Abstract

The deubiquitinating enzyme BAP1 is the catalytic subunit of the Polycomb Repressive Deubiquitinase (PR-DUB) complex, which acts with the Polycomb Repressive Complexes 1 and 2 to regulate chromatin organization to repress homeotic genes and other developmental regulators. Loss of BAP1 is implicated in several cancers, in the familial cancer syndrome BAP1 Tumor Predisposition Syndrome, and in the neurodevelopmental disorder Küry-Isidor syndrome. In Drosophila, there are numerous reports in the literature describing developmental patterning phenotypes for several chromatin regulators, including the discovery of Polycomb itself, but corresponding adult morphological phenotypes due to developmental dysregulation of the Drosophila BAP1 ortholog calypso (caly) are less well-described. We report here that knockdown of caly in the eye and wing produces concomitant chromatin dysregulation phenotypes. RNAi to caly in the early eye reduces survival and leads to changes in eye size and shape including eye outgrowths, some of which resemble homeotic transformations, whereas others resemble tumor-like outgrowths seen in other fly cancer models. Mosaic eyes containing caly loss-of-function tissue phenocopy caly RNAi. Knocking down caly across the wing disrupts wing shape and patterning, including effects on wing vein pattern. This phenotypic characterization reinforces the growing body of literature detailing developmental mis-patterning driven by chromatin dysregulation and serves as a baseline for future mechanistic studies to understand the role of BAP1 in development and disease.

Keywords: BAP1, calypso, polycomb repression, PR-DUB, Drosophila

Introduction

The deubiquitinating enzyme (DUB) BAP1, BRCA1-associated protein 1, is a major tumor driver and metastasis suppressor in uveal melanoma (UM), the most common primary cancer of the eye (Kashyap et al. 2016; Jager et al. 2020). BAP1 is mutated in 45% of UM and in 85% of UM that metastasize (Harbour et al. 2010; Robertson et al. 2017; Field et al. 2018). In addition, various other cancers have significant loss of BAP1, including mesothelioma (Bott et al. 2011; Testa et al. 2011; Wiesner et al. 2011), clear cell renal cancer (Ricketts et al. 2018), and cholangiocarcinoma (Jiao et al. 2013). Germline mutations in BAP1 also lead to a BAP1 Tumor Predisposition Syndrome (BAP1-TPS) (Bergman et al. 2006; Carbone et al. 2012, 2015). BAP1 is reported to regulate cell proliferation (Machida et al. 2009), cell death (Bononi et al. 2017), and nuclear processes crucial for genome stability, such as DNA repair and replication (Yu et al. 2014). The Polycomb repressive system is composed of 3 main protein complexes: Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 (PRC1), Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), and the Polycomb Repressive Deubiquitinase (PR-DUB) complex, in which BAP1 is the catalytic subunit (Scheuermann et al. 2010) and partners with additional sex combs-like (ASXL) protein (schematic in Fig. 1). These complexes repress homeotic (HOX) and other developmental regulator genes in cells where they must stay inactive, thereby ensuring proper differentiation and cellular identity throughout development (Scheuermann et al. 2010). Loss of essential components of these complexes can result in dysregulation of chromatin organization, which leads to developmental abnormalities and diseases such as cancer. Within the PR-DUB complex, BAP1 globally deubiquitinates lysine 119 on histone H2A (Fig. 1), and its loss leads to pervasive H2AK119ub1. Failure to constrain pervasive H2AK119ub1 titrates away Polycomb Repressive Complexes (PRC) from their targets, decreasing promoter H3K27me3 concentration and leading to chromatin compaction (Daou et al. 2015; Conway et al. 2021; Fursova et al. 2021). Despite these insights, the specific role of loss of BAP1 function in the development of different cancers and their metastases is unclear.

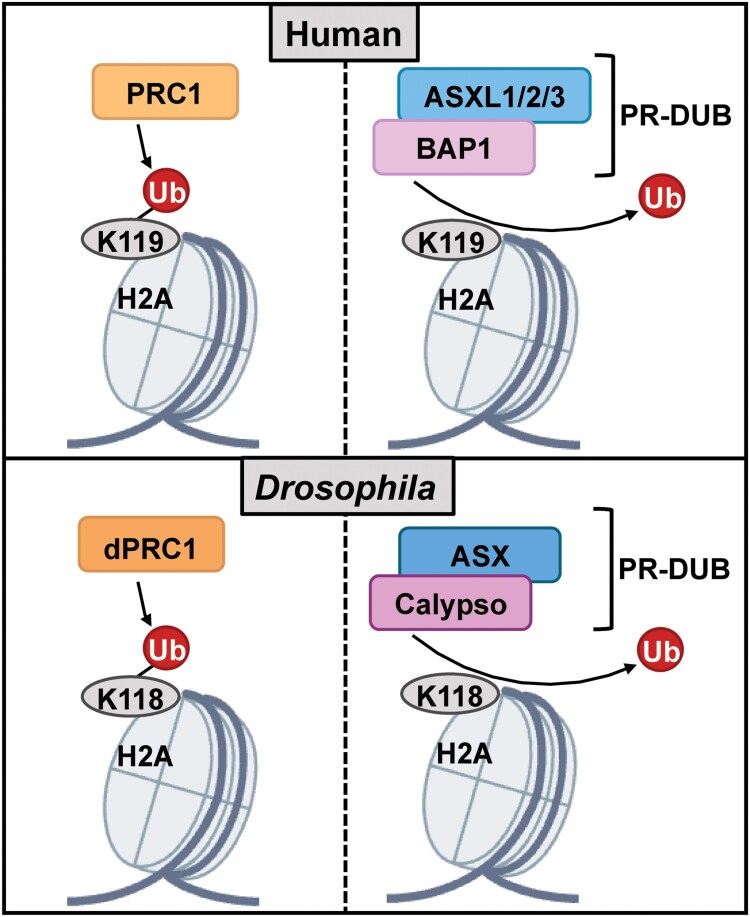

Fig. 1.

PR-DUB catalytic subunit caly/BAP1 promotes H2A deubiquitination within the polycomb repressive system. Schematic representation of PRC1-mediated monoubiquitination of histone H2A and subsequent removal by the Polycomb Repressive Deubiquitinase (PR-DUB) complex in humans (top panels) and Drosophila (bottom panels). In humans, Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 (PRC1) catalyzes monoubiquitination of H2A at lysine 119 (H2AK119Ub), whereas in Drosophila, its functional ortholog dPRC1 targets lysine 118 (H2AK118Ub). These marks are removed by the PR-DUB complex, which comprises BAP1 and ASXL1/2/3 in humans, and Calypso and ASX in Drosophila. While the depicted complexes for PR-DUB represent the core catalytic units, both mammalian and Drosophila PR-DUB complexes associate with additional cofactors that modulate complex assembly, chromatin targeting, and enzymatic activity. PRC1 is made up of a variety of different components, which are depicted here as one complex.

Model systems such as Drosophila provide a useful context to further study BAP1 function and its roles in vivo. In fact, polycomb itself was originally discovered in Drosophila (Lewis and Mislove 1947). PR-DUB subunits BAP1 and ASXL are highly conserved and represented in Drosophila by calypso (caly, also called dBap1) and Additional sex combs (Asx), respectively. Extensive literature in Drosophila describes the role of PRC1, PRC2, a number of Polycomb regulators, and the other PR-DUB subunit Asx, but less work has been done to characterize caly developmental phenotypes. Previous work in flies led to the isolation of caly mutant alleles that were based on the ability of mutant clones in the wing to phenocopy Polycomb Group (PcG) transformations (de Ayala Alonso et al. 2007). This showed that loss of caly catalytic activity increases monoubiquitinated H2A in vitro and decreases repression of PcG target genes and HOX genes in vivo in clones in the wing, as seen in human cell lines and murine models (Scheuermann et al. 2010). Substantial characterization of embryos and larval structures, including immunostaining analyses that revealed detailed patterns of dysregulating signaling components and homeotic regulators in larval clones homozygous for either Asx or caly mutant alleles, has revealed substantial mechanistic insights (Halachmi et al. 2007; Bischoff et al. 2009; Bonnet et al. 2022; Brown et al. 2023, 2025). In addition to these extensive characterizations of developmental structures, some eye and other epidermal morphological phenotypes in adults that resulted from these random mutant clones or caly RNAi have been mentioned in previous reports (Halachmi et al. 2007; Bonnet et al. 2022; Brown et al. 2023, 2025). However, the literature is generally lacking in detailed morphological descriptions of adult structures resulting from tissue-wide loss of caly in development that would be important for future work to model BAP1-associated health concerns, and specifically lacking such detailed reports for RNAi allele calyHMC04109 across a range of gal4 drivers.

