Abstract

Background:

In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) revolution is rapidly moving from metastatic to early-stage, however, the impact of clinicopathological variables and optimal treatment sequencing remain unclear.

Methods:

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in patients with early-stage NSCLC treated with ICI as single agent or in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy (PCT) were included. Primary outcomes were pathological complete response (pCR), event free survival (EFS) (neoadjuvant/perioperative), and disease-free survival (DFS) (adjuvant). Secondary outcomes were major pathological response (MPR), overall survival (OS), toxicity, surgical outcomes (neoadjuvant/perioperative); OS and toxicity (adjuvant). An additional secondary endpoint was to compare EFS and OS between neoadjuvant and perioperative strategies.

Results:

8 RCTs (2 neoadjuvant, 4 perioperative, 2 adjuvant) (4661 participants) were included. Neoadjuvant/perioperative ICI+PCT significantly improved pCR, EFS, OS, MPR and R0 resection compared to PCT. Adjuvant ICI significantly improved DFS compared to placebo. There was a significant subgroup interaction by PD-L1 status (χ2 = 10.72, P = 0.005), pCR (χ2 = 17.80, P < 0.0001), and stage (χ2 = 4.46, P = 0.003) for EFS. No difference according to PD-L1 status was found for pCR, with 14% of patients having PD-L1 negative tumors still experiencing a pCR. No interaction by PD-L1 status was found for DFS upon adjuvant ICI. Indirect comparison showed no difference in EFS and OS between neoadjuvant and perioperative ICI+PCT.

Conclusions:

PD-L1 status, pCR and stage impact on survival upon neoadjuvant/perioperative ICI. The restriction of neoadjuvant/perioperative ICI to PD-L1 + patients could preclude pCR and long-term benefit in the PD-L1-subgroup. Neoadjuvant and perioperative could be equivalent strategies.

Keywords: Neoadjuvant, Adjuvant, NSCLC, Immune checkpoint inhibitors, Meta-analysis, Early-stage, pCR

1. Background

Neoadjuvant and adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) targeting cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed death-1/ligand-1 (PD-1/PD-L1) are reshaping the treatment scenario in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Indeed, recent scientific evidences [1–3] suggest that neoadjuvant immunotherapy can expand and transcriptionally modify tumor-specific T cell clones to enhance both intratumoral and systemic anti-tumor immunity, improving surgical resectability and decreasing the risk of distant relapse. Several phase I-II non randomized studies have reported that neoadjuvant single agent PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors are associated with major pathological response (MPR) (usually ≤10% residual viable tumor cells) and pathological complete response (pCR) (0% residual viable tumor cells) in surgical samples, however, pCR and MPR rates were extremely variable ranging from 0% [4] to 63% [5] and from 19% [6] to 83% [7], respectively. So far, several randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have explored the role of neoadjuvant PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy (PCT) [8–13] in stage IB-IIIB resectable NSCLC. In addition, a prolongation of event-free survival (EFS) initially reported in one study [8] led to the first Food and Drug Association (FDA) approval of a neoadjuvant ICI regimen (nivolumab in combination with PCT) for resectable NSCLC. Recently the European Medical Agency (EMA) restricted this approval to patients with NSCLC and PD-L1 expression on tumor cells (TPS) ≥ 1% because of a significant EFS improvement observed mainly in the PD-L1 positive population. However, PD-L1 was not clearly associated with pCR upon neoadjuvant/perioperative ICI+PCT, suggesting that pCR and long-term survival benefit could occur also in PD-L1 negative patients. Furthermore, neoadjuvant and perioperative strategies have not been compared in a randomized fashion and whether an additional year of post-operative ICI is truly necessary and for which patients are current unanswered questions.

So far, two RCTs have compared adjuvant ICI to placebo after surgical resection in patients with stage IB-IIIA NSCLC [14,15]. Both studies demonstrated a prolongation of disease-free survival (DFS); overall survival (OS) was not significantly improved, but data are still immature. Conflicting results emerged from these RCTs about the role of PD-L1 TPS in predicting survival improvement from adjuvant ICI.

To define the impact of clinical and pathological factors on ICI benefit in early-stage NSCLC and to compare perioperative and neoadjuvant strategies, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs with ICI as single agents or in combination with PCT.

2. Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Metanalysis (PRISMA) guidelines [16]. The study protocol was registered to the PROSPERO online platform (ID CRD42023432088).

2.1. Types of included studies and outcome measures

Inclusion criteria were: phase III or phase I/II RCTs conducted in patients with non-metastatic NSCLC, administration of ICI (PD-1/PD-L1 or CTLA-4 inhibitors) as preoperative (neoadjuvant), perioperative (preoperative followed by postoperative) or postoperative (adjuvant) treatments, use of ICI as single agents or in combination with PCT. Exclusion criteria were combination of multiple ICI, or combination of ICI with experimental immunotherapies or radiotherapy.

