Abstract

miRNA-mimicking short hairpin RNAs (shRNAmirs), which depend on the endogenous miRNA biogenesis pathway, have been widely used to investigate gene function and to develop therapeutic strategies due to their stable and robust knockdown of target genes. However, despite the efforts to design potent shRNAmir guide RNAs (gRNAs), relevant biological features beyond the primary sequence have not been fully explored. Here, we present shRNAI, a convolutional neural network model for predicting highly potent shRNAmir gRNAs. Even when trained solely on gRNA sequences, shRNAI outperforms previous algorithms. We further improved the model (shRNAI+) by adding features related to shRNAmir processability and target site context, resulting in superior performance across both public datasets and our own experimental tests. Although shRNAI was initially trained on datasets built with a CNNC motif-free pri-miR-30 backbone, it also displayed improved performance on the CNNC motif. Overall, our study provides a robust framework for designing potent shRNAmir gRNAs, as well as a versatile tool for developing RNAi therapeutics.

Keywords: MT: Bioinformatics, miRNA-mimicking short hairpin RNA, short hairpin RNA, RNA interference, short interfering RNA, microRNA, Drosha, deep learning, convolutional neural network

Graphical abstract

Park and colleagues develop shRNAI+, a deep learning model that integrates target context and processing efficiency to predict potent shRNAmirs. The model outperforms previous tools across diverse datasets and identifies RNAi drug candidates with experimental validation, highlighting its utility in gene silencing and RNAi-based therapeutics.

Introduction

RNAi has been widely used to downregulate target genes in human cells ever since sequence-specific gene silencing was reported in animals.1,2 Short interfering RNAs (siRNAs), short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs),3 and miRNA-mimicking shRNAs (shRNAmirs) have all been developed as RNAi platforms,4 each having distinct advantages and disadvantages. Similar to primary miRNA (pri-miRNA), shRNAmir is processed at a specific position in the basal stem by Drosha in the nucleus,5,6,7,8,9 followed by processing in the apical stem by Dicer in the cytoplasm.10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 A guide RNA (gRNA) derived from the remaining duplex is then loaded onto Argonaute (AGO) to silence its target, a process similar to miRNA-based targeting.23,24,25,26,27,28,29 While miRNA targeting can occur with partial base pairing (positions 2–7 of the 5′-end),30,31,32,33,34 RNAi requires nearly complete base pairing to induce AGO-mediated cleavage.35,36

Whereas siRNA is typically synthesized as a duplex RNA and delivered directly into cells, shRNAmir is expressed through a DNA vector and processed via the endogenous miRNA pathway. Due to its vector-based stable expression and integration into the endogenous processing pathway, shRNAmir is considered a promising tool for controllable gene repression. Although shRNAs have been reported to exhibit greater knockdown (KD) efficiency than siRNAs,37,38,39,40 shRNAmirs have demonstrated improved performance over shRNAs in specific contexts,41 suggesting their potential for higher potency. After Zeng et al. first succeeded in engineering a pri-miR-30-based shRNAmir to selectively repress a target,4 multiple attempts have been made to improve shRNAmir potency by modifying pri-miRNAs, including pri-miR-30 backbones.42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53 Pri-miR-30 and its engineered backbones generally show advantages in Drosha processing efficiency and accuracy.54 However, the original pri-miR-30 backbone was altered to insert an EcoRI site within the CNNC motif (Figure S1A)—a key cis-element in Drosha processing—leading to the later development of the mir-E backbone.55,56

In addition to backbone engineering, algorithms for optimizing gRNA sequences have been introduced to design potent shRNAmirs. Previous algorithms predicted gRNA potency on mir-30/mir-E backbones using shallow machine learning with k-mer-based features.54,57,58 However, because each backbone’s specific sequence and structure can influence shRNAmir processing and targeting, careful selection of optimal gRNA:passenger duplex is necessary.

In this study, we developed shRNAI, a convolutional neural network (CNN) model that accurately predicts the potency of gRNAs embedded in the pri-miR-30 backbone. We compiled large shRNAmir datasets produced via massive parallel assays. The initial shRNAI model surpassed the in vitro and in silico benchmarks of existing algorithms, and by adding processing efficiency and site context information, we further improved the model to shRNAI+. The webserver for shRNAI+ model is freely accessible at http://big2.hanyang.ac.kr/shRNAI.

Results

shRNAI pipeline for selecting potent gRNAs

We developed the shRNAI pipeline to design potent gRNAs, focusing on three key innovations that distinguish it from previous algorithms: (1) the use of large, high-quality training datasets derived from diverse massively parallel reporter assays; (2) the integration of miRNA-related biological features, such as Drosha processing efficiency and target site context; and (3) the adoption of a deep learning framework (CNN) that outperforms traditional machine learning models like support vector machines and linear/logistic regressions used in prior tools. These components are schematically illustrated in Figure 1A and are elaborated upon in the following sections. To build the shRNAI model, we compiled data from previous large-scale pri-miR-30-based shRNAmir studies (Figures 1B, left and S1A; Table S1; dataset sizes: S = 239,844; M = 20,290; T = 18,564; R = 9,804; E = 311; U = 780 after redundancy removal) and performed a systematic comparison by training multiple models on all possible dataset combinations to identify the optimal combination of training datasets (Figures S1B–S1D). Given the differences in dataset size, we subsampled 15,000 training and 2,000 hold-out test data from each of S, T, and M, and trained the model using the 22-nucleotide (nt) gRNA sequences as input features across all possible combinations of training datasets. Model performance was assessed by calculating Spearman correlation coefficients between predicted and observed KD efficiencies on both hold-out and independent test datasets. As the model trained with S + M consistently produced superior performance in both hold-out and independent test sets, these two datasets were selected as the final training datasets for the initial shRNAI model. The remaining mir-30 backbone-based datasets (T and R) and the mir-E backbone-based datasets (E and U) were reserved as independent test datasets (Figure 1B, right).

Figure 1.

A deep learning model was constructed to predict shRNA potency

(A) A schematic illustration of the key points adopted for shRNAI modeling. (B) A schematic illustration of the cloning strategy used in previously generated assay datasets, showing a structural comparison of the mir-30 and the mir-E backbones (left; see Figure S1A for details) and the number of data points used for model training and testing (right). To implement the model, the shERWOOD59 and M158 datasets were randomly divided into training and hold-out test sets. The TILE,55 Ras,60 miR-E,58 and UltramiR59 datasets were used as independent test sets. (C) Performance comparison of shRNAI with other algorithms in a regression task using hold-out and independent test sets. The performance was assessed using Spearman correlation coefficients between model prediction and observed KD efficiencies. Statistical significance was approximated by comparing each of the 100 shRNAI models to the other models and counting the number of cases in which the shRNAI model showed a lower Spearman correlation. This count was used to estimate significance (∗p < 0.01; ns, not significant). (D) An explanation of the Drosha substrate surplus (s). The variable s is calculated by subtracting the Drosha processing rate (pr) from the transcription rate (tr). (E) Performance comparisons of deep learning models trained on the T dataset’s training set and evaluated on its hold-out test set, highlighting the contributions of additional features such as predicted and observed surpluses of Drosha substrates. (F) A performance comparison between the gRNA sequence-only model, the model incorporating gRNA sequence and predicted Drosha substrate surplus, and the model incorporating both the 50-nt target site sequence and surplus information, across hold-out and independent test datasets. Statistical significance was determined by a one-tailed Student’s t test (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (G) Spearman correlation coefficients between predicted and observed KD efficiencies on the Ras dataset under various feature ablation conditions. The full model includes both Drosha substrate surplus feature and native target site context (14-nt flanking sequences on each side of the target site). In ablation settings, Drosha substrate surplus scores were replaced with 0 to remove the effect of Drosha processing feature and/or native flanking sequences were substituted with randomly generated sequences to disrupt contextual structure. Error bars indicate SD. Statistical significance was determined by a one-tailed Student’s t test in (E and F). The whiskers in the boxplots in (E, F, and G) extend to 1.5× the interquartile range. Results are from 100 models trained with the same hyperparameters to illustrate the convergence of the stochastic nature of building deep learning models.

shRNAI, which was trained using 22-nt gRNA sequences from S and M datasets, was benchmarked against current algorithms—SplashRNA,58 DSIR,57 and SeqScore.54 To ensure a fair comparison, we built SplashRNA models with the S + M datasets (SplashRNAS+M) and with the original SplashRNA training datasets (SplashRNAT+Mpos), applying the same parameters as the original publication. The performance of SplashRNAT+Mpos was comparable to that of the original (Figure S1E). In head-to-head comparison, shRNAI consistently outperformed both SplashRNA models on both mir-30 and mir-E backbone datasets, in terms of both correlation and classification metrics (Figures 1C, S1F, and S1G).

