Abstract

We identify ADAR1, an RNA-editing enzyme with transient nucleolar localization, as a novel substrate for sumoylation. We show that ADAR1 colocalizes with SUMO-1 in a subnucleolar region that is distinct from the fibrillar center, the dense fibrillar component, and the granular component. Our results further show that human ADAR1 is modified by SUMO-1 on lysine residue 418. An arginine substitution of K418 abolishes SUMO-1 conjugation and although it does not interfere with ADAR1 proper localization, it stimulates the ability of the enzyme to edit RNA both in vivo and in vitro. Moreover, modification of wild-type recombinant ADAR1 by SUMO-1 reduces the editing activity of the enzyme in vitro. Taken together these data suggest a novel role for sumoylation in regulating RNA-editing activity.

INTRODUCTION

A defining feature of eukaryotic cells is the generation of protein diversity either posttranscriptionally by alternative splicing and RNA editing or posttranslationally by modification of amino acids in proteins. One of the most recently discovered posttranslational modification mechanism in eukaryotes involves the covalent attachment of the small ubiquitinlike modifier, SUMO, to target proteins. Modification of proteins by SUMO, or sumoylation, plays crucial regulatory roles in eukaryotes. Proteins known to be modified by SUMO include, among others, RanGAP1, PCNA, IκBα, p53, c-jun, topoisomerases, promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML), Sp100, and the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 (MEKK1). Many SUMO substrates are transcription factors and cofactors, or proteins implicated in DNA repair and replication (reviewed by Hay, 2001; Melchior et al., 2003; Seeler and Dejean, 2003; Hay, 2005). Although it is well established that SUMO can affect target protein function by altering its subcellular localization, activity, or stability, for many substrates the biological functions of sumoylation remain unknown.

Sumoylation is a reversible and highly dynamic process that involves formation of an isopeptide bond between the C-terminus of SUMO and the ε-amino group of a lysine residue of the target protein. The most intensely studied human form of SUMO is the SUMO-1 protein, which is 48% identical to yeast Smt3 (Bayer et al., 1998; Mossessova and Lima, 2000). In vertebrates there are at least three additional proteins. SUMO-2 and SUMO-3 are ∼45% identical to SUMO-1 (Saitoh and Hinchey, 2000), and SUMO-4 shows an 86% amino acid homology to SUMO-2 (Bohren et al., 2004). SUMO is conjugated to protein substrates via an ATP-dependent enzymatic pathway that is mechanistically similar to ubiquitination. The reaction requires a SUMO protease that removes four amino acids from the C-terminus of the 101-amino acid SUMO-1 precursor to generate the mature form; an heterodimeric SUMO-activating enzyme, SAE1/2; Ubc9, a SUMO-conjugating enzyme that ligates directly to its protein target; and an E3-like SUMO ligase (reviewed Melchior et al., 2003). Three SUMO E3s have been identified so far: the mammalian protein inhibitors of activated STAT (PIAS; Sachdev et al., 2001), the nucleoporin RanBP2 (Azuma and Dasso, 2002; Pichler et al., 2002), and the polycomb group protein PC2 (Kagey et al., 2003). Recent structural data provide novel insights into the mechanism used by E3s to enhance SUMO conjugation (Duda and Schulman, 2005; Reverter and Lima, 2005; Tatham et al., 2005).

Removal of SUMO from proteins is carried out by specific cysteine proteases that have both hydrolase and isopeptidase activity (Li and Hochstrasser, 1999, 2000). Most enzymes involved in the SUMO pathway are localized in the nucleus, and it is therefore believed that sumoylation is predominantly a nuclear process (Rodriguez et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2002; Seeler and Dejean, 2003).

Here, we describe that proteins modified by SUMO-1 are present in the nucleolus, that SUMO-1 in the nucleolus colocalizes with the RNA-editing enzyme ADAR1, and that this enzyme represents a novel substrate for sumoylation.

ADAR1 (adenosine deaminase that acts on RNA) is a member of the family of enzymes that catalyze the conversion of adenosine to inosine in double-stranded RNA (dsRNA; reviewed in Keegan et al., 2001; Bass, 2002; Schaub and Keller, 2002). Because inosine acts as guanosine during translation, A-to-I conversion in coding sequences leads to amino acid changes and often entails changes in protein function. In addition to amino acid changes, A-to-I RNA editing can also occur in 5′ and 3′ UTR (Morse and Bass, 1999), in introns (Higuchi et al., 1993), and at splicing branch site (Beghini et al., 2000). Editing can also generate a 3′ splice acceptor (Rueter et al., 1999) and relieve a stop codon (Polson et al., 1996). In mammals there are three ADAR enzymes, termed ADAR1, ADAR2, and ADAR3. Inactivation of editing enzymes in mice (Higuchi et al., 2000) and in the fruit fly (Palladino et al., 2000b) has resulted in profound neurological phenotypes. All ADAR proteins have a highly conserved catalytic domain at the C-terminus and one to three dsRNA-binding domains. ADAR1 differs from the other members of the family in its extended N-terminus that is enriched in RG residues and contains two tandemly arranged Z-DNA-binding domains (Keegan et al., 2001, 2004). In humans, there are two ADAR1 forms: a 150-kDa protein (comprising amino acids 1–1226) that is induced by interferon and localizes predominantly in the cytoplasm, and a 110-kDa protein (encompassing residues 296-1226) that is constitutively expressed and localizes to the nucleus (Patterson and Samuel, 1995; George and Samuel, 1999b, a).

Several lines of evidence suggest that ADAR activity is tightly controlled in the cell. ADARs act as dimers and heterodimer formation between different ADAR forms can contribute to regulate enzyme activity and substrate specificity (Cho et al., 2003; Gallo et al., 2003). In Drosophila, ADAR can edit its own pre-mRNA (Palladino et al., 2000a), whereas in mammals a self-editing process leads to alternative splicing of ADAR2 (Rueter et al., 1999). Furthermore, ADAR1 expression in mammals is regulated by interferon (Patterson and Samuel, 1995).

In this work we demonstrate that ADAR1 is modified by SUMO at lysine residue 418. Substitution of this amino acid residue by arginine, which cannot be modified by SUMO, affects the editing activity of the enzyme. Our results therefore suggest a novel role for SUMO in regulating ADAR1 editing activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies

Endogenous ADAR1 was detected with rabbit polyclonal antibodies (antibody 007 and antibody 668; Desterro et al., 2003). Proteins tagged with a histidine hexamer were detected with an anti-His monoclonal antibody (mAb; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and hemaglutinin (HA)-tagged proteins were detected with the anti-HA mAb 11 (Babco, Richmond, CA). Green fluorescence protein (GFP) was detected with a mixture of two mouse monoclonal antibodies (anti-GFP clones 7.1 and 13.1; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) and endogenous SUMO-1 was detected with a rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). PML was detected with anti-PML mouse mAb (PGM-3; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Additionally, the following antibodies were used to detect nucleolar proteins: anti-B23/nucleophosmin goat polyclonal antibody C-19 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); anti-fibrillarin mAb 71B9 (Reimer et al., 1987); anti-UBF rabbit polyclonal antibody E29 (O'Mahony et al., 1992); and auto-immune human anti-RNA polymerase I serum S18 (kindly provided by Dr U. Scheer).

Plasmids

Plasmids expressing full-length hADAR1 (Desterro et al., 2003), the RC construct (Herbert et al., 2002), and GFP-SUMO (Gostissa et al., 1999) have been described previously.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

The point mutation in the lysine within the SUMO-1 consensus sequence was generated by oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis using the QuickChange site directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and the following oligonucleotides: 5′-GGAACCTGTCATAAGGTTAGAAAACAGGC-3′ and 5′-GCCTGTTTTCTAACCTTATGACAGGTTCC-3′. The nucleotides changed in this mutagenesis are indicated in bold.

