Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterised by cognitive impairment, memory loss, and decline in thinking and learning skills. The exact pathophysiology of the disease is still unknown; however, theories such as tau hyperphosphorylation, amyloid-β (Aβ) aggregation, and cholinergic dysfunction explain its pathogenesis. A few available drugs provide only symptomatic relief, while recently approved monoclonal antibody-based drugs target aggregated amyloid beta clearance. Extensive research is ongoing for drug development targeting various pathways, where one of the targets is glycogen synthase kinase (GSK-3β). GSK-3β plays diverse roles in physiological functions, and its dysregulation may lead to pathological conditions such as Alzheimer's disease (AD). GSK-3β comprises serine and threonine residues, is responsible for phosphorylation of the tau protein, and activates the amyloid precursor protein (APP) to synthesise Aβ. Consequently, the abnormal functioning of GSK-3β leads to hyperphosphorylation of the tau protein, and the formation of Aβ plaques eventually leads to neurofibrillary tangles. To develop GSK-3β inhibitors, one must know the requirements of crucial structural features in drug candidates to act at the active site for interaction. This review focuses on the latest pool of GSK-3β inhibitors and their design strategy, structure–activity relationship (SAR), molecular docking, and permeability across the brain layers. This broad review collection may benefit readers by providing the structural requirements to develop new GSK-3β inhibitors for treating AD.

Structure–activity relationships of GSK-3β inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease.

1. Introduction

Glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) is a protein kinase that takes part in glycogen metabolism and is involved in several signalling pathways, including Wnt,1 Hedgehog,2 cAMP and NF-AT.3 These diverse involvements may be responsible for its distinct cellular functions such as metabolism, cell motility, apoptosis, cell differentiation, proliferation, embryonic development,4 and mitochondrial metabolism.5 This inimitable attribute makes GSK-3β an essential target for therapeutic intervention in various diseases,6 including mood disorders, diabetes, cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease (AD).7 Alzheimer's disease is characterised by dementia, which is the foremost inducer of AD that affects the geriatric population. The traits of this disease are the progressive loss of memory and intellectual weakening, and other symptoms include disturbance in spatial orientation, language delinquency, and muddled and labile mood swings.8 Its neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) include antagonistic behaviour, nervousness, sensorimotor deficit and insomnia.9 At the cellular level, it is characterised by the formation of hyperphosphorylated tau protein, insoluble β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFT).10,11

According to WHO records, the number of Alzheimer's cases globally is snowballing every year. Dementia is the seventh leading cause of death, and females are mostly affected compared to the male population. Nearly 10 million new cases arise every year. According to the 2019 metrics, globally, the treatment for dementia costs 1.3 trillion US dollars (https://www.who.int/). To date, there is no effective drug against Alzheimer's, which might be due to its intricate and baffling pathophysiology; however, marketed drugs such as donepezil (AChE inhibitor) and memantine (NMDA inhibitor) are some of the medications used in the management of Alzheimer's, which give symptomatic relief.12 GSK-3β inhibitors have been reported as therapeutic agents, with ongoing clinical trials and animal studies in different stages. Tideglusib, a non-ATP inhibitor of GSK-3β, failed phase II clinical studies (Table 1) due to safety and efficacy concerns.13–15 Rigorous investigations have been ongoing to find effective drugs for many years, with many drugs under clinical trials at different stages.16 The US-FDA approved Aduhelm (aducanumab) in 2021 to treat patients with Alzheimer's, and Kisunla (donanemab-azbt) injection was approved in 2024, which binds to the β-amyloid protein and is used for mild cases only (https://www.fda.gov/).

Table 1. GSK-3β binding site and inhibitors along with clinical status.

| Binding site | Inhibitors | Mechanism of action | Clinical and pre-clinical status |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATP binding site |

|

Hydrogen bonding with hinge residues Asp133 and Val135 anchors the ligand in the ATP pocket, strengthening GSK-3β inhibition | Preclinical studies |

| Substrate binding site |

|

It mimics the natural substrate peptide and prevents the prime phosphorylation required for GSK-3β activation, thereby exerting an inhibitory effect | Preclinical24 |

| Allosteric site or non-ATP binding region |

|

Ligand binding induces conformational changes in GSK-3β that obstruct its ATP-binding pocket, thereby preventing ATP access and effectively inhibiting its kinase activity | Preclinical studies. Tideglusib was withdrawn from clinical trials due to safety and efficacy issues |

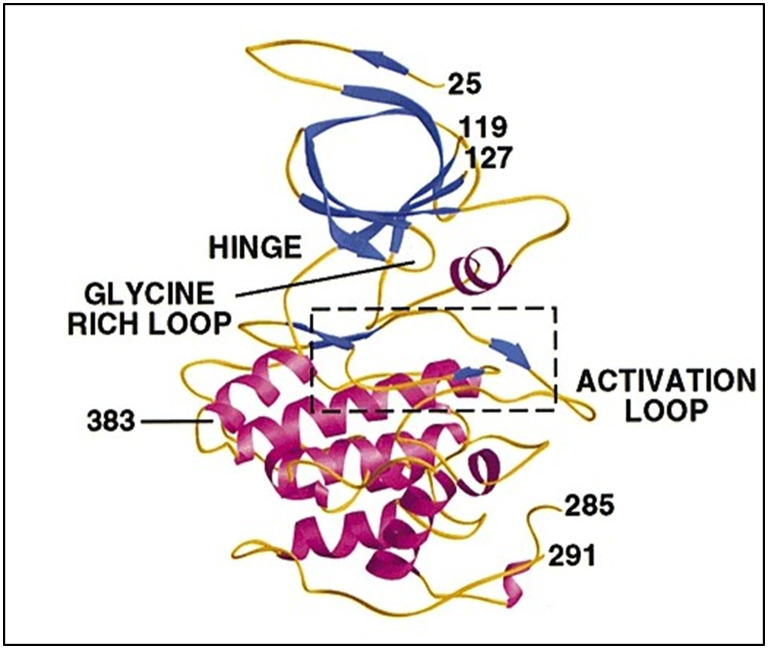

1.1. Crystal structure of GSK-3β

As a member of the kinase family, GSK-3β is well-preserved with serine/threonine kinases, which are ubiquitously expressed and responsible for protein phosphorylation, glycogen metabolism, and other cellular functions. In mammals, it exists in two isoforms, i.e. GSK-3α (51 kDa) form and GSK-3β (47 kDa). GSK-3α and GSK-3β have 96% similarity with kinase and 36% identity in their N-terminal region; the main difference is that GSK-3α is enriched with glycine residues at its N-terminal. The GSK-3β form exists in two variants, the major one is GSK-3β1, which is present in most organs, and GSK-3β2 is the minor one and comprises 13 amino acid residues at the kinase domain.17,18 The crystal structure of GSK-3β (Fig. 1) reveals a larger C-terminal region consisting of spiral α helices (residues 139–343). Its N-terminal is comprised of β-strands (residues 25–138), stabilised by internal hydrogen bonds. The region that ties these two terminals is called the hinge region, which consists of Val135 and Lys85 residues and is decisive for inhibition. The 39 residues in the C-terminal form a small domain outside the kinase domain against the α helices. 2–6 antiparallel β-strands out of seven form a β-barrel, leading to a short helix between strands 4 and 5. This helix is conserved in all kinases and exerts various catalytic functions. The residues such as Arg96, Glu97 and Lys85 are key in catalysis. Arg96 is involved in the alignment of the two domains, Glu97 is positioned in the active site, and Lys85 forms a salt bridge. The space between the C-terminal and N-terminal encircles the ATP-binding site. The activation loop is the elastic region at the substrate binding groove. It has two conserved regions, i.e., DFG (aspartate-phenylalanine-glycine), which is involved in enzyme activation and HRD (histidine-arginine-aspartate), which is involved in substrate binding.19 These structural features are crucial in hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic molecule interactions.

Fig. 1. Crystal structure of GSK-3β (reprinted with permission from ref. 19 Nature Structural Biology, Copyright 2001).

1.2. Binding sites of GSK-3β

GSK-3β has several binding sites and various interaction regions with crucial functions. GSK-3β has four important binding sites, including 1) ATP-binding region, 2) substrate binding region, 3) allosteric binding region, and 4) axin/FRAT tide binding site.20 Palomo et al.72 unveiled that GSK-3β has seven pockets located in its binding sites, which make up the active sites for effective binding.

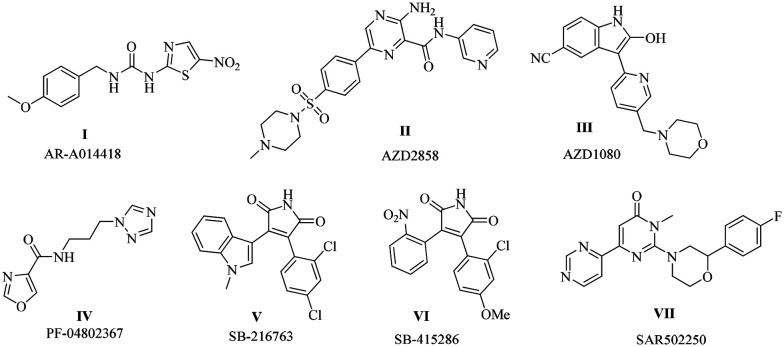

ATP-binding site

The ATP-binding site is well preserved in kinases with an ATP-binding cavity. Staurosporine, a representative ATP-binding inhibitor, forms a hydrogen bond at the hinge region through Vall135 and Asp133 residues. However, targeting this binding site has off-target effects due to its non-specificity. Drugs such as staurosporine, AR-A014418, AZD2858, PF-04802367, SB-216763 and SB-415286 are examples of ATP-binding inhibitors in preclinical studies (Table 1).

Substrate binding site

GSK-3β is a unique kinase among the kinases; it needs prephosphorylation by its substrate for activation. The substrate binding site recognises the prime phosphorylated site and offers specific binding between the binding site and the ligand/peptide. However, weak binding interactions with the enzyme and problems associated during biological evaluation arise as limitations; thus, chemical modification may overcome these limitations. Targeting the prephosphorylation process might be a beneficial strategy. For example, peptides such as L803mts and L807mts inhibitors are potent substrate-binding inhibitors. They act as substrates for GSK-3β and inhibit its phosphorylation. Other peptides such as Frat (FRATide-39 residues) and axin (Axin GID-25 residues) have been reported21,22 (Table 1).

Allosteric binding site

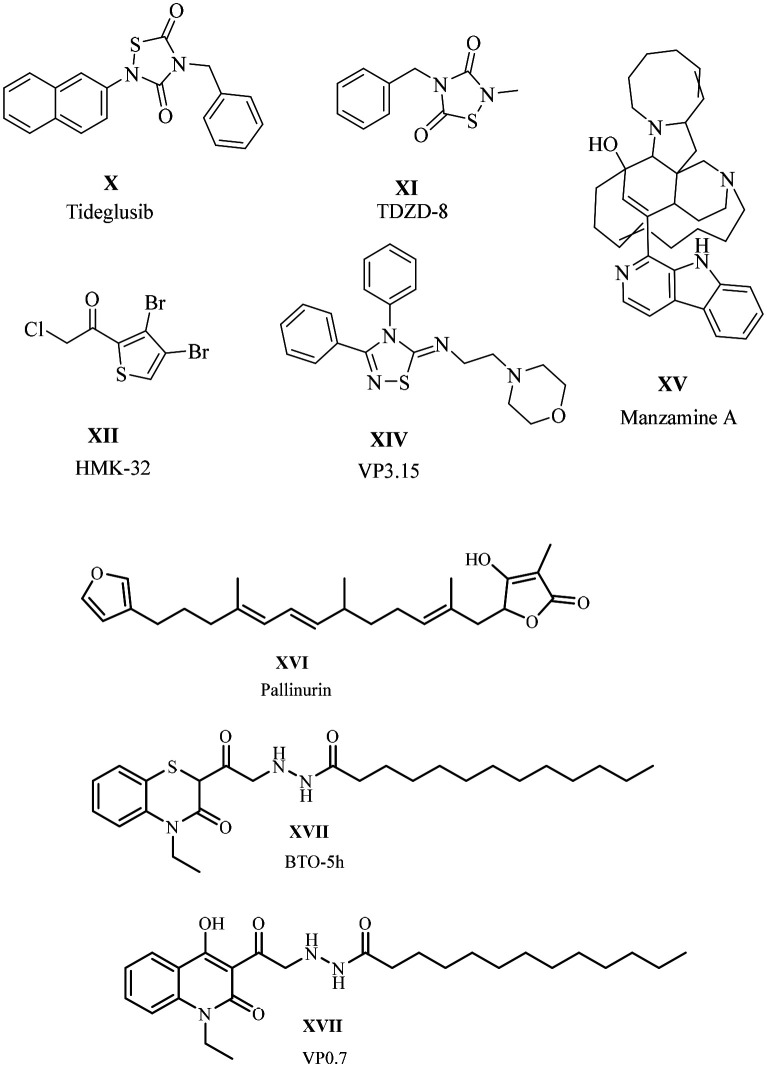

An allosteric site is a non-ATP-binding site, causing conformational changes in the GSK-3β protein that block the ATP-binding site in its active site. Targeting allosteric binding sites may offer safety and efficacy. However, some challenges remain, such as weaker binding affinities and unpredictable conformational changes. Drugs such as tideglusib and halomethyl ketones are irreversible inhibitors by forming a covalent bond, whereas TDZD is reversible. 5-Imino-1,2,4-triazoles and benzothiazines are allosteric binding inhibitors. Marine-based natural products like Palinurin Manzamazine A also exhibit allosteric inhibition (Table 1).23

