Abstract

Antimicrobial stewardship programs in hospitals seek to optimize antimicrobial prescribing in order to improve individual patient care as well as reduce hospital costs and slow the spread of antimicrobial resistance. With antimicrobial resistance on the rise worldwide and few new agents in development, antimicrobial stewardship programs are more important than ever in ensuring the continued efficacy of available antimicrobials. The design of antimicrobial management programs should be based on the best current understanding of the relationship between antimicrobial use and resistance. Such programs should be administered by multidisciplinary teams composed of infectious diseases physicians, clinical pharmacists, clinical microbiologists, and infection control practitioners and should be actively supported by hospital administrators. Strategies for changing antimicrobial prescribing behavior include education of prescribers regarding proper antimicrobial usage, creation of an antimicrobial formulary with restricted prescribing of targeted agents, and review of antimicrobial prescribing with feedback to prescribers. Clinical computer systems can aid in the implementation of each of these strategies, especially as expert systems able to provide patient-specific data and suggestions at the point of care. Antibiotic rotation strategies control the prescribing process by scheduled changes of antimicrobial classes used for empirical therapy. When instituting an antimicrobial stewardship program, a hospital should tailor its choice of strategies to its needs and available resources.

INTRODUCTION

The development and widespread use of antimicrobial agents has been among the most important public health interventions in the last century (3). The effect of these agents, along with improved sanitation and the broad application of vaccination (in those countries where these are available), has been a substantial reduction in infectious mortality (4). Antimicrobials are not a human invention per se, having been present (albeit invisible to humans) in the environment for millennia. Humans have co-opted the molecules that fungi, soil actinomycetes, and other microorganisms use to secure their ecologic niche in a world teeming with competitors (37, 39).

Soon after the widespread use of natural antimicrobial products in medicine, human pathogens expressing resistance to these agents were isolated. Genes encoding resistance had likely been present for thousands of years, either as countermeasures to the effects of antimicrobials or for as-yet undetermined functions, and incorporation of these genes by human commensal and pathogenic flora rapidly followed (38, 73). What has been remarkable has been microorganisms' ability to rapidly develop resistance to antimicrobials that have been modified to evade the original mechanisms of resistance, as well as to those novel synthetic agents that had never been present in the environment previously. This is a testament to the impressive reproductive rate of most microorganisms, the tremendous selective pressure that antimicrobial agents apply to these populations, and the huge number of unculturable organisms in the environment that may be serving as reservoirs of antimicrobial resistance genes.

The mass production of antimicrobials gave humanity a temporary advantage in the struggle with microorganisms; however, if the current rate of increase in resistance to antimicrobial agents continues, it is possible we may enter into what some have termed the postantibiotic era (152). The introduction of new agents that evade resistance mechanisms has allowed medicine to stay one step ahead of resistance. However, the pace of antimicrobial drug development has markedly slowed in the last 20 years; United States Food and Drug Administration approval of new antibacterial agents decreased 56% from 1983 to 2002 (147).

Cooperative efforts between industry, academia, and government to revive the pipeline of antimicrobial drugs have been proposed (127). However, given the lag time between discovery of molecules active in vitro and the introduction of drugs into clinical use, we face a decade or longer during which introduction of novel antimicrobial agents is expected to be minimal. Even when new agents are introduced into clinical practice, resistance to these drugs will certainly appear. For example, despite encountering virtually no cases of resistance in clinical trials with the novel antimicrobial daptomycin, case reports of resistance to this agent are beginning to appear shortly after its introduction into (limited) clinical use (101). Thus, to ensure that options exist for treating infections, it is imperative to make the best use of the antimicrobials that are currently available.

Antimicrobial stewardship programs have been pursuing this goal for decades. These programs focus on ensuring the proper use of antimicrobials to provide the best patient outcomes, lessen the risk of adverse effects, promote cost-effectiveness, and reduce or stabilize levels of resistance. Until recently, their focus has been on the first three goals (patient outcome, toxicity, and cost). It is likely that in the decade to come, the latter objective of mitigating antimicrobial resistance will be paramount. In this review we will address the rationale, structure, analysis, and outcomes of antimicrobial stewardship programs with a special interest in their impact on antimicrobial resistance.

ASSOCIATION BETWEEN ANTIMICROBIAL USE AND RESISTANCE

To optimally manage antimicrobial use to attenuate antimicrobial resistance, it is necessary to have a precise understanding of the relationship between antimicrobial use and resistance. The spectrum of requisite knowledge stretches from the in vitro interactions between antimicrobial molecules and their microbial targets, to the individual risks associated with administering an antimicrobial to a given patient, to the ecologic level where the aggregate effects of antimicrobial use are studied using hospitalwide or nationwide data. The nature of these drug-organism relationships is likely to be highly variable depending on the particular drug-bug combination of interest, although some common themes may emerge (139). Despite thousands of scientific investigations on the subject, we are only beginning to understand many of these complex relationships, especially at an ecologic level (70, 112).

Antimicrobial management programs based on an incomplete understanding of the relationship between antimicrobial use and resistance may be fruitless, or at worst even counterproductive. After the rapid rise in vancomycin-resistant enterococci occurred in the United States during the mid-1990s, recommendations to restrict intravenous vancomycin use were strongly advocated (29). These recommendations were based on biological plausibility as well as early studies implicating vancomycin use as a risk factor for development of vancomycin-resistant enterococcal infections (10, 18, 88, 132). Many antimicrobial management interventions were developed with a primary focus being the restriction and monitoring of vancomycin use (51). However, subsequent investigations identified a much lower risk of vancomycin-resistant enterococci associated with intravenous vancomycin use, and when the most rigorous criteria were applied, did not implicate vancomycin at all (69). Instead, agents such as broad-spectrum cephalosporins and clindamycin appeared to increase the risk for isolation of vancomycin-resistant enterococci, with different agents having different effects on acquisition, amplification, or transmission.

Subsequent studies in animal models have suggested mechanisms for the observed increase in risk of vancomycin-resistant enterococci with cephalosporin administration, as well as for possible protective effects with agents such as piperacillin-tazobactam (135). Thus, although vancomycin use (especially of the oral formulation) likely contributed to the emergence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci, other agents may be more important in perpetuating vancomycin-resistant enterococci. The importance of these agents was not obvious before studies were performed. Interventions aimed at modulating use of these drugs, as well as vancomycin, have been successful at reducing the rate of vancomycin-resistant enterococci (68, 103, 129). Similarly, a number of studies have associated fluoroquinolone use with isolation of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (41, 63). The magnitude of the association appears to exceed what would be expected through simple selection pressure (most methicillin-resistant S. aureus are also fluoroquinolone resistant), since other agents that lack activity versus methicillin-resistant S. aureus do not show the same degree of association (158). In vitro studies have subsequently suggested that fluoroquinolones may have unique effects on expression of adherence determinants and resistance factors in staphylococci (14, 155). It remains to be seen whether control of fluoroquinolone use will aid in reducing the growth of methicillin-resistant S. aureus in health care institutions.

These examples of antimicrobial use-resistance relationships illustrate the need for continuing studies of the association between antimicrobial use and resistance to inform effective antimicrobial stewardship programs. It should also be emphasized that adherence to sound methodological principles is paramount in performing such studies. For example, a meta-analysis of investigations that examined risk factors for vancomycin-resistant enterococci found that different risk factors were reported according to whether the studies followed good epidemiologic standards or not (69). Recent reviews have highlighted the importance of proper study design, control group selection, and adjustment for confounding factors (72). Many studies that are commonly cited in the antimicrobial resistance literature did not meet these criteria. Thus, as we enter a period when antimicrobial stewardship becomes critically important, the availability of methodologically sound studies to guide the management of antimicrobial agents is a priority.

