Abstract

The activities of mefloquine (MFL) and related compounds against previously characterized Streptococcus pneumoniae strains carrying defined amino acid substitutions in the c subunit of the F0F1 H+-ATPase were studied. In addition, a series of MFL-resistant (Mflr) strains were isolated and characterized. A good correlation was observed between inhibition of growth and inhibition of the membrane-associated F0F1 H+-ATPase activity. MFL was about 10-fold more active than optochin and about 200-fold more active than quinine in inhibiting both the growth and the ATPase activities of laboratory pneumococcal strain R6. Mutant strains were inhibited by the different compounds to different degrees, depending on their specific mutations in the c subunit. The resistant strains studied had point mutations that changed amino acid residues in either the c subunit or the a subunit of the F0 complex. Changes in the c subunit were located in one of the two transmembrane α helices: residues M13, G14, G20, M23, and N24 of helix 1 and residues M44, G47, V48, A49, and V57 of helix 2. Changes in the a subunit were also found in either of the transmembrane α helices, helix 5 or 6: residue L186 of helix 5 and residues W206, F209, and S214 of helix 6. These results suggest that the transmembrane helices of the c and a subunits interact and that the mutated residues are important for the structure of the F0 complex and proton translocation.

The prevalence of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains resistant to common antimicrobial agents (10, 26) and the emergence of resistance to new drugs like the fluoroquinolones (4, 20) have highlighted the need for novel antimicrobial agents directed at new targets. The membrane-associated F0F1 H+-ATPase could be such a target, given that the unique sensitivity of S. pneumoniae to the amino alcohol antimalarial agents optochin (OPT) and quinine (QIN) resides in the characteristics of its F0 complex (6, 24). The H+-ATPase could be essential for the viability of the pneumococcus, as demonstrated in Lactococcus lactis, a genetically related species (17). The primary role of this enzyme in S. pneumoniae is to create a proton gradient with the energy provided by ATP hydrolysis and to maintain the intracellular pH via proton extrusion (21), as in other related bacteria (7, 14). However, in bacteria with a respiratory chain such as Escherichia coli, the primary role of this enzyme is to synthesize ATP from the proton gradient of the respiratory chain. The bacterial F0F1 ATPases consist of cytoplasmic sector F1 (with α, β, δ, γ, and ξ subunits), which contains the catalytic sites for ATP hydrolysis, and cytoplasmic membrane sector F0 (with a, c, and b subunits), which forms the proton channel. Proton transport through F0 drives the release of ATP on F1 by long-range conformational changes. The protonation state of an acidic residue of the c subunit produces conformational changes that drive the rotation of an oligomeric ring of these subunits. This rotation, in turn, causes the rotation of the attached γ and ξ subunits, producing conformational changes in the β subunits (28, 33) that result in ATP synthesis (1). Conversely, hydrolysis of ATP in F1 generates rotation of γ and ξ, resulting in the pumping of protons back across the membrane through F0. In S. pneumoniae (21), as well as in other related bacteria (2, 15-18), the activity of the F0F1 ATPase has been seen to increase as the pH of the growth medium decreases. The regulation of this pH-inducible phenotype occurs in S. pneumoniae at the level of transcription initiation (21).

Although OPT was used at the beginning of the 20th century for the treatment of pneumococcal infections (23), nowadays its use is restricted to diagnostic purposes due to its high toxicity. However, new related, less toxic compounds have been synthesized (19). Given the special characteristics of the pneumococcal F0F1 ATPase and its role in the maintenance of intracellular pH, this enzyme could be considered a target for the design of new antibacterial agents. Moreover, the pneumococcus could also be considered a model system for the study of the putative antimalarial activities of new compounds (24).

In the present study, we describe the molecular basis of the antipneumococcal behavior of mefloquine (MFL) and related compounds. MFL has been found to have bactericidal activities against gram-positive bacteria, including staphylococci, pneumococci, and enterococci, but showed poor activities against gram-negative enteric bacteria and yeasts (19). However, the MFL-related compounds used in this work showed enhanced activities against staphylococci, enterococci, and yeasts, having activities similar to those of amphotericin B against Candida spp. and Cryptococcus neoformans (19). The activities of these compounds on the growth and membrane-associated ATPase activities of S. pneumoniae strains with defined mutations in the c and a subunits of the F0 complex of the F0F1 ATPase have been studied. In addition, MFL-resistant (Mflr) strains have been isolated and characterized.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth, and transformation of bacteria.

