Abstract

Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes adhere dichotomously to the host receptors CD36 and chondroitin sulfate A (CSA). This dichotomy is associated with parasite sequestration to microvasculature beds (CD36) or placenta (CSA), leading to site-specific pathogenesis. Both properties are mediated by members of the variant P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP-1) family and reside on nonoverlapping domains of the molecule. To identify the molecular basis for the apparent dichotomy, we expressed various domains of PfEMP-1 individually or in combination and tested their binding properties. We found that the CD36-binding mode of the cysteine-rich interdomain region-1 (CIDR1) ablates the ability of the Duffy binding-like γ domain to bind CSA. In contrast, neither a non-CD36-binding CIDR1 nor an intercellular adhesion molecule 1 binding domain had any affect on CSA binding. Our findings point out that interactions between different domains of PfEMP-1 can alter the adhesion phenotype of infected erythrocytes and provide a molecular basis for the apparent dichotomy in adhesion. We suggest that the basis for the dichotomy is structural and that mutually exclusive conformations of PfEMP-1 are involved in binding to CD36 or CSA. Furthermore, we propose a model explaining the requirement for structural dichotomy between placental and nonplacental isolates.

Attachment of Plasmodium falciparum parasitized erythrocytes (PEs) to host endothelium or placenta is a property of all field isolates (1–3). This mechanism allows the parasite to avoid spleen-dependent killing (4) and enhances transmission to mosquitoes but also contributes to P. falciparum pathogenesis (5, 6). In high-transmission regions, protective clinical immunity to P. falciparum develops within the first years of life, making symptomatic malaria mainly a disease of young children (7, 8). However, pregnant women, especially during their first pregnancy (primigravidas), are susceptible to new infections and exhibit massive sequestration of PEs in the maternal circulation of the placenta (9, 10). Placental malaria can have serious outcomes including disease for the mother, low birth weight, and fetal death (10).

PEs isolated from placenta have a unique adhesion phenotype. Whereas most isolates bind CD36 (1, 2), the major endothelial receptor for sequestration in microvasculature beds (11), placental parasites fail to bind CD36 and bind mainly to chondroitin sulfate A (CSA; refs. 3 and 12). Furthermore, it has been described that placental parasites also can bind to hyaluronic acid (12) and IgG (13), and that these PEs also do not bind to CD36 (12, 13). Thus, CSA adhesion is a rare adherence property for most isolates from children, men, and nonpregnant women and is found primarily in isolates from pregnant women (2). This apparent dichotomy in parasite adhesion to CD36 or to CSA is a key factor controlling the tissue distribution of PEs between microvasculature and placenta during pregnancy.

Both receptors, CD36 and CSA, as well as intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) are recognized by members of the large and highly diverse var gene family that encode the P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP-1; refs. 14 and 15). PfEMP-1 possesses several adhesive modules of two types, the cysteine-rich interdomain regions (CIDR) and the Duffy binding-like (DBL) domains (16). Different domains of PfEMP-1 mediate binding to the host receptors CD36, ICAM-1, and CSA. The CIDR1 domain, located after the first DBL domain, is the binding domain for CD36, whereas DBLβ-C2 and DBLγ bind to ICAM-1 and CSA, respectively (17–19). Recently, we observed that CIDR1 from CSA-adherent parasites do not bind CD36, explaining the non-CD36-binding phenotype of CSA-adherent parasites (20). Because two nonoverlapping domains of PfEMP-1 mediate the binding to CSA and CD36, it is not clear why we are unable to find PEs and PfEMP-1 that bind to both receptors.

Here we studied the molecular basis for the dichotomy in adhesion to CD36 and CSA. For this purpose, DBLγ and CIDR1 domains were expressed alone or in combination and tested for binding to CD36 and CSA. Our findings suggest that the binding properties of CIDR1 affect the ability of the DBLγ to bind CSA, which provides a molecular basis for the dichotomy in adhesion to CD36 and CSA leading to PEs sequestration in either microvasculature beds or placenta. We also present evidence that interactions between distinct var gene domains can lead to an altered binding/adhesion phenotype.

