Abstract

Lipooligosaccharide (LOS) is a major surface component of Moraxella catarrhalis and a possible virulence factor in the pathogenesis of human infections caused by this organism. The presence of LOS on the bacterium is an obstacle to the development of vaccines derived from whole cells or outer membrane components of the bacterium. An lpxA gene encoding UDP-N-acetylglucosamine acyltransferase responsible for the first step of lipid A biosynthesis was identified by the construction and characterization of an isogenic M. catarrhalis lpxA mutant in strain O35E. The resulting mutant was viable despite the complete loss of LOS. The mutant strain showed significantly decreased toxicity by the Limulus amebocyte lysate assay, reduced resistance to normal human serum, reduced adherence to human epithelial cells, and enhanced clearance in lungs and nasopharynx in a mouse aerosol challenge model. Importantly, the mutant elicited high levels of antibodies with bactericidal activity and provided protection against a challenge with the wild-type strain. These data suggest that the null LOS mutant is attenuated and may be a potential vaccine candidate against M. catarrhalis.

Moraxella catarrhalis, a gram-negative diplococcus, is the third most common isolate after Streptococcus pneumoniae and nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae as the causative agent of otitis media, which is the leading cause of conductive hearing loss in children, and of the exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases in adults, which is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States (7, 23, 41). In immunocompromised hosts, M. catarrhalis causes a variety of severe infections, including septicemia and meningitis. Clinical and epidemiological studies revealed high carriage rates in young children and suggested that a high rate of colonization was associated with an increased risk of the development of M. catarrhalis-mediated diseases (28). In addition, the number of antibiotic-resistant strains of M. catarrhalis has increased significantly over the past decades (5, 18). Currently, the molecular pathogenesis of M. catarrhalis infection is not fully understood, and there is no vaccine to prevent M. catarrhalis infections (27).

Active immunization with a vaccine would be an efficient approach for the prevention of M. catarrhalis infections. At present, we have only limited knowledge about which antigens confer protective immunity against M. catarrhalis infections. Whole cells or components on the surface of the bacterium, such as outer membrane proteins (OMPs), should induce specific immunity (27). A major obstacle to the development of safe and effective vaccines derived from the cells or outer membrane is the presence of toxic lipooligosaccharide (LOS). LOS is a main outer membrane component of M. catarrhalis and a potential virulence factor in the pathogenesis of infections (9, 12). Unlike the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of enteric bacteria, M. catarrhalis LOS consists only of an oligosaccharide core and lipid A (10). In contrast to most of the LOS or LPS molecules, the inner core oligosaccharide of M. catarrhalis LOS is attached to 3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonic acid (Kdo) with a glucosyl residue instead of a heptosyl residue (19, 30). The lipid A portion of the LOS is similar to that of other bacteria (19, 26).

Recently, several genes associated with LOS biosynthesis of M. catarrhalis were reported. Zaleski et al. identified a galE gene encoding UDP-glucose-4-epimerase in M. catarrhalis and showed that the inactivation of the gene resulted in a truncated LOS structure lacking two terminal galactosyl residues (45). Luke et al. showed a kdsA gene encoding Kdo-8-phosphate synthase and found a kdsA-deficient mutant consisting only of lipid A on its LOS molecule (25). Edwards et al. revealed a cluster of three LOS glycosyltransferase genes (lgt) for the extension of oligosaccharide chains to the inner core (11). We also identified a kdtA gene encoding Kdo transferase during the LOS biosynthesis (29). However, information pertaining to the first step of the LOS biosynthesis on the lipid A moiety of the LOS in particular remains unknown.

Our knowledge of the enzymology and molecular genetics of the lipid A biosynthesis is based mainly on the studies of the LPS expressed by the enteric bacteria, especially Escherichia coli (30). In E. coli, the first reaction of lipid A biosynthesis isthe acylation of the sugar nucleotide UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc). The UDP-GlcNAc acyltransferase (lpxA) is selective for catalyzing the transfer of a β-hydroxymyristoyl moiety from the R-3-hydroxymyristoyl acyl carrier protein to the 3 position of the glucosamine ring of UDP-GlcNAc (4). Inactivation of the lpxA gene may block the initial step of the lipid A biosynthesis pathway, resulting in a bacterium with an LOS-deficient structure. Previous attempts to construct lpxA knockout mutants in E. coli or other gram-negative bacteria failed because a minimal structure of Kdo2-lipid A was required for bacterial viability (15, 30, 31). Several years ago, an LOS-deficient mutant of Neisseria meningitidis was reported when its lpxA gene was inactivated (33). However, the immunogenicity of the cells or of outer membrane components from the mutant strain was reduced greatly (35). To date, no report has documented a comparable mutant from other bacterial species, despite an attempt with both H. influenzae and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (40).

In this work, we identified an lpxA homologue from M. catarrhalis and constructed an lpxA knockout mutant. The mutant was viable in spite of the complete loss of LOS. Further analysis of the physicochemical features and biological functions of the mutant was performed. We found that this mutant was attenuated but was as highly immunogenic as the parental strain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains are described in Table 1. M. catarrhalis strains were cultured on chocolate agar plates (Remel, Lenexa, KS), or brain heart infusion (BHI) (Difco, Detroit, MI) agar plates at 37°C in 5% CO2. Mutant strains were selected on BHI agar supplemented with kanamycin at 20 μg/ml. Growth rates of wild-type and mutant strains were measured from overnight cultures inoculated in 10 ml of BHI broth (adjusted optical density at 600 nm [OD600] = 0.05) and incubated at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm. Samples from each bacterial culture were monitored spectrophotometrically at 600 nm for 8 h. The data represented averages of three independent assays. E. coli was grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates or LB broth with antibiotic supplementation as needed.

TABLE 1.

