Abstract

Polynucleotide phosphorylase synthesis is autocontrolled at a post-transcriptional level in an RNase III-dependent mechanism. RNase III cleaves a long stem–loop in the pnp leader, which triggers pnp mRNA instability, resulting in a decrease in the synthesis of polynucleotide phosphorylase. The staggered cleavage by RNase III removes the upper part of the stem–loop structure, creating a duplex with a short 3′ extension. Mutations or high temperatures, which destabilize the cleaved stem–loop, decrease expression of pnp, while mutations that stabilize the stem increase expression. We propose that the dangling 3′ end of the duplex created by RNase III constitutes a target for polynucleotide phosphorylase, which binds to and degrades the upstream half of this duplex, hence inducing pnp mRNA instability. Consistent with this interpretation, a pnp mRNA starting at the downstream RNase III processing site exhibits a very low level of expression, regardless of the presence of polynucleotide phosphorylase. Moreover, using an in vitro synthesized pnp leader transcript, it is shown that polynucleotide phosphorylase is able to digest the duplex formed after RNase III cleavage.

Keywords: degradation barrier/pnp/RNase III processing

Introduction

Expression of many bacterial genes is autocontrolled at the post-transcriptional level, e.g. most of the Escherichia coli ribosomal proteins are translationally autocontrolled. The mechanism described for the ribosomal proteins appears to be a general one in which each protein involved in autocontrol is able to recognize specifically (besides its primary target on rRNA) a site on its own messenger as a secondary target. Binding to this latter site prevents translational inititiation, accounting for autocontrol of the synthesis of the encoded protein.

There are other examples, however, where autocontrol is not linked to the blockage of ribosome loading on mRNA but to the induction of mRNA destabilization. Such a mechanism has been proposed for two endoribonucleases, RNase E (Jain and Belasco, 1995) and RNase III (Bardwell et al., 1989), as well as for an exoribonuclease called polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNPase) (Robert-Le Meur and Portier, 1992). In these cases, autoregulation is tightly correlated with the instability of their mRNA, which is triggered by a change in the structure of the mRNA leader. For RNase III, a specific cleavage near the 5′ end of its own mRNA removes a stem–loop, which acts as a degradation barrier (Matsunaga et al., 1996a,b). As a consequence, RNase III mRNA becomes unstable. A similar mechanism has been proposed for RNase E (Diwa et al., 2000). In the case of PNPase, a region of the mRNA leader necessary for autocontrol has been defined, but the mechanism of destabilization cannot be the direct result of the catalytic activity of PNPase, which is a 3′ to 5′ exoribonuclease. RNase III, which cleaves the pnp leader 81 nucleotides (nt) upstream of the initiation codon, is required for autoregulation (Robert-Le Meur and Portier, 1992), but it does not remove a degradation barrier because the pnp mRNA remains stable in the absence of PNPase (Robert-Le Meur and Portier, 1994). After RNase III cleavage, the pnp mRNA is destabilized, but only in a pnp+ strain, indicating that the RNase III cleavage must create a structure susceptible to specific recognition by PNPase. Although no specific RNA binding site has been described in PNPase, except for 3′-hydroxyl ends, it cannot be excluded that this enzyme is able to bind specifically to the processed 5′ end and change the secondary structure of the pnp mRNA leader. In fact, binding of PNPase to the 5′ end of RNA has already been observed (Sulewski et al., 1989). Two adjacent RNA binding domains, S1 (Régnier et al., 1987; Bycroft et al., 1997) and KH (Siomi et al., 1993), which are topologically distinct from the catalytic site (Godefroy, 1970; Symmons et al., 2000), might be involved in these specific RNA–protein contacts. Supporting this hypothesis, a point mutation, which affects PNPase autocontrol but not the catalytic activities, is located in the KH domain (Garcia-Mena et al., 1999). However, until now, analysis of several point mutations and deletions in the pnp leader has failed to identify any specific binding site (Robert-Le Meur and Portier, 1994; C.Portier, unpublished data). In this paper, changes affecting the structure of the processed pnp mRNA leader around the RNase III site have been analysed. The results show that there is no particular RNA site on the processed pnp mRNA leader devoted to specific PNPase binding. Instead, the autocontrol of pnp expression is the direct result of its 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity on the RNase III-cleaved transcript.

Results

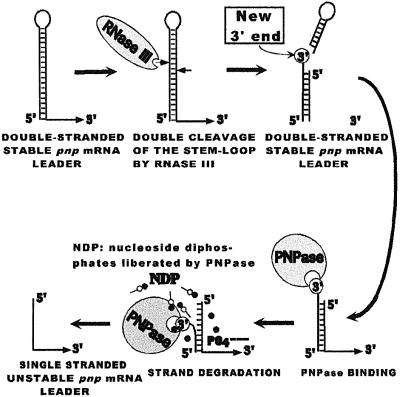

Strategy

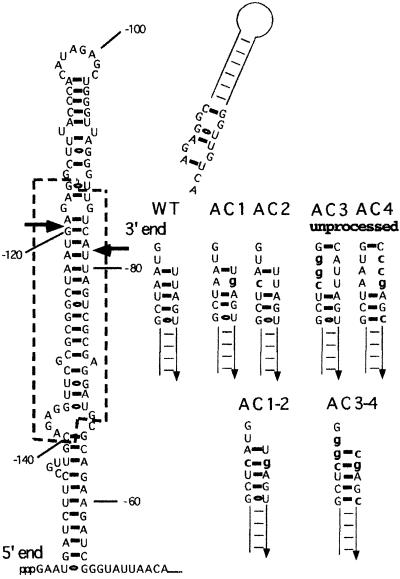

A long irregular stem–loop is predicted to form in the pnp leader carrying an RNase III site (Figure 1). RNase III cleavage of this long hairpin cuts the stem into two, releasing the upper part of the stem–loop. The lower part of the stem forms a double-stranded structure, which binds the upstream RNA of the stem–loop to the downstream pnp mRNA (Figure 1). This duplex, consisting of >20 bp, would not be expected to dissociate rapidly. Moreover, it has a 2 nt 3′ overhang carried by the upstream strand, which might be specifically recognized by PNPase. In this case, the upstream branch of the stem could be processively degraded by PNPase, thus removing the double-stranded structure at the 5′ end of the pnp messenger. Assuming that this duplex behaves as a barrier against pnp mRNA degradation, its removal could trigger degradation of the downstream pnp mRNA, as already observed for RNase III mRNA (Matsunaga et al., 1996b). If this hypothesis is true, any alteration to the thermodynamic stability of this duplex should affect mRNA decay rates and hence the expression of pnp, since there is a tight correlation between the stability of the pnp mRNA and its expression level (Robert-Le Meur and Portier, 1994).

Fig. 1. Predicted secondary structure in the pnp leader transcript and mutations created around the cleavage sites. The most thermo dynamically stable structure of the 5′ end pnp mRNA leader carrying the RNase III site was predicted by the MFOLD computer program (Zuker, 1989). Nucleotides framed by a dotted line are conserved in E.coli, Y.enterocolitica and Photorhabdus sp. Arrows point to the upstream and downstream RNase III cleavage sites previously determined by S1 mapping and primer extensions (Régnier and Portier, 1986). The new double-stranded ends of the duplex created by the RNase III cleavages of the pnp leader either in the wild-type strain (WT) or in different mutants are shown. In mutants AC3 and AC4, the pnp leader is unprocessed. Mutations are indicated by lower case letters. The sequence is numbered from the initiation codon.