Materials and Methods

Construction of Recombinant Plasmids for Surface Expression in Mammalian Cell Lines.

Constructs were amplified from genomic DNA by PCR and cloned into the pSRα5 vector (Affymax Research Institute, Santa Clara, CA) between the BamHI/NotI and EcoRI sites for expression in mammalian cells. The pSRα5 vector supplies a signal sequence and a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor for cell-surface expression as well as a selectable marker for stable integration. The following domains were used (amino acid boundaries of each clone and the GenBank accession number of the corresponding var gene are given): FCR3-CSA DBL3γ (1,270–1,577, AJ133811); FCR3-CSA DBL5γ (2,091–2,389, AJ133811); A4 DBL4γ (1,995–2,401, L42244); 3D7 AL010226 DBL4γ (1,722–2,026, AL010226); FCR3-Var3 DBL3γ (1,235–1,545, L40609); ItG2-CS2 DBL2γ (908–1,215, AF134154); ItG2-CS2 CIDR1 (GHR) (421–920, AF134154); ItG2-CS2 CIDR1 (DIE) (421–920); ItG2-CS2 CIDR1 (GHR)-DBL2γ (421–1,215, AF134154); ItG2-CS2 CIDR1 (DIE)-DBL2γ (421–1,215); A4-tres DBL3γ (1,224–1,574, AF193424); and A4-tres DBL2β-C2-DBL3γ (716–1,574, AF193424). The CIDR1 GHR and DIE clones of ItG2-CS2 represent identical clones with a three-amino acid change (GHR to DIE) at residues 340–342.

Surface Expression of Various Domains in Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) Cells.

CHO PgsA-745 (CHO-745) cells deficient in glycosaminoglycans were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The cells were grown in RPMI medium 1640 (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS (Life Technologies). Cells were transfected with 2.5 μg of plasmid DNA by using the Superfect transfection reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer recommendations and selected with 1 mg/ml Geneticin (Life Technologies). Stable transfectants expressing the various domains on the surface of CHO-745 cells were selected by single-cell cloning by using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter as described (21).

Binding Assays with Dynal Beads Coated with Recombinant CD36.

Binding assays with CD36-coated magnetic beads were performed as described (20). In brief, 107 sheep anti-murine IgG magnetic beads (Dynal, Oslo) were coated with 1.0 μg of anti-FLAG M1 (Sigma) and used to immobilize soluble CD36 (Affymax Research Institute). Transfected cells grown on coverslips were overlaid with 45 μl of RPMI binding medium (BMB, RPMI medium 1640/25 mM Hepes/1% BSA, pH 6.8) containing 1.5 × 106 CD36-coated beads and incubated 1 h at 37°C in a humidified chamber. After incubation, the coverslips were washed, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, PA), and processed for immunofluorescence as described previously. One hundred cells expressing the recombinant protein as determined by immunofluorescence were checked for the presence of CD36-coated Dynal beads on their surface. Cells with four or more beads attached were considered positive for binding. In some assays, the total number of beads associated with 100 binding-positive cells was determined.

Binding Assays with CSA Linked to Biotin (Biot-CSA).

Binding assays with CSA (Sigma) linked to biotin were performed as described (17). In brief, sheep anti-mouse IgG M-450 Dynabeads (2 × 106) were incubated overnight at 5°C with 2 μg of mouse antibiotin mAb (Jackson ImmunoResearch). The beads were washed three times with BMB and resuspended with 45 μl of BMB to 4 × 107 beads per ml. CHO-745 cells (100,000) expressing the different constructs were grown for 48 h on four glass coverslips in a six-well plate. Coverslips were transferred into a 12-well plate containing 1 ml of BMB and 50 μg of Biot-CSA and incubated for 1 h. For inhibition assays, the cells were incubated for 1 h with 200 μg/ml of CSA or chondroitin sulfate C (CSC, Sigma) before the addition of Biot-CSA. The coverslips were washed three times with BMB, transferred to a humidified chamber, and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with the coated Dynal beads (45 μl of 4 × 107 beads per ml). The coverslips then were flipped cell-side down onto a stand and incubated for 3 min to allow unbound beads to settle by gravity. Coverslips were washed three times with BMB and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS, and the degree of bead association with cells was examined.