Mutagenesis was performed on ADAR1 cloned in different plasmids, pEGFP, pFlis, and pPICZA but always with the same set of oligonucleotides. All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Cell Culture and Transfections

HeLa and COS7 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. To inhibit nuclear export, leptomycin B (LMB; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added to a final concentration of 50 nM to the tissue culture medium before fixation. DNA for transfections assays was purified with a Qiagen plasmid Midi-prep kit (Qiagen). HeLa subconfluent cells grown on glass coverslips in 35 × 10-mm tissue culture dishes were transiently transfected with 1 mg of purified plasmid DNA and FuGene6 reagent (Roche Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were analyzed 24–48 h after transfections.

For Ni2+-NTA-agarose pulldowns COS7 cells were transfected with Lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After transfections, cells were seeded in 75-cm2 flasks and the incubation continued for an additional 36 h. His-epitope-tagged proteins were isolated as described (Rodriguez et al., 1999).

Immunofluorescence

Cells on coverslips were briefly rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde (freshly prepared from paraformaldehyde), diluted in PBS for 10 min at room temperature, and washed with PBS. The cells were then permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min or 0.05% SDS for 10 min at room temperature and washed with PBS. Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy was performed as described (Calado et al., 2000).

In Situ Hybridization

GluR-B DNA was obtained by SmaI and XbaI digestion of the GluR-B/pRK plasmid (Higuchi et al., 1993) and RC DNA from EcoRI and XbaI digestion of the RC plasmid (Herbert et al., 2002). Both fragments were purified, labeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP by nick translation, and used as probes for in situ hybridization. Cells were fixed and permeabilized as described previously for immunofluorescence. Immediately before hybridization, cells were incubated in hybridization mixture for 5 min at 37°C. Cells were hybridized for 4 h at 37°C in 50% formamide, 2× SSC, 10% dextran sulfate, 50 nM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, with probes at 2 ng/μl. Posthybridization washes were in 50% formamide, 2× SSC (three times for 5 min at 45°C) and in 2× SSC (three times for 5 min at 45°C). The sites of hybridization were visualized with cy3 anti-digoxigenin secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) diluted in 4× SSC-Tween, 2% bovine serum albumin, and 0.2% gelatin.

Microscopy

Samples were examined on a Zeiss LSM 510 microscope (Thornwood, NY) with a Planapochromat 63×/1.4 objective.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis of transfected cells was performed with whole cell extracts that were prepared in SDS sample buffer. Lysates were boiled for 10 min before electrophoresis on either 8.5 or 10% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by electroblotting. Anti-His, anti-ADAR1, and anti-GFP were used as primary antibodies. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and anti-rabbit IgG (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA) were used as secondary antibodies. Blots were developed with the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins

SUMO-1, Ubc9, and SAE1/SAE2 were expressed and purified from Escherichia coli B834 as described previously (Desterro et al., 1997; Tatham et al., 2001). Both ADAR wild-type and K418R mutant were overexpressed in the yeast Pichia pastoris and purified as described (Gallo et al., 2003).

In Vitro Expression of Proteins

In vitro-coupled transcription/translation of ADAR1 proteins was performed with 1 μg of plasmid DNA and a wheat germ-coupled transcription/translation system according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). [35S]methionine (Amersham Biosciences) was used in the reactions to generate radiolabeled protein.

In Vitro SUMO-1 Conjugation Assay

SUMO-1 conjugation assays were performed in 10 μl reactions containing an ATP regenerating system, 1 μl of [35S]methionine-labeled ADAR1 or 10 ng of either WT or K418R purified recombinant ADAR1 and purified recombinant SUMO-1, Ubc9, and SAE proteins as previously described (Tatham et al., 2001). Reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and either detected by Western blotting analysis using an anti-ADAR1 antibody or the gel was dried before overnight exposure to film.

In Vitro Editing

The nonspecific dsRNA substrate, a shorter form of BScat was prepared by in vitro transcription as previously reported and the editing assay was performed as previously described (O'Connell and Keller, 1994). The assay mixture contained dsRNA containing 200 fmoles of 32P-labeled adenosine, and the reaction was performed at 37°C for 60 min with purified recombinant ADAR1-WT and ADAR1-K418R.

Analysis of editing of a transcript encoded by the GluR-B mini-gene B13 was performed by primer extension assay with the BHS-RT primer specific for hotspot1 as previously described (Melcher et al., 1995). In the assay 10 fmol of in vitro-transcribed RNA was incubated with either purified recombinant protein or previously in vitro SUMO-1 modified protein for 1 h at 37°C. The reaction mixture was then treated with proteinase K for 30 min., phenol/chloroformed was extracted, and ethanol was precipitated. Radioactive BHS-RT primer, 10 fmol, was added and annealed at 52°C overnight. Subsequently an RT reaction was performed in the presence of ddTTP and after ethanol precipitation the extension products were electrophoresed on a 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The gel was dried and quantified on a PhosphorImager.

RESULTS

Proteins Modified by SUMO-1 Localize to the Nucleolus

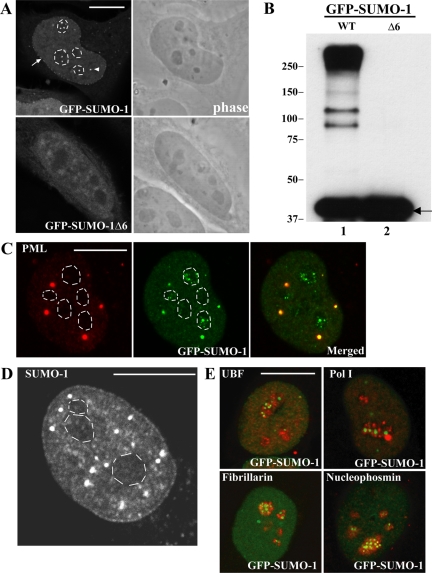

To date, most known sumoylated proteins are either nuclear proteins or proteins that shuttle to the nucleus. Within the nucleus, proteins modified by SUMO have been localized to the nucleoplasm, PML nuclear bodies and nuclear pore complexes (Melchior et al., 2003; Seeler and Dejean, 2003). To further characterize the subcellular distribution of SUMO-conjugated proteins, a fusion of SUMO-1 to the green fluorescence protein (GFP-SUMO-1) was transiently expressed in HeLa cells. GFP-SUMO-1 can replace endogenous SUMO (pmt3) in fission yeast, suggesting that the GFP tag does not interfere with SUMO-1 function in vivo (Tanaka et al., 1999). Analysis of HeLa cells expressing GFP-SUMO-1 reveals nuclear staining with accumulation at the nuclear pore complexes and in nuclear bodies, as previously described (Figure 1A, arrows and arrowheads). Surprisingly, an additional nucleolar staining is observed (Figure 1A, dashed lines). To confirm that the detection of GFP-SUMO-1 in the nucleolus corresponds to the presence of modified proteins, HeLa cells were transfected with GFP-SUMO-1Δ6. This mutant form of SUMO-1 lacks the C-terminal Gly-Gly motif and therefore cannot be conjugated to substrates (Johnson et al., 1997). Western blot analysis using antibodies against GFP shows that GFP-SUMO-1Δ6 is detected as a single band of the expected size (Figure 1B, arrow), whereas full-length GFP-SUMO-1 is detected as a high-molecular-weight smear of conjugated products, indicating that this GFP fusion protein is effectively conjugated. As shown in Figure 1A, GFP-SUMO-1Δ6 distributes throughout the cytoplasm and nucleoplasm, with no concentration at the nuclear periphery, nuclear bodies or the nucleolus. Thus, localization of SUMO-1 to the nucleolus depends on its ability to bind to substrates. This strongly suggests that proteins modified by SUMO-1 are present in the nucleolus. Immunolabeling experiments of GFP-SUMO-1-expressing cells with an anti-PML antibody demonstrate that the nucleolar staining does not correspond to PML bodies (Figure 1C). Staining of the nucleolus is also detected by immunofluorescence microscopy using a rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against SUMO-1 (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

