Abstract

We have previously shown that enterotoxigenic invasion protein A (Tia), a 25-kDa outer membrane protein encoded on an apparent pathogenicity island of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) strain H10407, mediates attachment to and invasion into cultured human gastrointestinal epithelial cells. The epithelial cell receptor(s) for Tia has not been identified. Here we show that Tia interacts with cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Recombinant E. coli expressing Tia mediated invasion into wild-type epithelial cell lines but not invasion into proteoglycan-deficient cells. Furthermore, wild-type eukaryotic cells, but not proteoglycan-deficient eukaryotic cells, attached to immobilized polyhistidine-tagged recombinant Tia (rTia). Binding of epithelial cells to immobilized rTia was inhibited by exogenous heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans but not by hyaluronic acid, dermatan sulfate, or chondroitin sulfate. Similarly, pretreatment of eukaryotic cells with heparinase I, but not pretreatment of eukaryotic cells with chrondroitinase ABC, inhibited attachment to rTia. In addition, we also observed heparin binding to both immobilized rTia and recombinant E. coli expressing Tia. Heparin binding was inhibited by a synthetic peptide representing a surface loop of Tia, as well as by antibodies directed against this peptide. Additional studies indicated that Tia, as a prokaryotic heparin binding protein, may also interact via sulfated proteoglycan molecular bridges with a number of mammalian heparan sulfate binding proteins. These findings suggest that the binding of Tia to host epithelial cells is mediated at least in part through heparan sulfate proteoglycans and that ETEC belongs on the growing list of pathogens that utilize these ubiquitous cell surface molecules as receptors.

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) strains remain a formidable cause of diarrheal disease and are a leading cause of infant mortality in developing countries. This heterogeneous group of pathogens, distinguished by their ability to cause diarrhea through the production of heat-labile and/or heat-stable enterotoxins, collectively account for an estimated 200 million episodes of diarrheal illness and more than three-quarters of a million deaths annually (2). These organisms have occasionally been identified as the causes of food-borne outbreaks in industrialized countries (1, 41) and are still the most common cause of diarrhea in travelers (44).

Colonization of the small intestine is a critical element in the pathogenesis of enterotoxigenic disease and is mediated, at least in part, by a heterogeneous group of antigenically distinct plasmid-encoded adhesins referred to as colonization factor antigens or coli surface antigens. At least 20 established or putative colonization factors have been identified in human ETEC strains to date (11). This heterogeneity has hampered ETEC vaccine development efforts. Previous studies have demonstrated that immunity directed against a single colonization factor antigen provides protection against strains expressing homologous molecules but not against strains expressing heterologous molecules (33). In recent studies of ETEC infections in Egypt, only 23% of ETEC isolates expressed an identifiable colonization factor (40). Studies to elucidate additional factors required for epithelial cell attachment by ETEC are therefore warranted, and such studies may provide new avenues for vaccine development.

We have recently demonstrated that enterotoxigenic invasion protein A (Tia), a 25-kDa outer membrane protein, is encoded on a 46-kb pathogenicity island of prototypical ETEC strain H10407 (24). Tia mediates attachment to and invasion into cultured epithelial cells of gastrointestinal origin (23). However, the molecular events involved in the interactions, as well as the specific epithelial cell surface target receptors for Tia, have not been determined.

A diverse group of bacterial, viral, and protozoan pathogens have been shown to interact with eukaryotic cells through surface proteoglycans (42), particularly heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) (5). These cell surface glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) are abundant on eukaryotic cells and may facilitate the initial interaction with the host that is required for an organism to bind to other molecular targets (26). Duensing et al. have suggested that a number of bacteria utilize binding to sulfated proteoglycans as a molecular bridge to interact with a diverse array of mammalian heparin binding proteins (MHBPs) that collectively promote parasitism (18).

Tia exhibits structural homology with a family of proteins predicted to form an eight-stranded β-barrel in the outer membrane. The group includes a number of virulence factors, including Ail (4, 37) and the opacity-associated (Opa) proteins of Neisseria, to which Tia is most closely related (3). The Opa adhesins are a complex group of outer membrane proteins that are variably expressed in Neisseria. The OpaA protein of Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain MS11 has previously been shown to interact with HSPG (12), whereas the majority of Opa proteins utilize carcinoembryonic antigen-related cellular adhesion molecules (7, 13, 51). In this study, we found that the Tia-mediated interaction with host epithelial cells occurs, at least in part, through association with cell surface sulfated proteoglycans and that, similar to OpaAMS11, Tia may also participate in more complex interactions involving eukaryotic heparin binding proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Heparin (sodium salt), heparan sulfate, hyaluronic acid, chondroitin sulfate B (dermatan sulfate), chondroitin sulfate C, purified human vitronectin, bovine fibronectin, and heparin-albumin-biotin were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). Biotinylated proteins were prepared by incubation with Sulfo-NHS-LC biotin (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, Ill.) at a final biotin concentration of 500 μg/ml for 45 min at room temperature and then dialyzed overnight against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing leupeptin (1 μg/ml), pepstatin (1 μg/ml), and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (1 mM).

Bacterial strains, plasmids, cell lines, and growth conditions.

Mammalian cell lines HCT-8 and CHO-K1 and CHO cell lines defective in proteoglycan synthesis, pgsA-745 and pgsD-677 (34), were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Table 1). HCT-8 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The CHO cell lines were grown in Ham's F-12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. In experiments in which β-d-xylosides were used to inhibit glycosaminoglycan formation, cells were grown in the presence of 1 mM p-nitrophenyl-β-d-xylopyranoside (Sigma), and then the media were replaced with fresh media without inhibitor before the cells were used. AAEC191A, which was the E. coli host background strain used in Tia-mediated adherence and internalization studies, is a ΔrecA Δfim derivative of E. coli K-12 that was previously described by Blomfield et al. (8). E. coli HB101 carrying pRI203, which contains the Yersinia invasin gene cloned by Isberg et al. (30), was supplied by Dennis Kopecko. Plasmid pET185 contains the tia gene cloned into the pHG165 vector plasmid (47), as previously described (23).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and eukaryotic cell lines used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or cell line | Description | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli AAEC191A | Δfim ΔrecA derivative of E. coli K-12 | 8 |

| E. coli HB101 | supE44 hsdS20 (r−B m−B) recA13 ara-14 proA2 lacY1 galK2 rpsL20 xyl-5 mtl-1 | 9 |

| E. coli DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 (φ80lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | 28 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pHG165 | pBR322 copy number derivative of pUC8, ColE1 replication origin | 51 |

| pET185 | tia locus cloned into pHG165 | 23 |

| pRI203 | Cloned invasin gene | 32 |

| pQE-30.tia | Bases 76 to 753 of tia cloned into six-His tag fusion expression plasmid pQE-30 | This study |

| Cell lines | ||

| HCT-8 | Ileocecal adenocarcinoma | 53 |

| CHO-K1 | Wild-type Chinese hamster ovary | 33 |

| pgsA-745 | Xylosyltransferase-deficient CHO mutant, lacks GAG production | 20 |

| pgsD-677 | N-Acetylglucosaminyl transferase- and gluconosyltransferase-deficient CHO mutant, no heparan sulfate, threefold-higher levels of chondroitin sulfate | 20, 37 |

Cell binding to Tia-coated surfaces.

