Abstract

Isoliquiritigenin (ISLT), a bioactive and typical chalcones ingredient isolated from the root of licorice, has shown various pharmacological properties, including antitumor, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities. It is extensively utilized in the management of tumors, diabetes mellitus, dermatological disorders, and other therapeutic applications. Although ISLT has been globally recognized for its health benefits, its oral administration is still restricted by sparing water solubility, poor bioavailability, and slow dissolution in the intestine. For topical application, deficiencies include poor transdermal absorption and low skin permeability. Therefore, optimizing drug delivery systems and improving its bioavailability are considered a productive platform to solve these challenges of ISLT, but detailed strategies have not yet been systematically organized. This review first comprehensively summarizes the pharmacological activities, inherent mechanisms and therapeutic potentials of ISLT. Next, it describes programs to improve permeability and bioavailability in oral and transdermal drug delivery, such as nanocomposites, nanoemulsions, cyclodextrin complexes, and exosomes, as well as the use of chemical permeation enhancers. The applications of multiple administration routes and different formulations for enhanced bioavailability are exclusively compared. Additionally, new solutions such as ISLT derivatives and exosomes were proposed, aiming to address the limitations of ISLT and providing new ideas for its further application. In summary, this review offers comprehensive reference and theoretical support for the optimization and enhancement of the bioavailability for other natural flavonoid ingredients.

Keywords: isoliquiritigenin, drug delivery systems, transdermal delivery, bioavailability, pharmacological activities, oral delivery

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) plays a pivotal role in the research and development of disease treatment.1 ISLT is one of the bioactive and typical flavonoid components isolated from the roots of Glycyrrhiza uralensis, Glycyrrhiza inflate or Glycyrrhiza glabra, which possesses numerous pharmacological effects, includin+g antitumor, anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, antioxidant, immunomodulatory, hepatoprotective, and cardioprotective properties, demonstrating great potential value in clinical treatment. Currently, oral ISLT plays a significant role in the treatment of cancers (including melanoma, gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, lung cancer, breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, etc), diabetes mellitus, and psoriasis.2 However, poor aqueous solubility, low bioavailability, non-specific targeting and short half-life in vivo bring about a formidable challenge for its oral delivery. At present, self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system, gel beads, inclusion complexes have emerged as effective technologies to enhance the solubility and stability of drugs and promote the ability to penetrate barriers, thereby improving oral bioavailability, achieving targeted drug delivery and intelligent release. Moreover, numerous reports have highlighted that transdermal drug delivery systems effectively address some of the limitations of oral ISLT therapy, which enables the transport of drugs or macromolecules through the skin into the bloodstream at a controlled rate, resulting in systemic or local therapeutic effects.3,4 This route circumvents first-pass hepatic metabolism and gastrointestinal digestion, minimize plasma drug concentration fluctuations, reduce toxic side effects, achieve less frequent dosing schedules, and improve patient compliance. Therefore, it enhances the therapeutic efficiency and maintains a stable plasma level of the drug.5 At present, topical application of ISLT has been utilized in the treatment of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, as well as in inhibiting the occurrence and development of melanoma. The transdermal delivery system confers ISLT with significant advantages for both local and systemic therapeutic effects. However, stratum corneum (SC) is a primary barrier to the penetration of ISLT. Moreover, ISLT exhibits low aqueous solubility and high lipophilicity, which is unfavorable for their transdermal transport.6 Consequently, numerous contemporary studies are centered on improving the transdermal efficiency of ISLT through chemical penetration enhancers (CPE), nanostructured lipid carries (NLC), and hydrogels.7,8 CPE possesses the advantages of being easy to apply, highly compatible, non-invasive, and cost-effective compared to ultrasound, lasers, and microneedles.9,10 NLC could remarkably elevate the drug solubility in solid and liquid lipid matrices, exhibiting a high encapsulation rate. It enhances the drug permeability across the skin by reducing the tight packing of lipids in the stratum corneum. Notably, it also improves the stability of the formulation (PDI < 0.3).11,12 Additionally, NLC gels displayed reduced transdermal flux, longer sustained release time and lower cytotoxicity compared to NLC dispersions.7,13–15 Hydrogels harbor excellent biocompatibility, self-adhesion and antimicrobial properties, which can efficiently release drugs, and have fast response and high sensitivity motion perception,16,17 which is suitable for transdermal drug delivery and motion monitoring.18

In this work, we first summarized the pharmacological activities, mechanisms of action, current therapeutic outcomes, and applications of ISLT. Subsequently, this review provides critical insights and references into the molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways underlying ISLT’s therapeutic effects against malignancies (particularly melanoma) and dermatological disorders. The therapeutic advantages in oncology were systematically evaluated. Furthermore, delineates strategic approaches were concluded to enhance oral bioavailability and transdermal permeability of ISLT. It offers solutions to address issues such as sparing solubility, poor bioavailability, and low permeability associated with oral and transdermal administration of ISLT. It further examines synergistic applications of dual-route administration (oral/topical). Lastly, It conducts comparative analyses of different formulation technologies, appraising their respective merits and limitations in disease-specific contexts.

Pharmacological Activities and Mechanisms of Action of Oral ISLT

Anti-Tumor Activities and Pathways of ISLT

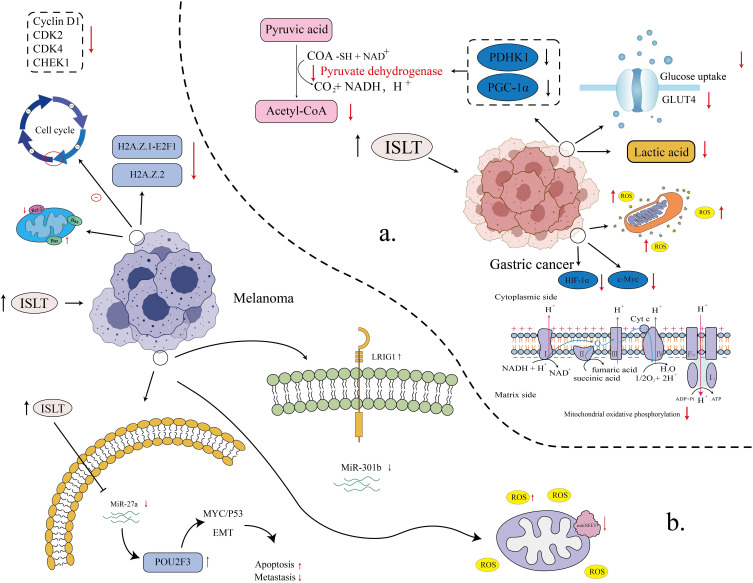

ISLT exhibits direct inhibitory effects on melanoma, breast cancer, gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer and other cancers. ISLT exert anti-carcinogenic effects by inducing cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, autophagy and anti-angiogenesis, thereby suppressing tumorigenesis, proliferation, migration, and malignant progression (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The flow diagram displaying the ISLT pharmacological activities and limitations.

Gastric Cancer (GC)

According to the 2025 Cancer Statistics, there are significant racial disparities in GC incidence and mortality in the United States. Overall, the incidence of GC is 17.7 cases per 100,000 in men and 12.5 cases per 100,000 in women.19 American Indians and Alaska Natives had the highest rates, 13.4 cases per 100,000 men and 10.0 cases per 100,000 women, respectively. African Americans also have higher GC mortality rates, 6.6 per 100,000 men and 3.3 per 100,000 women. Of note, the incidence of GC has gradually decreased since 1998 but remains high in some groups, especially smokers and obese people. In addition, the incidence of GC in young people has increased, suggesting that early screening and prevention measures need to be strengthened.20 Aberrant energy metabolism drives tumorigenesis and enhances chemoresistance in malignant neoplasms.21,22 Yu et al found that ISLT (MGC803 cells: 40 μM, SGC7901 cells: 50 µM) downregulated the expression of glucose transporter four and reduced the uptake of glucose by GC cells. It also demonstrated that it suppressed the activity of lactate dehydrogenase and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 and reduced the production of glycolytic products. Moreover, it downregulated peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha expression. It impaired mitochondrial function while simultaneously suppressing glycolysis and inhibiting mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, ultimately leading to energy metabolic collapse in GC cells. In addition, it decreased the Bcl-2/Bax ratio and upregulated cleaved caspase-3/caspase-9 to promote GC cell apoptosis. Meanwhile, experiments showed that the expression of cellular-myelocytomatosis viral oncogene and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α was downregulated to regulate the energy metabolism and proliferative activity of GC cells. Taken together, ISLT exerts its anti-gastric cancer effects through multiple mechanisms, including inhibiting glucose uptake, blocking glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, inducing energy metabolism collapse, regulating the expression of apoptosis-related proteins, and suppressing the expression of key transcription factors. These combined actions collectively contribute to its therapeutic efficacy against gastric cancer.23 The main mechanism of ISLT against gastric cancer is shown in Figure 2a.

Figure 2.

The signaling pathways and action mechanisms of the anti-gastric cancer and anti-melanoma effects of ISLT (a) Different mechanisms of ISLT inhibition in gastric cancer cells (the main pathways include regulation of glucose metabolism, cell cycle, and influence of key metabolic enzymes and proteins); (b) The multifunctional role of ISLT in anti-melanoma (mainly by inhibiting cell proliferation, inducing apoptosis, influencing cell cycle and participating in key steps of tumor metastasis).