Because shRNAmirs utilize endogenous miRNA processing pathway, we hypothesized that their potency is influenced by processing efficiency. Hence, we examined the levels of primary shRNA ([pri-shRNA] also referred to as shRNAmir), precursor shRNA (pre-shRNA), and mature gRNA from the TILE dataset (Figures S2A–S2C). The relative levels of pri-shRNAs not processed into pre-shRNAs showed negative correlation with potency in the three stratified groups, while the relative levels of pre-shRNAs and gRNAs were not correlated. To identify the factors that cause stratified formation, the gRNAs were separated into three groups using two heuristic cutoff criteria (Figure S2D). A comparison of the gRNA groups based on positional attributes revealed that higher AU content in gRNAs was associated with increased pri-shRNA levels, while the nucleotide at the 5′-end strongly affected potency (Figures S2E and S2F), as previously described.55

Given that the transcription rate (tr) for shRNAmir plasmids is similar under same promoter in parallel assay, the primary factor in their abundance is presumably the Drosha processing rate (pr). Hence, we considered the relative level of pri-shRNAs as a Drosha substrate surplus (s = tr – pr) (Figure 1D). In fact, the correlation between the AU content and the observed surplus, s, was reciprocal to that between the AU content and the Drosha cleavage score, as calculated from in vitro Drosha processing data (Figure S2G).61 When we introduced the observed surplus s into the shRNAI model with TILE data, prediction aligned more closely with potency (Figure S3A), indicating that the relative level of pri-shRNA is strongly correlated with Drosha cleavage efficiency. Because the relative level of pri-shRNAs was only available in the TILE dataset, we sought to predict the surplus value using another CNN model (Figures S3B and S3C; see materials and methods for more details). By considering the predicted surplus, , the shRNAI model with TILE dataset was improved to a similar extent as when using the observed value (Figure 1E). The shRNAIS model trained with S + M datasets by adding showed improved performances compared to the original model (Figure 1F).

The sequence contexts of the target sites and their flanking regions have been considered in detecting optimal target sites.62,63 Thus, we examined four mir-30-based datasets (S, T, M, and R) with sufficient data points after filtering for gRNAs with either A or U at the 5′ end and a gRNA AU content of 0.5–0.7 to determine whether the AU content in the flanking region of the target sites affects potency. Regardless of the dataset used, we found that A/U nucleotides in the flanking region of the target site enhanced shRNAmir-mediated KD efficiency (Figure S4A). This observation, in conjunction with the positive correlation between target site accessibility and shRNAmir potency (Figure S4B), suggests that A/U-rich flanking regions may increase local target site accessibility and thereby facilitate more effective silencing. To consider target site context, we included the 14-nt flanking sequences of shRNAmir target site as the additional input features in the final model. The resulting model, shRNAI+, was trained using 50-nt target site sequences (including both the gRNA-complementary region and its flanking context) along with the predicted Drosha substrate surplus. We confirmed consistent model performance with a median Spearman correlation of 0.901, 0.875, and 0.900 in the training, validation, and hold-out test sets, respectively. Similarly, the median values of the area under the precision-recall curve (auPR) were 0.889, 0.872, and 0.883 across these splits, indicating no overfitting and good generalization of the model. This model outperformed both earlier shRNAI models and prior algorithms such as SplashRNA, DSIR, and SeqScore (Figures 1C and 1F; Table S1). Specifically, shRNAI+ demonstrated substantial relative improvements in Spearman correlation compared to the SplashRNAT+Mpos model: 30.3%, −0.04%, 33.5%, and 14.1% for the S, T, M, and R datasets, respectively. When compared to the SplashRNAS+M model, shRNAI+ achieved 2.8%, 14.8%, 17.5%, and 9.8% relative improvements for the same datasets.

To quantify the effect of miRNA-related features on model performance, we evaluated the Ras dataset using randomly generated 14-nt flanking sequences and/or zero values for Drosha surplus predictions (Figure 1G). The results showed that the predicted Drosha surplus feature improved performance by 0.7%–1.0% and the target site context feature improved the performance by 5.1%–5.4%.

Evaluation of shRNAI using publicly available shRNAmir libraries

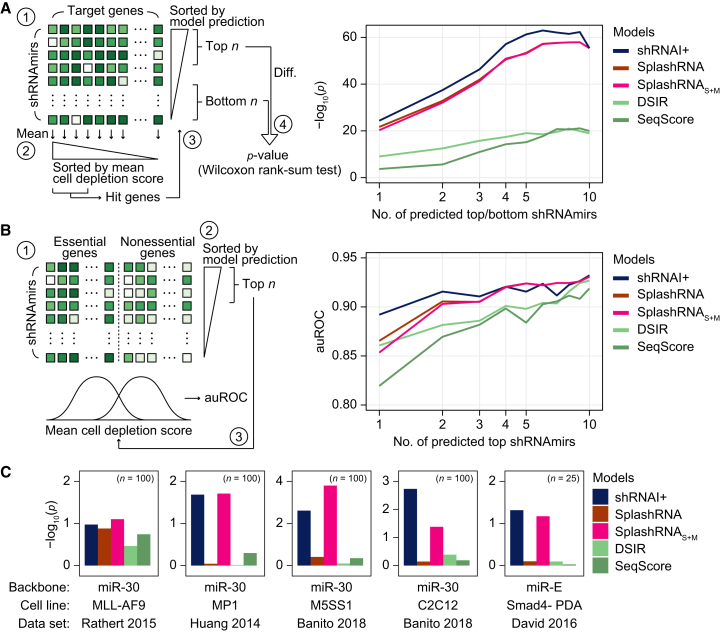

To assess generalizability across diverse contexts beyond the massive parallel reporter assay, we conducted retrospective evaluation using independent, shRNAmir-based large-scale screening datasets (Figure S5A).64 We benchmarked the predictive performance of shRNAI+ and other models (SplashRNA, DSIR, SeqScore) using annotated essential gene sets derived from a dual-screening study that employed both shRNA and CRISPR,65 following the same retrospective ranking strategy used in the SplashRNA study (Figure 2A).58 For each gene, the top n shRNAmirs predicted by each model were ranked and the difference in observed shRNAmir potency between top- and bottom-ranked shRNAmirs was computed. The shRNAI+ model consistently outperformed other tools (n = 1, p < 4.42 × 10−25 for shRNAI+, <2.06 × 10−22 for SplashRNA, <4.95 × 10−21 for SplashRNAS+M, <8.98 × 10−10 for DSIR, <2.03 × 10−4 for SeqScore; n = 2, p < 3.59 × 10−38 for shRNAI+, <1.39 × 10−33 for SplashRNA, <8.36 × 10−33 for SplashRNAS+M, <3.20 × 10−13 for DSIR, <2.35 × 10−6 for SeqScore; n = 3, p < 4.64 × 10−47 for shRNAI+, <1.19 × 10−42 for SplashRNA, <5.45 × 10−42 for SplashRNAS+M, <1.71 × 10−16 for DSIR, <1.09 × 10−11 for SeqScore).

Figure 2.

In silico validation of shRNAI performance

(A) A schematic illustration of retrospective model evaluation (left). First, a matrix containing cell depletion scores (from the original research) for each shRNAmir was assembled. Second, gene-level scores were calculated by averaging the cell depletion scores of all shRNAmirs targeting each gene; genes showing sufficiently negative phenotypes (i.e., essential genes) were selected as hit genes. Third, shRNAmirs against these hit genes were ranked according to each model’s prediction score. Finally, statistical tests were performed to compare the phenotype values between the top n and bottom n shRNAmirs. The right panel shows the performance comparison of shRNAI+ with other models in retrospectively predicting shRNA potency for essential gene sets, with n ranging from 1 to 10. Statistical significance was determined by a one-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (B) A schematic illustration of retrospective model evaluation for essential gene classification (left). First, two matrices containing cell depletion scores for each shRNAmir targeting annotated essential or non-essential genes were obtained from Hart et al.65 Second, shRNAmirs were ranked by their prediction scores from each model. Last, the mean cell depletion score of top n shRNAmirs was used to calculate the auROC scores. The right panel shows the performance comparison of shRNAI+ with other models for detecting gold-standard essential and non-essential genes; auROC was measured for the top n sequences based on the prediction score, with n ranging from 1 to 10. (C) A performance comparison of shRNAI+ and other algorithms in retrospectively predicting shRNA potency in small-scale screening data. Analyses were conducted similarly to (A), with minor modifications. For each dataset, the indicated number of genes (n) was used to compare the performance of different prediction models. Each algorithm selected the top and bottom sequence according to their prediction scores, and their actual cell depletion scores were compared. Statistical significance was determined by a one-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