Results and Discussion

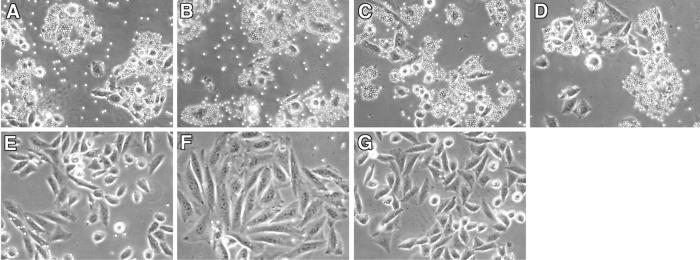

We used heterologous expression of domains from various PfEMP-1s to identify the molecular basis for the dichotomy in parasite binding to CD36 and CSA. Previously we demonstrated that the CIDR1s from CSA binding PfEMP-1 are unable to bind CD36 (20), whereas a DBL3γ from one of these genes (FCR3varCSA) specifically binds CSA (17). We extended these studies to include more DBLγ domains from PfEMP-1s of CSA- and non-CSA-adherent parasites. Two DBLγ domains from CSA-adherent parasites (FCR3-CSA DBL3 and ItG2-CS2 DBL2) strongly bound CSA, and the binding was specific for CSA but not CSC (Table 1 and Fig. 1). A third DBLγ domain from the 3D7 AL010226 var gene that has a non-CD36-binding CIDR1 (20) also readily bound CSA (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Several other DBLγ domains (FCR3-CSA DBL5γ, FCR3-Var3 DBL3γ, and A4 DBL4γ) did not bind CSA, indicating that not all DBLγ domains possess this property (Table 1 and Fig. 1). One of the DBLγs tested in this study came from the CD36- and ICAM-1-binding A4-tres clone that does not bind CSA (19). Surprisingly, the A4-tres DBL3γ strongly bound CSA in a specific manner (Table 1 and Fig. 1), although A4-tres PEs adhere to CD36 and ICAM-1 but not to CSA. This striking observation raised the possibility that other domains of PfEMP-1 may interfere with the ability of the DBLγ to bind CSA, leading to a non-CSA-binding phenotype.

Table 1.

Binding characteristics of different DBLγ to Biot-CSA

| PE phenotype | CIDR1 binding to CD36 | Construct expressed | Binding of Biot-CSA to CHO-745 cells*

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No inhibition

|

Inhibition with CSA

|

Inhibition with CSC

|

||||||

| Positive cells,† % | Beads per 100 cells‡ | Positive cells,† % | Beads per 100 cells‡ | Positive cells,† % | Beads per 100 cells‡ | |||

| CSA+/CD36− | − | FCR3-CSA DBL3γ | 93 ± 2 | 1,432 ± 89 | 2 ± 1 | ND | 91 ± 5 | 1,163 ± 24 |

| − | ItG2-CS2 DBL2γ | 76 ± 3 | 1,023 ± 56 | 1 ± 1 | ND | 71 ± 8 | 986 ± 47 | |

| − | FCR3-CSA DBL5γ | 2 ± 1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| CD36+/CSA− | + | A4-tres DBL3γ | 89 ± 3 | 1,356 ± 72 | 0 ± 1 | ND | 92 ± 4 | 1,389 ± 63 |

| + | A4 DBL4γ | 1 ± 1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Unknown | − | 3D7 AL010226 DBL4γ | 98 ± 1 | 1,548 ± 49 | 3 ± 2 | ND | 97 ± 4 | 1,441 ± 57 |

| ND | FCR3-Var3 DBL3γ | 3 ± 2 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

ND, not determined.