Binding of epithelial cells to purified recombinant Tia (rTia) was studied by using an assay similar to that described by Isberg and Leong (29). Briefly, wells of a 96-well microtiter plate were incubated overnight at 4°C with rTia or control protein in 0.05 M carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) at a final protein concentration of 5 μg/ml. On the morning of the assay, the wells were washed three times with PBS (pH 7.4) and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 1 h at 37°C. Epithelial cells were dispersed from semiconfluent monolayers with PBS containing 2 mM EDTA, and this was followed by two washes with cell binding buffer (RPMI 1640, 0.1% BSA, 0.3 mg of glutamine per ml). Exogenous GAGs or GAG lyases were added to cells after resuspension in cell binding buffer, and this was followed by incubation for 1 h at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 prior to binding to rTia. Cells were resuspended in cell binding buffer to a density of approximately 1 × 105 cells/ml, 100-μl aliquots were added to wells, and the preparations were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. The microtiter plates were washed by gentle submersion in PBS, followed by aspiration of PBS containing dislodged cells. The relative number of attached cells was then determined by using an assay for the eukaryotic enzyme hexosaminidase (32). The cells that remained attached to the wells were incubated with 60 μl of hexosaminidase substrate buffer containing 7.5 mM p-nitrophenyl-N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminide and 0.1% Triton X-100 in 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 5.0) for 1 h at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. The reaction was then terminated, and color was developed by adding 90 μl of stop buffer containing 50 mM glycine and 5 mM EDTA (pH 10.4). Absorbance was measured at 405 nm.

Invasion and adherence assays.

Invasion and adherence assays were carried out as previously described (23). Briefly, bacteria were grown to the mid-logarithmic phase and added to monolayers at a multiplicity of infection of approximately 10:1. The invasion data below reflect the percentages of the initial inoculum recovered after the monolayers were washed and incubated with medium containing gentamicin (100 μg/ml) for 2 h and the eukaryotic cells were lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100 to release the intracellular organisms. The cell-associated bacteria were the organisms recovered after washing and lysis of the monolayers in the absence of gentamicin. In experiments involving exogenous GAG or serum, the additional components were added at the concentrations indicated below approximately 30 min prior to inoculation of the monolayers with bacteria. To assess the contribution of serum or its components to the bacterial interaction with host cells, monolayers were washed on the morning of the experiment, and the medium was replaced with serum-free RPMI 1640 supplemented with glutamine.

Preparation of purified rTia protein.

Bases 76 to 753 of the tia gene, which lacks the signal peptide coding region, were amplified from H10407 genomic DNA by PCR using primers tia.BamHI.76 (5′-CGGGATCCGATGAGAGCAAAACAGGCTT-3′) and tia.KpnI.753 (5′-GGGGTACCGAAATGATAAGTTACCCC-3′). The amplicon was then directionally cloned into the BamHI and KpnI sites of polyhistidine fusion expression plasmid pQE-30 (Qiagen). The resulting recombinant plasmid, pQE-30.tia, was sequenced to ensure that the construct was in frame. Following expression in E. coli M15 (50) carrying the pREP4 repressor plasmid (21), the polyhistine-tagged rTia protein was purified by nickel affinity chromatography from urea extracts. Aliquots of the purified protein were kept at −80°C prior to use.

Production of anti-Tia antisera.

To prepare anti-Tia antisera, two New Zealand White rabbits weighing approximately 2 kg were injected with 100 μg of rTia mixed 1:2 with complete Freund's adjuvant; this was followed by additional injections after 4 and 8 weeks. Sera were harvested at time zero and after 12 weeks. To remove cross-reacting antibodies, anti-Tia sera were preabsorbed against E. coli proteins by using an immobilized E. coli lysate column (Pierce). The sera were kept at 4°C. Rabbit antisera were also raised against sp.tia76-94, a synthetic peptide representing a putative surface-exposed region of Tia, which was first coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (52); 100 μg of the peptide-keyhole limpet hemocyanin conjugate was injected by using the protocol described above.

Binding of eukaryotic proteins to Tia.

To demonstrate that heparin binds to Tia, triplicate wells of a 96-well plate were coated with either rTia or BSA in carbonate buffer at concentrations ranging from 1.25 to 5 pmol/ml. After binding overnight at 4°C, the plates were washed with PBS and blocked with 10% BSA in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20; then heparin-albumin-biotin (10 μg/ml) in blocking buffer was added. A duplicate set of wells containing the substrates described above was treated with blocking buffer alone. After incubation for 2 h at 37°C, the plate was washed, and binding was detected by using a 1:4,000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled mouse monoclonal anti-biotin antibody (Zymed) in blocking buffer and then the 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories. Absorbance at 655 nm was determined. To obtain heparin binding to Tia in its native conformation, overnight cultures of AAEC191A(pET185) and AAEC191A(pHG165) were diluted in Luria-Bertani broth containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and grown to the mid-log phase. The bacteria were washed with PBS, resuspended in PBS containing 1% BSA and biotinylated heparin at a final concentration of 5 μg/ml, incubated on a rotating disk for 30 min at 37°C, and then washed extensively with PBS to remove unbound heparin. To inhibit the interaction of heparin with Tia on the bacterial surface, either synthetic peptides or antibodies raised against synthetic peptides were used. In peptide inhibition studies, bacterial pellets were first resuspended in PBS containing sp.tia76-94 (AVGYDFYQHYNVPVRTEVEC) or a control peptide, sp.sls10-30 (FSIATGSGNSQGGSYTPGKC) (supplied by James Dale's laboratory), at final concentrations of 0.4 to 4 pmol/liter. For antibody inhibition studies, pellets were resuspended in PBS containing 1:10 dilutions of either antipeptide or preimmune sera. Resuspended pellets were rotated at 37°C for 30 min prior to washing and incubation with biotinylated heparin as described above. Bacterial pellets containing bound proteins were boiled in 1× Laemmli buffer containing Benzonase, and this was followed by separation by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (31). Proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and biotinylated proteins were detected by using streptavidin-HRP and a chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce Supersignal West Pico).