Given the importance of BAP1 in suppression of tumorigenesis and metastasis, it is important to complement the characterizations of other chromatin regulators and clonal analysis of caly in development reported in published literature with a detailed description of how caly knockdown across different tissue-wide contexts in development affects patterning and gross morphology. This will enable us to further understand the role of caly in development and prioritize contexts for further study to elucidate the role of BAP1 as a tumor suppressor in human cancer.

Here, we characterize phenotypes arising from knockdown of caly using inducible RNAi allele calyHMC04109 in developing tissues. RNAi to caly in multiple contexts in the developing eye and wing increased lethality and led to a spectrum of phenotypes in surviving flies. RNAi in the early eye resulted in a range of reduced eye sizes and outgrowths, some of which differentiated into structures that resembled antennae, maxillary palps, or even legs. Other outgrowths were difficult to classify and resembled tumor-like outgrowths seen in other fly cancer models. In contrast, RNAi in the differentiating eye results in eyes of slightly increased size that appeared normal morphologically. RNAi in the wing led to abnormalities affecting patterning, including wing vein phenotypes, blisters, and crumpling. These phenotypes are similar to those reported due to loss of function of other chromatin regulators and validate the allele calyHMC04109 as a tool in future mechanistic studies to understand the role of BAP1 in disease and cancer.

Materials and methods

Rigor and reproducibility

The reported work represents reproducible experiments that reflect a minimum of 3 well-controlled, independent trials. For most experiments, at least one set of trials was done by a different lab member than the other 2 sets of trials to reduce the chance of replicating unintended observer bias.

Statistical analysis

Eye area, head height, head width, and wing area were measured with ImageJ software. Raw area measurements in pixels were normalized in order to facilitate comparisons between genotypes (as is the standard in the field) using Excel by calculating the mean of the data from the control genotype and then dividing individual data points for the control genotype and other genotypes by the mean of the control genotype in Excel. Raw survival data consisting of flies surviving to adulthood vs those that died before adulthood were normalized by dividing the number in each category by the total number of flies (both surviving and not surviving) and multiplying by 100 to establish percentages. Normalized measurements and survival data were then graphed using Excel (Figs. 2a, k, 4a, 5a, and 6a, f) and GraphPad Prism (Figs. 2h to j, 3i to k, 4b, and 5b, e). Categorical analysis to analyze survival (Figs. 2a, 4a, 5a, and 6a, F) or type of outgrowths (Fig. 2k) used chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate, calculated in GraphPad Prism. t test (Figs. 2h to j, 4b, and 5d, e) and one-way ANOVA analysis with multiple comparisons (Fig. 3i to k) assessed changes in eye area, head height, head width, or wing size. P-values, raw measurements, and normalized values are listed in Supplementary File 1.

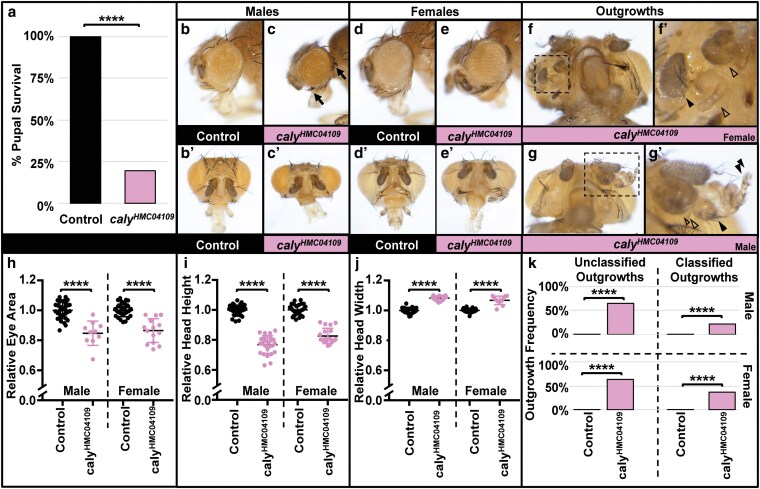

Fig. 2.

RNAi to caly using ey-gal4 reduces pupal survival, causes eye shape and size phenotypes, and causes tissue outgrowths. Experiments were performed at 25 °C. a) Graph summarizing the percent pupal survival for control ey-gal4/+ flies (left) vs driving RNAi to caly using ey-gal4 and calyHMC04109 (right). RNAi to caly dramatically reduces survival of pupae to adulthood. **** indicates P < 0.0001 in both chi-square and Fisher's exact tests. b to g´) eyes/heads in b to c´ and g to g´ show males, and images in d to f´ show females. Eyes in b, c, d, and e are at the same scale to allow for comparisons to each other; eyes in b´, c´, d´, and e´ are at the same scale to allow for comparisons to each other. b, d) ey-gal4/+ eye profile showing control eye shape and size. b´, d´) Anterior images of heads of the genotypes shown in b and d. c, e) RNAi to caly using ey-gal4 (ey > calyHMC04109) causes a reduction in eye size, rounder eye shape, and change in bristle pattern (highlighted by the solid arrows in c). c´, e´) Anterior view highlights that the head is shorter but wider. f to g´) In addition to eye size and shape changes, eyes contain a variety of different outgrowths, including outgrowths that appear to have differentiated into structures resembling antennae, maxillary palps, or legs (solid arrowheads), whereas others seem to lack obvious morphology associated with specific structures and cannot be classified morphologically based on visual inspection (arrowhead without fill). Additional view of outgrowths from the head in f to f´ is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1e–1e´, and additional images of ey > calyHMC04109 heads are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, including an outgrowth of almost an entire leg from the eye in Supplementary Fig. 1c. h to j) Graphs summarizing h) relative eye area, i) relative head height, and j) relative head width for ey-gal4/+ control males (first lane) and females (third lane) vs ey > calyHMC04109 males (second lane) and females (fourth lane). **** indicates P < 0.0001 in t tests. Eye image indicating how head height and width were measured is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2a. To highlight the head shape changes, we also graphed the ratio of width-to-height in Supplementary Fig. 2b. k) Graphs quantifying the percent of eyes with outgrowths in ey-gal4/+ controls (left lanes) vs ey > calyHMC04109 (right lanes) when the outgrowths have unclassifiable outgrowths (left graphs) or outgrowths with classifiable morphology (such as legs, antennae, or palps) (right graphs) for males (upper graphs) and females (bottom graphs). **** indicates P < 0.0001 in both chi-square and Fisher's exact tests.

Fig. 4.

RNAi to caly using GMR-gal4 does not affect morphology but causes increased eye size. Experiments in this figure were performed at 25 °C. a) Graph summarizing the percent pupal survival in control GMR-gal4/+ flies (left) vs driving RNAi to caly using GMR-gal4 and calyHMC04109 (GMR > calyHMC04109) (right). NS indicates not significant in both chi-square (P = 0.087) and Fisher's (P = 0.12) exact tests. b) Graph showing relative eye area in males (left 2 lanes) and females (right 2 lanes) of control GMR-gal4/+ flies (first and third lanes) and GMR > calyHMC04109 flies (second and fourth lanes) relative eye area males and females. Eye size increases by approximately 11.2%. The eye morphology appears normal despite the increased size. **** indicates P < 0.0001 in t tests. c, e) Control GMR-gal4/+ eyes. d, f) GMR > calyHMC04109 eye. Eyes in c, d, e, and f are at the same scale to allow for comparisons to each other.