1.3. Role of GSK-3β in AD progression

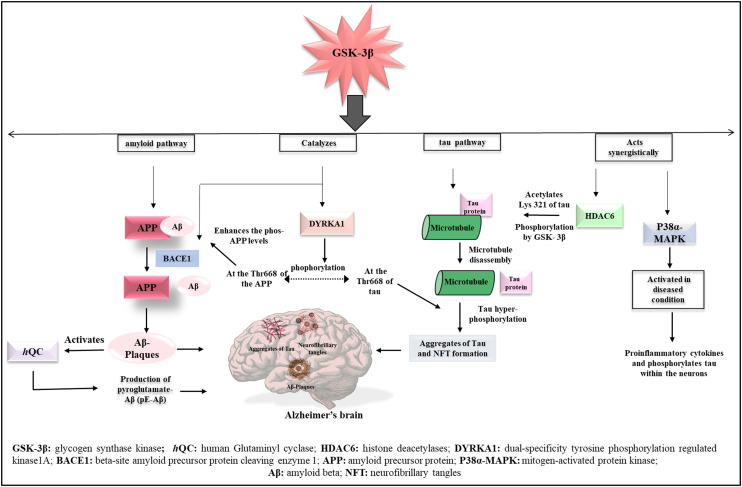

Several hypotheses support the role of GSK-3β in Alzheimer's disease (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Involvement of GSK-3β with various other targets in the pathogenesis of AD.

1.3.1. GSK-3β with tau protein

GSK-3β regulates phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of the tau protein and facilitates tubulin binding with microtubules for various cellular processes. Dysregulation or overactivation of GSK-3β can lead to tau hyperphosphorylation and a decrease in tubulin binding to microtubules, resulting in disruption. This leads to various forms of hyperphosphorylated tau protein, including dimers, trimers, small oligomers, filaments, and neurofibrillary tangles, which cause conflicts in cellular events.25,26 To date, GSK-3β has been proven to phosphorylate 15 sites on tau including Ser46, Thr50, Thr175, Thr181, Ser199, Ser202, Thr205, Thr212, Thr217, Thr231, Ser235, Ser396, Ser400, Ser404, and Ser413. Among all the sites, only Ser400 and Ser413 are non-proline sites.27

1.3.2. GSK-3β with amyloid protein

GSK-3β plays a key role in producing and metabolising Aβ peptides by interacting with the amyloid precursor protein (APP) and BACE1, which support neuronal activities. An imbalance between Aβ peptide production and its clearance from the brain leads to the formation of Aβ plaques due to aggregation. Some scientific studies also highlight mutations in the APP gene, and preclinical studies have revealed that disturbances in Aβ metabolism may contribute to the disease.28–30 This leads to pathological conditions such as Aβ plaques, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis.31 The involvement of various targets can lead to the formation of tau protein aggregates and Aβ plaques, which may form insoluble neurofibrillary tangles (NFT).

1.4. Other targets

GSK-3β and the epigenetic target, histone deacetylases (HDAC), work synergistically to increase the expression of tau protein. HDAC6 deacetylates tau protein at specific lysine residues. The deacetylated tau protein may expose phosphorylated sites, making it more susceptible to phosphorylation by GSK-3β, which can lead to hyperphosphorylated tau protein.32,33 GSK-3β may have an indirect relationship with human glutaminyl cyclase (hQC). Aβ plaques are composed of various species of Aβ peptides, including different variants of Aβ peptides such as pyroglutamate-Aβ, which are formed by human glutaminyl cyclase (hQC). Human glutaminyl cyclase (hQC) is a zinc-dependent enzyme that cyclizes N-terminal glutamate and glutamine residues in peptides such as Aβ, leading to pyroglutamate-Aβ types.34,35 DYRK1A (dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A) kinase catalyses GSK-3β signalling and is involved in the amyloid and tau pathways.36 GSK-3β catalyses the cleavage of APP (amyloid precursor protein) by BACE1 (beta-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1), releasing free Aβ fragments.37,38 GSK-3β and p38α MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) share similarities in their kinase regions. During Alzheimer's conditions, p38α MAPK get activated and releases pro-inflammatory cytokines. These cytokines cause hyperphosphorylation of tau protein, leading to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) (Fig. 2).39,40 Neflamapimod, a P38α MAPK inhibitor for Alzheimer's disease, completed phase II clinical trials in 2019. Prins et al. (2021)41,42 conducted a double-masked, placebo-controlled trial on neflamapimod, which found no significant improvement in memory.

The comprehensive study of GSK-3β reveals its crucial role in activating various cellular targets, highlighting its significant influence on disease development. Therefore, targeting GSK-3β might be an encouraging strategy in the development of drugs for AD. Thus far, a few review articles have been published that cover various topics related to GSK-3β.43–49 Xu et al. (2019)50 presented the structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies for synthetic molecules that inhibit GSK-3β.

After a thorough review of the literature, it has been identified that there is a need for detailed SAR studies of newly developed molecules (2019–2025) and computational studies. This review includes the ability to permeate the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Additionally, it discusses the structure–activity relationship (SAR) of PROTACs as a novel approach against GSK-3β. This review may assist researchers in designing molecules using a structure-based, computational approach, potentially leading to the discovery of new drugs for treating Alzheimer's disease.

2. Structure–activity relationship studies (SAR)

2.1. SAR of N-(pyridin-2-yl)cyclopropanecarboxamide derivatives and its analogues

The N-(pyridin-2-yl)cyclopropanecarboxamide moiety has been widely used to develop GSK-3β inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease. This moiety is rich in hydrogen bond acceptors and donors, facilitating significant hydrogen bond interactions in the hinge region. Thus, various molecules have been designed and synthesised by combining or modifying N-(pyridin-2-yl)cyclopropanecarboxamide.

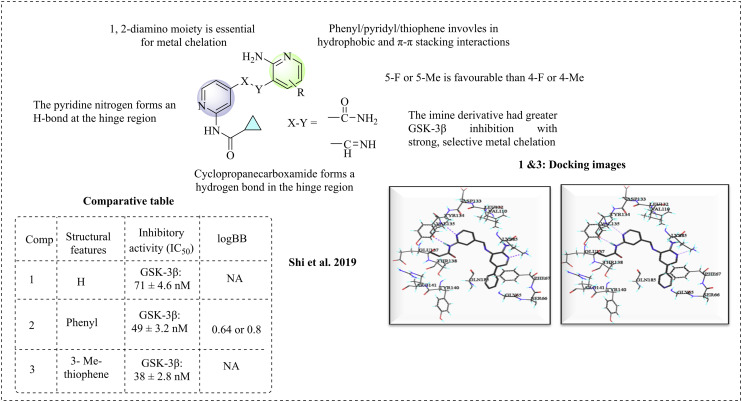

2.1.1. N-(Pyridin-2-yl)cyclopropanecarboxamide and 2-pyridine

N-(Pyridin-2-yl)cyclopropanecarboxamide, which is linked to a pyrrolopyridinone derivative, has demonstrated effectiveness against GSK-3β.66 Shi et al. (2019) introduced novel GSK-3β inhibitors by using a multifunctional strategy to design molecules with the N-(pyridin-2-yl)cyclopropanecarboxamide framework, where the pyrrolopyridinone core is substituted with a 2-pyridine ring.51 These components are interconnected by amide, imine, and amine bridges, with the possibility of aromatic or amino acid substitutions to enhance metal chelation. The designed molecules were synthesised, and then evaluated for their effectiveness against GSK-3β. These studies showed that the amide derivatives achieved 75% inhibition at a concentration of 1 μM and exhibited moderate potency, with an IC50 value ranging from 120 to 650 nM. In comparison, staurosporine, an ATP-competitive kinase inhibitor, had an IC50 value of 24 ± 3.0 nM. Inadequate chelation may be due to the presence of a carbonyl group, an electron-withdrawing moiety that diminishes the electron cloud on nitrogen, thereby impeding metal chelation. The evaluation of imine derivatives showed improved potency against GSK-3β. Compounds 1, 2, and 3 exhibited significant activity, increasing their effectiveness by 3- to 9-times. Additionally, compound 2 has the potential to form a complex with metals and demonstrates excellent chelation properties towards Cu2+. The structure–activity relationship of the molecules indicates that the imine derivatives are more active than amides. In the imine derivatives, substitutions such as phenyl and pyridyl rings form hydrogen bonds at the binding site, which may enhance their inhibitory effects. Substituents such as fluorine and methyl at position 5 of the pyridyl ring improved the activity compared to substitutions at position 4. A molecular docking study was performed with the GSK-3β protein, demonstrating that the synthesised compounds exhibited significant interactions. Blood–brain barrier penetration was assessed using logBB values, which should be ≥ −1. Compound 2 adheres to Lipinski's rule, showing a logBB of −0.64 according to the ACD/Lab software and −0.8 by Clark's method. Both studies suggest that compound 2 has active penetration capabilities, making it a promising candidate for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Structure–activity relationship for N-(pyridin-2-yl)cyclopropanecarboxamide and 2-pyridine (docking images reprinted with permission from ref. 51, Elsevier, Copyright 2019).

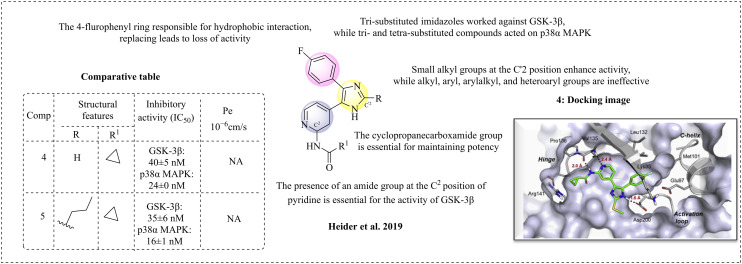

2.1.2. N-(Pyridin-2-yl)cyclopropanecarboxamide and imidazole derivatives

GSK-3β and p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38α MAPK) are interconnected, sharing 42% similarity. Dysregulation of GSK-3β can activate p38α MAPK, leading to the production of proinflammatory cytokines. These proinflammatory cytokines contribute to various neuronal defects, including neuroinflammation in the brain and spinal cord.52 In their investigations, Heider et al. (2019) reported dual inhibitors of GSK-3β and p38α MAPK for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease.53 This team developed a lead molecule featuring a pyridinylimidazole framework, which is significant in medicinal chemistry due to its ability to inhibit multiple kinases, particularly p38α MAPK and GSK-3β.54–56 The synthesised molecules were evaluated for their inhibitory activities against p38α MAPK and GSK-3β. The standard drugs were SB203580 with an IC50 of 41 nM for p38α MAPK activity and SB216763 with an IC50 of 89 nM for GSK-3β. The structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies of pyridinylimidazoles reveal that the amide group at the C2 position of the pyridine ring is crucial for GSK-3β activity. Different substitutions at the R1 position of the amide bond can influence the dual activity against GSK-3β and p38α MAPK. Specifically, a methoxy group on the phenyl moiety at the R1 position reduces the GSK-3β activity, while effectively inhibiting p38α MAPK. In another example, substituting a phenyl group with a trifluoromethyl group led to the inhibition of GSK-3β, while demonstrating potent activity against p38α MAPK. The electronic properties of the phenyl group are crucial for GSK-3β inhibition, given that the phenyl group engages in cation–π interactions at the binding site. Shortening the alkyl chain between the amide and the phenyl group decreases the GSK-3β activity and enhances the inhibition of p38α MAPK. Conversely, introducing bulkier groups, such as cyclobutyl and cyclopentyl, results in a loss of GSK-3β activity. Based on this data and analysis of the crystal structures of both targets, it is concluded that the hinge region of GSK-3β serves as the primary interaction site and is densely populated with various amino acid residues. The p38α MAPK protein contains Met109, Gly110, Ala111, and Asp112 residues. An important characteristic of p38α MAPK is the flipping of glycine upon ligand binding. In contrast, GSK-3β lacks this feature but is conserved with larger residues such as Tyr134, which helps stabilise its hinge region. With this broad study, the team decided to synthesise smaller moieties, which may give dual inhibition. For example, they synthesised a smaller N-acetyl derivative, which has shown balanced dual inhibition. Other smaller derivatives, such as cycloalkane and cyclocarboxamide derivatives, were synthesised; cyclopropane carboxamide derivatives were the most potent, while cyclobutyl and cyclopentyl were least potent. These results indicate that the size of the ring may influence the activity. However, substituting the cyclopropyl ring with phenyl enhances the GSK-3β activity and slightly improves p38α MAKP inhibition. The trisubstituted imidazole exhibits stronger affinity than the tetrasubstituted imidazole for GSK-3β. However, both the tri- and tetra-substituted analogues are active against p38α. Molecular docking studies were performed for both targets, p38α MAKP and GSK-3β, to identify the binding pattern using the induced fit docking method instead of soft docking to avoid errors on compound 4 against GSK-3β. Most of the synthesised compounds are active; among them, compound 5 displayed the highest activity, with inhibition in the nanomolar range, good plasma drug concentration, and high CNS permeation (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Structure–activity relationship of N-(pyridin-2-yl)derivatives (docking image reprinted with permission from ref. 53, Elsevier, Copyright 2019).