GFP-SUMO-1 localizes to the nucleolus. (A) HeLa cells expressing GFP fusions of both full-length (GFP-SUMO-1) and unconjugatable form of SUMO-1 (GFP-SUMO-1Δ6). Fluorescence and contrast phase images of the same cell are shown side by side. The dashed lines indicate the contour of the nucleolus; arrows indicate staining of nuclear pore complexes; arrowheads point to nuclear bodies. (B) Western blot analysis of cells expressing both GFP-SUMO-1 and GFP-SUMO-1Δ6. The blot was probed with antibodies against GFP and molecular-weight markers (kDa) are shown on the left. (C) Immunolabeling experiments with anti-PML antibody (red staining) of HeLa cells expressing GFP-SUMO-1 confirmed that the nuclear bodies enriched in GFP-SUMO-1 correspond to PML bodies but the nucleolar dots do not colocalize with PML. (D) Subcellular distribution of endogenous SUMO-1. HeLa cells were immunolabeled with a rabbit antibody against SUMO-1. The dashed lines indicate the contour of the nucleolus. (E) HeLa cells expressing GFP-SUMO-1 (green staining) were immunolabeled (red staining) with antibodies directed against proteins that localize in the fibrillar centers (pol I, UBF), the dense fibrillar component (fibrillarin), and the granular component (B23/nucleophosmin). Bar, 10 μm.

Next, we analyzed in more detail the subnucleolar distribution of SUMO-1. In mammalian cells, the nucleolus comprises three major regions involved in ribosomal biogenesis: the fibrillar centers, the dense fibrillar component, and the granular component (Carmo-Fonseca et al., 2000). Transcription of rRNA genes localized at the fibrillar centers produces rRNA precursors (pre-rRNAs) that move away from the rDNA template and undergo a series of posttranscriptional processing reactions. The initial processing steps occur while the pre-rRNAs reside in the dense fibrillar component, whereas late processing events take place in the granular component. Reflecting the vectorial organization of ribosomal synthesis, the fibrillar centers contain proteins required for transcription of the rRNA genes, notably RNA polymerase I (pol I) and the pol I transcription initiation factor UBF (upstream binding factor); the dense fibrillar component contains proteins involved in early steps of pre-rRNA processing such as fibrillarin, and the granular component is highly enriched in proteins involved in the assembly of preribosomes, an example of which is B23 also called nucleophosmin (Scheer et al., 1993). Double-labeling of HeLa cells expressing GFP-SUMO-1 with antibodies specific for RNA polymerase I, UBF, fibrillarin, and nucleophosmin reveals lack of colocalization (Figure 1E). Thus, the major fraction of nucleolar proteins modified by SUMO-1 does not associate with the well-described subnucleolar regions implicated in ribosome biogenesis.

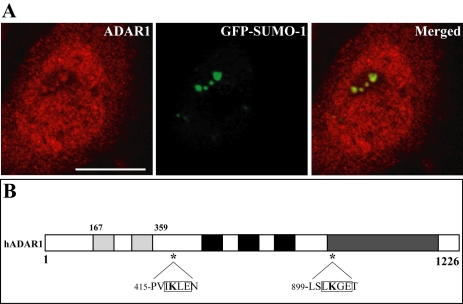

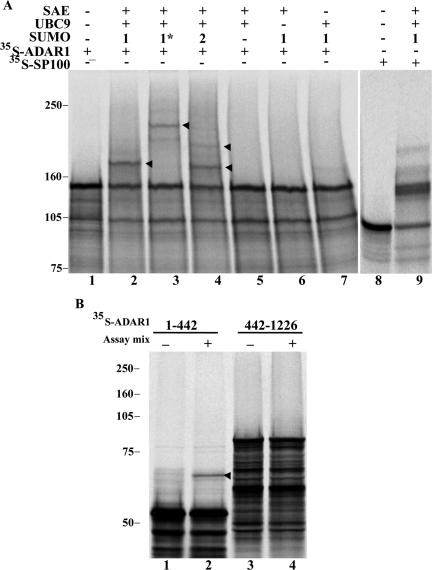

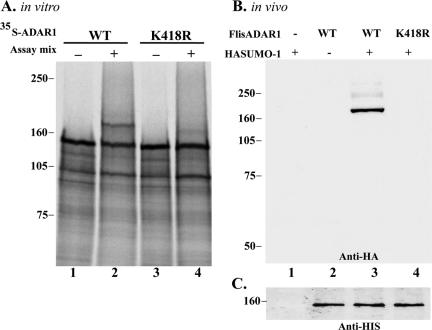

ADAR1 Is Modified by SUMO-1 In Vitro and In Vivo

We have recently shown that the RNA-editing enzymes ADAR1 and ADAR2 localize transiently to the nucleolus in a region that is distinct from the fibrillar centers, the dense fibrillar component, and the granular component (Desterro et al., 2003). We therefore double-labeled HeLa cells expressing GFP-SUMO-1 with an antibody specific for ADAR1 (Figure 2A). This antibody, which recognizes both forms of human ADAR1, labels the cytoplasm and the nucleoplasm, with additional staining of the nucleolus (Desterro et al., 2003). The results show a perfect colocalization at the nucleolus, raising the possibility that ADAR1 is a target for SUMO-1 conjugation. Most of the proteins modified by SUMO-1 contain the consensus motif ψKXE, where ψ is a hydrophobic large amino acid, K the modified lysine, X any amino acid, and E a glutamic acid (Rodriguez et al., 2001). Sequence analysis of the long form of ADAR1 (amino acids 1–1226) shows two lysines that conform to this consensus sequence (Figure 2B). To determine whether any of these lysine residues is a substrate for SUMO-1 modification, 35S-labeled ADAR1 was generated in vitro by a coupled transcription/translation reaction and incubated in an ATP-regenerating system with purified recombinant components required for SUMO modification, SUMO, SUMO-1-activating enzyme (SAE), and UBC9. As a previously described substrate, 35S-labeled Sp100, was used as positive control in the reaction (Sternsdorf et al., 1997). Analysis of the reaction products by SDS-PAGE indicates that a proportion of ADAR1 is converted to a more slowly migrating form that is dependent on the presence of SUMO reaction components (Figure 3A, lanes 2–4). Substitution of SUMO-1 for GST-SUMO-1 alters the mobility of the more slowly migrating form, which confirms that the mobility shift is due to SUMO modification (Figure 3A, lane 3). Furthermore, ADAR1 is also modified by SUMO-2, a SUMO-1-related protein (Figure 3A, lane 4). Analysis of deletion variants of ADAR1 reveals that a truncated version of the protein-encompassing amino acid residues 1–442 is modified by SUMO-1 in vitro (Figure 3B, lanes 1 and 2). In contrast, no modification is detected in a truncated variant that consists of amino acid residues 442-1226 (Figure 3B, lanes 3 and 4). Thus, it is likely that ADAR-1 is modified by SUMO-1 on lysine 418. To confirm this hypothesis, lysine 418 was mutated to an arginine (K418R) and the protein was assayed for SUMO-1 modification. ADAR1 containing this single point mutation is no longer modified in vitro by SUMO-1 (Figure 4A, lanes 3 and 4). Next we asked whether ADAR1 is modified by SUMO-1 in vivo. To address this question, COS7 cells were transfected with either ADAR1-WT or ADAR1-K418R tagged with a C-terminal histidine hexamer, with or without SUMO-1 tagged with HA. Cells were lysed directly with guanidine hydrochloride and HIS-tagged proteins were purified by chromatography over Ni2+-NTA agarose. Analysis of eluted proteins by Western blot with an anti-HA antibody reveals that wild-type ADAR1 is modified by SUMO-1 (Figure 4B, lane 3), whereas the mutant ADAR1-K418R fails to be modified (Figure 4B, lane 4). Western blot analysis of the total cell extracts before Ni2+-NTA chromatography indicates that this difference is not due to differences in the levels of expression of HA-tagged SUMO-1 or HIS-tagged ADAR1 (Figure 4C and unpublished data). The weak, slower migrating band seen in Figure 4B, lane 3, may reflect additional modification at another lysine. However, no conjugation to SUMO is detected in vivo in the mutant K418R (Figure 4B, lane 4) or in vitro in the 442-1226 deletion mutant (Figure 3B). We therefore consider that the putative modification at the additional residue depends on the N-terminus consensus site. Taken together, our in vitro and in vivo data demonstrate that ADAR1 is modified by SUMO-1 and that the major acceptor site for this modification is lysine residue 418.