We further assessed each model’s ability to distinguish essential from non-essential genes using area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (auROC) metrics based on top n shRNAmirs (Figure 2B). shRNAI+ achieved the highest auROC scores up to top three predictions (n = 1, shRNAI+ = 0.892, SplashRNA = 0.865, SplashRNAS+M = 0.853, DSIR = 0.861, SeqScore = 0.819; n = 2, shRNAI+ = 0.916, SplashRNA = 0.906, SplashRNAS+M = 0.903, DSIR = 0.882, SeqScore = 0.870; n = 3, shRNAI+ = 0.911, SplashRNA = 0.905, SplashRNAS+M = 0.905, DSIR = 0.886, SeqScore = 0.882). To validate the performance on external annotations, we applied the same analysis to CRISPR-derived essential gene sets from the DepMap portal (Broad 2024, 24Q4 release; Figure S5P). Although the overall predictive power declined across all models in this context (likely due to mechanistic differences between RNAi- and CRISPR-based gene perturbation), shRNAI+ maintained superior performance (n = 1, auROC: shRNAI+ = 0.762, SplashRNA = 0.748, SplashRNAS+M = 0.748, DSIR = 0.731, SeqScore = 0.714).

In addition, we evaluated model generalizability using five independent small-scale screening datasets (Figures S5B–S5O; Table S2; see materials and methods for more details).66,67,68,69 In each dataset, we compared the experimentally observed potency of shRNAmirs targeting 25 or 100 genes to those predicted as the best and worst by each model. shRNAI+ and SplashRNAS+M significantly distinguished between the best- and worst-performing shRNAmirs in all the datasets tested (Figure 2C; one-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test), supporting the conclusion that the diverse sequence and structural contexts represented in the S and M training datasets contributed to shRNAI+’s improved generalizability.

Overall, shRNAI+ demonstrated superior in silico performance across a wide array of validation datasets and experimental conditions. These results underscore the effectiveness of our training strategy (Figure 1A) and highlight the model’s broad applicability to diverse RNAi design scenarios.

Experimental evaluation of shRNAI+

To determine which model more accurately reflects individual shRNAmir potency in endogenous contexts rather than in screening or reporter systems, we experimentally tested selected shRNAmirs in cell lines and compared their observed KD efficiencies with model predictions. This included six genes previously used in SplashRNA validation (PTEN, BAP1, NF2, AXIN1, PBRM1, and RELA) and an additional target gene, UPF1. For each gene, >10 shRNAmirs were selected from prediction spaces where shRNAI+ and SplashRNA differed most in predicted efficacy (Figure 3A). Constructs were cloned into mir-E-based lentiviral vectors and transduced into HeLa cells at MOI 0.6. After selection, KD efficiency was assessed by quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) (Table S3). We conducted two experimental rounds with different doxycycline durations to evaluate both saturated (72 h) and unsaturated (48 h) KD conditions (Figures 3B–3D; Figure S6). In this analysis, we also included the original SplashRNA scores (SplashRNAweb) calculated using the SplashRNA web server to enable a fair comparison. The overall correlation coefficients between shRNAI+ predictions and observed KD efficiencies were 0.495 and 0.345 for the saturated and unsaturated conditions, respectively. These values were consistently higher than those of other models (SplashRNA: 0.068/0.051, SplashRNAweb: 0.095/0.019, SplashRNAS+M: 0.344/0.286, DSIR: 0.233/0.027, and SeqScore: 0.326/0.125 for saturated/unsaturated conditions, respectively). These results indicate stronger predictive alignment of shRNAI+ with observed KD outcomes. Notably, the comparable performance of SplashRNAS+M reinforces the significance of our dataset selection strategy (Figures 3C and 3D).

Figure 3.

Experimental validation of shRNAI performance

(A) Schematic of the experimental validation process. shRNAmirs were selected from regions in the prediction space showing divergence between shRNAI+ and SplashRNA scores (1–4 in inset). Selected constructs were cloned into an mir-E-based lentiviral vector (LT3GEPIR), transduced into HeLa cells at MOI 0.6, and selected with puromycin. KD efficiency was assessed by RT-qPCR. (B) Knockdown prediction accuracy under the saturated condition (72 h doxycycline) across the models: shRNAI+, SplashRNA, SplashRNAS+M, DSIR, and SeqScore using shRNAmirs. Each dot represents the mean RT-qPCR KD (%) across three replicates. Genes are color coded as indicated. (C, D) Spearman correlation coefficients between model predictions and experimentally measured KD values across all tested genes, under saturated (C) and unsaturated (D) conditions. (F) Distribution of 80th percentile values from 10,000 bootstrapping iterations based on the result of experimental validation with saturated condition. In each iteration, 10 data points were resampled from six bins of the original data. The x axis indicates the bins, and the y axis indicates the 80th percentile value in each bin.

Next, to define a practical threshold for identifying highly potent shRNAmirs, we performed a bootstrapping analysis using experimentally measured KD data under saturated conditions (Figure 3E). This analysis revealed that shRNAI+ scores above 0.6 correspond to a median KD efficiency of ∼80%. Based on this, we used a cutoff of 0.6 for downstream analysis.

The shRNAI+ model provides better siRNA-based drug candidates

Since shRNAI+ predicts the potency of gRNAs loaded onto the shRNAmir backbone, we next tested whether our model could also be applied to siRNAs using a large siRNA dataset.70 The correlation results between the predicted and observed siRNA KD efficiency indicated that our shRNAI models retain predictive power for siRNA potency, despite having never been trained on siRNA data (Figure S7A; shRNAI models: Pearson r > 0.418, p < 1.6 × 10−97; siRNA-based models: r > 0.642, p < 4.1 × 10−266). Although their performance is inferior to that of established siRNA-specific tools, this result suggests that shRNAI captures meaningful features relevant to RNAi efficacy.

Since several siRNA-based drugs targeting TTR, PCSK9, HAO1, and ALAS1 for treating rare metabolic diseases have recently been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA),71,72,73,74,75 we tried to identify potentially better gRNAs for these target genes using the shRNAI+ model. Our model detected better target sites and corresponding gRNAs with potentially greater potency than those of the FDA-approved siRNA drugs, vutrisiran, patisiran, inclisiran, lumasiran, and givosiran (Figures 4A and S7B).

Figure 4.

Proposed RNAi-based drug candidates using shRNAmirs

(A) A scatterplot showing the predicted shRNA potency for tiled sequence in the common CDS of TTR, PCSK9, and ALAS1 gene. The x axis represents the position, while the y axis represents the shRNAI+ score. The shRNAmirs used in our validation were indicated with their own colors, and the target sites of FDA-approved siRNA drugs were indicated with those names. (B) RNA-level knockdown efficiencies for three genes (ALAS1, PCSK9, and TTR) plotted against model predictions: ALAS1 (red), PCSK9 (green), and TTR (blue). (C) Spearman correlation between predicted and observed RNA-level KD efficiencies across models. (D) Spearman correlation between model predictions and observed KD at the protein level. (E) mRNA responses following transduction with TTR_1 (left) or TTR_4 (right), comparing mRNAs that contain a canonical miRNA target site for AGO-loadable RNAs, including gRNA, isogRNA, pRNA, and the two most highly expressed endogenous miRNAs, with mRNAs bearing a canonical miRNA target site of 10 dinucleotide shuffled sequences. Shown are mean log fold changes (LFC) in mRNA expression relative to negative-control shRNA-transduced cells. A one-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to compare site-containing distributions and random site distributions.

To validate the shRNAI+ model predictions, we designed shRNAmirs targeting against three sites in the TTR gene with scores above 0.6. We then evaluated their KD efficiencies in Huh7 cells, which were compared to the two target sites of the FDA-approved siRNA drugs. One of our top-predicted shRNAmirs (TTR_1) achieved ∼75% KD at the RNA level, which is comparable to the performance of FDA-approved siRNA TTR_4 (vutrisiran) and TTR_8 (patisiran) that achieved 72% and 70% KD, respectively (Figure 4B; Table S4). To directly compare KD performance at the siRNA level, we also designed four siRNAs (siTTR_1, siTTR_1m, siTTR_4, and siTTR_4m) based on TTR_1 and TTR_4, with and without chemical modifications adapted from vutrisiran. siTTR_4m matched the sequence and modifications of vutrisiran, excluding GalNAc conjugation. All siRNAs exhibited over 90% KD of TTR mRNA in Huh7 cells without significant differences (Figure S7C; Table S5), supporting the model’s utility for RNAi drug design. We next asked if the biogenesis of TTR_1 gRNA contributed to higher KD efficiency. To this end, we assessed the steady-state expression levels of the gRNA and passenger strand (pRNA) of TTR_1 and observed that the levels were similar or slightly lower compared to that of TTR_4, while the premature shRNA level of TTR_1 was somewhat higher compared to that of TTR_4 (Figures S7G–S7I). The results suggested that TTR_1 gRNA achieved effective KD, even though the biogenesis was not particularly more efficient than TTR_4.