The simplest way of changing RNA duplex stability is to introduce mutations disrupting base pairing in the stem. There is a potential problem in creating these mutations because of the presence of the RNase III cleavage site in this region. As RNase III processing is necessary for autocontrol, nucleotides that are thought to play a key role in determining the cleavage site (Zhang and Nicholson, 1997) should not be changed. These nucleotides are located essentially upstream and downstream of the cleavage site, but not in the 4 bp spanning this site (Nicholson, 1996, 1999; Zhang and Nicholson, 1997). Muta tions were introduced in the pnp leader mostly at these positions (Figure 1) and their effect on the expression of a pnp–lacZ fusion carried by a λ phage (Robert-Le Meur and Portier, 1992) analysed in a Δpnp lysogenic strain (CP5321F). Two point mutations, U-80G (mutant AC1) and A-123C (mutant AC2), near the 2 nt 3′ overhang disrupted an A–U base pair and were expected to favour fraying at the top of the stem. When combined (mutant AC1–2), the A–U base pair was changed to C–G, which created a more stable stem. Mutations U-121G and A-122G were added to mutant AC2 to give mutant AC3, and A-82C, U-81C and U-77C to mutant AC1 to give mutant AC4. In both these mutants, base pairing was disrupted over 3 nt, producing an internal loop in the stem at the processing site (Figure 1). In addition, the stability of the AC4 duplex was increased by changing a G·U pair into a G–C base pair (see Figure 1). When combined (mutant AC3–4), two G–C base pairs were created at the top of the processed stem, which, associated with the G–C base pair already present in AC4, considerably enhanced the stability of this stem.

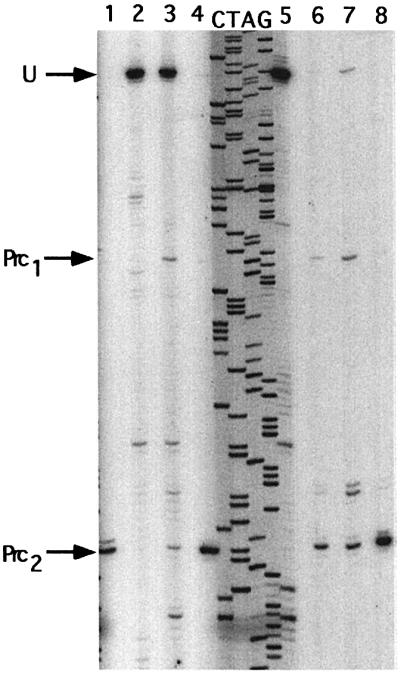

Effects of mutations in the RNase III cleavage site on pnp messenger processing

To check whether the mutations affected the processing efficiency by RNase III in vivo, total RNA was extracted from mutants grown at 30°C, and the amounts of processed and unprocessed pnp mRNAs were estimated by primer extension. In the wild-type construct, a single band was detected (Prc2) corresponding to the downstream RNase III site (Figure 2, lane 1). Mutant AC1–2 showed the presence of the same single processed band (lane 8), thus indicating the presence of a fully processed pnp mRNA leader in this strain. For mutants AC1 and AC2, a major band (Pcr2; Figure 2, lanes 6 and 7) corresponded to the processed messenger. Minor bands were also visible. Band Prc1, faint in AC1 (lane 6) but stronger in AC2 (lane 7), corresponded to the upstream processing RNase III site, suggesting that RNase III cleaved the upstream site more efficiently in these mutants and thus that processing might be asymmetrical. Other minor bands were detected in mutant AC2. They corresponded to a small amount of unprocessed pnp mRNA (U; Figure 2) and to an RNA 6 nt longer than the processed Pcr2 mRNA. Although the double mutation present in mutant AC1–2 did not affect the RNase III processing, this was not entirely true for mutants AC1 and AC2. Nevertheless, the effects observed remained quite limited.

Fig. 2. In vivo processing of mutated pnp leader mRNAs by RNase III. Total RNA was extracted from cultures of different mutants and processing of the pnp mRNA leaders analysed by primer extension using a lacZ probe. Sequencing of the corresponding DNA was carried out with the same probe to identify the cleavage points. Lane 1, wild-type pnp leader mRNA; lane 2, AC3; lane 3, AC4; lane 4, AC3–4; lane 5, GF490 (rnc–); lane 6, AC1; lane 7, AC2 and lane 8, AC1–2. U indicates the position of the unprocessed leader, while arrows Prc1 and Prc2 show, respectively, the position of the upstream and downstream RNase III cleavage sites. Notice that the 5′ end of the unprocessed pnp leader corresponds to a G (cf. lane 5), located 3 nt downstream of the A previously identified (Régnier and Portier, 1986).

The situation was quite different for mutants AC3 and AC4. In these mutants, RNase III processing of the pnp leader was severely reduced (mutant AC4, lane 3) or eliminated (mutant AC3, lane 2) and large amounts of the unprocessed mRNA (U; Figure 2) were detected. The mutations probably create an internal loop at the cleavage site, which inhibits cleavage by RNase III. On the other hand, the presence of the compensatory mutations restoring Watson–Crick base pairing and preventing the formation of the internal loop in mutant AC3–4 led to complete processing (Figure 2, lane 4). Some extra minor bands were present in mutants AC3 and AC4, one corresponding to the upstream RNase III processing site (Prc1 in mutant AC4) and two others at sites corresponding to 6 and 12 nt upstream of the downstream RNase III site, indicating that limited cleavage by RNase III or other unknown nucleases still occurs.

Effect of stem stability on pnp expression

As the stability of an RNA duplex is inversely related to temperature, the expression level of the mutants was measured in cells grown at 18, 30, 37 and 42°C. If the thermodynamic stability of the RNA duplex in the processed stem is involved in pnp mRNA decay rate, expression should be expected to decrease at higher temperatures. It should also reflect the effect of the mutations on the stability of the RNase III processed stem, but only in the context where RNase III processing occurs. It can be expected that mutations that inhibit processing should give the highest expression.

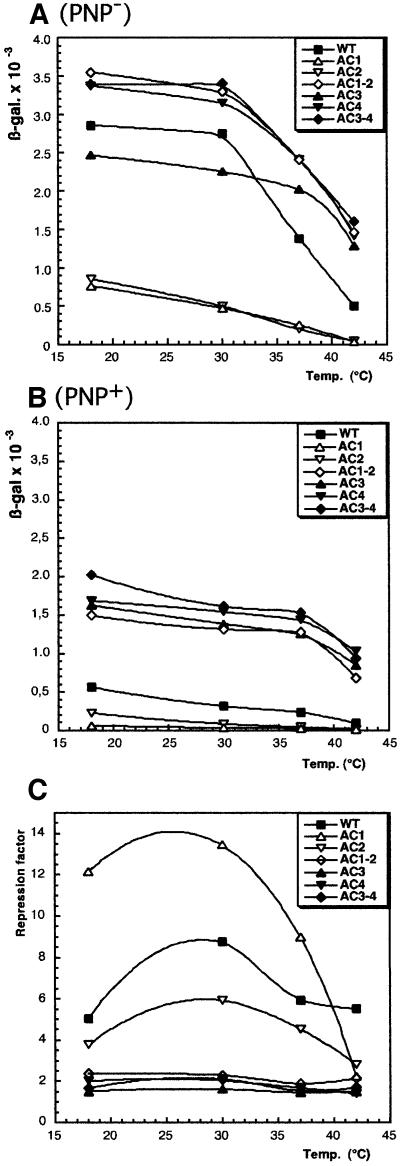

In the absence of PNPase. In a first set of experiments, expression of the fusions was measured in a strain lacking PNPase. Expression of the strain carrying the wild-type pnp leader (CP5321F) exhibited a biphasic curve (Figure 3A, filled squares); expression was quasi constant between 18 and 30°C, followed by a rapid decrease between 30 and 42°C. This pattern can be interpreted as if the duplex is stable until 30°C and then is melted rapidly above this temperature. Mutants AC1–2 and AC3–4 exhibited an increased expression of the pnp–lacZ fusion at all temperatures, as expected for mutations that increase the stability of the 5′ duplex end of the pnp leader (Figure 3A, open and filled diamonds). Moreover, this expression decreased only ∼2-fold between 30 and 42°C compared with 5-fold for the wild type between the same temperatures. A pattern similar to AC1–2 and AC3–4 was shown by AC4. Since the pnp leader of neither AC3 nor AC4 mutants was subject to efficient RNase III processing, expression was expected to be high from both of them. However, the expression level of AC3 was significantly lower than that of AC4 at 18 and 30°C for unknown reasons. A quite different result was observed with mutants AC1 and AC2, in which the pnp leader is destabilized, but still processed. In these cases, expression was low (∼5-fold lower than the wild type) even at 18°C and decreased steadily as the temperature was increased (Figure 3A, open triangles).