Primary outcomes were: pCR and EFS or progression free survival (PFS) for neoadjuvant/perioperative RCTs and DFS for adjuvant RCTs. Secondary outcomes were: MPR, OS, grade 3–5 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs), surgical outcomes (percentage of complete R0 resection and of not-resected patients) for neoadjuvant and perioperative RCTs, and OS and grade 3–5 TRAEs for adjuvant RCTs. An additional secondary endpoint was to compare EFS and OS between neoadjuvant and perioperative strategies.

2.2. Review methodology: screening, data extraction, risk of bias

A systematic literature search was performed using Thesaurus terms in MedLine/Pubmed, Cochrane Library and Embase electronic databases from inception to August 10th 2023 (eTable 1) without language restriction. Meeting abstracts or presentations from conference proceedings (i.e., ASCO, ESMO, IASLC) were also included. Two authors (A. N., F.S.) independently performed records screening by titles and abstracts, retrieved and evaluated full-texts for inclusion and extracted data. Disagreements resolution and independent verification of extracted data were performed by a third author (G.V.). Study characteristics (first author, publication year, type of therapy), baseline clinicopathological variables (PD-L1 expression status, stage, age, sex, histology, smoking habit), and endpoint results (survival outcomes, pCR, MPR, surgical outcomes, grade 3–5 TRAEs) were extracted. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool 1.0 [17] by two authors (A. N., R.F.) and disagreements were resolved by a third author (G.V.). Funnel plots to assess publication bias were reported if there were at least 10 included studies.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Dichotomous outcomes (i.e.; pCR, MPR, EFS/PFS, DFS and OS rates at 1 year after randomization, percentage of R0 resection, percentage of not-resected patients, TRAEs) were measured by risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval. Time to event outcomes (i.e.; EFS/PFS, DFS, OS) were measured by hazard ratio (HR) and their 95% confidence interval.

A random effect model was performed for all analyses due to potential heterogeneity. The indirect comparisons between neoadjuvant and perioperative strategies was performed using the method previously described by Bucher [18] and Glenny [19].

To measure statistical heterogeneity among studies, the Cochrane Q-test was performed with a significant threshold of alpha = 0.1, and inconsistency among studies was quantified by the I-squared statistic [17] with I-square > 70% judged as significant heterogeneity.

Results were depicted as conventional meta-analysis forest plots by using RevMan 5.4 software [20].

2.4. Subgroup analyses

Prespecified subgroups analyses were performed to assess the potential association of some clinical and biological factors with primary outcomes. Subgroups were defined according to PD-L1 TPS status, pCR (for neoadjuvant/perioperative RCTs), stage, histology, smoking habit, age, and sex.

2.5. Grading of evidence

We used the five GRADE domains (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to rate the certainty of evidence for primary and secondary outcomes as “high”, “moderate”, “low” or “very low”, according to GRADE approach [21]. “Summary of Findings” table summarized the amount and the certainty of available evidence.

3. Results

3.1. Literature search results and characteristics of included RCTs

Literature research identified 5056 records up to August 10th 2023. Eight RCTs (2 neoadjuvant, 4 perioperative and 2 adjuvant) involving 4661 subjects (452 in neoadjuvant RCTs, 2027 in perioperative RCTs and 2182 in adjuvant RCTs) were included (eFigure 1). Main characteristics, selected outcomes and median follow-up of included RCTs are reported in Table 1 and eFigure 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Neoadjuvant/perioperative trials | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Author, year | Phase | Trial | Median Follow-up at last update (range, if specified) | Stage | Experimental arm | Control arm | Primary endpoint (s) | pCR (%) Exp vs Ctrl arm |

EFS HR (95% CI) Exp vs Ctrl arm |

|

| |||||||||

| Forde, 2022 | III | CheckMate 816 | 41.4 mo | IB-IIIA* | Neoadj: CT + nivo x3 | Neoadj: PCT x3 | pCR, EFS | 24.0 vs 2.2 | 0.63 (97.38% CI, 0.43–0.91) |

| Lei, 2023 | II | TD-FOREKNOW | 14.1 mo (9.2 – 20.9) | IIIA-IIIB [T3N2M0]* * | Neoadj: CT + cam x3 | Neoadj: PCT x3 | pCR | 32.6 vs 8.9 | 0.52 (0.21–1.29) |

| Heymach, 2023 | III | AEGEAN | 11.7 mo | IIA–IIIB[N2]* * | Preop: CT + durva x4 Postop: durva x12 |

