundwater flows toward the San Joaquin Valley trough along the eastern domain boundary (0.11 Mton). This equilibrium occurred despite the fact that much more water entered the study area by irrigation than was removed by vertical, lateral, and drainage flows (Fig. 2 A and B). Such pseudoequilibrium in salt storage can only occur if the salinity of the water inputs is much lower than that of the outputs. Indeed, simulations confirmed it to be the case. Although the salt-balance results indicate that crop productivity can be maintained, sustainability is threatened in two ways. First, the storage of dissolved salts has increased continuously since 1945 at an average rate of ≈0.5 Mton/yr (Fig. 4B) due to gypsum dissolution (Fig. 2C). Second, the simulations also showed that the deeper aquifers below the Corcoran clay accumulate salt, thereby degrading deep groundwater quality. By using 1997 again as an example, flow through the Corcoran clay at a rate of 80 million m3/yr (Fig. 2B) with a salt load of 0.12 Mton corresponds to an average salt concentration of 1,150 mg/liter (ppm) of the groundwater percolating through the Corcoran clay into the deeper groundwater. This process of salinization of the deeper groundwater bodies may take many decades or longer (26), thus making the deeper groundwater less suitable for drinking or irrigation water purposes and putting the sustainability of current irrigation practices into question. Indications (27) are that reversal of this process by reducing salt loads in the future may take even longer, because of diffusion control of low-permeable finer-grained aquifer materials.

We conclude that the salinization issues are critical to the sustainability of irrigated agriculture in the San Joaquin Valley and similarly probably to many other areas of the world with relatively closed groundwater systems. Our detailed historic simulations of soil and groundwater salinity in the San Joaquin Valley suggest that irrigation may not be sustainable. Future work should assess the robustness of these conclusions by means of a parameter sensitivity analysis and further field testing of the model simulations (see Supporting Text for further discussion). Although not considered in this study, accumulation of boron and selenium in soils of the San Joaquin Valley pose an additional threat to the sustainability of agriculture (28, 29).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank HydroGeologic Inc. for providing us with a beta version of the modhms model and Dr. Don L. Suarez (George E. Brown, Jr., Salinity Laboratory) for providing us with the unsatchem software. Our work has greatly benefited from insights by Kerry Arroues (Natural Resources Conservation Service) regarding soil salinization in the San Joaquin Valley. We thank Drs. Peter Vaughan, Dennis Corwin (both from George E. Brown, Jr., Salinity Laboratory), and Jim Ayars (U.S. Department of Agriculture Water Management Laboratory) for providing us with the irrigation/drainage and groundwater data for the Broadview Water District, without which some of the evaluation results would not have been possible. We also thank Gordon Huntington for providing us with the 1969 soil salinity map and Charles Brush (U.S. Geological Survey) for providing us with water delivery data. This work was supported by U.S. Department of Agriculture Funds for Rural America Project 97-362000-5263 and by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. J.A.V. was supported by the Earth Life Sciences and Research Council with financial aid from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research.

Author contributions: G.S., J.W.H., W.W.W., and K.K.T. designed research; G.S. and C.A.Y. performed research; J.A.V. and S.P. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; G.S., J.W.H., C.A.Y., J.A.V., and K.K.T. analyzed data; and G.S. and J.W.H. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: ha, hectares; Mton, million tons; RZ, root zone.

References

- 1.Tanji, K. K. & Kielen, N. C. (2002) Irrigation and Drainage Paper 61 (Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome).

- 2.Ghassemi, F., Jakeman, A. J. & Nix, H. A. (1995) Salinisation of Land and Water Resources: Human Causes, Extent, Management and Case Studies (Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies, Canberra, Australia).

- 3.Tilman, D., Cassman, K. G., Matson, P. A., Naylor, R. & Polasky, S. (2002) Nature 418, 671-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maas, E. V. & Grattan, S. R. (1999) in Agricultural Drainage, eds. Skaggs, R. W. & van Schilfgaarde, J. (American Society of Agronomy, Madison, WI), pp. 55-110.