Figure 2.

Nucleolar ADAR1 colocalizes with GFP-SUMO-1. (A) HeLa cell expressing GFP-SUMO-1 (green staining) and immunolabeled with an antibody directed against ADAR1 (antibody 007, red staining). This antibody recognizes both the long (150 kDa) and the short (110 kDa) forms of endogenous ADAR1. The long form of the protein is predominantly cytoplasmic, whereas the short form is nuclear. In some cell nuclei, ADAR1 is detected in discrete regions within the nucleolus, as previously described (Desterro et al., 2003). Superimposition of red and green images reveals perfect colocalization of SUMO and ADAR1 in the nucleolus. Bar, 10 μm. (B) Schematic representation of the hADAR1 protein (long form, amino acids 1–1226). The most important structural features of the enzyme are indicated: the Z-DNA-binding domains (gray); the double-stranded RNA-binding domains (dsRBDs, black); and the deaminase domain (dark gray). Asterisks depict the position of potential SUMO-1 conjugation sites.

Figure 3.

SUMO modification of ADAR1 in vitro. (A) In vitro-expressed and 35S-labeled ADAR1 was incubated with ATP, recombinant SUMO, Ubc9, and SUMO-1-activating enzyme (SAE). Where indicated, either SUMO, SAE, or Ubc9 were omitted (–) from the reaction. Reactions were carried out with either SUMO-1 (1), SUMO-2 (2), or GST-SUMO-1 (1*) as indicated, and Sp100 was used as positive control. Reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and phosphorimaging. (B) In vitro-expressed and 35S-labeled C-(1–442) and N-terminal (442–1226) ADAR1 deletions were incubated with ATP and SUMO-1 reaction components (assay mix), and the reaction products were analyzed as in A. The bands corresponding to the SUMO-conjugated forms of ADAR1 are indicated (arrowheads). Molecular-weight markers (kDa) are shown on the left.

Figure 4.

ADAR1 is modified by SUMO-1 both in vitro and in vivo on lysine 418. (A) In vitro-expressed and 35S-labeled ADAR1 proteins, either WT or the mutant containing a lysine to arginine substitution (K418R), were assayed for SUMO-1 conjugation as described in Figure 3. (B) COS7 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids, and after 36 h were harvested and lysed in buffer containing guanidinium-HCl. His-tagged ADAR1 proteins were purified by elution from Ni2+-NTA-agarose with 200 mM imidazole. Eluted HA-SUMO-ADAR1 was detected by Western blot analysis using anti-HA antibody. (C) A fraction of the COS7 cell extracts shown in B were TCA precipitated and analyzed by Western blot with an anti-HIS antibody to detect exogenous levels of ADAR1 protein. Molecular-weight markers (kDa) are shown on the left.

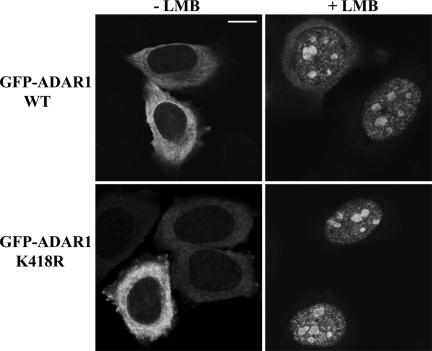

The Subcellular Distribution of ADAR1 Is Independent from Modification by SUMO-1

Because SUMO-1 modification can alter the localization of target proteins, we decided to investigate whether this modification modulates ADAR1 subcellular distribution. When HeLa cells are transfected with full-length hADAR1 tagged with GFP at the N-terminus, the fusion protein (GFP-ADAR1) is detected predominantly in the cytoplasm (Desterro et al., 2003). Although at steady state this fusion protein appears exclusively cytoplasmic, GFP-ADAR1 shuttles constantly between the nucleus and the cytoplasm due to a CRM1-dependent nuclear export signal (NES; Poulsen et al., 2001; Desterro et al., 2003). Treatment of cells with leptomycin B (LMB), a specific CRM1 inhibitor, prevents nuclear export, causing accumulation of the protein in the nucleus with higher concentration in the nucleolus (Poulsen et al., 2001; Desterro et al., 2003). As shown in Figure 5, similar results are observed in cells that express either ADAR1-WT or ADAR1-K418R, the mutant variant that fails to be modified by SUMO-1. Thus, SUMO-1 modification appears dispensable for nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling and nucleolar targeting of ADAR1, but one cannot exclude that the mutant can form a dimer with endogenous WT protein and be correctly targeted (Gallo et al., 2003).

Figure 5.

SUMO-1 modification is not required for ADAR1 cellular localization and shuttling. HeLa cells expressing either GFP-ADAR1-WT or GFP-ADAR1-K418R for 18 h were incubated with or without 50 nM leptomycin B (LMB) for 3 h. In the absence of LMB, both forms of the ADAR1 protein are detected predominantly in the cytoplasm. Blocking nuclear export by LMB results in nuclear accumulation and concentration in the nucleolus. Bar, 10 μm.

Recent studies have shown that ADAR1 is in constant flux in and out of the nucleolus and that when cells express the editing-competent glutamate receptor GluR-B mini-gene B13 in the nucleoplasm, ADAR1 is no longer detected in the nucleolus (Desterro et al., 2003; Sansam et al., 2003). To investigate whether the nucleolar SUMO-1 signal is dependent on the presence of ADAR1 in the nucleolus, HeLa cells were cotransfected with GFP-SUMO-1 and a plasmid containing the editing-competent murine GluR-B mini-gene B13 (Higuchi et al., 1993). Visualization of GluR-B mini-gene B13 by fluorescence in situ hybridization reveals staining of the nucleoplasm excluding the nucleolus (Figure 6A). In cells that express GluR-B mini-gene B13, endogenous ADAR1 becomes excluded from nucleolus (Figure 6B). However, in these cells the localization pattern of GFP-SUMO-1 in the nucleolus remains unaltered (Figure 6C). This suggests that distinct, not yet identified nuclear proteins modified by SUMO-1 colocalize with ADAR1 in the same subnucleolar compartment.

Figure 6.

ADAR1 is not the only nucleolar protein modified by SUMO-1. HeLa cells were cotransfected with a plasmid containing the editing competent murine GluR-B mini-gene B13 and GFP-SUMO-1 and immunolabeled with anti-ADAR1 antibodies. The GluR-B transcripts are visualized by fluorescence in situ hybridization (A), ADAR1 is detected by Ab668 (B), and SUMO is visualized by GFP fluorescence (C). Because editing is thought to occur cotranscriptionally and GluR-B RNAs are synthesized throughout the nucleoplasm, ADAR1 is recruited to GluR-B nascent transcripts and de-localizes from the nucleolus of cells transfected with the mini-gene B13. Despite the absence of ADAR1, GFP-SUMO-1 still concentrates in the nucleolus. The dashed lines indicate the contour of the nucleolus. Bar, 10 μm.