Preop: PCT + pbo x4 Postop: pbo x12 |

pCR, EFS | 17.2 vs 4.3 | 0.59 (0.35–1.00) |

| Lu, 2023 | III | NEOTORCH | 18.3 mo | II-IIIA-IIIB* * | Preop: CT + tori x3 Postop: tori x13 |

Preop: PCT + pbo x3 Postop: pbo x13 |

EFS, MPR | 24.8 vs 1 | 0.40 (0.277–0.565) |

| Provencio, 2023 | II | NADIM II | 26.1 mo (17.4 – 30.9) | IIIA-IIIB* * | Preop: CT + nivo x3 Postop: nivo x6 |

Neoadj: PCT x3 | pCR | 37.0 vs 7.0 | PFS HR 0.47 (0.25 – 0.88) |

| Wakelee, 2023 | III | Keynote 671 | 25.2 mo (7.5 – 50.6) | IIA-IIIB[N2]* * | Preop: CT + pembro x4 Postop: pembro x13 |

Preop: PCT + pbo x4 Postop: pbo x13 |

EFS, OS | 30.2 vs 11.0 | 0.58 (0.46–0.72) |

|

| |||||||||

| Adjuvant trials | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Author | Phase | Trial | Median Follow-up at last update (range, if specified) | Stage | Experimental arm | Control arm | Primary endpoint(s) | DSF HR (95% CI) Exp vs Ctrl arm |

OS HR (95% CI) Exp vs Ctrl arm |

|

| |||||||||

| Felip, 2021 | III | IMpower010 | 45.3 mo | IB (T ≥ 4 cm) -IIIA* | Adj: atezo x16 after adjuvant CT | Adj: bsc after adjuvant PCT | DFS | 0.81 (0.67–0.99) † | 0.99 (0.78–1.28) † |

| O’Brien, 2022 | III | Keynote 091 | 35.6 mo (27.1 – 45.5) | IB (T ≥ 4 cm) -IIIA* | Adj: pembro x18 | Adj: pbo x18 | DFS | 0.76 (0.63–0.91) | 0.87 (0.67–1.15) |

AJCC 7th ed.

8th † in the intention to treat population

Abbreviations: Adj: adjuvant. Atezo: atezolizumab. Bsc: best supportive care. Cam: camrelizumab. CI: confidence interval. DFS: disease free survival. Durva: durvalumab. EFS: event free survival. Exp: experimental. Ctrl: control HR: hazard ratio. neoadj: neoadjuvant. Nivo: nivolumab. pbo: placebo. pCR: pathological complete response. mo: months. MPR: major pathological response. OS: overall survival. PCT: platinum-based chemotherapy. Pembro: pembrolizumab. Preop: preoperative. Postop: postoperative. Tori: toripalimab.

Risk of bias was assessed using available information in full articles or in abstracts (eFigure 3). Two studies were judged at high risk of performance and detection bias due to the open label design affecting the primary endpoint (eTable 2). eFigure 4 shows risk of bias assessment for each included study. eTable 3 reports certainty of evidence according to GRADE which ranged from moderate to high and from low to high for primary and secondary outcomes, respectively. As fewer than ten studies were included in the meta-analysis, funnel plot is not reported.

3.2. Primary outcomes

3.2.1. Neoadjuvant and perioperative RCTs

In 6 neoadjuvant/perioperative RCTs, pooled pCR and EFS/PFS rates at 1 year after randomization with ICI+PCT compared to PCT were 20.8% (95% CI: 19%; 23%) versus (vs) 3.6% (95% CI: 3%; 5%) and 76.9% (95% CI: 74%; 80%) vs 61.8% (95% CI: 59%; 65%), respectively (Fig. 1A–B). A statistically significant improvement in pCR rate (RR: 5.66, 95% CI 3.48–9.18, I2: 47%, 6 RCTs, 2473 participants), EFS/PFS (HR: 0.58, 95% CI 0.50–0.69, I2: 21%, 6 RCTs, 2473 participants) (Figure 2A–B), and a significant reduction in the risk of progression/death at 1-year (RR: 0.53, 95% CI 0.39–0.71, I2: 75%, 6 RCTs, 2454 participants) (eFigure 5A) were observed with ICI+PCT compared to PCT.

Fig. 1.

pCR, MPR and surgical outcomes (R0 resection and not resected patients) (neoadjuvant) (A), 1-year EFS/PFS and OS rates (neoadjuvant) (B), 1-year DFS and OS rates (adjuvant) (C), grade 3–5 treatment related adverse events (neoadjuvant and adjuvant) (D).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots for pCR (A), EFS/PFS in neoadjuvant RCTs (B) and for DFS in adjuvant RCTs (C).