Biotinylation of normal human serum (NHS) (provided by James Dale's laboratory), human vitronectin, and bovine fibronectin was carried out as described above. Bacteria were then resuspended in 950 μl of PBS containing 1% BSA and 50 μl of biotinylated NHS or vitronectin and fibronectin at final concentrations of approximately 25 μg/ml. The bacterial suspensions were then rotated at 37°C for 1 h and washed to remove unbound proteins. Binding of unlabeled vitronectin to E. coli recombinants expressing Tia was demonstrated by both immunofluorescence and immunoblotting assays. In the immunofluorescence assays, bacteria were incubated first with heparin (5 μg/ml) in PBS containing 1% BSA. After three washes with PBS, the bacteria were incubated with unlabeled purified human vitronectin (final concentration, 25 μg/ml) in PBS containing 1% BSA for 1 h. The bacteria were washed, incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-human vitronectin antisera (Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.) for 1 h, and then incubated with AlexaFluor 594-labeled goat anti-rabbit antibodies and washed. Aliquots (10 μl) of the bacteria were placed on glass slides, air dried, and mounted by using Prolong antifade reagent (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.). The slides were allowed to dry overnight in the dark and were viewed the following morning with a Zeiss Axiophot fluorescence microscope. In the immunoblot experiments, vitronectin was bound to bacteria as described above, and bound proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose, and detected by using anti-vitronectin antisera followed by HRP-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G Fc (1:60,000).

RESULTS

Optimal interaction of Tia with target epithelial cells requires production of eukaryotic cell surface GAGs.

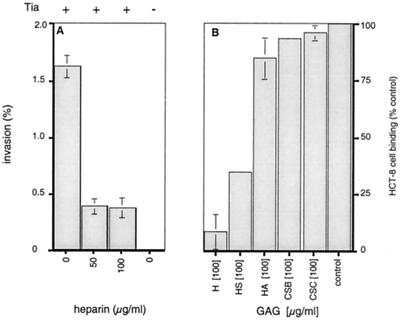

Both Tia and members of the Opa family of outer membrane proteins have been implicated in directing bacterial attachment and internalization. The structural homology exhibited by Tia and the members of the Opa family suggests that these processes may involve binding to similar receptors. To begin to test this hypothesis, Tia-mediated internalization was assessed in the presence and in the absence of exogenously added GAGs. Addition of heparin to epithelial cell monolayers resulted in a marked decrease in Tia-dependent entry into HCT-8 cells (Fig. 1A), suggesting that Tia might interact with sulfated cell surface proteoglycans. To further assess the nature of this potential interaction, the abilities of a variety of soluble GAGs to inhibit binding of HCT-8 epithelial cells to immobilized rTia were determined. Both heparin and the less highly sulfated GAG heparan sulfate inhibited binding of HCT-8 cells to rTia (Fig. 1B). In contrast, addition of other soluble GAGs resulted in little or no inhibition, suggesting that Tia may interact specifically with HSPGs.

FIG. 1.

Exogenous GAGs inhibit Tia-host cell interactions. (A) Heparin inhibits Tia-mediated invasion of HCT-8 epithelial cells by DH5α(pET185) (Tia+ recombinant). Tia− control wells contained the DH5α(pHG165) vector control strain. (B) Addition of heparan-sulfated GAGs (H, heparin; HS, heparan sulfate) inhibited interaction of HCT-8 cells with immobilized rTia, whereas addition of other GAGs (HA, hyaluronic acid; CSB, chondroitin sulfate B; CSC, chondroitin sulfate C) did not inhibit binding. The number of cells bound to rTia was determined by measuring the eukaryotic hexosaminidase enzyme content. Values were determined relative to the binding of untreated cells (control). The error bars indicate standard deviations. The value for background binding to BSA substrate was subtracted from the values shown. (Background binding accounted for less than 1% of the positive control value.)

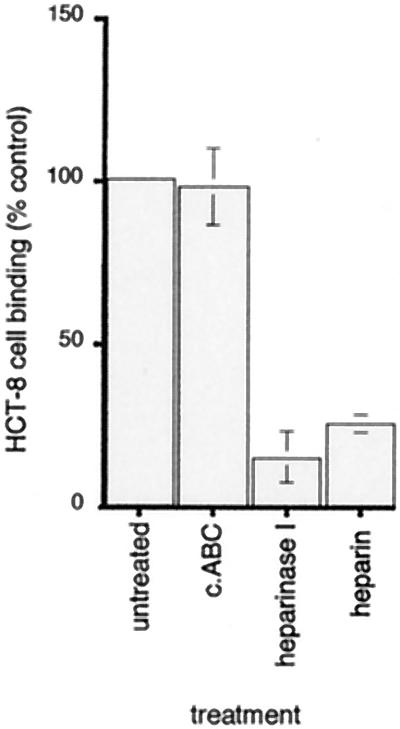

To further investigate the role of different GAGs in the interaction of epithelial cells with immobilized Tia, HCT-8 cells were treated with either heparinase I or chondroitinase ABC, which cleaves chondroitin sulfate A, chondroitin sulfate B, and chondroitin sulfate C. As shown in Fig. 2, treatment of HCT-8 cells with heparinase resulted in a decrease in binding of the cells to rTia comparable to the decrease seen when exogenous heparin was added. Conversely, pretreatment of cells with the chondroitin sulfate-specific endoglycosidase had no effect on attachment of cells to rTia.

FIG. 2.

Enzymatic removal of GAG residues with the heparin-specific GAG lyase heparinase I inhibits binding of HCT-8 intestinal epithelial cells to immobilized rTia, whereas pretreatment of cells with chrondroitinase ABC (c.ABC) has no effect. The results are expressed as percentages of treated and untreated HCT-8 cells bound, as determined by assaying for hexosaminidase in attached cells. The error bars indicate standard deviations. Results obtained with GAG lyase are compared with results obtained after preincubation of cells with exogenous heparin. The value for nonspecific binding of HCT-8 cells to BSA substrate was subtracted from the values shown. (Background binding accounted for less than 1% of the positive control value.)