Summary of strains, plasmids, and primers

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| M. catarrhalis O35E | Wild-type strain | 17 |

| M. catarrhalis O35ElpxA | UDP-GlcNAc acyltransferase-deficient strain | This study |

| E. coli TOP10 | Cloning strain | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1 | TOPO TA cloning vector | Invitrogen |

| pCRL | lpxA cloned into pCR2.1 | This study |

| pBluescript II SK(+) | Cloning vector | Fermentas |

| pSL | EcoRI-SalI lpxA fragment cloned into SK(+) | This study |

| pUC4k | Kanamycin resistance cassette | Amersham |

| pSLK | EcoRI-blunted kanamycin resistance cassette inserted into blunted HindIII site of pSL | This study |

| Primers | ||

| 41 | 5′-CTC GTC GAC ATT CAC CCC ACA GCG ATT-3′ (lpxA sense; SalI site underlined) | This study |

| 42 | 5′-CTC GAA TTC TAT CGA ACC AAA CCA CGC-3′ (lpxA antisense; EcoRI site underlined) | This study |

| 43 | 5′-GGT GGA TGG CGT CAA ATG-3′, flanking the 5′ end of lpxA gene | This study |

| 44 | 5′-GAT TTC GTC AAA TGG GCG-3′ (fabZ sense) | This study |

| 45 | 5′-TGT GGG GTG AAT CGT CAT-3′ (fabZ antisense) | This study |

| 46 | 5′-ATG TCG GCG CAA CGA GAA-3′ (sdt sense) | This study |

| 47 | 5′-CCA TGG TTA ATT CAC AGG-3′ (sdt antisense) | This study |

| 48 | 5′-ATG ACG ATT CAC CCC ACA-3′ (lpxA sense) | This study |

| 49 | 5′-TTA TCG AAC CAA ACC ACG C-3′ (lpxA antisense) | This study |

| 50 | 5′-GGT GCG ACA ATC TAT CGA-3′ (kanamycin sense) | This study |

| 51 | 5′-CTC ATC GAG CAT CAA ATG-3′ (kanamycin antisense) | This study |

General DNA methods.

DNA restriction endonucleases, T4 DNA ligase, E. coli DNA polymerase I Klenow fragment, and Taq DNA polymerase were purchased from Fermentas (Hanover, MD). The preparation of plasmid (Table 1) and the purification of PCR products or DNA fragments were performed using kits manufactured by QIAGEN (Santa Clarita, CA). Bacterial chromosomal DNA was isolated with a genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI). DNA nucleotide sequences were obtained via use of a 3070xl DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and analyzed with DNASTAR software (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI).

Cloning of an lpxA homologue and construction of an lpxA knockout mutant.

PCR primers for cloning of the lpxA homologue from strain O35E were designed on the basis of an assumptive M. catarrhalis lpxA sequence predicted by BLAST searches in sequence 37 of the M. catarrhalis genome (NCBI patent number WO0078968). A PCR product was amplified from chromosomal DNA of strain O35E using primers 41 and 42 (Table 1; Fig. 1), and cloned into pCR2.1 using a TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to obtain pCRL (Table 1). The insertion was released by EcoRI-SalI digestion and then subcloned into an EcoRI-SalI site of pBluescript II SK(+) to form pSL. A kanamycin resistance cassette (1,282 bp) obtained from pUC4k after EcoRI digestion was subsequently cloned into the lpxA gene using a HindIII site to form pSLK (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization of M. catarrhalis LOS biosynthesis gene cluster containing lpxD, fabZ, and lpxA. Large arrows represent the direction of transcription, and the location of deletion replaced by the kanamycin resistance gene (Kanr gene) is between two HindIII cleavage sites. A gene downstream from lpxA is a putative sodium-dependent transporter (sdt). The sites of primers used are indicated with small arrows (Table 1).

After verification by sequence analysis, the construct was amplified by PCR using primers 41 and 42. The PCR product was purified and used for electroporation (17) with modifications. Briefly, a 20-ml portion of culture (OD600 = 0.5) from strain O35E was harvested by centrifugation and washed three times with 10% glycerol in distilled water. The cell pellet was suspended in 150 μl of the glycerol solution. A 20-μl portion of this cell suspension was mixed with 1.0 μg of the PCR product in 2 μl of water, transferred into a microelectroporation chamber, and electroporated using a field strength of 2.2 kV over a 0.1-cm distance for the electroporation (Micropulser; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The resulting cell suspension was mixed with 1 ml of BHI broth, shaken at 250 rpm at 37°C for 6 h, and plated on BHI agar containing kanamycin. After 24 h incubation, the kanamycin-resistant colonies were selected for PCR analysis of chromosomal DNA using primers 42 and 43 (Fig. 1; Table 1). The inactivated lpxA mutant was confirmed by sequence analysis and designated O35ElpxA. OMPs of both mutant and wild-type strains were prepared by the Zwittergent-extraction method (6) and examined on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels with 12% separating gel.

Southern blotting.

The kanamycin resistance gene was amplified from pUC4K as a probe with primers 50 and 51 (Table 1) by using a PCR digoxigenin (DIG) probe synthesis kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Southern blot analysis of the chromosomal DNA from both O35E and O35ElpxA was performed using a DIG DNA labeling and detection kit (Roche) according to the instruction manual. The hybridization temperature of the Southern blot was 42°C, and the washings were done under a high-stringency condition (65°C in 0.5 × SSC [1 × SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate] with 0.1% SDS).

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from log-phase bacteria of strains O35E and O35ElpxA by using an RNeasy Mini kit and treated with an on-column RNase-free DNase set (QIAGEN). The first-strand synthesis of cDNA was primed with random primers using a high-capacity cDNA archive kit (Applied Biosystems). Primer sets for PCR amplification of target genes fabZ, lpxA, and sdt in cDNA samples are listed in Table 1 and depicted in Fig. 1. In parallel, PCRs were performed with chromosomal DNA samples as positive controls and with cDNA samples without activation of the reverse transcription (RT) as negative controls. The PCR products were resolved on 0.8% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Restoration of native LOS in lpxA mutant through reversion to wild type.

Primers 48 and 49 (Table 1) were used to amplify native lpxA from chromosomal DNA of the wild-type strain, O35E. The resulting PCR product was purified and used to transform O35ElpxA-competent cells by electroporation as described above. Potential revertant colonies were identified as having lost kanamycin resistance through replicate plating on BHI agar plates with or without kanamycin. One colony that lost kanamycin resistance was chosen as a revertant strain for further analyses. Chromosomal DNA was isolated from the revertant strain and subjected to PCR and sequence analysis to confirm that the wild-type lpxA gene had properly integrated into the genome of the O35ElpxA mutant.

LOS detection.