We expanded our validation to include two additional targets of FDA-approved siRNAs; ALAS1 and PCSK9. For each gene, we designed five shRNAmir sequences that spanned divergent predictions between shRNAI+ and SplashRNA. KD efficiencies were evaluated via both RT-qPCR and western blot (Figure 4B; Figures S7D–S7F; Table S4). shRNAI+ showed superior predictive performance at the RNA and protein levels, with Spearman correlation coefficients of 0.80 and 0.69, respectively (Figures 4C and 4D). In contrast, SplashRNA yielded 0.65/0.54, DSIR yielded 0.52/0.32, and SeqScore yielded 0.61/0.23. These results demonstrate that shRNAI+ robustly predicts potent target sites for gene silencing, including in drug discovery settings.

To further investigate the potential off-target effects of these shRNAmirs, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) on cells transfected with our top-scoring (TTR_1) and the vutrisiran-based (TTR_4) shRNAmirs (depicted in Figure 4B). We specifically examined changes in mRNAs with miRNA-like target sites that could be off-targeted by shRNAmirs. These included gRNAs, isogRNAs (which shift by 1 nt at the 5′ end due to alternative processing), and pRNAs (Figure 4E, top). We also checked for stoichiometric effects arising from competition with endogenous miRNAs, particularly focusing on the two most expressed endogenous miRNAs (let-7i-5p and miR-21-5p). We observed minimal off-targeting and stoichiometric effects for TTR_1. In contrast, TTR_4 exhibited off-target effects mediated by its gRNA, isogRNA, and pRNA (Figure 4E). To investigate the basis of these differences, we quantified the expression levels of premature shRNAs (including both pri- and pre-shRNA forms), gRNAs, and pRNAs, indicating less-efficient shRNAmir maturation of TTR_1 (Figures S7G–S7I; Table S6). This is consistent with its higher predicted Drosha substrate surplus ( = 0.768 for TTR_1 and 0.702 for TTR_4). Notably, despite only modest differences in gRNA levels, off-target effects were observed exclusively for TTR_4. This suggests that its elevated off-target activity likely arises from more than just miRNA-like base-pairing potential (i.e., seed complementarity to 3′ UTRs); it also arises from the excessive accumulation of mature shRNAs due to more efficient maturation.

Discussion

Our goal was to develop a generalizable and interpretable shRNAmir potency predictor that surpasses existing tools across multiple datasets and assay formats. To this end, we implemented a high-performance deep learning model, shRNAI+, and demonstrated its superior performance through systematic benchmarking, including experimental validation and retrospective screening analysis. The improved model was generated by including shRNAmir processing efficiency as well as the context of the target sites and flanking regions. We found that sites with shRNAI+ scores 0.6 tended to have a median KD efficiency 80% (Figure 3E). Moreover, for over 80% of human and mouse genes, the shRNAI+ model can predict at least one shRNAmir with KD 80%, and for more than 60% of genes, it can predict at least five (Figure S8). This indicates the model’s broad applicability and high potency.

While our shRNAI models demonstrate strong predictive performance across diverse datasets, several limitations should be noted. First, the model was trained entirely on in vitro data and its performance has not yet been validated in vivo, where additional biological complexity and delivery constraints may influence efficacy. Second, the training data were derived primarily from sensor assays using specific shRNAmir backbones (e.g., miR-30 and miR-E), which may introduce bias and limit generalizability to other backbone designs or assay systems. Third, although the model integrates miRNA-related features such as Drosha processing efficiency and target site context, it does not account for cell-type-specific factors, including mRNA accessibility, RNA-binding protein interactions, or differences in endogenous processing machinery. Last, the model currently lacks the ability to predict or control for off-target effects, which are critical for ensuring specificity in RNAi-based applications. These limitations highlight areas for future refinement and experimental validation.

The abundance of pri-shRNA is primarily influenced by its production and Drosha processing rates. In previous shRNA screening studies55,58,59,60,64,66,67,68,69; however, all shRNAmirs were transcribed from the same promoter in the expression vectors or viruses, leading to a linear relationship between their expression levels and their potency (Figure S2A). Within this framework, Drosha processing, which initiates shRNAmir maturation, plays a critical role in determining shRNAmir functionality. This underlines the significance of this step in the overall process.

shRNA potency is directly affected by the abundance of gRNAs and is subsequently shaped by additional factors, including pre-shRNA export, Dicer processing, AGO loading of gRNAs, and target-directed miRNA decay.76,77,78,79,80,81 These insights suggest that further improvements may be achieved by better modeling in vivo Drosha/Dicer processing efficiency, pre-shRNA export, and AGO loading efficiency.

Additionally, current shRNA prediction models (SplashRNA and shRNAI) rely solely on mir-30-based datasets, limiting their application to mir-30-based shRNAmirs. Because microprocessing strongly depends on pri-miRNA sequence and structure, large-scale datasets for other pri-miRNA backbones are needed for generalizing deep learning models to a broader range of miRNA-based shRNAmirs. Designing a large-scale synthetic shRNAmir experiment—where levels of shRNAmirs, pre-shRNAs, and shRNAs with fully randomized backbone, along with the corresponding target-level changes, are measured simultaneously—could not only strengthen predictive power but also catalyze new generative AI models for optimized artificial backbones.

siRNAs have been explored as potential therapeutic agents, leading to the approval of several siRNA-based drugs by the FDA.71,72,73,74,75 Despite the advantages of shRNAmirs over siRNAs or shRNAs, the development of shRNAmir-based drugs has been hampered by the lack of efficient shRNAmir design tools. shRNAmirs have a superior ability to silence targets due to their vector-based sustained expression and assimilation into endogenous miRNA processing pathway,37,38,39 as well as low off-target effects (Figure 4E). Overall, shRNAmirs offer a promising therapeutic platform, and our shRNAI models presented here have the potential to make a significant contribution to the field.

Materials and methods

Public data sources

Gene annotation data (GENCODE v41 and vM30) for human and mouse genes were downloaded from the GENCODE database (https://www.gencodegenes.org/) to train the shRNAI models and to calculate shRNAI scores. In vitro Drosha processing data were downloaded from the NCBI, the Short Read Archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/; SRA051323).

Training and evaluation datasets

For training and testing of the shRNAI models, shRNA potency and shRNAmir processing data were collected from previous papers and the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; GSE62183).55,58,59,60 These datasets were originally generated using a sensor assay system, as described in Fellmann et al.55 In this system, each shRNAmir is embedded in a dual-fluorescent reporter construct, where the target is fused to a fluorescent marker (e.g., GFP) and co-expressed with a second normalization marker (e.g., RFP). The relative change in fluorescence between the two markers reflects the potency of each shRNA in repressing its target. This system enables quantitative, high-throughput measurement of shRNAmir activity across thousands of constructs in a pooled format. Approximately 300,000 combined data points were compiled from six large-scale studies: shERWOOD (S), TILE (T), M1 (M), Ras (R), miR-E (E), and UltramiR (U) (Figure 1B, right).

Redundant entries, defined as identical 22-nt gRNA sequences with multiple measurements, were removed prior to model training to prevent data leakage and reduce potential overfitting. To harmonize the scale of potency values across datasets, we applied min-max normalization to the output labels, scaling all potency values to a [0, 1] range. This normalization accounted for differences in measurement scales and enabled integration of heterogeneous datasets into a single predictive model. After normalization, datasets were merged to construct the training set. Specifically, the two largest datasets, S and M, were selected as the training sources. Each was randomly split into training and hold-out subsets (e.g., 200,000 from S and 18,000 from M for training; remaining data for hold-out testing). The other datasets (T, R, E, and U) were reserved as independent test sets. All input sequences (e.g., 22-nt gRNA) were encoded using standard one-hot encoding. We did not perform any additional feature alignment across datasets. Instead, we intentionally exposed the model to the inherent variability between datasets during training to promote robustness to inter-dataset shifts and enhance generalizability.

