Abstract

By using natural-abundance 13C-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis we have investigated the types of compatible solutes that are synthesized de novo in a variety of Bacillus species under high-osmolality growth conditions. Five different patterns of compatible solute production were found among the 13 Bacillus species we studied. Bacillus subtilis, B. licheniformis, and B. megaterium produced proline; B. cereus, B. circulans, B. thuringiensis, Paenibacillus polymyxa, and Aneurinibacillus aneurinilyticus synthesized glutamate; B. alcalophilus, B. psychrophilus, and B. pasteurii synthesized ectoine; and Salibacillus (formerly Bacillus) salexigens produced both ectoine and hydroxyectoine, whereas Virgibacillus (formerly Bacillus) pantothenticus synthesized both ectoine and proline. Hence, the ability to produce the tetrahydropyrimidine ectoine under hyperosmotic growth conditions is widespread within the genus Bacillus and closely related taxa. To study ectoine biosynthesis within the group of Bacillus species in greater detail, we focused on B. pasteurii. We cloned and sequenced its ectoine biosynthetic genes (ectABC). The ectABC genes encode the diaminobutyric acid acetyltransferase (EctA), the diaminobutyric acid aminotransferase (EctB), and the ectoine synthase (EctC). Together these proteins constitute the ectoine biosynthetic pathway, and their heterologous expression in B. subtilis led to the production of ectoine. Northern blot analysis demonstrated that the ectABC genes are genetically organized as an operon whose expression is strongly enhanced when the osmolality of the growth medium is raised. Primer extension analysis allowed us to pinpoint the osmoregulated promoter of the B. pasteurii ectABC gene cluster. HPLC analysis of osmotically challenged B. pasteurii cells revealed that ectoine production within this bacterium is finely tuned and closely correlated with the osmolality of the growth medium. These observations together with the osmotic control of ectABC transcription suggest that the de novo synthesis of ectoine is an important facet in the cellular adaptation of B. pasteurii to high-osmolarity surroundings.

One of the most important parameters affecting the growth of microorganisms is the availability of water in their habitat. Bacteria can colonize a wide variety of ecological niches with a considerable spectrum of osmotic conditions (51), and within a single habitat there also can be drastic fluctuations from the prevalent osmotic milieu. Microorganisms lack the ability to actively transport water in or out of the cell, and osmotic processes consequently determine their water content. They must, therefore, actively manage their intracellular solute pool to prevent dehydration or rupture (6).

To cope with hyperosmotic conditions, microorganisms amass large quantities of a particular group of organic osmolytes, the so-called compatible solutes (15, 20), and they expel these compounds when they are exposed to hypoosmotic circumstances (1, 34). Their accumulation, either through de novo synthesis or by direct uptake from the environment, is an evolutionarily well-conserved adaptation strategy in microorganisms for adjusting to high-osmolality surroundings (8). Compatible solutes are operationally defined as organic osmolytes that can be amassed by the cell in exceedingly high concentrations (up to several moles per liter) without disturbing vital cellular functions and the correct folding of proteins (9). Therefore, compatible solutes can make important contributions to the restoration of turgor under conditions of low water activity by counteracting the efflux of water from the cell. In addition, they have a stabilizing influence, both in vivo (7) and in vitro (36), on the native structure of proteins and cell components. These beneficial effects result from the unfavorable interactions of compatible solutes with the polypeptide backbone (43) and the concomitant preferential exclusion of these compounds from the immediate hydration shells of proteins (4). The types of compounds that serve as compatible solutes are by and large the same across the kingdoms, reflecting fundamental constraints on the kinds of solutes that are congruous with macromolecular and cellular functions. Most compatible solutes within the group of the Bacteria are highly soluble molecules and do not carry a net charge at physiological pH (20). Important representatives of this class of molecules are the amino acid proline, the trimethylammonium compound glycine betaine, and the tetrahydropyrimidine ectoine.

The challenge posed by changing environmental osmolality is vividly illustrated by the common habitat of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis, the upper layers of the soil. Drought and rain drastically alter the osmotic conditions within this ecosystem (38) and threaten the cell with dehydration or rupture as water permeates across the cytoplasmic membrane along the osmotic gradient. The initial response of this bacterium to a sudden increase in the external osmolality is the uptake of large quantities of K+ to counteract the immediate outflow of water from the cell (53, 54). However, because a prolonged high intracellular concentration of K+ is detrimental to many physiological functions, B. subtilis then partially replaces this ion by synthesizing a large amount of proline (53) via an osmoresponsive synthesis pathway (J. Brill and E. Bremer, unpublished results). In addition, it takes up a considerable variety of preformed osmoprotectants directly from the environment (28-31, 35, 39) via five osmoregulated transport systems, the Opu family of transporters (8, 32).

The identification of B. subtilis as a proline producer under conditions of osmotic stress (53) prompted the question of whether most other members of the genus Bacillus synthesize proline as their dominant endogenous osmoprotectant. Although the experimental details have not yet been published, Galinski and Trüper (20) mentioned in their overview on microbial behavior in salt-stressed ecosystems that several Bacillus species can produce ectoine under hypertonic conditions. Here we report on our investigation of compatible solute synthesis within the genus Bacillus and closely related taxa. Our data strongly suggest that the ability to synthesis ectoine as an osmostress protectant is widespread among the members of the genus Bacillus. We conducted a detailed physiological and molecular analysis of ectoine biosynthesis in Bacillus pasteurii and found that transcription of the ect genes in this species is under osmotic control and that these genes code for an evolutionarily highly conserved biosynthesis pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The B. subtilis strain JH642 (trpC2 pheA1; BGSC 1A96; a kind gift from J. Hoch) is a derivative of the B. subtilis wild-type strain 168. The B. subtilis strain KE30 [Φ(yckH-comS-erm-ycxA)(amyE"-cat-pspac-comS-lacI-"amyE)] (18) was a kind gift from M. Marahiel. B. pasteurii (DSM 33T), B. alcalophilus (DSM 485T), B. licheniformis (DSM 13T), B. megaterium (DSM 32T), B. psychrophilus (DSM 3T), B. cereus (DSM 31T), B. thuringiensis (DSM 2046T), Aneurinibacillus aneurinilyticus (DSM 5562T), Paenibacillus polymyxa (DSM 36T), Salibacillus salexigens (DSM 11483T), and Virgibacillus pantothenticus (DSM 26T) were purchased from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany). Plasmids constructed by recombinant procedures were introduced by electrotransformation into the Escherichia coli strain DH5α (GIBCO BRL, Eggenstein, Germany), and the resulting strains were propagated on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium containing an appropriate antibiotic. The E. coli strain MC4100 has been described previously (13).

Media, chemicals, and growth conditions.

The B. subtilis strain JH642, B. licheniformis (DSM 13T), B. megaterium (DSM 32T), B. psychrophilus (DSM 3T), B. cereus (DSM 31T), B. thuringiensis (DSM 2046T), A. aneurinilyticus (DSM 5562T), P. polymyxa (DSM 36T), and V. pantothenticus (DSM 26T) were maintained and propagated on LB agar plates. B. pasteurii (DSM 33T) was propagated on LB agar plates containing 2% urea, and B. alcalophilus (DSM 485T) was grown on LB agar plates with a 100 mM Na-sesquicarbonate solution (pH 9.7). S. salexigens (DSM 11483T) was propagated on the rich medium described by Garabito et al. (21). Spizizen’s minimal medium (SMM) with 0.5% glucose as the sole carbon source, l-tryptophane (20 mg liter−1), l-phenylalanine (18 mg liter−1), and a solution of trace elements (24) was used for the growth of the B. subtilis strain JH642. B. licheniformis (DSM 13T), B. megaterium (DSM 32T), B. psychrophilus (DSM 3T), B. cereus (DSM 31T), B. circulans (DSM 9T), B. thuringiensis (DSM 2046T), A. aneurinilyticus (DSM 5562T), P. polymyxa (DSM 36T), and V. pantothenticus (DSM 26T) were grown in SMM containing 0.5% glucose and a solution of trace elements (24) supplemented by an amino acid stock solution (10 ml liter−1) consisting of dl-alanine (400 mg liter−1), l-asparagine (800 mg liter−1), dl-serine (100 mg liter−1), l-cystine (100 mg liter−1), l-tryptophane (80 mg liter−1), l-histidine (130 mg liter−1), l-phenylalanine (200 mg liter−1), dl-valine (500 mg liter−1), l-lysine (500 mg liter−1), dl-methionine (200 mg liter−1), dl-isoleucine (500 mg liter−1), dl-leucine (500 mg liter−1), and l-arginine (400 mg liter−1). In addition, a vitamin stock solution (10 ml liter−1) consisting of biotin (25 mg liter−1), nicotinic acid (50 mg liter−1), pantothenic acid (50 mg liter−1), thiamine (50 mg liter−1), pyridoxine (50 mg liter−1), p-aminobenzoic acid (50 mg liter−1), lipoic acid (50 mg liter−1), folic acid (50 mg liter−1), and cobalamin (B12) (1 mg liter−1) was added to the growth medium. B. pasteurii (DSM 33T) was grown in a solution containing SMM with 2% urea, 0.5% glucose, the amino acid stock solution (10 ml liter−1), the vitamin stock solution (10 ml liter−1), l-aspartic acid (20 mg liter−1), and l-glutamic acid (60 mg liter−1). B. alcalophilus (DSM 485T) was grown in SMM supplemented with a 100 mM Na-sesquicarbonate solution (pH 9.7) and 0.5% glucose and the amino acid and vitamin stock solutions (10 ml liter−1 each). S. salexigens (DSM 11483T) was grown in a mineral-salt-based medium (21) supplemented with 0.5% glucose and the amino acid and vitamin stock solutions (10 ml liter−1 each) described above.