Cells were incubated with Biot-CSA without (control) or after preincubation with 200 μg/ml CSA or CSC.

One hundred cells expressing the recombinant protein were checked for the presence of CSA-coated Dynal beads on their surface. Cells with four or more beads attached were considered positive for binding. Results are expressed as the mean and SD of three independent experiments.

The number of beads was counted on 100 cells determined positive for binding to CSA-coated Dynal beads. Results are expressed as the mean and SD of three independent experiments.

Figure 1.

Binding of CSA to CHO-745 cells expressing various DBLγ domains. Binding of antibiotin-coated Dynabeads to CHO-745 cells expressing different DBLγ domains preincubated with 50 μg/ml of Biot-CSA is shown. Binding was detected in FCR3-CSA DBL3γ (A), A4-tres DBL3γ (B), 3D7 AL010226 DBL4γ (C), and ItG2-CS2 DBL2γ (D). No binding was seen in FCR3-Var3 DBL3γ (E), A4 DBL4γ (F), or FCR3-CSA DBL5γ (G).

Parasites that are isolated from the human placenta do not bind to the endothelial receptor CD36 and primarily adhere to CSA, hyaluronic acid, or IgG (3, 12, 13). Selection of parasites on CSA is associated with concomitant loss of binding to CD36 and vice versa (14, 22, 23). The apparent dichotomy between CD36 and CSA adhesion made the CD36-binding domain, CIDR1, an attractive candidate. We previously observed that modifications in the CD36 minimal binding region (M2 region) were responsible for the inability of CSA-selected parasites to bind CD36 (20). One of these modifications was mapped to a three-amino acid substitution in the ItG2-CS2 CIDR1 (DIE to GHR) that modified its properties from CD36 binding [CIDR1 (DIE)] to a non-CD36-binding CIDR1 [CIDR1 (GHR)] (20, 22). Expression of these CIDR1s on the surface of CHO-745 cells confirmed our previous transient-expression results that only the DIE form bound CD36. Neither DIE nor GHR CIDR1 domain tested bound CSA (Table 2).

Table 2.

Binding characteristics of single- and double-domain constructs of PfEMP-1 to CD36 and CSA

| Construct expressed | Binding of Biot-CSA or CD36 to CHO-745 cells

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Binding to CD36, % of positive cells* | Binding to CSA, % of positive cells* | |

| ItG2-CS2 CIDR1 (DIE) | 93 ± 6 | 0 ± 1 |

| ItG2-CS2 CIDR1 (GHR) | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 |

| ItG2-CS2 DBL2γ | 0 ± 0 | 76 ± 3 |

| ItG2-CS2 CIDR1 (DIE)–DBL2γ | 83 ± 7 | 0 ± 1 |

| ItG2-CS2 CIDR1 (GHR)–DBL2γ | 0 ± 0 | 63 ± 12 |

| A4-tres DBL3γ | 0 ± 0 | 89 ± 3 |

| A4-tres DBL2β-C2–DBL3γ† | 1 ± 1 | 72 ± 4 |

One hundred cells expressing the recombinant protein were checked for the presence of CSA- or CD36-coated Dynal beads on their surface. Cells with four or more beads attached were considered positive for binding. Results are expressed as the mean and SD of three independent experiments.

Binds ICAM-1 (19).

We took advantage of these two forms of CIDR1 and expressed them in combination with the DBL2γ that binds CSA. When the CIDR1 (GHR, non-CD36-binding) was expressed with the DBL2γ, the two-domain construct bound CSA and failed to bind CD36 (Table 2), similar to the binding properties of each of the domains alone. The presence of a CSA-binding DBLγ domain did not affect the CD36-binding properties of the adjacent CIDR1 in the CIDR1 (DIE)–DBL2γ construct (Table 2); however, the presence of a CD36-binding CIDR1 (DIE) ablated the ability of the adjacent DBLγ to bind CSA (Table 2). Thus, a three-amino acid modification in the CIDR1 domain affected not only the binding properties of this domain but also the properties of the adjacent CSA-binding DBLγ domain.