Li et al’s research focused on another pathway: stemness inhibition and tumor microenvironment regulation in GC. Glucose-related protein 78 (GRP78) is a key regulator of the unfolded protein response that is expressed only on the surface of cancer cells and is associated with tumor cell proliferation, survival, and chemotherapy resistance.24 Studies have shown that ISLT (25 μg/mL) significantly suppressed the expression of GRP78 in GC cells MKN45, thereby inhibiting the stem-cell-like properties of GC cells. Meanwhile, ISLT released the expression of surface markers (LGR5, CD24, CD44) and transcription factors (SOX2, Nanog) related to GC stem cells. Additionally, ISLT reduced GRP78 expression to lower the secretion of transforming tumor growth factor-β1 in GC cells, thereby suppressing the activation of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and impairing the expression of α-SMA and matrix metallopeptidase-9 in CAFs, which ultimately modulated the tumor microenvironment. Therefore, ISLT exert anti-gastric cancer effects by attenuating GRP78 and inhibiting cancer stemness-mediated chemoresistance in the tumor microenvironment.25 ISLT-17 is an analogue of ISLT. Among the 18 ISLT analogs synthesized by Huang et al, ISLT-17 (20 or 40 μM) displayed the most vigorous anti-gastric cancer activity. It was capable of repressing the growth of two different GC cell lines (SGC-7901 and BGC-823 cells). Through regulating the expression of Cdc2 and Cyclin B1, it achieved cell cycle arrest in GC cells in the G2/M phase. Concurrently, ISLT-17 can upregulate the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins (Cleaved-PARP, Bax) and downregulate the expression of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 to induce apoptosis in GC cells. Furthermore, ISLT-17 increases the production of Reactive oxygen species (ROS) in GC cells, thereby inhibiting cell growth. It also induced autophagy in GC cells by governing the expression of autophagy-related proteins such as LC3B II, p62 and Beclin1. Collectively, ISLT-17, a novel ISLT analog, exhibits compelling anti-gastric cancer efficacy through multimodal mechanisms.26

Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC)

In the past decades, the incidence and mortality of pancreatic cancer have increased by approximately 0.3% per year, which is closely associated with public health problems such as population aging, obesity and diabetes. Pancreatic cancer is projected to become the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States by 2025, with a significant increase in incidence particularly among those older than 50 years of age. In addition, incidence and mortality rates remain higher among men and African Americans.27–29 Autophagy plays a dual role in PDAC. It acts both as a positive effector that promotes the survival of tumor-initiating cells and as a negative effector that increases the toxicity of uncontrolled expansion cytotoxicity.30 On the one hand, in Zhang et al’s experiments, it demonstrated that ISLT (12.5 and 25 μM) lead to excessive accumulation of autophagosomes by blocking the late stage of autophagic flux and help to induce PDAC cell death by changing autophagy from protective to destructive. This conclusion can be confirmed by silencing siAgt5 to rescue the apoptosis of tumor cells administered with ISLT. On the other hand, ISLT directly targets p38 MAPK signaling to induce apoptosis, especially by targeting p38 MAPKs to make PDAC cells more sensitive to the cytotoxic effects of drugs that can induce autophagy.31 Another study demonstrated that ISLT reduced the growth of pancreatic cancer cells by inhibiting autophagy and increasing the level of ROS in PDAC cells, consequently triggering the apoptosis pathway. Simultaneously, ISLT exhibits specific antioxidant activity mitigating oxidative stress-induced damage to normal cells, while enhancing cytotoxic effects on cancer cells to some extent. In addition, ISLT enhances anticancer effects by modulating immune cells in the tumor microenvironment.32

Breast Tumor

Overall, 5-year relative survival for cancer increased from 49% in 1975–1977 to 69% in 2014–2020, and treatment for breast cancer also improved.33–35 Breast cancer incidence and cure rates show positive trends in 2025, but significant socioeconomic disparities remain. PD-L1 is an important immune checkpoint and is mainly expressed in tumor cells.36–38 The study by Yuan et al revealed that ISLT exerts anti-breast cancer effects by simultaneously blocking both the ERK and Src signaling pathways, thereby reducing PD-L1 levels and enhancing T cell-mediated tumor cell killing.39 3′,4′,5′,4″-tetramethoxychalcone (TMC) is an ISLT derivative. Peng et al discovered that TMC significantly inhibited the proliferation of two triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells (MDA-MB-231, BT549). It can induce apoptosis in TNBC cells by upregulating the pro-apoptotic protein Bax and downregulating the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2. In addition, TMC (20 mg/kg/d and 40 mg/kg/d) was able to dose-dependently inhibit the expression of miR-374a in a variety of cancers. TMC promotes apoptosis in TNBC cells by downregulating miR-374a, which in turn upregulates the expression of the pro-apoptotic protein BAX.40

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC)

In the past three decades, the mortality rate of lung cancer patients in China has increased by 464.84%, about 100,000 people die of lung cancer every year. It is estimated that the number of new cases of lung cancer was 1.8 million in 2012, accounting for 13% of all cancer cases in the world. The incidence of NSCLC, including squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma and large cell carcinoma, is the highest, accounting for 85%.41 A large number of experimental studies have demonstrated that N6-methyladenosine (m6A) regulates the occurrence and progression of a variety of tumors,42–44 including NSCLC. In human NSCLC cells, the knockout of the Twist1 gene can inhibit tumor growth and induce apoptosis. The downregulation of IGF2BP3 induced by ISLT (6.25, 12.5, 25 μM) inhibited both the initiation and progression of NSCLC caused by IGF2BP3 overexpression in the study by Cui et al. In addition, IGF2BP3 has a direct targeted regulatory effect on Twist1, IGF2BP3 can enhance the mRNA stability of TWIST1 through m6A-dependent mode to reduce the progression of NSCLC. Therefore, ISLT can lower the stability of TWIST 1 mRNA by down-regulating IGF2BP3. In summary, ISLT with TWIST 1 knockout significantly inhibit NSCLC.45

Antioxidant Activity of ISLT

Antioxidants can effectively prevent cell damage and reduce the occurrence of chronic diseases. Antioxidants contribute to the prevention of various diseases such as cardiovascular disease and cancer by inhibiting oxidative stress caused by free radicals. Furthermore, in food science, antioxidants possess a key role in inhibiting the generation of trans-fatty acids in cooking oils.46 Excess reactive oxygen species are closely related to the occurrence of neuronal damage or death in various neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and cognitive impairment.47–49 The overall age-standardized prevalence of diabetes in China in 2023 was 13.7%, with 233 million people. Without intervention, the prevalence would reach 16.15% in 2030, 21.52% in 2040 and 29.10% in 2050. Effective obesity control could reduce the prevalence to less than 15% in 2050.50 The antioxidant activity of ISLT plays an important role in treating neuronal damage, diabetes, renal protection, cardiovascular protection, etc. Nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is pivotal in regulating the expression of numerous antioxidant genes. ISLT possesses therapeutic effects on various diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and kidney diseases by activating the Nrf2 pathway.51 Liu et al demonstrated that ISLT (5, 10, 20 μM) exerts cerebroprotective effects against subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH)-induced oxidative damage by modulating Nrf2-mediated antioxidant signaling via partial activation of sirtuin 1.52 Wang et al found that ISLT (10 or 30 mg/kg) significantly preserved renal function and structure in patients with diabetic kidney disease, inhibited oxidative stress and reduced ROS levels, and suppressed the activation of NF-kappa B and NLRP3 inflammasomes and the occurrence of pyroptosis, which played a renal protective role in diabetes-induced kidney injury.53 Additionally, ISLT (20, 40, and 80μg/mL) alleviates excessive oxidative stress, downregulates the expression of renal fibrosis and inflammation-related factors, and inhibits the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway, thereby exerting a protective effect against acute kidney injury.54 According to Yao et al, ISLT (5, 25, and 50 μmol/L) significantly attenuated the production of reactive oxygen species in mouse cardiomyocytes triggered by hypoxia/reoxygenation, decreased the expression of malondialdehyde and the activity of lactate dehydrogenase, enhanced the activity of superoxide dismutase and catalase, and increased the expression of Nrf2 and its downstream heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1). As a result, it attenuated oxidative stress damage and the barbed wire caused by ischemia and reperfusion, thus reducing myocardial injury.55