The osmotic strength of SMM was increased by the addition of NaCl, KCl, sucrose, lactose, and glycerol from stock solutions. The osmolality values of these media were determined with a vapor pressure osmometer (model 5500; Wescor). The osmolality of SMM is 340 mosmol/kg of water, and that of SMM with the addition of 0.4, 0.5, 1, and 1.5 M NaCl, respectively, was 1,100, 1,290, 2,240, and 3,190 mosmol/kg of water. The osmolality of SMM with 2% urea is 680 mosmol/kg of water. The osmolality of SMM (with 2% urea) containing 0.4, 0.5, 1, 1.5, or 2 M NaCl was 1,440, 1,630, 2,580, 3,530, or 4,480 mosmol/kg of water, respectively.

The antibiotics ampicillin and chloramphenicol were used with E. coli cultures at final concentrations of 100 and 30 μg ml−1, respectively. Radiolabeled [1-14C]glycine betaine (55 mCi/mmol) was purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals Inc. (St. Louis, Mo.). (S)-β-2-methyl-1,4,5,6-tetrahydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (ectoine) and (S,S)-β-2-methyl-5-hydroxy-1,4,5,6-tetrahydropyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid (hydroxyectoine) were purchased from BIOMOL (Hamburg, Germany). 2H2O containing D4-3-(trimethylsilyl)propionate as a standard was obtained from Aldrich (Deisenhofen, Germany).

Methods used with nucleic acids.

Routine manipulations of plasmid DNA, PCR, the construction of recombinant plasmids, the isolation of chromosomal DNA from B. pasteurii (DSM 33T), and the detection of homologous sequences by Southern hybridization with digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled DNA probes were carried out using routine procedures (45). The nucleotide sequence of the ectABC region from B. pasteurii was determined by the chain termination method of Sanger et al. (46) with the Thermo Sequenase fluorescent-labeled primer cycle sequencing kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany). The reaction mixtures were primed with synthetic oligonucleotides labeled at their 5" end with the infrared dye IRD-800 (MWG-Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany), and the products were analyzed on a LI-COR DNA sequencer (model 4000; MWG-Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany).

To isolate a fragment of the ectABC operon from B. pasteurii (DSM 33T), a PCR strategy with degenerate primers was used. To design the primers for the PCRs, the amino acid sequences of ectABC genes from Halmonas elongata (DSM 2581T) (22) and Marinococcus halophilus DSM (20408T) (37) were aligned to identify well-conserved regions within the Ect proteins. Two primers corresponding to segments in either ectA or ectC were designed. The ectA primer (AK1) had the following sequence: 5"-GATACC(G/T)(A/T)(G/T)TT(C/T)(A/G/C/T)TCTGGGAGGT-3"; the ectC primer (AK4) had the following sequence: 5"-TA(G/C)(C/T)(A/G/C/T)GATGTGIGTITCIGTACC-3". Primers AK1 and AK4 were used for PCR performed with chromosomal DNA of B. pasteurii (DSM 33T) as a template under low-stringency conditions (annealing temperature, 45°C). The resulting 1.4-kb PCR fragment was cloned by using the TA cloning kit containing the vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen, Groningen, The Netherlands). One of the resulting plasmids was named pSPICE1. The amplified DNA segment was 500 bp shorter than the size (1.9 kb) predicted from the choice of the primer combination. When the entire DNA sequence of the 1.4-kb insert from pSPICE1 was determined, we found that it contained the 3" end of ectB and the 5" end of ectC. Due to the low-stringency PCR conditions, primer AK1 had not bound to the ectA gene of B. pasteurii (DSM 33T) but rather to a segment in ectB, whereas the ectC primer had bound to the expected DNA segment.

To clone the complete ectABC operon, chromosomal DNA from B. pasteurii (DSM 33T) was digested with various restriction enzymes and was hybridized with the DIG-labeled "ectB-ectC" DNA probe (1.4 kb) derived from plasmid pSPICE1. One of the genomic fragments that reacted with the DNA probe was a 3.5-kb EcoRI fragment. To clone this fragment, genomic EcoRI restriction fragments of the appropriate size (3 to 4 kb) were obtained from preparative agarose gels and were ligated into the low-copy-number plasmid pHSG575 (Cmr) (49) linearized with EcoRI. This limited gene library was transformed into the E. coli strain DH5α, and the resulting transformants were grouped into 10 pools of 50 colonies each. Plasmid DNA was then isolated from the pools of these transformants and was subjected to Southern hybridization with the "ectB-ectC" fragment from pSPICE1 as a probe. Plasmid DNA from colonies from a positive-reacting pool were then tested individually in Southern hybridization experiments, finally resulting in the isolation of the ectABC+ plasmid pSPICE2. A 444-bp XhoI-ClaI restriction fragment carrying an internal ectB fragment was isolated from plasmid pSPICE2 and inserted into the XhoI and ClaI sites of pBluescript (SK−) (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), yielding plasmid pAK1. This plasmid was then used to prepare an RNA probe under the control of the phage T7 promoter for Northern blotting experiments. To test whether the B. pasteurii ectABC genes were expressed in B. subtilis, the chromosomal insert from pSPICE2 was cut out by EcoRI digestion and was inserted into the EcoRI site of low-copy-number plasmid pJMB1 (Cmr) (M. Jebbar and E. Bremer, unpublished results) that allows the integration of a genomic DNA fragment into the amyE locus of B. subtilis via homologous recombination. The resulting plasmid pAK8 was linearized by being cut with ClaI and was transformed into strain JH642; strains that carried the ectABC genes inserted into the amyE locus were identified as Cmr AmyE− colonies on starch plates as described previously (47). One of these colonies was purified for further analysis and was named AKB2.

To functionally express the ectABC genes from B. pasteurii in B. subtilis, we first amplified the entire ectABC gene cluster with the Master Amp Taq DNA polymerase Mix (Epicentre Technologies, Madison, Wis.) by using two synthetic oligonucleotides (5"-AACCATGGTTTGGGTAATAAGTAAGC-3", bp 1 to bp 22 of the ectA gene; 5"-AAGGATCCGCAGCTTGTATTAGTATC-3", bp 2641 to 2659 downstream of the ectC gene). The resulting 2,675-bp PCR fragment was then cut with NcoI and BamHI (these sites [underlined sequences] are present in the primers used for the PCR amplification) and cloned into the expression plasmid pSD270 carrying the T5 PN25 phage promoter (S. Doekel, K. Eppelmann, and M. A. Marahiel, unpublished results) resulting in plasmid pAK13. Plasmid pAK13 was linearized with XbaI and SpeI and was transformed into the B. subtilis strain KE30 by selecting for kanamycin-resistant transformants, resulting in the integration of the ectABC genes positioned under the control of the T5 PN25 phage promoter into the chromosome (in the adjacent yckH and ycxA genes) of the B. subtilis strain KE30. One of the resulting transformants was strain AKB4 [Φ(yckH-kan-comS-PT5/N25-ectABC-ycxA)(amyE"-cat-pspac-comS-lacI-"amyE)]. In this strain, ectABC transcription is positioned under the control of the phage T5 PN25 promoter and can be induced by adding isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (1 mM) to the culture.

Northern blot and primer extension analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from B. pasteurii cultures grown to log phase (optical density at 578 nm [OD578], 0.4 to 0.6) either in SMM (with 2% urea) or SMM (with 2% urea) containing 0.5 M NaCl by using the Total RNA Midi Kit (Qiagen, Hagen, Germany). Approximately 5 μg of total RNA was denatured at 95°C and was electrophoretically separated on a 1% agarose gel. The size-separated RNA was transferred to a Schleicher & Schuell NY13N nylon membrane and was hybridized with a DIG-labeled single-strand RNA probe specific for part of ectB. To prepare the RNA probe, plasmid pAK1 ('ectB'; a 444-bp XhoI-ClaI fragment) was linearized by cleavage with Acc65I in the vector portion of pAK1, and the DNA was then purified by using a spin column (Qiagen). The ectB RNA probe was prepared from plasmid pAK1 by using the DIG RNA labeling kit and T3 RNA polymerase (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). One microgram of purified DNA was used for the RNA labeling reaction by the T3 RNA polymerase. RNA-RNA hybridization was performed at 72°C with approximately 1 μg of the DIG-labeled RNA probe per ml of hybridization solution (50% formamide, 5× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 2% blocking reagent [Roche Diagnostics], 0.1% N-laurylsarcosine, 7% sodium dodecyl sulfate). The membrane filters were then washed and incubated with the chemiluminescent reagent ECF-Vistra (12 μl/cm2 blot; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany). For signal detection the PhosphorImager Storm 860 was used.