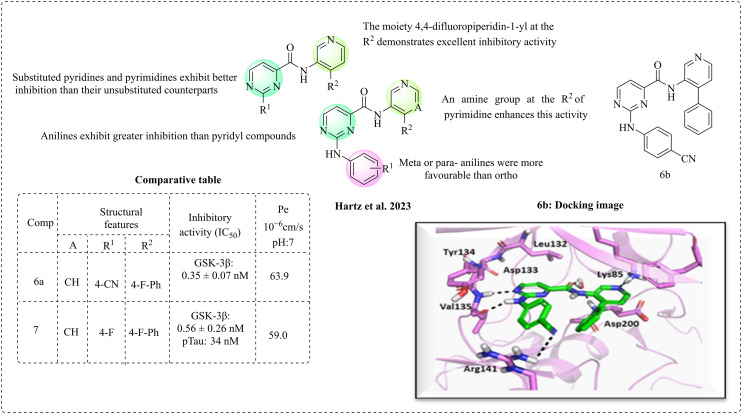

2.1.3. 2-(Anilino)pyrimidine-4-carboxamides and pyridine

Hartz et al. (2023) disclosed 2-(anilino)pyrimidine-4-carboxamide as an orally active GSK-3β inhibitor, inspired by the design patterns of pyrrolopyridinone and isonicotinamide-based inhibitors.57 The crystallographic studies of isonicotinamide support its binding pattern; however, animal studies indicate that its high metabolic clearance is a limitation, which may be due to the hydrolysis of the cyclopropyl carboxamide moiety. The energy profile studies and biological evaluation of anilinopyridine and anilinopyrimidine derivatives revealed that the anilinopyrimidine ring is more favourable for the hinge region due to the presence of an amide NH residing near the lone pair of the N3 nitrogen of the pyrimidine, which results in a favourable interaction. Substituted pyridines and pyrimidines had greater inhibition than the unsubstituted ones. Substitutions at positions 2 and 4 of pyrimidine were optimised to get highly potent derivatives. The cyclopropylcarboxamide group was substituted with phenyl or pyridyl, incorporating various substitutions such as methyl, methoxy, CF3, F, Cl, and CN, which exhibited different inhibition activities. Methyl and methoxy substitutions at the para position had good inhibition in the nanomolar range. The chloro and fluoro substitutions at the para or meta position of aniline exhibited good to moderate inhibition; however, ortho substitutions are unfavourable. 4,4-Difluoropiperidin-1-yl has been identified as a potent substituent for activity, which at the pyridinyl ring exhibited excellent inhibition. When 4,4-difluoropiperidin-1-yl is combined with an amine at the pyrimidine, it enhances the level of inhibition. The amine–aniline group on the pyrimidine ring may enhance the activity, which likely due to hydrogen and hydrophobic interactions at the binding site (Fig. 5). Crystallographic studies also evidenced that the synthesised molecules had the required interactions (compound 6b). The brain penetration studies were carried out using the parallel artificial membrane permeability assay (PAMPA); all the compounds can cross the BBB, and compounds 6a and 7 have good to high permeability. A tau phosphorylation inhibition assay was performed, and compounds 6a and 7 showed 33% and 37% reduction in pTau396, which was administered orally as a suspension, and exhibited effective GSK-3β inhibition in the nanomolar range. Also, the plasma concentration was observed to be 410 ± 150 nM and 180 ± 50 nM and brain concentration 370 ± 80 nM and 180 ± 70 nM for compound 6a and 7, respectively, with satisfactory bioavailability.

Fig. 5. Structure–activity relationship of N-(pyridin-2-yl)derivatives (docking image reprinted with permission from ref. 57, the American Chemical Society, Copyright 2023).

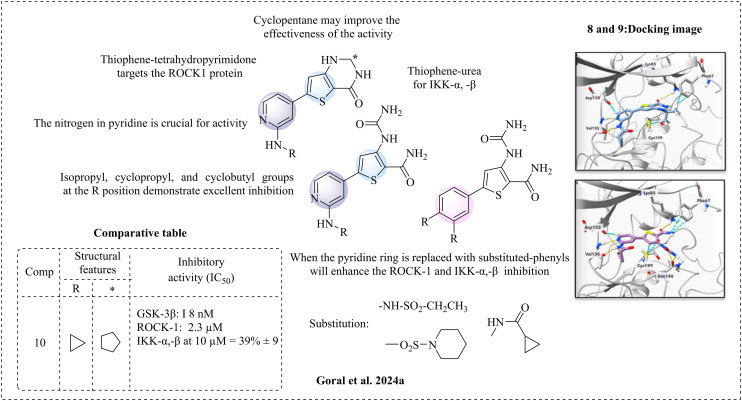

2.1.4. N-(Pyridin-2-yl)cyclopropanecarboxamide-thiophene with tetrahydropyrimidone/urea

Góral et al. (2024a)58 reported a novel inhibitor against GSK-3β, ROCK-1 (Rho-associated coiled-coil protein kinase 1)59–62 and IKK-β (interleukin-1β).63,64 The ROCK-1 and IKK-β pathways are novel factors in Aβ production, ultimately forming Aβ plaques in Alzheimer's disease. After reviewing the targets and essential structural features required for inhibition, Goral et al. designed a series of molecules. These molecules are comprised of a six-membered heteroaromatic ring, specifically an N-(pyridin-2-yl) ring, combined with cyclopropanecarboxamide, which are active against GSK-3β. Additionally, they developed a series that includes a thiophene ring fused with tetrahydropyrimidone, potentially targeting IKK-β. Another series features thiophene with urea functionality, which may target ROCK-1. The SAR analysis indicated that satisfactory inhibition occurs when cyclocarboxamide is substituted with alkyl, cycloalkyl, phenyl, or sulfonamide. The alkyl groups, such as isopropyl, cyclopropyl, and cyclobutyl, showed potent inhibition. In contrast, the smaller methyl and larger cyclohexyl and phenyl groups exhibited the least inhibition in both series. Groups that are too small or too large may not favour inhibition. An amide bond in both series is essential; activity loss has been observed when substituted with sulfonamides. In the case of IKK-β and ROCK-1, substituting the pyridine moiety with various sulfonamides and cyclopropanecarboxamides enhances their inhibition. Molecular docking studies were performed to support the inhibitory results (compounds 8 and 9). Inhibitory studies targeting the IKK-β and ROCK-1 kinases revealed enhanced activity when a phenyl ring, in place of the pyridine, was used against IKK-β. The pyridine structure acts as a hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) and is essential for inhibiting GSK-3β. Replacing it with a phenyl group could adversely affect its activity. However, substituting the phenyl group with a fluorine atom might restore the critical hydrogen bonding interaction with Val 135 (Fig. 6). Compound 10 demonstrated the highest potency compared to the reference drug staurosporine. Additionally, in vitro ADME properties showed satisfactory results, including solubility, thermodynamic stability, and chemical and metabolic stability.

Fig. 6. Structure–activity relationship of N-(pyridin-2-yl) derivatives (docking images reprinted with permission from ref. 58, Springer-Verlag, Copyright 2024).

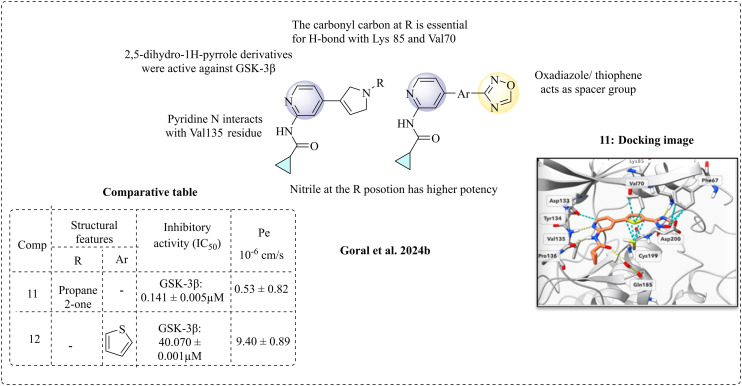

2.1.5. N-(Pyridin-2-yl)cyclopropanecarboxamide-oxadiazole/thiophene

Goral et al. (2024b) developed a new class of GSK-3β inhibitors with anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties.65 The designed inhibitors feature an N-(pyridin-2-yl)cyclopropanecarboxamide moiety, integrated with HBA and HBD, inspired by the results from the computational model.66 GSK-3β inhibitory studies were performed, and compounds 11 and 12 showed positive results against GSK-3β compared with the standard drug staurosporine. According to the SAR studies, apart from the N-(pyridin-2-yl)cyclopropanecarboxamide ring, the oxadiazole and thiophene rings are essential for inhibition. Reduced activity was observed when the oxadiazole moiety was replaced with a phenyl ring. Additionally, substituting thiophene with a phenyl or pyridyl moiety at the para position resulted in decreased inhibition. When a phenyl or pyridyl group was present at the meta position, there was a loss of interactions with the lysine residues at the catalytic site. These findings suggest that 5-membered heterocycles are likely crucial for GSK-3β inhibition. The nitrile-substituted derivatives also exhibited similar inhibition properties. The 2,5-dihydro-1H-pyrrole analogues showed interactions in the hinge region, resulting in potent activity. A carbonyl group at the R position of pyrrole is essential; its removal or replacement could lead to the loss of activity, given that the carbonyl group is necessary for hydrogen bonding with the Lys85 and Val70 residues. The crystallographic and molecular docking studies provided positive insights that compound 11 has effective binding and is responsible for inhibition. Further, studies also revealed that residues such as Asp133, Tyr134, Val135, and Pro136 are involved in hydrogen bonding at the hinge region. Residues such as Cys199, Val70, and Phe67 form hydrophobic interactions. Lys85 and Glu97 are involved in an extra H-bond. PAMPA was performed to study the permeability of the active compounds, and the permeability coefficient (Pe) value for the most active compound was 9.40 ± 0.89 (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Structure–activity relationship of N-(pyridin-2-yl) derivatives (docking image reprinted with permission from ref. 65, the American Chemical Society, Copyright 2024).

2.2. SAR of isonicotinamide derivatives

Isonicotinamide is a low molecular weight compound primarily used in anti-malarial drugs.67 Stauffer et al. (2007)68 reported that isonicotinamides function as β-secretase inhibitors. Jiang et al. (2018) found that isonicotinamides are dual inhibitors of both GSK-3β and AChE.69 Luo et al. (2016)70 also identified isonicotinamide derivatives as orally active GSK-3β inhibitors.