Anti-Inflammatory Activity of ISLT

The anti-inflammatory activity of ISLT is primarily applied to antiviral-mediated inflammation, brain injury, fatty liver disease, etc. In Wang et al’s experiments, it demonstrated that ISLT (10, 12.5, 25 and 50 μM) can act as an NRF2 agonist, activating NRF2 signaling to exert anti-inflammatory effects.56 ISLT (20 mg/kg) alleviates tissue damage provoked after traumatic brain injury by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/GSK-3 β/NF-kappa B signaling pathway.57 The anti-inflammatory activity of ISLT (375 mg/kg) is also reflected on its capability to reduce inflammation and metabolic disorders in adipose tissue by altering the intestinal microbiota.58 In the study of Hu et al, it was found that spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) is a critical molecule at the ISLT (10 or 50 mg/kg) docking site in macrophages. ISLT downregulates the inflammatory activity of macrophages by targeting Syk, thereby inhibiting the activation of macrophage inflammasomes. This mechanism alleviates methionine- and choline-deficient diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice.59 In the meantime, some studies have reported that ISLT (100 mg/kg) plays a role in liver damage caused by fatty liver. ISLT can effectively reduce lipid accumulation in hepatocytes and high-fat diet (HFD) mice and inhibit the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, down-regulating the expression of inflammatory factors to alleviate liver injury in HFD mice.60 Moreover, ISLT (2.5, 5 and 10 μM) downregulates the production of inflammatory cytokines by blocking the TLR2/MyD88/NF-kappa B signaling pathway, thereby producing significant hepatoprotective effects.61 ISLT (<20 μM) also exert specific anti-inflammatory activity in Mtb infection through Notch1/NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Nevertheless, its anti-inflammatory activity still needs to be further explored.62

Immunomodulatory Effects of ISLT

ISLT possess a vital impact on the treatment of tumor complications and various autoimmune diseases by improving immunity, preventing impaired immune function, and reducing immunotoxicity. In the literature published by Dong et al, it was demonstrated that ISLT (5, 10 and 15 μM) can increase phagocytosis, increase MHC-II production, and reduce the production of some inflammatory factors and costimulatory factors, thereby attenuating the immunotoxicity caused by BDE-47.63 It was documented that ISLT (<20 μM) treats tuberculosis by modulating host immunity. Macrophages are the most important cell type for immune cells that recognize and kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis. ISLT can inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF α, etc.) for immune regulation and exert immune protection.62 According to Feng et al’s experiment, ISLT (50, 100 mg/kg) suppressed oxidative stress and NLRP3 inflammasome activation by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway, thereby treating experimental autoimmune prostatitis.8,64 Furthermore, in reports of multiple sclerosis, an autoimmune-mediated disease of the central nervous system, ISLT (20 mg/kg) also exert immunomodulatory effects by inhibiting the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines.65

Oral ISLT for the Applications of Skin Disease

Melanoma

Melanoma is a type of tumor that grows from melanocytes and is the most aggressive form of skin cancer.66,67 It accounts for approximately 4% of all skin tumors and 80% of deaths.68 It has been evidenced that ISLT (10, 20 and 40 μM) inhibits melanoma cell proliferation, metastasis and inhibits ROS accumulation, playing an important anti-melanoma role. In Xiang et al’s study, ISLT hindered the transition of the melanoma cell cycle from the G1 to S phase by downregulating the expression of cell cycle-related proteins Cyclin D1, CDK2, CDK4 and CHEK1 and inhibited cell proliferation. In addition, ISLT increases the expression of pro-apoptotic protein Bax and reduces the expression of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2, which promotes apoptosis of melanoma cells. H2A. Z.1 is a target of ISLT, and its overexpression partially restores the inhibitory effect of ISLT on melanoma cell proliferation and cell cycle. E2F1 is a downstream target of H2A.Z.1, which is also highly expressed in melanoma and associated with poor prognosis. ISLT significantly down-regulated the expression of two subtypes of histone variant H2A.Z.Z, H2A.Z.1 and H2A.Z.2 and acted through the H2A.Z.1-E2F1 pathway, demonstrating anti-melanoma activity.69 In their previous studies, ISLT upregulated the expression of LRIG1 by inhibiting the expression of miR-301b, thereby activating its target gene LRIG1. Additionally, ISLT increases the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins C-PARP, Bax, and cleaved-caspase-3, reducing the expression of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 and promoting apoptosis of melanoma cells.

MiR-301b is a key regulator of ISLT exerting anti-melanoma effects, and its overexpression can weaken the inhibition of melanoma cell proliferation and the induction of apoptosis by ISLT (10, 20, 40, 80 μM) LRIG1, a downstream target of miR-301b, is under-regulated in melanoma and associated with prognosis. ISLT can significantly downregulate the expression of miR-301b and acts through the miR-301b-LRIG1 pathway, showing anti-melanoma activity.70 In addition, they found that POU class 2 homeobox 3 (POU2F3) is a downstream target of miR-27a, and ISLT (5, 10, 20 μM) upregulates the expression of POU2F3. ISLT downregulates the expression of miR-27a, then upregulates the expression of its downstream target gene POU2F3, which ultimately inhibits the proliferation and migration of melanoma cells through the c-MYC/p53 signaling pathway. The EMT process, and their apoptosis were also suppressed.71

MitoNEET is an iron-sulfur protein located in the outer mitochondrial membrane and plays a key role in regulating cellular energy utilization and lipid metabolism.72,73 ISLT (40 and 60 μg/mL) was capable of significantly reducing the expression level of mitoNEET (also known as CDGSH iron-sulfur domain 1) in A375 melanoma cells. The inhibition of mitoNEET expression by ISLT leads to a significant increase in ROS levels in A375 cells, which triggers cellular oxidative stress responses, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in tumor cells. ISLT can lead to abnormal mitochondrial morphology, a significant decrease in MMP and the activity of respiratory chain complex I–IV, which impairs mitochondrial function in A375 cells. On the other hand, ISLT upregulated the expression of pro-apoptosis-related proteins cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase-3 to promote apoptosis. Therefore, ISLT can induce ROS production by inhibiting mitoNEET expression, which in turn triggers mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis, thereby exerting anti-melanoma effects.74 (The core mechanism of ISLT against melanoma is shown in Figure 2b and Table 1).

Table 1.

Different Mechanisms and Anti-Melanoma Effects of ISLT Cells

| Mechanism of Action | Associated Proteins/Genes | Effects on Melanoma Cells | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Downregulation of cell cycle-related protein expression | Cyclin D1 CDK2 CDK4 CHEK1 |

Inhibition of cell cycle-related protein expression Block the transition from G1 to S phase |

Reduced cell proliferation69 |

| Regulates apoptotic protein expression | Bax Bcl-2 |

Up-regulation of pro-apoptotic protein expression Down-regulation of anti-apoptotic protein expression |

Induction of cell apoptosis69 |

| Acts on H2A.Z.1 targets | H2A.Z.1 E2F1 |

Act on the H2A.Z. 1 targets and affect E2F1 expression | Inhibition of cell proliferation and cell cycle69 |

| Regulates miR-301b expression | miR-301b LRIG1 |

Regulate the expression of miR-301b and affect the expression of LRIG1 | Inhibit cell proliferation and induce cell apoptosis70 |

| Inhibits miR-27a expression | PUOU2F3 | Regulate the expression of miR-27a and affect the expression of POU2F3 Inhibit the EMT process Activate the c-MYC/p53 signaling pathway |

Inhibition of cell proliferation and migration71 |

| Lowers mitoNEET expression | mitoNEET | Increase ROS levels and trigger a cellular oxidative stress response | Trigger mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis74 |

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a multifactorial inflammatory skin disease that can be triggered by external stimuli such as trauma, infection, drug reactions, seasonal changes, etc. These factors lead to the activation of keratinocytes in the skin and the secretion of cytokines such as TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β and IL-6 and cause an immune response in the body. Therefore, pro-inflammatory factors play an important role in the course of psoriasis.75 The experiments by WU et al illustrated that ISLT (1 mg/kg/day and 2 mg/kg/day) ameliorates psoriasis by inhibiting IL-6 and IL-8 and inhibiting inhibitory nuclear factor-kappa B activity, resulting in a reduction in pro-inflammatory. This suggests that ISLT is a potential candidate for the treatment of psoriasis and other autoimmune inflammatory diseases.76

Atopic Dermatitis (AD)

AD is a common chronic inflammatory skin condition characterized by a high degree of heterogeneity.77,78 Epidermal cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 have been reported in the induction phase of allergic contact dermatitis after exposure to sensitizers. ISLT (1%) significantly inhibited 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB)-induced upregulation of IgE and Th2 cytokines. ISLT also impose restrictions on DNCB-induced expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-4 at the site of skin lesions. Moreover, ISLT suppresses the upregulation of CD86 and CD54 and eliminates DNCB-induced activation of p38-α and ERK, suggesting that ISLT is a potential therapeutic agent for the treatment of AD.79

Melanin Deposition in the Skin

Skin pigmentation is characterized by the production and distribution of melanin in the epidermis. Lu et al found that ISLT (1–4 μmol/L) inhibits α-MSH, ACTH, and UV-induced melanin synthesis in addition to inhibiting melanocyte dendritic and melanosome transport. ISLT exerts these effects primarily by activating the extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase pathway. As a result, it induces microphthalmia-associated transcription factor degradation and decreases the expression of tyrosinase, TRP-1, DCT, Rab27a, and Cdc42, ultimately inhibiting melanin production, melanocyte dendritic, and melanosome transport.80