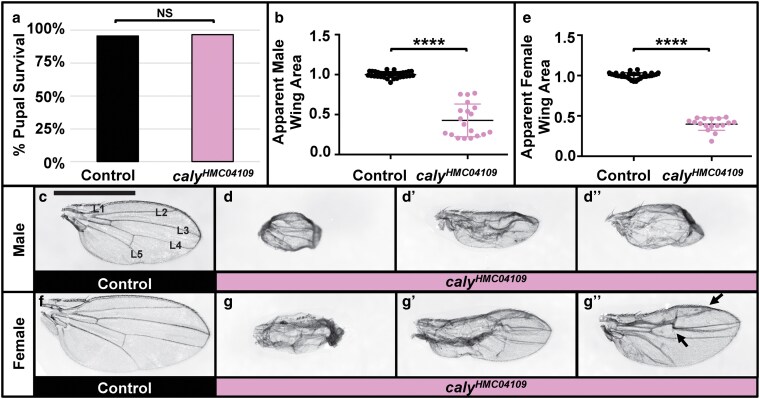

Fig. 5.

RNAi to caly using ms1096-gal4 disrupts wing patterning and reduces wing size. Experiments in this figure were performed at 25 °C. a) Graph summarizing the percent pupal survival in control ms1096-gal4/+ flies vs driving RNAi to caly using ms1096-gal4 and calyHMC04109 (ms1096 > calyHMC04109). RNAi to caly does not affect pupal survival. NS indicates not significant in chi-square (P = 0.7468) and Fisher's exact (P > 0.9999) tests. b to d´´) data for males; e to g´´) data for females. b, e) Relative apparent wing area decreases upon RNAi to caly (right) compared to controls (left) for males (b) and females (e). c, f) Control ms1096-gal4 wing. Wings in c to g´´ are at the same scale to allow for comparisons; scale bar in C represents 1 mm and applies to wings in c to d´´ and f to g´´. Wing veins L1 to L5 are labeled in C for clarity. d to d´´, g to g´´) Both male (d to d´´) and female (g to g´´) ms1096 > calyHMC04109 wings have a range of phenotypes from very small wings with abnormal shapes including “cupping” of the wing or curling of the wing margins (d, g) to wings with moderate phenotypes that show less of a decrease in apparent wing area but still do not flatten properly even once inflated (d´, g´) to wings that with even milder phenotypes that still show abnormal patterning (arrows) (d´´, g´´).

Fig. 6.

RNAi to caly across the wing using c765-gal4 reduces survival and causes wing abnormalities. a to e) Experiments in a to e were performed at 21 °C. a) Graph summarizing the percent pupal survival in control c765-gal4/+ flies vs driving RNAi to caly using c765-gal4 and calyHMC04109 (c765 > calyHMC04109). There is a reproducible trend of decreased survival upon caly RNAi, but this is not statistically significant. NS indicates not significant in chi-square (P = 0.1788) and Fisher's exact (P = 0.2577) tests. b, d) Control c765-gal4/+ wing. Wings in b to e and g to j are at the same scale to allow for comparisons; scale bar in b represents 1 mm and applies to wings in b to e and g to j. Wing veins L1 to L5 are labeled in b for clarity, c, e) c765 > calyHMC04109 wing. c765 > calyHMC04109 wings have disrupted wing patterning. Male wings are shown in b and c, and female wings in d and e. f to j) Experiments in f to j were performed at 25 °C. f) Graph summarizing the percent pupal survival in control c765-gal4/+ flies vs c765 > calyHMC04109 flies. Reproducibly, there is statistically significant decreased survival upon caly RNAi at the higher temperature of 25 °C compared to the survival at 21 °C shown in a. **** indicates P < 0.0001 in both chi-square and Fisher's exact tests. g, i) c765-gal4/+ wing. h, j) c765 > calyHMC04109 wing. RNAi to caly disrupts wing patterning including occasional loss of longitudinal or crossvein material (arrows) and causes curling at the wing margin; this is more common in male wings. Male wings are shown in g and h, and female wings in i and j.

Fig. 3.

Eyes composed largely of homozygous mutant caly tissue in the eye phenocopies caly RNAi by changing eye shape and size, and causing eye outgrowths. Experiments were performed at 25 °C. Images in a to d´ show males and in e to h´ show females generated using eyFLP, an FRT42D chromosome with cell-lethal mutation l(2)R111 and a pW+ insertion, and an FRT42D chromosome either wild-type or containing mutations in Asx or caly. Due to the cell-lethal mutation, tissue homozygous for the l(2)R111 chromosome dies. Remaining tissue is either red heterozygous tissue that did not undergo mitotic recombination or white homozygous wildtype, Asx, or caly mutant tissue. Due to the lighting, white tissue in these images appears to have a yellow or orange hue. Eyes in a, b, c, d, e, f, g, and h are at the same scale to allow for comparisons to each other; eyes in a´, b´, c´, d´, e´, f´, g´, and h´ are at the same scale to allow for comparisons to each other. a, e) Eyes containing FRT42D control tissue. a´, e´) Anterior view showing heads of the genotypes from a, e. b, f) Eyes containing Asx22P4 mutant tissue. b´, f´) Anterior view showing heads of the genotypes from b, f. c, g) Eyes containing caly2 null mutant tissue. (c´, g´) Anterior view showing heads of the genotypes from c, g. d, h) Eyes containing calyC131S catalytically inactive mutant tissue. d´, h´) Anterior view showing heads of the genotypes from d, h. Eyes containing Asx and caly mutant tissue are round and smaller with bristle abnormalities (example with an arrow in b) and with occasional outgrowths that differentiate into structures resembling antennal or other morphology (example with a solid arrowhead in b) or with no clear morphology (example with an open arrowhead in d´). i to k) Graphs summarizing i) relative eye area, j) relative head height, and k) relative head width for eyes containing control tissue (lanes 1 and 5, black), Asx22P4 mutant tissue (lanes 2 and 6), caly2 mutant tissue (lanes 3 and 7), and calyC131S mutant tissue (lanes 4 and 8). Eye image indicating how head height and width were measured is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2a. Males are shown in lanes 1 to 4 and females in lanes 5 to 8 for each graph. As with caly RNAi in Fig. 1, heads with Asx or caly mutant tissue have smaller eyes, reduced height, and increased width compared to controls. To highlight the head shape changes, we graphed the ratio of width-to-height in Supplementary Fig. 2c. In i to k, NS indicates not significant, * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01, *** indicates P < 0.001, and **** indicates P < 0.0001.

Drosophila experiments

Crosses at the indicated temperatures were set up on standard Drosophila medium as in our previous work (Yan et al. 2009; Yan et al. 2010; Washington et al. 2020; Reimels et al. 2024). In each trial for each experiment, crosses used food prepared in the same batch and were incubated in close proximity to experience the same environment to rule out unintended environmental variables or food batch variations. Gal4 drivers were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock center or other labs in the Drosophila community (for details, please see Table 1). caly RNAi calyHMC04109, and cell lethal l(2)cl-R111 were from the Bloomington Stock center, and caly and Asx alleles were graciously provided by Dr. J. Müller (de Ayala Alonso et al. 2007; Bonnet et al. 2022).

Table 1.