DEFINITION AND PREVALENCE OF ANTIMICROBIAL STEWARDSHIP

The terms used to refer to antimicrobial stewardships programs may vary considerably: antibiotic policies, antibiotic management programs, antibiotic control programs, and other terms may be used more or less interchangeably. These terms generally refer to an overarching program to change and direct antimicrobial use at a health care institution, which may employ any of a number of individual strategies (Table 1). The variety of activities that can be considered antimicrobial stewardship under the broadest definition are large. Substitution among antimicrobials in the same class for cost-saving purposes, intravenous-to-oral switching programs for highly bioavailable drugs, and pharmacokinetic consultation services may all impact on antimicrobial use. However, these measures are less likely to have an impact on overall antimicrobial use or antimicrobial resistance, and we will not consider them here except as part of more comprehensive programs.

TABLE 1.

Summary of antimicrobial stewardship strategies

| Strategy | Procedure | Personnel | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education/guidelines | Creation of guidelines for antimicrobial use | Antimicrobial committee to create guidelines | May alter behavior patterns | Passive education likely ineffective |

| Group or individual education of clinicians by educators | Educators (physicians, pharmacists) | Avoids loss of prescriber autonomy | ||

| Formulary/restriction | Restrict dispensing of targeted antimicrobials to approved indications | Antimicrobial committee to create guidelines | Most direct control over antimicrobial use | Perceived loss of autonomy for prescribers |

| Approval personnel (physician, infectious diseases fellow, clinical pharmacist) | Individual educational opportunities | Need for all-hours consultant availability | ||

| Review and feedback | Daily review of targeted antimicrobials for appropriateness | Antimicrobial committee to create guidelines | Avoids loss of autonomy for prescribers | Compliance with recommendations voluntary |

| Contact prescribers with recommendations for alternative therapy | Review personnel (usually clinical pharmacist) | Individual educational opportunities | ||

| Computer assistance | Use of information technology to implement previous strategies | Antimicrobial committee to create rules for computer systems | Provides patient-specific data where most likely to impact (point of care) | Significant time and resource investment to implement sophisticated systems |

| Expert systems provide patient-specific recommendations at point of care (order entry) | Personnel for approval or review (physicians, pharmacists) Computer programmers | Facilitates other strategies | ||

| Antimicrobial cycling | Scheduled rotation of antimicrobials used in hospital or unit (e.g., intensive care unit) | Antimicrobial committee to create cycling protocol | May reduce resistance by changing selective pressure | Difficult to ensure adherence to cycling protocol |

| Personnel to oversee adherence (pharmacist, physicians) | Theoretical concerns about effectiveness |

During an outbreak of infections due to antimicrobial-resistant organisms, temporary restrictions on antimicrobial use may be applied along with enhanced infection control measures to terminate the outbreak. In general, unless these interventions are part of an ongoing program to optimize antimicrobial use, we will not focus on these temporary interventions. Thus, we will define an antimicrobial stewardship program as an ongoing effort by a health care institution to optimize antimicrobial use among hospitalized patients in order to improve patient outcomes, ensure cost-effective therapy, and reduce adverse sequelae of antimicrobial use (including antimicrobial resistance). In reality, many early programs were designed to control rising acquisition cost of antimicrobial drugs. Reduction in total or targeted antimicrobial use, increase in appropriate drug use, improvement in susceptibility profiles of hospital pathogens, and improvement in clinical markers (such as reduced length of stay) are now being increasingly targeted as outcomes by antimicrobial stewardship programs.

Several surveys have attempted to determine what proportion of health care institutions have implemented antimicrobial stewardship programs. Rifenburg et al. surveyed 88 United States hospitals and found that two-thirds had an antimicrobial formulary (137). Twenty-eight percent of hospitals required prior approval of an infectious diseases clinician before dispensing certain antimicrobials, while in 21% approval by a clinical pharmacist was required. Larger hospitals tended to be more likely to have antimicrobial restriction programs. Of 502 physician members of the Infectious Diseases Society of America's Emerging Infections Network responding to a survey, 50% reported that their hospital of practice had an antimicrobial restriction program in place, with teaching hospitals significantly more likely to have such a program than nonteaching hospitals (60% versus 17%) (150). A survey of 47 hospitals participating in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Project ICARE found that all hospitals reported having an antibiotic formulary, and 91% used at least one other antimicrobial control strategy (90). However, teaching hospitals were significantly more likely to apply controls on antimicrobial prescribing than nonteaching hospitals. Thus, teaching hospitals appear more likely to apply stringent antimicrobial control policies than nonteaching hospitals. This may be because of a higher perceived need for antimicrobial control, greater availability of resources and staff to administer the programs, or a lesser need to accommodate physician autonomy in teaching compared to nonteaching hospitals.

ROLES OF INDIVIDUALS IN ANTIMICROBIAL STEWARDSHIP PROGRAMS

Infectious Diseases Physicians

Essential to a successful antimicrobial stewardship program is the presence of at least one infectious diseases-trained physician who dedicates a portion of their time to the design, implementation, and function of the program. Supervision by an infectious diseases physician is necessary to ensure that therapeutic guidelines, antimicrobial restriction policies, or other measures are based on the best evidence and practice and will not put patients at risk. Having the program led by an infectious diseases specialist may also lend the program legitimacy among physicians practicing at the hospital, and reduce the chance of the program simply being seen as a pharmacy-driven cost-savings scheme.

Although most (89%) infectious diseases physicians surveyed by Sunenshine et al. agreed that infectious diseases consultants should be involved in the approval process for restricted antimicrobial agents, there are significant barriers to this practice (150). First, the time involved in directly administering an intensive stewardship program (such as one requiring authorization for restricted antimicrobials) at a medium- or large-sized hospital may leave little time for clinical consultations, research, or teaching. Thus, responsibility for the daily activities of in such a program would either have to be shared among physicians or delegated to other personnel such as infectious diseases fellows in training or hospital or clinical pharmacists.

Smaller, nonteaching hospitals without these personnel may not feel they can support such a program. However, LaRocca reported that in their 120-bed, nonteaching, community hospital, an antibiotic support team led by an infectious diseases specialist and a clinical pharmacist performing antimicrobial review 3 days per week was able to demonstrate a $177,000 reduction in antmicrobial costs in a year (87). This program required 8 to 12 h per week of the infectious diseases specialist's time; assuming that the clinical pharmacist's contribution to the program was also part-time, significant cost savings to the hospital likely would have been realized over and above personnel costs. Thus, infectious diseases physicians may be able to create opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship activities in smaller hospitals as well.

Even in larger hospitals, reimbursement of infectious diseases physicians performing antimicrobial stewardship activities may be poor, representing another barrier. Only 18% of infectious diseases physicians working in hospitals with restriction programs reported that the hospital directly reimbursed physicians for their participation (150). This may represent a lost opportunity for hospitals, since cost savings from most published antimicrobial stewardship programs are significant and would likely exceed any partial salary offsets for a physician's time, especially when other personnel are available to perform the day-to-day functions of the program (80).

Another concern in implementing antimicrobial stewardship programs, especially those using restrictive strategies, has been the risk of antagonizing physician colleagues that infectious diseases specialists rely on for consultations. In Sunenshine's survey, 45% of infectious diseases physicians believed that participation in stewardship programs would possibly lead to a loss of requests for consultation (150). This belief was more frequent among physicians practicing in nonteaching (57%) than teaching (42%) hospitals. It is not clear whether this concern is valid based on existing antimicrobial restriction programs, as none have specifically measured consultation volume. Early involvement of physician leaders in other specialties during the development of antimicrobial stewardship programs may aid in obtaining physician buy-in. Identification of control of antimicrobial resistance as a key goal by hospital administration (see below) is also important in supporting the efforts of antimicrobial stewardship teams.