The purification of LOS was performed with wild-type strain O35E, the mutant O35ElpxA, and the revertant strain by use of a proteinase K-treated whole-cell lysate method (38). The resulting extracts from each bacterial suspension (1.9 μg of protein content) were resolved by SDS-PAGE with 15% separating gels and visualized by silver staining for carbohydrates (37). Western blotting was performed using an anti-LOS monoclonal antibody (MAb), 8E7, to detect the LOS (21).

Composition analysis.

Thirty to 35 grams (wet weight) of cells from O35E or from O35ElpxA was used for LOS purification by phenol-water extraction (16). Due to the lack of LOS in extracts from O35ElpxA, the O35ElpxA cells were further extracted with phenol-chloroform-petroleum ether (13). Composition analysis of the above extracts was performed by a gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis of trimethylsilyl methylglycosides and of fatty acid methyl esters (44) on an HP-5890 GC interfaced to a mass selective detector, 5970 MSD, using a Supelco DB1 fused silica capillary column (30-mm length by 0.25-mm internal diameter; J &W Scientific, Folsom, CA).

LAL assay.

A chromogenic Limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) assay for endotoxin activity was performed using a QCL-1000 kit (Bio-Whittaker Inc., Walkersville, MD). Overnight cultures from chocolate agars were suspended in BHI broth to OD620s of 0.1, and serial dilutions of these stocks were used as samples.

Susceptibility.

The sensitivities of strains to a panel of hydrophobic agents or hydrophilic glycopeptide were assayed using standard disk diffusion assays (43). Bacteria were cultured in BHI broth to OD600s of 0.2, and 100-μl portions of the bacteria were spread onto chocolate agar plates. Antibiotic disks or sterile blank paper disks (6 mm; Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, MD) saturated with the various agents were plated on the lawn in triplicate, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 h. Sensitivities were assessed by measuring the diameters of the zones of growth inhibition on two axes, and the mean values were calculated.

Bactericidal assay with normal human serum.

A complement-sufficient normal human serum pool from eight healthy adult donors was prepared. A 200-μl-scale bactericidal assay was performed in a 96-well plate (25). The normal human serum pool was diluted to 0.5, 2.5, 5.0, 12.5, and 25% in pH 7.4 Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer (containing magnesium and calcium with 0.05% gelatin). Bacteria (10 μl containing 106 CFU) were inoculated into 190-μl reaction wells containing the diluted normal human serum, 25% of heat-inactivated normal human serum, or the PBS buffer alone. After 30 min of incubation at 37°C, samples were diluted serially (1:10) and plated onto chocolate agar plates. The resulting colonies were counted after 24 h of the incubation.

Adherence assay.

Chang (conjunctival; CCL20.2), HeLa (cervix; CCL-2), and A549 (lung; CCL-185) human epithelial lines were cultured in Eagle's minimal essential medium (ATCC, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum at 37°C in 5% CO2. A quantitative adherence assay was performed (1). Briefly, a 1-ml portion with 2 × 105 cells was seeded into each well of 24-well tissue culture plates and incubated for 24 h. Bacteria in the logarithmic phase of growth were suspended in PBS buffer at concentrations of 108 CFU/ml. Aliquots (100 μl) of the suspension were inoculated in duplicate into the wells of the 24-well plate containing a monolayer of each cell line. This plate was centrifuged for 5 min at 165 × g and then incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Nonadherent bacteria were removed by rinsing the wells five times with the PBS buffer, and the epithelia were released from the plate by adding 0.05% trypsin-EDTA. This cell suspension was serially diluted in the PBS buffer and spread onto BHI plates to determine the number of viable bacteria. Adherence was expressed as the percentage of bacteria attached to the human cells relative to the original number of bacteria added to the well. The data represented averages of three independent assays.

Pulmonary and nasopharyngeal clearance.

Female BALB/c mice (6 to 8 weeks of age), from Taconic Farms Inc. (Germantown, NY), were housed in an animal facility in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines under Animal Study Protocol 1158-04. A bacterial aerosol challenge was carried out in mice using 10-ml portions of 1.65 × 109- and 1.80 × 109-CFU/ml suspensions of wild-type strain O35E and mutant strain O35ElpxA, respectively (20). The numbers of bacteria present in the lungs and nasal washes were measured at various time points postchallenge. The minimum numbers for the detection of viable bacteria were 100 CFU per lung (10 ml) and 4 CFU per nasal washing (0.4 ml). Clearance of M. catarrhalis was expressed as the percentage of bacterial CFU detectable at each time point compared with the number deposited at time zero.

Antibody response and challenge study.

Eight mice in each group received three subcutaneous injections of 0.2-ml doses containing 1 × 108 CFU of heat-killed whole cells of wild-type or mutant strains or PBS with or without Ribi-700 adjuvant (Corixa Corporation, Hamilton, MT) at 10-day intervals. Blood samples were collected at 2 weeks after the last injection. Serum antibodies were assayed by whole-cell enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), for which ELISA plates were coated with 50 μl of O35E or O35ElpxA (4 × 107 CFU/ml) and dried at 50°C overnight. Other steps were performed as described previously (21). For bactericidal activity against wild-type strain O35E, pooled mouse sera from each group were used after inactivation at 56°C for 30 min. A bactericidal assay was performed (16), and titers were expressed as the last dilution of the sera causing at least 50% killing compared with that caused by a control.

A challenge study was performed with the mice immunized with whole cells of the wild type or of the mutant with Ribi adjuvant. The mice were aerosol challenged with 10 ml of wild-type strain O35E (4 × 109 CFU/ml). The number of CFU present in the lungs was measured at 6 h postchallenge (20).

Statistical analysis.

The numbers of viable bacteria were expressed as the geometric mean CFU of six independent observations each ± standard deviations (SD). The antibody titers were expressed as geometric mean ELISA units of eight independent observations ± SD. The significance was analyzed using a two-tailed independent Student's t test. The bacterial clearance rate was analyzed by a chi-square test.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the lpxA gene in M. catarrhalis strain O35E was deposited at GenBank under accession number AY648946.

RESULTS

Identification and cloning of M. catarrhalis O35E lpxA homologue.