Viral or Bacterial Infections of the Skin

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is a virus that causes herpes after infection, often accompanied by uncomfortable symptoms such as local itching and burning. Experiments have shown that ISLT (12.5, 25, 50 μM) fights HSV-1 by inhibiting viral replication and virus-mediated inflammation through NRF2 signaling. In addition, the antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects of ISLT on vesicular stomatitis virus are related to its ability to activate NRF2 signaling.56 Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a classic drug-resistant organism and a significant cause of bacteremia, endocarditis, skin and soft tissue infections, bone and joint infections, and hospital-acquired infections.81 In experiments by Rashmi Gaur et al, the combined effect of ISLT (50 and 100 mg/kg body weight) with β-lactam antibiotics on mecA-containing MRSA strains in vitro and in vivo was investigated, and ISLT was found to significantly reduce the MIC of β-lactam antibiotics by up to 16 times [∑ fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) 0.312–0.5]. Thus, ISLT is expected to be a compound in combination with anti-MRSA.82

Defects in the Permeability of ISLT

The poor bioavailability of ISLT is mainly related to its functional groups, spatial configuration and physicochemical properties. According to the pubchem database, the molecular skeleton of ISLT is a 1, 3-diphenylpropane-1, 3-dione derivative of a conjugated double bond system. There are three hydrogen bond donors (3 hydrogen in the phenolic hydroxyl groups) and four hydrogen bond receptors: 4 (2 phenolic hydroxyl groups, 1 ketone carbonyl group and 1 enoloxy group. In addition, the polar surface area of ISLT is 77.8 Å2. ISLT contains three phenolic hydroxyl groups, which easily form hydrogen bonds with water molecules and increase molecular hydrophilicity, resulting in decreased transmembrane transport efficiency. In addition, in physiological environments such as the gastrointestinal tract or the skin, phenolic hydroxyl groups are susceptible to oxidation (eg, metabolism by cytochrome P450 enzymes or gut microbiota), or conjugation with endogenous substances (eg, glucuronic acid), reducing bioavailability. In the planar structure of chalcone skeleton, the molecule is rigid plane, which is prone to form strong π-π interactions with the lipid bilayer of biofilm, leading to slow diffusion rate. Planar structures are more difficult to pass through the dynamic pores of the cell membrane than flexible molecules. Studies have found that the 2’,4’ -hydroxyl group and benzene ring easily form a conjugate system, which further enhances the rigidity of the molecule, hinders its conformational adjustment in the lipid membrane, and reduces the permeation efficiency.

LogP represents the lipid-water partition coefficient, with higher values indicating greater lipophilicity of the molecule. The logP value of ISLT was 3.18. The high logP value of ISLT makes it easy to penetrate the lipid cell membrane, theoretically facilitating transmembrane absorption.83

There is a close relationship between the level of pKa and the oral bioavailability of drugs, which is mainly reflected by the dissociation state, transmembrane transport ability and stability of drugs in the gastrointestinal tract. The ideal pKa needs to match the pH of the gastrointestinal tract, so that the drug is mainly non-dissociative at the absorption site, while reducing degradation.84 The structure of ISLT contains three hydroxyl groups (2 ' -, 4 ' -phenolic hydroxyl group and 4-phenyl ring hydroxyl group), which belong to the polyphenolic compounds. The PKa of phenolic hydroxyl groups is usually affected by the position and number of substituents, which is generally in the range of 9–10.85 Nevertheless, the presence of electron-withdrawing groups at the ortho or para sites (eg, hydroxyl) will reduce the pKa through conjugation. In addition, when multiple hydroxyl groups are adjacent (eg, 2 ',4 '-dihydroxyl), the pKa of the first hydroxyl group will be further reduced due to intramolecular hydrogen bonding or conjugation effects (eg, Catechol pKa≈9.4, resorcin pKa≈9.8). Based on the structure, the pKa of ISLT was estimated to be approximately 8.5–9.5. It mainly exists in the non-dissociable form at the pH of the small intestine (5–7.5), which is conducive to transmembrane absorption.

From the perspective of drugs, only drugs with molecular weight <500 Da, suitable lipophilicity and low dissociation are easy to pass through SC. The molecular weight of ISLT is 256.26,86 which is convenient for transmembrane transport and has a positive effect on oral bioavailability. Combined with its lipophilicity (logP=3.18), it can improve the transmembrane absorption efficiency. Although ISLT possesses suitable logP, Pka, and MW values, its polyphenol structure in the gastrointestinal tract may be affected by enzymatic hydrolysis or PH. Drugs enter the liver through the portal vein metabolism, such as the CYP450 enzyme system in hepatocytes to degrade part of the drug. In addition, rapid gastrointestinal peristalsis may reduce drug residence time and may lead to drug degradation. Gastric acid and digestive enzymes may also disrupt the structure of the drug and affect its stability.

In addition, from the perspective of intestinal structure, the intestinal epithelial barrier is the first line of defense against the invasion of various foreign pathogens or toxins. It is primary composed of intestinal epithelial cells, mucosa, and tight junction proteins. Tight junction proteins, including Claudin-1, Occludin, ZO-1 and other functional proteins, are key to maintain the permeability between intestinal epithelial cells. It consists of tight junctions between epithelial cells that limit drug transport across membranes, resulting in low oral bioavailability of drugs.

Oral Administration

Although oral ISLT has many well-defined pharmacological activities, its poor water solubility, low bioavailability, slow intestinal dissolution, and low absorption rate still limit its therapeutic efficacy. It is worth mentioning that changing the drug delivery system can effectively improve its blood concentration and bioavailability.87

Topical Administration

Compared with traditional oral and injectable methods, transdermal administration possesses significant advantages, such as protection against first-pass effects, improved bioavailability, enhanced patient compliance, prolonged drug stability, and the avoidance of systemic toxicity and gastrointestinal irritation. logP value determines the ability of the drug to penetrate the lipid layer of the skin.88 When the logP was too high, the drug was easily retained in the stratum corneum and difficult to diffuse into the dermis. When the logP was too low, it was difficult to penetrate the lipid bilayer of the stratum corneum. Transdermal absorption was better when logP was 1−3.89 The skin surface pH is ≈5.5. When the pKa of the drug is close to this value, the ratio of dissociative to non-dissociative forms is moderate and the transdermal efficiency is high. It has been documented that MW can directly affect the diffusion rate.90 Transdermal resistance increases remarkably ly when MW > 500 Da. When the molecular weight is <300 Da, it is easy to diffuse through intercellular channels.

However, the transdermal bioavailability of ISLT still needs to be improved. Although the logP of ISLT is moderate, the skin penetration capability is insufficient. Its logP value (3.18) indicates better lipid solubility, which theoretically facilitates penetration into the stratum corneum lipid bilayer. However, the balance of “fat solubility” and “water solubility” should be taken into account for skin penetration. When logP >3, the drug was easily retained in the stratum corneum lipids and blocked in the water-soluble diffusion stage to the dermis, forming a “permeation bottleneck”. The surface pH of the skin was ≈5.5, and the pKa of ISLT was significantly higher than this, which made it difficult to transmembrane according to the Henderson-Hasselbalch formula.

In terms of the skin structure, it consists of epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis. The epidermis of the skin consists of five anatomical layers, the outermost of which is the SC.91 It is worth noting that the main factor hindering the transdermal administration of the drug is the SC.92,93 The SC consists of ceramides, cholesterol, and free fatty acids, which protect the skin from physical irritants and maintain skin homeostasis. Nowadays, the penetration enhancement mechanisms are concluded as follows. First is keratin conformation modification: Inducing swelling and enhancing SC hydration by denaturing or modifying the conformational structure of SC keratin. Second is lipid bilayer disruption: Reducing the barrier resistance of lipid bilayers through interference with lipid domain organization. Third is solvent property modulation: Altering SC solvent properties by influencing the partitioning of active compounds or cosolvents into the tissue. Notably, a subset of highly permeable components, such as ISLT, has been reported to self-penetrate by perturbing lipid chain arrangements. Highly permeable drugs exhibit high structural affinity with SC, while impermeable substances hardly interact with SC components.94 Thus, when applying transdermal enhancers, their affinity with the skin should be considered. From a pharmaceutical perspective, the high accumulation of lipids in SC is the main barrier to the penetration of flavonoid molecules (including ISLT). Accordingly, transdermal drug delivery systems containing intercellular lipid components (ceramides) can effectively improve the transdermal efficiency of lipophilic drugs, including ISLT.

The Strategies for Enhanced Oral Bioavailability for ISLT

Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery System (ISLT-SNEDDS/SMEDDS)

Self-emulsifying drug delivery systems are solid or liquid formulations consisting of an oil phase, nonionic surfactants, and co-surfactants, which have the properties of spontaneous formation in the gastrointestinal tract, ease of manufacture, and low cost of oral administration.95 Cao et al used ISLT-SNEDDS to treat eosinophilic esophagitis caused by food allergy, and it was confirmed that SNEDDS significantly increased the maximum plasma concentration and bioavailability of ISLT by 3.47-fold and 2.02-fold, respectively.96 On top of this, in another study of their asthma treatment, the cumulative release rate of ISLT-SMEDDS into the simulated gastrointestinal tract was significantly higher than that of the free ISLT suspension, and the area under the curve was 3.95 times higher than that of ISLT suspension. After oral administration of ISLT-SMEDDS, the Cmax of ISLT increased 3.16-fold from 0.37 ± 0.12 μg/mL to 1.17±0.35 μg/mL, indicating that ISLT-SMEDDS significantly improved its oral bioavailability and anti-asthmatic effect.97 Zhang et al used a self-microemulsifying drug delivery system (SMEDDS) to improve the oral bioavailability and anti-hyperuricemia activity of ISLT, which significantly improves the water solubility and oral bioavailability of ISLT, and enhances its anti-hyperuricemia activity. In addition, it significantly reduced the uric acid level of model rats by inhibiting xanthine oxidase activity, and strengthened its anti-hyperuricemia activity.98

Gel Beads

Gel beads are micro-particles fabricated from natural polymer materials through physical or chemical crosslinking methods. They serve as effective carriers that can control drug release profiles by precisely regulating their crosslinking density and porous architecture, which enables sustained and controlled therapeutic agent delivery.99 The colon has advantages such as a near-neutral pH, long transport times, and low enzyme activity, therefore, it was considered an ideal absorption site to improve the bioavailability of functional drugs.100 Zhao et al prepared ISLT-loaded sodium alginate(SA)and pectin(P)gel beads (SA-P gel beads). In the meantime, to reduce the leakage of drugs in the simulated gastric and intestinal juices, Eudragit S-100 modified SA-P gel beads (EU-SA-P gel beads) were prepared.