The following strains of S. pneumoniae were used in this study: common laboratory strain R6; OPT- and QIN-resistant R6 derivatives MJ11 and MJ2 (6) and MJQ3 and MJQ4 (24); and strains ATCC 6303 and ATCC 49619, which were used as quality controls for antimalarials (18). Unless stated otherwise, strain R6 was grown in liquid C medium with added 0.08% yeast extract, and transformation was carried out as described by Tomasz (34). Cultures containing 9 × 106 CFU per ml were treated with DNA at 0.1 μg/ml for 40 min at 30°C and then at 37°C for 90 min before they were plated onto plates with medium containing 0.3 μg of MFL per ml.

Susceptibility tests.

MICs were determined by the microdilution method with cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with 2.5% lysed horse blood recommended by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (25). The inoculum was prepared by suspension of several colonies from an overnight blood agar culture in Mueller-Hinton broth and adjusting the turbidity to that of a 0.5 McFarland standard (ca. 108 CFU/ml). The suspension was further diluted to provide a final bacterial concentration of 105 CFU/ml in each well of the microdilution trays. The plates were covered with plastic wrap and incubated in the ambient atmosphere at 37°C for 20 to 24 h. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of drug that inhibited visible growth. S. pneumoniae strains ATCC 49619 and ATCC 6303 were used for quality control.

PCR amplification and DNA sequence determination.

S. pneumoniae chromosomal DNA was obtained as described previously (6). PCR amplifications were performed with 1 U of Thermus thermophilus thermostable DNA polymerase (Biotools), 1 μg of chromosomal DNA, each of the synthetic oligonucleotide primers at a concentration of 0.4 μM, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 0.2 mM, and 2 mM MgCl2 in a final volume of 50 μl. To amplify the atpC and atpA genes, oligonucleotides atporf1 (5′-ggtcggaaTTCTGGATGGCTAACTTGAACTTG-3′; corresponding to nucleotides −143 to −120 upstream of atpC) and atpB56 (5′-GACGGGCTTCTTCAGCTCTGTC-3′; the complementary strand of the primer coding for the DRAEEAR amino acid sequence of subunit b), respectively, were used. The 5′ end of atporf1 contained an additional sequence (lowercase) that included an EcoRI restriction site, which is underlined in the atporf1 oligonucleotide sequence above. Amplification was achieved with an initial cycle of 1 min of denaturation at 94°C and 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 90 s at 55°C, and 75 s of a polymerase extension step at 72°C, with a final 8-min extension step at 72°C and slow cooling at 4°C. The PCR products used in control transformation experiments were obtained with 2.6 U of a proofreading enzyme (Expand High Fidelity PCR system; Boehringer Mannheim). The parE fragment used in these experiments was amplified with oligonucleotides parE105 (5′-GGAGGGAAATTCGGTCAAGGTGGCTA-3′; this sequence codes for the GGKFGNGGY amino acid sequence) and parE483 (9). Gel electrophoresis of the PCR products was carried out in agarose gels as described previously (32). The DNA fragments were purified with MicroSpin S400 HR columns (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and both strands were sequenced with an Applied Biosystems Prism 377 DNA sequencer, according to the protocols provided by the manufacturer, with both the primers used for the PCR amplifications and internal primers.

ATPase activity determinations.

Membrane-associated ATPase activity was measured as described previously (24). One unit of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that resulted in the release of 1 μmol of inorganic phosphate per ml per 30 min. The 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s; the means of two independent determinations) were defined as the concentration of the antimalarial agent required for a 50% reduction of enzymatic activity.

Chemicals.

OPT and QIN were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo. MFL (Ro 21-5998-000) was provided by Roche Laboratories, Basel, Switzerland. Other antimalarial drugs are identified by The Ohio State University (OSU) code numbers (18). New OSU compounds used were OSU207 and OSU255, which have molecular weights of 427.4 and 444.35, respectively.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences reported here have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AY061860 to AY061873.

RESULTS

Antimicrobial activities of MFL and OSU compounds.