3.2.2. Adjuvant RCTs

In 2 adjuvant RCTs, pooled DFS rates at 1 year after randomization with ICI compared to placebo were 76.3% (95% CI: 79%; 83%) vs 71.3% (95% CI: 73%; 77%) (Fig. 1C). A statistically significant improvement in DFS (HR: 0.78, 95% CI 0.69–0.90, I2: 0%, 2 RCTs, 2182 participants) (Figure 2C) and DFS at 1-year (RR: 0.74, 95% CI 0.63–0.86, I2: 0%, 2 RCTs, 2183 participants) (eFigure 5B) was observed with ICI compared to placebo.

3.3. Subgroups analyses

3.3.1. Tumor PD-L1 expression level

In the neoadjuvant/perioperative setting, although the rate of pCR was doubled in PD-L1 positive compared to PD-L1 negative patients (28% vs 14%) (Fig. 3A), no subgroup interaction according to PD-L1 status was found, neither for negative vs intermediate vs high TPS (χ2 = 0.92, P = 0.63, I2 = 0%, 3 RCTs, 1088 participants) (Fig. 3A) nor for negative vs positive TPS (χ2 = 0.26, P = 0.61, I2 = 0%, 3 RCTs, 1115 participants) (eFigure 6A). However, in the EFS/PFS analysis, test for subgroup interaction was statistically significant according to PD-L1 status, both for negative vs intermediate vs high TPS (χ2 = 10.72, P = 0.005, I2 = 81.3%, 4 RCTs, 1610 participants) (Fig. 3B) and for negative vs positive TPS (χ2 = 14.06, P = 0.0002, I2 = 92.9%, 2 RCTs, 1073 participants) (eFigure 6B). In particular, 66% of patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥ 1% were EFS free at 1-year upon ICI+PCT (versus 55% PD-L1-) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

pCR (A), EFS/PFS (B) and DFS (C) according to PD-L1 TPS, EFS/PFS according to pCR.

In the adjuvant setting, there was no subgroup interaction according to PD-L1 status (negative vs intermediate vs high) for DFS (χ2 = 1.55, P = 0.46, I2 = 0%, 2 RCTs, 1653 participants) (Fig. 3C).

3.3.2. pCR

In the EFS/PFS analysis, test for subgroup interaction according to pCR (yes vs no) was statistically significant (χ2 =17.80, P < 0.0001, I2 = 94.4%, 4 RCTs, 1817 participants). Of note, 99% of patients with pCR upon neoadjuvant ICI+PCT were event-free at 1-year (compared to 55% of pCR-patients) (Fig. 3D).

3.3.3. Other subgroups

In the neoadjuvant/perioperative RCTs, there was a significant subgroup interaction according to stage (IB-II vs III) for EFS/PFS (χ2 = 4.46, P = 0.003, I2 = 77.6%, 6 RCTs, 1941 participants) that did not remain significant after splitting stage III in IIIA and IIIB (χ2 = 2.98, P = 0.23, I2 = 32.8%, 3 RCTs, 1892 participants) (eFigure 7 C–D). No significant subgroup interaction was observed according to stage for pCR (eFigure 7 A–B).

Test for subgroup interaction according to histology (eFigure 8), smoking habit (eFigure 9), age (eFigure 10), and sex (eFigure 11) did not show any significant difference in pCR or EFS/PFS between neoadjuvant/perioperative ICI+PCT vs PCT neither in DFS between adjuvant ICI compared to placebo.

3.4. Secondary outcomes

3.4.1. Neoadjuvant and perioperative RCTs

In 6 neoadjuvant/perioperative RCTs, pooled MPR and OS rates at 1 year after randomization with ICI+PCT compared to PCT were 37.3% (95% CI: 35%; 39%) vs 10.8% (95% CI: 9%; 13%) and 90.1% (95% CI: 89%; 93%) vs 89.0% (95% CI: 87%; 91%), respectively (Fig. 1A–B). Similar proportion of patients did not undergo surgery, 17% (95% CI: 14%; 20%) vs 21% (95% CI: 18%; 24%). R0 resection was slightly higher with ICI+PCT compared to PCT, 75% (95% CI: 73%; 77%) vs 67% (95% CI: 65%; 69%) (Fig. 1A). Grade-3–5 TRAEs were 41.4% (95% CI: 42%; 48%) vs 37.7% (95% CI: 38%; 44%) with ICI+PCT vs PCT (Fig. 1D). A statistically significant increase in OS (HR: 0.66, 95% CI 0.53–0.82, I2: 0%, 4 RCTs, 1817 participants) (eFigure 12), in MPR (HR: 3.58, 95% CI 2.73–4.71, I2: 50%, 6 RCTs, 2473 participants) (eFigure 13), and R0 resection rate (RR: 1.05, 95% CI 1.02–1.08, I2: 0%, 6 RCTs, 1972 participants) (eFigure 14) was observed with ICI+PCT vs PCT, while no significant differences for the other secondary endpoints (rate of not-resected patients, grade 3–5 TRAEs) (eFigure 14B–15) were reported.