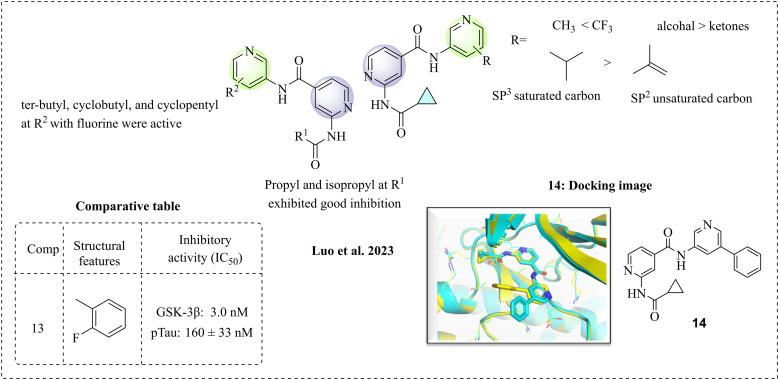

2.2.1. N-(Pyridin-3-yl)-2-amino-isonicotinamides

Luo et al. (2023)57 presented N-(pyridin-3-yl)-2-amino-isonicotinamide derivatives as selective GSK-3β inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease. This research team made structural modifications to the isonicotinamide molecule, which were reported in their previous study. The synthesised molecules were examined for structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies. Isonicotinamide was substituted at the R position with alkyl, cycloalkyl, phenyl, trifluoromethyl, and morpholine moieties, showing various levels of inhibition. Methyl substitutions exhibit less inhibitory activity, whereas trifluoromethyl substitutions have improved activity. The substitutions containing unsaturated sp2 carbon were active, whereas the saturated derivatives showed no activity. Among the cycloalkanes, the cyclobutyl ring exhibits greater activity than the cyclopentyl and cyclohexyl moieties, supporting the idea that the size of the ring influences the activity. The tertiary alcohol exhibited greater activity than ketones, trifluoracetic acid, and secondary alcohols. At the R position, piperidines and morpholines with various substitutions were examined, and most displayed minimal activity; a possible reason for this might be the increase in electron density. The isopropyl group at R1 showed significant inhibition, while the tertiary butyl, cyclobutyl, and cyclopentyl groups without a fluorine atom had minimal effects. However, when a fluorine atom was substituted, they exhibited potent inhibition. The reason for this might be that the fluorine atom is essential for H-bond formation at the binding site. At R2, polar groups such as amine, hydroxy and ether are active, possibly forming a hydrogen bond. The computational studies confirmed the significance of the interactions with the binding sites. Molecule 14 demonstrated important interactions, such as hydrogen bonds formed by the nitrogen in the pyridine at the hinge region. Additionally, the amide bond is vital for kinase activity, while the phenyl group is exposed to the solvent in an accessible area (Fig. 8). The synthesised compounds were selective towards GSK-3β; among the compounds, 13 is the most active against GSK-3β and pTau protein (Fig. 4a). However, it was found to be orally unstable due to its hydrolysis by amidase enzyme.

Fig. 8. SAR of isonicotinamide derivatives (docking image reprinted with permission from ref. 70, the American Chemical Society, Copyright 2016).

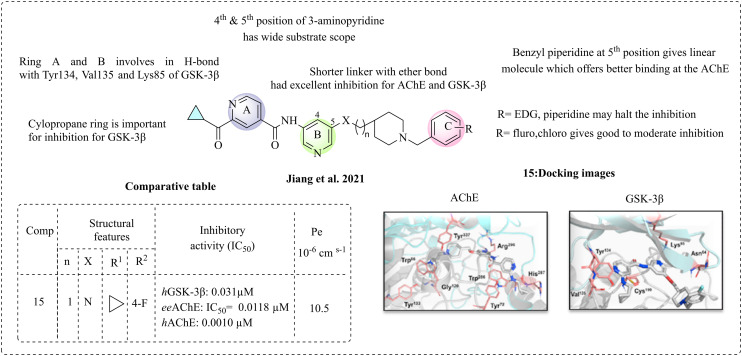

2.2.2. N-(5-(Piperidin-4-ylmethoxy)pyridin-3-yl)isonicotinamide

In 2021, Jiang et al. introduced a novel analogue of N-(5-(piperidin-4-ylmethoxy)pyridin-3-yl)isonicotinamide as a dual inhibitor of GSK-3β and AChE.71 Their research focuses on the initial reports of acylaminopyridine as a dual inhibitor of GSK-3β and AChE (Luo et al., 2016).70 A novel framework incorporating benzyl piperidine based on donepezil, which targets AChE, and pyridyl–isonicotinamide, targeting GSK-3β, has been developed. Cyclopropane carboxamide at ring A may enhance the potency and is involved in a hydrogen bond at the hinge region of GSK-3β. Molecular docking studies confirm that the cyclopropane carboxamide moiety and the nitrogen atom of pyridine form hydrogen bonds with Val135 and Lys85 in the hinge region, respectively. In the case of AChE inhibition, ring A is responsible for π–π stacking interactions, while the nitrogen atom of ring B interacts with Arg 296 of AChE. The 3-amino pyridine (ring B) is involved in the H-bond interactions in the hinge region, and various substitutions, such as positions 4 and 5 of 3-aminopyridine, are favourable for modification. The presence of benzyl piperidine at position 5 of ring B may offer better inhibition than position 4, given that position 5 gives a linear molecule, which smooths the binding at AChE. The introduction of benzyl piperidine (ring C) may provide a planar structure, which may be responsible for dual inhibition. Introducing a pyridinyl ring is more favourable because the nitrogen atom in the pyridinyl ring forms a crucial hydrogen bond with the Lys85 amino acid of GSK-3β, potentially enhancing both the physiological and pharmacokinetic properties. The electron-donating groups on benzyl piperidine (ring C) inhibit AChE but enhance GSK-3β inhibition. At the same time, F and Cl may improve GSK-3β and AChE inhibition. The length of the linker between pyridine amide and piperidine affects the inhibition of both targets. Shorter linkers do not enhance GSK-3β inhibition, while longer chains provide better inhibition of AChE. The binding site of GSK-3β is conserved with bulkier residues, and AChE has a longer, narrower space. Analogues with an amide group may create steric crowding and limit inhibition. An ether bond is used instead of an amide to minimise steric hindrance. This modification leads to greater inhibition of both GSK-3β and AChE, suggesting that ether bonds reduce the steric clouding and enhance the flexibility for both targets. Additionally, a 13-fold increase in potency for GSK-3β is observed. 1H-Pyrrolopyridine was used instead of a cyclopropane group to eliminate steric interactions, but it was inactive against AChE, indicating that cyclopropane is crucial for inhibition. The designed molecules were synthesised and studied to inhibit AChE and GSK-3β. Among the newly synthesised compounds, compound 15 was the most potent and active against AChE and hGSK-3β. The active compound 15 underwent further testing for cholinesterase and multi-kinase activity, demonstrating effectiveness against 18 kinases. The highest selectivity was observed for GSK-3β. Additionally, the ability of this compound to penetrate the blood–brain barrier (BBB) was evaluated using PAMPA. The most active compound was shown to cross the BBB with an effective permeability coefficient (Pe) of 10.5 × 10−6 cm s−1, confirming that these compounds can successfully enter the brain (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. SAR of isonicotinamide derivatives (docking images reprinted with permission from ref. 71, Elsevier, Copyright 2021).

2.3. Thiadiazolidine-3,5-dione derivatives

The thiadiazolidine-3,5-dione ring has shown activity against GSK-3β and has been identified as a promising scaffold for treating Alzheimer's disease. SAR studies on thiadiazolidine-3,5-dione were conducted by Martinez et al. in 2002.73,74 Tideglusib, a non-competitive ATP inhibitor, successfully advanced through phase II clinical trials for Alzheimer's disease and features a 1,2,4-thiadiazolidine-3,5-dione framework. Although studies suggest that tideglusib may act through covalent inhibition, conclusive evidence is still lacking.75

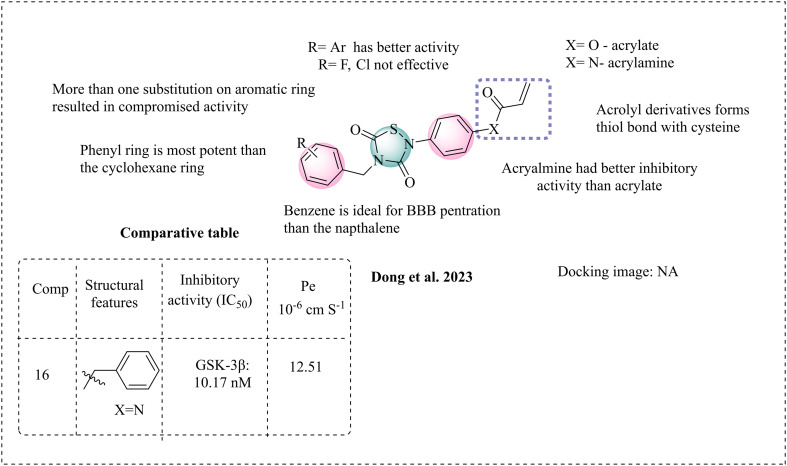

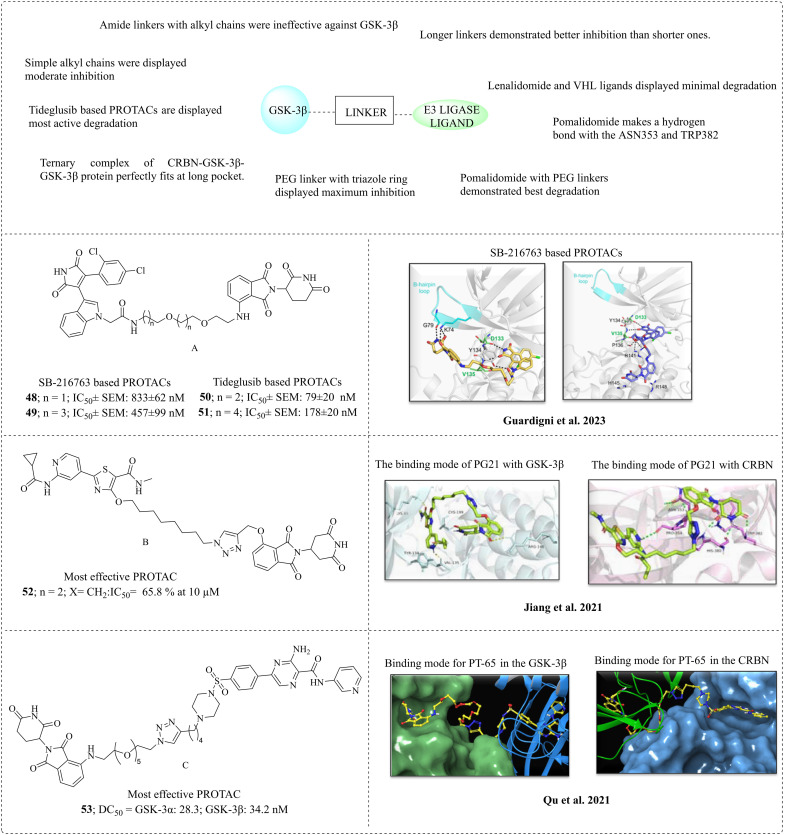

2.3.1. Thiadiazolidine-3,5-dione as a covalent inhibitor

Dong et al. synthesised covalent inhibitors to treat Alzheimer's disease. The covalent inhibition of GSK-3β represents a novel strategy in AD drug development.76 Covalent inhibition usually occurs when a molecule has functional groups that can form a thiol bond with sulfur-containing amino acids. GSK-3β contains sulfur-containing amino acids such as cysteine and serine, which are located at its ATP-binding site. These amino acids are primary targets for achieving covalent inhibition. Martínez et al. reported the first covalent inhibitors targeting the Cys199 amino acid.77 AstraZeneca disclosed the reversible ATP competitor AR-A014418.78 Later, Lo Monte et al. reported a modified AR-A014418 containing benzothiazole and pyridine with reduced toxicity.79 In this regard, Dong et al. designed compounds based on 1,2,4-thiadiazolidine-3,5-dione for Alzheimer's disease (AD). Their design approach involved modifying the naphthalene moiety of tideglusib with acryloyl groups. However, modification increased the topological polar surface area (TPSA) from 44.01 Å2 (tideglusib) to 73.11 Å2 (acrylate) and 70.31 Å2 (acrylamide). A higher TPSA is associated with poor permeability and bioavailability issues.80 The molecular weight increased from 334.5 to 403 for acrylate and 404 for acrylamide, which is non-ideal to cross the BBB. Alternatively, replacing the naphthalene moiety with acryloyl benzene does not significantly alter the TPSA of tideglusib, and its molecular weight may decrease slightly, facilitating the crossing of the BBB. The designed molecules were synthesised and studied for activity against GSK-3β, and compound 16 revealed notably good inhibition, similar to that of the reference drug tideglusib. Insights into their structure–activity relationships (SAR) indicate that acrylamide exhibits better inhibition than acrylate. This may be attributed to the stability of the amide group. Substitutions at the R position demonstrate stronger lipophilicity and enhanced inhibitory activity. Additionally, phenyl moieties show better activity compared to cyclohexyl moieties. However, electron-withdrawing groups such as fluorine (F) and chlorine (Cl) at the R position are ineffective. Furthermore, introducing more than one substitution at the R position reduces the activity, likely due to the increase in molecular topological polar surface area (TPSA) and other pharmacokinetic properties. This indicates that simpler structures such as phenyl are favourable than bulkier groups. Enhanced inhibitory activity was noted when a methylene bridge was present between the 1,2,4-thiadiazolidine-3,5-dione ring and the six-membered ring. The in vitro blood–brain barrier (BBB) studies were conducted on compound 16 through the PAMPA. This compound demonstrated greater permeability, with a permeability coefficient (Pe) of 12.51 × 10−6 cm s−1, indicating its effectiveness in crossing the BBB. Additionally, a binding test with 2-mercaptoethanol was performed to evaluate covalent inhibition (Fig. 10). 2-Mercaptoethanol mimics the Cys amino acid and forms a thiol bond with acrylamide in compound 16. 2-Mercaptoethanol was dissolved in a mixture of methanol and water in a 2 : 1 ratio, and the products were isolated. The 1H NMR spectrum shows thioether bond formation, indicating that 16 binds with the cysteine amino acid at the ATP binding pocket of GSK-3β.