Nanocomposite Systems

A nanocomposite system refers to a nanoscale particle system formed by the combination of two or more materials through physical or chemical methods.101 It is primarily conducted to overcome the shortcomings of easy metabolism and poor bioavailability of drugs in vivo, improving the accumulation ability of drugs in the target sites, and balancing the relationship between drug efficacy and side effects.102 Zein is one of the natural biodegradable polymers.103 Zein-based NPs have shown advantages for drug loading and delivery. Xiao et al developed an oral edible nanocomposite system based on zein and caseinate for colon-specific delivery of ISLT to treat ulcerative colitis. (Figure 3a-c). Compared with free ISLT, the cellular uptake capacity of ISLT-loaded zein/caseinate NPs (ISLT@NPs in NCM460 and RAW 264.7 cells was significantly increased, displaying prolonged colonic retention time and enhanced permeability to the colonic epithelium. (Figure 3d–f). Moreover, ISLT@NPs possessed significantly higher targeted accumulation in the colon and improved tissue penetration than free DiR, suggesting higher oral bioavailability. (Figure 4a–d). In another study, Wang et al used a zein-based nanoparticle system to construct ISLT-loaded zein phosphatidylcholine hybrid nanoparticles (ISLT@ZLH NPs). Plasma concentrations of ISLT@ZLH NPs reached a maximum of 3062.19 ± 108.24 μg/L after 0.5 h of oral administration, while the maximum concentration of free ISLT was only 442.59 ± 56.35 μg/L. ISLT@ZLH NPs, functioning as self-assembled particles, demonstrate high stability in the complex gastrointestinal tract environment, thereby significantly enhancing the overall systemic bioavailability of ISLT.104 In another study, they developed a cryoprotectant to address the instability of ISLT@ZLH NPs in frozen environments, which significantly improves their storage stability and effectiveness in TNBC treatment.105

Figure 3.

Characterization and bioavailability enhancement analysis of ISLT@NPs. (a) The appearance of free ISLT, blank NPs, and ISLT@NPs i, indicating that ISLT@NPs successfully improved the water solubility of ISLT; (b) TEM image of ISLT@NPs; (c) The average particle size of ISLT@NPs was 137.32±2.54nm, and had a low polydispersity finger number; (d) ISLT@NP showed almost no change in particle size after storage at 4°C for 10 days, demonstrating its long-term stability at low temperatures; (e) The green fluorescence of free C6 and C6@NPs in NCM 460 and RAW 264.7 cells. It was shown that the use of ISLT@NPs had a higher cell uptake capacity than free ISLT; (f) Simulated gastric juice (SGF, pH 1.5) and simulated small intestinal fluid (SIF, pH 6.8): This pH-responsive property facilitates the specific release of the drug at the colonic site, increasing the bioavailability of ISLT.106 Adapted from Xiao M, Wu SY, Cheng YF et al. Colon-specific delivery of isoliquiritigenin by oral edible zein/caseate nanocomplex for ulcerative colitis treatment. Front Chem. 2022 Sep 9;10:981,055.

Figure 4.

The advantages of zein-casein nanoparticles (NPs) for targeted accumulation in the colon and improved tissue penetration were investigated using the fluorescent dyes DiR and C6 as payloads. (a) In vivo fluorescence imaging of mice at 3, 6, 12, and 24 h post-administration of free DiR and DiR-incorporated NPs (DiR@GNPs). (b) A histogram comparing the fluorescence intensity in mice over time following the oral delivery of free DiR and DiR@NPs (n=3). (c) Fluorescence images of excised gastrointestinal tracts at the indicated time points. (d) Representative fluorescence images of frozen sections from tissues harvested 12 h after administration of free C6 and C6@NPs, with green fluorescence corresponding to C6 and blue fluorescence identifying cell nuclei (scale bar = 200 μm). Adapted from Xiao M, Wu SY, Cheng YF et al. Colon-specific delivery of isoliquiritigenin by oral edible zein/caseate nanocomplex for ulcerative colitis treatment. Front Chem. 2022 Sep 9;10:981,055.

Inclusion of ISLT and Sulfonyl Ether-β-Cyclodextrin (SBE-β-CD)

Cyclodextrins (CDs) are cyclic oligosaccharides with hydrophilic surfaces and hydrophobic cavities that can encapsulate hydrophobic molecules to prepare water-soluble complexes.107–109 It documented that hydrophobic molecules encapsulated in CDs exhibit more potent bioactivity than their free counterparts. In the study by WU et al, ISLT inclusion complexes were prepared using SBE-β-CD, and the water solubility of ISLT was increased by 298-fold from 13.6 μM to 4.05 mM upon the addition of SBE-β-CD. The inclusion complex of ISLT with SBE-β-CD greatly enhances bioavailability. In addition, the stability of ISLT in the biological environment has been significantly enhanced due to the addition of ISLT- SBE-β-CD.110

The Strategies for Enhanced Topical Bioavailability for ISLT

Transdermal drug delivery also possesses many limitations. The skin barrier makes it difficult for most drugs to penetrate through the skin. Therefore, increasing technologies are donated to elevate the permeation efficiency. In terms of physical methods, microneedles and iontophoresis could destroy the stratum corneum and increase the drug permeability.111,112 In terms of chemical methods, the skin structure was temporarily changed by permeation enhancers. In the formulation method, new carriers were designed to carry drugs to improve solubility and stability.113 In addition, a variety of technologies can be combined to improve the transdermal efficiency of drugs. Transdermal efficiency can be improved by using CPE, NLC, and hydrogels.

Plant-Derived Exosomes (ISLT@PE)

Plant-derived exosomes (PEs) are a class of naturally occurring lipid bilayer extracellular vesicles used for the exchange of materials and information between plant cells.114,115 Wang et al encapsulated 3D printed hydrogel scaffolds containing ISLT in PEs from the source of L. barbarum for spinal cord injury repair. The constructed ISLT@PE significantly enhanced the water solubility and bioavailability of ISLT. (Transmission electron micrograph of ISL@PE is shown in Figure 5a). At pH 6.8, the cumulative release rates of free ISLT were 14.9% and 35.4% within 4 h and 48 h, respectively, while the cumulative release rates of ISLT@PE were 15.4% and 80.57%, respectively, confirming its effective enhancement of the stability and solubility of ISLT. (Figure 4c). Meanwhile, the GelMA hydrogel contained in ISLT@PE possesses a three-dimensional mesh structure and high-water content, which can mimic the mechanical properties of natural tissues. (Figure 5b). Therefore, the synergistic application of exosomes and hydrogels greatly optimized the delivery efficiency of ISLT for local administration.116

Figure 5.

Release characterization and bioavailability enhancement of ISLT@PE (a) Transmission electron micrographs of PE and ISL@PE; (b) The scanning electron micrographs of the 3D-printed functional hydrogel (scale bar equals to 20 μm). The arrows indicate the ISL@PE; (c) The in vitro cumulative release rates of ISLT@PE and free ISLT at pH 1.2, 6.8, and 7.4, indicating that ISLT@PE displayed significantly slower release characteristics; (d) The ROS levels in the ISLT@PE group were significantly lower than that in the free ISLT group, suggesting that ISLT@PE was more effective in suppressing inflammation, which indirectly reflected its better bioavailability.116 Adapted from Wang Q, Liu K, Cao X et al. Plant‐derived exosomes extracted from Lycium barbarum L. loaded with isoliquiritigenin to promote spinal cord injury repair based on 3D printed bionic scaffold. Bioeng Transl Med. 2024 Jan 30;9(4):e10646.

Hydrogels

Hydrogel is a hydrophilic polymer with high adhesion to the skin surface, a rich cross-linked network structure and good solubility.117 It exhibits excellent water retention due to the formation of hydrogen bonds with water, which promotes skin penetration of drugs through skin hydration.118 According to Kong et al’s experiment, they synthesized HA-HEC hydrogels for transdermal drug delivery. The water state and swelling characteristics of hydrogels impact the infiltration and drug release efficiency. Due to the high water-holding capacity of HA hydrogel, HA-HEC hydrogel temporarily relaxes the skin barrier through skin hydration, thereby boosting the skin permeability of the active compounds.

Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLC)

NLCs are one of the carriers for the transdermal delivery of drugs with poor water solubility. Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) exhibit strong adhesion to the skin surface, forming an adhesive entity with a lipid film. This film prevents water evaporation from the skin and enhances drug absorption, enabling sustained drug release and prolonged pharmacological activity.119

Transdermal drug delivery systems containing intercellular lipid components ensure effective drug delivery through the intercellular pathway. Geun Young Noh et al discovered a ceramide-based NLC formulation (ISLT-NLC) to help ISLT permeation. ISLT-NLC was prepared by different proportions of liquid and solid lipids, NLC1, NLC2 and NLC3, where the ratios of solid lipid and liquid lipid composition in NLC1, NLC2 and NLC3 were 70:30, 50:50 and 30:70, respectively. O/W nanoemulsion (NE) is composed of 100% liquid lipids. ISLT-NLC3 exhibited the highest encapsulation rate of 89.97±1.71%, whose a permeability through the skin that was approximately three times that of ISLT and ISLT-PG (control group). Ceramides and cholesterol are lipid components of the SC, which have a significant affinity for the skin.120 In addition, the small particle size of NLC3 also plays a contributive role in the penetration of ISLT. Therefore, the skin permeability of NLC is higher than that of NE ascribing to the content of ceramides.121

Nanoemulsions (NEs)

NEs are one of the nanocarriers of poorly soluble water, which can enhance the permeability of drugs.122 Zhang et al discovered a novel loaded ISLT nanoemulsion (ISLT-NE) that inhibits corneal neovascularization by improving the bioavailability of ISLT. (Figure 6a–c). In the in vitro drug release and corneal penetration studies, the apparent coefficient of permeability (Papp) of ISLT -NE was significantly higher than that of ISLT suspension (ISLT-susp), which was increased by about 6.56 times (p < 0.05). (Figure 6d). The ISLT flux of NE was significantly higher than that of drug suspension. These results indicate that ISLT -NE has exhibits higher release and can penetrate more drugs than ISLT-susp. The bioavailability of a single dose of ISLT-NE in tears, cornea, and aqueous humor was 5.76 times, 7.80 times, and 2.13 times higher than that of ISLT-susp, respectively. Therefore, the results of in vitro release and in vitro penetration of ISLT-NE were also significantly enhanced. (Figure 6e–h).123

Figure 6.

ISLT-NE significantly increases the transdermal bioavailability of ISLT. (a and b) TEM morphology of ISLT-NE and Blank-NE, respectively; (c) Within 12 h, over 80% of ISLT was released from ISLT-NE, while ISLT-Susp released less than 40%, indicating that ISLT-NE can successfully encapsulate ISLT into nanoemulsions, significantly enhancing its solubility. Data represented as mean ± SD, n = 3. *p <0.05, **p <0.01, ***p <0.001. Independent Samples t-Test; (d) The Papp of ISLT-NE was (31.36 ± 3.18) × 1 0−4 while the Papp of ISLT-NE was (4.78 ± 0.42) × 1 0−4 cm/h, showing that the corneal permeability of ISLT-NE was about 6.56 times higher than that of ISLT-Susp (p<0.05). Data represented as mean ± SD, n = 6. *p <0.05, **p <0.01, ***p <0.001. Independent Samples t-Test; (e–h) The concentration-time distribution of ISLT-NE and ISLT-Susp in different tissues including tears, conjunctiva, cornea, and aqueous humor (AH) after a single administration. The results indicate that the Cmax and AUC of ISL-NE are significantly higher than those of ISL-Susp in all examined tissues, which leads to a significant enhancement in the bioavailability of ISLT. Data represented as mean ± SD, n = 6. *p <0.05, **p <0.01, ***p <0.001. Independent Samples t-Test.123 Adapted from Zhang R, Yang JJ, Luo Q et al. Preparation and in vitro and in vivo evaluation of an isoliquiritigenin-loaded ophthalmic nanoemulsion for the treatment of corneal neovascularization. Drug Deliv. 2022 Jul 10;29(1):2217–2233.

Chemical Penetration Enhancers (CPE)

CPEs are compounds that increase the skin transmittance of the drug through the reversible destruction of the lipid structure of SC, interaction with intracellular keratin, and increased distribution of the drug or itself in tissues,124 which can improve the transport of drugs in the skin layer. Flavonoid molecules tend to interact with skin lipids, meanwhile, enhancers penetrate into the SC to interfere with lipid alignments to facilitate drug penetration. Wang et al found that heat capsaicin (CaP) had a significant effect on the lipid fluidity, water loss and surface structure changes of the SC, thereby demonstrating a higher permeability enhancement effect on ISLT compared with other enhancers.94 Deep eutectic solvents (DES) are also a kind of CPE.125 DES are low-melting-point mixtures formed by two or more substances through hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and other interactions.126 In terms of drug delivery, DES can improve the solubility and stability of drugs and improve the efficacy of drugs. Notably, the solubility of the drug and its release in the body are key to evaluating the effectiveness of the formulation. Hu et al prepared three DESs using choline chloride (ChCl) and oxalic acid (OA)/malic acid (MA)/gallic acid (GA) as raw materials, and studied the solubility and release of ISLT in different DESs. The solubility of ISLT in pure water was low at 3.99 μg/mL. By contrast, the solubility of it in ChCl-OA DES, ChCl-MA DES, and ChCl-GA DES was 119.99 mg/mL, 20.17 mg/mL and 271.13 mg/mL, respectively. The solubility was increased by 30073 times, 5055 times and 68103 times, respectively. The mechanisms of enhanced solubility indicated that the hydrogen bond interaction of ISLT in DES solvent was more potent than that of ISLT in water, resulting in higher solubility of ISLT in DESs. The release rate and cumulative release of ISLT in ChCl-GA Vogels were higher than those of ChCl-OA/MA. These results suggested that the viscosity of the gel and the solubility in the ISLT gel jointly affected the release of the drug. Taken together, DESs are expected to be an effective strategy to improve the solubility and drug release of other poorly soluble drugs, laying the foundation for improving their transdermal bioavailability.127 (Table 2).

Table 2.

The Comparison of the Features, Composition and Enhanced Bioavailability of ISLT in Different Oral and Transdermal Drug Delivery Systems

| Oral Administration | |||

| Drug Delivery Systems | Features | Main Components | Improve Bioavailability |

| ISLT-SNEDDS96 | 1. Formula optimization 2. Particle size decreased (the average particle size after optimization is about 33.4±2.46) 3. Reduced risk of hemolysis (lower use of Tween 80) 4. Animal experiments showed no obvious toxicity |

Oil Phase: Ethyl Oleate Surfactant: Tween 80 and Cremophor® EL in a ratio of 7:3 Co-surfactant: PEG 400 and 1,2-propylene glycol in a ratio of 1:1 ISLT |

1. Cmax increased 3.47 times, from 0.43 μg/mL to 1.52μg/mL 2. AUC increased 2.02 times from 1.86 μg·mL-1·h to 3.76 μg·mL-1·h |

| ISLT-SMEDDS97 | 1. Small size and high dispersion 2. Decreased cytotoxicity 3. Good dilution stability, PH tolerance and storage stability |

Oil Phase: Ethyl Oleate Surfactant: Tween 80 Co-surfactant: PEG 400 ISLT |

1. Cmax increased 3.16 times, from 0.37 ± 0.12 μg/mL to 1.17±0.35 μg/mL 2. AUC increased by 3.93 times from 0.67 ± 0.11 to 2.63±0.55 μg·mL−1 |

| EU-SA-P gel beads128 | 1. Improve drug stability and bioavailability 2. Specific targeted colon 3. Tight structure 4. Low toxicity |

SA P Eudragit S-100 ISLT |

1. In simulated gastric juice and simulated intestinal juice (after 5 h of exposure) The cumulative drug release percentage was only 12.74%±3.55% 2. In the simulated colon fluid (from the 5th h to the 12th h): The cumulative drug release percentage was 50.64%±2.22%, which was 3.97 times of that of the anterior colon stage |

| ISLT@ZLH NPs104 | 1. Efficient preparation method 2. High drug loading (drug loading efficiency 6.56±0.83%) 3. High encapsulation rate (encapsulation rate 96.75±1.41%) 4. High stability 5. Targeted delivery 6. Selective toxicity |

Zein Soybean phospholipids Cholesterol Casein ISLT |

1. Cmax increased by 6.09 times, from 442.59 ± 56.35 μg/mL to 3062.19 ± 108.24 μg/mL. 2. AUC increased by 3.08 times, from 725.46 ± 67.34 μg·h/L to 2756.78 ± 218.34 μg·h/L. |

| Inclusion of ISLT and SBE-β-CD110 | 1. Significantly enhance the water solubility of ISLT 2. Enhance the antioxidant capacity of ISLT 3. Improve the biological stability |

SBE-β-CD ISLT |

The solubility of ISLT increased 298 times, from 13.6μM to 4.05 mM |

| Topical/transdermal administration | |||

| Drug delivery systems | Features | Main components | Improve bioavailability |

| ISLT@PE116 | 1. High biocompatibility 2. Safe and non-toxic 3. Successfully carry model drugs and target genes |