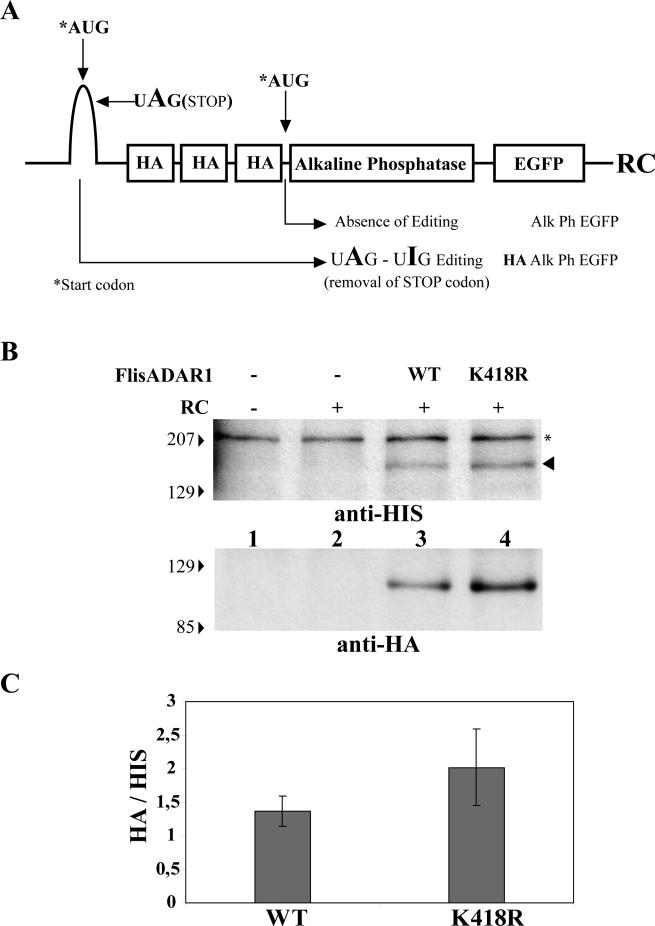

Modification of ADAR1 by SUMO-1 Reduces RNA-editing Activity

The ability of SUMO to directly affect the activity of an enzyme has only been described for the thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG). SUMO-1 conjugation of TDG reduces its DNA substrate binding affinity and induces higher enzymatic turnover (Hardeland et al., 2002). To investigate whether the modification of ADAR1 by SUMO-1 affects RNA-editing activity, we performed in vivo and in vitro experiments. First, we took advantage of the editing reporter construct described by Herbert et al. (2002). The RC reporter was designed with two start codons and a stop codon. The first start codon is not used under normal circumstances, and the stop codon is embedded in a short stretch of dsRNA that is recognized as an editing substrate by ADAR1. A-to-I editing converts the stop codon (UAG) into UIG, allowing translation from the first start codon. This results in production of a fusion protein that contains both HA and GFP tags. If the reporter mRNA is not edited, the stop codon is not eliminated and translation of the messenger starts in the second start codon giving rise to a GFP fusion protein that lacks the N-terminal HA tag (Figure 7A). Therefore, the expression of an HA-tagged fusion protein is editing-dependent. The RC construct was transfected into HeLa cells and the occurrence of editing was assayed by Western blot analysis with an anti-HA antibody. Cells were cotransfected with the RC reporter and either ADAR1-WT or ADAR1-K418R. Both forms of ADAR1 were C-terminally tagged with a HIS-epitope. No endogenous A-to-I editing of the RC reporter was detected in HeLa cells (Figure 7B, lane 2). In contrast, editing of the reporter was observed when either ADAR1-WT or ADAR1-K418R was exogenously expressed. Most important, in cells that express similar levels of ADAR1-WT and ADAR1-K418R (Figure 7, lanes 3 and 4, anti-HIS, arrowhead), the mutant enzyme produces more HA-tagged fusion protein than the wild-type enzyme (Figure 7, B, anti-HA, and C); thus preventing the attachment of SUMO to ADAR1 activates RNA editing, suggesting that sumoylation has an inhibitory effect on ADAR1-editing activity. According to this idea, we predicted that increasing the fraction of wild-type ADAR1 modified by SUMO-1 would further reduce editing of the reporter and consequently decrease the amount of HA-tagged fusion protein expressed in the cell. However, cotransfection of cells with a plasmid encoding SUMO-1 did not alter the expression level of the HA-fusion protein (unpublished data), most probably because overexpression of SUMO-1 is not sufficient to enhance sumoylation of ADAR1 in vivo. In fact, there is evidence that modification of proteins by SUMO is a tightly regulated process in the cell (Melchior et al., 2003; Marx, 2005).

Figure 7.

ADAR K418R has higher ability to edit the RC reporter construct than the WT protein. (A) Schematic representation of the RC-editing reporter construct. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids, and total cell extracts were prepared 24 h after transfection. Proteins were analyzed by Western blot with the indicated antibody. The anti-HIS antibody reveals that the expression levels of both ADAR1 forms are similar (arrowhead). A nonspecific band that appears with anti-HIS antibody is indicated with one asterisk (*). The HA signal indicates that ADAR1 K418R has higher editing activity. Molecular-weight markers (kDa) are shown on the left. (C) The relative intensity of the HA bands normalized for the intensity of ADAR1 WT and K418R bands (detected by anti-HIS antibody) was quantified in three independent experiments. Error bars, SD.

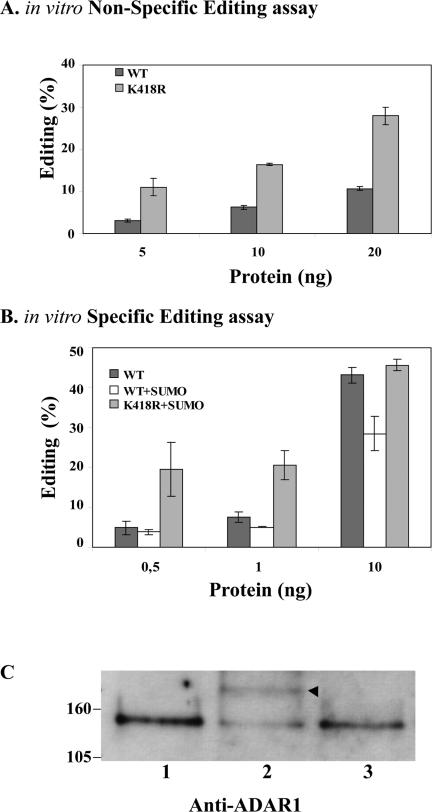

The labile nature of SUMO-1 modification due to the high activity of SUMO specific proteases and the absence of a mechanism to induce SUMO-1 modification in vivo do not facilitate the investigation of a direct effect of SUMO-1 on ADAR1 activity in the cell. We therefore decided to perform further studies using in vitro systems. Both ADAR1-WT and ADAR1-K418R were expressed in the yeast P. pastoris, and the recombinant proteins containing HIS and FLAG tags were purified to homogeneity by chromatography over both Ni2+-NTA and FLAG affinity matrices (Ring et al., 2004). Consistent with the in vivo data, the in vitro results indicate that recombinant ADAR1-WT is consistently less active than recombinant ADAR1-K418R in editing a long duplex RNA in a nonspecific assay (Figure 8A) (O'Connell and Keller, 1994). Western blot analysis of the recombinant proteins confirmed that a fraction of ADAR1-WT is modified by SUMO-1 (unpublished data). This observation prompted us to compare the editing activity of ADAR1-WT and ADAR1-K418R recombinant proteins on a specific substrate, the GluR-B mini-gene B13 (Figure 8B). A primer extension assay was performed in triplicate on a transcript encoded by the GluR-B mini-gene B13 (Higuchi et al., 1993). As clearly shown in Figure 8B, following in vitro modification of the recombinant proteins by SUMO-1, the editing activity of wild-type ADAR1, and not of the K418R mutant, is significantly reduced. A range of different amounts of recombinant proteins was tested in this assay and reproducible results were obtained (Figure 8B). Western blot analysis confirms the modification of ADAR1-WT (Figure 8C, lane 2), but not of the mutant ADAR1-K418R (Figure 8C, lane 3). Consistent with the view that sumoylation is not required for editing, addition of ATP is dispensable for recombinant ADAR1 activity in vitro (O'Connell and Keller, 1994), whereas if SUMO-1 modification was necessary ATP addition would be essential. Taken together these results support a direct role of SUMO-1 modification on reducing the RNA-editing activity of ADAR1.