Fig. 3. Expression level of translational pnp–lacZ fusions carrying different mutations in their pnp mRNA leader. (A) In the absence of PNPase. (B) In the presence of PNPase. Cultures were grown at the temperatures indicated and β-galactosidase measured according to Miller (1972). Identification of the mutants is shown in the boxes. WT, wild type. Standard deviations were ∼10%. (C) Variation of the repression factor versus temperature. For each strain, the repression factor was calculated by dividing the β-galactosidase value in the absence of PNPase (A) by that in the presence of PNPase (B) at the same temperature.

Taken together, these results indicate that expression of the pnp–lacZ fusion does depend upon the stability of the processed duplex, supporting the hypothesis that the stem–loop behaves as a degradation barrier. Increasing temperature decreases expression of all the pnp–lacZ fusions >30°C. The effect is particularly strong for the wild-type case, which has three A–U base pairs at the top of the processed stem. Mutations disrupting these pairs show enhanced degradation at all temperatures.

In the presence of PNPase. When the mutations were tested in a wild-type strain expressing PNPase, a general decrease in the expression level was observed. Moreover, there was a smaller range of variation versus temperature (compare Figure 3A with B). Expression remained more or less constant between 18 and 37°C, and then decreased more rapidly at 42°C. The presence of PNPase repressed expression of the wild-type fusion at all temperatures, but the effect was maximum (∼8-fold) at 30°C (Figure 3C, filled squares). A similar pattern of repression was found for mutants AC1 and AC2 (Figure 3C, open triangles). The strongest repression (13-fold) was observed with mutant AC1, whereas with mutant AC2, the repression factor reached only 5-fold. The large difference in the repression factor between mutants AC1 and AC2 (Figure 3C) was unexpected because expression of these two mutants was already equally low in the absence of PNPase (Figure 3A). Minor differences in the RNase III processing rates of the pnp leaders of these mutants (see Figure 2, lanes 6 and 7) might induce slight differences in the efficiency of PNPase binding to the duplexes. For AC1 and AC2 mutants, repression by PNPase was only 2-fold at 42°C. A similar low repression factor was also observed, but at all temperatures, for all the other mutants, whether their pnp leader is processed by RNase III (AC1–2 and AC3–4; Figure 3B, filled and open diamonds) or not (AC3 and AC4; Figure 3B, black triangles). These observations indicate that RNase III processing is not necessary for this 2-fold repression by PNPase and that, consequently, this repression is independent of PNPase feedback regulation.

Overall, the only fusions specifically subject to strong repression by PNPase are the wild type and mutants AC1 and AC2, which carry mutations destabilizing the RNase III-cleaved stem. In all cases, it is obvious that specific repression is most efficient at or around 30°C and only occurs when the stem is unstable. Mutations (or temperature) that increase stem stability decrease repression efficiency and, conversely, mutations or temperature that destabilize the stem increase this efficiency.

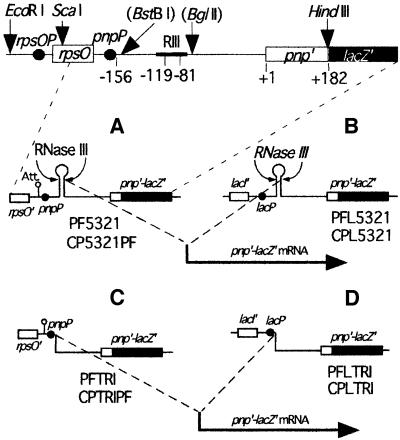

Expression of pnp is strongly decreased when transcription of its mRNA starts at a point corresponding to the downstream RNase III cleavage site

If the mRNA duplex created by RNase III at the 5′ end of the pnp mRNA is essential for maintaining pnp mRNA stability, elimination of this duplex should lead to an unstable mRNA, even in a strain lacking PNPase. A construct was made in which transcription from the pnp promoter was initiated at the position corresponding to the downstream RNase III cleavage site (Figure 4C). mRNAs initiated at this point will be referred to as ‘pre-processed’ because they should mimic the structure of the pnp mRNA leader after dissociation of the upper strand. The construct was transferred to the translational pnp–lacZ fusion, and expression of this fusion was measured in pnp+ (PFTRI) and Δpnp (CPTRIPF) strains in the presence and absence of a plasmid overexpressing PNPase (pBP111). The results were compared with those of the same fusion expressed from the full-size pnp leader region in the corresponding backgrounds, pnp+ (PF5321) and Δpnp (CP5321F; Table I). Expression from the full-size pnp transcripts followed the same pattern of autoregulation as observed previously, namely expression in the Δpnp strain was ∼10-fold higher than in a pnp+ strain and was repressed by an excess of PNPase (pBP111), as shown by the high repression factor. In contrast, expression from the pre-processed mRNA was very low in all conditions and it was not significantly affected by the absence or presence of PNPase, showing that the residual β-galactosidase activity was not subject to autoregulation by PNPase.

Fig. 4. Structural organization of translational pnp–lacZ fusions showing RNase III-processed or pre-processed transcripts. Top, overall organization of the pnp leader showing the position of the restriction sites used. Sites in parentheses were created by site-directed mutagenesis. Positions are numbered from the pnp initiation codon. (A) Transcription from the pnp promoter; the transcription starts from the pnp promoter (pnpP shown by a black dot) and is processed by RNase III, leading to the formation of a processed pnp–lacZ transcript. (B) The same construction as in (A) but with a lac promoter instead of the pnp promoter. (C) The DNA fragment between the wild-type transcription start site and the downstream RNase III cleavage point was removed (see Materials and methods) so that transcription from pnpP starts directly at the processing point, giving a pre-processed transcript. (D) As in (C), but with the lac promoter instead of the pnp promoter. Att, attenuator; rpsOP, rpsO promoter; pnpP, pnp promoter; lacP, lac promoter; ‘RNaseIII’ (or ‘RIII’) indicates the positions of the RNase III cleavage sites at –119 and –81. The names of strains carrying each fusion are indicated.