To test whether this effect is unique for CD36-binding CIDR1, we used a DBL2β-C2–DBL3γ construct from the A4-tres var gene that contains the ICAM-1-binding region (DBL2β-C2) and was shown to bind ICAM-1 (19). The same construct (A4-tres DBL2β-C2-DBL3γ) also bound CSA (Table 2). Thus, the addition of a domain that binds ICAM-1 did not interfere with the CSA-binding properties of the adjacent DBLγ, and both properties can reside on the same construct. The presence of a CD36-binding CIDR1 in the A4-tres var gene (19, 20) is likely to be responsible for the lack of CSA binding of these PEs, which helps explain the presence of DBLγ with the potential to bind CSA in PfEMP-1 from non-CSA-binding PEs. Unfortunately, a CIDR1–DBL2β-C2–DBL3γ construct was too large to be tested efficiently in our expression system.

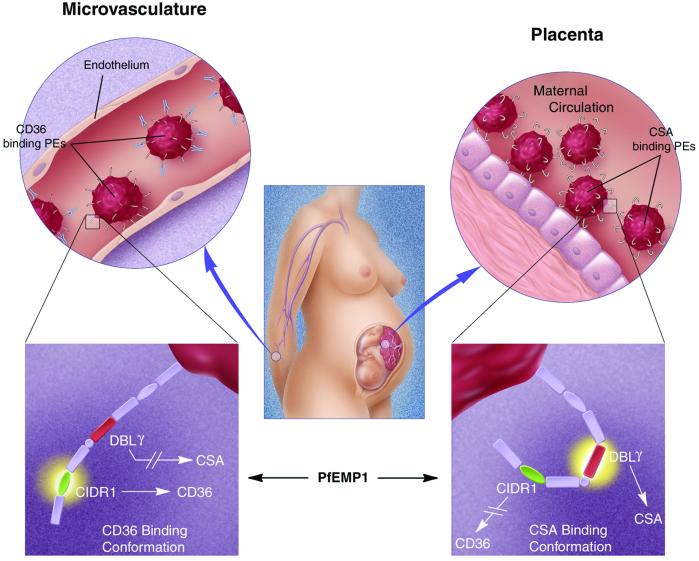

We propose that individual CIDR1 and DBLγ domains having CD36- and CSA-binding properties may reside on the same PfEMP-1 but that these functions are mutually exclusive in the protein (Fig. 2). This result provides a molecular basis for the dichotomy in adhesion and accounts for the different sequestration patterns of these parasites. It is also evidence that interactions between different domains of PfEMP-1 may affect the adhesion properties of the infected erythrocyte.

Figure 2.

Proposed model for the dichotomy in adhesion to microvasculature endothelium and placenta. Pregnant women, particularly during their first pregnancy, exhibit a massive sequestration of PEs in the placenta. These PEs bind to CSA and not to CD36 and are not recognized by Abs to previously encountered (CD36-binding) isolates that adhere to microvasculature endothelium. PfEMP-1 of CSA-adherent parasites have a unique conformation that depends on a non-CD36-binding CIDR1 domain, allowing the DBLγ to bind CSA (Bottom Right). The presence of a CD36-binding CIDR1 interferes with this conformation, ablating the capacity of the DBLγ to bind CSA (Bottom Left). The dichotomy in adhesion is important to avoid immune responses against (CSA-binding) placental isolates before pregnancy, maintaining this set of structurally and functionally unique PfEMP-1s.

A three-residue change (GHR to DIE) in the CIDR1 domain (from ItG2 to CS2) modified the binding properties of the CIDR1 and the adjacent DBLγ. One plausible explanation is that a conformational change in the CIDR1 domain also leads to a non-CSA-binding conformation in the DBLγ, which also will account for a similar effect in those var genes where the CIDR1 and the DBLγ are separated by another DBL (mostly DBLβ) domain as with FCR3varCSA, A4-tres, and A4 PfEMP-1s (16, 17, 19). Thus, It is likely that the change in the CIDR1 domain will have an effect on the overall conformation of the PfEMP-1.