Primer extension analysis of the ectABC transcript was carried out using 10 μg of total RNA isolated from log phase cultures (OD578, 0.4 to 0.6) of B. pasteurii cells grown in SMM (with 2% urea) or SMM (with 2% urea) with 1.5 M NaCl. An ectA-specific primer (5"-CCATATTGCTTTGCCGTCATCTTCCG-3"; bp 492 to 517) labeled at its 5" end with the infrared dye IRD-800 (MWG) was hybridized at 75°C to the total RNA. The reaction mixture was slowly cooled to 42°C, and the primer was then extended with avian myoblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Promega) in the presence of 0.32 mM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at 42°C for 1 h. The nucleic acids were precipitated with ice-cold ethanol (100%) in the presence of 1 μl of glycogen (10 mg/ml), resuspended in 6 μl of sequencing stop solution, and heated for 10 min at 95°C. This solution (1.5 μl) was applied to a 6% sequencing gel, and the reaction products were analyzed on a LI-COR DNA sequencer. A sequencing ladder produced with the same ectA primer was run in parallel to determine the position of the 5" end of the ectABC mRNA.

Preparation of cell extracts for 13C-NMR spectroscopy.

Cultures (600 ml) of the different Bacillus strains were grown overnight in 2-liter Erlenmeyer flasks on a rotary shaker (220 rpm) in SMM with the required supplements for each strain. The osmolality of these cultures was raised by the addition of NaCl from a 5 M stock solution. In general the strains were propagated at 37°C, except for B. psychrophilus, which was grown at 25°C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation when the cultures reached an OD578 of between 2 and 2.4. The cells were washed once with 150 ml of growth medium without the supplements, and the cell pellet was then extracted with 20 ml of 80% (vol/vol) ethanol. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation in an Eppendorf tabletop centrifuge at 15,000 rpm, and the supernatant was evaporated to dryness. The ethanolic cell extracts were subsequently dissolved in 1 ml of 2H2O containing 1.2 mg of D4-3-(trimethylsilyl) propionate as internal standard. 13C-nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded with a Bruker AC300 spectrometer operating at 75 MHz (39). 13C-NMR tracings from l-ectoine, l-hydroxyectoine, l-proline, and l-glutamate were recorded as references to permit unambiguous identification of the resonances originating from these compounds in the 13C-NMR spectra recorded from the ethanolic cell extracts.

HPLC analysis of ectoine and glutamate.

Cells for isocratic high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of ectoine and hydroxyectoine were extracted using a modified Bligh and Dyer technique (33). Cultures of B. pasteurii (DSM 33T) were grown in minimal media of different osmolalities until they reached an OD578 of approximately 1. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and were lyophilized, the dry weight of the cells was determined, and the cells were then extracted with 400 μl of an extraction mixture (methanol/chloroform/water, 10:5:4 [vol/vol/vol]) by vigorous shaking for 60 min. Equal volumes (130 μl) of chloroform and water were then added. The mixture was again shaken for 30 min; phase separation was enhanced by centrifugation in an Eppendorf tabletop centrifuge at 13,000 rpm for 30 min. The water phase containing the compatible solute and other soluble material was recovered and lyophilized. The pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of water and 400 μl of acetonitrile (ACN); if necessary, this suspension was diluted to suitable concentrations in 80% (vol/vol) ACN and was used for HPLC analysis. Twenty microliters of each sample was analyzed on a GROM-SIL 100 Amino-1PR, 125- by 4-mm (3 μm) column (GROM, Herrenberg, Germany), and ectoine was monitored by its absorbance at 210 nm by using a UV/VIS detector (SYKAM, Gilching, Germany). The solvent employed for compatible solute separation was 80% (vol/vol) ACN. Chromatography was carried out isocratically at a flow rate of 1 ml/min and at 20°C. This procedure was developed by E. A. Galinski and coworkers (University of Münster, Münster, Germany) and was kindly provided prior to publication. The retention times of ectoine and hydroxyectoine were determined by using commercially available ectoine and hydroxyectoine samples.

To quantitate the glutamate content of B. cereus, the solute pool was extracted as described above and nitrogen-containing solutes were modified with 9-fluorenylmethyl chloroformate (FMOC). Subsequently the fluorescence-labeled amino acids were analyzed by HPLC using a Supersphere 60 RP-8 125- by 4-mm (4 μm) column (GROM) and a fluorescence detector (SYKAM, Gilching, Germany) at an excitation wavelength of 254 nm and an emission wavelength of 315 nm (33).

Transport assays.

Uptake of radiolabeled [1-14C]glycine betaine (55 mCi/mmol) by B. pasteurii was measured as described by Kempf and Bremer (31), except that the cells were maintained at 37°C during the transport assay. The cells were grown in SMM (with 2% urea) or SMM (with 2% urea) with 0.4 M NaCl to an OD578 of approximately 0.2 and then were assayed for glycine betaine uptake at a final substrate concentration of 10 μM [1-14C]glycine betaine. To study the inhibition of the glycine betaine transport by unlabeled ectoine, the concentration of radiolabeled glycine betaine was kept at 10 μM and ectoine was added at various substrate concentrations (10 μM to 1 mM).

Computer analysis.

DNA and protein sequences were assembled and analyzed with the Lasergene program (DNASTAR, Ltd., London, United Kingdom) on an Apple Macintosh computer. Searches for homologies were performed at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) by using the BLAST programs (2). Protein sequences were aligned with the CLUSTAL algorithm provided with the Lasergene program.

A phylogenetic analyses of the Bacillus species and related taxa investigated in this study for compatible solute production was performed by using 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequences available from public data bases with the ARB software package (http://www.mikro.biologie.tu-muenchen.de/pub/ARB/documentation/arb.ps). The most closely related sequences to those of the strains characterized for their osmolyte production in this study were used together with a large number of outgroup sequences for constructing a similarity matrix and a tree derived from it. The similarity matrix was corrected for multiple base changes at single positions by the neighbor-joining method. To simplify the final tree presented, outgroup sequences, sequences from other Bacillus species, and redundant sequences have been omitted.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the B. pasteurii ectABC genes and the flanking sequences have been deposited in GenBank and have been assigned the accession number AF316874.

RESULTS

De novo synthesis of ectoine in Bacillus spp.

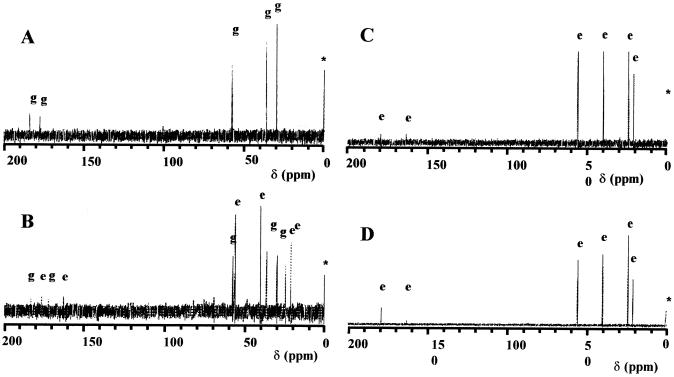

Natural-abundance 13C-NMR spectroscopy has been widely used to detect the dominant organic osmolytes produced by microorganisms under hyperosmotic growth conditions (29, 39, 50, 53). We used this technique to evaluate the spectrum of compatible solutes synthesized de novo in osmotically stressed cultures of B. licheniformis, B. megaterium, B. cereus, B. circulans, B. thuringensis, B. alcalophilus, Sporosarcina psychrophila (formerly Bacillus psychrophilus), B. pasteurii, Salibacillus (formerly Bacillus) salexigens, A. aneurinilyticus (DSM 5562T), P. polymyxa (DSM 36T), and Virgibacillus (formerly Bacillus) pantothenticus. For these experiments, the various Bacillus spp. were grown in defined minimal media lacking components of rich media (e.g., yeast extract and peptone), thereby avoiding the accumulation of preformed osmoprotectants (e.g., glycine betaine) from exogenous sources (17). A representative set of 13C-NMR spectra is shown in Fig. 1 for whole-cell extracts prepared from B. pasteurii cultures propagated in SMM (with 2% urea) alone or with 0.5, 1, or 1.5 M NaCl, respectively.

FIG. 1.

13C-NMR spectra of ethanolic cell extracts. A B. pasteurii strain (DSM 33T) was grown in SMM (2% urea) (A), in SMM (2% urea) with 0.5 M NaCl (B), in SMM (2% urea) with 1.0 M NaCl (C), or in SMM (2% urea) with 1.5 M NaCl (D). Resonances originating from glutamate (g), ectoine (e), and the standard [D4-3-(trimethylsilyl)propionate] (∗) are indicated. Chemical shifts [given in parts per million relative to the standard D4-3-(trimethylsilyl)propionate] for glutamate are 27.9, 34.6, 55.8, 175.3, and 184.1 and for ectoine are 19.6, 23.5, 38.3, 54.4, 161.9, and 177.8, respectively.