Table I. Expression of pnp–lacZ fusions from transcripts with a processed or pre-processed pnp leader.

| Promoter | pnp leader processing | Strains | pBR322 (control)a | pBP111 (pnp+)a | Repression factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pnpP | processed | pnp+ (PF5321) | 364 ± 44 | 111 ± 2 | 3.3 |

| processed | Δpnp (CP5321PF) | 3152 ± 325 | 104 ± 7 | 30.3 | |

| pre-processed | pnp+ (PFTRI) | 10 ± 1 | |||

| pre-processed | Δpnp (CPTRIPF) | 16 ± 3 | 11 ± 0.3 | 1.4 | |

| lacP | processed | pnp+ (PFL5321) | 544 ± 73 | 96 ± 14 | 5.7 |

| processed | Δpnp (CPL5321) | 1735 ± 170 | 101 ± 25 | 17.2 | |

| pre-processed | pnp+ (PFLTRI) | 28 ± 1 | 17 ± 1 | 1.6 | |

| pre-processed | Δpnp (CPLTRI) | 33 ± 8 | 19 ± 1 | 1.7 |

aβ-galactosidase units.

This low overall expression could result from the deletion of DNA sequences located downstream of the wild-type transcription start site. Removing these sequences might have made transcription initiation of the pre-processed mRNA inefficient. To check this hypothesis, the pnp promoter was exchanged for the lac promoter, as it is known that the transcription initiation rate of lacZ is independent of the sequences located just downstream of its initiation point (Xiong et al., 1991). Expression of the full-size processed fusion from a lac promoter instead of a pnp promoter (Figure 4B) was comparable to that from the pnp promoter. It was high in the absence of PNPase and autoregulated in its presence. However, expression of the pre-processed fusion (Figure 4D) was still low and insensitive to the presence of PNPase (Table I). The amounts of pnp–lacZ mRNA from the pre-processed and full-size processed transcripts were measured by northern blotting and confirmed the very low level of pre-processed mRNAs compared with the wild-type processed mRNA (data not shown). The fact that both the pnp and lacZ promoters give similar very low levels of expression and that the amount of pre-processed pnp–lacZ mRNA was very low suggests that the pre-processed mRNA is particularly unstable and subject to very rapid degradation. Moreover, this degradation is independent of PNPase and so, pre-processed mRNA is not sensitive to PNPase autocontrol. Taken together, these observations are consistent with the hypothesis that the duplex at the 5′ end of the pnp mRNA is necessary to stabilize pnp mRNA.

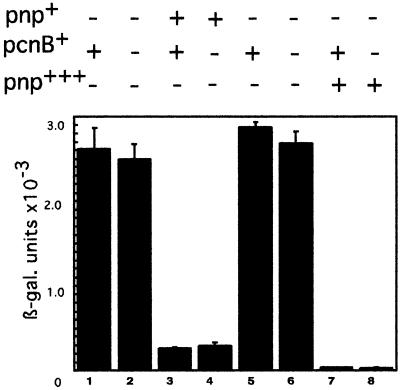

Effect of poly(A) polymerase on autocontrol

Another possible effector of PNPase autocontrol is poly(A) polymerase. The 3′ end overhang generated by RNase III on the upstream strand of the cleaved stem–loop might be a target of polyadenylation and, if so, might affect PNPase autoregulation. Expression of the fusion was tested in a strain lacking poly(A) polymerase (ΔpcnB) in the presence and absence of PNPase. In the absence of poly(A) polymerase, expression of the fusion, whether derepressed or repressed by PNPase, was identical in the wild-type and ΔpcnB strains (Figure 5, compare lane 1 with 2 and 3 with 4). Moreover, even in the presence of an excess of PNPase (from plasmid pBP111), the same strong repression was present in a wild-type and a ΔpcnB strain (Figure 5, compare lane 5 with 6 and 7 with 8). These observations show that polyadenylation, if present, has no effect on autocontrol.

Fig. 5. Expression at 30°C of the pnp–lacZ fusion carrying a wild-type pnp leader in the absence of poly(A) polymerase (ΔpcnB). Lane 1, CP5321F (Δpnp); lane 2, CPF5321PO (Δpnp, ΔpcnB); lane 3, GF5321 (pnp+); lane 4, GF5321PO(pnp+, ΔpcnB); lane 5 CP5321F–pBR322; lane 6, CPF5321PO–pBR322; lane 7, CP5321F–pBP111(pnp+); lane 8, CPF5321PO–pBP111.

PNPase degrades the RNase III processed stem in vitro

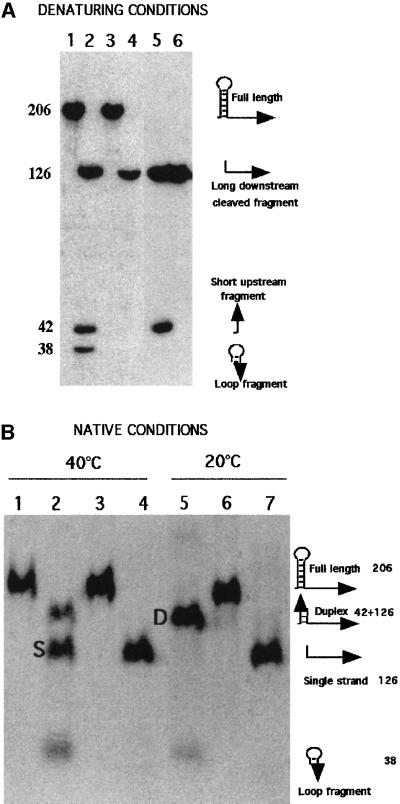

To demonstrate that PNPase is able to degrade one strand of the duplex created by the RNase III cleavage of the stem–loop, digestion of the duplex by PNPase was analysed in vitro. A transcript of 206 nt, corresponding to the pnp leader and extending to the 16th codon of the pnp mRNA, was synthesized in vitro in the presence of [α-32P]CTP. To prevent rapid degradation of this full-length transcript from its 3′ end by PNPase, the 3′ end was blocked by hybridizing with an oligodeoxyribonucleotide. The 3′-protected transcript was incubated at 20°C for 5 min in the presence and absence of PNPase. Analysis of the transcripts in a denaturing polyacrylamide gel showed in both cases only one band with the expected length (Figure 6A, lanes 1 and 3). This transcript was stable, even at 40°C, in the presence of PNPase, whereas it disappeared completely when the protecting oligonucleotide was omitted (data not shown). When purified RNase III was added, three smaller fragments were observed (Figure 6A, lane 2), corresponding to the double cut in the stem and producing a short upstream fragment (42 nt), a fragment derived from the loop (38 nt) and a long downstream fragment (126 nt; see illustrations in Figure 6). In the presence of both PNPase and RNase III, only one band was observed, corresponding to the 126 nt fragment (Figure 6A, lane 4), demonstrating that the two short fragments, whose 3′ ends were not protected, were efficiently degraded by PNPase.

Fig. 6. Effect of RNase III and/or PNPase on the pnp mRNA leader in vitro. The pnp mRNA leader was synthesized in vitro with [α-32P]CTP and its 3′ end protected with an oligodeoxynucleotide. After incubation in the presence of RNase III and/or PNPase, as described in Materials and methods, the samples were analysed in native and denaturing conditions. Positions of the bands were visualized by autoradiography. (A) Reactions were incubated at 20°C and analysed in denaturing conditions. Lane 1, full-length transcript without enzymes (control); lane 2, with RNase III; lane 3, with PNPase; lane 4, with RNase III and PNPase; lane 5, band D eluted from gel (B, lane 5) and corresponding to the duplex formed after RNase III processing (see text); lane 6, band S eluted from gel (B, lane 2) (see text). (B) Analysis in native conditions of samples incubated at 40°C (lanes 1–4) and 20°C (lanes 5–7). Lane 1, full-length transcript (control); lane 2, with RNase III; lane 3, with PNPase; lane 4, with RNase III and PNPase; lane 5, with RNase III; lane 6, with PNPase; lane 7, with PNPase and RNase III. Numbers correspond to the length of the fragments and the schematic diagrams in the margins illustrate the structure of the products. Arrowheads show the position of 3′ ends.