Table of reagents used with corresponding identifiers.

| Drosophila strains | ||

|---|---|---|

| Strain | Source | Identifier |

| w1118 | The fly community and Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC) | BL-3605, BL-5905 and others RRID:BDSC_3605, RRID:BDSC_5905 |

| caly HMC04109 | BDSC | Can be obtained from BDSC, 56888 RRID:BDSC_56888 |

| ey-gal4 | Hariharan lab | |

| c765-gal4 | BDSC, NYC fly community | Can be obtained from BDSC, BL-36523 RRID:BDSC_36523 |

| ms1096-gal4 | BDSC | Can be obtained from BDSC, BL-8696 RRID:BDSC_8696 |

| GMR-gal4 | BDSC | Can be obtained from BDSC, BL-8605 RRID:BDSC_8605 |

| FRT42D | BDSC | Can be obtained from BDSC, BL-5626 RRID:BDSC_5626 |

| y, w, eyFLP, GMR-lacZ; FRT42D, l(2)cl-R111, w+/CyO | BDSC | Can be obtained from BDSC, BL-5617 RRID:BDSC_5617 |

| FRT40, FRT42D y+caly2/CyO,ubi-GFP | Gift from Müller Lab | |

| FRT40, FRT42D y+calyC131S/CyO,ubi-GFP | Gift from Müller Lab | |

| FRT40, FRT42D y+ Asx22P4/CyO,ubi-GFP | Gift from Müller Lab | |

| Software | |

|---|---|

| Program | Source |

| Image J | https://imagej.net/ij/ |

| GraphPad Prism | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| Microsoft Excel | https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel |

Pupal lethality/survival experiments

For survival experiments, pupal cases of the indicated genotypes were scored as dead (in which dead pupae remained in the pupal cases) or empty (from which surviving flies had eclosed) and counted at 26 d (21 °C) or 18 d (25 °C) as in our previous study (Singh et al. 2023). Dead pupal cases are easily distinguished from empty pupal cases or from developing pupae that are still alive and have not yet eclosed.

Image analysis and processing

Adult eyes and wings were photographed using a Nikon DS-Fi3 microscope camera and saved as TIFF files. All eyes and wings within each trial of an individual experiment were photographed at the same magnification to allow for images to be compared to each other to determine relative size. Raw wing images were converted to grayscale and cropped in Adobe Photoshop. The same degree of resizing and cropping were applied in parallel to all images from the same experiment to maintain the ability for figure panels to be compared. A scale bar equivalent to 1 mm is applied to the first control wing in Figs. 5 and 6 and applies to all the wings in the corresponding set. Brightness and contrast of eye and wing images were adjusted in Adobe Photoshop to maximize clarity; adjustments were applied to the entire images. Genotypes are summarized below and identifiers are listed in Table 1.

Genotypes of flies in images or graphs

w; ey-gal4/+ (Fig. 2b to b´, d to d´; left genotype in graphs in Fig. 2a, h to k, Supplementary Fig. 2b)

w; ey-gal4/calyHMC04019 (Fig. 2c to c´, e to e´, f to g´, Supplementary Fig. 1a to e´; right genotype in graphs in Fig. 2a, h to k, Supplementary Fig. 2b)

y w eyFLP; FRT42D/FRT42D l(2)cl-R111 (Fig. 3a to a´, e to e´; left-most genotype in graphs in 3i to k, Supplementary Fig. 2c)

y w eyFLP; FRT42D Asx22P4/FRT42D l(2)cl-R111 (Fig. 3b to b´, f to f´; second genotype in graphs in 3i to k, Supplementary Fig. 2c)

y w eyFLP; FRT42D caly2/FRT42D l(2)cl-R111 (Fig. 3c to c´, g to g´; third genotype in graphs in 3i to k, Supplementary Fig. 2c)

y w eyFLP; FRT42D calyC131S/FRT42D l(2)cl-R111 (Fig. 3d to d´, h to h´; right-most genotype in graphs in 3i to k, Supplementary Fig. 2c)

w; GMR-gal4/+ (Fig. 4c and e; left genotype in graphs in Fig. 4a and b)

w; GMR-gal4/calyHMC04019 (Fig. 4d and f; right genotype in graphs in Fig. 4a and b)

w, ms1096-gal4 (Fig. 5c, left genotype in graph in Fig. 5a and b)

w, ms1096-gal4/+ (Fig. 5f, left genotype in graph in Fig. 5a and e)

ms0196-gal4; calyHMC04019/+ (Fig. 5d to d´´; right genotype in graph in 5a and b)

ms0196-gal4/+; calyHMC04019/+ (Fig. 5g to g´´; right genotype in graph in 5a and e)

w; c765-gal4/+ (Fig. 6b, d, g, and i; left bar in graphs in Fig. 6a and f)

w; calyHMC04019/+; c765-gal4/+ (Fig. 6c, e, h, and j; right bar in graphs in 6a and f)

Results and discussion

Given the importance of BAP1 and the range of phenotypes reported for other Polycomb regulators in Drosophila, we utilized several Gal4 drivers that drive expression in the developing eye or wing to establish the phenotypes of RNAi allele calyHMC04109. Characterizing tissue-wide knockdown has the potential to (i) reinforce previous studies (e.g. Bonnet et al. 2022) that focused on characterizing caly phenotypes in development and mention the phenotypes in adult morphology due to random caly mutant clones and also (ii) reveal previously unreported phenotypes that require larger swaths of tissue undergoing caly knockdown to be observed and/or for which consistent knockdown in only one tissue rather than random clones is required for quantification.

RNAi to or mutation in caly in the early eye caused lethality and a range of phenotypes

The driver ey-gal4 has been reported to express in the early cells of the imaginal eye disc (Quiring et al. 1994; Halder et al. 1998; Hazelett et al. 1998) and also in other tissues, including the nervous system, larval brain, and genital discs (Adachi et al. 2003; Weasner et al. 2009). Inducing RNAi with calyHMC04109 and ey-gal4 resulted in substantial pupal lethality compared to controls (quantified in Fig. 2a). ey > calyHMC04109 flies that survived to adulthood demonstrated a range of phenotypes (Fig. 2b to k) including eyes that appeared morphologically almost like control eyes as noted in a previous report (Brown et al. 2023) and rough eyes of reduced size (Fig. 2c to c´ for males, 2e to e´ for females; quantified in Fig. 2h; additional examples in Supplementary Fig. 1) compared to control eyes (Fig. 2b to b´ for males, Fig. 2d to d´ for females). The heads were reduced in height compared to controls (for anterior view of the eyes, Fig. 2c´ compared to 2b´ for males, Fig. 2e´ compared to 2d´ for females; quantified in Fig. 2i). In many cases, the eye tissue appeared to be bulging (Fig. 2c´ and e´), and despite the reduced area at the base of the eye (Fig. 2h), overall width of the head increased compared to controls (Fig. 2j). This is highlighted by an increase in the ratio of width to height compared to control eyes (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Most eyes showed bristle phenotypes in the anterior region in the periphery of the eye (arrows in Fig. 2c), and we also saw what appeared to be antennal duplications or other outgrowths (Fig. 2f to g´, Supplementary Fig. 1). Some of these outgrowths resembled specific differentiated structures like antennae, maxillary palps, or even legs due to morphological characteristics such as shape, bristle pattern, or even segmentation which we refer to as “classified outgrowths.” On one occasion, we saw almost an entire leg growing from the head with what may have been ommatidia on its distal tip (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Many of the “classified” outgrowths did not form complete structures, so the identity of the type of tissue forming was not always conclusive or unambiguous. Therefore, we did not further quantify these outgrowths based on presumed tissue identity. Curiously, the Brown et al. (2023) examination of imaginal eye discs driving caly RNAi using the same transgene reported ectopic expression of Antp posterior to the morphogenetic furrow that could explain some of these phenotypes. It is unclear why we see this range of phenotypes in adults that was not reported in Brown et al. (2023), despite the clear Antp dysregulation they saw for this genotype, which also reinforced similar Antp staining in caly mutant clones in mosaic discs previously reported (Bonnet et al., 2022) and which has also been seen for caly RNAi driven by DE-gal4 (Brown et al., 2025). We speculate that the substantial lethality of this genotype could have resulted in lethality of such flies in that study under slightly different conditions. Similar outgrowths, including transformations into legs, were seen upon creating random clones of caly mutant tissue in antennae (Bonnet et al. 2022). Extensive immunostaining of such clones in larval discs confirmed HOX gene upregulation and homeotic transformation (Bonnet et al., 2022). In contrast to these homeotic outgrowths produced by random clones in that study, our ey-gal4 mediated caly RNAi revealed additional overgrowths that lacked obvious morphological characteristics and thus were difficult to classify appearing as outgrown tissue covered by cuticle without other obviously identifiable features which we refer to as “unclassified outgrowths” (Fig. 2f to g´, Supplementary Fig. 1; quantification of relative “classified” vs “unclassified” outgrowths, Fig. 2k). We also observed outgrowths from tissue other than the antennae (Fig. 2f to f´). Previous reports of adult phenotypes resulting from random heat shock-induced clones throughout the eye and head described normal morphology for clones in regions of the head other than the antennae (Bonnet et al. 2022). Taken together with the variety of other phenotypes we observed from tissue-wide knockdown, including bristle abnormalities in the anterior region of the eye, eye area reduction, head shape phenotypes, and outgrowths outside the antennae, we speculate that some phenotypes require a minimum amount of caly-knocked down tissue. Alternate models include the possibility that wild-type tissue (absent in contexts of tissue-wide knockdown) may nonautonomously influence mutant tissue to correct patterning phenotypes or that the timing of the heat shock to induce random clones could differ from ey-gal4-mediated expression in ways necessary to elicit these phenotypes.