The putative lpxA gene in M. catarrhalis strain O35E was identified by BLAST searches of the M. catarrhalis genome. The strain O35E lpxA gene homologue was amplified using primers 41 and 42 and cloned into pCR2.1. Nucleotide sequence analysis showed that the DNA fragment contained a single open reading frame of 774 bp with a predicted gene product of 257 amino acids. The deduced polypeptide sequence showed 53% and 45% identities with known lpxA amino acid sequences of E. coli and N. meningitidis, respectively. Upstream sequence analysis of the lpxA gene revealed the presence of lpxD and fabZ, two genes linked to lpxA (Fig. 1). The same gene order was seen in the chromosomal DNA of E. coli and of N. meningitidis (30, 34). Sequence analysis for the downstream gene of lpxA revealed the presence of genes encoding a sodium-dependent transporter (sdt), which was not related to LOS biosynthesis.

Construction and characterization of an lpxA knockout mutant.

An lpxA mutant was constructed by allelic exchange with a substitution of a kanamycin resistance cassette and a 241-bp deletion within the lpxA coding region, where the lpxA gene was disrupted (Fig. 1). The disrupted lpxA gene was amplified from kanamycin-resistant colonies using primers 42 and 43. Nucleotide sequence analysis of PCR products confirmed that the kanamycin resistance cassette had been inserted into the lpxA gene of the O35E chromosomal DNA at the predicted position. Thus, a mutant strain, O35ElpxA, was generated.

To test whether a single copy of the kanamycin resistance gene was inserted into the genome of wild-type strain O35E, chromosomal DNA of the parental O35E or the mutant O35ElpxA was digested with EcoRV (Fig. 2A) and probed with a DIG-labeled kanamycin resistance gene. Only one band was detected in the chromosomal DNA of the mutant O35ElpxA (Fig. 2B, lane 2), but no band was detected in that of the parental O35E (Fig. 2B, lane 1), showing that there was a single insertion in the genome of the lpxA mutant.

FIG. 2.

Detection of kanamycin resistance gene inserted into O35ElpxA chromosomal DNA by Southern blotting. Lanes 1, 5 μg of chromosomal DNA from O35E plus EcoRV; lanes 2, 5 μg of chromosomal DNA from O35ElpxA plus EcoRV; and lanes 3, 0.2 μg of pUC4K (a plasmid with a kanamycin resistance cassette as positive control) plus EcoRI. Each digested sample was resolved on a 0.7% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining (A). Southern blotting was performed using DIG-labeled kanamycin resistance gene probe (B). Lambda DNA/EcoRI-plus-HindIII molecular size standards (Fermentas) are shown in base pairs on the left (lane M).

To determine whether the insertion had a polar effect on the downstream gene, total RNA isolated from both parental O35E and the mutant O35ElpxA was subjected to RT-PCR analysis using primer sets designed for genes fabZ (primers 44 and 45), lpxA (primers 41 and 42), and sdt (primers 46 and 47), respectively. Compared to the parental O35E (Fig. 3), the insertion of the kanamycin resistance gene in the mutant O35ElpxA disrupted only the transcription of the lpxA gene (lane b4) and had no effect on transcription of the upstream (fabZ; lane a4) and the downstream (sdt; lane c4) genes.

FIG. 3.

Detection of lpxA gene expression by RT-PCR. The RT-PCRs were performed using the following nucleic acid templates: total RNA from O35E (lanes 1 and 3) and O35ElpxA (lanes 4 and 6), and chromosomal DNA from O35E (lanes 2) and O35ElpxA (lanes 5). Reaction sets contained the following primers: for lanes labeled “a,” 44 and 45; for lanes labeled “b,” 41 and 42; and for lanes labeled “c,” 46 and 47. The controls (lanes 3 and 6) used total RNA as the nucleic acid template without activation of the RT. GeneRuler DNA ladder mix (Fermentas) was used for the molecular size standards in base pairs (lane M).

Determination of LOS in the lpxA mutant.

An attempt was made to isolate LOS from proteinase K-treated cell lysates ofboth O35E and O35ElpxA. Silver staining analysis after SDS-PAGE with both extracts revealed that LOS was detectable in O35E but not in O35ElpxA (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 and 2). The LOS band was confirmed by Western blot analysis, in which a specific anti-LOS MAb, 8E7, detected LOS in O35E but not in O35ElpxA (Fig. 4B, lanes 1 and 2).

FIG. 4.

LOS patterns from SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining (A) or Western blotting (B) of M. catarrhalis wild-type strain O35E (lanes 1), mutant O35ElpxA (lanes 2), and the O35ElpxA revertant (lanes 3). Panel A represents extracts from proteinase K-treated whole-cell lysates from each bacterial suspension (1.9 μg of protein content). Anti-LOS MAb 8E7 was used at a 1:100 dilution for panel B. Molecular mass markers (Mark12; Invitrogen) are indicated on the left.

The absence of the LOS from O35ElpxA was further confirmed by the GC-MS analysis of fatty acids of the phenol-chloroform-petroleum ether extract from O35ElpxA. The composition analysis showed no specific lipid A component in the O35ElpxA sample (Fig. 5A). Only palmitic, vaccenic, and stearic acids (C16:0, C18:1, and C18:0) were detected, which could be due to the presence of phospholipids. In contrast, the components of the parental O35E consisted of lipid A-specific β-hydroxyl fatty acids, such as 3-OHC12:0, and sugar components, including Kdo (Fig. 5B). Both 3-OHC12:0 and Kdo were found only in the LOS or LPS of gram-negative bacteria.

FIG. 5.

Total ion current (TIC) spectrum from GC-MS analysis of 100 μg of phenol-chloroform-petroleum ether extract material from M. catarrhalis mutant O35ElpxA (A) or phenol-water extract material from wild-type strain O35E (B). The components of O35ElpxA were identified as indicated and show the fatty acids C16:0, C18:1, and C18:0, which are constituents of phospholipids (A). The components of O35E showed the sugar constituents Kdo, Gal, Glc, and GlcNAc and specific lipid A fatty acids (3-OHC12:0) (B). Inositol was added as an internal standard.

To confirm that the loss of LOS expression was due to an internal deletion in the lpxA coding region, wild-type lpxA was reintroduced into the chromosome of O35ElpxA. Silver staining analysis with the revertant strain showed that an LOS band restored and migrated in a manner identical to that of the wild-type LOS (Fig. 4A, lane 3). This LOS band was further confirmed by Western blot analysis and regained the reactivity to the anti-LOS MAb, 8E7 (Fig. 4B, lane 3). The restoration of the native LOS in the lpxA mutant confirmed that the observed LOS deficiency had resulted from a mutation located in the lpxA gene.