To prove that the duplex was still present in the incubation conditions and that PNPase was not acting on a dissociated duplex, the same incubations were carried out at 40 and 20°C and analysed on non-denaturing gels. In the presence of PNPase, the full-length transcript showed a single band only, migrating slowly at the same rate as the control, regardless of temperature (Figure 6B, lanes 1, 3 and 6). Thus, only one conformer was detected for the full-length transcript in native conditions. In the presence of RNase III, two bands were observed at 20°C (Figure 6B, lane 5): the faster migrating band corresponding to the loop fragment (38 nt) and the heavier band, migrating slightly faster than the full-length transcript, to the expected duplex. This was demonstrated by eluting this latter band (D) and analysing it on a denaturing gel (Figure 6A, lane 5). Two radioactive bands were detected, with lengths corresponding to the two expected strands of the duplex (126 and 42 nt). When the RNase III digestion was carried out at 40°C, three bands were observed on a non-denaturing gel (Figure 6B, lane 2). Two corresponded to the bands observed at 20°C, but the major band (S), with intermediate migration rate, corresponded to the downstream single-strand fragment (126 nt), as shown by elution and analysis on a denaturing gel (Figure 6A, lane 6). This indicates that the duplex was partially dissociated at 40°C in the incubation conditions, and that the fastest migrating band in Figure 6B lane 2 must be an unresolved mixture of 38 and 42 nt fragments. When PNPase and RNase III were added together, only one band was detected in a non-denaturing gel, regardless of temperature (Figure 6B, lanes 4 and 7). This band corresponds to the RNA fragment of 126 nt. Thus, the RNA duplex created by RNase III cleavage, which was present in the duplex form at least at 20°C, disappeared in the presence of PNPase because the upstream 42 nt fragment was completely degraded, leaving only the 126 nt fragment, which carried a 3′-protected end (Figure 6A, lane 4). These experiments show clearly that in vitro and at 20°C, PNPase is able to destroy the duplex created by RNase III to liberate a 5′ single-stranded pnp mRNA.

Discussion

A degradation barrier is present at the 5′ end of the pnp messenger

Many examples have been described where mRNAs are stabilized by the presence of a hairpin at their 5′ end (Bouvet and Belasco, 1992; Emory et al., 1992; Matsunaga et al., 1996b; Todd et al., 1998). This is probably the case for the pnp mRNA, which can form a stem–loop structure upstream of the Shine–Dalgarno sequence. The long half-life of the pnp mRNA, as well as the high expression of PNPase in the absence of RNase III processing (Portier et al., 1987), can be attributed to this structure acting as a degradation barrier. The removal of this degradation barrier appears to require two steps. In the first, RNase III cleaves at two sites in the stem–loop. The bottom half of the stem–loop produced by this cleavage remains double stranded both in vitro (Figure 6) and in vivo since it continues to act as a barrier to degradation in the absence of PNPase (Robert-LeMeur and Portier, 1994). The second step requires PNPase. In its presence, the pnp mRNA is rapidly degraded. It is proposed that the dangling 3′ end created by RNase III cleavage at the top of the mRNA duplex constitutes a target for PNPase, allowing it to progressively remove the upstream branch of the duplex (Figure 7). This releases a pnp mRNA with a single-stranded 5′ end, which is subject to rapid degradation by other, as yet unidentified, nucleases.

Fig. 7. Schematic diagram illustrating the proposed mechanism of destabilization of the pnp mRNA leader by PNPase.

The results obtained with the transcripts initiated at the RNase III processing site (position –81) and called ‘pre-processed’ are consistent with this interpretation. The pre-processed mRNA mimics the conditions achieved by RNase III cleavage and PNPase degradation of the upstream branch of the duplex. The very low mRNA level and the low expression of the pnp–lacZ fusion, even in the absence of PNPase, show that pnp mRNA initiated at position –81 is intrinsically unstable.

This situation is reminiscent of the mRNA instability triggered by the removal of a stem–loop, as observed in other mRNA leaders (Bouvet and Belasco, 1992; Emory et al., 1992; Hansen et al., 1994; Pepe et al., 1994; Jain and Belasco, 1995; Matsunaga et al., 1996a,b, 1997), but with one important difference: cleavage by RNase III is not sufficient to remove the protective duplex, which requires the subsequent action of PNPase. Thus, the role of PNPase is to bring the pnp mRNA into the same situation as these other mRNAs whose leaders are subject to endonucleolytic processing. In this model, RNase III processing of the pnp leader does not induce pnp mRNA stability per se (Portier et al., 1987), but has a dual action: to keep a degradation barrier at the 5′ end of the messenger and to create a 3′ end which forms an entry site for PNPase. In this way, the stability of pnp–lacZ mRNA (and hence its expression) is inversely correlated to the amount of active PNPase in the cell. This is the basis of the autocontrol.

Stem stability controls expression of pnp

Destabilization can occur in the absence of PNPase. The model proposes that the stability of the mRNA duplex per se affects expression of the pnp–lacZ fusion. Partial strand dissociation by ‘breathing’ should occur more actively at 42°C, favouring nicking and unspecific degradation and leading to a very low expression of pnp. The extent of breathing depends not only upon temperature, but also upon the effects of mutations on the stability of the duplex. This is illustrated by mutants AC1 and AC2, in which duplex stability is decreased. Conversely, when the stability of the duplex is increased, with mutations either increasing base pairing (AC1–2 or AC3–4) or preventing the cleavage of the stem–loop (AC4), expression of the fusion is higher than in the wild type at all temperatures. The high expression values, which are constant between 18 and 30°C, suggest that the degradation barrier remains present in this range of temperature but that it becomes less functional, presumably because of thermal dissociation at temperatures >30°C, accounting for the lower expression at higher temperatures. Some minor reverse transcriptase stop sites were seen at different positions with mutants AC3 and AC4 (Figure 2, lanes 2 and 3), and also with a rnc– strain (GF490) (Figure 2, lane 5). Although it is possible that they are artefacts linked to the presence of reverse transcriptase pause sites, they might also correspond to the presence of uncharacterized endonucleolytic cleavages, occurring at low frequency within the duplex, and which could promote degradation of the duplex, even in the absence of RNase III processing.

Specific effect of PNPase. No specific repression of the fusion by PNPase was observed in deregulated mutants (AC1–2, AC3–4, AC3 and AC4), as shown by a constant repression factor of ∼2, regardless of temperature (Figure 3C). The absence of RNase III processing of the pnp leader in mutants AC3 and AC4 means that no specific entry site is created for PNPase. In the two other mutants (AC1–2 and AC3–4), the absence of specific repression by PNPase, despite the processing in the pnp leaders, implies that the RNase III-processed stems are too stable to constitute targets for specific PNPase degradation, even at 42°C. It implies that the general decrease in expression in the presence of PNPase must correspond to a non-specific action of PNPase upon the 3′ ends formed by random nicking of the duplex.

For the wild type and mutants AC1 and AC2, degradation of the duplex is carried out specifically by PNPase. It is known that PNPase can degrade double-stranded RNAs, but this reaction is slow at low temperatures (Thang et al., 1967). Moreover, it has been shown that a 3′ single-stranded extension >6 nt long is necessary for rapid degradation (Spickler and Mackie, 2000), suggesting that a minimum length of single-stranded RNA is required to reach the catalytic centre of PNPase. When there is only a short 3′ extension (e.g. tRNA; Thang et al., 1967), PNPase should bind only when breathing generates a single-stranded 3′ end of sufficient length. Thus, one can imagine that the 2 nt 3′ overhang created by RNase III cleavage of the pnp mRNA leader is only a target for PNPase when spontaneous dissociation generates an overhang of sufficient length to be firmly bound by PNPase. Mutations like AC1 and AC2, which increase the fraying of the duplex, increase the degradation rate and make it more temperature dependent.