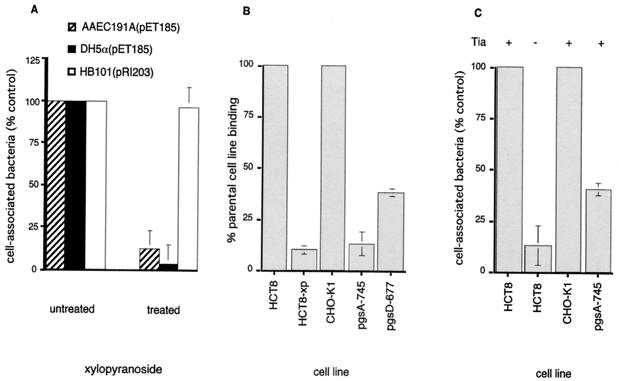

Additional experiments were performed to study the potential interaction between Tia and host cell HSPGs by using eukaryotic cells with a variety of defects in GAG biosynthesis. First, HCT-8 cells were grown in media containing β-d-xylopyranosides. These compounds divert GAG synthesis away from core proteins, which results in production of underglycosylated surface proteoglycans (42). As shown in Fig. 3A, the Tia-mediated bacterial interaction with host cells was markedly diminished when cells were treated with this inhibitor, but the interaction of recombinant E. coli HB101(pRI203) expressing the unrelated invasin molecule was not affected. Similar results were obtained when tia was expressed in an E. coli host background, such as DH5α, which also makes type I fimbriae (Fig. 3A). Treatment of HCT-8 cells with xylopyranosides resulted in a significant decrease in the ability of these cells to bind to immobilized rTia. Wild-type CHO-K1 cells adhered to rTia (Fig. 3B) and permitted Tia-mediated bacterial uptake and attachment (Fig. 3C). However, this was not true of mutant CHO cells with defects in enzymes required for proteoglycan biosynthesis. Neither CHO xylosyltransferase mutants (such as pgsA-745), which lack heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate, nor N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase mutants (such as pgsD-677), which produce excess chondroitin sulfate but no HSPG, bound to rTia as effectively as the wild-type CHO cells. (Neither the mutant nor parental cell lines exhibited significant binding to BSA control wells in these experiments.) Similarly, cells defective in proteoglycan synthesis had a decreased capacity for Tia-mediated bacterial attachment and uptake (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Optimal interaction of Tia with target epithelial cells requires production of eukaryotic cell surface GAGs. (A) Effect of xylopyranoside, an inhibitor of proteoglycan synthesis, on Tia-mediated interaction with HCT-8 cells. The values are the numbers of cell-associated bacteria (both adherent and internalized) as determined by lysis of monolayers 2 h after infection. Neither DH5α(pET185) (Fim+) nor AAEC191A(pET185) (Fim−) could efficiently interact with xylopyronoside-treated HCT-8 host cells; however, this had no effect on the interaction of HB101 (Fim−) bearing the cloned invasin gene on recombinant plasmid pRI203. (B) Binding of GAG-deficient cells to immobilized rTia. The values are percentages of bound xylopyranoside-treated HCT-8 cells (HCT8-xp) or mutant cells (pgsA-745, pgsD-677) relative to the number of bound parental cells (HCT8, CHO-K1). (C) Tia-mediated interaction with HCT-8 cells (HCT8), wild-type cells (CHO-K1), and GAG synthesis mutant cells (pgsA-745). Tia+ indicates that Tia recombinant strain AAEC191A(pET185) was used, whereas Tia− indicates that negative control strain AAEC191A(pHG165) was used.

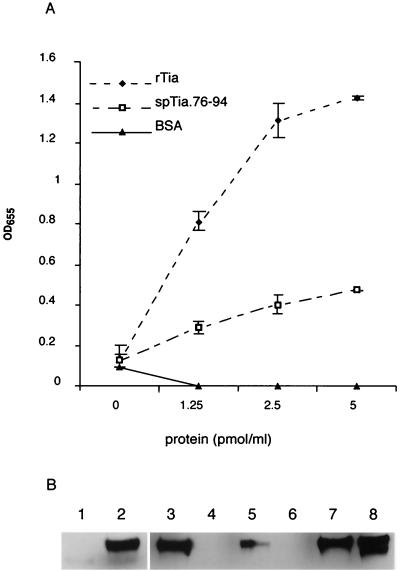

Tia is a prokaryotic heparin binding protein.

To obtain further evidence of Tia's interactions with HSPGs, we performed experiments to examine the ability of rTia to bind directly to heparin. As shown in Fig. 4A, biotinylated heparin bound to full-length immobilized rTia and, to a lesser extent, to the synthetic peptide sp.tia76-94 representing a potential surface-exposed region of the Tia molecule. To investigate heparin binding with Tia in its native conformation, we used AAEC191A(pET185), an E. coli recombinant expressing Tia. AAEC191A(pET185) bound biotinylated heparin (Fig. 4B, lane 2), whereas no binding occurred with the strain containing the control plasmid, AAEC191A(pHG165) (Fig. 4B, lane 1). To determine whether surface epitopes of Tia which direct epithelial cell invasion are also involved in heparin binding, we performed inhibition experiments with sp.tia76-94. When added to HCT-8 epithelial cell monolayers immediately prior to inoculation with bacteria, sp.tia76-94 (final concentration, 100 μg/ml) reduced invasion of DH5α(pET185) by 80% ± 3.4%. This peptide is nearly identical to the peptide used in the study of Tia topology of Mammarappallil and Elsinghorst, which showed that this region participates in the Tia-mediated interaction with epithelial cells (36). sp.tia76-94 (Fig. 4, lanes 5 and 6), as well as antibodies raised against this peptide (Fig. 4, lane 4), inhibited interaction of biotinylated heparin with bacteria expressing rTia. An unrelated control peptide (Fig. 4, lanes 7 and 8) or preimmune rabbit sera (Fig. 4, lane 3) had no effect on the binding of heparin to Tia. Together, these data suggest that putative surface epitopes of Tia that direct attachment to epithelial cells are similar, if not identical, to the epitopes involved in Tia-HSPG interactions.

FIG. 4.