Fig. 10. Illustration of the SAR of thiadiazolidine-3,5-dione.

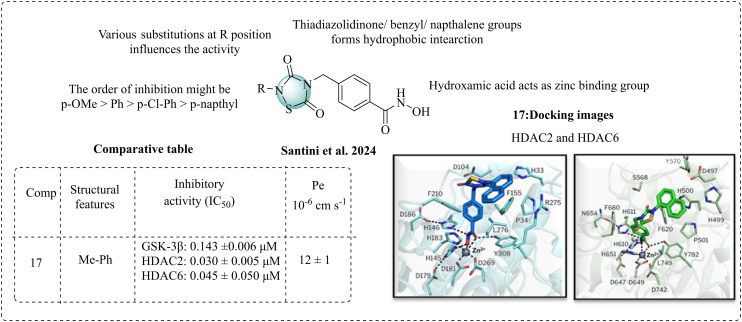

2.3.2. Thiadiazolidinone with benzyl and naphthalene moieties

Santini et al. 2024 reported a combination of GSK-3β and HDACs as a dual inhibitor for AD. These researchers aimed to develop novel non-ATP inhibitors that target both GSK-3β and HDACs.81 HDAC inhibitors and linkers require a zinc-binding group and a CAP (compound active portion). Tideglusib has pharmacophoric features, which contain a thiadiazolidinone structure with benzyl and naphthalene moieties. The research team utilised this structure as the CAP group and incorporated hydroxamic acid through linkers to serve as the zinc-binding component. The thiadiazolidinone ring also has potent activity against GSK-3β. The biological studies displayed satisfactory GSK-3β inhibition, with IC50 values in the range of 0.084–0.142 μM, confirming that the various substitutions, such as p-OMe-Ph > p-Cl-Ph > p-Me-Ph > p-naphthyl groups, are responsible for the activity against GSK-3β. para-Methoxy derivatives have emerged as the most potent molecules. Other derivatives such as para-naphthyl substituents resemble tideglusib and have good inhibition, whereas the methyl derivative also has good inhibition. The HDAC inhibitory studies displayed that most of the compounds were active. The most active compound 17 has potent inhibition against HDAC2 and 6. Molecular docking was performed to determine its binding pattern. The main scaffold thiadiazolidinone and terminal aromatic moieties can form a hydrophobic interaction at the lining of the pocket. Cap moieties can interfere in the L1–L2 loop region of HDAC2 and 6 (Fig. 11). After reviewing both the GSK-3β and HDACs inhibitory results, compound 17 advanced to further studies. The docking studies performed on HDAC2 and HDAC6 and outcomes of the BBB studies indicate that compound 17 crossed the BBB with a permeability (Pe) value of 12 ± 1, and its pharmacokinetic properties were studied using the in silico SwissADME software.

Fig. 11. SAR of thiadiazolidine-3,5-dione (docking images reprinted with permission from ref. 81, the American Chemical Society, 2024).

2.4. SAR of tacrine derivatives against GSK-3β

Tacrine-based molecules are key fragments for the development of Alzheimer's, with studies showing they can inhibit AChE activity and Aβ aggregation.82–85 The Cholinergic hypothesis is one of the proposed mechanisms underlying the pathophysiology of Alzheimer's disease (AD). It suggests that reduced levels of acetylcholine, a crucial neurotransmitter, are observed in individuals with AD. This decline may be attributed to lower amounts of the enzyme choline acetyltransferase (CAT), which is primarily responsible for synthesising acetylcholine. This reduction in acetylcholine can lead to neuronal death. Also, some studies demonstrated that the APP may impact the overactivation of AChE and reduce the activity of the CAT enzyme.86

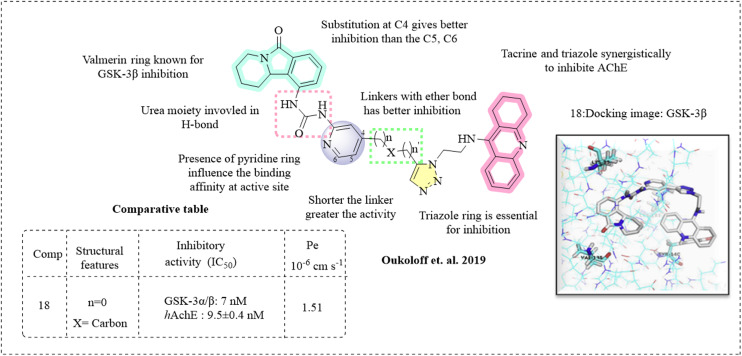

2.4.1. Tacrine and valmerin derivatives

Oukoloff et al. (2019) reported novel multifunctional ligands as AChE and GSK-3β inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease.87 The scaffolds are tacrine and the isoindolone derivative valmerin, which acts as a GSK-3β inhibitor. The tacrine and isoindolone moieties were tethered by a triazole. Molecular docking studies were executed to gain insights into the binding properties of the linker and two molecular frameworks. The studies revealed that upon ligand binding, a unique conformational elasticity arises at the active gorge site of AChE. The binding pattern displayed that the presence of linkers at the C4 position of pyridine is more favourable, which offers a linear molecule suitable for AChE binding. The tetrahydroacridine and triazole moieties interact through π–π stacking, forming a hydrogen bond. The carbonyl moiety of the urea functionality of the valmerin ring forms a hydrogen bond. The designed molecules were docked against the crystal structure of GSK-3β, where their S-isomer shows a low binding energy compared to their R-form, and the carbonyl moiety of tetrahydropyridoisoindolone forms a hydrogen bond at the hinge region with Val135, Lys183, and triazole and cation–π interaction with the pyridine ring. The synthesised compounds were tested for their potency against GSK-3β and AChE. Most of the compounds were potent inhibitors in the sub-nanomolar to nanomolar range. Inhibitory studies demonstrated the SAR, where substitution at the C4 position of pyridine is more potent than substitution at the C5 and C6 positions. The presence of both triazole and tacrine moieties is crucial for kinase inhibition. The triazole moiety plays a vital role in the binding of GSK-3β. Collaborative inhibitory activity was observed when both the triazole and isoindole moieties are present. Hydrophobic groups, such as phenyl, may enhance the activity, whereas introducing more polar groups can decrease it. Both the R and S forms are effective, but the R form demonstrates more potent inhibition against GSK-3α/β and hAChE (18). The synthesised compounds had good permeability and BBB penetration abilities with an efflux ratio of 1.51 (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12. SAR of tacrine (docking image reprinted with permission from ref. 87, Elsevier, Copyright 2019).

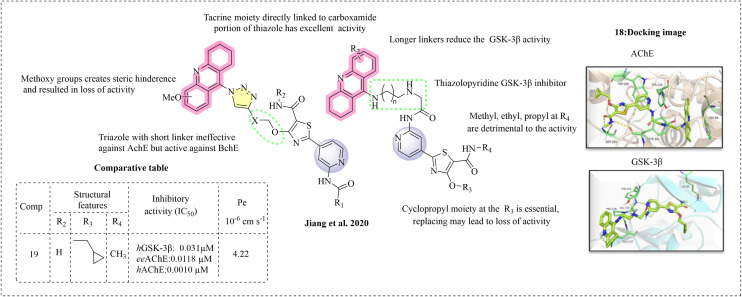

2.4.2. Tetrahydroacridine and thiazolopyridine

Jiang et al. (2020) synthesised a dual of GSK-3β and AChE for treating Alzheimer's disease.88 The design technique connects a tetrahydroacridine fragment with the thiazolopyridine scaffold through a linker, which is based on previous research.89 They synthesised two types of series. In series 1, cyclocarboxamide remains unchanged, and the tacrine moiety is attached to the hydroxyl group of the thiazole ring. In series 2, the tacrine moiety is linked to the carboxamide group by replacing the cyclopropane ring. The designed molecules were prepared and studied for their inhibition of both GSK-3β and AChE to evaluate the modifications made on the thiazolopyridine fragment (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13. SAR of tacrine (docking images reprinted with permission from ref. 88, Elsevier Copyright 2020).

Series 1

The series 1 molecules have better stability, which might be due to the linker to the hydroxyl moiety of thiazole, the free carboxamide and the N atom of pyridine available for interaction at the hinge region. The series 1 molecules have good GSK-3β inhibition, while their AChE inhibitory activity was disappointing. The narrow catalytic site may hinder interactions at the active site. However, these compounds were active against BChE given that it has a larger and more rigid catalytic cavity. An additional number of carbons were introduced between triazole and tacrine to address this issue, resulting in improved activity. This enhancement may be attributed to the linker aiding in the maintenance of the thiazolopyridine at the peripheral anion site (PAS). However, the presence of a methoxy group on the tacrine moiety led to a loss of activity, possibly due to the steric clouding of the methoxy groups disrupting the tacrine moiety from fitting in the CAS site of AChE.

Series 2

In the series 2 derivatives, it was observed that activity loss occurs when the carboxamide portion of the thiazole moiety is linked to tacrine. This indicates that the free carboxamide and the N atom of pyridine are essential for inhibition. The ortho-aminopyridine occupies the solvent-exposed area and may not exert the necessary interaction at the binding region, such as a hydrogen bond at the hinge region. ortho-Aminopyridine is linked to tacrine with linkers of various lengths, but there is no proof of GSK-3β inhibition. Longer linkers reduce the GSK-3β activity. Substitution of ethyl and propyl moieties on the carboxamide group of thiazolopyridine reduces the GSK-3β inhibition, whereas methyl on the free carboxamide gives satisfactory inhibition. The cyclopropyl group on the thiazole moiety is ideal for inhibiting methyl, isopropyl, and tert-butyl moieties. The most potent compound, 19, has excellent dual inhibition with a cyclopropane ring at R3 and a methyl at the R4 position on the thiazole ring with one carbon. Compound 19 fits at the GSK-3β binding site by involving various amino acids such as Lys85, Tyr134, Val135, and Cys199, and molecular dynamic simulations for both GSK-3β and AChE illustrate Van der Waals interactions and electrostatic interactions involving various amino acids. The synthesised molecules were studied for BBB penetration using PAMPA and compared with commercial drugs exhibiting varying levels of permeability. All the synthesised compounds can cross the BBB with Pe > 4.22 × 10−6 cm s−1, and the most active compound 19 has the effective permeability rate Pe = 7.1 × 10−6 cm s−1, evidencing its effective BBB penetration.