Morphology, growth rate, and OMP profile of the lpxA mutant.

O35ElpxA was found to form large, thin, flat, and transparent colonies on the chocolate agar plates compared with the wild-type strain. When the mutant grew in BHI broth, its growth rate was slightly lower than that of the wild-type strain in logarithmic phase (Fig. 6A). However, the wet weight of mutant cells was greater than that of cells of the wild-type strain at stationary phase (overnight growth) by 30 to 50%. Comparative analysis of OMPs by SDS-PAGE indicated that the major OMP profiles of the wild-type and mutant strains were similar, while an approximately 55-kDa protein was dramatically up-regulated and a ∼16-kDa protein was absent in the mutant strain (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

(A) Growth curves of M. catarrhalis wild-type strain O35E (⧫) and mutant O35ElpxA (□) in BHI broth at 37°C. (B) The corresponding OMP profiles of M. catarrhalis wild-type O35E (left lane) and mutant O35ElpxA (right lane) were visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue staining after SDS-PAGE. Molecular mass marker values are in kilodaltons.

Biological activity of the lpxA mutant.

The lpxA mutant was tested for LOS-associated biological activity. In an LAL assay, whole-cell suspensions (OD620 = 0.1) gave 3.7 × 103 endotoxin units/ml for O35E and 0.14 endotoxin unit/ml for O35ElpxA, which was the same level as that for a negative medium control and a 20,000-fold reduction from that for the wild-type strain.

In a susceptibility test with a broad range of hydrophobic agents and a hydrophilic glycopeptide, the mutant O35ElpxA was more susceptible to most hydrophobic antibiotics and reagents and also to a hydrophilic glycopeptide, vancomycin, than the parental strain was (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Susceptibilities of M. catarrhalis wild-type strain O35E and mutant O35ElpxA to a panel of hydrophobic agents or hydrophilic glycopeptide

| Compound | Zone of growth inhibition (mm) for straina:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| O35E | O35ElpxA | |

| Clindamycin (2 μg) | 11.0 ± 0.5 | 15.2 ± 0.5 |

| Fusidic acid (10 mg/ml) | 29.0 ± 0.9 | 34.5 ± 0.5 |

| Novobiocin (5 μg) | 13.8 ± 0.3 | 20.8 ± 0.3 |

| Polymyxin B (300 iu) | 11.5 ± 0.5 | 16.0 ± 0.0 |

| Rifapin (5 μg) | 22.1 ± 0.3 | 33.1 ± 0.5 |

| Vancomycin (5 μg) | <6.0b | 12.2 ± 0.5 |

| Deoxycholate (100 mg/ml) | 22.0 ± 0.9 | 29.3 ± 0.3 |

| Triton X-100 (5% [wt/vol]) | 15.5 ± 0.5 | 40.0 ± 0.9 |

| Tween 20 (5% [vol/vol]) | 11.5 ± 0.5 | 18.5 ± 0.5 |

Sensitivities were assessed by measuring the diameters of the zones of growth inhibition on two axes, and the mean values were calculated. The data represent the averages of three separate experiments ± SD.

No inhibition.

In a bactericidal assay with normal human serum, strain O35E survived at the highest concentration, i.e., 25% of normal human serum. However, 50% of the mutant cells died at 0.5% of normal human serum, and there was no survival at 25% of normal human serum (Fig. 7), indicating reduced resistance of the mutant to the normal human serum.

FIG. 7.

Bactericidal activity of normal human serum against M. catarrhalis wild-type strain O35E (black bars) and mutant O35ElpxA (gray bars). “-” stands for 25% of heat-inactivated normal human serum. The data represent the averages of three independent assays.

In an adherence assay using three human epithelial cell lines, the adherence percentages of the O35ElpxA to Chang and HeLa epithelia were 5.5% ± 0.6% and 7.3% ± 0.6%, respectively, while those of the parental O35E were 54.9% ± 4.9% and 64.6% ± 4.7%, respectively, which represent 9- to 10-fold reductions for the mutant. For A549 epithelia, the adherence percentage of O35ElpxA was 6.9% ± 2.4%, while that of the wild type was 19.3% ± 2.0%, nearly a threefold reduction.

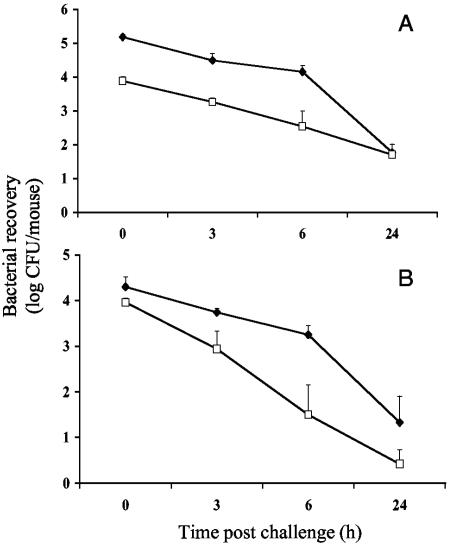

In a murine respiratory clearance model after an aerosol challenge, the number of O35ElpxA cells present in lungs was approximately 20-fold lower than that of parental O35E cells right after the challenge (Fig. 8A). Both mutant and wild-type strains had similar clearance rates at 3 h (76.0% and 79.8%) and at 6 h (95.3% and 90.6%). In contrast, the number of the O35ElpxA cells present in nasopharynx was reduced by only twofold right after the challenge (Fig. 8B) compared to the wild-type strain (P < 0.05). However, the mutant showed accelerated clearance rates relative to the wild type at 3 h (90.6% versus 73.5%; P < 0.01) and 6 h (99.7% versus 91.5%; P < 0.05).

FIG. 8.

Time courses of bacterial recovery in mouse lungs (A) and nasal washes (B) after an aerosol challenge with M. catarrhalis wild-type strain O35E (⧫) and mutant O35ElpxA (□). Each time point represents a geometric mean for six mice.

Antibody responses and protection in mice.