Clinical and Hospital Pharmacists

The origin of many antimicrobial stewardship programs as cost-saving measures initiated by the pharmacy department has put pharmacists at the forefront of many antimicrobial stewardship programs. Pharmacists often act as the effector arms for antimicrobial stewardship programs (149). They are well positioned for this effort because of their role in processing medication orders and their familiarity with the hospital formulary. Different hospital-based pharmacists may play different roles in antimicrobial stewardship programs. Pharmacists whose primary role is in processing medication orders and dispensing drugs in the hospital may note when restricted antimicrobials are ordered and notify the prescriber that authorization is required. They may also flag orders for review by infectious diseases specialists, in addition to their usual role in assuring proper dosing and safety. However, the broad responsibilities of these pharmacists generally do not allow adequate time for a comprehensive review of antimicrobial therapy. In addition, these pharmacists may not have adequate training in infectious diseases to feel comfortable providing recommendations for complex cases. Thus, having a clinical pharmacist with specialized training in infectious diseases dedicated full- or part-time to the administration of the antimicrobial stewardship program is increasingly common.

Formal training programs in infectious diseases for clinical pharmacists are expanding and becoming increasingly standardized. In the United States, training typically involves at least two years of postgraduate work (residency and/or fellowship), with at least one year concentrating on infectious diseases pharmacotherapy. Pharmacists with such training gain expertise in microbiology, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antimicrobials, pharmacotherapy of infections, and antimicrobial management. When involved in antimicrobial stewardship programs, clinical pharmacist specialists in infectious diseases share responsibility for a number of activities. These include development of guidelines for antimicrobial use, education of physicians and other health care professionals, review of hospital antimicrobial orders with feedback to providers, administration of restrictive strategies, pharmacokinetic consultation, and research on program outcomes (81).

In 1997, the Infectious Diseases Society of America issued a position statement expressing concern over the provision of therapeutic recommendations by hospital pharmacists (77). Certainly no pharmacist, regardless of their level of training, is qualified to practice medicine, and decisions concerning interpretation of radiographic, physical examination, and other diagnostic findings should be referred to infectious diseases physicians. However, properly trained clinical pharmacists acting in concert with their physician colleagues can make substantial impact on patient care in a variety of practice areas, including infectious diseases (27, 54, 91).

Gross et al. implemented an antimicrobial stewardship program at their teaching hospital, wherein physicians desiring to use restricted antimicrobials were required to receive approval by paging a dedicated beeper (66). A clinical pharmacist with training in infectious diseases, supported as needed by a senior infectious diseases physician, staffed the beeper on weekdays, while the infectious diseases physician fellows in training carried the beeper on nights and weekends. The study compared appropriateness of therapy as well as clinical outcomes resulting from recommendations made by the pharmacist or the fellows. A significantly greater percentage of recommendations made by the pharmacist (76%) were judged appropriate by blinded physician review than those made by the fellows (44%). Furthermore, patients whose physicians received recommendations from the pharmacist were significantly more likely to achieve clinical or microbiological cure (49%) than those who received recommendations from the infectious diseases fellows (35%). Because of the need for midlevel practitioners to enforce antimicrobial stewardship policies, the next decades will likely see clinical pharmacists as increasingly important partners to infectious diseases physicians in implementation of antimicrobial stewardship programs (159).

Clinical Microbiologists

The clinical microbiology laboratory is a key component in the function of antimicrobial stewardship programs. Summary data on antimicrobial resistance rates allow the antimicrobial stewardship team to determine the current burden of antimicrobial resistance in the hospital, facilitating decisions as to which antimicrobials to target for restriction or review. Ideally, resistance data should be able to be sliced in multiple ways to answer more sophisticated questions as to the nature of resistance in the institution. For example, if the laboratory processes samples from outpatient clinics, exclusion of these isolates will give a better sense of the true state of resistance within the hospital. Preparation of antibiograms specific to certain patient care areas, especially intensive care units, may allow identification of local problems and focused antimicrobial stewardship and infection control efforts (148). Also, having resistance data available on a monthly or quarterly basis allows closer tracking of trends and facilitates well-designed studies of interventions (see Study Design, below).

Dissemination of antibiograms to clinicians may allow better selection of empirical therapy based on local susceptibility patterns. However, clinicians must be wary of overinterpreting results from antibiograms when the absolute number of isolates is very small. This may be especially problematic for rare organisms or when susceptibilities are reported for a specific unit (e.g., a single intensive care unit) or over a short time period (e.g., monthly). The Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (formerly the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards) has published a guidance document (M39-A) for the proper construction and reporting of antibiograms (116). Antibiograms may be distributed as printed cards, as part of institutional handbooks on antimicrobial therapy, or on the institutional intranet.

Timely and accurate reporting of microbiology susceptibility test results allows selection of more appropriate and focused therapy, and may help reduce broad-spectrum antimicrobial use (22, 153). The microbiology laboratory can also encourage focused antimicrobial selection by cascade reporting of susceptibility results: depending on the organism's susceptibility, only certain (usually narrower-spectrum) antimicrobials are reported. Hidden susceptibility results should be made available upon request in cases where toxicity, allergy, coinfections, or other considerations make first-line therapy suboptimal.

A number of challenges face clinical microbiologists today, including a surge in new biotechnology-based tests, increasing centralization of laboratory services, and an increasing shortage of skilled workers. Because of the importance of the clinical microbiology laboratory to implementation of antimicrobial stewardship, funding for antimicrobial stewardship programs should include compensation for the microbiology laboratory's contributions to the program. At the same time, the antimicrobial stewardship program's educational initiatives should incorporate recommendations for proper culturing and submission of tests, which may improve the use of laboratory resources and result in cost savings to the lab (9, 31).

Infection Control Staff and Hospital Epidemiologists

The problem of spread of antimicrobial-resistant organisms within hospitals has long been a concern of infection control professionals. While some resistant organisms have primarily been thought to be infection control problems and others antibiotic-use problems, an absolute distinction is artificial and both transmission and selection play important roles in the spread of antimicrobial resistance (133, 139). For instance, the proper method of control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in hospitals is a contentious issue within the infection control community, with conflicting data as to the effectiveness of stringent infection control measures (17, 34, 45). However, a number of studies have suggested that the quantity of antimicrobial usage is significantly associated with methicillin-resistant S. aureus rates, indicating that studies may need to control for antimicrobial use and infection control professionals should consider the effect of antimicrobial use in their institutions (111).

There are a number of avenues for collaboration between infection control and antimicrobial stewardship programs. Infection control staff gather highly detailed data on nosocomial infections which may assist in the antimicrobial stewardship team's evaluation of the outcomes of their strategies. Hospital epidemiologists have the expertise in surveillance and study design to lend to efforts studying the effect of antimicrobial stewardship measures. In turn, antimicrobial stewardship programs may be able to assist in efforts to control outbreaks by focused monitoring and/or restriction of antimicrobials in the targeted units. Any antimicrobial stewardship program should either be fully integrated with or work closely with a hospital's infection control program; such collaboration has the opportunity to synergistically reduce antimicrobial resistance and improve patient outcomes.