To establish if ey > calyHMC04109 phenotypes resulted from knockdown of caly specifically and to rule out off-target effects of using this RNAi allele, we generated eyes containing primarily caly mutant tissue for null allele caly2 (de Ayala Alonso et al. 2007) and for catalytically inactive allele calyC131S (Bonnet et al. 2022) by utilizing the FLP/FRT system and a cell-lethal mutation on the control 2R chromosome. yweyFLP; FRT42D l(2)/40AFRT,FRT42D caly2 and yweyFLP; FRT42D l(2)/40AFRT,FRT42D calyC131S eyes contained heterozygous tissue (red, which did not undergo mitotic recombination) and primarily caly mutant tissue (white) (Fig. 3c to d´, g to h´). As in ey > calyHMC04109 eyes (Fig. 2, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2), these eyes were rough, round, and generally showed reduced eye area, reduced head height, and increased head width phenotypes (Fig. 3i to k) compared to control eyes (Fig. 3a to a´, e to e´, i to k) although this was not always statistically significant for the caly alleles as indicated in the figure. The lack of statistical significance could be due to the mosaic nature of the eyes, which also contained heterozygous tissue, rather than eye-wide caly knockdown produced when using ey-gal4 or due to different degrees of knockdown of caly function. To highlight the head shape changes, we graphed the ratio of width-to-height in Supplementary Fig. 2c. These phenotypes also resembled eyes composed of primarily Asx mutant tissue, which we included as an additional control because Asx is the other subunit of PR-DUB (Fig. 3b to b´, f to f´). We also observed eye outgrowths (Fig. 3b and c). Eyes containing Asx and caly mutant tissue also exhibited bristle abnormalities and occasional outgrowths that differentiated into structures resembling antennae, legs, or other morphology (example in Fig. 3b) or with no clear morphology (example in Fig. 3d´). These outgrowths resembled those seen upon caly RNAi (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1) and those seen previously upon generating random heat shock-induced homozygous clones of calyC131S (Bonnet et al. 2022) or homozygous clones of Asxku256 (Halachmi et al. 2007) in the antennae, but also sometimes occurred in regions outside the antennae (e.g. Fig. 3b), unlike those reported in these previous studies.

We cannot rule out that off-target effects contributed to the phenotypes in ey > calyHMC04109 flies, but the similarity of ey > calyHMC04109 phenotypes compared to eyes containing primarily caly2 or calyC131S mutant tissue would be consistent with these phenotypes resulting from loss-of-function in caly, not due to RNAi off-target effects on other genes. The similarity in phenotypes compared to eyes containing primarily Asx mutant tissue would be consistent with these phenotypes resulting more specifically from loss of PR-DUB activity. These phenotypes also resembled the phenotypes of dysregulating chromatin and interfering with Polycomb group proteins, their targets, and Pax6 (Plaza et al. 2001; Nègre et al. 2006; Luque and Milán 2007; Arancio et al. 2010; Zhu et al. 2018), over-expression of OSA (Baig et al. 2010) or dysregulating other regulators of chromatin architecture like Defective proventriculus (Dve) (Puli et al. 2024). It will be important for future work to assess the levels and patterns of Pax6, OSA, Dve, and other Polycomb group targets in developing eye discs to establish if their dysregulation underlies these phenotypes. In fact, dysregulation of many chromatin regulators and loss of mis-expression of Polycomb targets also demonstrate similar outgrowths, some of which appear to take on differentiated morphology resembling other structures such as cuticle or leg outgrowths we saw here (Plaza et al. 2001; Dong et al. 2002; Dey et al. 2009; Puli et al. 2024) including the ectopic legs seen upon overexpressing of Antennapedia (Antp) (Schneuwly et al. 1987). This is also consistent with the ectopic Antp expression seen broadly posterior to the morphogenetic furrow and in the anterior region of the antennal eye-antennal discs upon loss of caly or Asx (Halachmi et al. 2007; Bonnet et al. 2022; Brown et al. 2023). It will be important for future work to extend this characterization to additional Hox genes and to markers specific to presumptive, leg, palp, and antennal tissue identity to better understand the nature of these transformations and to establish conclusively (rather than visually) the molecular identity of these transformed tissues.

RNAi to caly in the differentiating eye causes mild overgrowth

GMR-gal4 drives expression in cells posterior to the morphogenetic furrow in the differentiating eye (Hay et al. 1994; Freeman 1996) and has also been described to express in the wing, midgut, salivary glands, and trachea (Li et al. 2012; Ray and Lakhotia 2015; Escobedo et al. 2021). Inducing RNAi with calyHMC04109 and GMR-gal4 did not affect survival (Fig. 4a) and resulted in eyes of apparent normal morphology but increased eye area (quantified in Fig. 4b, eye examples Fig. 4d and F) compared to controls (Fig. 4c and e). Future work should explore if this increase in eye size results from an increase in the number of cells (for example due to increased proliferation or a decrease in apoptosis) or other mechanisms such as dysregulation of organ size homeostasis. Based on the striking differences between eye phenotypes depending on driving RNAi with ey-gal4 (Fig. 2) or with GMR-gal4 (Fig. 4), we speculate that Calypso might play different roles in early developing, actively proliferating tissue vs its roles in primarily differentiated tissue.

RNAi to caly in the dorsal wing caused wing vein abnormalities, shriveling, and “cupping”