We propose that the basis for the dichotomy is structural and that PfEMP-1s from CD36- and CSA-binding PEs are different structurally. Although structural studies are needed to verify this suggestion, examination of the available data are consistent with this idea. Immunologic observations highlight the distinction between these forms of PfEMP-1. Most isolates from children and nonpregnant adults form large agglutinates in the presence of immune serum from adult residents of endemic areas (2, 24, 25). In contrast, CSA-binding parasites generally form either small or no agglutinates (2) in the presence of specific Abs that react with the surface of PEs as indicated by flow cytometry or blocking adhesion to CSA (26, 27). In addition, PfEMP-1 from CSA-binding PEs seems much more resistant to trypsin than most CD36-binding PfEMP-1s (12, 17, 23, 28–30). Abs that recognize a conserved and unique conformation of PfEMP-1 may explain why sera from pregnant women react with placental isolates from different regions of the world (26). Evading host immunity also may play a major role in selecting this unique parasite population (Fig. 2). Thus, understanding the structure of CSA-binding PfEMP-1s is important for our comprehension of immunity to placental malaria and for the development of vaccines.

An interesting question is why women who otherwise are clinically immune (7, 8) develop symptomatic infections particularly during their first pregnancies (9, 10, 26). One suggestion relates to a decreased immune status during pregnancy; however, clinical protection against placental infection develops with parity (26, 27), indicating that repeated exposure to these parasites provide immunity. By reproductive age, residents of endemic areas have had years of exposure to P. falciparum and developed Abs to most isolates (8, 25). The lack of Abs to the surface of placental isolates without pregnancy suggests that these parasite populations are cryptic and can expand and become virulent only in the presence of the placenta (2, 27). In nonpregnant individuals, CSA-adherent PEs lacking the ability to bind CD36, a vital receptor for adhesion to endothelial cells (11), fail to sequester and are cleared rapidly by the spleen without building a protective Ab response. Only when receptors become available in the placenta (i.e., CSA, hyaluronic acid, and neonatal FC receptors) is the parasite able to sequester and proliferate. Thus, the placenta offers a privileged site for the antigenically unique CSA-adherent PEs to emerge and survive, primarily during first pregnancies.

The unique conformation of CSA-binding PfEMP-1, which does not allow agglutination of PEs, is likely to preclude binding of Abs against other (CD36-binding) forms of PfEMP-1. If structural dichotomy did not exist and both properties were found on a single var gene, then immunity to both forms would develop the first time such PfEMP-1 is expressed. Abs to PfEMP-1 play a major role in clinical protection during childhood (31). Apparently, such immunity is critical also in adults and in combination with the PE-adhesion properties become a powerful selective force on the parasite population.

The proposed model (Fig. 2) for the dichotomy in adhesion to microvasculature endothelium and placenta presents a complex relationship between adhesion and antigenic variation that affects P. falciparum biology and pathogenesis. The structural basis for the dichotomy gives insight into the importance of the structure of PfEMP-1 and the central role of these proteins in P. falciparum biology.