Hospital Administrators

None of the efforts of infectious diseases physicians, pharmacists, microbiologists, or infection control practitioners to establish an antimicrobial stewardship program are likely to be successful without at least passive endorsement by hospital leadership (61). Program funding, institutional policy, and physician autonomy are core issues in the development of antimicrobial stewardship programs that must be addressed by hospital administration. Without adequate support from hospital leadership, program funding will be inadequate or inconsistent since the programs do not generate revenue (although they may result in significant cost savings). And if hospital leadership is not publicly committed to the program, recalcitrant prescribers may thwart attempts to improve antimicrobial use without fear of sanction.

Advocates of antimicrobial stewardship programs might do well to learn from the recent surge in patient safety initiatives at hospitals, spurred by the Institute of Medicine's 1999 report on adverse drug events (78). Many institutions have made large investments in new technology and personnel in an effort to reduce medication errors (157). Highlighting the adverse effects of antimicrobial resistance and nosocomial infections on patient outcomes may secure fresh commitments from hospital executives, or at least allow antimicrobial stewardship programs to piggyback onto newly funded patient safety initiatives (56).

METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES

Outcome Measurements

The choice of outcome variables in studies of antimicrobial stewardship programs varies widely, depending on program goals, study design, study duration, and measurement capabilities. The change in antimicrobial usage is the most common outcome measured in studies of stewardship programs. Common outcome variables related to antimicrobial usage include quantity of total antimicrobial use, quantity of targeted antimicrobial use, duration of therapy, percentage of oral versus intravenous drug administration, and antimicrobial drug expenditures. Expenditures for antimicrobials are often measured to demonstrate the cost savings (or at least cost neutrality) associated with antimicrobial stewardship programs. The proportion of appropriate antimicrobial use may also be measured, usually with criteria that vary from study to study. Measurement of antimicrobial usage may be performed from patient charts or as aggregate antimicrobial use (e.g., in defined daily doses per 1,000 patient days) from billing or purchasing data. While improvement in antimicrobial usage (either a decrease in overall usage, decrease in use of targeted antimicrobials, or an increase in appropriate therapy) is a worthy endpoint in and of itself, acceptance of antimicrobial stewardship programs by a broader audience likely will be contingent on demonstration of positive effects on clinical and microbiological outcomes.

Clinical criteria are often included in studies to demonstrate that a change in antimicrobial usage does not have a deleterious effect on patient outcomes. Common clinical outcomes include all-cause mortality, infection-related mortality, duration of hospitalization, and rates of readmission. Clinical cure or improvement may also be measured, with or without precise definition of the terms. In general, studies have found no difference or a slight improvement in clinical outcomes with antimicrobial management programs (as discussed below). However, studies may be insufficiently powered to demonstrate either a benefit or detriment to infrequent clinical outcomes (all-cause or infection-related mortality).

Microbiologic outcomes include the percentage of organisms resistant to a certain antimicrobial, percentage of multidrug-resistant organisms, or number of infections due to specified organisms. In spite of the known association between antimicrobial use and resistance, inferring improvement in microbiological outcomes from studies that only demonstrate a reduction in antimicrobial usage is hazardous (124). Differences in potential for selection of resistance between antimicrobials, impact of duration of therapy and dosage changes, and secular trends in resistance may impact resistance rates to a greater extent than changes in absolute quantities of antimicrobial drug use. Thus, microbiologic outcomes should be measured explicitly. Data on microbiological outcomes may be obtained from patient records, infection control practitioners, or the clinical microbiology laboratory. Some authors suggest that the rate of isolation of resistant organisms is a more appropriate measure of the burden of antimicrobial resistance than the proportion of resistant organisms; efforts should be made to measure this outcome as well, when feasible (113, 143).

Study Design

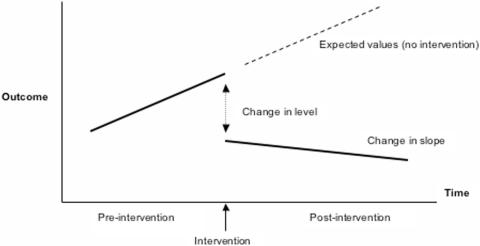

In a recent review of 306 studies of interventions to improve antimicrobial prescribing in hospitals, 70% did not meet the minimum criteria of the Cochrane Collaboration's Effective Practice and Organization of Care Group (131). The most commonly excluded studies were those using uncontrolled before-and-after designs (46%) or inadequate interrupted time series analysis (24%). Use of these flawed methodologies may overestimate or underestimate the effect of interventions on outcomes (such as volume of antimicrobial use or percentage of resistant organisms). For some studies this bias was so severe as to alter the conclusions when appropriate analysis was performed. The authors of the review advocated analysis using interrupted time series with segmented regression (Fig. 1), a method of analysis applied to before-and-after quasi-experimental study designs. This methodology requires measurements at multiple time points both before and after the intervention, allowing evaluation of both the immediate change due to the intervention (change in level) and the sustained changes (change in slope). These considerations are likely to be especially important in measuring effects on antimicrobial use and bacterial resistance, both of which are likely to increase in the absence of control measures (positive slope). Thus, even an intervention that produces minimal change in level may have significant impact if the rate of increase can be reduced.

FIG. 1.

Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series data. (Adapted from reference 3a with permission of the publisher.)

The primary limitation to this study design is the long period of time required to obtain sufficient pre- and postintervention data points for statistical analysis. The authors suggest 24 data points before and after the intervention; if data are captured on a monthly basis, this requires either a very long time horizon for the study or the ability to collect useful data retrospectively. Although a few randomized studies of the impact of antimicrobial stewardship interventions have been published, quasi-experimental designs are much more common in this area. Thus, investigators should familiarize themselves with the fundamentals of these types of studies (excellently reviewed in reference 71), as well as the application of techniques such as time series analysis to the study results.

Effect of Multiple Interventions

Analysis of the efficacy of interventions to improve antimicrobial use is complicated by the simultaneous employment of multiple different strategies by antimicrobial stewardship programs (121), making it difficult to compare the effect of different strategies and conclude which is most effective. Some of the strategies may also have interacting effects, such that they are more or less effective in combination. Absent large, multicenter trials comparing different intervention strategies in different arms, this complication is likely to be a permanent fixture in analysis of antimicrobial stewardship programs.

Publication Bias

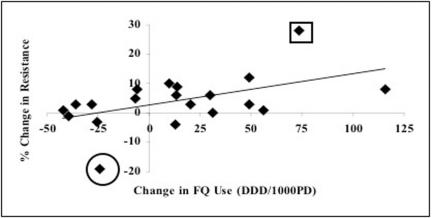

Publication bias is a concern when evaluating the effectiveness of antimicrobial stewardship programs. As with any scientific endeavor, there is a perception that positive results are more noteworthy and manuscripts are more likely to be submitted and accepted for publication if the report demonstrates positive results (Fig. 2). Since the funding of many antimicrobial stewardship programs is contingent upon demonstration of cost-effectiveness (usually through savings in antimicrobial acquisition costs), programs that do not achieve positive results may be discontinued. The experience at such institutions is not likely to be published. Thus, it is unclear whether antimicrobial stewardship programs are generally effective in controlling antimicrobial use (and sometimes in improving resistance and clinical outcomes), or whether the published literature only reflects the experience of successful programs. Such questions are important as institutions are deciding whether to implement an antimicrobial stewardship program and what specific strategies to incorporate. The careful study and publication of the results of implementations of antimicrobial stewardship strategies, successful or unsuccessful, should be encouraged.

FIG. 2.