ms1096-gal4 drives expression in the dorsal region of the wing disc pouch (Guillén et al. 1995; Rodan et al. 2002) but has also been described to drive expression in halteres, eye discs, and weak expression in ventral regions, including the ventral cuticle (Jonchere and Bennett 2013; Shukla et al. 2014). Inducing RNAi with calyHMC04109 did not statistically significantly affect survival (quantified in Fig. 5a). Given the overlap in expression in eye tissues between ey-gal4 and ms1096-gal4, it is unclear why there were no survival effects due to driving RNAi using ms1096-gal4 despite the striking lethality seen when driving RNAi using ey-gal4 (Fig. 2a). We speculate that this could be due to differences in the level or precise pattern of the eye-specific expression from each driver or due to ey-gal4-directed expression in other tissues that does not overlap with ms1096-gal4. ms1096 > calyHMC04109 wings showed a range of phenotypes (Fig. 5d to d´´, g to g´´, apparent size quantified in Fig. 5b and e) including disruption of wing vein pattern and loss of wing veins, blistering, crumpling/shriveling, a “cupped” wing shape, and a reduction in apparent overall wing size (crumpling and “cupping” interfered with measuring exact wing size) compared to controls (Fig. 5c and f). The wing vein abnormalities resemble those seen upon dysregulating other chromatin regulators and homeotic regulators such as HDAC complex components (Barnes et al. 2018), SWI-SNF chromatin remodeling complexes in the presence of tissue damage (Tian and Smith-Bolton 2021), and trithorax group member Absent small and homeotic 2 (ash2) (Amorós et al. 2002). The shriveling/crumpling phenotype resembled phenotypes seen for knocking down or mutating chromatin and homeotic genes, including Asx (Bischoff et al. 2009), DISCO Interacting Protein 1 (DIP1) (Bondos et al. 2004), L(3)mbt (Richter et al. 2011), Antennapedia (Antp) (Fang et al. 2022), and PcG protein Pleiohomeotic (Pho) (Harvey et al. 2013), and generally appear similar to what has been characterized as a “PcG syndrome” (de Ayala Alonso et al. 2007). The “cupping” phenotype has also been seen upon reduction in HDAC proteins (Barnes et al. 2018) and ash2 (Amorós et al. 2002), or deleting Polycomb response elements in Polycomb target genes (Sipos et al. 2007). Curiously, while tissue-wide caly knockdown resembled these other PcG phenotypes, including by Asx mutant clones in the wing (Bischoff et al. 2009), in some contexts, caly mutant clones have been reported to cause wing-to-haltere transformation (Bonnet et al. 2022). This may highlight the context-dependent consequences of modulating caly.

RNAi to caly across the developing wing caused wing vein abnormalities and curling at the wing margin

c765-gal4 drives expression across the wing imaginal disc (Guillen et al. 1995; de Celis et al. 1996; Nellen et al. 1996) and also generally in the developing thorax (Gomez-Skarmeta et al. 1996; Yang et al. 2012), in leg discs (Azpiazu and Morata 2002), and in the brain (Rodan et al. 2002). Inducing RNAi across the developing wing with calyHMC04109 and c765-gal4 resulted in a trend of reduced survival at 21 °C (quantified in Fig. 6a) and this increased and became statistically significant at 25 °C (quantified in Fig. 6f). The increased severity is consistent with presumed higher gal4-mediated transgene expression known to occur with temperature increases due to the temperature responsive nature of the Gal4/UAS system. The wings of flies that survived showed a number of phenotypic abnormalities including loss of wing vein material, a failure of some wing veins to reach the wing margin, buckling of tissue, and curling at the wing margin which was variable at 21 °C (Fig. 6c and e) and increased at 25 °C (Fig. 6h and J) compared to controls (Fig. 6b, d, g, and i). These wing morphology phenotypes resembled but were weaker than those seen for ms1096-gal4 and similar to those seen for other chromatin regulators described above. Given well-documented patterns for signaling cascades important in wing development and in specification of specific structures like the wing veins or in overall wing size and shape, it will be important for future studies to establish which cells in the developing wing disc are contributing to these phenotypes to help establish the underlying mechanism.

The lethality of driving caly RNAi with drivers whose primary expression pattern is in tissues that themselves are not required for viability (e.g. eyes, wings) raises interesting questions regarding the cause of this lethality. It is possible that lethality resulted from effects on other tissues where these Gal4 drivers also induce expression. Another possibility is that this lethality was nonautonomous. A number of Drosophila cancer models describe changes in secreted factors upon overexpressing oncogenes or knocking down tumor suppressors. For example, overexpression of oncogenic Yki causes secretion of ImpL2, Pvf1, and Upd3 (Kwon et al. 2015; Song et al. 2019; Ding et al. 2021). In some cases, dysregulation of secreted factors can affect survival, for example by promoting systemic cachexia, coagulopathy, or renal dysfunction (Figueroa-Clarevega and Bilder 2015; Kwon et al. 2015; Hsi et al. 2023; Xu et al. 2023). Therefore, it is possible (i) that caly knockdown in these tissues caused a change in the secretion of specific factors that affect survival or (ii) that caly knockdown had other systemic or organ effects. As reviewed earlier, BAP1 is a known tumor suppressor and metastasis suppressor, and we noted tumor-like outgrowths in the eye. Therefore, the lethality of caly RNAi in certain tissues could also reflect metastasis of cells to other sites. In fact, BAP1 loss is associated with worse prognosis in UM. Pursuing these possible mechanisms in future work may shed light on the requirement for caly/BAP1 in development with implications for disease.

In addition to a role in cancer, heterozygous mutations in BAP1 are implicated in a neurodevelopmental syndrome known as Küry-Isidor syndrome (KURIS). This is characterized by developmental delay that affects walking and speech (Küry et al. 2022). Although we cannot rule out off-target effects resulting from RNAi allele calyHMC04109 in the differentiating eye (Fig. 4) or the wing (Figs. 5 and 6), eyes containing primarily caly2 and calyC131S (Fig. 3) phenocopied driving calyHMC04109 to induce RNAi in the early eye (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 1) as well as phenotypes associated with loss of other chromatin regulators. This is consistent with the calyHMC04109 allele being a useful tool to assess further the mechanisms underlying the role of BAP1 defects in cancer and in Küry-Isidor syndrome. Importantly, some eye outgrowths upon caly loss using both RNAi (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 1) and mutant alleles (Fig. 3) resemble tumor-like growths seen for other cancer models (Brumby and Richardson 2003; Pagliarini and Xu, 2003; Uhlirova et al. 2005; Yan et al. 2009; Ho et al. 2015) while others resemble homeotic transformations. Therefore, recapitulating caly loss in the early eye using calyHMC04109, caly2, and calyC131S could make an excellent developmental context to study the relationship between epigenetic dysregulation and tumor initiation to be pursued in future work.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M Mlodzik, U Weber, TK Das, J Chipuk, P Rangan, ZQ Pan, and the New York Fly community for invaluable discussions, input, scientific dialogue, and reagents. We thank D. Sethi, P. Karunaraj, K. Kalafsky, K. Braden, and F. Rosemann for discussion, technical support, and assistance in conducting experiments and maintaining essential laboratory functions. We thank Dr. J. Müller and his lab for generously providing us with fly stocks. We thank the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (NIH P40OD018537) for providing fly stocks and Flybase (NIH 5U41HG000739) for access to sequence and other information. In particular, we thank Flybase, which was used as an essential reference tool throughout this study (Gramates et al. 2022; Öztürk-Çolak et al. 2024).

Contributor Information

Max Luf, Department of Oncological Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, United States; The Tisch Cancer Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, United States.

Priya Begani, Department of Oncological Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, United States; The Tisch Cancer Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, United States; The Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, United States.

Anne M Bowcock, Department of Oncological Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, United States; The Tisch Cancer Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, United States; The Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, United States; Department of Genetics & Genomics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, United States; Department of Dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, United States.

Cathie M Pfleger, Department of Oncological Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, United States; The Tisch Cancer Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, United States; The Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, United States.

Data Availability

Drosophila strains used in this work (listed in Table 1) have been published previously (de Ayala Alonso et al. 2007; Bonnet et al. 2022) or are available from public stock centers. Raw data, normalized data for graphs in Figs. 2 to 6, and P values are listed in Supplementary File 1. The authors affirm that all data necessary for interpreting the data and drawing conclusions are present within the article text, the figures, table, and Supplementary File 1.

Supplemental material available at G3 online.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences R01GM135330 and R01GM122995, the National Cancer Institute R01CA161870, Department of Defense Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs ME240338, and the National Cancer Institute (Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA196521).