3.5. Adjuvant RCTs

In 2 adjuvant RCTs, pooled OS rates at 1 year after randomization with ICI compared to placebo were 96% (95% CI: 94%; 96%) vs 95% (95% CI: 94%; 96%) (Fig. 1C). No statistically significant differences in OS (eFigure 12B) and in grade 3–5 TRAEs (eFigure 15B) were observed with ICI compared to placebo.

3.5.1. Indirect comparison neoadjuvant vs perioperative ICI+PCT

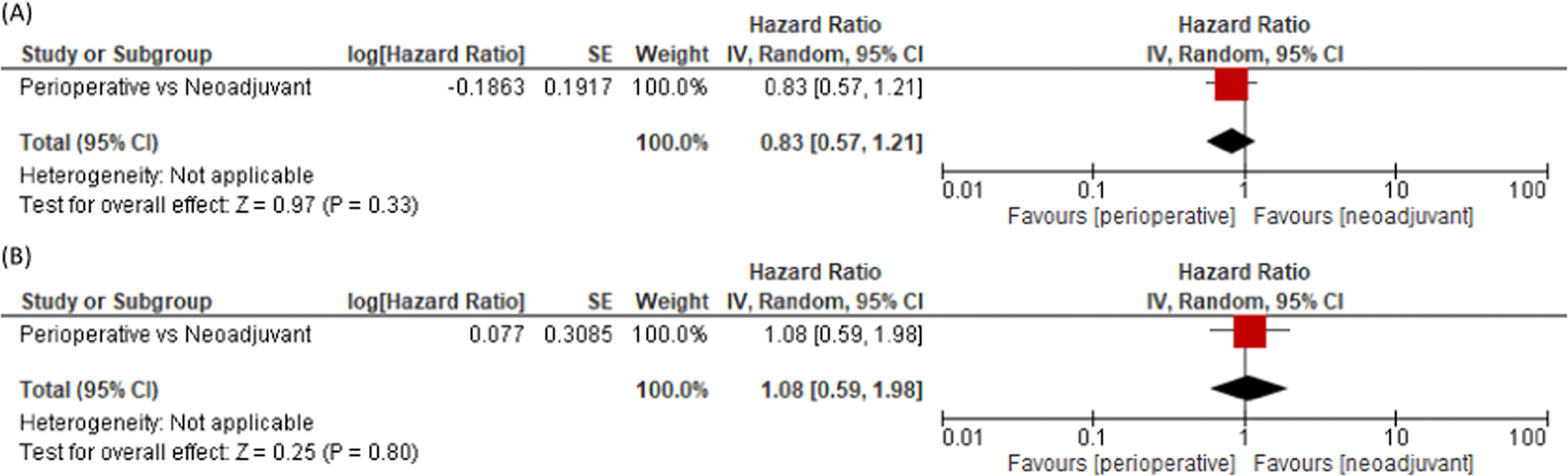

Perioperative ICI+PCT did not significantly improve neither EFS/PFS (RR: 0.83, 95% CI 0.57–1.21) (Figure 4A) nor OS (RR: 1.08, 95% CI 0.59–1.98) (Figure 4B) compared to neoadjuvant ICI+PCT.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of EFS/PFS (A) and OS (B) between perioperative and neoadjuvant strategies.

4. Discussion

The recent paradigm shift brought by the use of ICI in early-stage NSCLC has raised several burning questions regarding the predictive value of PD-L1 for neoadjuvant/adjuvant ICI, the choice between neoadjuvant and perioperative regimens, the role of pCR in identifying patients for whom additional adjuvant ICI could be spared, the value of neoadjuvant/perioperative ICI strategies in locally advanced high-volume tumors (i.e.; stage IIIB) compared to radical chemoradiotherapy followed by ICI.