Illustration of possibility of publication bias in studies of antimicrobial use and resistance. Linear least-squares regression of changes in fluoroquinolone use on the changes in proportion of fluoroquinolone-resistant P. aeruginosa in 19 hospitals between 2000 and 2003 (authors' unpublished data). Eight hospitals decreased fluoroquinolone (FQ) use, but in only one hospital was there an important decline in resistance (circled marker). Likewise, most hospitals increased quinolone use but only one had a marked increase in rates of resistance (squared marker). These outlying observations may be more likely to be published and would exaggerate the modest relationship between changes in use and resistance noted across all hospitals. DDD/1000PD, defined daily doses per 1,000 patient-days.

CLASSIFICATION OF PROGRAMS AND REVIEW OF SELECTED STUDIES

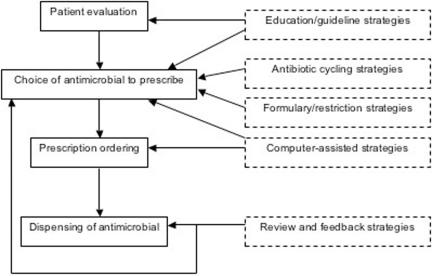

Antimicrobial stewardship programs may be generally classified according to the strategy by which they seek to affect antimicrobial use. However, as noted, many programs use a combination of such strategies. Thus, strict classification of studies of antimicrobial stewardship programs is not always possible, and previous reviews have used different methods of classification (80, 120, 121). Table 1 provides brief summaries of the strategies according to the classification we will use here, while Fig. 3 illustrates at what point in the process of antimicrobial prescribing the different strategies act. When multiple strategies are employed in a single study, we will classify them according to the most active strategy. Below, we describe the general strategies and provide representative examples. As the Cochrane Collaboration's Effective Practice and Organization of Care Group is currently preparing a systematic review and meta-analysis of antimicrobial stewardship programs, we will not attempt to survey the entire literature (32).

FIG. 3.

Antimicrobial prescribing process and antimicrobial stewardship strategies.

Education and Guideline Implementation Strategies

A key foundation in encouraging appropriate antimicrobial use in hospitals is defining what an institution considers appropriate antimicrobial use. Because of limited time to teach antimicrobial pharmacology and infectious diseases in the medical school curriculum, physicians often acquire their antimicrobial prescribing habits from the practice of their colleagues, the recommendations of antibiotic handbooks, and from information provided by representatives of the pharmaceutical industry (140). Information from these sources may vary widely and conflict with what is considered best practice at an institution. Although the vast majority of physicians recognize antimicrobial resistance as an important problem, most underestimate the true degree of antimicrobial resistance in their own institutions (58, 160). Physicians are primarily concerned with the effects of antimicrobials in the individual patients whose care they have been charged with; in a hypothetical case scenario, the risk of contributing to antimicrobial resistance was rated lowest among seven factors influencing a physician's choice of antimicrobial agent (107).

To counter these perceived conflicts in knowledge and practice, institutions may attempt to provide guidelines for antimicrobial use and educate clinicians regarding preferred antimicrobial therapy. This strategy attempts to influence providers' prescribing during their evaluation of the patient and selection of antimicrobial therapy (Fig. 3). The approaches taken vary widely, from posting copies of national guidelines on the institution's website to formulation of consensus local guidelines with academic detailing and prescriber feedback. Academic detailing refers to one-on-one educational sessions between an academic clinician educator (usually a physician or pharmacist) and the clinician targeted for education (146). Also referred to as reverse detailing or counterdetailing, this method co-opts the strategy of individualized attention used by pharmaceutical industry representatives (detailers). Prescriber feedback consists of providing data to clinicians regarding their prescribing habits, with comparisons to expected norms (e.g., guidelines) or to other prescribers in the same practice area.

Both academic detailing and prescriber feedback can be applied on a general level (e.g., an infectious diseases physician discussing new guidelines for febrile neutropenia with an oncologist and reviewing antimicrobial use on the hematology/oncology floor from the last year) or a patient-specific level (e.g., a pharmacist calling a physician to discuss the choice of a particular antimicrobial and encouraging selection of an alternative in accordance with guidelines). We will consider the first, more general approach in this section and address the latter approach in a following section (review and feedback strategies).

Reviews of studies of provider behavior change suggest that active, personalized interventions such as academic detailing are more effective than passive dissemination of information at eliciting desired changes (64, 65). Many studies examining the effect of educational interventions on antimicrobial use have been performed with physicians in ambulatory care practice. Those that compared provision of printed educational materials to more active methods such as academic detailing generally found improved guideline compliance in the active intervention group (6, 62, 141). In the hospital setting, passive interventions involve measures such as providing posters, handouts, or printed guidebooks, or minimally interactive educational sessions such as Grand Rounds.

In a study from the Netherlands, the impact of dissemination of national consensus guidelines for treatment of bacterial meningitis via a printed handbook was studied (154). After the introduction of the guidelines, only 33% of cases of bacterial meningitis nationwide were treated in accordance with the recommendations. Because there was no data on compliance prior to introduction of the guideline, it is unclear whether even this low rate of compliance represented an improvement. Girotti et al. compared the impact of two interventions on compliance with recommendations for perioperative antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery (59). Physicians on three surgical services received a printed handbook with recommendations for prophylaxis, while on two other surgical services, an order form for antimicrobial prophylaxis was introduced. The percentage of orders that represented appropriate prophylaxis was measured before and after the interventions. Improvement in appropriateness was marginal in the services provided the handbook (11% to 18%, P = 0.06), but was impressive in the services required to use the antimicrobial order form (17% to 78%, P < 0.01).

The impact of voluntary compliance to a guideline for use of third-generation cephalosporins was evaluated by Bamberger and Dahl (7). After addition of ceftazidime and ceftriaxone to the hospital's formulary, guidelines for use were created and distributed to all physicians at a teaching hospital. Compliance with the guideline's recommendations in the first 6 months was only 24%. Given poor voluntary compliance with the guidelines, a restriction strategy requiring written justification before dispensing of subsequent doses by the pharmacy was instituted. During the 6-month period that this strategy was in place, 85% of courses of cephalosporin therapy conformed to the guidelines. Sensitivity to third-generation cephalosporins among Enterobacter cloacae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa improved after voluntary compliance was abandoned and the more restrictive measures were put in place.

One factor that may influence the acceptance of guidelines, especially when their implementation is largely through passive methods, is the degree of local input into their development (19). Compliance with national guidelines is often poor even when the recommendations are for common conditions and are promulgated by well-known organizations (such as the community-acquired pneumonia guidelines of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America) (47, 151). This may be due to appropriate variations in practice due to local circumstances, lack of knowledge of guidelines, or because of perceived threats to physicians' autonomy.

Having local opinion leaders collaborate on the development of institutional guidelines (or the adaptation of national guidelines to fit local circumstances) may improve compliance by promoting ownership (61). When a university hospital in the Netherlands revised its guidelines for antimicrobial therapy, it relied heavily on consultation with physicians in the various specialties to ensure agreement between departmental policies and the antimicrobial guidelines (110). When the effect of the introduction of the revised guidelines was measured using segmented regression analysis, a statistically significant increase in compliance with guidelines was noted (67% to 81%). Subsequent academic detailing had little additional effect (increase to 86% compliance), possibly because of the intensive collaboration during guideline development.

Local involvement in guideline development may be especially important in teaching hospitals where the influence of senior attending physicians on trainees' prescribing habits may be significant, and thus the house staff's compliance with guidelines may be poor without buy-in from superiors (109). Everitt et al. demonstrated that an educational intervention targeted towards authoritative senior surgery department members had an astounding impact on the choice of antimicrobial for surgical prophylaxis during caesarian section (44). In combination with an antimicrobial order form, this top-down approach increased the prescribing of cefazolin (considered the appropriate agent) for surgical prophylaxis from 3% to almost 100%.