Tia functions as a prokaryotic heparin binding protein. (A) Binding of heparin-albumin-biotin to immobilized rTia or to a Tia synthetic peptide (sp.tia76-94). Triplicate wells of a 96-well plate were coated with different concentrations of either rTia, sp.tia76-94, or BSA. Binding of heparin-albumin-biotin to substrate was detected with HRP-labeled mouse monoclonal anti-biotin antibody. The absorbance values are averages based on the data for triplicate wells minus the background absorbance values obtained from nonspecific binding of antibody to substrate alone (in the absence of heparin-albumin-biotin). The error bars indicate standard deviations. OD655, optical density at 655 nm. (B) Binding of heparin to rTia in its native conformation. Binding of biotinylated heparin to an E. coli recombinant carrying the vector control plasmid, AAEC195(pHG165) (lane 1), or to a strain bearing the tia expression plasmid, AAEC195(pET185) (lanes 2 to 8), was determined. Antibodies raised against the Tia synthetic peptide sp.tia76-94 inhibited binding of heparin (lane 4), whereas preimmune sera from the same rabbit had no effect (lane 3). Similarly, while sp.tia76-94 inhibited binding at concentrations of 0.4 and 4 pmol/liter (lanes 5 and 6, respectively), equimolar amounts of the unrelated control peptide sp.sls10-30 (lane 7, 0.4 pmol/liter; lane 8, 4 pmol/liter) did not inhibit binding.

Interaction of Tia with eukaryotic heparin binding proteins.

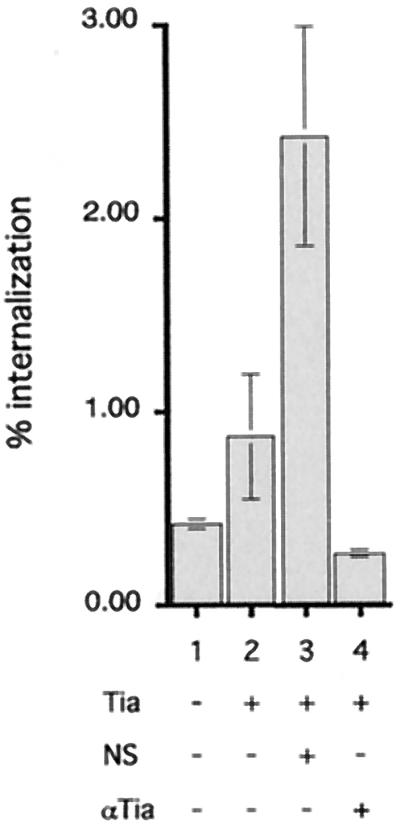

To study the role of Tia-mediated interactions with epithelial cells, we performed experiments with polyclonal antisera raised against histidine-tagged rTia. As shown in Fig. 5, these antisera markedly decreased the number of bacteria internalized by target epithelial cells, which supported the hypothesis that Tia is sufficient to mediate bacterial entry. However, in the course of these experiments, it was also noted that addition of preimmune rabbit serum to the media prior to addition of bacteria resulted in increased internalization of the DH5α(pET185) Tia recombinants but had no effect on the uptake of E. coli DH5α containing only the vector plasmid, pHG165. These results suggested that a component of normal serum might bind to the bacteria via Tia and facilitate their interaction with target host cells.

FIG. 5.

Normal serum enhances epithelial cell internalization of Tia-expressing E. coli recombinants. HCT-8 cells were the target cells used. Bar 1, AAEC191A(pHG165) vector control; bar 2, AAEC191A(pET185) tia recombinant in the absence of serum; bar 3, AAEC191A(pET185) tia recombinant with a 1:100 dilution of normal, preimmune rabbit serum (NS); bar 4, AAEC191A(pET185) tia recombinant in the presence of immune serum containing anti-rTia antibody (αTia) (1:100) from the same rabbit.

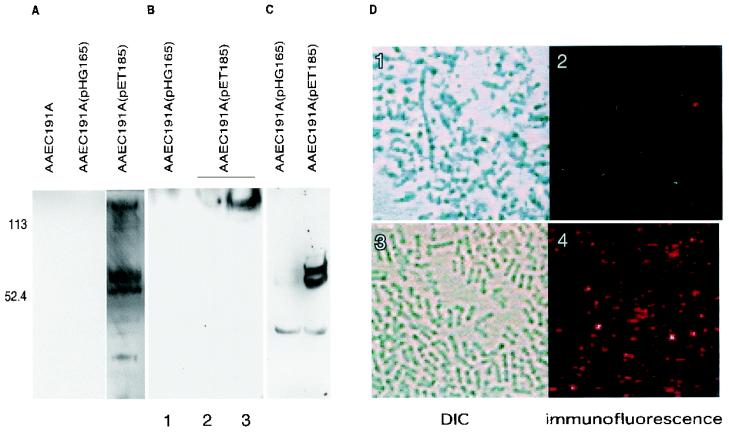

Previous studies suggested that a number of pathogens may utilize an initial interaction with GAGs to provide a conserved recognition binding site for recruitment of a number of MHBPs (18). In theory, GAG-facilitated interaction with MHBPs could promote bacterial attachment or modulate host responses to the bacteria. To determine whether Tia participates in similar interactions that ultimately result in bacterial attachment and/or internalization, bacteria expressing Tia were used to capture potential ligands from NHS. Binding of biotinylated proteins from NHS to Tia-expressing recombinants and subsequent blotting and detection of bound proteins with streptavidin-HRP yielded one band at a molecular mass of more than 200 kDa and two bands at molecular masses between 60 and 80 kDa (Fig. 6A). This pattern was reminiscent of that observed by Duensing and van Putten (16) in a study of the interaction of OpaA+ gonococci with heparin binding proteins purified from serum, in which fibronectin was represented by a band at 220 kDa and vitronectin migrated as a doublet at molecular masses of 78 and 68 kDa. To further identify the proteins that bound to Tia-expressing E. coli, the blot described above was first stripped and reacted with antibodies against fibronectin. This process was repeated by using antibodies against vitronectin. Detection with these primary antibodies resulted in identification of proteins whose molecular weights were identical to the molecular weights of proteins on the original blot detected with streptavidin-HRP (data not shown). Finally, these binding experiments were repeated by using commercially available fibronectin and vitronectin. Biotinylated fibronectin was found to bind to Tia, particularly when exogenous heparin was added prior to binding (Fig. 6B). Similarly, in the presence of heparin, purified vitronectin bound to bacteria expressing rTia but not to bacteria containing the control plasmid vector, as detected by immunoblotting (Fig. 6C) and by immunofluorescence (Fig. 6D).