Figure 8.

SUMO-1 modification inhibits ADAR1 editing activity. (A) The in vitro nonspecific editing assay was performed with either purified recombinant ADAR1-WT or ADAR1-K418R. Increasing amounts (5, 10, and 20 ng) of both proteins were assayed. The products of the assay were chromatographed on a TLC plate and quantified on a PhosphorImager. The graph shows the percentage of editing in three independent experiments for each protein. (B) A primer extension assay was performed to detect editing in a transcript encoding the GluR-B mini-gene B13 at the hotspot 1 site (Higuchi et al., 1993). Increasing amounts (0.5, 1.0, and 10 ng) of purified recombinant ADAR1-WT and ADAR1-K418R, or previously in vitro SUMO-1-modified proteins were incubated with the transcript. Each assay was performed in triplicates, and the products were analyzed on a 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The graph represents the average of percentage of editing after quantification of the primer extension assay; error bars, SD. C. Western blot analysis of 10 ng of ADAR1 proteins analyzed in the primer extension assay shown in B. Molecular-weight markers (kDa) are shown on the left and an arrowhead indicates SUMO-1 modified ADAR1.

DISCUSSION

Posttranslational modification of proteins by SUMO is known to play a regulatory role in many cellular processes, and the identification of novel SUMO-targeted proteins is currently attracting much attention (for recent reviews see Johnson, 2004; Melchior et al., 2003). In general, only a limited fraction of a certain protein is modified by SUMO in the cell, making it difficult to detect the low abundant pool of endogenously sumoylated proteins. In this study we show that GFP-tagged SUMO-1 accumulates in the nucleolus. In contrast, a GFP-tagged mutant version of SUMO-1 that lacks the C-terminal amino acids required for covalent attachment to target proteins fails to localize to the nucleolus (Figure 1, A and B). Similar results were very recently reported by Ayaydin and Dasso (2004) who observed that YFP-SUMO-1, but not YFP-SUMO-2 or YFP-SUMO-3, localizes to the nucleolus. This strongly suggests that a subset of nucleolar proteins is modified by SUMO. Interestingly, some of the enzymes involved in the sumoylation pathway have been previously localized to the nucleolus, namely the E3 SUMO-1 ligase PIAS1 (Valdez et al., 1997), and the SUMO/Smt3-1-specific isopeptidase SMT3IP1 (SENP3; Nishida et al., 2000; Leung et al., 2003). Thus, it is possible that certain protein targets are reversibly modified by SUMO-1 in the nucleolus.

Noteworthy, SUMO was not detected in recent MS studies on isolated nucleoli from HeLa cells (Scheer et al., 1993; Andersen et al., 2002). However, this is not surprising, taking into account that many endogenously sumoylated proteins are present at a level below normal detection limit. Moreover, sumoylation is a highly dynamic and reversible reaction, making it difficult to preserve SUMO conjugation during cell fractionation and subcellular purification procedures.

The nucleolus is a subnuclear compartment dedicated to the biogenesis of ribosomes. The nucleolus is where the rRNA genes are kept and transcribed and the rRNAs are processed and assembled with proteins to form preribosomes. However, an increasing body of evidence indicates that the nucleolus is not exclusively a ribosome factory, but plays additional roles in the cell. According to a current view, the nucleolus may act as a molecular “safe” or “sink” that regulates protein activity by sequestration (review Leung et al., 2003).

DNA topoisomerase I (topo I) is a nuclear protein that concentrates in the nucleolus and is modified by SUMO. However, topo I rapidly moves out of the nucleolus, and this nucleolar delocalization is associated with conjugation of the protein with SUMO (Mo et al., 2002). Thus, to date, no nucleolar proteins modified by SUMO were identified. In the present work we show that GFP-tagged SUMO-1 accumulates in a nucleolar region that is distinct from the well-characterized nucleolar domains involved in ribosomal biogenesis, i.e., the fibrillar center, the dense fibrillar component, and the granular component (Figure 1E). Rather, GFP-SUMO-1 colocalizes precisely with the RNA-editing enzyme ADAR1 (Figure 2). We further provide in vitro and in vivo evidence that human ADAR1 is modified by SUMO-1 on lysine residue 418 (Figures 3 and 4). Importantly, the nucleolar localization of GFP-SUMO-1 remains unaltered when ADAR1 is no longer detected in that compartment (Figure 6), arguing that SUMO-1 modifies additional protein substrates in the nucleolus.

Although ADAR1 colocalizes with ADAR2 in the nucleolus (Desterro et al., 2003), the ADAR2 protein lacks the amino-terminal region containing the SUMO conjugation site. Sequence analysis of ADAR2 does not reveal any SUMO-1 consensus motif and ADAR2 is not modified by SUMO-1 in vitro (unpublished data). Because both ADAR1 and ADAR2 concentrate in the nucleolus and only ADAR1 is modified by SUMO, it is unlikely that sumoylation of ADAR1 is required for targeting the enzyme to the nucleolus. According to this prediction, a mutant form of ADAR1 that is not sumoylated because it contains an arginine substitution of lysine 418 (ADAR1-K418R) localizes to the nucleolus similarly to the wild-type protein (Figure 5).

Our work further provides in vivo and in vitro evidence that modification of ADAR1 by SUMO reduces the RNA-editing activity of the enzyme. ADAR1 can edit RNAs both in a specific and nonspecific manner, depending on the nature of the substrate. ADAR1 can edit specific transcripts encoding receptor proteins of CNS and these can result in recoding events. The best studied specific mammalian substrates for ADAR1 are the pre-mRNAs encoding the serotonin HT-2c receptor and those encoding ionotropic glutamate receptor (GluR) subunits. However, more recent studies have identified widespread A-to-I RNA-editing sites in the human transcriptome (Athanasiadis et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2004; Levanon et al., 2004). Approximately 1500 human mRNAs were found to be subject to RNA editing at more than 13,000 sites that typically map in Alu repeats. Additionally, micro-RNA precursors have been shown to be modified by A-to-I editing (Luciano et al., 2004), and ADAR1 was implicated in gene silencing by short interfering RNA (Yang et al., 2005).

Here we show that the mutant form of ADAR1 that is not modified by SUMO (ADAR1-K418R) is more active than the wild-type enzyme in editing a reporter RNA in vivo, and modification of the wild-type enzyme by SUMO reduces editing of a GluR-B mini-gene B13 in vitro (Figures 7 and 8). This represents the first indication that sumoylation can contribute to regulate RNA-editing activity.

ADAR activity is known to be tightly regulated in different species. In vertebrates, ADARs shuttle between the cytoplasm, the nucleoplasm, and the nucleolus (Desterro et al., 2003; Sansam et al., 2003), and it is currently thought that sequestration in the nucleolus contributes to prevent aberrant editing activity in the nucleoplasm. On the basis of our observations that ADAR1 colocalizes with SUMO-1 in the nucleolus and that sumoylation of ADAR1 reduces editing activity, we propose that the nucleolus represents a “sink” for inactive ADAR1 in the cell. In agreement with this view, it has been recently reported that ADAR2-but not ADAR1-mediated RNA editing occurs in the nucleolus (Vitali et al., 2005). Considering that both ADAR1 and ADAR2 colocalize in the nucleolus, it was unexpected to find that ADAR1 does not perform nucleolar RNA editing. This apparent inconsistency can be explained by our findings suggesting that SUMO-1 conjugation renders ADAR1 inactive in the nucleolus while ADAR2 is not modified by SUMO.