Although there is no shortage of evidence-based practice guidelines regarding antimicrobial use, including those addressing the problem of antimicrobial resistance, the mere publication of these guidelines is insufficient to significantly impact antimicrobial prescribing patterns. Adaptation of national guidelines to local circumstances, collaboration with hospital specialists, broad dissemination of guidelines in easily accessible forms (print and/or electronic), and active educational methods such as academic detailing (targeted to the most influential clinicians first), are required to increase the chances of the adoption of recommendations in clinical practice. Even then, education- and guideline-based strategies should be considered primarily as a starting point for antimicrobial stewardship programs. Because voluntary guideline compliance is often poor, more active efforts are often required to reinforce proper prescribing habits and ensure appropriate therapy.

Formulary and Restriction Strategies

Because of resistance to compliance with guidelines for antimicrobial usage, external control over clinicians' prescribing of these drugs may be implemented. This commonly takes the form of establishment of an antimicrobial formulary, such that only selected antimicrobial agents are freely dispensed by the pharmacy. Other agents may only be available if certain criteria for use are met (criterion-monitored strategies), if approval for use is obtained from a specialist in infectious diseases (prior-authorization strategies), or may not be available at all (closed-formulary strategies). Having an antimicrobial formulary may not represent an effective strategy for control of antimicrobial use if it serves only to restrict the choice of antimicrobial to one of a number of very similar agents. For example, although using cefazolin instead of cephalothin (or nafcillin instead of oxacillin) represents a formulary decision, such a policy is unlikely to have significant positive impact on antimicrobial usage or outcomes (except possibly for financial outcomes). The goal of restriction-based policies may be a reduction in drug costs to the hospital (through restriction of more-expensive agents), a reduction in the growth of antimicrobial resistance (through restriction of agents considered to be more likely to contribute to resistance), or both. The nature and degree of restriction and specific agents targeted may differ between stewardship programs.

The introduction of the additional step of documenting justification or calling for authorization of an antimicrobial drug may be sufficient in and of itself to reduce demand for targeted antimicrobial agents. McGowan and Finland described an early program at Boston City Hospital, where a number of antimicrobial agents were restricted and required telephone authorization from an infectious diseases physician before being dispensed (104, 105). However, if the requesting physician did not agree with the infectious diseases consultant's suggestions for alternative therapy, the requested drug was dispensed. Thus, the intervention was more of an educational effort than a true restriction. Nevertheless, the authors observed a reduction in use of targeted agents after introduction of the program, as well as lower use of targeted agents in comparison to similar hospitals.

In another early program, a request for restricted agents triggered an automatic infectious diseases consultation (35). The recommendations of the consultant were not binding; however, the investigators found that the recommendations were followed in approximately 90% of cases. Drug costs decreased at the hospital by 31%, primarily due to reductions in cephalosporin use. In a study by White et al., final authority to dispense any of a number of restricted antimicrobials rested with the infectious diseases attending physician on call (161). According to the investigators, although approval was granted in most cases, significant reductions in the use of targeted antimicrobial agents were observed over a 6-month period. The authors also compared antimicrobial susceptibility data and clinical outcomes between the periods before and after initiation of the restriction program. The antimicrobial susceptibilities among gram-negative pathogens to both restricted and nonrestricted agents increased significantly after implementation of the restriction program. Clinical outcomes (overall 30-day survival, length of stay, acquisition of bacteremia) were similar in the two time periods, with some trends towards improved survival in patients with infections during the period of antimicrobial restriction.

Thus, although restriction programs may be relatively porous in terms of allowing requests for restricted antimicrobials to be approved, they can still effect substantial reductions in antimicrobial use, as well as leading to improvements in susceptibility. This is likely due to the effort involved in contacting the infectious diseases specialist for use of a restricted agent, when a similar nonrestricted agent would not require extra effort, and the educational interaction between the infectious diseases specialist and the requesting clinician. Besides denying or approving the request for the antimicrobial, the infectious diseases specialist can offer advice on proper dosing, administration and duration; adverse effects and drug interactions; interpretation of microbiological tests; and further diagnostic procedures. The interaction thus becomes a mini-academic detailing session, which is more likely to be remembered by the clinician because of its patient-specific nature. A study in which requests for restricted antimicrobials were referred to a clinical pharmacist specialist demonstrated a cost savings of greater than $68,000, despite the pharmacist's approving 83% of all requests (24). This number likely underestimates the true cost savings, since it only examined the difference between the cost of the restricted antimicrobials that were ordered and those agents that were actually dispensed; this analysis does not account for any learning effect leading to a decrease in the ordering of restricted antimicrobials.

Some programs provide different levels of restriction of antimicrobials. Woodward et al. described the program at Barnes-Jewish hospital with a three-tiered classification system of antimicrobial agents (163). Unrestricted agents could be dispensed by the pharmacy for any indication, although the dosing ranges may be restricted. Controlled agents could be dispensed for a limited period of time without authorization (generally 24 or 72 h); after this time period, authorization by an infectious diseases clinician was required. Restricted agents required approval before dispensing of any doses. Using this approach, a significant reduction in expenditures for controlled and restricted agents was effected, while the number of patients with bacteremia receiving appropriate therapy remained constant. Other programs may allow targeted antimicrobials to be used for certain documented indications (e.g., ceftriaxone for bacterial meningitis), or by individual medical services (e.g., a bone marrow transplant unit), but not for general use. The classification of antimicrobials to different levels of restriction should be tailored to the individual institution's patient population, prescribing patterns, and resistance issues.

Historically, agents have been targeted for restriction based on their cost relative to similar therapies. Restricted agents may have benefits in certain situations (such as the reduced toxicity of lipid-based amphotericin products or the broader spectrum of amikacin relative to other aminoglycosides), but their higher acquisition costs are prohibitive for routine use. Restriction programs may also be based on the potential of antimicrobials to select for certain resistant organisms. The classic example of this approach is the study by Rahal et al.; in response to an outbreak of an extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella sp., a hospital instituted strict restrictions on all cephalosporin use (130). Subsequently, the incidence of resistant Klebsiella infection decreased significantly. However, due to an increase in use of imipenem/cilastatin, the incidence of imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa increased.

A similar pattern was also seen in another study wherein heavy use of piperacillin-tazobactam was associated with high rates of piperacillin-resistant Pseudomonas infections in a medical-surgical intensive care unit (1). Substitution of piperacillin-tazobactam with imipenem led to a decrease in resistance piperacillin resistance in Pseudomonas infections, but an increase in imipenem resistance. This phenomenon has been referred to as “squeezing the balloon”; changing from the use of one agent to another may reduce resistance to the first drug, but increase resistance to the second drug (21). A challenge to restriction-based strategies is to avoid substituting one resistance problem for another in such a fashion.

Recently there has been a trend towards restricting cephalosporin usage and increasing utilization of β-lactamase inhibitor combinations (such as piperacillin-tazobactam and ampicillin-sulbactam). This approach has been supported by studies demonstrating a protective effect of administration of piperacillin-tazobactam against infection by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing organisms and vancomycin-resistant enterococci, in comparison to cephalosporin administration (125, 135). Landman et al. restricted the use of third-generation cephalosporins, vancomycin, and clindamycin in their institution and encouraged use of piperacillin-tazobactam and ampicillin-sulbactam (86). Analysis of monthly incidence rates of resistant pathogens reported a significant decrease in isolation of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as well as ceftazidime-resistant Klebsiella spp., although the proportion of resistant Acinetobacter isolates increased.