To benchmark the massive parallel assay data using a classification framework, we followed the criteria reported in the original SplashRNA study. For all datasets except M1, shRNAmirs were binarized based on defined activity thresholds: shERWOOD: 0, TILE: −3, Ras: 3, miR-E: 80, and UltramiR: −0.5. For the M1 dataset, shRNAmirs were classified using a Gaussian mixture model: scores > −2 were labeled as positive and scores < −3.5 as negative. Classification performance was evaluated using the auPR across all possible thresholds. For further evaluation, additional shRNA screening datasets were gathered from previous studies.64,66,67,68,69

Building shRNAI models

Architecture

shRNAI is based on a CNN with three convolutional layers (Figure S1B).82,83,84 Input gRNA sequences of length 22 nts are one-hot encoded into four-by-n. We tuned the number of convolutional layers by balancing model complexity with validation performance. Batch-normalization and exponential linear unit (ELU) activations follow each convolution.85,86 The number of convolution filters is [64, 128, 256], and the column sizes are [3, 5, 7], with the row size fixed at 1, except in the first convolution layer (set to 4 to cover all 4 nts). A max pooling layer (filter size 2, stride 2) is placed between the first and second convolution layers. The final layer’s output is averaged and then fed into two fully connected layers of [64, 128] ELU units with batch normalization. For shRNAI+, we expanded the model input to include the 50-nt target site sequence, consistent with the original massively parallel sensor assay design, which comprises the 22-nt shRNAmir target site and 14-nt endogenous flanking sequences on either side. Additionally, the model incorporated predicted Drosha substrate surplus as a scalar feature, integrated at the final convolutional layer. A linear output layer produced the final predicted potency score.

Training

We trained the network using Adam optimizer to minimize the mean-square error (Figure 1A, right box) in Keras with a TensorFlow backend.87,88 Training continued for up to 50 epochs, with early stopping after six consecutive epochs without improvement in validation loss. The initial learning rate (0.001) was reduced by a factor of 0.1 after three non-improving epochs.

For each dataset (e.g., shERWOOD), after reserving a fixed hold-out test set (e.g., 39,844), 10% of the remaining data (e.g., 20,000 of 200,000) were set aside as a validation set for model selection and the remaining 90% (e.g., 180,000) were used for 5-fold cross-validation to optimize hyperparameters. Hyperparameters (filter width and number of filters in convolution layers and neurons in fully connected layers) were determined through 5-fold cross-validation on 80% (e.g., 144,000) of the training data; the remaining 20% (e.g., 36,000) within each fold was used for validation.

Prediction model for Drosha substrate surplus

Because the pri-shRNA abundance is influenced by Drosha processing efficiency, we built another CNN to predict the “Drosha substrate surplus” (Figures S3B and S3C). The input was constructed by concatenating two consecutive sequences. One sequence ranged from 27 nt upstream to 29 nt downstream of the 5′ Drosha cleavage site, and the other sequence ranged from 31 nt upstream to 25 nt downstream of the 3′ Drosha cleavage site. Then, the reverse sequence of the latter was added to the former sequence. After one-hot encoding, an eight-by-n matrix was constructed and base-pair information was added as an extra row, resulting in a nine-by-n matrix. We used three convolutional layers with batch normalization and rectified linear unit (RELU) activation.89 The number of convolution filters is [128, 256, 512] and the column sizes are [3, 5, 7], with the row size fixed at 1, except in the first convolution layer (set to 9 to cover all 9 nts). A max pooling layer (filter of size 2, stride 2) is placed between the first and second layers. The final layer’s output is averaged and then fed into two fully connected layers of [64, 128] RELU units with batch normalization. A linear output layer produced the final Drosha substrate surplus. Training was performed similarly to the shRNAI model.

Calculation of target site accessibility

Prediction of structural accessibility was performed by appending each target site with its flanking variable 14-nt and constant 5-nt sequences and folding the entire 60-nt sequence using RNAplfold,90 with the parameters –L and –W both set to 60 and –u set to 22. From the resulting output matrix, we extracted the probability that all positions across the 22-nt shRNAmir target site were unpaired.

Testing shRNAI on screening data

Only shRNAs with target sites present in the gene annotation data were retained. If fewer than 14 nts of flanking sequence were available, random nucleotides were appended.

Large-scale screening dataset

A large-scale dataset with an mir-E-like backbone from a previous study was collected to benchmark our model (Figure S5A).64 The phenotypes of each shRNA and each gene were calculated as previously published.58 The phenotypes for each shRNA were calculated as the mean log2-fold change for the two replicates. To test the retrospective prediction power of the algorithms, the observed phenotypes of shRNAmirs between the top and bottom predictions were compared using previously annotated essential genes. To test the prediction accuracy of the algorithms, gene-level scores that were calculated from the mean phenotypes for the top predictions were compared to identify essential or non-essential genes. The dataset included ∼25 shRNAs per candidate target gene, although there were some redundancies between the sub-libraries.

Small-scale screening dataset

Data generated (1) with more than 100 target genes for a robust comparison and (2) with the negative selection method were collected to benchmark our model. The Rathert 2015 dataset included 2,917 mir-30-based shRNAmirs without the CNNC motif to identify chromatin factors that prevent resistance to the bromodomain in acute myeloid leukemia (Figures S5B–S5D).66 The Huang 2014 dataset included 2,245 mir-30-based shRNAmirs without the CNNC motif targeting 442 known druggable target genes in MP1 cell lines (Figures S5E–S5G).67 The Banito 2018 dataset included ∼2,400 CNNC motif-free mir-30-based shRNAmirs targeting 400 chromatin regulators to identify key regulators involved in sustaining synovial sarcoma cell transformation (Figures S5H–S5L).68 The David 2016 dataset included 558 mir-E backbone shRNAmirs targeting 93 transcription factors (Figures S5M–S5O).69 All the datasets were preprocessed via the same method. The phenotypes of each shRNA were calculated as the mean log2-fold change for all replicates after normalization to the total reads of each replicate. Gene-level scores were calculated as the mean phenotypes for all tested shRNAs of each gene. For the evaluation of the algorithms, the observed phenotypes of the top and bottom predictions were compared in the most negative subset of tested genes.

Retrospective analysis

To evaluate model performance using published functional screening datasets, we conducted retrospective benchmarking using cell depletion scores from prior pooled shRNAmir viability screens. For the shRNA potency evaluation (Figure 2A), we first constructed a matrix containing cell depletion scores for each shRNAmir, as reported in the original studies. Gene-level depletion scores were then computed by averaging all shRNAmir depletion values targeting the same gene. Genes showing sufficiently negative depletion scores (indicating essentiality) were selected as hit genes. For each model, shRNAmir targeting these hit genes were ranked by their predicted potency, and a one-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum test was performed to assess whether the top n shRNAmirs (n = 1 to 10) exhibited significantly stronger depletion than the bottom n. For the essential gene classification evaluation (Figure 2B), annotated essential and non-essential genes were used to generate two separated matrices of depletion scores. For each model, shRNAmirs were ranked by predicted potency, and the top n sequences were used to calculate the auROC, comparing the distributions of depletion scores between the two gene categories. Performance was evaluated across a range of n values (1–10).

Cell culture and lentivirus production

A HEK293T cell line, a HeLa cell line, and an Huh7 cell line were cultured at 90% confluence in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were treated with 0.05% trypsin (Welgene, Korea) and subcultured at a 1:10 ratio. For lentiviral production, HEK293T cells were seeded in 100-mm dishes (Nunc, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at a density of 3 × 105 cells/well and transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. HEK293T cells were transfected with 1.3 pmol of psPAX2 (Addgene #12260), 1.72 pmol of pMD2.G (Addgene # 12259), and 1.64 pmol of the transfer plasmid for each shRNA expression vector. The transfected cells were then cultured for 72 h, after which virus preparation was performed.

Lentiviral transduction, siRNA transfection, and quantification of RNAi efficiency

HeLa and Huh7 cells were seeded in 12-well plates (NUNC, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at a density of 0.8 × 105 cells/well and transduced with 10 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The infected cells were cultured for 72 h, followed by puromycin (1 μg/mL) (Gendipo, Korea) selection for 72 h. To more comprehensively assess shRNA efficiency, two conditions were used. Condition 1: After infection for 72 h, puromycin (1 μg/mL) (Gendipo, Korea) selection was performed for 72 h, followed by doxycycline (1 μg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) treatment for 6 days. Condition 2: After infection for 72 h, puromycin (1 μg/mL) and doxycycline (1 μg/mL) both were added for 72 h, following by an additional 2-day treatment of doxycycline (1 μg/mL). To transfect the TTR-targeted siRNA, Huh7 cells were seeded in 24-well plates (Nunc, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well. TTR-targeted siRNA (20 nM) was transfected into Huh7 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and incubated for 2 days post-transfection. Total RNA was extracted using the easy-spin total RNA extraction kit (Intron, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). RNA expression levels were analyzed by RT-qPCR using THUNDERBIRD Next SYBR qPCR Mix (TOYOBO, Japan).