The present meta-analysis shows that tumor PD-L1 status is a good predictive biomarker for EFS upon neoadjuvant/perioperative ICI+PCT with ~65% of patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥ 1% being event-free at 1 year, however no subgroup interaction according to PD-L1 was found for pCR. This suggests that ICI+PCT increase pCR rate regardless of PD-L1 value and approximately 14% of PD-L1 negative patients can still experience a pCR. Similarly, a low negative predictive value of PD-L1 for response to ICI has been previously described in the metastatic setting, as reported by Checkmate 017 where 17% of patients with negative PD-L1 had a tumor reduction upon ICI [22]. A recent meta-analysis has shown a significant correlation between PD-L1 TPS ≥ 1% and pCR, however, compared to the present work, it pooled data from a different trial population including retrospective or single arm studies [23]. In our meta-analysis, pooled pCR from 6 RCTs was strongly associated with EFS. Although EFS data from RCTs are not stratified for both pCR and PD-L1 status, the present meta-analysis suggests that pCR could be a more reliable biomarker of survival benefit compared to PD-L1, with 99% of pCR+ patients being event-free at 1 year. Considering that also PD-L1 negative patients can still experience pCR, the restriction of ICI+PCT to PD-L1 positive status could preclude pCR and long-term survival in up to 14% of PD-L1 negative patients.

Atezolizumab has been approved by EMA in PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50% on the basis of an OS benefit in this subgroup [24], however, in the present work, PD-L1 expression did not significantly correlate with DFS mainly due to the long survival of patients with PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50% enrolled in the placebo arm of PEARLS [25]. Considering that PD-L1 expression is not a prognostic factor in resected NSCLC [26], the reasons underlying the conflicting results emerged from Impower 010 and PEARLS trials and the exact role of PD-L1 status in the adjuvant setting remain unraveled questions.

Although head-to-head comparisons between the two treatment approaches are missing, the present meta-analysis shows lack of difference in survival between pure neoadjuvant and perioperative treatments, suggesting that an additional year of adjuvant ICI should be tailored according to individual patients’ risk of relapse. In particular, the obtainment of pCR or the clearance of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) could be promising biomarkers for future escalation/de-escalation trials with neoadjuvant/perioperative ICI [27,28] avoiding useless additional toxicities and costs.

Finally, we showed a significant subgroup interaction according to stage, with improved EFS in stage III NSCLC. Considering that in 3 out of 6 RCTs [9,12,13], up to approximately 25% of patients were stage IIIB according to the 8th TNM edition (i.e., T3N2 or T4N2), it is plausible to speculate that some bulky-like stage III NSCLC, although still deemed resectable, could benefit more from a PACIFIC strategy (chemoradiation and ICI maintenance) [29] rather than from neoadjuvant ICI+PCT. However, in the present meta-analysis, there was no difference in terms of EFS when stage IIIB were separated from IIIA, suggesting that surgery could be offered to stage IIIB patients properly selected according to resectability criteria and multidisciplinary board evaluation. In line with these results, an increase in complete R0 resection with neoadjuvant ICI+PCT challenges the adoption of such strategy also in borderline resectable tumors where the baseline probability of R0 resection is quite low.

To our knowledge, the present work is the first meta-analyses including only RCTs that dissect the impact of multiple clinicopathological features on neoadjuvant, perioperative and adjuvant ICI, specifically providing insights on the predictive role of PD-L1 status and pCR for survival in early-stage NSCLC. In addition, this work is the first one that indirectly compares the neoadjuvant and perioperative treatment strategies, suggesting a potential equivalence between the two approaches.

This systematic review and meta-analysis has some limitations. In fact, it relies on published RCTs and not on individual patients’ data and, for this reason, the granularity of its results is somehow limited. Firstly, pooling RCTs using different treatments (i.e.; neoadjuvant or perioperative) and including some exploratory or small subgroups caused a moderate to high heterogeneity that could affect the generalizability of the results. In addition, the median follow up of neoadjuvant/perioperative RCTs included in this metanalysis ranged from 11.7 to 41.4, with Keynote 671 having the longest follow-up range (min 7.5; max 50.6). This timeframe was considerably shorter compared to 72 months (min 50.4, max 98.4 months) of median follow up reported in a previous metanalysis of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in early stage NSCLC [30]. Similarly, the median follow up of RCTs with adjuvant ICI ranged from 35.6 to 45.3 months with Keynote 091 having the longest follow-up range (min 27.1; max 45.5), a time interval which was anyway shorter compared to the 62.4 months of median follow up (min 56.4 max 70.8) reported in the LACE meta-analysis including RCTs with adjuvant chemotherapy [31]. However, most of disease relapses for patients with NSCLC occur in the first 2 years after surgery, as recently reported by the IFCT-0302 trial which showed that 66% of disease relapses were detected in the first 2 years for resected NSCLC patients (approximately 50% of them received pre or postoperative treatments) [32]. Therefore, the reliability of the survival data presented in this manuscript could be only relatively affected by the 2 years median follow-up time of most of the included RCTs. Finally, the indirect comparison between the neoadjuvant and perioperative strategy was adopted as a surrogate outcome and cannot replace head-to-head comparisons between treatment regimens.