It is interesting to note that at 30°C in vivo, regulation by PNPase is at its most efficient, implying that this is the optimal temperature for PNPase to bind to the frayed 3′ end of the duplex. At higher temperatures, the intrinsic instability of the duplex decreases the repression efficiency, as demonstrated by the partial dissociation of the duplex at 40°C in vitro (Figure 6). At lower temperatures, degradation by PNPase is counteracted by the increased stability of the duplex, thus accounting for the decrease in repression efficiency at 18°C. This last effect can account for the cold inducibility of PNPase expression (Herendeen et al., 1979; Beran and Simons, 2001; Mathy et al., 2001).

A question arises regarding the role of RNase II in duplex degradation. This 3′ to 5′ exoribonuclease shares several properties with PNPase. However, despite an apparent similarity in their mode of degradation (Spickler and Mackie, 2000), it is known that PNPase attacks double-stranded RNAs more efficiently than RNase II (Mackie, 1989; McLaren et al., 1991; Pepe et al., 1994; Coburn and Mackie, 1996, 1998). Several RNA degradation intermediates, corresponding to stem–loops, which are RNase II resistant but more sensitive to PNPase, have been observed in vitro (Spickler and Mackie, 2000).

As polyadenylation has been shown to play an important role in chemical mRNA decay, a poly(A) extension could have been necessary to facilitate PNPase binding to the 3′ end 2 nt extension. Surprisingly, there was no effect of a pcnB mutation on expression of the pnp–lacZ fusion either in the presence or absence of PNPase, suggesting that PNPase binds directly to the processed stem. It is possible that a poly(A) tail is not necessary for PNPase binding because transient melting of the wild-type duplex allows the formation of a 3′ single-stranded end long enough for PNPase binding. It is also possible that the formation of a sufficiently long 3′ end requires the assistance of an RNA helicase.

The translational operator of PNPase is conserved in two other organisms

Interestingly, the low stability arrangement present at the top of the cleaved duplex (three A–U adjacent base pairs) contrasts with the nearby stretch of several alternating C–G base pairs. These more stable pairs could contribute to the formation of a persistent double-stranded structure in the lower part of the stem over a large range of temperature, impeding the activity of exonucleases like RNase II and creating the specific requirement for PNPase to remove the upstream strand of the duplex. Significantly, in two other organisms known to express a cold-inducible PNPase, Yersinia enterocolitica (Goverde et al., 1998) and Photorhabdus sp. (Clarke and Dowds, 1994), a long stem–loop leader is also present upstream of pnp. These stem–loops are processed at the same positions and are perfectly identical over 18 bp and bulges to that present in E.coli (shown within the dotted box in Figure 1). Since cold inducibility corresponds to a reversal of autocontrol (Beran and Simons, 2001; Mathy et al., 2001), it can be predicted that PNPase expression is autocontrolled by the same mechanism in both these organisms. The conserved sequence of the stem suggests that this duplex is an optimized structure for ‘catching’ PNPase.

In conclusion, PNPase does not appear to recognize a particular structure created by RNase III processing of pnp mRNA. Its specificity in autocontrol is conferred essentially by the transient concentration of accessible 3′ mRNA ends of the processed pnp leader. The availability of these 3′ ends is expected to be very dependent on temperature. A point that remains to be investigated concerns the rapid degradation of the processed pnp mRNA devoid of the protective stem at its 5′ end. Functional inactivation of the pnp mRNA could be the result of an endonucleolytic cut by RNase E 20 nt downstream of its initiation codon, as previously observed (Hajnsdorf et al., 1994a). In this context, the association of RNase E with PNPase in the degradosome could account for a synchronous degradation of the pnp mRNA. However, when expression of the pnp–lacZ fusion was measured in strains carrying mutation rne131 (Kido et al., 1996), which prevents assembly of the degradosome, there was no change in the temperature dependency of pnp expression in either pnp+ or pnp– context (A.-C.Jarrige, unpublished data). Whether RNase E per se or an unknown nuclease is involved in the subsequent degradation of the pnp mRNA remains to be determined.

Material and methods

Strains, plasmids and media

Strains, phages and plasmids used are listed in Table II. All strains are derivatives of IBPC5321 and carry the same pnp–lacZ translational fusions (see Figure 1) on a λ prophage (λGF1) as previously described (Robert-LeMeur and Portier, 1992). The phages harbour a cI857 thermosensitive mutation. To construct thermoresistant strains, which can grow at temperatures >30°C, double lysogens were made by co-infection of λGF1 with λ+. Lysogens of all phages were made in pnp+ (IBPC5321) and Δpnp (CP5321) strains. Monolysogen colonies were identified by PCR screening (Powell et al., 1994) or by β-galactosidase activity, which was measured as described (Miller, 1972). Cultures for RNA extraction and β-galactosidase measurements were grown in MOPS medium (Portier et al., 1987). Ampicillin was used at 100 µg/ml.

Table II. Genotype of the strains, phages and plasmids.

| Strains | Relevant characteristics | Origin or reference |

|---|---|---|

| IBPC5321 | argG6, argE3, his4, ΔlacX74, rpsL | Robert-LeMeur and Portier (1992) |

| CP5321 | argG6, argE3, his4, ΔlacX74, rpsL, Δpnp | C.Portier (unpublished data) |

| CP5321F | argG6, argE3, his4, ΔlacX74, rpsL, Δpnp (λGF1) | this work |

| CP5321PF | argG6, argE3, his4, ΔlacX74, rpsL, Δpnp (λPF1) | this work |

| CP5321POa | argG6, argE3, his4, ΔlacX74, rpsL, Δpnp, Δ(pcnB)1::Tn10-kan (λPF1) | this work |

| CPL5321 | argG6, argE3, his4, ΔlacX74, rpsL, Δpnp (λPF2) | this work |

| CPLTRI | argG6, argE3, his4, ΔlacX74, rpsL, Δpnp (λPF4) | this work |

| CPTRIPF | argG6, argE3, his4, ΔlacX74, rpsL, Δpnp (λPF3) | this work |

| GF490b | argG6, argE3, his4, ΔlacX74, rpsL, rnc105, nadB151::Tn10 | this work |

| GF5321 | argG6, argE3, his4, ΔlacX74, rpsL (λGF1) | Robert-LeMeur and Portier (1992) |

| PF5321 | argG6, argE3, his4, ΔlacX74, rpsL (λPF1) | this work |

| PFL5321 | argG6, argE3, his4, ΔlacX74, rpsL (λPF2) | this work |

| PFTRI | argG6, argE3, his4, ΔlacX74, rpsL (λPF3) | this work |

| PFLTRI | argG6, argE3, his4, ΔlacX74, rpsL (λPF4) | this work |

| Phages and plasmids | ||

| λGF1c | [rpsO, (pnp′-′lacZ)] cI857 | Robert-LeMeur and Portier (1992) |

| λPF1c | [(pnpP-pnp′-′lacZ)] cI857 | Robert-LeMeur and Portier (1992) |

| λPF2 | [(lacP-pnp′-′lacZ)] cI857 | this work |

| λPF3d | [(pnpP-pnpOΔ76-pnp′-′lacZ)] cI857 | this work |

| λPF4d | [(lacP-pnpOΔ76-pnp′-′lacZ)] cI857 | this work |

| M13G | pnp | this work |

| M13GF18 | [rpsO, (pnp′-′lacZ)] | Robert-LeMeur and Portier (1992) |

| pBP111 | [rpsO, pnp] Ampr (pBP322 derivative) | Portier et al. (1981) |

| pBSBHe | [(T7P-pnp′-′lacZ)] Ampr (Bluescribe M13– derivative) | this work |

aThe P1 phage lysate was made on strain SK7988 (O’Hara et al., 1995).

bThe rnc105 mutation (Kindler et al., 1973; Nashimoto and Uchida, 1985) was selected using the nearby nadB151::Tn10 mutation.

cThe pnp–lacZ fusion is expressed from the rpsO and pnp promoters (rpsOP and pnpP) in phage λGF1 and only from the pnp promoter in phage λPF1.

dThe pnp–lacZ fusion carries a 76 bp deletion between positions –157 and –82 in the pnp translational operator (pnpO).

eT7P, T7 promoter. The pnp–lacZ fusion is expressed from the T7 promoter (see Materials and methods).