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Literature cited

- Adachi Y et al. 2003. Conserved cis-regulatory modules mediate complex neural expression patterns of the eyeless gene in the Drosophila brain. Mech Dev. 120:1113–1126. 10.1016/j.mod.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amorós M, Corominas M, Deák P, Serras F. 2002. The ash2 gene is involved in Drosophila wing development. Int J Dev Biol. 46:321–324. https://ijdb.ehu.eus/article/12068954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arancio W et al. 2010. The nucleosome remodeling factor ISWI functionally interacts with an evolutionarily conserved network of cellular factors. Genetics. 185:129–140. 10.1534/genetics.110.114256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azpiazu N, Morata G. 2002. Distinct functions of homothorax in leg development in Drosophila. Mech Dev. 119:55–67. 10.1016/S0925-4773(02)00295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baig J, Chanut F, Kornberg TB, Klebes A. 2010. The chromatin-remodeling protein Osa interacts with CyclinE in Drosophila eye imaginal discs. Genetics. 184:731–744. 10.1534/genetics.109.109967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes VL, Laity KA, Pilecki M, Pile LA. 2018. Systematic analysis of SIN3 histone modifying complex components during development. Sci Rep. 8:17048. 10.1038/s41598-018-35093-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman L, Nilsson B, Ragnarsson-Olding B, Seregard S. 2006. Uveal melanoma: a study on incidence of additional cancers in the Swedish population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 47:72–77. 10.1167/iovs.05-0884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff K, Ballew AC, Simon MA, O'Reilly AM. 2009. Wing defects in Drosophila xenicid mutant clones are caused by C-terminal deletion of additional sex combs (Asx). PLoS One. 4:e8106. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondos SE et al. 2004. Hox transcription factor ultrabithorax Ib physically and genetically interacts with disconnected interacting protein 1, a double-stranded RNA-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 279:26433–26444. 10.1074/jbc.M312842200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet J et al. 2022. PR-DUB preserves Polycomb repression by preventing excessive accumulation of H2Aub1, an antagonist of chromatin compaction. Genes Dev. 36:1046–1061. 10.1101/gad.350014.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bononi A et al. 2017. BAP1 regulates IP3R3-mediated Ca2+ flux to mitochondria suppressing cell transformation. Nature. 546:549–553. 10.1038/nature22798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bott M et al. 2011. The nuclear deubiquitinase BAP1 is commonly inactivated by somatic mutations and 3p21.1 losses in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Nat Genet. 43:668–762. 10.1038/ng.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown HE, Jean-Guillaume C, Weasner BP, Kumar JP. 2025. Differential regulation of eye specification in Drosophila by Polycomb Group epigenetic repressors. Development. 152:dev204317. 10.1242/dev.204317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown HE, Weasner BP, Weasner BM, Kumar JP. 2023. Polycomb safeguards imaginal disc specification through control of the Vestigial-Scalloped complex. Development. 150:dev201872. 10.1242/dev.201872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumby AM, Richardson HE. 2003. Scribble mutants cooperate with oncogenic Ras or Notch to cause neoplastic overgrowth in Drosophila. EMBO J. 22:5769–5779. 10.1093/emboj/cdg548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone M et al. 2012. BAP1 cancer syndrome: malignant mesothelioma, uveal and cutaneous melanoma, and MBAITs. J Transl Med. 10:179. 10.1186/1479-5876-10-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone M et al. 2015. Combined genetic and genealogic studies uncover a large BAP1 cancer syndrome kindred tracing back nine generations to a common ancestor from the 1700s. PLoS Genet. 11:e1005633. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway E et al. 2021. BAP1 enhances Polycomb repression by counteracting widespread H2AK119ub1 deposition and chromatin condensation. Mol Cell. 81:3526–3541. 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daou S et al. 2015. The BAP1/ASXL2 histone H2A deubiquitinase complex regulates cell proliferation and is disrupted in cancer. J Biol Chem. 290:28643–28663. 10.1074/jbc.M115.661553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ayala Alonso AG et al. 2007. A genetic screen identifies novel polycomb group genes in Drosophila. Genetics. 176:2099–2108. 10.1534/genetics.107.075739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Celis JF, Barrio R, Kafatos FC. 1996. A gene complex acting downstream of dpp in Drosophila wing morphogenesis. Nature. 381:421–424. 10.1038/381421a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey BK, Zhao XL, Popo-Ola E, Campos AR. 2009. Mutual regulation of the Drosophila disconnected (disco) and Distal-less (Dll) genes contributes to proximal-distal patterning of antenna and leg. Cell Tissue Res. 338:227–240. 10.1007/s00441-009-0865-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding G et al. 2021. Coordination of tumor growth and host wasting by tumor-derived Upd3. Cell Rep. 36:109553. 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong PD, Dicks JS, Panganiban G. 2002. Distal-less and homothorax regulate multiple targets to pattern the Drosophila antenna. Development. 129:1967–1974. 10.1242/dev.129.8.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobedo SE, Shah A, Easton AN, Hall H, Weake VM. 2021. Characterizing a gene expression toolkit for eye- and photoreceptor-specific expression in Drosophila. Fly (Austin). 15:73–88. 10.1080/19336934.2021.1915683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang C et al. 2022. The Hox gene Antennapedia is essential for wing development in insects. Development. 149:dev199841. 10.1242/dev.199841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field MG et al. 2018. Punctuated evolution of canonical genomic aberrations in uveal melanoma. Nat Commun. 9:116. 10.1038/s41467-017-02428-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa-Clarevega A, Bilder D. 2015. Malignant Drosophila tumors interrupt insulin signaling to induce cachexia-like wasting. Dev Cell. 33:47–55. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M. 1996. Reiterative use of the EGF receptor triggers differentiation of all cell types in the Drosophila eye. Cell. 87:651–660. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fursova NA et al. 2021. BAP1 constrains pervasive H2AK119ub1 to control the transcriptional potential of the genome. Genes Dev. 35:749–770. 10.1101/gad.347005.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Skarmeta JL, Diez del Corral R, de la Calle-Mustienes E, Ferré-Marcó D, Modolell J. 1996. Araucan and caupolican, two members of the novel iroquois complex, encode homeoproteins that control proneural and vein-forming genes. Cell. 85:95–105. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramates LS et al. 2022. FlyBase: a guided tour of highlighted features. Genetics. 220:iyac035. 10.1093/genetics/iyac035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillen I et al. 1995. The function of engrailed and the specification of Drosophila wing pattern. Development. 121:3447–3456. 10.1242/dev.121.10.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halachmi N, Schulze KL, Inbal A, Salzberg A. 2007. Additional sex combs affects antennal development by means of spatially restricted repression of Antp and wg. Dev Dyn. 236:2118–2130. 10.1002/dvdy.21239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder G et al. 1998. Eyeless initiates the expression of both sine oculis and eyes absent during Drosophila compound eye development. Development. 125:2181–2191. 10.1242/dev.125.12.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbour JW et al. 2010. Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanomas. Science. 330:1410–1413. 10.1126/science.1194472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey R, Schuster E, Jennings BH. 2013. Pleiohomeotic interacts with the core transcription elongation factor Spt5 to regulate gene expression in Drosophila. PLoS One. 8:e70184. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay BA, Wolff T, Rubin GM. 1994. Expression of baculovirus P35 prevents cell death in Drosophila. Development. 120:2121–2129. 10.1242/dev.120.8.2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazelett DJ, Bourouis M, Walldorf U, Treisman JE. 1998. Decapentaplegic and wingless are regulated by eyes absent and eyegone and interact to direct the pattern of retinal differentiation in the eye disc. Development. 125:3741–3751. 10.1242/dev.125.18.3741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho DM, Pallavi SK, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. 2015. The Notch-mediated hyperplasia circuitry in Drosophila reveals a Src-JNK signaling axis. Elife. 4:e05996. 10.7554/eLife.05996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsi TC, Ong KL, Sepers JJ, Kim J, Bilder D. 2023. Systemic coagulopathy promotes host lethality in a new Drosophila tumor model. Curr Biol. 33:3002–3010. 10.1016/j.cub.2023.05.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager MJ et al. 2020. Uveal melanoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 6:24. 10.1038/s41572-020-0158-0. Erratum in: Nat Rev Dis Primers 2022; 8: 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y et al. 2013. Exome sequencing identifies frequent inactivating mutations in BAP1, ARID1A and PBRM1 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas. Nat Genet. 45:1470–1473. 10.1038/ng.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonchere V, Bennett D. 2013. Validating RNAi phenotypes in Drosophila using a synthetic RNAi-resistant transgene. PLoS One. 8:e70489. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap S, Meel R, Singh L, Singh M. 2016. Uveal melanoma. Semin Diagn Pathol. 33:141–147. 10.1053/j.semdp.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küry S et al. 2022. Rare germline heterozygous missense variants in BRCA1-associated protein 1, BAP1, cause a syndromic neurodevelopmental disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 109:361–372. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon Y et al. 2015. Systemic organ wasting induced by localized expression of the secreted insulin/IGF antagonist ImpL2. Dev Cell. 33:36–46. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis PH, Mislove RF. 1947. New mutants report. Drosoph Inf Serv. 21:69. [Google Scholar]