Table 3 shows that both the O35ElpxA and the O35E strains elicited similar levels of serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) against the O35ElpxA cells in ELISA. When the O35E cells were used as a coating antigen in ELISA, there was a tendency of an increase in the antibody levels elicited by the wild-type strain O35E. However, such difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The IgG antibody levels were significantly enhanced by five- to sevenfold when an adjuvant was used for both the wild-type and mutant strains (P < 0.01). In addition, the bactericidal titer elicited by the immunization of mice with O35ElpxA with or without the Ribi adjuvant was comparable to that with the wild type (1:640 versus 1:640 or 1:320 versus 1:160). Furthermore, active immunization of mice with the mutant O35ElpxA resulted in a significant bacterial reduction (77%) in the lungs after an aerosol challenge with the wild-type O35E compared to that of the controls. This level of bacterial reduction was similar to that for the parental O35E (62% reduction).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of murine antibody responses and levels of protection provided by immunization with M. catarrhalis strain O35E and mutant O35ElpxA

| Immunization groupa | Serum geometric mean IgG level (±SD range) as determined by ELISAb | Serum bactericidal titer | Bacterial CFU/lung (±SD range)c | Bacterial reduction (%)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O35E | 630 (427-930)e | 1:160 | ND | ND |

| 475 (269-838)f | ||||

| O35ElpxA | 311 (143-676)e | 1:320 | ND | ND |

| 298 (96-930)f | ||||

| PBS | 1 | <1:5 | ND | ND |

| O35E plus Ribi | 3,217 (1,420-7,284)e | 1:640 | 8,097 (4,113-15,939) | 62.0* |

| 2,494 (1,691-3,677)f | ||||

| O35ElpxA plus Ribi | 1,577 (923-2,695)e | 1:640 | 4,922 (2,568-9,432) | 77.0* |

| 2,149 (1,140-4,053)f | ||||

| Ribi | 1 | <1:5 | 21,037 (14,130-31,319) | 0 |

Mice were immunized subcutaneously with 0.2-ml doses containing 108 CFU of heat-killed strain O35E or O35ElpxA with or without Ribi adjuvant three times at 10-day intervals, and blood samples were collected 2 weeks after the last injection.

Levels of IgG antibodies against whole cells were expressed as geometric mean ELISA units ± SD range for eight mice.

The immunized mice were further challenged with 10 ml (4 × 109 CFU/ml) of the wild-type strain O35E. Mouse lungs were collected for bacterial counts 6 h postchallenge, and the bacterial counts were expressed as geometric mean ± SD range for eight mice. ND, not done.

Compared with the Ribi group; *, P < 0.01 using two-tailed independent Student's t test.

IgG levels were determined by ELISA plates coated with wild-type O35E cells.

IgG levels were determined by ELISA plates coated with mutant O35ElpxA cells.

DISCUSSION

The genetic inactivation of enzymes catalyzing the early steps of LPS or LOS biosynthesis in gram-negative bacteria is usually lethal to the organism (14, 24). To date, only a meningococcal lpxA mutant has been shown to be viable without LOS (33), while further efforts to construct lpxA knockout mutants in N. gonorrhoeae and H. influenzae have failed (40). In this report, we generated an lpxA mutant from another pathogenic bacterial species, M. catarrhalis. All genetic, physicochemical, and biological results suggested that the lpxA homologue of M. catarrhalis, encoding the UDP-GlcNAc acyltransferase, is responsible for the first step in the lipid A biosynthesis of M. catarrhalis LOS. Our data demonstrated that the M. catarrhalis lpxA mutant was viable, even though it completely lacked the LOS structure. It is not clear how the M. catarrhalis lpxA mutant can be viable without LOS. In the meningococcal lpxA mutant, the presence of a capsular polysaccharide is essential for its viability (32). In contrast, there is no confirmed evidence for a detectable capsular polysaccharide structure in M. catarrhalis (2), although another species, Moraxella nonliquefaciens, is reported to have a capsular polysaccharide identical to that of N. meningitidis or E. coli K1 (8). Further work is required to determine how M. catarrhalis can remain viable in the absence of LOS without a capsule.

Although the M. catarrhalis bacterium did not require LOS for viability, the LOS deficiency resulted in alterations in colony morphology, permeability of the outer membrane, and serum resistance. The O35ElpxA colonies were large, flat, and transparent, and the altered opacity of the lpxA mutant was consistent with results for H. influenzae (42) and N. meningitidis (3), in which changes in LOS structure caused differences in colony opacities. The mutant O35ElpxA was very susceptible to most hydrophobic reagents. This may be caused by the lack of a continuous LOS layer in the outer membrane leaflet and the resultant compensatory presence of glycerophospholipid in this leaflet. This creates glycerophospholipid bilayers or patches in the outer membrane that allow the diffusion of hydrophobic solutes. The mutant was also susceptible to a hydrophilic glycopeptide that was normally excluded by the intact enterobacterial outer membrane, indicating that the outer membrane of the lpxA mutant was probably fragile and transiently ruptured due to lack of the LOS molecule (39). In addition, the lpxA mutant was highly sensitive to the bactericidal activity of a normal human serum pool compared to the parental strain and more sensitive to the normal human serum than a kdtA-deficient mutant with a truncated LOS molecule with a lipid A structure alone was (29). These results suggest that the permeability change on the outer membrane barrier of the lpxA mutant may increase its sensitivity to the complement killing of the serum.

Since M. catarrhalis is a respiratory tract mucosal pathogen, it is possible to evaluate its virulence by observing its interaction with host epithelial cells in vitro and in an aerosol challenge mouse model. The attachment of microbes to host epithelial cells represents the first step in the pathogenesis of microbial infections, with the target specificity being defined by precise adhesin-receptor interactions (36). In our study, the attachment to human epithelia by the lpxA mutant showed nearly a 10-fold reduction in Chang (conjunctival) or HeLa (cervix) cells but nearly a 3-fold reduction in A549 (lung) cells. These data imply that the mutant had reduced adherence to different types of epithelial cells with various affinities. In the mouse challenge model, the lpxA mutant showed reduced rates of attachment to mouse respiratory tracts, especially in the lungs (a 20-fold reduction) immediately after a bacterial challenge. Following the challenge, however, the mutant was rapidly cleared from the nasopharynx but presented a clearance rate in the lungs similar to that of the parental strain. It is not clear whether these changes in the mutant are caused by a direct loss of the LOS moiety on the outer membrane that might result in a deficiency in its interaction with the host cells and/or an increase in its sensitivity to murine complement-mediated killing or by an indirect effect on surface display or expression of the membrane molecules, such as adhesin molecules. Nevertheless, the involvement of the LOS in the ability of M. catarrhalis to attach to the human epithelial cell lines and to survive in vivo in the mouse clearance model raises the possibility that the LOS might be essential for the virulence of the organism in the pathogenesis of M. catarrhalis infections.