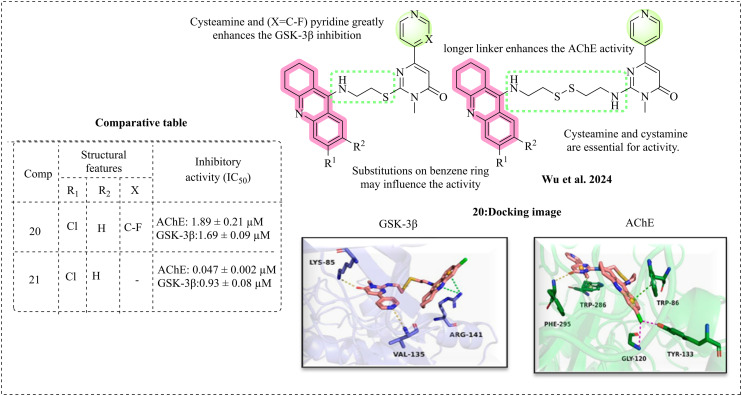

2.4.3. Tetrahydroacridine–cystamine and cysteamine

Wu et al. 2024 disclosed new hybrids of tetrahydroacridine with a sulphur-containing linker for AD. The linkers are cystamine and cysteamine, joined to the pyridinyl pyrimidone moiety for GSK-3β inhibition.90 The designed molecules were synthesised and examined for inhibition; compounds 20 and 21 emerged as the most potent compounds and active against AChE and GSK-3β. Studies revealed that the cysteamine linker exhibited better inhibition compared to cystamine. It has been reported that the sulfur-containing groups may enhance the flexibility of the binding site.54 The SAR analysis reveals that the tacrine moiety is essential for AChE inhibition. Various substitutions on the benzene ring of tacrine may influence the activity, such as chloro, which has optimal inhibition compared to bromo. Longer linkers may enhance the AChE activity; a more extended linker holds the active portions of compounds towards the PAS and CAS regions of AChE along the narrow and straightened pocket. In the case of GSK-3β inhibition, it is greatly enhanced by the combination of cysteamine and fluoropyridine. The tacrine moiety enhances the binding affinity of molecules towards GSK-3β. The inhibitory activity was halted when cysteamine and cystamine were replaced with an alkyl group, evidencing that cysteamine and cystamine are indispensable for the activity. The molecular docking analysis of the most active compound supports the inhibitory results for both AChE and GSK-3β. The docking analysis reveals that pyrimidone and tacrine occupy the interior and exterior of GSK-3β, respectively. The N-atom of pyridine and the carbonyl oxygen moiety form hydrogen bonds with the Val 135 and Lys85 residues. The benzene and pyridine rings of tacrine may be responsible for the π–π stacking interactions (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14. SAR of tacrine (docking images reprinted with permission from ref. 90, Springer-Verlag, Copyright 2024).

2.5. SAR of phthalimide/maleimide derivatives

The maleimide scaffold has excellent activity and is selective towards GSK-3β. Radiolabelled maleimides were reported for PET imaging, which is helpful for detection.91 Maleimide analogue bisindolylmaleimides were synthesised based on the structure of staurosporine. However, these moieties suffer from limitations such as toxicity, poor solubility and selectivity. These issues can be avoided by combining them with other heterocyclic compounds.92–95

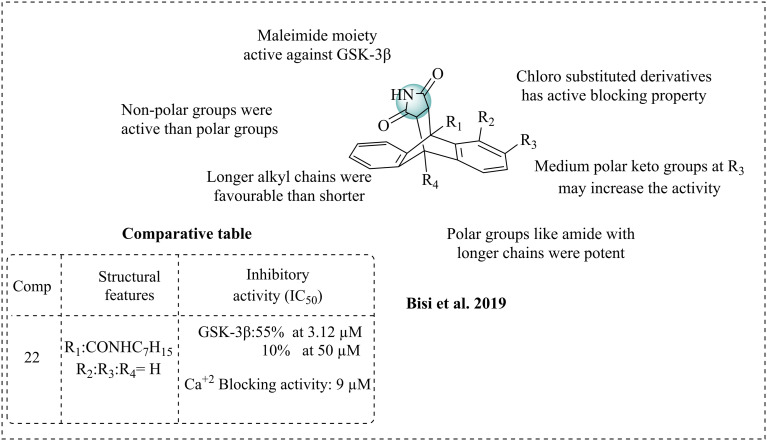

2.5.1. Anthracene–maleimide derivatives

Bisi et al. (2019) first reported dual inhibitors targeting neuronal calcium channels and GSK-3β, which were composed of anthracene–maleimide derivatives.96 The maleimide scaffold has been proven to be active against GSK-3β. Earlier, this group reported polycyclic maleimide as an LTCC blocker (lacking intracellular effects in vascular smooth muscle) to achieve reduction of Ca2+ levels. In Alzheimer's disease, enhanced levels of Ca2+ may cause oxidative stress and worsen the condition. Thus, inhibiting the levels of Ca2+ in the brain may be a profitable strategy for curing AD. Utilising polycyclic maleimide with substitutions and an anthracene scaffold with electron-withdrawing groups and -donating groups may achieve GSK-3β inhibition and reduce the levels of Ca2+. The synthesised molecules were first tested for their cardiovascular profile to determine the Ca2+ influx; all the synthesised compounds have good antagonistic properties for Ca2+ influx, and later the effect of Ca2+ in neuronal cells was studied through VGCC (voltage-gated calcium channel) in the SH-SY5Y cell lines. The studies revealed that most of the synthesised compounds could reduce the Ca2+ levels in the SH-SY5Y cell lines. Potent molecules arise from all the compounds with Cl and an amide bond with alkyl chains. The systematic SAR was evaluated; non-polar groups such as chlorine and long alkyl chains displayed the maximum Ca2+ blocking activity and were responsible for hydrophobic interactions. Replacement of non-polar groups with a polar group, such as a ketone, may reduce the activity. However, the most potent compound 22 (IC50 = 9 μM) has a polar amide and is still able to reduce the Ca2+ levels, which might be due to its long alkyl chain. Changing the substitution position on the aromatic ring does not affect the activity, indicating that substitution at any position is favourable. The study on GSK-3β inhibition indicated that long alkyl chains may effectively inhibit this enzyme, while their replacement could diminish the activity. The synthesised molecules may not inhibit the overexpression of GSK-3β but instead regulate its activity to restore normal physiological levels. Most of the compounds exhibited average GSK-3β inhibition, and 22 has effective Ca2+ blocking activity and medium GSK-3β inhibition among the compounds (Fig. 15).

Fig. 15. SAR of anthracene–maleimide derivatives.

2.5.2. Maleimide hybrid hydroxamic acid via polymethylene linkers

Simone et al. 2019 first disclosed a novel combination dual inhibitor of GSK-3β and HDAC for treating AD.97 The epigenetic properties of HDAC in the progression of Alzheimer's disease involve HDAC being primarily responsible for the deacetylation of histones. Furthermore, deacetylation of the serine residue of tau increases its susceptibility to phosphorylation by GSK-3β. The hyperphosphorylation of the tau protein eventually led to NFTs. Inhibiting HDAC and GSK-3β regulates the acetylation and phosphorylation of tau, respectively. By examining the pharmacophoric features of the HDAC and GSK-3β inhibitors, it is found that hydroxamic acid and aromatic moieties, especially polyaromatic moieties, are vital to chelate the zinc-binding site of HDAC and form interactions at the hinge region of GSK-3β. The aromatic moieties may occupy the doorway of the active site, which acts as a cap group; linkers were used to tie both the hydroxamic acid and aromatic moiety. The hydroxamic acid is chelated at the Zn2+ binding region of HDAC. The maleimide portion is essential for the ATP-binding site of GSK-3β. Molecules were prepared by linking the maleimide to hydroxamic acid via thioureido–polymethylene of varying lengths. Biological studies against GSK-3β, HADAC1 and HDAC6 displayed that all the newly synthesized molecules were active towards these three enzymes, and among them, compound 23 was active towards both GSK-3β and HDAC6 (SB415286: IC50 = 0.05 ± 0.01 μM, vorinostat: IC50 = 5.6 μM as the standard drug) but the least active towards HDAC1 (Fig. 16). The SAR studies clearly state the importance of the length of the linker, given that the most active compound has a chain length of 4, whereas the least active molecules have a chain length of 1, 2, and 3. Molecular docking analysis was carried out to determine the binding pattern for GSK-3β. The outcomes highlighted the importance of maleimide in terms of inhibition, given that it forms two hydrogen bonds at the hinge region, thiourea involves a hydrogen bond interaction with the backbone carbonyl Q185 residue, and the lengthened linker facilitates the entry of hydroxamic acid into the polar region. The docking analysis of HDACs indicates that hydroxamic acid chelates at the zinc-binding site, and the aliphatic linker interacts with the aromatic side chains. Thiourea is involved in a bifurcated hydrogen bond with D99 in HDAC1 and S538 in HDAC6. Phthalimide occupies the histidine region; phthalimide is the best fit at the substrate binding pouch of HDAC6, signifying the unsurpassed activity over HDAC1.

Fig. 16. SAR of phthalimide/maleimide derivatives (docking images reprinted with permission from ref. 97, the American Chemical Society. Copyright 2019).

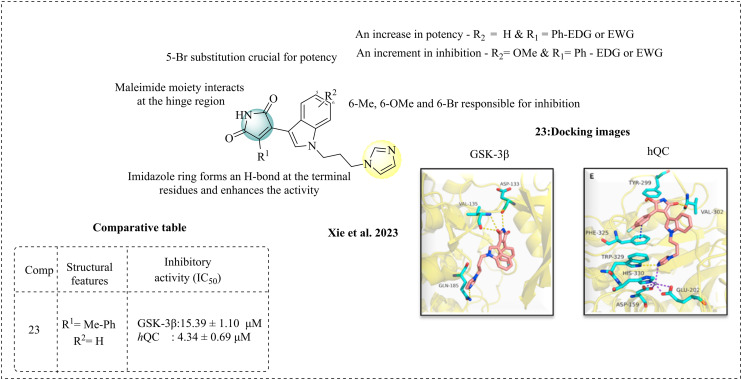

2.5.3. Maleimide and imidazole scaffolds

Xie et al. (2023) developed a novel series of maleimide and imidazole scaffolds as dual inhibitors of glutaminyl cyclase (QC) and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β) for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease (AD). QC is an enzyme that facilitates the production of pyroglutamate-Aβ (pE-Aβ).98 The physiology of Aβ plaques indicates that most Aβ plaques contain pyroglutamate-Aβ (pE-Aβ), which is resistant to degradation and causes excessive cell toxicity. Additionally, GSK-3β is involved in tau phosphorylation, contributing to the formation of Aβ plaques. This team focused on inhibiting glutaminyl cyclase (QC) and GSK-3β. They synthesised maleimide and imidazole scaffolds that target both enzymes to achieve this. The warheads, such as imidazole or benzimidazole, can bind to the Zn2+ site and act against GSK-3β. The synthesised compounds were tested for their potencies against both targets. According to the results, the IC50 values of all the synthesised compounds were in sub- and low micromolar concentrations. The SAR studies state that imidazole and maleimide, connected by a propylene linker, may influence the activity. The imidazole moiety occupies the narrow portion and chelates the Zn2+ binding site. The maleimide scaffold may be active against GSK-3β, but it appears ineffective against QC. However, various substitutions at the position 5 or 6 (R2) influence the activity and form interactions at the hydrophobic region. The EWGs at position 6 are more favourable than the EDG. This is due to the steric burden caused by EDG at the binding site, which reduces the activity. In the case of GSK-3β, most of the compounds were active and provided gainful insights into SAR, where R1 and R2 substitutions demonstrated effective inhibition and potency. The substitution of 5-Br enhances the potency, while 6-methyl, 6-methoxy, and 6-Br substitutions may contribute to the inhibition. The correlation between inhibition and potency was observed with various substitutions of R1 and R2, where an increase in potency was noted when R1 was phenyl, either with electron-donating or withdrawing groups. At the same time, R2 remained unsubstituted or as hydrogen. An increment in inhibition was observed when R1 is phenyl with EDG or EWG, having R2 as a methoxy group. However, EDG such as methyl and methoxy were active against GSK-3β but not towards QC because these groups are situated near the GSK-3β active site, but distant from the QC active site. The imidazole and propylene linkers form a key interaction at the active site of GSK-3β. Molecular docking studies were performed to determine the binding pattern for both GSK-3β and QC. The docking analysis against QC shows that the imidazole moiety fits in the Zn2+ catalytic site, which is present at the bottom of the pocket. p-F-phenyl is important for π–π stacking interactions at the hydrophobic entrance of the PHE325 pocket; the presence of ortho-nitrophenyl groups disturbs the π–π stacking interactions and chelation between imidazole and Zn2+ at the site. The maleimide ring is essential for hydrogen bonds. The docking analysis of GSK-3β shows that Asp133 and Val135 at the ATP binding site are involved in the H-bond with the maleimide and imidazole ring, forming another hydrogen bond at the terminal. Gln185 is another essential amino acid that facilitates binding and enhances the activity. The molecular docking studies conclude that maleimide is essential for QC inhibition and imidazole for GSK-3β inhibition. Among the molecules, compound 23 exhibited the greatest potency for both targets. The most active compound 23 exhibited fading of both Aβ and pE-Aβ accumulation, and also lowered the tau hyperphosphorylation, demonstrating its activity for both targets as a dual inhibitor (Fig. 17).

Fig. 17. SAR of phthalimide/maleimide derivatives (docking images reprinted with permission from ref. 98, Elsevier, Copyright 2019).