In each of the osmotically nonstressed cultures we detected primarily resonances corresponding to glutamate (Fig. 1A), fully consistent with previous reports that this amino acid constitutes the dominant amino acid in the cytoplasmic solute pools of B. subtilis (53) and B. licheniformis (14). As the osmolality of the growth medium was raised with NaCl, resonance of proline, ectoine, or hydroxyectoine was detected in most of the investigated Bacillus species and those of glutamate were suppressed (Fig. 1). Among the 13 species investigated we detected five patterns of endogenously synthesized compatible solutes: (i) strains that produced only glutamate, (ii) strains that produced proline, (iii) strains that produced ectoine, (iv) a strain that synthesized both ectoine and hydroxyectoine, and (v) a strain that produced both proline and ectoine (Table 1). Five of the thirteen investigated species were ectoine producers, suggesting that the ability to synthesize this particular compatible solute under hyperosmotic circumstances is widespread in the genus Bacillus and in closely related taxa.

TABLE 1.

Endogenously synthesized organic osmolytes of different Bacillus species and related genera analyzed by 13C-NMR spectroscopy

| Strain | Medium (M NaCl) | Osmolyte production

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ectoine | Proline | Glutamate | Hydroxyectoine | ||

| B. subtilis (JH642) | SMM (1) | − | + | + | − |

| B. licheniformis (DSM 13T) | SMM (1) | − | + | + | − |

| B. megaterium (DSM 32T) | SMM (1) | − | + | + | − |

| B. cereus (DSM 31T) | SMM (0.5) | − | − | + | − |

| B. circulans (DSM 9T) | SMM (0.5) | − | − | + | − |

| B. thuringiensis (DSM 2046T) | SMM (0.5) | − | − | + | − |

| A. aneurinilyticus (DSM 5562T) | SMM (0.5) | − | − | + | − |

| P. polymyxa (DSM 36T) | SMM (0.5) | − | − | + | − |

| B. alkalophilus (DSM 485T) | SMM (1) | + | − | + | − |

| B. psychrophilus (DSM 3T) | SMM (1) | + | − | + | − |

| B. pasteurii (DSM 33T) | SMM (1) | + | − | + | − |

| S. salexigens (DSM 11438T) | MM (3.4)a | + | − | + | + |

| V. pantothenticus (DSM 26T) | SMM (1) | + | + | + | − |

MM, mineral-salt-based medium.

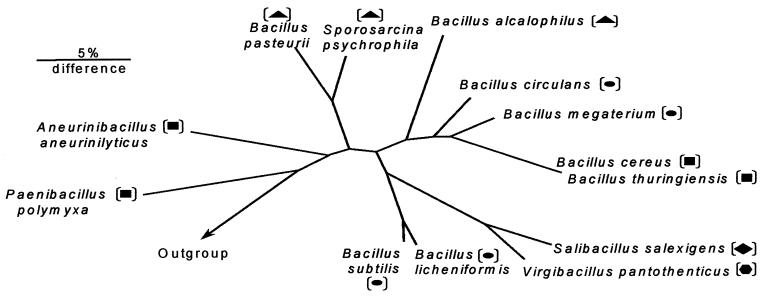

We established a 16S rRNA-based phylogenetic tree of the 13 bacterial species investigated for compatible solute production (Fig. 2). Inspection of this phylogenetic tree, and considering the data presented in Table 1, it is apparent that in general taxonomically closely related species also produce the same compatible solute. But this is not always the case. S. salexigens and V. pantothenticus are evolutionarily closely related (Fig. 2), and both produce ectoine when they are osmotically challenged (Table 1). However, S. salexigens is capable of hydroxyectoine production, whereas that is not the case with V. pantothenticus. The latter species, however, can synthesize proline in addition to ectoine.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree derived from the analysis of the 16S rRNA sequences of the Bacillus species and related taxa investigated for compatible solute production in this study. The bar represents a 5% sequence difference. The outgroup (not shown) consisted of a collection of more than 100 16S rRNA full sequences. Glutamate-producing bacteria are marked by squares, proline-synthesizing bacteria are marked by circles, ectoine-producing species are marked by triangles, the bacterial strain able to synthesize ectoine and proline is marked by a hexagon, and the bacterial strain which synthesizes ectoine and hydroxyectoine is marked by a diamond.

Finely tuned and osmotically controlled ectoine biosynthesis in B. pasteurii.

To analyze the osmoregulatory ectoine production in greater detail, we chose B. pasteurii as a representative of ectoine-synthesizing Bacillus spp. This species has recently been reclassified, and the name Sporosarcina pasteurii has been suggested (55). To determine whether the ectoine synthesis was an osmotic rather than a salt-stress-specific adaptation reaction, we grew B. pasteurii in a defined minimal medium whose osmolality had been raised with equiosmolar concentrations of ionic (NaCl, KCl) or nonionic (sucrose, lactose, glycerol) osmolytes. The ectoine content of the cells was then quantitated via HPLC analysis. Both ionic compounds (NaCl, KCl) and nonionic osmolytes (sucrose, lactose) strongly raised the ectoine level (Table 2). Glycerol, which is freely permeable across the cytoplasmic membrane at high concentrations and thus cannot establish an osmotic effective gradient, did not trigger ectoine production (Table 2); hence, ectoine synthesis in B. pasteurii is a true osmotic effect. The presence of the potent osmoprotectant glycine betaine in high-osmolality growth media completely prevented the osmoregulatory de novo synthesis of ectoine (Table 2). This observation indicates that the uptake of a preformed osmoprotectant was preferred over the endogenous synthesis of a compatible solute at least for the growth conditions tested in our experiments.

TABLE 2.

Osmotically induced ectoine biosynthesis in B. pasteurii (DSM 33T)

| Mediuma | Ectoine (mmol per g [dry weight])b |

|---|---|

| SMM (680 mosmol per kg of water) | NDc |

| SMM with 0.4 M NaCl (1,400 mosmol per kg of water) | 0.40 ± 0.020 |

| SMM with 0.4 M KCl (1,400 mosmol per kg of water) | 0.59 ± 0.034 |

| SMM with 0.68 M sucrose (1,400 mosmol per kg of water) | 0.59 ± 0.070 |

| SMM with 0.68 M lactose (1,400 mosmol per kg of water) | 0.36 ± 0.067 |

| SMM with 1.1 M glycerol (1,400 mosmol per kg of water) | ND |

| SMM with 0.4 M NaCl + 1 mM glycine betaine (1,400 mosmol per kg of water) | ND |

| SMM with 0.68 M sucrose + 1 mM glycine betaine (1,400 mosmol per kg of water) | ND |

Cultures of B. pasteurii (DSM 33T) were grown in SMM (2% urea) with the indicated ionic and nonionic osmolytes. Ectoine was extracted from the freeze-dried cell pellet and was measured by HPLC analysis.

The data shown are means of two independently grown cultures, and for each of these cultures the ectoine content was determined twice.

ND, no ectoine was detectable.

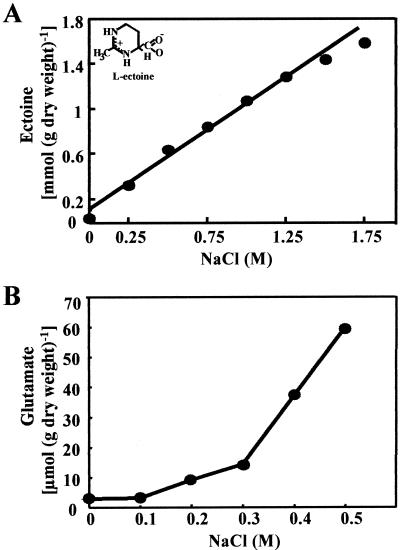

To analyze the correlation between the osmolality of the growth medium and the level of ectoine production, we grew B. pasteurii in minimal media of different salinities and then quantitated the produced ectoine by HPLC analysis when the cultures had reached approximately the same optical densities (OD578 = 1). We found an essentially linear relationship between ectoine content of the cells and the salinity of the medium over a wide range of osmotic growth conditions (Fig. 3A). In contrast, a nonlinear relationship was found between glutamate accumulation and salinity in B. cereus (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

(A) Osmotic control of ectoine synthesis in B. pasteurii. Cultures of B. pasteurii (DSM 33T) were grown in SMM (2% urea) with the indicated concentrations of NaCl to an OD578 of approximately 1, and the produced ectoine was quantitated by HPLC analysis. (B) Osmotic control of glutamate synthesis in B. cereus. Cultures of B. cereus (DSM 31T) were grown in SMM with the indicated concentrations of NaCl to an OD578 of approximately 1, and the produced glutamate was quantitated by HPLC analysis.

Cloning of the ectoine biosynthetic genes from B. pasteurii.