5. Conclusion

Neoadjuvant/perioperative and adjuvant ICI significantly improve outcomes in early-stage NSCLC. PD-L1 status, pCR and stage influence the benefit from neoadjuvant/perioperative ICI. In particular, the restriction of neoadjuvant/perioperative ICI to PD-L1 + patients could preclude pCR and long-term benefit in the PD-L1-subgroup. Pure neoadjuvant and perioperative ICI+PCT strategies appeared to be equivalent in terms of survival outcomes, suggesting that future studies should adopt pCR or other biomarkers (i.e.; ctDNA) to tailor escalating or de-escalating treatment approaches according to individual risk of relapse.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2023.113404.

Acknowledgements

Veronica Andrea Fittipaldo (Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS, Milan) contributed to bibliographic search.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: T.C. reports (over the past 36 months) speaker fees/honoraria from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC), Mark Foundation for Cancer Research, Bristol Myers Squibb, Roche, Medscape, IDEOlogy Health, Physicians’ Education Resource® LLC (PER®), OncLive, PeerView and Clinical Care Options (CCO); advisory role/consulting fees from MedImmune/AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck & Co., Genentech, Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer Inc. and Regeneron; institutional research funding from MedImmune/AstraZeneca and Bristol Myers Squibb; and travel, food and/or beverage expenses from Physicians’ Education Resource® LLC (PER®), Dava Oncology, SITC, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, IDEOlogy Health, OncLive, AstraZeneca and Bristol Myers Squibb.M.C.G. reports AstraZeneca, Abion, MSD International GmbH, Bayer, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim Italia S.p.A, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Incyte, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Takeda, Seattle Genetics, Mirati, Daiichi Sankyo, Regeneron, Merck, Blueprint, Jansenn, Sanofi, AbbVie, BeiGenius, Oncohost, Medscape G.V. is consultant for Ab Medica, Roche, AstraZeneca, MSD, outside the submitted work R.F. reports advisory board for MSD and advisory board for BeiGene M.R. declares grants or contracts from AstraZeneca and participation on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board for Eli Lilly, PANAVANCE, Celgene, AstraZeneca, Viatris, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Servier, SOTIO, and Baxter.

All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Dr. Nuccio, Dr. Viscardi and Dr. Ferrara take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: Ferrara, Nuccio, Viscardi, Cinquini. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Ferrara, Nuccio, Viscardi, Cinquini, Salomone. Drafting of the manuscript: Ferrara, Viscardi, Nuccio. Critical revision of the manuscript: Ferrara, Nuccio, Viscardi, Cascone, Garassino. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Nuccio, Viscardi, Salomone, Servetto, Venanzi, Riva, Oresti, Ogliari, Viganò, Bulotta, Cameron, Esposito, Hines, Bianco, Reni, Cascone, Garassino, Torri, Veronesi, Cinquini, Ferrara. Statistical analysis: Cinquini, Torri. Supervision: Ferrara, Viscardi, Cinquini.