Western blot

Cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS) (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) supplemented with 100X protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The lysates were incubated on ice for 10 min and then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected, and the protein concentration was determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Equal amounts of protein (10 μg [ALAS1, PCSK9], 30 μg [TTR]) were resolved on 4%–12% gradient SDS-PAGE gels (Bio-Rad, USA) and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, USA) using a transfer system. Protein loading was additionally normalized based on GAPDH band intensity. The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk (BD Difco, USA) in TBST (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 137 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) (Bio-Rad, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C with the appropriate first antibody (Abcam, [ALAS1: ab154860, PCSK9: ab181142, TTR: ab75815]) diluted in 5% milk in TBST (1:1,000) [ALAS1, PCSK9], (1:500) [TTR]. After washing three times with TBST, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Abcam, UK, ab150077) for 1 h at room temperature. Following additional washes, the protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagent (Bio-Rad, USA) and imaged using an Amersham Imager 680 (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, Sweden). Band intensity was quantified using ImageJ software. Background intensity was measured from areas adjacent to each band and subtracted to remove non-specific background noise. The resulting net intensities were used to normalize protein expression levels to the loading control (GAPDH).

RNA sequencing processing for off-target analysis

To isolate mRNA from 1 μg of total RNA, we utilized the NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module. Subsequently, the isolated mRNA was employed to construct RNA-seq libraries following the manufacturer’s instructions provided with the NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina. Indexing was accomplished using NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (Dual Index Primers Set 1). The libraries underwent quality assessment, which included quantifying concentration using a Qubit fluorometer (ThermoFisher Scientific) and determining library size with a TapeStation 2200 (Agilent). Following library preparation, RNA-seq was performed utilizing the NovaSeq (Illumina) platform. RNA-seq data were processed to remove adapter sequences from reads using Cutadapt (version 2.10, parameter: -m 25).91 Filtered reads were mapped to the GRCH38 genome, and gene expression were quantified using RSEM (version 1.3.1, parameter: --star) with GENCODE v38 gene annotation.92 Fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads (FPKM) values were quantile normalized and genes with >1 FPKM in both the negative control and shRNAmir-transfected samples were analyzed further.

RT-qPCR of premature shRNA, guide RNA, and passenger RNA

Huh7 cells were seeded in 6-well plates (Nunc, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells/well and transduced with TTR_1 and TTR_4 expression vectors with 10 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The infected cells were cultured for 72 h in the presence of doxycycline (1 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The expression levels of TTR_1 and TTR_4 premature shRNA were quantified by RT-qPCR using THUNDERBIRD Next SYBR qPCR Mix (TOYOBO, Japan) on cDNA generated from total RNA by random hexamer. The premature shRNA expression levels were internally normalized to GAPDH expression levels. The gRNA and pRNA levels were assessed by RT-qPCR on cDNA generated by stem-loop RT primer. cDNAs synthesized from total RNA using the stem-loop RT primers contain sequences of gRNA and passenger RNA with extended primer-binding sites that allow for analyses by qPCR. The expression levels of TTR_1 and TTR_4 gRNA and passenger RNA were internally normalized by miR26a-5p expression levels. The amplicon sized from the RT-qPCR of pre-shRNA or processed gRNA or passenger RNAs were also analyzed by TapeStation Systems (Agilent) for further validation.

Data availability

The raw RNA-seq data following shRNAmirs (TTR_1 and TTR_4) treatments have been deposited in the Korea Sequence Read Archive (KRA) in Korea Bioinformation Center, Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KAP230669), and are publicly accessible at https://kbds.re.kr/KRA. All the Python code for running shRNAI models is available in the GitHub repository (https://github.com/ParkSJ-91/shRNAI). The webserver for the shRNAI+ model is available at http://big2.hanyang.ac.kr/shRNAI.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the Bioinformatics and Genomics (BIG) laboratory for their helpful comments. We also thank the HY-IBB computing facility for providing the computing resources needed for our analyses. This work was supported by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program and Basic Research Program of the National Research Foundation funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (grant numbers RS-2023-NR076663 and RS-2021-NR056589 to J.K.H. and 2021R1A2C3005835 and RS-2023-00207840 to J.-W.N.). This research was also supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute, funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI22C063600). This research was also supported by Korea Basic Science Institute (National Research Facilities and Equipment Center) grant funded by the Ministry of Education (2023R1A6C101A009 to S.P., J.-W.N., and J.K.H.).

Author contributions

S.P. performed all computational analyses and developed the code. S.-H.P. conducted all experimental validations and related analyses. J.-S.O. and Y.-K.N. contributed to validating dataset integration for model training. S.H. supported RT-qPCR and western blot experiments. K.W.B. conducted experiments related to shRNA biogenesis. S.P., S.-H.P., J.-S.O., Y.-K.N., J.K.H., and J.-W.N. designed the study and co-wrote the manuscript. J.-W.N. and J.K.H. supervised the project. The original concept was conceived by J.-W.N. and S.P.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT in order to improve text flow and clarity. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2025.102738.

Contributor Information

Junho K. Hur, Email: juhur@hanyang.ac.kr.

Jin-Wu Nam, Email: jwnam@hanyang.ac.kr.

Supplemental information

Each dataset’s total number of data points is shown, along with the number of positive and negative points defined by the thresholds originally used in SplashRNA. These same thresholds were applied for evaluating the classification performance of shRNAI.

The number of total target genes and shRNAs used in each dataset is listed, along with a brief description of the experiments, including the cell lines and the type of selection performed.

The knockdown efficiencies of the tested shRNAs are shown in triplicate.

The knockdown efficiencies of the tested shRNAs are shown in triplicate.