To investigate the ectoine biosynthetic genes from B. pasteurii at the molecular level we cloned and sequenced these genes. Initially, we recovered a 1.4-kb DNA fragment from B. pasteurii that carried part of the ectB and ectC genes (pSPICE1) by a PCR-based approach, with degenerate primers deduced from the ect biosynthetic genes of H. elongata (22) and M. halophilus (37). We then used the genomic DNA fragment from pSPICE1 as a hybridization probe to discern chromosomal restriction fragments of appropriate length that should encode the entire ect gene cluster of B. pasteurii. In this way we identified a 3.5-kb EcoRI restriction fragment that hybridized strongly to the "ectB-ectC" DNA probe. A DNA library of genomic EcoRI restriction fragments in a size range of 3 to 4 kb was then prepared in the low-copy-number cloning vector pHSG575 (49), and plasmids that hybridized to the chromosomal insert of pSPICE1 were identified. One of these plasmids, pSPICE2, contained the 3.5-kb EcoRI genomic restriction fragment from B. pasteurii expected from the Southern hybridization experiments. Subsequent DNA analysis showed that the chromosomal 3.5-kb EcoRI fragment carried all of the ectoine biosynthetic genes (ectABC) plus 415- and 682-bp flanking genomic regions.

Transformation of pSPICE2 into the E. coli strain MC4100 or the integration of the ectABC genes into the amyE locus of the B. subtilis strain JH642 did not result in ectoine production (as judged from HPLC analysis) either in nonstressed or osmotically stressed cultures (data not shown). The same observation was made by Cánovas et al. (11) when the ectoine biosynthetic genes of H. elongata DSM 3043 (Chromohalobacter salexigens) were introduced in E. coli, whereas the corresponding genes from M. halophilus could be functionally expressed in E. coli, resulting in the osmoregulated production of ectoine (37).

To prove that the ectABC genes from B. pasteurii were sufficient for ectoine production, we positioned these genes under the control of the IPTG-inducible phage T5 PN25 promoter and then recombined the ect genes in a single copy into the chromosome of the B. subtilis strain KE30, yielding strain AKB4. Cultures of strain AKB4 were grown in LB medium in the presence (1 mM) or absence of IPTG, and cellular extracts of these cultures were then investigated for ectoine production by HPLC analysis. The culture of strain AKB4 grown in the absence of IPTG did not produce any measurable amounts of ectoine, whereas the IPTG-mediated induction of expression of the T5 PN25 promoter ectABC construct in AKB4 resulted in the synthesis of 16 ± 1.85 μmol of ectoine per g (dry weight). Hence, the cloned ectABC region from B. pasteurii is sufficient to endow the non-ectoine producer B. subtilis with the ability to synthesize the tetrahydropyrimidine ectoine. However, the amounts of ectoine produced under the control of the IPTG-inducible phage T5 PN25 promoter were rather small in comparison to the amounts of ectoine synthesized in osmotically challenged B. pasteurii cultures (Fig. 3A). A possible explanation for this phenomenon could be that not enough precursor, l-aspartate-β-semialdehyde, for ectoine biosynthesis is present in the non-ectoine producer B. subtilis.

DNA sequence analysis of the ectABC gene cluster.

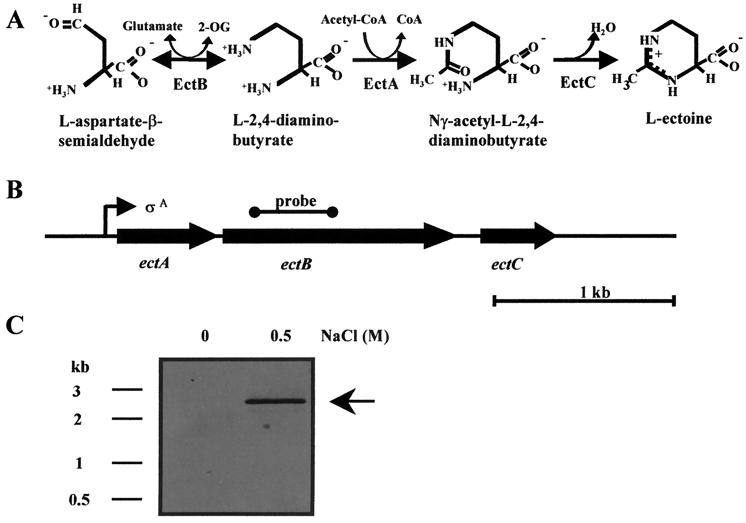

The DNA sequence of the entire chromosomal insert (3,537 bp) of pSPICE2 was determined. Analysis of this region with the DNASTAR program revealed the presence of three open reading frames that are oriented in the same direction (Fig. 4B). These open reading frames encode proteins with predicted molecular masses of 20.1 kDa (182 amino acids; EctA), 47.1 kDa (427 amino acids; EctB), and 14.9 kDa (135 amino acids; EctC). Each of these open reading frames is preceded by a potential ribosome-binding site that shows homology to typical ribosome-binding sites from B. subtilis. Visual inspection of the DNA sequence downstream of the translation termination codon of ectC did not reveal the presence of a factor-independent transcription termination signal with its typical inverted repeat structure and run of consecutive T residues. Below we refer to these open reading frames as ectABC (Fig. 4B) and to the encoded proteins as EctABC.

FIG. 4.

Ectoine biosynthetic pathway and Northern blot analysis of the B. pasteurii ectABC region. (A) Ectoine biosynthetic pathway from the precursor l-aspartate-β-semialdehyde. (B) Genetic organization of the ectABC genes in B. pasteurii and position of the RNA probe used for the transcriptional analysis of the ectABC gene cluster. (C) Northern blot analysis of the ectABC operon. Total RNA was isolated from B. pasteurii strain DSM 33T grown in SMM (2% urea) with or without 0.5 M NaCl and hybridized to an ectB-specific RNA probe.

Database searches using the BLAST network service (2) revealed a significant degree of sequence identity of the B. pasteurii EctABC proteins to enzymes known to be involved in ectoine biosynthesis in the moderate halophilic bacteria M. halophilus (DSM 20408T) (37), H. elongata (DSM 2581T) (22), and C. salexigens (formerly H. elongata DSM 3043) (3, 11) (Table 3). These database searches also revealed ectABC gene clusters in the finished genomes of B. halodurans (48) and Vibrio cholerae (25) and in the incomplete genome sequence of Streptomyces coelicolor (accession number AL591322) (Table 3). In general, the Ect proteins of B. pasteurii had a somewhat greater sequence identity to those of the gram-positive bacteria M. halophilus, B. halodurans, and S. coelicolor than to those from the gram-negative bacteria H. elongata, C. salexigens, and V. cholerae (Table 3). The substantial degree of sequence identity (up to 64%) among the ectoine biosynthetic enzymes and the preservation of the ectABC gene organization in all five microorganisms strongly suggests that the entire ectoine biosynthetic pathway is evolutionarily well conserved within the gram-positive and gram-negative branches of the bacterial world (Fig. 4A).

TABLE 3.

Sequence identities between the Ect proteins from B. pasteurii and M. halophilus, H. elongata, B. halodurans, V. cholerae, and S. coelicolor

| Protein | Sequence identities (%)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. pasteurii (DSM 33T) | M. halophilus (DSM 20408T) | H. elongata (DSM 2581T) | C. salexigens (DSM 3043T) | B. halodurans | V. cholerae | S. coelicolor | |

| EctA | 100 | 40.1 | 26.5 | 28.7 | 36.5 | 29.5 | 28.8 |

| EctB | 100 | 58.5 | 49.9 | 48.5 | 62.9 | 48.4 | 52.5 |

| EctC | 100 | 58.9 | 48.5 | 50.0 | 64.3 | 55.6 | 48.5 |

Tracer studies, NMR spectroscopy, and enzymatic analysis have revealed both the identity of the precursor for ectoine production and the enzymatic steps involved in the formation of this compatible solute (40, 42). The ectB gene mediates the first step in ectoine biosynthesis (Fig. 4A) and encodes an l-2,4-diaminobutyric acid transaminase that transfers the amino group of l-glutamate to the terminal oxo group of the precursor l-aspartate-β-semialdehyde, thereby forming l-2,4-diaminobutyric acid. Enzymological studies with the purified EctB protein from H. elongata have shown that this protein requires pyridoxal 5"-phosphate and potassium ions for its activity and stability and exists as a homohexamer in solution (40). The EctA enzyme catalyses the second step in the ectoine biosynthetic pathway through the acetylation of l-2,4-diaminobutyric acid to Nγ-acetyl-l-2,4-diaminobutyrate at the expense of acetyl-coenzyme A. Ring closure of this intermediate is then mediated by the ectC-encoded ectoine synthase (Fig. 4A).

Transcriptional analysis of the ectABC operon.

An intergenic region of 49 bp separates the B. pasteurii ectA and ectB genes, and ectB is separated from ectC by 158 bp. The tight spacing of these genes suggested that the ectABC gene cluster might be transcribed as an operon. We used Northern analysis to investigate the transcriptional organization of the ectABC genes in B. pasteurii. Total RNA was prepared from B. pasteurii cultures grown in SMM (with 2% urea) or under osmotic stress conditions (SMM containing 2% urea and 0.5 M NaCl). The RNA was then separated according to size on an agarose gel, transferred to a nylon membrane, and hybridized to a DIG-labeled RNA probe derived from the ectB gene (Fig. 4B). A single transcript of 2.6 kb was detected (Fig. 4C); its size closely matches that calculated for the distance (2,440 bp) between the start codon for ectA and the termination codon for ectC. Hence, the ectABC gene cluster of B. pasteurii is transcribed as an operon. Expression of the ectABC operon occurs in an osmotically regulated fashion: we detected no ect transcript in B. pasteurii cultures that were grown in SMM (with 2% urea), but there was a strong increase in the ect mRNA level in the cells subjected to osmotic stress (Fig. 4C).