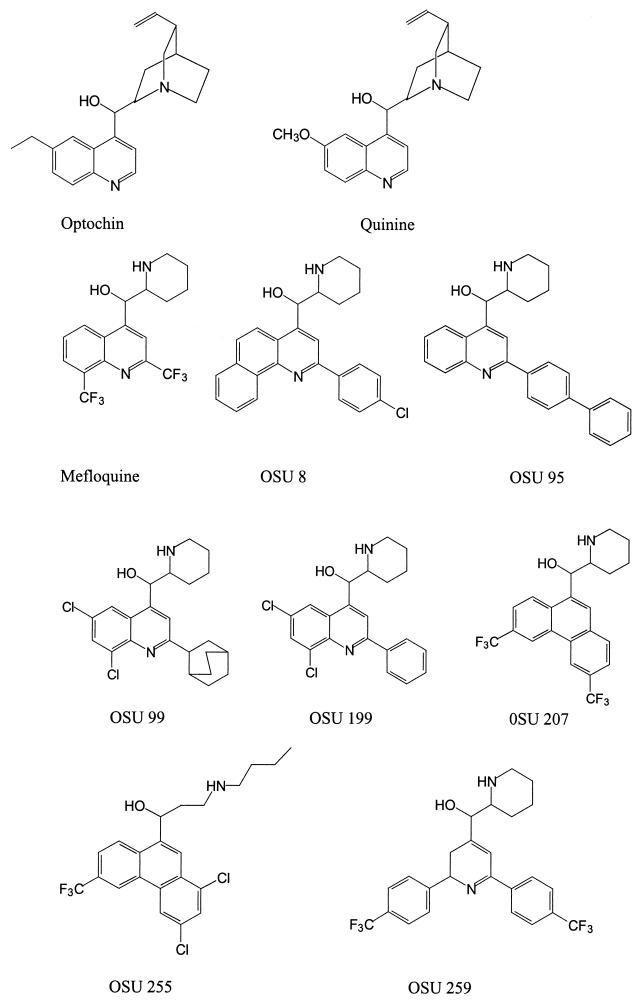

To test if MFL and the OSU compounds specifically target the F0F1 ATPase of S. pneumoniae, their MICs for OPT-resistant (Optr) and QIN-resistant (Qinr) strains were determined (Table 1). The chemical structures of these compounds are shown in Fig. 1. The strains used were R6 mutants with defined point mutations in atpC and were selected according to either their OPT resistance (strains MJ11 and MJ2) (6) or QIN resistance (strains MJQ3 and MJQ4) (24). Susceptible strains used as controls were R6, ATCC 6303, and ATCC 49619. MFL and the OSU compounds were 1.2- to 10-fold more active than OPT and 40- to >300-fold more active than QIN in inhibiting the growth of the last three S. pneumoniae strains. When the MICs for R6 were compared to those for the MJ2, MJ11, MJQ3, and MJQ4 mutants, significant increases (variations of two or more times the MIC) in the levels of resistance to MFL, OSU8, and OSU199 were observed for strains MJQ3 and MJQ4; and strain MJQ3 also showed a 15-fold increase in its level of resistance to OSU199 and OSU207. However, strain MJ2 showed an increased level of resistance only to MFL and OSU207, whereas there was no difference in the resistance of strain MJ11 to any of the compounds assayed. None of the mutant strains had increased levels of resistance to OSU compounds 95, 99, 255, and 259 (Table 1). These results together suggest that the c subunit of the F0 complex of the F0F1 ATPase is the target for MFL and OSU compounds 8, 199, and 207 and that for each mutant there is a characteristic pattern of inhibition by the various compounds.

TABLE 1.

Susceptibilities of S. pneumoniae strains to amino alcohol antimalarials

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPT | QIN | MFL | OSU8 | OSU95 | OSU99 | OSU199 | OSU207 | OSU255 | OSU259 | |

| ATCC 6303 | 0.75 | 25 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.15 |

| ATCC 49619 | 1.5 | 50 | 0.15 | 0.31 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| R6 | 1.5 | 50 | 0.15 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.62 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.62 | 1.25 |

| MJ11 | 24 | 72 | 0.15 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.62 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.62 | 1.25 |

| MJ2 | 24 | 230 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.62 | 1.25 | 1.25 |

| MJQ3 | 3 | 144 | 5 | 5 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 2.5 | 5 | 1.25 | 1.25 |

| MJQ4 | 18 | 180 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 1.25 | 1.25 |

| MJM3 | 6 | 200 | 2.5 | — | — | — | 5 | — | — | — |

| MJM5 | 48 | 200 | 5 | — | — | — | 5 | — | — | — |

| MJM6 | 12 | 100 | 2.5 | — | — | — | 0.62 | — | — | — |

| MJM7 | 3 | 200 | 1.25 | — | — | — | 0.62 | — | — | — |

| MJM8 | 6 | 100 | 5 | — | — | — | 2.5 | — | — | — |

| MJM9 | 12 | 200 | 0.62 | — | — | — | 1.25 | — | — | — |

| MJM11 | 12 | 100 | 2.5 | — | — | — | 1.25 | — | — | — |

| MJM13 | 24 | 400 | 10 | — | — | — | 10 | — | — | — |

| MJM15 | 12 | 200 | 5 | — | — | — | 2.5 | — | — | — |

| MJM21 | 6 | 200 | 2.5 | — | — | — | 2.5 | — | — | — |

| MJM22 | 24 | 200 | 2.5 | — | — | — | 2.5 | — | — | — |

—, not determined.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of the amino alcohol antimalarial agents used in this study.