PEs ISLT |

At pH 6.8, the cumulative release rates of free ISLT were 14.9% and 35.4% at 4 h and 48 h, respectively, while the cumulative release rates of ISLT@PE were 15.4% and 80.57% at 4 h and 48 h, respectively, suggesting that ISLT@PE exhibited significantly slower release characteristics than free ISLT. |

| HA-HEC hydrogels129 | 1. High water absorption and expansion performance2. Controllable mechanical properties of hydrogels (hardness, adhesion, cohesion, etc). 3. No cytotoxicity 4. PH sensitivity 5. ISLT in hydrogels obeys Fick’s diffusion law |

HA HEC Divinyl Sulfone ISLT |

The total permeability of ISLT based on HA-HEC hydrogel was significantly higher than that of other controls: 1. HA-HEC hydrogels:20.0 μg/cm2 2. PB:13.0 μg/cm2 3. 20%BG/PB:12.1 μg/cm2 |

| ISLT-NLC121 | 1. Small particle size (average particle size between 150.19–251.69 nm) 2. High drug loading efficiency (ISLT-NLC3 had the highest encapsulation rate of 89.97±1.71%) 3. Sustained-release drug 4. Strong skin affinity |

Solid Lipids: Ceramide and Cholesterol Liquid Lipid: Caprylic/Capric Triglyceride Surfactants: Tween 80 and Mannnosylerythritol Lipid |

1. Within 24 h, the permeability of NLC3 (10.09 μg/cm2) was about 3 times that of ISLT-PG (3.99 μg/cm2), and both were higher than those of NLC1 and NLC2 2. The percentage of total skin penetration of NLC3 (20.88%) was significantly higher than that of ISLT-PG (7.28%), and both were higher than those of NLC1 and NLC2 |

| Topical/transdermal administration | |||

| Drug delivery systems | Features | Main components | Improve bioavailability |

| ISLT-NE123 | 1. Significantly increased ISLT concentration 2. Faster drug release 3. The corneal permeability stronger 4. Nano-size advantage (particle size 34.56±0.80 nm) 5. Good stability |

Oil: Propylene Dicaprylate Surfactant: Cremophor® EL Cosurfactant: PEG400 Additives: HA |

1. The Papp of ISLT-NE was about 6.56 times higher than that of ISLT-Susp 2. In tears, cornea and aqueous humor, ISLT - NE bioavailability than ISLT - Susp increased 5.76 times, 7.08 times and 2.13 times |

| DESs127 | 1. Improve the solubility of ISLT 2. Follow the first-order release pattern 3. Low toxicity |

ChCl OA MA GA |

The solubility of ISLT is significantly improved: Water:3.99 μg/mL ChCL-OA DES:119.99 mg/mL, improved 30073 times ChCl-MA DES:20.17 mg/mL, improved 5055 times ChCl-GA DES:271.13 mg/mL, improve 68103 times |

Injections

T-ALL-Derived Exosomes (Exo-ISLT)

Extracellular vesicles are a class of cell-derived lipid bilayer membrane nanoscale particles.130 Exosomes (Exo) is a typical natural carrier with low toxicity and immunogenicity, harboring capabilities such as precise targeting and crossing the blood-brain barrier. Exo in the latest discovery by Liu et al, demonstrated that it effectively tricked tumor cells into accurately and abundantly internalizing drug molecules for highly selective and targeted delivery of ISLT to the bone marrow (which functioned like a Trojan horse). Exo-ISLT showed significantly higher plasma concentration, cellular uptake and drug enrichment in bone marrow compared to free ISLT, as well as a 3.8-fold increase in clearance half-life and prolonged in vivo retention time.131

ISLT- Nanofiber Scaffolds (ISLT-NF)

Electrospinning is a method applied to nanofibers in drug delivery systems, and nanofibers loaded with anticancer drugs can promote the control and sustained release of drugs at the site of action with higher efficacy.132 Experiments incorporate ISLTs into NF vectors to enhance their efficacy, accuracy, and stability in drug delivery to target cells. NF vectors protect ISLTs from degradation and improve their stability, thereby increasing their bioavailability. Furthermore, ISLT-NF utilizes NF with a high surface area-to-volume ratio to achieve controlled release of ISLT, which ensures enough concentration at the target site compared to the control and free ISLT-treated groups. Additionally, it allows tumor cells to be exposed to ISLT for a more extended period, thereby enhancing its therapeutic effect.133

Liposomes

In Song et al’s study, a novel ISLT-loaded liposome (ISLT-LP) was designed using DSPE-PEG2000 as the carrier material and combined with the brain-targeting peptide angiopep-2 to modify ISLT. It was designed to overcome the poor water solubility, low bioavailability and insufficient distribution of ISLT in the brain. The drug loading of ISLT-LP was 7.63±2.62%, and the encapsulation efficiency was 68.17±6.23%. The results showed that the plasma elimination half-life of ISLT-LP was significantly extended by 2.6 times compared with ISLT. The AUC of ISLT-LP was significantly higher than that of ISLT, and the mean residence time (MRT) of ISLT-LP was also significantly prolonged. Meanwhile, the clearance rates of ISLT and ISLT-LP were 5.78 kg and 3.64 L/h.kg, respectively, and the clearance rate of ISLT-LP was significantly reduced.

In addition, the relative bioavailability of ISLT-LP was 148.96%, which significantly improved its water solubility and circulation time in vivo compared with the ISLT monomer. The specific brain-targeted ligand-modified nanomicelles can bind to endogenous receptors on the blood-brain barrier (BBB), increasing the amount of BBB transmitted through it and enhancing its accumulation in brain tissue.134

Pharmacokinetic Study of ISLT in vivo

ISLT exhibits diverse pharmacokinetic characteristics in vivo. It has been reported that ISLT has a wide tissue distribution in rats and can be detected in almost all tissues, especially at high concentrations in the intestine, liver, and stomach. Its short half-life of approximately 67 min indicates rapid elimination without significant accumulation. The stability of ISLT in liver microsomes of different species was in the order of rat > beagle dog > monkey > human > mouse.135 Moreover, the pharmacokinetic profile of ISLT in rats demonstrated low plasma concentrations and individual variation.136 In the meantime, its pharmacokinetic characteristics in rats showed its rapid absorption and clearance.137

Oral Administration

Oral drug delivery systems such as ISLT-SNEDDS improved Cmax of ISLT from 0.43 μg/mL to 1.52 μg/mL (3.47-fold increase) by optimizing the formulation, reducing the particle size to about 33.4±2.46, and lowing the dosage of Tween-80. AUC increased from 1.86 μg·mL−1·h to 3.76 μg·mL−1h (increased by 2.02 times).96 The Cmax of ISLT-SMEDDS increased from 0.37±0.12μg/mL to 1.17±0.35 μg/mL (3.16 times), and the AUC increased from 0.67±0.11 to 2.63±0.55μg·mL−1·h (3.93 times) due to the characteristics of small particle size and high dispersion.97 EU-SA-P gel beads had colon targeting properties, and the cumulative drug release in simulated colon fluid was 50.64%±2.22% within 5–12 h.128 In ISLT@ZLH, the Cmax of the NPs increased from 442.59±56.35μg/mL to 3062.19±108.24 μg/mL (6.09 times) due to the high drug loading and encapsulation efficiency. AUC increased from 725.46±67.34 μg·h/L to 2756.78±218.34 μg·h/L (3.08 times).104 Moreover, the solubility of ISLT was increased by 298 times after incorporation of ISLT with SBE-β-CD. All of the above formulations improved the bioavailability of ISLT.

Topical Administration

The PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus and other platforms displayed that there were few studies on the in vivo kinetics of ISLT using microdialysis methods in local drug delivery. At present, the in vivo kinetic experiments of ISLT mainly focus on oral administration and the injection route of administration.

Toxicity and Safety

At present, there are few documents on the safe concentration of ISLT in humans. However, many studies have been conducted cells and animal models.

Cellular Security of ISLT

In a study using human gastric normal epithelial cells (GES-1), Xiu-Rong Zhang confirmed via the CCK8 proliferation assay that when the concentration of ISLT was ranged from 0 to 20 μM. It indicated that GES-1 cell proliferation was not significantly inhibited within 72 h. However, ISLT exhibited a gradually increasing inhibitory effect on the proliferation of MKN28 gastric cancer cells at the same concentration range, with an inhibition rate exceeding 40% at 20 μM. These results indicate that ISLT exhibits low cytotoxicity toward normal cells within the 0–20 μM concentration range, with 20 μM being the highest safe concentration, while lower concentrations (eg, 5–15 μM) have even less impact on normal cell proliferation.138 When evaluating the toxicity of ISL on human hepatocellular carcinoma cells and normal hepatic epithelial cells, Shanshan Wu set up an experimental design with concentration gradients of 1.25, 2.5, and 5 μg/mL for 48 h. CCK8 assays showed that none of the concentrations significantly inhibited cell proliferation.10 Deshan Yao used 5, 25, and 50 μmol/L of ISLT to treat hypoxic/reoxygenated (H/R) neonatal mouse myocardial cells. CCK8 assays revealed that cell viability was significantly higher than that in the H/R model group in all concentration groups within 24 h, with the strongest protective effect observed at 50 μmol/L. Cell damage markers demonstrated that ISLT treatment significantly reduced lactate dehydrogenase activity and malondialdehyde levels while increasing superoxide dismutase activity, confirming that ISTL exhibits no cytotoxicity within the 5–50 μmol/L concentration.55 Jihua Li’s study on the cellular safety of ISLT showed that the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of the human pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma cell lines 266–6, TGP49, and TGP47 were 262 μg/mL, 389 μg/mL, and 211 μg/mL, respectively, demonstrating a dose-dependent inhibition of tumor cell viability. In experiments with human umbilical vein endothelial cells, even at the highest tested concentration of 1000 μg/mL, the survival rate of normal cells remained above 90%, with no significant cytotoxicity detected. The experiments confirmed that ISLT exhibits no significant toxicity to normal cells within the concentration range of 0–1000 μg/mL.12

Animal Model Security Study of ISLT

Based on multiple animal studies, ISLT has demonstrated high safety in mouse and rat models.