Whether ADAR1 is preferentially sumoylated in the nucleolus remains to be established. Another important issue to be addressed concerns the mechanism by which sumoylation affects editing activity. Interestingly, ADAR enzymes act as a dimer and dimerization is essential for editing activity. It remains to be elucidated how the monomers bind to dsRNA and dimerize. Preliminary results for ADAR1 have shown that the N-terminal region containing the Z-DNA domain is not required as heterodimers can form between the p150 and p110 isoforms of ADAR1 (Cho et al., 2003). However, the minimum region required for the dimerization of Drosophila ADAR is the N-terminus including and the first dsRNA-binding domain (dsRBD; Gallo et al., 2003). Dimerization affects the enzymatic activity as well as substrate specificity of ADAR1 and ADAR2 and is essential for editing activity in Drosophila (Gallo et al., 2003). Considering that the SUMO-1 acceptor lysine lies between the Z-DNA and the first dsRBD one could consider SUMO as a stereochemical obstacle for both binding to the dsRNA and subsequent dimerization.

In conclusion, together with the recent finding that SUMO modifies several heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins, which are key players in mRNA biogenesis (Li et al., 2004), our results support a novel role for sumoylation in regulating RNA metabolism.

Acknowledgments

We thank Walter Keller (Biozentrum, Basel, Switzerland) for kindly providing anti-ADAR1 antibodies, Alan Herbert (Boston University School of Medicine) for the RC plasmid and G. Del Sal for the GFP-SUMO plasmid constructs (Laboratorio Nazionale Consorzio Interuniversitario Biotecnologie, Trieste, Italy). This study was supported by grants from “Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, POCTI/36547/MGI/00” (Portugal), the European Commission “QLG2-CT-2001-01554” and the MRC (United Kingdom).

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E05–06–0536) on August 24, 2005.

Abbreviations used: SUMO, small ubiquitin modifier; ADAR, adenosine deaminase that act on RNA; SAE, SUMO-activating enzyme; UBC9, SUMO-conjugating enzyme.