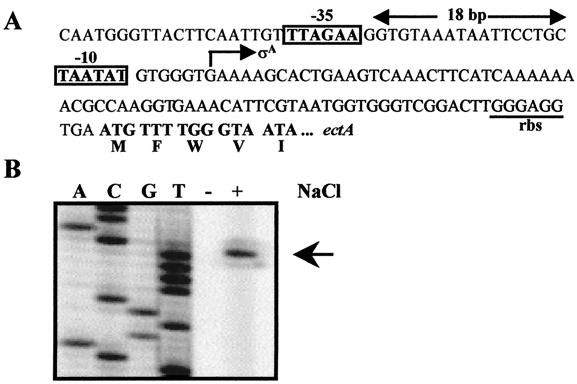

To pinpoint the promoter for the ectABC operon, we performed a primer extension analysis. Total RNA was isolated from B. pasteurii cultures grown in SMM (with 2% urea) and SMM (with 2% urea) containing 1.5 M NaCl. The isolated total RNA was then hybridized with an ectA-specific primer labeled at its 5" end with the infrared dye IRD-800, and the hybridization product was extended with reverse transcriptase. Subsequent analysis of the primer extension product on an LI-COR DNA sequencer revealed a single ect-specific mRNA species whose production was under osmotic control (Fig. 5B). Its 5" end is located 78 bp upstream of the ATG start codon of ectA (Fig. 5A). Inspection of the DNA sequence upstream of the mRNA initiation site revealed the presence of putative −10 and −35 promoter sequences that resemble the consensus sequences of promoters recognized by the main vegetative sigma factor (σA) of B. subtilis. This promoter has a spacing of 18 bp, and a TG motif is found at position −16 (Fig. 5A). Such a TG motif is present in many B. subtilis promoter sequences and is an important element for effective initiation of transcription (26).

FIG. 5.

Mapping of the B. pasteurii ectABC transcription start site. (A) Nucleotide sequence of the ectABC promoter region. The −10 and −35 regions of the ect promoter are indicated, and the transcriptional start site and the putative ribosome-binding site (rbs) are marked. (B) Primer extension analysis of the ect-specific transcript. Total RNA was prepared from cells of the B. pasteurii strain DSM 33T grown in SMM (2% urea) with (+) or without (−) 1.5 M NaCl, and the transcription initiation site of the ectABC locus was identified by primer extension analysis using an ectA-specific primer labeled with the infrared dye IRD-800. The reaction products were analyzed on an automatic DNA sequencer, and the same primer was used for sequencing reactions to size the ect transcript.

Osmoprotection and uptake of compatible solutes by B. pasteurii.

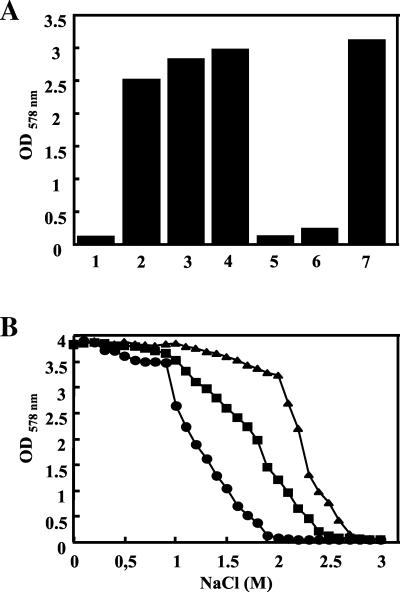

B. subtilis possesses a set of five transporters, the Opu systems, that allows the osmoregulated uptake of a wide range of preformed osmoprotectants and of choline, which serves as the precursor for the synthesis of glycine betaine (8, 32). We tested whether B. pasteurii could also use exogenously provided compatible solutes for osmoprotection. For these experiments we grew B. pasteurii under high-osmolality conditions that strongly impaired its growth and provided these cultures with low concentrations (1 mM) of ectoine, hydroxyectoine, glycine betaine, carnitine, proline, or choline. With the notable exceptions of choline and proline, each of these compounds exerted a strong osmoprotective effect for B. pasteurii (Fig. 6A), demonstrating that this Bacillus species can rely on the acquisition of preformed compatible solutes in addition to its endogenous synthesis of ectoine for osmoprotective purposes. B. subtilis possesses a high-affinity and osmoregulated transport system, OpuE, for the uptake of proline under hypertonic growth conditions (52), but this is apparently not present in B. pasteurii, which is not protected by proline (Fig. 6A). Likewise, B. pasteurii does not possess the osmoregulatory choline-to-glycine betaine synthesis pathway that permits B. subtilis to take up and oxidize choline to glycine betaine for effective osmoprotection (5, 30).

FIG. 6.

Osmoprotection of B. pasteurii by compatible solutes. B. pasteurii (DSM 33T) was grown in high-osmolality minimal medium (SMM with 2% urea and 2 M NaCl) with or without an osmoprotectant (final concentration, 1 mM). The cells were inoculated to an OD578 of 0.1 from an overnight culture grown in SMM (with 2% urea) and were grown in 20 ml of medium in 100-ml Erlenmeyer flasks on an orbital shaker (220 rpm) at 37°C. The growth yield of each culture was determined spectrophometrically by measuring the OD578 after 16 h of incubation. 1, no osmoprotectant added; 2, addition of dl-carnitine; 3, addition of ectoine; 4, addition of hydroxyectoine; 5, addition of choline; 6, addition of proline; 7, addition of glycine betaine. (B) Ectoine and glycine betaine protect B. pasteurii (DSM 33T) from the detrimental effects of high osmolality. Twenty-milliliter cultures (in 100-ml Erlenmeyer flasks) of SMM (2% urea) with different salinities were inoculated to an OD578 of 0.1 from an overnight culture grown in SMM (with 2% urea) and were grown for 16 h. SMM (2% urea) alone (•) or with 1 mM ectoine (▪) or 1 mM glycine betaine (▴) was used.

We compared the osmoprotective effects of exogenously provided ectoine and glycine betaine for the growth of B. pasteurii in high osmolality media in somewhat greater detail. Cultures of different osmolalities were inoculated with B. pasteurii either in the absence or in the presence of the osmoprotectants ectoine and glycine betaine (1 mM each) and were grown for 16 h; the optical densities of the cultures were then determined. When medium osmolarity was increased by more than 1 M NaCl, there was a decline in the growth yield of the cultures grown without an osmoprotectant (Fig. 6B). Adding ectoine or glycine betaine to the osmotically challenged cultures greatly improved the growth yield, and the growth yield was clearly higher with glycine betaine than with ectoine (Fig. 6B).

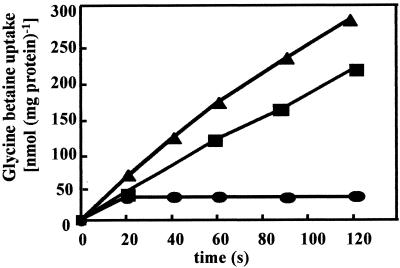

We also measured the uptake of radiolabeled glycine betaine at a final substrate concentration of 10 μM and found a strongly osmotically stimulated glycine betaine transport activity in B. pasteurii (Fig. 7). Microorganisms often possess multiple glycine betaine transport systems, and in some bacteria (e.g., E. coli, B. subtilis, Corynebacterium glutamicum, Sinorhizobium meliloti, and Erwinia chrysanthemi) such glycine betaine transporters also serve for ectoine uptake (23, 27, 28, 41, 50). The addition of a 100-fold excess of ectoine had only a small effect on the osmotically stimulated [1-14C]glycine betaine uptake activity (Fig. 7), indicating that in B. pasteurii the uptake systems for ectoine and glycine betaine are distinct.

FIG. 7.

Osmotically controlled uptake of glycine betaine by B. pasteurii. Glycine betaine transport in B. pasteurii (DSM 33T) was measured in cultures grown in SMM (2% urea) without NaCl (•) or with 0.4 M NaCl (▴; ▪). Glycine betaine uptake was measured at a final substrate concentration of 10 μM. In one of the cultures (▪) glycine betaine uptake was determined in the presence of 1 mM ectoine.

Ectoine and hydroxyectoine are metabolically inert in B. pasteurii.

We tested whether B. pasteurii degrades ectoine and hydroxyectoine for use as a sole carbon, nitrogen, or energy source. Ectoine and hydroxyectoine did not support the growth of B. pasteurii when supplied at a concentration of 30 mM as sole carbon and energy sources. Likewise, neither compound (provided as a concentration of 30 mM) served as a nitrogen source in a modified SMM (with 2% urea) medium in which (NH4)2SO4 had been replaced by K2SO4 at the equivalent concentration. Hence, neither ectoine nor hydroxyectoine is used by B. pasteurii for anabolic purposes.