Other hospitals have also observed a decrease in extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing organisms after adding piperacillin-tazobactam and restricting ceftazidime (85, 134). Studies have also documented reductions in the rates of vancomycin-resistant enterococci and Clostridium difficile after restriction of cephalosporins and replacement with β-lactamase inhibitors (103, 119, 129, 162), although this has not been seen in all studies (89). If the success of this approach is validated by future studies (and is not a result of publication bias), it may be the beginning of a solid evidence base to inform decisions as to which antimicrobials are most appropriate for restriction.

Review and Feedback Strategies

Although restriction strategies may be effective at channeling use of antimicrobials towards preferable agents, there are limitations to the approach. There may be inadequate personnel or institutional commitment for a restrictive approach. Importantly, restriction strategies do not consider the appropriateness of use of nonrestricted antimicrobials, which make up the vast majority of antimicrobials used in the hospital. To optimize the use of nonrestricted antimicrobials, or to manage the use of targeted antimicrobials in institutions where restriction strategies are not in place, programs built around antimicrobial review and feedback may be instituted. Such a program involves the retrospective (hours to days) review of antimicrobial orders; if an order appears to be inappropriate, a member of the antimicrobial management team contacts the prescriber in an effort to optimize therapy.

A number of studies reporting experience with this approach have been published. Most of them have suboptimal study designs, measuring mean levels of an outcome (drug prescribing, drug cost, resistance) before and after program implementation, as opposed to using segmented regression and time series analysis. However, some studies did have other methodologic strengths, such as randomization. Fraser et al. performed a randomized trial of an intervention program in a 600-bed teaching hospital and evaluated clinical and microbiologic response as well as costs for antimicrobials across the study arms (48). Patients receiving one of 10 target antimicrobials for greater than 3 days were randomized to the intervention arm or to the standard of care. The intervention consisted of a having a clinical pharmacist and infectious diseases fellow review the medical records of patients receiving the target antimicrobials. If there was agreement on a need to optimize antimicrobial therapy (changing or stopping therapy, switching to oral regimen, or an alternative dosage), a nonpermanent chart note was written; 85% of suggestions were implemented. There was no significant difference in clinical or microbiological outcomes between the groups, but total antimicrobial costs were significantly lower in the intervention arm; yearly savings were estimated at $390,000.

Another study performed in a 275-bed community hospital randomized patients receiving potentially inappropriate antimicrobials to standard care or to have a multidisciplinary team (an infectious diseases physician and clinical pharmacist) provide suggestions for therapy via a chart note (67). Eighty-nine percent of suggestions provided in the intervention arm were accepted. The median length of stay was shorter by 3 days in the intervention arm than the control arm, and an overall cost reduction of $2,642 per intervention was estimated. Other clinical and microbiologic outcomes were similar between the two groups.

A third randomized trial of a highly targeted intervention was reported by Solomon et al. (145). Their group at the Brigham and Women's hospital randomized inpatient clinical services (e.g., medicine, oncology), assigning nine services to the intervention arm and eight to the control arm. All orders for levofloxacin or ceftazidime that were written by physicians in the intervention group were reviewed for adherence to hospital guidelines for use. If an order was not in compliance with the guidelines, a member of the antimicrobial stewardship team (infectious diseases physician or clinical pharmacist) contacted the prescriber to suggest alternative therapy. The duration of inappropriate therapy of the target antimicrobials was reduced by approximately 40% in the intervention group relative to the control group, while clinical outcomes were similar between the groups.

Before-and-after designs have been more commonly used to determine the impact of review and feedback programs. Carling et al. used a time series approach with three years of preintervention and seven years of postintervention data to analyze the results of their antimicrobial stewardship program (26). The program employed a clinical pharmacist and an infectious diseases physician to review orders for broad-spectrum antimicrobials and provide feedback to prescribers. This strategy led to a reduction in use of third-generation cephalosporins and aztreonam and a stable (nonincreasing) rate of use of fluoroquinolones and imipenem over the study period. Rates of Clostridium difficile infection and infections with drug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, which had been increasing before the intervention, dropped and remained stable after implementation of the program. Programs specifically targeting the use of vancomycin (68) and vancomycin and fluoroquinolones (46), using pharmacy personnel to provide feedback, have documented reductions in the use of these agents and improved compliance with guidelines after program intervention.

Some programs have used a review and feedback strategy but also empowered the antimicrobial stewardship personnel to change therapy or require an infectious diseases consultation if a conflict arises. At a 731-bed teaching hospital in North Carolina, a program incorporating restriction and review was implemented (33). Restricted antimicrobials required prior approval by an infectious diseases physician, whereas controlled agents were freely dispensed but reviewed within 48 h by a clinical pharmacist. The clinical pharmacist provided recommendations via a chart note to change or, if necessary, discontinue the agent to the primary team. If no action (acceptance or rejection) was taken within 24 h, the pharmacist would write the recommendations as a chart order. Only 8% of recommendations were rejected, leading to active or default acceptance of 92% of recommendations. This program led to a significant reduction in total and targeted antimicrobial use, although there was no significant change in antimicrobial susceptibilities.

Bantar et al. reported on the stepwise implementation of a stewardship program in a 250-bed hospital in Argentina (8). The initial phases of the program involved educational interventions and the introduction of an antimicrobial order form, followed by prescribing review by the antimicrobial stewardship team, which had the authority to modify orders considered to be inappropriate. Approximately 25% of antimicrobial orders were modified during the period this policy was in place. Significant reductions in antimicrobial use were documented over the course of the study, along with reductions in resistance in some organisms. Finally, Gentry et al. reported on a program's transition from a restriction-based approach to a review and feedback approach implemented by a clinical pharmacist specialist (55). All orders for restricted antimicrobials were dispensed but were reviewed within 24 to 48 h by the pharmacist, who made recommendations as appropriate. If a conflict arose, the pharmacist could request formal consultation from the infectious diseases service. Approximately 50% of the courses of therapy were modified upon review, either with discontinuation of the restricted agent or dosage modification. Both antimicrobial costs and mean length of stay decreased significantly after program implementation.

Review and feedback strategies may be especially important in streamlining antimicrobial use. Inappropriate or delayed empirical antimicrobial therapy has been associated with increased mortality in a number of recent studies (76, 84, 93, 95, 98, 99). Patients infected with pathogens that are frequently resistant (e.g., S. aureus and P. aeruginosa) are more likely to receive inappropriate therapy (82, 84, 99); thus, as the incidence of resistance in hospitals increases, a greater number of patients are at risk for the adverse sequelae of inappropriate therapy. This realization has led to the advocacy of early, broad-spectrum empirical antimicrobial therapy for a number of hospital infections. For example, recent American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for hospital-acquired pneumonia recommend three-drug combination therapy (an antipseudomonal beta-lactam, an aminoglycoside or fluoroquinolone, and vancomycin or linezolid) for empirical therapy in patients with late-onset pneumonia (2). This approach reduces the risk of a patient's receiving inadequate therapy; however, administration of multiple broad-spectrum agents may increase the risk of development of resistance in the patient's (and the hospital's) bacterial flora. Thus, it is crucial for clinicians to change to the narrowest spectrum appropriate agent to treat the infecting pathogen once it is isolated and discontinue antimicrobials if infection is unlikely (122).

Although adherence to these two principles should be a fundamental tenet of medical practice, in reality a formal process (such as a guideline or critical pathway) or the contribution of the antimicrobial stewardship team reviewing such orders may be required. Otherwise, the desire to cover the patient may lead to endless courses of extremely broad-spectrum therapy, begetting more resistance, requiring even broader-spectrum therapy, and so on. Thus, streamlining, switch therapy, or deescalation strategies as a means of optimizing antimicrobial use deserve special mention as they relate to antimicrobial stewardship.