FIG. 6.

Potential recruitment of eukaryotic heparan sulfate binding proteins by Tia. (A) Binding of biotinylated NHS proteins with molecular masses of approximately 220, 75, and 65 kDa to E. coli recombinants expressing tia [AAEC191A(pET185)] or bearing a vector control plasmid [AAEC191A(pHG165)]. Subsequent stripping of this blot and redetection of bound antigens with anti-fibronectin and anti-vitronectin specific antibodies revealed the bands at ∼220 kDa (fibronectin) and at 75 and 65 kDa (vitronectin), respectively (data not shown). (B) Binding of purified, biotinylated fibronectin to AAEC191A(pHG165) after preincubation with heparin (lane 1) and to AAEC191A(pET185) without additional heparin (lane 2) and following preincubation with heparin (5 μg/ml) and extensive washing prior to binding of fibronectin (lane 3). (C) Binding of purified, unlabeled vitronectin to a Tia recombinant strain but not to a control strain after preincubation with heparin (5 μg/ml), as detected in an immunoblot by using anti-vitronectin antibody. (D) Immunofluorescence detection of vitronectin binding to E. coli recombinants expressing Tia following preincubation with heparin. The Nomarski differential interference contrast (DIC) images show that roughly equivalent numbers of the AAEC191A(pHG165) tia-negative control (panel 1) and the AAEC191A(pET185) tia recombinant strain (panel 3) were examined by immunofluorescence. AAEC191A(pET185) readily bound unlabeled vitronectin (immunofluorescence image in panel 4), whereas AAEC191A(pHG165) could not bind vitronectin (panel 2).

These results are consistent with the model proposed by Duensing et al., in which bacteria express surface proteins that bind to GAGs (18). In this model, GAGs bound to the surface of the organism serve as a template to bind a number of MHBPs, including adhesive glycoprotein molecules, such as vitronectin. These trimolecular (prokaryotic protein-GAG-MHBP) complexes may facilitate the ultimate interaction with host cell targets (for example, through interaction of vitronectin via its Arg-Gly-Asp sequence with integrin receptors [17]). To test this hypothetical model, we performed experiments in which tia-expressing E. coli recombinants were preincubated with heparin (5 μg/ml) and washed before various amounts of vitronectin were added to serum-free media. This led to modest but vitronectin dose-dependent increases in the number of Tia-expressing bacteria internalized by HCT-8 cells (data not shown), suggesting that Tia may also exert its effect through development of a molecular bridge to host cell surface receptors.

DISCUSSION

The tia locus was originally cloned from prototypical ETEC strain H10407 by screening a cosmid library for loci that promoted epithelial cell attachment and invasion (19). Subsequent studies revealed that the tia gene encodes a 25-kDa outer membrane protein (23) and that this gene is located on an apparent pathogenicity island (24). This study and previous studies of Tia have focused on the role of this outer membrane protein in mediating adherence and invasion into epithelial cells. Our data suggest that the interaction of Tia with HSPGs plays a central role in this process. Although at least one study has suggested that epithelial cell invasion may occur in vivo with some porcine ETEC strains (38), there are no data for similar events in the pathogenesis of human ETEC infections. Whether epithelial cell invasion by ETEC occurs during human infections or not, data presented here and elsewhere support the hypothesis that tia plays a role in mediating pathogen-host cell interactions.

The molecular events that surround Tia-mediated invasion in vitro have not previously been explored in detail. Interestingly, genes encoding proteins with considerable homology to Tia have been described for strains of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (28), as well as porcine ETEC strains (35) and other pathogenic E. coli strains (48). Similar to the tia gene in H10407, these tia-like genes are on large chromosomal elements (24). The precise function of the Tia homologues also remains undefined. Because Tia also exhibits significant homology with members of the Opa family, which are neisserial proteins that direct epithelial cell attachment and invasion, we sought to determine whether similar processes might govern the cellular interactions promoted by the corresponding proteins.

Both Tia and the Opa proteins belong to a family of outer membrane proteins with a structure predicted to form an eight-stranded transmembrane β-barrel having four surface-exposed domains. Within this family, the structure-function relationships of the Opa proteins have been studied most extensively. The studies have revealed that a single strain of N. gonorrhoeae may possess 11 or 12 opa genes that undergo phase variations in expression, directed by unique recombination events (46). These different genes encode outer membrane proteins with considerable sequence variation in their surface-exposed epitopes (6, 9, 15). Among the Opa proteins, OpaA is unique in its ability to bind to HSPG. Furthermore, a surface domain of OpaA that is essential for the cooperative interaction with HSPG, hypervariable region 1, has recently been identified (27). Theoretically, the basic amino acid residues of the exposed regions are involved in electrostatic interactions with HSPGs.

Although some prokaryotic outer membrane heparin binding proteins possess consensus sequences that have been associated with heparin binding, such as the XBBXBX motif (45), a clear heparin binding motif was not found in the Tia sequence. In fact, Clustal alignments of Tia and the Opa proteins did not reveal a region uniquely conserved in Tia and OpaAMS11. These alignments suggest that the most highly conserved regions are in the regions predicted to be part of the transmembrane β-sheet motifs. Optimal interaction of Tia with HSPGs may involve approximation of basic residues on exposed loops in the tertiary structure, as suggested previously for some eukaryotic proteins (10). Furthermore, recent data suggest that some prokaryotic ligands recognize specific arrangements in disaccharide units of proteoglycans (20). This may indicate that optimal binding to HSPGs involves a more intricate lock and key mechanism rather than simple electrostatic attraction.