References

- Andersen, J. S., Lyon, C. E., Fox, A. H., Leung, A. K., Lam, Y. W., Steen, H., Mann, M., and Lamond, A. I. (2002). Directed proteomic analysis of the human nucleolus. Curr. Biol. 12, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athanasiadis, A., Rich, A., and Maas, S. (2004). Widespread A-to-I RNA editing of Alu-containing mRNAs in the human transcriptome. PLoS Biol. 2, e391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayaydin, F., and Dasso, M. (2004). Distinct in vivo dynamics of vertebrate SUMO paralogues. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 5208–5218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma, Y., and Dasso, M. (2002). A new clue at the nuclear pore: RanBP2 is an E3 enzyme for SUMO1. Dev. Cell 2, 130–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B. L. (2002). RNA editing by adenosine deaminases that act on RNA. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 817–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer, P., Arndt, A., Metzger, S., Mahajan, R., Melchior, F., Jaenicke, R., and Becker, J. (1998). Structure determination of the small ubiquitin-related modifier SUMO-1. J. Mol. Biol. 280, 275–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beghini, A., Ripamonti, C. B., Peterlongo, P., Roversi, G., Cairoli, R., Morra, E., and Larizza, L. (2000). RNA hyperediting and alternative splicing of hematopoietic cell phosphatase (PTPN6) gene in acute myeloid leukemia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 2297–2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohren, K. M., Nadkarni, V., Song, J. H., Gabbay, K. H., and Owerbach, D. (2004). A M55V polymorphism in a novel SUMO gene (SUMO-4) differentially activates heat shock transcription factors and is associated with susceptibility to type I diabetes mellitus. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 27233–27238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calado, A., Kutay, U., Kuhn, U., Wahle, E., and Carmo-Fonseca, M. (2000). Deciphering the cellular pathway for transport of poly(A)-binding protein II. RNA 6, 245–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmo-Fonseca, M., Mendes-Soares, L., and Campos, I. (2000). To be or not to be in the nucleolus. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, E107–E112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho, D. S., Yang, W., Lee, J. T., Shiekhattar, R., Murray, J. M., and Nishikura, K. (2003). Requirement of dimerization for RNA editing activity of adenosine deaminases acting on RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 17093–17102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desterro, J. M., Keegan, L. P., Lafarga, M., Berciano, M. T., O'Connell, M., and Carmo-Fonseca, M. (2003). Dynamic association of RNA-editing enzymes with the nucleolus. J. Cell Sci. 116, 1805–1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desterro, J. M., Thomson, J., and Hay, R. T. (1997). Ubch9 conjugates SUMO but not ubiquitin. FEBS Lett. 417, 297–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duda, D. M., and Schulman, B. A. (2005). Tag-team SUMO wrestling. Mol. Cell 18, 612–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, A., Keegan, L. P., Ring, G. M., and O'Connell, M. A. (2003). An ADAR that edits transcripts encoding ion channel subunits functions as a dimer. EMBO J. 22, 3421–3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George, C. X., and Samuel, C. E. (1999a). Characterization of the 5′-flanking region of the human RNA-specific adenosine deaminase ADAR1 gene and identification of an interferon-inducible ADAR1 promoter. Gene 229, 203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George, C. X., and Samuel, C. E. (1999b). Human RNA-specific adenosine deaminase ADAR1 transcripts posses alternative exon1 structures that initiate from different promoters, one constitutively active and the other interferon inducible. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 4621–4626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gostissa, M., Hengstermann, A., Fogal, V., Sandy, P., Schwarz, S. E., Scheffner, M., and Del Sal, G. (1999). Activation of p53 by conjugation to the ubiquitin-like protein SUMO-1. EMBO J 18, 6462–6471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeland, U., Steinacher, R., Jiricny, J., and Schar, P. (2002). Modification of the human thymine-DNA glycosylase by ubiquitin-like proteins facilitates enzymatic turnover. EMBO J 21, 1456–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay, R. T. (2001). Protein modification by SUMO. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26, 332–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay, R. T. (2005). SUMO: a history of modification. Mol. Cell 18, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, A., Wagner, S., and Nickerson, J. A. (2002). Induction of protein translation by ADAR1 within living cell nuclei is not dependent on RNA editing. Mol. Cell 5, 1235–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, M., Maas, S., Single, F. N., Hartner, J., Rozov, A., Burnashev, N., Feldmeyer, D., Sprengel, R., and Seeburg, P. H. (2000). Point mutation in an AMPA receptor gene rescues lethality in mice deficient in the RNA-editing enzyme ADAR2. Nature 406, 78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, M., Single, F. N., Kohler, M., Sommer, B., Sprengel, R., and Seeburg, P. H. (1993). RNA editing of AMPA receptor subunit GluR-B: a base-paired intron-exon structure determines position and efficiency. Cell 75, 1361–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E. S. (2004). Protein modification by SUMO. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 355–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E. S., Schwienhorst, I., Dohmen, R. J., and Blobel, G. (1997). The ubiquitin-like protein Smt3p is activated for conjugation to other proteins by an Aos1p/Uba2p heterodimer. EMBO J. 16, 5509–5519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagey, M. H., Melhuish, T. A., and Wotton, D. (2003). The polycomb protein Pc2 is a SUMO E3. Cell 113, 127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keegan, L. P., Gallo, A., and O'Connell, M. (2001). The many roles of an RNA editor. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 869–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keegan, L. P., Leroy, A., Sproul, D., and O'Connell, M. A. (2004). Adenosine deaminases acting on RNA (ADARs): RNA-editing enzymes. Genome Biol. 5, 209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D. D., Kim, T. T., Walsh, T., Kobayashi, Y., Matise, T. C., Buyske, S., and Gabriel, A. (2004). Widespread RNA editing of embedded alu elements in the human transcriptome. Genome Res. 14, 1719–1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung, A. K., Andersen, J. S., Mann, M., and Lamond, A. I. (2003). Bioinformatic analysis of the nucleolus. Biochem. J. 376, 553–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levanon, E. Y. et al. (2004). Systematic identification of abundant A-to-I editing sites in the human transcriptome. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 1001–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. J., and Hochstrasser, M. (1999). A new protease required for cell-cycle progression in yeast. Nature 398, 246–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. J., and Hochstrasser, M. (2000). The yeast ULP2 (SMT4) gene encodes a novel protease specific for the ubiquitin-like Smt3 protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 2367–2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, T., Evdokimov, E., Shen, R. F., Chao, C. C., Tekle, E., Wang, T., Stadtman, E. R., Yang, D. C., and Chock, P. B. (2004). Sumoylation of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins, zinc finger proteins, and nuclear pore complex proteins: a proteomic analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 8551–8556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciano, D. J., Mirsky, H., Vendetti, N. J., and Maas, S. (2004). RNA editing of a miRNA precursor. RNA 10, 1174–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx, J. (2005). Cell biology. SUMO wrestles its way to prominence in the cell. Science 307, 836–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcher, T., Maas, S., Higuchi, M., Keller, W., and Seeburg, P. H. (1995). Editing of alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid receptor GluR-B pre-mRNA in vitro reveals site-selective adenosine to inosine conversion. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 8566–8570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchior, F., Schergaut, M., and Pichler, A. (2003). SUMO: ligases, isopeptidases and nuclear pores. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28, 612–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo, Y.-Y., Yu, Y., Shen, Z., and Beck, W. T. (2002). Nucleolar delocalization of human topoisomerase I in response to topotecan correlates with sumoylation of the protein. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 2958–2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse, D. P., and Bass, B. L. (1999). Long RNA hairpins that contain inosine are present in Caenorhabditis elegans poly(A)+ RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 6048–6053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossessova, E., and Lima, C. D. (2000). Ulp1-SUMO crystal structure and genetic analysis reveal conserved interactions and a regulatory element essential for cell growth in yeast. Mol. Cell 5, 865–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida, T., Tanaka, H., and Yasuda, H. (2000). A novel mammalian Smt3-specific isopeptidase (SMT3IP1) localized in the nucleolus at interphase. Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 6423–6427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell, M. A., and Keller, W. (1994). Purification and properties of double-stranded RNA-specific adenosine deaminase from calf thymus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 10596–10600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Mahony, D. J., Xie, W. Q., Smith, S. D., Singer, H. A., and Rothblum, L. I. (1992). Differential phosphorylation and localization of the transcription factor UBF in vivo in response to serum deprivation. In vitro dephosphorylation of UBF reduces its transactivation properties. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palladino, M. J., Keegan, L. P., O'Connell, M. A., and Reenan, R. A. (2000a). dADAR, a Drosophila double-stranded RNA-specific adenosine deaminase is highly developmentally regulated and is itself a target for RNA editing. RNA 6, 1004–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palladino, M. J., Keegan, L. P., O'Connell, M. A., and Reenan, R. A. (2000b). A-to-I pre-mRNA editing in Drosophila is primarily involved in adult nervous system function and integrity. Cell 102, 437–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, J. B., and Samuel, C. E. (1995). Expression and regulation by interferon of a double-stranded-RNA-specific adenosine deaminase from human cells: evidence for two forms of the deaminase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 5376–5388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichler, A., Gast, A., Seeler, J. S., Dejean, A., and Melchior, F. (2002). The nucleoporin RanBP2 has SUMO1 E3 ligase activity. Cell 108, 109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polson, A. G., Bass, B. L., and Casey, J. L. (1996). RNA editing of hepatitis delta virus antigenome by dsRNA-adenosine deaminase. Nature 380, 454–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen, H., Nilsson, J., Damgaard, C. K., Egebjerg, J., and Kjems, J. (2001). CRM1 mediates the export of ADAR1 through a nuclear export signal within the Z-DNA binding domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 7862–7871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimer, G., Raska, I., Tan, E. M., and Scheer, U. (1987). Human autoantibodies: probes for nucleolus structure and function. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol. Incl. Mol. Pathol. 54, 131–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reverter, D., and Lima, C. D. (2005). Insights into E3 ligase activity revealed by a SUMO-RanGAP1-Ubc9-Nup358 complex. Nature 435, 687–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ring, G. M., O'Connell, M. A., and Keegan, L. P. (2004). Purification and assay of recombinant ADAR proteins expressed in the yeast Pichia pastoris or in Escherichia coli. Methods Mol. Biol. 265, 219–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, M. S., Dargemont, C., and Hay, R. T. (2001). SUMO-1 conjugation in vivo requires both a consensus modification motif and nuclear targeting. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 12654–12659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, M. S., Desterro, J. M., Lain, S., Midgley, C. A., Lane, D. P., and Hay, R. T. (1999). SUMO-1 modification activates the transcriptional response of p53. EMBO J. 18, 6455–6461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueter, S. M., Dawson, T. R., and Emeson, R. B. (1999). Regulation of alternative splicing by RNA editing. Nature 399, 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev, S., Bruhn, L., Sieber, H., Pichler, A., Melchior, F., and Grosschedl, R. (2001). PIASy, a nuclear matrix-associated SUMO E3 ligase, represses LEF1 activity by sequestration into nuclear bodies. Genes Dev. 15, 3088–3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh, H., and Hinchey, J. (2000). Functional heterogeneity of small ubiquitin-related protein modifiers SUMO-1 versus SUMO-2/3. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 6252–6258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansam, C. L., Wells, K. S., and Emeson, R. B. (2003). Modulation of RNA editing by functional nucleolar sequestration of ADAR2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 14018–14023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaub, M., and Keller, W. (2002). RNA editing by adenosine deaminases generates RNA and protein diversity. Biochemie 84, 791–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer, U., Thiry, M., and Goessens, G. (1993). Structure, function and assembly of the nucleolus. Trends Cell Biol. 3, 236–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeler, J. S., and Dejean, A. (2003). Nuclear and unclear functions of SUMO. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4, 690–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternsdorf, T., Jensen, K., and Will, H. (1997). Evidence for covalent modification of the nuclear dot-associated proteins PML and Sp100 by PIC1/SUMO-1. J. Cell Biol. 139, 1621–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, K., Nishide, J., Okazaki, K., Kato, H., Niwa, O., Nakagawa, T., Matsuda, H., Kawamukai, M., and Murakami, Y. (1999). Characterization of a fission yeast SUMO-1 homologue, pmt3p, required for multiple nuclear events, including the control of telomere length and chromosome segregation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 8660–8672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatham, M. H., Jaffray, E., Vaughan, O. A., Desterro, J. M., Botting, C. H., Naismith, J. H., and Hay, R. T. (2001). Polymeric chains of SUMO-2 and SUMO-3 are conjugated to protein substrates by SAE1/SAE2 and Ubc9. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 35368–35374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatham, M. H., Kim, S., Jaffray, E., Song, J., Chen, Y., and Hay, R. T. (2005). Unique binding interactions among Ubc9, SUMO and RanBP2 reveal a mechanism for SUMO paralog selection. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez, B. C., Henning, D., Perlaky, L., Busch, R. K., and Busch, H. (1997). Cloning and characterization of Gu/RH-II binding protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 234, 335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitali, P., Basyuk, E., Le Meur, E., Bertrand, E., Muscatelli, F., Cavaille, J., and Huttenhofer, A. (2005). ADAR2-mediated editing of RNA substrates in the nucleolus is inhibited by C/D small nucleolar RNAs. J. Cell Biol. 169, 745–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W., Wang, Q., Howell, K. L., Lee, J. T., Cho, D. S., Murray, J. M., and Nishikura, K. (2005). ADAR1 RNA deaminase limits short interfering RNA efficacy in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 3946–3953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H., Saitoh, H., and Matunis, M. J. (2002). Enzymes of the SUMO modification pathway localize to filaments of the nuclear pore complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 6498–6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]