Construction of a pnp–lacZ fusion expressed from the lac promoter

Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out by two different methods (Kunkel, 1985; Nakamaye and Eckstein, 1986). A BstBI site was introduced in phage M13GF18 (Robert-LeMeur and Portier, 1992), 11 nt after the transcription start site of pnp, giving phage M13GF181. A DNA fragment extending from the AvaII site in lacI to the transcription start point of lac was synthesized from wild-type chromosomal lac DNA by PCR using a primer carrying the pnp start site from –156 to the BstBI site. This DNA fragment was cloned in phage M13GF181 cut by the same restriction enzymes. An EcoRI site was created downstream of the AvaII site, after the 314th codon of lacI. The resulting mutant, called M13GF184, was cleaved by EcoRI and HindIII, and the DNA fragment carrying the pnp–lacZ fusion, now expressed from the lac promoter, transferred to a λ phage, giving λPF2.

Construction of a pnp–lacZ fusion expressed from a pre-processed pnp leader

With a pnp promoter. Phage M13G was isolated by cloning a ScaI DNA fragment of pBP111 carrying the pnp gene into phage M13mp8 cleaved by HincII. DNA corresponding to the pnp transcription start site (position –156) to the downstream RNase III cleavage site (position –81) was deleted using an oligonucleotide spanning the deletion. Sequences around the deletion were verified and the 5′ end of the pnp–lacZ transcripts was checked by primer extension. After cleavage by EcoRI and HpaI, at 182 nt downstream of the initition codon, the 5′ part of the pnp gene was ligated to M13mp8 cleaved by EcoRI and HincII, giving an in-frame translational pnp–lacZ fusion. This fusion was transferred to a λ phage, giving λPF3.

With a lac promoter. Using phage M13GF18 as a template, a PCR DNA fragment covering the lacI gene and extending to the transcription start point of the lac promoter was synthesized. The downstream primer carried, adjacent to the lac transcription start point, the pnp leader sequence from –81 to –41 (with a BglII site). A BglII site was introduced at the same position in the pnp leader of phage M13GF18 (54 nt upstream of the initiation codon of pnp), giving phage M13GF182. This M13 vector and the PCR fragment were both digested with BglII and AvaII, and ligated. An EcoRI site was then introduced in the lacI gene and the EcoRI–HindIII fragment carrying the pnp–lacZ fusion cloned into a λ phage, giving λPF4.

In vitro expression of the pnp mRNA leader and RNase assays

The BglII–HindIII fragment covering the pnp leader (from position –152, Figure 1) and the beginning of the pnp gene (position +183) was cloned into the Bluescribe M13– vector cleaved by EcoRI and HindIII. The resulting plasmid, called pBSBH, was used after linearization by MaeIII for in vitro transcription following the protocol described by Promega Biotec in the presence of [α-32P]CTP (3000 Ci/mmol; Amersham). The transcript synthesized was identical to the wild-type pnp leader, except for an additional stretch of 5 nt at the 5′ end. This transcript was annealed at 60°C for 2 min with an oligodeoxyribonucleotide complementary to the 3′ end, generating a 24 bp duplex. The transcript was purified from a native polyacrylamide gel, eluted and dried. About 10 pmol of RNA were incubated in 5 µl in the presence of 54 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0 containing 10 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dithiothreitol, 100 mM K acetate, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM K2HPO4 and 10% glycerol. Then 2.2 pmol of His-tagged pure E.coli RNase III, generously donated by Dr A.Nicholson, and/or 1 pmol of His-tagged pure E.coli PNPase (unpublished data) were added for 5 min. The samples were analysed on non-denaturing (6% polyacrylamide) or denaturing (8% polyacrylamide) gels. The position of the bands were detected by autoradiography.

RNA extraction and primer extension

Total RNA from aliquots of the cultures was extracted with hot phenol as described (Hajnsdorf et al., 1994b). Samples of total RNA (∼10 µg) were hybridized at 60°C with 20 pmol of an oligonucleotide previously 5′-labelled with [γ-32P]ATP (7000 Ci/mmol) and primer extension performed as described (Sanson and Uzan, 1993). Products were separated on 6% polyacrylamide gels containing 6 M urea and their lengths were determined by comparison with a DNA sequence of the corresponding region. All the mutations were checked by sequencing and sequences visualized by autoradiography.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Allen W.Nicholson for the gift of purified RNase III and Dr Jackie Plumbridge for careful reading and suggestions to improve the manuscript. This research was supported by the CNRS (UPR9073).