Duensing et al. have proposed that interaction with sulfated polysaccharides may be a mechanism for bacteria to recruit an array of MHBPs (18). The various molecular bridges formed between surface proteins of the bacteria, GAGs, and MHBPs could provide a highly adaptive mechanism for modulating bacterium-host interactions, taking advantage of the binding of a limited number of bacterial surface proteins to ubiquitous mammalian polysaccharide molecules in various niches. Our data support the concept that Tia, a prokaryotic heparin binding protein, has the potential to participate in interactions with a number of MHBPs. For Tia, like the OpaA protein of N. gonorrhoeae, such interactions may be determined by the niche in which Tia is optimally expressed and, consequently, by the availability of an appropriate HSPG template and particular eukaryotic heparin binding proteins. Interestingly, previous studies of gonococci expressing OpaA have suggested that entry of these organisms into cells belonging to different cell lines is dependent on the interaction of this outer membrane protein with molecular complexes that include HSPG and extracellular matrix proteins, such as fibronectin or vitronectin (16, 18, 49). Also, several previous reports suggested that ETEC strains also bind to fibronectin (22, 25), as well as vitronectin (14), and that the interactions may play an important role in bacterial adherence. However, the precise nature of the interaction between ETEC and these extracellular proteins has not been defined yet. Our results suggest that Tia could interact with these and perhaps other MHBPs. However, understanding the precise role of these proteins in Tia-mediated adherence and invasion will require additional studies. In addition, although it is convenient to study epithelial cell invasion in vitro, this phenomenon may be the result of one of several potential Tia-mediated pathogen-host interactions and may obscure the precise role of Tia in the interaction between the bacteria and the intestinal epithelium.

While many pathogens have been shown to interact with HSPGs, potentially to promote adhesion, the precise roles of these proteins in the pathogenesis of infections remain undefined. Recent studies have suggested that organisms may utilize these interactions for more than simple adherence. Indeed, some organisms induce shedding of proteoglycans via specific proteases, and these soluble proteoglycans inactivate cationic antimicrobial peptides (39, 43). Such strategies could provide a powerful selective advantage for a pathogen. Additional studies involving Tia and similar molecules must take into account their potential interactions with multiple eukaryotic proteins and address other possible roles in addition to promotion of adherence to and invasion of epithelial cells.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the advice and suggestions of Scott D. Gray-Owen and Christian Ockenhouse. We thank James Dale and Harry Courtney for their critical reviews of the manuscript.