Characterization of Mflr S. pneumoniae strains.

Mflr strains were obtained by plating 2 × 1010 R6 cells in 0.3 μg of MFL per ml (twofold the MIC). One isolate, designated isolate MJM1, was obtained. The atpC and atpA genes of this strain were amplified by PCR with oligonucleotides atporf1 and atpB56 and sequenced. A single mutation was observed in atpA; i.e., a TTT codon in strain R6 was changed to a TCT codon, which would produce an F209S change in the predicted amino acid sequence of the a subunit of the MJM1 F0F1 ATPase (data not shown). To provide genetic evidence that this change was indeed involved in MFL resistance, the PCR product obtained from strain MJM1 DNA carrying atpCA was used to transform competent R6 cells, and the same PCR product, but from R6 DNA, was used as a control. As expected, the PCR product from strain MJM1 transformed R6 to MFL resistance with a high degree of efficiency (greater than 105 transformants/ml). However, the R6 PCR product was also able to transform R6 to MFL resistance, although at a much lower efficiency (103 transformants/ml). Two colonies selected from the R6 transformation with the MJM1 PCR product were found to carry the F209S amino acid change in the a subunit, indicating that this mutation is indeed involved in MFL resistance. One of these transformants was named MJM11 (Table 2) and was used for further studies. Several colonies were selected from cultures of isolates used in the transformation experiment with the R6 PCR product, and the sequences of their aptCA genes were determined. These strains carried point mutations either in the atpC gene (strains MJM5, MJM7, MJM8, MJM9, MJM10, MJM13, MJM14, and MJM15) or in the atpA gene (strains MJM3, MJM6, MJM11, MJM21, and MJM22) (Table 2). Genetic evidence showing that the mutations carried by these strains were indeed involved in resistance was obtained by genetic transformation. The PCR products carrying those mutations were able to transform MFL-susceptible (Mfls) strain R6 to MFL resistance with a high degree of efficiency (greater than 105 transformants/ml). With the exception of strains MJM10 and MJM14, which had amino acid substitutions identical to those in MJQ3 and MJQ4, respectively, the susceptibilities of these strains to MFL and the OSU compounds were analyzed. The MICs of MFL for mutant strains selected for resistance to MFL were significantly increased (from 4- to 64-fold), as were the MICs of OSU199 (4- to 64-fold). All strains except MJM7 had increased levels of resistance to OPT (4- to 32-fold); and all strains except MJM6, MJM8, and MJM11 had increased levels of resistance to QIN (4- to 8-fold) (Table 1).

TABLE 2.

Mutational substitutions of the c and a subunits of S. pneumoniae strains resistant to amino alcohol antimalarial agents

| Strain | Amino acid change (codon change) from the R6 amino acid sequencea

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

c subunit

|

a subunit

|

|||

| α helix 1 | α helix 2 | α helix 5 | α helix 6 | |

| R6 | 13MGVSVGEGLLMN24 | 44MFLGVAFIEGTFFV57 | 178GEVMTSLLLL187 | 205AWTAFSVFIS214 |

| MJ11 | A49T (GCC→ACC) | |||

| MJ2 | V48L (GTT→CTT) | |||

| MJQ3 | M23I (ATG→ATA) | |||

| MJQ4 | G20A (GGT→GCT) | |||

| MJM3 | W206G (TGG→GGG) | |||

| MJM5 | G14S (GGC→AGC) | |||

| MJM6 | S214P (TCC→CCC) | |||

| MJM7 | V57L (GTA→CTA) | |||

| MJM8 | M13T (ATG→ACG) | |||

| MJM9 | M44V (ATG→GTG) | |||

| MJM10 | M23I (ATG→ATT) | |||

| MJM11 | F209S (TTT→TCT) | |||

| MJM13 | N24Y (AAT→TAT) | |||

| MJM14 | G20A (GGT→GCT) | |||

| MJM15 | G47A (GGT→GCT) | |||

| MJM21 | L186P (CTT→CCT) | |||

| MJM22 | W206C (TGG→TGT) | |||

The amino acid positions indicated refer to the coordinates for S. pneumoniae R6 (GenBank accession no. Z26851) (see reference 6). Residues that changed in the mutant strains indicated are shown in boldface. The E residues possibly involved in proton translocation are showed underlined in the α helices of the c subunit.