2.6. SAR of β-carboline derivatives

The harmine alkaloid is known for its effects on CNS targets, including AChE, monoamine oxidase, NMDA, and GSK-3β, and features a β-carboline scaffold. Hamann et al. (2007) reported that manzamine A, a β-carboline derivative, is a GSK-3β inhibitor with an IC50 value of 10.2 μM.99 Harmine derivatives also show significant activity against DYRK1A, a kinase that catalyses the GSK-3β signalling cascade, leading to tau phosphorylation and Aβ generation. The ATP-Glo-kinase assay of harmine shows GSK-3β inhibition with an IC50 value of 32 μM. Structure–activity relationship studies of β-carboline against DYRK1A have reported and explained the essential features of positions 1, N-9, and 7 of harmine.100

2.6.1. β-Carboline and modification at position 7

Based on these investigations, Liu and colleagues (2021) introduced a novel combination of dual inhibitors of GSK-3β and DYRK1A for treating AD.101 The molecular framework was constructed using β-carboline, and molecular docking studies were conducted for GSK-3β and DYRK1A. Although these proteins are similar, they showed different binding properties with β-carboline. The nitrogen atom in pyridine, the amide group at position 1 or 2, and the 7-methoxy group of β-carboline are essential for binding with DYRK1A and GSK-3β. The newly synthesised molecules were tested for their inhibition against GSK-3β, showing inhibition at a concentration of 10 nM, while harmine exhibited inhibition at 32 nM. Biological evaluation and docking studies evidence that modification at position 7 and the incorporation of an amide group at position 1 or 3 might be beneficial. The amide group at position 1 facilitates an intramolecular hydrogen bond, which eases the bond formation with Val135 in the hinge region. The carbonyl oxygen of the methoxy ester at position 7 of β-carboline interacts with Lys85 of GSK-3β and Lys188 of DYRK1A, resulting in excellent inhibition. Electron-withdrawing groups at position 7 of β-carboline impact the inhibition of GSK-3β, such as trifluoromethyl and cyano, which are detrimental to GSK-3β inhibition. A decrease in inhibition was observed when position 7 of β-carboline is substituted with halogens, aromatic or heteroaromatic moieties. However, effective inhibition was observed with cyclopropanamide at C1, which forms an H-bond with Val135 of GSK-3β and Lys248 of DYRK1A. In contrast, methyl is the least effective, given that it cannot create the required interactions. The most active compound 24 with 7-methoxy effectively exhibited GSK-3β and DYRK1A inhibition. Staurosporine and harmine were taken as reference compounds for GSK-3β. The molecular docking studies were conducted for the most active compound 24 for GSK-3β and DYRK1A to know the binding pattern. Most of the newly synthesised compounds exhibited effective crossing; the most active compound crossed the BBB with the Pe > 4.7 × 106 cm s−1 (Fig. 18).

Fig. 18. Key points of SAR of β-carboline (docking images of GSK-3β reprinted with permission from ref. 21, Elsevier, Copyright 2021; DYRK1A: from ref. 101, Elsevier, Copyright 2022; AChE; from ref. 103, Elsevier, Copyright 2022).

2.6.2. β-Carboline with benzyl piperidine

This team conducted further exploration into a novel combination of GSK-3β and AChE inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease (AD). The design strategy involves stabilising positions 1 and 7 of β-carboline using cyclopropylcarboxamide and amide functionalities. Additionally, they aimed to connect N-benzyl piperidine using various-sized linkers to target AChE effectively.102 Most compounds were active against AChE with an IC50 value of 0.27 μM to 33.48 μM, which postulates that the alterations gave positive results. The GSK-3β inhibition studies disclosed that small-sized linkers, such as two-carbon linkers, may enhance the inhibition more than one-carbon linkers. The electron-withdrawing groups on the benzene ring of benzyl piperidine might be responsible for the potency. Among the compounds tested, 25 showed potent inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and reasonable inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β). Molecular docking studies confirm that N-benzyl occupies the CAS region through π–π interactions with Trp86 of AChE, piperidine may interact with the gorge site, and β-carboline interacts at the PAS region with Trp-286. The fluorine atom forms hydrogen bond interactions with the carbonyl oxygen of the His447 residue. The binding pattern against GSK-3β is that β-carboline occupies the ATP binding region, the N atoms of β-carboline and cyclopropanecarboxamide form key hydrogen bonds with Val135 and Lys85, respectively, the amide bond at position 7 forms a hydrogen bond with the Lys85 residue, and benzyl piperidine occupies the solvent-exposed area (Fig. 18).

2.6.3. β-Carboline-fused benzyl piperidine with triazole as linker

This team optimised their previous work on β-carboline against AChE and GSK-3β. As stated, positions 1, 3, and 7 are proven to be active against GSK-3β and AChE. The modification of compound 24 at position 7 with a triazole moiety occurs via an amide bond connected to benzyl piperidine.103 Most of the compounds were potent against both AChE and GSK-3β, and the results evidence that the compounds with cyclopropylcarboxamide at the C1 position and triazole as the linker displayed considerably higher AChE and GSK-3β inhibition than that with cyclopropylcarboxamide at the C3 position with a triazole moiety. When the cyclopropane ring is replaced with cyclobutyl, cyclopentyl, cyclohexyl, or phenyl, the inhibition against both targets varies. As the size of the ring increases, inhibition decreases, highlighting the significance of the ring size. Various substitutions such as 2-F, 3-F, 4-F, 4-CH3, 4-CF3, 3,5-di-2F, and 4-Cl at R1 show diverse inhibitory activities. The 2-F compound was found to be active against both AChE and GSK-3β. Compound 26 exhibited high potency against GSK-3β and AChE. It is selective towards BChE (Fig. 18). Molecular studies revealed that the binding pattern of β-carboline and N-benzyl is the same as that of previous compounds that occupy the PAS and CAS regions. Meanwhile, the triazole moiety interacts with the Tyr337 and Tyr341 residues of AChE. Docking studies against GSK-3β reveal that 1,2,3-triazole-benzyl occupies the exterior portion and β-carboline occupies the interior part of GSK-3β. The pyridine N atom, cyclopropylcarboxamide and amide at position 7 involve a hydrogen bond in the hinge region. The benzene ring of β-carboline forms a thiol bond with Cys199. The 1,2,3-triazole moiety forms a hydrogen bond with the Lys85 residue. The PAMPA-BBB assay was employed to study the brain penetration ability of the most active compound. The permeability studies of the active compound 5.983 ± 0.836 (10−6 cm s−1) proved its potentiality to cross the BBB. Qiu and Liu 2024 continued their work on β-carboline as dual GSK-3β/DYRK1A inhibitors and found that ZLQH-5 is a potent compound.104

2.7. Aryl-3-(4-methoxybenzyl) urea–benzothiazole/benzimidazole

Venter et al. (2019)105 synthesized a novel inhibitor that consists of 1-aryl-3-(4-methoxybenzyl) urea, inspired by the covalent inhibitor AR-A014418. The design strategy incorporated electrophilic warheads on aryl groups, specifically benzothiazole and benzimidazole. These warheads play a crucial role in covalent inhibition by targeting Cys199 of GSK-3β. Examples of these warheads include nitrile, halomethyl ketone, and acrylates, which can potentially form covalent bonds with the Cys199 amino acid. This interaction leads to irreversible, selective, and potent inhibition. The compounds were synthesised, and biological evaluation and molecular docking studies were conducted with AR-A014418 as the reference compound. The results revealed that benzimidazole derivatives demonstrate more effective inhibition than the benzothiazole derivatives. This might be due to the formation of an additional hydrogen bond in the hinge region and an intramolecular hydrogen bond with urea. The electrophilic warheads on the benzimidazole ring, cyano IC50 = 0.086 ± 0.023 μM (27) and halomethyl ketone IC50 = 0.26 ± 0.030 μM (28) demonstrated excellent inhibition against GSK-3β. At the same time, the reference compound exhibited an IC50 value of 0.072 ± 0.043 μM, indicating its potency against GSK-3β. Conversely, the compounds containing vinyl and ethynyl moieties exhibited low potency, and acrylamides were ineffective in activity. However, nitrile-substituted benzothiazole also has good inhibition. Meanwhile, other derivatives such as vinyl and ethynyl moieties exhibited low potency. The urea moiety of HMK forms a hydrogen bond with the Val135 residue; however, it has a higher distance of 4.5 Å from the sulphur atom of Cys199. The docking scores of the reference compound and the newly synthesised compounds showed no significant differences; they exhibited identical values for both reversible and irreversible modes but had varying inhibitory rates. Therefore, the docking scores and biological activity may not be correlated (Fig. 19).

Fig. 19. SAR GSK-3β aryl-3-(4-methoxybenzyl) urea–benzothiazole/benzimidazole (docking image reprinted with permission from ref. 105, Elsevier, Copyright 2019).

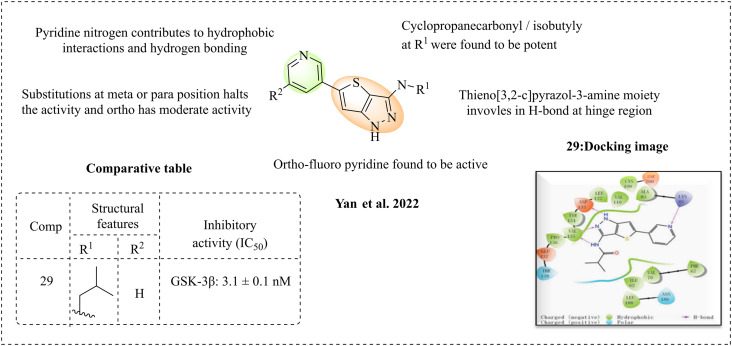

2.8. SAR of thieno[3,2-c]pyrazol-3-amine

Yan et al. (2022) designed a new thieno[3,2-c]pyrazol-3-amine derivative as a potent GSK-3β inhibitor based on studies of small inhibitors such as tideglusib, AR-A014418 and AZD1080.106 According to the SAR studies, isobutyl-substituted molecules were more potent than n-butyl and benzoyl moieties at R1 of cyclopropanecarbonyl, highlighting the significance of the cyclopropane ring, while sulphonamide-substituted molecules were found to be inactive. The inhibition was halted when the pyridine ring was substituted with a phenyl group at the meta position. In contrast, ortho-substituted phenyl, methyl, and methoxy compounds exhibited moderate inhibition. However, fluorinated compounds demonstrated potent activity, indicating that fluorine plays a critical role at the binding site. Substitutions such as trifluoromethyl at the R2 position have less activity, and bulkier rings such as biphenyls and naphthalene are less active, indicating that the ring size may influence the activity. Among the synthesised molecules, compound 29 was the most active. Molecular docking studies support that thieno[3,2-c]pyrazol-3-amine was active against GSK-3β. The results indicate that thieno[3,2-c]pyrazol-3-amine is present at the adenine site and forms hydrogen bonds with Val135 and Asp133. Also, it exerts hydrophobic interaction with Ala83, Val110, Leu132, Asp133, Tyr134, Val135, and Leu188. The N-atom of pyridine acts as an acceptor, forms an H-bond with Lys85, and also has a hydrophobic interaction. The isobutyl group in the most active compound 29 interacts at the hinge region through hydrophobic interaction. The dual-site occupation of thieno[3,2-c]pyrazol-3-amine, which involves hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions, may reveal a new molecule for treating Alzheimer's disease (Fig. 20).

Fig. 20. SAR of thieno[3,2-c]pyrazol-3-amine (docking image reprinted with permission from ref. 106, Elsevier, Copyright 2022).

2.9. SAR of bisindole

Liu et al. 2020 reported the synthesis of bisindole-based GSK-3β inhibitors that mimic the structural properties of staurosporine.107 The design strategy involves replacing the γ-lactam of staurosporine with an aminopyrazole ring and two indole rings on either side of the aminopyrazole ring. The designed molecules were synthesised and tested for in vitro inhibitory activity against GSK-3β. They designed four types of molecules. Type 1: the presence of indolyl at position 4 of aminopyrazoles, adjacent to the amine group, shows no activity. Type 2: an indolyl moiety is located at position 5, opposite the amine group of aminopyrazoles, which feature Cl, Br, and methoxy substitutions, demonstrating strong inhibition. Type 3: the presence of bisindole on both sides of the aminopyrazole showed excellent inhibition against GSK-3β. Type 4: a diazepinoindole ring and indole on the other side demonstrated strong inhibition. The SAR studies of bisindole were derived from the inhibitory results, where a superior enhancement in activity was observed with fluorine or methoxy substitution on position 5 of indole; replacement of fluorine with bromine results in a loss of activity, indicating that the fluorine is essential for inhibition. Various substitutions, at the position 4 or 7 of indole, such as 4-Cl and 7-methoxy groups, respectively, might not be active. Weakened activity was observed when the N-Me indole moiety was replaced with aminoethyl and N-BOC-protected aminoethyl groups. The presence of diazepinoindole with an amide bond uplifts the activity, given that diazepine ring systems have proven activity against various CNS disorders. Among the compounds, 30, 31, 32, 33, and 34 emerged as the most potent compounds (Fig. 21). In vivo studies were executed to determine the inhibition against glial inflammation of the brain, and compound 33 was found to be active and diminishes the inflammation of microglial cells.