References

- 1.Fire A., Xu S., Montgomery M.K., Kostas S.A., Driver S.E., Mello C.C. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zamore P.D., Tuschl T., Sharp P.A., Bartel D.P. RNAi: double-stranded RNA directs the ATP-dependent cleavage of mRNA at 21 to 23 nucleotide intervals. Cell. 2000;101:25–33. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80620-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brummelkamp T.R., Bernards R., Agami R. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science. 2002;296:550–553. doi: 10.1126/science.1068999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeng Y., Wagner E.J., Cullen B.R. Both natural and designed micro RNAs can inhibit the expression of cognate mRNAs when expressed in human cells. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:1327–1333. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han J., Lee Y., Yeom K.H., Nam J.W., Heo I., Rhee J.K., Sohn S.Y., Cho Y., Zhang B.T., Kim V.N. Molecular basis for the recognition of primary microRNAs by the Drosha-DGCR8 complex. Cell. 2006;125:887–901. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma H., Wu Y., Choi J.G., Wu H. Lower and upper stem-single-stranded RNA junctions together determine the Drosha cleavage site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:20687–20692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311639110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeng Y., Yi R., Cullen B.R. Recognition and cleavage of primary microRNA precursors by the nuclear processing enzyme Drosha. EMBO J. 2005;24:138–148. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roden C., Gaillard J., Kanoria S., Rennie W., Barish S., Cheng J., Pan W., Liu J., Cotsapas C., Ding Y., Lu J. Novel determinants of mammalian primary microRNA processing revealed by systematic evaluation of hairpin-containing transcripts and human genetic variation. Genome Res. 2017;27:374–384. doi: 10.1101/gr.208900.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon S.C., Baek S.C., Choi Y.G., Yang J., Lee Y.S., Woo J.S., Kim V.N. Molecular Basis for the Single-Nucleotide Precision of Primary microRNA Processing. Mol. Cell. 2019;73:505–518.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernstein E., Caudy A.A., Hammond S.M., Hannon G.J. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature. 2001;409:363–366. doi: 10.1038/35053110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grishok A., Pasquinelli A.E., Conte D., Li N., Parrish S., Ha I., Baillie D.L., Fire A., Ruvkun G., Mello C.C. Genes and mechanisms related to RNA interference regulate expression of the small temporal RNAs that control C. elegans developmental timing. Cell. 2001;106:23–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00431-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hutvagner G., McLachlan J., Pasquinelli A.E., Bálint E., Tuschl T., Zamore P.D. A cellular function for the RNA-interference enzyme Dicer in the maturation of the let-7 small temporal RNA. Science. 2001;293:834–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1062961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ketting R.F., Fischer S.E., Bernstein E., Sijen T., Hannon G.J., Plasterk R.H. Dicer functions in RNA interference and in synthesis of small RNA involved in developmental timing in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2654–2659. doi: 10.1101/gad.927801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee H.Y., Doudna J.A. TRBP alters human precursor microRNA processing in vitro. RNA. 2012;18:2012–2019. doi: 10.1261/rna.035501.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee H.Y., Zhou K., Smith A.M., Noland C.L., Doudna J.A. Differential roles of human Dicer-binding proteins TRBP and PACT in small RNA processing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:6568–6576. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson R.C., Tambe A., Kidwell M.A., Noland C.L., Schneider C.P., Doudna J.A. Dicer-TRBP complex formation ensures accurate mammalian microRNA biogenesis. Mol. Cell. 2015;57:397–407. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macrae I.J., Zhou K., Li F., Repic A., Brooks A.N., Cande W.Z., Adams P.D., Doudna J.A. Structural basis for double-stranded RNA processing by Dicer. Science. 2006;311:195–198. doi: 10.1126/science.1121638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacRae I.J., Zhou K., Doudna J.A. Structural determinants of RNA recognition and cleavage by Dicer. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:934–940. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park J.E., Heo I., Tian Y., Simanshu D.K., Chang H., Jee D., Patel D.J., Kim V.N. Dicer recognizes the 5' end of RNA for efficient and accurate processing. Nature. 2011;475:201–205. doi: 10.1038/nature10198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu S., Jin L., Zhang Y., Huang Y., Zhang F., Valdmanis P.N., Kay M.A. The loop position of shRNAs and pre-miRNAs is critical for the accuracy of dicer processing in vivo. Cell. 2012;151:900–911. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang H., Kolb F.A., Brondani V., Billy E., Filipowicz W. Human Dicer preferentially cleaves dsRNAs at their termini without a requirement for ATP. EMBO J. 2002;21:5875–5885. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang H., Kolb F.A., Jaskiewicz L., Westhof E., Filipowicz W. Single processing center models for human Dicer and bacterial RNase III. Cell. 2004;118:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mourelatos Z., Dostie J., Paushkin S., Sharma A., Charroux B., Abel L., Rappsilber J., Mann M., Dreyfuss G. miRNPs: a novel class of ribonucleoproteins containing numerous microRNAs. Genes Dev. 2002;16:720–728. doi: 10.1101/gad.974702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobayashi H., Tomari Y. RISC assembly: Coordination between small RNAs and Argonaute proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1859:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khvorova A., Reynolds A., Jayasena S.D. Functional siRNAs and miRNAs exhibit strand bias. Cell. 2003;115:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00801-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwarz D.S., Hutvágner G., Du T., Xu Z., Aronin N., Zamore P.D. Asymmetry in the assembly of the RNAi enzyme complex. Cell. 2003;115:199–208. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00759-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frank F., Sonenberg N., Nagar B. Structural basis for 5'-nucleotide base-specific recognition of guide RNA by human AGO2. Nature. 2010;465:818–822. doi: 10.1038/nature09039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki H.I., Katsura A., Yasuda T., Ueno T., Mano H., Sugimoto K., Miyazono K. Small-RNA asymmetry is directly driven by mammalian Argonautes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015;22:512–521. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim H., Kim J., Kim K., Chang H., You K., Kim V.N. Bias-minimized quantification of microRNA reveals widespread alternative processing and 3' end modification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:2630–2640. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ding L., Spencer A., Morita K., Han M. The developmental timing regulator AIN-1 interacts with miRISCs and may target the argonaute protein ALG-1 to cytoplasmic P bodies in C. elegans. Mol. Cell. 2005;19:437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rehwinkel J., Behm-Ansmant I., Gatfield D., Izaurralde E. A crucial role for GW182 and the DCP1:DCP2 decapping complex in miRNA-mediated gene silencing. RNA. 2005;11:1640–1647. doi: 10.1261/rna.2191905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jonas S., Izaurralde E. Towards a molecular understanding of microRNA-mediated gene silencing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015;16:421–433. doi: 10.1038/nrg3965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen C.Y.A., Shyu A.B. Mechanisms of deadenylation-dependent decay. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2011;2:167–183. doi: 10.1002/wrna.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park J., Seo J.W., Ahn N., Park S., Hwang J., Nam J.W. UPF1/SMG7-dependent microRNA-mediated gene regulation. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:4181. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12123-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu J., Carmell M.A., Rivas F.V., Marsden C.G., Thomson J.M., Song J.J., Hammond S.M., Joshua-Tor L., Hannon G.J. Argonaute2 is the catalytic engine of mammalian RNAi. Science. 2004;305:1437–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.1102513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meister G., Landthaler M., Patkaniowska A., Dorsett Y., Teng G., Tuschl T. Human Argonaute2 mediates RNA cleavage targeted by miRNAs and siRNAs. Mol. Cell. 2004;15:185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McAnuff M.A., Rettig G.R., Rice K.G. Potency of siRNA versus shRNA mediated knockdown in vivo. J. Pharm. Sci. 2007;96:2922–2930. doi: 10.1002/jps.20968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siolas D., Lerner C., Burchard J., Ge W., Linsley P.S., Paddison P.J., Hannon G.J., Cleary M.A. Synthetic shRNAs as potent RNAi triggers. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:227–231. doi: 10.1038/nbt1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vlassov A.V., Korba B., Farrar K., Mukerjee S., Seyhan A.A., Ilves H., Kaspar R.L., Leake D., Kazakov S.A., Johnston B.H. shRNAs targeting hepatitis C: effects of sequence and structural features, and comparision with siRNA. Oligonucleotides. 2007;17:223–236. doi: 10.1089/oli.2006.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohrt T., Merkle D., Birkenfeld K., Echeverri C.J., Schwille P. In situ fluorescence analysis demonstrates active siRNA exclusion from the nucleus by Exportin 5. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1369–1380. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silva J.M., Li M.Z., Chang K., Ge W., Golding M.C., Rickles R.J., Siolas D., Hu G., Paddison P.J., Schlabach M.R., et al. Second-generation shRNA libraries covering the mouse and human genomes. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:1281–1288. doi: 10.1038/ng1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chung K.H., Hart C.C., Al-Bassam S., Avery A., Taylor J., Patel P.D., Vojtek A.B., Turner D.L. Polycistronic RNA polymerase II expression vectors for RNA interference based on BIC/miR-155. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e53. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ely A., Naidoo T., Arbuthnot P. Efficient silencing of gene expression with modular trimeric Pol II expression cassettes comprising microRNA shuttles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fowler D.K., Williams C., Gerritsen A.T., Washbourne P. Improved knockdown from artificial microRNAs in an enhanced miR-155 backbone: a designer's guide to potent multi-target RNAi. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:e48. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guda S., Brendel C., Renella R., Du P., Bauer D.E., Canver M.C., Grenier J.K., Grimson A.W., Kamran S.C., Thornton J., et al. miRNA-embedded shRNAs for Lineage-specific BCL11A Knockdown and Hemoglobin F Induction. Mol. Ther. 2015;23:1465–1474. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watanabe C., Cuellar T.L., Haley B. Quantitative evaluation of first, second, and third generation hairpin systems reveals the limit of mammalian vector-based RNAi. RNA Biol. 2016;13:25–33. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2015.1128062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xie J., Tai P.W.L., Brown A., Gong S., Zhu S., Wang Y., Li C., Colpan C., Su Q., He R., et al. Effective and Accurate Gene Silencing by a Recombinant AAV-Compatible MicroRNA Scaffold. Mol. Ther. 2020;28:422–430. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ely A., Naidoo T., Mufamadi S., Crowther C., Arbuthnot P. Expressed anti-HBV primary microRNA shuttles inhibit viral replication efficiently in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:1105–1112. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yue J., Sheng Y., Ren A., Penmatsa S. A miR-21 hairpin structure-based gene knockdown vector. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;394:667–672. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen S.C.Y., Stern P., Guo Z., Chen J. Expression of multiple artificial microRNAs from a chicken miRNA126-based lentiviral vector. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walder R.Y., Gautam M., Wilson S.P., Benson C.J., Sluka K.A. Selective targeting of ASIC3 using artificial miRNAs inhibits primary and secondary hyperalgesia after muscle inflammation. Pain. 2011;152:2348–2356. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang X., Jia Z. Construction of HCC-targeting artificial miRNAs using natural miRNA precursors. Exp. Ther. Med. 2013;6:209–215. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miniarikova J., Zimmer V., Martier R., Brouwers C.C., Pythoud C., Richetin K., Rey M., Lubelski J., Evers M.M., van Deventer S.J., et al. AAV5-miHTT gene therapy demonstrates suppression of mutant huntingtin aggregation and neuronal dysfunction in a rat model of Huntington's disease. Gene Ther. 2017;24:630–639. doi: 10.1038/gt.2017.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kampmann M., Horlbeck M.A., Chen Y., Tsai J.C., Bassik M.C., Gilbert L.A., Villalta J.E., Kwon S.C., Chang H., Kim V.N., Weissman J.S. Next-generation libraries for robust RNA interference-based genome-wide screens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E3384–E3391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508821112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fellmann C., Zuber J., McJunkin K., Chang K., Malone C.D., Dickins R.A., Xu Q., Hengartner M.O., Elledge S.J., Hannon G.J., Lowe S.W. Functional identification of optimized RNAi triggers using a massively parallel sensor assay. Mol. Cell. 2011;41:733–746. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fellmann C., Hoffmann T., Sridhar V., Hopfgartner B., Muhar M., Roth M., Lai D.Y., Barbosa I.A.M., Kwon J.S., Guan Y., et al. An optimized microRNA backbone for effective single-copy RNAi. Cell Rep. 2013;5:1704–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vert J.P., Foveau N., Lajaunie C., Vandenbrouck Y. An accurate and interpretable model for siRNA efficacy prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:520. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pelossof R., Fairchild L., Huang C.H., Widmer C., Sreedharan V.T., Sinha N., Lai D.Y., Guan Y., Premsrirut P.K., Tschaharganeh D.F., et al. Prediction of potent shRNAs with a sequential classification algorithm. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017;35:350–353. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Knott S.R.V., Maceli A., Erard N., Chang K., Marran K., Zhou X., Gordon A., Demerdash O.E., Wagenblast E., Kim S., et al. A computational algorithm to predict shRNA potency. Mol. Cell. 2014;56:796–807. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yuan T.L., Fellmann C., Lee C.S., Ritchie C.D., Thapar V., Lee L.C., Hsu D.J., Grace D., Carver J.O., Zuber J., et al. Development of siRNA payloads to target KRAS-mutant cancer. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:1182–1197. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fang W., Bartel D.P. The Menu of Features that Define Primary MicroRNAs and Enable De Novo Design of MicroRNA Genes. Mol. Cell. 2015;60:131–145. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McGeary S.E., Lin K.S., Shi C.Y., Pham T.M., Bisaria N., Kelley G.M., Bartel D.P. The biochemical basis of microRNA targeting efficacy. Science. 2019;366 doi: 10.1126/science.aav1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tafer H., Ameres S.L., Obernosterer G., Gebeshuber C.A., Schroeder R., Martinez J., Hofacker I.L. The impact of target site accessibility on the design of effective siRNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:578–583. doi: 10.1038/nbt1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morgens D.W., Deans R.M., Li A., Bassik M.C. Systematic comparison of CRISPR/Cas9 and RNAi screens for essential genes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:634–636. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hart T., Brown K.R., Sircoulomb F., Rottapel R., Moffat J. Measuring error rates in genomic perturbation screens: gold standards for human functional genomics. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2014;10:733. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rathert P., Roth M., Neumann T., Muerdter F., Roe J.S., Muhar M., Deswal S., Cerny-Reiterer S., Peter B., Jude J., et al. Transcriptional plasticity promotes primary and acquired resistance to BET inhibition. Nature. 2015;525:543–547. doi: 10.1038/nature14898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huang C.H., Lujambio A., Zuber J., Tschaharganeh D.F., Doran M.G., Evans M.J., Kitzing T., Zhu N., de Stanchina E., Sawyers C.L., et al. CDK9-mediated transcription elongation is required for MYC addiction in hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes Dev. 2014;28:1800–1814. doi: 10.1101/gad.244368.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Banito A., Li X., Laporte A.N., Roe J.S., Sanchez-Vega F., Huang C.H., Dancsok A.R., Hatzi K., Chen C.C., Tschaharganeh D.F., et al. The SS18-SSX Oncoprotein Hijacks KDM2B-PRC1.1 to Drive Synovial Sarcoma. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:527–541.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.David C.J., Huang Y.H., Chen M., Su J., Zou Y., Bardeesy N., Iacobuzio-Donahue C.A., Massagué J. TGF-beta Tumor Suppression through a Lethal EMT. Cell. 2016;164:1015–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huesken D., Lange J., Mickanin C., Weiler J., Asselbergs F., Warner J., Meloon B., Engel S., Rosenberg A., Cohen D., et al. Design of a genome-wide siRNA library using an artificial neural network. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:995–1001. doi: 10.1038/nbt1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mullard A. FDA approves fifth RNAi drug - Alnylam's next-gen hATTR treatment. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022;21:548–549. doi: 10.1038/d41573-022-00118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scott L.J. Givosiran: First Approval. Drugs. 2020;80:335–339. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Scott L.J., Keam S.J. Lumasiran: First Approval. Drugs. 2021;81:277–282. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01463-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kristen A.V., Ajroud-Driss S., Conceição I., Gorevic P., Kyriakides T., Obici L. Patisiran, an RNAi therapeutic for the treatment of hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2019;9:5–23. doi: 10.2217/nmt-2018-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ray K.K., Wright R.S., Kallend D., Koenig W., Leiter L.A., Raal F.J., Bisch J.A., Richardson T., Jaros M., Wijngaard P.L.J., et al. Two Phase 3 Trials of Inclisiran in Patients with Elevated LDL Cholesterol. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1507–1519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1912387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shi C.Y., Kingston E.R., Kleaveland B., Lin D.H., Stubna M.W., Bartel D.P. The ZSWIM8 ubiquitin ligase mediates target-directed microRNA degradation. Science. 2020;370 doi: 10.1126/science.abc9359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cazalla D., Yario T., Steitz J.A. Down-regulation of a host microRNA by a Herpesvirus saimiri noncoding RNA. Science. 2010;328:1563–1566. doi: 10.1126/science.1187197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Libri V., Helwak A., Miesen P., Santhakumar D., Borger J.G., Kudla G., Grey F., Tollervey D., Buck A.H. Murine cytomegalovirus encodes a miR-27 inhibitor disguised as a target. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:279–284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114204109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marcinowski L., Tanguy M., Krmpotic A., Rädle B., Lisnić V.J., Tuddenham L., Chane-Woon-Ming B., Ruzsics Z., Erhard F., Benkartek C., et al. Degradation of cellular mir-27 by a novel, highly abundant viral transcript is important for efficient virus replication in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee S., Song J., Kim S., Kim J., Hong Y., Kim Y., Kim D., Baek D., Ahn K. Selective degradation of host MicroRNAs by an intergenic HCMV noncoding RNA accelerates virus production. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:678–690. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Han J., LaVigne C.A., Jones B.T., Zhang H., Gillett F., Mendell J.T. A ubiquitin ligase mediates target-directed microRNA decay independently of tailing and trimming. Science. 2020;370 doi: 10.1126/science.abc9546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fukushima K. Neocognitron: a self organizing neural network model for a mechanism of pattern recognition unaffected by shift in position. Biol. Cybern. 1980;36:193–202. doi: 10.1007/BF00344251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Waibel A., Hanazawa T., Hinton G., Shikano K., Lang K.J. Phoneme Recognition Using Time-Delay Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Acoust. 1989;37:328–339. doi: 10.1109/29.21701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bottou L., Fogelman-Soulié F., Blanchet P., Lienard J.S. Experiments with time delay networks and dynamic time warping for speaker independent isolated digit recognition. Proc. Eurospeech. 1989;89:537–540. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ioffe S., Szegedy C. Batch normalization: accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. Proc. ICML. 2015;37:448–456. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Clevert D.-A., Unterthiner T., Hochreiter S. Fast and accurate deep network learning by exponential linear units (ELUs) arXiv. 2015 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1511.07289. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chollet F. Keras. 2015. https://keras.io

- 88.Abadi M., Agarwal A., Barham P., Brevdo E., Chen Z., Citro C., Corrado G.S., Davis A., Dean J., Devin M., et al. Tensorflow: Large-scale machine learning on heterogeneous distributed systems. arXiv. 2016 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1603.04467. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hahnloser R.H., Sarpeshkar R., Mahowald M.A., Douglas R.J., Seung H.S. Digital selection and analogue amplification coexist in a cortex-inspired silicon circuit. Nature. 2000;405:947–951. doi: 10.1038/35016072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bernhart S.H., Hofacker I.L., Stadler P.F. Local RNA base pairing probabilities in large sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:614–615. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btk014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]