Schentag and colleagues gave special emphasis to streamlining in their description of their review and feedback-based program (142). Using a computer program to aid in their screening of microbiology data, they identified around 60 cases in a 7-month period where patients could have their antimicrobials discontinued due to negative culture results or changed to a different (usually narrower spectrum) regimen based on culture results. Direct cost savings of approximately $8,000 could be attributed to these interventions alone, but greater savings due to reduced toxicity, superinfections, and development of resistance are likely as well.

The group at Barnes-Jewish hospital performed a randomized, controlled trial of a policy for discontinuing antimicrobial therapy for ventilator-associated pneumonia (108). The critical care service initiated standard broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy for patients with suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia. In patients randomized to the intervention group, a physician or clinical pharmacist provided recommendations to the critical care team for discontinuing therapy based on predefined criteria suggesting the resolution or absence of infection. The control group did not receive recommendations and the service could discontinue therapy as they saw fit. Clinical outcomes were similar between the two groups, but the intervention group had a significantly shorter mean duration of antimicrobial therapy (6 days in the intervention group versus 8 days in the control group). Streamlining strategies, whether implemented by educational efforts or through antimicrobial review, thus offer a reasonable compromise between the need for appropriate empirical therapy and the need to preserve the effective life of our antimicrobial arsenal.

Computer-Assisted Strategies

The increasing computerization of the hospital environment offers new opportunities for programs to optimize antimicrobial use. These opportunities have primarily been associated with implementation of computerized physician order-entry systems in hospitals. The order-entry encounter can be designed to facilitate each of the antimicrobial stewardship strategies above. Educational strategies may be as simple as a link to the institution's guidelines for therapy, or as sophisticated as computerized expert systems that integrate patient-specific laboratory and microbiology data in devising a suggested therapeutic regimen. If a prescriber enters an order for a restricted agent, a list of formulary alternatives can be suggested, along with the pager number needed to obtain authorization. When an agent targeted for review is ordered, the data can be forwarded in real time or entered into a queue for later review by antimicrobial stewardship personnel.

At Brigham and Women's Hospital, where prescribers write orders via a computerized physician order-entry system, Shojania et al. randomly assigned half of prescribers to see a screen asking them to indicate a rationale for vancomycin therapy whenever the drug was ordered (144). Prescribers entered a rationale from one of the categories provided, which were derived from the Centers for Disease Control's guidelines for vancomycin use. If the patient was prescribed vancomycin, an additional screen was displayed after 72 h of vancomycin therapy requiring the prescriber to indicate their reason for continued therapy. Prescribers in the intervention group wrote significantly fewer orders for vancomycin, and segmented linear regression indicated that a significantly smaller percentage of all hospital patients received vancomycin after the intervention (even though only half of the prescribers received the intervention). Thus, a relatively soft educational intervention displaying criteria for antimicrobial use and adding a justification step to ordering antimicrobials can have a substantial effect at controlling prescribing.

An Australian hospital utilized a computer program when implementing a restriction policy for third-generation cephalosporins (136). Prescribers used a web-based system to choose from a list of approved indications for cefotaxime and ceftriaxone. For nonapproved indications, only 24 h of the drug could be dispensed without approval from the infectious diseases service. Total use of the targeted drugs decreased significantly, while the proportion of appropriate courses of therapy doubled than the preintervention period. Thus, computer-assisted programs may allow offloading of some of the burden involved in prior-approval systems, although prescribers may be able to game the system by entering an approved indication even if they intend to use the drug for another purpose (23).

Computer assistance may also aid in implementation of antimicrobial review strategies, as illustrated by a study by Glowacki et al. (60). These investigators created a list of potentially inappropriate antimicrobial combinations (e.g., those with overlapping spectra of activity) and performed daily queries of the hospital information system to determine if any patients were receiving these combinations. Those patients identified by the query had their regimens reviewed by a clinical pharmacist, who made recommendations for modification of therapy. Over a 3-month period, 137 inappropriate antimicrobial combinations were discovered, 134 of which were modified according to the pharmacist's recommendations, leading to a conservative estimate of $48,000 per year in cost savings. It is easy to imagine that such a system could be modified to also flag other potentially inappropriate regimens (e.g., drug-organism susceptibility mismatch, over- or underdosing), making these systems a valuable tool for antimicrobial review.

The most advanced programs integrate patient-specific data extracted from hospital information systems to provide tailored recommendations for therapy using rules-based criteria (expert systems). The choice of antimicrobial is guided by the results of the patient's cultures (for definitive therapy) or by hospital-specific resistance patterns (for empirical therapy). Information on the patient's height, weight, and renal function is incorporated in determining dosing recommendations, and contraindications such as allergies are automatically checked for. The group at the Latter-Day Saints Hospital in Utah has authored a number of studies on the use of their expert system decision-support tool for antimicrobial selection (42, 123). One study examined the effect of the introduction of the program into a 12-bed intensive care unit over a 12-month period (43). The program was integrated into the medical-information system and provided recommendations for therapy; physicians were not required to follow the recommendations but had to provide a rationale for their choice if they ordered a nonrecommended antimicrobial. In approximately half of all courses of therapy the physician followed the computer's recommendations. Compared to the 2-year preintervention period, in the intervention period fewer antimicrobials were used, the mean cost of antimicrobials decreased, fewer antimicrobial-related adverse drug events occurred, and fewer patients were treated with a drug to which their infecting organism was not susceptible. Moreover, within the intervention period, outcomes were improved if the physician followed the computer's suggested regimen rather than overriding the computer.

Institutions wishing to incorporate computer-assisted strategies into their antimicrobial stewardship programs may work with their hospital's information systems professionals to attempt to add these functions to their existing systems or choose from a number of commercially available systems that may be integrated into the hospital's information technology framework.

Antibiotic Cycling Strategies

In the 1980s, studies examining formulary substitution of aminoglycosides (amikacin for gentamicin and tobramycin) suggested a strategy of rotating antimicrobials might be effective in slowing the emergence of resistance to any one agent (57). These studies have led to the development of strategies utilizing the scheduled rotation of antimicrobials in order to minimize the emergence of bacterial resistance. These programs typically target gram-negative resistance (the cycled antimicrobials are those primarily active against gram-negative organisms) and are generally limited to the intensive care unit setting. Theoretically, during the periods when an antimicrobial is out of rotation and its use is minimal, resistance to that drug will decline. The idea is to reduce selective pressure to any one antimicrobial class by providing heterogeneity in drug use -in the case of cycling, temporal heterogeneity (by time period) rather than spatial (by patient) heterogeneity. The subject has been thoroughly reviewed elsewhere (49, 74, 79, 83, 102, 128) -in fact, the number of reviews of antibiotic cycling exceeds the number of well-designed studies on the subject (20).

By dictating exactly which antimicrobials are to be used during a given time period, this strategy is in principle the most restrictive of all approaches to antimicrobial stewardship. However, compliance with the cycling protocol may be low, for a number of reasons: physicians may ignore the protocol and prescribe off-cycle antimicrobials to their patients, allergies or toxicity may preclude administration of the on-cycle drug, and the final regimen may be tailored to culture results. In a preliminary report from a Centers for Disease Control-funded study of antibiotic cycling in an intensive care unit, less than half of total days of antimicrobial therapy were compliant with the cycling protocol (106). This was despite the presence of an intensive care unit clinical pharmacist who was empowered to switch empirical therapy to the correct on-cycle drug, and a policy encouraging the continuation of the on-cycle antimicrobial even if an isolated organism was susceptible to narrower-spectrum agents.