The appearance of Mflr colonies in the transformation with the 1,277-bp PCR product carrying the R6 atpCA genes might be attributed to the error rate of the polymerase. This rate is of 1 error/10 kbp; therefore, one error in 10 molecules of 1 kb would be expected. From our results, about 1% (10−2) of the putative nucleotide changes would result in a residue change that confers MFL resistance. Since 9 × 106 cells were used in the transformation experiments, the expected number of clones with mutations for MFL resistance would be 9 × 103, a figure consistent with the results obtained. Furthermore, when a 1,158-bp fragment of an unrelated gene (parE, coding for the ParE subunit of DNA topoisomerase IV) was amplified and used in transformation experiments, the frequency of Mflr colonies was equivalent to that obtained in the control experiment with no DNA (no colonies appeared in 0.1 ml of the transformation mixture, which gives a frequency of less than 10 transformants/ml). In addition, similar numbers (5 × 102 transformants/ml) of Mflr colonies were observed when a proofreading enzyme was used in the amplification of the atpCA genes, and no Mflr colonies appeared when parE was amplified with this enzyme.

Characteristics of the mutations affecting the c and a subunits of S. pneumoniae F0F1 ATPase.

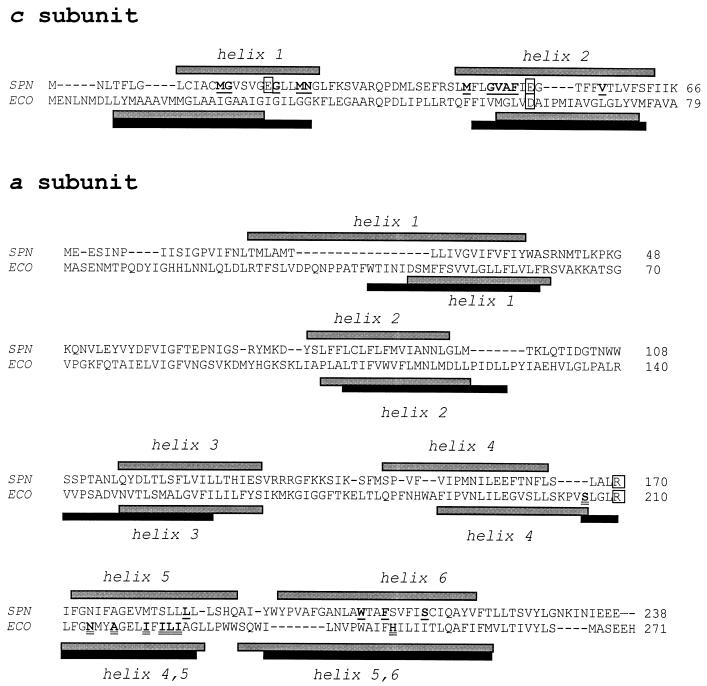

Predictions of the secondary structures of the c and a subunits were made by the PHD method (29-31) by using a server available over the Internet (http://www.embl-heidelberg.de). Those calculations predicted two transmembrane α helices for the c subunits and six transmembrane α helices for the a subunits of S. pneumoniae and E. coli (Fig. 2). Among the 13 Mflr strains obtained by selection with MFL (named MJMX, where the second M represents MFL; Table 2), 8 carried mutations in atpC and 5 carried mutations in atpA. All amino acid residues that changed in the Mflr stains were located in a predicted transmembrane α helix (Table 2; Fig. 2). Five strains showed changes in helix 1 in the c subunit, and three showed changes in helix 2 in the c subunit, while the changes in the a subunit were at residues located in helix 5 (one strain) and helix 6 (four strains).

FIG. 2.

Comparisons of the amino acid sequences and secondary structures of the c and a subunits of S. pneumoniae (SPN) and E. coli (ECO). The predicted α helices are shown above the sequence for S. pneumoniae and below the sequence for E. coli; gray bars indicate predictions made by the PHD method and solid bars indicate predictions made according to Miller et al. (22) (for the c subunit) or Valiyaveetil and Fillingame (35) (for the a subunit). Residues mutated in the resistant pneumococcal strains are shown in boldface and are underlined. Residues of the E. coli a subunit involved in interactions with the c subunit (11) are shown in boldface and are double underlined. Residues involved in proton translocation in E. coli and the equivalent residues in S. pneumoniae are boxed.

Inhibition of F0F1 ATPase by MFL and OSU compounds.