References

- [1].Mountzios G, Remon J, Hendriks LEL, García-Campelo R, Rolfo C, Van Schil P, et al. Immune-checkpoint inhibition for resectable non-small-cell lung cancer — opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2023;20:664–77. 10.1038/s41571-023-00794-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rainey MA, Allen CT, Craveiro M. Egress of resident memory T cells from tissue with neoadjuvant immunotherapy: Implications for systemic anti-tumor immunity. Oral Oncol 2023;146:106570. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2023.106570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Topalian SL, Forde PM, Emens LA, Yarchoan M, Smith KN, Pardoll DM. Neoadjuvant immune checkpoint blockade: a window of opportunity to advance cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 2023;41:1551–66. 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Besse B, Adam J, Cozic N, Chaput-Gras N, Planchard D, Mezquita L, et al. 1215O - SC Neoadjuvant atezolizumab (A) for resectable non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): results from the phase II PRINCEPS trial. Ann Oncol 2020;31:S794–5. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.1417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Shu CA, Gainor JF, Awad MM, Chiuzan C, Grigg CM, Pabani A, et al. Neoadjuvant atezolizumab and chemotherapy in patients with resectable non-small-cell lung cancer: an open-label, multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:786–95. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wislez M, Mazieres J, Lavole A, Zalcman G, Carre O, Egenod T, et al. Neoadjuvant durvalumab for resectable non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): results from a multicenter study (IFCT-1601 IONESCO). J Immunother Cancer 2022;10:e005636. 10.1136/jitc-2022-005636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Provencio M, Nadal E, Insa A, García-Campelo MR, Casal-Rubio J, Dómine M, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and nivolumab in resectable non-small-cell lung cancer (NADIM): an open-label, multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:1413–22. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30453-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, Provencio M, Mitsudomi T, Awad MM, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2022;386:1973–85. 10.1056/NEJMoa2202170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Heymach JV, Harpole D, Mitsudomi T, Taube JM, Galffy G, Hochmair M, et al. Abstract CT005: AEGEAN: a phase 3 trial of neoadjuvant durvalumab + chemotherapy followed by adjuvant durvalumab in patients with resectable NSCLC. Cancer Res 2023;83:CT005. 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2023-CT005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lei J, Zhao J, Yan X, Gong L, Lei G, Jiang T. 56O A randomized, controlled, multicenter phase II trial of camrelizumab combined with albumin-bound paclitaxel and cisplatin as neoadjuvant treatment in resectable stage IIIA and IIIB (T3N2) non-small-cell lung cancer. Immuno-Oncol Technol 2022;16. 10.1016/j.iotech.2022.100161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Provencio M, Nadal E, González-Larriba JL, Martínez-Martí A, Bernabé R, Bosch-Barrera J, et al. Perioperative nivolumab and chemotherapy in stage III non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2023. 10.1056/NEJMoa2215530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wakelee H, Liberman M, Kato T, Tsuboi M, Lee S-H, Gao S, et al. Perioperative pembrolizumab for early-stage non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2023. 10.1056/NEJMoa2302983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lu S, Wu L, Zhang W, Zhang P, Wang W, Fang W, et al. Perioperative toripalimab + platinum-doublet chemotherapy vs chemotherapy in resectable stage II/III non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Interim event-free survival (EFS) analysis of the phase III Neotorch study. 425126–425126 JCO 2023;41. 10.1200/JCO.2023.41.36_suppl.425126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, Csőszi T, Vynnychenko I, Goloborodko O, et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB–IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021;398:1344–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].O’Brien M, Paz-Ares L, Marreaud S, Dafni U, Oselin K, Havel L, et al. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy for completely resected stage IB–IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091): an interim analysis of a randomised, triple-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2022;23:1274–86. 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00518-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;10:ED000142. 10.1002/14651858.ED000142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, Walter SD. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:683–91. 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Glenny AM, Altman DG, Song F, Sakarovitch C, Deeks JJ, D’Amico R, et al. Indirect comparisons of competing interventions. Health Technol Assess 2005;9:1–134. 10.3310/hta9260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Manager Review (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.4. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020. n.d. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, Crinò L, Eberhardt WEE, Poddubskaya E, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;373:123–35. 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wu Y, Verma V, Gay CM, Chen Y, Liang F, Lin Q, et al. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy for advanced, resectable non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer 2023;129:1969–85. 10.1002/cncr.34755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, Vallieres E, Martínez-Marti A, Rittmeyer A, et al. Overall survival with adjuvant atezolizumab after chemotherapy in resected stage II-IIIA non-small cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Ann Oncol 2023;0. 10.1016/j.annonc.2023.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Peters S, Besse B, Marreaud S, Dafni U, Oselin K, Havel L, et al. 930MO PD-L1 expression and outcomes of pembrolizumab and placebo in completely resected stage IB-IIIA NSCLC: subgroup analysis of PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091. Ann Oncol 2022;33:S971–2. 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.07.1056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tsao M-S, Teuff GL, Shepherd FA, Landais C, Hainaut P, Filipits M, et al. PD-L1 protein expression assessed by immunohistochemistry is neither prognostic nor predictive of benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy in resected non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2017;28:882–9. 10.1093/annonc/mdx003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zhang Q, Luo J, Wu S, Si H, Gao C, Xu W, et al. Prognostic and predictive impact of circulating tumor DNA in patients with advanced cancers treated with immune checkpoint blockade. Cancer Discov 2020;10:1842–53. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bestvina CM, Garassino MC, Neal JW, Wakelee HA, Diehn M, Vokes EE. Early-stage lung cancer: using circulating tumor DNA to get personal. JCO 2023:JCO.23.00258. 10.1200/JCO.23.00258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Faivre-Finn C, Vicente D, Kurata T, Planchard D, Paz-Ares L, Vansteenkiste JF, et al. Four-year survival with durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III NSCLC-an update from the PACIFIC trial. J Thorac Oncol 2021;16:860–7. 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Preoperative chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2014;383:1561–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62159-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Pignon J-P, Tribodet H, Scagliotti GV, Douillard J-Y, Shepherd FA, Stephens RJ, et al. Lung adjuvant cisplatin evaluation: a pooled analysis by the LACE collaborative group. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3552–9. 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Westeel V, Foucher P, Scherpereel A, Domas J, Girard P, Trédaniel J, et al. Chest CT scan plus x-ray versus chest x-ray for the follow-up of completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer (IFCT-0302): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2022;23:1180–8. 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00451-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.