- Li WZ, Li SL, Zheng HY, Zhang SP, Xue L. 2012. A broad expression profile of the GMR-GAL4 driver in Drosophila melanogaster. Genet Mol Res. 11:1997–2002. 10.4238/2012.August.6.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque CM, Milán M. 2007. Growth control in the proliferative region of the Drosophila eye-head primordium: the elbow-noc gene complex. Dev Biol. 301:327–339. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machida YJ, Machida Y, Vashisht AA, Wohlschlegel JA, Dutta A. 2009. The deubiquitinating enzyme BAP1 regulates cell growth via interaction with HCF-1. J Biol Chem. 284:34179–34188. 10.1074/jbc.M109.046755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nègre N et al. 2006. Chromosomal distribution of PcG proteins during Drosophila development. PLoS Biol. 4:e170. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nellen D, Burke R, Struhl G, Basler K. 1996. Direct and long-range action of a DPP morphogen gradient. Cell. 85:357–368. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk-Çolak A et al. 2024. FlyBase: updates to the Drosophila genes and genomes database. Genetics. 227:iyad211. 10.1093/genetics/iyad211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliarini RA, Xu T. 2003. A genetic screen in Drosophila for metastatic behavior. Science. 302:1227–1231. 10.1126/science.1088474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaza S et al. 2001. Molecular basis for the inhibition of Drosophila eye development by Antennapedia. EMBO J. 20:802–811. 10.1093/emboj/20.4.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puli OR et al. 2024. Genetic mechanism regulating diversity in the placement of eyes on the head of animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 121:e2316244121. 10.1073/pnas.2316244121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiring R, Walldorf U, Kloter U, Gehring WJ. 1994. Homology of the eyeless gene of Drosophila to the small eye gene in mice and Aniridia in humans. Science. 265:785–789. 10.1126/science.7914031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray M, Lakhotia SC. 2015. The commonly used eye-specific sev-GAL4 and GMR-GAL4 drivers in Drosophila melanogaster are expressed in tissues other than eyes also. J Genet. 94:407–416. 10.1007/s12041-015-0535-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimels TA et al. 2024. Rabex-5 E3 and Rab5 GEF domains differ in their regulation of Ras, Notch, and PI3K signaling in Drosophila wing development. PLoS One. 19:e0312274. 10.1371/journal.pone.0312274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter C, Oktaba K, Steinmann J, Müller J, Knoblich JA. 2011. The tumour suppressor L(3)mbt inhibits neuroepithelial proliferation and acts on insulator elements. Nat Cell Biol. 13:1029–1039. 10.1038/ncb2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts CJ et al. 2018. The cancer genome atlas comprehensive molecular characterization of renal cell carcinoma. Cell Rep. 23:313–326.e5. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson AG et al. 2017. Integrative analysis identifies four molecular and clinical subsets in uveal melanoma. Cancer Cell. 32:204–220.e15. 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodan AR, Kiger JA, Heberlein U. 2002. Functional dissection of neuroanatomical loci regulating ethanol sensitivity in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 22:9490–9501. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09490.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuermann JC et al. 2010. Histone H2A deubiquitinase activity of the Polycomb repressive complex PR-DUB. Nature. 465:243–247. 10.1038/nature08966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneuwly S, Klemenz R, Gehring WJ. 1987. Redesigning the body plan of Drosophila by ectopic expression of the homoeotic gene Antennapedia. Nature. 325:816–818. 10.1038/325816a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla V, Habibn F, Kulkarni A, Ratnaparkhi GS. 2014. Gene duplication, lineage-specific expansion, and subfunctionalization in the MADF-BESS family patterns the Drosophila Wing Hinge. Genetics. 196:481–496. 10.1534/genetics.113.160531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J, Karunaraj P, Luf M, Pfleger CM. 2023. Lysines K117 and K147 play conserved roles in Ras activation from Drosophila to mammals. G3 (Bethesda). 13:jkad201. 10.1093/g3journal/jkad201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipos L, Kozma G, Molnár E, Bender W. 2007. In situ dissection of a Polycomb response element in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 104:12416–12421. 10.1073/pnas.0703144104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W et al. 2019. Tumor-derived ligands trigger tumor growth and host wasting via differential MEK activation. Dev Cell. 48:277–286. 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa JR et al. 2011. Germline BAP1 mutations predispose to malignant mesothelioma. Nat Genet. 43:1022–1025. 10.1038/ng.912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y, Smith-Bolton RK. 2021. Regulation of growth and cell fate during tissue regeneration by the two SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complexes of Drosophila. Genetics. 217:1–16. 10.1093/genetics/iyaa028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlirova M, Jasper H, Bohmann D. 2005. Non-cell-autonomous induction of tissue overgrowth by JNK/Ras cooperation in a Drosophila tumor model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 102:13123–13128. 10.1073/pnas.0504170102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington C et al. 2020. A conserved, N-terminal tyrosine signal directs Ras for inhibition by Rabex-5. PLoS Genet. 16:e1008715. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weasner BM, Weasner B, Deyoung SM, Michaels SD, Kumar JP. 2009. Transcriptional activities of the Pax6 gene eyeless regulate tissue specificity of ectopic eye formation in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 334:492–502. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner T et al. 2011. Germline mutations in BAP1 predispose to melanocytic tumors. Nat Genet. 43:1018–1021. 10.1038/ng.910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Li G, Chen Y, Ye X, Song W. 2023. A novel antidiuretic hormone governs tumour-induced renal dysfunction. Nature. 624:425–432. 10.1038/s41586-023-06833-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H, Chin ML, Horvath EA, Kane EA, Pfleger CM. 2009. Impairment of ubiquitylation by mutation in Drosophila E1 promotes both cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous Ras-ERK activation in vivo. J Cell Sci. 122:1461–1470. 10.1242/jcs.042267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H, Jahanshahi M, Horvath EA, Liu HY, Pfleger CM. 2010. Rabex-5 ubiquitin ligase activity restricts Ras signaling to establish pathway homeostasis in vivo in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 20:1378–1382. 10.1016/j.cub.2010.06.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Hatton-Ellis E, Simpson P. 2012. The kinase Sgg modulates temporal development of macrochaetes in Drosophila by phosphorylation of Scute and Pannier. Development. 139:325–334. 10.1242/dev.074260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H et al. 2014. Tumor suppressor and deubiquitinase BAP1 promotes DNA double-strand break repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 111:285–290. 10.1073/pnas.1309085110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Ordway AJ, Weber L, Buddika K, Kumar JP. 2018. Polycomb group (PcG) proteins and Pax6 cooperate to inhibit in vivo reprogramming of the developing Drosophila eye. Development. 145:dev160754. 10.1242/dev.160754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Drosophila strains used in this work (listed in Table 1) have been published previously (de Ayala Alonso et al. 2007; Bonnet et al. 2022) or are available from public stock centers. Raw data, normalized data for graphs in Figs. 2 to 6, and P values are listed in Supplementary File 1. The authors affirm that all data necessary for interpreting the data and drawing conclusions are present within the article text, the figures, table, and Supplementary File 1.

Supplemental material available at G3 online.