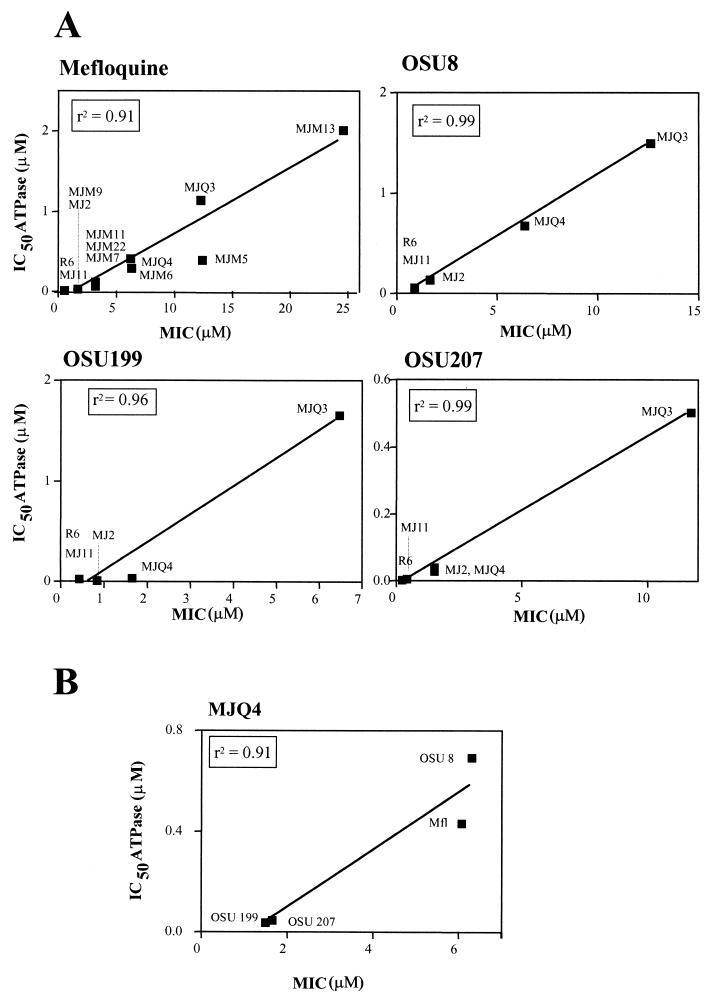

Biochemical evidence for the targeting of the F0F1 ATPase by MFL and related compounds was obtained by testing the inhibition of the ATPase activities of membranes obtained from strain R6 and the mutant strains. All compounds inhibited the R6 ATPase activity, including those compounds (OSU95, OSU99, OSU255, and OSU259) that inhibited the growth of both sensitive and resistant strains (Table 1). The levels of inhibition of the ATPase activities of the strains by MFL, OSU8, OSU199, and OSU207 (IC50 values) showed good correlations with their MICs (Fig. 3A), indicating that the primary target for these compounds in the cell is the membrane ATPase. A good correlation was also obtained when the IC50s of the different compounds were plotted against the MICs for strain MJQ4, a strain that showed intermediate sensitivities to most of the compounds tested (Fig. 3B), indicating that all compounds share the same target in the cell.

FIG. 3.

Correlations between inhibition of ATPase activity and inhibition of growth of the membranes of the indicated strains by MFL and the OSU compounds (A) and inhibition of growth of the membrane of MJQ4 by the different compounds (B).

DISCUSSION

Combined genetic and biochemical studies support a hairpinlike structure for the c subunit, with two α helices that transverse the membrane in an antiparallel fashion and that are separated by a conserved polar loop region that forms the F1 binding region (14). The Mflr pneumococcal strains had point mutations that change the amino acid residues located in one of the two transmembrane α helices of the c subunit at positions close to the two acidic residues E19 and E52 (Table 2; Fig. 2). Although previously characterized Optr strains, selected according to their OPT resistance (strains MJ2 and MJ11), had mutations in helix 1 (6) and strains selected according to their QIN resistance (strains MJQ3 and MJQ4) had mutations in helix 2 (24), the strains selected according to their MFL resistance had mutations in either helix 1 or helix 2 (Table 2; Fig. 2). However, independently of the compound used for mutant selection, cross-resistance to those three antimalarial agents was observed (Table 1; Fig. 2 and 3), suggesting that these chemically similar drugs interact with the c subunit in the same region of the protein, the ion-binding pocket. In the E. coli pocket, the D61 side chain is positioned within a four-helix bundle formed by the front and back faces of two adjacent monomers, with D61 of helix 2 of one monomer packing in close proximity to residues A24 and I28 of helix 1 and with A62 of helix 2 of the neighboring monomer (5, 13) being in a cavity created by the absence of side chains at residues G23, G27, and G58 (8). Interestingly, two of the S. pneumoniae-resistant strains (strains MJ11 and MJM5) had amino acid changes at positions equivalent to G23 and G58 of E. coli (Table 2; Fig. 2), and G-to-A changes are found in strains MJQ4 and MJM15. All these results suggest a structure for the oligomeric subunit c ring of S. pneumoniae compatible with that of E. coli. However, whereas the E. coli c subunit has only one carboxyl group (D61 of α helix 2), the S. pneumoniae c subunit has two carboxyl groups, one each in a centered position in each α helix (residues E19 and E52, equivalent to residues I28 and D61, respectively, of E. coli), suggesting that both carboxylic groups would be involved in proton translocation. In agreement with this hypothesis, functional ATPases from E. coli mutants in which the essential carboxyl group of the c subunit has been switched to position 24 of helix 1 (equivalent to V15 of S. pneumoniae) (22) or in which a second carboxyl group has been introduced at position 28 (equivalent to E19 of S. pneumoniae) (12) have been described.