DISCUSSION

Increases in the osmolality of the environment impose a considerable strain on the water balance of the cell and necessitate active countermeasures to prevent dehydration of the cytoplasm and the cessation of growth (8). The synthesis of compatible solutes within both Archaea (44) and Bacteria (16, 20) is an evolutionarily highly conserved trait that allows microorganisms to cope with hyperosmotic challenges. Although the number of Bacillus species and related genera that we have investigated for compatible solute synthesis in this study is not exhaustive (Table 1), our data clearly show that the ability to synthesize proline or ectoine under high-osmolality conditions is widely found within the genus Bacillus. Different patterns exist with respect to proline and ectoine synthesis, because these compounds can either be synthesized alone or in combination (Table 1). Of the 13 species we tested, 5 (B. cereus, B. circulans, B. thuringensis, A. aneurinilyticus, and P. polymyxa) do not synthesize proline or ectoine and instead produce glutamate as their dominant organic osmolyte. We found that in B. cereus a raise in the medium osmolarity triggers an increase in the glutamate level (Fig. 3B), indicating that glutamate serves as a compatible solute in this species. The five glutamate-accumulating Bacillus species are the most salt-sensitive species that we have studied (Table 1); this suggests that proline and ectoine synthesis is a more effective osmoadaptive measure than glutamate synthesis alone. Indeed, disruption of the osmoregulatory proline biosynthetic pathway in B. subtilis (J. Brill and E. Bremer, unpublished results) or of the ectoine biosynthetic genes in the moderate halophilic bacteria C. salexigens and H. elongata (12, 22) strongly impairs the ability of these microorganisms to cope effectively with hyperosmotic growth conditions.

Ectoine was originally discovered as a compatible solute in the extremely halophilic phototropic sulfurbacterium Ectothiorhodospira halochloris (19). It was initially viewed as a rather uncommon compatible solute, but improved screening procedures via HPLC and natural-abundance 13C-NMR spectroscopy subsequently revealed that it is found widely among a taxonomically and physiologically diverse set of species within the Bacteria (20). To date, there are no reports of its production by either Archaea or eukaryotes. Of the 13 bacterial species that we studied, 5 could synthesize ectoine in response to increases in medium osmolality (Table 1). Furthermore, Galinski and Trüper (20) reported that B. halophilus and two Bacillus species of unclear taxonomic position are capable of ectoine synthesis. Taken together, these data indicate that osmotically regulated ectoine production is a widespread trait within the genus Bacillus and closely related genera.

NMR analysis and enzymological studies have shown that ectoine is commonly produced from l-aspartate-β-semialdehyde, an intermediate in amino acid metabolism, in a three-step reaction with l-2,4-diaminobutyrate and Nγ-acetyl-l-2,4-diaminobutyrate as the intermediates (Fig. 4A) (40, 42). Enzymological studies (40) and the cloning of the ectoine biosynthetic genes (ectABC) from the gram-negative bacteria C. salexigens and H. elongata (11, 22) and the gram-positive bacterium M. halophilus (37) have demonstrated the involvement of three enzymes (EctABC) in the production of this compatible solute. DNA sequence analysis of the ectoine biosynthetic genes of B. pasteurii carried out by us revealed the presence of highly related ectABC genes in this genus as well, suggesting that all ectoine-producing Bacilli use the same pathway to synthesize ectoine under high-osmolality growth conditions. This pathway is evolutionarily well conserved with respect to both the enzymes involved (Table 3) and the genetic organization of the ectABC structural genes. Database searches suggest that corresponding pathways are also present in the haloalkalophile B. halodurans, the human pathogen V. cholerae, and the soil bacterium S. coelicolor (Table 3). Indeed, ectoine production has recently been directly demonstrated in B. halodurans and S. coelicolor by using 13C-NMR spectroscopy and HPLC analysis (N. Pica, A. Kuhlmann, and E. Bremer, unpublished results). Depending on the growth conditions and the growth phase, several ectoine producers also synthesize the compatible solute β-hydroxyectoine, which is apparently formed either by the direct hydroxylation of ectoine (51) or through an unknown pathway involving the intermediate N-β-acetyl-l-2,4-diaminobutyrate (Fig. 4A) (10). Inspection of the DNA sequence immediately downstream of the ectABC gene cluster in S. coelicolor revealed the presence of an open reading frame whose gene product is presently annotated in the database as a hydroxylase (accession number AL591322). Indeed, S. coelicolor is capable of producing β-hydroxyectoine (A. Kuhlmann and E. Bremer, unpublished results). The open reading frame located downstream of the ectABC gene cluster in S. coelicolor is therefore an interesting candidate for the still-elusive ectoine hydroxylase. Among the ectoine-synthesizing species we analyzed, only S. salexigens was able to produce β-hydroxyectoine (Table 1).

Ectoine synthesis in B. pasteurii is a true osmotic effect rather than a salt-specific response, since both ionic and nonionic osmolytes trigger the production of ectoine (Table 2). The amount of ectoine synthesized by the cells is directly correlated with the osmolality of the growth medium (Fig. 3A), suggesting that B. pasteurii sensitively adjusts the intracellular ectoine pool to the degree of the imposed osmotic stress. Northern blot analysis of the ectABC gene cluster revealed that these genes are expressed as an operon and are transcribed in an osmotically controlled fashion (Fig. 4B). Fully consistent with this observation is our finding that ectoine is only produced in significant amounts at elevated osmolalities (Fig. 3A, Table 2). Consequently, ectoine synthesis in B. pasteurii must depend primarily on the stimulation of gene transcription under hypertonic conditions, but there might be an additional posttranscriptional level of control since the activity of some of the ectoine biosynthetic enzymes from H. elongata are stimulated in vitro by high salt (40). Primer extension analysis allowed us to identify the B. pasteurii ectABC promoter. Its sequence resembles that of typical sigma A-dependent promoters from B. subtilis (26), but its in vivo activity is tightly coupled to the osmolality of the growth medium (Fig. 5). It is well established for various organisms that ectoine production is responsive to increases in medium osmolality, but to the best of our knowledge the data presented here for B. pasteurii (Fig. 4C and 5) demonstrate for the first time an osmotically controlled transcription for an ectABC gene cluster. We therefore conclude that the osmotically controlled de novo synthesis of ectoine is an important facet in the cellular adaptation reaction of B. pasteurii to high-osmolality surroundings.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. A. Galinski for his kind advice on the HPLC analysis of ectoine and M. Marahiel for providing bacterial strains and plasmids. We greatly appreciate the help of D. R. Arahal for the construction of the phylogenetic tree shown in Fig. 2. We thank V. Koogle for help in editing the manuscript.

Financial support for this study was provided by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through SFB-395, the Graduiertenkollegs “Enzymchemie” and “Proteinfunktion auf atomarer Ebene,” the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie, and the European Community (contract IAC4-2000-30041).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ajouz, B., C. Berrier, A. Garrigues, M. Besnard, and A. Ghazi. 1998. Release of thioredoxin via the mechanosensitive channel MscL during osmotic downshock of Escherichia coli cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273:26670-26674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arahal, D. R., M. T. Garcia, C. Vargas, D. Canovas, J. J. Nieto, and A. Ventosa. 2001. Chromohalobacter salexigens sp. nov., a moderately halophilic species that includes Halomonas elongata DSM 3043 and ATCC 33174. Int. J. Syst. E vol. Microbiol. 51:1457-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arakawa, T., and S. N. Timasheff. 1985. The stabilization of proteins by osmolytes. Biochem. J. 47:411-414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boch, J., B. Kempf, R. Schmid, and E. Bremer. 1996. Synthesis of the osmoprotectant glycine betaine in Bacillus subtilis: characterization of the gbsAB genes. J. Bacteriol. 178:5121-5129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Booth, I. R., and P. Louis. 1999. Managing hypoosmotic stress: aquaporins and mechanosensitive channels in Escherichia coli. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:166-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourot, S., O. Sire, A. Trautwetter, T. Touze, L. F. Wu, C. Blanco, and T. Bernard. 2000. Glycine betaine-assisted protein folding in a lysA mutant of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 275:1050-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bremer, E., and R. Krämer. 2000. Coping with osmotic challenges: osmoregulation through accumulation and release of compatible solutes in bacteria, p. 79-97. In G. Storz and R. Hengge-Aronis (ed.), Bacterial stress responses. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 9.Brown, A. D. 1976. Microbial water stress. Bacteriol. Rev. 40:803-846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cánovas, D., N. Borges, C. Vargas, A. Ventosa, J. J. Nieto, and H. Santos. 1999. Role of N-γ-acetyldiaminobutyrate as an enzyme stabilizer and an intermediate in the biosynthesis of hydroxyectoine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3774-3779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cánovas, D., C. Vargas, M. I. Calderon, A. Ventosa, and J. J. Nieto. 1998. Characterization of the genes for the biosynthesis of the compatible solute ectoine in the moderately halophilic bacterium Halomonas elongata DSM 3043. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 21:487-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cánovas, D., C. Vargas, F. Iglesias-Guerra, L. N. Csonka, D. Rhodes, A. Ventosa, and J. J. Nieto. 1997. Isolation and characterization of salt-sensitive mutants of the moderate halophile Halomonas elongata and cloning of the ectoine synthesis genes. J. Biol. Chem. 272:25794-25801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casadaban, M. J. 1976. Transposition and fusion of the lac genes to selected promoters in Escherichia coli using bacteriophage Lambda and Mu. J. Mol. Biol. 104:541-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark, V. L., D. E. Peterson, and R. W. Bernlohr. 1972. Changes in free amino acid production and intracellular amino acid pools of Bacillus licheniformis as a function of culture age and growth media. J. Bacteriol. 112:715-725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Csonka, L. N. 1989. Physiological and genetic responses of bacteria to osmotic stress. Microbiol. Rev. 53:121-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Csonka, L. N., and W. Epstein. 1996. Osmoregulation, p. 1210-1223. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, vol. 1. ASM Press, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dulaney, E. L., D. D. Dulaney, and E. L. Rickes. 1968. Factors in yeast extract which relieve growth inhibition of bacteria in defined medium of high osmolarity. Dev. Ind. Microbiol. 9:260-269. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eppelmann, K., S. Doekel, and M. A. Marahiel. 2001. Engineered biosynthesis of the peptide antibiotic bacitracin in the surrogate host Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 276:34824-34831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galinski, E. A., H. P. Pfeiffer, and H. G. Trüper. 1985. 1,4,5,6-Tetrahydro-2-methyl-4-pyrimidinecarboxylic acid. A novel cyclic amino acid from halophilic phototrophic bacteria of the genus Ectothiorhodospira. Eur. J. Biochem. 149:135-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galinski, E. A., and H. G. Trüper. 1994. Microbial behaviour in salt-stressed ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 15:95-108. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garabito, M. J., D. R. Arahal, E. Mellado, M. C. Marquez, and A. Ventosa. 1997. Bacillus salexigens sp. nov., a new moderately halophilic Bacillus species. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:735-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Göller, K., A. Ofer, and E. A. Galinski. 1998. Construction and characterization of an NaCl-sensitive mutant of Halomonas elongata impaired in ectoine biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 161:293-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gouesbet, G., A. Trautwetter, S. Bonnassie, L. F. Wu, and C. Blanco. 1996. Characterization of the Erwinia chrysanthemi osmoprotectant transporter gene ousA. J. Bacteriol. 178:447-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harwood, C. R., and A. R. Archibald. 1990. Growth, maintenance and general techniques, p. 1-26. In C. R. Harwood and S. M. Cutting (ed.), Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Chichester, United Kingdom.