Acute Toxicity Experiments in Mice and Rats

Acute toxicity evaluations were conducted in Kunming mice (15–20 g) and Sprague-Dawley rats (105–120 g), administering a single oral gavage dose of 160 mg/kg (mice) and 110 mg/kg (rats) of ISL@ZLH NPs, with 10 animals (5 males and 5 females) per group. Mortality, body weight changes, behavioral abnormalities, and macroscopic pathological examination of major organs (liver, kidney, etc.) were monitored for 7 consecutive days. Results showed no mortality in both species (0/10), consistent body weight gain with the control group, normal blood biochemical indicators, and no visible organ damage or enlargement. The acute safety concentration thresholds were determined as ≥160 mg/kg for mice and ≥110 mg/kg for rats, with no significant acute toxicity observed after single oral administration.14

Subacute Toxicity Experiment in Rats

Sprague-Dawley rats (5–6 weeks old) were divided into three dose groups (27.5, 55, 110 mg/kg) and received daily oral administration of ISLT@ZLH NPs for 30 and 90 days, with 20 rats (10 males and 10 females) per group. Hematological parameters (RBC, WBC, Hb), biochemical indicators (SGPT, BUN, GLU), and histopathological changes in 18 organs (liver, kidney, etc.) were simultaneously monitored. Results indicated no significant fluctuations in hematological indices across dose groups during continuous administration. Normal biochemical parameters, and no cellular damage or inflammatory responses in organs like the liver and kidneys were observed via HE staining, with tissue structures consistent with the control group. This experiment confirmed that the subacute safety concentration for oral ISLT@ZLH NPs in rats was ≤110 mg/kg/d, with no toxic effects observed after 90 consecutive days of administration.139

The Problems and Prospects of the Enhanced Bioavailability for ISLT

In this review, a variety of strategies have been concluded to address the poor bioavailability of oral ISLT, which mainly started with technologies such as nanoemulsion drug delivery systems, gel beads, exosomes, nanoparticle systems, and inclusion complexes to improve their bioavailability. Self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery systems (SNEDDS) can spontaneously form nanoemulsions and improve the bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs.140 In the study of Cao et al, ISLT-SNEDDS can significantly improve the solubility and stability of ISLT in vivo, reduce the degradation of ISLT in the stomach and improve its absorption rate in the small intestine, thus increasing its bioavailability through self-nanoemulsion technology. Nevertheless, there are still defects. The preparation process of ISLT-SNEDDS is relatively complex, and the proportion and preparation conditions of each component need to be accurately controlled, which is not conducive to industrial production. Although the ratio of surfactant is optimized (reducing the dosage of Tween 80), the ISLT-SNEDDS formulation still possesses a particular risk of dosage as a surfactant. When used in high doses, Tween 80 can easily cause hemolysis, neuropathy, nephrotoxicity, or hypersensitivity reactions.141 To overcome this limitation, it is critical to find surfactants with lower toxicity. Surfactants of natural origin or bio-based surfactants are introduced. As a commonly used carrier for poorly soluble drugs, gel beads can effectively achieve a slow and continuous release process by precisely adjusting the degree of crosslinking and the internal pore structure. The colon-targeted delivery ISLT system prepared by Zhao et al reduced the early release and degradation of ISLT in the stomach and small intestine. It improved its absorption rate in the colon, thereby increasing its bioavailability. The formation of gel beads in the system also increases the dispersion area of ISLT, which helps to improve the solubility of ISLT. In addition, the polymers in the gel beads (sodium alginate, pectin, and Eudragit S-100) can also improve the solubility of the drug through solubilization. However, the preparation process of gel beads is also relatively complex, and the requirements for production equipment and operators are high, which is not favorable to industrial production.142 High stability is the main advantage of polymer NPs, which can significantly improve the bioavailability and stability of ISLT in vivo. However, it also suffers from uncertainty about long-term biosafety, limitations of low drug loading, and barriers to large-scale production.

Additionally, ISLTs also have challenges in percutaneous delivery, such as the treatment of melanoma. Zhang et al used low-frequency physical ultrasound to promote the transdermal delivery of gambogic acid (GA) by combining the skin penetration promoters azone and propylene glycol, which significantly increased the transdermal penetration of GA.143 However, both ISLT and GA are derived from natural plants and face the same challenges, such as high molecular weight, poor water solubility and low bioavailability. In the future, we can mimic GA by applying ISLT to the local treatment of melanoma, improving the transdermal absorption efficiency and anti-melanoma efficacy of ISLT by combining chemical enhancers and low-frequency ultrasound technology to. Therefore, it is critical to explore a new pathway for topical treatment of melanoma based on the present results and innovative ideas and strategic guidelines using ISLT. The hydrogel’s water-holding property and three-dimensional network structure can temporarily loosen the skin barrier and enable ISLT diffuse and penetrate through the skin, thereby improving the transdermal delivery efficiency. It can maintain the effective concentration of the drug locally in the skin by controlling the release rate of ISLT. Nevertheless, inadequate mechanical properties and lower biocompatibility limit their application. In a study by Chen et al, the synergistic application of ionic liquids and hydrogels was able to significantly improve the skin permeability and stability of the drug, showing higher biocompatibility. Therefore, the synergistic use of two or more is an effective way to solve the problem of a single carrier.144 Although NLC has the advantages of better physical stability, the formation of a film on the skin to reduce skin irritation, the precision of its release control technology, drug loading and drug targeting still need to be improved. According to relevant reports, ISLT eutectic gels based on DESs showed unique release characteristics. Compared with other preparations DESs and eutectic gels have the advantages of low toxicity and strong adjustability, which provide a new direction for improving the solubility and release of ISLT. Furthermore, the development of drug-carrying exosomes is a good choice to address the aforementioned deficiencies, such as low immunogenicity, poor precision targeting, and poor stability.

Two or More Preparations are Used in Combination

Synergistic use of multiple drug carriers has emerged as an effective strategy to address bioavailability limitations. In the study by Afroditi Kapourani et al, a ternary amorphous solid dispersion (ASD) composed of mesoporous silica (eg, Syloid 244FP) and polymers (coPVP, HPMC) demonstrated dual mechanisms. The porous structure of mesoporous silica physically restricts drug crystallization, while polymers inhibit precipitation to maintain supersaturation. For olanzapine (OLN), the ternary ASD (OLN-coPVP-Syloid 244FP) showed ~2-fold higher in vitro dissolution than the pure drug and prolonged supersaturation duration. Notably, this system remained amorphous after 8 months of storage, whereas binary systems (eg, OLN-Syloid 244FP) exhibited crystallization. Hydrogen bonding between coPVP and mesoporous silica (evidenced by ATR-FTIR shifts in Si-OH peaks) stabilized the amorphous state and prevented recrystallization, outperforming single carriers in both dissolution and stability.145

Xu et al developed a PEG-PCL/Pluronic P105 composite micelle carrier for doxorubicin, leveraging PEG-PCL’s high drug loading capacity and Pluronic P105’s membrane permeability. For ISLT, its polyphenolic structure (hydrophobic benzene rings and phenolic hydroxyls) can embed into the PCL core of PEG-PCL via hydrophobic interactions (estimated loading rate 50–60%) and form stable micelles with Pluronic P105. The system enables pH-responsive release: ≤30% drug release in neutral blood (pH 7.4) within 2.5 h, increasing to 65% in tumor acidic microenvironments (pH 5.0) over 48 h, which avoids aldehyde oxidation and ensures target-site activation. This dual-release profile enhances oral absorption efficiency.146

Fai A. Alkathiri et al constructed ternary solid dispersions with silicon lin, water-soluble polymer (KL), and surfactant (PL), overcoming single-carrier limitations through “polymer solubilization + surfactant stabilization”. This synergistic model improves dissolution rate and cell targeting, which provides a promising strategy for oral delivery of BCS class II drugs like ISLT.147

Solvent-Free Chemical Method

ISLT Derivatives Based on 4’-OH Related Groups

The development of ISLT derivatives is a promising pathway. The chemical structure of ISLT consists of a benzene ring and a five-membered ring structure containing nitrogen atoms, oxygen atoms, and a hydroxyl group attached to the benzene ring.2 Recently, some derivatives of ISLT have been produced by the introduction of fluorine atoms and the substitution of the 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl group.26 Therefore, chemical reactions such as esterification, amidation, and etherification could substantially improve its solubility, which is expected to enhance the bioavailability and therapeutic effect of drugs.