In addition to mutations in the c subunit, five of the Mflr strains carried mutations in two α helices of the a subunit: position L186 of the penultimate helix and positions W206, F209, and S214 of the ultimate helix (Fig. 2). These two helices are also present in the E. coli a subunit (Fig. 2). Studies of cysteine cross-linking (11) and nuclear magnetic resonance analysis (28) have established that helix 2 of subunit c makes contact with the penultimate helix of subunit a (Fig. 2), with residues S207, N214, A217, I221, I223, L224, and I225 lying in one face of the transmembrane helix. These residues then interact with helix 2 of subunit c. This proximity of the helices supports the possibility of an interaction between residue R210 of the a subunit and residue D61 of the c subunit during proton translocation. The location of the L186P change in S. pneumoniae MJM21 is in accordance with this model of the F0 complex of E. coli.

Four residue changes present in the resistant S. pneumoniae strains are located in the last helix of subunit a (Fig. 2), suggesting an interaction between this helix of the a subunit and any of the helices of the c subunit. Although no cross-link formation has been observed between helix 1 of the E. coli subunit c and the last helix of subunit a (11), a mutant strain with an H245D substitution showed a 45% reduction of normal proton translocation activity (3), and structural studies have defined one hydrophilic pathway between R210 of the E. coli a subunit and the periplasmic surface, including residues N238, H245, and Q252 of the last helix of this protein (11).

The location and nature of the amino acid changes found in the c subunit of the R6 descendants reported here are in accordance with those observed in pneumococcal Optr clinical isolates, which showed G20S, M23I, A49T, V48F, and F50L changes (6, 27). In addition, a change in the a subunit (W206S) that corresponds to that found in strain MJM3 has also been recently reported in a clinical isolate of S. pneumoniae (27).

Acknowledgments

We thank E. García for critical reading of the manuscript. The technical assistance of A. Rodríguez-Bernabé is acknowledged.