- 5.Tanji, K. K. (1990) ASCE Manuals and Reports on Engineering Practices (American Society of Civil Engineers, New York), Vol. 71.

- 6.Belitz, K. & Philips, S. P. (1995) Water Resour. Res. 31, 1845-1862. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grismer, M. E. & Gates, T. K. (1991) in The Economics and Management of Water and Drainage in Agriculture, eds. Dinar, A. & Zilberman, D. (Kluwer Academic, Boston), pp. 51-70.

- 8.Deverel, S. J. & Fio, J. L. (1991) Water Resour. Res. 27, 2233-2246. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fio, J. L. (1997) J. Irrigation Drainage Eng. 123, 159-164. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corwin, D. L., Carrillo, M. L. K., Vaughan, P. J., Rhoades, J. D. & Cone, D. G. (1999) J. Environ. Qual. 28, 471-480. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alley, W. M., Heasly, R. W., LaBaugh, J. W. & Reilly, T. E. (2002) Science 296, 1985-1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey, C. F., Swartz, C. H., Badruzzaman, A. B. M., Keon-Blute, N., Yu, W., Ali, M. A., Jay, J., Beckie, R., Niedan, V., Brabander, D., et al. (2002) Science 298, 1602-1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoups, G. (2004) Ph.D. Dissertation (Univ. of California, Davis, CA).

- 14.Natural Resources Conservation Service (2003) Soil Survey Geographic (SSURGO) Database for Fresno County, California, Western Part (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Fort Worth, TX).

- 15.Schoups, G., Hopmans, J. W., Young, C. A., Vrugt, J. A. & Wallender, W.W. J. Hydrol., in press.

- 16.Belitz, K. & Heimes, F. J. (1990) Water Supply Paper no. 2348 (U.S. Geol. Survey, Sacramento, CA).

- 17.Committee on Long-Range Soil and Water Conservation, Board on Agriculture, National Research Council (1993) Soil and Water Quality (Natl. Acad. Press, Washington, DC).

- 18.Tanji, K. K., Lauchli, A. & Meyer, J. (1986) Environment 28, 6-11. [Google Scholar]

- 19.San Joaquin Valley Drainage Program (1990) A Management Plan for Agricultural Subsurface Drainage and Related Problems on the Westside San Joaquin Valley (San Joaquin Valley Drainage Program, Sacramento, CA).

- 20.Suarez, D. L. & Simunek, J. (1997) Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 61, 1633-1646. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panday, S. & Huyakorn, P. S. (2004) Adv. Water Resour. 27, 361-382. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schoups, G., Hopmans, J. W. & Tanji, K. K. Hydrological Processes, in press.

- 23.Tanji, K. K., Doneen, L. D. & Paul, J. L. (1967) Hilgardia 38, 319-329. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vrugt, J. A., Gupta, H. V., Bastidas, L. A., Bouten, W. & Sorooshian, S. (2003) Water Resour. Res. 39, 1214-1232. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orlob, G. T. (1991) in The Economics and Management of Water and Drainage in Agriculture, eds. Dinar, A. & Zilberman, D. (Kluwer Academic, Boston), pp. 143-167.

- 26.Weissmann, G. S., Zhang, Y., LaBolle, E. M. & Fogg, G. E. (2002) Water Resour. Res. 38, 1198-1211. [Google Scholar]

- 27.LaBolle, E. M. & Fogg, G. E. (2001) Transport Porous Media 42, 155-179. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banuelos, G. S. (1996) J. Environ. Sci. Health 31, 1179-1196. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldberg, S., Shouse, P. J., Lesch, S. M., Grieve, C. M., Poss, J. A., Forster, H. S. & Suarez, D. L. (2003) Plant Soil 256, 403-411. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.