Abbreviations

- PE

parasitized erythrocyte

- CSA

chondroitin sulfate A

- CSC

chondroitin sulfate C

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule 1

- PfEMP-1

P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1

- CIDR

cysteine-rich interdomain region

- DBL

Duffy binding-like

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- Biot-CSA

biotinylated CSA

References

- 1.Newbold C, Warn P, Black G, Berendt A, Craig A, Snow B, Msobo M, Peshu N, Marsh K. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:389–398. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beeson J G, Brown G V, Molyneux M E, Mhango C, Dzinjalamala F, Rogerson S J. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:464–472. doi: 10.1086/314899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fried M, Duffy P E. Science. 1996;272:1502–1504. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5267.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David P H, Hommel M, Miller L H, Udeinya I J, Oligino L D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:5075–5079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.16.5075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Q, Schlichtherle M, Wahlgren M. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:439–450. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.3.439-450.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newbold C I, Craig A G, Kyes S, Berendt A R, Snow R W, Peshu N, Marsh K. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1997;91:551–557. doi: 10.1080/00034989760923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith T A, Leuenberger R, Lengeler C. Trends Parasitol. 2001;17:145–149. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(00)01814-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snow R W, Marsh K. Br Med Bull. 1998;54:293–309. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bray R S, Sinden R E. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1979;73:716–719. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(79)90028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fried M, Duffy P E. J Mol Med. 1998;76:162–171. doi: 10.1007/s001090050205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho M, Hickey M J, Murray A G, Andonegui G, Kubes P. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1205–1211. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.8.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beeson J G, Rogerson S J, Cooke B M, Reeder J C, Chai W, Lawson A M, Molyneux M E, Brown G V. Nat Med. 2000;6:86–90. doi: 10.1038/71582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flick K, Scholander C, Chen Q, Fernandez V, Pouvelle B, Gysin J, Wahlgren M. Science. 2001;293:2098–2100. doi: 10.1126/science.1062891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scherf A, Hernandez-Rivas R, Buffet P, Bottius E, Benatar C, Pouvelle B, Gysin J, Lanzer M. EMBO J. 1998;17:5418–5426. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baruch D I, Pasloske B L, Singh H B, Bi X, Ma X C, Feldman M, Taraschi T F, Howard R J. Cell. 1995;82:77–87. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith J D, Subramanian G, Gamain B, Baruch D I, Miller L H. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;110:293–310. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buffet P A, Gamain B, Scheidig C, Baruch D, Smith J D, Hernandez-Rivas R, Pouvelle B, Oishi S, Fujii N, Fusai T, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12743–12748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baruch D I, Ma X C, Singh H B, Bi X, Pasloske B L, Howard R J. Blood. 1997;90:3766–3775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith J D, Craig A G, Kriek N, Hudson-Taylor D, Kyes S, Fagen T, Pinches R, Baruch D I, Newbold C I, Miller L H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1766–1771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040545897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gamain B, Smith J D, Miller L H, Baruch D I. Blood. 2001;97:3268–3274. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith J D, Kyes S, Craig A G, Fagan T, Hudson-Taylor D, Miller L H, Baruch D I, Newbold C I. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;97:133–148. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00145-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reeder J C, Cowman A F, Davern K M, Beeson J G, Thompson J K, Rogerson S J, Brown G V. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5198–5202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogerson S J, Chaiyaroj S C, Ng K, Reeder J C, Brown G V. J Exp Med. 1995;182:15–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aguiar J C, Albrecht G R, Cegielski P, Greenwood B M, Jensen J B, Lallinger G, Martinez A, McGregor I A, Minjas J N, Neequaye J, et al. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;47:621–632. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marsh K, Howard R J. Science. 1986;231:150–153. doi: 10.1126/science.2417315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fried M, Nosten F, Brockman A, Brabin B J, Duffy P E. Nature (London) 1998;395:851–852. doi: 10.1038/27570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ricke C H, Staalsoe T, Koram K, Akanmori B D, Riley E M, Theander T G, Hviid L. J Immunol. 2000;165:3309–3316. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baruch D I, Gormely J A, Ma C, Howard R J, Pasloske B L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3497–3502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaiyaroj S C, Angkasekwinai P, Buranakiti A, Looareesuwan S, Rogerson S J, Brown G V. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55:76–80. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leech J H, Barnwell J W, Miller L H, Howard R J. J Exp Med. 1984;159:1567–1575. doi: 10.1084/jem.159.6.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bull P C, Lowe B S, Kortok M, Molyneux C S, Newbold C I, Marsh K. Nat Med. 1998;4:358–360. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]