A.J.M.-G. received a fellowship from Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid. This study was supported by grant 1274/01 from Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrahams, J. P., A. G. W. Leslie, and J. E. Walker. 1994. Structure at 2.8 Å resolution of F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria. Nature 370:621-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bender, G., S. Sutton, and R. Marquis. 1986. Acid tolerance, proton permeabilities, and membrane ATPases of oral streptococci. Infect. Immun. 53:331-338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cain, B. D., and R. D. Simoni. 1988. Interaction between Glu-219 and His-245 within the a subunit of F1F0-ATPase in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 263:6606-6612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, D. K., A. McGeer, J. C. de Azavedo, and D. E. Low. 1999. Decreased susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae to fluoroquinolones in Canada. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:233-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dmitrev, O. Y., P. C. Jones, and R. H. Fillingame. 1999. Structure of the subunit c oligomer in the F1F0 ATP synthase: model derived from solution structure of the monomer and cross-linking in the native enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:7785-7790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenoll, A., R. Muñoz, E. García, and A. G. de la Campa. 1994. Molecular basis of the optochin-sensitive phenotype of pneumococcus: characterization of the genes encoding the F0 complex of the Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus oralis H+-ATPases. Mol. Microbiol. 12:587-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Futai, M., T. Noumi, and M. Maeda. 1989. ATP synthase (H+-ATPase): results by combined biochemical and molecular biological approaches. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 58:111-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Girvin, M. E., V. K. Rastogi, F. Abrildgaard, J. L. Markley, and R. H. Fillingame. 1998. Solution structure of the transmembrane H+-translocating subunit c of the F1F0 ATP synthase. Biochemistry 37:8817-8824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.González, I., M. Georgiou, F. Alcaide, D. Balas, J. Liñares, and A. G. de la Campa. 1998. Fluoroquinolone resistance mutations in the parC, parE, and gyrA genes of clinical isolates of viridans group streptococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2792-2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffman, J., M. S. Cetron, M. M. Farley, W. S. Baughman, R. R. Facklam, J. A. Elliot, K. A. Deaver, and R. F. Breiman. 1995. The prevalence of drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Atlanta. N. Engl. J. Med. 333:481-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang, W., and R. H. Fillingame. 1998. Interacting helical faces of subunits a and c in the F1F0 ATP synthase of Escherichia coli defined by disulfide cross-linking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:6607-6612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones, P. C. 2001. Introduction of a carboxyl group in the first transmembrane helix of Escherichia coli F1F0 ATPase subunit c and cytoplasmic pH regulation. J. Bacteriol. 183:1524-1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones, P. C., W. Jiang, and R. H. Fillingame. 1998. Arrangement of the multicopy H+-translocating subunit c in the membrane sector of the Escherichia coli F1F0 ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:1718-1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kakinuma, Y. 1998. Inorganic cation transport and energy transduction in Enterococcus hirae and other streptococci. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1021-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi, H., T. Suzuki, N. Kinoshita, and T. Unemoto. 1984. Amplification of the Streptococcus faecalis proton-translocating ATPase by a decrease in cytoplasmic pH. J. Bacteriol. 158:1157-1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi, H., T. Suzuki, and T. Unemoto. 1986. Streptococcal cytoplasmic pH is regulated by changes in amount and activity of a proton-translocating ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 261:627-630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koebmann, B. J., D. Nilsson, O. P. Kuipers, and P. R. Jensen. 2000. The membrane-bound H+-ATPase complex is essential for growth of Lactococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 182:4738-4743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kullen, M. J., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1999. Identification of the pH-inducible, proton-translocating F1F0-ATPase (atpBEFHAGDC) operon of Lactobacillus acidophilus by differential display: gene structure, cloning and characterization. Mol. Microbiol. 33:1152-1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kunin, C. M., and W. Y. Ellis. 2000. Antimicrobial activities of mefloquine and a series of related compounds. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:848-852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liñares, J., A. G. de la Campa, and R. Pallarés. 1999. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:1546-1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martín-Galiano, A. J., M. J. Ferrándiz, and A. G. de la Campa. 2001. The promoter of the operon encoding the F0F1 H+-ATPase of Streptococcus pneumoniae is inducible by pH. Mol. Microbiol. 6:1327-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller, M. J., M. Oldenburg, and R. H. Fillingame. 1990. The essential carboxyl group in subunit c of the F1F0 ATP synthase can be moved and H+-translocation retained. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:4900-4904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore, H. F., and A. M. Chesney. 1917. A study of ethylhydrocuprein (optochin) in the treatment of acute lobar pneumonia. Arch. Intern. Med. 19:611-682. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muñoz, R., E. García, and A. G. de la Campa. 1996. Quinine specifically inhibits the proteolipid subunit of the F0F1 H+-ATPase of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 178:2455-2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A4. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Villanova, Pa.

- 26.Pallarés, R., J. Liñares, M. Vadillo, C. Cabellos, F. Manresa, P. F. Viladrich, R. Martín, and F. Gudiol. 1995. Resistance to penicillin and cephalosporin and mortality from severe pneumococcal pneumonia in Barcelona, Spain. N. Engl. J. Med. 333:474-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pikis, A., J. M. Campos, W. J. Rodríguez, and J. M. Keith. 2001. Optochin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae: mechanism, significance, and clinical implications. J. Infect. Dis. 184:582-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rastogi, V. K., and M. E. Girvin. 1999. Structural changes linked to proton translocation by subunit c of the ATP synthase. Nature 402:263-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rost, B. 1996. PHD: predicting one-dimensional protein structure by profile-based neural networks. Methods Enzymol. 266:525-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rost, B., P. Fariselli, and R. Casadio. 1996. Topology prediction for helical transmembrane proteins at 86% accuracy. Protein Sci. 5:1704-1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rost, B., and C. Sander. 1993. Prediction of protein secondary structure at better than 70% accuracy. J. Mol. Biol. 232:584-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 33.Stock, D., A. G. W. Leslie, and J. E. Walker. 1999. Molecular architecture of the rotary motor in ATP synthase. Science 286:1700-1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomasz, A. 1970. Cellular metabolism in genetic transformation of pneumococci: requirement for protein synthesis during induction of competence. J. Bacteriol. 101:860-871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valiyaveetil, F. I., and R. H. Fillingame. 1998. Transmembrane topography of subunit a in the Escherichia coli F1F0 ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:16241-16247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]