Since the LOS-deficient mutant, O35ElpxA, showed attenuated endotoxic reactivity in a LAL assay and reduced virulence features, as suggested by reduced resistance to normal human serum, reduced adherence to human epithelia, and increased clearance in a mouse challenge model, it might be used as a vaccine candidate for further investigation. Recent studies involving vaccine antigens have shown that multiple bacterial components, such as OMPs, outer membrane vesicles, or whole cells, might be preferred, given the ability of the bacteria to vary surface components in response to immunologic pressures (23, 27). The presence of LOS or the difficulty in removing LOS is one major obstacle in developing those vaccine candidates. Construction of a mutant without LOS may help to overcome this problem. However, the immunogenicity of whole cells or of outer membrane components of the meningococcal LOS-deficient mutant was greatly reduced (35). In contrast, the M. catarrhalis lpxA mutant elicited levels of antibodies with bactericidal activity similar to those of its parental strain. It has been reported that bacterial LPS can function as an adjuvant and enhance the immune response to a particular antigen (22). It is unclear whether there may exist an adjuvant component other than LOS in the cell walls of M. catarrhalis that can functionally replace the LOS deficiency or whether other surface components, such as OMPs, present on the LOS-null mutant simply may be as immunogenic as the wild-type strain. In addition, when the Ribi adjuvant was used, the antibody levels elicited by the mutant O35ElpxA and strain O35E were further enhanced by five- to sevenfold. Importantly, the bactericidal titer and the level of protection against the parental O35E provided by immunization with the mutant O35ElpxA were comparable to those of the parental O35E. These results indicated that the mutant bacterium without LOS might be used as a potential vaccine against M. catarrhalis. Future studies are planned and necessary to further access the immunological properties and heterologous protection of the mutant strain and its OMPs or outer membrane vesicles.

In summary, an lpxA knockout mutant is generated in M. catarrhalis strain O35E. The M. catarrhalis LOS is not essential for bacterial survival, though it may be critical in the bacterial virulence. A completely LOS-deficient M. catarrhalis strain is attenuated and highly immunogenic.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eric J. Hansen for providing strain O35E, Shengqing Yu for technical advice in bactericidal assays, and Robert Morell and Yandan Yang for critical help in DNA sequencing.

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIDCD. The structural analysis was supported by a grant from the Department of Energy (DE-FG09-93ER20097) to the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center.