This study was supported by grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs (to J.M.F. and D.L.H.), by institutional funds from the University of Tennessee, and by Research, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anonymous. 1994. Foodborne outbreaks of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli—Rhode Island and New Hampshire, 1993. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 43:87-89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. 1999. New frontiers in the development of vaccines against enterotoxinogenic (ETEC) and enterohaemorrhagic (EHEC) E. coli infections. Part I. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 74:98-101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldermann, C., A. Lupas, J. Lubieniecki, and H. Engelhardt. 1998. The regulated outer membrane protein Omp21 from Comamonas acidovorans is identified as a member of a new family of eight-stranded beta-sheet proteins by its sequence and properties. J. Bacteriol. 180:3741-3749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beer, K. B., and V. L. Miller. 1992. Amino acid substitutions in naturally occurring variants of ail result in altered invasion activity. J. Bacteriol. 174:1360-1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernfield, M., M. Gotte, P. W. Park, O. Reizes, M. L. Fitzgerald, J. Lincecum, and M. Zako. 1999. Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68:729-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhat, K. S., C. P. Gibbs, O. Barrera, S. G. Morrison, F. Jahnig, A. Stern, E. M. Kupsch, T. F. Meyer, and J. Swanson. 1991. The opacity proteins of Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain MS11 are encoded by a family of 11 complete genes. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1889-1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Billker, O., A. Popp, S. D. Gray-Owen, and T. F. Meyer. 2000. The structural basis of CEACAM-receptor targeting by neisserial Opa proteins. Trends Microbiol. 8:258-260. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Blomfield, I. C., M. S. McClain, and B. I. Eisenstein. 1991. Type 1 fimbriae mutants of Escherichia coli K12: characterization of recognized afimbriate strains and construction of new fim deletion mutants. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1439-1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brooks, G. F., L. Olinger, C. J. Lammel, K. S. Bhat, C. A. Calvello, M. L. Palmer, J. S. Knapp, and R. S. Stephens. 1991. Prevalence of gene sequences coding for hypervariable regions of Opa (protein II) in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol. Microbiol. 5:3063-3072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Busby, T. F., W. S. Argraves, S. A. Brew, I. Pechik, G. L. Gilliland, and K. C. Ingham. 1995. Heparin binding by fibronectin module III-13 involves six discontinuous basic residues brought together to form a cationic cradle. J. Biol. Chem. 270:18558-18562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cassels, F. J., and M. K. Wolf. 1995. Colonization factors of diarrheagenic E. coli and their intestinal receptors. J. Ind. Microbiol. 15:214-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, T., R. J. Belland, J. Wilson, and J. Swanson. 1995. Adherence of pilus− Opa+ gonococci to epithelial cells in vitro involves heparan sulfate. J. Exp. Med. 182:511-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, T., and E. C. Gotschlich. 1996. CGM1a antigen of neutrophils, a receptor of gonococcal opacity proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:14851-14856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chhatwal, G. S., K. T. Preissner, G. Muller-Berghaus, and H. Blobel. 1987. Specific binding of the human S protein (vitronectin) to streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 55:1878-1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Connell, T. D., W. J. Black, T. H. Kawula, D. S. Barritt, J. A. Dempsey, K. Kverneland, Jr., A. Stephenson, B. S. Schepart, G. L. Murphy, and J. G. Cannon. 1988. Recombination among protein II genes of Neisseria gonorrhoeae generates new coding sequences and increases structural variability in the protein II family. Mol. Microbiol. 2:227-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duensing, T., and J. van Putten. 1997. Vitronectin mediates internalization of Neisseria gonorrhoeae by Chinese hamster ovary cells. Infect. Immun. 65:964-970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duensing, T. D., and J. P. Putten. 1998. Vitronectin binds to the gonococcal adhesin OpaA through a glycosaminoglycan molecular bridge. Biochem. J. 334:133-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duensing, T. D., J. S. Wing, and J. P. van Putten. 1999. Sulfated polysaccharide-directed recruitment of mammalian host proteins: a novel strategy in microbial pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 67:4463-4468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elsinghorst, E. A., and D. J. Kopecko. 1992. Molecular cloning of epithelial cell invasion determinants from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 60:2409-2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esko, J. D., and U. Lindahl. 2001. Molecular diversity of heparan sulfate. J. Clin. Investig. 108:169-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farabaugh, P. J. 1978. Sequence of the lacI gene. Nature 274:765-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faris, A., G. Froman, L. Switalski, and M. Hook. 1988. Adhesion of enterotoxigenic (ETEC) and bovine mastitis Escherichia coli strains to rat embryonic fibroblasts: role of amino-terminal domain of fibronectin in bacterial adhesion. Microbiol. Immunol. 32:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fleckenstein, J. M., D. J. Kopecko, R. L. Warren, and E. A. Elsinghorst. 1996. Molecular characterization of the tia invasion locus from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 64:2256-2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleckenstein, J. M., L. E. Lindler, E. A. Elsinghorst, and J. B. Dale. 2000. Identification of a gene within a pathogenicity island of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli H10407 required for maximal secretion of the heat-labile enterotoxin. Infect. Immun. 68:2766-2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Froman, G., L. M. Switalski, A. Faris, T. Wadstrom, and M. Hook. 1984. Binding of Escherichia coli to fibronectin. A mechanism of tissue adherence. J. Biol. Chem. 259:14899-14905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuller, A. 1994. Microbes and the proteoglycan connection. J. Clin. Investig. 93:460.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grant, C. C., M. P. Bos, and R. J. Belland. 1999. Proteoglycan receptor binding by Neisseria gonorrhoeae MS11 is determined by the HV-1 region of OpaA. Mol. Microbiol. 32:233-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heithoff, D. M., C. P. Conner, P. C. Hanna, S. M. Julio, U. Hentschel, and M. J. Mahan. 1997. Bacterial infection as assessed by in vivo gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:934-939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isberg, R. R., and J. M. Leong. 1988. Cultured mammalian cells attach to the invasin protein of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:6682-6686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isberg, R. R., D. L. Voorhis, and S. Falkow. 1987. Identification of invasin: a protein that allows enteric bacteria to penetrate cultured mammalian cells. Cell 50:769-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landegren, U. 1984. Measurement of cell numbers by means of the endogenous enzyme hexosaminidase. Applications to detection of lymphokines and cell surface antigens. J. Immunol. Methods 67:379-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levine, M. M., D. R. Nalin, D. L. Hoover, E. J. Bergquist, R. B. Hornick, and C. R. Young. 1979. Immunity to enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 23:729-736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lidholt, K., J. L. Weinke, C. S. Kiser, F. N. Lugemwa, K. J. Bame, S. Cheifetz, J. Massague, U. Lindahl, and J. D. Esko. 1992. A single mutation affects both N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase and glucuronosyltransferase ac tivities in a Chinese hamster ovary cell mutant defective in heparan sulfate biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:2267-2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lutwyche, P., R. Rupps, J. Cavanagh, R. A. Warren, and D. E. Brooks. 1994. Cloning, sequencing, and viscometric adhesion analysis of heat-resistant agglutinin 1, an integral membrane hemagglutinin from Escherichia coli O9:H10:K99. Infect. Immun. 62:5020-5026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mammarappallil, J. G., and E. A. Elsinghorst. 2000. Epithelial cell adherence mediated by the enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli Tia protein. Infect. Immun. 68:6595-6601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller, V., J. Bliska, and S. Falkow. 1990. Nucleotide sequence of the Yersinia enterocolitica gene and characterization of the Ail gene product. J. Bacteriol. 172:1062-1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moxley, R. A., E. M. Berberov, D. H. Francis, J. Xing, M. Moayeri, R. A. Welch, D. R. Baker, and R. G. Barletta. 1998. Pathogenicity of an enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli hemolysin (hlyA) mutant in gnotobiotic piglets. Infect. Immun. 66:5031-5035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park, P. W., G. B. Pier, M. T. Hinkes, and M. Bernfield. 2001. Exploitation of syndecan-1 shedding by Pseudomonas aeruginosa enhances virulence. Nature 411:98-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peruski, L. F., Jr., B. A. Kay, R. A. El-Yazeed, S. H. El-Etr, A. Cravioto, T. F. Wierzba, M. Rao, N. El-Ghorab, H. Shaheen, S. B. Khalil, K. Kamal, M. O. Wasfy, A.-M. Svennerholm, J. D. Clemens, and S. J. Savarino. 1999. Phenotypic diversity of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli strains from a community-based study of pediatric diarrhea in periurban Egypt. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2974-2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roels, T., M. Proctor, L. Robinson, K. Hulbert, C. Bopp, and J. Davis. 1998. Clinical features of infections due to Escherichia coli producing heat-stable toxin during an outbreak in Wisconsin: a rarely suspected cause of diarrhea in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:898-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rostand, K. S., and J. D. Esko. 1997. Microbial adherence to and invasion through proteoglycans. Infect. Immun. 65:1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidtchen, A., I. Frick, and L. Bjorck. 2001. Dermatan sulphate is released by proteinases of common pathogenic bacteria and inactivates antibacterial alpha-defensin. Mol. Microbiol. 39:708-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sonnenburg, F. V., N. Tornieporth, P. Waiyaki, B. Lowe, L. Peruski, H. Dupont, J. Mathewson, and R. Steffen. 2000. Risk and aetiology of diarrheoa at various tourist destinations. Lancet 356:133-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stephens, R., K. Koshiyama, E. Lewis, and A. Kubo. 2001. Heparin-binding outer membrane protein of chlamydia. Mol. Microbiol. 40:691-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stern, A., M. Brown, P. Nickel, and T. F. Meyer. 1986. Opacity genes in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: control of phase and antigenic variation. Cell 47:61-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stewart, G., S. Lubinsky-Mink, C. Jackson, A. Cazzel, and J. Kuhn. 1986. pHG165: a pBR322 copy number derivative of pUC8 for cloning and expression. Plasmid 15:172-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swenson, D. L., N. Bukanov, D. Berg, and R. Welch. 1996. Two pathogenicity islands in uropathogenic Escherichia coli J96: cosmid cloning and sample sequencing. Infect. Immun. 64:3736-3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Putten, J. P., T. D. Duensing, and R. L. Cole. 1998. Entry of OpaA+ gonococci into HEp-2 cells requires concerted action of glycosaminoglycans, fibronectin and integrin receptors. Mol. Microbiol. 29:369-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Villarejo, M. R., and I. Zabin. 1974. Beta-galactosidase from termination and deletion mutant strains. J. Bacteriol. 120:466-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Virji, M., K. Makepeace, D. J. Ferguson, and S. M. Watt. 1996. Carcinoembryonic antigens (CD66) on epithelial cells and neutrophils are receptors for Opa proteins of pathogenic neisseriae. Mol. Microbiol. 22:941-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams, A., and I. Ibrahim. 1981. A new mechanism involving cyclic tautomers for the reaction with nucleophiles of the water-soluble peptide coupling reagent 1-ethyl-3-(-(dimethylamino)propyl)-carbodiimide (EDC). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 103:7090-7095. [Google Scholar]