- 25.Heidelberg, J. F., J. A. Eisen, W. C. Nelson, R. A. Clayton, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, L. Umayam, S. R. Gill, K. E. Nelson, T. D. Read, H. Tettelin, D. Richardson, M. D. Ermolaeva, J. Vamathevan, S. Bass, H. Qin, I. Dragoi, P. Sellers, L. McDonald, T. Utterback, R. D. Fleishmann, W. C. Nierman, and O. White. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helmann, J. D. 1995. Compilation and analysis of Bacillus subtilis sA-dependent promoter sequences: evidence for extended contact between RNA polymerase and upstream promoter DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:2351-2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jebbar, M., R. Talibart, K. Gloux, T. Bernard, and C. Blanco. 1992. Osmoprotection of Escherichia coli by ectoine: uptake and accumulation characteristics. J. Bacteriol. 174:5027-5035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jebbar, M., C. von Blohn, and E. Bremer. 1997. Ectoine functions as an osmoprotectant in Bacillus subtilis and is accumulated via the ABC-transport system OpuC. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 154:325-330. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kappes, R., and E. Bremer. 1998. Response of Bacillus subtilis to high osmolarity: uptake of carnitine, crotonobetaine and γ-butyrobetaine via the ABC transport system OpuC. Microbiology 144:83-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kappes, R. M., B. Kempf, S. Kneip, J. Boch, J. Gade, J. Meier-Wagner, and E. Bremer. 1999. Two evolutionarily closely related ABC-transporters mediate the uptake of choline for synthesis of the osmoprotectant glycine betaine in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 32:203-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kempf, B., and E. Bremer. 1995. OpuA, an osmotically regulated binding protein-dependent transport system for the osmoprotectant glycine betaine in Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 270:16701-16713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kempf, B., and E. Bremer. 1998. Uptake and synthesis of compatible solutes as microbial stress responses to high osmolality environments. Arch. Microbiol. 170:319-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kunte, J., E. A. Galinski, and H. G. Trüper. 1993. A modified FMOC-method for the detection of amino acid-type osmolytes and tetrahydropyrimidines (ectoines). J. Microbiol. Methods 17:129-136. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levina, N., S. Totemeyer, N. R. Stokes, P. Louis, M. A. Jones, and I. R. Booth. 1999. Protection of Escherichia coli cells against extreme turgor by activation of MscS and MscL mechanosensitive channels: identification of genes required for MscS activity. EMBO J. 18:1730-1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin, Y., and J. N. Hansen. 1995. Characterization of a chimeric proU operon in a subtilin-producing mutant of Bacillus subtilis 168. J. Bacteriol. 177:6874-6880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lippert, K., and A. A. Galinski. 1992. Enzyme stabilization by ectoine-type compatible solutes: protection against heating, freezing and drying. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 37:61-65. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Louis, P., and E. A. Galinski. 1997. Characterization of genes for the biosynthesis of the compatible solute ectoine from Marinococcus halophilus and osmoregulated expression in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 143:1141-1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller, K. J., and J. M. Wood. 1996. Osmoadaptation by rhizosphere bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50:101-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nau-Wagner, G., J. Boch, J. A. Le Good, and E. Bremer. 1999. High-affinity transport of choline-O-sulfate and its use as a compatible solute in Bacillus subtilis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:560-568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ono, H., K. Sawada, N. Khunajakr, T. Tao, M. Yamamoto, M. Hiramoto, A. Shinmyo, M. Takano, and Y. Murooka. 1999. Characterization of biosynthetic enzymes for ectoine as a compatible solute in a moderately halophilic eubacterium. Halomonas elongata. J. Bacteriol. 181:91-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peter, H., B. Weil, A. Burkovski, R. Kramer, and S. Morbach. 1998. Corynebacterium glutamicum is equipped with four secondary carriers for compatible solutes: identification, sequencing, and characterization of the proline/ectoine uptake system, ProP, and the ectoine/proline/glycine betaine carrier, EctP. J. Bacteriol. 180:6005-6012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peters, P., E. A. Galinski, and H. G. Trüper. 1990. The biosynthesis of ectoine. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 71:157-162. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qu, Y., C. L. Bolen, and D. W. Bolen. 1998. Osmolyte-driven contraction of a random coil protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:9268-9273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roberts, M. F. 2000. Osmoadaptation and osmoregulation in archaea. Front. Biosci. 5:796-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. E. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 46.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. R. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spiegelhalter, F., and E. Bremer. 1998. Osmoregulation of the opuE proline transport gene from Bacillus subtilis-contributions of the σA- and σB-dependent stress-responsive promoters. Mol. Microbiol. 29:285-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takami, H., K. Nakasone, Y. Takaki, G. Maeno, R. Sasaki, N. Masui, F. Fuji, C. Hirama, Y. Nakamura, N. Ogasawara, S. Kuhara, and K. Horikoshi. 2000. Complete genome sequence of the alkaliphilic bacterium Bacillus halodurans and genomic sequence comparison with Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:4317-4331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takeshita, S., M. Sato, M. Toba, W. Masahashi, and T. Hashimoto-Gothoh. 1987. High-copy-number and low-copy-number plasmid vectors for lacZ α-complementation and chloramphenicol- or kanamycin-resistance selection. Gene 61:63-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Talibart, R., M. Jebbar, G. Gouesbet, S. Himdi-Kabbab, H. Wróblewski, C. Blanco, and T. Bernard. 1994. Osmoadaptation in rhizobia: ectoine-induced salt tolerance. J. Bacteriol. 176:5210-5217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ventosa, A., J. J. Nieto, and A. Oren. 1998. Biology of moderately halophilic aerobic bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:504-544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.von Blohn, C., B. Kempf, R. M. Kappes, and E. Bremer. 1997. Osmostress response in Bacillus subtilis: characterization of a proline uptake system (OpuE) regulated by high osmolarity and the alternative transcription factor sigma B. Mol. Microbiol. 25:175-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whatmore, A. M., J. A. Chudek, and R. H. Reed. 1990. The effects of osmotic upshock on the intracellular solute pools of Bacillus subtilis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136:2527-2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whatmore, A. M., and R. H. Reed. 1990. Determination of turgor pressure in Bacillus subtilis: a possible role for K+ in turgor regulation. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136:2521-2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoon, J. H., K. C. Lee, N. Weiss, Y. H. Kho, K. H. Kang, and Y. H. Park. 2001. Sporosarcina aquimarina sp. nov., a bacterium isolated from seawater in Korea, and transfer of Bacillus globisporus (Larkin and Stokes 1967). Bacillus psychrophilus (Nakamura 1984) and Bacillus pasteurii (Chester 1898) to the genus Sporosarcina as Sporosarcina globispora comb. nov., Sporosarcina psychrophila comb. nov. and Sporosarcina pasteurii comb. nov., and emended description of the genus Sporosarcina. Int. J. Syst. E vol. Microbiol. 51:1079-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]