Editor: J. T. Barbieri

REFERENCES

- 1.Aebi, C., E. R. Lafontaine, L. D. Cope, L. Latimer, S. L. Lumbley, G. H. McCracken, Jr., and E. J. Hansen. 1998. Phenotypic effect of isogenic uspA1 and uspA2 mutations on Moraxella catarrhalis 035E. Infect. Immun. 66:3113-3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed, K., N. Rikitomi, A. Ichinose, and K. Matsumoto. 1991. Possible presence of a capsule in Branhamella catarrhalis. Microbiol. Immunol. 35:361-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albiger, B., L. Johansson, and A. B. Jonsson. 2003. Lipooligosaccharide-deficient Neisseria meningitidis shows altered pilus-associated characteristics. Infect. Immun. 71:155-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson, M. S., and C. R. Raetz. 1987. Biosynthesis of lipid A precursors in Escherichia coli. A cytoplasmic acyltransferase that converts UDP-N-acetylglucosamine to UDP-3-O-(R-3-hydroxymyristoyl)-N-acetylglucosamine. J. Biol. Chem. 262:5159-5169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bandak, S. I., M. R. Turnak, B. S. Allen, L. D. Bolzon, D. A. Preston, S. K. Bouchillon, and D. J. Hoban. 2001. Antibiotic susceptibilities among recent clinical isolates of Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis from fifteen countries. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 20:55-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campagnari, A. A., T. F. Ducey, and C. A. Rebmann. 1996. Outer membrane protein B1, an iron-repressible protein conserved in the outer membrane of Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis, binds human transferrin. Infect. Immun. 64:3920-3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catlin, B. W. 1990. Branhamella catarrhalis: an organism gaining respect as a pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 3:293-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devi, S. J., R. Schneerson, W. Egan, W. F. Vann, J. B. Robbins, and J. Shiloach. 1991. Identity between polysaccharide antigens of Moraxella nonliquefaciens, group B Neisseria meningitidis, and Escherichia coli K1 (non-O acetylated). Infect. Immun. 59:732-736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doyle, W. J. 1989. Animal model of otitis media: other pathogens. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 81(Suppl.):S45-S47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edebrink, P., P. E. Jansson, M. M. Rahman, G. Widmalm, T. Holome, M. Rahman, and A. Weintraub. 1994. Structural studies of the O-polysaccharide from the lipopolysaccharide of Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis serotype A (strain ATCC 25238). Carbohydr. Res. 257:269-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards, K. J., S. Allen, B. W. Gibson, and A. A. Campagnari. 2005. Characterization of a cluster of three glycosyltransferase enzymes essential forMoraxella catarrhalis lipooligosaccharide assembly. J. Bacteriol. 187: 2939-2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fomsgaard, J. S., A. Fomsgaard, N. Hoiby, B. Bruun, and C. Galanos. 1991. Comparative immunochemistry of lipopolysaccharides from Branhamella catarrhalis strains. Infect. Immun. 59:3346-3349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galanos, C., O. Luderitz, and O. Westphal. 1969. A new method for the extraction of R lipopolysaccharides. Eur. J. Biochem. 9:245-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galloway, S. M., and C. R. Raetz. 1990. A mutant of Escherichia coli defective in the first step of endotoxin biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 265:6394-6402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gronow, S., and H. Brade. 2001. Lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis: which steps do bacteria need to survive? J. Endotoxin Res. 7:3-23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu, X. X., J. Chen, S. J. Barekamp, J. B. Robbins, C. M. Tsai, D. J. Lim, and J. Battey. 1998. Synthesis and characterization of lipooligosaccharide-based conjugates as vaccine candidates for Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis. Infect. Immun. 66:1891-1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helminen, M. E., I. Maciver, J. L. Latimer, L. D. Cope, G. H. McCracken, Jr., and E. J. Hansen. 1993. A major outer membrane protein of Moraxella catarrhalis is a target for antibodies that enhance pulmonary clearance of the pathogen in an animal model. Infect. Immun. 61:2003-2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoban, D. J., G. V. Doern, A. C. Fluit, M. Roussel-Delvallez, and R. N. Jones. 2001. Worldwide prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis in the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997-1999. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:S81-S93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holme, T., M. Rahman, P. E. Jansson, and G. Widmalm. 1999. The lipopolysaccharide of Moraxella catarrhalis: structural relationships and antigenic properties. Eur. J. Biochem. 265:524-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu, W. G., J. Chen, F. M. Collins, and X. X. Gu. 2000. An aerosol challenge mouse model for Moraxella catarrhalis. Vaccine 18:799-804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu, W. G., J. Chen, J. C. McMichael, and X. X. Gu. 2001. Functional characteristics of a protective monoclonal antibody against serotype A and C lipooligosaccharides from Moraxella catarrhalis. Infect. Immun. 69:1358-1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson, A. G., G. Gaines, and M. Landy. 1956. Studies on the O antigen of Salmonella typhosa. V. Enhancement of antibody response to protein antigens by the purified lipopolysaccharide. J. Exp. Med. 103:225-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karalus, R., and A. Campagnari. 2000. Moraxella catarrhalis: a review of an important human mucosal pathogen. Microbes Infect. 2:547-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly, T. M., S. A. Stachula, C. R. Raetz, and M. S. Anderson. 1993. The firA gene of Escherichia coli encodes UDP-3-O-(R-3-hydroxymyristoyl)-glucosamine N-acyltransferase. The third step of endotoxin biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 268:19866-19874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luke, N. R., S. Allen, B. W. Gibson, and A. A. Campagnari. 2003. Identification of a 3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonic acid biosynthetic operon in Moraxella catarrhalis and analysis of a KdsA-deficient isogenic mutant. Infect. Immun. 71:6426-6434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masoud, H., M. B. Perry, and J. C. Richards. 1994. Characterization of the lipopolysaccharide of Moraxella catarrhalis. Structural analysis of the lipid A from M. catarrhalis serotype A lipopolysaccharide. Eur. J. Biochem. 220: 209-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McMichael, J. C. 2000. Progress toward the development of a vaccine to prevent Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis infections. Microbes Infect. 2:561-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy, T. F. 1996. Branhamella catarrhalis: epidemiology, surface antigenic structure, and immune response. Microbiol. Rev. 60:267-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng, D., B. P. Choudhury, R. S. Petralia, R. W. Carlson, and X. X. Gu. 2005. Roles of 3-deoxy-d-manno-2-octulosonic acid transferase from Moraxella catarrhalis in lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis and virulence. Infect. Immun. 73:4222-4230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raetz, C. R., and C. Whitfield. 2002. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71:635-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schnaitman, C. A., and J. D. Klena. 1993. Genetics of lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in enteric bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 57:655-682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steeghs, L., H. de Cock, E. Evers, B. Zomer, J. Tommassen, and P. van der Ley. 2001. Outer membrane composition of a lipopolysaccharide-deficient Neisseria meningitidis mutant. EMBO J. 20:6937-6945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steeghs, L., R. den Hartog, A. den Boer, B. Zomer, P. Roholl, and P. van der Ley. 1998. Meningitis bacterium is viable without endotoxin. Nature 392:449-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steeghs, L., M. P. Jennings, J. T. Poolman, and P. van der Ley. 1997. Isolation and characterization of the Neisseria meningitidis lpxD-fabZ-lpxA gene cluster involved in lipid A biosynthesis. Gene 190:263-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steeghs, L., B. Kuipers, H. J. Hamstra, G. Kersten, L. van Alphen, and P. van der Ley. 1999. Immunogenicity of outer membrane proteins in a lipopolysaccharide-deficient mutant of Neisseria meningitidis: influence of adjuvants on the immune response. Infect. Immun. 67:4988-4993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.St. Geme, J. W. 1997. Bacterial adhesins: determinants of microbial colonization and pathogenicity. Adv. Pediatr. 44:43-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai, C. M., and C. E. Frasch. 1982. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 119:115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tzeng, Y. L., A. Datta, V. K. Kolli, R. W. Carlson, and D. S. Stephens. 2002. Endotoxin of Neisseria meningitidis composed only of intact lipid A: inactivation of the meningococcal 3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonic acid transferase. J. Bacteriol. 184:2379-2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaara, M. 1993. Antibiotic-supersusceptible mutants of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:2255-2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Ley, P., and L. Steeghs. 2003. Lessons from an LPS-deficient Neisseria meningitidis mutant. J. Endotoxin Res. 9:124-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verduin, C. M., C. Hol, A. Fleer, H. van Dijk, and A. van Belkum. 2002. Moraxella catarrhalis: from emerging to established pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:125-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weiser, J. N., and N. Pan. 1998. Adaptation of Haemophilus influenzae to acquired and innate humoral immunity based on phase variation of lipopolysaccharide. Mol. Microbiol. 30:767-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.West, N. P., H. Jungnitz, J. T. Fitter, J. D. McArthur, C. A. Guzman, and M. J. Walker. 2000. Role of phosphoglucomutase of Bordetella bronchiseptica in lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis and virulence. Infect. Immun. 68:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.York, W. S., A. G. Darvill, M. McNeil, T. T. Stevenson, and P. Albersheim. 1985. Isolation and characterization of plant cell walls and cell wall components. Methods Enzymol. 118:3-40. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zaleski, A., N. K. Scheffler, P. Densen, F. K. Lee, A. A. Campagnari, B. W. Gibson, and M. A. Apicella. 2000. Lipooligosaccharide Pk (Galα1-4Galβ1-4Glc) epitope of Moraxella catarrhalis is a factor in resistance to bactericidal activity mediated by normal human serum. Infect. Immun. 68:5261-5268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]