References

- Bardwell J.C.A., Régnier,P., Chen,S.-M., Nakamura,Y., Grunberg-Manago,M. and Court,D.L. (1989) Autoregulation of RNase III operon by mRNA processing. EMBO J., 8, 3401–3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran R. and Simons,R.W. (2001) Cold-temperature induction of Escherichia coli polynucleotide phosphorylase occurs by reversal of its autoregulation. Mol. Microbiol., 39, 112–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvet P. and Belasco,J.G. (1992) Control of RNase E-mediated RNA degradation by 5′ terminal base pairing in E.coli. Nature, 360, 488–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bycroft M., Hubbard,T.J., Proctor,M., Freund,S.M. and Murzin,A.G. (1997) The solution structure of the S1 RNA binding domain: a member of an ancient nucleic acid-binding fold. Cell, 88, 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke D.J. and Dowds,B.C.A. (1994) The gene coding for polynucleotide phosphorylase in Photorhabdus sp. strain K122 is induced at low temperature. J. Bacteriol., 176, 3775–3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn G.A. and Mackie,G.A. (1996) Differential sensitivities of portions of the mRNA for ribosomal protein S20 to 3′-exonucleases dependent on oligoadenylation and RNA secondary structure. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 15776–15781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn G.A. and Mackie,G.A. (1998) Reconstitution of the degradation of the mRNA for ribosomal protein S20 with purified enzymes. J. Mol. Biol., 279, 1061–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diwa A., Bricker,A.L., Jain,C. and Belasco,J.G. (2000) An evolutionarily conserved RNA stem loop functions as a sensor that directs feedback regulation of RNase E gene expression. Genes Dev., 14, 1249–1260. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emory S.A., Bouvet,P. and Belasco,J.G. (1992) A 5′ terminal stem loop structure can stabilize mRNA in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev., 6, 135–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Mena J., Das,A., Sanchez-Trujillo,A., Portier,C. and Montanez,C. (1999) A novel mutation in the KH domain of polynucleotide phosphorylase affects autoregulation and mRNA decay in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol., 33, 235–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godefroy T. (1970) Kinetics of polymerization and phosphorolysis reactions of E.coli polynucleotide phosphorylase. Eur. J. Biochem., 14, 222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goverde R.L.J., Huis in’t Veld,J., Kusters,J.G. and Mooi,F.R. (1998) The psychrotrophic bacterium Yersinia enterocolitica requires expression of pnp, the gene for polynucleotide phosphorylase, for growth at low temperature (5°C). Mol. Microbiol., 28, 555–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnsdorf E., Carpousis,A.J. and Régnier,P. (1994a) Nucleolytic inactivation and degradation of the RNase III processed pnp message encoding polynucleotide phosphorylase of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol., 239, 439–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnsdorf E., Steier,O., Coscoy,L., Teysset,L. and Régnier,P. (1994b) Roles of RNase E, RNase II and PNPase in the degradation of the rpsO transcripts of Escherichia coli: stabilizing function of RNase II and evidence for efficient degradation in an ams pnp rnb mutant. EMBO J., 13, 3368–3377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M.J., Chen,L.-H., Fejzo,M.L.S. and Belasco,J. (1994) The ompA 5′ untranslated region impedes a major pathway for mRNA degradation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol., 12, 707–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herendeen S.L., vanBogelen,R.A. and Neidhardt,F.C. (1979) Levels of major proteins of Escherichia coli during growth at different temperatures. J. Bacteriol., 139, 185–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kido M., Yamanaka,K., Mitani,T., Niki,H., Ogura,T. and Hiraga,S. (1996) RNase E polypeptides lacking a carboxy-terminal half suppress a mukB mutation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 178, 3917–3925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindler P., Keil,T.U. and Hofschneider,P.H. (1973) Isolation and characterization of a ribonuclease III deficient mutant of Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet., 126, 53–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel T.A. (1985) Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 82, 488–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain C. and Belasco,J.G. (1995) RNase E autoregulates its synthesis by controlling the degradation rate of its own mRNA in Escherichia coli: unusual sensitivity of the rne transcript to RNase E activity. Genes Dev., 9, 84–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie G.A. (1989) Stabilization of the 3′ one third of Escherichia coli ribosomal protein S20 mRNA in mutants lacking polynucleotide phosphorylase. J. Bacteriol., 171, 4112–4120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathy N., Jarrige,A.-C., Robert-Le Meur,M. and Portier,C. (2001) Increased expression of Escherichia coli polynucleotide phosphorylase at low temperatures is linked to a decrease in the efficiency of autocontrol. J. Bacteriol., 183, 3848–3854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga J., Dyer,M., Simons,E.L. and Simons,R.W. (1996a) Expression and regulation of the rnc and pdxJ operons of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol., 22, 977–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga J., Simons,E.L. and Simons,R. (1996b) RNase III autoregulation: structure and function of rncO, the posttranscriptional ‘operator’. RNA, 2, 1228–1240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga J., Simons,E.L. and Simons,R.W. (1997) Escherichia coli RNase III (rnc) autoregulation occurs independently of rnc gene translation. Mol. Microbiol., 26, 1125–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren R.S., Newbury,S.F., Dance,G.S.C., Causton,H.C. and Higgins,C.F. (1991) mRNA degradation by processive 3′-5′ exoribonucleases in vitro and the implications for prokaryotic mRNA decay in vivo. J. Mol. Biol., 221, 81–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J.H. (1972) Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Nakamaye K.L. and Eckstein,F. (1986) Inhibition of restriction endonuclease NciI cleavage by phosphorothioate groups and its application to oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res., 14, 9679–9698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashimoto H. and Uchida,H. (1985) DNA sequencing of the Escherichia coli ribonuclease III gene and its mutations. Mol. Gen. Genet., 201, 25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson A.W. (1996) Structure, reactivity and biology of double-stranded RNA. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol., 52, 1–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson A.W. (1999) Function, mechanism and regulation of bacterial ribonucleases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev., 23, 371–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara E.B., Chekanova,J.A., Ingle,C.A., Kushner,Z.R., Peters,E. and Kushner,S.R. (1995) Polyadenylylation helps regulate mRNA decay in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 1807–1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe C.M., Maslesa-Galic,S. and Simons,R.W. (1994) Decay of the IS10 antisense RNA by 3′ exonucleases: evidence that RNase II stabilizes RNA-OUT against PNPase attack. Mol. Microbiol., 13, 1133–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portier C., Migot,C. and Grunberg-Manago,M. (1981) Cloning of E.coli pnp gene from an episome. Mol. Gen. Genet., 183, 298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portier C., Dondon,L., Grunberg-Manago,M. and Régnier,P. (1987) The first step in the functional inactivation of the E.coli polynucleotide phosphorylase messenger is a ribonuclease III processing at the 5′ end. EMBO J., 6, 2165–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell B.S., Court,D.C., Nakamura,Y., Rivas,M.P. and Turnbough,C.L.,Jr (1994) Rapid confirmation of single copy λ prophage integration by PCR. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 5765–5766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Régnier P. and Portier,C. (1986) Initiation, attenuation and RNase III processing of transcripts from the Escherichia coli operon encoding ribosomal protein S15 and polynucleotide phosphorylase. J. Mol. Biol., 187, 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Régnier P., Grunberg-Manago,M. and Portier,C. (1987) Nucleotide sequence of the pnp gene of Escherichia coli encoding polynucleotide phosphorylase. Homology of the primary structure of the protein with the RNA-binding domain of ribosomal protein S1. J. Biol. Chem., 262, 63–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert-Le Meur M. and Portier,C. (1992) E.coli polynucleotide phosphorylase expression is autoregulated through an RNase III-dependent mechanism. EMBO J., 11, 2633–2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert-Le Meur M.R. and Portier,C. (1994) Polynucleotide phosphorylase of Escherichia coli induces the degradation of its RNase III processed messenger by preventing its translation. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 397–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanson B. and Uzan,M. (1993) Dual role of the sequence-specific bacteriophage T4 endoribonuclease RegB. mRNA inactivation and mRNA destabilization. J. Mol. Biol., 233, 429–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siomi H., Matunis,M.J., Michael,W.M. and Dreyfuss,G. (1993) The pre-mRNA binding K protein contains a novel evolutionarily conserved motif. Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 1193–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spickler C. and Mackie,G.A. (2000) Action of RNase II and polynucleotide phosphorylase against RNAs containing stem loops of defined structure. J. Bacteriol., 182, 2422–2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulewski M., Marchese-Ragona,S.P., Johnson,K.A. and Benkovic,S.J. (1989) Mechanism of polynucleotide phosphorylase. Biochemistry, 28, 5855–5864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symmons M.F., Jones,G.H. and Luisi,B.F. (2000) A duplicated fold is the structural basis for polynucleotide phosphorylase catalytic activity, processivity and regulation. Structure Fold Des., 8, 1215–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thang M.-N., Guschlbauer,W., Zachau,H.G. and Grunberg-Manago,M. (1967) Degradation of transfer ribonucleic acid by polynucleotide phosphorylase. J. Mol. Biol. 26, 403–421. [Google Scholar]

- Todd E.A., Yu,J. and Belasco,J.G. (1998) mRNA stabilisation by the ompA 5′ untranslated region: two protective elements hinder distinct pathways for mRNA degradation. RNA, 4, 319–330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X., de la Cruz,N. and Reznikoff,W.S. (1991) Downstream deletion analysis of the lac promoter. J. Bacteriol., 173, 4570–4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K. and Nicholson,A.W. (1997) Regulation of ribonuclease III processing by double-helical sequence antideterminants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 13437–13441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M. (1989) On finding all suboptimal foldings of an RNA molecule. Science, 244, 48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]