Fig. 21. SAR of aryl-3-(4-methoxybenzyl) urea–benzothiazole/benzimidazole.

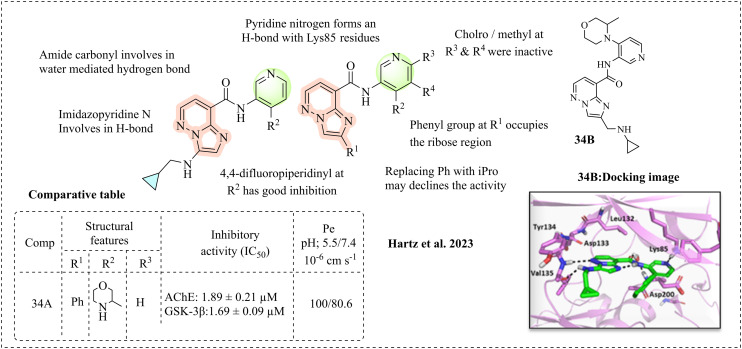

2.10. SAR of imidazo[1,2-b]pyridazine

Hartz et al. (2023) unveiled imidazo[1,2-b]pyridazine derivatives as potential GSK-3β inhibitors based on an extensive SAR study of isonicotinamide-based GSK-3β inhibitors. The studies demonstrate that the carbonyl group of cyclopropyl and the NH of the amide bond perfectly fit at the binding site through key hydrogen bonds, but toxicity was reported as a drawback of the cyclopropyloxamide moiety.108 These studies prompted the development of a new moiety that can withstand essential features and reduce toxicity. Accordingly, this team developed an imidazo[1,2-b]pyridazine moiety by transforming the cyclopropyloxamide moiety with two sub-types, where one type was able to form hydrogen bonds. In contrast, the second type acts as a hydrogen bond acceptor, which may increase its brain penetration. The inhibitory properties of the newly synthesised molecules were studied and had some beneficial outcomes on SAR, where in the first type of molecules, cyclopropyloxamide was retained, and several groups were substituted at the 2nd position of the pyridine ring, such as the 4,4-difluoropiperidinyl moiety, which exhibited excellent inhibition with IC50 = 0.87 nM. Methyl and isopropyl ethers had the maximum inhibition, whereas the phenyl or 6-membered heterocyclic compounds were also active. Molecular docking studies also highlight that the compounds unveil key interactions, such as the sp2 nitrogen of pyridine with Lys85 residues. The amide carbonyl is involved in a water-mediated hydrogen bond; the phenyl group occupies the ribose region and is involved in Van der Waals interactions. The second type of molecules studied involves a pyridine ring, where position 2 of imidazo[1,2-b]pyridazine remains unchanged. In this variation, position 4 has been modified with various substitutions, including methyl, isopropyl, trifluoroethoxy, methylsulfonyl, phenyl, 4,4-difluoropiperidinyl, and substituted morpholines. Among them, the phenyl-substituted molecules were the most potent and improved inhibition was observed. When phenyl was replaced with piperidines and morpholines, subnanomolar inhibition was observed (compound 34A) (Fig. 22). Compromised activity was observed with chloro and methoxy groups at the R3 and R4 positions of pyridine. The phenyl ring may be responsible for hydrophobic interactions, and thus replacing it may lead to activity loss. The computational analysis of compound 34B displays that imidazo[1,2-b] pyridazine binds at the hinge region and is involved in key hydrogen bonds with Val135; the aromatic ring of imidazo[1,2-b] pyridazine forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl oxygen of the amide. Methyl morpholines are responsible for the hydrophobic interactions in the ribose binding region. An internal hydrogen bond was observed between the amide NH and the N nitrogen of the imidazo[1,2-b] pyridazine ring system. This computational and biologically active compound may bind at the ATP-n-binding site of GSK-3β (Fig. 22).

Fig. 22. SAR of imidazo[1,2-b]pyridazine (docking image reprinted with permission from ref. 108, the American Chemical Society, Copyright 2023).

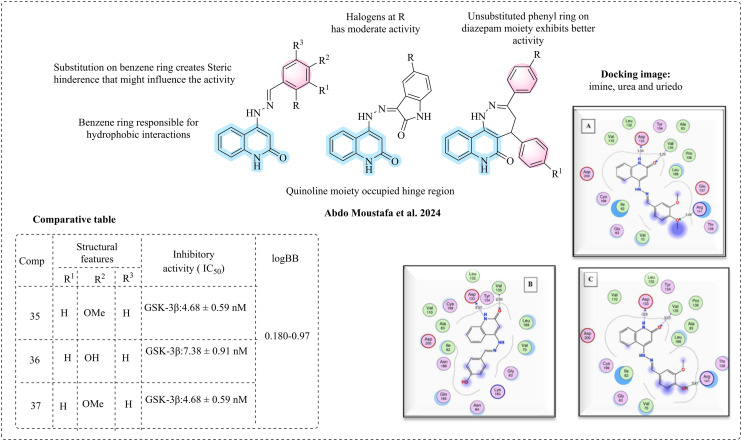

2.11. SAR of quinolines

Abdo Moustafa et al. (2024) developed a new series of compounds comprised of quinolino-2-one, targeting GSK-3β for AD.109 They utilised a pharmacophore-based strategy to develop the novel molecules and evaluated their inhibitory potencies. Computational studies were performed on the most active compounds to support the inhibitory results and gain insights into their binding pattern. The extensive research on quinolines states that quinolines are filled with pharmacophoric features and are suitable for GSK-3β inhibition. The first series of molecules was created by combining quinoline-2-one from the hit molecule (ZINC67773573) with the isatin component from indirubin. The isatin ring was further modified to form a 5-membered pyrrolidine. In the second series, a polar functionality was introduced in place of the isatin ring. In the third series, quinoline was linked with a diazepine heterocyclic moiety, which is known to be CNS active. The designed molecules were synthesised and tested for their inhibitory activity, with staurosporine (IC50 = 6.12 ± 0.74 nM) as a positive control, and 35, 36, and 37 were found to be active. According to the SAR studies, in the first series of molecules, hydrophilic substitution resulted in potent inhibition. At the same time, hydrophobic groups such as trimethoxy at R1, R2, and R3 and dimethoxy at R and R3 resulted in declined activity, which might be due to steric hindrance. The most potent molecule of series 1, having methoxy at R1 and R2 positions, exhibits excellent inhibition against GSK-3β. The second series of molecules had a pyrrolidine ring and was found to be active with Cl or Br moieties. It displayed good inhibition when replaced with 1H-pyrrol-2,5-dione and benzofuran moieties. In the third series of molecules, good inhibition was observed. The unsubstituted phenyl ring on the diazepine ring exhibits better activity than the Cl, Br, and methoxy-substituted ones. The diazepine ring has reported activity on CNS targets. Molecular docking was performed on the most active compounds 35, 36, and 37, which displayed the required interactions, such as quinoline occupying the hinge region, forming a hydrogen bond with Val135 and Asp133. The benzene ring exerts hydrophobic interactions. Phenyl substitutions of imine derivatives occupy the nucleotide-binding loop and interact with Arg141, a guanidine group at the end of the binding site. In silico ADME studies and BBB penetration studies were performed, and most of the compounds display drug likeness and are effective enough to cross the BBB with logBB values of −0.180 to −0.973, while that of the standard is in the range of 0.3 and −1 (Fig. 23).

Fig. 23. SAR of quinolines (docking images reprinted with permission from ref. 109, Elsevier, Copyright 2024).

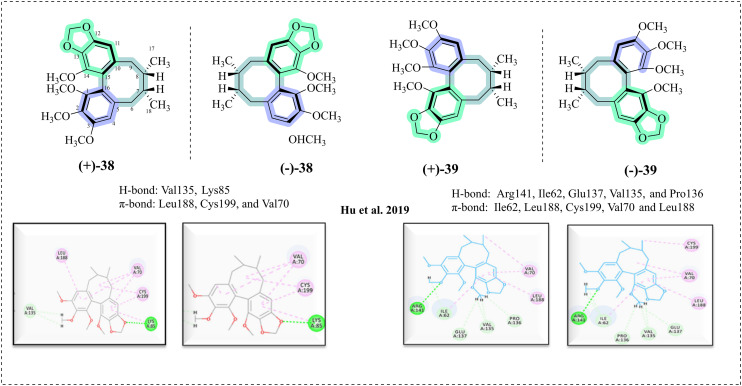

2.12. Natural product derived

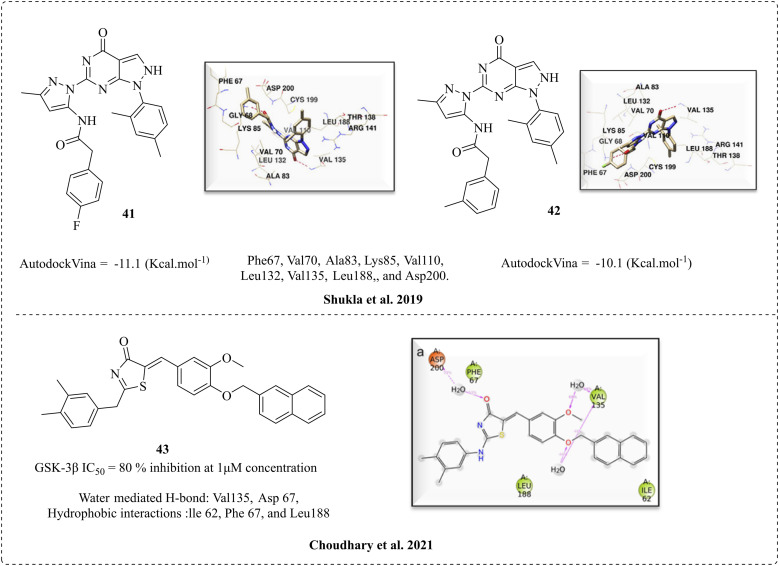

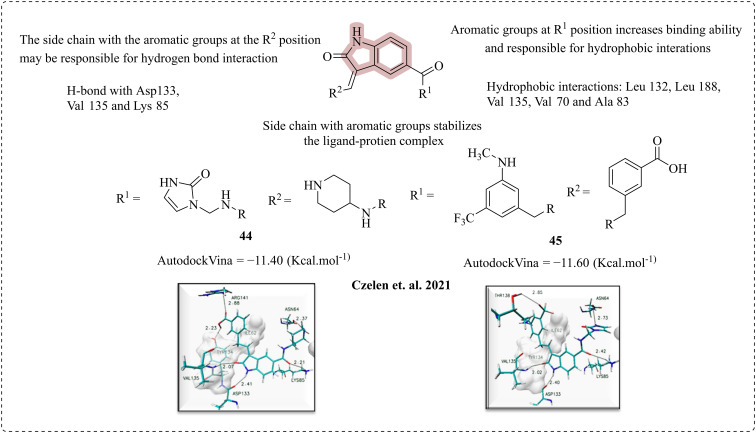

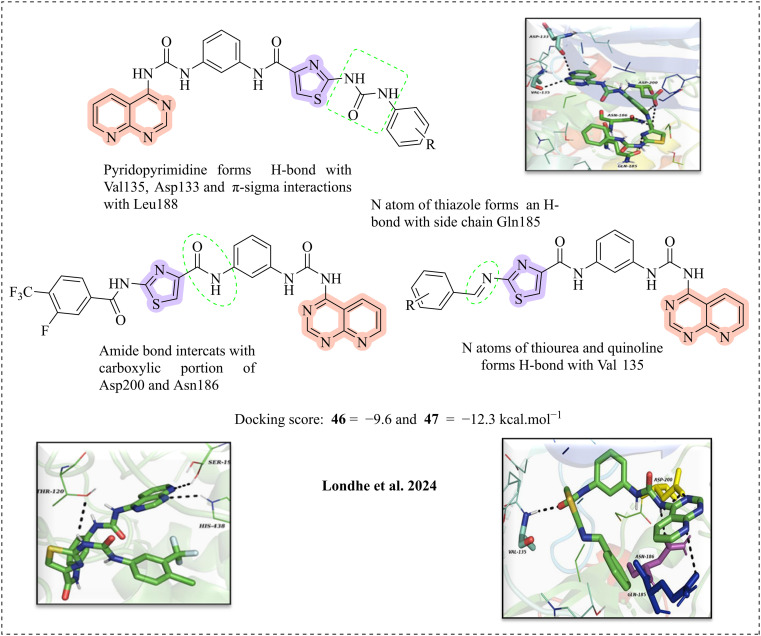

2.12.1. SAR of schisandrin B